#long live our polyglot icon

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

I just think that we as Emily writers should make a pact to include more Emily speaking foreign languages in our fics <3 no pressure tho <3

#it’s soooo overlooked#admittedly even in my own stuff#so let’s include it more!!#long live our polyglot icon#emily prentiss#emily prentiss x reader#emily prentiss fanfic#rambles

93 notes

·

View notes

Text

2.2 Toledo Day Trip

Toledo is a shining example of not only the multifaceted culture and history of Spain but also coexistence. The origins of the city of Toledo start in II century B.C., at which time it would have been known as Toletum, a word deriving from Latin meaning “high place.” Being that this city was founded by the Romans over 2200 years ago, protection from outsiders was high priority. Luckily el río Tajo, or the Tagus river, gave natural protection to the eastern, southern and western borders of the city, which meant a fortress was only necessary for the northern side of the city. The source of the river is found 255 km (158 mi) east of Toledo called Fuente García and in total runs 1,007 km (626 mi) to Lisbon, Portugal where it empties into the Atlantic Ocean. This makes it the longest river in all the Iberian Peninsula and is used for hydro-electric power and commerce. The Tagus River would eventually be the downfall of Toledo for a few centuries but I’ll get to that later. The city layout of Toledo is a labyrinth, much like that of Segovia, and was specifically intended to confuse outsiders as to make invasion a near impossible task. In addition to being designed to confuse, it was also designed to provide protection from the sun, so finding shade throughout the city is a piece of cake— great for me because I burn too easily.

From roughly the IV century until the VIII century Toledo was the capital of the entire Iberian Peninsula, which was ruled by the Romans until the Moors took rule in 711. When the city was in Islamic control the name changed from Toletum to طليطلة (tulaytila) and the Iberian Peninsula was referred to as الأندلس (Al-andalus), which is where the name Andaluz derrives from. The moorish reign lasted from the VIII century up until 1085 when King Alfonso VI reconquered the city from the Moors. Surprisingly, Alfonso VI was very level headed and did not reclaim the city by means of war, rather through the signing of agreements. This allowed for the Jews, Christians and Muslims to live in harmony with one another in a time known as the Golden Era. This is why the Spanish refer to Toledo as the city of three cultures/the city of tolerance. Our class readings clued us in on how the Arabic script we found adorned in the synagogues and cathedrals was an example of this cultural tolerance and the melting pot Toledo once was. The Mudéjar architecture that we saw on the ceilings of Santa Iglesia Catedral Primada de Toledo (Primate Cathedral of Saint Mary of Toledo) and La Sinagoga del Tránsito (the Synagogue of Transit) were adored by both Christians and Jews. Much like people are starting to do with tattoos nowadays, the Arabic script was often times used as decoration rather than for meaning.

Sadly the Golden Era didn’t last forever; the year 1492 marked the end of the age of religious and cultural tolerance when Granada— the last Moorish stronghold in the south of Spain— fell into Spanish rule. The Jews and Muslims living in Toledo were forced to either convert to Catholicism or flee. Our tour guide told us that some of the Jews that fled the city had kept the key to their house and passed it down through the generations, in hopes that one day they may return to what they knew as home. Because the Jews were some of the first people to inhabit the land, the city of Toledo has recently tried to make amends by granting them Spanish citizenship if they can prove their ancestry and pass a citizenship test.

Because Toledo only has an area of 5 sq. km (roughly 2 sq. mi) King Felipe II decided move the capital to Madrid in 1561 because the city couldn’t expand any further due to its river and wall. This caused the city to be abandoned as all the royals, nobles and anyone with money living in Toledo at the time went to live in Madrid. Without the city having been abandoned, it is likely that Toledo wouldn’t be as well preserved as it is today, so in a way while its geography kept and drove people out, it in return ensured its longevity. Even today there are measures taken to ensure the preservation of this millennia-old city, such as being a UNSECO protected site. Nowadays people moving out of Toledo is no longer a problem as the population has been steadily rising, nearly quadrupling in the past century reaching roughly 85,000 inhabitants.

