#marina bolotnikova

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Fires on large-scale animal farms, or factory farms, are surprisingly common. Over the last decade, at least 6.5 million farmed animals, mostly chickens, perished in barn fires in the US, according to Washington, DC-based nonprofit Animal Welfare Institute (AWI). The fires are part of a broader pattern of mass casualty events on factory farms, where 99 percent of America's meat, dairy, and eggs are produced. Some are the result of human or mechanical error, but many stem from natural disasters, such as hurricanes, blizzards, and extreme temperatures, like last summer's scorching heat wave in Kansas that killed thousands of cows who were subsequently dumped in a landfill. Disease outbreaks, too, result in mass death or culling on farms.

- Kenny Torrella, Marina Bolotnikova, and Julieta Cardenas, "A fire killed 18,000 cows in Texas. It's a horrifyingly normal disaster."

Torrella, Kenny, Marina Bolotnikova, and Julieta Cardenas. "A fire killed 18,000 cows in Texas. It's a horrifyingly normal disaster." Vox, April 14, 2023. https://www.vox.com/future-perfect/23683141/texas-farm-fire-explosion-dimmitt-cows-factory-dairy.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Tens of billions of land animals slaughtered every year; hundreds of millions every day; thousands in the time it takes to read this sentence. The number grows by billions more every year, into multiples that feel as abysmal as they are mind-numbing.

On top of 80 billion, how can we comprehend another 5, 10, 20 billion more? How can it get worse? And while we can count suffering in the aggregate, these animals experience it as individuals, each one containing an infinite depth of conscious experience. Our human world is built atop a parallel universe of their misery, an inferno from which most of us prefer to look away.

Since I made the choice to leave meat behind for ethical reasons more than a decade ago, the factory farm system has only gotten bigger and bigger. That’s one reason why I’ve spent the last several years reporting on meat’s impacts on animals, climate, politics, and culture. In this piece, I wanted to take a step back and think through the depth of the challenge facing the movement against animal exploitation" (By Marina Bolotnikova). Read the full article here.

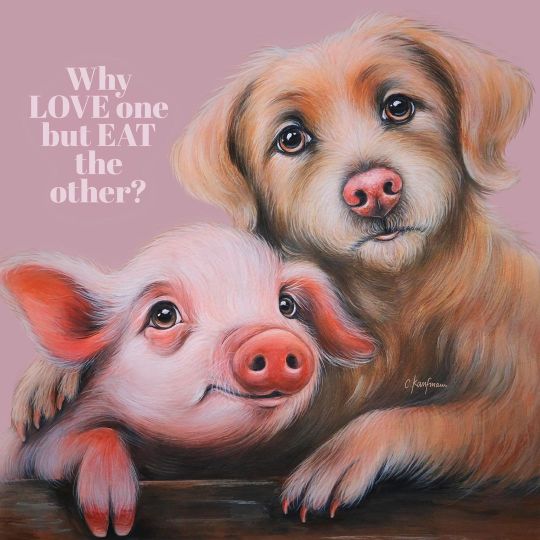

Image by Chantal Kaufman

#vegetarian#vegan#animal rights#animal cruelty#animal exploitation#compassion#respect#ethical reasons#climate change#peace

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Marina Bolotnikova at Vox:

Every five years, farm state politicians in Congress perform their fealty to Big Ag in a peculiar ritual called the Farm Bill: a massive, must-pass package of legislation that dictates food and farming policy in the US.

At the urging of the pork industry, congressional Republicans want to use this year’s bill to undo what little progress the US has made in improving conditions for animals raised on factory farms. The House Agriculture Committee late last month advanced a GOP-led Farm Bill with a rider designed to nullify California’s Proposition 12 — a landmark ballot measure, passed by an overwhelming majority in that state in 2018, banning extreme farm animal confinement — and prevent other states from enacting similar laws. Prop 12, along with a comparable law in Massachusetts passed by ballot measure in 2016, outlaws the sale of pork produced using gestation crates — devices that represent perhaps the pinnacle of factory farm torture. While many of the tools of factory farming are the product of biotech innovation, gestation crates are deceptively low-tech: They’re simply small cages that immobilize mother pigs, known as sows, who serve as the pork industry’s reproductive machines. Sows spend their lives enduring multiple cycles of artificial insemination and pregnancy while caged in spaces barely larger than their bodies. It is the equivalent to living your entire, short life pregnant and trapped inside a coffin.

