#like my cousin deadass talks about how the fact that people have smartphones and shit is somehow a tradeoff for increasing inability to

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Link

The right has been trying to sell Americans on consumption-based standards of freedom for years. Indeed, the CEA’s report on the baleful impact of socialism makes much more sense when one remembers that the current head of the agency is Kevin Hassett, a longtime fixture at the American Enterprise Institute, one of the foremost think tanks of the American conservative movement. (Hassett’s also the coauthor, with rabid supply-sider James Glassman, of one of the most ridiculous books of all time, 1999’s Dow 36,000.) This is the level of persuasion one expects from a person whose career has largely been devoted to persuading rich people to subsidize the production of dubious research praising the system that allowed them to get rich.

These think tanks specialize in that sort of “me or your lying eyes” approach to selling Americans on American-style capitalism (which you’d think, if it were working correctly, wouldn’t need so much marketing help). That’s why the Heritage Foundation, perhaps the most influential conservative think tank, periodically tells us that there’s no real poverty in America—or at least that while there might be some, it is, all in all, pretty pleasant poverty—in reports with titles like 2011’s “Air Conditioning, Cable TV, and an Xbox: What is Poverty in the United States Today?”

…All of these reports—and scores more pieces of commentary making the exact same arguments and citing the exact same figures—were authored or co-authored by Robert Rector, who has been shaping conservative arguments on poverty since joining the Heritage Foundation in 1984. He’s been called the “intellectual god-father” of the 1996 Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act, also known as welfare reform. Considering his part in that triumph of bipartisanship, which really did, as Bill Clinton promised, “end welfare as we know it,” it’s clear why Rector is so invested in the argument that to be poor in twenty-first century America is a cakewalk—he’s responsible for creating a whole new population of poor people.

…The tendency for American capitalism to justify itself by the gadgets it is capable of making affordable is an old one. It was the basis of the notorious 1959 “kitchen debate” between Vice President Richard Nixon and Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev, which took place at an exhibition of American technological wizardry set up in the heart of Moscow. The American pavilion featured the latest in American time-saving household appliances, and the debate almost immediately took on a legendary character in the United States, where we told ourselves that Soviet citizens were entranced by our washing machines and Polaroid cameras. The Americans faked the automated kitchen, of course—there was a guy behind a two-way mirror making the proto-Roomba move and turning on the “automated” dishwasher, Joe Maxwell, one of the industrial designers responsible for the kitchen, told Gizmodo decades later—as part of the mission was to convince the Russians that things being marketed to middle-class Americans, including things that were years away from any sort of commercial viability, were commonplace in homes across the country. (The Soviet exhibition in the United States, meanwhile, featured a modest three-room apartment. And Sputnik.) While the Soviets were suitably impressed with the quality of our kitchen appliances, this message left in the exhibition’s visitors’ book seems pertinent: “A shortcoming: you show what you produce, but you do not show what you produce it with.”

At the time, the (real, non-automated) dishwashers would have been manufactured in the United States, to be sold to middle-class families to help wives more efficiently carry out their unpaid domestic labor while their husbands were at work manufacturing dishwashers. The government subsidized the construction and (for white families) debt-financed purchasing of large suburban homes so that there would be somewhere to put all the dishwashers—and so that the people who built homes would have enough homes to build to afford their own dishwashers and large suburban homes. This was called “capitalism.” (The Council of Economic Advisers report on socialism quotes the late economist Sherwin Rosen’s dismissive description of Sweden as a place where “a large fraction of women work in the public sector to take care of the children of other women who work in the public sector to care for the parents of the women who are looking after their children.” Just think of all the surplus labor going to waste caring for people instead of being expropriated by the owners of capital!)

Eventually, the sort of people who own household appliance companies saw the return on their investments begin to stall out, due to inflation and labor power, so that system was phased out in favor of one in which many people still got large, debt-financed homes, but there were fewer dishwasher manufacturing jobs. The dishwashers got a lot cheaper, though, to help the new arrangements seem more palatable.

Yet still, despite the dirt cheap vacuums and flat-screen TVs, something seems wrong. People keep complaining about “income inequality” and writing books about how grindingly difficult it is for an alarmingly large number of Americans to get by.

Conservatives seem to have noticed that their primary argument—why do you feel so poor when you have such a large TV?—has had trouble making inroads among people who actually experience life in the United States and who don’t work within the think tank–lobbying firm–Council of Economic Advisers circuit. They’ve noticed, too, that while TVs, for example, are quite cheap, things essential to live—and things essential to “get ahead” in the United States—are only becoming more expensive.

