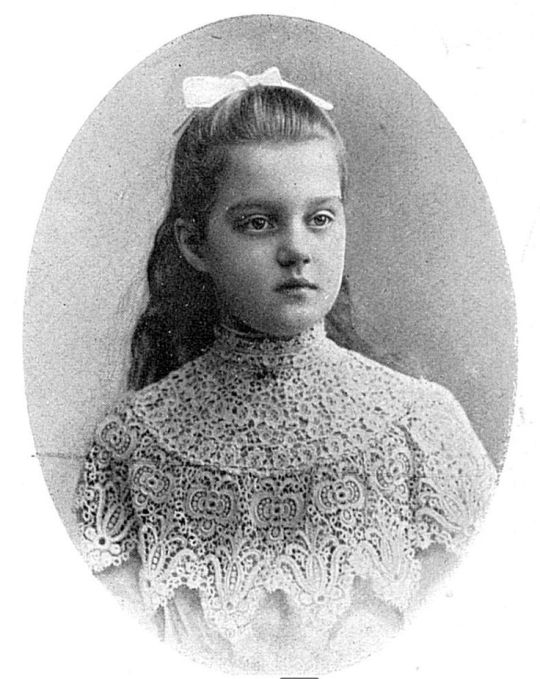

#marie pavlovna jr

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

I grieved for my father and frequently spoke to my uncle about him. He gave me patient but unsympathetic answers, speaking of my father without open criticism, but in a manner half jealous, half condescending, that hurt me deeply. It had been a year since the day father had been banished. His marriage had not been recognized. His wife had neither name nor title. One day, however, towards the end of summer, after what parleys I am not aware of, Uncle Serge told us that we could go to see him. The interview was to take place in Bavaria, in the villa of my aunt Marie, Duchess of Saxe-Coburg. (...)

My father, as was previously understood, kept the rendezvous alone. He talked a great deal and treated me almost as a confidential equal, but his distrait, preoccupied air went to my heart. I had determined to ask him news of his wife, but a kind of inexplicable timidity held me back. Finally, one day, I screwed up my courage and, with eyes lowered, uttered in a small trembling voice a sentence which I had prepared in advance. Father, who had not until then pronounced his wife’s name in my presence, was surprised and visibly touched. He rose, came over to me, and took me in his arms. This little scene bound us together forever. From that moment, in spite of my age, we became allies, almost accomplices, and my uncle’s efforts to attach me to him, to separate me in spirit as well as in fact from my own father, could not but fail.

The two brothers had some words on this subject during our stay—words which ended when my uncle shrugged his shoulders and announced that he considered himself as possessing all the rights which my father had given up. This was no idle boast; he did have the full rights of guardian over us and exercised these rights without consulting my father’s wishes on any point, and father, though he suffered a great deal from this state of things, was utterly powerless to act or protest.

"Education of a Princess" - Marie Pavlovna Jr.

#romanov#paul alexandrovich#imperial russia#imperial family#royalty#grand duke#olga paley#sergei alexandrovich#elizabeth feodorovna#marie pavlovna jr#dmitri pavlovich#grand duchess marie alexandrovna

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

The year previous, shortly after our return to St. Petersburg for the winter, Dmitri and I had noticed on father’s desk a new photograph in a small, gold frame. It was of a boy, four or five years old—a beautiful little boy with long curls and a dress that came down to his ankles. At our first chance, we asked father who it was. He turned the talk to other matters, avoiding response.

Later that year, we once went downstairs at tea-time and opened his study door, as we always did, without knocking. He was seated in his arm-chair, and in front of him, with her back to us, stood a woman. At our entrance she turned, and we recognized her. We did not know her name but had seen her. One day, at Tsarskoie-Selo, we were in a boat on the lake when she had passed near us along the shore, dressed in a white skirt and a red jacket with golden buttons. She was very pretty and had sent us smiles and amicable signs which we did not return.

I do not know what instinct now drove us to it, but we closed that door at once and fled in haste, despite my father's appeals. In the anteroom, a footman was holding a sable pelisse; in the air floated an unfamiliar perfume.

A vague jealousy gripped our hearts; we did not like this stranger penetrating into our personal sanctuary, our father's study. But he treated us always with the same tenderness; he seemed, indeed, now to wish to hold us more closely than ever to him.

"Education of a Princess" - Grand Duchess Marie Pavlovna Jr.

#marie pavlovna jr#paul alexandrovich#imperial russia#romanov#royalty#imperial family#19th century#grand duke#dmitri pavlovich#olga paley#vladimir paley

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

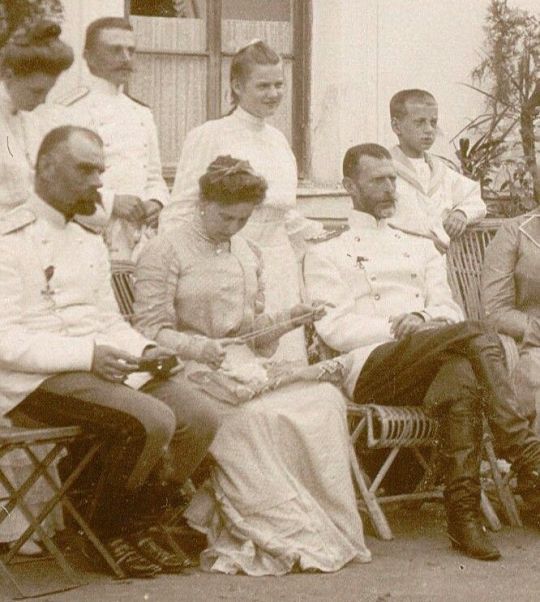

The summer of 1902, which was the last year of my childhood, we were not sent to Ilinskoie, but were kept at Tsarskoie-Selo. Father, now a General, commanded a cavalry division garrisoned at Krasnoie-Selo, some thirty miles away. We drove often to Krasnoie to see him, in a carriage drawn by four horses. The camp, the proximity of the military life, enchanted us.

