#landrace breeding

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

So a lot of new shit dropped in the latest Minecraft update but obviously I only care about the pigs. Let's discuss breeds!

Starting off with the original pig just because— this little guy's probably a Landrace pig!

They're some of the most standard domestic pigs out there along with Yorkshires, but Yorkshires have perkier ears. Landrace pig ears lay flat much more similarly to our Minecraft pigs!

Next we have the warm pigs. These babies are probably Durocs!

Look how red and beautiful they are! There aren't many common red pigs, so it was really between these guys and Tamworths. Tamworths are an Irish breed, so they don't come from a particularly hot climate. Durocs however originated from Africa from what I researched!

And finally we have the cold pigs. These guys are most definitely Mangalicas!

These guys are like. One of the most prominent breeds with thick creamy hair to keep them warm. They're also Hungarian! They're also my favorite pig breed!!!!!

Hope you learned something new about pigs ^ - ^

#i love pigs so much. unzips my hoodie to reveal a T-shirt that reads “ask me about my pig fun facts”#Minecraft#Minecraft pigs#Minecraft update#minecraft snapshot#Minecraft snapshot 25w05a#pigs#pig breeds#mangalica#duroc#landrace#words

6K notes

·

View notes

Text

THE HIGHLAND KHAIT: AN OVERVIEW

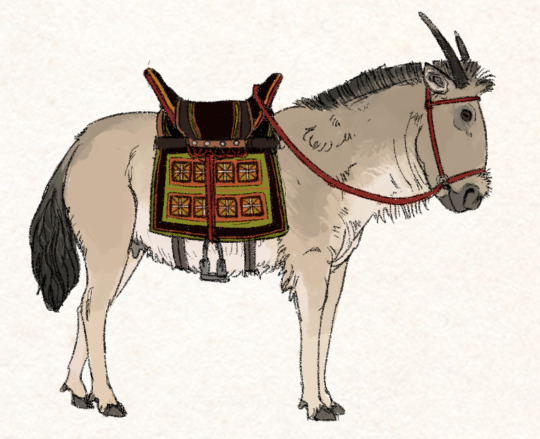

The Highland khait, known internally as the feydhi, is a landrace breed of the Highlands of contemporary Imperial Wardin, and highly distinctive from all other native khait in the region. Their horns are notably unusual, being curved and pointed and frequently asymmetrical, which is often cited as a result of their folkloric origins as hybrids of khait and the (asymmetrically one-antlered) scimitar deer. They are very stocky and small for a riding breed, typically standing no more (and usually less) than 55 inches at the shoulder. Their coats come in a wide variety of colors and patterning, though a majority of individuals are dun or gray. Their manes are notably short and stiff, and they lack the beards common in many other khait breeds.

While notably slower than other khait, feydhi are very surefooted and have notably smooth gaits, able to move at a steady trot over difficult terrain with minimal bouncing for the rider. They are extremely strong for their size, and fully capable of carrying most adult riders and heavy packs, and pulling plows.

Their hair is longer than average but provides little insulation and they do not grow winter coats, and instead rely predominantly on fat stores to cope with winter conditions. They are easy keepers that can gain and maintain mass with very poor grazing, though most require supplements of grain to their diets to gain sufficient fat stores to survive winters in the highest settled altitudes.

Feydhi can adapt well to the hotter lowlands conditions than other Highlands livestock largely due to this lack of thick hair. Because they require no supplement to their diet to maintain condition, they are very affordable khait and an asset (along with a few other specialized lowlands breeds) during dry seasons, and see wide use throughout Imperial Wardin (particularly as pack animals along trade routes). They often survive a little too well in the lowlands, being adapted to sparse mountain pastures rather than seasonally abundant grasslands, and can be prone to obesity when allowed to graze freely.

They show a small degree of selection for milk production due to the import of dairy to the regional diet of the Highlands. Their milk has the highest fat content of the native livestock, but a notably gamey taste that is generally disfavored. It's used primarily as-is for basic sustenance and medicinal purposes- growing children and pregnant women are encouraged to drink feydhi milk to build fat stores, and mounted herders will often ride lactating mares in the winter and subsist largely upon their milk. Their meat is also the fattiest of any of the regional livestock and (unlike their milk) generally regarded as the best in taste, though their value as riding animals and more expensive upkeep prevents their consumption on any regular basis.

Rendered, chilled feydhi fat mashed with berries and eaten on bread is a seasonal delicacy eaten at midwinter feasts. It is considered an obligation of a wealthy ruling clan to slaughter some of their khait and provide the fat for this meal to their dependents, and an indication of failing wealth and authority if they cannot. A phrase translating as 'rich in cattle, poor in fat' invokes the notion of having a clan having superficial wealth (in cattle, which can largely sustain themselves on poor grazing and thus can hide a loss of material power for a period) but a heavily insecure position (unable to actually afford to lose their more high maintenance assets), and is used colloquially to describe a person or people giving hollow performances to mask lacking or lost substance.

They have some unique behavioral quirks among khait, such as a propensity to use their lower teeth in allogrooming to rake and scratch each other. This favoring of their teeth also lends more aggressive animals to biting (in addition to the far more khait-typical headbutting and kicking), a behavior that seems reserved exclusively for humans and is rarely used in intraspecies conflict. As with all bovidae, they no upper incisors and their bite can only do so much harm in most circumstances, but they can cause significant damage to the fingers of the unwary. They are also known for their tendency to consume bite-sized animals such as small birds when given the opportunity- this is not atypical of khait (or many grazing herbivores at large), but is emphasized in combination with their tendency to bite to cast them as uniquely carnivorous.

