#joseph arkley

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The Capture, 2022

#the capture#bbc#holliday grainger#Joseph Arkley#deepfake#deep fake#politics#political#crime#drama#police#tech#technology#fake#fraud#business#office#corporate#ficus features#fiddle leaf fig#fiddle-leaf#fig#ficus lyrata#tree#trees#plant#plants#houseplant#houseplants#treeblr

1 note

·

View note

Text

this is living rent free in my head

(from the rsc 2019 measure for measure, with sophie khan levy as mariana, antony byrne as the duke, and joseph arkley as lucio)

#shakespeare#william shakespeare#measure for measure#plays#theatre#theater#the line read on ‘carnally she says’ kills me absolutely every time

17 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Royal Shakespeare Company: Taming of the Shrew (2019) - Petruchia (Claire Price) and Katherine (Joseph Arkley)

#shakespeare#claire price#joseph arkley#royal shakespeare company#genderswap#katherine petruchia and gremia are great in this one#bear in mind that the what the f* was mouthed in the bground#by me#gif#taming of the shrew#katherina x petruchio

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ah, Vienna...

Ah, Vienna…

MEASURE FOR MEASURE

Royal Shakespeare Theatre, Stratford upon Avon, Wednesday 7th August, 2019

Some people label this a ‘problem play’ and I have a problem with that. What it is is a dark comedy that deals with issues of morality. Here, director Gregory Doran has for the most part a light touch, so the comedy has the upper hand over the darkness. It’s definitely a production of two halves,…

View On WordPress

#Amanda Harris#Antony Byrne#Claire Price#David Ajao#Graeme Brookes#Gregory Doran#James Cooney#Joseph Arkley#Lucy Phelps#Measure For Measure#Michael Patrick#Patrick Brennan#Paul Englishby#review#Royal Shakespeare Theatre#RSC#Sandy Grierson#Stephen Brimson Lewis#Stratford upon Avon#William Shakespeare

0 notes

Photo

Measure For Measure- RSC 2019 review Review of the third of ther RSC's major 2019 Shakespeare productions, MEASURE FOR MEASURE (linked) directed by Greg Doran. A major version … but read my review. Picture: Sandy Grierson as Angelo.

#Amanda Harris#Antony Byrne#Claire Price#David Ajao#Graeme Brooks#Greg Doran#Jamres Cooney#Joseph Arkley#Lucy Phelps#Michael Patrick#Sandy Grierson#Tom Dawze

0 notes

Text

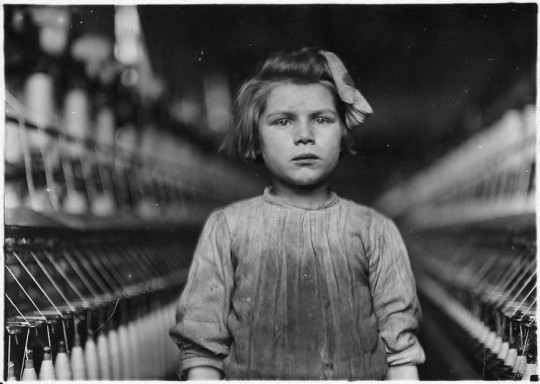

Britain's child slaves: They started at 4am, lived off acorns and had nails put through their ears for shoddy work. Yet, says a new book, their misery helped forge Britain.