Beyond the religious and architectural history, Toledo is also home to two of Spain’s biggest icons: Domenikos “El Greco” Theotokopoulos and Don Quijote de la Mancha. Don Quijote is the protagonist in the most infamous Spanish book with the same title as his name. Quijote is known as the first nobleman. Outside of one of the religious centers we went to, there was a polyglot reciting passages from Don Quijote in Spanish, English, French, Italian and Catalan to whomever would listen along the Route of Don Quijote. El Greco on the other hand is the only XVI century painter that has the privilege of being relevant in today’s culture. Although Greek by birth, he is considered Spanish by Spaniards themselves as he spent the majority of his life in Spain. We had the privilege of seeing one of his masterpieces in Iglesia de Santo Tomé called El enterramiento del conde de Orgaz, or The Burial of Count Orgaz. The story behind the painting is that two saints miraculously came down to heaven to bury Count Orgaz himself after living such a pure and honorable life.

It was certainly a long and overwhelming day with more than enough information to process. Toledo really gave me a look into the history of Spain and I could definitely see myself going back when I return to Spain sometime in the future.

1 note

·

View note

Text

1930s Mexico and Sergei Eisenstein’s Unfinished Mexican Film

In 1930, Russian avant-garde film director Sergei Eisenstein traveled to Mexico to start a film project known as ¡Que viva México! — but production was eventually abandoned and the film was never finished.

Upon Charlie Chaplin’s recommendation, Sergei Eisenstein connected with writer Upton Sinclair, who helped fund the project. Eisenstein shot dozens of hours of footage for what was planned to be a multi-chapter film about the history of Mexico. Funds from the Mexican Film Trust — a production company established by Sinclair, his wife, and other investors — were soon exhausted, and Eisenstein’s chances of finishing the film himself further diminished as his re-entry visa to the United States expired and he was unable to secure an extension to his permission to remain away from the Soviet Union. Much of the footage was brought back to the U.S. by the producers, and Eisenstein’s film remained incomplete.

***

Sergei Eisenstein compared Mexico and his 'Mexican picture' to a serape, the indigenous multi-coloured woven blanket:

So striped and violently contrasting are the cultures in Mexico running next to each other and at the same time being centuries away. No plot, no whole story could run through this serape without being false, artificial. And we took the contrasting independent adjacence of its violent colors as the motif for constructing our film: six episodes ... held together by the unity of the weave — a rhythmic and musical construction and an unrolling of the Mexican spirit.

Eisenstein’s Mexican film does not exist; we have only its yarn to be weft, many miles of film that Eisenstein could not access. He couldn’t take it with him back to the USSR since he had signed his rights away to Upton Sinclair’s wife, who had presented him with a contract that he — eager to leave Hollywood for Mexico — signed in Pasadena on November 24, 1930:

WHEREAS, Eisenstein wishes to go to Mexico and direct the making of a picture tentatively entitled Mexican picture, and whereas Mrs. Sinclair wishes to finance the production of and own said picture […] In consideration of the above agreement by Eisenstein, and in full faith that he will carry out his promise to direct the making of the best picture in Mexico of which he as an artist is capable, Mary Craig Sinclair agrees that she will put up the sum of not less than Twenty-five Thousand dollars ($25,000) […]

Mexico in the Early 1930s

The multi-ethnic Mexico of 1930–32 was archaic and innovative, welded in the buzz of post-revolutionary society and culture where artists such as Frida Kahlo, Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, and David Alfaro Siqueiros lived and worked. Later they were joined by sculptor Isamu Noguchi, photographers Paul Strand and Henri Cartier-Bresson, and several European surrealists. It was in Mexico City where André Breton and Diego Rivera met with Soviet exile Trotsky to write a manifesto on revolutionary art. However, in 1940 Trotsky was attacked and murdered in Coyoacán, only a few houses away from Rivera and Kahlo’s home. The fact that his assassination was supported by Stalinist artist Siqueiros marked the end of the era of innocence even before Mexico entered the war.

It was Siqueiros who a decade earlier had collaborated with Eisenstein in Taxco where the painter 'extended Eisenstein's montage principles to mural painting'. Mexico has an exceptionally strong tradition of muralism, used in the 20th century to communicate through images with people who could not read. This is not only parallel to Russian visual culture, which relied on icons, posters, and cheap woodcuts or prints, but also film as a medium of propaganda.

While Eisenstein was disappointed by Hollywood, he fell in love with Mexico. It was a country that at the time showed parallels to the USSR, which he had left in 1929. The Soviet film director arrived in the creative post-Revolutionary era, when not only Mexico’s indigenous roots had been revealed but a new, hybrid culture was emerging. This hybridity found its expression in Mexico as meeting place of cultures and diasporic communities, as polyglot as Eisenstein, who spoke several languages fluently. American progressive artists, who revered Diego Rivera, came to Mexico to join the Mexican Muralist Movement.