Their temperaments are regarded as notably stubborn and somewhat testy, but this is made up for with their intelligence and generally calm demeanor. Feydhi are most prized for their bravery- they do not spook easily against wild predators and can perform some functions as livestock guardians, readily chasing off small threats and known to stand their ground against even large predators, particularly hyena (the most populous and routinely threatening predator in the region).

This trait is commonly noted in folktales- one western mountain pass is said to be haunted by the ghost of an old gray mare who stood guard over her master (a noted drunk, who had fallen off her back and passed out) against a pack of hyenas for an entire night. When her rider awoke the next day, he found her dead and bloodied with her horns stuck into a hyena's side, having killed the predators but succumbed to her own wounds. He was so sorrowful that he resolved to never drink again (outside of holidays, and perhaps weddings) and buried her under stone. Travelers through this pass customarily pour out liquor and leave little offerings of grain for the animal's spirit, which is said to be seen at night from a distance, standing vigilant atop its cairn, but vanishes when approached.

The settlement cycle stories of the Hill Tribes go into extensive detail about the cattle and horses brought overseas with the migrants, but elaborate little on their khait and imply that a riding culture did not exist during the settlement period. The stories tend to describe people as walking on foot or riding their cattle, and khait riding is only mentioned in descriptions of proto-Wardi mounted nomads in the lowlands. It is likely that khait riding (rather than sole use as pack animals) was an adopted practice post-settlement, and possible that khait were not brought along with the migrants to begin with.

The actual origins of the feydhi breed are ambiguous as such. Old Ephenni folklore mentions tiny 'fairy' khait living in the Highlands that predated the arrival of the Hill Tribes, suggesting that these animals were already established as feral herds. It's highly possible that these herds were are a relic of the cairn-building civilization that existed in the Highlands prior to recorded history and had already long vanished (likely in a combination of plague and dispersal) prior to the settlement. The stories of feydhi being hybrids between foreign khait and native deer is also suggestive of such an origin, with wild deer as ancestors being a mythologized twist on feral khait.

Feydhi do not have the same status of cattle or horses as fundamental to subsistence, with much of their use being in utility as pack animals and transport over difficult terrain. However, they play very significant roles in the livestock raiding aspects of warrior culture, where they are used for quick exits and to help drive cattle and horses. Their roles in other aspects of warrior culture are more varied between tribes- some use them near-exclusively for raids, while others rely on them for open combat. Khait warrior culture is most central in the western Urbinnas tribes, who each consider themselves to be the most skilled riders and uniquely specialize towards mounted archery. The Urbinnas tribes have a long history of interaction with the lowlands Ephenni Wardi (alternating cycles of conflict and trade, and a half century of allyship against Imperial Burri occupiers). Both groups have a strong history of mounted warrior culture, and each claims to have introduced mounted archery to the other.

Khait also play roles in regional combat sports, which include mock battles and raids, races, archery, and most famously khait wrestling. The latter involves two mounted riders attempting to wrestle one another off their khait, gain control of their opponent's mount, and then successfully lead both animals out of the ring without their opponent re-mounting. This sport requires very calm, collected animals that will not panic while being fought over, and the measured temperament of the feydhi is well suited.

#The Wardi Highlands are not analogous to Iceland At All but having just spent a week surrounded by an awesome small cold#adapted horse landrace breed it was time to like actually flesh these guys out#creatures#hill tribes

147 notes

·

View notes

Note

Asdfjk for some reason I hadn't realized your characters were dogs, I had just mentally accepted them as fantasy beasts. Is this to say contemporary breeds like the pekingese also exist in your world? O8

Pekingese is one of the oldest dog breeds so yes, they definitely exist. I think the range of breeds and types you'd come across at any given situation is determined by how likely those breeds would've been present at that place at that era. I wouldn't put dobermans in medieval times because the breed didn't exist before around 1890, or terriers in Edo era Japan. Idk, it's not that serious but I like to think it adds a layer of believability? It's sorta fun at least.

I should add that even when I assign specific breeds to my characters, in reality the overwhelming majority of them are mixed to some degree. Being truly and strictly purebred gets you into Habsburg situations.

#answered#anonymous#btw I don't care about breed standards or when they were officially recognized what matters is whether the dog type/landrace was present#I'm hoping this makes sense I can feel my english failing me I shouldn't be trying to explain how any of this works at 3 am

173 notes

·

View notes

Text

My plant breeding blorbo is going to be at a seed swap in February... I MUST GO

#Dude is a total weirdo who took a vow of poverty and subsistence farms#breeding regionally adapted 'landrace' plants for the intermountain west

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

The extreme European Maine coons are so fucking ugly

#the muzzle. is insanely broad#they look like a person with an unrealistically broad jaw#i do not see the appeal#i imagine a chunk of it is that i have a large new england landrace cat. who is adapted to the cold#but cat breeding is very different than it was a century ago. they have a breed standard. and outbreeding isnt allowed#they have changed

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

#to buy#going at the TOP of my xmas wishlist#if i dont get it for that or my bday imma buy it myself lol#price tag big but also i spend $0-5 on most books so an outlier here and there is fine to me lol#also this is like. a mf textbook. sO yeah its gonna cost money lol#anyways#tags#uhhh#book#dog book#dog breeds#primitive dog#sighthound#spitz#landrace#livestock guardian dog#indigenous dog#sled dog#hunting dog#idfk

