#letters of English aristocrats in France

Text

Massena dishes to an English aristocrat

Elizabeth, Duchess of Devonshire, to [her son] Augustus Foster. Marseilles, December 30, 1814

Massena lives in the same street with us; he is full of attention to us, and, though broken in health and spirits, animates on topics which interest him. I heard that he would not talk about Bonaparte, and I was fearful, though very anxious, to name the subject. Last night we went to the prefect's, who has a fine house, and gave a very pretty ball. Massena sat between Lady Bessborough and me; he said something about Grassini. “Oh,” I said, too happy to find an occasion, “Etoit ce quand Bonaparte fut si amoureux d'elle?” “Bonaparte,” his eye assuming a stern expression, “ Bonaparte n'a jamais aimé personne, personne." I then went on from one thing to another, I found I could do so, and it was very interesting. “Quelle impression, Monsieur le Marechale, vous fit il, quand vous le connûtes premièrement?” “Un grand orgueil, Madame la Duchesse. Je l'ai connu qu'il n'étoit que Lieutenant colonel—des moyens, et pour cela de grand moyens, surtout dans la prosperité; dans l'adversité il manquoit de tête, il n'avoit rien de grand.” Of himself he said, “il m'aimoit ou en faisoit semblant, car jamais il n'a rien aimé que son ambition; il me tutoya c'étoit a Milan quand il commandoit en chef qu'il me dit, Massena ne voudroit tu être un des directeurs?' 'Non, je lui répondit, je ne me connais pas en politique, je ne sais faire que la guerre mais toi ne voudrais tu pas en être?' II me repondit 'avec quatre imbeciles, non, moi seul, oui'." He continued, "C'est lui qui m'a baptise enfant de la victoire—et bien, avec cela je fis une chute qui m'empechoit d'etre avec l'armée; il vint quatre fois la nuit me voir." "Mais cela," I said, "marquoit quelque sensibilité ." "II avoit besoin de moi. Je fis une maladie apres, non seulement il ne vint pas; il n'envoya pas même savoir de mes nouvelles." Many other things he told us, and we talked about, and it was very interesting. I'm afraid he don't live as he ought to do, but to us, &c, &c

---

Massena sat between Lady Bessborough and me; he said something about Grassini [Italian singer, Napoleon’s mistress]. “Oh,” I said, too happy to find an occasion, “Was it when Bonaparte was so in love with her?” “Bonaparte,” his eye assuming a stern expression, “Bonaparte never loved anyone, anyone.” I then went on from one thing to another, I found I could do so, and it was very interesting. “What impression, Monsieur le Marechal, did he make when you first met him?” "Great pride, Madame la Duchess. I knew him when he was only Lieutenant Colonel—he had means [intelligence, ability, etc], and for that, great means, especially in prosperity; in adversity he lost his head, then he had nothing great.” Of himself he said, "He loved me, or seemed to, because he never loved anything but his ambition; he tutoyer’d me in Milan when he was in command. He asked me, Massena, wouldn't you want to be one of the directors?' 'No, I answered him, I don't know politics, I only know how to make war; would you want to be one?' He replied, 'With four fools, no. I, alone, yes'. [Massena] continued, "It was he who baptized me child of victory—well, with that I took a fall that prevented me from being with the army; he came four times a night to see me." "But that," I said, "showed some sensitivity." "He needed me. I fell ill afterwards, not only did he not come; he did not even send to hear from me."

The Two Duchesses, Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire, Elizabeth, Duchess of Devonshire.

hathitrust

#Massena really frosted by Napoleon's neglect when he was sick#letters of English aristocrats in France#Massena

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

tuberose and rose tinted glasses

┊ ⋆ ┊ . ┊ ┊┊ ⋆ ┊ . ┊ ┊┊ ⋆ ┊ . ┊ ┊┊ ⋆ ┊ . ┊ ┊┊ ⋆ ┊ . ┊ ┊┊

summary: A work trip to France lands you in a bar in Grasse. But it's the actions of a masked British man that puts him next to you with brandy in your hands.

pairing: Simon "Ghost" Riley x fem!Reader

warnings: swearing, harassment

a/n: literally writing this on my lunch break, pining over the idea of taking a trip to grasse and submerging myself in their fields of jasmine

┊ ⋆ ┊ . ┊ ┊┊ ⋆ ┊ . ┊ ┊┊ ⋆ ┊ . ┊ ┊┊ ⋆ ┊ . ┊ ┊┊ ⋆ ┊ . ┊ ┊┊

Grasse, France the world's capital of perfume. As you walked the late-night streets filled with fragrant, floral air, you couldn't help but feel melancholy that you were here on business and not for pleasure. Your head flooded with the smells of the city as you noted the various notes of tuberose and jasmine as you walked. Despite your frequent trips here, you still fell in love with the rows of flowers in peak bloom.

Your heels clicked on the ground as you saw a red awning with the letterings of a bar on it. You sought refuge after a long day of discussing new fragrances with your colleagues and creating the perfect blend for another company.

You pushed the doors open and sat at one of the velvet cushioned seats in the dimly lit place. As you patted the soft fabric with your fingertips, you admired how the bar was lit with a warm rose light. You noted only a small amount of patrons in the place. It looked to be only you, the bartender, and maybe three other men in this entire pink atmosphere. However, you paid them no mind as the bartender approached you.

"Qu’est-ce que je vous sers?” ("What can I get you?") He said, giving you a moment to comprehend what he was saying. You couldn't blame him, you were far from a stereotypical French woman. Maybe it was the way you carried yourself or just looked so typically American that tipped him off to your presence. However, your years working with your company and traveling from the US to France made you thankfully bilingual in the romantic language.

Just as he was about to ask the answer in English, you responded, "Je prends un un verre d'Armagnac Aristocrat, s’il vous plaît." ("I'll have a glass of Armagnac Aristocrat please.") Your clientele had refined your tastes. Never one for wine, you preferred a strong drink to accompany you.

"Fille chanceuse, je viens d'ouvrir une bouteille pour le monsieur là-bas," ("Lucky girl, I just opened a bottle for the gentleman over there") he replied and signaled to a man also sitting alone on the far side of the bar. Unknowingly, this man had luckily ordered a bottle of the spirit and allowed for your drink to be served immediately, the Armagnac being perfectly oxidized in the French air. The man in question was broad and had his head down. As the rose light illuminated his figure, he seemed more interested in his drink than the atmosphere around him. His eyes looked concentrated on the caramel liquid in his glass. You wondered what his full expression was as, despite his eyes, his face was primarily obstructed by a black mask.

Your eyes left the man as the bartender gently set your drink down on a scarlet napkin. "Merci," you said gently and he left you to enjoy your purchase. As you sipped on your drink, you savored the smokiness of the brandy coupled with the sharp bitterness of the Lillet. You swallowed the liquid, enjoying the subtle sweetness of the ginger ale. This was a drink to be sipped, not greedily drank as you enjoyed how the flavors came together to create a perfect beverage. You gently traced your fingers on the edge of the glass and smeared your reddened lipstick on its rim.

However, your moment of solace would soon be interrupted by a man who took an abrupt seat next to you. You could tell by the way he was swaying and leaning on the counter that he had one too many. He smelled like cheap cologne, probably something he bought as a souvenir and beer.

"Ma chérie, tu es very sexy" ("My darling, you are very sexy") the man leered over you. You couldn't help but roll your eyes. His poor mixing of French and English made you feel embarrassed for him. He acted like this was the epitome of flirtation and almost expected you to throw yourself on him.

You attempted to ignore the man, turning your body away and protectively hovering over your drink. He was determined, grabbing your shoulder to face him. "You smell expensive, tell me do you put your perfume where you want to be kissed?" he spoke sultry in another crude attempt at flirting.

"Not interested," you said, waving your arm in a dismissive motion. You just wanted to enjoy a night with some liquor and the smells of the town. Your gold bracelets clanked as you brushed him away. However, they soon clattered together as he aggressively grabbed your wrist.

"Oh so you speak English, sweetheart," he began, breathing his hot alcohol-laced breath in your face. "Lucky for you, I can speak French between your legs," he finished as you tried to free yourself from his grip. You pushed against his chest and elbowed him but he was relentless. Your eyes looked wildly around as you tried to receive any help, but seemingly the bar had emptied and the bartender was nowhere to be found. "C'mon sweetheart, let me show you a good time," he said and pressed harder on your wrist. Your arm pricked with pain from his grip. Suddenly his hands were pried off of you and he was thrown back.

