#judgment at nuremberg

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

#movies#polls#judgment at nuremberg#stanley kramer#60s movies#spencer tracy#burt lancaster#have you seen this movie poll

81 notes

·

View notes

Text

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Judgment at Nuremberg, Stanley Kramer

#judgment at nuremberg#stanley kramer#1961#1960s#60s#b&w#usa#american#movie#film#cinema#cinematography#screencaps#stills

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

here's your random reminder that if you're in the US, you can watch judgment at nuremberg for free (with ads) on youtube right now.

#yes i reblogged some posts about it earlier this week and now i'm finishing my rewatch of the movie#it's just so good#and v timely#judgment at nuremberg#(the way i always want to spell it judgement. the random UK spellings that eeked their way into my brain thanks to my british teachers lol)

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Films Watched in 2024: 74. Judgment at Nuremberg (1961) - Dir. Stanley Kramer

#Judgment at Nuremberg#Stanley Kramer#Spencer Tracy#Maximilian Schell#Burt Lancaster#Richard Widmark#Marlene Dietrich#Judy Garland#Montgomery Clift#William Shatner#Films Watched in 2024#My Post

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

#remembering #judygarland #actress #singer #thewizardofoz #astarisborn #judgmentatnuremberg #meetmeinstlouis #easterparade #AndyHardyMeetsDebutante #BabesonBroadway #ZiegfeldFollies #TilltheCloudsRollBy #IntheGoodOldSummertime #AChildIsWaiting #ICouldGoonSinging #thepirate

#remembering#judy garland#actress#singer#the wizard of oz#a star is born#judgment at nuremberg#meet me in st. louis#easter parade#andyhardymeetsdebutante#babesonbroadway#ziegfeld follies#tillthecloudsrollby#inthegoodsoldsummertime#achildiswaiting#icouldgoonsinging#thepirate

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

From Judgment at Nuremberg (1961):

Colonel Tad Lawson: They share with all the leaders of the Third Reich responsibility for the most malignant, the most calculated, the most devastating crimes in the history of all mankind. And they are perhaps more guilty than some of the others, for they had attained maturity long before Hitler's rise to power. Their minds weren't warped at an early age by Nazi teachings. They embraced the ideologies of the Third Reich as educated adults, when they, most of all, should have valued justice!

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Top two vote-getters will move on to the next round. See pinned post for all groups!

#best best adapted screenplay tournament#best adapted screenplay#oscars#academy awards#judgment at nuremberg#abby mann#out of africa#kurt luedtke#karen blixen#errol trzebinski#judith thurman#the bridge on the river kwai#pierre boulle#carl foreman#michael wilson#precious#geoffrey s. fletcher#sapphire#the big short#charles randolph#adam mckay#michael lewis#on golden pond#ernest thompson#poll#bracket tournament#polls#brackets

1 note

·

View note

Text

25 of 250: Favorite Films - Judgment at Nuremberg

Not long ago, work colleagues and I got into a discussion about what our favorite films were. Given my categorical nature I could not resist writing down a list and, as a writing challenge, have decided to write 250 word reviews of my favorite 25 films of all-time. Note: these are my favorite films, not what I think are the best films of all time.

Directed by: Stanley Kramer

Written by: Abby Mann

Starring: Spencer Tracy, Burt Lancaster, Richard Widmark, Marlene Dietrich, Maximilian Schell, Judy Garland, Montgomery Clift, William Shatner

Year/Country: 1961/United States

Trivia question: who is the lowest billed actor to win Best Actor at the Oscars? The answer is Swiss actor Maximilian Schell for Judgment at Nuremberg. Stanley Kramer’s tense Holocaust trial film is at once grandstanding and surprisingly nuanced. The credit for that belongs mostly to screenwriter Abby Mann and a lightning in a bottle performance by Schell.

The film is a fictionalized account of the Judges Trial (part of the post-WWII Nuremberg Trials). The trials for all the major Nazis are done and now it’s the regime’s lesser officials turn. Judge Haywood (Tracy) is the chief justice deciding the case. In the dock are four high profile German judges, including former Minister of Justice Janning (Lancaster). We witness various examinations and cross examinations and follow Judge Haywood as he genuinely attempts to understand what happened in Germany.