The tunnel was narrow, and a mere 16in high in places. The workers could barely kneel in it, let alone stand. Thick, choking coal dust filled their lungs as they crawled through the darkness, their knees scraping on the rough surface and their muscles contracting with pain. A single 'hurrier' pulled the heavy cart of coal, weighing as much as 500lb, attached by a chain to a belt worn around the waist, while one or more 'thrusters' pushed from behind. Acrid water dripped from the tunnel ceiling, soaking their ragged clothes. Many would die from lung cancer and other diseases before they reached 25. For, shockingly, these human beasts of burden were children, some only five years old. Robert North, who worked in a coal mine in Yorkshire, told an inspector: 'I went into the pit at seven years of age. When I drew by the girdle and chain, my skin was broken and the blood ran down … If we said anything, they would beat us.' Another young hurrier, Patience Kershaw, had a bald patch on her head from years of pushing carts - often with her scalp pressed against them - for 11 miles a day underground. 'Sometimes they [the miners] beat me if I am not quick enough,' she said. The inspector described her as a 'filthy, ragged, and deplorable-looking object'. Others, like Sarah Gooder, aged eight, were used as 'trappers'. Crouching in the darkness of the tunnel wall, they waited to open trap doors which allowed the carts to travel through. 'I have to trap without a light and I'm scared,' she told the inspector. 'I go at four and sometimes half-past three in the morning, and come out at five-and-half-past … Sometimes I sing when I've light, but not in the dark. I don't like being in the pit.' His master threatened to 'knock out his brains' if he did not get up to work, and pushed him to the ground, breaking his thigh. Eventually, bent double and crippled, he returned to the workhouse, no longer any use to the brute. Most were exhausted by their working hours - they were often woken at 4am and carried, half-asleep, to the pits by their parents. Many young trappers were killed when they dozed off and fell into the path of the carts. Ten-year-old Joseph Arkley forgot to shut a trap door, allowing poisonous gas to seep into the tunnel. He died along with ten others in the resulting explosion. But coal mining was just one industry in which children worked during the 18th and 19th centuries. The Industrial Revolution brought immense prosperity to the British Empire. Not only did Britannia rule the waves, she ruled the global marketplace, too, dominating trade in cotton, wool and other commodities, while her inventors devised ingenious machinery to push productivity ever higher. But, as a new book by Jane Humphries, a professor of economic history, shows, a terrible price was paid for this success by the labourers who serviced the machines, pushed the coal carts and turned the wheels that drove the Industrial Revolution. Many of these labourers were children. With the mechanisation of Britain, traditional cottage industries, which had employed many poor families, went out of business. Consequently, more and more poverty-stricken workers were driven into the major cities and factories. The competition for jobs meant that wages were low, and the only way a poor family could fend off starvation was for the children to work as well. These were the real David Copperfields and Oliver Twists. Beaten, exploited and abused, they never knew what it was to have a full belly or a good night's sleep. Their childhood was over before it had begun. Using the heartbreaking first-person testimony of these child labourers, Humphries demonstrates that the brutality and deprivation depicted by authors such as Charles Dickens and Thomas Hardy was commonplace during the Industrial Revolution, and not just fictional exaggeration. She also reveals that more children were working

than previously thought - and at younger ages. As British productivity soared, more machines and factories were built, and so more children were recruited to work in them. During the 1830s, the average age of a child labourer officially was ten, but in reality some were as young as four. Many child scavengers lost limbs or hands, crushed in the machinery; some were even decapitated. Those who were maimed lost their jobs. In one mill near Cork there were six deaths and 60 mutilations in four years. While the upper classes professed horror at the iniquities of the slave trade, British children were regularly shackled and starved in their own country. The silks and cottons the upper classes wore, the glass jugs and steel knives on their tables, the coal in their fireplaces, the food on their plates - almost all of it was produced by children working in pitiful conditions on their doorsteps. But to many of the monied classes, the poor were invisible: an inhuman sub-species who did not have the same feelings as their own and whose sufferings were unimportant. If they spared a thought for them at all, it was nothing more than a shudder of revulsion at the filth and disease they carried. Living conditions were appalling. Families occupied rat and sewage-filled cellars, with 30 people crammed into a single room. Most children were malnourished and susceptible to disease, and life expectancy in such places fell to just 29 years in the 1830s. In these wretched circumstances, an extra few pennies brought home by a child would pay for a small loaf of bread or fuel for the fire: the difference between life and death. A third of poor households were without a male breadwinner, either as a result of death or desertion. In the broken Britain of the 19th century, children paid the price. One young boy, Thomas Sanderson, went out to work when his family was reduced to eating acorns they had foraged after his soldier father had been demobilised without a pension. Children were the ideal labourers: they were cheap (paid just 10-20 per cent of a man's wage) and could fit into small spaces such as under machinery and through narrow tunnels. But while parents sent their children to work with heavy hearts, the workhouses - where orphaned and abandoned children were deposited - had no such scruples. A child sent out to work was one mouth fewer to feed, so they were regularly sold to masters as 'pauper apprentices'. In exchange for board and lodging, they would work without wages until adulthood. If they ran away, they would be caught, whipped and returned to their master. Some were shackled to prevent them escaping, with 'irons riveted on their ankles, and reaching by long links and rings up to the hips, and in these they were compelled to walk to and fro from the mill to work and to sleep'. Orphaned Jonathan Saville was sold as a pauper apprentice to a master in a textile industry. His master threatened to 'knock out his brains' if he did not get up to work, and pushed him to the ground, breaking his thigh. Eventually, bent double and crippled, he was returned to the workhouse, no longer any use to the brute. Robert Blincoe - on whom Dickens' Oliver Twist is thought to be based - was sold, aged six, as a 'climbing boy' to a chimney sweep in London. Forced to scale the narrow chimneys, only 18in wide, he would scrape his elbows and knees on the brickwork and choke on coal dust. It was common for the master sweep to light a fire under them to make them climb faster. Many climbing boys and girls fell to their deaths. After several months, Blincoe was returned to the workhouse. Then, aged just seven, he was sent along with 80 other children to a cotton mill near Nottingham to work as a 'scavenger' - crawling under the machines to pick up bits of cotton, 14 hours a day, six days a week. In return, he was given porridge slops and black bread. Weak with hunger, at night he crept out to steal food from the mill owner's pigs. Many child scavengers lost limbs or hands, crushed in the machinery; some were even decapitated. Those who

