#mamadou diagne

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Mamadou Diagne by Francesca Beltran for Balmain Resort 2024 Campaign

340 notes

·

View notes

Text

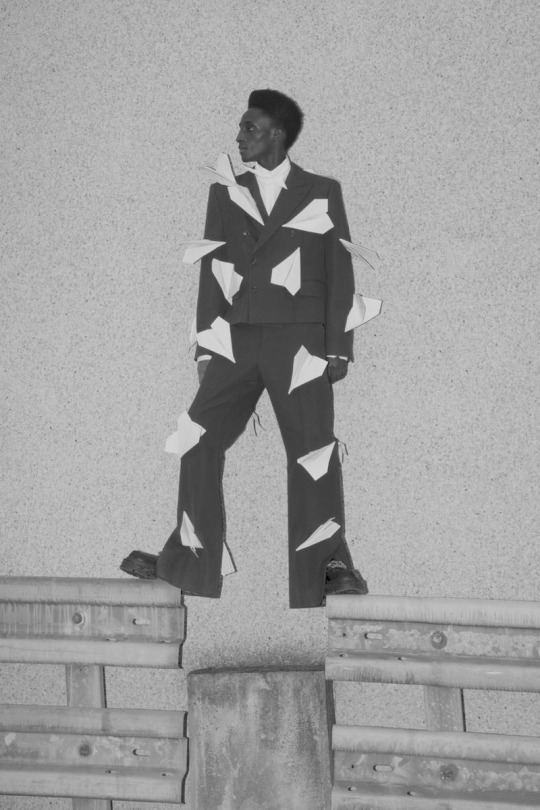

Mamadou Diagne for Baldessarini, Spring 2023

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Review: Three Revolutionary Films by Ousmane Sembène on Criterion Blu-ray

Together, these films constitute a complex, interlocking portrait of Senegal’s past and present.

by Derek Smith May 30, 2024

Where Ousmane Sembène’s first two films, 1966’s Black Girl and 1968’s Mandabi, each focus on myriad struggles faced by an individual during Senegal’s early post-colonial years, his follow-up, Emitai, takes a more expansive view of the effects of colonialism two decades earlier. Centering on the defiance of a Diola tribe during World War II, 1971’s Emitai sacrifices none of the immediacy and urgency of Black Girl and Mandabi. Indeed, the film is perhaps an even more damning and incisive take-down of French colonial rule.

Painting a concise and pointed portrait of oppression in broad, revolutionary strokes, Emitai exposes the modern form of slavery that was France’s conscription of Senegalese men to fight on the deadliest frontlines of European battlegrounds. The film simultaneously details the meticulous taxation methods the French employed during this period, which, in attempting to seize a majority of tribes’ rice supply to feed their troops, is tantamount to starvation warfare.

Sembène, however, is less interested in the methodologies of the oppressor than in the unwavering, often silent protest of the Diola people, especially women, in the face of forces that threaten to wipe out the rituals and traditions that define them. In depicting the tribe’s refusal to turn over their rice not as a means to avoid starvation but as a matter of preserving the central value rice has in their cultural heritage, Sembène adds new dimensions to the conflict and complexity to the resistance of the villagers. The inevitable tragedy that concludes the film is quite the gut-punch, but in counterbalancing it with the rebellious enacting of funereal rites by the village women, Emitai becomes equal parts an indictment of colonial violence and a celebration of resilience and self-empowerment through revolutionary means.

In 1975’s Xala, Sembène presents a searing, often hilarious satire of the greed, corruption, and impotence of the new Senegalese governmental leadership following the eradication of French colonial rule. In the opening scene, we see government officials throw out the current French leaders and proudly proclaim that Africa will take back what’s theirs. This moment of triumph, which includes the removal of statues and busts of various French leaders, is swiftly undercut when the Senegalese officials each open a briefcase packed to the brim with 500 Franc bills.

This sequence, laden with anger and biting humor, is indicative of Xala’s absurdist, comedic tone. And as the film shifts its focus to one corrupt official in particular, El Hadji (Thierno Leye), who upon marrying his third wife is cursed with impotence, its satire becomes more metaphorical than direct. Sembène uses El Hadji’s gradual downfall to reflect the moral and political failings of the entire bourgeois class that came into power under the government of President Léopold Sédar Senghor. Through Sembène’s sly, cutting use of irony, claims of modernity and equality under a new “revolutionary socialism” are revealed to be empty promises, barely concealing the anti-feminist and pro-capitalist motives lurking behind them.

