#john madden director

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

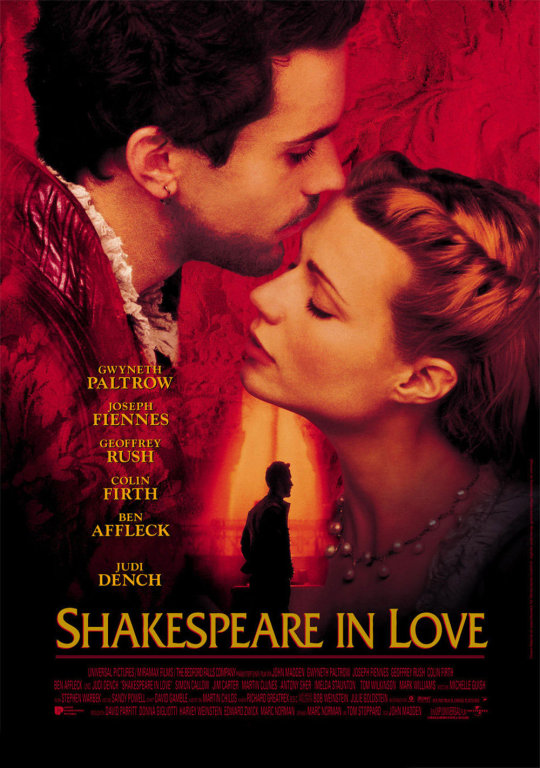

Shakespeare in Love (1998)

Movie #1,084 • FRIDAY FILL-IN

This came out 2 years and 9 months before 9/11. There's no way to say if this was a coincidence or not and I am no way insinuating that the release of Shakespeare in Love had anything to do with the towers falling on that fateful day. But facts are facts.

Look, I don't have much to say about this. When I reviewed the very blah Captain Corelli's Mandolin for The Year of Cage project, I thought it was funny that it was Coach John Madden's follow-up to this Oscar-slaying "little movie that could." It's also funny that, at the time, this was scene as such an underdog, because it seems EXACTLY like the type of movie that would clean up at the Academy Awards when viewed today. This is all to say that it's completely fine. It's not my bag but I could totally see how and why it would be someone's favorite film of all-time. I was also struck by its tone, which is explicitly going for a romcom vibe. In my memory, it was a much more serious movie but honestly if that had been the case, it probably would have been even worse.

SCORE: ⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️½

#john madden director#1998#romcom#gwyneth paltrow#joseph fiennes#geoffrey rush#colin firth#ben affleck#judi dench#simon callow#jim carter#martin clunes#antony sher#imelda staunton#tom wilkinson#mark williams#🇺🇸#🇬🇧#5.5

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kenneth Tynan and the Beatles

Shout out to @mmgth for noticing Beatle mentions in the letters of Kenneth Tynan - including working with John Lennon, Paul's 1960s reputation, and glimpses of the breakup. (Alas, no George or Ringo.)

Tynan was a drama critic and later worked with Laurence Olivier at Britain's National Theatre. Philip Norman calls him "the most rigorous cultural commentator of his age": he championed working class plays in the 1950s, supported progressive art (and was widely believed to be the first person to say "fuck" on British television). So he's an interesting perspective: well connected, arty, eager for cultural change, but from an older generation, and outside the immediate rock/pop world.

The first mention is 1966, when Tynan is already working at the National Theatre.

28 September 1966

Dear Mr McCartney,

Playing 'Eleanor Rigby' last night for about the 500th time, I decided to write and tell you how terribly sad I was to hear that you had decided not to do As You Like It for us. There are four or five tracks on 'Revolver' that are as memorable as any English songs of this century - and the maddening thing is that they are all in exactly the right mood for As You like It. Apart from 'E. Rigby' I am thinking particularly of 'For No One' and 'Here, There and Everywhere'. (Incidentally, 'Tomorrow Never Knows' is the best musical evocation of L.S.D. I have ever heard).

To come to the point: won't you reconsider? John Dexter [theatre director] doesn't know I'm writing this - it's pure impulse on the part of a fan. We don't need you as a gimmick because we don't need publicity: we need you simply because you are the best composer of that kind of song in England. If Purcell were alive, we would probably ask him, but it would be a close thing. Anyway, forgive me for being a pest, but do please think it over."

Paul replied that he couldn't do the music because, hilariously, "I don't really like words by Shakespeare" - he sat waiting for a "clear light" but nothing happened. He ended, "Maybe I could write the National Theatre Stomp sometime! Or the ballad of Larry O."

It's interesting that Tynan approaches Paul individually - because they had theatre connections in common? Or did Tynan assume that John wrote the words and Paul the music, so Paul's the guy to ask for settings of Shakespeare lyrics? (Though he does correctly identify Paul songs in his letter, plus the musical setting of Tomorrow Never Knows, so he might just be asking because he's a Paul girl. He also wants Paul to know that he's cool and hip and has done acid.)

Tynan definitely is a Paul girl. On 7 November that year, he pitched possible articles (I think for Playboy). He offers articles on the War Crimes Tribunal (set up by Bertrand Russell on the US in Vietnam), an interview with Marlene Dietrich, or:

"Interview with Paul McCartney - to me, by far the most interesting of the Beatles, and certainly the musical genius of the group."

It's a reminder of how drastically Paul's reputation changed, between cultural commentators of the 1960s and post-breakup.

Tynan didn't get his Paul interview, but he worked twice with John.

On 5 February 1968, he's sorting out practical details for the National Theatre's company manager about about the stage adapation of John's book In His Own Write (which had already had a preview performance in 1967). It's a very Beatle-y affair:

Victor Spinetti and John Lennon will need the services of George Martin, the Beatles A & R man to prepare a sound tape to accompany the Lennon play. Martin did this tape as a favour for the Sunday night production, but something more elaborate will be required when the show enters the rep, and I feel he should be approached on a professional basis as Sound Consultant, or some similar title. I have written to him to find out if he is ready to help and will let you know as soon as he replies.

...John Lennon says that as far as his own contract is concerned, we should deal directly with him at NEMS rather than his publisher.

So John prefers to work within the Beatle structure: George Martin, Victor Spinetti, plus NEMS, rather than pursuing closer ties with his book publisher.

On 16 April 1968, Tynan writes to John about his ideas for a wanking sketch.

Dear John L,

Welcome back. You know that idea of yours for my erotic revue - the masturbation contest? Could you possibly be bothered to jot it down on paper? I am trying to get the whole script in written form as soon as possible.

John's reply is very John:

"you know the idea, four fellows wanking - giving each other images - descriptions - it should be ad-libbed anyway - they should even really wank which would be great..."

Oh John.

Tynan still wanted to interview Paul - and was noticing changes in Beatle dynamics. On 3 September 1968, Tynan pitched another feature on Paul, this time for the New Yorker:

In addition to pieces on theatre, I'd love to try my hand at a profile (I remember long ago we vaguely discussed Paul McCartney though John Lennon is rather more accessible)...

Accessible because Tynan had already worked with him, or because John was already flexing his PR muscles? The New Yorker was interested, because Tynan follows up on 14 October 1968:

4. A few days in the life of Paul McCartney (which we agreed should come at the end of the series of articles, because of the current overexposure of the Beatles.)

Why does he see the Beatles as "overexposed" in autumn 1968, when he hadn't in 1966? Was it the Apple launch? The JohnandYoko press campaign? The cumulative impact of a lot of Beatle news?

