#lizabeth David

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

There are people who take the heart out of you, and there are people who put it back.

lizabeth David

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

#BidensBorderBloodbath

It would be a real shame of we got #BidensBorderBloodbath to trend!

Definitely don’t tweet out #BidensBorderBloodbath!

You know what the real 'Bloodbath' is?

It's illegals invading our country and committing m*rder.

REMEMBER THEIR NAMES:

Laken Riley

Christopher Gadd

Lizabeth Medina

Melissa & Riordan Powell

David Hadrich

Cindy Goulding

Cheston Edwards

Deborah Brandao

Nazareth Tamer-Claure

Connor Holcomb

Andi Lynn Blair

Isidro Cortes

Moussa Fofana

Mafalda Thayer

Corbin Wagner

Gretchen Gross

Aiden Clark

Michael Kunovich

Erpharo Gilbert

Kayla Hamilton

Maria Rios

Ian Matteo Garcia

Diane Hill Luckett

@catturd2

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

HE SURE IS A PRINCE!

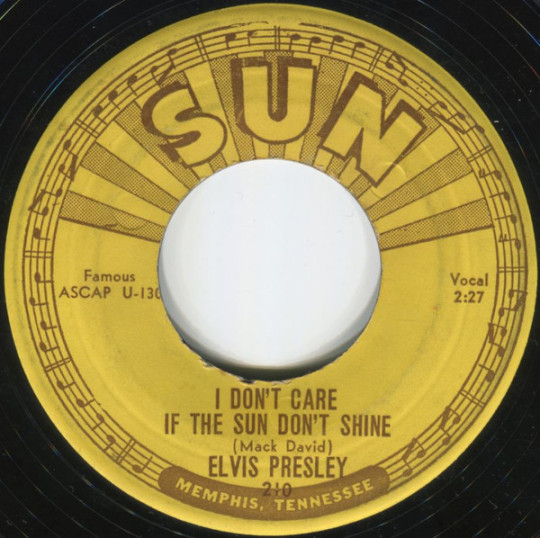

"I Don’t Care If The Sun Don’t Shine"

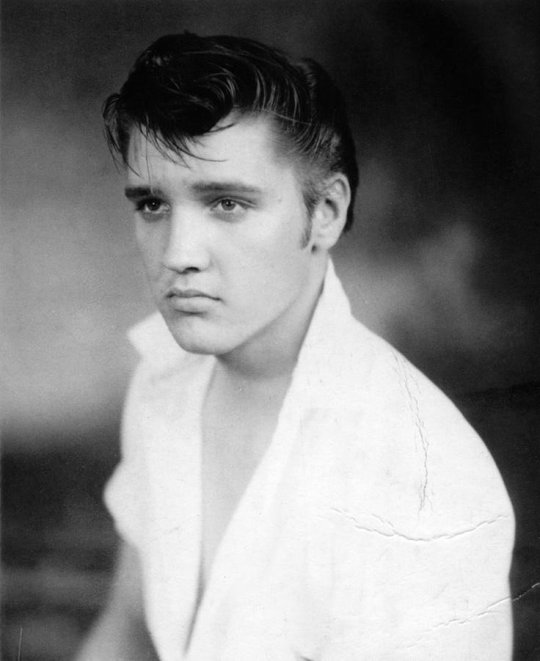

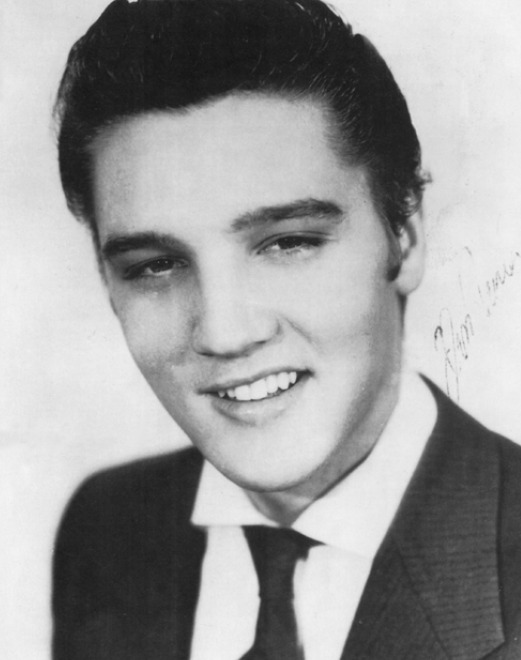

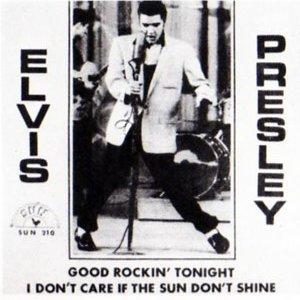

[1] Elvis photographed at the Blue Light studio in Memphis, 1954. [2] Cinderella, a Disney movie released in 1950. [3] Elvis' first Sun Records publicity portrait, 1954.

Studio Sessions for Sun September 10–?, 1954: Sun Studio, Memphis The songs that came to Elvis’s mind were as motley a crew as can be imagined, yet each one was drawn from his own experiences. His prodigious memory helped him dredge up songs from the oddest places, and the Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis movie "Scared Stiff" was one. He recalled Martin’s rendition of a number called “I Don’t Care If The Sun Don’t Shine,” which had actually been written for Cinderella but was never used in the Disney film. The movie version differed from Martin’s 1950 recorded version, and it was the screen performance he remembered; he took Martin’s approach one step further, speeding the song up, solidifying the beat, and adding an energetic vocal delivery on top.

Excerpt: "Elvis Presley: A Life in Music" by Ernst Jorgensen. Foreword by Peter Guralnick (1998)

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

“I Don't Care If The Sun Don't Shine” was written by Mack David in 1949 for the Disney film “Cinderella”, but the song ended up being misused for the film released in the early 1950. The song was recorded by different artists during the following years. For instance, in addition to Dean Martin, Patti Page is another artist for whom Elvis had the greatest admiration. Her version of “I Don’t Care If The Sun Don’t Shine” was released in 1950. It’s not strange to assume that Elvis also heard her version before recording the song in 1954.

youtube

Here's Dean Martin performing the song in scene from movie "Scared Stiff " (1953):

youtube

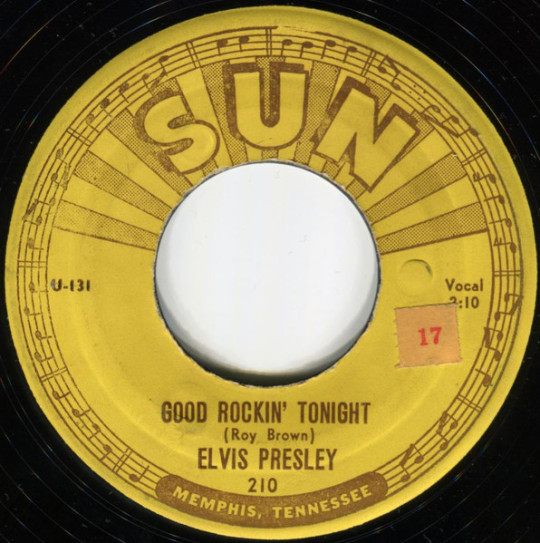

Elvis recorded the song on September, 1954 and it was first released as a single on October 4 the same year, with B-side "Good Rockin' Tonight".

Listen to “I Don’t Care If The Sun Don’t Shine” by Elvis Presley — Guitar: Scotty Moore, Elvis Presley. Bass: Bill Black

youtube

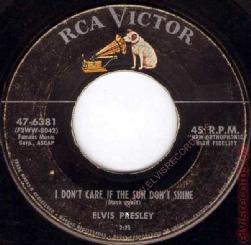

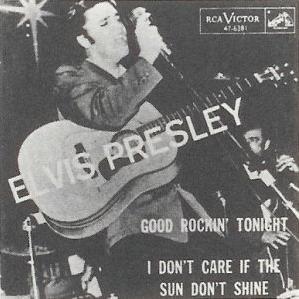

When Elvis signed with RCA Records in late 1955, RCA reissued all five of his Sun singles, inclusing "I Don’t Care if the Sun Don’t Shine" / "Good Rockin’ Tonight".

