#kamala thiagarajan

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

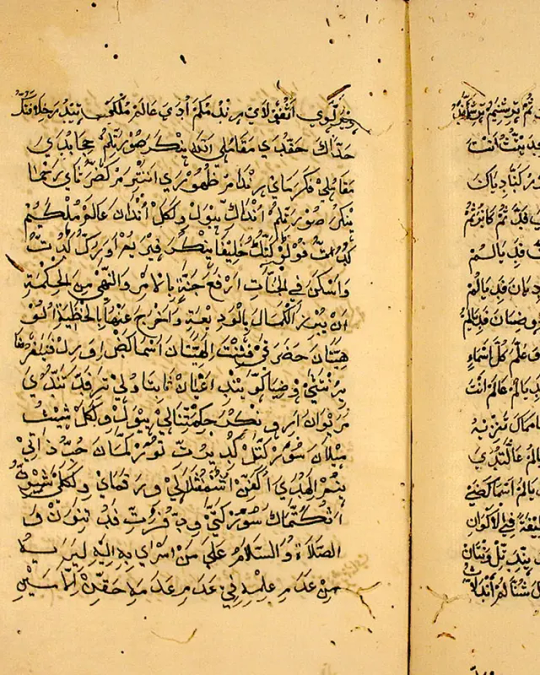

Arwi dates to the 8th Century CE when travel and trade in the medieval world sparked a curious intermingling of tongues. It leapt to prominence in the 17th Century, when more Muslim Arab traders landed in the South Indian state of Tamil Nadu, which was full of Tamil speaking people. The traders brought with them rich tapestries and the finest textiles and perfumes like frankincense and myrrh–records say they longed to establish a deeper connection with the local people because they felt connected by a common religion but spoke two different languages.

The Arabic that the traders spoke intermingled with the local language of Tamil to create what scholars call Arabu Tamil, or Arwi. The script employs a modified alphabet of Arabic, but the actual words and their meanings are borrowed from the local Tamil dialect.

—Kamala Thiagarajan, Arwi: The lost language of the Arab-Tamils, BBC Travel

4 notes

·

View notes

Quote

"Leprosy remains a deep-rooted human rights issue," says Alice Cruz, the UN Special Rapporteur on the elimination of discrimination against persons affected by leprosy, a role she's held since November 2017. There are more than a hundred laws that discriminate against people with leprosy worldwide, creating a strong stigma that can act as a barrier for getting treatment, she says. In some countries, leprosy is grounds for divorce. In India, this was the case until laws were amended in 2019. Many people affected by the disease still struggle to get jobs, and the disease can hinder their access to healthcare and education. "Countries should do everything in their power to have discriminatory laws abolished and to put in place policy that can guarantee economic and social rights to people affected by leprosy," says Cruz. "Going forward, we should ask ourselves the question: are our healthcare systems working to afford full accessibility to persons affected by leprosy? This is because leprosy is much more than a disease, it became a label that dehumanises people who are affected by it."

Kamala Thiagarajan, ‘Leprosy: the ancient disease scientists can't solve’, BBC

#BBC#Kamala Thiagarajan#Leprosy#human rights#Alice Cruz#discrimination against persons affected by leprosy#stigma#grounds for divorce#employment opportunities#access to healthcare#access to education#discriminatory laws#economic and social rights#healthcare systems#dehumanisation

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fold paper. Insert lens. This $2 microscope changes how kids see the world

November 24, 20248:50 AM ET

By Kamala Thiagarajan

Eight-year-old S. Hariraj is a Foldscope devotee.

He's used it to look at the milk from the cows his parents raise. Though the milk looks creamy, the Foldscope reveals a world of microorganisms. "It has to be boiled and cooled before we can drink it," he says. "The Foldscope taught me that the world we see around us can be very different than what we assume. It's like having a third eye."

The 8-year-old is talking about a device that is a fully functional paper microscope.

Everything you need to construct the Foldscope comes in a pouch: a sheet of paper with four main parts to punch out to build the microscope. They're waterproof and tear-resistant — it's a similar paper to that used for currency notes.

