#kenyon farrow

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

To be sure, not all of the problems of the LGBTQ community can be blamed on the distraction of marriage equality. But the previous 15 years leading up to that SCOTUS decision have left our community more visible but under greater threat, with even fewer civil and legal protections and fewer resources to fight back―and with a community that’s more fractured because at least a quarter of us believe that they’ve won, all while forgetting that “You never completely have your rights, one person, until you all have your rights” (Marsha P. Johnson). We can’t control what the opposition does. But this is a moment for us to reevaluate and reinvest in our community, for our very survival.

Kenyon Farrow in TheBody. Eight Years After Same-Sex Marriage Became Law, We’re Worse Off

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

(Past) A House is a Temple

By Kenyon Farrow

This section discusses the value of some dance clubs as places where queer people of color could express individuality, spiritual release, and creative energy while also providing a space for solidarity in a time of crisis. The importance of dance clubs as sacred spaces for communities that were heavily impacted by HIV/AIDS in the first two decades of the epidemic is shown through the author's personal experience. Farrow discusses how it was a space that people could make connections through dance and movement, sometimes without even knowing the other person's name. They also describe how this space allowed people to express intense emotions related to the grief and pain caused by HIV/AIDS. Farrow reiterates the spiritual experience of being in dance clubs by describing how "you lose your sense of self and become completely one with everything around you" (96 Page & Woodland). This is a prime example of how creative expression has been used as resistance by marginalized communities throughout history. This connects to the long history of the use of music as resistance by black populations in the United States. I specifically enjoyed his discussion of how specific songs prompted visceral emotional reactions from people because of the poignant connection to their lived experiences. Personally, I have also used music to process emotion in a lot of ways, and I find this use of music very powerful in processing strong emotions.

Learn more about ACT-UP and how they continue to provide resources for those living with HIV/AIDS and promote AIDS research.

0 notes

Text

youtube

Past: Reckoning with Roots and Lineage - A House is a Temple

Kenyon Farrow contributes this chapter to the anthology of Healing Justice Lineages, discussing the role of clubs and house music for the queer community during the AIDs crisis. Music and dance are part of queer expression and Farrow emphasizes how clubs created quasi-religious environments for celebration, renewa;, grief, and belonging. He writes, “Far from being just spaces of drug use and mindless music, house music spaces were and are still very powerful locations of emotional and spiritual care for people who found little else in the world to uplift and celebrate them without reservation or condition,” pg 97. This chapter did get me to shed some tears over the loss of a large proportion of the generation of queer people lost to the inadequate response to the AIDs epidemic. The tragic loss of those people has led to the successive generations of queer folx having very few elders to learn from and guide us through joy and pain.

I’m very interested in queer music and art that shows queerness as beautiful, artistic, and natural. The music video for Camelias by MIEL is a beautiful celebration of queer imagery that is very soothing to me. While it is not reflective of the house music described by Farrow, it feels tied to my sense of modern queerness.

0 notes

Video

tumblr

A Black Feminist Homecoming

#A Black Feminist Homecoming#amber ruffin#evelyn from the internets#the original pinettes#the baby dolls#nana anoa nantambu#chari l.#alexis pauline gumbs#sangodare#raquel willis#andrea jenkins#barbara smith#paris hatcher#crystal des-ogugua#moya bailey#ola ronke#m adams#nalo zidan#kenyon farrow#stanley fritz#byron hurt#adaku utah#julia bennet#for the gworls#women with a vision#rede mulheres negras#mama fund#lead to life#mwende 'frequency' katwiwa

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Here’s some links to articles about Dave Chappelle’s The Closer by Black queer people:

Dave Chappelle’s Betrayal, Saeed Jones in GQ

Dave Chappelle represents a segment of society..., twitter thread by Raquel Willis

Dave Chappelle’s ‘The Closer’ Netflix special is no laughing matter to LGBTQ people like me, Michael Crawford in NBC News

‘Too smart’ Dave Chappelle has fallen for ‘old right wing political device,’ Kenyon Farrow in The Columbus Dispatch

Opinion: Dave Chappelle’s Brittle Ego, Roxane Gay in The New York Times

National Black Justice Coalition’s statement about ‘The Closer’

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

i finally sat down this AM to do some research on this cat. i've intended to do so for about 8 years or so. why did i put it off? i cannot say.

it was kind of disturbing to find what i did. i won't go into details in this post. i don't think most people read the things i post anyway.

to be brief & blunt, i don't comprehend how people refuse to do independent research. the web is filled w/informational resources. the way urban legend often seems to be incorporated into belief & conspiracy ideation is genuinely fascinating.

sometimes observation & study leave me feeling like an utter outcast. it can definitely makes conversation w/certain people no bueno.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