were maimed lost their jobs. In one mill near Cork there were six deaths and 60 mutilations in four years. Blincoe was lucky: he only lost half a finger. A German visitor to Manchester in 1842 remarked that there were so many limbless people it was like 'living in the midst of an army just returned from campaign'. A doctor who observed mill workers noted that '… their complexion is sallow and pallid, with a peculiar flatness of feature, caused by the want of a proper quantity of adipose substance [fatty tissue], their stature low, a very general bowing of the legs … nearly all have flat feet'. The average height of the population fell in the 1830s as an overworked generation reached adulthood with knock-knees, humpbacks from carrying heavy loads and damaged pelvises from standing 14 hours a day. Girls who worked in match factories suffered from a particularly horrible disease known as phossy jaw. Children in glassworks were regularly burned and blinded by the intense heat, while the poisonous clay dust in potteries caused them to vomit and faint. Supervisors used terror and punishment to drive the children to greater productivity. A boy in a nail-making factory was punished for producing inferior nails by having his head down on an iron counter while someone 'hammered a nail through his ear, and the boy has made good nails ever since'. But despite the growth of cities, agriculture remained the biggest employer of children during the Industrial Revolution. While they might have escaped the deadly fumes and machinery of the factories, the life of a child farm labourer was every bit as brutal. Children as young as five worked in gangs, digging turnips from frozen soil or spreading manure. Many were so hungry that they resorted to eating rats. Children in glassworks were regularly burned and blinded by the intense heat, while the poisonous clay dust in potteries caused them to vomit and faint. The gangmaster walked behind them with a double rope bound with wax, and 'woe betide any boy who made what was called a "straight back" - in other words, standing up straight - before he reached the end of the field. The rope would descend sharply upon him'. Another favourite gangmaster's punishment was gibbeting: lifting a child off the ground by his neck, until his face turned black. And yet, many of these children showed extraordinary resilience and lack of resentment. Children who worked six days a week spent the seventh at Sunday school, determined to better themselves. But whenever anyone sought to improve children's working conditions, they encountered fierce opposition from the proprietors whose profits depended on exploiting them. They argued that any interference in the marketplace could cost Britain her manufacturing supremacy. Even when regulations were eventually passed to improve working conditions, with only four inspectors to police the thousands of factories across the country they were seldom enforced. In 1840 Lord Ashley, later Lord Shaftesbury, set up the Children's Employment Commission, interviewing hundreds of children in coalmines, works and factories. Its findings, reported in 1842, were deeply shocking. Many people had no idea that coal was excavated by young children. But it was the immorality rather than the cruelty of the mines that shocked them most. An inspector described how, 'The chain [used to pull the carts] passing high up between the legs of two girls, had worn large holes in their trousers. Any sight more disgustingly indecent or revolting can scarcely be imagined … No brothel can beat it.' An Act was passed, prohibiting women and children under ten from working underground. Two years later, another Act was passed prohibiting the textile industry from employing children younger than nine. But it was not until the mid-19th century that children were limited to a 12-hour day. In 1880, the Compulsory Education Act helped reduced the numbers of child labourers, and subsequent laws raised their age and made working conditions safer. But it had come too late for the little white slaves

on whose blood, sweat and toil our great railways, bridges and buildings of the Industrial Revolution were built. https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-1312764/Britains-child-slaves-New-book-says-misery-helped-forge-Britain.html#ixzz2ZKkYXGMW

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

David Ajao and Joseph Arkley, centre, in the RSC’s Measure for Measure. Photograph: Helen Maybanks.

“Byrne also gives unusual weight to the idea that, when it comes to women, the Duke “was not inclined that way”. The hint that he is a closeted figure makes his climactic marriage proposal, which leaves Phelps’s Isabella understandably aghast, seem all the more cynical.”

