#julien le blant

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Julien le Blant, Destruction of the tree of liberty, XIX c, Musée de Cholet

I stumbled upon this artwork by accident while browsing collections of the Cholet art museum. It depicts one of the very common scenes from the Vendée war: the peasants burning the tree of liberty, which for them was actually a symbol of oppression. Le Blant's ability to convey a subtle sense of irony in his works is for me what makes his art so captivating and even disturbing at times.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

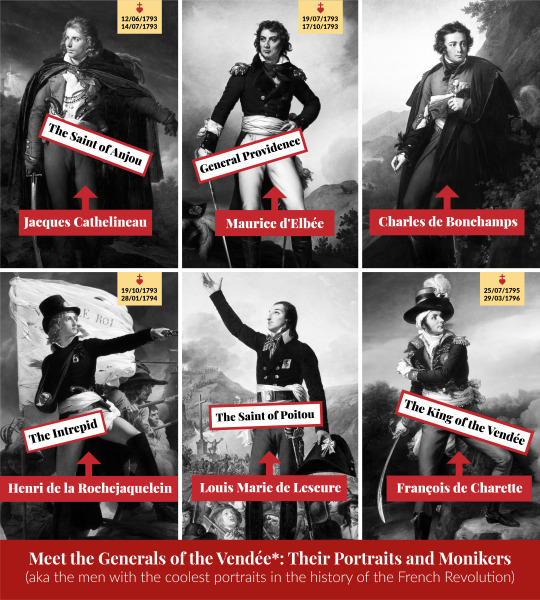

I'm still neck-deep in my studies of the Vendée, and what I've found particularly fascinating is that nearly every (1) prominent general not only boasts an impressively cool portrait but also sports a rather fetching nickname.

The nicknames are sourced from the Memoirs of the Marquise de La Rochejaquelein. How reliable is she? The lady lost her father and both her husbands in two separate Vendéen royalist uprisings, so she's hardly an unbiased chronicler. However, it's a reasonable assumption that, irrespective of one's views on the beliefs of these six men, they exhibited considerable courage and grace in their tragically brief lives—something even their Republican foes, begrudgingly, acknowledged.

Moreover, even if the cool monikers might be embellished, they're somewhat incidental to the broader mythos surrounding the Vendéen generals(2)

The truly intriguing part is the blatantly obvious piece of Royalist propaganda embodied by the six portraits and what they reveal—not so much about the portrayed subjects, but about the man who commissioned them: Louis XVIII (3).

Every Vendée General needs a Good, King-approved, Profile Picture

Now, I'm no expert on Louis XVIII, but he seems considerably more sensible than either one of his brothers. During their reigns, both the previous Louis and the subsequent Charles X appeared to have missed the memo that the times were changing, managing to piss off masses of people. Louis XVIII, in contrast, was painfully aware of the precariousness of his position. These portraits show as much.

Understandably, imagery during the First Empire tended to avoid commemorating the Revolution or acknowledging its victims. The Bourbon Restoration opted for a different tack: it sought to acknowledge the allegiance to the crown of those who opposed the revolution without reminding the public of the implications of such loyalty: namely war; a very bloody war.

In 1816, Louis XVIII commissioned a series of portraits to adorn the Hall of the Guards at the Palace of Saint-Cloud, depicting generals of the Vendée. Since he is often (apocryphally) quoted as saying that he owes his crown to the Vendée, the subject matter makes sense. The result, as you can see, was suitably glorious (4).

However, comparing these paintings to those of the Vendée created during the Third Republic by artists like Julien Le Blant, Paul-Émile Boutigny, Alexandre Bloch and many more reveals a notable omission: the blood, the violence, the enemy. Now, before you argue that it's just the era's style, go take a look at some of the paintings of Napoleon’s generals—many depict the enemy lurking ominously in the background. Yet, for portraits of six men who fought in a conflict so brutal it's sometimes termed a genocide, these images are remarkably sedate.

*Spoiler Alert*: It’s intentional.

Louis XVIII wasn’t an idiot. He clung to the throne by the skin of his teeth. Now, I’m speculating, but he probably liked his head enough to want to keep it firmly on his shoulders. He might have been grateful to the Vendéans and eager to indulge in a bit of old-fashioned Royalist propaganda, but he wasn’t about to spark another civil war over it.

Thus, these portraits, intentionally devoid of any overt warfare imagery, focus instead on symbols of monarchy and religion. We see the white flags of the Bourbon kings, rosaries, sacred hearts and white cockades adorning men who appear more like martial saints than soldiers.

