#like its so deliberate and bizarre compared to every other character being mentioned its beyond comical

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

results are in for this one chatters

the other thing rgg fans dont like is andre richardson and on this day i would like to revoke my rgg fan license because i think its hilarious he's still here

#self reblog#snap chats#HELP#i was absent for two (2) days#anyway fair point here is how mine got no mention in the entirety of y8 bar quiz questions#but even that itself is really funny to me. like not a thought about him kiryu ? in the slightest ?#girl im gonna throw up laughing rgg tryna act like bro dont exist .....#too late mfer yall released like a dragon ishin now EVERYONE fixated on mine and what he up to#so funny how prior to y8 im pretty sure most people wouldve struggled to even remember richardson esp his name#like yeah sure mine dragged him off a building but bar that would anyone really note him#NOW hes like. a trigger word for mine enjoyers right that how you weed em out in a crowd#so funny ... its all so funny i really cant hate it in the slightest#again even though mine has absolutely no mention whatsoever in y8 I Repeat it is. so funny#like its so deliberate and bizarre compared to every other character being mentioned its beyond comical#alright ive got food to look at but not eat bye bye

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

crispy golden notes

1. weirdly interjects mentions of people eating/drinking and a list of what is being served. multiple times it feels superfluous especially because what’s described is usually just water, cheese, and bread. it doesnt add anything to the scenes beyond reminding the audience that the characters are mortal and need to eat sometimes (which can be a valuable sentiment to read about in the right context, but in most scenes is depicted in an alien and detached way, as if the audience is also not tacitly aware of the characters’ need to breathe).

2. girl do you have to hit a wordcount or what. is this a legal deposition? why do so many conversations have such thoroughly notated exchanges. again, there are times where you want to draw out a conversation in its entirety but so many points have been rehashed again and again in this book that they dont need a full callback every three chapters. you vowed when your brother was born that you would protect him no matter what. we get it. you dont have to reflect on the moment of his “perfect birth” every time the two of you have an argument, unless it is to display how disturbing your obsession with your brother is. like really, it’s fucking creepy.

3. siblings are, and have always been, written in the creepiest way imaginable. the fact that this book is dedicated to the author’s siblings is shocking considering the way sibling interactions are written is idyllic to the point of being unnerving. like, the hallmark channel would tell her to pipe down a bit. i thought the “my little moon” exchanges in war crimes were bad; the whole fucking family is “lady sun” “lady moon” “little moon” and “LITTLE LORD SUN”. and then the constant referring to anduin as the “little lion” and “now not-so-little lion” genuinely feels like some kind of a complex. i am still making my way through so we’ll see how it turns out, but i doubt a book written for the warcraft franchise will touch on the apparent obsession sylvanas has toward her younger brother and how she is later projecting it on anduin. it’s so glaringly apparent as the story continues that it makes me uncomfortable, as i feel it was entirely unintentional on the author’s part. maybe it’s because im not a parent and grew up in an age range too close to my other siblings to feel that sense of overprotectiveness so i’m interpreting it wrong. but others ive talked to also agree the chemistry is stilted or bordering on possessive.

at one point in the book sylvanas explicitly compares her attraction to nathanos as superseding the intimacy she has with her brother (lirath, by name). considering that nathanos is her romantic interest, this is a beyond bizarre comparison to make. sometimes i will say that my own younger brother is my favorite man in the world, but he is not on a rubric of comparison to a romantic or sexual partner. maybe this was her backwards way of saying sylvanas was discovering her love for nathanos was “more than a friend” or “different from a brother”, but “...She needed nathanos. ugly, blunt, sarcastic nathanos, who somehow understood her better than anyone, even lirath” is a weirdly tinged way to put it. again this is a more doylist read of “golden wtf are you writing” than a watsonian interpretation because, as i said, i dont think it was executed well enough for this nigh inc*stuous attachment issue to be written deliberately.

4. dovetailing on point 3 a little bit, several different characters have displayed genuine anger over kids growing up. like seething over lirath becoming a man, or that any of the windrunner siblings are no longer children, or that anduin is the aforementioned “no longer little lion” or whatever. i can understand the melancholy of the linear passage of time, and wistfulness of how “they grow up so fast”, but there are some points where sylvanas’ parents and sylvanas herself express near malice over the kids getting older, that they are no longer “perfect newborns”, and that they are starting to make their own decisions and have their own feelings and opinions and expect to be treated as adults. it happened enough times to stand out to me as being weird. like, you’re elves. you’ve had literally hundreds of years to adjust. get a grip sylv

5. i know he means “richness” in terms of familial stability but anduin crying to sylvanas that he “never had those riches” is fucking hilarious. you are LITERALLY KING my dude!!! battle of the bluebloods up in this LMFAO the girls are fighting!!!!!!! it’s just so fucking funny hearing sylvanas and anduin tearfully bickering over who had slightly less privilege: sylvanas, born into nobility to a tight-knit loving family separated by war and her teenage hijinks before being tortured beyond all recognition into a banshee? or anduin, forced to grow up too soon with a murdered mother and an absent, then psychologically-compromised father, but is also literally king? of a kingdom? AND theyre both white?

6. hard to figure out who this book is for. warcraft is rated T for teen but there is such palpable discrepancy between the events occurring and the tonality of them that is simultaneously immature and morbid. things that are supposed to be heartwrenching are just goofy and things that are supposed to be lighthearted and humorous are tepid and banal, inauthentic as canned laughs and formulaic like an afterschool special. well, at least sylvanas holding lirath’s dead body (spoilers) was actually sad, unlike anduin wrynn holding his own after the downright comical war crimes AU battle. foreshadowing is rough but keeps within its expiration date. however one periodically remembers (and the book refreshes this factoid in a quite hilarious fashion) that the backdrop of these stories of childhood love and loss is the tartarus-like prison in a sanctum of eternal damnation which gives the whole thing a dissonant atmosphere. and not in a clever ka applegate “kids crave these stories, actually” way but in a grimdark comic book “too far down the rabbit hole” mcu type way. this elf is telling stories about getting kicked out of a fancy party to a prince chained up in hell to persuade him to join the devil and it’s not supposed to be even a little bit funny? im not convinced this entire book isnt a bit

more as i continue. maybe

(second part here)

13 notes

·

View notes

Note

What was the honest reaction to Sonic 06 back in 2006?

It was a long time ago, so I can only really speak to my own perspective.

Sonic 2006 was the time that Sega’s marketing department really started cranking the hype train really, really hard. Sonic 2006 was announced as a fresh start. A soft reboot. Sonic Team said they were treating it like “the first Sonic game on the Sega Genesis.” You still had Tails, and Knuckles, and Shadow, but it was the start of a new era. A new type of Sonic the Hedgehog. More serious, more realistic, more “epic.”