The American adventure seems to have cost Eisenstein his reputation at home and his health. Ordered to return to the USSR by Stalin, he spent time in 1933 in the Kislovodsk spa in the Northern Caucasus to recover from the depression following the film being aborted.

Versions and Reconstructions of Eisenstein’s Footage by Other Filmmakers

On his journey to Mexico, Eisenstein was accompanied by two people: his cinematographer Edward Tissé and his assistant Grigory Alexandrov. During my last visit to Russia, I asked a film professor from St. Petersburg why Eisenstein’s Mexican film was never finished, and received the answer that it was not only the Americans who were at fault, but also Eisenstein’s companion, Grigory Alexandrov, who might have informed the USSR that Sergei was not going home.

If this is true, it was indeed unfortunate that Alexandrov accompanied Eisenstein — not only because he seems to have accelerated his journey home, leading to the film never being finished, but also due to a competition that arose between the two in Hollywood. When Eisenstein in 1930 received the opportunity to make a film in Mexico with the help of Upton Sinclair, Alexandrov was not ready to leave since 'Hollywood producers had found Grigory Alexandrov a person whom they thought capable of producing the kind of pictures they wanted' — unlike Eisenstein, who was subjected to anti-Semitic attitudes, having been attacked in one letter 'as a 'Jewish Bolshevik' who the 'successful Jews of Paramount' had imported to make 'propaganda films''.

Alexandrov profited from the journey to America, having studied Hollywood sound stages. While Eisenstein back in the USSR could not make a film for nearly a decade, Alexandrov became one of the most proficient imitators of the Hollywood film musical, directing a string of successful comedies, advancing to Stalin’s favourite in this popular genre.

It was Alexandrov who, in the late 1970s, long after Eisenstein’s death, edited the best known version of the Mexico material, titled ¡Que viva México!. This is the version on which most of the critical literature about the Mexican material is based, such as the harsh critique of the film as producing 'gendered constructs' and 'fetish-objects' by scholars of Mexican cinema, Laura Podalsky and Joanne Hershfield. The criticism is accurate, at least when it comes to Alexandrov’s version of the Mexican material, with its 1970s Soviet soundtrack, exoticizing the material and turning it into a B musical.

There were other attempts at partial releases, versions, and (re)constructions, such as Sol Lesser’s 1934 shorts (Death Day, Thunder Over Mexico, and Eisenstein in Mexico, produced in the USA at the behest of the Sinclairs). Three other major versions of the material were prepared: Marie Seton edited the version Time in the Sun (1939, Anita Brenner, credited as Breener, was involved, as well) based on communications with the director, a four-hour version by film historian Jay Leyda incorporated all of the documentary footage shot on the side, and Oleg Kovalov created Mexican Fantasy in 1998.

What is there to be said about these many versions of Mexican material? They form an interesting corpus in themselves. This re-editing of the footage by multiple artists has added meaning and fresh context to the original work. We can look at this from the theoretical perspective of Prague structuralism which was shaped in the 1930s. It separates 'artefact' (the object itself) and 'aesthetic object' (the object that has been assigned value by the viewer). The idea is that only the aesthetic reception by someone besides the artist turns the object into a work of art. Re-editing or re-creating a film can be considered part of this act of aesthetic reception.

Films are not finished works of art. Even in films which are edited according to the will of director and/or producer, the editing is one of the components in film which stays changeable. In the early days of film, exhibitors freely recut foreign films — famously, Eisenstein learnt the craft of this type of montage from Esfir Shub. Politically motivated re-edits or excisions, in post-1945 USSR sometimes called 'reconstructions', all testify to film being not unchangeable and eternal, but rather a truly protean creature by definition, censored according to the current governing ideology or revived every time a new generation is ready to 'read' and edit it again. If that is the case, then Eisenstein’s Mexican cinema project is an ever-changing cinematic serape, one that enriches and perpetuates meaning via its unfinished — and yet continuing — condition.