Tynan was still trying on 17 September 1969:

...I'd like to go on to either Mr Pinter [playwright Harold Pinter] or Paul McCartney... I incline towards McCartney who has isolated himself more and more in the past from the other Beatles and indeed from the public: he seems to have reached an impasse that might be worth exploring. On the other hand Pinter is a much closer friend and would be more accessible to intimate scrutiny."

I'm fascinated by this - that Paul's isolation was visible to those outside the Beatles circle (the letter is dated three days before the meeting of 20 September 1969, where John said he wanted a divorce).

But Tynan was right about Paul being inaccessible. On 5 January 1970:

I'm saddened to have to tell you that Paul McCartney doesn't want to be written about at the moment - at least, not by me. I gather that for some time now the Beatles have been moving more and more in separate directions. Paul went to a recording session for a new single last Sunday which was apparently the first Beatles activity in which he'd engaged for nearly nine months. He doesn't know quite where his future lies, and above all he doesn't want to be under observation while he decides.

So while Paul "doesn't want to be under observation", he's surprisingly open about the breakup - less blunt than "the Beatle thing is over", which he told Life in November 1969, but still frank.

Trying to persuade Paul to open up to "intimate scrutiny" in 1969 does suggest another reason why 1970s interviewers adored John. Tynan works for an older, more established press, but he's offering the kind of profile John would make his own - discussing his inner life and personal/artistic conflicts with cultural commentator who respects him as an artist. And Paul can't run away fast enough. As a journalist, you'd absolutely go for the guy who makes himself accessible and is eager to bare his soul, over Mr Doesn't Want To Be Written About At The Moment.

#kenneth tynan#the breakup#john lennon#paul mccartney#george martin#victor spinetti#oh! calcutta#john's pr genius is so underrated#tag for mine or my addition

67 notes

·

View notes

Text

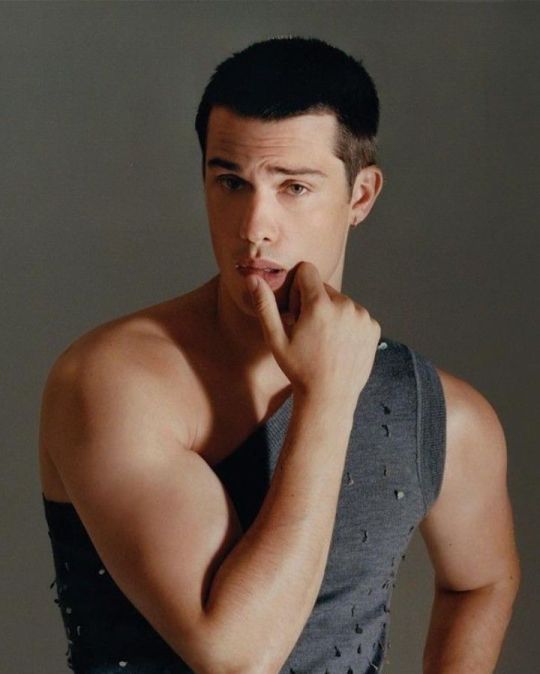

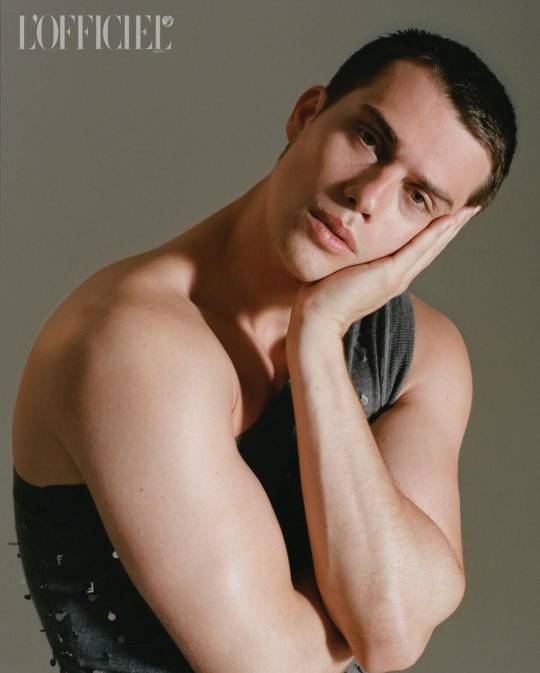

UK actors are having a moment!

-Hero Fiennes Tiffin late of Guy Ritchie's THE MINISTRY OF UNGENTLEMANLY WARFARE

is reporting back to Ritchie for the direct to series order for Amazon Prime's YOUNG SHERLOCK HOLMES.

Will Fiennes Tiffin's Holmes be the young version of Robert Downey Jr's Sherlock Holmes that Ritchie famously directed? By Ritchie's comments, I'm thinking the two are unrelated. "In ‘Young Sherlock’ we’re going to see an exhilarating new version of the detective everyone thinks they know in a way they’ve never imagined before,” said Ritchie. “We’re going to crack open this enigmatic character, find out what makes him tick, and learn how he becomes the genius we all love.”

The Fiennes' family are no stranger to the Holmes universe. Hero's uncle Ralph Fiennes played Moriarty in the 2018 comedy HOLMES & WATSON starring Will Ferrell and John C. Reilly.

-Nicholas Galitzine has a hit Amazon film, hit songs on the chart, he's in FYC campaigns for both Amazon's RED WHITE AND ROYAL BLUE and Starz/Sky Atlantic's MARY & GEORGE and now he can put action hero under his belt. Galitzine has been tapped for the role they have seemingly been unable to give away - He-Man, Master of the Universe!

I know. Shocking.

It has been a hard road getting this property back into the live-action realm. Previously cast was Noah Centineo,

then bewildering Kyle Allen (WEST SIDE STORY, A HAUNTING IN VENICE)

and just slightly less bewildering Galitzine.

Thicc Nick. Get those muscles back up, Prince Adam, the People's Princess.

While the articles I've seen announcing Galitzine's casting say that the plot details are unknown, the film is still being directed by Travis Knight (BUMBLEBEE, KUBO AND THE TWO STRINGS) and when he was announced as director the synopsis was: “10-year-old Prince Adam who crashed to Earth in a spaceship and was separated from his magical Power Sword—the only link to his home on Eternia. After tracking it down almost two decades later, Prince Adam is whisked back across space to defend his home planet against the evil forces of Skeletor. But to defeat such a powerful villain, Prince Adam will first need to uncover the mysteries of his past and become He-Man: the most powerful man in the Universe!”

Until then, you can see Galitzine in Variety's ACTORS ON ACTORS (in support of MARY & GEORGE) where he is paired with Leo Woodall, (ONE DAY) and who will be in the next BRIDGET JONES film, BRIDGET JONES: MAD ABOUT THE BOY.

Galitzine's RED, WHITE AND ROYAL BLUE costar Taylor Zakhar Perez will also be in ACTORS ON ACTORS and is paired with his friend and THE KISSING BOOTH costar Joey King (WE WERE THE LUCKY ONES).