You turned to see it was the man from across the bar, now standing next to you and glaring at the downed man. "She politely said 'fuck off, asshole', do you understand that?" he barked at him in a deep voice. The drunk man looked ready for a fight as he stood up. But something about the masked man's aura made him rescind. As quick as he came, the drunkard left. He ceremoniously flipped him off and with a string of profanities, exited the bar in a huff.

"Thank you," you said and motioned for the man to take a seat, "I think I owe you a drink." He briefly glanced over to where he sat and you both saw the empty glass. "Looks like you need a refill, anyways," you remarked. It seemed like he agreed as he took a seat to your right.

You signaled to the bartender, who for some reason had not acknowledged the entire fiasco that just occurred. He came over and you asked, "Un autre de ceux-ci pour moi et le monsieur," ("Another one of these for myself and the gentleman") and pointed to your dwindling glass. He nodded and went behind the counter to prepare both your liquid vices.

"So what brings you to Grasse? You don't seem like a Frenchman to me," you asked turning to face your new companion. In the bar's lighting, you could see him slightly better than before. His light eyelashes glistened in the light and contrasted with his amber eyes. You also noticed how his face mask had some kind of skull design painted on it.

"Business," he answered plainly, a man of few words you presumed. Somehow when he spoke, you were comforted by the smell of cigarettes on his lips and hints of brandy as they mixed in the air. "Me as well, but I always love coming here," you sighed. The bartender quietly came back with your drinks and you cheered the mysterious man next to you.

After savoring the liquor for a few moments he sparked up another conversation. "What is this? It's strong but good," he asked. "An Armagnac Aristocrat, bitter orange Lillet Blanc, and smokey Armagnac topped with a refreshing, crisp serving of ginger ale. C'est manifique" ("It's magnificent") you finished and gently placed the chill crystal glass on your bruised wrist.

"Well that is quite a description, I would guess you have these a lot," he joked and you could see the corners of his eyes crinkle as he smiled. "I'm a perfumer, my whole life is based on knowing the key elements to an ingredient and being able to illustrate it for others," you replied, practically telling your life story to this stranger.

After another long string of minutes, he spoke up again. "Makes sense why you're here, beautiful city," he said quietly. "Yes, it is. If you ever get a chance, a perfume tour would be worth your while." With that, he shook his head slightly and you knew this was a way of saying he was on his way out of the town.

"Next time, love, I appreciate the recommendation though." Maybe it was the inclusion of the nickname but you picked up on his British accent. London you thought, maybe Manchester, regardless it was as intoxicating as the liquor that was warming your insides.

As the time waned on, you ordered another drink. This time it was his recommendation, a Brandy Smash. Feeling slightly tipsy you joked, "Mhmm, I can taste the smokiness of the Armagnac with a subtle hint of cooling mint leaves and the sweet tang of sugar and lemon."

"And I would've thought perfumers are only good for the sense of smell," he replied. With his mask pulled up to his nose, you could see how beautiful his smile was. As you talked, his rosy lips formed into a calming curve and you could see some silvery scars dance in the bar's overhead light.

"I'm much more than that-" you stopped short. You realized after two hours of talking about yourself, you had not even asked his name. He noticed your hesitation and replied, "It's Simon."

Simon, meaning 'to listen' you thought to yourself, what a perfect name for a man who let you occupy his time with botanicals and knowledge of scents. "I'm Y/N," you said, "And thank you, Simon. This has been a perfect evening," you smiled gently.

"Yes it has, a perfect evening with perfect drinks," he replied and clinked his glass with yours. As he finished his drink, he slowly prepared to leave. He signaled the bartender over and you both paid your respective tabs. As he adjusted his jacket, something about Simon made you want to see him again. Maybe it was his chiseled features or his attentiveness to your words but whatever it was, it made you gently place a hand on his arm.

"I know this is a little forward but mind if I give you my number? Maybe I'll run into you here again or stateside?" you asked, preparing for rejection. This chance encounter was a plot device in movies, almost too good to be true. "Sure, love. Let's find you a pen," he said and pushed a napkin toward you.

"Puis-je avoir un stylo s'il vous plaît?" ("Can I have a pen, please?") you asked to the bartender who was polishing glasses. He slid one over to you and you wrote on the small red napkin you had been given. As you wrote on the napkin, you could feel Simon's eyes on you. He knew you were writing more than just a number based on the various lines written on the cloth.

You finished writing and leaned forward towards him, gently tucking the red item into his jacket pocket. If you had been any closer, you might have heard his rapid heartbeats and quickened breath. "Au revoir, Simon," you said and saw yourself to your hotel for the night, savoring the smell of jasmine and lavender in the air.

Simon took the napkin out of his pocket, the color reminding him of your sanguine cheeks and burgundy lipstick. His calloused fingers gently held the note as he read, "Pleasure to meet you, Simon. Thank you for listening and sharing a drink. Just a recommendation but a refined man like you should try, Gentleman by Givenchy. Until we meet again," followed by your number. He too walked out of the bar to embrace the late-night air. But as he walked the quiet streets, he now had a new appreciation for the intoxicating scents of Grasse.

#task force 141 x reader#task force 141#cod x reader#call of duty modern warfare#cod mwii#modern warfare 2#simon riley x reader#ghost x reader#simon ghost riley#call of duty#mw2 imagine#madebyizzie#mw2#izzie is writing

160 notes

·

View notes

Text

THIS DAY IN GAY HISTORY

based on: The White Crane Institute's 'Gay Wisdom', Gay Birthdays, Gay For Today, Famous GLBT, glbt-Gay Encylopedia, Today in Gay History, Wikipedia, and more …

September 3

1745 – Charles-Victor de Bonstetten (d.1832), a prominent individual in early Swiss gay history, was a writer and government official . It has long been speculated that Bonstetten, during his early twenties, was the object of affection of the homosexual English poet Thomas Gray .

In December 1769, the young Swiss aristocrat, living in London to improve his English, was introduced to the much older Gray. Shortly after this introduction, Bonstetten moved with Gray to Pembroke Hall, Cambridge, where he lived close to Gray's lodgings and spent his evenings in Gray's rooms. In a January 1770 letter to his confidante, Rev. Norton Nicholls, Gray wrote: "I never saw such a boy: our breed is not made on this model."

Bonstetten was obliged to return to Switzerland at the end of three months, but the two men were known to have corresponded regularly until Gray's death in 1771, although few of Bonstetten's letters have survived.

Bonstetten's best-known work is The Man of the North and the Man of the South; or the Influence of Climate (L'Homme du Midi et L'Homme du Nord, ou L'influence du Climat, 1824), an anthropological study of the influence of climate on human development.

Bonstetten went on to become the presumed lover of the Swiss historian and public official Johannes von Müller (1752-1809). Several love letters between Bonstetten and Müller have survived.

1792 – France: The head of Princess de Lamballe is displayed on a stick and paraded before the imprisoned Marie Antoinette. The two were thought to be lovers. Princess Lamballe was married at the age of 17 to Louis Alexandre de Bourbon-Penthièvre, Prince de Lamballe, the heir to the greatest fortune in France. After her marriage, which lasted a year, she went to court and became the confidante of Queen Marie Antoinette. She was killed in the massacres of September 1792 during the French Revolution.

1856 – Louis Sullivan (d.1924) was an American architect, and has been called a "father of skyscrapers" and "father of modernism". He was an influential architect of the Chicago School, a mentor to Frank Lloyd Wright, and an inspiration to the Chicago group of architects who have come to be known as the Prairie School. Along with Wright and Henry Hobson Richardson, Sullivan is one of "the recognized trinity of American architecture". The phrase "form follows function" is attributed to him, although he credited the concept to ancient Roman architect Vitruvius. In 1944, Sullivan was the second architect to posthumously receive the AIA Gold Medal.

Sullivan was born to a Swiss-born mother, and an Irish-born father, Patrick Sullivan. Both had immigrated to the United States in the late 1840s. He learned that he could both graduate from high school a year early and bypass the first two years at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology by passing a series of examinations. Entering MIT at the age of sixteen, Sullivan studied architecture there briefly. After one year of study, he moved to Philadelphia and took a job with architect Frank Furness.

