#louis-gabriel suchet

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

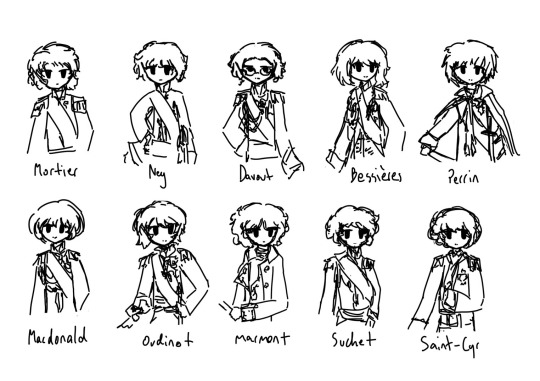

I drew all 26 of Napoleon's marshals

#napoleonic wars#napoleon’s marshals#do i just tag all of them#Louis-Alexandre Berthier#Joachim Murat#Bon-Adrien Jeannot de Moncey#Jean-Baptiste Jourdan#André Masséna#Pierre Augereau#Jean-Baptiste Bernadotte#Guillaume Brune#Jean-de-Dieu Soult#Jean Lannes#Édouard Mortier#Michel Ney#Louis-Nicolas Davout#Jean-Baptiste Bessières#Claude Victor-Perrin#Jacques MacDonald#Nicolas Charles Oudinot#Auguste de Marmont#Louis-Gabriel Suchet#Laurent de Gouvion Saint-Cyr#Józef Antoni Poniatowski#Emmanuel de Grouchy#François Christophe de Kellermann#François Joseph Lefebvre#Catherine-Dominique de Pérignon#Jean-Mathieu-Philibert Sérurier

63 notes

·

View notes

Text

Suchet✨

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Back from the uni entrance exam w/ some ddls😋

Yapped a lot so I'm putting alt on each of them😲

#napoleonic wars#napoleonic era#louis gabriel suchet#jean baptiste bernadotte#louis nicholas davout#geraud duroc#jean lannes#mortisoult#jean de dieu soult#laurent de gouvion saint cyr#louis charles antoine desaix#jean andoche junot#joachim murat#andre massena#jean baptiste bessières#dominique jean larrey#napoleon bonaparte#dotdotdot

183 notes

·

View notes

Text

Last set :D

#napoleonic era#napoleon bonaparte#my art#french history#napoleonic wars#napoleon's marshals#auguste de marmont#nicolas oudinot#louis gabriel suchet#laurent de gouvion saint cyr#jozef poniatowski#emmanuel de grouchy#senior project madness

83 notes

·

View notes

Text

The ends of the Marshals

We know a lot about our marshals of empires, but for some their existence ends in 1814, I did some research and I did all the dates of death of the 26 marshals of the empire with their age of death and some information that I had, do not hesitate to say other information if you have any, when we look closely Lannes was the first to die and at a young age while the one who spent the most time on earth is Moncey who lived until 87 years old, yet it is Marmont who will be the last to die in 1852, I hope that this will be useful for some.

Shot:

-Murat, October 13, 1815 (trying to recover his former kingdom of Naples …) at 48 years old

-Ney, December 7, 1815 (judged as a traitor for having joined Napoleon in 1815) at 46 years old

Defenestrate: (throw at a window)

-Berthier, June 1, 1815 (suicide or murder?) at age 61

Killed in combat:

-Lannes, May 31, 1809, wounded in the leg, dies of his wounds, at age 40

-Bessières, May 1, 1813, wounded by a cannon (no chance of survival) at age 44

-Poniatowski, October 19, 1813, drowned during the battle of Liepzig, at age 50

assassinated:

-Brune, August 2, 1815 (victim of the white terror of 1815) at age 52

-Mortier, July 28, 1835 (killed in an attack) at age 67

illness:

-Davout, June 1, 1823 (probably of tuberculosis) at age 53

-Augereau, June 12, 1816, at age 58

-Masséna, April 4, 1817 (long-term ill) at age 58

-Gouvion Saint-Cyr, March 17, 1830 (stroke) at age 65

natural causes, old age: (Here it is mainly deaths from natural causes)