Bonchamps's portrait lacks even a weapon (he holds a quill). In his painting, Cathelineau (5) is so laden with rosaries and crosses he might as well have raided the Vatican Gift Shop. Lescure's portrait drowns in Christian symbolism to the point of satire. Charette appears to be triumphant and is dressed in the outfit he had on when he entered Nantes after the Treaty of La Jaunaye. D’Elbee is an outlier, painted during the reign of Charles X after a decade of rosaries and white cockades, allowing the artist some leeway with the excessive symbolism.

Of all the portraits, that of Henri de La Rochejaquelein by Pierre Narcisse Guérin(6) stands out as the most striking. The young leader is portrayed in a dynamic posture, which projects a sense of forward movement and leadership yet avoids any overt display of aggression. La Rochejaquelein is the only one clearly portrayed amidst battle, in a heroic poise, aiming his gun at an invisible off-the-canvas enemy. Guérin gives us just a hint of the Republican army by showing the tips of Republican bayonets in the background—just enough to suggest opposition, yet not enough to relive the battles.

Notably, while dripping in Royalist symbols, his portrait eschews overt religious iconography beyond the Sacred Heart. In fact, the painting goes so far as to replace what is known to be La Rochejaquelein’s flag with a more royalist-focused one.

The Conspiracy of La Rochejaquelein’s flag

How do we know this? Well, the actual flag was preserved by the Beauregard family, whose ancestors held commanding roles in the Vendéen army. What’s written on the flag is not “Vive le Roi” (7) but “PRO ARIS REGE ET FOCIS”, translating to “For Our Altars, King, and Hearths”. Notice the order—king follows altars? Now, before you suggest that neither Guérin nor Louis XVIII could have known what was inscribed, I will concede that Guérin might not have, but Louis XVIII actually handled the flag a year before commissioning the portrait.

After Rochejaquelein's death, his comrades took the flag to Charette's army, which continued to use it. In 1814, one of Charette's former officers presented it to Louis XVIII. The king then gifted it to Louis de la Rochejaquelein during the 1815 uprising. After his demise at the Battle of Les Mathes, Auguste, the last of the three La Rochejaquelein brothers, preserved it until 1832 before, prior to his exile, bequeathing it to the Beauregard family, to whom he was related.

So, putting my metaphorical tinfoil hat firmly in place, I will conclude that it seems the King didn't want to share the dashing young Compte de la Rochejaquelein with the Pope.

Jokes aside, Rochejaquelein’s portrait was the first completed, likely reflecting the true intent of the King’s propaganda effort: to reaffirm a Royalist identity and provide a heroic image that could encourage unity rather than division. Over time, the overt Royalist symbols were toned down—probably because someone hinted to the king that he was being a bit much—but one element remained consistent: the absence of violence.

The remaining five Vendéean generals' portrayals as dignified, pious leaders rather than battlefield warriors are a rather perfect metaphor for the narrative Louis XVIII sought to promote throughout his reign—a narrative of reconciliation, remembrance, and a gradual, non-confrontational restoration of the monarchy to what he perceived as its rightful, almost divine, station. Essentially, Louis XVIII was too smart and fond of his head and crown to go all-in on the whole absolutist monarchy thing (8).

... If you've actually made it this far and read this whole thing, please know you're one of my favourite people in the whole wide world...

Notes:

(1) Apart from Stofflet, for reasons I won’t speculate on here because this thing is already over 2000 words long…

(2) This was all I intended to mention before I tumbled down a rabbit hole into the realm of early Restoration imagery and emerged with a mini-essay on early Restoration propaganda...

(3) the former Count of Provence and brother to the guillotined Louis XVI)

(4) The Louvre Collection has a number of paintings marked as being commissioned for the guard room in Saint Cloud. In chronological order, they are:

Henri Duverger, comte de La Rochejaquelein - Guérin, Pierre-Narcisse (1816)

Louis-Marie de Salgues, marquis de Lescure (1766-1793), général vendéen by Lefèvre, Robert (1816)

Charles-Melchior-Artus marquis de Bonchamps (1760-1793), général vendéen by Girodet de Roucy-Trioson (1816)

Jacques Cathelineau (1759-1793) généralissime vendéen by Girodet de Roucy-Trioson ( comissioned in 1816 but exposed in the Salon of 1824)

Pierre Jean Baptiste Constant, comte de Suzannet by Mauzaisse, Jean Baptiste(1817)

