#kokand autonomy

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The Kokand Autonomy

When we last left the Jadids in Tashkent, the Russian Settlers had created the Tashkent Soviet, which was a governmental body for Russians only. The Jadids and their fellow modernizers held a congress of Muslims in Kokand in response and created the Kokand Autonomy. This was an eight-man governmental body that answered to a 54-member council, with about 1/3 of those seats reserved for Russian settlers. Muhammedjan Tinishbayev was elected prime minister and minister of internal affairs, Mustafa Cho’qoy was named minister of external affairs, Ubaydulla Xo’jayev oversaw creating a people’s militia, and Obidjon Mahmudov became minister of food supply. 1917 ended with the Kokand Autonomy discovering discussing what an ideal government should be was easier than actually governing a territory in the midst of a civil war and famine. Meanwhile the Tashkent Soviet viewed an autonomous Turkestan as an existential threat.

It is now 1918 and the Kokand Autonomy is fighting for its life.

How (Not) to Govern

The Kokand Autonomy has been created, but now Tinishbayev and his ministers have to figure out what to do with this newly created governmental body. They faced three big problems: lack of funds and raging famine, lack of arms and an aggressive neighbor, and overall lack of governmental experience amongst its members.

Finances

As we’ve talked about in our other episodes, famine hit Turkestan hard starting in 1917, increasing ethnic clashes, creating groups of bandits who would later become the Basmachi in the rural areas, and providing the Russian Settlers the excuse they needed to settle old scores with their indigenous neighbors and forcefully establish themselves as agents of order and security. The Kokand ministers were aware of all of these issues, but also understood that they would not be able to government effectively without money first and foremost. However, they were unable to levy taxes and had no other sources of funding.

Since all of the cabinet ministers were inexperienced scholars, merchants, and members of the religious class with no governing experience, they relied on what they knew: talking to the people through various publications and venues and organizing mass demonstrations.

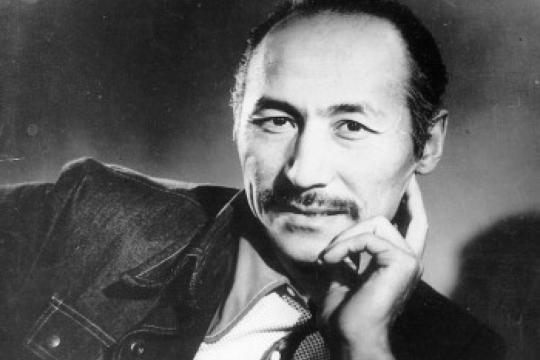

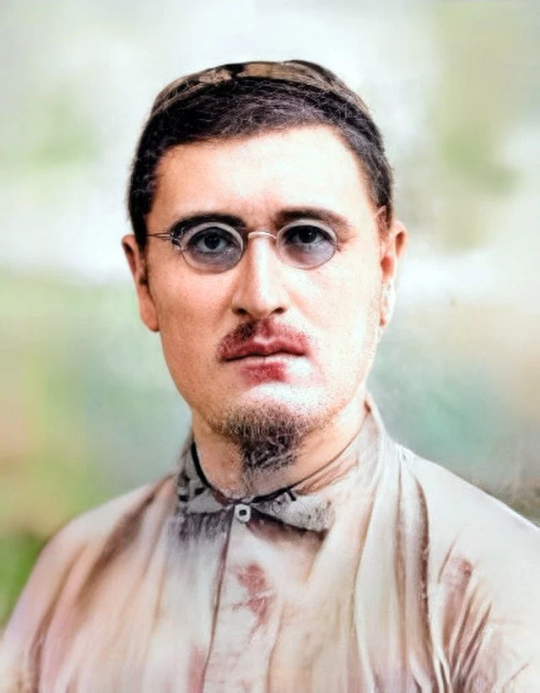

Mustafa Choqoy

[Image Description: A black and white photo of a man with soft, black hair and a long mustache. He has round cheeks. He is wearing a high collared shirt with three gold buttons holding the collar closed. A white collar peeks out over the collar.]

Their first demonstrations occurred in Andijan on December 3rd and Tashkent itself on December 6th. A second demonstration occurred in Tashkent a week later, and, this time, the demonstrators targeted the local prison that held political enemies arrested by the Tashkent Soviet when they first took power in November. Russian soldiers were called to suppress the demonstration which they did by firing into the crowd, killing several demonstrators, while others were crushed to death during the stampede that followed. The freed prisoners were eventually recaptured and executed by the Tashkent Soviet.

However, the Kokand Autonomy got this idea that public support could be turned into financial support, if approached the right way. To achieve this end, many members of the Kokand government traveled throughout Turkestan, holding fundraisers. For example, on January 14th, Choqoy and Mirjalilov held a fundraiser in Andijan and raised 17,200 rubles. However, their most successful financial scheme was a public loan which raised 3 million rubles by the end of February 1918. Yet, the Kokand Autonomy was still unable to levy taxes on its population, meaning it didn’t have a sustainable method of extracting wealth.

If we think back about our discussion on the IRA, we’ll remember that Michael Collins’ greatest contribution was actually in the financial realm. Without his national loan scheme, the IRA would not have survived or been as successful as it was. The money allowed the IRA to buy arms and create an alternative shadow government that opposed “established” British rule. This is the same exact situation the Kokand Autonomy was facing, but not only was it finding it hard to consistently raise funds and manage widespread famine and ethnic violence, it also didn’t have an IRA equivalent to protect it or enforce its edicts.

This brings us to the second biggest problem facing the Kokand Autonomy: the lack of arms.

Military Capabilities

In 1918, the Russian Settlers had most of the guns and were supported by the Russian soldiers and many POWs stationed in Turkestan. The Kokand Autonomy didn’t have many weapons nor did they have an army they could pull from for defense. Because Russia never conscripted its Turkestan population, the only potentially friendly troops with experience available to the Kokand government were the Tatar and Bashkir troops stationed in the region. But they weren’t enough to constitute an army and there were tensions amongst the Tatars, Bashkirs, and other peoples who made up Central Asia. Instead, the Kokand Autonomy had to rely on volunteers to form the bulk of their army. Similarly, to the region wide fundraisers, members of the Kokand government would travel throughout Turkestan to recruit soldiers. They were never able to create an army but seemed to attract enough volunteers to hold a parade in the old city of Kokand on January 9th, 1918.

Once they had enough men to constitute a “army” they needed to find a commander. To that end, they offered command to Irgush. We talked about Irgush in our episode on the Basmachi, but he had been a cop before becoming Kokand’s commander-in-chief. What he inherited was a collection of unarmed men who had no officers to train them and no military experience. Meanwhile, the Tashkent Soviet was preparing to launch an attack on Kokand to crush the Kokand government.

Tashkent Soviet

The Tashkent Soviet was threatened by having an autonomous, Muslim government next door. Their anxiety was increased by the December demonstrations and news that the Kokand government was organizing an army (never mind that the violent actions of the Soviet itself justified Kokand’s need for an army).

We must remember this was happening within the context of WWI and by 1918, the Russian war front in the Caucasus had collapsed, opening a path for the Ottoman army. While the Jadids would always flirt with a deep love for the Ottomans, and even sent one of their ministers Mahmudov to Baku to negotiate with the Ottoman forces for grain, there is no evidence they ever made concrete plans for the Ottoman Empire to invade Central Asia and support their cause. The connection Mahmudov made with the Ottoman officer Ruseni Bey is an interesting movement of what-ifism, but never led to any solid plans. Instead, Ruseni Bey would travel to Kokand but arrive too late to be of any use. He would later organize a branch of the CUP in Tashkent and former members of the Kokand Autonomy would travel back and forth from Central Asia to Istanbul in 1918 and 1919, but again these efforts came to almost nothing, except to haunt the Bolsheviks.

The second biggest driver for the Tashkent Soviet was the lack of food. As we’ve seen in our other episodes, food and resources had always been a painful point of contention for the Russian Settlers and the indigenous population. WWI made things worse with Russians attacking Muslim merchants for hoarding food and settlers getting into violent quarrels with the nomads of the steppe over food and land. As famine swept through Turkestan, the Russian Settler’s belief that the Muslims of Turkestan were hoarding mountains of food grew. When the Russians heard of the Kokand Autonomy, they were convinced that the government owned huge stocks of grain that they refused to share with the similarly starving Russians. This, in itself, was justification enough for a violent confrontation. They began recruiting in December of 1917, targeting former soldiers and POWs. On February 14th, 1918, they launched their assault.