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

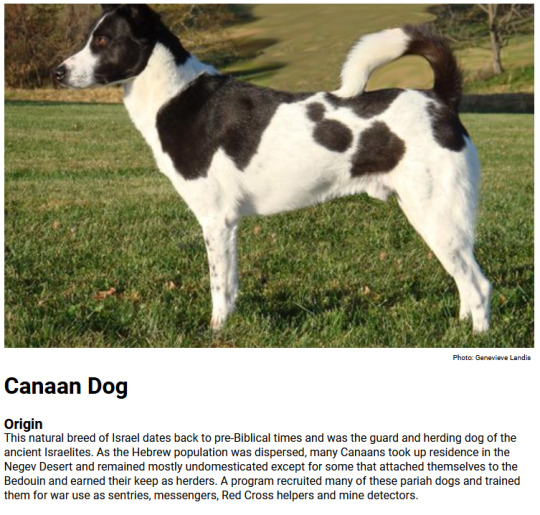

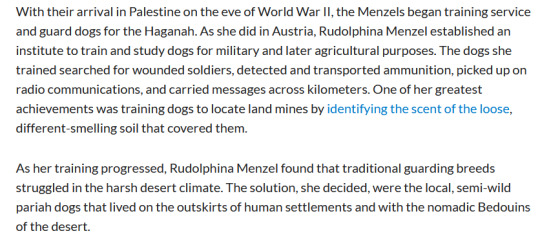

Colonialism is an ongoing problem in the purebred dog world and i just wanna take as second to talk about the national dog breed of Israel, the Canaan dog. Because here's the CKC's blurb on them

I have no doubt and am not denying ancient Hebrews lived with these dogs, but the Canaan comes from a stock of landrace breed native across the Levant and it has also gone by names such as Bedouin Sheepdog or Palestinian Pariah Dog.

Organized breeding of the Canaan began in the 20th century from captured Palestinian dogs (i would also point to the wording of 'redomesticating' used here, implying the feral pariah dogs were in some way not domesticated, which i think is disingenuous phrasing.). If you look up the Canaan, most sources you see on them explicitly brand Canaans as an Israeli breed, neglecting or downplaying any history they have with any of the other countless peoples or cultures in the region this breed has coexisted with across millenia. There's even an archeological site with ancient remains of canaan-like dogs was found in Ashkelon, located just 13 miles from the Gaza strip.

The developer of the 'modern' purebred Canaan was "ardent zionist" Rudolphina Menzel, who trained attack dogs for the IDF:

What really gets me about this story is how this native landrace breed was taken and trained to guard colonial settlements from the very people they lived alongside, there is something so twisted about it..

This is unfortunately nothing new in the world of dog fancy. There are many instances of explorers and settlers importing exotic new dogs from their travels, establishing a breed club, and then claiming stewardship over said breed without any involvement from the local peoples they took or bought them from. I'm not sure what to leave this on, i just think more people should be aware of these 'softer' forms of colonialism and how domestic animals can play a part in colonialism and nationalist narratives.

Anyway, long live the Palestinian pariah dog/ Bedouin sheepdog!

8K notes

·

View notes

Note

hello! could I ask for a list of cat breeds(not all, but generic and well-known breeds)? along with their personalities and health issues linked with each breed.

Writing Notes: Cats & their Personalities

Some cat breeds are closely associated with specific behaviors.

Ragdolls - often viewed as relaxed, friendly and affectionate.

Russian Blues - considered more intelligent and reserved.

But a new study published in the journal Scientific Reports is the first academic paper to investigate whether felines actually show breed differences in behavior and how, or even if, these traits are passed down from one generation to the next.

As Nick Carne writes for Cosmos, researchers from the University of Helsinki drew on data detailing around 5,726 cats’ behavior to identify patterns among breeds and gauge heritability.

Overall, the team found that different breeds do in fact behave in different ways; of these behaviors—including:

activity level,

shyness,

aggression and

sociability with humans—around half are inherited.

The starkest differences among breeds emerged in the category of activity.

The smallest differences, meanwhile, centered on stereotypical behavior.

Prolonged or repetitive behaviors, like pacing or paw chewing, with no discernible purpose are called stereotypies.

In some cases, these abnormal behaviors are actually self-destructive.

“Since the age of about two weeks, activity is a reasonably permanent trait, whereas stereotypical behaviour is affected by many environmental factors early on in the cat’s life as well as later,” Hannes Lohi, study co-author and lead researcher of the University of Helsinki’s feline genetic research group, says in a statement. “This may explain the differences observed.”

To estimate behavioral traits’ heritability, lead author Milla Salonen, Lohi and their colleagues focused on 3 distinct breeds:

Maine Coon

Ragdoll

Turkish Van

The scientists’ full research pool included feline behavior questionnaire responses regarding almost 6,000 cats that accounted for 40 different breeds.

As Lohi explains in the statement, the team had ample data on members of the three breeds, as well as the chosen cats’ parents.

Additionally, Lohi says, the trio is “genetically diverse.”

The Maine Coon is related to Nordic cat breeds and landrace cats—domesticated, locally adapted varieties—

while the Ragdoll is related to Western European and American cat breeds.

The Turkish Van and the similarly named Turkish Angora appear to have separated from other breeds at some point in the distant past.

Salonen et al. (2019) surveyed Finnish cat owners on their cats’ behaviors, which included:

"tendency to seek human contact,"

"aggressiveness towards human family members, strangers, or other cats," and

"shyness towards strangers or novel stimuli."