The Depression of 1873 dried up much of Furness's work, and he was forced to let Sullivan go. Sullivan moved to Chicago in 1873 to take part in the building boom following the Great Chicago Fire of 1871. He worked for William LeBaron Jenney, the architect often credited with erecting the first steel frame building. After less than a year with Jenney, Sullivan moved to Paris and studied at the École des Beaux-Arts for a year. He returned to Chicago and began work for the firm of Joseph S. Johnston & John Edelman as a draftsman. Johnston & Edleman were commissioned for the design of the Moody Tabernacle, and had the interior decorative fresco secco stencils (stencil technique applied on dry plaster) designed by Sullivan. In 1879 Dankmar Adler hired Sullivan. A year later, Sullivan became a partner in Adler's firm. This marked the beginning of Sullivan's most productive years.

Adler and Sullivan initially achieved fame as theater architects. While most of their theaters were in Chicago, their fame won commissions as far west as Pueblo, Colorado, and Seattle, Washington. The culminating project of this phase of the firm's history was the 1889 Auditorium Building (1886–90, opened in stages) in Chicago, an extraordinary mixed-use building that included not only a 4,200-seat theater, but also a hotel and an office building with a 17-story tower and commercial storefronts at the ground level of the building, fronting Congress and Wabash Avenues. After 1889 the firm became known for their office buildings, particularly the 1891 Wainwright Building in St. Louis and the Schiller (later Garrick) Building and theater (1890) in Chicago. Other buildings often noted include the Chicago Stock Exchange Building (1894), the Guaranty Building (also known as the Prudential Building) of 1895–96 in Buffalo, New York, and the 1899–1904 Carson Pirie Scott Department Store by Sullivan on State Street in Chicago.

Like all American architects, Adler and Sullivan suffered a precipitous decline in their practice with the onset of the Panic of 1893. According to Charles Bebb, who was working in the office at that time, Adler borrowed money to try to keep employees on the payroll. By 1894, however, in the face of continuing financial distress with no relief in sight, Adler and Sullivan dissolved their partnership. The Guaranty Building was considered the last major project of the firm.

By both temperament and connections, Adler had been the one who brought in new business to the partnership, and following the rupture Sullivan received few large commissions after the Carson Pirie Scott Department Store. He went into a twenty-year-long financial and emotional decline, beset by a shortage of commissions, chronic financial problems, and alcoholism. He obtained a few commissions for small-town Midwestern banks, wrote books, and in 1922 appeared as a critic of Raymond Hood's winning entry for the Tribune Tower competition.

According to biographer Robert Twombley, though he never publicly identified as such, Sullivan likely also faced the challenges of being gay at a time when such an identity or orientation faced harsh social and legal stigma and sanction.

He died in a Chicago hotel room on April 14, 1924. He left a wife, from whom he was separated.

1950 – Doug Pinnick sometimes stylized as dUg Pinnick or simply dUg is an American musician best known as the bass guitarist, songwriter, and co-lead vocalist for the hard rock/progressive metal band King's X. He has fourteen albums with King's X, four solo albums, and numerous side projects and guest appearances to his credit. Pinnick is known for his gospel-like voice and his heavily distorted bass tone, played through multiple Ampeg SVT-4 amplifiers.

Doug Pinnick was born in Braidwood, Illinois. He grew up in a musical family where everyone either sang or played an instrument. He was raised by his great-grandmother, a devoutly religious woman, and was reared in a very strict Southern Baptist environment. He has seventeen half-brothers and sisters, from three mothers and two fathers.

When he was in grade school, Pinnick participated in choir and played saxophone. As a teenager, he listened to classic R&B and Motown artists such as Stevie Wonder, Little Richard, and Aretha Franklin. Pinnick sang in bands throughout high school, one of the earliest being a group called Stone Flower which he describes as "Chicago Transit Authority meets Sly & The Family Stone". While attending Joliet Junior College in 1969, Pinnick was inspired by hard rock bands such as Led Zeppelin and Jimi Hendrix. Around this time, he also started listening to perhaps his biggest influence, Sly & The Family Stone. His dream was to form a band that combined all of these varied influences.

At one point in the early seventies, Pinnick moved to a Christian community in Florida. There, he remained involved in the music business by promoting small shows by Christian rock bands. He soon grew tired of that and moved back to Illinois.

Pinnick soon became involved with guitarist Ty Tabor after seeing him play a concert at Evangel College in Springfield. Jerry Gaskill was later included and the band The Edge was born. In 1983, the band changed their name to Sneak Preview and released an independent, self titled LP. The trio evolved into King's X several years (and a move to Houston, Tx.) later.

In 1998, Pinnick came out as homosexual during an interview for Regeneration Quarterly. Diamante Music Group cancelled distribution of King's X material in Christian retail stores following this information becoming public knowledge. In recent years, Pinnick has revealed that he now identifies as agnostic, in contrast to his Contemporary Christian music past.

Pinnick had kept his homosexuality quiet with all but his closest friends.

"My friends and band mates accepted me anyway, although I hadn't even trusted them to, at first, When you grow up in a Christian environment, you believe everyone's going to hate you. But my friends all turned out to be very supportive. I didn't lose any. So I finally got to the point where Ty and Jerry told me, `Go ahead, be honest.'"

1959 – Merritt Butrick (d.1989) was an American actor, known for his roles on the 1982 teen sitcom Square Pegs, in two Star Trek feature films, and a variety of other acting roles in the 1980s.

Butrick was born in Gainesville, Florida, an only child. He attended the California Institute of the Arts for acting, but was dismissed from the school.

His first screen role was as a rapist in two 1981 episodes of the police drama Hill Street Blues.

He was cast as "Johnny Slash" Ulasewicz, a major supporting character in the 1982 teen sitcom Square Pegs, which received critical praise but was cancelled after 19 episodes (one season). The character was described by one critic as an "apparent (but never declared) gay student."

While Square Pegs was in pre-broadcast production, Butrick was cast to play David Marcus, the physicist son of James T. Kirk (William Shatner) and his former lover Carol Marcus (Bibi Besch), in Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan. He continued the role in the follow-up film Star Trek III: The Search for Spock, in which the character was killed. He later appeared as T'Jon, the captain of a cargo vessel rescued by the crew of the Enterprise in "Symbiosis", a 1988 episode of Star Trek: The Next Generation.

Meanwhile, he appeared in the 1982 comedy film Zapped!, the 1988 horror film Fright Night II, and as Barbara Hershey's hillbilly son in the 1987 drama Shy People. He had a variety of guest roles in television series and television movies.

He received critical praise from Time magazine for his performance at the Los Angeles Theatre Center in the play Kingfish, in which he played a ditzy, petulant muscle-boy prostitute. It was his last acting role.

Butrick died of toxoplasmosis, complicated by his AIDS, on March 17, 1989, at the age of 29. He has at least two panels dedicated to him as part of the NAMES Project AIDS Memorial Quilt, both referencing his role as David Marcus.

Some sources state that in his private life, Butrick was gay. Kirstie Alley, his co-star in Star Trek II, identified Butrick as being bisexual.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Suggestions for Tumblr's next book club

With Dracula Daily on the horizon again, I've been pondering what other out-of-copyright novels we might like to consider reading very slowly. Here are my ideas! And if any of them already exist, lmk.

North and South

Author: Elizabeth Gaskell

Year of publication: 1854-55

Length: 185,000 words, 52 chapters. So we could have a chapter weekly for a full year.

Summary: Margaret Hale is forced to leave the rural south of England and settle in the rough, industrial north. There she clashes with mill-owner John Thornton over his treatment of his workers...

Why Tumblr would like it: Enemies to Lovers! Class struggle! Fascinating historical context! Honestly, it's a great read.

Evelina

Author: Fanny Burney

Year of publication: 1778

Length: 157,000 words in 84 letters. That's right, it's epistolary, and the letters are almost all sent March to October of the same year, so we could read this one in true Dracula Daily fashion.

Summary: Evelina is the sheltered daughter of an aristocrat trying to make her way in the world of late 18th-century society.

Why Tumblr would like it: Evelina is a likeable, relatable character. I think it'd be fun to get emails from her.