It began with cannon fire joined in by indiscriminate machine fire, killing thousands and setting most of old Kokand on fire. The soldiers, once the meager defense fell apart, swarmed the city and began looting. According to one eyewitness account:

“All the stores, trading firms, and rows of stalls in the old city were looted, as well as all banks, and all private, more or less decent apartments. Safes…were broken open and emptied. The thieves gathered their plundered goods on carts and drove them to the railway and the fortress.” - Jeff Sahadeo, Russian Colonial Society in Tashkent, 1865-1923, pg. 202

The assault killed an estimated 14,000 people, most of whom were Muslim, and overthrew the Kokand government 78 days after its creation.

The Russians, however, proved to themselves that they could organize a full-scale military operation and would use these skills to continue their requisitions of indigenous property and food, using communist rhetoric to justify their actions. In doing so, they created a new problem for themselves: starving indigenous refugees fleeing from all over the region into Tashkent looking for food while the Soviet’s own armed soldiers turned into nothing short of armed thugs, using force to take the best of whatever food was around for themselves.

Without any indigenous body of government to speak up for them, the Muslims of Turkestan were at the mercy of their Russian neighbors and Basmachi warlords while their Russian neighbors were at the mercy of their only militant monster they created to survive.

Kokand Legacy

Despite being a failed attempt at autonomous government, the Kokand Autonomy mentally scarred the Russian settlers and the Bolsheviks. For decades after the Soviet Union established control over Central Asia, association with the Kokand Autonomy would be an eventual death sentence. The Soviets would associate the alternate government with bourgeois nationalism and Pan-Turkic aspirations which of course threatened the Soviet’s version of imperial communism. It also left their Central Asian borders open to outside interference whether from the Ottoman Empire or, much later, Afghanistan and the British.

When it comes to the Ottoman Empire, there is some evidence that the high command considered annexing Turkestan, but these were pipe dreams at the most. The closest the Ottomans came to threatening Russian rule in the Caucasus and Central Asia was taking Baku in 1918, but their lack of resources and four years of ruthless modern warfare prevented any further expansion. Even the fears about British or Afghani intervention (which we’ll discuss later in the season) were half-baked and revealed more about Russian fears than reality on the ground. Just as the British feared the Russian bogeyman during the Great Game, the Soviets went through a similar period of insecurity in Central Asia between 1918 and 1930.

The Kokand Autonomy’s gravest sin, in Soviet eyes, was that it was an alternate form of government that maybe could have worked if it hadn’t been smothered during its infancy. While the members of the Kokand government were inexperienced, they were desperately trying to build governmental infrastructure through their fundraisers and army recruitment while also trying to win international recognition. Members of the government such a Behbudiy tried to bring their case to the Paris Peace Conference. Behbudiy was arrested by the Bukharan Emir and tortured to death before he could make it to Paris, but Mustafa Cho’qoy tried again after the fall of Kokand. Long story short, Mustafa fled Tashkent in 1918 and found his way to Ashgabat, where the Russian Mensheviks had just overthrown Soviet power and established its own autonomous government. Cho’qoy along with Vadim Chaikin, a Socialist Revolutionary Lawyer, send a telegram to Woodrow Wilson and the Paris Peace Conference, asking for the recognition of the territorial unity of Turkestan and its right to “free and autonomous existence in fraternal friendship with the people of Russia” (Khalid, pg. 82).

The peace conference ignored the telegram, but the Bolsheviks believed it was proof that Cho’qoy and the Kokand Autonomy were going to sell Turkestan out to imperialists. Even though the telegram went nowhere, it frightened the Bolsheviks, believing that “imperialists” would use it as an excuse to stamp out communism within Central Asia. Cho’qoy who would eventually resettle in Paris became the devil incarnate for the Bolsheviks and any association with him-past and present- proved fatal to many of Cho’qoy’s associates. In the end, the Kokand Autonomy was a non-Bolshevik approved form of government that risked being a rallying cry for the Soviet’s enemies and thus it had to be destroyed and anyone associated with it had to be monitored and eventually destroyed as well.

The Kokand Autonomy’s final legacy is in what was created out of its fall. Men such as Irgush would flee to the rural areas of Turkestan and create the first true instance of what would known as the Basmachi. We talked about it briefly in our episode on the Basmachi, but after Kokand fell Irgush went to the Ferghana and by the end of 1918 had organized 4,000 fighters under his command. He would later ally with another Basmachi commander, Madamin Bey and hinder Bolshevik efforts to establish control form 1919 onward. Others, like Fitrat, Xo’jayev, and Tinishbayev fled to “safe” spaces within Turkestan and crafted new ways to protect the Muslims of Turkestan while achieving the Muslim led government they desired. Famine grew worse as the Tashkent Soviet violently requisitioned food and property from their Muslim neighbors and Turkestan saw a massive population decrease as people died or fled to neighboring regions. And the Bolsheviks and Mensheviks were still raging their war in the north, threatening Kazakh and Kyrgyz lands.

Turkestan was currently in its own little bubble of ethnic conflict and starvation, but the fall of Kokand created the circumstances that would enable Muslim reformists to find common cause with the approaching Bolsheviks while providing the fuel the Basmachi would need for a prolonged guerrilla campaign.

#central asian history#central asia#kokand autonomy#mustafa choqoy#turkestan#histori#queer historian#history blog#Spotify

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Discovering the world

Kyrgyzstan 🇰🇬

Basic facts

Official name: Кыргыз Республикасы (Kyrgyz Respublikasy)/Кыргызская Республика (Kyrgyzskaya Respublika) (Kyrgyz/Russian) (Kyrgyz Republic)

Capital city: Bishkek

Population: 6.7 million (2023)

Demonym: Kyrgyzstani

Type of government: unitary presidential republic

Head of state and government: Sadyr Japarov (President)

Gross domestic product (purchasing power parity): $48.05 billion (2024)

Gini coefficient of wealth inequality: 29% (low) (2020)

Human Development Index: 0.701 (high) (2022)

Currency: som (KGS)

Fun fact: It is home to the world’s largest walnut forest.

Etymology

The country’s name consists of the Turkic word for “we are forty”, which is believed to refer to the forty clans of legendary hero Manas, and the Persian suffix -stan, which means “place of”.

Geography

Kyrgyzstan is located in Central Asia and borders Kazakhstan to the north, China to the east and southeast, Tajikistan to the south, and Uzbekistan to the west.

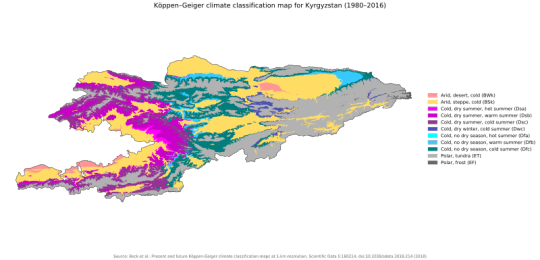

There are six main climates: warm-summer humid continental in the northeast, Mediterranean-influenced warm-summer humid continental in the west, subarctic and tundra in the center, east, and southwest, cold desert in the northwest and southwest, and cold steppe in the rest. Temperatures range from −10 °C (14 °F) in winter to 32 °C (89.6 °F) in summer. The average annual temperature is 9.6 °C (49.2 °F).

The country is divided into seven regions (oblystar/oblasti), which are further divided into 44 districts (aymaqtar/rayony). The largest cities in Kyrgyzstan are Bishkek, Osh, Jalalabad, Karakol, and Tokmok.

History

30-375: Kushan Empire

440s-560: Hephthalite Empire

539-1207: Kyrgyz Khaganate

552-603: First Turkic Khaganate

603-742: Western Turkic Khaganate

682-744: Second Turkic Khaganate

744-840: Uyghur Khaganate

843-1347: Qocho Kingdom

1223-1266: Mongol Empire

1266-1347: Chagatai Khanate

1501-1785: Khanate of Bukhara

1709-1876: Khanate of Kokand

1876-1917: Russian Empire

1917-1918: Turkestan Autonomy

1918-1924: Turkestan Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic

1924-1926: Kara-Kirghiz Autonomous Oblast

1926-1936: Kirghiz Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic

1936-1990: Kirghiz Soviet Socialist Republic

1990-1991: Republic of Kyrgyzstan

1991-present: Kyrgyz Republic

2005: Tulip Revolution

2010: Second Kyrgyz Revolution

2020: Third Kyrgyz Revolution

Economy

Kyrgyzstan mainly imports from China, Russia, and Uzbekistan and exports to the United States, Kazakhstan, and Russia. Its top exports are dry pulses, sheep and goats, and cotton.

It has antimony, coal, gold, and uranium reserves. Services represent 54.2% of the GDP, followed by industry (31.2%) and agriculture (14.6%).

Kyrgyzstan is a member of the Collective Security Treaty Organization, the Commonwealth of Independent States, the Eurasian Economic Union, the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe, the Organization of Islamic Cooperation, the Organization of Turkic States, and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization.