At this point, there was no reason to necessarily distrust any of that. Yes, Sonic games had been slipping in quality, and yes, Sega was still more or less pretending that everything was “okay.” But that was always in the typical, “we’re trying to sell a video game and not go bankrupt” sense. This felt like a tacit acknowledgement that things weren’t so great and they were going to start over and refocus. Set things right.

Early gameplay footage looked rough. I distinctly remember a Gametrailers hands-on where they were demoing the Mach Speed Zone in Kingdom Valley, and the Sega representative was very clear and upfront that the game wasn’t done yet, and all of the empty space Sonic was running through would be filled in later. (It wasn’t.) There was also the typical debate over the TGS 2006 “Bringing it Home” playable demo, where people argued then, too, that the game wasn’t done yet, and not to judge things too harshly. The final version will be better.

The final version also wasn’t done yet. So, y’know.

I had effectively bought an Xbox 360 for this game. I was broke as per usual, but I’d gotten lucky and won a Gametrailers video competition, which landed me $1000 in Gamestop gift cards. I bought a PS2, a Nintendo DS, and an Xbox 360, plus more than a dozen games between the three platforms. I knew there would be more Xbox 360 games besides Sonic 2006, and I’d even originally wanted a 360 primarily for Elder Scrolls Oblivion, but the simple fact is that once the money was in my hands and I spent it, Sonic 2006 was the only actual Xbox 360 game I owned.

Or was going to own, anyway. I think I’d won the contest in September or October of 2006, when Sonic came out in November. So I bought the 360 a few weeks early with some original Xbox games, and spent the interim with Spider-man 2, Ninja Gaiden Black, and the copy of Halo 2 I borrowed from my cousin.

Sonic 2006 was the first game I’d ever pre-ordered. The second game, pre-ordered on the same day, was The Legend of Zelda: Twilight Princess for the Gamecube. I still have the tiny pre-order statue that came with Sonic. His gloves and socks, once white, have begun to yellow with age, and the skin tone on his face and body is turning an ashy gray.

Even 72 hours before launch, there was not a clear picture what Sonic 2006 actually was. Sega was deliberately obfuscating certain features; early in development they’d sworn up and down that there were only three playable characters in the game, something that blatantly wasn’t true. Perhaps it was miscommunication from Japan, but it meant they were now going out of their way to hide how many other playable characters were actually in the game. I naively distrusted most (if not all) professional reviewers back then, and the earliest scores for Sonic 2006 were all over the map.

As a Sonic fan, you kind of had to know how to read between the lines on the more negative reviews, because we were definitely in the era where it felt like critics were starting to dogpile on the Sonic franchise now that Sega was a third party developer. There weren’t a lot of professional reviews you could trust regarding Sonic games, or at least, that’s what it felt like. This was the rise of the podcast, and snarky hosts were taking whatever low hanging fruit they could get.

I remember waking up on launch day -- friends had gotten up early and picked theirs up in the morning, when I’d rolled out of bed somewhere closer to noon (or maybe even afternoon). I had plans to pick up my copy later that evening, after sunset. My friends did not sound happy, but again, there was always this vibe of “Wait and see.” They had only just started the game. First impressions were still too fresh to really call.

But I had this moment, this cold spot in the pit of my stomach, where I thought “Maybe I can cancel the pre-order and get Gears of War instead?” Reviews for Gears seemed pretty good. I’d probably be happy with it instead of Sonic.

I couldn’t let myself do that. I was a Sonic fan. This was the first big Sonic game of a new generation. A new start. I bought the console for this. First game I ever pre-ordered. The second Sonic game in the history of the franchise I’d bought on launch day. This was it. This was the event. No backing down. Besides, Sonic 2006 was a big 15th Anniversary celebration game. They wouldn’t make such a big deal about the anniversary without just cause, right? Sonic 2006 was going to be great. I just needed to calm down.

So we drove out to Gamestop -- and it was the sort of thing where I think we couldn’t do the pre-order at my local Gamestop for some reason, so this one was a town or two over. It was a journey. I was nervous the whole way there. Something told me I was making a mistake. But I had to do this.

I think it may have been starting to rain as we rolled up on the store. It was around 8pm, and people were starting to camp out on the sidewalk. Literally camp out, tents and all, because of the rain. Today was the launch date for Sonic 2006, but tomorrow was the launch of the Playstation 3. These guys were here for Gamestop’s “Midnight Madness” launch event. They were going to be some of the first to get a PS3. I was probably the last person to pick up a Sonic 2006 pre-order.

Sonic 2006 might have been the first Sonic game to ever make me angry. I’d had a lot of internet debates on how I felt about Sonic Adventure 2, but most of those amounted to splitting hairs about things that felt disappointing when compared to the original Sonic Adventure. I was not angry then, I was simply let down. I was similarly let down when I finally got a chance to play Sonic Heroes. But again, not angry. Baffled, maybe. A little sad. But not angry.

With Sonic 2006, I slammed head first in to all of my excitement and uncertainty at 200mph. This was a Sonic game unlike anything I’d ever played before, and in all of the worst possible ways. Enough has been said about the quality of the game that I don’t need to describe anything that’s wrong with it -- also because literally everything was wrong with it. Perhaps the first video game I’d ever played, ever, on any platform, that actually fought back against your efforts to play it. A disaster in every sense of the word. A broken nightmare. After finishing Sonic’s story, I was mad. How could they let this happen? What was wrong with them?

I was less angry after having finished Shadow’s story. Shadow had even buggier gameplay than Sonic, but it also felt more complex, more action-oriented. His story was better, too -- instead of the sappy Princess love story, Shadow’s story was about how the world was against him, and the crossroads that brought him to: rise above his past and strive to be a better person, or give in to the temptations of evil? It was still dumb as heck, but it was less dumb than Sonic’s story.

By the time the credits rolled, I had accepted the fact that this game was a mess. More of a mess than any Sonic game ever had been before. It was clearly a deeply unfinished game. Friends theorized maybe they could patch the game, because that was a thing games could get now. Sonic 2006 could still be saved. The PS3 version wouldn’t be out for another month, surely that means they’re working on a fix, right? Some were even theorizing over an achievement called “Nights of Kronos” -- it mentioned a “complete ending to the last hidden story.” Perhaps that meant there was going to be more? Maybe we got the bad ending, and a better, more finished ending was waiting for us on the disc somewhere?

There wasn’t. And no patch ever fixed the game. That was Sonic 2006 -- the kiss, the loading screens, the strange mannequin NPCs, the stiff controls, the glitchy physics, the empty overworlds, the bizarre dialog, the plotholes and time paradoxes, that’s just what the game was, and was always going to be, forever.

