#lonesome (1928)

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

☆ Happy first day of autumn!!! ☆

I made some lonesome ghosts fanart to welcome the spooky season!

Alts! -

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

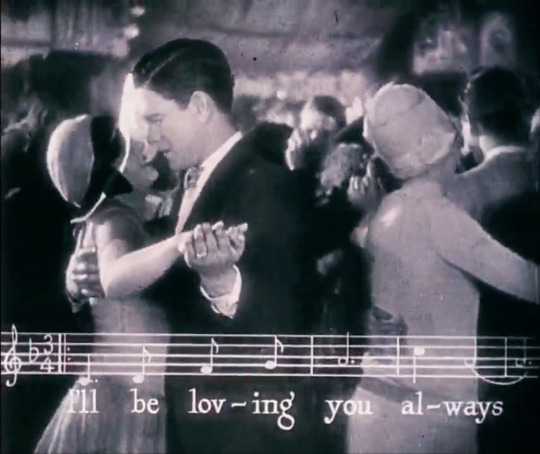

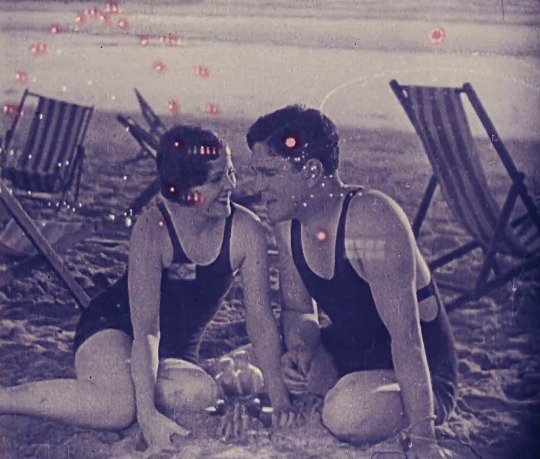

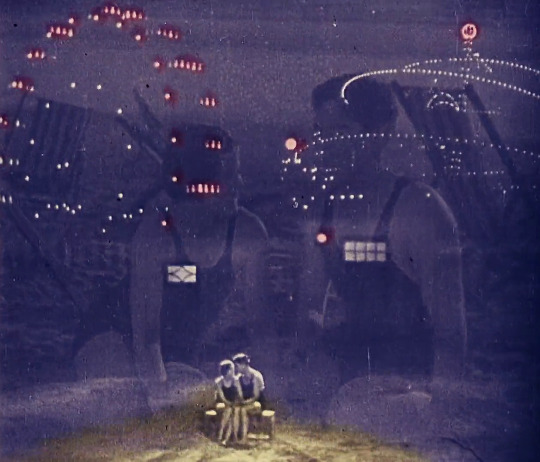

Lonesome (Pál Fejös, 1928).

#lonesome#lonesome (1928)#pál fejös#barbara kent#glenn tryon#gilbert warrenton#frank atkinson#charles d. hall

99 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lonesome (1928) Pál Fejős

January 13th 2024

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

TWST - NRC Dorm History and Founding Timeline

I'm sure someone else has talked about this before, but I haven't seen any posts about it and this is something that I was curious about since many of the personal stories in TWST reference Pomefiore as being "the oldest dorm on campus". So I did a little digging, and I think I've figured out the founding order of all the dorms and why they are in the order they're in.

The reasoning behind Pomefiore being The Oldest Dorm is actually a kinda simple reason: the Disney film Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs was released first out of all the other films that the dorms are originally twisted from. The film is actually the very first full-length animated film that was released and credited to Disney Animation Studios. This might be part of why Pomefiore's age seems to be focused on significantly, especially if the in-world timeline exaggerates its age to accommodate for the age of Night Raven as a whole.

Now this fact might not actually have any meaning as to how old the dorm itself is as far as in-world history, but at the very least with this in mind we can infer that the dorm creation order is as such:

Pomefiore (oldest): Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937)

Heartslabyul: Alice in Wonderland (1951)

Diasomnia: Sleeping Beauty (1959)

Octavinelle: The Little Mermaid (1989)

Scarabia: Aladdin (1992)

Savanaclaw: The Lion King (1994)

Ignihyde (youngest): Hercules (1997)

Additionally, this theory is supported by the room design of the Hall of Mirrors.

From left to right, each of the dorms' mirror portals appear in their exact order of when the real life films were released, with the exception of the few that are entirely out of frame.

Questions that are left unanswered by this observation still prevail though, the biggest one in my mind being: exactly how old are the dorms? Night Raven College's history allegedly goes back at least 500 years, so the question of Pomefiore's exact age is not actually answered given that context. It also seems strange for people to focus on its age so much if it would only be ~88 years old in comparison to Heartslabyul's ~74 (if we go based on their exact film release dates), and if Pomefiore is only that old, then logically speaking something would have to exist before it for Night Raven College to house students at all.