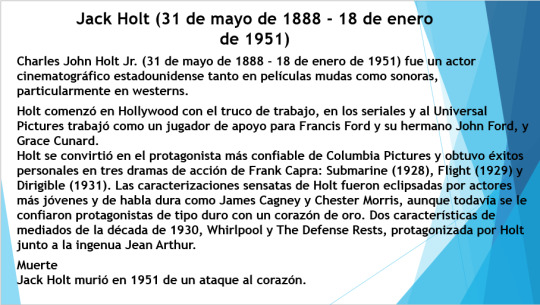

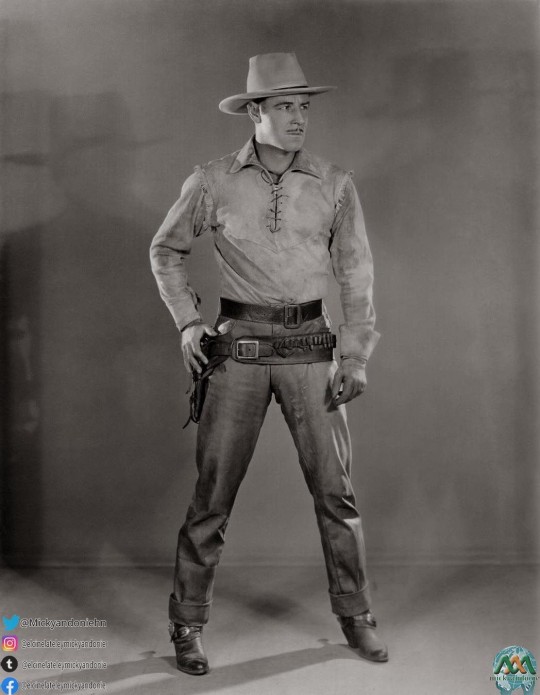

Jack Holt.

Filmografía

- Salomy Jane (1914) como un vaquero que juega al solitario en el salón (sin acreditar)

- La llave maestra (1914, serial) como Donald Faversham

- La moneda rota (1915, serial) como Capitán Williams

- Joya (1915) como Nat Bonnell

- La tonta de Portici (1916) como Conde

- Corazones desnudos (1916) como Howard

- Liberty (1916, serial) como el capitán Bob Rutledge

- Salvando el apellido (1916) como Jansen Winthrop

- El cáliz del dolor (1916) (sin acreditar)

- La oveja negra de la familia (1916) como Kenneth Carmont

- Juana la mujer (1916) (sin acreditar)

Patria (1917, serial)

- El costo del odio (1917) como Huertez

- Sacrificio (1917) como Paul Ekald

- Dando una oportunidad a Becky (1917) como Tom Fielding

- El santuario interior (1917) como vizconde D'Arcourt

- El pequeño americano (1917) como Karl von Austreim

- La llamada del este (1917) como Alan Hepburn

- El juego secreto (1917) como Maj. John Northfield

- Las perlas ocultas (1918) como Robert Garvin

- La garra (1918) como Maurice Stair

- One More American (1918) como Sam Potts

- Rumbo al sur (1918)

- Ámame (1918) como Gordon Appleby

- El honor de su casa (1918) como Robert Farlow

- La ley del hombre blanco (1918) como Sir Harry Falkland

- La garra de hierro (1916, serial) como Maurice Stair

- Un cortejo del desierto (1918) como Barton Masters

- Ojos verdes (1918) como Pearson Hunter

- El anillo de matrimonio (1918) como Rodney Heathe

- El camino a través de la oscuridad (1918) como Duke Karl

- El hombre de Squaw (1918) como Cash Hawkins

- Tramposos tramposos (1919) como Tom Palmer

- Un romance de medianoche (1919) como Roger Sloan

- Para mejor, para peor (1919) como Crusader

- La mujer que me diste (1919) como Lord Raa

- Una oportunidad deportiva (1919) como Paul Sayre

- La mujer casada con Michael (1919) como Michael Ordsway

- The Life Line (1919) como Jack Hearne, el Romany Rye

- Kitty Kelly, MD (1919) como Bob Lang

- Victoria (1919) como Axel Heyst

- La mejor de las suertes (1920) como Kenneth, Lord Glenayr

- Crooked Streets (1920) como Rupert O'Dare

- En poder del enemigo (1920)como el Coronel Charles Prescott

- Los pecados de Rosanne (1920) como Sir Dennis Harlende

- Locura de verano (1920).