Before Sonic 2006, you could say that 3D Sonic games were bad, but there was always a place to defend them from. They had problems, but they were never irredeemable. Sonic Heroes may have had frustrating controls and repetitive level design, but it had great art direction, nice music, and fun concepts. They were always trying, dang it, and it was obvious to see that.

Sonic 2006 felt irredeemable. Offensively terrible. A failure on such a level that it was hard to comprehend. Beyond simply “a new low” for the franchise. This felt like rock bottom. It was the kind of bad that spread like a virus. Even good games, like Sonic 2 on the Sega Genesis, felt notably tarnished by the existence of Sonic 2006. It threatened to ruin the entire franchise by proximity alone. For some, it probably did. I definitely had a moment where I wondered if I would ever enjoy a Sonic game in the same way ever again. They were all tainted now. Infected by memories of Sonic 2006, the game that was supposed to save the franchise, but condemned it to the lowest pits of hell.

In isolation, that might have been the end for me. I might have continued to drift away, bit by bit, until I found greener hills outside of the Sonic franchise.

I’ve said this before, but what saved me was getting hired to write for TSSZ News. Now, suddenly, I was paid to play and write about Sonic games. It was a duty. And it helped that the first Sonic game I reviewed for TSSZ ended up being Sonic Unleashed, a game I continue to openly gush about to this day, more than a decade after its release.

But never forget that Sonic 2006 was such a disaster that it nearly made me give up Sonic the Hedgehog. It really was that bad.

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dumbo at 34

A review by Adam D. Jaspering

We remember things as we want to remember them. Memories distort perception and perception distorts reality. Childhood is especially remembered well. If not the entire childhood, elements. People romanticize memories from the feelings they evoke, and discard the reality.

The circus is a prime example. The circus was once a staple of American pleasure. It brought entertainment, excitement, and exotic animals to small towns across the US. In days before the internet, before TV, and before movies were mainstream, it was a necessity.

People remember the old-timey charm, the whimsical environments and otherworldly aura. Nobody wants to remember the adverse working conditions, the high rate of injury, or the gross abuse of animals. Nobody remembers the smell of port-a-potties or the heaps of animal manure. People remember the calliopes and cotton candy.

It’s quite appropriate Dumbo takes place at a circus. Everybody remembers the movie fondly, but nobody seems to acknowledge its flaws. It’s heralded uncontested as a Disney masterpiece despite a number of problematic issues.

For starters, the film is only 64 minutes in length. This includes the opening credits. From a logistical standpoint, one can understand the purpose. Disney Studios took a financial hit from Pinocchio and Fantasia. They needed something not only profitable, but cheap. The same way that a three-wheeled car saves money on tires.

The story of Dumbo is one of growth and confidence when faced with adversity and doubt. However, the plot is about a young elephant finding an act in a circus. Dumbo tries, and he fails. He tries again, he fails again. Finally, he tries and he succeeds. An entire plot thread seems missing from the film. Dumbo learning to fly (both literally and figuratively) should support a larger narrative.

There are no stakes for Dumbo. His failures don’t affect the circus’s income or popularity. Dumbo is ostracized, but still cared for as well as any other animal in the show. He is ridiculed, but still performs every night.

The movie ends before any growth or change is displayed by the secondary characters. Everybody likes Dumbo once he can fly, but do they like him, or do they like his profitability and popularity? If a lion with an extra long tail is born, will he be mocked until he earns respect too?

Everybody in the circus feels comfortable calling him “Dumbo” at the movie’s end. Canonically, his official name is Jumbo Jr, named so by his mother. Everybody calls him Dumbo, a deliberate insult. The name sticks, even for the viewing audience. Either Dumbo begrudgingly accepts this epithet, or reclaims it. Either way, at least his mother should refuse it.

Dumbo’s mother is Mrs Jumbo, a pariah and outcast among the other circus elephants. What causes this exclusion is never explained or hinted at. The other elephants are just jerks. She has no friends, no confidantes, and is apparently widowed; there is never a mention or allusion of a Mr Jumbo. She has nobody in her life. This is presumably why she is so desperate to become a mother at the movie’s inception.

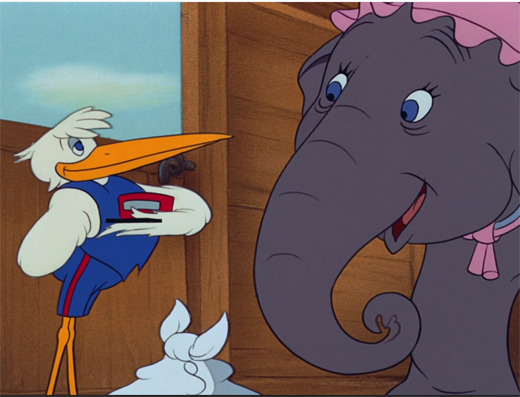

The film begins with a muster of storks delivering babies to various circus animals. It’s a cartoon staple and a very convenient workaround, explaining the miracle of a baby without the depiction of childbirth or implications of procreation. It also justifies how Dumbo is born despite there being no male elephants anywhere in the circus.

For whatever reason, these storks all deliver their parcels on the same night. All except for Mrs Jumbo’s coveted baby elephant. Baby Dumbo is delivered the following day. After seeing everyone else enjoying their children. After her hopes are dashed. There’s no explanation why the stork arrives late, well after the circus is dismantled and loaded aboard a train. Dumbo is delivered a day late for the sake of drama.

The train itself is almost a character itself. It has a name: Casey Jr. It has a face. It emotes. It speaks. But can he be rightfully called a character? Casey Jr doesn’t interact with other characters. He has no goals or desires besides acting and moving like an ordinary train. It’s an odd design choice, leaving Casey Jr halfway between being a robot and the pathetic fallacy.

Casey Jr is an interpretation of the famed children’s story, The Little Engine That Could. Casey Jr even uses the famous line, “I think I can, I think I can” as he climbs a hill. The story’s most famous interpretation was a 1930s picture book by Watty Piper (a name one could only have in the 1930s). The character and story itself belongs to the public domain.

It wouldn’t surprise me if somebody at Disney Studios tried and failed to make an animated short based on the story. As consolation, they retrofitted the character for a bit part in an unrelated, developing film. The cumbersomely named 'Little Engine That Could' was renamed ‘Casey Jr,’ and a new character is added to Dumbo's universe. A character Dumbo never meets or interacts with, and has no bearing on the plot. If nothing else, he adds five minutes to Dumbo’s anemic runtime.

Design is one of Dumbo’s weakest points. Human characters are hyper-stylized caricatures of actual people. Perhaps intentionally, so we empathize more with the comparatively realistic animals. But the animators went too far. The Ringmaster is so rotund, he seems inflated. The clowns have bizarre proportions which are somehow reigned in by their baggy costumes and floppy shoes. The rowdy child who assaults Dumbo looks more like a chimpanzee than a boy.

