#konowata

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Link

The world has fallen in love with Japanese cuisine. It has even been recognized as intangible cultural heritage by UNESCO. You probably know all about the big stars of Japanese food: sushi, noodles, onigiri. Maybe you've even tried some stranger Japanese dishes, like the opinion dividing natto.

But have you ever heard of chinmi? Chinmi 珍味 literally means "rare taste," but it also contains the meanings of acquired taste and delicacy. To give you some context of what sort of food qualifies as a chinmi, the word is also used to describe some non-Japanese foods such as caviar, truffles, and foie gras, which are described as sekai no sandai chinmi 世界の三大珍味, the world's top three delicacies.

The idea of chinmi pops up in Japanese popular culture across the spectrum from the surreal Toriko to the classic Oishinbo. Seeking out strange gourmet dishes is possible in the real world too. Even for Japanese people, these are a little out of the ordinary. If you really want to level up your Japanese food appreciation, seek chinmi out. Some of them are hard to find. Some of them are hard to stomach. Some of them are hidden gems.

Read more!

#food#japanese food#japan#delicacies#uni#karasumi#konowata#kusaya#shuto#dorome#tonburi#fugu#tofuyo#karashi renkon#hebo#kurozukuri

20 notes

·

View notes

Photo

@organdivider reblogged my post celebrating 3,000 followers! Yeah!!!!

For you, I picked out the kanji 「腸」, pronounced ‘chou’.

It means “intestines, guts, bowels, viscera”. It also kind of looks like one of the kanji for sun, 陽! (And the kanji for 揚 to fry, and 傷 wound, and some fun obscure ones 殤 to die at a young age, 觴 cup for alcoholic beverages, and 鯣 dried squid).

Here are some extra-fun words/phrases that use this kanji!

(It got kind of long so it’s going under a read more. See below!)

If other readers would like a personalized kanji post, check out my follower spree post here!

盲腸 mouchou appendix

大腸 daichou large intestine

小腸 shouchou small intestine

十二指腸 juuni-shichou duodenum (literally ‘twelve finger intestine’)

断腸 danchou heartbreak (or literally, severed intestines)

腸 can also be pronounced ‘harawata’, which, broken down into ‘hara’ and ‘wata’, means ‘stomach cotton’ (like a stuffed animal)

はらわたが煮えくり返る harawata ga nie-kurikaeru to be furious; to seethe with anger; to have one's blood [intestines] boiling

鉄心石腸 tesshinsekichou will of iron (literally ‘iron heart stone intestines’)

鼓腸 kochou flatulence

kanchou and I quote from Wikipedia: “Kanchō (カンチョー) is a prank performed by clasping the hands together in the shape of an imaginary gun and attempting to poke an unsuspecting victim's anus, often while exclaiming "Kan-CHO!".[1] It is a common prank among children in East Asia such as Japan... The word is a slang adoption of the Japanese word for enema (浣腸 kanchō).[7] In accordance with widespread practice, the word is generally written in katakana when used in its slang sense, and in kanji when used for enemas in the medical sense.”

綿抜き watanuki gutting (esp. a fish); gutted fish

羊腸 youchou 1. winding; zigzag; meandering 2. sheep intestines (orig. meaning)

九回の腸 kyuukai no chou having one's guts twisted in anguish; deep grief; heartbroken thoughts

海鼠腸 konowata salted entrails of a sea cucumber; salted entrails of a trepang

And many more!

#I dID nOT kNOW that about kancho#There are so many strange and interesting words that use this kanji#organdivider#3000 follower spree#chou#腸#also I think I tried to say fire extinguisher today and my coworker heard intestines D:

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

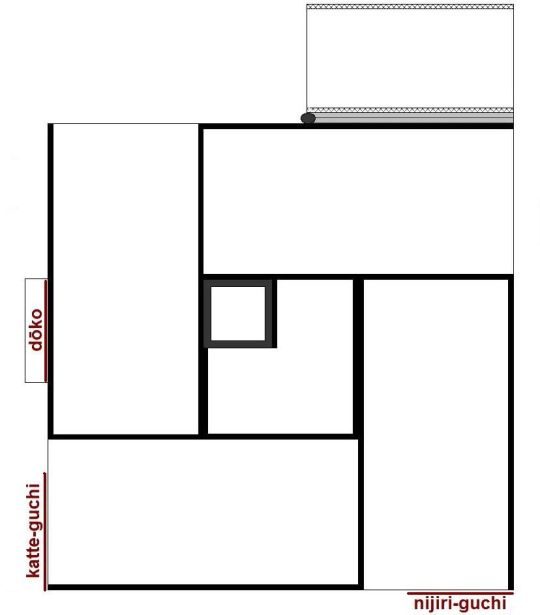

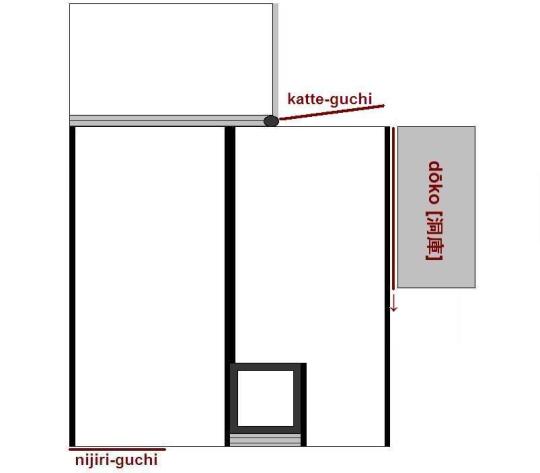

Appendix: the Rikyū Hyakkai Ki, Part 32: (1591) Intercalated First Month, Thirteenth Day, Evening.

92) Intercalated First Month, Thirteenth Day; Evening¹.

○ Uraku sama [有樂樣]², Ryūami [立阿彌]³.

○ 4.5-mat [room]⁴.

○ Hairyō gama [拜領釜]⁵; ◦ seitaka chawan [せい高茶碗]⁶; ◦ chaire ・ Konoha-zaru [茶入・木の葉ざる]⁷; ◦ Seto mizusashi [瀬戸水さし]⁸; ◦ usucha ・ Tenka-ichi [うす茶・天下一]⁹; ◦ hirai Seto mizu-koboshi [平イせと水こぼし]¹⁰.

○ Koi no yaki-mono [鯉ノやき物]¹¹; ◦ konowata [このわた]¹²; ◦ koma-koma jiru [こまゝゝ汁]¹³; ◦ meshi [めし]¹⁴.

○ Hikite [引て]: ◦ dengaku [でんがく]¹⁵.

○ Kashi [菓子]: ◦ fu-no-yaki [ふのやき]¹⁶; ◦ yaki-guri [やきくり]¹⁷.

_________________________

¹Urū-shōgatsu jūsan-nichi ・ ban [閏正月十三日・晩].

The Gregorian date of this chakai was March 8, 1591.

An evening chakai generally began shortly after sunset (so that the guests could come to the host’s house without the inconvenience of needing to light their way with a lantern), so the sky would have still been reasonably bright when the guests first entered the room for the sho-za. Thus auxiliary lighting was usually kept to a minimum* at this time. It would be quite dark when they went out for the naka-dachi, however, and so the artificial light had to be increased starting around the time that the kaiseki was served†. __________ *Generally a paper-shrouded oil lamp sufficed to welcome the guests at the beginning of the sho-za.

†Usually by bringing out a paper-shrouded candlestick to illuminate the shōkyaku's zen.

The flames in the stone lanterns in the roji were lit as the sho-za came to an end, and an andon [行燈] was placed in the genkan near the guests' entrance so they could light their way through the roji to the koshi-kake for the naka-dachi. On their return, the paper shades would have all been removed from the oil lamp and candle that gave light to the interior of the tearoom.

²Uraku sama [有樂樣].

This was the daimyō-nobleman Oda Nagamasu [織田長益; 1547 ~ 1621], a younger brother of Oda Nobunaga. He originally served as an Imperial Chamberlain (jijū [侍従], for which he received the junior grade of the Fourth Rank). He converted to Christianity (taking the name of John) in 1588, and was known as Urakusai [有樂齋] after he retired from public life in 1590.

Urakusai was also a chajin, and had been a close personal friend of Rikyū’s since when Nobunaga was alive. He was also one of the few people whom Hideyoshi treated with perpetual deference.

³Ryūami [立阿彌].

This refers to the man known as Ise-ya ・ Ryūami [伊勢屋・立阿彌], who was a machi-shū chajin from Kyōto.

A letter written to him by Rikyū dated the Thirteenth Day of the Fourth Month suggests that he also held an official position at Juraku-tei – perhaps as one of Hideyoshi’s sadō [茶頭]. Thus he was also an individual who might have private access to Hideyoshi, at least occasionally.

Ryūami’s name is found in a number of other documents from this period, such as the Tennōji-ya Kai Ki [天王寺屋會記] and Tsuda Sōkyū’s diary of his own gatherings (the Tsuda Sōkyū Ji-kaiki [津田宗及自會記]), showing that he was indeed a serious practitioner of chanoyu. He also appeared as a guest at another of Rikyū’s gatherings (that is described in the Rikyū Hyakkai Ki), in the morning of the 20th day of the Eleventh Month of Tenshō 18.

⁴Yojō-han [四疊半].

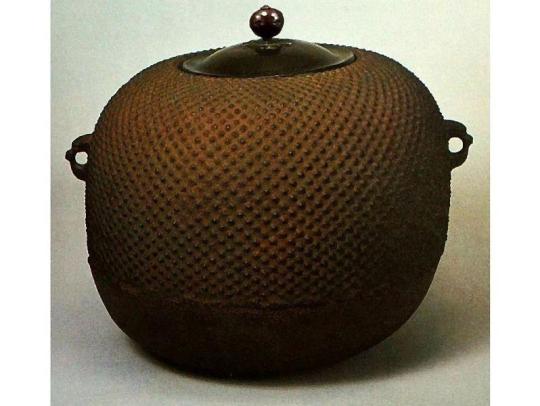

⁵Hairyō gama [拜領釜].

This small kama (which had originally been made as a kiri-kake gama for use on a large teteu-buro) was suspended over the ro on a bamboo jizai (shown below in an Edo period sketch),

using Rikyū's bronze kan [鐶] and tsuru [弦].

⁶Seitaka chawan [せい高茶碗].

This is the same kuro-chawan that Rikyū received from Chōjirō at the end of the previous year.

⁷Chaire ・ Konoha-zaru [茶入・木の葉ざる].

While this karamono nasu-chaire [唐物茄子茶入] is usually depicted resting on a karamono tsui-koku chaire-bon [唐物堆黒茶入盆] today, the tray was not paired with this chaire until the Edo period, and so has nothing to do with Rikyū’s tastes or preferred usage (though the opposite is generally implied in the presentations). Rikyū, in fact, used this chaire without a tray, with the chashaku resting on the lid as usual.

He thus would also have used an ordinary ori-tame [折撓] with this chaire (though the chashaku is not mentioned in the kaiki), one that he had made by himself.

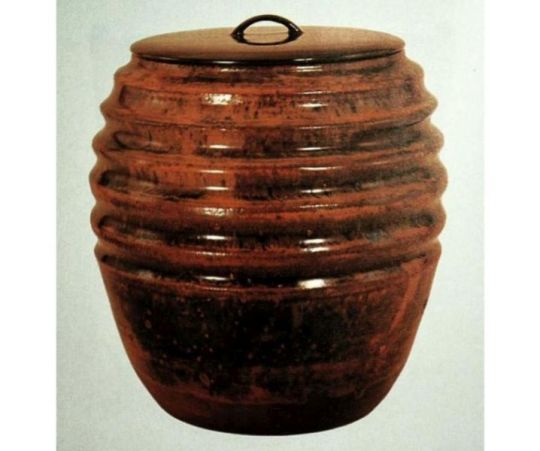

⁸Seto mizusashi [瀬戸水さし].