The Well of Loneliness

Author: Radclyffe Hall

Year of publication: 1928

Length: 158,000 words in 56 chapters.

Summary: The story of Stephen Gordon, a girl who realises at an early age that she's a lesbian, and her attempts to find love in the early 20th century.

Why Tumblr would like it: It's one of the most iconic lesbian novels of the 20th century!

The War of the Worlds

Author: HG Wells

Year of publication: 1897

Length: 63,000 words in 27 chapters.

Summary: Alien invaders land from Mars and fuck up the south of England.

Why Tumblr would like it: Alien invaders land from Mars and fuck up the south of England, come on, what's not to like?

The Moonstone

Author: Wilkie Collins

Year of publication: 1868

Length: 200,000 words (so a bit of a marathon) in 51 chapters.

Summary: A young English woman inherits a large Indian diamond of dubious provenance on her 18th birthday. Then it gets stolen!

Why Tumblr would like it: One of the first detective novels, and supposed to be one of the best, it's a page turner with lots of suspense, twists and cliffhanger endings.

The Mysterious Affair at Styles

Author: Agatha Christie

Year of publication: 1920

Length: 60,000 words in 13 chapters.

Summary: The first murder mystery starring Hercule Poirot.

Why Tumblr would like it: Look, you liked Glass Onion, right? And if you like this, Agatha Christie's novels are emerging from copyright at the rate of about two per year.

Les Misérables

Author: Victor Hugo

Year of publication: 1862

Length: 570,000 words in the English translation (ouch) in 365 chapters.

Summary: A vast, sweeping story of poverty, justice and revolution in early 19th century France.

Why Tumblr would like it: Well, if you thought Moby Dick didn't have enough digressions...

The Canterbury Tales

Author: Geoffrey Chaucer

Year of publication: 1387-1400

Length: 24 stories averaging 700 lines each.

Summary: Some pilgrims are heading to Canterbury. They tell one another stories to pass the time. These are their stories.

Why Tumblr would like it: I mean, there's a reason we still read these 600 years later. They're a fascinating insight into medieval life, but they're also - for the most part - just good fun.

If you love any of these suggestions and would really like to see it take off, reblog to help make it happen.

#tumblr book club#north and south#evelina#the well of loneliness#the war of the worlds#the moonstone#poirot#les miserables#the canterbury tales

117 notes

·

View notes

Text

My non-fiction/true crime/French history book, Screaming At The Window (the tragic story of Blanche Monnier, the Prisoner of Poitiers), is published on September 17th by @kernpunktpress

Screaming At The Window is the reconstruction and the retelling of a true case of imprisonment that took place at the end of the nineteenth century. Based on details and information reported in contemporaneous newspapers, Screaming at the Window is the true and tragic story of Blanche Monnier, the young woman who became known throughout France as The Prisoner of Poitiers (La Séquestrée de Poitiers).

Just before her twenty-fifth birthday, Blanche Monnier was imprisoned in an upstairs room by her mother and her brother. In May 1901, an anonymous letter alerted the police to the fact that Blanche, the daughter of Louise, an aristocratic mother and Ėmile, a former dean of the faculty of letters, was imprisoned in a dark room with padlocked shutters. According to the letter, Blanche had been imprisoned for twenty-five years. When the police found her, she was half-starved, naked, sedated and screaming.

Part French history, part true crime study, part courtroom drama, Screaming At The Window is Blanche Monnier’s harrowing story.

Book details:

Title: Screaming At The Window

Subtitle: The tragic story of Blanche Monnier, the Prisoner of Poitiers

Author: R J Dent

Language: English

Format: Paperback

Genre: True Crime/French History

Publisher: @kernpunktpress

Publication Date: September 17th 2024

#Blanche Monnier#La Sequestree de Poitiers#The Prisoner of Poitiers#true crime#French history#courtroom drama#KERNPUNKT Press#non-fiction#www.rjdent.com

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

back back back again with the lafayette content (lafayette pt. 5)

you know the drill, here's pt. 4, gay people

Where we left off, Lafayette had just had a very exciting campaign in Rhode Island (the most exciting thing to ever happen in Rhode Island), but now what? Nothing. Nothing is happening. I'm not joking, he was bored for several months.

So, here's the real question, how would you, as a little French man in America who somehow obtained the title of major general, handle your boredom? Correct! You would duel Lord Carlisle, the head of the British peace commission.

Or at least, you'd try. Lafayette challenged Carlisle, but Carlisle fucking ignored him. Because obviously.

So when that fell through, Lafayette decided to just. go home. Not permanently, but for a visit. I mean, he was only gone for like a shit ton of time, and had left behind his pregnant wife without a real explanation, and in that time his eldest daughter, Henriette, had DIED. So, it was about time to go home. And when he was contemplating this, he checked how much money he had left, and realized he was broke and was like yeah it's time to go home.

In addition to this, he also wanted to apologize to the king since he kinda fled the country against direct orders and nearly started a war with England. One of Lafayette's main goals in life was to fight under the French flag, and he couldn't really do that unless the king liked him. So, he got a letter of recommendation and the promise of a ceremonial sword from Benjamin Franklin, and headed home to France.

Back, back, back again (in France)

Everyone was SO HAPPY to see Lafayette in France, and I would be too. Lafayette went to Versailles and was like "heeyyy King Louis XVI, my favorite king of all time, I'm really sorry for fleeing the country despite direct orders not to and nearly starting a war with England, do you forgive me?" and King Louis XVI put him on house arrest. But, to be fair, that is a very mild punishment, considering what he did was somewhat akin to treason.

Also, fun fact for the frev/Marie Antoinette girlies who know about her relationship with Lafayette during the French Revolution, she actually intervened on his behalf, which allowed him to buy a command of a regiment of the King's Dragoons! Which is like a huge favor because that command cost him 80,000 livres, which in modern US dollars is what the scholars call a shit ton.

This new popularity in France allowed him to aid the American cause in France by corresponding with French and American dignitaries, advocating the wants and needs of one side to the other. He actually played a vital role in this area, and John Adams, who did absolutely fuck all, got jealous and started beef with him for no fucking reason.

Lafayette didn't forget about his military ambitions, and was apart of a plan to attack the English mainland with John Paul Jones. This didn't work out and Lafayette was greatly disappointed (again), but it would never have been supported by France, so idrk what they expected. Fun fact, this was one of the many ideas Benjamin Franklin and Lafayette came up with together, along with a kinda gruesome children's book.

In the meantime, Lafayette daydreamed about being sent back to America in charge of the French naval forces he helped to negotiate. As you expected, he was very disappointed when they were put under the command of Rochambeau, who was just overall more qualified for the job.

While he was in France, he engaged in some ~aristocratic adventures in the arts and sciences~, and that's not an innuendo, he almost joined Franz Mezmer's cult. This is, actually, the first of two times he almost JOINED A FUCKING CULT. The second time was an Amish cult. So. There's that.

(If necessary, I can employ my boyfriend to explain how Lafayette was exactly the kind of person to get roped into a cult.)

In America Again! (This time it's Serious)

Lafayette returned in a bleak season of the war in which many of the Continental officers (Washington included) were itching for a major engagement with the British, and planned a French-American attack at some large British occupied area, hopefully with a good port.

The ideal place seemed to be New York City, and Lafayette was fixated on that. He was hoping he could have a major command in the attack. And, you guessed it, was super disappointed when he was ordered to march to Virginia to join General Greene. He was present for most of the Virginia campaign, and his main target was the traitor, Benedict Arnold.

PLOT TWIST that major attack was never in New York, but would actually be at Cornwallis' station in Yorktown, Virginia. Lafayette commanded the major Continental infantry forces that kept Cornwallis pinned at Yorktown while the commands under Washington, Rochambeau, and Admiral de Grasse surrounded him in a violent siege.

The one catch-up was that the trenches they were digging couldn't fully surround the British reinforcements due to two redoubts, 9 and 10. Lafayette's American command (led by Colonel Alexander Hamilton with his own command and Colonel John Laurens with a division under Greene) partnered with a division under Rochambeau to attack the redoubts, which led the British to surrender.

One of my favorite little details about the Revolution is that, at the surrender, the British troops refused to look at the American soldiers, so Lafayette told his band to start blasting Yankee Doodle to get their attention. Absolute icon.