In total, 5,726 cats were studied. The researchers then separated these cats into 19 breeds.

The researchers controlled for environmental factors including “weaning age, access to outdoors, presence of other cats,” and general characteristics (sex, age of cat) in their analyses.

They identified the breeds corresponding with the 10 following behavioral traits:

Aggression Toward (Human) Family Members

Most aggressive toward family members: Turkish Van and Angora (1st); Korat (2nd); Bengal, House cats (i.e., cats that are not selectively bred), Devon Rex (3rd)

Least aggressive toward family members: British Shorthair

Aggression Toward Strangers

Most aggressive toward strangers: Turkish Van and Angora (1st); Korat, Devon Rex, Russian Blue (2nd); Burmese and Burmilla, House cats, and Ragdolls (3rd)

Least aggressive toward strangers: British Shorthair, Persian Cats, Cornish Rex

Aggression Toward Other Cats

Most aggressive toward other cats: Turkish Van and Angora (1st); Korat (2nd); Bengal, House cats (3rd)

Least aggressive toward other cats: Persian (1st); Devon Rex, Maine Coon, Siberian and Neva Masquerade, Ragdoll, Norwegian Forest Cat (2nd)

Shyness Toward Strangers

Most shy toward strangers: Russian Blue (1st); House cat, Bengal (2nd)

Least shy toward strangers: Burmese and Burmilla (1st); Cornish Rex (2nd); Persian, Abyssinian, Norwegian Forest Cat, Korat, Saint Birman (3rd)

Shyness Toward Novel Objects

Most shy towards novel objects: Russian Blue (1st); House cat, Turkish Van and Angora, Bengal, European Shorthair, Siberian and Neva Masquerade (2nd)

Least shy towards novel objects: Persian, Cornish Rex (1st)

Likeliness of Seeking Human Contact

Most likely to seek human contact: Korat, Devon Rex (1st); Oriental breeds (Balinese, Oriental Longhair, Oriental Shorthair, Seychellois Longhair, Seychellois Shorthair, and Siamese), Abyssinian, Russian Blue, Maine Coone, Cornish Rex (2nd)

Least likely to seek human contact: British Shorthair (1st); St Birman, European Shorthair, Persian (2nd); Siberian and Neva Masquerade, Ragdoll, Norwegian Forest Cat (3rd)

Activity Level

Most active: Cornish Rex, Korat, Bengal (1st); Abyssinian (2nd); Devon Rex, Oriental breeds, Burmese and Burmilla (3rd)

Least active: British Shorthair (1st); Ragdoll, Saint Birman (2nd); Siberian and Neva Masquerade, Persian, Norwegian Forest Cat, European Shorthair (3rd)

Wool-Sucking Propensity

Most likely to suck wool: House cat, Norwegian Forest Cat, Turkish Van and Angora, Maine Coon

Least likely to suck wool: Russian Blue (1st); Persian (2nd); Ragdoll, Cornish Rex, British Shorthair (3rd)

Excessive Grooming

Most likely to groom excessively: Burmese and Burmilla, Oriental breeds

Least likely to groom excessively: Persian, British Shorthair (1st); Norwegian Forest Cat, Siberian and Neva Masquerade (2nd)

Behavioral Problems

Most likely to have a behavioral problem, according to owners: Oriental breeds, Persian

Least likely to have a behavioral problem, according to owners: British Shorthair, European Shorthair

Interestingly, house cats (i.e., cats that were not selectively bred) were more aggressive and shyer than purebred cats.

The researchers note that such a finding may not be due to genetic differences. Although house cats and purebred cats in the study were similar in their current environment, they could have differed in their early life. Cat breeders may be especially inclined to carefully socialize kittens as they prepare them for sale or for show.

The researchers also found that the heritability of the studied behaviors was moderate, ranging from .40 to .53, which is similar to the previously estimated heritability of behaviors among dogs. This number indicates that approximately half of the variance in cats' behaviors can be attributed to genetic variations in the population. Therefore, nature appears to play a non-trivial role in cats’ personality.

Finally, the researchers identified correlations among both physical and behavioral traits in cats.

For example, more sedentary and longer-haired cats were less inclined to seek human contact. The researchers suggest that Ragdoll breeders, for instance, may have chosen to breed calm cats that would be fine with being handled and brushed by humans. Calm cats are also less active and thus may be less inclined to seek human interaction.

Although nature matters, nurture cannot be dismissed. Certainly, the human role in a domestic cats’ disposition is significant in multiple ways, shaping both their genes and environments.

Some Common Health Issues

Least aggressive: Ragdoll - Regular vet checkups are crucial for a Ragdoll’s health, as they might be prone to certain genetic issues including hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (thickening of the heart muscle), environmental and food allergies, and bladder stones.

Most cuddly: Maine Coon - It is a native breed that developed naturally over time. Despite this, there are still some genetic health issues to watch out for such as: Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy, Hip Dysplasia, and Spinal Muscular Atrophy

Most active: Devon Rex - Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy (HCM), Polycystic Kidney Disease, Hip Dysplasia, Luxating Patella

Least active: Exotic Shorthair - Health problems that their brachycephalic features can cause include: Jaw deformities, Breathing issues, and Eye problems; and Persian - Well-bred Persian cats can be healthy and robust. But there are still some Persian cat health issues you should be aware of: Polycystic kidney disease, Brachycephalic syndrome, Progressive retinal atrophy

Bravest: Abyssinian - They are commonly prone to: Gingivitis, Patellar luxation, Hyperesthesia, Renal amyloidosis, Pyruvate kinase deficiency

And some fun infographics I found for you:

Sources: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 ⚜ More: References ⚜ Writing Resources PDFs

Hope this helps with your writing!

