#katsinam

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Koshare (Koshari) Koshare, or clowns, are not Katsinam, hut they play an important role in #Pueblo society and ceremonies. During dances, the koshare show unacceptable behavior to Pueblo children, stealing, interrupting, and messing around

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Native American Hopi Made Eagle Katsinam Dancer Overlay Cuff by Bennett Kagenveama

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Native American Gourd Rattles

Native American artisans have long utilized gourds to make many items, including utensils, serving bowls and rattles. The gourd rattle represents the three kingdoms in Native American culture, with the animal kingdom represented by feathers, the mineral kingdom represented by rocks inside the rattle, and the plant kingdom represented by the gourd itself. Music, many Native people believe, is a vessel used to transform ourselves into spiritual beings capable of healing ourselves and others through the transfer of energy, and these rattles are commonly used during ceremonies of song and dance. The following are some examples of gourd rattles crafted by Native Americans:

The Kachina Rattle

The gourd rattle used by the Hopi Katsinam (spirit messengers) is highly symbolic. Often only painted light blue with little decoration, this special instrument is used in Kachina dance and ceremony, and also as a gift given to children during their initiation ceremonies into the Kachina Society. The rattle is constructed of a flattened gourd, which represents the earth, and the handle represents the axis of the Hero Twins, iconic figures of ancient Hopi lore who help keep the earth spinning.

The Peyote Rattle

The Peyote rattle (pictured above) was frequently used during Native American church ceremonies, and was an important element of the Half Moon ceremony. A community elder is in charge of leading this ceremony, which involves the ingestion of dried peyote, a hallucinogenic cactus that was believed to induce visions. This rattle was also constructed from a spherical gourd shape and filled with nut or seed.

The Iroquois Rattle

According to the Iroquois or "people of the longhouse," the gourd rattle is the sound of Creation. The Iroquoian creation stories tell of the first sound, a shimmering sound, which went out in all directions; this was the sound of "the Creator's thoughts." The seeds of the gourd rattle embody the voice of the Creator, since they are the source of newly created life. The seeds within the rattle scatter the illusions of the conscious mind, planting seeds of pure and clear mind.

The Shaman's Rattle

The shaman's rattle is used to invoke the assistance of power animals and helping spirits. It is also possible to direct energy with rattles, much like a magician with a magic wand. Healing energy can be mentally transmitted through the rattle and out into the environment or into a patient's body. Prayer and intention can be broadcast to the spirit world. Moreover, you can create sacred space by describing a circle with the rattle while shaking it.

#gourd rattles#native americans#shamanism#musical instruments#shakers#ceremonial rattle#sound healing

35 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Katsinam, Yuwejiva, c. 1970, Minneapolis Institute of Art: Art of Africa and the Americas

carved, painted figure, leaning slightly forward with PL foot slightly raised and an object in each hand (flat, round green object on stick in PR hand; longer stick with 2 brown/red attachments tied on in PL); green face with brown slit eyes, a red post nose, and two red ears sticking out; three feathers lie on top of head, and two stick up in back from a small headpiece on back; green, white, and red stripes circle top of head; green neck piece; green arm bands and bracelets; brown sash over collared white shirt; tan skirt with brown, red and green pattern on PR side, gray animal with red eyes on backside, and long, tan and brown attachment on PL side; green boots with red trim; figure standing on wood round with knot/branch stub on back side Katsinam are figures that are individually carved from cottonwood roots and then painted. Each katsina is associated with important cosmological figures in Hopi thought, who can manifest themselves and interact with Hopi people through a variety of material forms and at many different levels. Katsinam appear at particular times of the year in Hopi land, and carved katsinam can be used as pedagogical tools and for wider distribution. These particular katsinam include representations of the “Sunface Katsina,” Tanakwewe (“turtle kachina”), a “women katsina,” and an unidentified katsina. Each were created for circulation beyond Hopi land. Size: 9 1/4 × 4 × 4 1/2 in. (23.5 × 10.16 × 11.43 cm) (overall) Medium: Wood, paint

https://collections.artsmia.org/art/137018/

95 notes

·

View notes

Text

it is not that tawa is a brother of the pueblo, it is just a caring way of calling the pueblo, he sees pueblo as a little brother. ╰(*°▽°*)╯💕❤

who is tawa?