The miracle of this film is that the outcome of the trial is seriously in doubt. Mann’s screenplay understands the motives of many Germans weren’t cut and dry. It even questions the legitimacy of the trials at all; in the words of defense attorney Rolfe (Schell), “I could show you a picture of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Thousands and thousands of burned bodies. Women and children. Is that their superior morality?” It’s clear from Rolfe’s first cross-examination of a witness that this movie will be special. Schell is relentlessly logical. He picks apart each witness so thoroughly you believe the defense can win, and it’s easy to see why Schell won his Oscar.

#25 of 250#Favorite Films#Film Review#judgment at nuremberg#stanley kramer#abby mann#maximilian schell#burt lancaster#spencer tracy

1 note

·

View note

Text

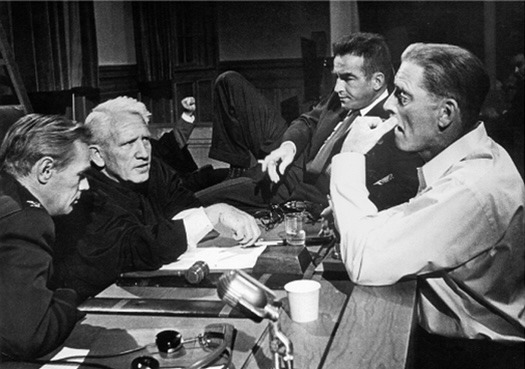

Richard Widmark, Spencer Tracy, Montgomery Clift and Burt Lancaster on the set of Judgment at Nuremberg, 1961.

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

If the Nuremberg Laws were Applied…

-Noam Chomsky

Delivered around 1990

If the Nuremberg laws were applied, then every post-war American president would have been hanged. By violation of the Nuremberg laws I mean the same kind of crimes for which people were hanged in Nuremberg. And Nuremberg means Nuremberg and Tokyo. So first of all you’ve got to think back as to what people were hanged for at Nuremberg and Tokyo. And once you think back, the question doesn’t even require a moment’s waste of time. For example, one general at the Tokyo trials, which were the worst, General Yamashita, was hanged on the grounds that troops in the Philippines, which were technically under his command (though it was so late in the war that he had no contact with them — it was the very end of the war and there were some troops running around the Philippines who he had no contact with), had carried out atrocities, so he was hanged. Well, try that one out and you’ve already wiped out everybody.

But getting closer to the sort of core of the Nuremberg-Tokyo tribunals, in Truman’s case at the Tokyo tribunal, there was one authentic, independent Asian justice, an Indian, who was also the one person in the court who had any background in international law [Radhabinod Pal], and he dissented from the whole judgment, dissented from the whole thing. He wrote a very interesting and important dissent, seven hundred pages — you can find it in the Harvard Law Library, that’s where I found it, maybe somewhere else, and it’s interesting reading. He goes through the trial record and shows, I think pretty convincingly, it was pretty farcical. He ends up by saying something like this: if there is any crime in the Pacific theater that compares with the crimes of the Nazis, for which they’re being hanged at Nuremberg, it was the dropping of the two atom bombs. And he says nothing of that sort can be attributed to the present accused. Well, that’s a plausible argument, I think, if you look at the background. Truman proceeded to organize a major counter-insurgency campaign in Greece which killed off about one hundred and sixty thousand people, sixty thousand refugees, another sixty thousand or so people tortured, political system dismantled, right-wing regime. American corporations came in and took it over. I think that’s a crime under Nuremberg.

Well, what about Eisenhower? You could argue over whether his overthrow of the government of Guatemala was a crime. There was a CIA-backed army, which went in under U.S. threats and bombing and so on to undermine that capitalist democracy. I think that’s a crime. The invasion of Lebanon in 1958, I don’t know, you could argue. A lot of people were killed. The overthrow of the government of Iran is another one — through a CIA-backed coup. But Guatemala suffices for Eisenhower and there’s plenty more.