François Athanase Charrette dela Contrie by Guérin, Paulin (1819)

Louis Duverger, Marquis de La Rochejaquelein by Guérin, Pierre-Narcisse (1819) – this is Henri de La Rochejaquelein’s baby brother, he died leading the Vendee revolt in 1815

Louis, comte de Frotté, général vendéen by Louise Bouteiller

Maurice Joseph Louis Gigost d'Elbée by Guérin, Paulin (1825) – Comissioned by Charles X

Antoine Philippe de la Trémoille, prince de Talmond, général vendéen by Cogniet, Léon - (1826) – Comissioned by Charles X

Louis-François Perrin, comte de Précy (1742-1820), général vendéen by Dassy, Jean Joseph (1829) – Comissioned by Charles X

(5) Fun fact: Cathelineau’s son stood for his father’s portrait

(6) Not to be confused with Guérin, Paulin

(7) According to his wife, this would have been Lescure's flag

(8) Very in character for a king who refused to be crowned. And this is a good thing. Especially seeing how his little brother turned out…

Sources:

Crosefinte, Jean-Marie. Les Drapeaux Vendéens.

La Rochejaquelein, Marie-Louise-Victoire. Memoirs of the Marquise de la Rochejaquelein.

Mansel, Philip. Louis XVIII.

#frev#french revolution#vendee war#vendee#la rochejaquelein#cathelineau#d'elbee#bonchamps#lescure#charette#restoration#louis Xviii#royalist#amateurvoltaire's essay ramblings

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

0 notes

Text

Execution of General Charette, in Nantes, March 1796

by Julien Le Blant

#julien le blant#art#painting#history#france#french#royalist#revolution#firing squad#revolt#vendée#françois de charette#vendée wars#french revolutionary wars#europe#european

18 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Spahi, 1919, Julien Le Blant

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chouans

View On WordPress

#1793#Alphonse de Boisricheux#Auguste de La Rochejaquelein#Balzac#Charles Coëssin de la Fosse#Charles Moreau-Vauthier#Colonnes infernales (guerres de Vendée)#Evariste Carpentier#Granville#Henri de la Rochejaquelein#Historial de Vendée#Hubert-Sauzeau#Jacques Cathelineau#Jean Chouan#Jean-François Hue#Joseph Bara#Jules-Benoît Lévy#Julien Le Blant#Les Chouans#Louis de La Rochejaquelein#Lucien de Latouche (peintre)#Marie Louise Victoire de La Rochejaquelein#Massacre des Lucs sur Boulogne (guerres de Vendée)#Mémoires de la marquise de La Rochejaquelein#Mémorial de la Vendée#Napoléon#Pierre-Narcisse Guérin#Prince de Talmont#Robespierre#Victor Hugo

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Exécution du général Charette place de Viarmes à Nantes, mars 1796 Julien Le Blant, 1883

16 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Death of General D'Elbée/The Execution of General Charette - Julien Le Blant

Death of Henri de La Rochejaquelein - Alexander Bloch

1 note

·

View note

Text

Pardon the Republic

Source Images

“Badge of the Coeur Chouan,” Author Unknown “Exécution du général Charette place de Viarmes à Nantes, mars 1796,” by Julien Le Blant “Photograph of Chateau de Taillebourg en Charente-Maritime,” by Tux-Man “Henri de La Rochejaquelein , leader of the revolt in the Vendee,” by Pierre-Narciesse Guerin

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Îles de Vendée

View On WordPress

#Antoine Le Dû#Île d&039;Yeu#Berthe Cuirblanc#Emile Dezaunay#Eugène Vergez#Guerres de Vendée#Julien Le Blant#L&039;Afrique (navire et naufrage)#L&039;Herbaudière#Léon Printemps#Maurice Joseph d&039;Elbée#Noirmoutier#Philippe Pétain#U-Boot#Vendée#Vieux château (Yeu)#Zéphirin Belliard

0 notes

Text

Dieu Le Roi (Repeat)

Dieu Le Roi (Repeat)

Originally posted September 12, 2013.

Elements in this collage:

“Badge of the Coeur Chouan,” Author Unknown

“Exécution du général Charette place de Viarmes à Nantes, mars 1796,” by Julien Le Blant

“Photograph of Chateau de Taillebourg en Charente-Maritime,” by Tux-Man

“Richard I the Lionheart, King of England,” by Merry-Joseph Blondel

“(Abstract),” by Bui Xuan Phai

“Henri de La Rochejaquelein ,…

View On WordPress

0 notes