Sembène’s critique of a supposedly freed Senegal is intensely savage when it comes to unveiling the hypocrisies of a patriarchal leadership that betrayed the trust of the people it was supposed to aid and protect. Building to a conclusion that’s as funny and gratifying as it is pitiful and physically revolting, Xala captures the continuing repercussions of colonialism and how the forced delusions of a nation would leave its people perversely feeding on one another.

With 1977’s Ceddo, set in Senegal’s distant pre-colonial past, Sembène follows the conflicts between a growing Islamist faction of a once animistic tribe and the Ceddo, or outsiders, who refuse to convert and give up their animistic rituals and beliefs. This is certainly the most didactic entry in this set, but it’s enlivened by the sheer precision of its dialectical oppositions, through which the many hypocrisies of religious fundamentalism and colonization are laid bare.

Ceddo also reveals the complex intersectionality of religions and cultures that were at play in Senegal long before its colonization. Along with the Muslims, who were attempting to seize political power through religious conversions, white Christians and Catholics are present in the form of priests, missionaries, gun runners, and slave traders. The latter are silent through much of the film, but their presence—much like the white French adviser who remains in constant contact with the Senegalese politicians in Xala—speaks to the monumental power and influence whites held in Senegal even before colonialist rulers took over.

While the film’s subject is historical, Sembène draws clear parallels between the past and the post-colonial present of 1977, with the condescending paternalism of the Muslims, particularly the power-hungry imam played by Alioune Fall, mirroring that of the colonialist French. And rather than using traditional Senegalese music, Sembène employed Cameroonian musician Manu Dibango to compose a jazz-funk score that even further connects the events in Ceddo to the time of its release in the late ’70s. For whenever Sembène sets his film, he’s steadfast in his mission to draw meaningful correlations between Senegal’s past and present—each equally integral to the story of the country he loved and helped to define.

Image/Sound

All three transfers come from new 4K digital restorations and they, by and large, look terrific, with vibrant colors and rich details, especially in the costumes and extreme close-ups of faces. There are some shots where the grain is chunkier and the image isn’t quite as sharp, and the Ceddo transfer shows some noticeable signs of damage in several different scenes, but these are mostly minor, non-distracting imperfections. The mono audio track bears the limitations of the production conditions, so some of the dialogue in interior scenes is a bit echoey though still fairly clear. Meanwhile, the music comes through with a surprising robustness.

Extras

A new conversation between Mahen Bonetti, founder and executive director of the African Film Festival, and writer Amy Sall covers a lot of ground in 40 minutes. The two discuss Ousmane Sembène’s early career and discovery in the West before delving into his use of cinema as “a liberatory force” and his sly, caustic use of irony. The only other extra on the disc is a 1981 short documentary by Paulin Soumanou Vieyra in which Sembène espouses much of his philosophy of filmmaking, particularly the importance of understanding history and political complexities of the society one chooses to depict. (Amusingly, Sembène’s wife casually insults American moviegoers, as well as complains about her husband putting film before family.) The stunningly designed package also comes with a 26-page bound booklet containing an essay by film scholar Yasmina Rice, who touches on Sembène’s humor, feminism, and politically charged subjects, while forcefully pushing back against the notion that the director wasn’t much of a formalist.

Overall

These Ousmane Sembène films from 1970s brim with a revolutionary passion and, together, constitute a complex, interlocking portrait of Senegal’s past and present.

Score

⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️

Cast

Andongo Diabon, Michel Renaudeau, Robert Fontaine, Ousmane Camara, Ibou Camara, Abdoulaye Diallo, Alphonse Diatta, Pierre Blanchard, Cherif Tamba, Fode Cambay, Etienne Mané, Joseph Diatta, Dji Niassebaron , Antio Bassene, M’Bissine Thérèse Diop, Thierno Leye, Seune Samb, Younouss Seye, Miriam Niang, Fatim Diagne, Dieynaba Niang, Makhourédia Guèye, Tabara Ndiaye, Alioune Fall, Moustapha Yade, Mamadou N’Diaye Diagne, Nar Sene, Mamadou Dioum, Oumar Gueye.