-All Soul's Eve (1921) como Roger Heath

- Patos y dracos (1921) como Rob Winslow

- El romance perdido (1921) como Mark Sheridan

- La máscara (1921) como Kenneth Traynor / Handsome Jack

- Después del espectáculo (1921) como Larry Taylor

- El comediante sombrío (1921) como Harvey Martin

- La llamada del norte (1921) como Ned Trent

- Comprado y pagado (1922) como Robert Stafford

- Al norte del Río Grande (1922) como Bob Haddington

- Mientras Satanás duerme (1922) como Phil

- El hombre invencible (1922) como Robert Kendall

- En alta mar (1922) como Jim Dorn

- Making a Man (1922) como Horace Winsby

- Nadie es dinero (1923) como John Webster

- La garra del tigre (1923) como Sam Sandell

- Un caballero del ocio (1923) como Robert Pitt

- Hollywood (1923) como él mismo

- El tramposo (1923) como Dudley Drake

- The Marriage Maker (1923) como Lord Stonbury

- No lo llames amor (1923) como Richard Parrish

- El lobo solitario (1924) como Michael Lanyard

- Wanderer of the Wasteland (1924) como Adam Larey

- Manos vacías (1924) como Grimshaw

- North of 36 (1924) como Don McMasters

- Eve's Secret (1925) como duque de Poltava

- La manada del trueno (1925) como Tom Doan

- La luz de las estrellas occidentales (1925) como Gene Stewart

- Mesa de caballo salvaje (1925) como Chane Weymer

- La carretera antigua (1925) como Cliff Brant

- La colina encantada (1926) como Lee Purdy

- Caballos de mar (1926) como George Glanville

- La diosa ciega (1926) como Hugh Dillon

- Nacido en el oeste (1926) como 'Colorado' Dare Rudd

- Río abandonado (1926) como Nevada

- El hombre del bosque (1926) como Milt Dale

- El jinete misterioso (1927) como Bent Wade

- La tigresa (1927) como Winston Graham, conde de Eddington

- La advertencia (1927) como Tom Fellows / Coronel Robert Wellsley

- The Smart Set (1928) como Nelson

- El pionero en fuga (1928) como Anthony Ballard / John Ballard

- Corte marcial (1928) como James Camden

- El pozo de agua (1928) como Philip Randolph

- Submarino (1928) como Jack Dorgan

- Avalancha (1928) como Jack Dunton

- Sunset Pass (1929) como Jack Rock

- El asunto Donovan (1929) como Insp. Killian

- Padre e hijo (1929) como Frank Fields

- Vuelo (1929).

-Venganza (1930) como John Meadham

- La Legión Fronteriza (1930) como Jack Kells

- La isla del infierno (1930) como Mac

- The Squealer (1930) como Charles Hart

- El último desfile (1931) como Cookie Leonard

- Dirigible (1931) como Jack Bradon

- Subway Express (1931) como Inspector Killian

- Hombros blancos (1931) como Gordon Kent

- Cincuenta brazas de profundidad (1931) como Tim Burke

- Un asunto peligroso (1931) como el teniente McHenry

- Maker of Men (1931) como entrenador Dudley

- Detrás de la máscara (1932) como Jack Hart, también conocido como Quinn

- Corresponsal de guerra (1932) como Jim Kenyon

- This Sporting Age (1932) como el capitán John Steele

- Hombre contra mujer (1932) como Johnny McCloud

- Hollywood Speaks (1932) como él mismo

- Cuando los extraños se casan (1933) como Steve Rand

- La mujer que robé (1933) como Jim Bradler

- El demoledor (1933) como Chuck Regan

- Maestro de hombres (1933) como Buck Garrett

- Whirlpool (1934) como Buck Rankin

- Luna negra (1934) como Stephen Lane

- La defensa descansa (1934) como Matthew Mitchell

- Lo arreglaré (1934) como Bill Grimes

- El mejor hombre gana (1935) como Nick Roberts

- Tormenta sobre los Andes (1935) como Bob Kent

- El extraño indeseable (1935) como Howard W. Chamberlain

- El despertar de Jim Burke (1935) como Jim Burke

- El rebelde más pequeño (1935) como el coronel Morrison

- Aguas peligrosas (1936) como Jim Marlowe

- San Francisco (1936) como Jack Burley

- Crash Donovan (1936) como 'Crash' Donovan

- Fin del camino (1936) como Dale Brittenham

- Al norte de Nome (1936) como John Raglan

- Problemas en Marruecos (1937) como Paul Cluett

- Madera rugiente (1937) como Jim Sherwood

- Forajidos de Oriente (1937) como Chet Eaton

- Atrapado por G-Men (1937) como G-Man Martin Galloway, haciéndose pasar por Bill Donovan

- Bajo sospecha (1937) como Robert Bailey

- En los titulares (1938) como el teniente de policía Lewis Nagel

- Vuelo a ninguna parte (1938) como Jim Horne

- Reformatorio (1938) como Robert Dean

- El crimen toma vacaciones (1938) como Walter Forbes

- El extraño caso del Dr. Meade (1938) como Dr. Meade

- Enemigos susurrantes (1939) como Stephen Brewster.