#shakespeare#william shakespeare#rsc#measure for measure#measure#royal shakespeare company#angelo#isabella

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

Such a FANTASTIC production of one of my favourite Shakespeare plays! Swapping the genders is both amusing and raises many issues over the ongoing gender inequality struggles. All of the actors are amazing but Joseph Arkley and Claire Price do a wonderful job as Katherine and Petruchia. Definitely recommend seeing if you get the chance! (Photo from the RSC twitter page)

#william shakespeare#shakespeare#the taming of the shrew#rsc#royal shakespeare company#stratford upon avon#comedy#review#gender#play#feminism

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Taming of the Shrew, RSC 2019 - Review

The Taming of the Shrew, RSC 2019 – Review

Kiss me, Kate.

Justin Audibert’s gender-swapped The Taming of the Shrew for the RSC is as entertaining as it is troubling: the matriarchal reworking turning Shakespeare’s comedy of misogyny into a palatable study of gender politics. Still a hard pill to swallow, its bitterness is offset by sweet and sugary comedy by the bucket load, and the result is something hugely entertaining.

The Elizabethan…

View On WordPress

#claire price#hannah clark#james cooney#joseph arkley#justin audibert#royal shakespeare company#rsc#ruth chan#shakespeare#sophie stanton

0 notes

Photo

NEW IN THE BOOKSHOP: ANYTHING GOES : Art In Australia 1970-1980 (1984) First printing of “Anything Goes : Art in Australia 1970-1980”, published by Art & Text in 1984. Edited by Paul Taylor, founder of Art & Text, this large, valuable volume of essays by leading writers of those years – covering all aspects of painting, sculpture, photography and experimental art forms since 1970 – features contributions by Janine Burks, Mary Eagle, Christine Godden, Robert Lindsay, Ian Burn, Julie Ewington, Memory Holloway, Terry Smith, Ann Stephen, Margaret Plant, Patrick McCaughey, Daniel Thomas. “The 1970s were years of unprecedented change in Australian art and culture, and Anything Goes is the first book about that decade’s remarkable variety of art.” Includes the work of: →↑→, Mike Parr, Howard Arkley, Jenny Watson, Donald Judd, Ian Burn, John Lethbridge, John Davis, Mel Bochner, Joseph Beuys, Mel Ramsden, Women’s Domestic Needlework Group, Andy Warhol, Tim Johnson, Nigel Lendon, Artsworkers Union, Robert Rooney, Clive Murray-White, Tony McGillick, Fred Williams, John Firth-Smith, George Haynes, Donald Laycock, Michael Taylor, Fred Cress, Ron Robertson-Swann, David Aspden, Sydney Ball, Roger Kemp, Paul Partos, Trevor Vickors, Robert Hunter, Robert Jacks, Vivienne Binns, Bonita Ely, Marie McMahon, Virginia Cuppaidge, Imants Tillers, Les Kossatz, Ti Parks, Peter Cripps, Ken Searle, Jan Senbergs, George Baldessin, John Armstrong, Janet Dawson, Dale Hickey, Tony Coleing, Marr Grounds, Chips Mackinolty, Ann Newmarch, Colin Little, Jan Mackay, Toni Robertson, Jenny Hill, Christo, Ross Grounds, Ken Unsworth, Kevin Mortensen, Stelarc, Jillian Orr, Hossein Valamanesh, W. Thomas Arthur, Ewa Pachucka, Vicki Varvaressos, Carol Jerrems, Elizabeth Gower, Geoff Hogg, Ann Newmarch, Peter Kennedy, Jon Rhodes, Bill Henson, Stephen Lojewski, Robert Owen, Mark Johnson, Peter Booth, John Duckley-Smith, Ron Robertson-Swann, Alun Leach-Jones, Michael Johnson, Lesley Dumbrell, Fred Cross, John Walker, David Aspden, and many more. One copy in the bookshop and via our website. #worldfoodbooks #petercripps #anythinggoes #1984 #paultaylor (at WORLD FOOD BOOKS)

7 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Liked on YouTube: "Sonnet 90 | Joseph Arkley | Sonnets in Solitude" https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HZ79T-hJS3A

0 notes

Text

Dave’s Faves for Sotheby’s Auction on 27 August 2019

Among the 87 lots offered at Sotheby's sale of Important Australian Art on 27 August, there are several multiple offerings from a number Australian masters and regulars at auction - including not surprisingly Arthur Boyd, Hans Heysen, Sidney Nolan, Arthur Streeton, Norman Lindsay and William Dobell.

More surprising perhaps is the appearance of four works by Cressida Campbell. But on reflection, given recent auction results demonstrating her status as the current darling of the contemporary art market, perhaps not so much.