#Andongo Diabon#Michel Renaudeau#Robert Fontaine#Ousmane Camara#Ibou Camara#Abdoulaye Diallo#Alphonse Diatta#Pierre Blanchard#Cherif Tamba#Fode Cambay#Etienne Mané#Joseph Diatta#Dji Niassebaron#Antio Bassene#M’Bissine Thérèse Diop#Thierno Leye#Seune Samb#Younouss Seye#Miriam Niang#Fatim Diagne#Dieynaba Niang#Makhourédia Guèye#Tabara Ndiaye#Alioune Fall#Moustapha Yade#Mamadou N’Diaye Diagne#Nar Sene#Mamadou Dioum#Oumar Gueye#The Criterion Collection

0 notes

Text

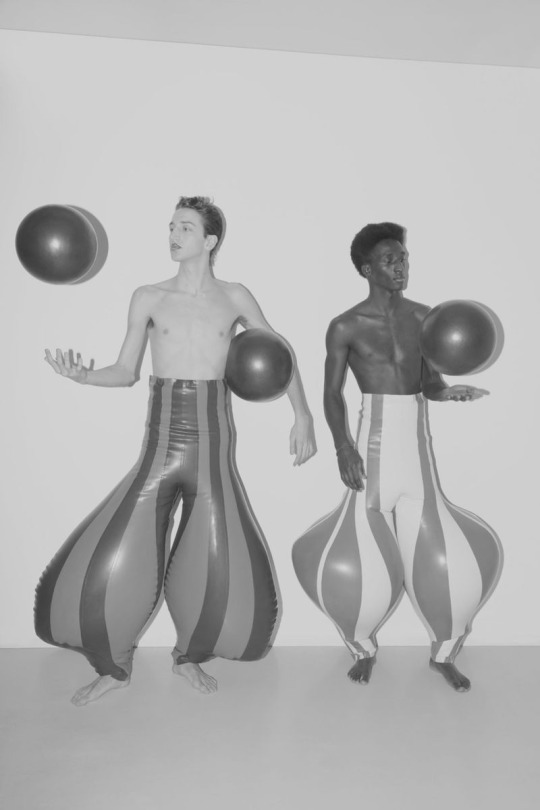

Jaume Marti, Mamadou Diagne, Tsubasa by Jonathan Llense for Dapper Dan Magazine April 2023

158 notes

·

View notes

Text

🌟 Beach Soccer Stars 2024 🌟 Cet événement prestigieux met à l'honneur les acteurs d'exception du Beach Soccer mondial ! 🇸🇳 Le Sénégal est fier de compter 6 nominés : 🏆 Meilleur entraîneur : Ngalla Sylla 🏆 Meilleur gardien : Al Seyni Ndiaye 🏆 Meilleur joueur : Raoul Mendy, Jean Ninou Diatta, Seydina Mandione Diagne et Mamadou Sylla Félicitations à tous les nominés et bonne chance ! #BeachSoccerStars2024 #NgallaSylla #AlSeyniNdiaye #RaoulMendy #JeanNinouDiatta #SeydinaMandioneDiagne #MamadouSylla

0 notes

Text

Déblocage des comptes des entreprises de presse : » La mesure n’est pas encore effective », selon Mamadou Ibra Kane

Le président du Conseil des Diffuseurs et Éditeurs de Presse du Sénégal (CDEPS), Mamadou Ibra Kane, a annoncé une décision salutaire du Directeur général des Impôts et Domaines (DGID), Abdoulaye Diagne dans le secteur de la presse. Ce dernier a ordonné le déblocage des comptes bancaires des entreprises de presse, une mesure qui devrait soulager […]

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Le Sénégal sans Bibliothèque nationale: La Direction du Livre en léthargie.( Par Abdoulaye Mamadou Guissé).

Le Sénégal sans bibliothèque nationale, sans de Foire du livre, sans Grand Prix littéraire du Chef de l’Etat, décadence du Fonds de l’Edition, léthargie des Centres de lecture, népotisme aggravé, la Direction du Livre et de la lecture à auditer. 11 ans de léthargie. Le Sénégal est le pays de Senghor, d’Amadou Lamine Sall, de Fama Diagne Sène, de Mbougar Sarr pour ne citer que ces différentes…

0 notes

Text

Tabata Ndiaye in Ceddo (Ousmane Sembene, 1977)

Cast: Tabata Ndiaye, Alioune Fall, Moustapha Yade, Mamadou N’diaye Diagne, Ousmane Camara, Nar Sene, Makhouredia Gueye, Mamadou Dioum, Oumar Guèye, Pierre Orma, Eloi Coly, Marek Tollik, Ismaila Diagne. Screenplay: Ousmane Sembene. Cinematography: Georges Caristan, Bara Diokhane, Orlando Lopez, Seydina D. Saye. Art direction: Alpha W. Diallo. Film editing: Dominique Blain, Florence Eymon. Music: Manu Dibango.