Tsarskoie, where we were installed in our regular apartments, was alive with preparations for a great ceremony that was to take place in the month of August—the marriage of my cousin Helen with my uncle, Prince Nicholas of Greece—and numerous princely guests were expected. The King of Greece, my grandfather, and the Emperor, were to preside at the fêtes.

Dmitri and I were told we might attend the religious part of the ceremony, and for this occasion I was to wear my first court dress. The cut was discussed at great length and finally decided upon. It was a short dress in pale blue satin, tailored in the Russian manner. I was terrifically proud of it, and impatiently awaited the great day.

The guests began to arrive; we greeted our grandfather, King George of Greece, who had not been in Russia since our mother's death. He was very kind to us, but we saw that he and my father avoided each other scrupulously.

Throughout all the marriage festivities, in fact, my father was so nervous and preoccupied that I was moved to ask Mlle. Héline, to whom I rarely expressed my real concerns, what, in her opinion, was worrying him so. It must, she replied, be the sad memories aroused in him by this family reunion.

My uncle and aunt had also arrived. At a family dinner, some dispute arose between Uncle Serge and father that made a strong impression on me, although I cannot recall the subject of it. My uncle, wishing to put an end to the discussion, said with a forced smile as he rose from the table: "My boy, you are simply in a very bad mood; you ought to take better care of yourself." My aunt said nothing, casting anxious looks at us. We sensed a tension in the air which had never existed before. Without knowing why, I felt sorry for my father and never experienced greater tenderness towards him than I did during those days.

The day after the marriage my father went away. We went to the railway station with him, and when I saw him carried off by the train, I thought that my heart was going to break. I do not know why, but I felt as if I would never see him again.

"Education of a Princess" - Grand Duchess Marie Pavlovna Jr.

#romanov#paul alexandrovich#imperial russia#imperial family#royalty#grand duke#olga paley#elizabeth feodorovna#sergei alexandrovich#marie pavlovna jr#dmitri pavlovich#elena vladimirovna#nicholas of greece

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

The year of Ella and Serge's arrival in Moscow was marred by tragedy on both a personal and a national level. The first occurred that September, not long after Paul and Alexandra arrived at Ilinskoye to spend the late summer with them. One afternoon, the 21-year-old Grand Duchess, who was seven months' pregnant with her second child, followed the path down from the back of the house to the small wooden landing stage on the riverbank. As she was about to step into the waiting boat, Alexandra suddenly collapsed, seized unexpectedly and without warning by a convulsive fit. Carried unconscious back to the house where her frantic husband, brother- and sister-in-law felt impotent to help, and with doctors too far away in Moscow to be of immediate assistance, the village midwife was called. Alexandra was delivered of a tiny premature baby boy who, with attention focused on his comatose mother had been wrapped in blankets and left on a chair. Grand Duchess Alexandra Georgiyevna died six days later without ever having regained consciousness and, but for Serge, the baby might easily have preceded her to the grave. According to his elder sister Marie, who had been told the story by her English nurse, Nannie Fry, the infant who was to be called Dimitry had been wrapped in cotton wool and placed in a cradle heated with hot water bottles. But it was his uncle Serge who helped feed him and who gave him the bouillon baths the doctors prescribed, and it was through his care that the boy survived and grew stronger. Ten months later, in July 1892, Ella was telling Queen Victoria that '[Paul's] little boy was with us . . . he is a sweet little fat healthy baby with a merry character."

Ella: Princess, Saint And Martyr - Christopher Warwick

#paul alexandrovich#alexandra georgievna#elizabeth feodorovna#sergei alexandrovich#dmitri pavlovich#marie pavlovna jr#romanov#imperial family

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

A little later, we learned the worst. Since my father had married morganatically and without the Emperor’s permission, he was from that moment banished from Russia, and deprived of all his rights. All his official revenues were, moreover, confiscated.

Our aunt and uncle’s trip abroad, it now appeared, had been to Rome to meet our banished father; they would soon come back, and we would see them, we were told.

We found both of them overcome with sorrow; they cried over us a long time. My uncle sharply denounced Mme. Pistolkors; he accused her of having divorced a suitable husband to ruin my father’s life and future, and of having taken him from his children, who needed him.

The marriage, it seemed, had taken place secretly in Italy, and it was at Rome that my father learned from my uncle the Emperor’s verdict. They had discussed our future—which was now revealed to us, there in my uncle’s gloomy study, that painful afternoon, over a tea that nobody touched.