Demographics

77.8% of the population is Kyrgyz, while Uzbeks represent 14.2% and Russians 3.8%. The main religion is Islam, practiced by 91% of the population, the majority of which is Sunni.

It has a positive net migration rate and a fertility rate of 3 children per woman. 38% of the population lives in urban areas. Life expectancy is 71.9 years and the median age is 24 years. The literacy rate is 99.2%.

Languages

The official languages of the country are Kyrgyz and Russian, spoken by 61.1% and 37.3% of the population, respectively.

Culture

Kyrgyzstan is known for its carpets and tapestries and nomadic farming. Bride kidnapping, although illegal, is still practiced.

Men traditionally wear a shirt (keynek), wide, embroidered pants (chalbar), a wide belt (kemer), a felt robe (kementay), and a white felt hat (kalpak). Women wear a white shirt (keynek) and long pants or a dress, an embroidered vest (chyptama), and a white muslin turban (elechek) or a conical hat with a veil (topu).

Architecture

Traditional houses in Kyrgyzstan are conical wooden structures covered in felt and wool.

Cuisine

The Kyrgyzstani diet is based on dairy products, meat, rice, and vegetables. Typical dishes include chiuchiuk (horse sausage), dimlama (a stew of meat, onions, potatoes, and vegetables), langman (a dish of meat, noodles, and vegetables), oromo (a steamed pie with minced meat and onions), and qurut (tangy, dried yogurt balls).

Holidays and festivals

Like other Muslim and Christian countries, Kyrgyzstan celebrates Orthodox Christmas, Eid al-Fitr, and Eid al-Adha. It also commemorates New Year’s Day, International Women’s Day, Persian New Year, and Labor Day.

Specific Kyrgyzstani holidays include Fatherland Defenders’ Day on February 23, Day of National Revolution on April 7, Constitution Day on May 5, Remembrance Day on May 8, Victory Day on May 9, Independence Day on August 31, and Days of History and Commemoration of Ancestors on November 7 and 8.

Independence Day

Other celebrations include the Birds of Prey Festival, the Kyrgyz Kochu Festival, which showcases the art of felt-making, and the National Horse Festival.

Kyrgyz Kochu Festival

Landmarks

There are three UNESCO World Heritage Sites: Silk Roads: the Routes Network of Chang’an-Tianshan Corridor, Sulaiman-Too Sacred Mountain, and Western Tien-Shan.

Sulaiman-Too Sacred Mountain

Other landmarks include the Ala Archa National Park, the Burana Tower, the Holy Trinity Russian Orthodox Cathedral, the Kol-Tor Lake, and the Ruh Ordo Cultural Center.

Ruh Ordo Cultural Center

Famous people

Aisuluu Tynybekova - wrestler

Bübüsara Beyshenalieva - dancer

Chinghiz Aitmatov - writer

Kasym Tynystanov - poet

Mirlan Murzayev - soccer player

Salamat Sadikova - singer

Salizhan Sharipov - astronaut

Samal Yeslyamova - actress

Suimonkul Chokmorov - actor and artist

Valentina Shevchenko - mixed martial artist

Suimonkul Chokmorov

You can find out more about life in Kyrgyzstan in this article and this video.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Episode 35 Turkestan and Bolshevism 1918

For this episode, we’re going to leave the Alash Orda in the Steppe with their Bolshevik and White Movement problem and return to the Jadids in Turkestan. Things were not going well for the Jadids. The Tashkent Soviet strangled the Kokand Government before it could breathe, the Bukharan and Khivan Emirs showed no interest in reform. Famine swept the land and the Basmachi were organizing themselves in the Ferghana. The Jadids themselves were on the run, without any real power, and the Bolsheviks were determined to spread communism into the region.

Enter Pyotr Kobozev

Lenin understood that the first step in regaining control over Turkestan was to settle the dispute between the indigenous peoples and the settlers. While the Bolsheviks negotiated with the Alash Orda in the Kazakh Steppes and the Czech Legion made their way to Vladivostok, the Bolsheviks appointed Pyotr Kobozev as plenipotentiary commissar for Turkestan.

Pyotr Kobozev

[Image Description: A black and white drawing of a man in a military cap with a star and the sickle and hammer. He has a thick, circular beard and mustache. He is looking to the left. He is wearing a white shirt and dark coat.]

Kobozev is an interesting figure of the Russian Civil War. He was born on August 4th, 1878, in the village of Pesochyna, Russia. He was born to a Moscow railroad employee but fell in love with theology and attended the Moscow seminary. He either left (or was expelled for taking part in a student uprising) and attended the Moscow secondary school of Ivan Findler. He frequented Marxist circles and joined the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party in 1898 while attending the Moscow Higher Technical School before being expelled once more for taking part in a student strike. He was exiled to Riga, Latvia. He remained involved with Marxist and Communist circles, making it almost impossible to find work. In 1915 he moved to Orenberg where he worked a railroad engineer and the leader of the city’s Russian Social Democratic Labour Party.

During the February Revolution he organized an agitation train along the Orenburg-Tashkent route, urging for support of the Bolsheviks. He would have been the Commissar of the Tashkent Railroad if the Provisional Government had not blocked his appointment. Instead, he was appointed the chief inspector over the educational institutions of the Ministry of Transport. Then the October Revolution.

Ataman Alexander Dutov took advantage of the revolution to claim power in the Orenburg region, which the Bolsheviks opposed. Kobozev was appointed the extraordinary commissar for the resistance to Dutov’s counterrevolution. He spent the rest of 1917 planning an assault on Dutov’s forces, reclaiming the city in January 1918. It is said he drove one of the armored trains himself.

After he reclaimed Orenburg, Kobozev was sent to Baku to nationalize the local old industry. With 200 million rubles, he was able to prop up the Bolsheviks in Orenburg, Baku, and Tashkent, successfully re-establishing the oil flow to Russia. In early 1918, Lenin sent a telegram to the Tashkent Soviets, announcing the arrival of Kobozev and two members of the People’s Commissariat of Nationalities in Tashkent. One of his travel companions was Arif Klebleyev a former member of the Kokand Autonomy. In fact, he was the one who sent a telegram to the Tashkent Soviet asking they recognize the Kokand Autonomy as a legal authority in Turkestan. Now he was working with the Soviets.

Lenin’s telegram read:

“We are sending to you in Turkestan two comrades, members of the Tatar-Bashkir Committee at the People’s Commissariat for Nationalities Affairs, Ibrahimov and Klebleyev. The latter is maybe already known to you as a former supporter of the autonomous group. His appointment to this new post might startle you; I ask you nevertheless to let him work, forgiving his old sins. All of us her think that now, when Soviet power is getting stronger everywhere in Russia, we shouldn’t fear the shadows of the past of people who only yesterday were getting mixed up with our enemies: if these people are ready to recognize their mistakes, we should not push them away. Furthermore, we advise you to attract to [political] work [even] adherents of Kerensky from the natives if they are ready to serve Soviet power-the latter only gains from it, and there is nothing to be afraid of in the shadows of the past” - Adeeb Khalid, Making Uzbekistan, pg. 94

Kobozev arrived in April 1918 and made the following changes:

First, he forced the inclusion of indigenous peoples in governing bodies, including the Fifth Congress of Soviets that convened in Tashkent on April 21st, 1918.

He also elected himself as chair of the presidium during the Congress.

During the same congress, he created the Central Executive Committee of Turkestan (TurTsIK) as the supreme authority in the region. He ensured that nine of its 36 members were Muslims.

Second, he proclaimed a general amnesty for everyone involved with the Kokand Government.

Third, he created the Communist Party in Turkestan (KPT) in June 1918. By 1920, it would consist of 57 thousand members.

Fourth, He forced a re-election to the Tashkent Soviet, winning a “brilliant victory of ours in the elections to Tashkent’s proletarian parliament has decisively crushed the hydra of reaction…White Muslim turbans have grown noticeably in the ranks of the Tashkent parliament, attaining a third of all seats” - Adeeb Khalid, making Uzbekistan, pg. 94

The Rise of the Jadids

Jadids were not enthused at first. Between the bloodbath that followed the Russian Revolution and the overthrow of the Kokand Autonomy, they had little reason to trust the Bolsheviks. Abdurauf Fitrat would write in 1917:

“Russia has seen disaster upon disaster since the [February] transformation and now a new calamity has raised its head, that of the Bolsheviks!” - Adeeb Khalid, Making Uzbekistan, pg. 95

G’ozi Yunus, another Jadid, would write about the Tashkent Soviet:

“Muslims have not seen a kopek’s worth of good from the Freedom [i.e., the Revolution]. On the contrary, we are experiencing times worse than those of Nicholas” - Adeeb Khalid, Making Uzbekistan, pg. 95

For a moment, they looked to the Ottoman Empire as a source of salvation and G’ozi Yunus even traveled to Istanbul to petition the Ministry of War. When the Ottoman Empire was defeated during the world war (and Russia leaked the secret treaty between Britain and France divvying up Ottoman land amongst themselves), the world lost the last independent Muslim empire and the Jadids were forced to turn internally and to their neighbors for support.

