#lm 4.2.4

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

This chapter offers an extended encounter with Éponine, and I'm pleased for the deeper insight! Hugo claims that despite the fact that she went through much distress and increasing poverty, she is becoming prettier. She sleeps in some stable, and she has “in her face that indescribably terrified and lamentable something which sojourn in a prison adds to wretchedness,” but she is still beautiful, because, according to Hugo, youth prevails. (Perhaps the absence of an abusive father and a newfound purpose in life contribute.)

Éponine is extremely talkative and sincere with Marius (he certainly does not deserve such openness): “How I have hunted for you! If you only knew! Do you know? I have been in the jug. A fortnight!” She clearly holds an idealized image of Marius in her head, and the real Marius falls short of it: “Why do you wear old hats like this! A young man like you ought to have fine clothes,” and “you have a hole in your shirt. I must sew it up for you.” She obviously envisions him as a perfect gentleman, impeccably dressed in a fine hat and shirt. Yet, as we know, his clothes are tattered, and he can't afford new ones. (I’ve just realized that Éponine is aware that Montparnasse always dons “fine clothes,” but she’d probably prefer to see Marius like this). After this surge of candidness and care, she finally realizes that Marius isn't pleased to see her. He's reverted to addressing her with “vous” instead of “tu.” His grabbing her arms and nearly shaking her, while sternly demanding she keep Cosette's whereabouts from her father (the same man he regularly sends money to), is distressing and unjust.

Then comes the truly heart-wrenching part: “‘You are following me too closely, Monsieur Marius. Let me go on ahead, and follow me so, without seeming to do it. A nice young man like you must not be seen with a woman like me.’ / No tongue can express all that lay in that word, woman, thus pronounced by that child.” Once again, Éponine embraces her own internalized stigmatization, even though Hugo explicitly acknowledges its excessiveness, almost lamenting it. The coin Marius offers her (at this point, he has hardly any money that isn't borrowed) is the final straw. It transforms her from the cheerful and chatty birdy she was initially into a sombre and despondent apparition: “She opened her fingers and let the coin fall to the ground, and gazed at him with a gloomy air. / “I don’t want your money,” said she.” I can clearly see a close-up of this falling coin. Oh, it’s so sad!

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm still catching up with Les Mis Letters so I just read An Apparition To Marius (LM 4.2.4) and oh boy I can still remember reading this sequence (an abbreviated version) in high school French class for the first time. The last line hit just as hard as it did then. "I don't want your money."

Éponine is so painfully aware of her standing in society. It's fully internalized. She wishes Marius were happy to see her yes, but it's so much more important for her that Marius be happy. You can tell that leading Marius to Cosette in order to see him happy is tinged with melancholy for her, but I don't think she ever considers that it could be any other way.

“'A nice young man like you must not be seen with a woman like me.' No tongue can express all that lay in that word, woman, thus pronounced by that child.”

I don't really have any more coherent thoughts I'm just over here shedding a tear about how well-written and sad this chapter is.

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

Marius deciding that he’ll be able to work if he goes out and then realizing working is hopeless for the day feels very accurate.

Éponine’s interaction with Marius hurts to read. She’s so happy to see him, and he’s simply depressed and and absorbed in Cosette. Her lengthy speech resembles that of Valjean upon meeting the bishop and being invited in; it’s the rant of a misérable who feels like they’re being listened to for once, but Marius isn’t actually listening. And there are horrific details in there! She was released from prison, but she spent two weeks in there without proof that she’d done anything! And she did find a place to sleep, but it was a barn, suggesting that she’s once again homeless.

Another aspect of what she says that reminds me of Valjean is what she says about barons. It’s similar to what he said about church figures: the kind person in front of them can’t be of that stature because someone of that rank would at most interact with them for work. Éponine is puzzled that Marius could at once be a baron and be friendly to her.

He also doesn’t look the part. Aside from her image of barons as old, Marius is very poorly dressed. Her comments on his clothes speak to her idealization of him – his shabby garments make sense given his poverty, but Éponine doesn’t see him as poor because 1) he’s much better off than she is and 2) she doesn’t want to. She wants Marius to be happy, and that includes more stability than he really has. Her offer to mend his shirt is another instance of her using favors as a form of kindness, but it also allows her to build this image of a prosperous, benevolent Marius that doesn’t really exist.

(Her standards for young men may also have been affected by Montparnasse, who always wears “fine clothes” because that’s his priority; Marius has other ones (and possibly less money)).

And she succeeds in making Marius happy like she wishes! But she does so in a painful way, as who makes Marius happy is the wealthy girl that she can never be. She smiles at his happiness, but not for long, soon reinforcing the class boundary between them:

“

You are following me too closely, Monsieur Marius. Let me go on ahead, and follow me so, without seeming to do it. A nice young man like you must not be seen with a woman like me.”

No tongue can express all that lay in that word, woman, thus pronounced by that child.”

Hugo himself points out that Éponine is a child, but she applies adult standards to herself as a form of demonization here. The implication is that it would be improper for Marius to be seen with her because she’s poor, possibly because of the scandalous implication of sex work. She wants to protect him from that, but that’s a horrible standard to place on anyone. Worst of all, it’s being placed on a child!