By the Emperor’s order, my uncle had been made our guardian. Our palace in St. Petersburg would be closed, and in the spring, we must move permanently to Moscow to live with my aunt and uncle, now our foster parents. In spite of the great sorrow that my uncle felt at his brother’s mésalliance, he could not conceal the joy he felt at the fact that from now on, he would be able to keep us entirely to himself. He kept saying: “It is I who am now your father, and you are my children!”

We sat there, Dmitri and I, blankly staring at him, saying nothing.

That year, for the first time in our lives, we did not hold our Christmas festivities at our palace on the Neva. It was the first sign of the change. My uncle and aunt, who inhabited the Governor General’s palace at Moscow, spent the holidays in a little palace belonging to the Crown, called Neskuchnoie, situated outside of the city on the banks of the Moskva.

We returned to St. Petersburg several days after the new year. Already, in our palace, things began to take on an aspect of ruin and neglect. Everybody had a sad face; servants without enough work to do trailed aimlessly through the big empty rooms, awaiting the moment when they would not be needed at all. Some of the older ones had already departed; little by little, the stables emptied. We saw each of these changes with a sort of tightening of the heart, and each face disappearing from the home reminded us that soon we too would be leaving it.

"Education of a Princess" - Grand Duchess Marie Pavlovna Jr

#romanov#paul alexandrovich#imperial russia#imperial family#royalty#grand duke#olga paley#sergei alexandrovich#elizabeth feodorovna#marie pavlovna jr#dmitri pavlovich

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

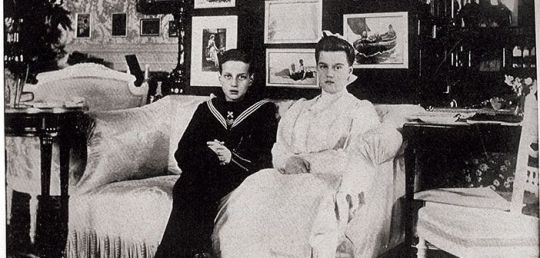

Dmitri and I lived in St. Petersburg with our father, in a palace on the Neva. (...) [We] lived with our nurses and attendants in a series of rooms on the second floor. This nursery suite, the domain of our infancy, was entirely isolated from the rest of the palace. It was a little world of its own, a world ruled by our English nurse, Nannie Fry, and her assistant, Lizzie Grove.

Until I was six years old I spoke hardly a word of Russian. The immediate household and all of the family spoke English to us.

Father used to come upstairs twice a day to see us. His love for us was deep and fond, and we knew it, but he never displayed towards us a spontaneous tenderness, embracing us only when bidding us good morning or good night.

I adored him. Every moment that I could be with him was joyous, and if for any reason a day passed without our seeing him, it was a real disappointment.

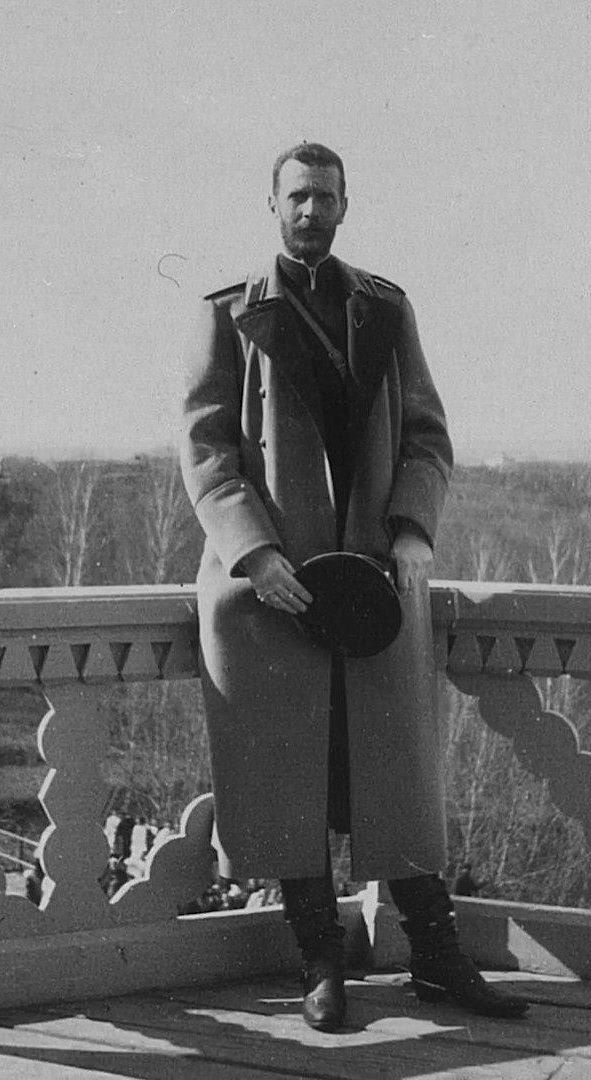

He commanded at this time the Imperial Horse Guards. I recall him most distinctly in the dress uniform of that regiment. It was a truly magnificent uniform—all of white with gold braid. The gilded helmet was surmounted by the imperial eagle.

My father was tall and thin with wide shoulders. His head was small; his rounded forehead a little pinched at the temples. For so large a man his feet were remarkably small and his hands were of a beauty and delicacy that I have never since discovered in the hands of a human being.