The rest of the lineup

Quinta Brunson (“Abbott Elementary”) & Jennifer Aniston (“The Morning Show”)

Jodie Foster (“True Detective: Night Country”) & Robert Downey Jr. (“The Sympathizer”)

Jon Hamm (“Fargo,” “The Morning Show”) & Kristen Wiig (“Palm Royale”)

Tyler James Williams (“Abbott Elementary”) & Anthony Mackie (“Twisted Metal”)

Anna Sawai (“Shōgun “) & Tom Hiddleston (“Loki”)

Brie Larson (“Lessons in Chemistry”) & Andrew Scott (“Ripley”)

Hannah Einbinder (“Hacks”) & Chloe Fineman (“Saturday Night Live”)

Elizabeth Debicki (“The Crown”) & Emma Corrin (“A Murder at the End of the World”)

Chloë Sevigny (“Feud: Capote vs. The Swans”) & Kim Kardashian (“American Horror Story: Delicate”)

Naomi Watts (“Feud: Capote vs. The Swans”) & Jonathan Bailey (“Fellow Travelers”)

-As Travis Knight has directed a TRANSFORMERS film, I move on to a TRANSFORMERS alum - Jack Reynor who was in the panned TRANSFORMERS: AGE OF EXTINCTION. Dear Jack has been cast in series two of AppleTV+s CITADEL opposite Priyanka Chopra and Richard Madden.

and another dear Jack, this time Jack "The Lad" O'Connell, who was recently seen in Michael Mann's FERRARI and Sam Taylor Johnson's Amy Winehouse biopic BACK TO BLACK has been cast in the next Ryan Coogler and Michael B. Jordan collaboration (which is said to be a vampire film) and he's been cast in the upcoming 28 DAYS LATER sequel with Cillian Murphy, Jodie Comer, Aaron Taylor Johnson and Ralph Fiennes.

#nicholas galitzine#nick galitzine#taylor zakhar perez#rwrb movie#rwrb#mary & george#red white and royal blue#emmys 2024#awards season#he man#master of the universe#kyle allen#noah centineo#hero fiennes tiffin#he man master of the universe#jack reynor#jack o'connell#28 days later#actors on actors#sherlock holmes#young sherlock holmes#uk actors

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Title: Shakespeare in Love

Rating: R

Director: John Madden

Cast: Joseph Fiennes, Gwyneth Paltrow, Geoffrey Rush, Tom Wilkinson, Judi Dench, Imelda Staunton, Colin Firth, Ben Affleck, Simon Callow, Steven Beard, Jim Carter, Rupert Everett, Martin Clunes, Tim McMullan, Joe Roberts, Antony Sher, Georgie Glen

Release year: 1998

Genres: romance, comedy, history

Blurb: Young Shakespeare is forced to stage his latest comedy, Romeo and Ethel, the Pirate's Daughter, before it's even written. When a lovely noblewoman auditions for a role, they fall into forbidden love, and his play finds a new life (and title). As their relationship progresses, Shakespeare's comedy soon transforms into a tragedy.

#shakespeare in love#r#john madden#joseph fiennes#gwyneth paltrow#geoffrey rush#tom wilkinson#judi dench#1998#romance#comedy#history

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

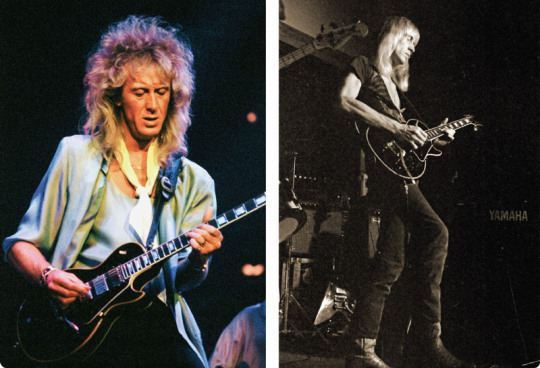

Happy Birthday musician Davey Johnstone, who forged a career of over 50 years as Elton John;s guitarist.

Born David William Logan Johnstone on this day 1951 in Edinburgh, Davey was having a perfectly fine career in the folk music world before he was whisked away to a life of rock and roll with one of the worlds biggest “pop” stars Elton John.

Having moved to London in 1968, Davey got his first album credit that year on the Noel Murphy LP, Another Round. Noel and Davey then formed the band Draught Porridge in 1969. In 1970 Davey played on the album Seasons by Magna Carta and in 1971 joined that group as second guitarist. Their next album, Songs From Wasties Orchard, was helmed by Elton’s producer, Gus Dudgeon.Gus asked Davey to contribute to Bernie Taupin’s solo album in 1971. Davey played guitar, sitar, banjo, mandolin and lute while Bernie read his poetry aloud.

Soon after, in August 1971, Gus called upon Davey once more, this time to play acoustic guitar and mandolin parts on four songs on Elton’s Madman Across The Water album, including the intricate harmonic part that anchors the title track. A week or so later, Elton invited Davey to join the band full-time, joining drummer Nigel Olsson and bassist Dee Murray both in the studio and on stage — and thus was born the group that solidified Elton’s sound.

Since then Davey has been an indispensable part of most of Elton’s albums.Through the decades, Johnstone has squeezed in an equally impressive, varied body of work as an in-demand session player. His roster includes Stevie Nicks, Bob Seger, Alice Cooper, Rod Stewart, Meat Loaf, the Pointer Sisters, Olivia Newton-John, Judy Collins, and many others. He has also done movie music for James Newton Howard and Hans Zimmer.

Johnstone lives in Los Angeles with his wife. He has seven children.

On 10 June 2009, Johnstone played a landmark 2,000th show as a member of the Elton John Band at the SECC Glasgow , he is currently serving as John's musical director, in addition to his guitar work. I looked through the credits for the Elton John film, Rocketman, due out this month and he doesn't seem to feature in it, you will however be able to see Scotsman Richard Madden as Eltons manager John Reid, a much better casting than Irishman Aidan Gillen, who played Reid in the Freddie Mercury bio, Bohemian Rhapsody

.Johnstone recently said "I’ve Had an Amazing, Unbelievable Career”: He released a new solo album – Deeper Than My Roots, only his third solo project, from what I can gather he put the album together during the hiatus most people had during the covid pandemic.

For the musicians out there he mainly uses a Les Paul Deluxe which he bought inn 1972. As you can imagine he has used a plethora of guitars including his trusty ’72 Les Paul Deluxe, a Gibson L-5, B.B. King Lucille, a ’69 Strat, and an Ernie Ball EVH. Acoustics included a Takamine, Gibson J-200, and a late-’60s Yamaha FG-140 he played on many of John’s ’70s classics.

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

BEYOND THE TIME BARRIER (1960) – Episode 171 – Decades Of Horror: The Classic Era

“Sterile?” Yes, sterile! And they weren’t talking about surgical instruments. Join this episode’s Grue-Crew – Chad Hunt, Daphne Monary-Ernsdorff, Doc Rotten, and Jeff Mohr – as they blast off to the distant future of… 2024? The movie is Beyond the Time Barrier (1960).

Decades of Horror: The Classic Era Episode 171 – Beyond the Time Barrier (1960)

Join the Crew on the Gruesome Magazine YouTube channel! Subscribe today! And click the alert to get notified of new content! https://youtube.com/gruesomemagazine

ANNOUNCEMENT Decades of Horror The Classic Era is partnering with THE CLASSIC SCI-FI MOVIE CHANNEL, THE CLASSIC HORROR MOVIE CHANNEL, and WICKED HORROR TV CHANNEL Which all now include video episodes of The Classic Era! Available on Roku, AppleTV, Amazon FireTV, AndroidTV, Online Website. Across All OTT platforms, as well as mobile, tablet, and desktop. https://classicscifichannel.com/; https://classichorrorchannel.com/; https://wickedhorrortv.com/

In 1960, a military test pilot is caught in a time warp that propels him to the year 2024 where he finds a plague has sterilized the world’s population.

Director: Edgar G. Ulmer

Writer: Arthur C. Pierce

Produced by: Robert Clarke (produced by); Robert L. Madden (executive producer); John Miller (executive producer)

Casting by: Baruch Lumet (uncredited), Sidney Lumet (uncredited)

Music by: Darrell Calker

Production Design by: Ernst Fegté

Makeup Department:

Corinne Daniel (hairdresser) (as Corrine Daniel)

Jack P. Pierce (makeup creator) (NOT the mutants!)