Tawa, the Sun Kachina, is representative of the spirit of the Sun, or Sun God. Tawa carries a bell in his right hand and spruce tree in his left hand.

From the Field Private Collection, Turquoise Spirit Journey, this Tawa wears a magnificent headdress of feathers that encircle his colorful, round masked face. The mask has a blue bottom half and top half of the mask is vertically split in orange and yellow halves. The mouth is in a black triangular shape and horizontal slits for eyes. These colors are repeated throughout the Tawa kachina costume. The white kilt-like garment accented by a brown sash moves in rhythm during his dance.

Tawa Aided in Creating Earth

Tawa is accredited with the Earth’s creation and thereby highly revered by the Hopi. Tawa and Kokyanwuhti, the Earth Goddess, created the Earth. Tawa and Kokyanwuhti possess powers over the realms surrounding Earth. These spiritual entities were powerful representatives of how we, the Earth, the Sun and all other creatures came to be.

Beauty of Tawa

The artist of this Tawa, Sun Kachina is unknown, as the information has faded from the bottom of the base. This small kachina doll is completely carved in wood, in very fine detail, front and back, with beautiful colors and possibly carved from cottonwood. There is nice aesthetics with movement of the arms and right leg as though dancing in ceremony.

This kachina is 13.5 cm (5.5 in) in height, standing on a 3-3.5 cm base, total 17 cm height, a little over 6.5 inches. A bit of paint restoration may be desired on the mask. Otherwise, the kachina is in excellent condition.

Makings of a Special Kachina Doll

Detail, beautiful color, materials and movement, as if in dance, of a kachina doll is always highly prized.

Three Aspects of a Kachina For the Hopi, a Kachina has three aspects; the supernatural being, the masked Hopi dancer and the dolls. Each Kachina has a purpose. The supernatural being is the spirit of the Hopi. The Hopi dancers wear the masks and decorations of the supernatural spirits in the Hopi Plaza. The dolls are the teaching tools made in the likeness of the dancers of the supernatural spirit.Forces of Nature Kachinas represent the forces of nature, human, animal, plant, and act as intermediaries between the world of humans and the gods. Kachinas play an important part in the seasonal ceremonies of the Hopi. They represent generations of traditions that have been passed on and are the subject of a number of books.

Small kachina dolls, called tihu in Hopi, are given to children to introduce the child to what each of the kachinas look like. The dolls are carved representations of the katsinam, the spirits essences of their ancestors, animals, plants, nature, all that is within the Hopi universe.Traditionally, kachina dolls are created by Hopi or Zuni artists, and sometimes by the Navajo.You will see a variety of spellings for Kachina, also known as Katchinas, Katcinas, Katsinas, Kat’sina. Kachina is typically the English spelling, while Katsina is Hopi.

#tawa#tawa kachina#sun kachina#kachina#pueblo#pueblo the clown#hopi the clown#hopi#drawing#my drawing#drawing cute#my art#art#oc art#oc#ocs#digital art#my digital art#my digital drawing

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Steeler Prayer

A celebratory touchdown dance in carved cottonwood has been quietly occurring at Carnegie Museum of Natural History for more than 22 years. Within the Alcoa Foundation Hall of American Indians, in the quadrant of the exhibition devoted to conveying information about the Hopi and their culture, a nine-inch high figure of a Pittsburgh Steelers player wearing number 53 holds a football aloft in his right hand. The wide-eyed grinning figure is displayed with plenty of colorful company, and its significance is best understood in terms of this carefully assembled cast.