RCA's reissue of Sun Records' original Elvis Presley singles.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

FURTHER INFO

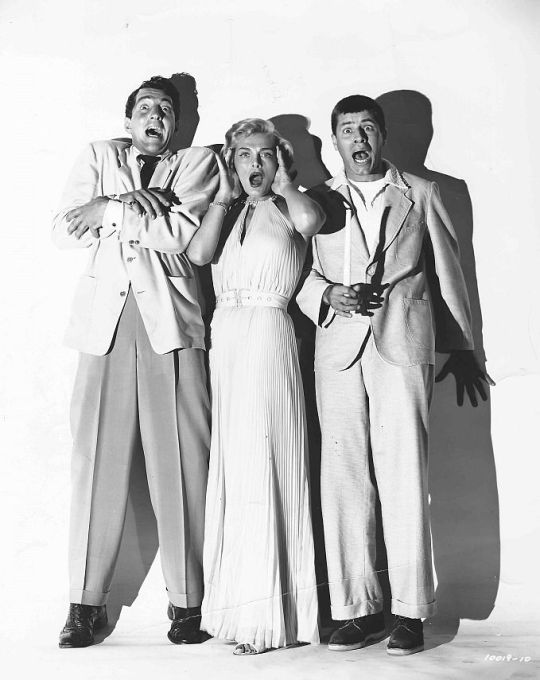

Are you curious with the movie the King watched and which inspired him in some level to pick a song for his early records? Watch the 1953 movie 'Scared Stiff, starring Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis: dailymotion.com

FUN FACT: Our dear Lizabeth Scott (Loving You, 1957) is also in this movie, playing Mary Carroll.

Dean Martin, Lizabeth Scott and Jerry Lewis in "Scared Stiff" (1953)

Elvis photographed in 1954.

CREDITS FOR THIS POST: Ernst Jorgensen and his amazing book, "Elvis Presley: A Life in Music", one of my favorites which I keep at reach all times; for the Sun Records and RCA's 1954 single sleeves and respective release dates: elvis100percent.com and Discogs; for pictures: IMDb.com and Pinterest, for movie and song info, Wikipedia and elvisthemusic.com, and for the recordings, Youtube.

#this is one of my definitive favorite Sun Records era recording of Elvis#I'm so surprised it was firstly a Cinderella sountrack#yep... El was definitely a prince#elvis#50s elvis#elvis history#elvis music#sun records#1954#patti page#dean martin#jerry lewis#lizabeth scott#scared stiff#1953 movies

28 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

ASK EDDIE - August 24 2023

FNF prez Eddie Muller responds to film noir fan questions fielded by the Foundation's Director of Communications Anne Hockens. In this episode, we discuss the recent changes at TCM, Eddie’s memories of Robert Osborne, the new Philip Marlowe book, The Second Murder, Poker Face and its inspiration Columbo, female investigators in film noir, and more. We wind up the show with a new game, “Femme Fatale or Not?”. On the cat front, Charlotte is a diva and Emily won’t come out of her trailer.

Want your question answered in a future episode? We solicit questions from our email subscribers in our monthly newsletters. Sign up for free at https://www.filmnoirfoundation.org/signup.html

Everyone who signs up on our email list and contributes $20 or more to the Film Noir Foundation receives the digital version of NOIR CITY Magazine for a year. Donate here: https://www.filmnoirfoundation.org/contribute.html

This weekend’s questions:

1. I am wondering if there's a way to find out which movies screened at the first NOIR CITY. I'm also wondering when you first started distributing those spectacular programs.

Jeannin

2. Would you address the recent cutbacks and layoffs at TCM that are affecting NOIR ALLEY.

Andrew

3. I would love to know about your relationship with Robert Osborne.

Stacy

4. The estate of Raymond Chandler hired Scottish crime fiction writer Denise Mina to pen a new Philip Phillip Philip Marlowe novel, THE SECOND MURDERER was released in August. Have you read it and if so, what did you think? What do you think in general of the practice of having contemporary authors pen reboots based on other writers' classic detective characters? Are there any examples of this that you think are particularly well-done--OR that you think egregiously miss the mark?

Kathleen

5. Have either of you seen the new TV series POKER FACE? It’s not a whodunit. It’s a howcatchem. It’s been said it’s a homage to the old COLUMBO series. Were you two fans of COLUMBO. Was Peter Falk ever in a noir movie?

Alan, San Anselmo, CA

6. Would love to see THE ENFORCER, 1952, starring Bogart presented on NOIR ALLEY sometime soon. I wonder about the film’s backstory. What parts of the film really portrayed the "Murder Inc.", if any?

Victor

7. Since becoming interested in film noir, I have seen several films with Richard Basehart. Did he ever talk about his career in noir films? I saw Basehart live on stage in the late 1970’s playing Macbeth at a theatre near Philadelphia. Did any other “noir” actors perform Shakespeare on stage?

Ed, Washington, D.C.

8. What do you think of Roger Corman's 1962 film THE INTRUDER? And do you consider it to be noir? Doug, Silver Spring, MD

9. I was curious to hear Eddie's opinion on directors William Dieterle, Delmer Daves, Anthony Mann, Robert Wise, Jean Negulesco and which of their film noirs are worth watching.

Jeff from Montreal

10. I was intrigued by the plot of Joseph Pevney’s UNDERCOVER GIRL (1950) because it centers on a policewoman working. I couldn’t find UNDERCOVER GIRL anywhere- to stream or buy.

My question is two-fold. How rare is this type of character in film noir? And why can I not find this film (and other films like this)?

Kellee, Kansas

11. Was The movie PUBLIC ENEMY recut? I ask because Jean Harlow's role is so short and feels like it was recut. I know that the Hayes code had just come into effect so that adds to my suspicion.

David

12. Anne and Eddie: How many emails do you each get each day connected with movies? Is it overwhelming?

Alan

13. Does Eddie or Anne have a favorite or memorable tagline associated with a noir film? Also, is it Tizzie with an "ie" or Tizzy with a "y"? Inquiring minds need to know.

Timothy, Schenectady NY

14. I’d like to propose a new game: ‘Femme Fatale or Not?’ And start off with one tough (or maybe off the wall) example:

PITFALL (1948) (dir. André De Toth) - Mona Stevens (Lizabeth Scott) is not a femme fatale in this film but Sue Forbes (Jane Wyatt) is. I’ll stop here and see what you and Anne think (about the concept and my interpretation of Wyatt’s character.

Dave in Pie Creek, Queensland

#youtube#film noir#film noir foundation#noir city#eddie muller#anne hockens#tcm#robert osborne#philip marlowe#the second murder#poker face#columbo#peter falk#the enforcer#richard basehart#the itnruder#undercover girl#jean negulesco#public enemy#pitfall#lizabeth scott#jane wyatt

5 notes

·

View notes

Link

The American Pageant AP Edition (17th edition) - eBook eBook Details Authors: David M. Kennedy, Lizabeth Cohen File Size: 452 MB Format: PDF (scanned) Length: 1359 Pages Publisher: Cengage Learning; 17th edition Publication Date: January 17, 2019 Language: English ISBN-10: 1337915572, 0357380029 ISBN-13: 9781337915571, 9780357380024, 9780357995426

0 notes

Text

~◇ Venomous ◇~

Lizabeth Davids on an Undercover Mission

(NSFW (Bloodwise) version found on my Patreon)

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Hi there everyone! @pikafan09 here, and today, I digitally drew David (me/my OC) holding his Nintendo Switch to show y'all the Shiny Giratina that he recently found and caught in his Pokémon Ultra Sun game after 522 encounters total! I was nervous when starting the hunt considering Dialga took a long time for it to appear as shiny, and alas, it appeared quicker than I thought. And if you are wandering why is Lizabeth doing here? Reason: because I was at my friends house watching Sword Art Online War of the Underworld part 2 when the shiny appeared. So here, I'm putting my favorite SAO character next to me in commeration of last weekend's success! XD

__

Lizabeth is from the Sword Art Online Series

David (me/my OC) is made by @pikafan09 /Pikapunch25 (me)

Giratina is from Pokémon (Both Forms)

#Pokemon#Pokémon#Sword Art Online#Crossover#David#Trainer David#OC#Giratina#Shiny Giratina#Shiny Pokémon#Legendary Pokémon#Lizabeth#Lisabeth#Rika Shinozaki#Anime#Manga#Video Games#MyArt#Digital Fan Art#Pikafan09#Pikapunch25#TrainOn#Train On#ScarletViolet

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

My history textbook is a delight

My AP U.S. History textbook (American Pageant Vol. 1, 15th ed. by David M. Kennedy, Lizabeth Cohen) is quite something.

