#joris ivens

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

17th Parallel: The People's War, Joris Ivens / Marceline Loridan (1968)

520 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Bon Soir 🗼👌 🗼

"La Seine a rencontré Paris"

✒️ Jacques Prévert

📷 André Dumaître

🎶 Philippe Gérard

🗣 Serge Reggiani

🎥 Joris Ivens...extrait du court métrage Palme d'or Cannes 1958

#clip movie#la seine a rencontré paris#jacques prévert#poème#paris#seine#serge reggiani#philippe gérard#joris ivens#court métrage#andré dumaître#quai de seine#fidjie fidjie#Youtube

24 notes

·

View notes

Photo

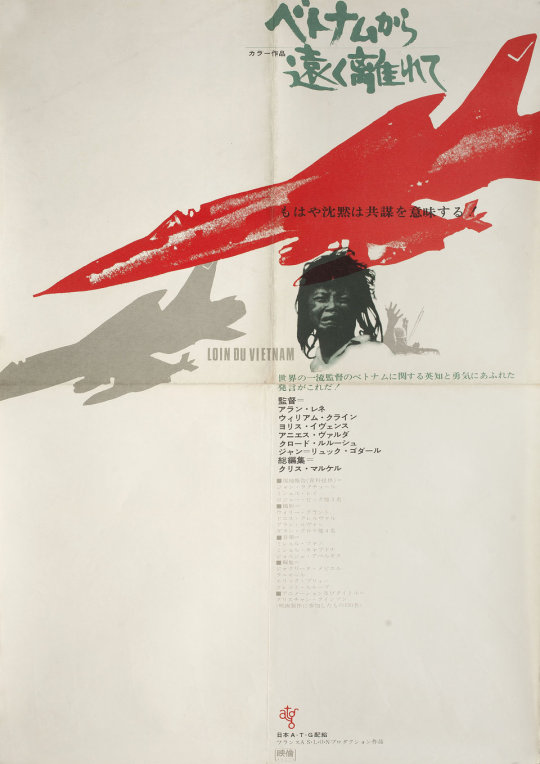

Far from Vietnam (1967, directed by Joris Ivens, William Klein, Claude Lelouch, Agnes Varda, Jean-Luc Godard, Chris Marker, and Alain Resnais). Movie poster designed by Kiroku Higaki

#alain resnais#chris marker#jean luc godard#agnes varda#claude lelouch#william klein#joris ivens#film#movie posters#kiroku higaki#vietnam#red

78 notes

·

View notes

Text

…A Valparaíso (1963) dir. Joris Ivens

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Joris Ivens, November 18, 1898 – June 28, 1989.

With Agnès Varda.

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

Seen in 2023:

. . . A Valparaiso (Joris Ivens), 1963

#films#movies#stills#shorts#docs#documentary#A Valparaiso#Joris Ivens#essay films#Chile#1960s#seen in 2023

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

La giovane schizofrenica avverte i suoi «primi sentimenti d’irrealtà» davanti a due immagini: quella di una compagna che si avvicina e il cui volto si ingrandisce esageratamente (si direbbe un leone); quella di un campo di grano che diventa illimitato, «immensità dorata, luminosa”. Ecco, rifacendosi alla terminologia di Peirce, come risulteranno i due segni dell’immagine-affezione: Icona per l’espressione di una qualità-potenza operata da un volto, Qualisegno (oppure Potisegno) per la sua presentazione in uno spazio qualsiasi. Certi film di Joris Ivens ci danno un’idea di cosa sia un qualisegno: in Regen, «la pioggia che si vede nel film non è quella data pioggia, concreta e determinata, caduta un certo giorno e in un certo luogo. Queste impressioni visive non sono raccolte in unità da alcuna figurazione spaziale o temporale. Con estrema sensibilità, Ivens ha scoperto non come la pioggia è in realtà, ma che cosa accade (e in qual modo) quando la pioggerella primaverile batte sulle foglie degli alberi, quando lo specchio dello stagno rabbrividisce, quando una goccia solitaria cerca esitando la sua via su una lastra di vetro, quando la vita di una metropoli si riflette sull’umido asfalto. […] Anche quando Ivens ci mostra un ponte, da lui stesso indicato come il grande viadotto ferroviario di Rotterdam (Il ponte), la costruzione di ferro si dissolve in immagini immateriali inquadrate in cento modi diversi. Basta il fatto che questo ponte possa essere visto in tanti modi per renderlo in un certo senso irreale. Esso non ci appare come l’opera concreta degli ingegneri che lo costruirono, ma come una serie di curiosi effetti ottici. Si tratta insomma di variazioni visive sulle quali ben difficilmente potrebbe transitare un treno merci». Non è un concetto di ponte, ma non è nemmeno l’individuato stato di cose definito dalla sua forma, dalla sua materia metallica, dai suoi usi e funzioni. È una potenzialità. Il rapido montaggio dei settecento piani-inquadrature fa sí che le diverse vedute possano raccordarsi in un’infinità di modi e, non essendo orientate le une in rapporto alle altre, costituiscono l’insieme delle singolarità che si coniugano nello spazio qualsiasi in cui questo ponte appare come pura qualità, questo metallo come pura potenza, la stessa Rotterdam come affetto. E neanche la pioggia è il concetto di pioggia, o lo stato di un tempo e di un luogo piovosi. È piuttosto un insieme di singolarità che presenta la pioggia cosí com’è in sé, pura potenza o qualità che coniuga senza astrazione tutte le piogge possibili, e compone il corrispondente spazio qualsiasi. È la pioggia come affetto, e niente si oppone maggiormente a un’idea astratta o generale, pur non essendo attualizzata in uno stato di cose individuale.