⁹Usucha ・ Tenka-ichi [うす茶・天下一].

Tenka-ichi [天下一] refers to Hideyoshi's lacquer artist Tenka-ichi ・ Seiami [天下一・盛阿彌].

This lacquered nakatsugi seems to have been an exact copy of the original shin-nakatsugi that was used by Shukō, hence Rikyū's esteem.

Serving usucha in a separate temae* was not Rikyū’s usual way of doing things, and he probably did so on this occasion as a way to encourage the guests to linger and discuss something -- something very important or perhaps urgent -- as night deepened†. ___________ *When Rikyū served usucha during the same temae -- what is now known as tsuzuki-usucha [續き薄茶] -- he always did so using the tea remaining in the chaire from the service of koicha. Preparing a separate container of matcha for usucha meant that this tea was served during a separate temae.

†Given the timing of this chakai -- the gathering that Rikyū hosted for Tokugawa Ieyasu (at which he was supposed to poison Ieyasu on Hideyoshi’s orders) -- was only 10 days away, Rikyū was probably looking for moral support (if not advice) from two men who were trustworthy friends. That Rikyū, of course, did not murder Ieyasu, implies that he was looking for some way to get out of the order (rather than looking for the resolve necessary to do the deed).

¹⁰Hirai Seto mizu-koboshi [平イせと水こぼし].

This entry seems to contain an error, probably the result of Rikyū's dyslexia*.

This would have actually been the same Shigaraki kame-no-futa koboshi that Rikyū had been using in recent days.

In addition to which he would have used an ordinary take-wa [竹輪] as his futaoki, as usual.

___________ *Rikyū usually wrote the individual entries his kaiki in a very specific order, as his sort of dyslexia seems to incorporate ritualized behavior as a sort of comfort device:

◦ the room, ◦ kama, ◦ mizusashi, ◦ chawan, ◦ chaire, ◦ chashaku, ◦ futaoki, ◦ koboshi, ◦ cha-tsubo, and, ◦ kakemono or hanaire.

The fact that, on this occasion, he seems to have forgotten the mizusashi, and then added it later, implies that he was extremely stressed. Writing Seto (the kamamoto where the mizusashi had been made) rather than Shigaraki, could be another manifestation of his condition, and might provide insights into his deteriorating mental state at this time.

As the plans for Hideyoshi's invasion of the continent (which Rikyū seems to have strongly opposed) began to assume their final form -- and as Hideyoshi was now demanding that Rikyū assassinate Tokugawa Ieyasu (during a chakai, no less) -- Rikyū was becoming increasingly agitated, and his frustrated impotence to do anything that could counter Hideyoshi’s will (and still preserve his life) in the face of these pending crises is beginning to show.

It is possible that the next entry in this translation of the kaiki (which, as the first of the record of the kaiseki, would have been entered into the kaiki during the chakai itself, or immediately thereafter) also contains a similar sort of solecism.

¹¹Koi no yaki-mono [鯉ノやき物].

Koi no yaki-mono [鯉の焼物] means charcoal-grilled carp.

While it is possible to grill carp, this generally was not done*. Thus, while Rikyū wrote koi, it is possible that he actually served sea bream (tai [鯛]), a fish much more suitable for preparation in this way. Perhaps this entry represents another dyslectic mistake on Rikyū’s part. __________ *This is because of the small bones that the flesh contains. When carp is prepared as sashimi, it is possible to carve the fillets to remove the bones. ��But grilling requires a thicker portion of the fillet with the skin intact, and the bones (which can not be extracted) makes this style of preparation difficult (and potentially dangerous -- especially at night, when the guest would be even less likely to be able to spot the bones).

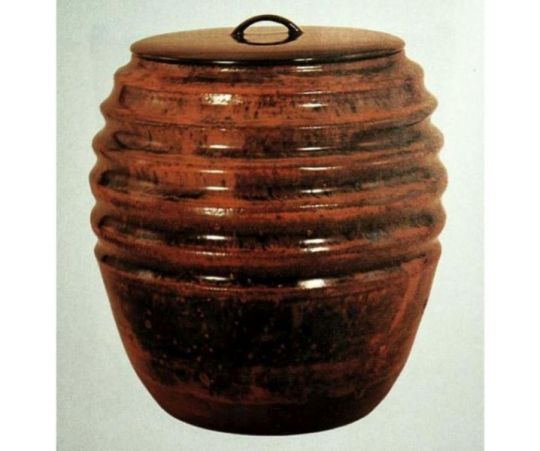

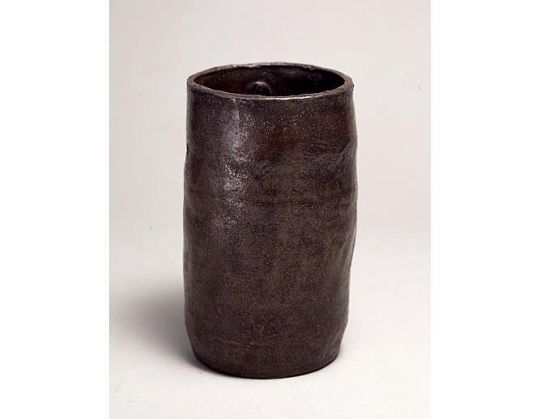

¹²Konowata [このわた].

The salted entrails (mainly the gonads and their contents) of the sea cucumber.

¹³Koma-koma jiru [こまゝゝ汁].

This seems to be what is now known as atsume-jiru [集め汁], a version of miso-shiru in which vegetables (daikon, gobō, bamboo shoots, taro petioles known as zuiki [芋茎], and other vegetables that remain fairly crisp after cooking), momen-tōfu, and things like dried fish (including kushi-awabi), are served in a stew-like mixture.

This kind of dish would provide a more substantial offering than just miso-shiru, and Rikyū likely chose it because a gathering held at this time of day included the evening meal.

According to the Hisada-bon [久田本] version of the Rikyū Hyakkai Ki, ko-tori [小鳥]* were added to the soup (rather than something like dried fish). __________ *Ko-tori [小鳥] is a generic name that refers to the various sparrows and finches that were often taken by the hawkers.

The cleaned birds were probably chopped up into small pieces (with at least the larger bones removed) and then boiled before being added to the miso-shiru.

¹⁴Meshi [めし].

Steamed rice.

¹⁵Dengaku [でんがく].

Dengaku [田樂] is a general name for a cooking style in which grilled food is painted with a miso-based glaze* while it is cooking. This was originally a folk dish that had only recently been adopted by the upper classes. Dengaku, then, would have been an interesting and quite novel dish to serve as the hiki-mono.

Rikyū does not say precisely what sort of food was used, but pieces of momen-tōfu [木綿豆腐] threaded onto bamboo skewers seems a likely candidate, since the same tōfu would also have been included in the miso-shiru that was served earlier. __________ *A mixture of miso (white or red, or a blend of both, according to preference and the food that is being cooked), sugar, mirin, and sake [酒]: traditionally roughly one part each of sake, mirin, and sugar are combined with two parts of miso to make the dengaku glaze (though the amount of sugar may be increased or decreased to taste -- in Rikyū’s day blocks of sugar resembling tallow were imported from China, and so this commodity was both costly and rare, and consequently used sparingly: if a sweeter taste was preferred, one used freshly made white miso, which is naturally sweet, though it begins to loose its sweetness several days after being made).

The pasty glaze is painted onto the upper side, and the tōfu is not turned over until after the paste has dried (so that it will not drip off). It is cooked for a short time with the glazed side facing the fire, until the sugar in the miso-glaze begins to caramelize, and should be served immediately after while it is still hot.

¹⁶Fu-no-yaki [ふのやき].

Rikyū's wheaten crêpes, spread with sweet white miso or miso-an, and then rolled or folded into bite-sized pieces.

¹⁷Yaki-guri [やきくり].

Roasted chestnuts.

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

I always eat well when traveling with chef hubby- This sashimi plate included the three Japanese delicacies-“Konowata” sea cucumber, Uni and “Karasuma”dried Mullet Roe. Kanazawa sea food is delicious!🍣 (at 味処 山下) https://www.instagram.com/p/BseXmgWh-Uv/?utm_source=ig_tumblr_share&igshid=jo25a09yrjgy

0 notes

Text

[Tradu] Monsta X - Revista ‘Mini’ Edición Junio // Debut Japonés de Monsta X

<Detrás de Cámaras>

Reporte del periodista sobre el photoshoot de Monsta X

Antes del photoshoot, Minhyuk vino temprano del cuarto de maquillaje para aprender japonés del traductor. Cuando se dio cuenta de la presencia de los entrevistadores, nos saludó enérgicamente.

Cuando los sorprendimos con una torta de felicitaciones por su debut japonés, sus ojos se pusieron brillosos. Verlos cargar la torta y tomarse fotos fue muy reconfortante.

Cuando el photoshoot empezó, se nos salió un “Wow, Hyungwon es muy alto y su cara es muy pequeña~”. ¡Al escuchar eso, él se volteó rápido hacia nosotros y nos regaló una sonrisa matadora!

Shownu era muy lindo cuando se movía tímidamente alrededor siguiendo las indicaciones del fotógrafo de caminar libremente. ¡Jooheon mostró mucha actitud para posar así como la muestra en el escenario! ¡No importara como se moviera se veía cool!

Para la toma de polaroid, Kihyun nos preguntó en japonés “Por favor sácame una bonita (sonrojo)”. Escuchando a Kihyun, Changkyun lo copió diciendo (en japonés) “Por favor tómame bonito (sonrisa).”

Wonho mostró un lado masculino cuando escogió rápidamente cual polaroid usar incluso antes de que las fotos salieran. Bueno, un ikemen es un ikemen en cualquier foto, ¿cierto?

<Entrevista Completa>

- ¡Felicitaciones en su muy esperado debut japonés!

Todos: ¡Gracias! (aplauso aplauso aplauso) Shownu: Estamos nerviosos y emocionados al mismo tiempo por nuestro debut. Como si estuviéramos empezando de cero, ¡estamos muy encendidos! Minhyuk: Creo que hasta ahora muchas monbebes japonesas han venido hasta Corea sólo para vernos. Pero a partir de ahora, trabajaremos incluso más duro para ser nosotros los que vayamos hacia ustedes.

- Por favor cuéntanos algo que haya sucedido durante la grabación de sus canciones debut japonesas ‘Hero’ y ‘Stuck’.

Jooheon & Kihyun: Fue muy duro~ Jooheon: Muchas de nuestras canciones son dinámicas, pero pienso que estas dos canciones lo son aún más. Las voces de nuestra línea vocal Kihyun y Minhyuk suenan muy bien juntas así que ese es un punto fuerte. Pero la pronunciación del japonés es muy difícil. Como soy un rapero lo fue especialmente la parte rápida del rap. Kihyun: “ ち” (chi) y “ つ” fueron especialmente difíciles. Hyungwon: ¡ “ ぜ”(ze) y “ そ”(zo) también!*

*los sonidos ‘tsu’ ‘ze’ y ‘zo’ no existen en el coreano, así que es muy difícil para ellos pronunciarlo. Así que mayormente termina sonando como ‘chu’ ‘je’ y ‘jo’ en su lugar.