Special Effects by: Roger George

Costumer: Jack Masters

Selected Cast:

Robert Clarke as Maj. William Allison

Darlene Tompkins as Princess Trirene

Arianne Ulmer as Capt. Markova (as Arianne Arden)

Vladimir Sokoloff as The Supreme

Stephen Bekassy as Gen. Karl Kruse

John Van Dreelen as Dr. Bourman (as John van Dreelen)

Boyd ‘Red’ Morgan as Captain (as Red Morgan)

Ken Knox as Col. Marty Martin

Don Flournoy as Mutant

Tom Ravick as Mutant

Neil Fletcher as Air Force Chief

Jack Herman as Dr. Richman

James ‘Ike’ Altgens as Secretary Lloyd Patterson (as James Altgens)

William Shephard as Gen. York (as William Shapard)

John Loughney as Gen. Lamont

Russ Marker as Col. Curtis (as Russell Marker)

Arthur C. Pierce as Mutant Escaping from Jail (uncredited)

Malcolm Thompson as Guard (uncredited)

While testing the latest and greatest airship just above the atmosphere, Major William Allison (Robert Clarke) accidentally travels to the apocalyptic future of… 2024! Little did they know. Beyond the Time Barrier (1960) is a low-budget, sci-fi B-picture from director Edgar G. Ulmer (The Black Cat, 1934; Detour, 1945) and writer Arthur C. Pierce (The Cosmic Man, 1959; The Human Duplicators, 1965). To Chad’s dismay, the plot includes a lot of walking and talking across a set filled with inverted pyramids. Oh, and the mutants… sigh. Check out what the Grue Crew has to say about this B&W, time-travel trainwreck. Also, stick around for the usual batch of feedback from past episodes.

You might also want to check out these Decades of Horror: The Classic Era episodes:

THE HIDEOUS SUN DEMON (1958) – Episode 41: w/Robert Clarke as writer, director, producer, and star

THE BLACK CAT (1934) – Episode 67: directed by Edgar G. Ulmer, starring Bela Lugosi and Boris Karloff

At the time of this writing, Beyond the Time Barrier is available for streaming from the Classic Sci-Fi Movie Channel, Amazon Prime, and Tubi. The film is available on physical media as a Blu-ray from Kino Lorber in the Edgar G. Ulmer Sci-Fi Collection, a trio of films that also includes The Man from Planet X (1951) and The Amazing Transparent Man (1960).

Gruesome Magazine’s Decades of Horror: The Classic Era records a new episode every two weeks. Up next in their very flexible schedule, as chosen by guest host Michael Zatz, is The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1923), another silent scream starring Lon Chaney! Sanctuary! Sanctuary! Incidentally, this will be the Classic Era’s tenth discussion of a silent film.

Please let them know how they’re doing! They want to hear from you – the coolest, grooviest fans: leave them a message or leave a comment on the Gruesome Magazine YouTube channel, the site, or email the Decades of Horror: The Classic Era podcast hosts at [email protected]

To each of you from each of them, “Thank you so much for watching and listening!”

Check out this episode!

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

233 - The Best Exotic Marigold Hotel

From Shakespeare in Love director John Madden and with a bursting prestige-y ensemble, The Best Exotic Marigold Hotel is one we have been saving. Led by Dames Judi Dench and Maggie Smith, who both had other films in the race in this season, the film follows several seniors who seek fulfillment and romance in India, including Tom Wilkenson as a man seeking reconciliation with a former gay lover. With Dev Patel as a young hotelier, the film was a global box office success that showed up throughout the precursor season, but Oscar did not come calling.

This episode, we take a look at the 2012′s wide-spread acting races, with all previous winners in Supporting Actor and Jennifer Lawrence winning Best Actress. We also talk about Smith’s two Oscar wins, Dench’s near nomination this year for Skyfall, and the Ol Parker franchise ethos.

Topics also include our winner predictions for this year, “The Quartet,” and Dev Patel going from twink to hunk.

Links:

The 2011 Oscar nominations

Vulture Movies Fantasy League

Subscribe:

Spotify

Apple Podcasts

Google Play

Stitcher

youtube

youtube

#John Madden#Ol Parker#Judi Dench#Maggie Smith#Tom Wilkenson#Bill Nighy#Dev Patel#Penelope Wilton#Celia Imrie#Tina Desai#AARP Movies for Grownups#Golden Globes#Academy Awards#Oscars#movies

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nick Nolte in The Thin Red Line (Terrence Malick, 1998)

Cast: Adrien Brody, Jim Caviezel, Ben Chaplin, George Clooney, John Cusack, Woody Harrelson, Jared Leto, Nick Nolte, Sean Penn, John C. Reilly, John Travolta. Screenplay: Terrence Malick, based on a novel by James Jones. Cinematography: John Toll. Production design: Jack Fisk. Film editing: Leslie Jones, Saar Klein, Billy Weber. Music: Hanz Zimmer.

The Thin Red Line was much anticipated because it was Terrence Malick's return as a director after a 20-year absence, following the much-praised features Badlands (1973) and Days of Heaven (1978). But it had the misfortune to come out only a few months after Steven Spielberg's Saving Private Ryan, whose portrayal of the actuality of combat on D-Day and after was hailed as landmark filmmaking. There are those who think more highly of Malick's film: Spielberg's movie, they argue, is weakened by his desire to celebrate the courage of those who fought in World War II, resulting in the gratuitous frame-story about the aging Ryan's return to the cemetery in Normandy, as well as in some conventional war-movie plotting. Malick's movie is anything but conventional: the combat scenes are accompanied by a meditative, metaphysics-heavy commentary supposedly voiced by the combatants themselves. To my mind, this mixture of war-movie action and reflective voiceover doesn't work. For one thing, much of what's said in the commentary sounds like the kind of poetry I used to write in college. Malick certainly makes his point about the existential absurdity of war, but he makes it over and over and over, to the expense of developing human characters. Sean Penn's character seems to have been designed to be the movie's central consciousness, but much of that function in the story got lost in the editing: The original cut of the film was five hours long, so it had to be reduced to its current three-hour run time, along with much of the substance of Nick Nolte's blustering colonel, whose motivations are simply alluded to in the voiceover and some of his dialogue. The editing also eliminated the performances of such major film actors as Billy Bob Thornton, Martin Sheen, Viggo Mortensen, Gary Oldman, and Mickey Rourke, while for some reason retaining the rather pointless cameos by George Clooney and John Travolta. The movie was nominated for seven Oscars, including best picture, but received none. It may, however, have siphoned away some votes from Saving Private Ryan, allowing Shakespeare in Love (John Madden, 1989) to emerge as the surprise and still very controversial best picture winner.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Profiles

The Player Queen Why Judi Dench rules the stage and screen.

By John Lahr January 13, 2002

Photograph by Dudley Reed

In the opening sequence of “Iris,” an extraordinary film about the late novelist Iris Murdoch’s descent into the limbo of Alzheimer’s, Murdoch and her loyal man-child of a husband, the Oxford don John Bayley, are shown swimming like two plump sea lions through the murk of the Thames. They’re happy in their underwater playground, which distorts light and form and contains the sediment of ages. They float freely but are always in contact, dodging among the rocks and weeds in joyful, directionless exploration. Water was Iris Murdoch’s primal habitat; by no accident, it is also the favorite element of the woman who plays her here, Judi Dench. “There’s a wonderful abandonment you feel in water,” Dench says. “It’s very liberating. It’s like the unconscious. You’re just floating around there and trusting that you’re going to come up to the surface.”