0 notes

Text

Look Closer: Reexamining the Visual Primary Sources of San Francisco

I'm coming back to my home state of California to give a free book talk, open to the public, in the Skylight Gallery on the top (6th) floor of the Main Branch of the SF Public Library: Thurs. 8/23 from 6:30-8pm. It's right across from the Civic Center BART station. This event is co-sponsored by the San Francisco History Center, the SF Mechanics' Institute, and the CA Historical Society. I hope you can make it! Here is my blog post for the SFHC to accompany my talk:

Think about your office. Your home. Your phone. What do all three have in common? Aside from the fact that they are where Americans spend most of their time, I’m willing to bet that they are also all adorned with pictures that carry some import for you. Above all, those spaces—whether virtual or literal—are filled with pictures of your loved ones, and probably also yourself. The centrality of images in our daily lives has become the stuff of cliché—the ubiquitous advertising, the pop-up ads, the magazine stands by the grocery checkout counter. Pictures can carry real import, as evinced by the most frequently polled response to the question: what would you rescue if your house was burning down? As too many fire-ravaged Californians have demonstrated in recent weeks, the answer usually has to do with old photo albums and cherished family snapshots or portraits.

This state of affairs may be changing in the digital age, but that’s also interesting from a historical perspective. We may be among the last generations to have physical photograph albums—or at least printed albums that are irreplaceable, as opposed to being stored on photo websites or in the nebulous Cloud.

People nevertheless continue to adorn their walls with pictures of family and friends, not to mention ourselves. If you haven’t gotten around to scanning every old photograph, as I suspect most of us have failed to do, then those images become all the more irreplaceable and valuable.

This sense of pricelessness evokes elements of nostalgia and a deeply individualized sense of worth that is based on personal identity and family ties. Yet its value also yields tangible profit in our capitalist economy: in April 2012, Facebook bought Instagram for one billion dollars, evincing the power of images and their centrality to both companies’ platforms (it is, after all, called *Face*book).

How did this cultural fascination with images and identity begin? Some might argue that it evolved along with humans themselves. Berkeley historian Martin Jay has noted that sight became particularly important to homo erectus once we began standing on our hind legs. The sense of sight enabled us “to differentiate and assimilate most external stimuli in a way superior to the other four senses.” Smell, which is so vital to animals on all fours like dogs, was reduced in importance for humans during this fateful transition—indeed, Freud conjectured that this shift was “the very foundation of human civilization.” Vision was “the last of the human senses to develop fully,” and is still “the last of the senses to develop in the fetus.” The eye also possesses far more nerve endings and operates at a much greater speed than any other sense organ, and at the fastest rate of assimilation among the entire sensorium. For all this unparalleled speed, vision entails more than the simple recording and assimilation of sensory data; neurobiologists note that it requires considerable brain function to understand or interpret what we see. A disproportionate amount of the human brain is devoted to visual processing; research indicates that the neurons responsible for sight “number in the hundreds of millions and take up about 30 percent of the cortex, as compared with 8 percent for touch and just 3 percent for hearing.” Only within the last few generations have scholars in the humanities and social sciences begun grappling with the implications of such an influential and yet subjective framework for human experience and perception.

My first book, Consuming Identities, examines a particular chapter in this much larger story: the growth of a commodified image industry in nineteenth-century San Francisco, one of the most diverse and dynamic cities in the United States. I argue that visual images shaped the way that Americans presented themselves, portrayed and related to one another, and framed their world view; thus wielding considerable cultural power in nineteenth-century society. This cultural phenomenon was not simply a matter of perception but of practice and policy: it shaped popular ideas about race and identity, censorship and immigration laws, criminal justice policies, and entire industries such as the transatlantic market for celebrities and fiercely competitive photography and printing businesses in San Francisco, among many other cities around the world.

San Francisco was at the forefront of these changes, and it has gone largely overlooked as an epicenter of modern spectacle and visual culture—a culture that was only expanding in a rapidly urbanizing and diversifying country. The most popular genre within the visual medium was the portrait photograph, which played a pivotal role in mediating intimacy, facilitating new modes of identity formation, and creating a public culture of spectatorship amidst the capitalist crucible of the gold rush metropolis. Few places could more dramatically evince these characteristics than San Francisco, a place largely defined by its distance from every other non-indigenous point of origin for its tens of thousands of polyglot nineteenth-century inhabitants.