He was uniquely charming. Every word, movement, gesture, bore the imprint of distinction. No one could approach him without feeling drawn to him; and this remained always true, for age could not dim his elegance, banish his gaiety, or embitter the goodness of his heart.

His humour ran sometimes to fantastic, enchanting lies which he maintained to the uttermost. He, deftly slipped under our pet hare one Easter, for instance, an ordinary hen’s egg and succeeded in making us believe that our tame hare had laid the egg.

"Education of a Princess" - Grand Duchess Marie Pavlovna Jr.

#paul alexandrovich#romanov#imperial russia#imperial family#royalty#19th century#grand duke#marie pavlovna jr#dmitri pavlovich

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

I do not remember my mother. She died giving birth to my brother Dmitri, who was born when I was one and a half years old. She was Princess Alexandra of Greece, daughter of King George and Queen Olga, who had been born a Grand Duchess of Russia. (...)

Her death at the age of twenty-one prostrated the family and was mourned throughout Russia. The peasants of the region gathered in crowds; they raised her in her coffin to their shoulders and bore her to the railway station, a distance of some eight miles. It was a funeral march, but it seemed rather such a procession as welcomes to her home a young bride; everywhere she passed were flowers.

My mother was adored by all who knew her. From the photographs that remain of her, I can see that she was beautiful; her features are small and finely wrought; the outline of her face has a softness of contour almost infantile; her eyes are large and a little sad, and the whole of her person reflects a spirit of particular gentleness and charm.

My brother came into the world so small, so feeble, that no one thought he could live. His arrival went almost unnoticed amid the grief and disorder aroused by my mother’s desperate condition. My old English nurse has told me of having found the newborn child bundled haphazardly among some blankets on a chair, as she came running to get news of my mother. It was only after my mother was dead that they began to pay attention to Dmitri.

At that time, baby incubators were rare; they wrapped him in cotton wool and kept him in a cradle heated with hot-water bottles. Uncle Serge, with his own hands, gave him the bouillon baths that the doctors prescribed, and the child gained in strength and began to grow.

He and I were left at Ilinskoie for several months until he was judged strong enough to travel; we were then returned to our home in St. Petersburg, where our father awaited us.

All of this was, of course, in a past beyond my conscious recollection, and has been told to me by other people. Of my own memories, the first, I am certain, goes back to a day in my fourth year when, standing on the seat of a black leather armchair, I was having my picture taken. I recall how the starched pleats of my little white dress scratched my arms and how the silk of my sash creaked. My head was just the same height as the back of the chair on which the photographer had placed me; my feet, clad in pumps with silken pompons, rested on a leopard’s skin.

"Education of a Princess" - Grand Duchess Marie Pavlovna Jr.

#marie pavlovna jr#dmitri pavlovich#paul alexandrovich#romanov#imperial family#russian imperial army#elizabeth feodorovna#sergei alexandrovich

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Grand Duchess Marie Alexandrovna on meeting the Hohenfelsens

(safe to say she was not impressed 🤣)

Paris, 16 June 1908

The young Swedish couple" has arrived in our hotel. Little Marie is a very sedate and calm little person, but she poured her heart out to Baby: she feels it terribly meeting here her step-mother and suffers greatly under it. As to poor little Dmitry, he is in perfect despair. He hates the whole thing and loathed the idea of seeing his new Geschwister [siblings]. He comes to me to talk about it.

Of course Uncle Paul and wife manquent de tact [are tactless] in every way: for instance, last Tuesday he arranged a big luncheon with quantities of his French acquaintances and asked us too. It was the first time poor Dmitry went to his house here and Uncle Paul presented him to all the guests as "mon fils aine" [my eldest son]. The boy simply se tordait de désespoir [curled up in despair], we observed it all and in the middle of this unknown company appeared these second children and all the affected French people went into loud ectasies about them [at this time, Vladimir was 11, Irina 4 and Natalie 2], whilst poor Dmitry was pale with concentrated rage and moral suffering.

Marie told Baby that she never would have come here, had she known, how it would be. And people are wonderfully taktlos. They all praise her to the skies when they talk to me, cette charmante Comtesse Hohenfelsen, "elle est adorable, cette femme". Vous trouvez [that charming Countess Hohenfelsen. She's adorable, don't you think?]. I answer, oh! Bien pour moi, c'est très pénible [for me it's all very painful] and I tell them a few truths. Then they at once turn the conversation, as French people hate when they are found at fault et ne désirent pas du tout en savoir d'avantage. [and don't want to be wrong in any way].

As to Uncle Paul, I cannot support at all him here; his whole attitude and tone I find detestable, I don't show it, à quoi bon and I am simply polite with his wife, like with any lady in society I don't care for. I simply writhe when I see in his house portraits of my mother, what a desecration! And he pointed them out to me! I thought one moment I would like to insult him before all his idiotic French guests.

"Dear Mama" - Diana Mandache

This is what I love about digging into original sources. When we read Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna's memoires, the idea we get is that she always had a pleasent relationship with her stepmother, but here (at least according to Maria Alexandrovna, who clearly still held a deep resentment towards her brother and his second wife) it seems things were not so smooth.

It's also interesting (and sad) to notice how she doesn't really consider Grand Duke Paul's children from his second marriage worthy of any note and is even annoyed that the French fawn over them and that Grand Duke Paul introduces Dmitri as his "eldest son", which seems to imply she doesn't consider Vladimir to be his son at all.