-Perignon, December 25, 1818, at age 64

-Serurier, December 21, 1819, at age 77

-Lefebvre, September 4, 1820, at age 64

-Kellermann, September 14, 1820, at age 85

-Suchet, January 3, 1826, at age 55

-Jourdan, November 23, 1833, at age 71

-MacDonald, September 25, 1840, at age 74

-Victor, March 1, 1841, at age 76

-Moncey, April 20 1842, at age 87

-Bernadotte, March 8, 1844 (died of a paralytic attack at age 81)

-Grouchy, May 29, 1847, at age 80

-Oudinot, September 13, 1847, at age 80

-Soult, November 26, 1851, at age 82

-Marmont, March 2, 1852, at age 77

#history#napoleonic era#napoleon's marshals#michel ney#joachim murat#louis nicolas davout#louis alexandre berthier#jean mathieu philibert sérurier#jean lannes#jean baptiste bessières#jean baptiste jourdan#jean baptiste bernadotte#joseph antoine poniatowski#pierre augereau#claude victor perrin#jean de dieu soult#edouard mortier#nicolas charles oudinot#emmanuel grouchy#auguste de marmont#louis gabriel suchet#etienne macdonald#catherine dominique perignon#françois joseph lefebvre#françois christophe kellermann#jean mathieu philibert serurier#adrien moncey#andré masséna#laurent gouvion saint-cyr

115 notes

·

View notes

Text

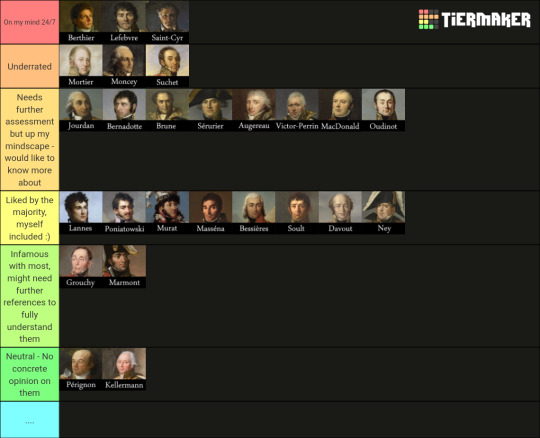

A tier-list of the marshals mainly based on how much I hyperfixate on them. Feel free to drop your own opinions on here :3

Tierlist can be found here!

#napoleons marshals#napoleon’s marshals#napoleonic wars#tagging all 26 hoo boy#louis alexandre berthier#françois joseph lefebvre#laurent de gouvion st cyr#louis gabriel suchet#edouard mortier#bon adrien jeannot de moncey#etienne macdonald#jean baptiste jourdan#claude victor perrin#jean mathieu philibert serurier#guillaume brune#charles pierre augereau#jean baptiste bernadotte#nicolas oudinot#jean lannes#joachim murat#andre massena#jean baptiste bessières#jozef poniatowski#jean de dieu soult#michel ney#louis nicolas davout#auguste de marmont#emmanuel de grouchy#françois christophe de kellermann#catherine dominique de perignon

35 notes

·

View notes

Note

A fun little ask: the Marshalate is informed there is cake in the break room. How do each of them react?

Who ever you are, thank you for this sweet little question and I apologise for my late response. 🙈💕

I have ideas for some of them, however I am **not** aware of the maréchals eating habits so any input is welcome here. Also, I don't know all of the marshals well enough but I will try to include as many as possible. Don’t expect any historical accuracy in this.

See this post as a very big headcanon and as one ongoing story where I am going to try to mimic the marshals characters and miserably fail.

Shall we begin? :D

Les Maréchals and cake

Berthier would hear about it and quietly get excited by the idea of having a nice little piece of cake, just for him to be too busy with everything so that he isn't able to leave his desk. Either this or someone (probably one of his adcs) would be nice enough to get for Berthier his piece of cake.

Murat: You bet he is one of the first ones to look at this cake. His reaction might depend on how the cake looks. If it's a huge cake with a lot of golden details, Murat will carry it around so everyone admires this phenomenal cake because it deserves to be looked at.

Augerau and Masséna wonder why there is such a fancy a cake in the break room in the first place and who might have put it there. Augerau asks Masséna with a low voice: “How much money do you want to bet on the cake being poisoned?” Before Masséna is able to answer, Lannes enters the scene.