- ¿Cómo quieren que las monbebes japonesas escuchen su música?

Changkyun: Nuestra canción título es ‘Hero’, así que estamos cantándola con el sentimiento de querer proteger a nuestras monbebes. Sería genial si pudieran sentir el encanto masculino/salvaje.

- ¿Alguna meta para las promociones japonesas?

Shownu: ¡Quisiera hacer un Dome Tour! Todos: ¡¡Oooohhhhh~!! Shownu: Claro que sería difícil hacerlo por ahora, pero creo que cuanto más grande el sueño, más duro podemos trabajar por él. Todos: (asienten) Kihyun: (en japonés) Quisiera hacer un tour nacional por Japón.

{Dónde quiere ir Monsta X en Japón}

- ¿Hay algún lugar en Japón al que les gustaría ir?

Minhyuk: ¡¡Akihabara!!

- Eh (risas), ¿por qué Akihabara?

Minhyuk: Siempre he querido ir desde que era joven~ Akihabara tiene muchísimo anime, juegos, y manga, ¿cierto?... En realidad soy un otaku (risas) Jooheon: Minhyuk es un otaku de verdad~(lol) Kihyun: Quiero ir a Sapporo. Jooheon: ¡Yo también! Desde que escuché a Hongki sunbaenim de FTISLAND decir que fue a esquiar a Sapporo, siempre he querido ir. Shownu: Yo quiero ir a Yufuin. Todo: Aguastermales ♪ Aguastermales ♪ Aguas termales ♪ Hyungwon: Las aguas termales japonesas son geniales~ Quiero ir con todos los miembros. Wonho: Quisiera ir por todo el país e ir a ver a varios lugares. Changkyun: Quiero ir al monte Fuji. Y hacer snowboard ahí. Minhyuk: ¡No puedes hacer snowboard en el monte Fuji! (lol) Changkyun: Si, pensé eso. Lamento haber pensado si quiera en hacerlo en primer lugar (risas)

{Comida japonesa favorita}

- ¿Comida japonesa que les gusta?

Hyungwon: (inmediatamente) ¡Sushi! Kihyun: ¡Takoyaki! Shownu: ¡Sushi de filete de caballa! Jooheon: ¡Shishamo (esperlano)! Lo venden en Corea también. Minhyuk: (en japonés) Rollo de algas secas para mí.

- Pero tienen el kimbap* en Corea también (son platos similares)

Minhyuk: el japonés también es rico. Me gusta el temaki-sushi (tradu literal: sushi enrollado a mano) que sirven en los restaurantes de sushi~ Changkyun: Me gusta la copia en plato hondo* Como cerdo en plato hondo. Jooheon: Cerdo kakuni en plato hondo también Hyungwon: Y carne de res en plato hondo Kihyun: Y stamina en plato hondo Wonho: Me gusta el konowata** Wonho: En Japón konowata puede tener la imagen de ser un plato de acompañamiento cuando tomas (risas), pero es realmente bueno cuando lo comes con arroz blanco. Hyungwon: toda la comida japonesa es deliciosa. Changkyun: de verdad amo la comida japonesa.

*comida en plato hondo casi siempre son carne cocinada sobre arroz blanco. Ej: stamina en plato hondo son cerdo, arroz y huevo crudo. **konowata es básicamente entrañas de pepino de mar saladas.

{Hablando y aprendiendo japonés}

- Ustedes chicos hablan japonés por aquí y por allá pero ¿quién es el mejor (ichiban) en japonés?

Todos: ¡Minhyuk! Hyungwon: Él es muy bueno. Minhyuk: ¿ichiban? (preguntándole al traductor qué significa) Minhyuk: ¡Ichiban (feliz)! Pienso que no somos muy diferentes en nivel. Pero hay muchas líneas en el anime y las letras de las canciones que me interesan, así que las escribo y las memorizo.

- ¿Algunas palabras que haya aprendido recientemente?

Shownu: Aprendí ‘frío’ ‘caliente’ y ‘con sueño’ (lol) Jooheon: ‘corbatas’ (musubi). Salió en la película ‘Tu Nombre’ (Kimi no na wa) y creo que lo usaban en el contexto de ‘unir destinos’. Minhyuk: ‘sasuga’* y ‘de miedo’. Lo aprendí cuando me encontré con el capitán y peleé con él. Kihyunm: eso fue en un juego cierto (lol) Minhyuk: Sip Changkyun: ¡Yo aprendí masaka** de un anime!

*sasuga = algo así como que alguien es bueno o sobresale en algo ** masaka: similar a ‘¡no puede ser!’

{monbebes y Monsta X}

- Han pasado 2 años desde su debut japonés. ¿Qué ha cambiado desde el debut?

Kihyun: La diferencia más grande es que cuando escucho música en los sitios de streaming, puedo encontrar varias canciones de MONSTA X. Me hace muy feliz ver eso. Wonho: Pensé que iban a haber muchas penurias luego de debutar, pero una vez que lo hicimos, pudimos ser conocidos por mucha gente y tener fans que no teníamos cuando éramos trainees. Recibimos mucho amor, así que hay más felicidad que penurias. Cuando las fans nos alientan, de verdad se convierte en nuestra fuerza, así que podemos trabajar duro con ese poder. Jooheon: Yeah, ¡Monbebes juegan un papel muy grande!

- ¿De qué pueden jactarse de monbebes?

Minhyuk: Hemos hecho un concierto en Corea y fan meetings alrededor de Asia. Al principio queríamos darle poder a todos, pero el poder que monbebes nos dio de vuelta es mucho más grande.

- ¿Qué tipo de monbebes llaman tu atención?

Jooheon: Mis ojos van directamente a las monbebes que se saben los fanchants memorizados y los gritan fuerte. Pero todos nos apoyan en el escenario a su manera así que soy feliz.

- ¿Cuál ha sido la experiencia más conmovedora desde que se convirtieron en MONSTA X?

Changkyun: ¡Nuestro propio concierto! Shownu: Por supuesto que nuestro concierto, pero también nuestro tour de fanmeetings por Asia fue muy bonito. Me sentí muy conmovido de que monbebes y nosotros nos pudiéramos conocer. Hyungwon: Me sentí muy conmovido cuando monbebes hicieron un video especial para nosotros y lo pusieron en el fanmeeting.

{Celebridades con las que Monsta X es cercano}

Kihyun: Debido a que debutamos el mismo año, somos muy cercanos a SEVENTEEN. También GoT7 sunbaenim, y Ryeowook hyung de Super Junior. Shownu: Soy cercano a Heechul de Super Junior. Jooheon: Soy amigo de Jackson de GoT7. Wonho: Aunque hay muchos grupos de idols en Corea, nos llevamos bien con todos. Incluso además de las personas que hemos mencionado, hay mucha gente a la que somos cercanos. Changkyun: En primer lugar los 7 de nosotros somos muy cercanos ♪

{Momento gracioso de Monsta X}

- Cuéntennos un momento gracioso que haya sucedido entre los miembros recientemente.

Kihyun: Justo hace poco, algo realmente gracioso pasó. Resulta que un día, Jooheon and Hyungwon se habían prometido mutuamente que irían al sauna juntos... Todos: (empiezan a reírse) Kihyun: Pero justo antes del momento en que habían planeado irse, Jooheon se quedó accidentalmente dormido. Pero cuando le preguntamos luego, Jooheon dijo que él estaba viendo un sueño en el que estaba despierto y listo para ir al sauna, y Hyungwon era el que se quedaba dormido. Él continuó insistiéndole fuertemente esa historia a Hyungwon, pero en realidad, Jooheon era el que se había quedado dormido, y Hyungwon tomó pruebas de él durmiendo, así que no pudo defenderse para nada (lol). Todos: (se echan a reír)

{Monsta X como los miembros de una familia}

- ¿Si tuvieran que poner a los 7 miembros en los roles de una familia?

Kihyun: Shownu sería el abuelo, Wonho la abuela. Minhyuk: ¡Jooheon es el perro! Jooheon: ¿Perro (risas)? Kihyun: ¿Hyungwon sería como un papá un poco inmaduro? Changkyun: Ehh~ ¡¿un papá?! Minhyuk: Más sería un tío (lol). ¡Kihyun es la mamá! Kihyun: Changkyun es el hijo, y Minhyuk es la hija (lol). Todos: ¡¿Hija?! (lol)

- ¿Alguien tiene alguna objeción?

Hyungwon: (a Jooheon) ¿Estás bien con ser el perro? (lol) Jooheon: Ya que los perros son lindos estoy bien. Shownu de verdad va bien como abuelo. (risas) Wonho: No quiero admitir ser la abuela, pero si todos lo dicen, entonces debo aceptarlo (risas). Minhyuk: ¡Perfecto! ¡Perfecto!

- ¿Por qué es Kihyun la mamá?

Kihyun: Hago comida para todos. Shownu: Kihyun de verdad cuida mucho de todos. Por ejemplo, nos da comida que es buena para nuestras gargantas. Jooheon: Además, cuando comemos juntos, siempre nos pregunta qué queremos comer primero. Wonho: Kihyun hace muchas cosas de forma voluntaria así que es alguien confiable.

{El miembro más popular de Monsta X}

- ¿Quién es el más popular entre las chicas?

Minhyuk: ¡Show~~nu~~~! Hyungwon: ¡Sip, Shownu! Minhyuk: ¡SÓLO BROMEO~~~! Todos: (se echan a reír) Shownu: ¡Puedo seguir viviendo mientras tenga a monbebe! Pero creo que Wonho es por ahora el miembro más popular. Wonho: Um... No quiero admitirlo pero, podría ser verdad~ (sonrisa de satisfacción) Kihyun: Por supuesto; Wonho es muy popular (risas) Changkyun y Jooheon: ¡¿En serio?! (dudando)

{Ropa de dormir de Monsta X}

- ¿Qué usan cuando van a dormir?

Jooheon: Uso pijamas. Hyungwon: Lo mismo. Minhyuk: Siempre manga larga y pantalones. Wonho: Minhyuk es muy friolento así que usa manta larga y pantalones incluso durante el caliente verano, Changkyun: Uso shorts y polo. Wonho: Uso ropa de recuperación para dormir (recovery sleepwear). Es buena para recuperar el cuerpo de la fatiga. Shownu: uno shorts y nada arriba. Kihyun: Escuché que es mejor no usar mucha ropa para dormir y sentirse cómodo al dormir, así que uso shorts y nada arriba.

- Finalmente, ¡den un mensaje a los lectores de ‘mini’!

Shownu: Lectores de ‘mini’, debido a que habrán más oportunidades de que promocionemos en Japón en el futuro, creo que podremos vernos seguido. Shownu: (en japonés) ¡Por favor cuiden de nosotros! Wonho: Por favor den a ‘mini’ mucho amor~

English translation: potattoestorm Español: wonaboutyou (bunniesownme@tumblr) Imágenes: mxholic514

#Monsta X#shownu#kihyun#wonho#changkyun#hyungwon#jooheon#minhyuk#interview#mini magazine#entrevista#revista mini#tradu#spanish#español#japanese debut#debut japones#june edition#edicion junio

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ini Daftar Harga Teripang Terbaru di Tahun 2017

Teripang merupakan salah satu hasil laut yang diburu sejak 300 tahun silam. Produk ini memiliki rasa lezat dan daging lunak. Tidak mengherankan, biota tersebut sangat disukai masyarakat dari berbagai negara. Bahkan, ia kerap diolah menjadi beragam kuliner. Tentu hal itu membuka peluang bisnis dengan keuntungan besar karena harga teripang tergolong mahal.