#cats#animals#anonymous#writeblr#literature#writers on tumblr#writing reference#dark academia#spilled ink#writing prompt#creative writing#writing resources#last of this group of requests. working on the others & will queue again soon. sooo tired ! but love the topics as always

87 notes

·

View notes

Note

is caramel a siamese? :o

Hello!!! You've unfortunately activated my trap card, cat autism! Caramel is a flame/red point domestic mediumhair.

Pointing on cats is a coat that is kind of like thermal! The parts that are colder (skin closer to bone or cartilage, typically), will have deeper pigmentation. Cats are 99% something called landrace, which means they're just "cat", basically. About 120 years ago, people began to pull landrace population cats together into smaller gene pools to breed for specific traits, that were already present in randombred cats, creating breeds. So, in all actuality, pedigree cats are quite rare in comparison!

Of course, that wouldn't matter much in a furry world, but I hope I was able to teach you something nonetheless... it's like squares and rectangles! All siamese cats are pointed, but not all pointed cats are siamese.

#sfw furry art#art#sfw#my art#furry art#clean furry#anthro#fursona#safe fur work#sfw fursona#demonz trio

94 notes

·

View notes

Text

Apparently people have not heard of the Tahltan Bear Dog!

John Blakiston Gray, a sergeant with the Provincial Police at Telegraph Creek with two young Tahltan bear dogs; T.W.S. Parsons collection. 1940s. The photographer is undetermined. BC Archives.

A Tahltan bear dog; known as Chips; T.W.S. Parsons collection. 1940s. The photographer is undetermined. BC Archives.

Tipi a Talhtan Bear Dog, owned by T.W.S. Parsons of the Provincial Police. 1940s. The photographer is undetermined. BC Archives.

Tahltan matriarch smoking her pipe, Salmon Creek Reserve; her little Tahltan bear dog is sitting beside her. 1931. The photographer is undetermined. BC Archives.

"Another view of the Nanaook [Nanook?] Edzerza marten trapping party showing their Tahltan bear hunting dog coming around the nose of the sled..."; 1926. The photographer is undetermined. BC Archives.

— Crisp, W.G. "The Tahltan Bear Dog". Summer 1956. The Beaver, pg. 39.

every time we talk about taking the dogs with us snowshoeing and someone goes "but will small dogs?? with little legs?? in DEEP SNOW??" i get confused. yeah the snow is deep. it's often 6+ ft. how big would a dog have to be not to have challenges in deep snow? how big is your dog dude??

#image described#archival#Tahltan Bear Dog#extinct landrace#extinct breed#BC Archives#1926#1931#1940s#Canada's History#The Beaver#1956#W.G. Crisp#comment is hilarious because First Nations people invented the snowshoes#and the snowshoe runners had small dogs with them

43 notes

·

View notes

Note

What does agriculture and typical plants and animals used in food look like in different regions and cultures?

For the sake of brevity, my answer will only cover this part (but don't worry, I'm working on the plants (and invertebrates) as well) :

VERTEBRATE LIVESTOCK OF UANLIKRI

Thanks to a wide range of environments and intercontinental trade, Uanlikri boasts a wide variety of vertebrate livestock, some domesticated locally, others brought along by settlers from the other continental masses. Most livestock on Uanlikri are ceratopsians (some more highly derived than others).

Caviþ

Pronounced chavith. Caviþ are a highly derived species of ceratopsians originating from the Basin region. The wild species still exist, roaming the southern Basin plains in great hordes.

For the most part, caviþ are kept as beasts of burden and for their meat and leather. In most locales, they are unpopular compared to O'ohu, which are more powerful, meatier, more docile, and have more offspring at once. Nevetheless, keeping caviþ has its avantages: caviþ are smaller, hardy, tolerant of crowding, and produce rough but warm pelts.

In general, caviþ are too small to be ridden by adult antioles, but not for the Apinaat and Abimaat, two peoples of pigmies who make their living on caviþback across the southern Basin plains and on the Matar Peninsula. For the Apinaat and Abimaat, caviþ, wild and domestic, are their whole livelihood. Their use of caviþ as mounts gives them an incomparable edge in warfare and has earned them a fearsome reputation.

Wek

Wek are one of the few non-ceratopsian livestock originating from Uanlikri. They were first domesticated in coastal areas of the Pwetitwì range from large gull-like birds, and spread from there to most northern coastal areas of Uanlikri. Wek are meaty and adaptable birds kept for their eggs, plumage, and guano. They require access to open water to thrive, but accept saltwater and freshwater alike. They are primarily kept in coastal areas, as well as along the Koramme river and Basin Great Lakes, where the slow-moving waters suit them fine.

Kabi

Kabi, a guinea pig sized ceratopsian, are the most widely kept livestock on Uanlikri. The kabi in the picture was enlarged for ease of viewing: the vast majority of kabi breeds are much smaller, though giant breeds do exist. Kabi are a multi-purpose livestock: they are bred for their meat, abundant eggs, soft patterned pelts, and companionship. Kabi are extremely adaptable and very tolerant of crowding. Their ease of keeping in urban environments has made them ubiquitous through all the cities of the continent.