Kennedy is easy. The invasion of Cuba was outright aggression. Eisenhower planned it, incidentally, so he was involved in a conspiracy to invade another country, which we can add to his score. After the invasion of Cuba, Kennedy launched a huge terrorist campaign against Cuba, which was very serious. No joke. Bombardment of industrial installations with killing of plenty of people, bombing hotels, sinking fishing boats, sabotage. Later, under Nixon, it even went as far as poisoning livestock and so on. Big affair. And then came Vietnam; he invaded Vietnam. He invaded South Vietnam in 1962. He sent the U.S. Air Force to start bombing. Okay. We took care of Kennedy.

Johnson is trivial. The Indochina war alone, forget the invasion of the Dominican Republic, was a major war crime.

Nixon the same. Nixon invaded Cambodia. The Nixon-Kissinger bombing of Cambodia in the early ’70’s was not all that different from the Khmer Rouge atrocities, in scale somewhat less, but not much less. Same was true in Laos. I could go on case after case with them, that’s easy.

Ford was only there for a very short time so he didn’t have time for a lot of crimes, but he managed one major one. He supported the Indonesian invasion of East Timor, which was near genocidal. I mean, it makes Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait look like a tea party. That was supported decisively by the United States, both the diplmatic and the necessary military support came primarily from the United States. This was picked up under Carter.

Carter was the least violent of American presidents but he did things which I think would certainly fall under Nuremberg provisions. As the Indonesian atrocities increased to a level of really near-genocide, the U.S. aid under Carter increased. It reached a peak in 1978 as the atrocities peaked. So we took care of Carter, even forgetting other things.

Reagan. It’s not a question. I mean, the stuff in Central America alone suffices. Support for the Israeli invasion of Lebanon also makes Saddam Hussein look pretty mild in terms of casualties and destruction. That suffices.

Bush. Well, need we talk on? In fact, in the Reagan period there’s even an International Court of Justice decision on what they call the “unlawful use of force” for which Reagan and Bush were condemned. I mean, you could argue about some of these people, but I think you could make a pretty strong case if you look at the Nuremberg decisions, Nuremberg and Tokyo, and you ask what people were condemned for. I think American presidents are well within the range.

Also, bear in mind, people ought to be pretty critical about the Nuremberg principles. I don’t mean to suggest they’re some kind of model of probity or anything. For one thing, they were ex post facto. These were determined to be crimes by the victors after they had won. Now, that already raises questions. In the case of the American presidents, they weren’t ex post facto. Furthermore, you have to ask yourself what was called a “war crime”? How did they decide what was a war crime at Nuremberg and Tokyo? And the answer is pretty simple. and not very pleasant. There was a criterion. Kind of like an operational criterion. If the enemy had done it and couldn’t show that we had done it, then it was a war crime. So like bombing of urban concentrations was not considered a war crime because we had done more of it than the Germans and the Japanese. So that wasn’t a war crime. You want to turn Tokyo into rubble? So much rubble you can’t even drop an atom bomb there because nobody will see anything if you do, which is the real reason they didn’t bomb Tokyo. That’s not a war crime because we did it. Bombing Dresden is not a war crime. We did it. German Admiral Gernetz — when he was brought to trial (he was a submarine commander or something) for sinking merchant vessels or whatever he did — he called as a defense witness American Admiral Nimitz who testified that the U.S. had done pretty much the same thing, so he was off, he didn’t get tried. And in fact if you run through the whole record, it turns out a war crime is any war crime that you can condemn them for but they can’t condemn us for. Well, you know, that raises some questions.

I should say, actually, that this, interestingly, is said pretty openly by the people involved and it’s regarded as a moral position. The chief prosecutor at Nuremberg was Telford Taylor. You know, a decent man. He wrote a book called Nuremberg and Vietnam. And in it he tries to consider whether there are crimes in Vietnam that fall under the Nuremberg principles. Predictably, he says not. But it’s interesting to see how he spells out the Nuremberg principles.