And in bringing that up, Éponine increases the metaphorical distance between herself and Marius, too, making their relationship less one of friends and more like that delivery for the old baron she mentioned before. Marius’ assumption that she wants money just reinforces that division, telling her he sees her as a means to an end rather than a friend. It’s heartbreaking.

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

LES MIS LETTERS IN ADAPTATION - An Apparition to Marius , LM 4.2.4 (Les Miserables 1972)

“Ah!” she went on, “you have a hole in your shirt. I must sew it up for you.” She resumed with an expression which gradually clouded over:— “You don’t seem glad to see me.” Marius held his peace; she remained silent for a moment, then exclaimed:— “But if I choose, nevertheless, I could force you to look glad!”

#:(((( Baby :(((#Eponine#Eponine Thenardier#Les Mis#Les Miserables#Les Mis Letters#les Mis Letters in Adaptation#Les Mis 1972#Les Miserables 1972#lesmisedit#lesmiserablesedit#pureanonedits#Marius Pontmercy#Marius

147 notes

·

View notes

Text

Brickclub 4.2.4 ‘An apparition to Marius’

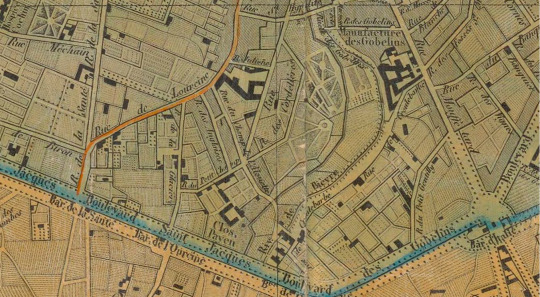

I’m not managing to pinpoint exactly where Marius is sitting, but it’s around here. This is what at the time was the southernmost corner of Paris, close to the Barriere d’Italie. The Rue de Croulebarbe runs up the middle of this image, and the Rue du Champ du Allouette runs north-ish to the west of it. The Rue de la Santé, though, also runs north, off to the west of both of them. I’m not sure exactly where he is, though, because Santé doesn’t intersect with the others. The Gobelins factory, which made tapestries and furnishings, is up at the top, along with the Bièvre river it was built on, which must be near the smaller stream Marius is sitting by.

He heard behind and below him, on both banks of the stream, the washerwomen of the Gobelins beating their linen; and over his head, the birds chattering and singing in the elms. On the one hand the sound of liberty, of happy unconcern, of winged leisure; on the other, the sound of labour. A thing which made him muse profoundly, and almost reflect, these two joyous sounds.

Two joyous sounds. Jeez.

This is Bad. Champmathieu’s daughter was a washerwoman who died young. Hugo isn’t letting us off with not knowing what this job was like:

“Then I had my daughter, who was a washerwoman at the river. She earned a little for herself; between us two, we got on; she had hard work too. All day long up to the waist in a tub, in rain, in snow, with wind that cuts your face when it freezes, it is all the same, the washing must be done; there are folks who haven't much linen and are waiting for it; if you don't wash you lose your customers. The planks are not well matched, and the water falls on you everywhere. You get your clothes wet through and through; that strikes in. She washed too in the laundry of the Enfants-Rouges, where the water comes in through pipes. There you are not in the tub. You wash before you under the pipe, and rinse behind you in the trough. This is under cover, and you are not so cold. But there is a hot lye that is terrible and ruins your eyes. She would come home at seven o'clock at night, and go to bed right away, she was so tired. Her husband used to beat her. She is dead.”

Marius continues to profoundly miss the point.

Anyway, he’s caught between the goblin and the lark, not that he’s paying any attention to the goblin.

Hugo does a nice job making his brain-state clear. Marius sits down to work every day, and nothing is connecting in his head, and he can’t make it happen. It’s sad and frustrating that his depression compounds his usual lack observation skills to make him even less able to perceive Eponine. But it’s understandable.

Poor Eponine. Hugo is being weird about her having become more beautiful, but I’m going to give him a tentative pass for now. There’s a decent chance this is about this book’s usage of beauty as internal illumination rather than outward appearance, and he’s alluding at least partially to the moral transformation she’s been undergoing.

“She had, in addition to her former expression, that mixture of fear and sorrow which the experience of a prison adds to misery.”

With Brujon, going to prison was just another Thursday, but we haven’t left behind the world Jean Valjean came from, where going to prison changes a person in permanent and terrible ways. Eponine has been changed that way.

Marius is overjoyed at the news that he can see Cosette, because of course he is.

His plot isn’t happening the way plots are “supposed” to happen--character wants something, character takes steps to go and get it, complications ensue--and I think that’s on purpose. Marius is missing all the things that matter, and failing to take the actions that would make a difference. He’s squeaking by largely on the advantages birth and chance gave him--social class, manners, education, good looks, absolutely magical friends, etc--and that’s enough to get him the girl and the happy ending.

I’m not blaming him--his mental illness isn’t his fault. But he’s an unsatisfying character to follow because he’s meant to be. He keeps missing all the things this book stands for, and which the reader in his stead is being strongly encouraged not to miss in their own life.