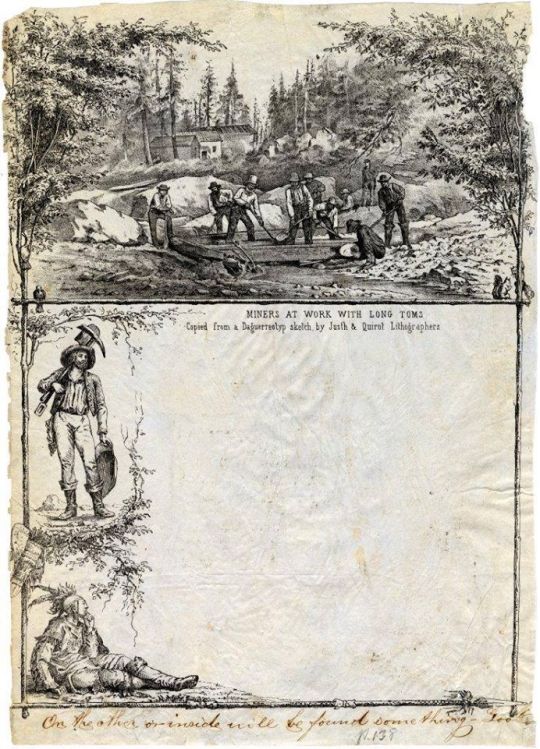

In my San Francisco Library talk, I will showcase examples from the seven thematically organized chapters of Consuming Identities—particularly those I uncovered at the San Francisco History Center and the California Historical Society, with some references to the importance of the Mechanics Institute in the cultural and professional dimensions of San Francisco history. For now, I want to focus on one of the many versions of roughly letter-sized illustrated gold rush stationery—known as letter sheets—that did not make it into my book: “Miners at Work with Long Toms.” This lithograph from San Francisco firm Justh & Quirot (active in San Francisco from 1851-53) was likely published by Cooke and Le Count, and dates to about 1851. It illustrates the posters advertising my upcoming book talk. (A lithograph is a design drawn and inked on stone, and printed with that stone—the technology was developed at the turn of the nineteenth century and proved much more efficient and durable than previous methods of wood or metal engraving.)

In the main image spanning the upper third of the sheet, ten miners work at unearthing their fortunes in a creek, using several iconic implements of the gold rush: shovels, long toms (expanded rockers, with troughs measuring 10-20 feet), and gold pans. Their cabins are visible in the distance, interspersed with the jagged rocks and the conifers of the Sierras. Beneath this vignette is an open space for the correspondent—usually a homesick miner—to pen his letter. The space is framed by two trees on the left and right margins, another long wooden span separating the upper illustration from the lower portion of the sheet (and adorned with serene naturalistic details like two birds perched on one end and a couple of squirrels on the other), and along the bottom there appears to be a Native American spear. Stacked vertically on the left-hand margin are two illustrations: an archetypal miner above an Indian, whose quiver of arrows and shield seem to be hung up above him on the leafy bough that demarcates the left margin. I will have more to say about these figures below, but first I want to contextualize this uniquely Californian version of a much larger visual genre.

Letter sheets communicated various perspectives, but they were usually informational, humorous, nostalgic, or moralizing. Several varieties of letter sheets were destroyed in a series of catastrophic San Francisco fires in the 1840s and 1850s and the devastating earthquake and fire of 1906, but scholars have estimated that between 340 and 750 varieties of sheets were produced—primarily by firms operating in San Francisco and a few smaller ones in Sacramento and the surrounding area. Eastern firms supplemented these sheets, often acquiring their artwork from associates in the Sierra foothills. But as lithograph collector and researcher Harry T. Peters noted in his book on the subject back in 1935, most eastern letter sheets differed in content, quality, and quantity from their western counterparts: few of them were mass produced, most were printed on low-quality paper, and tellingly, the overwhelming majority depicted serene views rather than caricatures, comics, or historic events. The California letter sheets, as “Miners at Work” exemplifies, evoked exceptional artistic quality, balanced representation of detail, and California artists strove for a distinctive linear perspective that created a three-dimensional effect. They centered on gold rush themes—particularly the archetypal miner—until the mid-to-late 1850s, long after the placer gold deposits had dried up around 1852-53. The sheets nonetheless continued to command a market for decades after the end of the Civil War, by documenting new themes that reflected public interest. German festivals and street scenes from Chinatown highlighted the diversity of the city’s inhabitants while providing viewers on both coasts and beyond with a rare glimpse at the exotic, the spectacular, and the unknown.