They’re just the way I said. In fact, I’m taking it from him, but he doesn’t regard that as a criticism. He says, well, that’s the way we did it, and should have done it that way. There’s an article on this in The Yale Law Journal [“Review Symposium: War Crimes, the Rule of Force in International Affairs,” The Yale Law Journal, Vol. 80, #7, June 1971] which is reprinted in a book [Chapter 3 of Chomsky’s For Reasons of State (Pantheon, 1973)] if you’re interested.

I think one ought to raise many questions about the Nuremberg tribunal, and especially the Tokyo tribunal. The Tokyo tribunal was in many ways farcical. The people condemned at Tokyo had done things for which plenty of people on the other side could be condemned. Furthermore, just as in the case of Saddam Hussein, many of their worst atrocities the U.S. didn’t care about. Like some of the worst atrocities of the Japanese were in the late ’30s, but the U.S. didn’t especially care about that. What the U.S. cared about was that Japan was moving to close off the China market. That was no good. But not the slaughter of a couple of hundred thousand people or whatever they did in Nanking. That’s not a big deal.

450 notes

·

View notes

Text

Joan Crawford presents Maximilian Schell his Best Actor Academy Award for JUDGMENT AT NUREMBERG at the 34th #Oscars in 1962.

29 notes

·

View notes

Note

LWA: To expand on @robinwithay's point some more, I am thinking again about Crowley's equivalent to Aziraphale's stubbornness when it comes to rejecting Heaven. Crowley just will. not. learn. that actions have consequences, and that the responsibility lies with the agent, not some nebulous figure out there somewhere. What's striking, in fact, is that "actions have. consequences" is the closest thing the GO universe has to divine providence in action: when Crowley does something, it comes back to bite his occult arse, without fail, every single time. Shut down the cell phone network? Great, can't call Aziraphale. Make yourself look good to Hell? By golly, Hell is going to give you all the sweet assignments. (From their POV, anyway.) Turn a freeway into a demonic sigil? Whoops, it's on fire when you need to cross it, and also a lot of people are dead. Moreover, not only does the universe keep pointing this out to Crowley, but so do the other characters. In S1e1 alone, Hastur, Aziraphale, and SATAN FOR CRYING OUT LOUD all call him out on the whiny "why me?!" business, and Hell does it again in "The Resurrectionists." ("Off my head on laudanum. Not responsible for my actions!" HELL: Oh honey, no.) Arguably, "why me?" is the /one/ question to which Crowley gets a definitive answer, and he consistently refuses to listen to or learn anything from it.

Gaiman's very deliberate decision to prolong and inflate this aspect of Crowley's character is fascinating, because the Nuremberg Defense moment in the novel is there to put an /end/ to it. I keep harping on the Nuremberg Defense issue because in 1990, that was /topical/, not historical: at the time of publication, the most recent high-profile example of someone Nuremberg Defensing himself out of Nazi-era war crimes was Kurt Waldheim /in 1986/. Pratchett's and Gaiman's point in the novel is that Crowley's--and, more so than in the series, Aziraphale's--refusal to take responsibility for what they've done as Hell's and Heaven's agents leads inexorably to them thinking like, you guessed it, Nazi-era war criminals. But as of the end of S2, Crowley has still not come around to the moral epiphany about this that in the novel, Aziraphale has /first./ Instead, Gaiman's substitute for the Nuremberg Defense, the child murder subplot in S1, is averted in such a way that Crowley doesn't learn anything from it.

Further to the point that @robinwithay and others who responded made, you know who did learn something from the child murder subplot? Aziraphale. I said in an earlier ask that in S1, Aziraphale's own failure in the subplot is that he winds up deferring to Crowley's judgment, despite his own clear discomfort, because he cannot turn to Heaven for moral authority. "You can't kill kids" is not represented as a divine or infernal universal mandate--it's a /human/ mandate that transcends both. (That's entirely in keeping with the point, made in both the book and the series, that humans are capable of both far greater good than angels and far greater evil than demons.) In S2, Aziraphale does what he /should have done/ in S1, and says "no" to Crowley's proposal that Gabriel just be abandoned somewhere. I think people sometimes forget that Crowley, for all that he asks questions and nudges Aziraphale along out of his allegiance to the Heavenly party line, is not the series' moral arbiter. Aziraphale knows that Gabriel is facing "something terrible" and is not sure whether or not he's still "awful," but he does what S2 itself shows by the end to be the right thing. Doing the right thing sometimes means telling Crowley "no" and sticking to that no, just as, in S1, the moment Aziraphale hits on the right question to ask at the airfield, he moves /away/ from Crowley to stand with Adam.