There are some wonderful gems in this sale, and David has put them together for our "Dave's Faves" below.

You can view the paintings in person to get a true view:

- in Melbourne at 14-16 Collins Street, from 13 - 18 August

- in Sydney at 30 Queen Street, from 22 - 27 August.

The entire auction catalogue is of course available online at Sotheby's.

The auction is held on Tuesday, 27 August 2019, 6.30 pm at the Hotel Intercontinental in Sydney.

For independent advice and intelligent due diligence prior to purchasing, contact us if one (or more) artwork has caught your eye.

We will be attending the auction on the night, representing clients discreetly, and can therefore offer you a complete professional auction service prior, during and after the sale. Simply email us at [email protected] or phone 02 9977 7764 for more information.

So Dave's Faves for the Sotheby's Auction on 27 August in Sydney are:

[caption id="attachment_5791" align="alignleft" width="300"] Lot 1 - Brett Whiteley, Blue Painting 1960, 64.5 x 65.5 cm, est. $55,000-70,000. "Kind of Blue" (with a nod to Miles Davis)[/caption]

[caption id="attachment_5792" align="alignleft" width="158"] Lot 5 - John Olsen, Spring (2002), 191 x 100 cm, est. $60,000-80,000. Put a "Spring" in your Step[/caption]

[caption id="attachment_5793" align="alignleft" width="258"] Lot 6 - Fred Williams, You-Yangs Landscape (1966), 66 x 57 cm, est. $55,000-65,000. Yes, You-Yang![/caption]

[caption id="attachment_5795" align="alignleft" width="234"] Lot 13 - Howard Arkley, Rococo Rhythm 1992, 173.5 x 138.8 cm, est. $800,000-1,000,000. This is no time for a Captain Snooze[/caption]

[caption id="attachment_5794" align="alignleft" width="164"] Lot 7 - Cressida Campbell, Interior with Cat 2010, 92 x 50 cm, est. $100,000-120,000. Cat Got The Cream[/caption]

[caption id="attachment_5796" align="alignleft" width="247"] Lot 15 - Margaret Preston, Still Life 1917, 64.3 x 53.7 cm, est. $100,000-150,000. Oranges are not the only fruit[/caption]

[caption id="attachment_5797" align="alignleft" width="300"] Lot 20 - Arthur Streeton, Towong Gap (1930), 63.9 x 76.3 cm, est. $100,000-150,000. Is that a Model or a Model-T?[/caption]

[caption id="attachment_5798" align="alignleft" width="300"] Lot 22 - Ethel Carrick, The Market 1919, 75 x 100 cm, est. $1,200,000-1,600,000. Well, are you in the market or aren't you?[/caption]

[caption id="attachment_5799" align="alignleft" width="300"] Lot 29 - Eugene von Guerard, Lake Wakatipu, with Mount Earnslaw, New Zealand (1877), 34.7 x 62.1 cm, est. $100,000-150,000. Eugene at his Peak[/caption]

[caption id="attachment_5800" align="alignleft" width="242"] Lot 45 - Sidney Nolan, Kelly Study VI, 1962, 152.7 x 122 cm, est. $220,000-280,000. You might need to put up a fight for this one[/caption]

[caption id="attachment_5801" align="alignleft" width="300"] Lot 47 - Tim Storrier, Incendiary Line, 137 x 290 cm, est. $120,000-160,000. All Fired Up[/caption]

[caption id="attachment_5802" align="alignleft" width="231"] Lot 48 - Arthur Boyd, Shoalhaven with Cockatoo, 38.5 x 30.5 cm, est. $15,000-20,000. Cock-a-hoop Cockatoo[/caption]

[caption id="attachment_5803" align="alignleft" width="300"] Lot 53 - Arthur Boyd, Irrigation Lake, Wimmera (1980), 91.5 x 122 cm, est. $100,000-140,000. Back a Winner with Wimmera[/caption]

[caption id="attachment_5804" align="alignleft" width="300"] Lot 58 - Margaret Preston, Wheelflower (1929), 44 x 44.3 cm, est. $35,000-45,000. Not Wallflower - Wallpower![/caption]

[caption id="attachment_5805" align="alignleft" width="185"] Lot 59 - Cressida Campbell, Still Life with LIlies and Ranunculus (2006), 107 x 66.7 cm, est. $50,000-70,000. If you seek the Unique[/caption]

[caption id="attachment_5806" align="alignleft" width="300"] Lot 61 - Nora Heysen, A Study 1931, 47.5 x 53 cm, est. $30,000-40,000. Best Thing since Sliced Bread[/caption]