Mulanya, teripang ditemukan di perairan Indo-Pasifik, tepatnya di kawasan Laut Sulawesi. Ketika itu, para nelayan setempat menemukan biota laut dengan tubuh mirip siput. Bedanya, tidak dilindungi oleh cangkang, berbentuk panjang, dan bermotif. Ia bergerak lambat, tanpa kaki, serta bertubuh licin. Lalu, orang Indonesia menyebutnya “trepang” yang kini namanya bertransfomasi menjadi teripang.

Perkembangan selanjutnya, nusantara menjual teripang ke beberapa negara, antara lain Cina, Jepang, Singapura, dan negara-negara di Eropa. Seiring dengan peningkatan ekspor, biota ini mulai ditemukan di daerah lain, yaitu perairan Nusa Tenggara, Papua, dan Aceh. Memasuki abad ke-19, ekspor teripang mencapai angka 2.000 ton. Sayangnya, kondisi tersebut hanya bertahan sampai akhir abad ke-20. Hal itu terlihat dari data di tahun 2010 yang menunjukkan angka 0,7 ton untuk kategori ekspor teripang ke Cina.

Sangat ironis, bukan? Mengingat Indonesia merupakan negara penghasil teripang terbesar di dunia. Apalagi 10% dari spesies teripang di seluruh dunia, berada di nusantara. Sementara itu, ada tujuh jenis yang memiliki nilai jual tinggi. Lalu, apa sebenarnya yang memengaruhi harga biota ini?

Faktor yang Memengaruhi Harga Teripang

Sejauh ini, permintaan teripang di Indonesia terus meningkat. Harga mahal bukan masalah bagi penggemar biota ini. Justru, mereka menjadikan itu sebuah tantangan yang harus dihadapi. Pasalnya, setiap inovasi dari produk laut tersebut bisa menghasilkan omset ratusan juta rupiah. Bayangkan saja, satu kilogram teripang kering dengan mutu paling rendah sekitar Rp30.000-75.000.

Sementara teripang kering berkualitas tinggi, nilainya mencapai jutaan rupiah per kilogram. Jika produk tersebut laku setiap hari, nominal uangnya bisa diprediksikan. Itu baru perhitungan sekelas pedagang lokal di Sumatera. Apalagi kalau dikirim ke luar negeri; pendapatan mereka lebih dari perkiraan ini.

Citra teripang sebagai makanan termahal, bukan tanpa alasan. Selain karena bernilai gizi tinggi, ada lima faktor yang memengaruhi kestabilan harga biota tersebut. Faktor tersebut, yaitu lokasi teripang di dalam laut, manfaatnya, kualitas produk, biaya produksi, dan pelestarian biota.

Lokasi teripang sangat memengaruhi harga di pasaran. Semakin dalam lautan yang diselami, nilai jualnya kian tinggi. Apalagi hewan mirip timun ini mampu hidup hingga kedalaman 30 meter di bawah permukaan laut. Tentu perjuangan para nelayan ketika berburu biota tersebut, perlu mendapatkan penghargaan. Salah satunya dengan melabelkan harga selangit pada produk teripang.

Selanjutnya faktor manfaat dari kandungan yang ada di dalam tubuh teripang. Biota ini bisa menyembuhkan berbagai macam penyakit, salah satunya kanker. Pasalnya, hewan tersebut mengandung tritepenoid. Senyawa ini mampu membunuh sel kanker hingga 95% karena termasuk Frondoside A, zat pengganti kemoterapi. Selain itu, teripang juga dapat mempertahankan elastisitas kulit wajah serta mencegah penuaan dini.

Faktor ketiga adalah kualitas produk pascapanen. Semakin bagus performa teripang, nilai jualnya pun bertambah. Sebaliknya, jika banyak cacat di tubuh teripang, berpotensi menurunkan harga di pasaran. Terlebih untuk memenuhi standar pemasaran di luar negeri. Teripang tersebut harus bermutu tinggi.

Faktor yang tidak kalah penting, yaitu biaya produksi. Disinyalir, pengeluaran untuk proses pengolahan teripang, masih tinggi. Hal ini tentu memengaruhi harga jual di pasaran. Apalagi sangat sulit mencari investor yang mau mendanai budi daya teripang.

Terakhir, faktor pelestarian biota. Sampai saat ini, jumlah petani yang mau membudidayakan teripang masih sedikit. Mayoritas hanya berburu, lalu menjual langsung. Padahal, hal itu berpotensi menyebabkan kelangkaan teripang di laut. Untuk mengatasi masalah tersebut, pemerintah pun membuat aturan seputar perburuan teripang.

Harga Teripang di Berbagai Negara

Tidak dimungkiri, nilai jual teripang di mancanegara bisa mencapai puluhan juta rupiah. Salah satunya di Cina, biota ini dijual Rp 34 juta per kilogram. Mereka mengimpornya dari Australia. Harga teripang yang mahal tersebut disebabkan oleh kelangkaan produk, sedangkan permintaan bertambah. Terlebih, kebutuhan teripang di pasar Tiongkok terus meningkat setiap tahun.

Fenomena mahalnya teripang juga terjadi di Jepang. Satu kilogram produk teripang kering sekitar Rp 500 ribu sampai Rp 24 juta. Setiap satu kilogram bisa berisi 5-10 ekor, tergantung keseragaman ukuran. Bahkan, sebagian besar orang Jepang mengonsumsi biota ini dalam keadaan segar. Pasalnya, selain berprotein tinggi, hewan tersebut memiliki rasa lebih lezat dari daging ikan.

Lain lagi cerita tentang teripang di Korea. Sebagian biota ini diimpor dari Indonesia, tepatnya Pulau Derawan. Ketika memasuki pasar negeri ginseng, harganya mencapai Rp 2 jutaan per kilogram. Sementara itu, produk termurah dilabeli Rp200.000 per kilogram. Karena itu, para nelayan asal Derawan mampu meraup omset ratusan juta rupiah per hari.

Sementara itu, nilai jual teripang kering di Singapura sekitar Rp500.000-12.000.000 per kilogram. Negara ini juga menyajikan makanan olahan teripang di berbagai restoran seafood. Singapura kerap kali menggunakan jenis teripang Babel (Bangka Belitung) asal Indonesia yang konon rasanya sangat lezat.

Ini yang Hasil Olahan Teripang dan Harganya

Sebagai negara penghasil teripang terbesar, Indonesia mengolahnya menjadi berbagai bentuk makanan kering. Salah satu produk olahan yang paling diminati adalah kerupuk teripang. Camilan tersebut mudah ditemukan di daerah Kenjeran, Surabaya. Bentuknya menyerupai rambak, tetapi lebih tipis dan renyah. Biasanya, dijual dalam kemasan 100-500 gram.

Harga jual kerupuk teripang sekitar Rp16.000-27.000 per bungkus. Produk tersebut bisa dibeli di swalayan, toko camilan, maupun kawasan pantai Jawa Timur. Ada juga kemasan 1000 gram yang dibanderol Rp130.000. Penggemar makanan ringan ini berasal dari berbagai kalangan. Tak jarang, wisatawan asing membeli kudapan tersebut ketika berkunjung ke Surabaya. Meskipun sudah diolah, nilai gizi kerupuk teripang tidak berkurang sedikit pun.

Selain kerupuk, teripang juga bisa disantap dalam bentuk kering. Makanan ringan ini kerap disebut gonad kering atau konoko. Proses memasaknya didahului dengan perebusan hingga pengasapan. Kudapan konoko ini dikonsumsi dengan beraneka bumbu sehingga rasanya gurih dan enak.

Di Jepang terdapat produk olahan teripang yang paling diminati, yaitu konowata. Makanan ini terbuat dari organ dalam teripang. Pengolahannya melalui proses fermentasi selama kurang lebih satu minggu. Kudapan tersebut dikemas dalam botol dengan berat bersih 65 gram. Harganya sekitar US$100 atau Rp120.000 per kemasan.

Kini, olahan teripang semakin beragam. Tidak hanya dalam bentuk kering, tetapi juga kemasan daging kaleng. Seperti halnya sarden atau ikan tuna kalengan, produk tersebut bisa langsung dimasak. Di samping itu, ada teripang beku yang diawetkan dengan suhu tertentu. Harga jualnya sekitar Rp100.000-125.000 per kilogram.

Teripang beku digunakan untuk bahan makanan ala restoran. Beberapa contoh yang bisa disajikan, antara lain sup teripang, haisom sup jamur, teripang masak hioko, dan haisom sancam saus tiram. Kalau beli masakan tersebut di restoran kelas bintang lima, pasti harganya lebih mahal, sekitar Rp 300 ribuan per porsi. Bahkan, ada yang sampai setengah juta rupiah.

Meskipun harganya selangit, kuliner haisom tetap diminati. Aromanya yang sedap didukung dengan rasa gurih dan kenyal. Makanan tersebut bisa ditemukan di sepanjang Pantai Kenjeran atau Pulau Madura.

Tahapan Penanganan Teripang agar Harga Jualnya Tinggi

Pengolahan dasar teripang perlu diperhatikan untuk menaikkan harga jual. Pasalnya, konsumen kerap mengutamakan kualitas dibandingkan dengan merek. Selain itu, sedikit kesalahan dalam mengolah teripang, bisa mengurangi mutunya. Berikut ini yang harus dilakukan sebelum memasarkan teripang.

1. Langkah pertama adalah menyortir teripang hasil tangkapan tradisional. Upayakan biota tersebut terlihat bersih dan mengilap. Kemudian, pisahkan teripang yang tubuhnya tampak terluka. Pasalnya, nilai jual teripang ini akan menurun jika dipasarkan dalam bentuk segar.

2. Langkah kedua, buanglah isi perut teripang. Tahapan ini bisa dilakukan sebelum atau sesudah proses perebusan. Cara membelahnya, yaitu dengan membuat garis vertikal atau memanjang. Setelah semua organ dalam dikeluarkan, bersihkan memakai air tawar yang mengalir. Hati-hati saat melakukan proses ini karena berpotensi merusak tekstur tubuh biota.

3. Selanjutnya, rebuslah teripang menggunakan air mendidih yang dicampur garam. Biarkan selama 30 menit sampai tubuh teripang terasa lunak. Setelah merebus, tiriskan hingga tidak menyisakan air sedikit pun.

4. Tahapan berikutnya, yaitu pengasapan selama 10-20 jam. Suhu minimalnya sekitar 60-80 o Upayakan tempat pengasapan dalam kondisi tertutup. Tujuannya agar tidak terkontaminasi kotoran atau debu dari luar.

5. Langkah terakhir adalah mengemas teripang ke dalam karung. Setelah itu, menyimpannya di gudang dengan cara ditumpuk.

Daftar Harga Teripang di Indonesia Berdasarkan Jenisnya

Sekitar 90% teripang yang dijual di luar negeri berasal dari Indonesia. Harga teripang di nusantara tidak sama, tergantung jenisnya. Kurang lebih ada 15 macam teripang yang diperdagangkan di negeri ini. Salah satunya teripang koro. Nilai jual biota tersebut mencapai Rp2.500.000 per kilogram dengan isi 3-8 ekor.

Ada juga teripang pasir yang harganya Rp3.800.000 per kilogram. Setiap kemasan berisi 5-10 ekor. Kalau menginginkan nilai jual murah, Anda bisa membeli teripang sepatu. Hingga tahun 2016, nilai jual teripang ini hanya Rp54.500-225.000 per kilogram. Selain itu, terdapat teripang cera hitam yang dibanderol Rp425.000 dengan isi 40-45 ekor. Meskipun berukuran kecil, cera hitam banyak peminatnya.