It kind of shows what the rest of the family thought about Grand Duke Paul's second family: so irrelevant that it was as if they didn't exist.

#romanov#paul alexandrovich#imperial russia#imperial family#royalty#olga paley#grand duke#grand duchess maria alexandrovna#natalie paley#vladimir paley#irina paley#morganatic marriages#marie pavlovna jr.#dmitri pavlovich#beatrice of coburg

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Russian party left Balmoral very early on the morning of 11 October loaded with gifts and good advice, and more gifts reached them on their arrival in London. They stayed for a few days, then began the long return journey, which was broken by a stay in Darmstadt where the Queen sent more presents, this time for Marie and Dmitri.

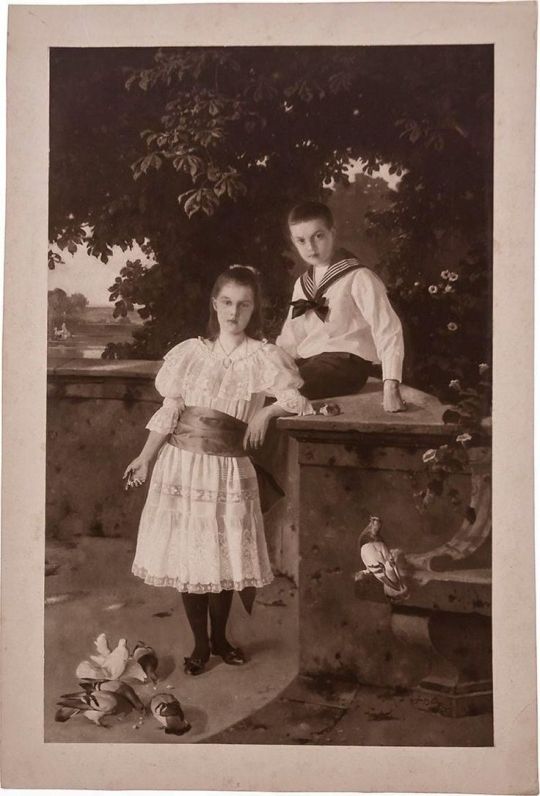

The visit to Darmstadt was cut short by a summons from St Petersburg, and, sooner than they had intended, the party left for home. On 20 November Elisabeth wrote to her grandmother: 'Paul's children put on your frocks looking so sweet, they are flourishing thank God - He has just been photographed with them, if a success would you like to have some of their portraits - they are such sweet pretty little things.'

A photograph duly followed, with a letter from Pavel, which is still preserved in one of the Queen's albums. 'You had the kindness during my stay in Scotland to ask me for a photograph of my children. I hasten to carry out your request by sending the most recent photograph... taken at my home shortly after my return to St. Petersburg. It is with profound gratitude that I often think of my charming stay at Balmoral and of the extreme kindness which Your Majesty showed to me. On returning I found my children, thank God, grown and in good health. The little girl was enchanted with the doll which Your Majesty had the extreme kindness to send her, and knows perfectly well from whom she came. The little white dress she wears every Sunday.'

Romanov Autumn - Charlotte Zeepvat

#queen victoria#paul alexandrovich#romanov#imperial russia#imperial family#royalty#19th century#dmitri pavlovich#marie pavlovna jr.#elizabeth feodorovna

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Last Years in Paris and Return to Russia

Meanwhile Marie and Dmitri grew up without their father. In 1907 Marie became engaged to Prince Vilhelm of Sweden: she would say later that the engagement was arranged by her aunt against her will but there is no sense of this in letters written at the time. Her memory may have been coloured by the subsequent failure of the marriage. But at the same time, any pleasure she might have felt in the engagement was severely shaken by her father's reaction: Pavel refused to attend the ceremony unless he could bring his wife. He set two conditions.

First, he wanted to see Olga accepted at Court. 'Could you really think that I would leave my wife alone,' he asked the Tsar, 'she whom everyone here loves and respects. I did not make the break and sacrifice everything to let her then be humiliated and insulted without reason.' Second, he wanted the wardship of his children ended, and he refused to be seen on the sidelines of an engagement over which he had had no say. From his own standpoint his arguments must have appeared quite reasonable but the family did not see it that way. "What incredible heartlessness!', the Tsar's sister Ksenia wrote in her diary. "I feel so sorry for poor Maria - he's spoilt everything for her!' That October, the Tsar had a slight change of heart, and allowed Pavel and Olga to visit St Petersburg together to see Marie and Dmitri.

Marie was married in 1908 and things went wrong very quickly. The circumstances of her upbringing had made her both selfish and difficult, and her behaviour in her new country earned a bad reputation which worried her father. In 1911 Olga's younger daughter [Marianne] was divorced after only three years of marriage; when Marie also announced her plan to leave her husband and child Pavel must have wondered if the next generation was not following his example rather too keenly.

But Dmitri seemed more promising, and stood high in the favour of the Tsar and Tsaritsa. On 6 January 1912, after the traditional 'Blessing of the Waters' in St Petersburg, he took his Oath of Allegiance, and Nicholas II marked the occasion by announcing that Pavel and his family could return to Russia for good. Pavel still owned his palace in the city but he wanted to build a house at Tsarskoe Selo based on his Paris home, for his family and his art collection. His son Vladimir also returned to attend the Corps des Pages. For the others, however, the move took longer, and their house was not finished until May 1914. Within months the First World War began.