good afternoon LWA!!!💕

okay so i feel some frank warning is due for anyone else reading my reply, especially if you're new around these here parts: what follows beneath the cut is going to be crowley-critical. it's not meant in bad faith, but recognising character shortcomings is important for all characters involved. there is (quite rightly) a lot of critique in relation to aziraphale in the fandom, and this is not in ignorance or denial of that - there are certainly points where aziraphale's actions throughout both seasons are called out, and i agree with a number of them - but a) that's not what im talking about here, that's a different post, and b) similar analysis of crowley is (as far as ive seen personally in the months ive been active) not as common - hence the post. if that's not your bag, fair enough, but take heed!!!✨

can't believe a fandom-specific cw for this is necessary but. here we are

(because i get asked this a fair amount - AWCW: Angel Who Crowley Was) (and just now recognising the grammatical error in this, ah well we move)

the part of crowley's character that does not accept consequences, and seemingly refuses to learn from them, is one of the most intriguing for me. as well as all of the instances that you've listed, this is something that we see as being so inherent to him that it even predates the fall; it's not a trait that is specific to crowley-as-a-demon, but to crowley-as-crowley. for all of the understandable reasons that AWCW felt he should ask questions, should challenge why his hard work and creativity was going to be put to waste as if it were nothing, he outright dismissed aziraphale's frankly prophetic advice that directly delivering criticism to the almighty, even if meant with the best of intentions, might spell for trouble... might even spell for AWCW's own personal ruin.

slightly unrelated, but another note: the mindset of, "if i were in charge", however much it might have been meant offhandedly or innocently, even connotes an incredible amount of hubris that, whilst not wholly condemnable in itself, gives an interesting insight into how crowley views himself from before the fall and going into present day.

AWCW's questions may come from a place of innocence and collaboration, and may speak to how much trust he placed in god/heaven to hear his questions with patience and understanding, but it still remains highly likely that he dismisses aziraphale's warning. and the reason he ignores it, most likely, is because it is not what he wants to hear, nor does it (in his eyes) benefit him to exercise caution. one could go a step further and suggest that this indicates a fatal "crowley knows best" mentality, which the rest of the two seasons doesn't exactly negate. and look - that's fine, ignoring advice is hardly an indictable offence, but if what you're doing goes to shit? that is on you.

shifting into speculation-mode in the absence of any confirmed account of the fall itself, we can presume that AWCW's questions fall on deaf/reticent/dismissive ears, and that will just as likely have left AWCW with a sense of frustration and resentment. i continue to be a really hopeful advocate of AWCW having had a lucifer-parallel narrative; that after what was essentially a dismissal, he may have precipitated (at least) the inception of the fall by way of knowingly or unknowingly planting the seeds of rebellion amongst the eventual-fallen... e.g. "they're not treating us fairly, all of our effort will be for nothing, all in service and deference to 'human beings', i tried to speak to god about it but they won't even hear me out."

i don't think he will have led the rebellion, that doesn't quite seem appropriate to his character, but certainly that he may have sparked the initial machinations, and then - by furfur's account - participated in the war. this, again, would fall in line with crowley's ongoing tumultuous relationship with consequences-borne-from-his-actions.

crowley's unreliable narratorship of his own fall is, by definition, untrustworthy, and as such it's not a given that he was unimpeachable in any participation of it. "i didn't mean to fall" would definitely suggest that it was not his intention, but if we return to the Dead Whale Theory, this is a dead whale that crowley has failed to fully accept, or learn from. he seems - when we consider how he inhabits the role of god (as he sees that role to be, anyway) in how he treats his plants in s1 and the goats in s2 - to be very much of the opinion that he is entirely innocent of any wrongdoing.