The Jadids used their new political power to, first, punish their old enemies the ulama. They used the KPT in old city Tashkent to take land from the ulama and on May 21st, 1918, the commissar of the old city shut down the Ulamo Jamiyati, their journal al-Izoh and took its property. For the next two years, the Bolsheviks would requisition lands once owned by the ulama on the behalf of the new-method schools started by the Jadids and their theatrical groups, empowering one set of indigenous peoples over another. The Jadids also targeted the ulama’s control over the waqf. A waqf is a religious donation of land or money that can be used to support the community. The ulama controlled what could be donated and how it was distributed amongst the community. The Jadids, by taking control, wanted to use the waqf founds to support causes they thought worthy and would help modernize society.

The ulama for their part either found refugee with the more conservative elements of the society, joined the Basmachi, or attempted to win Bolshevik support by proclaiming that socialism had roots in Islam and they were the truly anti-capitalist sect whereas the Jadids were westernized modernizers who would bring about capitalism to Turkestan.

The Muslims of Turkestan were granted the right to use firearms, and, despite Kobozev’s efforts, the old dynamics returned to the city. The newer settlements remained the stronghold of the Russian settlers while the Muslims’ power was confined to the old city. The Jadids recruited Ottoman POWs to serve as teachers where they created clubs and secret societies. Some of these clubs were nationalistic, others were social gatherings. From 1918-1920, the Ottoman POWs became a core facet of Turkestan society as the indigenous peoples tried to survive the tumultuous end of the decade.

Turar Risqulov

The opening of the political world attracted other activists who did not support the Jadid’s version of reform. The Jadids got their start in political activism via the arts and education. This new cadre of politicians entered politics through the radicalization of the famine and violence against Muslim peasants and nomads and spoke the language of Bolshevism and the revolution. Many of these new politicians were younger than the Jadids and had gone through the Russian-native schools, giving them the benefit of speaking fluent Russian (similar to the members of the Alash Orda). Few had ever taken part in the Islamic reform championed by the Jadids.

Turar Risqulov

[Image Description: A black and white pciture of a man standing at an angle. He is looking at the camera. He has bushy black hair and a short mustache. He is wearing round, wire frame glasses. His hands are in his dark grey suit pants. he is wearing a white button down shirt, a grey tie, and a dark grey vest and suit jacket. A flag is pinned to his suit lapel.]

One of these men, a fascinating person who is my newest obsession was Turar Risqulov (1894-1938) He was born in Semirech’e to a Kazakh family who was poor but had high status. He went to a Russo-native school and worked for a Russian lawyer and then went to the agriculture school in Pishpek. In October 1916 he went to the Tashkent normal school and then the Russian revolution happened. Up to this point he had no public life but in 1917 he returned to his hometown of Merke and founded the Union of Revolutionary Kazakh Youth. He returned to Tashkent in 1918 and was named Turkestan’s commissar for health.

In November 1918, Risqulov was reporting to the Turkestan Sovnarkom about the situation in Avilyo Ota uezd where 300,000 Kazakhs died from starvation, but the settlers levied an additional tax of 5 million rubles on the survivors. Risqulov called this what it was-colonial exploitation This inspired an ideology of communistic anticolonialism. In May 1920, Turar wrote:

“In Turkestan as in the entire colonial East, two dominant groups have existed and [continue to] exist in the social struggle: the oppressed, exploited colonial natives, and European capital.” Imperial powers sent “their best exploiters and functionaries” to the colonies, people who liked to think that “even a worker is a representative of a higher culture than the natives, a so-called “Kulturtrager.” - Adeeb Khalid, Central Asia, pg. 170

For Turar the communist revolution was synonym was anti-imperialist in all its forms. If the revolution could not throw off the shackles of imperialism, then it was a failed revolution. While we’ll talk more about his political career, his ideology raises an important question for us: what did communism actually mean to the indigenous people of Central Asia?

A revolutionary example for the Muslim World

The Jadids

For the Jadids, Bolshevism was a revolutionary force they could use to achieve modernization. Even though they adopted Bolshevik language, they could not map the Bolshevik obsession with class to their own society. Instead, they translated class warfare into anticolonialism, conflating Islam, nationalism, and revolution into a singular vision of anti-imperialism with their enemies including the ulama, the emirs, and the British (the conquerors of the Ottomans and the latest colonizer of Muslim lands). Fitrat even went as far as to write that India’s efforts to overthrow Britain’s rule was

“as great a duty as saving the pages of the Quran from being trampled by an animal…a worry as great as that of driving a pig out of a mosque.” - Adeeb Khalid, Making Uzbekistan, pg. 103

The Jadids wanted to create a Turkestan that was Muslim, nationalistic, and revolutionary, free of settler dominance and source of revolution for the Muslim world. They discovered that the Bolsheviks shared in their belief in women liberation, economic redistribution, and power of the people (or proletariat). Additionally, the Bolsheviks had the power to do what the Jadids could not: overthrow the settlers and the emirs just as they overthrew the Tsar and the aristocracy of Russia. In 1919, the First Congress of Muslim Communists passed the following resolution:

“To the revolutionary proletariat of the East, of Turkey, India, Persia, Afghanistan, Khiva, Bukhara, China, to all, to all, to all!

We the Muslim Communists of Turkestan, gathered together at our first regional conference in Tashkent, send you our fraternal greeting, we who are free to you who are oppressed. We wait impatiently for the time when you will follow our example and take control in your own hands, in the hands of local soviets of workers’ and peasants’ deputies. We hope soon to come shoulder to shoulder with you in your struggle with the yoke of world capitalism, manifested in the East in the form of the English suffocation of native peoples” – Adeeb Khalid, Making Uzbekistan, pg. 106

The Jadid’s embrace of an anticolonial revolution coincided with Afghanistan defeating the British in 1919, the wave of Ottoman POWs now free to roam Turkestan as well as an influx of Indian activists via Afghanistan. The Afghan Khan, Amanullah, looked to the Soviets for support against a British return. For their part, the Bolsheviks helped established a modern army in Afghanistan and allowed Afghanistan to open a consulate in Tashkent (but their relationship would always be strained whether because the Bolsheviks feared Afghan intervention in favor of the Bukharan Emir or because Afghanistan made no secret its desire to expand its influence into the rest of Central Asia).

The Indian activists (as well as many Ottoman expats) traveled through Afghanistan and into Turkestan to meet with the Bolsheviks, who represented an anti-colonial revolution about to overtake the world. Sakirbeyzade Rahim, an Anatolian representative would write in 1920 that:

“Turkestan is the path to liberation of the East, [and] the Red Soviets are the way to our natural and human rights. From now on, Turkestan and Turan will live only under the Red Soviet banner” - Adeeb Khalid, Making Uzbekistan, pg. 105

Yet, despite all of this revolution activity, these efforts never materialized into an organized revolution. Instead, many hopeful revolutionaries came together, talked, and started nascent organizations, but were never able to go further than that.

If the Jadids believed they were the leaders of a Muslim revolution, what did the Bolsheviks believe?

The Bolsheviks

Back in 1917, the Bolsheviks were very anticolonial and Muslim friendly, claiming:

"All you, whose mosques and shrines have been destroyed, whose faith and customs have been violated by the Tsars and oppressors of Russia! Henceforward your beliefs and customs, your national and cultural institutions, are declared free and inviolable! Build your national life freely and without hindrance.” - Adeeb Khalid, Making Uzbekistan, pg. 91

I don’t think this changed as they marched into 1918, but their understanding of what Turkestan needed conflicted with what the Jadids and Alash Orda were fighting for. The Bolsheviks thought in terms of class and industry and for them nationalism was the form class took in the colonies. So, while they initially supported nationalistic projects, they always intended for nationalism to be a steppingstone to true communism. But for the Jadids and Alash Orda, nationalism was the end goal. The Bolsheviks failed to win the Alash Orda’s trust and support and they were determined now to make the same mistake in Turkestan.

But what made Turkestan so important for the Bolsheviks? There is an ideological and an economic reason.