Teripang cera hitam juga memiliki khasiat mengobati berbagai macam penyakit. Kandungan kolagennya mampu meregenasi sel-sel kulit mati dengan cepat. Karena itu, tidak sedikit yang menggunakannya dalam produk kecantikan.

Beberapa jenis teripang lain yang diproduksi Indonesia, antara lain gosok, susu, emas, kapuk, nanas, kapuk bola, duri, dan jepung. Daftar harga teripang selengkapnya, tercantum dalam tabel di bawah ini.

Jenis Teripang Kisaran Harga 1 Kilogram Teripang gosok Rp1.900.000-2.900.000 Teripang emas Rp3.350.000-3.800.000 Teripang susu Rp1.900.000-2.300.000 Teripang kapuk Rp62.000-325.000 Teripang nanas Rp975.000-1.00.000 Teripang sepatu Rp545.000-225.000 Teripang duri Rp2.000.000-2.500.000 Teripang jepung Rp244.000-300.000 Teripang kapuk bola Rp230.000-450.000 Teripang pisang abu Rp450.000-600.000 Teripang tengah Rp900.000-1.000.000 Teripang bintik Rp450.000-600.000

*Estimasi Harga Teripang Di Indonesia

Itulah ulasan mengenai harga teripang di Indonesia dan beberapa negara di dunia. Keberadaan teripang merupakan bukti kekayaan lautan. Kini, populasi teripang semakin berkurang. Karena itu, perlu menjaga kelestariannya dengan cara melakukan budi daya. Semoga artikel ini bermanfaat.

The post Ini Daftar Harga Teripang Terbaru di Tahun 2017 appeared first on Supplier Teripang.

0 notes

Text

A tea-pairing lunch, a sake-pairing dinner: Hong Kong menu specials

How to pair tea, and sake, with food - find out at Hong Kong special lunch and dinner; plus a Hawaiian dinner buffet How to pair tea, and sake, with food - find out at Hong Kong special lunch and dinner; plus a Hawaiian dinner buffet Tenku RyuGin pairs rare teas with Japanese cuisine, Above & Beyond at the Hotel Icon pairs dishes including kung pao lobster with sake, and Hawaiian buffet pairs baked lobster and spam Tenku RyuGin in the ICC in Tsim Sha Tsui is featuring a tea-pairing kaiseki lunch on July 22 and 23. The rare teas are sourced from China, Darjeeling, Taiwan and Japan, and include 2017 spring-picked meng ding gan lu from Sichuan, and 2017 spring-picked red tea from Darjeeling's Gopaldhara The teas will be paired with dishes such as an appetiser platter of sea urchin cracker, fruit tomato, sakuramasu crispy kadaif , foie gras with figs, konowata with seaweed, and peach and ... (more) http://dlvr.it/PVN8PC

0 notes

Photo

このわた (Konowata)

Konowata is a type of shiokara, food products made from various marine animals and innards preserved in a brown viscous paste and heavily salted and fermented. This one is made from sea cucumber innards.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Appendix: the Rikyū Hyakkai Ki, Part 34: (1591) Intercalated First Month, Sixteenth Day, Midday.

94) Intercalated First Month, Sixteenth Day; Midday¹.

○ Kuwayama shūri dono [桑山修理殿]², Aoki Kii-no-kami [青木紀伊守]³, Maeno Izumo-no-kami dono [前野出雲守殿]⁴.

○ 4.5-mat [room]⁵.

○ Hairyō kama [拜領釜]⁶; ◦ Shigaraki mizusashi [しがらき水指]⁷; ◦ chaire ・ ko-natsume [茶入・小ナツメ]⁸; ◦ kuro-chawan [くろ茶碗]⁹; ◦ ori-tame [をりため]¹⁰; ◦ take-no-wa [竹のわ]¹¹; ◦ Hashi-date [はしだて]¹².

○ Kamaboko [かまぼこ]¹³; ◦ kō-no-mono [かうのもの]¹⁴; ◦ konowata [このわた]¹⁵; ◦ miso-yaki jiru [みそ燒汁]¹⁶; ◦ meshi [めし]¹⁷.

○ Hikite [引て]: ◦ koi no sashimi [鯉のさしみ]¹⁸.

○ Kashi [菓子]: ◦ fu-no-yaki [ふのやき]¹⁹; ◦ kuri [くり]²⁰.

_________________________

¹Urū-shōgatsu jūroku-nichi ・ hiru [閏正月十六日・晝].

The Gregorian date was March 16, 1591.

²Kuwayama shūri dono [桑山修理殿].

This was the daimyō-nobleman Kuwayama Shigeharu [桑山重晴; 1524 ~ 1606], who was Master of the Office of Palace Repairs (shūri-daibu [修理大夫], which earned the incumbent the junior grade of the Fifth Rank).

He had also been a senior councilor of (the late) Toyotomi Hidenaga (who had died, of illness, during the previous month), whose sagacity was respected by Hideyoshi as well.

³Aoki Kii-no-kami [青木紀伊守]*.

This refers to the daimyō-nobleman Aoki Kazunori [青木一矩; ? ~ 1600], who was also known as Aoki Hidemasa [青木秀政]. He served as both the Governor of Kii Province (Kii-no-kami [紀伊守]), and as an Imperial Chamberlain (jijū [侍従]). He held the junior grade of the Fifth Rank.

Aoki Kazunori was also a disciple of Rikyū, and the owner of a number of meibutsu utensils. The striped cloth known as Aoki kantō [青木カントウ], shown above, is named after him. __________ *In the Hisada-bon, his name is entered as Aoki Kii-no-kami dono [青木紀伊守殿] -- including the suffix appropriate to his rank (which is missing in the other manuscripts).

⁴Maeno Izumo-no-kami dono [前野出雲守殿].

This was Maeno Kagesada [前野景定; ? ~ 1595], a military commander (bushō [武将]) and senior vassal of the Toyotomi family. He was the Governor of Izumo (Izumo no kami [出雲守]), as Rikyū mentions here; and he also served as the chief advisor (karō [家老]) to Toyotomi Hidetsugu [豊臣秀次; 1568 ~ 1595] -- and shared in his lord's unfortunate fate (being ordered to commit seppuku about one month after Hidetsugu).

⁵Yojō-han [四疊半].

⁶Hairyō kama [拜領釜].

As on previous occasions, this kama was suspended over the ro on Rikyū’s abura-dake jizai [油竹自在] -- a jizai made of the oil-stained bamboo taken from an old farmhouse kitchen (when the roof was restored) -- using Rikyū’s bronze kan and tsuru (shown above).

⁷Shigaraki mizusashi [しがらき水指].

⁸Chaire ・ ko-natsume [茶入・小ナツメ].

The natsume would have been tied in a shifuku at the beginning of the temae.

⁹Kuro-chawan [くろ茶碗].

Though* the bowl is not described further by Rikyū, this most likely was the same deep kuro-chawan that Rikyū had received from Chōjirō at the very end of the previous year† -- in other words, the chawan now usually known as Seitaka-kuro [背高黒] (or, sometimes, Seitaka-zutsu [背高筒]).

___________ *Perhaps the better word would have been “because” -- Rikyū seems inclined to leave out such details when he has been using the same utensil again and again over the course of a number of successive chakai.

†In most of the previous records of chakai where he used this chawan, Rikyū actually wrote “kuro-chawan” [くろ茶碗; or, in one case, 黒茶碗 -- using the kanji for kuro, “black”]. The adjective “seitaka” [せいたか] was added interlineally, apparently as an afterthought (or possibly later, perhaps even by the person who was making a copy of the kaiki -- in order to clarify the matter based on what may have been an oral tradition that derived from the words of one of the guests who had been present at one of the gatherings).

Since the original Rikyū manuscript has long been lost (and possibly the first of the copies on which the others were based as well), there seems to be no way to resolve this question.

¹⁰Ori-tame [をりため].

As usual, a chashaku with a noticeable bend in the middle of the handle (at the node), so that the shaft would contact the rounded lid of the natsume in two places, thus keeping it from spinning when released by the host’s hand.

¹¹Take-no-wa [竹のわ].

And though not mentioned, Rikyū probably used a mentsū [面桶] as his mizu-koboshi.

¹²Hashi-date [はしだて].

This was Rikyū's best cha-tsubo which, as has been mentioned before, was lost during the lifetime of Sen no Sōtan -- who documents this fact in one of his surviving letters.

¹³Kamaboko [かまぼこ].

Steamed fish-paste, which was usually deep fried in oil shortly before being served in Rikyū's period.

¹⁴Kō-no-mono [かうのもの].

Home-made pickled vegetables -- the cut pieces were put into a brine solution for two or three days, and then drained and served.

¹⁵Konowata [このわた].

This dish consists of the salted gonads (and their contents) of the sea cucumber. It was a popular side-dish to accompany the drinking of sake [酒].

¹⁶Miso-yaki jiru [みそ燒汁].

This is a kind of miso-shiru containing julienned daikon and one large piece* of grilled momen-tōfu that is placed in the center of the bowl (with the scorched side facing upward). __________ *Usually an eighth of a cake. The entire cake of tōfu is usually grilled on the top and bottom -- often by the tōfu shop. The cake was then divided into an upper half and a lower half, and each half was then cut into quarters. One of the pieces was placed in each bowl of miso-shiru.

¹⁷Meshi [めし].

Steamed rice.

¹⁸Koi no sashimi [鯉のさしみ].

As before, this is the dish now known as koi-arai [鯉洗い].

In Rikyū's day most people only ate in the morning, and again at dusk. Perhaps the guests indicated that they were still a little hungry, however, and Rikyū decided to serve them sashimi of carp (which can be prepared in a fairly short time -- live carp generally being kept in a pond in the kitchen garden).

¹⁹Fu-no-yaki [ふのやき].

Rikyū's small wheat crepes filled with sweet white miso or miso-an.

²⁰Kuri [くり].

Probably yaki-guri [焼栗], chestnuts roasted in a shallow pan by agitating them over a charcoal fire with hot pebbles (and possibly several small pieces of imported Chinese brick-sugar, which would melt and coat both the pebbles and the nuts, which gives the chestnuts a slightly sweet, molasses-like flavor).

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Appendix: the Rikyū Hyakkai Ki, Part 25: (1591) Intercalated First Month, Third Day, Morning.

85) Intercalated First Month, Third Day; Morning¹.

○ Matsui Sado dono [松井佐渡殿], alone².

○ Two-mat room³.

○ Arare gama [あられ釜]⁴; ◦ Seto mizusashi [瀬戸水指]⁵; ◦ Ko-mamori no chawan [木守ノ茶碗]⁶; ◦ katatsuki ・ shi-hō-bon [肩衝・四方盆]⁷; ◦ ori-tame [をりため]⁸; ◦ take-no-wa [竹のわ]⁹; ◦ hirai Shigaraki mizu-koboshi [平いしがらき水こぼし]¹⁰; ◦ Yoku-ryō-an bokuseki [欲了庵墨跡]¹¹.

○ Kushi-awabi [くしあはび]¹²; ◦ konowata [このわた]¹³; ◦ fukuto-jiru [ふくと汁]¹⁴; ◦ meshi [めし]¹⁵.

○ Kashi [菓子]: ◦ fu-no-yaki [ふのやき]¹⁶; ◦ yaki-guri [やきくり]¹⁷; ◦ iri-kaya [いりかや]¹⁸.