[caption id="attachment_5807" align="alignleft" width="300"] Lot 62 - Hans Heysen, Approaching Storm with Bushfire Haze 1913, 55 x 73 cm, est. $35,000-45,000. Bushies escape the Bushfire[/caption]

[caption id="attachment_5808" align="alignleft" width="300"] Lot 63 - Hans Heysen, White Gums. A Study, 30.2 x 38 cm, est. $2,000-3,000. Monochrome Magic for not much Money[/caption]

[caption id="attachment_5809" align="alignleft" width="226"] Lot 70 - Russell Drysdale, Man with Ram (1941), 30.3 x 22.7 cm, est. $25,000-35,000. Once owned by Dr. Joseph Brown[/caption]

[caption id="attachment_5810" align="alignleft" width="296"] Lot 71 - Sidney Nolan, Headland 1964, 122 x 122 cm, est. $60,000-80,000. One small Step for Sidney[/caption]

[caption id="attachment_5811" align="alignleft" width="300"] Lot 76 - Lin Onus, Guyi Buypuru (Fish and River Rock) (1995), 91 x 121.5 cm, est. $150,000-180,000. How Many "Likes" for Him?[/caption]

[caption id="attachment_5812" align="alignleft" width="300"] Lot 78 - William Robinson, Tea with Rock Cakes 2014, 30.7 x 35.7 cm, est. $25,000-35,000. Rockin' Robinson[/caption]

[caption id="attachment_5813" align="alignleft" width="300"] Lot 81 - Dale Frank, His Talent Was Like Being Stuck Behind a Long Vehicle 2012, 200 x 260 cm, est. $30,000-40,000. I rather like being stuck behind this long vehicle[/caption]

The post Dave’s Faves for Sotheby’s Auction on 27 August 2019 was originally seen on: https://www.bhfineart.com

0 notes

Text

THEATRE REVIEW: Richard III

THEATRE REVIEW: Richard III @HorsecrossPerth

With the width, depth and height of Perth Theatre fully exposed, the inner workings of the stage is laid bare for all to see: radiators to the rear, lighting rigs above, stage hands busying themselves in the wings.

Similarly, in Richard III, played with great gusto by Joseph Arkley who alternates between lounging lothario and clinical executioner at the drop of a curtain (of which there are many…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Perth * | Theatre review: Richard III

THE last time I saw Richard III – in Thomas Ostermeier's version at the 2016 Edinburgh Festival – he was played by Lars Eidinger, a remarkable actor who had done time as a DJ, among other work in the entertainment industry; and if Joseph Arkley's terrific performance in the same role at Perth Theatre ... https://ift.tt/2G88I9l

0 notes

Text

Shrewd Moves

THE TAMING OF THE SHREW

Royal Shakespeare Theatre, Thursday 2nd May, 2019

Gender-swapping is all the rage in theatre these days but if there’s a play where changing the men to women and vice versa actually makes a point about the world we live in, it’s this one, Shakespeare’s not-so-romantic comedy about conformity to gender roles. The setting is a matriarchy, instantly conjuring memories of…

View On WordPress

#Amanda Harris#Amelia Donkor#Amy Trigg#Claire Price#Emily Johnstone#Hannah Clark#James Cooney#Joseph Arkley#Justin Audibert#Laura Elsworthy#review#Royal Shakespeare Theatre#RSC#Ruth Chan#Sophie Stanton#The Taming of the Shrew#William Shakespeare

0 notes

Text

Britain's child slaves: They started at 4am, lived off acorns and had nails put through their ears for shoddy work. Yet, says a new book, their misery helped forge Britain.

The tunnel was narrow, and a mere 16in high in places. The workers could barely kneel in it, let alone stand.

Thick, choking coal dust filled their lungs as they crawled through the darkness, their knees scraping on the rough surface and their muscles contracting with pain.

A single 'hurrier' pulled the heavy cart of coal, weighing as much as 500lb, attached by a chain to a belt worn around the waist, while one or more 'thrusters' pushed from behind. Acrid water dripped from the tunnel ceiling, soaking their ragged clothes.

Many would die from lung cancer and other diseases before they reached 25. For, shockingly, these human beasts of burden were children, some only five years old.

Robert North, who worked in a coal mine in Yorkshire, told an inspector: 'I went into the pit at seven years of age. When I drew by the girdle and chain, my skin was broken and the blood ran down … If we said anything, they would beat us.'