This also does not answer the question of what Ramshackle Dorm used to be (aside from just a dorm, obviously). I also have to beg the questions of why isn't Ramshackle held within its own pocket dimension like the other dorms? How old is the dorm? Why was it originally built? What did it used to be called before it was given the title of "Ramshackle"? Why it was left standing in the middle of campus despite its dilapidated state? And, most importantly, why does it inexplicably have a direct connection to a character that seemingly doesn't exist within the world of Twisted Wonderland (Mickey Mouse)?

The theory that the dorm could be based on the animated short Lonesome Ghosts (1937) is still a strong one due to the physical similarities between the settings of the short and the in-game dorm, but we don't have any other supporting evidence beside that due to the lack of canon historical information surrounding Ramshackle as a whole. I'm curious if this is the case, however, because while Lonesome Ghosts would make sense, it isn't the first animation from Disney's Animated Studios. Steamboat Willie (1928) is much older than Lonesome Ghosts, and even before then there were several short animations featuring Oswald Rabbit released under Disney's name. It seems odd that it would be based on a seemingly random animation from Disney's early years for no reason other than "visual similarities", but there's nothing else in canon to grasp onto other than that.

Clearly as of now the main story of Twisted Wonderland is by no means finished, even if we've finally made our way through the stories focused on all the dorms independently and the JP arc for Chapter 7 is officially over, I still feel strongly that the real story is only just beginning. Too many questions are still unanswered, too many knots are left untangled, and we still haven't wrapped around to the beginning battle that started it all. Hopefully some of these lingering questions will be answered once we reach them in due time.

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

Long hair to short hair to cloche: Lonesome (1928)

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lonesome : 1928 :: The 1928 film "Lonesome" is a silent drama directed by Pál Fejős. It tells the story of two lonely people who meet at an amusement park and share a day together, but then lose each other in the crowd. The film was originally released with a synchronized soundtrack and later re-released with three dialogue scenes, marking Universal's first feature-length talkie.

* * * *

“The invisible tissue of civilization: so thin, so easily rendable. It’s a miracle that it exists at all.”

— Lauren Groff, Arcadia

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

LÉGENDES DU JAZZ

TRUMMY YOUNG, DE JIMMIE LUNCEFORD À LOUIS ARMSTRONG

‘’But I never did deviate too much from my original style. But you incorporated certain things. Without changing the style. You don’t even know you’re doing it. If you play with a guy like Dizzy and a guy like Bird, you’re bound to pick up a few things automatically. You don’t realize you’re picking ’em up.’’

- Trummy Young

Né le 12 janvier 1912 à Savannah, en Georgie, James Osborne "Trummy" Young a grandi à Richmond, en Virginie, et à Washington, D.C. Fait à signaler, Young avait d’abord joué de la trompette et de la batterie durant son enfance même s’il avait amorcé sa carrière professionnelle comme tromboniste en 1928.

DÉBUTS DE CARRIÈRE

A l’âge de dix-huit ans, Young avait joué successivement avec les Hot Chocolates de Booker Coleman, des Hardy Brothers et des groupes d’Elmer Calloway et Tommy Myles. C’est dans le cadre de sa collaboration avec Myles que Young avait acquis son surnom de ‘’Trummy.’’ À l’automne 1933, l’arrangeur Jimmy Mundy avait quitté le groupe de Myles pour se joindre à l’orchestre d’Earl Hines et avait emmené Young avec lui. Au cours de son séjour de trois ans et demi dans le groupe de Hines, Young, qui était reconnu pour sa capacité de jouer de très hautes notes, avait augmenté la portée de son trombone et avait démontré énormément de puissance. Young avait participé à sept sessions d’enregistrement avec Hines, et s’était notamment illustré comme soliste sur les pièces “Take It Easy”, “Bubbling Over”, “Madhouse”, “Copenhagen” et “Cavernism.”

Young avait quitté le groupe de Hines en 1937 pour se joindre à l’orchestre de Jimmie Lunceford à New York. Devenu rapidement une des grandes vedettes du groupe, Young avait notamment interprété un solo impressionnant sur la pièce “Annie Laurie’’ lors de son premier enregistrement avec l’orchestre. Lors de la session suivante, datée du 6 janvier 1938, Young avait ajouté une autre corde à son arc en s’illustrant tant comme soliste que comme chanteur sur la chanson “Margie” qui avait remporté un grand succès. Le solo de Young, qui se terminait sur une des hautes notes dont il s’était fait une spécialité, avait été imité plus tard par de nombreux trombonistes. Même si la pièce “Margie” avait été composée en 1920 et avait été un grand succès tant pour le Original Dixieland Jazz Band (la pièce avait été co-écrite par le pianiste J. Russell Robinson et le parolier Con Conrad) que pour le chanteur Eddie Cantor, c’est la version de Young qui était demeurée la plus connue.