The carved figures, which are properly called tihus, and more frequently referred to as katsinas, represent the benevolent spirit beings who live among the Hopi on three high mesas of northern Arizona for approximately a six-month period each year. An important role for the carvings is the imparting of knowledge and understanding of these beings or katsinam, and the target audiences for these life lessons are the Hopi themselves.

This aspect of limited cultural sharing was explained to museum educators in the months before the exhibition hall opened in 1998 when Hartman Lomawaima, a Hopi consultant, conducted a training session about the carvings. After a 90-minute presentation that included information about how the katsinas displayed in the hall had not been used in sacred ceremonies, he fielded a particularly pertinent question. “When we take students through the hall we won’t have the time you’ve just shared with us,” explained an experienced interpreter. “What can we tell students about these figures in a minute or two?” “That’s easy,’’ replied Hartman, “just tell them they’re three-dimensional prayers.”

A little more information about the black and gold figure can be gleaned from exhibit text. Here the carving is described as PITTSBURGH STEELER CLOWN KOYAALA, the carver identified as Regina Naha, and the creation date listed as 1992. A reputable reference on katsinas describes the word “Koyaala” as referring to clown figures of the village of Hano on First Mesa, and an internet search under the artist’s name reveals that she is from Hano.

For Steeler fans, and perhaps even for the team’s players, coaches, and administrators, there might be small comfort in knowing a “three-dimensional” prayer clad in their team’s uniform resides under the same roof as Tyrannosaurus rex. For fans of the city itself, the story of how the carving came to be on display offers another example of Pittsburgh Pride. In a font smaller than the rest of the display’s text, the figure is noted to be a “gift of Les and Joan Becker.” Deborah Harding, Collection Manager in the museum’s Section of Anthropology, was able to share some information about the couple. “Les and Joan were long-time and valuable volunteers in this section. During a visit to Arizona they spotted the Steeler carving in the shop at The Heard Museum in Phoenix, and bought it for the museum with the approval of the curator directing the hall’s development. According to the story I heard, Les was able to barter for a lower price by arguing that the figure would be displayed where it belonged, in Pittsburgh.”

Patrick McShea works in the Education and Visitor Experience department of Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Help This Scholar Reverse the Erasure of Native Contributions in the Creation of These 20th-Century Murals

https://sciencespies.com/history/help-this-scholar-reverse-the-erasure-of-native-contributions-in-the-creation-of-these-20th-century-murals/

Help This Scholar Reverse the Erasure of Native Contributions in the Creation of These 20th-Century Murals

Smithsonian Voices Smithsonian Institution Office of Fellowships and Internships

Reversing the Erasure of Native Contributions to Muralism

October 9th, 2020, 9:00AM / BY

Davida Fernandez-Barkan

Eduard Buk Ulreich, Advance Guard of the West (mural study, New Rockford, North Dakota Post Office), ca. 1939-1940, tempera on fiberboard, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Transfer from the U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1965.18.33