There are hundreds of kabi breeds and landraces on the continent. Kabi have a tendency to establish themselves as feral pests as well as livestock, where natural selection by the environment encourages the development of landraces best adapted to the local climate. They also make excellent pets due to their highly social nature, and many lines of kabi are bred purely for good temperament and pleasing (though sometimes extreme) appearance. Kabi are also ubiquitous overseas: it is unclear where they were first domesticated, but most theories point towards dwarf and standard kabi originating from one domestication event on Uanlikri, and red-leg kabi originating from another domestication event overseas, possibly of a different but related species: this would explain some of the difficulties in breeding dwarf and standard kabi to red-leg kabi.

Tsut

Tsut were one of the livestock species brought along by the Senq Ha Empire, conquerors and settlers of the Western Peninsula. These diminutive therizinosaurids were selected through millenia for an extremely downy, frizzy coat which can be sheared and spun like wool. Of all Senq Ha livestock, tsut were the ones to find the fastest and most widespread adoption, only limited by their destructive browsing habits and preference for hilly terrains and cool weathers. Tsut down revolutionized the world of textiles in Uanlikri, where spun-down fibres were previously very rare and very expensive, requiring capture and shearing of wild animals with very little suitable fibre.

Tsut are primarily raised for their fiber but also provide meat and more importantly crop-milk. Consumption of crop-milk is slow to catch in communities not descended from the Senq Ha, but the Senq Ha's people use crop milk abundantly, using it fresh or processed in dozens of different ways.

Llekme

Llekme were domesticated in the Northern peninsulas of Uanlikri from a species related to the caviþ. They share many of the caviþ issues and advantages, being hardy but temperamental. However, contrarily to the caviþ, they are an extremely popular livestock among both sedentary and nomadic populations Uanlikri's north. There, they are used as beasts of burdens and pulling animals of limited power as well as for their meat. For the desert nomads of the Atashir, llekme provide essential help in carrying their tents and tools; in cities, they are often used as pulling animals, working alone or in teams to pull small carts and coaches.

Hêtâ

Hêtâ are family of highly derived ceratopsians, including a dozen species and subspecies on the mainland and a few endemic island species. They are, in truth, not yet a domestic species. All species of hêtâ are game animals highly appreciated for their ornemental feathers and delicious meat, and there have been several attempts to domesticate various species of mainland hêtâ, none of which have been successful. Mainland hêtâ have extremely nervous dispositions, are prone to dying from stress, and mostly fail to reproduce in captivity: they rarely breed, and when they do, they most often do not provide parental care, leading to the death of the chicks.

This said, there is an ongoing project on the Ojame archipelago to restore and domesticate the near-extinct Ojame hêtâ. The Ojame hêtâ is endemic to the archipelago. Due to the absence of large predators on the archipelago, it has evolved to be larger and much less fearful than mainland hêtâ, but was driven to near extinction by hunting and the introduction of larger, bolder breeds of oujabe [dog analogue] from the mainland and of continental hêtâ imported for use as wild game.

The failure of mainland domestication attempts and a joint desire to preserve and profit from the Ojame hêtâ has led to a unique, unusually coordinated project to domesticate and reestablish the Ojame hêtâ. In a rare show of goodwill and collaboration, this project is shared by both Wetki and Ranaite communities on the archipelago. The Ojame hêtâ is thought to be a promising source of meat and ornemental feathers as its population levels rise and stabilized. Successful captive reproduction has been achieved, and semi-domesticated captive population are being reintroduced to Êrar, the archipelago's largest island where the hêtâ had been completely eradicated.

Wagwacguk

The wagwacguk (wag-wash-guk) is a wild animal living as familial herds in the tundras south of the Kantishian, with a domestic subspecies of marginal range in the lands of the Daghwa-Igdø and the Kantishian High Plateau. It is a large, extremely hardy animal with a warm, plush coat and thick leather. For the Daghwa-Igdø, wagwacguk are their main livelihood. One month per year, they feast on the fresh meat of wagwacguk calves, culling their herds as the first dayfrosts touch their lands; the later kills are preserved by smoking and freezing. The rest of the year, wagwacguk blood provides them with most of the protein in their diet. Wagwacguk pelts, leather, guts, horn and hooves are the materials involved in most of their material culture.

Though domestic wagwacguk are most closely associated with the Daghwa-Igdø, they are also kept by the Oubixwø-øi of the Kantishian high plateau as part of the Oubixwø-oi's diverse survival strategies.

O'ohu

O'ohu are domestic hadrosaurs named, in most regions where they are kept, after their loud and haunting cry. They are the largest and second-most widespread livestock on Uanlikri. Where they are kept, they are invaluable for their work as beasts of burden: plowing fields, pulling carts, carrying charges of all kinds. They are essential to the work of peasants and armies alike, and they are surprisingly fast. Historically, they have often been used in active combat, pulling war chariots. They cannot be ridden: their back ridge is too fragile to bear the weight of a rider and their alternatively bipedal and quadrupedal gait makes balancing a saddle impossible. They are also used for meat, blood, leather, and other byproducts. Their finely scaled and patterned leather is considered especially attractive, and their hollow horns are often made into music instruments. In many cultures, O'ohu grastroliths are considered to have medicinal properties as the ultimate digestive aid, and are often sold at a considerable markup by gastrolith merchants.