Young était resté une des grandes vedettes de l’orchestre durant son séjour de cinq ans avec Lunceford. En plus d’avoir interprété plusieurs solos avec l’orchestre, Young avait co-écrit avec l’arrangeur Sy Oliver les pièces “Tain’t What You Do It’s The Way That You Do It (It's the Way That You Do It)”, qui avait été un grand succès à la fois pour Lunceford et pour Ella Fitzgerald en 1939, et “Easy Does It.’’ Même si Young avait surtout été identifié comme tromboniste, il avait également chanté sur plusieurs enregistrements de Lunceford dont ‘’Cheatin’ On Me”, “The Lonesome Road”, “Ain’t She Sweet”, “I Want The Waiter With The Water”, “Whatcha Know, Joe” et “Easy Street.’’ Parallèlement à sa collaboration avec le groupe, Young avait aussi participé à une session avec Billie Holiday et Teddy Wilson comprenant le grand succès “Let’s Dream In The Moonlight.” En 1942, Young avait d’ailleurs co-écrit avec le saxophoniste et arrangeur Jimmy Mundy et le parolier Johnny Mercer la chanson “Trav’lin’ Light” qui était devenue par la suite un des grands succès de la chanteuse.

Young avait éventuellement quitté l’orchestre de Lunceford en 1943. À l’époque, le groupe traversait une période de déclin. Il faut dire que la réputation de Lunceford battait de l’aile, car il avait la réputation de ne pas toujours bien payer ses musiciens. À trente et un ans, Young avait donc décidé qu’il était temps d’aller voir ailleurs et de partir à son compte.

Même si Young était reconnu à l’époque comme un musicien de swing au style très mélodique, il était assez polyvalent pour pouvoir évoluer dans une grande variété de contextes. En plus de se produire comme leader, Young avait aussi été membre de l’orchestre de Charlie Barnet durant environ un an. Parmi les membres du groupe de Barnet, on retrouvait plusieurs futurs membres du célèbre First Herd de Woody Herman. Cité dans l’ouvrage Swing to Bop d’Ira Gitler publié en 1987, Young avait expliqué: “Barnett wouldn’t keep a band but so long. When the band got popular, he broke it because he said it was interfering with his pleasure.”

Young avait dirigé une première session comme leader le 7 février 1944. La même année, il avait également enregistré avec le batteur Cozy Cole (dans le cadre d’une session qui comprenait sa composition “Thru’ For The Night” enregistrée avec Coleman Hawkins et Earl Hines), le Billy Eckstine Orchestra, Una Mae Carlisle, Charlie Shavers et Don Byas (dans le cadre d’un V-Disc comprenant une version du classique “Rosetta”). Au cours de cette période, Young avait aussi été un collaborateur régulier de l’émission de radio de la chanteuse Mildred Bailey.

Même si Young avait très peu modifié son style au cours des années, il avait eu peu de difficultés à s’adapter au bebop. Young était d’ailleurs un assidu des clubs de la 52e rue. Grâce à son grand ami le batteur Kenny Clarke, Young avait été présenté à de grands noms du bebop comme Dizzy Gillespie et Thelonious Monk. Il avait aussi enregistré avec les Clyde Hart All-Stars (avec qui il avait chanté quatre chansons), qui comprenaient à l’époque Gillespie et Charlie Parker. Le 9 août 1945, Young avait fait une apparition avec Gillespie sur la version originale de la pièce “Salt Peanuts.’’ Durant la même session, Young avait également collaboré à l’enregistrement de la pièce ‘’Be-Bop’’, la version modernisée du standard “I Can’t Get Started’’ et du classique “Good Bait’’ de Tadd Dameron (qui avait travaillé comme arrangeur avec Lunceford). L’année 1945 avait d’ailleurs été très active pour Young, qui avait fait partie de l’orchestre de Boyd Raeburn avec Gillespie comme artiste invité (sur le classique ‘’A Night In Tunisia’’) et du big band de Benny Goodman. Il avait aussi enregistré avec les groupes de Georgie Auld, Johnny Bothwell, Al Killian et Roy Eldridge, tout en dirigeant sa propre session de swing. Évoquant sa collaboration avec Gillespie, Young avait commenté:

‘’The guys would say, “Let’s do something to trick these guys” So Dizzy had an apartment around on Seventh Avenue, and we all hung around there because Lorraine [Dizzy’s Wife] used to cook. And they started working on different chord progressions to keep these guys out of there. And they wouldn’t tell ’em what tune it was. It might be “I Got Rhythm,” but the chord progressions would be different. They did it to run these guys off there. And they used a lot of technique with it.’’

En 1946, Young avait poursuivi sur sa lancée en enregistrant avec le big band de Benny Carter, le clarinettiste Tony Scott, Buck Clayton, Illinois Jacquet, Tiny Grimes, Jimmie Lunceford (dans une session qui comprenait une nouvelle version du classique “Margie”) et Billy Kyle. Il avait également dirigé deux sessions comme leader. La même année, Young avait participé à la tournée de Jazz at the Philharmonic (JATP), tout en collaborant avec Billie Holiday, Lester Young, Buck Clayton, Coleman Hawkins et Buddy Rich. En 1947, Young avait fait une nouvelle tournée avec JATP tout en participant à des jam sessions avec les saxophonistes Dexter Gordon et Wardell Gray et le trompettiste Howard McGhee. Mais cette activité débordante était trompeuse: après avoir enregistré avec le big band de Gerald Wilson, Young n’avait pas enregistré durant une période de cinq ans.