In Wolof, ceddo means something like "outsiders" or "others," but the subtitles for Ousmane Sembene's film translate it as "pagan." Which is appropriate in that Sembene's film is about that essential precursor to colonialism: the obliteration of an indigenous religion by a proselytizing religious authority. Ceddo is set in a village in Sub-Saharan Africa in precolonial times -- Sembene said that he imagined it to be the 17th or 18th century. The colony of French West Africa was established in 1895, but the colonizing vanguard was there much earlier in the form of Islamic and Christian missionaries. In Ceddo the village has been mostly converted to Islam, which the village king has accepted. But the ceddo resist the new religion, and kidnap the king's daughter, Dior Yacine (Tabata Ndiaye), who is supposed to marry a Muslim, in conflict with suitors upholding tribal tradition. The struggle to return the princess is bloody. Two white men, a slaver and a Catholic priest, observe the action like eager scavengers. Sembene tells the story with a mixture of straightforward narrative and touches that evoke the future under colonialism. The music track, for example, at one point contains a gospel song sung in English, suggesting the diaspora of slavery. And we see the Catholic priest with what appears to be his sole parishioner in his makeshift chapel, but Sembene cuts to a vision of what the priest longs for: a large congregation with nuns dressed in white and an image of black men rising into heaven. At one point, when the Islamic villagers have won a victory over the ceddo, the imam gives the forced converts their new names. The first one is called Ibrahim, but the second is tellingly given the name Ousmane. Ceddo is an ambitious film, made under difficult circumstances -- the dailies, for example, had to be sent to France to be processed, resulting in a lag of some weeks before Sembene and his crew could know if what they had shot was acceptable. But Sembene's achievement is a remarkable portrait of a continent in transition.

1 note

·

View note

Text

MAMADOU

www.beau-gar.tumblr.com

#mamadou diagne#raf simons#summer 2022#black models#black man#handsome#numeroberlin#menswear#fashion#blackmalemodel#menswearblogger#menswearfashion#mensfashionblog#fashion blog#male model#fashionblogger#mensfashion#mensweardesigner#fashiondesigner#men's fashion#mens style#street style#style#style blogger#parisian style#styleoftheday#style inspiration

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

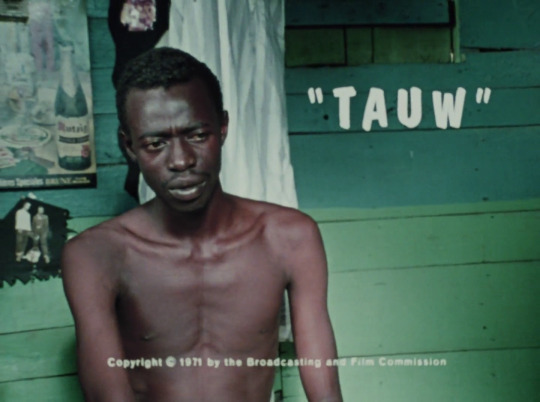

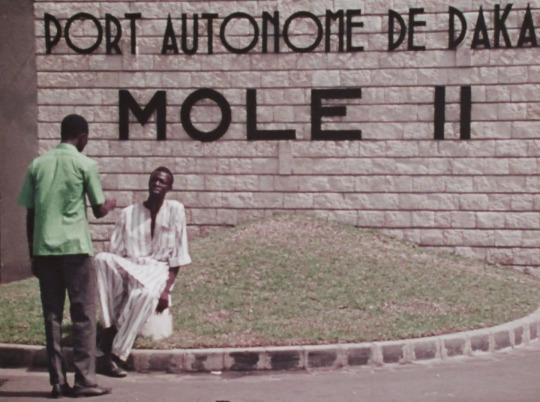

Tauw (1970)

Director - Ousmane Sembène, Cinematography - Georges Caristan

"Today has brought me nothing, nothing but a big zero. What can tomorrow possibly bring me? Prison for stealing? A Penal Camp for delinquency or a Mental Hospital because I can't face life anymore? That's what tomorrow will bring to all of us who can't find work."

#scenesandscreens#Ousmane Sembène#tauw#Georges Caristan#Senegal#Mamadou M'Bow#Amadi Dieng#Fatim Diagne#Coumba Mane#Habib Diop#Papa Yoro#mamadou diagne#Ibrahima Boye

274 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mamadou Diagne by Fujiro Emura for How to Wear It Magazine April 2023

211 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Mamadou Diagne at Baldessarini, Fall 2022 Menswear

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

mamadou diagne for louis vuitton f/w 2021

28 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Mamadou Diagne

Portfolio

1 note

·

View note