Lannes runs after Murat with the cake knife demanding to finally get his damn piece of this cake while Murat can't make himself to cut it because this cake is “so damn beautiful that it would be a waste to eat it.” This little game goes on for a minute or two until the other marshals grow impatient, one of them being Ney.

Ney who is known for his hotheadedness tries to save this cake from a disaster aaaaand fails. :) The three of them dispute over who is the actual culprit of this mess.

L: Murat, what have you done? M: I have done nothing. You followed me with a knife. N: You let the cake fall. M: You intervened in my business with Lannes.

The cake has fallen to the ground as Davout, Suchet and Macdonald watched. “Aaand here goes the cake”, Macdonald says; “At least the floor was able to taste it.” Suchet asks: “What do you think was its flavour?” ”Chocolate vanilla.” Davout answers. After a moment of silence, he adds. “Soult has a good recipe.” Mortier walks in, seeing how Lannes, Murat and Ney are loudly disputing while Masséna and Augerau get themselves black coffee and Davout, Suchet and Macdonald talking. Lefebvre who was walking right behind Mortier gestures him to move away from the door so he can get into the break room: “What is going on?”

Suchet: “We found a cake-“ Davout interrupts him: “We found a chocolate vanilla cake which we don’t know how it got here or if it was poisoned and now it’s inedible because his royal highness, the King of Naples, made it fall.”

Murat shouts from the back: “I didn’t let it fall.” Lannes: “Oh, you did.”

Lefebvre offers a solution like the good fatherly figure he is: “Do you still want cake? We could bake a new cake, messieurs.” Davout replies: “This sounds like a smart idea, Monsieur. Maréchal Soult knows an excellent recipe.”

Lefebvre: “Ahh, excellent. Where is our maréchal?”

Mortier: “He is in his office.”

“Then this where our journey goes next.” Lefebvre slams the door open and accidentally hits Oudinot. “Ah, Monsieur, my apologies. If I had known you were there, I wouldn’t have slammed the door as hard as I did. Are you alright? Yes? Until the next time then.”

Davout walks up to his friend to make sure how Oudinot is doing and explains to him in the meanwhile what is going on and also promises Oudinot to bring him a piece of the cake they are going to bake.

Lefebvre takes the lead and walks straight to Soult’s office while Davout and Mortier follow him. Suchet decides to stay behind while Macdonald thinks about it. Lefebvre knocks on Soult’s office door: “Monsieur, le maréchal? Are you here?” *Lefebvre knocks again with his energetic manner.* “Monsieur, le maréchal, it’s me, Lefebvre. Open the door!*

Soult opens the door with his usual unimpressed demeaner: Hm? Lefebvre: “Excusez-moi, mon maréchal, I heard you have a recipe for a delicious cake?” Soult: Cake? What cake? Davout: The chocolate vanilla one… the one you baked for your daughter Hortense’s birthday. The delicious one. Soult: Ah, yeah. That one. What of it? Mortier: We would like to bake this cake, which is why we want to ask if you mind us borrowing the recipe? Soult stares at his co-maréchals for a second, he shuts the door, opens it again with a piece of paper in his hand which he gives to Lefebvre. “Here. Is there anything else you need?” Macdonald who decided to join the baking group walks up to them and asks Soult: “Would you mind to lend us your baking equipment?” - “No. Have a nice day.” Soult shuts his door while Lefebvre shouts: “Thank you for your help, Monsieur Soult.” Macdonald asks: “What are we going to do now?” “We are going to bake the cake now, my good friend”, Davout answers. Mac: “Where? Where do you want us to bake the cake? Do we have the right ingredients?” D: In the kitchen and I don’t see why we shouldn’t have the ingredients. Macdonald looks at Davout with suspicious eyes about the matter if they are going to manage to bake this cake… The group of maréchals appear in the imperial kitchen where they start to gather the right ingredients. While the group is busy with the preparations, les maréchals Pérignon and Sérurier appear, wondering what is going on. As Lefebvre is explaining these two their baking journey up until now, Pérignon and Sérurier decide to join them: “A cake made by maréchals for maréchals.”

What could possibly go wrong with two additional heads in the kitchen? As it turns out: Everything. Pérignon and Sérurier manage to overdo the cake by confusing salt with sugar. The cake tastes salty, the icing itself is fine because it was made by Davout who religiously followed Soult’s directions. In addition to that, monsieur Lefebvre manages to mix up usual paper with baking sheets.