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Would you guys be interested in learning about my ocs?

This is just out of curiosity tbh. I’d like to interact with my followers/enjoyers of my fics (if there are any). My ocs are listed below along with their ships. If you want to know about my ocs just say their name and I’ll post their character sheet and faceclaim as well as say how many fanfics I’ve written for them.

Harry Potter

Marauders Era

Ella Underwood (James Potter, Henry Potter)

Gaia Devereaux (Sirius Black)

Violetta Cook (Remus Lupin)

Cecelia Potter (Regulus Black)

Madeline Potter (Xenophilius Lovegood)

Henry Potter (Dorcas Meadowes, Ella Underwood)

Antonius Black (N/A yet)

Adina Black (Barty Crouch Jr.)

Cairo Lupin (Isadora Diamandis)

Isadora Diamandis (Cairo Lupin)

Golden Era

Anastasia Lestrange (Harry Potter)

Rayna Longbottom (Ron Weasley)

Cecily Sadler (Draco Malfoy)

Mallorie Bishopp (Fred Weasley)

Corinne Alastair (George Weasley)

Cassandra Foster (Percy Weasley)

Adora Parrish (Charlie Weasley)

Sophia O’Malley (Bill Weasley)

Chloe Eratos (Ginny Weasley)

Calypsa Trelawney (Luna Lovegood)

Dinah Fanley (Cedric Diggory)

Charlotte Creevey (Neville Longbottom)

Jessica Stix (Oliver Wood)

Holly Diggory (Viktor Krum)

Ophelia Teagarden (Nymphadora Tonks)

Judith Stix (Seamus Finnigan)

Marvel

Rosemary Clover (Tom!Peter Parker)

Andrea Louis (Bruce Banner)

Hannah Clearwood (Tony Stark)

Alina Cetus (Pietro Maximoff)

Amy Penn (Sam Wilson)

Georgia Barnes (Steve Rogers)

Minna Olesia (Natasha Romanoff)

Ingrid Meller (Stephen Strange)

Maeve Nadine (Andrew!Peter Parker)

Hali Brooks (Benjamin Barnes)

Lyra Beatrix (Brunhilde)

Valerie Urson (Quentin Beck)

Julie and the Phantoms

Daisy Sloane (Luke Patterson)

Hattie Rowland (Reggie Peters)

Evangeline Buchanan (Alex Mercer)

Danielle Poet (Willie)

Juniper Dalton (Charlie Gillespie)

Allison Hicks (Jeremy Shada)

Hazel Matthews (Owen Joyner)

Mila Evans (Booboo Stewart)

The Hobbit

Pandora Potts (Bilbo Baggins)

Sienna Hollyfoot (Thorin Oakenshield)

Nessa Thorn (Kili Durin)

Celeste Nasrin (Fili Durin)

Gemma Rankin (Bofur Rankin)

Roslyn Stardust (Bard the Bowman)

Aster Everwood (Thranduil Oropherion)

Iris Cricket (Elrond Peredhil)

Marina Willow (Lindir Talierin)

Artanis (Erestor)

Elletta Nightstone (Glorfindel Laurefindelë)

Netra Underlake (Elladan Peredhil)

Adaia Taleasin (Elrohir Peredhil)

Lord of the Rings

Lalia Featherborn (Frodo Baggins)

Brooke Bilberry (Merry Brandybuck)

Camelia Tunnelly (Pippin Took)

Adelaide Stoor (Samwise Gamgee)

Issa Goodwin (Aragorn)

Citra Underlake (Boromir)

Alphine Barrowes (Legolas Greenleaf)

Mirabella Holidan (Haldir)

The Lost Boys (1987)

Elizabeth Carlton (Paul)

Julie Burton (Dwayne)

Wendy Miller (David)

Heather Brown (Marko)

Edith Jackson (Michael)

Twilight

Hilda Snow (Paul Lahote)

Amarie Taylor (Leah Clearwater)

Raven Lance (Edward Cullen)

Eleanor Martin (Charlie Swan)

Arielle Swan (Seth Clearwater)

Anastasia Whitlock (Demetri Volturi)

Olivia Hale (Caius Volturi)

Charity Cullen (Embry Call)

Sarah McCarty (Edward Cullen, Alec Volturi)

Misc.

Cruella (2021)

Angela Young (Jasper Badun)

Amethyst Ellet (Cruella de Vil)

Gemma Harlow (Artie Katz)

Isabel Abbott-Fry (Joel Fry)

Hannibal (2013)

Maya Morano-Graham (Will Graham)

Fleur Ramsey (Hannibal Lecter)

Celine Lennox (Hannibal Lecter, Will Graham)

Lizabeth Alva (Hugh Dancy)

Prodigal Son 2019

Elena Nadis (Malcom Bright/Whitly)

Plebs (2013)

Helena (Stylax)

Karisa (Marcus)

Sofia Riley (Tom Rosenthal)

Lucy Margeaux (Ryan Sampson)

Random

Kiyara Tallhart (Hizdahr zo Loraq)

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Richard Ewing Powell (November 14, 1904 – January 2, 1963) was an American singer, actor, voice actor, film producer, film director and studio head. Though he came to stardom as a musical comedy performer, he showed versatility, and successfully transformed into a hardboiled leading man starring in projects of a more dramatic nature. He was the first actor to portray the private detective Philip Marlowe on screen.

Powell was born the middle son of three boys in Mountain View, the seat of Stone County in northern Arkansas. His brothers were Luther (the eldest), and Howard (the youngest). The family moved the boys to Little Rock in 1914, where Powell sang in church choirs and with local orchestras, and started his own band. Powell attended the former Little Rock College, before he started his entertainment career as a singer with the Royal Peacock Band which toured throughout the Midwest.

During this time, he married Mildred Maund, a model, but she found being married to an entertainer not to her liking. After a final trip to Cuba together, Mildred moved to Hemphill, Texas, and the couple divorced in 1932. Later, Powell joined the Charlie Davis Orchestra, based in Indianapolis. He recorded a number of records with Davis and on his own, for the Vocalion label in the late 1920s.

Powell moved to Pittsburgh, where he found great local success as the Master of Ceremonies at the Enright Theater and the Stanley Theater.

In April 1930, Warner Bros. bought Brunswick Records, which at that time owned Vocalion. Warner Bros. was sufficiently impressed by Powell's singing and stage presence to offer him a film contract in 1932. He made his film debut as a singing bandleader in Blessed Event.[4]

He was borrowed by Fox Film to support Will Rogers in Too Busy to Work (1932). He was a boyish crooner, the sort of role he specialised in for the next few years. Back at Warners he supported George Arliss in The King's Vacation, then was in 42nd Street (both 1933), playing the love interest for Ruby Keeler. The film was a massive hit.

Warners got him to basically repeat the role in Gold Diggers of 1933 (1933), another big success. So too was Footlight Parade (1933), with Keeler and James Cagney.

Powell was upped to star for College Coach (1933), then went back to more ensemble pieces including 42nd Street, Convention City (both 1933), Wonder Bar, Twenty Million Sweethearts, and Dames (all 1934).[3]

Happiness Ahead was more of a star vehicle for Powell, as was Flirtation Walk (both 1934). He was top-billed in Gold Diggers of 1935 and Broadway Gondolier (both 1935), both with Joan Blondell. He supported Marion Davies in Page Miss Glory (1935), made for Cosmopolitan Pictures, a production company financed by Davies' lover William Randolph Hearst, who released through Warners.

Warners gave him a change of pace, casting him as Lysander in A Midsummer Night's Dream (1935).

More typical was Shipmates Forever (1935) with Keeler. 20th Century Fox borrowed him for Thanks a Million (1935); back at Warners, he did Colleen (1936) with Keeler and Blondell. Powell was reunited with Marion Davies in another for Cosmopolitan, Hearts Divided (1936), playing Napoleon's brother.

He made two films with Blondell, Stage Struck (1936) and Gold Diggers of 1937 (1937). 20th Century Fox then borrowed him again for On the Avenue (1937).