_________________________

¹Urū-shōgatsu mikka ・ asa [閏正月三日・朝].

The corresponding Gregorian date of this chakai was February 26, 1591.

²Matsui Sado dono ・ hitori [松井佐渡殿・一人].

This refers to Matsui Yasuyuki [松井康之; 1550 ~ 1612], at this time a retainer of Hosokawa Fujitaka [細川藤孝; 1534 ~ 1610]*, who served as Governor of Sado (Sado no kami [佐渡守])†.

Sado-no-kuni [佐渡の國] (Sado Province), which consists of a small island north-west of the main Japanese island of Honshū, is shown in red on the above map. It was administratively part of the Hokuriku-dō [北陸道] (the rest of which is shaded with green), one of the shichi-dō [七道]‡. __________ *Matsui Yasuyuki's career extended from the Muramachi bakufu to the Tokugawa bakufu, and he was successively a retainer of Ashikaga Yoshiteru [足利義輝; 1536 ~ 1565] (the thirteenth Ashikaga shōgun), Ashikaga Yoshi-aki [足利義昭; 1537 ~ 1597] (the fifteenth and last Ashikaga shōgun), Oda Nobunaga [織田信長; 1534 ~ 1582], Hosokawa Fujitaka [細川藤孝; 1534 ~ 1610], and finally Fujitaka's son Hosokawa Tadaoki [細川忠興; 1563 ~ 1646].

†This governorship did not earn the incumbent court rank.

‡Since ancient times, the Japanese islands had been divided into the so-called five home provinces (the go-ki [五畿], over which the imperial court had more or less direct control), and a further seven regions (or dō [道]) governed by a viceroy who was appointed to oversee the imperial interests. Taken together, this administrative system is referred to as the go-ki shichi-dō [五畿七道].

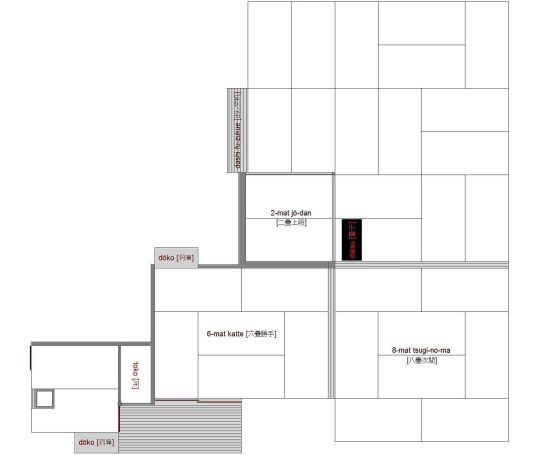

³Nijō shiki [二疊敷].

For this chakai, Rikyū borrowed extensively from the tori-awase of the gathering that he hosted (in the same room) the previous evening -- with two important differences: the chaire; and, at this gathering a kakemono was displayed in the toko.

⁴Arare gama [あられ釜].

⁵Seto mizusashi [瀬戸水指].

⁶Ko-mamori no chawan [木守ノ茶碗].

⁷Katatsuki ・ shi-hō-bon [肩衝・四方盆].

This is the chaire now known as the Enjō-bō katatsuki [圓乗坊 肩衝], used on the matsu-no-ki bon [松ノ木盆] that Rikyū provided for it.

This ko-Seto katatsuki [古瀬戸肩衝]* had originally been one of Nobunaga's† personal treasures -- and was being used by him to serve usucha when the Honnō-ji (where he was staying) was attacked by Akechi Mitsuhide -- and its association with the monk Enjō-bō Sōen [圓乗坊 宗圓; his dates of birth and death are unknown] is only due to the fact that he rescued this chaire‡ from the ashes of the Honnō-ji, and repaired it with lacquer. __________ *The term ko-Seto chaire [古瀬戸茶入] refers to chaire made according to the specifications of the expatriate Korean chajin, who arrived in Japan during the Buddhist/pro-republican persecutions of the mid-fifteenth century, by the potters working at the Seto kilns (in modern-day Aichi Prefecture), near Nagoya.

†As mentioned above, Matsui Yasuyuki had formerly been a retainer of Oda Nobunaga, so the use of this chaire would have had a special significance for him.

‡As well as the karamono bunrin chaire [唐物文琳茶入] now known as the Honnō-ji bunrin [本能寺文琳] -- which Nobunaga had used to serve koicha on the same occasion.

⁸Ori-tame [をりため].

The chashaku would have been specifically made (by Rikyū) to conform to the dimensions of the bon-chaire with which it was used.

⁹Take-no-wa [竹のわ].

¹⁰Hirai Shigaraki mizu-koboshi [平いしがらき水こぼし].

This mizu-koboshi was about the size of the basins (usually made of beaten copper or bronze; though mage-mono pieces are also seen from time to time) that are known as chakin-darai [茶巾盥] (and today used only to clean the chakin and chasen in the mizuya). All of these vessels were originally used as koboshi during Jōō’s period (and before -- when up to ten guests might be served at a single time by the host in his 4.5-mat room*), and their use as chakiin-darai only dates from the Edo period (when the fashions of the day meant that smaller koboshi were preferred). The large mentsū [面桶] was of a similar size (and fell out of use at the same time). ___________ *The original ō-kame-no-futa mizu-koboshi [大甕ノ蓋水飜], shown below, which was used by Jōō at his early chakai, was 4-sun in diameter on the bottom, 7-sun in diameter at the mouth, and 3-sun 5-bu deep.

This piece was of Korean ongi [온기 = 溫器] ware.

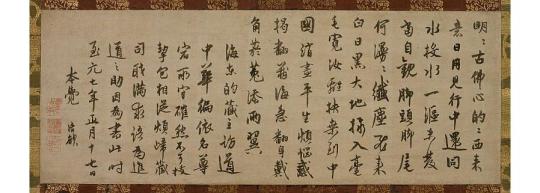

¹¹Yoku-ryō-an bokuseki [欲了庵墨跡].

This scroll was written by the Yuan period Chinese monk Liǎo-ān Qīng-yù [了庵清欲; 1288 ~ 1363].

The text is an example of a hōgo [法語], Zen instructions or admonitions.

¹²Kushi-awabi [くしあはび].

Abalone (awabi [鮑]), sun-dried on a pair of bamboo skewers (kushi [串]), that has been reconstituted by boiling in broth, sliced into bite-sized pieces before being served.

¹³Konowata [このわた].

The salted gonads (and their contents) of the sea cucumber (a type of echinoderm, and relative of the starfishes and urchins).

¹⁴Fukuto-jiru [ふくと汁].

The name fukuto, or fukutō [河豚頭] -- the modern name of this fish is pronounced fugu [河豚] -- refers to the pufferfish or globefish.

After removing the liver and gonads (in which the fish's poison is concentrated to highly toxic levels), the fish is chopped into pieces and boiled, together with pieces of daikon and crushed garlic; freshly chopped leeks were added just before the soup was served.

¹⁵Meshi [めし].

Steamed rice, measured out into an individual portion by pressing the rice into a copper mossō [物相]. The resulting shapes were often fanciful and seasonally appropriate (things such as pine trees, cherry blossoms, and bottle-gourds, among others), and may have been decorated by sprinkling on things like sesame seeds and other condiments before serving.

¹⁶Fu-no-yaki [ふのやき].

Rikyū's wheat crêpes, spread with sweet white miso (or possibly miso mixed with strained white beans) before being folded into bite-sized pieces.

¹⁷Yaki-guri [やきくり].

Chestnuts roasted in a pan with pebbles, over a charcoal fire.

¹⁸Iri-kaya [いりかや].

Iri-kaya [煎り榧] means the roasted nuts of the kaya [榧] tree (known variously as the Japanese nutmeg yew, and Japanese allspice tree).

The nuts were roasted by placing them in a metal basket which was agitated over a charcoal fire.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rikyū Chanoyu Sho, Book 6 (Part 62): Rikyū’s Hyaku-kai Ki, (1591) First Month, Ninth Day; Morning.

62) The same, Morning of the Ninth Day [同九日之朝]¹.

○ [Guests: .]²

○ 2-mat room³.

○ The chanoyu was the same as before⁴.

○ Kushi-awabi [くしあわひ], soup (miso-yaki [みそやき]), rice⁵.

○ Hikite [引テ]: ◦ konowata [このわた]; ◦ ko-tori senba-iri [小鳥せんばいり]⁶.

○ Kashi: fu-no-yaki [ふのやき], kuri [くり]⁷.

_________________________

◎ This gathering was given for Horio Tadauji (referred to here by his yōmei [幼名], or childhood name, as Misuke*), the son of one of Hideyoshi's counselors, perhaps to occupy the young man while he waited to be presented to Hideyoshi by his father -- so he could offer New Year’s greetings. The gathering includes the service of breakfast, though the service of sake is notably truncated. __________ *The boy was just thirteen years of age at the time of this chakai, so this was a year or two before the age at which he would celebrate his gempuku [元服] (coming-of-age ceremony).

¹Onaji kokonoka-no-asa [同九日之朝].

It is still the First Month of Tenshō 19 [天正十九年]. The date corresponds to February 2, 1591.

²No guests are listed in the Rikyū Chanoyu Sho. However, two guests are mentioned in the manuscript versions of this kaiki: Horio Misuke, and a man referred to only as Ki-sai*.

▵ Horio Misuke dono [堀尾彌介殿]†: this was the yōmei [幼名] (childhood name) of the samurai (he eventually attained the rank of bushō [武将], military commander, and daimyō [大名], though when he participated in this gathering he was just a boy) who is more generally known as Horio Tadauji [堀尾忠氏; 1578 ~ 1604]. His father was one of Hideyoshi's counselors (Horio Yoshiharu [堀尾吉晴; 1543 ~ 1611), and thus Tadauji/Misuke had been destined to be one of Hideyoshi's personal retainers from birth. He ultimately served as Governor of both Shinano (Shinano no kami [信濃守]) and Izumo (Izumo no kami [出雲守]) Provinces, and he held the junior grade of the Fourth Rank -- though these posts and honors were still in the future at the time of this chakai.

Despite the family's closeness to Hideyoshi, the Horio joined with Tokugawa Ieyasu's forces as war between he and Ishida Mitsunari approached. At the battle of Sekigahara, Tadauji took his father's place‡ in the Eastern Army, and distinguished himself greatly, receiving praise and an increase in his fief from Ieyasu; but his life was cut short several years later, when he died of an unspecified disease**.

▵ Ki-sai [歸齋]: this person has not been identified, but, from the context, it would appear that he was Misuke's guardian and attendant††. ___________ *This is the name of someone who has retired and taken provisional Buddhist orders.

†His actual yōmei seems to have been Misuke [彌助] (the second kanji is different). However, these kanji (“介” and “助”) seem to be used almost interchangeably when forming part of a given name.

Misuke was a boy at the time of this chakai, just shy of 13 years of age (there seems to be no record of his date of birth) at the time of this gathering (though by the Oriental way of thinking, he would have “turned” thirteen nine days before, on New Year's Day -- which is why most people of that period were generally unconcerned about the actual day on which someone was born).

‡Yoshiharu had been wounded in one of the preliminary skirmishes and was unable to participate in the battle.

**In the summer of 1604 he was on a visit to the Kamosu Jinja [神魂神社] (a major Shintō Shrine in Matsue, that is also known as the Ōba-ōmiya [大庭大宮]), and went to visit the famous Ayame-ike [小成池] -- despite a warning from the head priest of the shrine that the area was off limits. Tadauji returned from the excursion notably ill, took to his bed, and finally died.