#worldbuilding#uanlikri#speculative biology#speculative evolution#dinosaur#antiole world#art by me#asks#feel free to send the agriculture and plants asks again btw i'm working on it I just felt this would get wayyy too long#caviþ#chavith#kabi#llekme#wek#hêtâ#heta#tsut#wagwacguk#o'ohu#long post

76 notes

·

View notes

Text

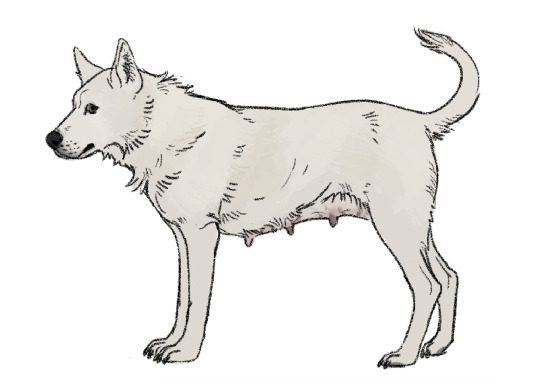

Four (relatively) distinct types of livestock guardian dogs in the Imperial Wardi region. (Left to right: hnorai dam, chin-tsimouna, dírgrahdain, and chin na Hittsanaedi)

Dog breeds in the modern sense of the word in which a dog is selected for highly specific physical traits and carefully bred to retain 'purity' is virtually nonexistent in this setting (and where similar practices occur, it's usually as an outlier situation surrounding a single dog rather than as a standard practice). Most working dogs first develop out of landraces via natural selection, and are bred according to their function above all else. Their forms are the results of natural pressures from their environments, the demands of their jobs, genetic isolation (or lack thereof), and often some degree of selectivity or preference for coloration or features.

These are the four types that occur within the region, all derived from a progenitor landrace guard dog (the last common ancestor of all four contemporary types probably existed about 950-1000 years before present). All share commonalities of a large size, rain-resistant hair, notably dense winter coats, a loud and deep bark, thick muzzles, and strongly sloping chests. They must be able to hold their own (usually through intimidation but occasionally in fights) against large predators that often physically outmatch them- lions, king hyena, hyenas, and wild dogs being most threatening to livestock. They also may have additional functions in dissuading theft and poaching of livestock by humans, and they may sometimes double as basic guard dogs of homes or villages.

Dogs here are bred almost entirely according to their function (you breed LGDs with LGDs, it doesn't usually matter if they look different or come from different stock), with the main exceptions being 'breeds' that are aspects of important cultural heritage or that have specific culturally/regionally preferred aesthetic traits. The chin-tsimouna is the most common of the three and is the result of minimally selective breeding (though some populations form unique strains or have a selective local status), while the other three are semi-isolated heritage types (the hnorai dam for some North Wardi groups, the dírgrahdain for most of the Hill Tribes, and the chin na Hittsanaedi among Ephenni Riverlanders).

---

Hnorai dam: Very rare in the contemporary, with undiluted animals of this stock surviving in some of the most isolated parts of the region's north. This type is distinct for typically having a somewhat stockier build than the others, solid coats, pointed ears, and a tail held upright and curved when relaxed. Most are solid white, gray, or black, and will often be assigned to horses of matching color. This is also the most 'basal' of the regional LGDs, a dog close to this in form (but probably not with solid coloration) was the common progenitor of all other livestock guardian breeds in the region. Variants on 'hnorai dam' are the common name, simply meaning 'guard dog' in the North Wardi language (as they are often used as village/household guards as well as livestock guardians).

Chin-tsimouna: This is the most ubiquitous type, occurring region-wide (and beyond) and used by a variety of peoples (throughout the core Imperial Wardi sphere and among the Cholemdinae, with some usage among the North Wardi, Hill Tribes, and Wogan). They have the most significant foreign ancestry (largely from Burri and Yuroma dogs) and most frequent 'crossbreedings' with feral populations. Due to these factors, the look of these dogs is highly variable (with the 'chin-tsimouna' name functionally being a catchall for any LGDs not of an otherwise specified type). There ARE some broad commonalities (beyond strictly the underlying features common to all these LGD types). The ears are rarely pointed, and usually are bent or lay flat. Fawn coloration with a melanistic mask is by far the most common, with white, gray, and black dogs coming in second (often semi-selectively bred or chosen to match the coats of their charges). Solid colored chin-tsimouna are very rare. There are numerous regional names for type-variants, but 'chin-tsimouna' is the most common descriptor for the overall type, meaning 'horse-dog' (in reference to their typical charges, who they uniquely live among).

Dírgrahdain: This is the native livestock guardian dog of the Highlands. They are the most physically distinctive from their counterparts, and their traits are among the most consistent (due to rarity of feral dog populations in their native range and their status in shared cultural heritage encouraging maintenance of their distinctive traits and discouraging crossbreeding). The most distinctive features are a dense mane, pointed ears, and tightly curled tail. An extended melanistic mask is highly common, and very pale 'evil eyes' are favored in this population, believed to be the most frightening to predators and evil spirits. The name dírgrahdain means 'liondog', mostly referring to their mane. [Extended dírgrahdain post here]

Chin na Hittsanaedi: This is the 'youngest' of the distinct types, and derives from a period of significant crossing between dírgrahdain and chin-tsimouna within the Ephenni riverlands (region south of the soutwestern Highlands, between and around the convergence of the Erubin and Nedachemi rivers) due to significant interaction and overlap of territory between the Ephenni and the West Rivers Hill Tribes under Imperial Burri occupation. The curled tail and pale eyes of the dírgrahdain is common in this population, though the pointed ears are rare and the 'mane' is less developed or absent. Most other traits are typical of the chin-tsimouna type. Dogs of this stock are mainly used in rural parts of the province of Ephennos, and their significance to aspects of modern era Ephenni cultural identity dissuades intentional breeding with both of their progenitor types. The name chin na Hittsanaedi means 'Riverlands dog' (more literally 'dog of the Riverlands').