This is not the only point of intersection between the two women: the adventure of the unknown, the salvation of the imagination, the promotion of happiness, and a lifelong inquiry into goodness are all themes in the elusive lives of both Murdoch and Dench. Sir Richard Eyre, the director and co-author of “Iris,” says that while writing the screenplay he tried to instill his sense of Dench into the character of Iris. “There was never a question of how do you bring Iris and Judi Dench together,” he says. “Essentially, the character is Judi Dench-stroke-Iris Murdoch.”

Dench, who has played both Queen Victoria and Queen Elizabeth I on film and was made a Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire in 1988, is beloved by the English public for her quintessential Britishness. “I think that in a lot of people’s eyes she is the equivalent of the Queen—she inspires such phenomenal affection,” says the director John Madden, who launched Dench’s late-blooming film career in 1997 with “Mrs. Brown.” (Significantly, last month the seventy-seven British families that lost relatives in the Twin Towers catastrophe chose Dench to read at the memorial service at Westminster Abbey.) But she and Murdoch share an Anglo-Irish heritage, and each, in her own way, is a paradoxical amalgam of propriety and wildness.

With a leafy home in Surrey, a silver Rover, a taste for simple if expensive clothes, a commitment to charities (she is a patron of a hundred and eighty-three of them), and her obbligato of drollery—what Billy Connolly, who starred opposite her in “Mrs. Brown,” calls “that light, posh, self-effacing humor”—Dench, who is sixty-seven, cuts a deceptively sedate, suburban figure. At work, however, she trolls her turbulent Celtic interior, a vast tragicomic landscape that ranges between despair and indomitability. “There’s a sort of crimson place deep within her—a fiery dark-red place that stokes all the things she does,” Connolly says. “You don’t get to see it. But you occasionally get glimpses of how tiresome she finds the doily-and-serviette crowd. You know, those English twittering fucking women—they think she’s one of them, and she isn’t.” This complexity is what Dench brings to her acting, which is nowhere more inspired than in her depiction of Murdoch. Her performance parses every nuance in the writer’s trajectory of decline—from embarrassment to bewilderment, from terror to loss, from nonentity to a final connection with an enduring life force, where, in the shuffle of dementia, Murdoch somehow finds a dance.

Dench is not much of a reader, but she has read most of Murdoch’s novels, and before filming she went so far as to sit outside Bayley’s house while he was away to absorb the shambolic atmosphere of the place. (She found his car in the driveway, unlocked and with a window open.) “I didn’t want to miss that snapshot in my mind,” she says. But her uncanny portrait emerged out of her own process, a combination of technical rigor and imaginative free fall, in which, according to Eyre, “she doesn’t put anything of herself between her and the character.” He explains, “I was really staggered at the way she transformed herself. Toward the end of the film, when Iris’s mind has gone, and you look at Judi’s face and see that implacability, the sense of peace and the absence in her eyes, that is alchemy. She didn’t go to old people’s homes. She didn’t sit and study. It’s intuitive. She’s quick. I mean, really quick.”

Except for time out to have a child and to nurse her husband of thirty years, the actor Michael Williams, who died last January of lung cancer, Dench has been performing almost constantly for four and a half decades. She appeared in the first season of the Royal Shakespeare Company, in 1961, and in the eighties was a founding member of Kenneth Branagh’s Renaissance Theatre Company, for which she has also directed plays. Under the auspices of the Old Vic, the R.S.C., and the Royal National Theatre, she has turned in some of the greatest classical performances in recent memory. Her Juliet in Franco Zeffirelli’s 1960 stage production of “Romeo and Juliet”; her Titania in “A Midsummer Night’s Dream,” directed by Sir Peter Hall in 1962; her Viola in “Twelfth Night” in 1969; her Lady Macbeth in Trevor Nunn’s magnificent 1976 production; her Cleopatra in Hall’s 1987 “Antony and Cleopatra”—all are exemplars of contemporary Shakespearean performance. Her work in the modern repertoire—as Anya in “The Cherry Orchard,” as Juno Boyle in “Juno and the Paycock,” as Lady Bracknell in “The Importance of Being Earnest,” and as Christine Foskett in Rodney Ackland’s rediscovered fifties classic “Absolute Hell”—has also had a huge impact on English theatregoers. And Dench has inspired allegiance as well through her television career, which includes thirty-four films and two popular long-running comedy series, “A Fine Romance” and “As Time Goes By.”

“See you on the ice, darling,” she has been known to call out from her dressing room to an actor headed toward the stage. For Dench, “the crack”—the Irish term for fun—is riding the exhilarating uncertainty of the moment. To that end, she is famous (some would say notorious) for not having read many of the parts she accepts. Instead, she has someone else paraphrase the script for her. (Williams usually had this duty before he died; now it has fallen to Dench’s agent, Tor Belfrage.) “Michael said, ‘Just read that one line,’ ” Dench recalls of “Pack of Lies,” Hugh Whitemore’s successful spy story, in which she and Williams starred. “It was just one line. I read it, and I knew then that it would be all right.”

“It often seems absurd to me that a woman as intelligent as Judi could roll up at the beginning of the rehearsal not having read the play,” says Branagh, who directed Dench in his films of “Hamlet” and “Henry V” and has, in turn, been directed by her onstage in “Much Ado About Nothing” and “Look Back in Anger.” Although this method allows Dench to arrive at rehearsals with, as Branagh puts it, “the right kind of blank page to start writing on,” from a professional point of view it is also sensationally reckless. “I don’t know what it is in me, this kind of perversity,” Dench told me when I visited her at home last July. “I don’t understand it myself. I think some people think it’s an affectation. It’s thrilling, though, isn’t it? You don’t know what’s coming.”

The habit of not reading scripts has, over the years, landed Dench in a few sticky theatrical situations, such as Peter Shaffer’s turgid “The Gift of the Gorgon,” in 1992. And at first she wasn’t keen to take on her current West End outing, in a revival of “The Royal Family,” the slim 1927 Edna Ferber and George S. Kaufman satire of the theatrical Barrymores, but her mind was made up for her when she received a call from the director, Peter Hall. “It’s entirely a roll of the dice, but it has to do with friends, with people I love and admire,” she explained several weeks before rehearsals of “The Royal Family” began. “So if Peter rings me up and says, ‘You ought to do this play,’ I say, ‘Sure.’ I swear before God I have not read the play.”

Dench’s risk-taking onstage is in inverse proportion to her vulnerability off it. “When I go into a rehearsal room, my coat and bag have to be nearest the door,” she said in a recent television interview. Performing, for Dench, is an antidote to chronic insecurity; it gives her, she says, what the Cockneys call “bottle”: “It’s courage. You know, like jumping into ice-cold water. If it’s to be done—do it. Go!” Recently when Trevor Nunn offered her a role at the National, she replied, “I want to come back to the National, but not in that part. Would you ask me to do something more frightening?”

Dench’s derring-do also seems necessary to keep her nearly perpetual routine of rehearsal and performance a fresh and vigorous challenge. “Her desire is to re-create each time, to reëxperience, and not simply reproduce,” Branagh says. To that end, she refuses analysis. Without preconceived notions, she tries to let the character play her. “She absolutely hates to rationalize,” Eyre says. “When you’re working with her, she’ll ask a question about a scene or a character, and when you go to talk about it, at some point she’ll say, ‘Yeah, O.K., I understand.’ She doesn’t want it spelled out. She has to find it herself.” A long time ago, when Eyre was doing a play with Dench at the National, where he was the artistic director for ten years, she left her script in the rehearsal room; the next day, Eyre handed it to her. “ ‘Oh, you look terribly shocked,’ ” he recalls her saying. “ ‘Is it because I didn’t take my script home with me?’ I said, ‘Well, I guess so.’ She talked to me about how she learned lines. The work that she does outside rehearsal is not sitting down with the script. She just sort of envisions the scene and colors it in her mind.” Dench’s method of bushwhacking through her unconscious to find the emotional core of a character is, she says, completely instinctive: “The subconscious is what works on the part. It’s like coming back to a crossword at the end of the day and filling in seventeen answers straight off.”