"Romanov Autumn" - Charlotte Zeepvat

Theory time! Sooo, it was around 1912-13 (when Grand Duchess Olga was 17-18) that the idea of her marrying Dmitri was tossed around and there are even rumours that they became engaged (although briefly). There is also the possibility that Tsar Nicholas II was playing around with the idea that, if Alexei didn't make it to adulthood, a marriage between Olga and Dmitri would be the perfect alternative, as Olga was the eldest daughter and Dmitri could act as a sort of Regent or Prince Consort to appease the most conservative factions who didn't necessarily want a woman to rule Russia.

Could it be that the pardon Nicholas II granted to his uncle (Dmitri's father) around this time was related to this plan? I think it makes sense that Nicholas would want to bring Dmitri's father back into the country if he was thinking of marrying him to his daughter, but it's just a theory. :)

#romanov#paul alexandrovich#imperial russia#imperial family#royalty#dmitri pavlovich#marie pavlovna jr.#nicholas ii#olga nikolaevna#tatiana nikolaevna#otma#otma marriage plans#romanov theories

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Funeral of Grand Duke Sergei Alexandrovich

My uncle was buried on the morning of the twenty-third of February. My uncle’s brothers, as well as his sister-in-law, the Dowager Empress, expressed a desire to attend but found at the last moment that they could not do so. Disorders were feared; strikes were breaking out one after another in all the great industrial centers. Any gathering of royal persons would only invite new catastrophes. A cousin of my uncle, the Grand Duke Constantine, took the risk, and so did the Duchess of Saxe-Coburg, her daughter Beatrice, and the Grand Duke of Hesse and his wife. Finally, my father, in his banishment now installed in Paris, asked the Emperor’s permission to come. It was granted.

Dmitri and I went to see him at the railway station and received him with sobs, which could not lessen the joy we had at seeing him again. We took him back to the house. The meeting between him and his sister-in-law was painful.

My aunt had conceived the idea of building a chapel in the crypt of the Miracle Monastery to shelter the remains of my uncle. While waiting for the chapel to be built, she obtained permission to place the coffin in one of the convent churches.

The funeral service was celebrated with great solemnity. Officers with drawn swords and sentinels were stationed around the bier. The Archbishop and the high clergy of Moscow celebrated the mass, a service so long and tiring that I almost fainted, and my father had to take me out. The church was full of people; wreaths and flowers were heaped around the coffin and on the steps of the catafalque. By this time, I had reached such a degree of physical lassitude that I could hardly think or feel anything. We had lived for six days in a state of nervous tension that never relaxed. At the end of the service, the coffin was carried to one of the little churches of the monastery, and here, for forty days and nights, prayers were said. We attended them every evening.

Some days later, my father and other members of the family departed. Little by little, life took up its normal course. "Normal" is an expression only relatively exact, for my aunt never left off her mourning and rarely went out.

"Education of a Princess" - Grand Duchess Marie Pavlovna Jr.

#romanov#paul alexandrovich#imperial russia#imperial family#royalty#grand duke#sergei alexandrovich#elizabeth feodorovna#funeral#marie pavlovna jr.#dmitri pavlovich#ernest ludwig of hesse#russian history

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Life at Bolougne-sur-Seine - Part 1

It's clear that, until the age of eight, Natalie [Paley] grew up in an overprotected world - where tenderness and culture were inseparable. The large house in Boulogne, which had sixteen employees, was an unassailable fortress. From the guardian couple Gustave and Joséphine, to Jacqueline Theureau, the Berry governess who watched over her since her birth, without forgetting Miss White, the English teacher, all defended the little girl against attacks from the outside world. The surrounding nature itself seemed courteous and civilized. The paths were swept every morning, the flowerbeds trimmed, and the flowers watered. (...) Their life in France was the result of a painful freedom in many respects but both [Grand Duke Paul and Olga] knew what it would cost them to break the imperial rules and accepted the consequences, which explains in large part how available they were for their children. If they had remained in Russia, Grand Duke Paul, a professional soldier, would not have been able to participate so closely in their education. The fragility of his health must also be taken into account. For years, he suffered, according to his doctors, from a liver disorder - when in reality it was a stomach ulcer and he had to divide his time between rest and life in the open air. That was the reason why every morning, dressed in an old tweed cape, he took Irene and Natalie - the first was always his favourite, even if he didn't want to show it, because she reminded him so much of his wife; as for the younger one, she amused him a lot with her witty quips in the Bois de Boulogne, just a few meters from their home. When Marie, his eldest daughter, was in France, she joined their group with her old fox terrier, Martzka. At the time, deer were still seen coming out of the thickets.

Natalie Paley: Princesse en Exil - Jean-Noel Liaut

#romanov#paul alexandrovich#belle époque#boulogne billancourt#early 20th century#natalie paley#irene paley#irina paley#marie pavlovna jr.#olga paley

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Grand Duchess Marie Pavlovna recalls her visits to her father in Paris

The next day we had lunch with my father. I saw at last the home to which for years my thoughts had flown, and met for the first time my half-brother and my two little half-sisters, the eldest of whom was six years old. The house at Boulogne was comfortable, peaceful, and simple. It was a home. My father could have no possible regret for the great palace, cold and bare, that he had left at St. Petersburg. He and his wife were ideally happy.