En réalité, l’absence de Young des studios d’enregistrement n’était pas si mystérieuse. En 1947, Young avait épousé une femme originaire d’Hawaïï, où il n’avait d’ailleurs pas tardé à s’établir. Après avoir relancé sa carrière d’accompagnateur, Young avait formé un groupe de swing et de Dixieland à Honolulu.

Young était finalement revenu sur les feux de la rampe en septembre 1952 après avoir reçu une offre de se joindre aux Louis Armstrong All-Stars. Avec le groupe d’Armstrong, Young avait pris la relève de Jack Teagarden (qui avait été le tromboniste de la formation de 1947 à 1951) et de Russ Phillips (qui avait occupé les mêmes fonctions durant quelques mois).

Young s’était joint au groupe d’Armstrong juste à temps pour participer à une tournée en Scandinavie. La tournée avait remporté tellement de succès que Young était immédiatement devenu un élément essentiel du groupe, dont il avait fait partie durant une période de onze ans. Avec les All-Stars, Young avait joué aux côtés de grands noms du jazz comme les clarinettistes Bob McCracken, Barney Bigard, Edmond Hall, Peanuts Hucko et Joe Darensbourg, les pianistes Marty Napoleon et Billy Kyle, les contrebassistes Arvell Shaw, Milt Hinton, Dale Jones, Squire Gersh, Mort Herbert, Irv Manning et Bill Cronk, et les batteurs Cozy Cole, Kenny John, Barrett Deems et Danny Barcelona.

Durant son séjour avec les All-Stars, Young avait également fait des apparitions dans quelques films avec Armstrong, dont The Glenn Miller Story (1954) et High Society (1956). À la même époque, Young avait aussi participé aux plus importantes réalisations d’Armstrong. Parmi celles-ci, on remarquait des albums en hommage à W.C. Handy (sur lequel il avait interprété une version du standard ‘‘St. Louis Blues’’), et Fats Waller, une performance avec le New York Philharmonic, les tournées mondiales des All-Stars, un album avec Duke Ellington, et la revue The Real Ambassadors de Dave Brubeck. Au cours de cette période, Young avait également participé à l’enregistrement des versions originales des classiques “Mack The Knife” et “Hello Dolly.” Young avait également accompagné les All-Stars lors de 9e édition de la Cavalcade du Jazz, qui avait eu lieu au stade Wrigley Field de Los Angeles en juin 1953.

Parallèlement à son travail avec les All-Stars, Young avait aussi fait des apparitions sur des albums du trompettiste Buck Clayton en 1954, collaboré à un hommage posthume à Jimmie Lunceford en 1957, et à un album du Lawson-Haggart Band. Il s’était aussi produit avec le trompettiste Teddy Buckner dans le cadre du Dixieland Jubilee qui avait eu lieu à Los Angeles en 1958.

Peu après le succès remporté par la chanson “Hello Dolly” en 1964, au grand désappointement d’Armstrong, Young avait finalement décidé d’abandonner les tournées et de retourner à Hawaïï. En 1952, Armstrong et son gérant Joe Glaser avaient rendu hommage à Young en ces termes:

“Swing-based trombonist wanted to join the Louis Armstrong All-Stars. Must be a brilliant and flexible player, have experience working with strong leaders, and have a cheerful personality both on and offstage no matter what the circumstances. Familiarity with Louis Armstrong’s repertoire is a plus along with the ability to make every song and routine sound fresh and lively despite how many times they have previously been performed. Must enjoy traveling and be in excellent physical shape because there will be many lengthy tours. And most of all, the trombonist must love being in a supportive role because, although there will be individual features, the main purpose is to uplift the music of Louis Armstrong.”

Faisant le bilan de sa collaboration avec Armstrong, Young avait commenté: ‘’What I loved about Louis was he was melodic. I’ve always been a melodic guy; I’ve always loved melodic things. I’ve never been a guy that played a lot of exercises and things of this sort, but I’ve always been a melodic player. Now, I’ve looked at various styles of playing. Now, Bird, with all the playing he did, it was melodic. Stop and think of that.’’

DERNIERES ANNÉES

Au cours des vingt dernières années de sa vie, Young avait travaillé avec différents groupes à Hawaïï, tout en dirigeant à l’occasion ses propres formations et en participant à des tournées en Europe (notamment avec Chris Barber en 1978). Il avait également fait une apparition à la Grande Parade du Jazz à Nice, en France, au début des années 1980.