Back at Warners, he appeared in The Singing Marine, Varsity Show (both 1937), Hollywood Hotel, Cowboy from Brooklyn, Hard to Get, Going Places (all 1938), and Naughty but Nice (1939). Fed up with the repetitive nature of these roles, Powell left Warner Bros and went to work for Paramount Pictures.

At Paramount, he and Blondell were cast together again, in the drama I Want a Divorce (1940). Then Powell got a chance to appear in another non-musical, Christmas in July (1940), a screwball comedy which was the second feature directed by Preston Sturges.

Universal borrowed him to support Abbott and Costello in In the Navy (1941), one of the most popular films of 1941. At Paramount he had a cameo in Star Spangled Rhythm and co-starred with Mary Martin in Happy Go Lucky (both 1943). He supported Dorothy Lamour in Riding High (1943).

He was in a fantasy comedy directed by Ren�� Clair, It Happened Tomorrow then went over to MGM to appear opposite Lucille Ball in Meet the People (both 1944), which was a box office flop.

During this period, Powell starred in the musical programme Campana Serenade, which was broadcast on NBC radio (1942–1943) and CBS radio (1943–1944).

By 1944, Powell felt he was too old to play romantic leading men anymore,[citation needed] so he lobbied to play the lead in Double Indemnity. He lost out to Fred MacMurray, another Hollywood nice guy. MacMurray's success, however, fueled Powell's resolve to pursue projects with greater range.

Powell's career changed dramatically when he was cast in the first of a series of films noir, as private detective Philip Marlowe in Murder, My Sweet, directed by Edward Dmytryk at RKO. The film was a big hit, and Powell had successfully reinvented himself as a dramatic actor. He was the first actor to play Marlowe – by name – in motion pictures. (Hollywood had previously adapted some Marlowe novels, but with the lead character changed.) Later, Powell was the first actor to play Marlowe on radio, in 1944 and 1945, and on television, in a 1954 episode of Climax! Powell also played the slightly less hard-boiled detective Richard Rogue in the radio series Rogue's Gallery beginning in 1945.

In 1945, Dmytryk and Powell reteamed to make the film Cornered, a gripping, post-World War II thriller that helped define the film noir style.

For Columbia, he played a casino owner in Johnny O'Clock (1947) and made To the Ends of the Earth (1948). In 1948, he stepped out of the brutish type when he starred in Pitfall, a film noir in which a bored insurance company worker falls for an innocent but dangerous woman, played by Lizabeth Scott.

He broadened his range appearing in a Western, Station West (1948), and a French Foreign Legion tale, Rogues' Regiment (1949). He was a Mountie in Mrs. Mike (1950).

From 1949 to 1953, Powell played the lead role in the NBC radio theater production Richard Diamond, Private Detective. His character in the 30-minute weekly was a likable private detective with a quick wit. Many episodes ended with Detective Diamond having an excuse to sing a little song to his date, showcasing Powell's vocal abilities. Many of the episodes were written by Blake Edwards. When Richard Diamond came to television in 1957, the lead role was portrayed by David Janssen, who did no singing in the series. Prior to the Richard Diamond series, he starred in Rogue's Gallery. He played Richard Rogue, private detective. The Richard Diamond tongue-in-cheek persona developed in the Rogue series.

Powell took a break from tough-guy roles in The Reformer and the Redhead (1950), opposite wife June Allyson. Then it was back to tougher movies: Right Cross (1950), a boxing film, with Allyson; Cry Danger (1951), as an ex con; The Tall Target (1951), at MGM directed by Anthony Mann, playing a detective who tries to prevent the assassination of Abraham Lincoln.

He returned to comedy with You Never Can Tell (1951). He had a good role in MGM's popular melodrama, The Bad and the Beautiful (1952). His final film performance was in a romantic comedy Susan Slept Here (1954) for director Frank Tashlin.

Even when he appeared in lighter fare such as The Reformer and the Redhead and Susan Slept Here (1954), he never sang in his later roles. The latter, his final onscreen appearance in a feature film, did include a dance number with co-star Debbie Reynolds.

By this stage Powell had turned director. His feature debut was Split Second (1953) at RKO Pictures. He followed it with The Conqueror (1956), coproduced by Howard Hughes starring John Wayne as Genghis Khan. The exterior scenes were filmed in St. George, Utah, downwind of U.S. above-ground atomic tests. The cast and crew totaled 220, and of that number, 91 had developed some form of cancer by 1981, and 46 had died of cancer by then, including Powell and Wayne.

He directed Allyson opposite Jack Lemmon in You Can't Run Away from It (1956). Powell then made two war films at Fox with Robert Mitchum, The Enemy Below (1957) and The Hunters (1958).

In the 1950s, Powell was one of the founders of Four Star Television, along with Charles Boyer, David Niven, and Ida Lupino. He appeared in and supervised several shows for that company. Powell played the role of Willie Dante in Four Star Playhouse, in episodes entitled "Dante's Inferno" (1952), "The Squeeze" (1953), "The Hard Way" (1953), and "The House Always Wins" (1955). In 1961, Howard Duff, husband of Ida Lupino, assumed the Dante role in a short-lived NBC adventure series Dante, set at a San Francisco nightclub called "Dante's Inferno".

Powell guest-starred in numerous Four Star programs, including a 1958 appearance on the Duff-Lupino sitcom Mr. Adams and Eve. He appeared in 1961 on James Whitmore's legal drama The Law and Mr. Jones on ABC. In the episode "Everybody Versus Timmy Drayton", Powell played a colonel having problems with his son. Shortly before his death, Powell sang on camera for the final time in a guest-star appearance on Four Star's Ensign O'Toole, singing "The Song of the Marines", which he first sang in his 1937 film The Singing Marine. He hosted and occasionally starred in his Dick Powell's Zane Grey Theater on CBS from 1956–1961, and his final anthology series, The Dick Powell Show on NBC from 1961 through 1963; after his death, the series continued through the end of its second season (as The Dick Powell Theater), with guest hosts.

Powell was the son of Ewing Powell and Sallie Rowena Thompson.

He married three times:

Mildred Evelyn Maund (b. 1906, d. 1967). The couple married in 1925, and appear on the 1930 census in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, where Powell was working in a theater, and on a 1931-passenger list for the SS Oriente, returning from Havana, Cuba. They divorced in 1932, although Mildred retained her married name.

Joan Blondell (married September 19, 1936, divorced 1944). He adopted her son from a previous marriage, Norman Powell, who later became a television producer; the couple also had one child together, Ellen Powell.

June Allyson (August 19, 1945, until his death, January 2, 1963), with whom he had two children, Pamela (adopted) and Richard Powell, Jr.

Powell's ranch-style house was used for exterior filming on the ABC TV series, Hart to Hart. Powell was a friend of Hart to Hart actor Robert Wagner and producer Aaron Spelling. The estate, known as Amber Hills, is on 48 acres in the Mandeville Canyon section of Brentwood, Los Angeles.

Powell enjoyed general aviation as a private pilot.

On September 27, 1962, Powell acknowledged rumors that he was undergoing treatment for cancer. The disease was originally diagnosed as an allergy, with Powell first experiencing symptoms while traveling East to promote his program. Upon his return to California, Powell's personal physician conducted tests and found malignant tumors on his neck and chest.

The marker on Dick Powell's niche in Forest Lawn Memorial Park, Glendale, California incorrectly identifies his year of death as 1962. Powell died at the age of 58 on January 2, 1963. His body was cremated and his remains were interred in the Columbarium of Honor at Forest Lawn Memorial Park in Glendale, California. In a 2001 interview with Larry King, Powell's widow June Allyson stated that the cause of death was lung cancer due to his chain smoking.

It has been speculated that Powell developed cancer as a result of his participation in the film The Conqueror, which was filmed at St. George, Utah, near a site used by the U.S. military for nuclear testing. As well as Powell, who directed the film, about a third of the actors who participated in the film developed cancer, including John Wayne and Susan Hayward.

During the 15th Primetime Emmy Awards on May 26, 1963, the Television Academy presented a posthumous Television Academy Trustee Award to Dick Powell for his contributions to the industry. The award was accepted by two of his former partners in Four Star Television, Charles Boyer and David Niven.

Dick Powell has a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame at 6915 Hollywood Blvd.