In one scene of “Iris,” the senile Murdoch goes walkabout in the rain on a motorway and slips and falls down an embankment into the underbrush. This is the first and only scene in the film in which Dench’s Murdoch, whose eyes are always turned inward, really sees and acknowledges Bayley. “I said to Judi, ‘You have to find a way of doing it that reconciles a sort of rationality with the fact that her brain is more or less gone,’ ” Eyre says. “That’s all she wanted to know.” When the distressed Bayley (played by Jim Broadbent) finally finds her, Dench is covered with mud and laughing to herself. Out of her solitude, her eyes come to rest on Broadbent’s face. “I love you,” she says, and with a startling glimmer of clarity Dench manages to invoke the blessing and heartbreak of a lifetime of connection.

Dench describes herself as “an enormous console with hundreds of buttons, each of which I must press at exactly the right time.” She adds, “If you’re lucky enough to be asked to play many different parts, you have to have reserves of all sorts of emotions. When I was rehearsing a part I’d never, ever, ever discuss it with Michael, because I had that pressure-cooker syndrome. If I once open that little key—pffft!—the stuff goes.”

In nature, as in art, the secret of conservation is not to disturb the wild things. Dench’s brooding talent has its correlative in her five-acre Surrey domain, Wasp Green, and in the low-slung, wood-beamed 1680 yeoman’s house where she lives with her twenty-nine-year-old daughter, the actress Finty Williams, her four-year-old grandson, Sammy, nine cats, and several ducks. The front of the house is bright, tidy, and picturesque in a Country Life sort of way; the back acres, however, have been left alone, with only a small path cut through a thicket of brambles, nettles, and wild orchids. “You have to see the back garden to understand Judi,” Franco Zeffirelli says. “She puts up a façade sometimes, but for herself she reserves a private garden. You discover there treasures that you don’t see at the front of the house.”

On the day I visited her there last summer, Dench, in Wellington boots, stepped lively on the overgrown path. “I’ve got to cut these back,” she said, swiping at the nettles. She pointed out new plantings: a black poplar to commemorate a row that had blown down the previous year; “Sammy’s oak,” a tree planted in honor of her grandson’s birth; and the place she’d chosen for “Mikey’s oak,” a sapling that was originally an opening-night present from Williams to the director Anthony Page, whose production of “The Forest” was Williams’s last acting job. “What’s important to me is continuance—a line stretching on,” Dench said. “I hate things that start and finish abruptly.”

If the wild back garden is a kind of memory theatre for Dench, the theatre itself puts her in touch with her family, which she calls “a unit of tremendous encouragement.” “All the qualities that Judi has as a person, and, indeed, as an actress, come from the very close family background,” Williams said on a 1995 “South Bank” TV biography of his wife. Dench’s love of work, painting, swimming, jokes, and especially acting are passions she absorbed from her father, Dr. Reginald Dench, a physician who served as the official doctor for the Theatre Royal in York before he died, in 1964. “I remember going visiting with him,” Dench says. “When we turned into a road, children would run and hold on to the car. That’s the kind of doctor he was. He was a wonderful raconteur. He had the most incredible sense of humor—just spectacular.” When Dench was about fifteen, on holiday in Spain, she admired a pair of expensive blue-and-white striped shoes. “Well, I think you could probably have those shoes,” she recalls her father saying. “Let’s go to lunch. We’ll discuss it.” At lunch, Dench—a fish lover—scanned the buffet of prawns and lobsters. “Daddy looked at me and said, ‘Would you like that?’ ‘Yes, please.’ So I had four big prawns and enjoyed every minute of it. Daddy said, ‘You’ve just eaten your shoes.’ ”

The Dench children—Judi, Jeffrey, who is now an actor, and Peter, who became a doctor—grew up in York, in a sprawling Victorian house, where Judi, the youngest, had the attic room and was allowed to draw on the walls. “She got her own way,” Jeffrey says. “Judi was Daddy’s Beautiful Lady.” According to her daughter, Finty, the only discrepancy between the public Dench and the private one is her temper. Her volatility is an inheritance from her flamboyant, sharp-tongued mother, Olave, who once threw a vacuum cleaner down the stairs at a representative who had called to inquire about it. “You didn’t cross her, or pow!—not hitting, but a tongue-lashing, and you stayed lashed,” Jeffrey says. Dench’s contradictory nature—with its combination of mighty spirit and “nonconfidence,” as she calls it—appears to have been forged as she tried to negotiate her mother’s combustible personality. “She loved admonishing Judi,” Trevor Nunn says of Olave. “I mean the kind of admonishment that comes from absolute worship. The privilege of being able to be the one who could put her in her place. ‘Judi, you mustn’t say that!’ ‘Judi, you’re such an embarrassment!’ ” Dench says, “She was outrageous.” In the late seventies, by which time she was having trouble with her sight, Olave had lunch with Nunn and Dench at a sophisticated, self-congratulatory Italian restaurant called the Lugger. “Olave ordered tomato soup, which came in a huge bowl,” Nunn recalls. “A waiter arrived with a little sachet of cream, with which he spelled out the name of the restaurant on the soup and then left. ‘Judi,’ Olave said, ‘a man has just come and written “bugger” in me soup!’ ”

Dench’s parents took a keen interest in amateur dramatics and, when Dench became an actress, their support verged on the overprotective. They saw their daughter in “Romeo and Juliet” more than seventy times; once, Reginald got so involved in the play that when Judi, as Juliet, said, “Where is my father and my mother, nurse?” he was heard to say, “Here we are, darling. In Row H.”

Whereas most stars seek a public to provide the attention they failed to get in childhood, Dench’s commitment to the theatrical community is, she admits, an attempt to reproduce the endorsement and excitement of her first audience—her family. She claims not to be “good at my own company.” Rather, to understand her own identity she needs to be in the attentive gaze of others—as the psychologist D. W. Winnicott puts it, “When I look I am seen, so I exist.” Dench is clear on this point. “I need somebody to reflect me back, or to give me their reflection,” she says. Ned Sherrin, who directed Dench and Williams in “Mr. and Mrs. Nobody” in 1986, says he was so aware of Dench’s need “to create a family with each show” that he added a couple of walk-ons to what was otherwise a two-person play.