The main part of the Foldscope is one long sheet of paper. Half of this is blue (that's the front portion) and the other half is yellow (which you fold to become the back of the foldscope). Magnets stick to each end, holding front and back together. There's a lens in the pouch — and a hole to indicate where it should go.

Once assembled the Foldscope is the size of a bookmark. It's small enough to fit in a pocket and can magnify up to 140 times.

Each unit costs around $2 to make. Foldscopes are offered for free to kids in lower income countries; various upgraded models with extras are sold as well, earning money for the charitable endeavor.

The Foldscope is the invention of MacArthur genius grant winner, Manu Prakash, and his colleague Jim Cybulski. It made its debut ten years ago. And as young Hariraj observes, it is a game-changer.

The inspiration came when Prakash, 44, was growing up in the northern Indian city of Meerut. Now an associate professor in the Department of Bioengineering at Stanford University, he recalls an afternoon in Grade 6 when he and his classmates were stumped by a single test question.

"We were asked to draw a microscope," he says. "None of us could because we just hadn't seen one."

much more of this story at the link!

165 notes

·

View notes

Link

Penyakit kusta tetap menjadi misteri, meski sudah diketahui sejak 3.500 tahun lalu, bagaiana awal dan penyebarannya mikrobakteri ini.

0 notes

Text

“The white tiger” is a movie featuring Balram, a poor Indian man who is very ambitious and wants to change his future. Balram was forced to quit school and to work at a very young age in order to help his family. Later in his life he worked as a driver for an Indian rich family. Balram was ready to do anything for his “master”. He was mistreated in the majority of events, but he was looking forward to learning from the younger son of that family, who used to live in the United States. At the end, Balram ended up killing the younger son and running away with a large sum of money to open his own business. He owned taxi driving company and treated his employees the way he wanted to be treated when he was a “servant”.

The movie is a story of a poor man who felt that “servants are nothing without their masters”, he was covering for his boss and his wife that killed a child in an accident. Balram didn’t have another choice, just like the African American population in the south of United States that lived in painful conditions and were working for “masters” who owned the farms. Similar to Balram, the new generation of African Americans moved North during the “Great Migration” in order to look for a better future. they wanted to make a change and refuse to live the same life their parents had. For them at that time, the north is a place of opportunities and a better future.

In the United States, racism in the South was based on racial differences, while in this movie all the characters are from the same race. The racism in the movie was based on social and cultural differences. In some parts of India there is discrimination between religions caused by “the caste system”. Caste-based discrimination was applied to non-Hindus including Christians, Muslims and members of other minority groups. The poor people did not have a chance to finish their education and they were seen acting like “animals”. The wife of the rich son made comments about how Balram smelled and how he was dressed. She also made comments about his behavior and asked him to leave in front of guests. Balram was asking himself “why his dad did not teach him how to brush his teeth and how he can take care of himself”.

Throughout the movie, Balram felt that he belongs to the rich family, even when mistreated he was loyal to them. “"Do we loathe our masters behind a façade of love, or do we love them behind a façade of loathing?", that is what he asked himself. The case of servants like Balram was described by the “rooster coop” metaphor. “The greatest thing to come out of this country ... is the Rooster Coop. The roosters in the coop smell the blood from above. They see the organs of their brothers ... They know they're next. Yet they do not rebel. They do not try to get out of the coop. The very same thing is done with human beings in this country."

The rich wife is of Indian origins, but she lived in the United States, she identified with Balram’s struggle, she did not accept how the rich family was treating their “servant” and she chose to leave her husband, who started accepting the situation, and she left to go back to the United States.

At the end of the movie Balram ha enough from the mistreatment and the abuse of the “masters”. He wanted a change in his life. He ended up killing his master, the son. He stole a large amount of money and left to start his own business which he called “The White Tiger Drivers”.

The movie brought racial, social and cultural racism to discussion while criticizing the servants and masters culture.