-Atrapado en el cielo (1939) como Major

- Fugitivo en libertad (1939) como Tom Farrow / George Storm

- Poder oculto (1939) como Dr. Garfield

- Fuera del límite de las tres millas (1940) como Agente del Tesoro Conway

- Pasaporte a Alcatraz (1940) como George Hollister

- Fugitivo de un campo de prisioneros (1940) como Sheriff Lawson

- El gran robo del avión (1940) como Mike Henderson

- La gran estafa (1941) como Jack Regan

- Holt del servicio secreto (1941, serial) como Jack Holt / Nick Farrell

- Thunder Birds (1942) como el coronel MacDonald

- Northwest Rangers (1942) como Duncan Frazier

- Gente gato (1942) como El comodoro

- Eran prescindibles (1945) como el general Martin

- My Pal Trigger (1946) como Brett Scoville

- Vuelo a ninguna parte (1946) como el agente del FBI Bob Donovan

- The Chase (1946) como Cmdr. Davidson

- Chica renegada (1946) como Maj.Barker

- La frontera salvaje (1947) como Charles 'Saddles' Barton

- El tesoro de la Sierra Madre (1948) como Flophouse Bum (sin acreditar)

- El guardabosques de Arizona (1948) como Rawhide Morgan

- The Gallant Legion (1948) como Capitán Banner

- La fresa ruana (1948) como Walt Bailey

- Pistolas cargadas (1948) como Dave Randall

- El último bandido (1949) como Mort Pemberton

- Brimstone (1949) como el mariscal Walter Greenslide

- Task Force (1949) como Capitán Reeves

- Desierto rojo (1949) como Deacon Smith

- Las mujeres de los Dalton (1950) como Clint Dalton - Mike Leonard

- El regreso del hombre de la frontera (1950) como Sheriff Sam Barrett

- Trail of Robin Hood (1950) como él mismo

- Rey del látigo (1950) como el banquero James Kerrigan

- Across the Wide Missouri (1951) como Bear Ghost (papel final de la película).

Créditos: Tomado de Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jack_Holt_(actor)

#HONDURASQUEDATEENCASA

#ELCINELATELEYMICKYANDONIE

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Social services as crime control “Abolitionists often emphasize the historical and political construction of crime and how crime control in the post-Emancipation era was used to limit Black people’s freedom and movement. In Are Prisons Obsolete?, Angela Y. Davis writes, “In the immediate aftermath of slavery, the southern states hastened to develop a criminal justice system that could legally restrict the possibilities of freedom for newly released slaves.” In the field of criminal-justice studies, there is a wing called radical criminology. While not all scholars of this subarea promote abolition, they do raise critical questions about crime as a sociopolitical construction, as well as the study of crime itself.

In other words, what do people talk about when they talk about crime? Some who employ the suburb frame address this question. For example, in her recent op-ed for the New York Times, “Yes, We Mean Literally Abolish the Police,” Mariame Kaba discusses how crime is popularly imagined versus what actually puts many people in contact with the police: “The first thing to point out is that police officers don’t do what you think they do. They spend most of their time responding to noise complaints, issuing parking and traffic citations, and dealing with other noncriminal issues.” On Twitter, Josie Duffy Rice has stressed the same.

Unlike those, such as Kaba and Duffy Rice, who underscore that criminalization is a targeted process, proponents of the suburb model like that proffered by Ocasio-Cortez reify an explanation of crime consistent with a liberal concern about deprived groups acting out. For example, in a June 10 interview on Good Morning America (GMA), George Stephanopoulos asked Ocasio-Cortez to comment on Joe Biden’s refusal to support defunding the police. Ocasio-Cortez responded by situating defunding the police as divestment-investment. As she told Stephanopoulos, “not enough resources are being put into the very kinds of social programming and investments that prevent crime and social discord in the first place.”

While acknowledging in her Instagram response that “something harmful,” including “harmful crimes” can happen in the affluent, white suburb, Ocasio-Cortez makes suggestive comments regarding the healthiness of these communities. At the Rising Majority event, she described the suburb as a place where “schools are fully funded, and there are trees in the street, and children can eat nutritious food, where their brains are able to adequately develop, and that there are policies that people fight for so that the community is healthy enough . . .”

Talk of “crime and social discord,” as well as references to “nutritious food” and brains being “adequately able to develop” run the risk of aligning a discussion of crime control with the trope of Black-on-Black violence, which started gaining traction among politicians and pundits in the 1980s. While many proponents of the Black-on-Black violence discourse are conservatives, David Wilson emphasizes, “liberals were complicit in this constructing.” Unlike political and fiscal conservatives, liberals might deploy the narrative of Black-on-Black violence to solicit support for “full-scale liberal intervention into inner cities” and in the process integrate “notions of powerful local culture with imperfect capitalist economic and political foundations.”

While Ocasio-Cortez would likely reject racist imagery depicting Black people as violent, comments about healthy nutrition and developing brains put her suburb model dangerously close to the liberal version of the Black-on-Black violence framing. It also hints at an epigenetic approach, which posits that structural factors, including racism and deprivation of needed social resources, impact social groups on a biosocial level and that this can shape sociological outcomes. Unfortunately, as Kenyon Farrow has pointed out, epigenetic discourse has become popular among those expressing a commitment to fighting racism.

Affluent, white suburbanites have different priorities During her GMA interview, Ocasio-Cortez stated, “And it may sound strange, but many affluent suburbs have essentially already begun pursuing a defunding of the police in that they fund schools, they fund housing, and they fund health care, more as their number one priorities.”