I'm gonna cut this one a little early since this is the end of Lafayette's involvement in the American Revolution, and the French Revolution will require WAAYYY more attention. See you in part 6, gay people

#lafayette#marquis de lafayette#alexander hamilton#john laurens#history#amrev#george washington#american history#amrev history#american revolution#do it for richie 💪

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

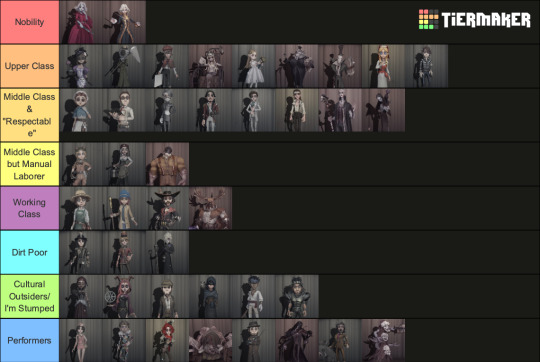

Social Class and Income Levels of IDV Characters

I’m back again with a long, intensive IDV post, this time regarding the quality of life most of Identity V’s characters would likely have led before coming to the manor. This list is not definitive and is based on a little guesswork in some areas, and also doesn’t include every single character, as I couldn’t find relevant information for every career, but I think provides an interesting look at character backgrounds, the sorts of resources they would have access to, and what life was like in the 1890s.

This post assumes that the vast majority of the characters live in the United Kingdom and that most of them were born there. As discussed in an earlier theory post, Oletus Manor is 100% in England and the DeRoss Couple and their daughter were English aristocrats. It also refers to fairly readily available information that can be found in various characters’ deduction systems, seasonal events, background and official videos, and birthday letters.

Lots- and I mean LOTS- of info below.

First, a few notes about the class system in the late Victorian United Kingdom:

- Class was highly stratified, and moving up the social ladder was extremely difficult.

- Class was not necessarily just tied to income. Upbringing, family background, etc were just as large a determinant, which is why you might have an impoverished aristocrat with tons of property but no income who would still be welcome in elite social circles, whereas an up-and coming business owner bringing in £3,000/year would be shunned. Class was who got invited over to dinner; class was whether or not you’d been educated, and if you had to work with your hands.

The Upper Class/Aristocracy/Nobility:

- The top of the class system under the royal family (boo). Men might hold political positions, but members of this class would not have careers, as such. These characters likely have a passive income from investments or land owned and generational wealth. hey own one or more homes and employ extensive live-in household staff, including maids, butlers, drivers, cooks, gardeners etc.They can travel widely and partake of various entertainments, having time to cultivate talents in the arts.

Mary: She is, or believes herself to be (??), Marie Antoinette, an Austrian princess and the Queen of France. Antoinette was infamous for her lavish lifestyle and voracious appetite for fashion.

Joseph: He is referred to as a Count, but French nobility does not actually use that exact title. It’s possible he is a Comte, which is the equivalent of an Earl/Count in England. Either way, this is a middle of the ranking noble title. In the 2021 Christmas Event, he mentions his family owning several manors, so the Desaulniers family has, or had, a considerable amount of property.

An interesting thing that makes me wonder if his family’s wealth is depleted is that he consistently dresses in extremely outdated clothing, but I believe that speaks more to his sentimental obsession with the past than anything else.

Chloe/Vera: The real Vera had the capital to open a store front to sell Chloe’s perfumes. There is no mention of either daughter working prior to this, and the family employs several maids. Presumably, Chloe’s perfumes were a good money maker, as the 1890s marked the “Golden Era” of perfume production and sales. It is unusual, but not impossible, that an upper-class woman would own a business.

Melly: A successful social climber who began as a maid before marrying her employer, who owned a manor. She is well educated, to the extent she has been invited to lecture at a college or university.

Edgar: Edgar does not paint to generate income. His family was able to afford a long-term art tutor for him, and he is not interested in the prize money offered by the manor because his family’s wealth is more than sufficient. He is squarely in the aristocrat category, and enjoyed a lifestyle most of the other characters could only have dreamed of, at least in a fiscal sense.

Galatea: Another individual who pursued art as a passion or hobby rather than actual trade.This would simply not be realistic for anyone outside the upper classes.

Memory/Alice DeRoss: Her father possessed the title of Baron. Her mother is depicted in TOR with an upper-class English accent. Her parents own Oletus manor, which they were able to purchase, and employ two known servants (Burke and Bane). Running such a large estate would require an army of maids, cooks, gardeners, etc, who are not directly mentioned but implied.

Keigan: In her background video, we see her family in very formal dress at a large, lavishly set dinner table. Her brother holds the position of judge at a major court, which brought with it a great deal of respect and import. The average clerk made very little money, but it’s implied she is acting as his unofficial assistant/helper due to sisterly obligation, and does not want for money.

Jack: a bit of conjecture, but Jack at least played at being an artist, and takes on the role of a gentleman. It does not appear he needed to work to support himself.

Annie: Her father is a painter of some note, and her mother was a noted society beauty who left her a considerable inheritance that her father and fiancé conspired to get their hands on.

Luca: A fallen aristocrat with a mother of noble birth. His interests include piano, books, and experiments, all of which point to a privileged upbringing. Only someone with resources could run experiments and futz about with specialized equipment, which is why so many scientists from past eras came from upper class or even noble backgrounds. His father, Herman, blew through their fortune, and after Luca’s incident with Alva, he would not be a socially accepted individual.

The “Educated” Middle Class:

-Individuals or households with an income up to around £1000/ year. The wives do not have to work, but see to the home (oversee staff) and partake in social obligations, plan parties, and help educate the children in the arts. Daughters may become teachers or governesses if they don’t marry or prior to marriage, or in wealthier families, not work at all. They own their home and have live-in staff, such a cook and maids. ( see model yearly budget for a man making £700/year here.) Vacations, domestic and abroad, and high-end entertainments are accessible. They have some time for hobbies, and probably play a musical instrument if also from a culturally upper-middle class family, such as a piano, violin, harpsichord, etc. Guitars, flutes etc would not be counted here, as they are more “common” instruments. These individuals might move in some of the same social circles as the aristocracy.

Emily: A well established Doctor working in a city hospital could expect to make up to £1000/ year, putting them at the upper end of the middle class. However, an independent Doctor would make much less, and in rural areas, would often be paid in food or services. Given Emily’s difficulties keeping her clinic open, she lingers in the border between being a member of the middle class “culturally”— we know she came from a middle class family and is educated— but she struggles with money and lacks for stability like some of the folks in the lower middle and many in the working classes. Despite a low income, her education would mean she’d be welcome in polite society.

Freddy: A top-payed Lawyer could make £1,200/ year, but Freddy is a bit of a failure. His actual financial status cannot be determined, but he is, like Emily, culturally middle class due to his education and white-collar job.

Aesop: Aesop Carl? relatively loaded, actually. The Victorian era was great for the funeral industry. The elaborate rituals surrounding mourning meant that those in adjacent careers were always busy, and it was fashionable to send off a loved one in great style. The lower classes imitated the lavish funerals of the wealthy, often bankrupting themselves in the process, because it was considered shameful to be unable to lay someone to rest properly, and reputation and respectability were of vital importance in the Victorian United Kingdom.

As with today, there was an outcry about the funerary industry driving up prices and taking advantage of grieving people to line their pockets even more.A nice funeral, modest but respectable, cost about £11, and embalming services were an additional £10. A funeral with all the bells and whistles would fall at £21. A skilled Embalmer is capable of tending to several corpses in a day. Even if Aesop and Jerry only handled 50 corpses a year, they’d be making £500. A modern mortician handles about 150 bodies a year, so that’s a cool £1500/year for them. This would mean a nice house with a garden, a maid, and a cook at the very least, presuming Jerry risked having staff around that could possibly catch him on his bullshit. (Though I guess he could just kill them too and replace them with someone who didn’t know better. Fucking Jerry). At least even if he was emotionally starved and groomed into becoming a murderer, he was still eating well, could have nice clothes, and take vacations?

Another downside though is that then as is often true now, people did not want to socialize with someone who worked closely with dead bodies, and funeral industry workers were often ostracized, making his position here a little tenuous.