Images source:

Thiagarajan, Kamala. “What Indians Who've Known Poverty Think of Netflix's 'The White Tiger' Movie.” NPR, NPR, 29 Jan. 2021, www.npr.org/sections/goatsandsoda/2021/01/29/961620648/what-formerly-poor-indians-think-of-netflixs-the-white-tiger-movie

0 notes

Text

This is a wonderful piece by Kamala Thiagarajan exploring the state of paleontology in India.

Themes to explore:

1. Vaishali Shroff - The Adventures of Padma and a Blue Dinosaur

2. Desi Stones and Bones - Anupama Chandrasekharan

3. Prof. Ashok Sahni

4. Punjab Natural History Museum, Chandigarh

5. Reminded me of this tune from childhood - Chipkali ka Nana - Danasur

#Paleontology#India#Jeffrey A Wilson#Ashok Sahni#Punjab Natural History Museum#Vaishali Shroff#Anupama Chandrasekharan#Desi Stones and Bones

1 note

·

View note

Text

the month that was...

It’s that time of the month again. The time when I reminisce what I did over the past month and what more I could have done. And hoping to do that more in the coming month.

Remember when I wrote a post like this a month ago? You should surely check it out. This one is going to be a lot like that one.

So, let’s backtrack a bit and go through the stuff I did on social media.

Let’s talk about Twitter first. In November 2020, IIJNM called in Kamala Thiagarajan as a guest speaker. So, while listening to her sharing her knowledge, I made a Twitter thread. I did another Twitter thread this month, it was on the Media Shows’ episode on The Economics of Outrage. Apart from these, I tweeted about my news story on the gun violence happening in Chandigarh, Punjab.

This month I put up a callout asking for help for news story ideas on Instagram and Twitter. I even wrote a blog post about my experience with the blunder that was. I also made a bunch of infographics when Elon Musk became the second richest person.

All this I did to fulfill my monthly quota of social media work that my institute requires out of me. But this month, I did something for myself too. I wrote an appreciation post for the gem of a song that Mirrorball by Taylor Swift is.

It’s not much and I have a lot more to do. So I’m hopeful that this last month in this year like 2020 would have more posts from my side making me a bit more confident, one post at a time.

0 notes

Link

By Kamala Thiagarajan

8 March 2019

As an Indian, I’ve always been comfortable with the notion of bare feet. Over the years, I’ve grown accustomed to slipping out of my shoes before stepping into my own home (to not bring germs indoors with me), when I visit friends and family, or during prayers at Hindu temples.

And yet, despite this conditioning, even I was unprepared for Andaman.

View image of The village of Andaman in Tamil Nadu, India, has banned shoes from being worn within its limits (Credit: Credit: Kamala Thiagarajan)

A village in the southern Indian state of Tamil Nadu, Andaman is 450km (and around a 7.5-hour drive) from Tamil Nadu’s capital city of Chennai. Around 130 families live here, many of whom are agricultural labourers who work in the surrounding paddy fields.

You may also be interested in: • The descendants of Alexander the Great? • The Indian tribe that deals in venom • The country that sells wishes

I met 70-year-old Mukhan Arumugam just as he was offering his daily prayers under an enormous neem tree at the entrance to the village. Dressed in a white shirt and a checked lungi (sarong), his face was tilted to the sky. Even in late January, the midday sun was blindingly bright.

It is under this tree, he said, adjacent to the sparkling waters of an underground reservoir and engulfed by lush green paddy fields and rock-strewn roads, that the story that defines his village begins. For this is the exact spot where villagers take off their sandals or shoes and carry them in their hands when they enter the village.

No-one in the village of Andaman, except the very elderly and the infirm, wears shoes, Arumugam told me. He was barefoot himself, even though he says he does intend to wear sandals soon, especially in the hot summer months ahead. As I walked through the village in my thick dark socks, I was astounded by the sight of children and teenagers rushing to school and couples strolling to work, all nonchalantly carrying their shoes in one hand. It was almost like they were another accessory, like a purse or a bag.