††The name suggests that this was an older man (of the samurai caste) who had retired from active life, just the sort of individual who would be charged with closely attending such an important child. (The heir, Horio Kanesuke [堀尾金助; 1573 ~ 1590], had been killed during the battle of Odawara, and Yoshiharu had decided to name this child has his new heir. Perhaps the presentation of Misuke to Hideyoshi, Yoshiharu’s feudal lord, was intended to formalize this intention.)

³Nijō shiki [二疊敷].

⁴Chanoyu dō-zen [茶湯同前].

As usual, when statements of this kind were interpolated by the editors of the Rikyū Chanoyu Sho, they are rarely true.

The tori-awase actually contains several significant changes, which resulted in a very different visual effect from what Rikyū realized in the previous chakai:

▵ arare-kama [霰釜]

▵ Seto mizusashi [瀬戸水指]

▵ chaire ・ ōnatsume [茶入 ・ 大ナツメ]

This would have been Rikyū's large maki-e natsume, since there is nothing to indicate that he was serving these guests gift-tea (which would have been contained in a plain black-lacquered natsume).

He would have used an ori-tame [折撓] -- with a noticeable bend in the handle, as the chashaku.

▵ kuro-chawan [くろ茶碗]

Again, this was the chawan now known as Seitaka-zutsu [勢高筒], that had been delivered to Rikyū by Raku Chōjirō at the very end of the previous year.

With respect to the utensils used to serve tea, Rikyū would have also needed a futaoki and a koboshi, with a take-wa [竹輪] and mentsū [面桶] being most likely:

▵ Bizen tsubo [びぜんつぼ]

In addition to which the Hisada family’s version of this kaiki adds:

▵ Ko-Bizen tsutsu-hanaire [古備前筒花入]*

__________ *This was actually an old Korean hanaire, now known as the Kōrai-zutsu [高麗筒]. As a kake-hanaire, it would have been suspended either on the back wall of the toko, or possibly on the minor pillar that was part of the outside wall. If the chabana was displayed at the same time as the cha-tsubo, hanging the hanaire on the minor pillar, as shown below, would probably have been the preferred place.

The “flower,” though unmentioned, was probably one (or more) budding branch(es) of the weeping willow (such branches are called me-bari yanagi [目張り柳木] in Japanese, and they are used whether the branches have only leaf buds, or actual flower buds). This was Rikyū’s preferred “flower” for use at the beginning of the year.

Rikyū seems to have kept the same branch (or branches), reusing the same arrangement again and again throughout the New Year’s season, appreciating how the buds swelled more and more at each gathering -- since the purpose of the chabana at a wabi gathering is to remind the host and guests of the impermanent and mutable nature of this world’s phenomena.

⁵Kushi-awabi, shiru ・ miso-yaki, meshi [くしあはひ、 汁 ・ みそやき、 めし].

According to the manuscripts, all of dishes mentioned in the Rikyū Chanoyu Sho were actually served to the guests on their zen, arranged as shown below.

The things served on the zen, then, consisted of:

- kushi-awabi [串鮑]: sliced dried abalone (that had been rehydrated by boiling in broth);

- konowata [海鼠腸]: the salted gonads (and their contents) of the sea-cucumber;

- ko-tori senba-iri [小鳥船場煎り]: small birds (usually assorted sparrows and finches, provided to Rikyū by Hideyoshi's hawkers) that were roasted on spits over a wooden fire (while being basted with a sauce consisting of soy sauce, mirin, sake, sesame oil, and crushed garlic);

- miso-yaki jiru [味噌焼汁]: miso-shiru containing julienned daikon and a single large piece of toasted momen-tōfu [木綿豆腐];

- meshi [飯]: steamed rice (measured into uniform portions in a mossō [物相]).

⁶Hikite ・ konowata, ko-tori senba-iri [引テ ・ このわた、 小鳥せんばいり].

There were no hiki-mono served during this gathering*, according to the manuscripts. The konowata and senba-iri were included on the guests’ zen. __________ *Which means that Rikyū did not invite his guests to indulge in the drinking of sake [酒].

Sake was probably served (while the guests ate the kushi-awabi, konowata, and senba-iri dishes), but was probably limited to just one or two drinks.

The service of a hiki-mono was intended to allow the guests to indulge more heavily, and its absence at this chakai was probably deliberate, because the shōkyaku was still a boy.

⁷Kashi ・ fu-no-yaki, kuri [菓子 ・ ふのやき、 くり].

Rikyū's rather usual kashi:

- fu-no-yaki [麩の焼], crêpes filled with sweetened bean-paste; and,

- yaki-guri [焼栗], roasted chestnuts.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rikyū Chanoyu Sho, Book 6 (Part 59): Rikyū’s Hyaku-kai Ki, (1591) Twelfth Month, Twenty-sixth Day; Morning.

59) The same, Morning of the Twenty-sixth Day [同廿六日之朝]¹.

○ [Guests: .]²

○ 4.5-mat [room]³.

○ Chaire: Shiri-bukura [茶入 ・ 尻ぶくら]⁴; ◦ kiri-no-kama [きりのかま]⁵; ◦ [Shigaraki mizusashi [しがらき水指]⁶;] ◦ [Ko-mamori no chawan [木守の茶碗]⁷;] ◦ [Bizen tsubo [びぜんつぼ]⁸;] ◦ [Yoku-ryō-an bokuseki [欲了庵墨跡]⁹.]

○ Abu-mono (tai) [炙物 ・ たい], konowata [このわた], soup (gan [がん]), rice¹⁰.

○ [Hikite [引て]: ◦ [sasai [さゝひ].]¹¹

○ Kashi: fu-no-yaki [ふのやき], kuri [くり]¹².

_________________________

◎ This gathering was given for two of Hideyoshi's retainers, and the use of the kiri-kama suggests that it was held to entertain them while they waited to be summoned into Hideyoshi's presence.

The shōkyaku (Ōtani Yoshitsugu [大谷吉繼]) would soon be appointed one of Hideyoshi's administrators on the Korean peninsula during the upcoming invasion, while the other guest (Teranishi Masakatsu [寺西正勝], who was also one of Rikyū's students), would later be charged with guarding the tea complex in Hideyoshi's Fushimi palace.

These men were probably at Juraku-tei to offer their year-end greetings to Hideyoshi.

¹Onaji nijū-roku nichi no asa [同廿六日之朝].

It is still the Twelfth Month.

According to the manuscript versions of the Rikyū Hyakkai Ki, a gathering was hosted by Rikyū at midday on the 24th. That gathering is missing from the Rikyū Chanoyu Sho.

²No guests are mentioned in the Rikyū Chanoyu Sho.

In the manuscripts, however, this gathering was given for two of Hideyoshi's courtiers:

◦ Ō gyōbushō dono [大刑部少殿]: this refers to daimyō and nobleman Ōtani Yoshitsugu [大谷吉繼; 1558 ~ 1600], who served as gyōbu-shōyu [刑部少輔] (Assistant-vice-minister in the Ministry of Justice, which admitted Yoshitsugu to the junior grade of the Fifth Rank). He seems to have joined Hideyoshi during the early 1570s as a samurai of low rank, and rose to prominence during Hideyoshi's campaigns to subdue Kyūshū (1586 ~ 87), and also participated in the invasion of the continent, where he acted as one of Hideyoshi's administrators in Korea during the invasion, at which time he seems to have become close to Ishida Mitsunari (another of Hideyoshi's bureaucrats on the continent). As a result, he sided with Mitsunari at the battle of Sekigahara (though he seems to have tried to persuade Mitsunari to give up on what he had concluded was a futile effort), and so lost his life.

Yoshitsugu was also said to be afflicted with leprosy.

◦ Teranishi Chikugo dono [寺西筑後殿]*: this refers to Teranishi Masakatsu [寺西正勝; ? ~ 1600], another retainer of Toyotomi Hideyoshi, who was Governor of Chikugo (Chikugo-no-kami [筑後守]) in Kyūshū.

Masakatsu was also a student of Rikyū, and in 1596† he was charged with guarding‡ Hideyoshi's teahouse at Mukaijima, in the Fushimi section of Kyōto. __________ *The Hisada manuscript reads Teranishi Chikuzen dono [寺西筑前殿], which is a mistake since Masakatsu was Governor of the Province of Chikugo, not Chikuzen.

†Keichō gannen [慶長元年], the first year of the Keichō era, which equates to the Gregorian year 1596.

‡Rusui [留守居], which means something like a “house-sitter.” He was charged with guarding the teahouse (and its store house). The rusui took up residence on the grounds to make sure that nobody entered or caused any mischief while the compound was not being used by Hideyoshi.

Because this compound contained many objects peculiar to chanoyu, the person who supervised it had to be thoroughly experienced in chanoyu, to insure their proper preservation.

³Yojō-han [四疊半].

⁴Chaire ・ Shiri-bukura [茶入 ・ 尻ぶくら].

Though not specifically mentioned in any of the versions of this kaiki, Rikyū would have used an ori-tame [折撓] made to match this bon-chaire:

⁵Kiri-no-kama [きりのかま].

This small kama* was always suspended from the ceiling on a bamboo ji-zai [自在], using a bronze tsuru [弦] and kan [鐶]:

None of the other utensils are mentioned in the version of the kaiki that was published in the Rikyū Chanoyu Sho. They are added below from the manuscripts. ___________ *This kama was one of the original kama that Jōō used when he first began to incorporate the irori into his tearooms (the gotoku was not yet being used as a way to support the kama, so the only way that the ro could be used for chanoyu was if the kama was suspended from the ceiling: therefore, the first generation of “ro-gama” were always these small kama -- since Jōō was worried that a larger, heavier, kama would make the guests feel uncomfortable for fear that it might break the ceiling and fall down). Consequently, its use gave anyone aware of this fact a feeling of nostalgia.

⁶Shigaraki mizusashi [しがらき水指].

⁷Ko-mamori no chawan [木守の茶碗].

While nothing is said, Rikyū would also have needed a futaoki and mizu-koboshi, with a take-wa [竹輪] and mentsū [面桶] being most likely.

⁸Bizen tsubo [びぜんつぼ].

⁹Yoku-ryō-an bokuseki [欲了庵墨跡].

¹⁰Abu-mono* ・ tai, konowata, shiru ・ gan, meshi [炙物 ・ たい、 このわた 、汁 ・ がん、 めし].

The four dishes offered to the guests on their zen:

- charcoal-grilled tai [鯛] (sea bream);

- konowata [海鼠腸]: the salted entrails (gonads) of the sea-cucumber;

- gan jiru [雁汁] is a clear soup made by boiling the flesh and bones of a wild goose (which would have been provided to Rikyū by Hideyoshi’s hawkers)†;

- meshi [飯], steamed rice. ___________ *The expression abu-mono [炙物] is found only in the Rikyū Chanoyu Sho. Furthermore, since it is not present in the manuscript versions of the Rikyū Hyakkai Ki, where the dish is referred to (as always) as the yaki-mono [焼物], it seems appropriate to assume that this word was inserted by the editors of the Rikyū Chanoyu Sho -- though their reasons for doing so are mystifying.

Abu [炙] means to roast, to toast (as in bread or mochi), to broil, to grill, and so on.

†In addition to goose (some of the flesh would have been mashed and formed into dango [團子] -- meatballs -- which would be served to the guests in the soup), gan jiru usually includes daikon and leeks (ao-negi [青葱]), as well as seasonal things like mushrooms and wild herbs.