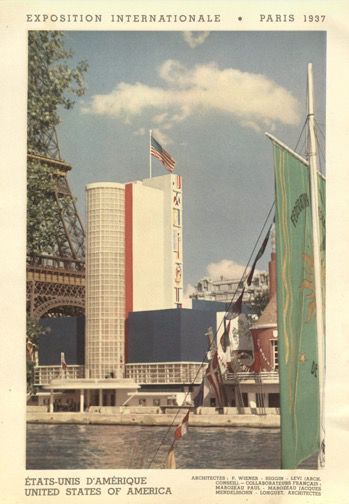

Being an art historian is a little like being a detective. It sometimes takes me to unlikely places—including, recently, a basement outside St. Louis, where the relatives of an artist I was researching for my dissertation generously allowed me to review documents from his life. The artist, Eduard “Buk” Ulreich, had designed a number of publicly funded murals throughout his career; studies for many of them can be found in the collection of the Smithsonian American Art Museum and Renwick Gallery (SAAM). My interest in Ulreich was related to two 88-foot wooden panels inspired by Native American symbols that he conceived for the United States Pavilion at the 1937 World’s Fair in Paris.[1] One document in particular has occupied my thoughts in the months since my visit: a newspaper clipping showing two men shaking hands. The men stand in front of what appears to be Ulreich’s mural Indians Watching Stagecoach in the Distance (1937), which he painted for the post office in Columbia, MO. The man on the left is named in the caption as the 1937 U.S. pavilion’s “chief designer,” Paul Lester Wiener, while the one on the right, appearing in a feathered headdress, is identified simply as, “a Navajo Indian who gave his advice on the vast murals depicting Indian life and thought which are being painted by Buck [sic.] Ulreich for the outside of the skyscraper tower.”[2] My goal, ultimately, is to identify this man. Yet even without declaring this man’s identity, the photograph highlights an oft-overlooked aspect of twentieth-century American art: the essential contributions of Native Americans to the mural movement that overtook the United States in the years between World War I and World War II.

Paul Lester Wiener and an unidentified advisor for the U.S. Pavilion murals, Private archive of Eduard “Buk” Ulreich, St. Louis, MO. (Hans Knopf, Pix, Inc.)

Ulreich was one of the many U.S. artists who received funds to install murals in public buildings in the United States during the 1930s and early 1940s through programs such as the Public Works of Art Project, the Treasury Section of Fine Arts, and the Works Progress Administration. He styled himself as a “Cowboy-Painter,” a claim that lay in part in his avowed knowledge of Native American cultures.[3] The artist was vocal about time he had spent around Native Americans, including as an actual cowboy on a ranch on an Apache reservation in Arizona. He posited that it was this type of exposure that resulted in his selection to paint the exposition murals.[4] Yet as the newspaper clipping indicates, Ulreich required the input of at least one Native advisor to accurately convey the mural’s symbols. A different clipping in Ulreich’s family’s archive identifies a number of the symbols that appear, stacked on top of one another, in the pavilion’s murals. These include a “Kachina”[5] figure popular in Pueblo cultures, a Crow thunderbird, and an adaptation of a deity used in Navajo[6] sand painting.[7] This same clipping indicates that, although Ulreich designed the murals, a “member of the Navajo tribe” actually painted them. This individual, like the man in the photograph, is unnamed in the clippings. Neither appears to be mentioned at all in fair-sponsored publications and they are absent altogether from what limited secondary literature exists about the U.S. pavilion at the 1937 exposition.

The U.S. Pavilion at the 1937 World’s Fair in Paris, pylon murals designed by Eduard “Buk” Ulreich, from Photographies en couleurs: exposition internationale des arts et des techniques appliqués à la vie moderne: album official (Paris: Photolith, 1937)

The 1937 fair was not the first world’s fair to feature murals indebted to Native American labor and knowledge. The 1933 Century of Progress exposition in Chicago had included a series of murals executed by a group of artists associated with the Santa Fe Indian School. Changing perceptions of Native culture, reflected in the work of both Native and non-Native artists alike, were in fact a hallmark of the mural movement in the United States. In addition, one of the movement’s most revolutionary aspects was an increased access to the role of “artist.” Not only men of European descent, but also many women, Native Americans, and other people of color became muralists. Still, artists from these marginalized groups did not receive the same treatment as their white male counterparts. Like the Native participants in the 1937 exposition, the artists who developed the Century of Progress murals are anonymous in fair literature. One administrative document refers to them simply as the “Santa Fe Indians,” while it refers to white artists such as George Biddle and John Norton by name.[8] Thanks to the work of art historians such as Jennifer McLerran, we know the identities of many of the mural artists involved with the Santa Fe Indian School. Several of these are represented in SAAM’s collection, including Julian “Pocano” Martinez, Tse Ye Mu (known alternately as Romando Vigil), Awa Tsireh (known alternately as Alfonso Roybal), Oqwa Pi (known alternately as Abel Sanchez), and Ma Pe Wi (known alternately as Velino Shije Herrera), whose murals can also be found in the Department of the Interior building in Washington, D.C.[9]