Ian Duncan, an emeritus chair in animal welfare at the University of Guelph in Canada, has called gestation crates “one of the cruelest forms of confinement devised by humankind.” And yet they’re standard practice in the pork industry. While Prop 12 has been celebrated as one of the strongest farm animal protection laws in the world, its provisions still fall far short of giving pigs a humane life. It merely requires providing enough space for the sows to be able to turn around and stretch their legs. It still allows the use of farrowing crates, cages similar to gestation crates that confine sows and their nursing piglets for a few weeks after birth. And about 40 percent of pork sold in California is exempt; Prop 12 covers only whole, uncooked cuts, like bacon or ribs, but not ground pork or pre-cooked pork in products like frozen pizzas. The pork lobby refuses to accept even those modest measures and has sought to link Prop 12 to the agenda of “animal rights extremists.” It has also claimed that the law would put small farms out of business and lead to consolidation, even though it is the extreme confinement model favored by mega factory farms that has driven the skyrocketing level of consolidation seen in the pork industry over the last few

For nearly six years, instead of taking steps to comply with Prop 12, pork lobbyists sued to get the law struck down. They lost at every turn. Last year, the US Supreme Court rejected the industry’s argument that it had a constitutional right to sell meat raised “in ways that are intolerable to the average consumer,” as legal scholars Justin Marceau and Doug Kysar put it.

[...]

Overturning Prop 12 would be extreme, and it could have far-reaching consequences

Several other states have gestation crate bans, but the California and Massachusetts laws are unique because they outlaw not just the use of crates within those states’ borders, but also the sale of pork produced using gestation crates anywhere in the world. Both states import almost all of their pork from bigger pork-producing states (the top three are Iowa, Minnesota, and North Carolina), so the industry has argued that Prop 12 and Massachusetts’ Question 3 unfairly burden producers outside their borders. California in particular makes up about 13 percent of US pork consumption, threatening to upend the industry’s preferred way of doing business for a big chunk of the market.

The California and Massachusetts laws also ban the sale of eggs and veal from animals raised in extreme cage confinement. Both industries opposed Prop 12 before it passed but have largely complied with the law; neither has put up the fierce legal fight that the pork industry has, led by Big Meat lobbying groups like the National Pork Producers Council, the North American Meat Institute, and the American Farm Bureau Federation.

House Agriculture Committee chair Glenn Thompson (R-PA), who introduced this year’s House Farm Bill last month, touts “addressing Proposition 12” as a core priority. The legislation includes a narrowed version of the EATS Act (short for Ending Agricultural Trade Suppression), a bill introduced by Republicans in both chambers last year to ban states from setting their own standards for the production of any agricultural products, animal or vegetable, imported from other states.

The Farm Bill language has been tightened to focus solely on livestock, banning states from setting standards for how animal products imported from other states are raised. It is less extreme only in comparison to the sweeping EATS Act, but also more transparent about its aim to shield the meat industry from accountability. At the Farm Bill markup on May 23, when the legislation passed committee, Thompson urged his colleagues to protect the livestock industry from “inside-the-beltway animal welfare activists.” The provisions slipped into the Farm Bill may have consequences that reach far beyond the humane treatment of animals. They “could hamstring the ability of states to regulate not just animal welfare but also the sale of meat and dairy products produced from animals exposed to disease, with the use of certain harmful animal drugs, or through novel biotechnologies like cloning, as well as adjacent production standards involving labor, environmental, or cleanliness conditions,” Kelley McGill, a legislative policy fellow at Harvard’s Animal Law & Policy Program who authored an influential report last year on the potential impacts of the EATS Act, told me in an email.

[...]

Why this Farm Bill faces long odds

Despite the monumental effort from the pork lobby and its allies, the odds of this year’s Farm Bill nullifying Prop 12 appear slim. Democrats, who control the Senate, oppose the House bill’s proposed cuts to the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), which makes up about 80 percent of the bill’s $1.5 trillion in spending, and its removal of so-called climate-smart conditions from farm subsidies made available by the Inflation Reduction Act. Members of the House Freedom Caucus, on the other hand, are likely to demand steeper cuts to SNAP, formerly known as food stamps.

The broader EATS Act has been opposed by more than 200 members of Congress, including more than 100 Democratic representatives and several members of the Freedom Caucus; Prop 12 nullification language is not included in the rival Senate Farm Bill framework introduced by Sen. Debbie Stabenow (D-MI). Many lawmakers and other observers consider the House bill dead on arrival, which would mean that a Farm Bill may not get passed until 2025. Prop 12’s pork regulations, meanwhile, took full effect in California at the start of this year after two years of delay due to the industry’s legal challenges. After implementation, prices for pork products covered by the law abruptly increased by about 20 percent on average, a spike that UC Davis agricultural economist Richard Sexton attributes to the pork producers’ reluctance to convert their farms to gestation crate-free before they knew whether Prop 12 would be upheld by the Supreme Court.

House Republicans want to use the Farm Bill to push back against even modest improvements for animals in factory farms.