Bernadotte walks into the kitchen as he sees his fellow maréchals working on their baking project. He comments on the scenery: “This is just pure chaos without any discipline, a chaos which can’t possibly create something edible.” Davout replies “Well, have you ever baked anything in your miserable existence which you so call your life?”; to which Bernadotte says: “wELL, no, BUT-“ Davout continues: “Then get out of this room and give me my peace back or shut up.” Bernadotte decides to leave.

As Bernadotte is leaving, Jourdan walks right into the scene with an apple in his hand. A fire starts to break out in the oven and Jourdan, like the team player he is, turns and leaves this mess to his co-maréchals without saying one word.

Nothing is going as Davout had it planned. He sits in a corner, mourning this beautiful chocolate vanilla cake he had in mind. Macdonald sits right next to him with a spoon, telling him: “Well, at least the frosting you made yourself is delicious.” Davout, completely shattered by the fact that he wasn’t able to make his desired chocolate vanilla cake, puts his face into his palms until a surprise visits the kitchen: It’s maréchal Soult. With a cake. A chocolate vanilla cake. A chocolate vanilla cake which is neither burnt nor oversalted. A chocolate vanilla cake according to the recipe. Next to Soult is Oudinot who cuts two pieces of the cake: one for himself and one for his good old friend, Louis Nicolas Davout.

After Soult, Ney and Lannes enter the kitchen. Ney silently takes a piece of Soult’s cake, saying nothing except a simple “thank you”. So do Macdonald and Mortier. Soult tolerates Ney’s presence. Lannes on the other hand goes straight to the oversalted and burnt cake which the older maréchals made and are also eating. Kellermann and Grouchy, as late to the party as ever, also go for Lefebvre’s bad cake while Soult’s good cake is still sitting there. Soult can’t hide his look of disgust.

At some point, Bessières and Murat join or rejoin retrospectively the scene, walking up to Soult’s cake. Bessières, as well mannered as he is, takes one piece of a cake to which Murat comments: “I know how much you like this lovely type of cake, Bessières, take a second piece.” - “No”, Soult replies: “That’s not your cake. Take your piece and leave.” Murat adds: “For whom are the other pieces then? I don’t see anybody who would possibly want to eat this gorgeous baked good. We want to eat your delicious creation of a fabulous cake.” - “One piece each. You can give him your piece if you like to.” Bessières interrupts the two: “I am content with my piece.” Murat doesn’t listen to what Bessières says and continues his conversation with Soult: “My fellow maréchal, I don’t understand, why do you struggle so much with allowing somebody to have one additional piece of cake than the other ones?”

While Murat and Soult continue their dispute which leads to nowhere, one adc enters slowly the kitchen. He looks at Soult who recognises this man as one of Berthier’s adcs. He came to get a piece of cake for his marshal. Soult lets him take one of the few pieces left. All of a sudden, Kellermann seems to be chocking on his salty cake piece. All the maréchals are gathering around him and in the chaos, the last few pieces of Soult’s cake fall to the ground. Soult looks at his cake or what’s left of it. One could argue that everyone who wanted to eat it was able to eat it. One could argue that these fallen pieces can be ignored and Soult could go on with his day never ever thinking about the pieces again. However, we are talking about maréchal Soult here who sees the art in baking. The love, the accuracy of it. Today he didn’t just bring cake to his fellow maréchals. Today he witnessed how some of them have no sense of dignity for what it means to be able to eat good food. Good cake. Soult is leaving the room, not bothered about Kellermann as he wouldn’t be able to help anyway. He is going to his wife, his Louise Berg, who asks him about his day. He tells her the whole of it. How he was surprised by his fellow maréchals who wanted to bake a cake. How he knew that they are going to mess up his recipe. How he baked that cake properly and how a part of it went to waste. “Some of them ate oversalted and burnt cake. Who eats bad cake? Who likes bad cake???”