#dick powell#classic hollywood#classic movie stars#golden age of hollywood#old hollywood#singer#1930s hollywood#1940s hollywood#1950s hollywood#hollywood legend

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

a tag game!

rules: tag 9 people you would like to know better/catch up with!

tagged by @iam93percentstardust ily

last song: two (instrumental) by sleeping at last (their instrumentals are my study music)

last movie: uhhhhf uck OH it was my spy (2019)

currently watching: skyblock randomizer challenge #4

currently reading: uhh. uhhhh. uhhhh. the american pageant by david m. kennedy and lizabeth cohen (it’s my apush textbook)

currently craving: idk uhhhh something salty maybe uhhhhh i do not know i hunger for nothing uhhhhhh oh a hug

tagging: @peachy-keener, @anthonydarling, @lovelyirony, @rhodee, @justsomeoneunordinary, @theavengays, @diazalex, @natasharxmanov, @ad1thi

#my spy fucking slapped y'all it didn't deserve the 44% it got on rotten tomatoes it was so enjoyable#is that nine. yes it is i can count#aven.txt#tag game

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

La América sombría de Samuel Fuller

Basta recordar sus películas, o echar un vistazo a una filmografía: ni Humphrey Bogart, Fred McMurray o Edward G. Robinson, ni John Garfield, Sterling Hayden o Paul Muni, ni Dana Andrews, Dick Powell o Burt Lancaster, ni George Raft, Orson Welles, Robert Mitchum o James Cagney, aunque sí –dentro del género, cada uno una vez, los dos últimos juntos en La casa de bambú (House of Bamboo, 1955)– Richard Widmark, Robert Ryan y Robert Stack, más un puñado de desconocidos, a veces ilustres, a veces realmente anónimos (como el excelente Frank Gerstle); tampoco, entre las mujeres, Gene Tierney , Lizabeth Scott , Ava Gardner, Joan Bennett, Rita Hayworth, Yvonne De Carlo o (salvo en un western que su intervención ayuda a teñir de "negro") Barbara Stanwyck honran con su presencia el cine de Sam Fuller, carente, además, de "vampiresas" y femmes fatales y traicioneras, salvo la Silvia Pinal de Arma de dos filos (Shark!, 1969); encontramos, en cambio, a las muy leales y francas Jean Peters –en Manos peligrosas (Pickup on South Street, 1953)–, Victoria Shaw –en The Crimson Kimono ("El kimono carmesí", 1959)–, Constance Towers –en Corredor sin retorno (Shock Corridor, 1963) y Una luz en el hampa (The Naked Kiss, 1964)–, o Kristy McNichol –en Perro blanco (White Dog, 1981)– , por poner algunos ejemplos ilustrativos.

Más que claramente adscribibles al género llamado, primero en Francia y luego en toda Europa, "negro" –que en América no existió nunca, salvo a posteriori: para críticos, cinéfilos y cineastas recientes, en todo caso posteriores a Fuller, y que se denomina, en francés, film noir–, lo que hay es bastantes películas de Fuller que en Variety –es decir, en Hollywood, en el seno de la industria– calificarían indistintamente de thriller o de "melodrama". En España, más que cine "negro", debiéramos considerarlas como muestras de cine "policial" o "criminal".

Sin bases literarias de los diversos subgéneros (mystery, hard-boiled, thriller, whodunit, chiller) que han solido alimentar este tipo de cine, ni referencias a los autores más o menos "clásicos" –Dashiell Hammett, James M. Cain, Horace McCoy, W.R. Burnett, Raymond Chandler, Bill S. Ballinger, Vera Caspary, Dorothy B. Hughes, "Geoffrey Homes" (Daniel Mainwaring), Jim Thompson, Patricia Highsmith, Ross Macdonald, Donald E. Westlake, Ed McBain, Richard Stark; sólo, muy tardíamente y "en Europa", ha adaptado al marginal David Goodis en Calle sin retorno (Sans espoir de retour, 1989)–; sin vocación o aspecto semidocumental –como tantas películas Warner de los años 30, o Fox de los 40, y sobre todo, entre estas últimas, las producidas por Louis de Rochemont– ni apoyo en sucesos reales-históricos o de "palpitante actualidad", como las diversas campañas contra el crimen organizado, la delincuencia juvenil, el narcotráfico–, carecen de la imaginería mítica que fundamenta el perenne atractivo del género, sobre todo para los europeos, y también –consecuentemente– de protagonistas carismáticos –detectives privados o policías ejemplares– o bigger than life –pintorescos y truculentos villanos, melómanos y megalómanos, crueles y omnipotentes–, todo lo cual es, en el fondo, bastante lógico, ya que en las obras completas de Fuller no abundan los héroes ni los antihéroes, sino que predominan la ambigüedad de las "medias tintas" y los comportamientos contradictorios de la esquizofrenia latente o rampante.

La ausencia casi total de estrellas características del género –junto a la ocasional aparición de sus más destacados secundarios– no puede atribuirse meramente a la falta de presupuesto, cuya insuficiencia se ve siempre con creces compensada a fuerza de imaginación y astuta economía narrativa –es decir, como en la serie B, pero sin que por ello las películas de Fuller dejen de ser obras netamente personales e identificables a simple vista como exclusivamente "suyas", y por tanto ajenas a toda idea de "serie" o de sistema de fabricación–, ya que a menudo empleaba a actores de no menor cotización, pero desusados o sorprendentes en el género.

De hecho, son el propio individualismo y la muy deliberadamente buscada originalidad de tono, planteamiento y estilo que caracterizan el cine independiente de Fuller lo que hace sumamente dudosa y conflictiva la clasificación de su obra por "géneros". Como luego el de Godard, el cine de Fuller constituye "un género en sí mismo", que aprovecha algunos aspectos de los modelos o patrones genéricos preexistentes y establecidos, pero sirviéndose de ellos como de un repertorio o un muestrario, y de un modo tan libre, anticonvencional, personal y antiacadémico que, por ejemplo, sus westerns son todos ellos "aberrantes", sus películas de guerra poco tienen que ver con las habituales, y su cine "negro" en nada se parece a El halcón maltés (The Maltese Falcon, 1941), El sueño eterno (The Big Sleep, 1946), Retorno al pasado (Out of the Past, 1947) o La jungla del asfalto (The Asphalt Jungle, 1950), y guarda más relación, en todo caso, con "anomalías" como Persecución en la noche (Ride the Pink Horse, 1947), La dama de Shanghai (The Lady from Shanghai, 1947), Almas desnudas (The Reckless Moment, 1949) o Sed de mal (Touch of Evil, 1958)... o las prefigura, como A quemarropa (Point Blank, 1967) de John Boorman, para mí claramente tributaria de Underworld USA ("Bajos fondos USA, 1960), hábilmente cruzada con Código del hampa (The Killers, 1964) de Don Siegel, o, más todavía, Manhattan Sur (The Year of the Dragon, 1985) de Michael Cimino, que debe mucho también a La casa de bambú, y no poco a The Crimson Kimono.

Cuando se habla de cine "negro", los ejemplos que vienen primero a la memoria son varios interpretados por Bogart –aunque no suelan recordarse películas tan inolvidables como The Roaring Twenties ("Los rugientes años veinte", 1939) y El último refugio (High Sierra, 1941) de Raoul Walsh, The Big Shot ("El gran disparo", 1942) de Lewis B. Seiler o Callejón sin salida (Dead Reckoning, 1947) de John Cromwell–, fundamentalmente la inaugural El halcón maltés (1941) de John Huston y la paradigmática El sueño eterno (1946), que hace que figure en todas las antologías un nombre tan alejado habitualmente del género –a pesar de la precursora Scarface, el terror del hampa (Scarface, Shame of a Nation, 1932)– como el de Howard Hawks. A continuación, se van añadiendo obras de Robert Siodmak, Billy Wilder, Fritz Lang, Otto Preminger, Raoul Walsh, Jules Dassin, John Berry, Anatole Litvak... hasta llegar a cineastas exóticos como Jacques Tourneur, John Brahm, André De Toth, Joseph H. Lewis, Phil Karlson o Edgar G. Ulmer, pero muy raramente se piensa en Fuller.