#Farming#Animal Rights#Farm Bill#California Proposition 12#Pork Industry#Caged Eggs#Massachusetts Question 3#Glenn Thompson#EATS Act#Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program#SNAP#Food Assistance

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

0 notes

Link

Three things the US can learn about road safety from our ultra-safe air travel system. In the last decade, two passengers have been killed in accidents on US commercial airlines. Over the same period, more than 365,000 Americans have been killed by cars.

0 notes

Photo

"A Graceful Place Where Bhangra and Bollywood Meet" by BY MARINA BOLOTNIKOVA via NYT New York Times https://t.co/BwMoJmzQiL (via Twitter http://twitter.com/zephyrzap/status/1408693318859509762) "A Graceful Place Where Bhangra and Bollywood Meet" by BY MARINA BOLOTNIKOVA via NYT New York Times https://t.co/BwMoJmzQiL https://ift.tt/3jhzVN1

0 notes

Quote

The payoff for children’s programs is so dramatic, the paper suggests, that it may not make sense to think of them as “spending” at all. A 2016 study by Hendren and Harvard economists Raj Chetty and Lawrence Katz, for example, found that giving low-income families vouchers that helped them move to lower-poverty neighborhoods substantially improved college attendance rates and lifetime earnings for their children. Spending to support adults can have a similar effect. In one example, states across the country between 1979 and 1992 expanded Medicaid to pregnant women, giving them better access to prenatal care. That policy change reduced future hospitalizations for their children, increased college attendance, and ultimately raised incomes. By the time their children were 36 years old, according to the new paper, increased tax revenue attributable to their higher earnings had already made up for the cost of the Medicaid expansion (about $3,473 for each mother).

Welfare’s Payback by MARINA N. BOLOTNIKOVA

0 notes

Text

Lessons From Massachusetts’ Failed Healthcare Cost Experiment

By SOUMERAI, KOPPELL & BOLOTNIKOVA

Massachusetts passed a massive medical cost control bill in 2012, a “Hail Mary” effort to make health-care more affordable in the nation’s most expensive medical market. The problems of the Massachusetts’ law offer invaluable lessons for the nation’s health-care struggles.

Driven in part by a Boston Globe investigation that exposed the likely collusion of the Partners Healthcare hospital system (including several Harvard Medical School teaching hospitals) with Blue Cross/Blue Shield, the largest healthcare insurer in the state, the law marked the biggest health reform since Romneycare in 2006. While most agree Massachusetts needed cost controls, there’s no evidence that the 2012 law has accomplished its goal—and these same failed policies have been folded into the national Affordable Care Act.

Romneycare, Massachusetts’ universal health-care law, already lacked effective rules to control the rapid growth of state medical costs. That, paired with the Boston Globe’s exposure of the likely collusion between Partners Healthcare, the largest hospital system in New England, and Blue Cross Blue Shield to raise health care payments to hospitals and doctors by as much as 75 percent, led to passage of a hefty, 349-page cost-control law in 2012. The legislation included a dizzying number of committees, an uncoordinated “cost containment” process, and dubious quality-of-care policies, like “pay-for-performance,” a program that pays doctors bonuses for meeting certain quality standards, like measuring blood pressure. These incentives might make sense in economic theory, but have failed repeatedly in well controlled studies. They’ve even created perverse enticements, such as some doctors avoiding sicker patients. The cost control law also encouraged widespread use of expensive electronic health records, even though there’s no evidence that they save any money.

Additional policies in the law are “accountable care organizations” (ACOs) and “alternative quality contracts,” programs that pay doctors for staying under an arbitrary budget and penalize them for going over it. But the best studies show, again, that these policies actually increase costs if you count the expense of implementing them. In fact, most of the hospitals in the federal government’s “Pioneer ACO” program have dropped out, including Dartmouth Hitchcock, the famous medical center, associated with Dartmouth College, that initially coined the term “ACO.”

Given the MA cost control law’s outcomes so far, we should be very skeptical about its projected savings. Suffice to say, the law is too complex, unwieldy, contrary to evidence and, worse, doesn’t have the teeth (e.g., regulating price) to enforce cost reductions among the most powerful medical providers. Nancy Turnbull, one of the architects of Massachusetts’ health reform and a member of the board of its insurance exchange, told the New York Times in 2012 that the law “was not nearly what we need to deal with the market power and the unjust price differences that result.”