Another young hurrier, Patience Kershaw, had a bald patch on her head from years of pushing carts - often with her scalp pressed against them - for 11 miles a day underground. 'Sometimes they [the miners] beat me if I am not quick enough,' she said.

The inspector described her as a 'filthy, ragged, and deplorable-looking object'.

Others, like Sarah Gooder, aged eight, were used as 'trappers'. Crouching in the darkness of the tunnel wall, they waited to open trap doors which allowed the carts to travel through.

'I have to trap without a light and I'm scared,' she told the inspector. 'I go at four and sometimes half-past three in the morning, and come out at five-and-half-past … Sometimes I sing when I've light, but not in the dark. I don't like being in the pit.'

His master threatened to 'knock out his brains' if he did not get up to work, and pushed him to the ground, breaking his thigh. Eventually, bent double and crippled, he returned to the workhouse, no longer any use to the brute.

Most were exhausted by their working hours - they were often woken at 4am and carried, half-asleep, to the pits by their parents.

Many young trappers were killed when they dozed off and fell into the path of the carts. Ten-year-old Joseph Arkley forgot to shut a trap door, allowing poisonous gas to seep into the tunnel. He died along with ten others in the resulting explosion.

But coal mining was just one industry in which children worked during the 18th and 19th centuries.

The Industrial Revolution brought immense prosperity to the British Empire. Not only did Britannia rule the waves, she ruled the global marketplace, too, dominating trade in cotton, wool and other commodities, while her inventors devised ingenious machinery to push productivity ever higher.

But, as a new book by Jane Humphries, a professor of economic history, shows, a terrible price was paid for this success by the labourers who serviced the machines, pushed the coal carts and turned the wheels that drove the Industrial Revolution.

Many of these labourers were children. With the mechanisation of Britain, traditional cottage industries, which had employed many poor families, went out of business. Consequently, more and more poverty-stricken workers were driven into the major cities and factories.

The competition for jobs meant that wages were low, and the only way a poor family could fend off starvation was for the children to work as well.

These were the real David Copperfields and Oliver Twists. Beaten, exploited and abused, they never knew what it was to have a full belly or a good night's sleep. Their childhood was over before it had begun.

Using the heartbreaking first-person testimony of these child labourers, Humphries demonstrates that the brutality and deprivation depicted by authors such as Charles Dickens and Thomas Hardy was commonplace during the Industrial Revolution, and not just fictional exaggeration.

She also reveals that more children were working than previously thought - and at younger ages.

As British productivity soared, more machines and factories were built, and so more children were recruited to work in them. During the 1830s, the average age of a child labourer officially was ten, but in reality some were as young as four.

Many child scavengers lost limbs or hands, crushed in the machinery; some were even decapitated. Those who were maimed lost their jobs. In one mill near Cork there were six deaths and 60 mutilations in four years.

While the upper classes professed horror at the iniquities of the slave trade, British children were regularly shackled and starved in their own country. The silks and cottons the upper classes wore, the glass jugs and steel knives on their tables, the coal in their fireplaces, the food on their plates - almost all of it was produced by children working in pitiful conditions on their doorsteps.

But to many of the monied classes, the poor were invisible: an inhuman sub-species who did not have the same feelings as their own and whose sufferings were unimportant. If they spared a thought for them at all, it was nothing more than a shudder of revulsion at the filth and disease they carried.

Living conditions were appalling. Families occupied rat and sewage-filled cellars, with 30 people crammed into a single room. Most children were malnourished and susceptible to disease, and life expectancy in such places fell to just 29 years in the 1830s. In these wretched circumstances, an extra few pennies brought home by a child would pay for a small loaf of bread or fuel for the fire: the difference between life and death.

A third of poor households were without a male breadwinner, either as a result of death or desertion. In the broken Britain of the 19th century, children paid the price.

One young boy, Thomas Sanderson, went out to work when his family was reduced to eating acorns they had foraged after his soldier father had been demobilised without a pension.

Children were the ideal labourers: they were cheap (paid just 10-20 per cent of a man's wage) and could fit into small spaces such as under machinery and through narrow tunnels.

But while parents sent their children to work with heavy hearts, the workhouses - where orphaned and abandoned children were deposited - had no such scruples. A child sent out to work was one mouth fewer to feed, so they were regularly sold to masters as 'pauper apprentices'.

In exchange for board and lodging, they would work without wages until adulthood. If they ran away, they would be caught, whipped and returned to their master.

Some were shackled to prevent them escaping, with 'irons riveted on their ankles, and reaching by long links and rings up to the hips, and in these they were compelled to walk to and fro from the mill to work and to sleep'.