Por eso no acaba de ser escandaloso, aunque a mí me resulte un poco extraño, que el nombre de Fuller ni siquiera aparezca en el índice onomástico de una colección de ensayos tan interesante como el recientísimo "The Movie Book of Film Noir" (editado por Ian Cameron, Studio Vista, Londres, 1992), obra, en general, de críticos admiradores de este cineasta, y que no se estudie en sus páginas ninguna de sus películas (sólo se cita, una vez y de pasada, Pickup on South Street), pese a que veinte años antes Colin McArthur, además de pedirle prestado el no muy original título de "Underworld USA" (Cinema One Series, Secker & Warburg, Londres, 1972), le dedicase un interesante capítulo. Pero estamos acostumbrados a su ausencia, como a que todavía haya diccionarios que le ignoran, y encima durante los últimos años ha caído un tanto en el olvido.

Ahora bien, y en buena medida porque Fuller es un cineasta "disidente" y rebelde frente a las normas –todas, desde las narrativas a las estéticas, desde las que rigen los géneros a las que determinan los raccords, desde las que conforman lo que hoy se llamaría politically correct y antes "progresista" hasta las que definen en cada momento lo que la sociedad entiende por "buen gusto" y está dispuesta a aceptar de buen grado–, una porción considerable de su filmografía, cualesquiera que sean la época en que acaecen los hechos narrados y la fecha de realización de la película, puede asimilarse a la "crónica negra" de la sociedad que describe.

Esta propensión no es rara: para comprenderla, basta recordar que Fuller se formó como reportero "de sucesos", aunque conviene no olvidar que antes de convertirse en guionista y director de cine escribió novelas "policiacas", lo que a su vez explica la facilidad con que sus películas pronto abandonan el realismo de partida –el trampolín de la normalidad– para adentrarse decidida y osadamente en la más pura y descabellada ficción.

El más superficial análisis revela que Fuller antepone la eficacia dramática y "su propia fruición como narrador" a toda idea de "verosimilitud" o de "probabilidad estadística", que presta más atención a la lógica interna de los personajes y las situaciones en que se ven envueltos que a cualquier pauta impuesta desde el exterior, provenga de la tradición o de una moda. Escuchar a Fuller contar o describir una película, tanto ya realizada como sólo escrita o meramente imaginada, o leer las entrevistas largas –en las que se dedica a hacer eso en cuanto le dejan sus interlocutores– demuestra el carácter eminentemente visual y efectista de su inventiva, y lleva a sospechar que se le ocurren las ideas a un ritmo muy superior al que es capaz de contarlas, tanto oralmente como, más tarde, en la pantalla, impresión que sus películas menos conseguidas confirman, en especial algunas de las últimas basadas en sus propias novelas.

El duro aprendizaje periodístico de Fuller es uno de los factores "estilísticos" que fundamentan su forma de entender el cine. Por eso busca el dramatismo, la espectacularidad y el impacto, que le tientan hasta bordear el sensacionalismo. De ahí también su inveterada afición a la polémica y el debate. Si coquetea en ocasiones con lo que peyorativamente suele llamarse "cine de tesis" –aunque al menos las suyas suelen ser propias y originales, cuando no estrafalarias y paradójicas, y siempre se sitúan provocativamente "a contrapelo" de lo que "se lleva" o está "bien visto", lo que las hace especialmente irritantes para los dogmáticos y los propensos a dejarse llevar por la corriente– es porque tiende a introducir comentarios "editoriales", para colmo de una heterodoxia que ningún director de periódico le permitiría, por temor a perder lectores o crearse conflictos. De ahí le viene también, probablemente, una desmedida afición a abordar "grandes temas" amplios y generales, preferentemente ilustrados –casi simbólicamente– mediante pequeñas anécdotas, que se van complicando y entremezclando hasta acabar por resultar de un barroquismo notable.

Es el lado "parabólico", de morality play, con claros antecedentes en el "Moby Dick" de Herman Melville, y en la Biblia, que han comentado a menudo sus exégetas –para ser preciso, sólo los anglosajones, de los cuales los mejores son todos ingleses, y además discípulos más o menos remotos del prestigioso y polémico crítico literario F. R. Leavis–, y que puede chocar con su modestia económica.

Su permanente conflicto con la estrechez de recursos materiales y temporales que impone en Hollywood el afán de independencia impulsa a Fuller, para acercarse a sus ambiciosas metas, a jugar con la confrontación y el contraste; cuando dos personajes se enfrentan, asistimos gráficamente al choque de dos posturas, dos grupos de interés, dos ideologías, que no necesitan de grandes discursos para exponer sus puntos de vista. Se trata, casi siempre, de una lucha a muerte entre organizaciones o individuos de intereses contrapuestos o rivales, pero que se sirven de medios y "métodos" muy semejantes; esta similitud facilita que Fuller cultive la figura dramática más cargada de ambivalencia: la "infiltración" de un grupo por un solitario, cuyo afán de venganza personal es aprovechado por la banda rival –o la policía– para destruir desde dentro la organización enemiga "penetrada". No es raro que un personaje de "infiltrado" atraiga a Fuller, ya que suele ser, por lo menos, un disidente, y además puede convertirse en un traidor, un agente involuntario o un espía a la fuerza. Hay ejemplos de ello en sus westerns –como Bob Ford en Balas vengadoras (I Shot Jesse James, 1949), el sudista renegado (Rod Steiger) y el indio que ha sido scout o guía de la caballería (Jay C. Flippen) en Yuma (Run of the Arrow, 1957), el celoso Dean Jagger de Forty Guns ("Cuarenta pistolas", 1957)–, pero abundan , sobre todo, en las películas más próximas al cine "negro", desde Manos peligrosas y La casa de bambú hasta Underworld USA, sin olvidar Corredor sin retorno y Una luz en el hampa; incluso en películas de guerra –al menos como sospecha, en Casco de acero (The Steel Helmet, 1951)– o a mitad de camino entre ambos géneros –como Verboten! ("¡Prohibido!", 1958)– se dan este tipo de situaciones o de duplicidades de los personajes.

Nada debe la preeminencia de este tema en Manos peligrosas –Richard Widmark, Jean Peters y Thelma Ritter, los tres protagonistas, son traidores o delatores–, por tanto, a la histeria McCarthista con la que injustamente se le ha relacionado; igualmente, cuando se habla de maniqueísmo a propósito de Fuller se está recurriendo a un insulto que no resiste el más somero análisis de sus películas. Como corolario, puede observarse que, aunque su mejor y más activa etapa creadora coincida –como en el cine americano en general– con la doble presidencia de Eisenhower, no hay en su cine el menor asomo de apología del American Way of Life entonces triunfante e imperante ya en medio mundo, que tan corrosivamente diseccionaron los europeos ilustrados instalados en Hollywood –Fritz Lang, Otto Preminger, Douglas Sirk–, pero que el grueso del cine americano se limitaba a ilustrar y propagar, con excepciones críticas –los melodramas de Nicholas Ray o Vincente Minnelli, por ejemplo–, pero que incluso buena parte del cine "policiaco", sobre todo el que apoya la lucha contra el crimen organizado o la corrupción local, apoyaba implícitamente.

Aunque las imágenes de Fuller son tan llamativas y chocantes que se piensa en él, sobre todo, como un realizador –cuando es, con Nicholas Ray, Joseph L. Mankiewicz y Orson Welles, uno de los pocos cineastas americanos de su generación con "conciencia de autor", totalmente responsable de sus obras–, conviene, insisto, tener siempre presente que Fuller es, ante todo, un escritor, un periodista y un novelista. Eso explica su afición al negro sobre blanco de la letra impresa en las páginas de un libro o de un diario, con lo que ello implica, a la vez, de precisión y de esquematismo –o de predisposición a cargar las tintas–, pero también de afán de abarcar el máximo territorio y de investigar a fondo en sus rincones y recovecos, de mostrar luces y sombras, de ir más allá de la apariencia y de las contradicciones y paradojas, de bucear en la ambigüedad aun a riesgo de no siempre conseguir escapar de ella.