Gilles Deleuze

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

From Joseph Losey

[Mexico City,] 17 September 1971

Dear Buñuel, It has been more than thirty-five years since we met. Perhaps you will remember coming to my house in New York on several occasions, having been sent to me by our mutual friend, Joris Ivens. I still see Joris, and it is strange that with him and our many other mutual friends, from poor George Pepper to Jeanne Moreau, that we never seem to have encountered each other in the intervening years.

As you perhaps have seen, I am here shooting locations of a picture about the assassination of Trotsky, and I understand that you are now in Mexico. It would be pleasant to greet you, if you have a few minutes. If you feel like it, do drop me a note or give me a ring, and perhaps we can have a brief drink one evening after shooting. I am scheduled to leave on 29 September.

Sincerely yours, Joseph Losey

Jo Evans & Breixo Viejo, Luis Buñuel: A Life in Letters

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

De peperbus van nonkel Miele (80): het strategische belang van de industrie

Iedereen weet nog hoe we bij het begin van de covid-pandemie eenvoudige mondmaskers moesten invoeren uit het verre Azië. Het was de perversiteit van de de-industrialisering, het industrieel verval. Een gevolg van de neoliberale globalisering. Waanzinnig is het failliet van de Vlaamse busbouwer Van Hool begin dit jaar en de sluiting van Audi-Brussel. Hier en in andere bedrijven komen alle…

#Bart Van Malderen#Brian Thompson#Frank Van Hool#Joris Ivens#Ken Loach#leonardo dicaprio#Martin Scorsese#Stijn Coninx#Warren Buffett

0 notes

Text

Le Giornate del Cinema Muto 2024: Pordenone Post No 7

Blood, sweat and tears on the screen today. And to cap it all off, prizes! That’s Friday in Pordenone, folks. Read all about it. Your scribe is a little squeamish, I must confess, so this morning I had to resort to an old trick, and pop my glasses off during some of Arabi (Nadezhda Zubova, 1933), a drama about sheep farmers organising to form a collective and defeat the feudal powers that…

#Anna May Wong#Ben Carré#BFI#Bryony Dixon#featured#GCM43#Giornate del Cinema Muto#Herbert Blaché#Joris Ivens#Nadezhda Zubova#Pordenone Silent Film Festival#Robert Wiene#silent film

1 note

·

View note

Text

17th Parallel: The People's War, Joris Ivens / Marceline Loridan (1968)

58 notes

·

View notes

Text

Plaque en hommage à : Marceline Loridan-Ivens et Joris Ivens

Type : Lieu de résidence

Adresse : 61 rue des Saints-Pères, 75006 Paris, France

Date de pose : 2019 (délibération) [source]

Texte : Ici vécurent de 1964 à leur décès Marceline LORIDAN-IVENS née ROZENBERG, 1928-2018, déportée à Auschwitz-Birkenau à l'âge de 16 ans, matricule 78750, et Joris IVENS, 1898-1989, surnommé "le Hollandais volant", Cinéastes et Écrivains

Quelques précisions : Marceline Loridan-Ivens (1928-2018) et Joris Ivens (1898-1989) sont un couple de cinéastes, la première française, le second néerlandais. Marceline, en raison de ses origines juives, est arrêtée pendant la Seconde Guerre mondiale et déportée à Auschwitz, où elle nouera une solide amitié avec Simone Veil. Survivant à la guerre, elle se tourne vers le militantisme politique, avant de se tourner vers le monde du cinéma. C'est par ce biais qu'elle rencontre Joris, qu'elle épousera malgré les trente ans qui les séparent. Tous deux réaliseront par exemple Le 17e parallèle (1968), un film sur la guerre du Vietnam, ainsi qu'une série de documentaires controversés sur la révolution culturelle chinoise. Avant de rencontrer Marceline, Joris avait déjà réalisé de nombreux documentaires et plusieurs films de propagande (mais peu furent diffusés en France), et il recevra le Lion d'Or en 1988 pour l'ensemble de sa carrière. Après la mort de son époux, Marceline rédige plusieurs publications sur la Shoah et ses conséquences, dont une autobiographie, Et tu n'es pas revenu (2015), qui lui vaudra le prix Jean-Jacques Rousseau.

#collectif#couple#residence#artistes#cineastes#france#ile de france#paris#marceline loridan ivens#joris ivens#datee

1 note

·

View note

Text

…A Valparaíso, Joris Ivens (1963)

0 notes

Photo

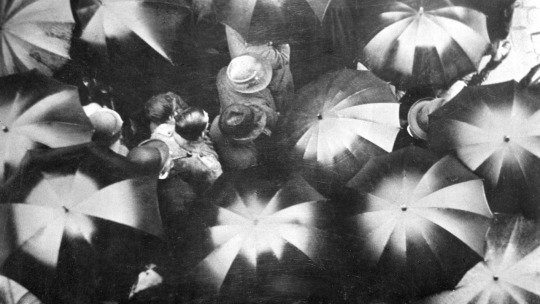

A Tale of the Wind (1988)

A Tale of the Wind (Joris Ivens and Marceline Loridan, 1988)

114 notes

·

View notes

Text

Joris Ivens, November 18, 1898 – June 28, 1989.

5 notes

·

View notes