and in some respect, he's not wrong - asking questions is not a bad thing, it's a very good thing, and his willingness to do so is one of crowley's greatest assets - but his refusal to heed advice in favour of his own agenda, refusal to accept the answers given even (especially?) when he doesn't like them, to have potentially sparked dissent that led to a war (which he fought in), and his lack of accountability for the results, is where he falls down. im not going to go so far as to call it narcissistic behaviour, that feels a bit extreme, but there are... similarities. he doesn't learn from the whole fiasco in any manner that would indicate self-reflection, and instead seems to have walked away from the fall with his clear-cut conclusion that heaven was wrong, and are in fact The Bad Guys.

certainly, GO proposes that heaven isn't the traditional definition of truth, light, and good that aziraphale hopes that it is intrinsically... but crowley still hasn't reached the point of understanding the rest of what the narrative is saying.

heaven and hell are not always good and bad respectively, but they are not always bad and good respectively either. it's not a simple, 'we're turning this on its head' concept. it is altogether a veeeery grey system that simply exists, and it exists in the way that it always has done since the fall (possibly even before, in heaven's case). it is instead your choice whether or not to be part of that system, if you do not think it is right. if you continue be a part of that system, even if there are stakes involved that would make it difficult or compelling for you to remain and act within that system, you should at least recognise the consequences of your actions, accepting your part in it. this goes for all angels and demons, not just aziraphale and crowley. 'just following orders' may be understandable in some circumstances (e.g. threat to life of yourself or others), but does that mean that you are absolved of all responsibility?

we are, collectively, quick to point out that aziraphale has not fully learnt this, but it's clear that crowley has not either. it also suggests by extension that aziraphale is not always wrong, just as crowley is not always right. where actions-and-consequences are concerned, i'd tentatively wager that aziraphale at least demonstrates a bit more understanding of this than crowley does. aziraphale has been shown to recognise when he is wrong, accept it, and make efforts to correct himself or remedy his erroneous actions moving forward. aziraphale hides the antichrist's location from crowley and holds out hope for a higher power to see reason/do the right thing, but when aziraphale gets the confirmation that heaven isn't going to do the right thing by stopping the apocalypse, the first thing he does is call crowley to tell him about adam. you also then have, as you said, aziraphale physically and figuratively moving to stand with humanity; good and bad are just names for sides, and 'human incarnate' equally embraces both concepts (in their truest meaning) and yet similarly rises above both. this is the side to back; 'our side', to aziraphale, doesn't mean just him and crowley, but humanity too.

alternatively (really grinding at the fall thing here, sorry), even if AWCW did not willfully participate in any goings-on of the rebellion, and the fact that he fell was an incident in which he was blamelessly implicated/scapegoated... well, even then, that does not give him a free-pass for him to continuously believe that he is innocent in all matters that follow. sure, he may have been blameless in the fall, but does that mean he's therefore beyond reproach or above accountability for... everything he does/says that occurs afterwards?

setting up the perfect environment for armageddon? tempting aziraphale to kill the antichrist? giving a group of humans live firearms in order to make a point? abandoning aziraphale and retracting 'our side' when aziraphale asked him for help with hiding gabriel? withholding information from aziraphale that directly concerns him and his safety? i said it in a separate post (mainly because it would have made this one a really ungodly length), but my point remains the same; regardless of his part or not-part in the fall, crowley's character does not develop in this arena, despite incredibly formative experiences that might in fact impart an important lesson upon him*.