This messaging suggests that affluent, white suburbanites were once over-policed and underfunded but have taken the steps to get their priorities in order. More, the suburban model, as employed by Ocasio-Cortez, obscures how racial capitalism structures public finance, such as how racism and pro-policing politics shape national, state, and city economies in terms of the gutting of the social welfare state, the racial politics of municipal credit, corporate funding of police organizations, residents paying for punishment, “police brutality bonds,” and taxpayer politics.

In doing so, the suburban frame fetishizes the affluent, white suburban taxpayer as leading the charge for abolition in practice.

Camille Walsh examines how, as a trope, “the taxpayer” is a citizen who is white, tax paying, and deserving. While African Americans have at times invoked taxpayer rights, Walsh shows how “the taxpayer” is a raced figure that implies “an ‘untaxed other’ who does not pay taxes and therefore has not earned rights.” Raúl Carrillo and Jesse Myerson note a related danger of the “taxpayer” frame: “Although most of us pay taxes of some kind, every time we say ‘taxpayer money’ we prolong the illusion that society depends on certain kinds of people so we can have nice things.” Ocasio-Cortez’s depiction of affluent, white suburbanites as simply pursuing different budget priorities politically puts “the taxpayer” in the driver’s seat and also suggests that affluent, white suburbanites are the vanguard of abolitionist budgeting. In this scenario, their tax revolt is against the carceral state.

Ocasio-Cortez’s suburb model and its deployment to support defunding the police treat state and city budgets as if they are balanced like a household budget. She is not alone in this approach, as many divest-invest strategies do the same. What Carrillo and Myerson draw our attention to is that there is actually enough money to fund whatever we want: “Politicians may act like the U.S. government has the same constraints as a household or business, but the U.S. government can’t go broke. It can impose silly constraints on itself, like the debt ceiling, but people who actually know how monetary operations work know the U.S. government cannot run out of dollars.” Or, as Carrillo has provocatively stated elsewhere, “The U.S. government can never run out of money in the same way that the NBA can never run out of points.”

So what does this mean for local budgets? States, cities, and municipalities are not monetarily sovereign in that they do not print their own money and, as monetary subjects, they must get revenue in ways that are legally allowed. This can involve taxes, fines and fees, municipal bonds, philanthropy, and private investment. The federal government, however, is monetarily sovereign, as it can print money. Thus, the federal government can provide funding, whether through the Federal Reserve or Congress. Some have considered how this works in relationship to defunding the police. Eric Levitz notes, “It is not possible to mount a remotely credible response to the recent uprisings over police violence and discrimination while forcing cities to slash spending. . . . Anyone who would like the United States to make meaningful progress on racial justice . . . must call on Congress to cease needlessly starving state governments of funding.” Along with calling on Congress to stop starving us, another demand can be for the democratization of the Federal Reserve, as proposed by Jasson Perez in a recent podcast.

What Levitz and Perez don’t mention is that the federal government can always fund more of everything — including both local policing and social services. Such a possibility could undercut a divest-invest strategy and means we need to make more explicit the political demand to never fund the police, regardless of the budget. What their commentaries do draw our attention to are the layers of public finance that shape the budgets cities have to work with and that are obscured in Ocasio-Cortez’s emphasis on budget priorities among affluent, white suburbanites. They also help us move beyond the taxpayer frame, which is useful since putting the taxpayer in the driver’s seat could always backfire as a divest-invest strategy. After all, those with more power and money may decide they are willing to pay higher taxes to keep policing and may weaponize their identity as “taxpayers” to do so.

While Ocasio-Cortez is familiar with modern monetary theory — which is associated with the finance approach delineated here, in her support for a divest-invest strategy she nevertheless promotes a taxpayer-driven model in which the affluent, white suburbanite serves as the paragon of moral budgeting and social innovation. In the process she obscures how affluent, white suburbanites are the beneficiaries of a racist-classist financial infrastructure whose operations remain relatively underexamined by the general public.

Abolition as the privatization of accountability Ocasio-Cortez’s suburb model posits that when crime and harmful activities happen in affluent, white suburbs, residents are committed to using different means than the police, courts, or incarceration to deal with them. On a surface level, this aligns with a basic goal of abolitionists: to address harms in ways that do not involve criminalization or captivity.

But abolition is not just the absence of policing or captivity; it is also about creating different models of accountability and harm reduction. It is about recognizing the social and political construction of crime as well as the violence and futility of captivity for trying to make us safe, while also attending to the reality that people can and do engage in harmful and violent behaviors that need to be socially addressed. Abolition, then, involves figuring out what nonpunitive accountability looks like in public.

Affluent, white suburbs are not where we should look for models of accountability. Yet this is where Ocasio-Cortez directs our attention.

In her Instagram response, Ocasio-Cortez writes, “When a teenager or preteen does something harmful in a suburb (I say teen bc this is often where lifelong carceral cycles begin for Black and Brown communities), White communities bend over backwards to find alternatives to incarceration for their loved ones to ‘protect their future,’ like community service or rehab or restorative measures.”