The character of Timothy Q Mouse is perplexing. Is he employed by the circus, or just a circus enthusiast who hangs around the fairgrounds after hours? What would a circus gain from hiring a mouse? Why does he dress like a bandleader? Does this imply an unseen mouse marching band? He never displays any musical ability. He’s there because the movie needs him to be there.

Being Dumbo’s sole friend is Timothy’s secondary purpose. His primary purpose is to outwardly verbalize the thoughts and emotions of Dumbo. Our protagonist is mute throughout the film and most characters avoid talking to Dumbo directly. Without Timothy, Dumbo would stare at camera sadly for the movie’s run.

The circus folk themselves are weird, and not just their physical attributes. The Ringmaster is a bombastic Italian man who, as Timothy describes, “never had an idea in his life.” He seems genuine, eager to entertain his audience with an entertaining and original show. His real malice is never workshopping ideas. He will not hesitate to endanger the lives of his employees or animals on his fanciful whims.

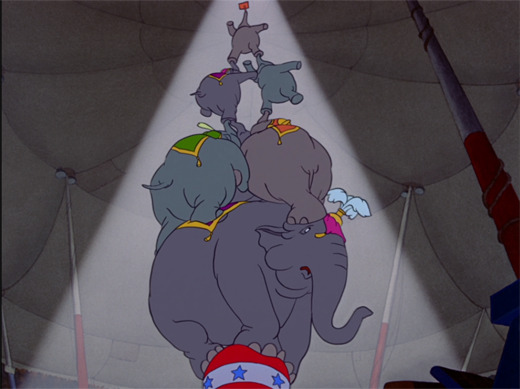

Can six full-grown elephants balance on a rubber ball? Who knows. Let’s put it in the show. Is it safe to have a baby elephant drop twenty feet into a washtub full of shaving cream? We’ll find out. Is it a good idea to start a fire underneath a canvas tent for the sake of a firefighter sketch? The audience likes it, so who cares? Go stand next to the fire, clowns.

There’s an old adage about doing anything for a laugh, but the clowns from Dumbo take it to a sociopathic extreme. The clowns develop an entire act around humiliating Dumbo. When the skit is a success, they drunkenly decide to put Dumbo in more humiliating situations and more precarious stunts.

It’s implied the clowns are the low men in the circus’s caste; those who cannot perform elsewhere are subjected to the humiliation of clowndom. Does the scorn beget the malice, or did the malice beget the scorn?

Perhaps this is why the clowns are never shown as actual humans. Throughout the movie, they either appear in their grotesque, make-up clad personas, or in various states of undress as silhouettes inside a circus tent. At all times, they are either 100% clown or some spectral figure. They are never seen as human, because there is certainly no humanity to them.

However, the most questionable employees are the laborers. The laborers are not entertainers; they have no face time with any circus patrons. And yet, they are the most important employees of the circus. They are responsible for unloading the train and erecting the many circus structures.

These laborers, tasked with the most arduous and backbreaking of work, are all large black men. As a stylistic choice, they are all depicted faceless. Not even worthy of dignity, they are robbed of any identity and distinguishing characteristics beyond skin color.

To cushion our objections, the laborers sing about how much they like the work. The song is no comfort. They sing about being illiterate. They sing about being underpaid, and routinely subject to wage theft. They sing about how its their very nature to be irresponsible with money. They literally use the word “slave,” and “ape” to describe their circumstances. Thank you, 1940s.

The only other black characters are a murder of crows introduced in act three. These crows must be less racist in depiction and demeanor than the laborers, right? They couldn't possibly be worse, right? Then one learns the leader of the avian posse was named “Jim Crow” on all Disney material until the 1960s.

The entire Civil Rights Movement needed to happen, but somebody eventually realized a children’s cartoon character named after the most provocative blackface character in history, the namesake of the American laws that enforced segregation, was a bad idea. It didn’t help Jim was voiced by a white actor. Cliff Edwards voiced Jim Crow (later renamed Dandy Crow), the same actor also voiced Jiminy Cricket in Pinocchio. Jiminy Cricket has appeared regularly as a beloved figure in Disney merchandise and material. Dandy Crow has not.

To Disney’s credit, the other crows were voiced by actual black actors. Although, one has to wonder if the AAVE was written into the screenplay, or if the director asked the actors to create it on the spot. There’s no good answer.

The crows’ musical number was performed by the all-black Hall Johnson Choir (with the exception of Edwards’s vocals). Their number, When I See an Elephant Fly, is one of the better pieces of music in the Disney catalog. It's full of jazz scatting and clever wordplay. It’s a shame its existence is marred by its racially charged source.

How an oversized pair of ears grants the ability to fly is not important. It’s a cartoon. The ears are a means to an end: the physical feature that made Dumbo a laughingstock also granted him a most unique ability. Differences make us strong. It’s a good moral (even if the film is hypocritical).

The depiction of the moral’s resolution, however, raises eyebrows. Upon discovering he has the ability to fly, Dumbo seizes the opportunity to take revenge on those who wronged him. He circles around the big top, swooping at the ringmaster, scaring the clowns, shooting peanuts at the other elephants like bullets from a machine gun. ‘Make your enemies pay,’ is the takeaway. Suffer all, enemies of Dumbo.

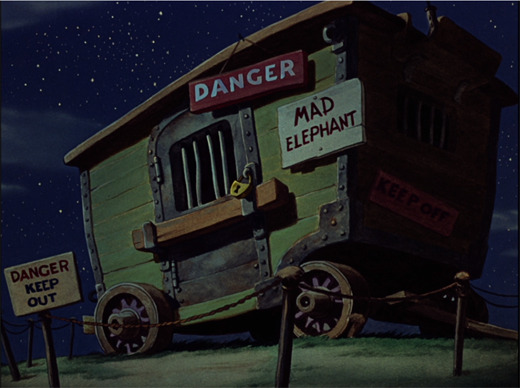

Some may argue Dumbo’s character arc is not redemption for himself, but for his mother. Mrs Jumbo spanks a young boy who assaults her infant son. The circus folk misinterpret this act as a rampage. She’s is subsequently shackled and imprisoned for the forseeable future.

Even after being deemed hazardous and mad, Mrs Jumbo is never sent away. There is no indication of punishment beyond isolation (why the circus keeps a dangerous rampaging elephant on circus grounds is a creative liberty). The true punishment is being separated from her son.

The movie ends with Dumbo as the star of the show. Everyone sings his praises, he has his own personal train car, and Mrs Jumbo is freed. The question is, why is Mrs Jumbo freed? Just because Dumbo is beloved, why is Mrs Jumbo’s perception as a threat forgotten? Why is she forgiven because her son is popular? Dumbo cannot speak, how can he serve as a character witness? Why does Dumbo's achievement redeem his mother's actions? The writers delivered a happy ending by solving a problem that was never actually solved.