Dench, who keeps a collection of Teddy bears and hearts and a doll’s house at Wasp Green, somehow contrives, as Branagh says, “to feel and be in the moment, as a child.” In the collegial atmosphere of a theatre company, she is an adored and prankish catalyst, inevitably, as her brother Jeffrey points out, “at the center.” “Eight going on sixty-seven” is how Geoffrey Palmer, her co-star in the nineties TV series “As Time Goes By,” characterizes the innocence and spontaneity she brings to the daily routine of self-reinvention. Her process—her abdication of responsibility to intuition, her need to be told the story—is not so much about being lost as it is about being held. She casts the director as her father and exhibits an almost filial devotion. “When we did ‘A Midsummer Night’s Dream,’ she did this extraordinary Titania,” Hall says. “I said to her, ‘One day, you’ll play Cleopatra. I want you to make me a promise that when you do it you’ll do it with me.’ We shook hands on it.” Hall goes on, “Twenty years later, she rang me up and said, ‘I’ve just been asked to play Cleopatra by the R.S.C. I said I was promised to you. Now, do you want to do it?’ ”

From her first sighting onstage—as a seventeen-year-old Ariel in a production of “The Tempest,” at the Mount School, in York, where she boarded from 1947 to 1953—Dench was transparently a natural. But neither Dench, who then aspired to be a set designer, nor her teachers took her ability very seriously. The novelist A. S. Byatt, a schoolmate, recalls, “I used to talk to Katharine MacDonald, the English mistress who taught her. ‘You know, Judi will probably be content,’ as she put it, ‘to dabble her pretty feet in amateur dramatics.’ ”

Dench enrolled at London’s Central School of Speech and Drama simply because her brother Jeffrey, who went there, had told her appealing stories about the place. Vanessa Redgrave, who was in Dench’s class, and who was then self-conscious and gawky, remembers being both “admiring and jealous” of Dench’s naturalness. “She skipped and hopped with pleasure and excitement up the stairs, down the corridors, and onto the stage,” Redgrave wrote in her autobiography. “She wore jeans, the only girl who had them, a polo-neck sweater, and ballet slippers that flopped and flapped as she bounded around.” The turning point in Dench’s ambition came during a mime class in her second term, when she was required to perform an assignment—called “Recollection”—that she’d completely forgotten to prepare. “I don’t remember thinking anything out,” she says. “I walked into a garden. I bent down to smell something like rosemary or thyme. I walked and just looked at certain things. I picked up a pebble, and threw it into what I imagined was a pond and watched the ripples going out from it. I looked over and sat on a swing. And I swung, you know, like you do on a swing that isn’t there. Then I walked out of the garden. That was my mime.” Her teacher, Walter Hudd, gave her, she says, “the most glowing notice I think I’ve ever had. What is more, he said, ‘You looked like a little Renoir doing it.’ I thought, Well, I think that I will enjoy what I’m going to do, hopefully get work, go for it.”

Dench graduated with a first-class degree and four acting prizes. According to her biography, the unfortunately titled “Judi Dench: With a Crack in Her Voice,” by John Miller, a notice was posted on the school’s bulletin board naming her the student most likely to become a star; and when the Old Vic offered her the role of Ophelia opposite John Neville’s Hamlet it seemed a self-fulfilling prophecy. “enter judi—london’s new ophelia—old vic make her a first-role star,” the Evening News announced. When Neville heard about his tyro Ophelia, “I blew my top,” he says. He begged the theatre’s publicity department not to hype her before the opening. “I thought, and still think, that it would have been best just to let the media discover her for themselves,” he says. Dench was more or less annihilated by the press. “Hamlet’s sweetheart is required to be something more than a piece of Danish patisserie,” Richard Findlater wrote in the Sunday Dispatch; in the Observer, Kenneth Tynan swatted her away as “a pleasing but terribly sane little thing.” At the end of the season, when the production toured America, the role was taken away from Dench. “That was a kind of dagger to the heart,” she says. “I remember John Neville saying to me, ‘You must decide what you’re doing this for.’ And I made my mind up, and I think that’s what keeps me going.” The answer remains Dench’s secret. “The only part of her that is totally unreachable for me is that she’s never told me why she’s an actress,” Finty says. “I would love to know what motivates her.”

Dench came of age just as the definitions of femininity were being rewritten, and she was an incarnation of the freewheeling, bumptious independence of the eternally young New Woman. With a cap of close-cropped hair, a strong chin, high cheekbones, big alert eyes, and a wide smile, the five-foot-two Dench cut a gamine figure onstage. Zeffirelli still thinks of her as “a kind of irresistible bombshell.” He says, “She was funny and witty and biting. You had to be very careful what you said because she would answer back promptly. She was a dynamo, this girl. She just was an extraordinary surprise, because I was accustomed to Peggy Ashcroft and Dorothy Tutin, that style of acting.”

David Jones, who directed one of the high-water marks of Dench’s TV career, “Langrishe, Go Down” (1978), remembers her quicksilver quality in Zeffirelli’s “Romeo and Juliet.” He describes her “darting—like a bird coming onto the stage and going off again. You weren’t quite aware of the feet touching the ground, this extraordinary agility of body and of mind.” Dench’s kinetic quality onstage finds different but no less startling expression in film. “She has a kind of sprung dynamic with her eyes,” John Madden says. “They don’t move gradually and settle or shift. They dart, then dart back, then settle again on the place that they just avoided looking at. It’s almost like a double take, which suggests a kind of current flowing in an opposite direction from what she is saying.”

When you meet Dench, it’s hard not to feel the engine running inside her. She’s nervy. Her fingers play across her lips; her feet tap under the table. Her lightness and quickness are very much a part of her metabolism as an actress and lend credibility to her performances. “She is the perfect Shakespearean, because the great characters in Shakespeare have fantastic speed of thought,” Nunn says. “They have speed of wit, speed of response, speed of invention of the image. That only works if the actor convinces the audience that that language is being coined by that brain in that situation.” He adds, “You live in the moment with her. There’s never a sense that she’s doing a recitation.”

Dench’s combination of insight and inspiration, charisma and cunning has made her one of Britain’s two marquee players whose names guarantee West End commercial success. (Her friend Dame Maggie Smith is the other.) Even with the drastic fall-off of tourism after September 11th, “The Royal Family” had half a million pounds in advance bookings, and, despite a tepid press, is still doing brisk business. Dench’s drawing power, for which she is paid a five-figure salary every week, plus up to ten per cent of the gross, has been greatly enhanced since the mid-nineties by her emergence as an international film star. Before being touched by what she calls “the luck of John Madden,” who directed her in both “Shakespeare in Love” and “Mrs. Brown,” Dench had not shown much interest in films, though she’d appeared in twelve. When she was starting out, she was told by an industry swami that she didn’t have “a movie face.” “It put me completely off,” says Dench, who nonetheless nearly got the starring role in Tony Richardson’s 1961 film “A Taste of Honey.” “But then I only ever really loved the stage. It’s only recently that I’ve got to like film so much.” For the last three James Bond films, Dench’s severe side has been siphoned off into M, Bond’s no-nonsense boss; and among the fifty-five awards she lists in her bio are three Oscar nominations in the past four years—for “Mrs. Brown,” “Shakespeare in Love,” and “Chocolat.” (The command and wit of her seven-minute cameo as Elizabeth I in “Shakespeare in Love” earned her the 1999 Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress.)

Among theatre people, Dench’s popularity is a source of some curmudgeonly grousing—“If she farted, they’d give her an award,” one playwright said—and some good jokes. Eyre recounted a conversation he once had with the playwright Alan Bennett, who had seen a man wearing a heavy-metal-style T-shirt that read “Hitler: The European Tour.” They tried to imagine a T-shirt in worse taste. Recalling the thirty-nine Turin soccer fans who had been killed at a match against Liverpool in 1995, Eyre suggested “Liverpool 39-Turin 0.” “Yes, that’s ghastly,” Eyre recalls Bennett saying. “But the worst-taste T-shirt, the very, very worst, would be ‘I Hate Judi Dench.’ ”

One clue to Dench’s appeal is her husky voice, which has a natural catch in it; certain notes fail to operate. When Dench was at the Nottingham Playhouse in the mid-sixties, she had the box office display a notice that said, “Judi Dench is not ill, she just talks like this.” Dench’s sound is idiosyncratic but not mannered; it is full of intimations that, as Alan Bennett says, “open you up to whatever she’s doing” and allow various interpretations. Sir Ian McKellen, who has performed with Dench in four plays, most memorably as Macbeth to her Lady Macbeth, calls it “a little girl’s voice—the crack suggests she’s not in control.”