We can consider how Ocasio-Cortez’s narrative of white communities “bending over backwards to find alternatives to incarceration” is consistent with her image of affluent, white suburbanites being presumably more committed to other budget priorities. Also questionable is her suggestion that not being policed is a matter of self-design as opposed to not being targeted. According to her, “affluent White suburbs also design their own lives so that they walk through the world without having much interruption or interaction with police at all aside from community events and speeding tickets (and many of these communities try to reduce those, too!).”

If anything, what Ocasio-Cortez is actually describing is the way that affluence and whiteness provide these communities the means to avoid consistent targeting by the police, to ignore laws, or to evade punishment. To be able to be the target of less policing, as well as to hire attorneys and use money and networks when accused, is a thing that white affluence provides — an affluence tied up in and made possible by the racist-classist financial infrastructure concealed by the suggestion that affluent, white suburbanites just have different budgeting priorities. In cases where harm might be perpetrated, using one’s resources in terms of money and connections to avoid criminalization and incarceration can be more an evasion of accountability than abolition.

If, as Angela Y. Davis reminds us, we as a society avoid dealing with the structural dimensions of harm, when it is committed, by disappearing perpetrators in prisons, the other side of the coin is this privatization of accountability available to elites. There are notable differences, of course, as captivity in a cage is a much different and vicious form of being tucked away from public view. I would never confuse captivity with the privacy, money, and racial status shielding an affluent, white suburbanite. But a shared dimension is that each approach tries to make people, when they have committed harm, be disappeared from public view and consciousness while the structural roots of harm go unaddressed and society operates as normal. Again, abolition involves figuring out what nonpunitive accountability looks like in public. Affluent, white suburbanites being shielded from the violence of carceral systems while others are not offered the same opportunity is not a model of abolition. It is just an expression of relative power and racism.” - Tamara K. Nopper, “Abolition is Not a Suburb.” The New Inquiry. July 16, 2020.

#abolitionism#police abolition#prison abolition#suburbs#suburbia#affluent whites#class and crime#housing#alexandria ocasio-cortez#crime control#social control#middle class ideology#middle class#middle class reformers#crime and punishment

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kenyon Farrow, Earl Fowlkes, Carmen Vasquez & More To Lead "In My Mind" Conference For LGBTQ Mental Health Awareness

Kenyon Farrow, Earl Fowlkes, Carmen Vasquez & More To Lead “In My Mind” Conference For LGBTQ Mental Health Awareness

On October 5 and 6 in New York, NY, LGBTQ leaders of color in the physical health, mental health and community industries will speaks to members of the community in various panels regarding mental health awareness to LGBTQ people of color at the In My Mind conference.

Coordinated by the founder of the Depressed Black Gay Men organization, Antoine Craigwell, In My Mind conference brings Earl…

View On WordPress

#Antoine Craigwell#Carmen Vasquez#Depressed Black Gay Men#Earl Fowlkes#Hansel Arroyo#In My Mind conference#James McKnight#Jeffery Gardere#Johanne Morne#Kenyon Farrow#Kraig Pannel#New York State AIDS Institute#Ritchie Torres#Treatment Action Group

0 notes

Text

Chromat Debuts Swimwear For Girls Who Don’t Tuck At Jacob Riis, NYC’s Queerest Beach

“I’ve been going to Jacob Riis Beach ever since my friend, Kenyon Farrow, a Black, queer activist, brought me there in 2005,” said activist and filmmaker Tourmaline of “The People’s Beach” of New York City, located on the other side of Jamaica Bay from Brooklyn, the preferred summertime destination for queer, trans, gender-nonconforming New Yorkers looking to get their tan on. For lots of Riis regulars, that spit of shore is something special: “I can remember a time that I felt so uncomfortable being at the beach and not wanting to be looked at,” Tourmaline said. “I can remember being in the water and not wanting to get out because I was afraid of getting dirty looks. I wasn’t feeling sexy and powerful, so I would be in the water way past a point where I should have been.” For Tourmaline, Riis was instrumental in changing her mindset.

“I can remember a time that I felt so uncomfortable being at the beach and not wanting to be looked at. I can remember being in the water and not wanting to get out because I was afraid of getting dirty looks. I wasn’t feeling sexy and powerful, so I would be in the water way past a point where I should have been.”

Tourmaline, filmmaker and activist

On Sunday, the filmmaker-designer presented a collection of swimsuits and beachwear for girls who don’t tuck, trans femmes, non-binary people, and intersex bodies, a collaboration with beloved swimwear brand Chromat. Founded by designer Becca McCharen-Tran in 2008, Chromat is known for its dedication to inclusivity. The spring ‘22 collection only expanded on that commitment.

“There isn’t a collection that aestheticises the beauty of trans girls and trans femmes not tucking,” Tourmaline told Refinery29 ahead of the New York Fashion Week show. “And there isn’t a collection that does that with package support for trans men who want to pack.” In creating this collection with McCharen-Tran for Chromat, the duo is bringing fashion to a whole new place.