To identify the Native individuals who helped create the panels at the 1937 fair would ensure that they are given credit, if belated, for their work. Beyond this, it would be a means of celebrating Native contributions to the mural movement. Native participation in the painting of such monumental, public works of art during this period is little known and seldom discussed, a problem that is compounded when we do not know the names of the individuals who took part. The erasure of nonwhite groups from public life is particularly dangerous, as it has a pernicious history in this country. From attacks on Black communities to anti-immigrant rhetoric, the claim that only white Americans “create,” while others sponge off their productivity, has been one of the most insidious myths shoring up the ideology of white supremacy over the last several centuries.[10]

Searching for the identity of the man in the 1937 photograph is a small way of combatting this myth. It is a way of ensuring that white artists do not receive the only credit for their collaborations with communities of color. I am therefore hoping that anyone who might have information about the man in the photograph or other Native participants in the 1937 exposition will get in touch! With such interventions, perhaps art history can help to make the inclusiveness promised by muralism a reality.

[1] Carlyle Burrows, “A New Project in Modern Decoration: The Stage Coach and the Pony Express,” New York Herald Tribune, August 1, 1937, F6.

[2] Art historian Emily Burns notes that the man’s dress appears to be a composite of clothing from a number of different Native nations. The headdress, for example, is typical of Plains rather than southwestern cultures. It thus constitutes a kind of Native American “intern-nationalism” against the backdrop of the International Exposition. Emily Burns, email message to the author, September 30, 2020.

[3] “With Latin Quarter Folk,” Folder “1926,” Private Archive of Eduard “Buk” Ulreich, St. Louis, MO.

[4] Eduard “Buk” Ulreich, “Eduard Buk Ulreich: A Brief History,” n.d., Folder “Buk Autobiography,” Private Archive of Eduard “Buk” Ulreich, St. Louis, MO; “Story of the Indian Ornament for the American Exposition Building at Paris, France,” n.d., Folder “1937,” Private Archive of Eduard “Buk” Ulreich, St. Louis, MO.

[5] The term “katsina” (plural “katsinam”) is preferred.

[6] Members often prefer the name “Diné” to Navajo.

[7] Francis Smith, “Brilliant Murals Portray Lore of U.S. Indains at Exposition,” Paris Herald, July 27, 1937, Private Archive of Eduard “Buk” Ulreich, St. Louis, MO.

[8] “Interior Painting & Murals,” n.d., Series 15, Box 7, Folder 15-74, Century of Progress World’s Fair, 1933-1934 (University of Illinois at Chicago).

[9] See Jennifer McLerran, A New Deal for Native Art: Indian Arts and Federal Policy, 1933-1943 (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2012), 164.

Davida Fernandez-Barkan is a Ph.D. candidate in History of Art and Architecture at Harvard University and was a Smithsonian Institution Predoctoral Fellow at the Smithsonian American Art Museum during the 2019–20 academic year. She holds an A.B. and M.A. in History of Art and Architecture from Harvard and an M.A. in Curating the Art Museum from The Courtauld Institute of Art. She has worked or interned in curatorial departments at the Harvard Art Museums, the Centre Georges Pompidou, the Institute of Contemporary Art/Boston, the National Gallery of Art, Tate Britain, and the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden. Her work appeared in the most recent issue of the journal Public Art Dialogue. Her dissertation is titled, “Mural Diplomacy: Mexico, the United States, and France at the 1937 International Exposition in Paris.” She is currently a Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts (CASVA) David E. Finley Fellow (2020–23).