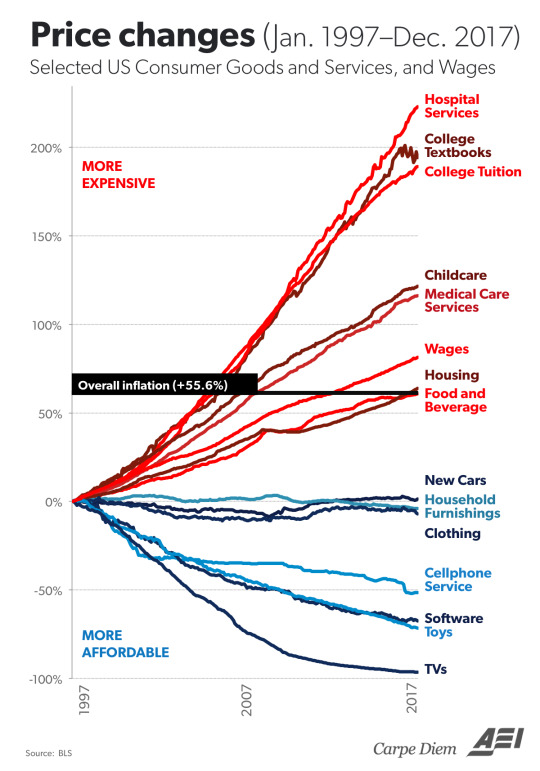

The American Enterprise Institute even produced a chart illustrating the problem. It shows the prices of things like new cars, clothing, toys, and TVs staying steady or dramatically falling relative to the inflation rate, while food, housing, child care, and—especially—medical care skyrocket in price. If you want an explanation of why non-wealthy Americans feel so stretched thin even in a time of supposed abundance, there it is. They can afford to get their kids toys but not bachelor’s degrees.

…Ex–Cold Warriors still fondly recall the kitchen debate. They still chuckle at the crummy cars and televisions the Soviet citizenry had to endure as Americans innovated cruise control and Betamax tapes. But during the periods when life was stable in the Soviet Union, its people were reasonably satisfied. The years since the end of Communism, on the other hand, have been devastating to a generation of Russians. As Masha Gessen wrote for The New York Review of Books in 2014:

In the seventeen years between 1992 and 2009, the Russian population declined by almost seven million people, or nearly 5 percent—a rate of loss unheard of in Europe since World War II. Moreover, much of this appears to be caused by rising mortality. By the mid-1990s, the average St. Petersburg man lived for seven fewer years than he did at the end of the Communist period; in Moscow, the dip was even greater, with death coming nearly eight years sooner.

Many of those deaths were violent or self-imposed. Deaths from injuries and poisoning are five times higher in Russia than in Western Europe. “We would never expect to find premature mortality on the Russian scale in a society with Russia’s present income and educational profiles and typically Western readings on trust, happiness, radius of voluntary association, and other factors adduced to represent social capital,” the economist Nicholas Eberstadt writes. In her review of scholars’ attempts to explain the story of the Russian death rate, Gessen wonders if the problem might be a sort of inherited cultural despair—whether “Russians are dying for lack of hope.”

Millions of former Soviet citizens now have access to the consumer bounty Americans lorded over them during the Cold War. It has not helped them adapt to life without a safety net. However often those notoriously unreliable Lada cars might have broken down, an inferior product line drove many fewer Russians to drink themselves to death than economic shock therapy did.

The year after Gessen wrote that piece, Princeton economists Anne Case and Angus Deaton published their paper showing that, after declining for decades, the mortality rate for middle-aged white Americans had been steadily climbing between 1999 and 2013. They updated their report in 2017, with data showing that non-college-educated white American men were increasingly dying of “diseases of despair,” meaning mainly drug and alcohol abuse and suicide.

The connecting thread in both the Russian and American cases seems to be decline in living standards—not absolute deprivation. By historical and international standards, there are much worse things to be than a member of the stagnant or declining middle class in America, or even post-Soviet Russia—nearly everyone we’re talking about probably has televisions and refrigerators among other cheaply produced pieces of gadgetry. But people seem to choose to obliterate themselves not when their current situation is dire, but when there is no apparent path to a better one.

Non-college-educated white American men are also, we’re told, President Trump’s base. His Council of Economic Advisers would like them to be grateful for all the room our large country has provided for them to park their trucks.

#*#essays#the worst is when regular people who aren't on the payroll or heritage or cap or w/e echo these same arguments bc they've remained part of#the dwindling population of socioeconomically secure individuals#like my cousin deadass talks about how the fact that people have smartphones and shit is somehow a tradeoff for increasing inability to#afford any actual essentials like housing or healthcare or w/e classic joe rogan fan#he also thinks most people in the US lived in farms until the 60s so idk

1 note

·

View note