View image of People entering Andaman usually remove their shoes at the neem tree that marks the entrance to the village (Credit: Credit: Kamala Thiagarajan)

I stopped 10-year-old Anbu Nithi who whizzed past me on his bicycle in his bare feet. Nithi studies in standard five in a town 5km away, and he grinned when I asked him if he’d ever flouted the barefoot rule of the village. “My mother told me that a powerful goddess called Muthyalamma protects our village and so we don’t wear slippers here out of respect for Her,” he said. “If I wanted to, I could, but that would be like insulting a friend that everyone adores.”

I quickly find that it’s this spirit that sets Andaman apart. No-one enforces the practice. It isn’t a stringent religious code, rather a time-worn tradition that is steeped in love and respect.

“We’re the fourth generation of villagers to live this way,” explained Karuppiah Pandey, a 53-year-old painter. He was carrying his shoes, but his wife, Pechiamma, 40, who works in the fields to harvest rice, says she doesn’t bother with footwear at all except when venturing outside the village. When someone visits the village wearing shoes, they try to explain the rule, she says. But if they don’t comply, it’s never enforced. “It’s purely a personal choice that’s embraced by all who live here,” Pechiamma said. And though she’s never imposed the rule on her four children either – who are now adults and working in nearby cities – they all follow the custom when they come to visit her.

View image of Around 130 families live in Andaman, many of whom work in the surrounding paddy fields (Credit: Credit: Kamala Thiagarajan)

But there was a time when fear propelled this practice.

“Legend has it that a mysterious fever will strike you if you don’t heed the rule,” said Subramaniam Piramban, 43, a house painter who has lived in Andaman all his life. “We don’t live in fear of this prophecy, but we’ve grown accustomed to treating our village like a sacred space – to me, it’s like an extension of a temple,” he said.

We’ve grown accustomed to treating our village like a sacred space

To find out how this the legend evolved, I was directed to the village’s informal historian. Lakshmanan Veerabadra, 62, is a success story of staggering proportions for this little hamlet. Today, he runs a construction company in Dubai, after having travelled overseas as a daily wage labourer nearly four decades ago. He returns to the village often, sometimes to recruit personnel, but mostly to keep in touch with his roots. Seventy years ago, he said, villagers installed the first clay idol of Goddess Muthyalamma under the neem tree on the outskirts of the village. Just as the priest was adorning the goddess with jewellery and people were immersed in prayer, a young man is believed to have walked past the idol with his shoes on. It’s not clear whether this man viewed the ceremony with any degree of scorn, but legend has it he slipped and fell mid-stride. That evening, he was struck with a mysterious fever, and it took him many months to recover.

“Ever since then, the people in the village don’t wear any kind of footwear,” Veerabadra said. “It evolved into a way of life.”

Every five to eight years, during March or April, the village hosts a festival during which a clay idol of Muthyalamma is installed under the neem tree. For three days, the goddess stays to bless the village, before the idol is smashed to pieces and returned to the elements. During the festival, the village is filled with prayer, feasting, pageantry, dance and drama. But because of the huge costs involved, it isn’t an annual affair. The last festival was in 2011, and the next event is uncertain, depending as it does on donations from local patrons.

View image of The practice of not wearing shoes in Andaman is a time-worn tradition that is steeped in love and respect (Credit: Credit: Kamala Thiagarajan)

Many outsiders tend to dismiss the legend at the heart of this village as a kind of odd superstition, says Ramesh Sevagan, 40, a driver. At the very least, he says, the legend has helped carve a strong sense of identity and community. “It has brought us together, made everyone in the village feel like a family,” Sevagan said. This sense of kinship has bred other local customs, too. When someone in the village dies, for instance, regardless of whether the deceased is rich or poor, villagers gift a modest sum – Rs 20 each – to the bereaved family. “Apart from wanting to help our neighbours, to be there for them in good times and in bad, it has made us feel that we’re all equals here,” Sevagan said.