His mother’s family appears to have been upper or middle class, as suggested by Aesop’s dance emote, in which he performs a pirouette. Ballet was an upper-class entertainment, and formal dance training would not be accessible to children of poorer families, and I doubt Jerry was enrolling him in a lot of extracurriculars, meaning he must have learned while still in his mother’s care.

Jose: A First Officer could make around £900/ year. His family was employed by the Queen, and once had a stellar reputation. Although sailors worked with their hands, a high-ranked officer on a ship was seen as fairly respectable.

Orpheus: Some conjecture here. Orpheus is, like Melly, someone who successfully moved up the social ladder, first being adopted by the aristocratic DeRoss couple and then making a name for himself as a novelist. His Survivor version is well-dressed in neat white clothes that would require maintenance and be antithetical to manual work that would dirty them.

Luchino: As a professor, he is educated and respectable, even if his methods are unconventional and his manner of dress hardly appropriate for the classroom.

Alva: He was a student together with Luca’s father, Herman, at an institute of higher education, meaning he is most likely from a family who could afford the expense of educating him.

EDIT: @ivy0309 pointed out that in the Mandarin version of Alva’s first deduction, the language states he comes from an impoverished place, meaning he was probably granted a scholarship and is another case of a successful social climber.

Ann: Ann’s deductions mention she wore exquisite and ornate mourning clothes after the deaths of her parents, suggesting her family had the money for funerals with pomp. She is also left land and at least two houses after her father’s passing.

Manually Laboring Middle Class:

Income wise these careers are middle class, being able to net £1000/year, but there was a difference between enjoying a good quality of life and being socially accepted. Iif you worked with your hands, no matter how skilled you were, you were still a laborer and seen as lacking in culture.

Tracy: A clockmaker made up to £400/year, which jumped to £840/ year if they also worked on watches as well. Her father, Mark, would have netted them enough money to fall into the working middle class, and this is before Tracy’s mechanical genius became evident. If Tracy’s life had gone differently, it is possible she could have become what was known as a Master Mechanic, a skilled worker who could earn £1000/ year, guaranteeing a high standard of living.

Demi: As a Barmaid alone, Demi would make about £150/ year, which would be difficult to survive on; however, she and her brother own their establishment. Their bar could make about £1000/ year, giving them a comfortable life in terms of amenities, but Barmaids were not respected and often suspected of being easy; many young women in major cities who worked in shops and restaurants took up sex work to supplement their meager incomes.

Leo: At one point appears to have owned two factories, both his initial textile factory and the doomed arms factory.

More or Less Stable Working Class

Emma: A gardener would make, at a maximum, £400/ year, and a young gardener like Emma would certainly not be able to earn that much. In her previous life as Lisa Beck before Leo made a bad investment, she was likely very comfortable, as Leo did own a presumably successful textile factory. She may be especially nostalgic for her childhood with her father because her situation changed drastically very rapidly, going from living in a pleasant environment with two parents, plenty of toys, good food and clothes/household with a steady income, to being placed in a Victorian orphanage and eventually becoming a manual laborer.

Helena: She wishes to attend college, but cannot afford to do so. We aren't exactly sure what her father does for work, but he is likely in the working class, as many middle class families could reasonably afford to educate at least one of their children, and Helena is, to our knowledge, an only child. They seem to have enough money to provide her with certain accommodations, like spectacles and her cane, though these may have been gifts from Sullivan.

Kevin: the lifestyle itself would be rough, but he could make around $480/year (sorry for the currency change, but he lived and worked in the USA, and England did not have cowboys).

Bane: A game keeper often had a relatively low income and would by that definition actually fall into the below category, but housing was almost always provided to men who held this job, taking a stressor off his plate. Steady employment/staying at a position for several years was also common, providing general stability.

Working Class and Extremely Poor:

-Families or households often struggling to scrape by on under or around £300/ year, sometimes with individuals making as little as £25/ year. A frugal family at the top end of this budget would overlap with lower middle class and would be able to employ a maid, putting appearances first and sacrificing other luxuries. There is less money for entertainment, and almost all of the income goes to food and housing. Little or no savings. The vast majority of the population falls in this category because things never change, with only 7.7% of workers making £340 or above, and 42.9% £192 or under.

Norton: Coal miners earned around £260/ year. Norton was looking for gold and gems, but it’s safe to assume his standard of living would have been about the same as a coal minder. Compared to some jobs, this wage may have seemed decent, but mining was brutal and incredibly dangerous. Miners typically lived in housing camps operated by mine owners, and had to buy their daily essentials from in-camp stores and commissaries.

Victor: I had to conjecture a little here, but senior postal service employees were making around £200-300/ year, and newer employees a starting annual wage of £90 so we can guess Victor falls around here as well. We also do not know about his family’s class background.

Andrew: Andrew probably wishes he really was a Train Conductor. In that job, he could have made £900/ year, granting him membership the middle class. Being a Grave Keeper or Grave Digger was an awful job, physically demanding and badly compensated. Cemeteries often stank of rotting bodies, and Grave Diggers had a low social standing because they worked so closely with corpses. I could not find concrete information about how much he would have made, but it would definitely fall below the £300/year mark that is the ceiling for entry into the lower middle class, given that the other Survivors with physical/ unskilled labor jobs seem to peak at the £200ish range.

Worth noting though not necessarily tied to class is the common misconception that Andrew is illiterate, which he certainly isn’t. His dedications include a diary entry he wrote in which he tries to justify to himself his bodysnatching activities, and he also received letters from Percy’s assistant. He might have a little trouble with small print due to his bad eyesight, but he can absolutely read and write. Most people, even the poorer classes, were at least somewhat literate in this period in the United Kingdom.

Outsiders/I Have No Idea

-These are characters with either extremely vague and mysterious pasts or who have extremely unconventional professions.

Patricia: A Voodoo practitioner, it is unclear if she performs the work of a Voodoo priestess, which could be lucrative. Marie Laveau, on whom she is allegedly loosely based, was very financial successful, but to be honest, I think the IDV writers have a very shaky grasp on actual Voodoo practices and beliefs (as do most folks probably who have no idea that a lot of practitioners are also Catholic. It's a syncretic religion so yes, Patricia’s nun costume actually makes some sense.)

Fiona: It is openly stated she comes from an unknown class. There aren’t really historical precedents I could find in my research for occultists of her stripe earning an income, as there’s no indication she goes around giving exhibitions or overseeing seaances. Many Victorians dabbled in the arcane as a hobby, but those who were able to fully devote themselves to their studies tended to come from very comfortable backgrounds, such as Helena Blavatsky and Aleister Crowley.

Kreacher: He is a thief. Nothing else to say.

Eli: Another character with an ambiguous background. We have little information about his family life, but he is considered in his write-up by the organizers of the manor games to be unemployed.

EDIT: @ivy0309 informed me Eli is listed as coming from a middle class background in the official setting book.

Ganji: He is likely extremely poor. I could not find anywhere what a professional athlete might have been paid, but we do at least know he cannot afford travel home to India.

William: He is presumably from a middle class family, given that he attended university. As with Andrew above, I have a seen of lot people claiming William is less intelligent/educated than he is, when he’s actually at least one of the most educated characters in the game. He may have made a poor decision drinking the poisoned wine and come off as a muscle head, but he is far from a himbo. I don’t know what his current social class could be considered, as professional athletes in the Victorian era were not the same was they are now, but William does appear based on his clothes to be a rugby player more or less full time?

Performers/Entertainers

-This is another tricky group to get a handle on, because the role of the entertainer in society meant that one could be exalted and idolized while also not being welcome in polite society. I cannot speak to actual income amounts for these characters, but can provide a few general notes of interest. Also worth noting is that a top-billed musician like Antonio would be treated very differently than the Hullabaloo performers, who were certainly seen as impolite and indecent.

Margaretha/Natalie: Female performers were often characterized as promiscuous and sexually available, and therefore sneered at. Margie is wearing the costume of an exotic dancer (for those who may not be aware, this doesn't meant actually foreign or exotic, it explicitly means a dance intended to arouse or excite). She is not doing well fiscally after Sergei’s death, and is implied by the description of her animal tamer costume to dance/busk for tips.

Her uncle and aunt who raised her lived in Lakeside, and Natalie is described as wearing a cheap cotton dress in a photograph of her living under their care. Her background then would likely fall under manually laboring/working class.