*and that lesson - again! - is not that he shouldn't ask questions, but instead that his actions may prove to have consequences that he does not like or want, but must accept anyway, taking accountability for his part in them.

not changing does not mean that he is perfect from (before) the beginning, but instead suggests that he is very comfortable being the same person that he's always been... and in some ways, it's commendable to remain true to oneself, but it's equally not conducive to growth... and crowley still has a lot of growing to do (he has grown since s1: his kindness for one thing absolutely has!).

crowley does not seem to recognise where his lack/refusal of development may have contributed to the breakdown in his and aziraphale's relationship by the end of s2, even if that lack/refusal is not directly referenced in the final fifteen. by this i mean: crowley appears to have a very clear expectation of how he believes aziraphale does - and perhaps should - think and behave. crowley, to crowley's mind, he has the right of it ("crowley knows best"), and that includes him thinking that aziraphale will act in the way he has come to expect as a result of his influence on him. crowley has poked and prodded aziraphale away from heaven's rhetoric and dogma* about what good and right is, which aziraphale desperately needed... but does that mean that aziraphale should replace that belief system with Morality According To Crowley? instead of developing his own ...exactly as aziraphale demonstrates in the final fifteen?

when aziraphale doesn't do what crowley thinks he ought to, instead of crowley considering that his perspective of aziraphale may not actually be reality, he takes it as a betrayal and a rejection of crowley himself. though we won't really know until s3 (and possibly not even then) what crowley was really thinking during the final fifteen, it isn't too impossible a notion that crowley now thinks that aziraphale has chosen heaven over him, and loves heaven more than him. which... after everything that he has seen aziraphale go through, battle, and come to terms with, does he truly think that little of him? that aziraphale would think that little of crowley? if he does, that's an incredibly sad and disappointing prospect. perhaps bold of me to say, but sometimes it seems that there are some specific similarities between crowley and heaven in how they individually view and treat aziraphale.

*whilst crowley encouraging aziraphale to think outside of heaven is a good thing, and aziraphale definitely needs it, it does elicit out a couple of concerning traits from them both that, whilst may be borne from respective senses of powerlessness, they manifest onto each other.

crowley has a hero/saviour complex, which aziraphale encourages. aziraphale encourages it - by his own admission - because he thinks it makes crowley happy. however, what is not clear is whether aziraphale recognises that in allowing this, not only does it potentially suggest that crowley benefits from perceiving aziraphale as incapable of protecting himself, and any ability to protect himself (or indeed crowley! 1941!) threatens what crowley thinks is his place in aziraphale's existence, but also that aziraphale himself is projecting what he doesn't get from heaven/god onto crowley.

it similarly isn't clear whether crowley realises that not only he has been - in part - substituted for god/heaven in aziraphale's eyes because he provides the love, acceptance and confirmation of worth that aziraphale has craved since time immemorial, but also that in keeping information from aziraphale that directly concerns him, crowley is nurturing an environment where aziraphale will make decisions according to the limited information he has. we even have a suggestion of this in the final fifteen: to aziraphale's mind, it won't be crowley that protected him from heaven's threat of erasure from the BOL (ie. crowley didn't tell him), it was the metatron. (and if aziraphale finds out about/puts together, in s3, the sheer amount and scale of information that crowley kept from him, there is going to be the hard conversation of whether trust between them can exist as it has before, built over thousands of years).

just as crowley has an arguably skewed perception of aziraphale, aziraphale has a skewed perception of him in return (the levels of codependency are off the charts, lads). it's not a unique observation to say that they both need this break in order to renegotiate within themselves how they view each other, but it's no less true for being repeated.

#bracing myself for impact#dont say i didnt warn you though#im gonna go make an amv now k thx bye#good omens#ask#aziraphale meta#feral domestic/final fifteen meta

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

Marlene Dietrich in a publicity shot for Judgment at Nuremberg (Stanley Kramer, 1961)

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Playing Avowed, having lots of fun with it along multiple barometers, but right now I just want to highlight that it's nice to have the theme of 'Empire: Good or Bad, Question Mark' writ large. More specifics and spoilers below the cut. (I'm only partway into Emerald Stair, just finished the Steel Resolve sidequest)

I think a lot about the '61 film Judgment at Nuremberg. I saw it as a teen/young adult around 2010, and yeah it made a pretty decisive impression. Especially the one contrite judge's testimony; he, and his countrymen, were scared of poverty and instability, and willfully led by a tyrant into war, scapegoating, genocide, cultural 'purification'. Nothing about the former, being scared, justifies any of the latter. And like, yeah, no fucking duh, but obviously it's worth pointing out that the same rhetoric works just as well in America as it did in Germany. And the movie doesn't shy away from pointing out that America's hands and history are just as bloody.