Ideologically, the Bolsheviks believed that converting Turkestan to communism would open the door for further communist expansion into the East. As Lenin argued in November 1919:

“It is no exaggeration to say that the establishment of proper relations with the peoples of Turkestan is now of immense, world-historic importance for the Russian Socialist Federated Soviet Republic. For the whole of Asia and for all the colonies of the world, for thousands and millions of people, the attitude of the Soviet worker-peasant republic to the weak and hitherto oppressed peoples is of very practical significance.” (Adeeb Khalid, Making Uzbekistan pg. 92)

This was particularly appealing as communist expansion floundered in the West. Trotsky would argue that:

“The road [to revolution in] Paris and London [lay] via the towns of Afghanistan, the Punjab, and Bengal” - Adeeb Khalid, Central Asia, pg. 172

They legitimately believed that Communism would flounder if it didn’t get a foothold outside of Russia and so they turned to the peoples the Tsar once oppressed. As they made overtures to the Jadids (and the Alash Orda) Lenin stressed the importance of not upsetting the indigenous peoples and to put the Russian settlers in their place before they ruined everything.

Vladimir Lenin

[Image Description: A black and white photo of a balding man staring intensely into the camera. He has a wiry mustache and goatee. He is wearing a white collared, button down shirt, a black tie, and a black suit]

Economically, the Soviets needed material and economic resources, especially cotton. The Russia the Soviet’s inherited was a stunted version of Tsarist Russia. No longer could they count on the economic and material resources of their western colonies and now the vast lands of the Steppe and Turkestan were at risk of escaping Russian control. The Commissar for Trade and Industry, L. B. Krasin, wrote:

“the recent reunion of Turkestan presents the opportunity…for making broad use of the region as well as of countries neighboring it…for the export of cotton, rice, dry fruits, and other goods necessary not only for the internal market of Russia, but also for its external trade.” - Adeeb Khalid, Making Uzbekistan, pg. 93

The challenge was benefiting from Turkestan’s resources without invoking the greed and bad memories of the Tsars.

By the end of 1918, the Jadids and Bolsheviks were working together to rebuild a functioning government in Turkestan. And yet, they both had two very different, clashing visions for Turkestan’s future. The Jadids entered 1919 needing to settle their differences with the Bolsheviks or risk the fate of the Alash Orda: a modernizing movement marginalized by its “allies” and the civil war.

Resources

Making Uzbekistan: Nation, Empire, and Revolution in the Early USSR by Adeeb Khalid

Russian Colonial Society in Tashkent, 1865-1923 by Jeff Sahadeo

Central Asia: a History by Adeeb Khalid

#queer historian#central asia#central asian history#history blog#turar risqulov#turkestan#abdurauf fitrat#russian civil war#central asian civil wars#pyotr kobozev#Spotify

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Russian Revolution and the Alash Orda

It’s 1917 and Central Asia is adjusting to a Tsarless reality. To briefly recap, because a lot has already happened and it’s about to get even more complicated:

Russian settlers created the Tashkent Soviet in the city, Tashkent. It is purely Russian managed and was created in response to indigenous organizing.

Various indigenous peoples such as the Jadids, the Ulama, and even the Alash Orda spent all year organizing different organs of government, ending 1917 with the Kokand Autonomy. This is an independent state created in Kokand, a city that neighbors Tashkent, in response to the Tashkent Soviet.

The Bukharan Emir kicked out his Jadids and relied on conservative elements in his society to strengthen his hold on power before Russia returns.

The Khiva Khanate is dependent on a warlord that is planning a coup.

Up to this point, we’ve focused on an Uzbek/Tajik Jadid perspective. Today we’ll be switching focus to the Kazakh and Kyrgyz intellectuals in the Steppe and the creation of the Alash Orda government and the Autonomous Alash state.

Alash Origins

As we discussed in our interview with Dr. Adeeb Khalid, the Muslim world was going through severe soul searching in the 1900s as they tried to understand the rise of European empires and the crumbling foundation of, not just the Ottomans, but Islamic nations in general. This was true in the Kazakh Steppe as well, although for the Kazakh intellectuals, it wasn’t just a question of how does Islam survive, but how do we define Kazakhnessand how do we ensure it survives?

The Kazakh identity crisis was sparked by the land crisis. We’ve talked about this in some of our other episodes, but starting in 1890, Russian settlers streamed into the Kazakh lands, taking important arable land that the nomadic Kazakhs relied on to survive. The Russians performed several exhibitions and surveys in the region between 1890 and 1912 and the Kazakh land grew ever smaller and smaller. Of course, this came to a head in 1916 and by 1917 the Tsar was gone, Russia was in disarray, and the Kazakh peoples had an opportunity to create their own government and address land rights.

Yet, while there was a real threat from Russian incursion, the Kazakhs also took advantage of opportunities the Russian presence offered. Many Kazakhs learned Russian and went to school in Russian run schools as well as local Kazakh schools (as opposed to the madrasa education mandated in places such as Tashkent and Bukhara), they had a long history of trading and even working with Russians, and the Kazakhs were also familiar with the Tatars and even the indigenous people of the Siberian oblast that the Russians relied on to support their colonial administration. And in an odd way the land crisis brought the Kazakhs closer to their Kyrgyz and Bashkir neighbors because they were experiencing the same problem.

This connection with Siberia seems to have provided the Kazakh intellectuals the support they needed to survive Russian persecution and take their ideas and grow it into a full-fledged movement. In fact, there is a great article by Tomohiko Uyama which details how the Russia attempts to banish important Kazakh activities such as Akhmet Baitursynov and Mirjaqip Dulatov to the outskirts of the Steppe (and sometimes in Siberia itself) allowed them to make widespread connection with other activities as well as each other and only fanned the flames of their work.

Akhmet Baitursynov described this time in Kazakh society as being caught between “two fires”: the influence of Muslim culture and the influence of Russian and Western culture. Out of this tension came the Alash, modernizing intellectuals. But even the Kazakh intellectuals couldn’t decide what was the best way to save Kazakhness, so they split into two big-picture groups: the Western-centric modernizers who were the editors for the newspaper Qazaq and the Islamic-centric modernizers who were the editors for the newspaper Aiqap. Some of the most important editors of the Qazaq newspaper was Akhmet Baitursynov, who was editor-in-chief, Alikhan Bokeikhanov, and Myrzhaqyp Dulatov, and they would go forth to become key members of the future Alash state. Some of the most important editors of the Aiqap newspaper were Mukhamedzhan Seralin, Bakhytzhan Qaratev, and Zhikhansha Seidalin.

What was the Alash platform? The two key pillars of their platform were land rights and preserving Kazakh identity.

Akhmet Baitursynov, Alikhan Bokeikhanov, and Myrzhaqyp Dulatov

[Image Description: An image of three Asian men sitting together. The man on the left has short black hair and a droppy mustache. He is wearing glasses and a white shirt, black tie, and black suit. The man in the middle has shaved black hair and a heavy mustache. He is also wearing a white shirt, black tie, and black suit. The man on the right has black hair and thin mustache. he is wearing a white shirt, a black bowtie, and a grey suit.]

Land Rights

We’ll start with land rights, because that is why really differentiates the Steppe from the rest of Central Asia. As we mentioned, the Russians were taking Kazakh land, and making land ownership dependent on one’s sedentary behavior. The Russians also published numerous pieces of propaganda belittling nomadic life. So, the Kazakhs had to determine whether to maintain their nomadic lifestyle or adopt a sedentary lifestyle.

Bokeikhanov, an editor of Qazaq newspaper, argued that the Russians wanted the Kazakh to settle down so they could give even more land (and most certainly the best land) to the Russians while giving the useless land to the Kazakhs and then blaming them for failing. Baitursynov picked up that argument and pointed out that the Kazakhs could not succeed unless they first learned how to farm, but the Russians weren’t interested in that aspect of sedentary life at all. They just pushed the Kazakhs to settle down and worry about the rest later. This could have come out of Russia’s (and the Tatar’s) lack of knowledge of the Kazakh situation but could have also been purposeful ignorance.