Davout on the other hand was thankful for Soult. With a smile on his face, Davout enjoyed his so desired chocolate vanilla cake, unbothered by the event surrounding him. The end. :)

#Napoleonic headcanon#headcanon#napoleonic#louis alexander berthier#joachim murat#charles pierre augerau#andré masséna#jean lannes#michel ney#louis nicolas davout#louis gabriel suchet#étienne macdonald#édouard mortier#nicolas charles oudinot#françois joseph lefebvre#jean baptiste bernadotte#jean baptiste bessières#jean baptiste jourdan#jean de dieu soult#louise berg soult#And the rest :)#i am too tired for this#i hope you like it#cake

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

It's double

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Suchet and Soult, 1813

That Napoleon’s marshals in Spain most of the time were busy being at odds with each other is well-known. Marshals Soult and Suchet were no exception. Suchet in particular seems to have rather disliked Soult, if it is true that as early as 1805 he specifically wanted to leave Soult’s army corps and had himself be transferred to Lannes’ instead. Their relations probably did not get much better in Spain, considering the animosity between Joseph and Soult, and Suchet’s close family relations with Joseph.

Suchet seems to have had a bit of a reputation for being the jealous kind. In any case, if this scene from 1813 is to be believed, he was not ready to be under the command of Soult under any circumstances, not even for the sake of France. It’s from the "Mémoires anecdotiques" by general Armand Alexandre Hippolyte Marquis de Bonneval, whose author had become Soult’s aide de camp quite against his will, but apparently, by the time they reached Spain, despite himself was already fully included in his military family.

Context: After an insuccessful attempt to save Pamplona, Soult, rather belatedly charged by Napoleon to take full command in Spain in summer 1813, when Joseph had lost the battle of Vitoria, wanted to unite what was left of Joseph’s forces with those still under the command of Marshal Suchet, in order to defend France’s borders from Wellington’s approaching army. He thus needed to contact Suchet in Catalonia. Bonneval writes:

I was entrusted with this mission and went via Perpignan to Barcelona, where Marshall Suchet was. He listened to me with complacency; then, after having discussed at length the arrangements to be made to effect this junction, he declared it necessary to make a movement in the direction of Valencia to sweep away the Spanish armies and thus ensure the safety of the portion of his army he would leave in Catalonia. So we set off, and having achieved the goal Marshal Suchet had in mind, we returned to Barcelona.

And it was on the journey back that Soult’s idea was discussed once more.

While riding side by side with me, Marshal Suchet asked me: "What will my position be with regard to Marshal Soult, Monsieur de Bonneval?" - "But," I replied, "Monsieur le maréchal, it can only be, in any case, that of a marshal of the Empire; however, if Your Excellency asks me if Marshal Soult will be willing to give up his position of seniority and lieutenant of the Emperor, my mission does not go as far as that." The marshal turned very cold and stopped talking to me.

As a matter of fact, according to Bonneval, Suchet at this point had decided that Soult’s plan was "untimely and inconvenient". Bonneval tried to talk him out of that, but in vain.

He persisted; and I saw that there was nothing to do but to take leave of him and return to Marshal Soult. On arriving at Saint-Jean de Luz, at about 2 o'clock in the morning, I found my comrades at table over champagne and oysters. They all stood up and invited me to join in the feast.

Because apparently, even without the original line-up of Saint-Chamans, Lameth, Soult’s brother Pierre etc., the tradition of all-night parties was still kept alive.

"I shall return to you shortly," I told them, "but first I must go and make the Marshal swallow the biggest of all oysters." When I arrived at his place, Marshal Soult was awake; in fact, he never slept with more than one eye closed. "Ah! it's you, my dear Bonneval," he said to me. "Is Marshal Suchet on his way?"- "He is still in Barcelona, Monsieur le Maréchal, certainly sleeping better than you." And I gave him all the details of my failure. He then burst into a holy rage against the foolish pride and ineptitude of the Duke of Albufera, throwing his cap at the ceiling and hurling the foulest words in his vocabulary. Then, calmer again: "Go and rest, my dear friend," he said. I went straight to the oysters and champagne.

That last sentence is just 😂. Obviously, everybody had their priorities straight.

Interestingly enough, Bonneval later, like Saint-Chamans, would become a staunch royalist and have a fall-out with Soult for political reasons. Yet he apparently always held Soult in high esteem personally, and claims to always have hoped Soult would "see reason" and "return to the path of honour", i.e., to the cause of the older branch of Bourbons.