Mike: Mike is one of the circus’ most popular performers, so he makes more than Margaretha, but that's all I can guess.

Joker: He is less popular than Mike and Sergei, but is allowed his own tent because either he has enough status in the Hullabaloo or nobody wants to room with him.

Violetta: Her family abandoned her, and she was seen as an asset by Max. Likely has little to no money of her own.

Servais: He at least considers himself middle class and respectable, and his dress does suggest he is financially solvent.

Antonio: A musician welcomed at court who played for upper-class audiences. Antonio was raised to be a money-maker by a stern father and did receive royal patronage, but based on his personality traits I am willing to bet he has poor money management skills. His real-life inspiration, Niccolo Paganini, died in debt.

Murro: Treated as a possession by Bernard and then living on the run, it's hard to imagine he had any way of earning money after fleeing the circus, nor the necessary knowledge to exist within society.

Willis Brothers: I believe their situation would be similar to Violetta’s. Disabled sideshow performers could occasionally have quite lucrative careers, but this was rare.

This is far from comprehensive, but thank you so much for taking the time to read this far! If you have any questions or wish to discuss anything here, please feel free to talk to me!

A great resource for approximating the income ranges used above is this database, this is invaluable for looking at things like average wages, housing costs, price of goods in different countries (mostly the US, UK, and Western Europe) across decades and eras.

#identity v#idv#idv lore#idv speculation#William Ellis#Fiona Gilman#Edgar Valden#Melly Plinius#Norton Campbell#Servais LeRoy#Patricia Dorval#Annie Lester#Aesop Carl#Victor Grantz#Ganji Gupta#Eli Clark#Kreacher Pierson#Alva Lorenz#Luca Balsa#Emma Woods#Emily Dyer#Joseph Desaulnier#Vera Nair#Galatea Claude#Alice DeRoss#IDV Keigan#IDV Jack#Freddy Riley#Jose Baden#IDV Orpheus

376 notes

·

View notes

Text

My Presentation on 93

Professors, friends, and esteemed guests,

I have the honour to present to you today an unparalleled book: Ninety-Three by Mr. Victor Hugo, whom we all recognise as a giant—not just of French letters, but of the world. To our great shame, although other works by Mr. Hugo are frequently read today, Ninety-Three, his last novel, has been largely forgotten; indeed, at this present moment no reputable publishing company is printing it in the English language.

I am here for the express purpose of reviving Anglophone interest in Ninety-Three. I consider this book a work of French Romanticism par excellence, for several reasons. First, it is an exercise of Hugo's literary theory, set forth as early as 1827 in the Preface to Cromwell, though never until now so perfectly demonstrated; second, in it we see the author’s reflections on a momentous point in history, the French Revolution, itself full of dramatic and philosophical potential. Additionally, the book is well-paced— which is perhaps the most difficult achievement of all for a work of this author. In sum, this book has everything that is required for a novel to ascend to the literary pantheon of the western canon: it has drama; it has depth; it is entertaining; it is true. Let us hasten, then, to place it where it deserves to be.

To understand the genius of Ninety-Three, one must understand the symbolic significance of its characters. But before I go any further, let us provide a general idea of the plot. In one sentence, it is a tale of the struggle between republicans and royalists in the Vendée (that is, Brittany), during the height of the Reign of Terror—hence the name, which is short for Seventeen Ninety-Three. Hugo divides the novel into three parts: At Sea, In Paris, and In la Vendée.

The story begins with a sort of prologue, an encounter between the republican Battalion of the Bonnet-Rouge and a Briton peasant woman and her three children, who are fleeing the war. They are quickly adopted by the battalion. We shall soon see why they are important. For the present our attention is redirected to the island of Jersey, an English possession, where a French royalist crew is preparing for a secret expedition. An old man boards the ship. He is in peasant dress, but by his demeanor seems to be an aristocrat. In the rest of At Sea we become acquainted with this jolly royalist crew—only to see them all perish in a naval battle before they ever reach the coast of France. Yet the old man escapes with the sailor Halmalo, and they land in Brittany in a little rowboat. He sends Halmalo off to rouse a general insurrection. Then, upon reading a placard, learns that his presence in Brittany has been known, and that someone named Gauvain is hunting him down, which sends him into a shock. Despite his dire situation, our protagonist is recognised by an old beggar named Tellemarch, who conceals him. We discover that he is none other than the Marquis de Lantenac, Prince in Brittany, coming back to lead the rebellion.

In the second part, In Paris, we are introduced to another character: Cimourdain. Cimourdain is a revolutionary priest, a man of iron will, with one weakness only: his affection for a pupil he had long ago, who was the grand-nephew of a great lord. At this period, however, Cimourdain dedicated himself completely to the revolution. Such was his formidable reputation that Cimourdain was able to intrude upon a meeting of the three terrible revolutionary men, Danton, Marat, and Robespierre, and cause his opinion to prevail among them. Robespierre then appoints Cimourdain as a delegate of the Committee of Public Safety, and sends him off to deal with the situation in Vendée. He is told that his mission is to watch a young commander, a ci-devant noble, named Gauvain. This name also sends Cimourdain into a shock.

Gauvain, in fact, is none other than the grand-nephew of the Marquis de Lantenac, in whose household the priest Cimourdain had been employed. Although they have not met for many years, there is a close bond between the master and pupil, and both adhere to the same revolutionary ideal. Hugo has set the stage. In the last part, In la Vendée, these epic forces are hurled against each other in the siege of the Gauvain family’s ancestral castle, La Tourgue. On the one side, we have the republican besiegers, Gauvain and Cimourdain, and on the other, the Marquis de Lantenac and his Briton warriors, the besieged. The Marquis has one last card to play: he has, as hostages, the children of the Battalion of the Bonnet-Rouge. For the safety of his party, he offers the life of the three children, whom he has placed in the chatelet adjoining the castle of La Tourgue, which will be burned upon attack. The republicans refuse. The siege begins, bloody for the republicans, hopeless for the royalists. At the last moment, by a stroke of fate the royalists contrive to escape, leaving behind an exasperated republican army, and a burning house. The republicans try to rescue the children, but find this impossible, as they can neither scale the walls of the chatelet, nor open the iron door that leads to it. As this is happening, the Marquis hears the desperate cries of the mother in the distance. Beyond all expectation, he returns, opens the door with his key, steps into the fire, and saves the children. Thereupon he is seized by Cimourdain, who proclaims that Lantenac will be promptly guillotined. Yet unbeknownst to Cimourdain, Lantenac’s heroic act of self-sacrifice set off a crisis of conscience in the gentle Gauvain, who fought for the republic of mercy, not the republic of vengeance. The final battle takes place in the human heart.

I will not divulge the ending. Already we can see that these characters are at once human, and more than human. “The stage is an optical point,” says Hugo in the Preface to Cromwell, ���Everything that exists in the world—in history, in life, in man—should be and can be reflected therein, but under the magic wand of art.” Men assume gigantic proportions. They become ideas. The three central characters each represent a force. In the lights and shadows of their souls, we have symbols of the lights and shadows of a whole age. The fifteen centuries of feudalism, the Bourbon monarchy, the France of the past, when condensed into an object is the looming castle La Tourgue, and when incarnate is Lantenac. The twelve months of the revolutionary terror, the Committee of Public Safety, the France of the moment, is as an object the guillotine, as a man Cimoudain. The immense future is Gauvain. Lantenac is old; Cimourdain middle-aged; Gauvain young.

Let us look at each of these characters in turn.

I admit that Lantenac is my favourite character. In his human aspect he is impressive, and very compellingly written. Almost immediately upon introduction, he manifests a ferocious justice in the affair of Halmalo’s brother, a gunner who endangered the whole ship by his neglect, and who saved it in a terrifying struggle between vis et vir, between an invincible brass carronade and frail humanity. Lantenac awarded this man the Cross of Saint-Louis, and then had him shot. To the vengeful Halmalo, his justification is this: “As for me, I did my duty, first in saving your brother’s life, and then in taking it from him [...] He has failed his duty; I have not failed mine.” This episode sums up Lantenac’s character. True to life and true to the principle of romantic drama, Lantenac contains both the grotesque and the sublime, sometimes even in the same action. Like the Cromwell that inspired in posterity such horror and admiration, he shoots women, but saves children. He martyrs others, but is at every point prepared to be the martyr.