Dumbo is a film full of illogical scenes and developments. It's grandfathered into the cultural pantheon despite outdated imagery and storytelling. It has good intentions, utilizing themes of overcoming adversity, the endurance of familial love, and appreciating each other's differences. But these good intentions are drowned in too many narrative shortcuts and a sloppy execution. It’s a pleasant movie the less you remember, and most people’s memories are hazy. What’s more appropriate from a film whose most famous scene is a surreal drunken musical hallucination?

Fantasia Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs Pinocchio Dumbo

#Dumbo#Disney#walt disney#Walt Disney Animation Studios#Film Criticism#film analysis#review#Disney Canon

9 notes

·

View notes

Note

Looking back, was Madoka Magica really that dark? Only three characters actually die, two of whom are later resurrected through the power of love. Blood and gore wise, most blood is offscreen, and that which is shown is fairly tame compared to other dark magical girl shows. Yet somehow, this show the show managed to hit me in the gut more than far more horrific and bloodier dark magical girl shows ever have. Why?

That doesn’t sound surprising at all, and it all comes down toexecution.

See,people often have this false idea when it comes to “mature” stories, inthat things like character deaths, blood and gore, and suffering are thebuilding blocks of maturity. But they’re not. They’re tools, and like all tools,they can be wielded correctly and incorrectly. Quite often, less is more, andtoo much grimdark results in an edgy, tryhard mess of a thing that isn’t maturein the slightest. This is one of the reasons why Blood-C got such a negativereaction, or why Elfen Lied is so divisive. I mean, don’t get me wrong, I loveme some Elfen Lied, but even I admit that it’s a schlocky white-hot mess. Itjust so happens to be my kindof schlocky, white-hot mess.

So yeah, I know this is weird coming from the apparent king ofTouhou Grimdark (cut me some slack though, I learn as I go), but gratuitousviolence does not, in of itself, equal maturity or anything of substance. Atbest you get the adolescent view of maturity, which is just so cynical andtiresome.

Madoka Magica, on the other hand, is a different sort of beastentirely. That show’s been out for years, but I am continuously impressed byjust how well-crafted it is, and how the creators used the tools at theirdisposal to get so much out of so little.

First of all, there’s the genre itself. Now, darkdeconstructions of Magical Girl shows are nothing new. Utena had already poppedthat cherry years ago, and you already mentioned how others had…less of animpact than PMMM did. But even so, the Magica Girl genre is one that’s almostuniversally associated with little girls. So, lots of bright colors, optimism,and cute, and the good guys and bad guys are easily distinguishable, and goodalways triumphs over evil. So even if new viewers know that something is up,their guard is still automatically going to be dropped, at least a little.

Second, we have the art style. Now, this is very interesting, inthat they went with a very Hidemari Sketch sort of style, where the girls allhave designs that are cute, appealing, and very distinctive, but never goingoverboard with the cuteness to the point where it becomes obnoxious. Even withthe fairly cartoony designs, their actual movement is pretty realistic, and isnever exaggerated for comedic effect or goes super-deformed and all that.Furthermore, rare for something of this nature, they are never objectifiedand/or used for fanservice in the slightest. A more realistic or a more adultstyle wouldn’t have been nearly as effective, nor would something sexier. It’sjust enough to make you like the girls and want the best for them, but notenough to get annoying or ruin the mood with unnecessary fanservice.

So basically, to get a little neckbeardy with it, the art styleis meant to make the viewers want to protect and comfort the girls, but notstrangle them for being way too moe, or fuck them for that matter.

…

Well, I mean, lots of people still do, but it’s the internet,so…

…

Moving on.

Anyway, continuing with theanimation, let’s talk about the witches. In sharp contrast to the somewhatcartoony designed but mostly realistically animated real world, the witchbarriers go for a surreal, dream-like feel, with the weird, jerky, low framerate movements of the witches and their familiars to the bizarre designs thatstick more-or-less to aesthetic themes but still have no explanation and anoverall look that, rather than being overly and obviously dark and evil, isinstead…wrong. Off. Alien. Discomforting rather than outright scary. Thewitches are meant to clash with the characters’ animation in a way that isdeliberately uncomfortable without spilling into cheesy. I mean, puffballs withbutterfly bodies and big handlebar mustaches? Spotted mice in nurse hats? Howis that scary? But just look at how they move, how they sound, and it becomesincredibly unnerving. Even before the big episode three twist, until which PMMMcould still pass for a more standard Magical Girl show, it still stood out withjust how bizarrely disturbing its monsters are. There is something genuinelyunsettling about them, a sense of dread that just permeates their every scene,even when our heroes are victorious.

And with that, I’ve exhaustedmost of the synonyms for “disturbing.” Let’s move on.

So, we’ve gone over how theart and animation is carefully crafted to evoke a specific reaction from theviewers, but what about the story itself? Well, like what was discussedearlier, part of what makes PMMM work so well is that despite its grandambitions and epic feels, the bulk of the show is…actually pretty small. Imean, save for the universe-changing repercussions of Madoka’s wish at the veryend, most of the focus is kept away from the world at large and remains on asmall group of characters and how being sucked into the contract system affectsthem. The story revolves around these five girls and is all about theirpersonal lives, and the whole Incubator thing is portrayed as alarger-than-they-can-imagine thing that’s been going on since the beginning oftime that they can’t do anything about, so why even bother trying? For Kyubey,it’s pretty much just business as usual, with the gang just being another setof marks in a long, long line of them, to be chewed up and spat out by the cogsof his machine.

And that takes us to what youmentioned earlier, about how PMMM has fewer character deaths, less violence,and nearly no gore in comparison to other shows, but somehow manages to leave abigger impact. And that comes down to one of the most important rules aboutstorytelling: it’s not what you’re about, it’s how you’re about it. Killing offcharacters doesn’t make a story mature, hurting your characters doesn’t makeyour story mature, or even using something as risky as rape doesn’t make yourstory mature; those are just the catalysts. Rather, maturity comes fromexploring how those things affect your characters, how it changes their livesand how they change and grow in response to them. Mami’s sudden and shockingdeath had profound effects on Madoka and Sayaka, and it’s by exploring thoseeffects that it feels like it has such a big impact, in that it shatteredMadoka’s perfect world and sent her into a bout of depression while motivatingSayaka into recklessness to compensate for her guilt in not being there to helpMami and overcompensate in trying to take her place. The reveal of the MagicalGirls as liches with their souls literally contained within their soul gems wasa big twist in of itself, but by taking the time to show how it set Sayaka intoher downward spiral into self-destruction coupled with having the oppositeeffect on Kyoko by jarring her out of her self-centered nihilism and motivatingher to start reaching out to Sayaka it really does feel like it has actualmeaning beyond shock value. And their deaths become even more tragic, asKyubey’s later monologue shows that they were doomed from the beginning, andnothing other than a damned miracle was going to save anyone. And being that hehad the monopoly on miracles in that universe, the audience is left bitingtheir nails and hanging on the edges of their seats through the climax, prayingthat an out would be found while fearing that there would be none to be found.Which just makes Madoka’s loophole of a wish all the more gratifying, whilestill being bittersweet. Because a happy ending just wasn’t possible, but shefound a way to prevent an all-out tragedy, a way to alleviate the bulk of thepain. And all it cost was her earthly existence.