Bokeikhanov and Baitursynov argued for a gradual transition to sedentarization due the Steppe’s climatic conditions and lack of agricultural knowledge otherwise they would risk starvation (which Stalin proved in the 1930s). In a series of article, they argued that:

“If we ask what kind of economy is more suitable for Kazakhs-the nomadic or the sedentary-the question is incorrectly posed. A more correct question would be: what kind of economy can be practiced under the climatic conditions of the Kazakh steppe? The latter vary from area to area and mostly are not suitable for agricultural work. Only in some northern provinces do the climatic conditions make it possible to sow and reap. The Kazakhs continue wandering not because they do not want to settle down and farm or prefer nomadism as an easy form of economy. If the climatic conditions had allowed them to do so, they would have settled a long time ago.” - Gulnar Kendirbai, '"We are Children of Alash...", pg. 9

Displaying a better understanding of the science behind climate and agriculture than the Russians or the Soviets that would follow, the editors argued that the climate was the number one factor in nomadism and the Kazakhs could not become sedentary until they learned how to adjust to the demands of the land. Another article argued that sedentarism would lead to failed farming which would lead to wage work which led to great abuses and a higher chance of being converted to Christianity, so the Kazakhs must also learn handicrafts in addition to science. They described the Russian’s disinterested in their arguments as

“One may compare it with the dressing some Kazakh in European fashion and sending him to London, where he would either die or, in the absence of any knowledge and relevant experience, work like a slave. If the government is ashamed of our nomadic way of life, it should give us good lands instead of bad as well as teach us science. Only after that can the government ask Kazakhs to live in cities. If the government is not ashamed of not carrying out all the above-mentioned measures, then the Kazakhs also need not be ashamed of their nomadic way of life. The Kazakhs are wandering not for fun, but in order to graze their animals.” - Gulnar Kendirbai, '"We are Children of Alash...", pg. 10

It should be noted that the Alash did not equate nomadism with Kazakh identity. Instead, they argued that the Kazakhs (and I would argue extend that to the Kyrgyz and Bashkirs) were nomadic for a sensible and scientific reason and if the Russians were truly interested in helping the Kazakhs successfully transition to sedentarism, then they needed to provide the tools otherwise they were setting the Kazakhs up for failure.

Mukhamedzhan Seralin, an editor of the Aiqap newspaper, believed that the sooner the Kazakhs settled down the sooner they could gain a European level education and become competitive in the modern world while increasing the role of Islam in Kazakh society. He argued that:

“We are convinced that the building of settlements and cities, accompanied by a transition to agriculture based on the acceptance of lands by Kazakhs according to the norms of Russian muzhiks, will be more useful than the oppose solution. The consolidation of the Kazakh people on a unified territory will help preserve them as a nation. Otherwise, the nomadic auyls will be scattered and before long lose their fertile land. Then it will be too late for a transition to the sedentary way of life, because by this time all arable lands will have been distributed and occupied.” - Gulnar Kendirbai, '"We are Children of Alash...", pg. 10

The editors of Aiqap argued with the others on the need for greater education, various options for work, etc., but they believed that the Kazakhs could never have these things untilthey became sedentary whereas the editors of Qazap believed that the Kazakhs could not become sedentary until they had those things.

Kazakh identity

This leads to the second pillar in the Alash platform: preserving Kazakh identity.

For the Kazak intellectuals of all stripes, the second most important element of Kazakh society was education and literature. They were worried about the poor education opportunities that centered Kazakhness instead of Russianness, available to Kazakh children. Even after primary school, the Kazakh educational options were limited: either they try to get accepted into a madrassa or go to Russia for further education. The Kazakh intellectuals learned of the new teaching methods the Jadids championed via their southern neighbors as well as the Tatars in the area and used literature to encourage the Kazakh people to focus on schooling.

Akhmet Baitursynov was focused on reforming primary schools and the lack of teaching materials, especially on the Kazakh language. The Qazap newspaper was the only newspaper who wrote in pure Kazakh. Baitursynov answered their detractors as followed:

“Finally, we would like to tell our brothers preferring the literary language: we are very sorry if you do not like the simple Kazakh language of our newspaper. Newspapers are published for the people and must be close to their readers.” - Gulnar Kendirbai, '"We are Children of Alash...", pg. 19

The Kazakh intellectuals resisted the Tatar clergy’s attempts to subsume Kazakh language to the Tatar language, eventually arriving at a compromise. This pressure around language inspired Akhmet Baitursynov to reform the Kazakh language, creating spelling primers, and improving the Kazakh alphabet multiple times. This book was soon used in primary schools. He also published a textbook on the Kazakh language which studied the phonetics, morphology, and syntax of the Kazak language as well as a practical guide to the Kazakh language and a manual of Kazakh literature and literary criticism.

Meanwhile Bokeikhanov focused on creating a unified Kazakh history, believing that “History is a guide to life, pointing out the right way.” Together Bokeikhanov and Baitursynov focused on collecting Kazakh folklore, the history of their cultures and traditions, and shared world history with other Kazakhs through their newspapers. They encouraged Kazakh writers to write down their poems and stories, fearful that they would be lost if Kazakhs stuck purely to an oral tradition.

For intellectuals like Bokeikhanov and Baitursynov, Kazakhness was connected to a cultural identity as opposed to a religious identity. Bokeikhanov supported the idea of separation between religion and state and resisted the Aiqap’s call for introduction to Sharia law. Bokeikhanov believed that they should codify and record Kazakh laws, customs, and regulations to counter corruption and bribery, instead of relying on Sharia law. The Kazakh people had a different relationship to Islam than the other peoples of Central Asia (which may have been why the Russian missionaries were initially confident the Kazakhs would be easiest to convert). While the editors of Aiqap believed that sedentary life would create closer ties to Islam, the editors of the Qazap newspaper believed that Islam was a part of Kazakh society but didn’t equal Kazakh society.

1905 Russian Revolution

We’ve talked quite a bit about what the Alash stood for, but how did this translate into political action? The Kazakhs, like many other Central Asians, were initially excited about the 1905 Revolution, which created a State Duma that “welcomed” Central Asians as members for about two Dumas. When the Kazakhs could participate, they sent Alikhan Bokeikhanov and Mukhamedjan Tynyshpaev.

After the Second Duma, the Kazakhs were no longer permitted to send their own deputies, so they either had to rely on the Tatar deputies of the Muslim Faction of the Russian Duma or find support elsewhere. The Kazakh intellectuals believed that the Tatars had no real knowledge of Kazakh needs and distrusted them. So, they turned to the Russian Constitutional-Democratic Party i.e., the Kadets.

The Kadets sold themselves as an umbrella party that advocated for civil rights, cultural self-determination, and local legislation that would allow for the use of native languages at schools, local courts, administrations, and institutions. Even though the Kadets and the Alash didn’t agree on land rights, they still became allies. The tension between the two parties would not disappear, especially following the 1916 Revolt (which the Alash, like the Jadids, tried to prevent), but they also acknowledged that the Kadets were the only game in town.

1917 Russian Revolution

The 1917 Revolution changed all of that by allowing the indigenous peoples and settlers to create their own forms of government. In April 1917, they would form their own All-Kazakh Congress in Orenburg where they passed a resolution calling for the return of Steppe land to Kazakh peoples, control over local schools, and the expulsion of all new settlers in Kazakh-Kyrgyz territories.

The Alash used 1917 to win local support, focusing on winning the support of the most influential leaders of the local communities and trusting the elders to use tribal affiliations to mobilize the people under the Alash banner. The Kazakh intellectuals dug deep into Kazakh history to unify the people under Alash, the father of all Kazakhs, creating a unified history from creation to modernity. This can be thought of as similar to the Jadids attempts to trace Uzbekness back to Timur.

They also worked with the Provisional Government in Russia, and with the various councils and meetings held by their Jadid counterparts in Turkestan, but ran into great friction because their Tatar, Uzbek, Tajik, etc. counterparts didn’t truly appreciate how important the land issue was for the Kazakhs. They were also wary of the Ulama’s version of a council, wanting to maintain the traditionally limited role of Islam in Kazakh society.

Because of the differences in priorities and the role of Islam, the Alash would go their own way while continuing to support the efforts of other indigenous peoples. They would continue to serve on the various councils and even took part in the creation of the Kokand Autonomy, but knew they needed their own Congresses and their own autonomous state to protect their people and achieve meaningful land reform.

The Kokand Autonomy created three seats for Alash members, believing that two southern Kazakh oblasts would be part of the Kokand Autonomy whereas the Alash wanted a unified Kazakh state. Bokeikhanov explained the Alash’s position as follows:

“Turkestan should first become an autonomy on its own. Some of our Kazakhs argue it would be correct to join the Turkestanis. We have the same religion as the Turkestanis, and we are related to them. Establishing an autonomy means establishing a country. It is not easy to lead a country. If our own Kazakhs leading the country are unfortunate, if we make the argument that Kazakhs are not enlightened, then we can argue that the ignorance and lack of skill among the people of Turkestan is 10 times higher than among Kazakhs. If the Kazakhs join the Turkestani autonomy, it would be like letting a camel and a donkey pull the autonomy wagon. Where are we headed after mounting this wagon?” - Ozgecan Kesici, 'The Alash Movement and the question of Kazakh ethnicity', 1145

The Alash similarly considered joining the Siberian Autonomy movement but broke away once more over the issue of Kazakh autonomy. As Bokeikhanov explained:

“In practice, the autonomy of our Kazakh nation will not be an autonomy of kinship, rather, it will be an autonomy inseparable from its land.” - Ozgecan Kesici, 'The Alash Movement and the question of Kazakh ethnicity', 1146

Failing to find neighbors who would respect their autonomy and facing extreme violence because of the Russian Civil war that was working itself way through Siberia, the Alash would proclaim the creation of the Alash Autonomy during the Second All-Kazakh Congress in December 1917. This would be the first time a Kazakh state existed since the Russian invasion in 1848. This autonomous state would be ruled by the Alash Orda, a government made up of many of the modernizing intellectuals who worked at the Qazap and Aiqap newspapers. Alikhan Bokeikhanov was elected its president. Whatever relief they may have felt at creating a state government must have been quashed by the understanding that civil war was at the Steppe’s door and sooner or rather they would have to choose a side and risk their long fight for autonomy.