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy birthday Suchet! (March 2)

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Real suchet appreciation 💥🔥Was gonna make a post about him(maybe I'll do it)

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Old doodle☀️

#doodle#napoleon bonaparte#Louis Antoine Fauvelet de Bourrienne#maximilien de robespierre#gebhard leberecht von blucher#alexander i of russia#horatio nelson#louis gabriel suchet#josephine de beauharnais#friedrich wilhelm iii#luise von mecklenburg strelitz#lord castlereagh

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

I don't understand how people go to Père Lachaise and not even look at their grave... No need to know them, just admire their tomb, which is just magnificent.

Well ok Murat's is a bit disappointing... But the others... They are BEAUTIFUL!

Just need to wash them a bit and it's just perfect

(Photo taken by me)

#history#napoleonic era#napoleon's marshals#michel ney#joachim murat#francois joseph Lefebvre#andre massena#louis nicolas davout#louis gabriel suchet#laurent gouvion saint cyr#french history

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

The lack of memes for Suchet is criminal. I am aware that its his birthday, but the content for this man is close to being non-existent in amount. I NEED TO KNOW MORE ABOUT HIM

#rambles#louis gabriel suchet#napoleon's marshals#napoleonic wars#napoleons marshals#next to saint cyr he's within my top five#sighing

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

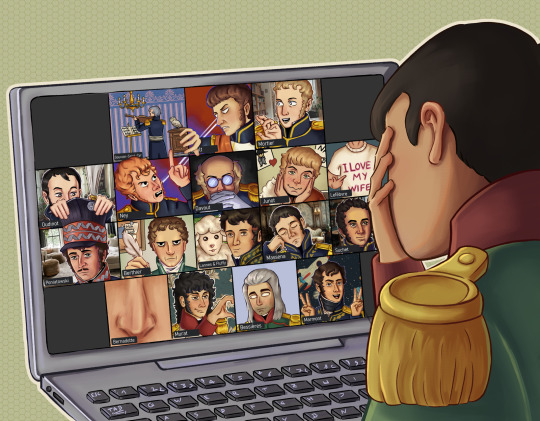

I REALLY LOVE THIS

The next time you are dreading a teams call with your co-workers, just be glad you don't have to put up with these dudes. I legit forgot Junot wasn't a marshal. Just imagine Napoleon hasn't found a way to perma ban him yet.

#SAINT-CYR IGNORING THE MEETING AND PLAYING WITH HIS VIOLIN INSTEAD 😍😍#OUDINOT AND PEPI ARE CUTIES FOR REAL.#AND I SEE SUCHET OOOOOOO🤩🤩🤩#Junot stop staring at Naps you already have two wives#michel ney#louis nicolas davout#auguste de marmont#jean andoche junot#laurent de gouvion saint cyr#louis gabriel suchet#józef poniatowski#nicolas oudinot#BERTHIER WHY DO YOU LOOK SO TIRED😇#louis alexandre berthier#yes Lefebvre thank you for loving your wife♡#françois joseph lefebvre#Masséna are you sleeping#BERNADOTTE YOUR NOSE IS TOO BIG.#andre massena#jean baptiste bernadotte#jean baptiste bessières#joachim murat#jean lannes#napoleon bonaparte#ooh Lannes and Fluffy :3#Ney and Soult stop fighting pls#Mortier what are you doing i'm curious#napoleonic era#napoleon's marshals#lovelyy :3

347 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Napoleonic Marshals’ MBTIs according to Internet

(most of them are probably wrong but I'm 100% sure about my fellow INTJs, especially Soult)

(missing because of lack of information : Brune, Grouchy, Jourdan, Kellerman, Macdonald, Moncey, Pérignon, Sérurier, Perrin)

Pierre Augereau : ESTP Jean-Baptiste Bernadotte/Charles XIV : ENFJ Alexandre Berthier : ISTJ Jean-Baptiste Bessières : ISTJ Laurent Gouvion Saint-Cyr : INTP Louis-Nicolas Davout : INTJ Jean Lannes : ESTP François-Joseph Lefebvre : ENTJ Auguste de Marmont : ENTP André Masséna : ENTP Adolphe Mortier : ISTP Joachim Murat : ESTP Michel Ney : ESTP Nicolas-Charles Oudinot : ESTJ Joseph-Antoine Poniatowski : ISTP Jean-de-Dieu Soult : INTJ Louis-Gabriel Suchet : ENTJ

46 notes

·

View notes