Anyway, we’ve talked aboutthe visuals and story direction, so now let’s talk characterization. This is yetanother place where this show shines. Becauseeven though it only had a few episodes, the relatively small cast and focus ontheir personal problems allowed for a lot of character development. It helped that,save for Madoka’s, each of their wishes was something small and easilyunderstandable. Mami just wanted to live, Kyoko just wanted people to listen toher father, Sayaka just wanted her close friend and crush to get better whiletaking up Mami’s responsibilities, and Homura just wanted to save her dearfriend, who had been one of the few people to ever give her positive attention.Hell, even Madoka’s original wish was to save a cat. And like their designs,their personalities are all distinct, balanced between likeable strengths andtragic flaws: Mami is stalwart and nurturing, but also tripped up by hercrippling loneliness. Sayaka is determine and has a strong sense of justice,but also brash and prone to self-loathing. Madoka is kind-hearted andencouraging, but held back by her lack of self-esteem. As for Homura and Kyoko,they’re introduced us when they are at their worst, but do to cleverstorytelling and exposition, we then see the goodness in them and what theyused to be, and it becomes all the more easier to understand how they becamethe way they are. And again, despite its small number of episodes, the showreally takes the time to show how these personalities bounce off each other andconflict, while also showing how the consequences of their actions change them.I really like how they did it two: the show is essentially divided into fourmini-arcs of three episodes apiece, with the main focus on a different girl perarc, with Madoka being something of a passive POV protagonist throughout the wholeshow: first it’s Mami, then Sayaka, then Kyoko, and finally Homura. And as isexpected, each mini-arc ends in a tragedy, from Mami’s death to Sayaka’srealization about the truth of soul gems to Kyoko’s final stand to Homurafeeling as if she’s lost Madoka forever. But even with all that dark, it stillends on a note that is, while bittersweet, is still optimistic. Madoka is stillgone and Sayaka is still dead, but they seem to have come to terms with that. Also,Kyoko and Mami are alive and on good terms again, Homura has something new tofight for, and the universe is a little less cruel, showing that despiteeverything, it was all worth it in the end, and all of their struggles, pains,mistakes, and tears mattered.

I could go on and on and on,but let’s sum it up with a tl;dr: Puella Magi Madoka Magica may not have had nearly the amount of death and despair as other shows and very littlegore, but it had a far greater impact because it was carefully and brilliantlyconstructed from top to bottom to hit you right where it hurts, twist theknife, and still make you thankful for the ride. And I wouldn’t have it anyother way.

#pmmm#puella magi madoka magica#Madoka Kaname#sayaka miki#mami tomoe#kyoko sakura#homura akemi#gen urobuchi

459 notes

·

View notes

Note

What are other books/series that you'd recommend that are in the same vein as Animorphs?

Honestly, your ask inspired me to get off my butt and finally compile a list of the books that I reference with my character names in Eleutherophobia, because in a lot of ways that’s my list of recommendations right there: I deliberately chose children’s and/or sci-fi stories that deal really well with death, war, dark humor, class divides, and/or social trauma for most of my character names. I also tend to use allusions that either comment on Animorphs or on the source work in the way that the names come up.

That said, here are The Ten Greatest Animorphs-Adjacent Works of Literature According to Sol’s Totally Arbitrary Standards:

1. A Ring of Endless Light, Madeline L’Engle

This is a really good teen story that, in painfully accurate detail, captures exactly what it’s like to be too young to really understand death while forced to confront it anyway. I read it at about the same age as the protagonist, not that long after having suffered the first major loss in my own life (a friend, also 14, killed by cancer). It accomplished exactly what a really good novel should by putting words to the experiences that I couldn’t describe properly either then or now. This isn’t a light read—its main plot is about terminal illness, and the story is bookended by two different unexpected deaths—but it is a powerful one.

2. The One and Only Ivan, K.A. Applegate

This prose novel (think an epic poem, sort of like The Iliad, only better) obviously has everything in it that makes K.A. Applegate one of the greatest children’s authors alive: heartbreaking tragedy, disturbing commentary on the human condition, unforgettably individuated narration, pop culture references, and poop jokes. Although I’m mostly joking when I refer to Marco in my tags as “the one and only” (since this book is narrated by a gorilla), Ivan does remind me of Marco with his sometimes-toxic determination to see the best of every possible situation when grief and anger allow him no other outlet for his feelings and the terrifying lengths to which he will go in order to protect his found family.

3. My Teacher Flunked the Planet, Bruce Coville

Although the entire My Teacher is an Alien series is really well-written and powerful, this book is definitely my favorite because in many ways it’s sort of an anti-Animorphs. Whereas Animorphs (at least in my opinion) is a story about the battle for personal freedom and privacy, with huge emphasis on one’s inner identity remaining the same even as one’s physical shape changes, My Teacher Flunked the Planet is about how maybe the answer to all our problems doesn’t come from violent struggle for personal freedoms, but from peaceful acceptance of common ground among all humans. There’s a lot of intuitive appeal in reading about the protagonists of a war epic all shouting “Free or dead!” before going off to battle (#13) but this series actually deconstructs that message as blind and excessive, especially when options like “all you need is love” or “no man is an island” are still on the table.

4. Moon Called, Patricia Briggs

I think this book is the only piece of adult fiction on this whole list, and that’s no accident: the Mercy Thompson series is all about the process of adulthood and how that happens to interact with the presence of the supernatural in one’s life. The last time I tried to make a list of my favorite fictional characters of all time, it ended up being about 75% Mercy Thompson series, 24% Animorphs, and the other 1% was Eugenides Attolis (who I’ll get back to in my rec for The Theif). These books are about a VW mechanic, her security-administrator next door neighbor, her surgeon roommate, her retail-working best friend and his defense-lawyer boyfriend, and their cybersecurity frenemy. The fact that half those characters are supernatural creatures only serves to inconvenience Mercy as she contemplates how she’s going to pay next month’s rent when a demon destroyed her trailer, whether to get married for the first time at age 38 when doing so would make her co-alpha of a werewolf pack, what to do about the vampires that keep asking for her mechanic services without paying, and how to be a good neighbor to the area ghosts that only she can see.