References

'Challenging Colonial Power: Kazakh Cadres and Native Strategies' by Gulnar Kendirbai, Inner Asia 2008, Vol 10 No 1

'"We are Children of Alash..." The Kazakh Intelligentsia at the beginning of the 20th century in search of national indeitty and prospects of the cultural survival of the Kazakh people' by Gulnar Kendirbai, Central Asian Survey, 1999, Vol 18 No 1

'The Alash Movement and the question of Kazakh ethnicity' by Ozgecan Kesici, Nationalities Papers, 2017, Vol 45 No 6

'Repression of the Kazakh Intellectuals as a sign of weakness of Russian Imperial Rule'by Tomohiko Uyama Cahiers du Monde russe 2015 Vol 56, No 4

Making Uzbekistan: Nation, Empire, and Revolution in the Early USSR by Adeeb Khalid

Russia and Central Asia: Coexistence, Conquest, Coexistence by Shoshana Keller Published by University of Toronto Press, 2019

#history blog#season 2: central asia#central asian history#central asia#kazakhstan#qazaqstan#qazaq history#kazakh history#alikhan bukeikhanov#Akhmet Baitursynov#Spotify

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Episode 30-Mustafa Cho’qoy the “Imperialist” Bogeyman from Turkestan

Mustafa Cho’qoy was the Minister of External Affairs for the Kokand Autonomy and when he wasn’t touring Turkestan trying to raise funds for a struggling government, he was reaching out to other countries to spread awareness of the deteriorating situation in Turkestan. Which makes sense when one considers that Russia was shattered by the rise of the Bolsheviks and engaged in a massive and devastating civil war. Who else were the people of Turkestan supposed to turn to if not other world powers when Russia was killing itself? However, for the Bolsheviks, serving in a government that wasn’t Communist sanctioned and reaching out to imperialists in the middle of an existential crisis was the ultimate betrayal and so they made Mustafa enemy number one amongst the Turkestan refugees.

But who was this guy and why did the Bolsheviks do so much to discredit him? Mustafa was a Kazakh born in Perovsky, in modern-day Kazakhstan, on December 25th, 1890. He was born into an aristocratic family with connections to powerful Warlords of the Steppe Hordes and maybe the Khiva Khanate. Thus, he was able to study at a Tashkent gymnasium before earning a law degree at the University of St. Petersburg. True to other Kazakh activists such as Alikhan Bokeikhanov (who heavily influence Mustafa’s political development) and Akhmet Baitursynov, Mustafa’s first foray into reshaping his society was to work within the Muslim Faction of the State Duma. This is different from Jadid activists who focused on the cultural and educational dimensions of activism and social rewiring. Mustafa served as a secretary to the Muslim Faction and wrote several speeches for deputies while also running his own liberal Kazakh newspaper the Birlik Tui (Banner of Unity).

Interestingly, while Mustafa was in Tashkent, he met the Russian Opera singer Maria Gorina. Maria was married to a lawyer at the time, but would divorce him and leave her old life behind to marry Mustafa on April 16th, 1918. They remained devoted to each other for the rest of their lives and Maria worked hard to preserve Mustafa’s writings and memory after he died in 1941.

Kokand Autonomy

When the Russian Revolution occurred, Mustafa was in Tashkent and involved with the growing Turkestan Autonomy movement. He would sit in the Shuro and take part in the multi-Muslim conferences as the people of Turkestan struggled to establish a government strong enough to weather the storm that was the Russian Civil War.

Interestingly, despite being involved with the Alash Orda movement, Mustafa chose to serve as Minister of External Affairs for the Kokand Autonomy (if we remember correctly, many members of Alash Orda actually returned to the Steppe to create the Alash Autonomy because they felt Kazakh interests weren’t be heard or represented in Tashkent). As Minister, Mustafa took part in efforts to raise funds, such as his January 14th trip to fundraise in Andijan, and also to raise troops for Kokand’s non-existent army. But, like many other Kokand Ministers, Cho’qoy often met disappointment and frustration in carrying out his governmental duties.

When Kokand’s neighbors, the Tashkent Soviet sent an army to overthrow the Kokand Government, Cho’qoy fled. He escaped Tashkent into the Ferghana where he stayed for a few months. Following the fall of the Kokand autonomy, he would write:

“the core of the autonomists remaining after the defeat at Kokand called upon its supporters to work with existing authorities in order to weaken the hostility directed at the indigenous population by the frontier Soviet regime." - Adeeb Khalid, Making Uzbekistan, pg. 72

Which may explain why he initially fled to Moscow to negotiate with the Bolsheviks where he was arrested by the White General Kolchak as “enemy of the Russian state”. He escaped and went to Ashgabat where the Russian Mensheviks just overthrew Soviet power and was setting up its own autonomous government.

While in Ashgabat, he met Vadim Chaikin, a Socialist Revolutionary lawyer, and together they sent a telegram to the Paris Peace Conference. The telegram, titled “Committee for the Convocation of the Constituent Assembly of Turkestan asking for the congress to recognize Turkestan’s unity and its right to a “Free and autonomous existence in fraternal friendship with the people of Russia.” (Adeeb Khalid, Making Uzbekistan, pg. 82).

The telegram went nowhere, but condemned Cho’qoy, in the eyes of the Bolsheviks, as a class traitor willing to sell out his own people to capitalists and imperialists. Choqoy stayed in Ashgabat for two years before fleeing the oncoming Red Army. He eventually resettled in Turkey for a few years before traveling to Paris, with help from former President of the Russian Provisional Government, Aleksandr Kerensky.

The Archdemon of Paris

While in Paris, Cho’qoy would become active in the Russian emigre circles as a writer of newspapers edited by Kerensky and Miliukov. At first, he found a home amongst the Russian immigrant community, but, given his experience during the civil war and being cut off from his homeland, he grew increasingly anti-Bolshevik and nationalistic in view and so he found refuge in the Turko-Tatar immigrant community within Europe and Turkey. He associated with other Bolshevik bogeymen such as Ahmed Zeki Veldi Togan and Usmon Xojao’g’li. While in exile, he published several papers such as Yosh Turkistan (Young Turkestan), his own memoirs, and lectured widely. He settled in Nogent-sur-Marne, a village outside of Paris, but traveled throughout Europe, setting himself as the spokesman for Turkestan. Tensions within the Turkestan immigrant community grew and eventually Mustafa split from Togan, who seemed to have been going down a more pan-Turkic path as opposed to Mustafa’s more nationalist, Turkestan forced approach.

Because of whom Cho’qoy was associating with, his writing, and his outspokenness, he became foreign enemy number one in the mind of the Bolsheviks. Any known or suspected association with him often meant a death sentence for those he left behind in Turkestan. Despite his supposed influence, Cho’qoy struggled in exile, trying to get his work published and trying to get the world to notice what was occurring in Turkestan. While Cho’qoy was able to find other immigrants within Paris and around the world, he was cut off from Turkestan itself. So Cho’qoy wasn’t connected to what was happening on the ground nor could he shape what was occurring within Turkestan. He ended up being an immigrant that could only speak on situations as they were before he fled, unable to connect with the people most affected by the Soviet Union, fighting with other immigrant writers and spokesmen, and taking to a European audience that had long forgotten Turkestan.

Cho’qoy, like the Kokand Autonomy, was a danger to the Bolsheviks because of what he could have been. He offered an other option to disgruntled Turkestani immigrants and citizens of Turkestan, he provided uncensored and uncontrollable critique of a Soviet system the Bolsheviks were struggling to implement within Central Asia, and was connected with many other bogeymen that haunted Bolshevik dreams. While it is questionable what Cho’qoy could have achieved for Turkestan from Paris, the fact that he was out there at all was enough for the Bolsheviks.