To do so, Tourmaline and McCharen-Tran went through nearly every suit in the Chromat archives, going back over ten years and asking themselves a series of questions about each one: Does this work for you? Is this comfortable? If not, what would you change about it? Some suits, they discovered, were perfect as is, likely because McCharen-Tran has always tried to design beachwear that’s wearable by many. Others needed slight adjustments, like an additional inch of fabric in the crotch area for added support or room. “So there are new pieces and then there are essentially upcycled pieces,” said McCharen-Tran.

”I see this collection as the beginning of something bigger.”

Becca McCharen-Tran, founder of Chromat

Highlights from the collection, which was meant to embrace what Chromat calls Collective Opulence Celebrating Kindred, or “COCK”, include thongs with extra string that goes around the hip, shorts that are low-cut on the leg opening, a tennis skort, a netted micro mini dress, a thong monokini, and a string bikini that’s available in both a narrow and a wide version, among countless other pieces. Every single item in the spring collection is available in sizes XS to 4X. “I see this collection as the beginning of something bigger,” said McCharen-Tran, whose mission is to improve Chromat and expand its reach with each new collection.

NEW YORK, NEW YORK – SEPTEMBER 12: Chromat x Tourmaline Spring/Summer 2022 runway show at New York Fashion Week: The Shows on September 12, 2021 in New York City. (Photo by Shannon Finney/Getty Images for Chromat)

In the democratic spirit of Jacob Riis, the collection was presented in a pop-up format that allowed beachgoers — Chromat’s actual customers — to be the audience, as opposed to New York Fashion Week’s standard crowd. (According to McCharen-Tran, Riis is where she’s seen the most Chromat suits in the wild.) There was no announcement, or anything to notify people that a show was to take place on the beach’s boardwalk. And yet, after the first model, Joshua Allen, descended down the concrete runway, the crowd more than tripled, with cheers coming from every direction.

NEW YORK, NEW YORK – SEPTEMBER 12: A model walks the runway during the Chromat x Tourmaline Spring/Summer 2022 Runway Show at New York Fashion Week on September 12, 2021 in New York City. (Photo by Shannon Finney/Getty Images for Chromat)

NEW YORK, NEW YORK – SEPTEMBER 12: A model walks the runway during the Chromat x Tourmaline Spring/Summer 2022 Runway Show at New York Fashion Week on September 12, 2021 in New York City. (Photo by Shannon Finney/Getty Images for Chromat)

Immediately following the finale, led by Tourmaline and McCharen-Tran, the models took to the beach, throwing themselves on a bed of pink towels before running toward the water. This time, decked out in Chromat’s spring ‘21 collection, there wasn’t a glint of fear about entering the water in a swimsuit, such was the case with Tourmaline years ago. “I think this is such a powerful way to know how important fashion is,” she said.

Freelance writer Jess Sims, who watched the show live from the boardwalk, agrees with Tourmaline. “We say the word ‘inclusivity’ and a lot of fashion doesn’t take it seriously,” she told Refinery29 after the show wrapped. “Chromat has been massively inclusive for over a decade now, and once again, has found a way to include another community in fashion — and fashion should be for everyone.”

McCharen-Tran is steadfast in her quest to turn that “should” into “is.” But even she acknowledges that her work isn’t perfect yet. Despite fit-testing every suit on Tourmaline, who provided detailed feedback for the designer, McCharen-Tran explained that she can’t say for certain that every single person will find a suit in the spring ‘22 collection that’s a perfect fit. Not yet anyway. “But that is always our goal,” she said.

Like what you see? How about some more R29 goodness, right here?

H&M’s Summer 2021 Collection Has The Best Swimwear

Chromat’s NYFW Film Sends An Important Message

The Olympics Ban On Afro Swim Caps Is Outrageous

Chromat Debuts Swimwear For Girls Who Don’t Tuck At Jacob Riis, NYC’s Queerest Beach published first on https://mariakistler.tumblr.com/

0 notes

Photo

Don't miss our #WorldAIDSDay Facebook Live Friday, December 1st at Noon EST/9a PST with Kenyon Farrow, Guy Anthony, Kia LaBeija, and Zachary Barnett.