¹¹Hikite ・ sasai [引て ・ さゝひ].

The hiki-mono is not mentioned in the Rikyū Chanoyu Sho, suggesting that the manuscript was damaged*.

According to the manuscripts, it was sazae [榮螺]†, a kind of sea snail.

Sazae can be eaten raw, but they are frequently cooked. One of the easiest ways of doing so is to simply place them on top of burning charcoal (with the opening facing upward), so that the snail is cooked in the seawater present within the shell. This is referred to as tsubo-yaki [壷焼], and it is shown above. __________ *For whatever reason, the editors of the Rikyū Chanoyu Sho were more assiduous about reporting the dishes served in Rikyū's kaiseki than they were about any of the other details of his gatherings.

†Students of chanoyu may recognize the word sazae as the name of one of the futaoki no shichi shu [蓋置の七種], the seven special futaoki each of which is handled in a special way. The original sazae no futaoki [榮螺の蓋置] was an actual sazae shell -- albeit one that, when turned so that the opening was uppermost, had a rim that was perfectly level (while most are oriented at an angle). The original is said to have first used as an incense burner, so it was polished and lacquered (some accounts say, with gold or nashi-ji [梨地] -- a “textured” lacquer where small flakes of gold, rather than gold powder, are dusted over a gold-colored lacquered surface).

The futaoki no shichi shu are: 1) hoya [ホヤ, 骨家, 火屋], 2) kakure-ka [隠れ家] or go-toku [火卓, 五徳], 3) mikkan-jin [三閑人] (also known as mitsu ningyō [三人形]), 4) ikkan-jin [一閑人], 5) mitsu-ba [三つ葉], 6) kani [蟹], and 7) sazae [榮螺]. (Several of them have more than one name because they have been used since the early fourteenth century, if not before, while the names became standardized only in the Edo period. Originally, as with all tea things, there was only one -- or at most a few -- prototype; they began to be manufactured and sold in sets only in the Edo period, when the teaching and public performance of chanoyu became a big business, at which time all things were standardized.)

¹²Kashi ・ fu-no-yaki, kuri [菓子 ・ ふのやき、 くり].

And Rikyū’s usual kashi: fu-no-yaki [麩の焼] (sweet red-bean-paste filled crepes), and yaki-guri [焼栗] (roasted chestnuts).

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rikyū Chanoyu Sho, Book 6 (Part 54): Rikyū’s Hyaku-kai Ki, (1591) Twelfth Month, Nineteenth Day; Morning.

54) The same, Nineteenth Day [同十九日]¹.

○ Guests: Ishida moku-no-kami [石田木工頭]², Kinoshita Hansuke [木下半助]³.

○ 4.5-mat [room]⁴.

○ Chaire: Konoha-zaru [茶入 ・ 木葉猿]⁵; ◦ usucha: ō-natsume [薄茶 ・ 大棗]⁶; ◦ [shi-hō-gama [四方釜]⁷;] ◦ [Soto-no-hama chawan [外ノ濱茶碗]⁸;] ◦ [Shigaraki mizusashi [しがらき水指]⁹;] ◦ [Bizen tsubo [びぜんつぼ]¹⁰;] ◦ [Yoku-ryō-an bokuseki [欲了庵墨跡]¹¹.]

○ Ko-tori senba [小鳥 ・ せんば], konowata [このわた], soup (miso-yaki [みそやき]), rice¹².

○ Hiki soshite [引 而]: ◦ sake (yaki-mono) [鮭 ・ ヤキ物]¹³.

○ Kashi: fu-no-yaki [ふのやき], shiitake [しいたけ]¹⁴.

_________________________

◎ This was a gathering held for two of Hideyoshi's retainers, both of whom held positions within the Imperial Palace. Both men were loyal supporters of the Toyotomi family, and held responsible positions in the government as well. And while they were probably at Juraku-tei to make their respective reports to Hideyoshi (at the end of the year, officials were called upon to present their accounts for the past year), this gathering probably was also framed as a bōnen-no-chakai [忘年の茶會] (a gathering for “forgetting the old year”).

¹Onaji jū-ku nichi [同十九日].

Onaji [同] refers to the month: it is still the Twelfth Month.

In the Rikyū Chanoyu Sho, the time of day for this chakai is not noted; however, in the manuscript versions this gathering is marked as morning (asa [朝]).

²Ishida moku-no-kami [石田木工頭].

This refers to Ishida Masazumi [石田正澄; 1556 ~ 1600], the elder brother of Ishida Mitsunari [石田三成; 1559 ~ 1600], a daimyō and court noble. He, like his brother, was a vassal of Toyotomi Hideyoshi.

He served in the Department of Carpentry (moku-ryō [木工寮]), and served as moku-no-kami [木工頭] (the head of the Palace Department of Carpentry -- a bureaucratic position primarily concerned with expenses, finance and accounting being skills common to both of the Ishida brothers, which contributed to their rise to positions of power and trust within Hideyoshi’s government), in connection with which he held the junior grade of the Fifth Rank.

³Kinoshita Hansuke [木下半助].

The name is given as Kinoshita Hansuke [木下半介] in the Sadō Ko-ten Zen-shu [茶道古典全集]. This refers to the man known as Kinoshita Yoshitaka [木下吉隆; ? ~ 1598]. He was a daimyō-nobleman and retainer of Toyotomi Hideyoshi, who also served in the Daizen-shiki [大膳職] (also pronounced Ōkashiwade-no-tsukasa; this was the department that arranged the Emperor's meals: Yoshitaka was the daizen-daibu [大膳大夫], the head of this department, and so occupied a position of great trust within the Imperial Household).

Yoshitaka held the junior grade of the Fifth Rank.

⁴Yojō-han [四疊半].

⁵Chaire ・ Konoha-zaru [茶入 ・ 木葉猿].

Rikyu would have used an ori-tame [折撓], a bamboo chashaku (with a node in the middle, where the handle was bent slightly), that he had made himself to be used with this chaire.

⁶Usucha ・ ō-natsume [薄茶 ・ 大棗].

The fact that a different variety of tea was used for usucha suggests that it had been brought to Rikyū as a gift*, probably by one of the guests.

Aside from the chaire and the ō-natsume, none of the other utensils are mentioned in the account of this gathering that was published in the Rikyū Chanoyu Sho. __________ *Both men worked in the Imperial Palace, and the tea had likely come from there.

⁷Shi-hō-gama [四方釜].

⁸Soto-no-hama chawan [外ノ濱茶碗].

This is the ido-chawan [井戸 茶碗] that is named the Soto-ga-hama ido [外ヵ濱 井戸].

Both koicha and usucha would have been served in this same chawan.

⁹Shigaraki mizusashi [しがらき水指].

In addition to which Rikyū would have used a take-wa [竹輪] and mentsū [面桶].

¹⁰Bizen tsubo [びぜんつぼ].

¹¹Yoku-ryō-an bokuseki [欲了庵墨跡].

¹²Ko-tori ・ senba[iri], konowata, shiru ・ miso-yaki, meshi [小鳥 ・ せんば、 このわた、 汁 ・ みそやき、 めし].

These were the four dishes offered to the guests on their zen:

- ko-tori no senba-iri [小鳥船場煎り]: small birds (finches and sparrows, provided to Rikyū by Hideyoshi's hawkers) roasted on spits over a wood fire, that were glazed with a mixture of soy sauce, sesame oil, sake and/or mirin, and crushed garlic -- it was a style of cooking that hailed from Sakai;

- konowata [海鼠腸] is the salted gonads (and their contents*) of the sea-cucumber, which were considered a great delicacy;

- miso-yaki jiru [味噌焼汁] is miso-shiru containing julienned daikon and a piece of yaki-tōfu [焼豆腐]†; and,

- meshi [飯], steamed rice. __________ *Both the eggs and the milt have a creamy consistency, while the gonadal ducts are stringy and give the konowata some substance (allowing it to be picked up with chopsticks).

†Yaki-tōfu [焼豆腐] is momen-tōfu [木綿豆腐] (“hard” tōfu) that has been skewered and grilled over charcoal. Usually the block is cut in half lengthwise, and the two parts are then quartered. One of these pieces is put into the soup bowl (with the browned side facing upward).

¹³Sake (yaki-mono) [鮭 ・ ヤキ物].

Charcoal grilled salmon (sake [鮭]) was brought out later, as the hiki-mono.

Served from a bowl, along with several drinks of sake [酒], this allowed each guest to eat more than one piece of the salmon, if he so desired.

¹⁴Kashi ・ fu-no-yaki, shiitake [菓子 ・ ふのやき、 しいたけ].

Fu-no-yaki [麩の焼] is Rikyū's signature sweet -- wheat-flour crêpes filled with sweet red-bean-paste.

Shiitake [椎茸] are a kind of mushroom that is naturally available from autumn until early spring; they are cultivated on the logs of a kind of oak (shiidake [椎茸] means “oak mushroom”), usually referred to as the Japanese Chinquapin (Castanopsis cuspidata). The shiitake would have been grilled over charcoal and lightly salted before serving as kashi.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rikyū Chanoyu Sho, Book 6 (Part 58): Rikyū’s Hyaku-kai Ki, (1591) Twelfth Month, Twenty-fourth Day; Morning.

58) Morning of the Twenty-fourth Day [廿四日之朝]¹.

○ Guests: Kimura Hitachi-no-suke [木村常陸介]², Tōgorō dono [藤五郎殿]³, Chūzaburō dono [忠三郎殿]⁴.

○ 4.5-mat [room]⁵.

○ Katatsuki [肩衝] (on a square tray [四方盆ニ]); however no tea was put into it⁶.

◦ Tea was put into the katatsuki [肩撞] (?) and the ko-natsume [小棗]⁷.

○ The food served on the zen was [the same] as [mentioned] on the right⁸.

_________________________

◎ This was a gathering that Rikyū hosted for three of Hideyoshi's generals, who had probably come to Juraku-tei to report to Hideyoshi on the preparations for the upcoming invasion of the continent, as well as to offer him their greetings at the end of the year. As such, this chakai was part of their official reception, and Rikyū treats these guests with appropriate deference by performing the bon-date temae [盆立手前].

With respect to the details of the utensils and the meal, the kaiki, as printed in the Rikyū Chanoyu Sho, is nonsensical (apparently several fragments from a different kaiki migrated into the records of this gathering). The correct information has been supplied from the manuscripts, which describe this gathering clearly, as usual.

¹Nijū-yokka no asa [廿四日之朝].

It is still the Twelfth Lunar Month.

²Kimura Hitachi-no-suke [木村常陸介].

This refers to Kimura Shigekore [木村重茲; ? ~ 1595), who held the post of Hitachi-no-suke [常陸介]*. He was also protector of Toyotomi Hidetsugu (whom Hideyoshi adopted as his heir apparent after the death of his first son Tsuru-matsu [鶴松] in the early autumn of 1591).

Shigekore shared in the unfortunate fate of Hidetsugu, when he was eliminated (after being charged with, perhaps fictitious, treason), following the birth of a new son, Hideyori.

One of Rikyū's densho was addressed to Kimura Hitachi-no-suke Shigekore, though the contents suggest that Shigekore's interest in chanoyu was more a result of it being the fashion of the day among Hideyoshi's courtiers, than because he espoused a sincere desire to master the details of the practice†. __________ *Hitachi-no-suke [常陸介] is usually translated Deputy Governor of Hitachi Province, in eastern Honshu. The governor of Hitachi was traditionally an Imperial Prince (his governorship was a sinecure, while the Deputy Governor was actually in charge of the province).