Young retournait aussi parfois aux États-Unis pour participer à des événements spéciaux comme après la mort de Louis Armstrong en 1971. Même s’il avait peu enregistré au cours de cette période, son style était demeuré intact, comme on peut le constater sur des albums comme 1971 Colorado Jazz Party, A Night In New Orleans (1973), ses enregistrements comme leader A Man & His Horn (1975) et Yours Truly (dans lequel il avait été réuni avec Barney Biggard en 1978) ou ses albums plus récents avec le pianiste Billy Dodd en 1983-84. Même si Young reconnaissait que le fait d’avoir travaillé dans différents styles musicaux l’avait influencé, il était toujours demeuré fidèle à lui-même. Il précisait:

‘’But I never did deviate too much from my original style. But you incorporated certain things. Without changing the style. You don’t even know you’re doing it. If you play with a guy like Dizzy and a guy like Bird, you’re bound to pick up a few things automatically. You don’t realize you’re picking ’em up. And every once in a while you hear a guy say, ‘Hey! Trummy! I didn’t know you played modern things!’ I say, ‘I don’t’. He’ll say, ‘Well, listen to this. And he’ll play something that I just without thinking unconsciously played because it’s so imbedded in my mind from hearing it with these guys.’’

Young avait contibué de se produire sur scène jusqu’à la fin. L’une de ses dernières performances lui avait permis de jouer aux côtés de Billy Butterfield, Kenny Davern et Eddie Miller dans le cadre du Peninsula Jazz Party en juillet 1984. Young est mort à Honolulu deux mois plus tard, le 12 septembre, à la suite d’une hémorragie cérébrale. Il était âgé de soixante-douze ans. Ont survécu à Young ses deux soeurs, son épouse Sally Tokashiki et ses deux filles Andrea (qui était devenue chanteuse de jazz) et Barbara. Selon une biographie de Young publiée dans le magazine Awake en juillet 1977, le tromboniste avait adhéré aux Témoins de Jéhovah en 1964.

©-2025, tous droits réservés, Les Productions de l’Imaginaire historique

SOURCES:

‘’Trummy Young.’’ Wikipedia, 2024.

‘’Trummy Young, 72, Is Dead;Jazz Trombonist and Singer.’’ New York Times, 12 septembre 1984.

YANOW, Scott. ‘’Trummy Young: Profile in Jazz.’’ The Syncopated Times, 30 juin 2023.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Barbara Kent-Glenn Tryon "Soledad" (Lonesome) 1928, de Pál Fejös.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

☆ I'm going ahead with the lonesome ghosts au, so here's the design for our main mouse! ☆

Distinguished gentleman :3

#mickey mouse#the wonderful world of mickey mouse#disney#art#1928#lonesome ghosts#disney au#classic mickey

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Poem of the Day 25 December 2024

"When I Set Out for Lyonnesse" BY Hardy, Thomas (1840 - 1928)

When I set out for Lyonnesse,

A hundred miles away,

The rime was on the spray,

And starlight lit my lonesomeness

When I set out for Lyonnesse

A hundred miles away.

What would bechance at Lyonnesse

While I should sojourn there

No prophet durst declare,

Nor did the wisest wizard guess

What would bechance at Lyonnesse

While I should sojourn there.

When I came back from Lyonnesse

With magic in my eyes,

All marked with mute surmise

My radiance rare and fathomless,

When I came back from Lyonnesse

With magic in my eyes!

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Blasphemer of Night

─┈ 1928 , Stormy , 22:00.

The night will blaspheme against the light, As well as the beauty, the happiness, The peace, the slumber, And every lullaby in her heart. Since then, in the future of the future, There will be no more peace in the long night.

The lonely tune on the radio kept playing amidst the faint screams in the background. it was one of the new things she had 'collected' this week.

‘ Mangia merda e muori──*scr.ᐟ.ᐟ ’

She hums along with the song, crimson hues fluttered in demure as she basked in whatever temporary respite these lonesome melodies offered her.

' Pap ! '

A single shot rang out in other room followed by a heavy thud. Oh? The song is already over..? A pity.

And here she was just starting to enjoy herself.

All good things eventually come to an end. This phrase… where did she learn of it?

She couldn't remember. How sad.

A sigh left those sweet lips.

Mm. She'll try to recall it some other time then. Their time is over here.

She got up from the shaky seat that she's been sitting on. it lets out a small pained grunt. Hm ? ‘ Ha ha… how could i forget ? ’ She spoke to no one in particular before she raises her gun.

“ Bang. ”

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

(vía Lonely Together: Paul Fejos’ *Lonesome* (1928) — The Public Domain Review)

“Lonesome”, 1928. Film directed by Paul Fejos.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Birthdays 4.16

Beer Birthdays

Emil Schandein (1840)

Mathias Leinenkugel (1866)

William H. Biner (1889)

Alan Eames (1947)

Don Scheidt (1956)

Jill Vaughn (1968)

Five Favorite Birthdays

Kingsley Amis; English writer (1922)

Aristotle; philosopher (384 B.C.E.)