As an idea he is the ultimate embodiment of the Ancien Régime. Though himself unpretentious, Lantenac is perfectly aware of the role he must play. He demonstrates perfectly, unlike conventional aristocrats in literature, the principle of noblesse oblige and the justice of the suum cuique. He believes that he is the representative of divine right, not out of arrogance, but as a matter of fact. “This is the question,” he tells Gauvain in their first and last interview, “to be a Great Kingdom, to be the ancient France, [is] to be this magnificent land of system [...] There was something fine and noble in this system. You have destroyed it [...] like the miserable ignoramuses you are [...] Go! Do your work! Be the new man! Become pygmies! [...] But leave us great.” The force which animates Lantenac is his duty, merciless, towards the old monarchical order—until the principle was overcome by the man, who was still able to be moved by helpless innocence.

The first thing that Hugo felt it was necessary to know about Cimourdain is that he is a priest. “He had been a priest, which is a solemn thing. Man may have, like the sky, a dark and impenetrable serenity; that something should have caused the night to fall in his soul is all that is required. [...] Cimourdain was full of virtues and truth, but they shine out against a dark background.” There is an admirable purity about him: it is symbolic that we always see him rushing into the thick of battle, but never firing his weapon. He aids the poor, relieves the suffering, dresses the wounded. By his virtues he seems Christlike, but unlike Christ, his is an icy virtue, the virtue of duty, not love; a justice which knows not mercy—“the blind certainty of an arrow,” which imparts to this sublimity a touch of the ridiculous. It is a short step from greatness to madness. Still, there remains some humanity in Cimourdain, on account of his love for Gauvain. Through this love that he is able to live, as a man, and not merely as the mechanical execution of an idea.

On the surface Cimourdain has renounced his priesthood. But, Hugo reminds us, “once a priest, always a priest.” He is still a priest, but a priest of the Revolution, which he believes to have come from God. There is a similarity between Cimourdain and Lantenac, though they are on the two diametrically opposed sides of the revolution. Both are bound by duty to their cause. Both are ferocious. When Robespierre commissioned Cimourdain, he answered: “Yes, I accept. Terror against terror, Lantenac is cruel. I shall be cruel. War to the death against this man. I will deliver the Republic from him, so it please God." Quite appropriately he is represented by the image of the axe—realised in the guillotine erected in the final chapter. As with Lantenac, the Cimourdain of relentless revolutionary justice eventually finds himself face to face with the human Cimourdain, the spiritual father of Gauvain, the embodiment of mercy.

Gauvain at a glance seems to be a character of simple conception: his defining characteristic is an almost angelic goodness. He is also the pivotal point in the story: on one hand, he is the son of Cimourdain, a republican, and on the other, he is the son of the Gauvain family, Lantenac’s heir. Through him, we are reminded that the Vendée is a fratricidal war. Allusions abound in the novel, for example, when Cimourdain declared his brotherhood with the royalist resistors, a voice, implied to be Lantenac’s, answered, “Yes, Cain.” Gauvain finds himself caught in the middle of such a frightful war. At first, he was able to overlook his kinship with Lantenac, on account of the older man’s monstrosities, but with Lantenac redeemed by his self-sacrifice, it becomes impossible to ignore his threefold obligation: to family, to nation, and to humanity. It is because of this that duty, which seemed so plain to Cimourdain, rose “complex, varied, and tortuous” before Gauvain. The fact is, far from being simple, Gauvain's goodness is neither effortless nor plain, and we are reminded that the most colossal battles of nobility against complacency often happen in the most sensitive of consciences.

Indeed, the triumph of Gauvain is a triumph of the moral conscience, the light which is said to come from the great Unknown, over the dismal times of revolution and internecine strife, “in the midst of the conflagration of all enmity and all vengeance, [...] at that instant [...] when everything becomes a projectile [...], when [...] justice, honesty, and truth are lost sight of [...]” To Hugo, the Revolution is a tempest, in the midst of which we find its tragic actors, forbidding figures as Cimourdain, Lantenac, and the delegates of the Convention, some supremely sublime, some utterly grotesque, and many both: “a pile of heroes, a herd of cowards.” But, at the same time, “The eternal serenity does not suffer from these north winds. Above Revolutions, Truth and Justice reign, as the starry heavens above the tempest.” Gauvain finally comes to peace with this realisation, and we hear him saying, “Moreover, what is the tempest to me, if I have the compass? And what difference can events make to me, if I have my conscience?”

But Ninety-Three is, after all, a tragic book. We might ask whether it is not the case that Gauvain is too much of an idealist. He wishes to found a Republic of Intellect, where perpetual peace eliminates all war, and where man, having passed through the instruction of family, master, country, and humanity, finally arrives at God. “Gauvain, come back to earth,” says Cimourdain. To this Gauvain cannot make a reply. He can only point us upwards, by self-denial, and by his love, towards the ideal.

And the task of the novel is no more than this, this reminder of the reality of life. The drama was created, as the Preface to Cromwell declares, “On the day when Christianity said to man: ‘Thou art [...] made up of two beings, one perishable, the other immortal, [...] one enslaved by appetites, cravings and passions, the other borne aloft on the wings of enthusiasm and reverie—in a word, the one always stooping toward the earth, its mother, the other always darting up toward heaven, its fatherland.’” And did not Ninety-Three achieve this? The legend of La Vendée, like the stage, takes crude history and distills from it reality. Let us conclude with this passage from the novel itself:

“Still, history and legend have the same end, depicting [the] man eternal in the man of the passing moment.”

#victor hugo#ninety-three#quatrevingt-treize#1793#reign of terror#vendée#romanticism#essay#lantenac#gauvain#cimourdain#in an earlier draft I also compared Gauvain to Alyosha Karamazov in a passing comment but I had to take that out for the sake of time#also Cimourdain is definitely a Kantian but doesn’t seem that Hugo approves of Kantian ethics#on the other hand Hugo isn’t Aristotelian either#because in his works reason and the passions are always diametrically opposed#whereas Aristotle / St Thomas would have said that the passions could be trained by reason

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

French fantasy: The children of Orpheus and Melusine

There is this book called “The Illustrated Panorama of the fantasy and the merveilleux” which is a collection and compilation of articles and reviews covering the whole history of the fantasy genre from medieval times to today. And in it there is an extensive article written by A. F. Ruau called “Les enfant d’Orphée et de Mélusine” (The Children of Orpheus and Melusine), about fantasy in French literature. This title is, of course, a reference to the two foundations of French literature: the Greco-Roman heritage (Orpheus) and the medieval tradition (Melusine).

I won’t translate the whole text because it is LONG but I will give here a brief recap and breakdown.

A good part of the article is dedicated to proving that in general France is not a great land for fantasy literature, and that while we had fantasy-like stories in the past, beyond the 18th century we hit a point where fantasy was banned and disdained by literary authorities.

Ruaud reminds us that the oldest roots of French fantasy are within Chrétien de Troyes’ Arthurian novels, the first French novels of the history of French literature, and that despite France rejecting fantasy, the tradition of the Arthuriana and of the “matter of Bretagne” stayed very strong in our land. Even today we have famous authors offering their takes, twists and spins on the Arthurian myth: Xavier de Langlais, Michael Rio, Hersart de la Villemarqué, René Barjaval (with his L’Enchanteur, The Enchanter, in 1984), Jean Markale, Jean-Louis Fetjaine or Justine Niogret (with her “Mordred” in 2013). He also evokes the huge wave and phenomenon of the French fairytales between the 17th and the 18th century, with the great names such as Charles Perrault (the author of Mother Goose’s Fairytales), Madame d’Aulnoy (the author, among others, of The Blue Bird), and Madame Leprince de Beaumont (author of, among others, Beauty and the Beast). He also evokes, of course, Charles Nodier, which was considered one of the great (and last) fairytale authors of the 19th century, the whole “Cabinet des Fées” collection put together to save a whole century of fairytales ; as well as the phenomenon caused by Antoine Galland’s French translation of the One Thousand and One Nights – though Ruaud also admits this translation rather helped the Oriental fashion in French literature (exemplified by famous works such as The Persian Letters, or Zadig) than the genre of the “marvelous”.