Watching my country embrace full-throated fascism, especially those who should fucking know better, has been shit. And it's been additionally frustrating because before I realized how important it was to care about politics, the only cogent political thought I had was, 'if party politics are only based on beating the other party, a dictator is inevitable'.

If a young white man, raised in a conservative household, with a catholic private-school education, can figure that basic shit out, what the actual fuck is wrong with the rest of my country's men? I was set up perfectly to be a completely compliant cog of the dominant social order and I'm not, because it is self-evident to me that bootstrap capitalism is horseshit??? That the government is supposed to help people more than it should fight wars for money??? That cultural christian hegemony is mega-horseshit and actively kills people actual christians are supposed to actually care about????? I'm not a """successful man""" by patriarchal standards yet I am not resentful about that? It doesn't make me want to double down on the false promises of performative toxic masculinity??? How am I able to see this, when so many of my country's white men cannot?

Avowed's premise is excellent for playing in that story space of 'what does it mean to you to be the representative of imperial will?'. The colonial frontier, island of misfits, the party being comprised of the outcasts' outcasts, and what better antagonistic lightning rods than the steel garrote led by savathun Lödwyn. (Yes devs please keep hiring Debra Wilson Im so glad I paid full price for this.)

The PC's assassination is such a funny setup for act 1 intrigue. Like, it feels like they genuinely expect you to be REALLY mad about it, but game brain aside yeah even if that was me I wouldnt be mad about it long enough to want to kill the rebels over it. I'm the imperial freaking envoy. Of Course the locals want me dead. Doubly so once it's clear Ygwulf is having visions. People are doing ridiculous shit all the time in this world on the justification of visions/prophecies/other idealogical craziness. Reading the notes makes it very clear lodwyn is the real problem that needs to be addressed. She is either directly responsible for the dreamscourge or is a part in whatever constellation has brought it forth. (95% confidence)

I paid the ondra priestess for info but then convinced herself to turn herself in (I was kinda pissed at her describing Ygwulf as such a big deal). I killed through the rebels until I got to Ygwulf and he seemed to fold pretty easily, and again having read the notes, it's obvious he is highly motivated but neither pragmatic nor forthinking, he just Really Cares, y'know? Someone has to Do Something, y'know? When I went back to finally meet lodwyn I hoped to provoke more out of her but alas. Afterward, the ondra priestess was the only one hanged, and I didnt snitch on the rebels, but multiple npcs referred to ygwulf being hanged? But I also still got the rebel endorsement signed by ygwulf?? I think my choices led to slightly bugged outcomes.

In summary: my choices were very muddled politically, because I played it by vibes not a firm conviction, and my focus is on the Dreamscourge and stopping lodwyn. So it's not surprising my outcomes in act 1 were muddled too.

Steel Resolve was a much more satisfying arc. Listening to Dorsa's explanation, depriving her of the 'security' she so foolishly killed for(I told her to run because the Rangers would be hunting her), then kicking the shit out of the thugs knowingly trying to destabilize shit. Great fucking time. Eat fucking rocks Aelfyr. Think I might actually commission someone to make fanart of the fight.

It brought Judgment at Nuremberg back to the forefront of my mind again. I am sympathetic toward the desire for social and economic stability. I am not sympathetic toward the blind acceptance of injustice, of imperial violence, as the means of achieving those goals. You can't uphold a society built on the backs of slavery, ethnic cleansing, and perpetual violence. It has to be torn down.

I'm very excited to see how Avowed further unfolds, and I look forward to replaying this later to see how the fully convicted pro/anti imperial sentiments get expressed. The writing here is on point for Obsidian. Can't fucking believe SkillUp described it 'feels like it's just content'. (I can actually believe it; SkillUp is a snob, and opinionated, and that's why I like him. but fuck is he wrong sometimes.)

8 notes

·

View notes