I wonder if time, travel and global exposure can dent this feeling. I asked Dubai-based Veerabadra whether he still feels as strongly about the shoe ban now as he did as a young boy. He says he does. Even today, he goes barefoot in the village and the years away haven’t dampened his enthusiasm for following the legend that lies at the heart of Andaman.

It has made us feel that we’re all equals here

“Regardless of who we are or where we live, all of us wake up every morning believing that we will be well,” he said. “There are no guarantees, but we still go about our day. We make plans for the future; we dream, we think ahead.

“Life everywhere revolves around such simple faith; it’s just another version of this that you see in our village.”

The Customs That Bind Us is a series from BBC Travel that celebrates cultures around the world through the exploration of their distinctive traditions.

Join more than three million BBC Travel fans by liking us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter and Instagram.

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter called "If You Only Read 6 Things This Week". A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Capital and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.

BBC Travel

0 notes

Link

article by Kamala Thiagarajan, Ensia.

posted by: Frank

0 notes

Link

At St. Claret's School in India, snack time is time for an ethical decision. Students could toss a few coins in the box — or just take the food and walk away.

(Image credit: Kamala Thiagarajan for NPR)

0 notes

Quote

Unfortunately, diagnosing leprosy is extremely difficult. At the moment, the standard method is to take a biopsy. With this technique, a tiny incision is made on a skin lesion, through which blood is squeezed out and tissue fluid and pulp are collected for testing under the microscope. But this method is laborious and expensive, requiring a laboratory and technical expertise. This is particularly challenging in rural areas, where laboratory facilities are not always available, as well as in low-income countries where leprosy is prevalent and resources are scarce. "As a result, many patients are diagnosed late in the course of the disease when nerve and skin damage has already occurred," says Sunkara.

Kamala Thiagarajan, ‘Leprosy: the ancient disease scientists can't solve’, BBC

3 notes

·

View notes

Link

These 18 insanely dangerous spots are gaining popularity among yogis wanting picture-perfect Instagram posts. But are pictures like these are admirable and inspiring—or an example of how yoga is getting further and further away from its roots?

Daredevil Instagram yoga pictures like this one may get lots of "likes"—but are they severely lacking in common sense?

We’ve all heard yoga teachers encouraging us to push past our comfort zones during class. Yoga, after all, is a practice of self-evolution. But some yogis may be taking the phrase “find your edge” a little too far. Case in point: We all collectively gasped this summer when a woman was spotted doing Vrksasana (Tree Pose), backbends, and a series of inversions just inches from a notoriously unstable chalk cliff in England, known as Seaford Head.

Kamala Thiagarajan, a yogi in India, says this type of daredevil exercise is at odds with the yoga tradition. In her home country, yoga is a way of life beyond the physical asanas. “I’m all for people learning yoga the right way,” she says. That means no barns, goats, kittens, or other gimmicks. “As for cliff yoga in particular,” she says, “I think it's attention-seeking and severely lacking in common sense.”

See also Tips from Social Media’s Top Yogis on How to Handle Haters and Trolls

The Seaford Head spectacle is not an isolated incident. Instagram has given rise to more yogis than ever practicing poses that are more daring than dharma. Here are just a few examples of practitioners who have found their own edge—from Wedding Cake Rock in Australia to the isle of Cyprus to the Flatiron mountains in Colorado.

Check out the images here and then tell us: Do you think Instagram pictures like these are admirable and inspiring—or an example of how yoga is getting further and further away from its roots?

See also Patanjali Never Said Anything About Yoga Selfies

View the 18 images of this gallery on the original article

0 notes

Text

Don't Do It for the Gram: 18 Dangerous Instagram Yoga Photos

These 18 insanely dangerous spots are gaining popularity among yogis wanting picture-perfect Instagram posts. But are pictures like these are admirable and inspiring—or an example of how yoga is getting further and further away from its roots?

Daredevil Instagram yoga pictures like this one may get lots of "likes"—but are they severely lacking in common sense?