In a Nazi Prison

World War II led to the fall of France to the Nazis and in 1941, they arrested Cho’qoy. He was placed in a camp in Compiegne with other Russian emigres. He was summoned to Berlin to work with other Central Asian POWs brought from the front and created a German Turkestan Legion. This would be the first time Cho’qoy spoke to someone from Central Asia since he fled Turkestan. He was astonished by their conditions, but also traumatized by Nazi brutality. He wrote:

“It is not possible to relate all the various cases of senseless executions in Debica. Every time I left the camp, I saw several corpses with smashed skulls…One wonders how much of this is because of the “Asiatic” contagion about which the loudspeakers scream everyday all over Germany.” - Adeeb Khalid, Making Uzbekistan, pg. 275

He had no sympathy with the Nazis but understood that a Nazi victory could mean the fall of the Soviet Union. He wrote:

“Yes, we have no path, other than the anti-Soviet path, other than the wish for victory over Soviet Russia and over Russian Bolshevism. This path, regardless of our will, is laid through Germany. And it is strewn with the corpses of those executed in Debica.” - Adeeb Khalid, Making Uzbekistan, pg. 275

This was a “small and pitiful speculative trade in human misfortune” necessary for national liberation. (Adeeb Khalid, Making Uzbekistan, pg. 275, Khalid) He discussed the idea of a Turkestan Legion and the future of Muslim states with Nazi General Alfred Rosenberg, laying down conditions that would save the lives of Muslim Russian POWs. After realizing the Nazis were negotiating in bad faith, he declared to lead the Turkestan Legion. Mustafa died on December 27th, 1941, supposedly from typhus he contracted while in the Compiegne Camp.

References

Making Uzbekistan: Nation, Empire, and Revolution in the Early USSR by Adeeb Khalid

Central Asia: a New History from the Imperial Conquests to the Present by Adeeb Khalid

The Politics of Muslim Cultural Reform by Adeeb Khalid

#central asian history#central asian civil wars#central asia#mustafa cho'qoy#history blog#queer historian#Spotify

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Creation of the Central Asian Soviet Republics

During the last few episodes, we’ve discussed the Russian Revolution, the fall of the emirs, the Basmachi insurgency, the destruction of the Kokand Autonomy and the neutering of the Musburo. Unsurprisingly, all of this upheaval was horrible for everyone in the region and made governing almost impossible. Frunze, who was responsible for a lot of the upheaval, left in the fall of 1920, and did not see the outcomes of his explosive decisions.

Instead, it was up to the Communist officials and the Indigenous actors to create a new Central Asia. Unfortunately, they could not agree on the methods they should use, the ideological foundations of their new creation, or even what that new creation would look like. They didn’t trust each other; the Bolsheviks believed the indigenous actors weren’t proper Communists and the indigenous actors were annoyed that the Bolsheviks thought they knew best and purposely ignored all of their proposed solutions.

Things were worse for the people of the region. The Jadids were never popular even before the wars and this distrust grew as they sided with the Bolsheviks and tried to create a new world for the region. And so, as a farmer or merchant or just regular person in Central Asia, you had three choices: side with the Basmachi and risk death or losing everything to their raiding bands, side with the Jadids and Bolsheviks and support something that seems incompatible with one’s culture and religion, or try to survive on your own and at the mercy of all different factions and sides.

The core struggle can be best described by this quote from Lenin.

[Image Description: A colored gif of three men sitting together in a bowling alley. Two men are facing the camera and the third man is between the two men with his back to the camera. The man on the left has long hair and a long, scraggy beard. He is wearing a green shirt with a beeper hanging from the color. The man on the right is a bigger white man with short hair and beard and mustache. He is wearing light brown sunglasses and a short sleeve purple stripped shirt. The man in the middle has shoulder length hair and is wearing a green t-shirt. The bowling alley is pink and has blue star decorations on the walls.]

In 1921, he wrote:

“It is devilishly important to conquer the trust of the natives; to conquer it three or four times to show that we are not imperialists, that we will not tolerate deviations in that direction” - Adeeb Khalid, Making Uzbekistan, 165

Not sure if Lenin even noticed the stark contradiction between “conquering” someone’s trust and somehow proving you’re not an imperialist or conqueror. Maybe he meant well, but we’re already off to a rocky start.

Communist Paranoia

A big source of tension between the Bolsheviks and the indigenous actors of Central Asia was the difference in ideology and goals.

We’ve talked a lot about the Jadid’s ideology and their goals. The Jadids in Bukhara and Turkestan wanted to create a modern state built around the principles of nationalism. They wanted to create a state that enjoyed full sovereignty and membership amongst the world of nation-states. They wanted to develop their own economy but maintaining control over their own resources and they wanted to education their citizens to combat “ignorance” and “fanaticism.” They wanted to preserve Islam, but also modernize it by bringing Muslim institutions under control of the government.

The Communists, however, wanted to create a perfect Communist society which required loyal and ideologically pure cadre. The only way they could do this in Central Asia was to recruit the population into the party. They knew their best demographic were the youth, the women, and the landless and poor peasants. The children they recruited into their youth group known as Komsomol and the brought the women’s organization, Zhenotdel to Central Asia. They also created the Plowman union for the poor. They would use this union to implement the land and water reform of the 1927, but were disbanded after serving their purpose.

Political Cadre of Turkestan Front. Frunze is seated in second row, two from the left

[Image Description: A black and white photo of a large crowd of men and women sitting together outside. Behind them is a clear sky, a stone building, and trees. The people are wearing a combination of white shirts and dresses and grey shirts and dresses]

Yet, the Communists couldn’t see through their own racism and chauvinism when it came to accepting local actors to the Communist Party. The Communist Party was the key feature of public life. It was the center of all political activity and thus membership was highly coveted. However it required an impossible ideological purity requirement which made many Communists paranoid. Their inability to a pure Communist a hundred percent of the time, or even to define what that meant, made them reliant on frequent purges to ensure the party remained pure.

[Image Description: A colored gif of a bald, naked white man wearing nothing but white underwear, lying on the floor, and looking up at the camera, saying "I just want to be pure."]

One Communist official complained that he was dissatisfied after talking to a Turkmen member of the Merv Communist party in 1923. He wrote:

“We started asking [him] why he had entered the party, to which he answered that he himself did not know, and to the question whether he knew if a Communist is a good person or bad, he said that he knew nothing. And to the question of how he got into the party, he answered simply that a little while back a comrade came here who said, “You are a poor man, you need help, and you should join the party; for this will get you clothing and matches and kerosene.” - Adeeb Khalid, Making Uzbekistan, pg. 170

While the rank and file were often uneducated, the local leaders tended to be part of the modernizing elite who wanted to use Soviet institutions to bring about reforms, they often came from prosperous urban families, graduates of Russian-native schools, and had been active in Muslim politics in 1917. Some had been recruited by Risqulov before he was ousted, had caught the eye of various Russian Communist officials, or even fought against the Basmachi and earned the Soviet’s trust that way. By these leaders were hard to find and so from 1920-1927, the Soviets were forced to rely on “impure” and “nationalistic” local leaders while building a cadre of “pure” communists they would be able to rely on in the future.

Turar Risqulov

[Image Description: A black and white pciture of a man standing at an angle. He is looking at the camera. He has bushy black hair and a short mustache. He is wearing round, wire frame glasses. His hands are in his dark grey suit pants. he is wearing a white button down shirt, a grey tie, and a dark grey vest and suit jacket. A flag is pinned to his suit lapel.]

What made things worse was that the Soviets didn’t even treat the Central Asian as equals within the Communist framework. When the Bukharan Communist Party tried to join the Comintern, they were accepted as a “sympathetic organization” and then merged with the Russian Communist Party.

This desire for loyal cadre and the educational efforts pursued by the communists and local reformers, contributed to the creation of a group of men who called themselves “Young Communists.” They challenged the supremacy of the KPT, accusing them of compromise, patriarchy and careerism. The Young Communists claimed they were the most “Marxistically educated” of the Muslim Communists and demanded the “total emancipation of the party from the past [which] had not yet been accomplished and that KPT be cleansed of all members who were “factional-careerist” and “patriarchal-conservative.” In 1924, they launched a campaign to ban the heavy cloth and horsehair veil customarily worn by women. They were equally frustrated by the Russian Communists, claiming:

“Historically speaking, the last conquerors of Turkestan were the Slavs, and Turkestan was liberated from their oppression only after the great social revolution. But this liberation is only formal. Because the proletariat is from the ruling nation, the disease of colonialism has damaged its brain. This fact has had a great impact on the revolution in Turkestan” - Adeeb Khalid, Making Uzbekistan, pg. 175

The Soviets were wary of the Young Communists, but would recruit them into the governments of the different Central Asian States after they were created in 1924.

Crafting a Governing Body

In order to make the region more manageable, the Soviets broke the region into several different Soviet republics. The Bukharan Soviet People’s Republic managed the territory that once belonged to the Bukhara Emirate. Similarly, the Kazakh Steppe became the Kirghiz Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic, the Khivan Emirate became the Khorezm Soviet People’s Republic and Turkestan became the Turkestan Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic. These republics were governed by chairmen.

Map of Central Asian Republics in 1922