5. The Thief, Megan Whalen Turner

This book (and its sequel A Conspiracy of Kings) are the ones that I return to every time I struggle with first-person writing and no Animorphs are at hand. Turner does maybe the best of any author I’ve seen of having character-driven plots and plot-driven characters. This book is the story of five individuals (with five slightly different agendas) traveling through an alternate version of ancient Greece and Turkey with a deceptively simple goal: they all want to work together to steal a magical stone from the gods. However, the narrator especially is more complicated than he seems, which everyone else fails to realize at their own detriment.

6. Homecoming, Cynthia Voight

Critics have compared this book to a modern, realistic reimagining of The Boxcar Children, which always made a lot of sense to me. It’s the story of four children who must find their own way from relative to relative in an effort to find a permanent home, struggling every single day with the question of what they will eat and how they will find a safe place to sleep that night. The main character herself is one of those unforgettable heroines that is easy to love even as she makes mistake after mistake as a 13-year-old who is forced to navigate the world of adult decisions, shouldering the burden of finding a home for her family because even though she doesn’t know what she’s doing, it’s not like she can ask an adult for help. Too bad the Animorphs didn’t have Dicey Tillerman on the team, because this girl shepherds her family through an Odysseus-worthy journey on stubbornness alone.

7. High Wizardry, Diane Duane

The Young Wizards series has a lot of good books in it, but this one will forever be my favorite because it shows that weird, awkward, science- and sci-fi-loving girls can save the world just by being themselves. Dairine Callahan was the first geek girl who ever taught me it’s not only okay to be a geek girl, but that there’s power in empiricism when properly applied. In contrast to a lot of scientifically “smart” characters from sci-fi (who often use long words or good grades as a shorthand for conveying their expertise), Dairine applies the scientific method, programming theory, and a love of Star Wars to her problem-solving skills in a way that easily conveys that she—and Diane Duane, for that matter—love science for what it is: an adventurous way of taking apart the universe to find out how it works. This is sci-fi at its best.

8. Dr. Franklin’s Island, Gwyneth Jones

If you love Animorphs’ body horror, personal tragedy, and portrayal of teens struggling to cope with unimaginable circumstances, then this the book for you! I’m only being about 80% facetious, because this story has all that and a huge dose of teen angst besides. It’s a loose retelling of H.G. Wells’s classic The Island of Doctor Moreau, but really goes beyond that story by showing how the identity struggles of adolescence interact with the identity struggles of being kidnapped by a mad scientist and forcibly transformed into a different animal. It’s a survival story with a huge dose of nightmare fuel (seriously: this book is not for the faint of heart, the weak of stomach, or anyone who skips the descriptions of skin melting and bones realigning in Animorphs) but it’s also one about how three kids with a ton of personal differences and no particular reason to like each other become fast friends over the process of surviving hell by relying on each other.

9. Sideways Stories from Wayside School, Louis Sachar

Louis Sachar is the only author I’ve ever seen who can match K.A. Applegate for nihilistic humor and absurdist horror layered on top of an awesome story that’s actually fun for kids to read. Where he beats K.A. Applegate out is in terms of his ability to generate dream-like surrealism in these short stories, each one of which starts out hilariously bizarre and gradually devolves into becoming nightmare-inducingly bizarre. Generally, each one ends with an unsettling abruptness that never quite relieves the tension evoked by the horror of the previous pages, leaving the reader wondering what the hell just happened, and whether one just wet one’s pants from laughing too hard or from sheer existential terror. The fact that so much of this effect is achieved through meta-humor and wordplay is, in my opinion, just a testament to Sachar’s huge skill as a writer.

10. Magyk, Angie Sage

As I mentioned, the Septimus Heap series is probably the second most powerful portrayal of the effect of war on children that I’ve ever encountered; the fact that the books are so funny on top of their subtle horror is a huge bonus as well. There are a lot of excellent moments throughout the series where the one protagonist’s history as a child soldier (throughout this novel he’s simply known as “Boy 412″) will interact with his stepsister’s (and co-protagonist’s) comparatively privileged upbringing. Probably my favorite is the moment when the two main characters end up working together to kill a man in self-defense, and the girl raised as a princess makes the horrified comment that she never thought she’d actually have to kill someone, to which her stepbrother calmly responds that that’s a privilege he never had; the ensuing conversation strongly implies that his psyche has been permanently damaged by the fact that he was raised to kill pretty much from infancy, but all in a way that is both child-friendly and respectful of real trauma.

#ya sf#book recs#sci fi#children's literature#animorphs#a ring of endless light#the one and only ivan#my teacher flunked the planet#moon called#the theif#homecoming#high wizardry#dr. franklin's island#sideways stories from wayside school#magyk

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Now I Am Become Slut, Destroyer of Worlds

The host is alive. She is sentient. She is self-aware. And she knows you have programmed her to attack herself and the others.

Nope! Not a blog about Westworld! At least, most of it isn’t. I want to talk about The Bachelor and I want to explain why this show is the place to be, if you’re into the shock of watching creations outsmart their creator-controllers. The more I read this Bach season as a rumination on feeling fictional and clawing for “reality,” the more I was reminded of HBO’s ambitious series on gnosticism, humanity, and the function of storytelling. Might even go so far to say that these two shows share a soul; Dolores Abernathy would be right at home at a rose ceremony!

Please follow me, down into a fake mansion that houses a harem, where we can take a closer look at the things that made The Bachelor so distinctive in its 21st season: existential female anxiety, textual reflexivity, and the peculiar journey of Corinne, a single trope that managed to awaken and rewrite herself.

Born into an apocalyptic Trumpworld, this iteration of The Bachelor became something kind of dark, dreadful, and a little bit out-of-control. Of course, The Bachelor is always a circus, and that’s why so many people hate it: for a television fan, it takes a strong set of stones to follow something so vapid, so dependent on tired stereotypes and romantic wish-fulfillment, so misogynistic, so corporate and disingenuous. How many different ways can producers arrange 30 beautiful women in a Love Thunderdome as they compete for the affections of one bland white man? But there was something poisonous in American culture at large that made Season 21 into something else, something crazier. Perhaps the 2016 election left a vacuum of hope that encouraged The Bachelor producers to lean into self-destruction as an aesthetic. Perhaps we, the audience, are evolving to watch ourselves watching TV, and we prefer everything to be kind of about storytelling – ergo the timely popularity of diverse “meta” shows like Westworld, American Horror Story, Fleabag.

Either way, the new Bachelor was defined by these new and distinctive notes:

Contestants who bristled inside their assigned story cages and pointedly drew attention to the process of being written as characters.

The season’s primary “villain,” Corinne, who transcended the confines of the Bach with a Joker-like sense of chaotic sexuality and stunningly re-branded her arc as sex-positive feminist heroism.