Ford Maddox Brown; artist (1821)

Henry Mancini; composer (1924)

Garth Williams; illustrator (1912)

Famous Birthdays

Kareem Abdul-Jabbar; L.A. Lakers basketball player (1947)

Edie Adams; actor (1927)

Polly Adler; madam (1899)

Ellen Barkin; actor (1954)

Bill Belichick; football coach (1952)

Joseph Black; Scottish chemist (1728)

Bruce Bochy; San Francisco Giants Mgr (1955)

Charlie Chaplin; actor, comedian (1889)

Jon Cryer; actor (1965)

Merce Cunningham; dancer, choreographer (1919)

Jose de Diego; Puerto Rican political leader (1866)

Anatole France; French writer (1844)

Peter Garrett; Australian pop singer, politician (1953)

Bennie Green; jazz trombonist (1923)

Lukas Haas; actor (1976)

Wendell Johnson; speech therapist (1906)

Dick "Night Train" Lane; Chicago Cardinals/Detroit Lions CB (1928)

Martin Lawrence; comedian, actor (1965)

Herbie Mann; jazz flautist (1930)

"Pigmeat" Markham; comedian (1906)

Spike Milligan; comedian (1918)

John Millington Synge; Irish writer (1871)

Barry Nelson; actor (1917)

Ike Pappas; television journalist (1933)

"Lonesome" Dave Peverett; English bassist (1943)

Shu Qi; Chinese actor (a.k.a. Hsu Chi; 1976)

Gerry Rafferty; rock singer (1947)

Selena [Quintanilla Perez]; pop singer (1971)

Sadie Sink; American actress (2002)

Hans Sloane; naturalist, collector, British Museum co-founder (1660)

Bill Spooner; rock musician (1949)

Dusty Springfield; pop singer (1939)

Peter Ustinov; actor (1921)

Bobby Vinton; singer (1935)

Wilbur Wright; inventor, 3rd successful airplane flight (1867)