More From This Author »

#History

1 note

·

View note

Photo

five Hopi carved and painted cottonwood root Katsina Dolls

to instruct young girls and new brides about katsinas or katsinam, the immortal beings that bring rain, control other aspects of the natural world and society, and act as messengers between humans and the spirit world.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Hopi Kachina Dolls

Thank you Ann Howard and Simone Kincaid, both retired archeologists, for identifying on ButtonBytes forum that this picture is that of Hopi Kachina doll (Google Search). Hopi katsina figures (Hopi language: tithu or katsintithu), also known as kachina dolls, are figures carved, typically from cottonwood root, by Hopi people to instruct young girls and new brides about katsinas or katsinam, the…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

❗✋✊Incredible Kachinas

Kachina Dolls represent katsinam and come from Hopi katsina figures known as tithu or katsintithu in the Hopi language.

Krazy Bear is a Native American owned business that promotes Native American awareness.

Visit Krazy Bear for American Indian home decor, rings, hoodies, totes, and other accessories.

https://krazybear.com/product-category/jewelry/bracelets/

0 notes

Text

Cottonwood Roots has been published on Elaine Webster - http://elainewebster.com/cottonwood-roots/

New Post has been published on http://elainewebster.com/cottonwood-roots/

Cottonwood Roots

The nomad lifestyle has its appeal—never staying in one place too long to become attached. Non-attachment is the source of many spiritual and religious disciplines. Learn what you need to learn, do what you need to do and move on—hopefully with some acquired growth and knowledge. At some point, however, there’s a return to home—sometimes a home you’ve never been; at least not in this lifetime. That’s where I’m at, wondering how to best use this time—the final quarter.

I’ve been drawn to Native American culture since childhood—growing up in New York City, I had my eye on the ground—mostly concrete and blacktop with the occasional grassy park where I found what I was sure to be “Indian Paths”. I spent countless hours at the Museum of Natural History seeking solitude amongst the dioramas and Native American village displays; progressing to the Amazon Rain Forest and the jungle sounds brought alive over speakers when a certain button was pushed. That’s what the east coast means for me—a place to leave for adventure—go west youngster. So, I did, as I had (I believe) in some previous life.

So, what. So, this. There is something happening on the Colorado Plateau, a desert region roughly centered at the Four Corners region of the southwestern United States. Of equal significance are the low deserts that extend to the Mexican border. Geographically, earth upheavals are apparent in every canyon, mesa, desert, and forest. Change has happened here, and it will again. No surprises, except that as the Hopi believe, this area, as it relates to our planet, is the center of the universe. Which is what draws me to the three Hopi mesas and their (almost) secret society of spirit guides.

A Kachina, or more appropriately, a Katsina is a doll of sorts, carved from the roots of the cottonwood tree. As I am in learning mode, I suggest for full explanations and better understanding that you read the many books and articles on the subject. My goal here is to show off (surprise!) what has come to me and is relevant in my home (as protection), my life and spiritual growth. I have so much more to share; most of which will have to wait for future blog posts.

Here is the gang (which came together from different carvers and sources) as they stand guard above the mantel. At the center are a male (Sa’lakwtaga) and female (Sa’lakwmana) pair of what were described to me as Monsoon deities. The feathers represent the rain and those can only be lightning protruding from their heads. Water, as for most peoples, is of paramount importance to the Hopi. The figures bring healing and cleansing to our home. To the viewer’s right is a young warrior with a snarky smile carved by a young carver, Brendon Kayquoptewa, who credits his father, Robert Kayquoptewa and older brother, Samuel as the early influences in his carving. I was drawn to this piece because of his youthful approach to life’s battles. On the left, the snake dancer, is not so much a spirit, but a participant in the Snake Clan’s ceremonial dances. I take snakes as my personal totem. I have maximum respect for their ability to strike, yet they prefer to avoid unnecessary confrontation. I also find them uniquely beautiful. Those of you afraid of snakes, probably wouldn’t like me much either.