The contemporary popularity of these precursors-to-the-postcard is evinced by the fact that they were often pirated, or reproduced with subtle variations. U.C. Berkeley’s Bancroft Library has two other versions of this same letter sheet, with the same illustrations and title. One of those versions lacks the subtitle: “Copied from a Daguerreotyp [sic] sketch by Justh & Quirot Lithographers” (the other includes the subtitle but adds the address of the lithographers, at 28 Jackson St.). The daguerreotype was the first version of the photograph, simultaneously developed by a number of inventors in different countries, but formally introduced to the world in 1839 as the eponymous creation of Louis Jacques Mandé Daguerre. The fact that the term itself is missing the last “e” may have been a simple abbreviation of a widely known term by the gold rush era, or one of the chronic American misspellings of the French word. As I explain in Consuming Identities, this “from a daguerreotype” annotation was a commonly invoked claim, and whether accurate or not (too many original daguerreotypes have been lost to say with any certainty), publishers intended it to enhance the authenticity of their artist-rendered views for audiences wary of inaccurate depictions from the many artists who never actually ventured to California or the gold fields. In an age of false claims known as “humbug” and confidence schemes, daguerreotypes were widely considered beyond reproach as unaltered, frozen moments in time—though I also detail in my book the ambivalence that many nineteenth-century San Franciscans expressed about the extent to which photography could or could not convey deeper, underlying truths.

The main image of “Miners at Work” certainly looks as though it was copied from a daguerreotype: most of its figures appear to be looking directly at the viewer, who would have been in the same position as the photographer, and they are paused in their work. This conscious posing would have been necessary on the part of the photographic subject, because the longer exposure times of early photography did not allow for action shots without considerable blurring. In other words: nineteenth-century subjects knew that they had to hold still if they wanted the camera to capture them for posterity. Thus the man on the far left hunches over his shovel, his arms crossed above the handle, and six men at the center of the image appear to be posing with their shovels in a gesture of the digging that they performed with such frequency that their camps soon acquired the nickname of “diggings.” Two men are in seated or crouched positions, and the one in the right foreground appears to be the only one not looking towards the camera as he carefully studies his pan for gold deposits—or pretends to be doing that work, demonstrating the labor but also the implicitly performative dimensions of the miner archetype.

The miner was inherently performative, as contemporaries well knew and documented by referring to his—and their own—appearance as his (or their) “costume.” Historians like Brian Roberts have estimated that most of the young men who journeyed to California in the late 1840s and 50s were in fact part of the burgeoning middle class, as few proletarians could afford the steep fees for passage, let alone equipment and supplies, that such a long journey entailed. These self-dubbed “Argonauts” (in reference to the Greek legend of Jason and the Golden Fleece) were not necessarily accustomed to hard manual labor, and even those who did arduous work like farming would hardly have been as well prepared for mining as many of their experienced Chilean and Sonoran competitors in the gold fields. They nonetheless reveled in their chance to look and act the part of the phenomenon that the whole world was talking about—and viewing, in the form of the widely distributed illustrations on letter sheets and in a host of publications such as books and magazines, not only across the United States, but in Paris, London, Havana, and many other places.

The “Miners at Work” letter sheet illustrates the archetypal miner—along the left margin of the lower portion—and in its main image, a collection of men who evoke that archetype’s power in their attempts to look and act the part. They all don wrinkled shirts, pants, and several pairs of (doubtless mud-spattered) boots, just like the archetype. Most of them are wearing floppy hats, though one miner at the center of the upper image appears to have retained his top hat in a seemingly comic juxtaposition with his decidedly informal surroundings. At least two of them boast “whiskers,” as the long and unkempt facial hair was often dubbed in boastful letters back home, in which thousands of formerly clean-shaven and perhaps white-collar Americans reveled in their conformity to the decidedly racialized and masculinized miner archetype.

That the miner was racialized as an epitome of white masculinity is literally illustrated on this sheet, with the juxtaposition of the upper and lower figures on the left-hand margin. The Native American man is visibly and spatially separated from the identity and the work of gold rush mining. The difference isn’t just sartorial; he does not carry the iconic implements of the trade, such as the pickaxe, gold pan, or shovel of the miner standing above him. Instead, he reclines on the ground, apparently lost in a moment of contemplation, passive and even relegating his own tools—the arrows and shield—to a place hanging above his head on the tree trunk. There may be a tomahawk or club beside him, but his right hand has relinquished it on the ground. He seems resigned to literally sit out this internationally famous rush for riches, along with all the conquest, industrialization, and modernization (or “civilization”) that Americans proclaimed it would entail. A visual rendering of the then-popular “vanishing savage” myth, he could easily be interpreted as passively receding into the background, temporally and figuratively. He signifies the past, while the archetypal miner stands poised for action, his eyes focused on the horizon. Such seemingly naturalistic depictions masked the real violence and dispossession that lay behind the conquest, as historians of California Indians like Benjamin Madley have amply documented. There is no evident indication of this indigenous man’s tribe, if he was in fact based on a specific individual, but his moccasins, fringed shirt (likely of deerskin) and feather headdress may be reminiscent of the Maidu people of northern California. The larger point here is that most potential customers who purchased this sheet, or the viewers who received it, would not have known or much cared about the particular tribal affiliation and identity of this token representative of California’s indigenous population—a people who were associated with the region’s past.