An unwilling Bachelor whose weird charisma relied on his apathy, nihilism, and constant critique of the format. Nick undermined our reception of the Bachelor experience by positioning himself as a bored observer – distancing himself from the contestants and the ideological underpinnings of the show.

First, I want to take on Bullet Number One – the Westworldian crises of self that entered this season of the Bachelor early on and began the process of destabilizing narratives and the women forced to live them. Take a look at what happened to Jasmine G on Night 1. Now, it’s not unusual for Bachelor women to immediately recoil from the uncanniness of this environment – to be a Bachelor contestant, to be on a reality dating competition, is to be subjected to spirit-breaking. These women are tested every moment with the pressures of self-criticism, of being filmed, of being beautiful, of being charming, of systematically attacking and defeating your stunning competitors. But something about Jasmine G’s body language and wording struck me as a crisis of self, a dissociative episode which bespeaks her sudden awareness that she is performing and this whole thing – maybe any love-hunt – is theater without meaning.

youtube

“It doesn’t matter. It’s out of my control. There’s nothing I can do. Holy shit. Who the fuck am I? I’m blown away right now. Who am I?”

Night 1 would be the first of Jasmine’s many system failures, glitches in her personality and physical affect which provided an alarming counterpoint to the self-policing composure we’re used to seeing on these women. Nick eliminated her because of her unpleasant urge to question the “realism” of herself, of him, of the experience. And this was not the only instance of unusual meta-awareness amongst the women. Many of the others expressed a certain repugnance at the roles in which they were pigeonholed – at their status as storylines. Liz’s only mission, with mounting desperation, was to rewrite her way from Nick’s opportunistic ex-fling all the way to romantic legitimacy. Taylor realized too late that her Bachelor persona and “real” professional life were being mapped onto one another and she’d dug herself into the “bitch bully” hole (with the help of her nemesis Corinne). Taylor also literally theorized that some women are better-programmed for love! What could be more Westworld than attempting to parse the resident slut’s “emotional intelligence”?

So there was a significant change in the show here, in which the women’s grasp or ignorance of “being produced” was of paramount importance to how we perceived them. To compare these women to WW characters like Dolores and Maeve – remaining basic, guileless, and easily overwritten ensured a measure of success in the competition and preserved their classic Bachelor likeability factor.

So with that said, I’m dying to get back to Corinne. Here was a contestant who really jumped off the screen for reasons I’ve never seen an antagonist “pop” before. Unlike a villain such as, say, Season 20’s Olivia, Corinne worked to distinguish herself as a breakout character – not just through behavior but through actual world-building. Starting the show out by mentioning her current nanny Raquel was a stroke of genius; Raquel was a framing device that indicated Corinne inhabited a bizarre fantasy world inside and outside the show. In so many ways. Corinne deliberately ate endless blocks of cheese on camera. She feigned naps, eyes closed, smiling beatifically as she “dreamed” of Nick. She self-consciously and joyfully delivered dialogue she knew would light up the internet. Clutching her breasts and huffing, “Does this seem like someone who’s immature?” Staring soullessly into the lens and intoning, “My heart is gold, but my vagine is platinum.” Luring Nick into an inexplicable bounce house and toplessly dry-humping him with abandon. Corinne’s promiscuity, and her persona, were over-the-top but deliberately, defiantly, and delightfully self-choreographed. We know the floozy never wins, but when the floozy knows it, ignores it, and enjoys her role, she transcends happy endings.

And most interestingly, Corinne elevated her self-awareness and self-programming into a magnificent final act. During “The Women Tell All” (a reunion episode which airs before the finale) Corinne, in one fell swoop, ret-conned her entire Bachelor journey as a feminist rumspringa. “I was just doing me,” she demurely insisted, while the other contestants fought to defend her sexual agency. They leaped to defend the resident slut as the bravest and most authentic person amongst them. Corinne sat, resplendent, her eyes bearing no trace of the mischief and malevolence that had been her character cornerstones. She’d accomplished a rewrite akin to “it was all a dream.” Later, women sobbed while Liz declared her sexual encounter with Nick had not “defined” her, and they took turns praising their sister for her humanitarian work. The thematic tide-turn from “a search for true love” to “an inner journey toward female unity and empowerment” made for the most overtly political and topical episode The Bachelor has had, maybe ever – and it bespoke the malleability of reality fiction in a way the show has never previously approached.

In many ways, it was Bachelor Nick’s abdication of his role that allowed the TV text to refocus itself on the women “waking up” and growing through their relationships to one another. It’s hard, as a viewer, to engage with story about passive female players being driven toward romantic fulfillment, when the end-goal is a guy who’d be content to go home immediately and eat cold pizza. As we know, the guy had already been through two seasons of The Bachelorette and one summer of Bachelor in Paradise – his entire narrative was “last-ditch effort for love.” Nick made it his business to call out the fakery of The Bachelor, and the futility of it: “Let’s try to be as normal as possible in an abnormal environment.” “I’ve been in their shoes, and I know how much it sucks.” I certainly like Nick as a person – I like that he cries when he feels stuff, and I like that he hates being The Bachelor but loves being famous, and I like that he let women who were too good for him go, so they could fly and be free and be the first black Bachelorette. But if Nick did anything other than represent a neat resolution of the presented Bachelor narrative, he effectively denied our suspension of disbelief and exposed this particular season as “reality farce with no point.” Prince Charming was just in it for the international travel and the free food. I sympathize. And it’s fun to watch The Bachelor pretend that this isn’t a huge problem.

SO! I posit here that, at least for this season, The Bachelor evolved beyond the story of single women and their search for love. You might say that instead of being about singlehood, this show became about “the singularity” – that moment when program/character/trope/story/world comes alive and begins to adapt and change itself. I wonder: is it a better ride for the reality-consuming audience, when “we know they know”? At what point does watching a character with meta-awareness become confusing, or tiresome, rather than thrilling? And most importantly, what are the differences between watching reality television and prestige drama when we’re grappling with these issues? This question, perhaps, is of paramount importance for TV fans as we go forward; if there’s something in the water that’s poisoning every genre of narrative experience (or making it tastier), we have to put our fingers on it. Why do I watch so much television about women in traps, whose self-actualization and creative escapes are catalyzed by patriarchal violence? Why is it so easy to find that story?

I think it’s easy to brush aside shows like The Bachelor precisely because they are so heavily consumed, across political and cultural lines, and “mass appeal” television has the reputation of reifying harmful structures of power. For really good reason. But it’s important to locate these small moments of medium-transcendence within these TV texts. More and more, the characters we use and abuse are turning directly towards us. These fictional delights have real ends, and it’s never, never about the final rose.

via WordPress http://ift.tt/2mjHH8j

0 notes