We’ve all heard yoga teachers encouraging us to push past our comfort zones during class. Yoga, after all, is a practice of self-evolution. But some yogis may be taking the phrase “find your edge” a little too far. Case in point: We all collectively gasped this summer when a woman was spotted doing Vrksasana (Tree Pose), backbends, and a series of inversions just inches from a notoriously unstable chalk cliff in England, known as Seaford Head.

Kamala Thiagarajan, a yogi in India, says this type of daredevil exercise is at odds with the yoga tradition. In her home country, yoga is a way of life beyond the physical asanas. “I’m all for people learning yoga the right way,” she says. That means no barns, goats, kittens, or other gimmicks. “As for cliff yoga in particular,” she says, “I think it's attention-seeking and severely lacking in common sense.”

See also Tips from Social Media’s Top Yogis on How to Handle Haters and Trolls

The Seaford Head spectacle is not an isolated incident. Instagram has given rise to more yogis than ever practicing poses that are more daring than dharma. Here are just a few examples of practitioners who have found their own edge—from Wedding Cake Rock in Australia to the isle of Cyprus to the Flatiron mountains in Colorado.

Check out the images here and then tell us: Do you think Instagram pictures like these are admirable and inspiring—or an example of how yoga is getting further and further away from its roots?

See also Patanjali Never Said Anything About Yoga Selfies

View the 18 images of this gallery on the original article

from Yoga Journal https://ift.tt/2OeLQtp

0 notes

Text

Don't Do It for the Gram: 18 Dangerous Instagram Yoga Photos

These 18 insanely dangerous spots are gaining popularity among yogis wanting picture-perfect Instagram posts. But are pictures like these are admirable and inspiring—or an example of how yoga is getting further and further away from its roots?

Daredevil Instagram yoga pictures like this one may get lots of "likes"—but are they severely lacking in common sense?

We’ve all heard yoga teachers encouraging us to push past our comfort zones during class. Yoga, after all, is a practice of self-evolution. But some yogis may be taking the phrase “find your edge” a little too far. Case in point: We all collectively gasped this summer when a woman was spotted doing Vrksasana (Tree Pose), backbends, and a series of inversions just inches from a notoriously unstable chalk cliff in England, known as Seaford Head.

Kamala Thiagarajan, a yogi in India, says this type of daredevil exercise is at odds with the yoga tradition. In her home country, yoga is a way of life beyond the physical asanas. “I’m all for people learning yoga the right way,” she says. That means no barns, goats, kittens, or other gimmicks. “As for cliff yoga in particular,” she says, “I think it's attention-seeking and severely lacking in common sense.”

See also Tips from Social Media’s Top Yogis on How to Handle Haters and Trolls

The Seaford Head spectacle is not an isolated incident. Instagram has given rise to more yogis than ever practicing poses that are more daring than dharma. Here are just a few examples of practitioners who have found their own edge—from Wedding Cake Rock in Australia to the isle of Cyprus to the Flatiron mountains in Colorado.

Check out the images here and then tell us: Do you think Instagram pictures like these are admirable and inspiring—or an example of how yoga is getting further and further away from its roots?

See also Patanjali Never Said Anything About Yoga Selfies

View the 18 images of this gallery on the original article

0 notes

Video

youtube

Pleasantly discovering the rare melakarta raga Jyotiswaroopini on the veena by Kamla Thiagarajan.

0 notes

Quote

In recent years, in wetlands across India, aquaculture has become a menace, Kantimahanti says. "People dig ponds, add chemical feed so that naturally occurring fish and prawns grow bigger and fetch better rates in the market. This alters the natural salinity of the soil." Aquaculture often leads to increased conflict between humans and fishing cats. Lured by the giant fish, the cats that come to hunt often end up in aggressive face-offs with humans. After a few years, the ponds are abandoned when the water table is too polluted, and the aquaculture farmers move on to a different patch, leaving coastal Andhra Pradesh studded with the abandoned farms.

Kamala Thiagarajan, 'The fight to save India's most elusive cat', BBC

#BBC#Kamala Thiagarajan#India#Kantimahanti#wetlands#aquaculture#fishing cat#pollution#Andhra Pradesh

6 notes

·

View notes