#creatures#The chin na Hittsanaedi shown here depicts a conceivable coat pattern and appearance for Orange Son Of A Bitch of prev post

235 notes

·

View notes

Text

The history of sheep in north Western Europe and especially the British Isles is so fascinating. I wish there were more comprehensive reports on the genetics of landrace sheep breeds in the area.

45 notes

·

View notes

Note

Fav chicken breed and why?

Production Leghorns

They are short lived birds full of life and personality that most people never understand or get to see. Most people see their flighty nature and think of them as a stupid hateful chicken breed when they were originally a landrace meant to fend for themselves. They still retain that sense independence you might not see as strongly in asiatic chicken breeds. It's sad we took this breed already known for naturally high egg production then min maxed it, discarding the birds ones they reach 2 years of age. If you like white store bought chicken eggs, it was likely laid by a white production leghorn or her descendants. To be loved by a leghorn feels like something special to me. They are funny, intelligent, and very sensitive birds.

Also big face meats which isn't a trait I want in my bantam breeding project but it's something I like to appreciate in mediterranean breeds like leghorns.

Honorable mentions

-Ayam Cemani

-Phoenix

-Brahma (bantam or standard)

-Cornish Game bantam

-Serama

58 notes

·

View notes

Text

I've been posting a lot about mustangs lately, but I realize I never defined the term:

a mustang is a member of a landrace horse breed that lives on federally protected land in the American West. they're often called "wild horses," but they're technically feral; they're descended from animals that escaped from captivity over the generations, and while they're pretty genetically diverse, on the whole they tend to be medium-sized, smart, and hardy. with few natural predators, these feral horses are overpopulated by the tens of thousands, so to protect the land, the government occasionally rounds some of them up and auctions them off to private owners.

they start at $125 a head, which is absurdly low for a horse--the only catch is that 1) they've never been checked by a vet, so you don't know what problems they might be harboring, and 2) they've never been handled by humans, so you have to put in a lot of work to make them friendly and rideable. most of them have the potential to become great horses, especially for western-style riding, but you never quite know what you're adopting. a guy I know bought a stunning black horse for $400 (a steal!!), but even after six months of training, it's so skittish that he can barely touch it. maybe six more months will fix that, and maybe not. that's the gamble.

among farmers and horse enthusiasts, mustangs are fairly polarizing, because some people see them as pests who ruin their grazing land, while others see them as a symbol of the west, the cowboy, and the wild frontier spirit, who deserve to be kept wild and free. to be clear, they're "wildlife" in the same way that a feral cat is "wildlife," but, well, it's a debate nevertheless.

the best part is, they're auctioned online! you can browse some of the available horses here.

#horse#not 100% proofread. sorry#the exact origin of mustangs (spanish? native american? cowboy/settler? modern? all of them?) is beyond the scope of this post

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

tbh I'm never going to stop being mad about the Manx syndrome that makes Manx cats manxes. It's an easily, Visually identifiable trait that causes the afflicted animal life long discomfort and mobility issues so severe many need specialized care and equipment to give them a normal life. And that isnt even taking into account how many die as kittens or who need to be put down because they'll never have the minimum quality of life needed to subject them to their difficulties.

there's 2 genes that can cause shortened tails/no tail in cats and while it's debatable how ethical the other one is, due to how important tails are for cat communication, the bobtail Gene is at least not devastating to the animals welfare. Unlike Manx syndrome it just causes the kittens to be born with fewer tail vertebrae. All the other vertebrae are unaffected.

Manx syndrome, in the more severe cases, which to be clear are the breed standard and are considered Desirable, cause the back half of the spine to fail to form correctly. This causes the cats to "hop like bunnies" bc their hind legs are partially paralyzed. they have severe nerve issues bc their spinal cord isn't fully encased in bone like it should be. The paralysis effects their guts too, making many of them incontinent or unable to relieve themselves properly. which leads to chronic UTIs and them needing frequent baths. which, they are cats, they do not like baths.

The main defense of the continued intentional breeding of manxes is that it is a naturally occurring mutation, as in its a landrace breed that initially happened on its own in the feral cat population on the island of mann. "if they were able to survive and reproduce under those conditions then surely it's ok" type of argument. A dominant trait spreading through a feral cat population on a small island that has no predators and plenty of small animal prey to eat, is not a defense. it's the law of large numbers.

#Prime was intentionally bred by a breeder who wanted to get rich selling manx cats nc they saw how expensive the kittens were#the kittens are so expensive bc many litters end up like Primes. with 3/5 kittens needing to be put down within weeks or days of being born#Of the two kittens who made it to 6months only Prime was ever deened adoptable. her brother had to stay at the manx specific shelter#and he only made it to a little over a year before he started suffering from kidney failure bc of the constant UTIs#he had perfect. Specialized care and as much resources and attention as he needed and he still didn't get to live his life#Prime's better off obviously but i still have to spend a lot of time on her care and she doesn't get to be a cat in the same#way as her sisters#ie my other two cats who are just random bred shorthairs#cw animal cruelty#most of the sources about manx syndrome are in reference to it occuring randomly in livestock or humans#bc like#it is something that does just happen without any intentional breeding for the trait unfortunately#cats just handle it a lot better for their own reasons#' spina bifida' is the technical term but its called manx syndrome in other animals too

33 notes

·

View notes