Orphaned Jonathan Saville was sold as a pauper apprentice to a master in a textile industry. His master threatened to 'knock out his brains' if he did not get up to work, and pushed him to the ground, breaking his thigh. Eventually, bent double and crippled, he was returned to the workhouse, no longer any use to the brute.

Robert Blincoe - on whom Dickens' Oliver Twist is thought to be based - was sold, aged six, as a 'climbing boy' to a chimney sweep in London.

Forced to scale the narrow chimneys, only 18in wide, he would scrape his elbows and knees on the brickwork and choke on coal dust.

It was common for the master sweep to light a fire under them to make them climb faster. Many climbing boys and girls fell to their deaths. After several months, Blincoe was returned to the workhouse. Then, aged just seven, he was sent along with 80 other children to a cotton mill near Nottingham to work as a 'scavenger' - crawling under the machines to pick up bits of cotton, 14 hours a day, six days a week.

In return, he was given porridge slops and black bread. Weak with hunger, at night he crept out to steal food from the mill owner's pigs.

Many child scavengers lost limbs or hands, crushed in the machinery; some were even decapitated. Those who were maimed lost their jobs. In one mill near Cork there were six deaths and 60 mutilations in four years. Blincoe was lucky: he only lost half a finger.

A German visitor to Manchester in 1842 remarked that there were so many limbless people it was like 'living in the midst of an army just returned from campaign'. A doctor who observed mill workers noted that '… their complexion is sallow and pallid, with a peculiar flatness of feature, caused by the want of a proper quantity of adipose substance [fatty tissue], their stature low, a very general bowing of the legs … nearly all have flat feet'.

The average height of the population fell in the 1830s as an overworked generation reached adulthood with knock-knees, humpbacks from carrying heavy loads and damaged pelvises from standing 14 hours a day. Girls who worked in match factories suffered from a particularly horrible disease known as phossy jaw.

Children in glassworks were regularly burned and blinded by the intense heat, while the poisonous clay dust in potteries caused them to vomit and faint.

Supervisors used terror and punishment to drive the children to greater productivity. A boy in a nail-making factory was punished for producing inferior nails by having his head down on an iron counter while someone 'hammered a nail through his ear, and the boy has made good nails ever since'.

But despite the growth of cities, agriculture remained the biggest employer of children during the Industrial Revolution. While they might have escaped the deadly fumes and machinery of the factories, the life of a child farm labourer was every bit as brutal.

Children as young as five worked in gangs, digging turnips from frozen soil or spreading manure. Many were so hungry that they resorted to eating rats.

Children in glassworks were regularly burned and blinded by the intense heat, while the poisonous clay dust in potteries caused them to vomit and faint.

The gangmaster walked behind them with a double rope bound with wax, and 'woe betide any boy who made what was called a "straight back" - in other words, standing up straight - before he reached the end of the field. The rope would descend sharply upon him'.

Another favourite gangmaster's punishment was gibbeting: lifting a child off the ground by his neck, until his face turned black. And yet, many of these children showed extraordinary resilience and lack of resentment. Children who worked six days a week spent the seventh at Sunday school, determined to better themselves.

But whenever anyone sought to improve children's working conditions, they encountered fierce opposition from the proprietors whose profits depended on exploiting them. They argued that any interference in the marketplace could cost Britain her manufacturing supremacy.

Even when regulations were eventually passed to improve working conditions, with only four inspectors to police the thousands of factories across the country they were seldom enforced.

In 1840 Lord Ashley, later Lord Shaftesbury, set up the Children's Employment Commission, interviewing hundreds of children in coalmines, works and factories. Its findings, reported in 1842, were deeply shocking.

Many people had no idea that coal was excavated by young children. But it was the immorality rather than the cruelty of the mines that shocked them most.

An inspector described how, 'The chain [used to pull the carts] passing high up between the legs of two girls, had worn large holes in their trousers. Any sight more disgustingly indecent or revolting can scarcely be imagined … No brothel can beat it.'

An Act was passed, prohibiting women and children under ten from working underground. Two years later, another Act was passed prohibiting the textile industry from employing children younger than nine.

But it was not until the mid-19th century that children were limited to a 12-hour day.

In 1880, the Compulsory Education Act helped reduced the numbers of child labourers, and subsequent laws raised their age and made working conditions safer. But it had come too late for the little white slaves on whose blood, sweat and toil our great railways, bridges and buildings of the Industrial Revolution were built.

https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-1312764/Britains-child-slaves-New-book-says-misery-helped-forge-Britain.html#ixzz2ZKkYXGMW

21 notes

·

View notes