Finally, on both ends are two cradle dolls carved by two different artists Paul Tso (simple style) and Myron Begoshwytewa (with braids). They are both Grandmother Katsina (Hahai-i wu-uti) or Happy Mother who shares with Crow Mother the title of Mother of all the Katsinam. Her husband is said to be Eototo and her children are the monsters, the Nataskas. She appears during the Bean Dance (Powamuya), the Serpent Ceremony and at Home Going (Niman). She speaks in a high voice and is very talkative. Flat carvings of the Grandmother Katsina are given to Hopi infants. As a young girl matures, she receives larger, more detailed forms of the Grandmother Katsina. I relate to these two as my soul in its infancy waiting to bloom.

0 notes

Photo

Katsina

Commodified and Appropriated Images of Hopi Supernaturals

Zena Pearlstone

UCLA Fowler Museum, Los Angeles 2001, 200 pages, ISBN 9780930741839

euro 14,50*

email if you want to buy :[email protected]

This volume chronicles the commodification of the Hopi Katsinam (plural of Katsina or Kachina) over the last 150 years. Once known only to the Pueblo peoples of the Southwest, these carvings have been transformed into international symbols and are now found decorating designer scarves, T-shirts, coasters, and a host of other products. In the course of this heavily illustrated study, the authors confront the consequences of inter- and intracultural perception, definitions of sacred and secular, colonialist thought and postcolonial retort. Also included are short statements by thirteen contemporary artists actively carving Katsinam or representing them in their work.

orders to: [email protected]

twitter: @fashionbooksmi

flickr: fashionbooksmilano

instagram: fashionbooksmilano

tumblr: fashionbooksmilano

0 notes

Link

#mudhead#Toson Koyemsi#antique#native american#Hopi#carving#carved#Arthur Holmes Sr#katsina#katsinas#doll

0 notes

Photo

Katsinam, H. Nequatewa, c. 1970, Minneapolis Institute of Art: Art of Africa and the Americas

carved, painted figure, leaning slightly forward with PL foot raised slightly and an object in each hand (flat, round object on stick in PR hand; longer stick with flower in PL); teal, red, orange, and black round face with rectangular eyes and triangular nose, circle of black-tipped feathers lining edge of face; smaller bunch of feathers (or petals) on top of head; teal necklace, red sash over chest; orange skirt with colored pattern at front, red belt, and tail down backside; ties at knees over orange PL leg and teal PR leg; brown boots with red, blue and green pattern; figure standing on wood round Katsinam are figures that are individually carved from cottonwood roots and then painted. Each katsina is associated with important cosmological figures in Hopi thought, who can manifest themselves and interact with Hopi people through a variety of material forms and at many different levels. Katsinam appear at particular times of the year in Hopi land, and carved katsinam can be used as pedagogical tools and for wider distribution. These particular katsinam include representations of the “Sunface Katsina,” Tanakwewe (“turtle kachina”), a “women katsina,” and an unidentified katsina. Each were created for circulation beyond Hopi land. Size: 12 × 5 × 5 1/4 in. (30.48 × 12.7 × 13.34 cm) (overall) Medium: Wood, paint