Fuller fue también, antes de llegar a reportero, vendedor callejero de periódicos, y sabe por experiencia práctica la importancia y la eficacia de un gran titular llamativo, de una frase chocante, de una foto elocuente, de un recuadro de opinión en primera plana. Se podría pensar que, además de todo eso, y aunque no he encontrado el menor rastro de semejante actividad, también cultivó el cartelismo publicitario, o el diseño de portadas de novelas de bolsillo, ya que muchos de sus planos tienen la gráfica y algo tosca expresividad de un póster –político o comercial– o de la cubierta de una edición barata, y otros son como pancartas, u octavillas lanzadas a la sala de cine, o como grandes murales, vallas o dazibaos ofrecidos a la mirada del espectador. También debió frecuentar durante algún tiempo las ondas, a la vista de su interés por el sonido y la perspectiva acústica, su empleo de la música y su afición a interpelar directamente al espectador, mediante una voz en off –o un letrero– que le interroga y que a menudo reemplaza el clásico "The End". El colmo de esta tendencia a implicar al público en sus películas lo ilustra la idea delirante de propugnar que en las películas de guerra silbaran las balas sobre las cabezas de los espectadores, a ser posible –sospecho– con munición real.

Precisamente por no ser ni mitificador, ni desesperado, ni romántico, ni documental, ni denunciador, ni ejemplarizante, el cine que –con reservas, aunque no sin cierto fundamento– podríamos calificar de "negro" dentro de la obra de Fuller es mucho más sombrío y más tajante, más crítico e inconformista, menos engañosamente esperanzador que ningún otro, es decir, si se quiere, más "negro" todavía.

Lo que, mediante el relato de una historia particular compleja y dinámica, Fuller describe –como "de pasada", sin anunciarlo– es precisamente el rostro "normal" –cotidiano, ordinario, oficioso, apenas sumergido, funcional, rutinario e insensible– del hampa y de la corrupción.

Y tanto la colectiva –el pueblo fronterizo de Una luz en el hampa, la gran ciudad que alimenta la crónica del diario The Globe en Park Row ("Park Row", 1952), los Estados Unidos representados en un microcosmos que no es ya una diligencia, un hotel, un barco o un avión, sino el manicomio de Corredor sin retorno– como la individual –el pervertido e hipócrita prohombre-mecenas-benefactor de Una luz en el hampa, el periodista que se hace pasar por loco en Corredor sin retorno meramente con el propósito de ganar el codiciado premio Pulitzer–; la lógica implacable de la actuación de las organizaciones criminales –la mafia de Underworld USA, la banda-patrulla de ejército de ocupación que opera en el Japón de postguerra retratado en La casa de bambú, el círculo vicioso de espionaje-delación, fundamentado en la traición obtenida mediante soborno o chantaje, de Manos peligrosas– o policiales; los conflictos raciales y sociales que permanecen latentes en el gran melting pot integrador que es –o debiera ser– América para Fuller: véase, en particular, The Crimson Kimono, aunque es una obsesión omnipresente, desde The Baron of Arizona ("El Barón de Arizona", 1950) a Uno Rojo, división de choque (The Big Red One, 1980) y Perro blanco, pasando por Yuma, China Gate ("La Puerta de China", 1957) o Corredor sin retorno.

Como el no muy apreciado novelista Ross Macdonald –que algún día será revalorizado, tras Hammett y Chandler, y reconocido a su lado como uno de los grandes maestros literarios y éticos del género–, Fuller parece haber comprendido instintivamente que la mejor forma de representar el mundo contemporáneo en tiempos de paz consiste en tratar de describir el permanente y ambiguo enfrentamiento entre las fuerzas de la ley y las del hampa, combate no siempre violento, a veces subterráneo y hasta secreto, en el que ambas organizaciones complementarias bordeaban a menudo la ilegalidad y se servían de medios, en última instancia, no excesivamente distintos.

También comprendió pronto que el empeño del artista –escritor o cineasta, para el caso, daba igual– para abrirse camino entre la maraña de intrigas, relaciones, intereses, sociedades instrumentales y personas "usadas" por unos y otros sin demasiados escrúpulos y en muchas ocasiones a la fuerza –bajo presión o amenaza, con promesas de inmunidad o perdón, con recompensas u ofertas de protección– era, en gran medida, paralelo al trabajo de investigación que tenía que llevar a cabo un detective o un periodista, por lo que tales personajes y su forma de operar representaban un modelo válido para la conducción del relato y para transmitir dramáticamente, y a ser posible con amenidad, al espectador su visión del caos y la corrupción reinantes.

Esto es lo que hace, más allá de discrepancias formales y de su muy superior dureza, que el de Fuller esté claramente emparentado con el llamado "cine negro", siempre que su acción sucede hoy en día y mientras no se trate de un relato bélico.

Y conviene observar que esto ocurre, sobre todo, cuando el escenario son los Estados Unidos: de películas situadas en México (como Arma de dos filos) o, más todavía, en Europa, como la francesa Ladrones en la noche (Les voleurs de la nuit, 1983) o la portuguesa Calle sin retorno, no cabría decir lo mismo, a pesar de que la primera tenga concomitancias –el tipo de mujer que encama Silvia Pinal– con los ejemplos más "míticos" del género y sus diálogos evoquen los de otros thrillers "exóticos", como Una aventurera en Macao (Macao, 1952) de Josef von Sternberg, o las novelas de Charles Williams, de que tiendan a presentar personajes de americanos exiliados, y de que la tercera, producida por el realizador francés Jacques Bral –autor de Extérieur nuit y Polar–, adapte la novela "negra" homónima del escritor norteamericano David Goodis.

Esto indica que no se trata, pues, por parte de Fuller, de una opción formal, ni de aprovechar los rasgos convencionales que caracterizan al género como un envoltorio más o menos "atractivo" o comercial, sino de una concomitancia más radical, interior y esencial, basada en una visión crítica de la realidad moral –más que social– de su país.

Incluso creo significativo que Ladrones en la noche, que podría considerarse una versión actualizada de la historia contada por Fritz Lang en Sólo se vive una vez (You Only Live Once, 1937) y Nicholas Ray en They Live By Night ("Ellos viven de noche", 1948), se parezca mucho menos a Bonnie y Clyde (Bonnie and Clyde, 1967) de Arthur Penn o Thieves Like Us ("Ladrones como nosotros", 1974) de Robert Altman que a otras películas sobre jóvenes desarraigados en París que viven y mueren al borde de la delincuencia, pero que nada tienen en común con el cine "negro" de ningún continente ni con su imaginería clásica, El diablo probablemente (Le Diable probablement, 1977) y El dinero (L'argent, 1982) de Robert Bresson, mientras que Calle sin retorno se convierte en una visión abstracta, fragmentaria, heterogénea y alucinada, más cercana a una pesadilla que a cualquier enfoque de la realidad, por estilizado o distorsionado que pueda ser, y por tanto más emparentada –lógicamente– con Muerte de un pichón (Kressin und die tote Taube in der Beethovenstrasse, 1972) del propio Fuller que con muestras del género perfectamente aclimatadas al continente europeo como El silencio de un hombre (Le samouraï, 1967) o El círculo rojo (Le cercle rouge, 1970), personalísimas obras de Jean-Pierre Melville o con las películas más logradas de José Giovanni o Claude Sautet. De hecho, es el desarraigo involuntario lo que, al convertir en "apátridas" las últimas incursiones más o menos "negras" de Fuller, privándolas de sustento en la realidad, aunque fuera como mero trampolín para su fantasía, las aproxima a una serie de convenciones que le son ajenas y hace que no sean tan "negras" como sus películas americanas más alejadas, en principio, del género, como Park Row.