So how has the law’s repeated disappointments been described to the public? Recently, a front-page, above the fold story in the Globe suggested the law resulted in a “slower rise in health spending” in 2015—which amounted to a decrease of 0.3 percent from the previous year. Researchers often doubt such tiny effect sizes and for good reason. They usually aren’t real. But even worse, the Globe’s “analysis” relies on just two data points, both from years after the 2012 law passed. Had the Globe’s story begun with data from before the law’s enactment, (see graph below) it would have shown that per-capita health-care spending growth actually increased by more than two percentage points since the policy began. This month, the Globe again wrongly reported that new data in 2016 shows the state has helped reduce health-care spending. The data from the last few years contrasts with the previous decade, when health-care cost growth had been declining steadily. Thus it’s unlikely that the tiny changes in costs from 2014-2016 had anything to do with the new cost control effort. And the average annual cost growth over the last three years is still about twice the level at the time the law passed.

This figure, with more complete data, shows that between 2002 and 2011, the year before the law, there was a much greater decline in Massachusetts healthcare cost growth—from 9 percent annual per capita growth to under 4 percent. The tiny changes in the growth rate from 2014 to 2016 (years after the law) is not evidence that the 2012 state law reduced costs, because cost growth in those years was still twice as high as it had been in 2012 and 2013. In addition, the reporting did not even mention the start of Obamacare regulations less than two years before the MA cost control law, so it is impossible to know whether these policies caused the increase in health care costs observed in the graph. This untrustworthy analysis could fool Massachusetts policymakers and citizens into thinking that its policies were working, or convince other states to follow Massachusetts’ model.

The Massachusetts cost control law has not fulfilled its promise to “bend the cost curve.” If anything costs have gotten higher. The commission set up by the law “may encourage, cajole, and, if needed, shame [providers] into doing their part to control costs. “But this is insufficient to fundamentally change the behavior of the systems with the most market power. Charges for a single aspirin pill in a hospital can be higher than $25, but only pennies at the local drug store. It is already clear that the health care cost crisis is threatening the viability of essential government services from education to defense. To make matters worse, the state’s largest newspaper acts as the law’s cheerleader without even considering the history of health care costs that clearly shows the law’s shortcomings.

So what should be done now? In the near term, the legislature should consider much stronger cost controls that do not rely on the voluntary cooperation of hospitals or on market-based incentives and penalties. The state (and nation) must abandon ineffective, wasteful “alternative payment arrangements” that save miniscule dollars while costing delivery systems billions. Massachusetts and the nation need effective, negotiated price controls that fairly compensate hospitals but do not allow a few elite institutions to receive excessive reimbursement. But the current Republican health plan would retain all the failed aspects of Obamacare, while dropping the parts of the law that gave millions of poor Americans access to health-care.

There are better solutions: Our political system thus far has rejected government-run, single-payer systems, like the British National Health Service and Canada, but there are plenty of private, market-based models in Europe that provide better care to their citizens at half the cost. They rely on straightforward price controls, negotiated between the private and public sectors—not more failed market incentives. Germany’s system, for example, relies on hundreds of competing health insurers. The key difference is the use of medical fee schedules (price controls) that are negotiated between provider associations and insurance programs that prevent the kind of price fixing uncovered by the Globe. Switzerland has similar arrangements. The companies compete on quality of service and efficiency. Germany and Switzerland have managed to avoid most of the costly deductibles and copayments that keep health-care out of reach for ordinary Americans: no prohibitively expensive $10,000 deductibles (which is more than most Americans have in savings), as allowed under the ACA. The US could choose the best aspects of these successful plans that fit our culture and our health care environment.

Ten years ago, Massachusetts built the model for the nation’s health reform law, which then expanded health care to more than 22 million Americans and offered needed protections to America’s population, e.g., removal of pre-existing condition restrictions, free mammograms, and the ability to insure adult children. But we remain the only developed country in the world that fails to provide care to all its citizens. And we allow costs to grow at unsustainable rates. Rather than wait for the implosion of our medical system, Massachusetts must again lead by example in the nation’s polarized health reform debate—this time, by establishing affordable health-care as a right for all its residents.

Stephen Soumerai is Professor of Population Medicine and teaches research methods at Harvard Medical School.

Professor Ross Koppel teaches research methods and statistics in the Sociology department at the University of Pennsylvania and is a Senior Fellow at the Leonard Davis Institute (Wharton) of Healthcare Economics.

Marina Bolotnikova is an associate editor at Harvard Magazine.

Article source:The Health Care Blog

0 notes

Text

0 notes

Text

1 note

·

View note

Link

By BY MARINA BOLOTNIKOVA from Style in the New York Times-https://www.nytimes.com/2021/03/30/style/wedding-after-parties.html?partner=IFTTT For many couples who had scaled-down, virtual ceremonies, this year is all about the second celebration — an in-person reception with family and friends. The Year of the Wedding After-Party New York Times

0 notes

Photo

"The Year of the Wedding After-Party" by BY MARINA BOLOTNIKOVA via NYT Style https://ift.tt/31yzBQ0

0 notes