https://collections.artsmia.org/art/137015/

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

first who is pueblo / hopi ?: The Pueblo clowns (sometimes called sacred clowns) are jesters or tricksters in the Kachina religion (practiced by the Pueblo natives of the southwestern United States). It is a generic term, as there are a number of these figures in the ritual practice of the Pueblo people. Each has a unique role; belonging to separate Kivas (secret societies or confraternities) and each has a name that differs from one mesa or pueblo to another.The clowns perform during the spring and summer fertility rites.Hopi clowns from the various mesa villages perform in plaza while Kachina Dancers are taking a break, drawn by Neil David Sr.Among the Hopi there are five figures who serve as clowns: the Payakyamu; the Koshare (or Koyaala or Hano clown); the Tsuku; the Tatsiqto (or Koyemsi or Mudhead); and the Kwikwilyak.[1] With the exception of the Koshare, each is a katsinam (personification of a spirit). It is believed that when a member of a kiva dons the mask of a katsinam, he abandons his personality and becomes possessed by that spirit.In order for a clown to perform meaningful social commentary via humor, the clown's identity must usually be concealed. The sacred clowns of the Pueblo people, however, do not employ masks but rely on body paint and head dresses. Among the best known orders of the sacred Pueblo clown is the Chiffoneti (called Payakyamu in Hopi, Kossa in the Tewa language, Koshare among the Keres people, Tabösh at Jemez, New Mexico, and Newekwe by the Zuñi). These individuals present themselves with black and white horizontal stripes painted on their bodies and faces, paint black circles around the mouth and eyes, and part their hair in the center and bind it in two bunches which stand upright on each side of the head and are trimmed with corn husks.[2]The mudheads (called Koyemshi in Zuni, and Tatsuki in Hopi) are usually portrayed by pinkish clay coated bodies and matching cotton bag worn over the head.[3]Anthropologists, most notably Adolf Bandelier in his 1890 book, The Delight Makers, and Elsie Clews Parsons in her Pueblo Indian Religion, have extensively studied the meaning of the Pueblo clowns and clown society in general. Bandelier notes that the Tsuku were somewhat feared by the Hopi as the source of public criticism and censure of non-Hopi like behavior. Their function can help defuse community tensions by providing their own humorous interpretation of the tribe's popular culture, by reinforcing taboos, and by communicating traditions. A 1656 case of a young Hopi man impersonating the resident Franciscan priest at Awatovi is thought to be a historic instance of Pueblo clowning.

Pueblo Clowns (sometimes called sacred clowns) is a generic term for jester or trickster in the Kachina religion practiced by the Pueblo Indians of the southwestern USA. There are a number of figures in the ritual practice of the Pueblo people. Each has a unique role and belongs to separate Kivas (secret societies or confraternities), and each has a name that differs from one mesa or pueblo to another.

They perform during the spring and summer fertility rites. Among the Hopi there are five figures who serve as clowns: the Payakyamu, the Koshare (or Koyaala or Hano Clown), the Tsuku, the Tatsiqto (or Koyemshi or Mudhead) and the Kwikwilyak. With the exception of the Koshare, each is a kachinam or personification of a spirit. It is believed that when a member of a kiva dons the mask of a kachinam, he abandons his personality and becomes possessed by the spirit. Each figure performs a set role within the religious ceremonies; often their behavior is comic, lewd, scatological, eccentric and alarming. Among the Zuni, to enter the Ne'wekwe order, one is initiated "by a ritual of filth-eating"; "mud and excrement are smeared on the body for the clown performance, and parts of the performance may consist of sporting with excreta, smearing and daubing it, or drinking urine and pouring it on one another".

Anthropologists, most notably Adolf Bandelier in his 1890 book The Delight Makers, and Elsie Clews Parsons’s Pueblo Indian Religion, have extensively studied the meaning of the Pueblo Clowns. Bandelier notes that the Tsuku were somewhat feared by the Hopi as the source of public criticism and censure of un-Hopi like behavior. Their function can also include defusing community tensions, providing their own humorous interpretation of popular culture, re-enforcing taboo and communicating tradition.

about mine: he is nice and does the opposite, sometimes annoying some and loves being in kind, and those things on his head are strange XD horns and he is neither bad nor good. likes: doing clowning, being against, babywise, etc. dislikes: doing what everyone else does, wind, boredom etc.💖\( ̄︶ ̄*\))✨

#pueblo#hopi#pueblo clown#hopi clown#clown art#clown drawing#clown digital art#my art#art#cute art#cute#drawing cute#love drawing#my drawimg#drawing#my drawing#pueblo the clown#hopi the clown#art digital#digital art#digital#my oc digital#my oc#my oc art#ocs#world clown#my ocs#oc clown

21 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Heoto Mana by Alan Cruz. #hopi #heotomana #katsinam #katchina #carving #cottonwood #root #sage #art #mesas #jasonclaydunn

2 notes

·

View notes