1 note

·

View note

Text

THE STATE

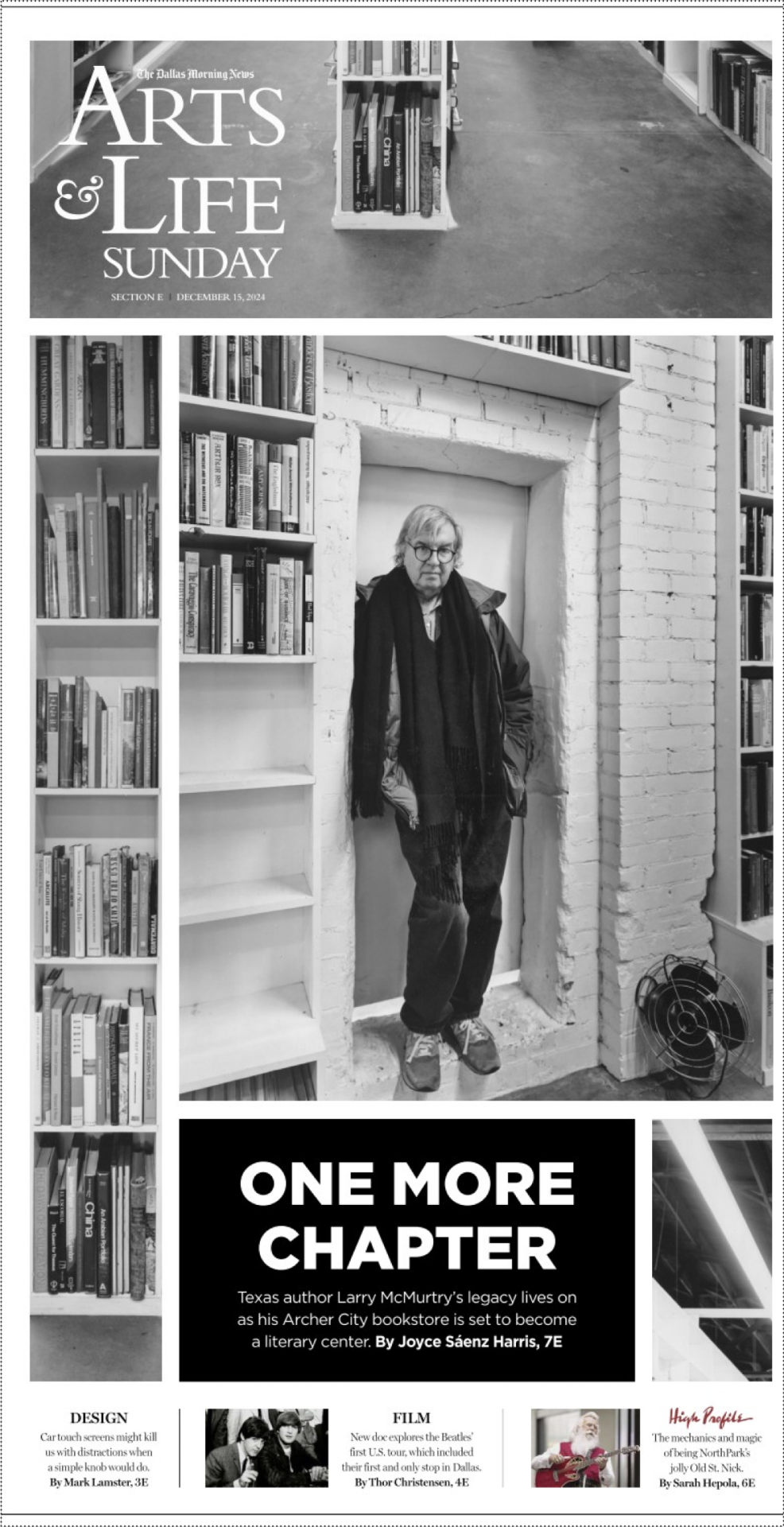

A labor of McMurtry love

Texas author’s Archer City bookstore to become a literary center, gathering place

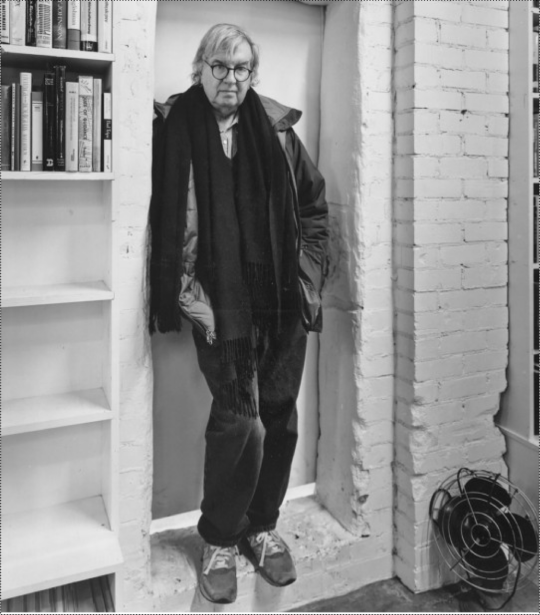

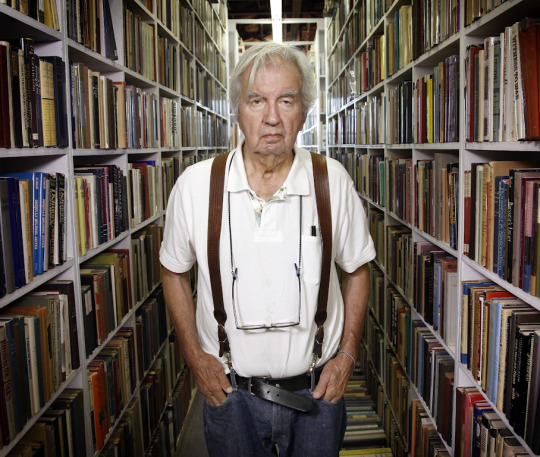

Pulitzer Prize-winning author Larry McMurtry, seen here at his Archer City bookstore in 2012, died in 2021. But the Archer City Writers Workshop wants to preserve his legacy by making the Booked Up shop into the Larry McMurtry Literary Center.

The effort is headed up by George Getschow (bottom right, with McMurtry), who also hopes some of the author’s personal furnishings that were dispersed in an auction might be loaned for exhibit.

During his 84 years, Texas writer Larry McMurtry lived in many more sophisticated places than the one where he grew up.

But his hometown of Archer City was the place that produced and shaped him, and it kept calling him back no matter how far he roamed.

Archer City, not coincidentally, also informed many of the dozens of books and screenplays he produced over the 60 years of his much-lauded writing career, such as The Last Picture Show .

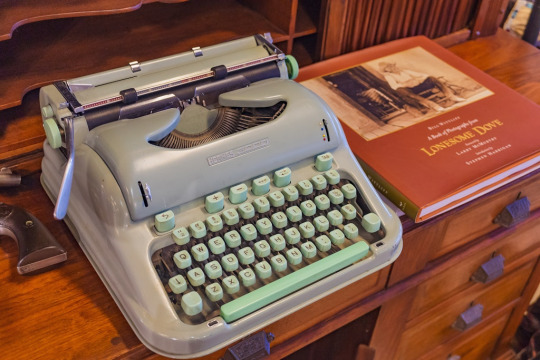

One of his books, Lonesome Dove , was the blockbuster 1985 Western novel that won McMurtry the Pulitzer Prize and boosted him to superstar status.

But the writer, who drolly called himself a “minor regional novelist,” didn’t take his fame all that seriously.

Furthermore, he said Lonesome Dove was “a pretty good book” but not, in his considered opinion, a masterpiece.

(Millions of readers would politely disagree.)

McMurtry also spent 50 years as an antiquarian bookseller, opening his original store, Booked Up, in 1971 in the historic Georgetown neighborhood of Washington, D.C.

In the 1980s, he decided to open another Booked Up, this one in downtown Archer City.

He eventually filled four gigantic, book-stuffed storefronts there, hoping to make Archer City an attraction for road-tripping book lovers, modeled after Hay-on-Wye in Wales.