Every letter that correspondents penned on the letter sheets was unique; yet every letter-sheet illustration was, by definition, mass-produced and identical to hundreds or thousands of others circulating throughout San Francisco and the postal system. Photographic technology did not allow for mass-reproducible portraits in the peak years of the gold rush, but advancements in steam printing and lithography (as detailed in the introduction to Consuming Identities) enabled artist-rendered illustrations to be created in very large numbers. The most popular gold rush letter sheets were printed in runs that stretched well into the tens of thousands, and may have approached one hundred thousand, according to some accounts. They were also extremely affordable, just like their counterparts in the East, and usually sold for mere cents per sheet (one California letter writer noted that he paid five cents for his, though they could easily be between ten and twenty cents). Engravers, printers, and stationers sold them individually or in bulk to resellers such as hotels, for anywhere from $10 to $15 per hundred in the mid-1850s. The genres of lithography and photography captured the period’s tension between uniqueness and homogeneity. For all the individuality that Argonauts expressed through their commissioned photographic portraits and their personal perspectives in letters, their appearances, experiences, and identities were bound up in the mass movement that was the gold rush. Neither of the Bancroft Library versions of this “Miners at Work” sheet contain any visible annotations, but the San Francisco History Center specimen does: along the bottom of the page, in the faded brown ink familiar to any historian of nineteenth-century manuscript correspondence, someone has written “On the other or inside will be found something—.” This tantalizing reference appears to beckon the reader to open up the letter sheet (they were often folded to allow more space for writing inside), or flip it over to the verso side. The Society of California Pioneers possesses an annotated version of this letter sheet, in which someone has penned a letter dated August 26, 1851 (though that dateline has been crossed out, whether by the correspondent or someone else, we don’t know).

Though historians have often utilized the handwritten correspondence of these letter sheets in their chronicles of gold rush life and culture, they have not paid sufficient attention to the distinctive visual medium that the California sheets represented. The correspondents themselves often reacted to the images printed on those pages, whether to reinforce their accuracy or undermine their message with contrary accounts. Some purposefully reserved their remarks for the verso side or for enclosed pages, so as to allow their recipients the chance to display the letter sheets as household decorations. Other purchasers may have adorned their makeshift cabins and tents with the sheets, just as they displayed the photographic portraits of their distant kin on their walls and at their bedside tables. Of all the myriad changes in daily life and culture between our own time and the gold rush, the ubiquity and talismanic power of human images remains as true as it ever was. Pictures still adorn our walls, and they still channel deep emotions. This history has something to tell us about where we came from and how our society came to be, but it also has plenty to teach us about ourselves.

Those interested in conducting their own close readings of these wonderful primary sources, and mining them for their rich details (pun intended), are welcome to do so by clicking on the hyperlinks to the different versions of the sheet provided below. We are all indebted to the hard work that went into scanning and digitizing high-resolution versions of these letter sheets, through fantastic archival websites like the Online Archive of California and Calisphere.

“Miners at Work with Long Toms” [c. 1851]. California Pictorial Lettersheet Collection, San Francisco History Center version: https://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8b85dww/

Bancroft Library version with subtitle and address:

https://calisphere.org/item/ark:/13030/tf2x0nb4s4/

Bancroft Library version without subtitle:

https://calisphere.org/item/ark:/13030/tf2g5007vp/

Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco version, courtesy of the Achenbach Foundation:

https://art.famsf.org/anonymous/miners-work-long-toms-3899740

#sfpl#san francisco#letter sheets#gold rush#native americans#california#history#americanhistory#visualculture#sfhc#chs#californiahistory#bancroft#miners#goldrush#sanfranciscopubliclibrary#mechanicsinstitute

0 notes