Have a question? Comment on our Facebook/Instagram post with yours and it might end up on tomorrow's FB Live! http://www.facebook.com/logo

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Brief History of the Erasure of Hip-Hop, Rock N Roll and Black Music Through Anti-Blackness

This is a response to an Anonymous comment. I’m glad to see other black people noticing that we are losing Hip Hop music and culture to non-black people just like we did with Rock & Roll. For those who don’t know, when black people started Rock & Roll, white people did everything they can to block it’s radio play and success to ruin black artists and the music genre as a whole. They used to also categorize the music as negative and uncivilized, sounds familiar doesn’t it? That’s what plenty of them say about Hip Hop as well. The thing is, deep down a lot of white people enjoyed the music and it actually played a part in the civil rights movement because black people along with some white people were rallying for it to play on the radio and for the concerts to not be racially segregated (See Ray Charles, James Brown). But here’s some other deep things to know about it: 1) As a way to appease white listeners who wanted to hear Rock & Roll on the radio, music companies would use white singers to sing over the original songs by black artists and that would be the version played on the radio (See Little Richard’s Tutti Frutti, + his thoughts on Pat Boone doing it over w/ success). 2) Black artists had no say over white people doing over their songs. 3) White artists got paid way more than these black artists, even when most of them played a key role in writing and producing their own music. 4) This led to white artists getting the acclaim, praise, attention and credit for a genre that wasn’t even there’s. Keep in mind that Elvis Presley is regarded as “The King of Rock N Roll” when he himself was inspired by black music/artists and plenty before him made the genre what is today. All of this led to black people losing Rock & Roll and many white people will claim older white rockers as the “innovators and pioneers” of a genre created by black people. Many today also don’t know it was created by black people (Which says A LOT). But over time black artists themselves gave up on the genre which is just sad; they allowed white artists to knock them out under the guise of “it’s just music”. This is why Jimi Hendrix got the praise he did, because he was literally one of the last black rockers and made such an impact in a short mainstream career that lasted for only 4 years. Well today the same is happening with Hip-Hop. Too many black people are welcoming non-black people with open arms to a genre that has been inspired by our pain and struggle. Today many non-black people have no problem stripping and re-telling the history of Hip Hop, and they do it by stripping it’s blackness. (See Ben Baller, See “We Real Cool?: On Hip Hop, Asian-Americans, Black Folks, and Appropriation” By Kenyon Farrow c.2004) <— a piece of this was reblogged here btw*. Also never forget how when Eminem stepped on the scene, white people went out of their way to claim Eminem as “the Greatest Rapper Alive” even when a lot of them didn’t even care to listen to the majority of rappers, whom are black, simply because they are black. They also like to claim we only rap about sex, drugs and violence (to discredit us) when many non-black rappers do the same (See anti-black K-Pop/K-Hip Hop fans :) … The reason why this is so important to me and SHOULD be important to ALL of us who are BLACK (even if you don’t like Hip Hop) is for the fact that everything we do, own, and create is never respected. Everything we have never belong to us, and white people AND non-black POC have no problem reiterating that to us. Everything we create is hit with “It’s for everyone.” Our culture has become a universal grab all. That’s why the appropriation of black culture is treated as a joke while appropriation of other cultures is taken much more seriously. To make matters worse, these are the same people who hate us and do all they can to maintain a false sense of superiority over black people all while taking from us. It’s to push this idea that Non-black people can do everything we do and “better”… With that being said other groups are starting to claim they either “Created”, “Innovated” or “Pioneered” Hip Hop & Rap. (See Ben Baller, again). It’s at the point where I feel like they can actually go and claim such ignorance because many will co-sign the erasure of black peoples’ creations… Including cooning ass black people.. For the love of God I wish they wouldn’t speak. For example, I Saw a Greek dude on YT try to claim Greeks created rap… Got in an argument with a Mexican dude who tried to claim that Mexicans did rap before black people and we “stole” the credit because we speak English… Got into an argument with an Asian dude over black appropriation, our naturally kinky or “nappy” hair and the N word… I am begging my fellow black people to wake up! I am a 21 year old woman who loves my culture and blackness and I REFUSE to allow this nonsense! Stop begging for the acceptance of non-black people by way of erasing your own! Know your history, don’t allow them to rewrite it for you.

595 notes

·

View notes

Text

0 notes

Link

These six videos explore how the NPIC affects activism, from how we work to who leads, and feature interviews with Christine Ahn, Trishala Deb, Kenyon Farrow, Reina Gossett, Shira Hassan, Paulina Helm-Hernandez, Imani Henry, Amber Hollibaugh, N’Tanya Lee, Andrea Ritchie, Dean Spade, Urvashi Vaid, Jason Walker, and Craig Willse.

0 notes

Text

AIDS Drug Assistance Programs Must Navigate Costs and Needs of People With HIV

AIDS Drug Assistance Programs Must Navigate Costs and Needs of People With HIV

[ad_1]

Josh Robbins at the ADAP Advocacy Association’s 11th annual conference (Credit: Kenyon Farrow)

The ADAP Advocacy Association hosted its annual conference in late September, and it covered many subject areas along this year’s official theme, “Mapping a New Course to Protect the Public Health Safety Net.” The AIDS Drug Assistance Program, which was first established by Congressto…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

Won't You Celebrate With Us? I'm so excited to announce our 2nd Annual Scholarship Gala. Join us as we honor Kenyon Farrow, Twiggy ThaOracle and Hari Ziyad! We want attendees to come out in their best formal wear, but keep it funky in sneakers. Purchase tickets below! blackgiftedwhole.org/gala2017

0 notes