Left to himself, his friends said, McMurtry would either be writing books or he would be buying books, and he did both with assiduity.

Eventually, he amassed hundreds of thousands of books that were housed at Booked Up, as well as thousands more volumes in his personal collection, kept at home in his Archer City mansion and its carriage house.

After McMurtry’s death in March 2021, TV’s Fixer Upper power couple Chip and Joanna Gaines purchased Booked Up and moved about 10,000 of its vintage volumes to decorate their new Hotel 1928 in Waco.

Recently, the Gaineses sold Booked Up to the Archer City Writers Workshop. Now, a big idea with enthusiastic local support promises to bring major changes — and thousands of visitors — to McMurtry’s hometown.

As you read this, an energetic group of bookish folks has just completed moving 80,000 of McMurtry’s books across Archer City’s South Central Avenue, from Booked Up No. 2 to Booked Up No. 1.

They plan to turn No. 1 into the Larry McMurtry Literary Center, which will be the first such public institution to preserve an author’s legacy in Texas.

“Larry called this place his ‘temple of books,’” says George

Getschow, who is heading up the project with the Archer City Writers Workshop.

“It was his sacred place.”

Archer City already has one official Larry McMurtry Literary Landmark in the town’s public library that McMurtry supported with a major gift;

it is one of several Texas libraries given the landmark designation in honor of a local person.

But Getschow, the director emeritus of the Mayborn Literary Nonfiction Conference at the University of North Texas, envisions the literary center as something bigger: the kind of library and gathering place that already exists in a dozen other cities to draw fans of American writers like Mark Twain, John Steinbeck, Eudora Welty, Emily Dickinson, Willa Cather, Nathaniel Hawthorne and Jack Kerouac.

Furthermore, Getschow says, the center will feature McMurtry’s separate, private collection of 27,000 books from his carriage house, volumes that were acquired by Dallas bookman James Gannon.

There will be listening stations for recorded books, revolving exhibits examining different aspects of the author’s life and work, and the writers workshop’s regular gatherings will move over from the group’s current base at the Spur Hotel.

Visitors will be able to buy selected books from the collections, and copies of McMurtry’s publications will be available in the gift shop, along with T-shirts, tote bags and souvenirs.

“I’m thinking we should have some little blue pigs,” Getschow says, alluding to the rattlesnake-eating porkers that appear in the opening lines of Lonesome Dove .

But before all that can happen, there is much work to be done.

Now that the books are moved over, Booked Up No. 1 will undergo urgent repairs and rehabbing to make it clean, powered-up and water-tight, a project that has support from the city.

Later, bookshelves will be brought in, and HVAC systems will be installed.

Getschow is also hoping to retrieve at least some of McMurtry’s personal furnishings, such as his desk, chair and typewriter, pieces that were dispersed in an auction but might be loaned for exhibit if the new owners are amenable.

Untold months of planning and execution lie ahead, but for Getschow and the Archer City Writers Workshop, this is a labor of love.

“I’m devoting the final years of my life to developing this,” the 74-year-old says.

0 notes

Text

William Levi Dawson (September 26, 1899 – May 2, 1990) was a composer, choir director, professor, and musicologist.

He was born in Anniston, Alabama. He ran away from home to study music as a student at the Tuskegee Institute. He paid his tuition by being a music librarian and manual laborer working in the Agricultural Division. He participated as a member of Tuskegee’s choir, band, and orchestra, composing and traveling with the Tuskegee Singers for five years; he had learned to play most of the instruments by the time he completed his studies. A graduate of the Horner Institute of Fine Arts with a BS in Music, he studied at the Chicago Musical College and then at the American Conservatory of Music where he received his MA. He served as a trombonist both with the Redpath Chautauqua and the Civic Orchestra of Chicago. His teaching career began in the Kansas City public school system, followed by a tenure with the Tuskegee Institute. He appointed a large number of faculty members who became known for their work. He developed the Tuskegee Institute Choir into an internationally renowned ensemble; they were invited to sing at New York City’s Radio City Music Hall.

He began composing at a young age, and early in his compositional career, his Trio for Violin, Cello, and Piano was performed by the Kansas City Symphony. He is known for his contributions to both orchestral and choral literature. His works are arrangements of and variations on spirituals. His Negro Folk Symphony garnered a great deal of attention at its world premiere by Leopold Stokowski and the Philadelphia Orchestra. The symphony was revised with added African rhythms inspired by his trip to West Africa. His most popular spirituals include “Ezekiel Saw the Wheel”, “Jesus Walked the Lonesome Valley”, “Talk about a Child That Do Love Jesus”, and “King Jesus Is a-Listening”. He was elected to the Alpha Alpha chapter of Phi Mu Alpha Sinfonia.

His arrangements of traditional African American spirituals are published and are regularly performed by the school, college, and community choral programs.

He married pianist Cornelia Lampton in 1927; she died in 1928. #africanhistory365 #africanexcellence

1 note

·

View note