Seeing them thus side by side in the home they had made together, there passed from my heart the last trace of all ill feeling that I had harboured towards my stepmother. Thereafter we called each other by name as friends do, and employed the familiar “tu and “toi” in addressing each other. This made my father very happy. (...)

Before settling in the country again, at the end of that winter, I went to visit my father at Boulogne. I loved these visits; the simplicity and peace of my father’s household did me good after all the publicity with which I was so constantly surrounded in Stockholm. We went about, and sometimes attended the theatres, but more often stayed home in the evenings, my father reading aloud while my stepmother and I embroidered.

Between my father and myself the ties of affection had strengthened with the years. When, therefore, during this visit, he felt it necessary to question me severely as to my escapades in Sweden, of which exaggerated accounts had somehow reached him, I was cut to the quick. From him I learned for the first time, with amazement, the cruel interpretation that was being put upon my childish foolishness; from him, heard the “reputation” I was getting. It was my first direct experience with the malevolence of humanity, and I was profoundly depressed.

Long after my father had forgotten this conversation, I thought of it often, and always with a tightening of the heart. (...)

Late in the autumn I took my son with me to Paris to see my father, whose position now had changed in several respects. The Emperor had not only called him back to Russia to be Present when Dmitri took the oath of allegiance and joined a regiment, but had upon the same occasion lifted my father’s banishment. I found him and his wife delightedly making plans to build a house on an estate at Tsarskoie-Selo, the imperial residence, Their son, my half-brother, had already been sent to St. Petersburg, and entered in the Ecole des Pages, a military school.

I decided to open my heart to my father and tell him all my difficulties. He listened patiently but was firmly opposed to the idea of a divorce. In his opinion, apart from all moral and political aspects of the case, I was much too young to be alone in the world; and my stepmother strongly supported him in this opinion.

Education of a Princess - Grand Duchess Marie Pavlovna Jr

#romanov#paul alexandrovich#imperial russia#imperial family#royalty#william of sweeden#swedish royal family#olga paley#marie pavlovna jr.#lennart of sweden#grand duke

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Uncle Serge and Aunt Ella came to see us for a few days before departing for abroad. They too seemed sad, cast down; there was that in their attitude towards us—my aunt's particularly—which aroused in us a vague presentiment.

One evening I was seated before my desk doing my lessons when Mlle. Héléne came into the room and handed me an envelope on which I recognized my father's handwriting. I tore it open quickly, spread out the letter, and started to read.

From the very first sentence, I understood that my father was about to announce something terrible. At first, I could not understand what it was; then, as I read, I knew. Mlle. Héléne, hovering near, came close and wanted to take me in her arms. I lifted an empty gaze towards her and re-read the letter.

My father announced his marriage to a person he called Olga Valerianovna Pistolkors. He wrote of how much he had suffered from loneliness and how great his love was for this woman, who would make him happy. He added that nothing could ever lessen his affection for us and that he hoped to keep ours. He asked us to think of his wife without ill feeling.

The sheet of paper fell to the floor, and I hid my head in my hands and broke into sobs. My governess drew me over to the couch and took me on her knee.

My dominating impression was that my father was dead to me. My sobs became a kind of nervous hiccupping which nothing could stop for hours. I didn't think; I didn't move.

Then little by little, my ideas became clearer. Thoughts began to run rapidly in my mind. Egotism: how could my father do this, he who lacked nothing, who led so agreeable a life; who had us, both of us, alone to himself? So! We possessed no importance in his life? How could this person dare to take him from us; she knew, she ought to know, how much we loved him.

"I'll show her how I detest her!" I told Mlle. Héléne.

"My dear," she said, "you ought not to talk that way about your father's wife. It would cause him much pain if he heard you."

"Do you think—will he come back for Christmas?" I asked.

"Perhaps, my dear," said Mlle. Héléne, with a slight hesitation which I was quick to observe.

"Oh, say 'yes,' say 'yes'; he must come back for Christmas!" I insisted passionately. And poor Mlle. Héléne did not know what to say.

Meanwhile, Dmitri was reading a letter similar to mine in his own room. We saw each other, hours afterwards, through eyes swollen with weeping, and sought to speak with lips still trembling; only, at the first attempt, to burst out crying anew. The long, sorrowful days that followed left a lasting trace on my heart. It was my first real sorrow, the first wound that life dealt me.I devoted a great deal of time to composing a reply to my father’s letter, covering numberless sheets of paper, only to throw them away; nothing that I could write satisfied me. It was too sentimental, or too cold.

I must finally have decided on the sentimental version; for, although I don’t remember the text, I recall having been moved to tears in re-reading what I had written. Mlle. Héléne approved it, but reproached me for not having put in a kind word to my father’s wife. I refused to change anything in the letter. She preached to me a long time. Then, to give her satisfaction, at the bottom of the letter I added a sentence, obscure enough, which meant that I harbored no ill feeling against my stepmother. I remember having added these words in a different handwriting, even a little hesitant; and my father ought certainly to have perceived the difference.

"Education of a Princess" - Grand Duchess Marie Pavlovna Jr.