And Eponine is experiencing the moral reckoning and burgeoning agency that seems structurally like it should have been his. She’s lied for him, she’s made moral judgments for the first time in her life, she’s noticed people in pain and been kind.

And this chapter, she’s weighing being selfless to someone she cares about because he’s sad and she wants to make him happy, even though it will lose her any chance at the thing she most wants.

And she does it. But even when she’s being selfless, she asserts her own dignity. She draws the line between their social classes herself, rather than seeing how much he will and won’t give her, and she refuses to let him make this exchange into something she did for money.

ETA: GOD, I just noticed that Gillenormand’s rooms are decorated in Gobelins tapestries. I don’t know, I can’t quite lay out the metaphor succinctly, but it feels important. There’s such a stark divide here with Marius benefiting from Eponine’s goblin status and from hers and other people’s labor, and he doesn’t even notice that there *was* sacrifice or labor.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Brickclub 4.2.4, “Marius’s Visitation”

Marius has stopped working--the text of 4.2.1 says he had done this even before the ambush--and while some of Hugo’s laudatory prose about work is just Hugo being gross, not working seems to be both a symptom and a contributing factor to Marius’s depression, in the way these things often go:

As soon as he got up in the morning, he would sit down in front of a book ans a sheet of paper to dash off some translation [...] read four lines, try to write one, not succeed, he would see a star that came asterisk-like between himself and the page, and he would rise from his chair, saying “I’ll go out. That will get me started.”

[...]

He would come home, try to resume his work, and fail. Impossibly to repair a single one of the broken threads in his brain. Then he would say to himself, “I shan’t go out tomorrow. It stops me working.” And he would go out every day.

That is sure one Big Depression Mood there.

His wandering thoughts, turning to reproach, came back to himself. He reflected dolefully on the idleness, paralysis of spirit, that was overtaking him, and on the darkness before him, growing denser moment by moment so that already he could not even see the sun any more.

Yet, through this painful emergence of hazy notions that did not even constitute a monologue, so debilitated was his capacity for action, which he no longer had even the strength of will to lament any more, through this melancholy self-absorbtion sensations from the outside world did reach him.

He is explicitly not even able to monologue or to complain. Once again, he is not even meeting Grantaire’s standards.

And the sensations reaching him from outside are the sound of birds (fine) and of the Gobelins laundresses beating their linen, and Marius becomes pensive over how joyous both sounds seem to him.

Having lost the ability for action and agency to the extent he has, I can kind of see how the sound of people at work might seem just as inaccessible to him as the sound of birds in flight--but we’re still in the neighborhood of the Boulevard de l’Hôpital, where Champmathieu’s daughter was a laundress--possibly even for the Gobelins factory. This is horrible, backbreaking labor, and for Marius it’s just part of the scenery.

It is in this state that Eponine finds him. She has gained some of the moral beauty that characters in this book can have--breaking with her father has given her some glimmer of hope and made her seem closer to her actual age, despite being two months more ragged and filthy. She reaches out to Marius, offering to show him Cosette’s house knowing that it will only make her jealous and sad, but that it will make Marius happy:

And Marius--oof.

She withdrew her hand and went on in a tone of voice that would have cut to the heart anyone watching--but Marius, now enraptured, in transports of delight, did not even notice-- “Oh, how happy you are!”

And, when she in turn is so delighted by being called by her name that she doesn’t respond immediately to Marius’s injunction not to tell her father, Marius--seizes her and shakes her:

Marius held her by both arms.

“For heaven’s sake, answer me! Listen to what I’m saying. Swear to me you won’t tell your father the address that you know!”

“My father?” she said. “Ah, yes, my father! You needn’t worry. He’s locked up. In any case, as if I care about my father!”

“But you haven’t promised!” exclaimed Marius.

“Now let go of me!” she said with a burst of laughter. “You’re shaking me so hard. Yes, yes, I promise! I swear! What’s it to me? I won’t tell my father the address. There! Satisfied? Is that what you wanted?”

I have to say, if Marius had killed Cosette and himself, instead of just slinking off to commit suicide by barricade, no one could say Hugo hadn’t foreshadowed it.

And also... I can’t help thinking this is yet another fate that Eponine has traded with another character. She and Cosette have their zero-sum game, where every one of Cosette��s gains in fortune and love is countered by a loss for Eponine. She trades the drowning death foreshadowed for her with Javert, and is shot at the barricade as he was meant to be. And she has the romantic murder-suicide with Marius that the book teases lies in store for Marius and Cosette.

Eponine is two months shy of the age of criminal responsibility. She and Cosette being mostly of an age, that means she must be not quite sixteen. It’s now right around the middle of March. If Cosette was conceived on the date of Waterloo, as we suspect, then her birthday is right about now, and Eponine is two months younger, but I didn’t find anything around mid-August of 1815 that seems similarly significant for her conception. Louis the XVIII had returned to Paris in July; the closest thing I could find was August 7, the day Napoleon was transferred to the Northumberland to begin his second exile.

7 notes

·

View notes