Miguel Marías

Revista “Nosferatu” nº 12, abril-1993

1 note

·

View note

Photo

via @jmjafrx "We are excited to announce the publication of sx:archipelagos, issue #3, Slavery in the Machine. https://ift.tt/2LGrOZt Guest edited by me and edited by Kaiama Glover and Alex Gil, this is a labor of love and care that we hope shows how central Caribbean thought is to anything humanistic, anything digital. So much fantastic work here–share, read, comment! Dedicated to Linda Rodriguez, beautiful scholar and soul. Descanza en paz. Thank you Alex and Kaiama. This issue could not have happened without you. Pa’lante! Issue (3) | Slavery in the Machine | July 2019 We dedicate this issue to Linda Rodriguez, whose spirit now lights the way. Introduction The Caribbean Won’t Stand Still Kaiama L. Glover and Alex Gil We Are Deathless (Slavery in the Machine) Jessica Marie Johnson Essays The Slave-Machine: Slavery, Capitalism, and the “Proletariat” in The Black Jacobins and Capital Nick Nesbitt PDF Collaborating with Aponte: Digital Humanities, Art, and the Archive Linda M. Rodriguez and Ada Ferrer PDF Haiti @ the Digital Crossroads: Archiving Black Sovereignty Marlene L. Daut PDF Xroads Praxis: Black Diasporic Technologies for Remaking the New World Jessica Marie Johnson PDF .break .dance Marisa Parham Digital Projects Early Caribbean Digital Archive Elizabeth Maddock Dillonand Nicole Aljoe Read our exchange | Visit the Project Site The Caribbean Digital & Peer Review: A Musical Passage Hypothesis Laurent Dubois, David Kirkland Garner and Mary Caton Lingold PDF Breaking, Dancing, Making in the Machine: Notes on “.break .dance” Marisa Parham Digital Project Reviews Review of Puerto Rico Syllabus: Essential Tools for Critical Thinking about the Puerto Rican Debt Crisis Lizabeth Paravisini-Gebert PDF sx archipelagos is a born-digital articulation of the Small Axe Project. It is a peer-reviewed publication platform devoted to creative exploration, debate, and critical thinking about and through digital practices in contemporary scholarly and artistic work in and on the Caribbean. https://ift.tt/2LGrOZt" https://ift.tt/32XLVIu Follow #ADPhD on IG: @afrxdiasporaphd

1 note

·

View note

Text

Out Now! Slavery in the Machine, a special issue of #sxarchipelagos

We are excited to announce the publication of sx:archipelagos, issue #3, Slavery in the Machine!

Figure 3. Vèvè of Papa Legba

We are excited to announce the publication of sx:archipelagos, issue #3, Slavery in the Machine.

Guest edited by me and edited by Kaiama Glover and Alex Gil, this is a labor of love and care that we hope shows how central Caribbean thought is to anything humanistic, anything digital. So much fantastic work here–share, read, comment!

Dedicated to Linda Rodriguez, beautiful scholar and soul. Descanza en paz.

Thank you Alex and Kaiama. This issue could not have happened without you. Pa’lante!

Issue (3) | Slavery in the Machine | July 2019

We dedicate this issue to Linda Rodriguez, whose spirit now lights the way.

Introduction

The Caribbean Won’t Stand Still Kaiama L. Glover and Alex Gil

We Are Deathless (Slavery in the Machine) Jessica Marie Johnson

Essays

The Slave-Machine: Slavery, Capitalism, and the “Proletariat” in The Black Jacobins and Capital Nick Nesbitt

PDF

Collaborating with Aponte: Digital Humanities, Art, and the Archive Linda M. Rodriguez and Ada Ferrer

PDF

Haiti @ the Digital Crossroads: Archiving Black Sovereignty Marlene L. Daut

PDF

Xroads Praxis: Black Diasporic Technologies for Remaking the New World Jessica Marie Johnson

PDF

.break .dance Marisa Parham

Digital Projects

Early Caribbean Digital Archive Elizabeth Maddock Dillonand Nicole Aljoe Read our exchange | Visit the Project Site

The Caribbean Digital & Peer Review: A Musical Passage Hypothesis Laurent Dubois, David Kirkland Garner and Mary Caton Lingold

PDF

Breaking, Dancing, Making in the Machine: Notes on “.break .dance” Marisa Parham

Digital Project Reviews

Review of Puerto Rico Syllabus: Essential Tools for Critical Thinking about the Puerto Rican Debt Crisis Lizabeth Paravisini-Gebert

PDF

sx archipelagos is a born-digital articulation of the Small Axe Project. It is a peer-reviewed publication platform devoted to creative exploration, debate, and critical thinking about and through digital practices in contemporary scholarly and artistic work in and on the Caribbean. http://smallaxe.net/sxarchipelagos/

Suomi satellite images of Puerto Rico on 24 July 2017 and 24 September 2017. Image credit\: NOAA National Environmental Satellite, Data, and Information Service (NESDIS

Read the post: https://ift.tt/2LVi1zh

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

“The Democrats shunned social-welfare proposals and pinned their economic faith on competition—on the “man on the make,” as [Woodrow] Wilson put it. The keynote of Wilson’s compaign was not regulation but fragmentation of the big industrial combines, chiefly by means of vigorous enforcement of the antitrust laws.”

The American Pagent, Twelth Edition, 2002. David M. Kennedy, Lizabeth Cohen, Thomas A. Bailey

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Fall in Love with Van Heflin: A Noir Double Feature by Kimberly Lindbergs

Today Van Heflin is rarely mentioned in the same breath as his high-profile costars—which included Judy Garland, Gene Kelly, Lana Turner, Gary Cooper, Ginger Rogers, Charlton Heston and Rita Hayworth—but during his lifetime, he was often referred to as one of the best actors of his generation. Heflin was a natural performer with uncommon talent who couldn’t be easily pigeonholed. He played heroic cowboys and philosophically minded doctors, as well as ruthless criminals and psychotic cops with equal finesse. While many of his contemporaries were lauded for their ham-fisted theatrics combined with an intense desire to be liked, Heflin often bucked convention. As a result, he can seem strangely aloof and out of place in 1940s Hollywood movies, but his inward-looking performances typically crackled with energy and his everyman disposition comes across as astonishingly modern today.

If you prefer your leading men to be conventionally handsome and “by-the numbers” actors, then Heflin, with his unruly red hair and restless protruding eyes, probably won’t appeal. He doesn’t possess Cary Grant’s charm or Humphrey Bogart’s swagger. Only one book has been written about the man and his lowkey lifestyle did not generate a lot of juicy gossip. Instead, Heflin is one of the earliest examples of a real “actor’s actor,” who won an Oscar for his performance in JOHNNY EAGER (’41) and has two stars on the Hollywood Walk of Fame (one for his film acting and the other for television).

To understand Heflin’s appeal, a good place to start is with two exceptional film noirs streaming on FilmStruck: THE STRANGE LOVE OF MARTHA IVERS (’46) and POSSESSED (’47). In both films, Heflin plays atypical romantic protagonists vigorously pursued by powerhouse leading ladies who risk everything to win his affection and respect.

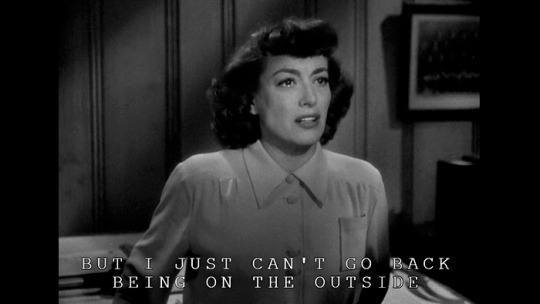

In THE STRANGE LOVE OF MARTHA IVERS, Heflin plays Sam Masterson, a professional gambler who returns to his birthplace and quickly finds himself embroiled in a provincial mystery and complex love triangle involving his childhood pals (Barbara Stanwyck and Kirk Douglas) and an enigmatic femme fatale (Lizabeth Scott). Combining elements of film noir with classic Gothic romances, this unusual Hollywood production is a relentlessly bleak and unforgiving movie. Before the credits roll, two people will be dead and an entire town will have felt the consequences. Heflin is exceptional as the world-weary Masterson compelled to reassess the past while being forced to choose between two beautiful but deeply troubled women. If there was ever a noir that perfectly embodied Thomas Wolfe’s poignant lament that “you can’t go home again,” THE STRANGE LOVE OF MARTHA IVERS might be it.

In POSSESSED, Heflin is David Sutton, a self-centered architect who becomes an object of obsession for Louise Howell (Joan Crawford). After the pair’s romantic dalliance comes to a bitter end and David finds another lover (Geraldine Brooks), Louise begins to lose her grip on reality and eventually suffers a mental breakdown that takes a particularly dire turn. Heflin is not given a lot to do in POSSESSED, but his natural charisma and lowkey acting style makes him an interesting costar for the highly-strung Crawford who was too often paired up with less compelling leading men. Heflin and Crawford make a fascinating match, so it is unfortunate that the film doesn’t spend more time building up their romance instead of focusing on the unfortunate aftermath of their sizzling affair. Despite my minor complaint, this is terrific slow burn noir with a fascinating and melancholy mystery at its shadow strewn center.

#FilmStruck#Van Heflin#film noir#The Strange Love of Martha Ivers#Possessed#Barbara Stanwyck#Joan Crawford#StreamLine Blog#Kimberly Lindbergs

41 notes

·

View notes