#romanov#paul alexandrovich#imperial russia#imperial family#royalty#grand duke#olga paley#sergei alexandrovich#elizabeth feodorovna#marie pavlovna jr.#dmitri pavlovich

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pavel could be an enchanting father, with a slight air of distance about him which only increased his attractiveness. 'His love for us was deep and fond, and we knew it,' his daughter recalled, 'but he never displayed towards us a spontaneous tenderness, embracing us only when bidding us good-morning or good-night.' The children lived apart in the second floor nurseries of the palace, which he visited twice a day. His imagination could be a delight: once, at Easter, he slipped a hen's egg under their pet hare and convinced them that the hare had laid it. 'At Christmas he was particularly joyous,' Marie wrote, 'and Christmas was the peak of our year." But once Christmas Eve was over, with the decorated tree, the presents, and the dangerous thrill of letting off indoor fireworks, Pavel would leave the children in the palace and go away to spend the rest of the holiday with his brother and sister-in-law in Moscow and this too was typical of him as a father. His attention to the children was erratic. He was absent for much of the time, and every summer sent them to their uncle and aunt at Ilinskoe.

"Romanov Autumn" - Charlotte Zeepvat

#paul alexandrovich#romanov#marie pavlovna jr.#imperial russia#royalty#19th century#grand duke#fatherhood

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Marie Pavlovna and Dmitri are formally introduced to their stepmother

For a long time, my father had wanted to bring his wife to Russia, even if it were only for a short visit, but the court had always forbidden it. Now at last, permission was given. My father and his wife arrived in St. Petersburg and settled for fifteen days at our old palace on the Neva.

By this time, his situation had been somewhat regulated. His wife now bore the Bavarian title of Countess Hohenfelsen, and their marriage had been recognized by the Crown. The Countess’s eldest daughter by her first marriage was expecting a child. This was the reason given in the appeal to the Emperor—a mother’s desire to be with her daughter at such a time.

My father wished, moreover, that we should meet and know his wife and also that she should re-establish her contact with the society of the capital.

My aunt opposed the whole idea, but the Emperor could not find it in his heart to withhold permission. Consequently, we went one day to St. Petersburg, accompanied by my aunt, who was glum. My uncle, she felt, would have known how to prevent this useless, almost unseemly meeting.

My heart beat hard and rapidly as I stepped through the large glass doors of the vestibule. Nothing seemed changed during the few years of our absence, not even the smell; only the dimensions of the rooms—they seemed to me to have become smaller. My father smiled at us gaily from the top of the stairway.

We ascended. As Father bent over Aunt Ella’s hand and turned to kiss us, I caught, reflected in the mirror from the next room, a glimpse of Countess Hohenfelsen’s profile. Her face was rigid and pale from emotion.

My father preceded us; a few more steps and I faced his wife.

She was beautiful, very beautiful. An intelligent face, with features irregular but fine; a skin remarkably white, contrasting strikingly with the dark violet of a velvet dress trimmed at the neck and sleeves with flounces of old lace. All this I took in at a glance, and I can still see her as she stood there.

Father made the introductions. The Countess greeted my aunt with a profound curtsy and turned to me. We were both embarrassed; I did not know how to greet her. Finally, I timidly put forth my cheek.

Tea was served in my father’s study. The Countess did the honors. Her bejeweled hands passed adroitly above the white cups bordered with red and marked with my father’s monogram. But in spite of all her efforts, and those of my father, the conversation languished. My aunt had decided to lend this interview a purely official character, and she was succeeding.

Finally, having exhausted all possible topics, we passed into the large English drawing room. Here, upon the billiard table, were spread the jewels, the furs, and the laces of my mother. My father wanted to divide them between Dmitri and myself before my marriage.

In silence, my father and aunt bent over the dusty jewel cases containing the old-fashioned settings and the tarnished precious stones, uncleaned and neglected now for almost twenty years. How many memories—of which they no longer dared to speak—these objects brought to light! This fortune without luster, spread out in front of me, half of it soon to be mine, did not impress me at all. Jewels were a part of our attire; they represented to me no more than a customary ornament. I saw no material value in them.

While my father and my aunt discussed the way of dividing the jewels, the Countess and I examined the furs. Twenty years of naphthalene had not beautified them; the Countess offered to take them to Paris and have them restored. We spoke of my trousseau and of the Paris dressmaking houses. Before we parted, she said that she would like to give me something in memory of our first meeting. What did I wish? I did not know what to answer, but my glance fell upon the necklace of amethyst balls she was wearing, and I replied that I would like to have such a necklace as that. She sent it to me. I wear it still.

My father had hoped that this first meeting would be followed by others more intimate. But my aunt would not hear of this. We went once more to St. Petersburg, but again escorted by my aunt, and the second conference was as chill and formal as the first. Father, seeing the uselessness of such efforts, did not persevere. Only one thing about the meeting comforted me: I felt that in his new life, he was at peace and happy.

And I determined to find in marriage at least one advantage: no one then, I thought, would be able to prevent me from seeing my father.

Education of a Princess - Marie Pavlovna Jr.

#romanov#paul alexandrovich#imperial russia#imperial family#royalty#grand duke#olga paley#elizabeth feodorovna#marie pavlovna jr.#dmitri pavlovich

9 notes

·

View notes