Another reason for Dench’s popularity is her warmth. She communicates a palpable, deep-seated generosity. “You feel somehow, even as a member of the audience, that if you were in trouble she would help you and laugh you out of it,” Hall says. Dench pays close attention to her audience. During the half hour before a show, she keeps the loudspeakers in her dressing room turned up, both to take the measure of the house and to pump up her adrenaline. “I have to hear the audience coming in,” she says. “I need to be generated by it—for the jump-off. It’s like a quickie ignition.” Once, an American student asked Dench if the audience made a difference to her; Dench replied, “If it didn’t make a difference, I’d be at home with me feet up the chimney. That’s who I’m doing it for.” “It’s a little unnerving when you’re working with her,” McKellen says. “What’s happening is that she’s making love to the audience—not making love but providing the focus of attention to an audience that wants to love. You could be wrapped in Judi’s arms onstage and acting as closely with her as possible, and she’s capable of betraying you, because her main reason for being in your arms is for the audience’s delectation. It isn’t upstaging. That isn’t taking away the focus. Her spirit is flowing, and it’s a decision she’s made that it will flow. And when I’m in the audience I want her to do that.”

In performance, Dench is a minimalist: no gesture or movement is wasted. Richard Eyre refers to what he calls her “third eye”: “It’s the ability to walk on fire and yet be completely unburnt, to be red-hot with passion and at the same time there’s this third eye that is looking down thinking, Am I doing this right?” Billy Connolly told me about filming one scene in “Mrs. Brown”: In the first meeting between the widowed Queen Victoria and her Scottish manservant, John Brown, Brown’s forthrightness catches the Queen off guard. “Honest to God, I never thought to see you in such a state,” Brown says. “You must miss him dreadfully.” In an astonishing closeup, the austere formality of Dench’s visage suddenly transforms—a cloud of grief sweeps over her and she breaks up. “Judi did that twelve times,” Connolly says. “Every time, I thought I’d really wounded her. You see me looking all bewildered. Well, I actually was.”

“Dench has a kind of glamour when she performs,” says Hal Prince, who directed her as Sally Bowles in “Cabaret” in 1968 and considers her “the most effective of all the people who played the part.” Glamour—the word has its root in the Scottish word for “grammar”—is an artifice of elegant coherence; it requires distance. Dench, who is no Garbo or Dietrich, manufactures this not through stage-managed aloofness but through a natural sense of containment. David Jones says, “Her gift is to step down the throttle, so you don’t get the full impact of her passion; you just know there’s an enormous amount in reserve. It’s like a wave suspended.” McKellen observes, “She goes out, but she doesn’t always invite you in.”

On a bright July morning, Dench picked me up outside Gatwick Airport to ferry me back to Wasp Green. She arrived with a story—one that she retold three times during the day. She hadn’t known what I looked like, she said—though I later noticed on her desk a book I’d sent her with my jacket photo prominently displayed—and she’d stopped two men before I loomed up in her windshield. “I slowed down and this man says, ‘I know you. Are you with American Airlines?’ ” she said. At a stroke, she had levelled the playing field, by making herself appear just an ordinary, unrecognized citizen. The story got us talking and laughing. Disarming others is one of Dench’s great social gifts, and one of her most skillful defenses. “She was successful very young,” Eyre says. “She developed some sort of tactic that stopped people from disliking her.”

As a diva Dench is something of a disappointment. Her dislike of public display—what Branagh calls her “puritanical scrutiny of anything showy”—can be attributed at least in part to the tenets of her faith. She was introduced to Quaker practice as a teen-ager at the Mount School, and she still goes to Quaker meetings. “I have to have quietness inside me somewhere, otherwise I’d burn myself up,” she said in a recent television interview. Quakerism requires its followers to look for the light in others, as well as in themselves, and this, in a way, explains Dench’s view of acting as a service industry. “It’s a very unselfish job,” she says. “It’s about being true to an author, a director, a group of people, and stimulating a different audience every night. If you’re out for self-glorification, then you’re in the wrong profession.”

“There are a lot of people who are very willing to put my mother on a pedestal, which is a lonely existence,” Finty says. “She wants to dispute that so much that she will literally do anything for anybody.” For twelve years, Dench and Williams lived with all of their in-laws in one house, and Dench is a legendary sender of postcards and birthday cards; by Finty’s reckoning, she gives about four hundred and fifty Christmas presents a year. She once gave Eyre a wooden heart carved from a tree trunk; and, for as long as Hall can remember, on his birthday Dench has managed to have delivered—as far afield as Australia—his favorite meal: oysters, French fries, and a bottle of Sancerre. “Comes my seventieth birthday, and there’s no oysters, no Sancerre,” Hall says. “I said to my wife, ‘Well, I must be off the list.’ We had my dinner”—a party for fifty, with Dench at his side—”and there’s a Doulton china plate from Judi, specially made, with six oysters and chips painted on it.”

This hubbub of good will and connection, however, skirts the issue of intimacy. “Judi has always found safety in numbers,” says David Jones, who was involved with her briefly in his twenties. “When we were dating, I would arrange what I thought was a one-on-one meeting to go to a museum or the theatre. Quite often, I would turn up and find two other people invited. And Judi would say, ‘Isn’t it fun? They’re free! They can come with us.’ ” Some of Dench’s schoolmates, like the writer Margaret Drabble, found her buoyancy “a little Panglossian.” Even Dench’s husband, a man prone to the kind of melancholy that he called “black-dog days,” and which could stretch into months, sent up her effervescence. “With Judi, it’s bloody Christmas morning every day,” he told Branagh.

“I’m a person who off-loads an enormous amount onto people,” Dench told me. “Inside, there’s a core that I won’t off-load.” According to Finty, Dench “doesn’t like to talk about very emotional things,” but throughout our day together at Wasp Green her gallant cheer was tested by small unsettling moments. Although her charm never faltered, I was left with mixed messages, as if I had wandered into some Chekhovian scenario full of distressing secrets. Our extended conversation at a garden table on the lawn was interrupted first by a series of visitors (the mailman, a next-door neighbor, and two secretaries, each of whom got Dench’s full attention), then by phone calls from Anthony Page and Peter Hall, then by someone delivering a single pink rose (I learned later that it was from Finty—carrying on Williams’s tradition of having a single red rose sent to Dench every Friday of their marriage), then by Dench’s need to feed the herd of cats, and then by a panic over a credit card that might or might not have been stolen.

Finally, and most perplexingly, Finty, who moved back into her parents’ house when Michael fell ill, walked over unbidden with a provocative and bewildering announcement. “Your granddaughter is being played by an eighteen-year-old,” she said. Dench’s bright face collapsed. “Oh, Finty, I’m so sorry.” “It’s all right,” Finty said, with a wave of her hand. “I’m all right.” She turned back to the house, leaving her mother to struggle with her obvious disappointment. After a while, Dench said, “It’ll be for a very good reason.” Then, finally, she explained: “ ‘The Royal Family.’ She saw Peter.” Finty, who had recently finished filming in Robert Altman’s “Gosford Park,” had hoped for a part in the play.

A few minutes later, Finty came out again to say goodbye. “It doesn’t matter about that, you know,” Dench said. “It doesn’t matter.” Finty agreed. “She’s only a little eighteen-year-old, and maybe it’s her first job. Maybe she’ll be celebrating with someone and getting very excited,” she said. “Maybe you will have something else to do, you never know,” Dench said. “Never know,” Finty said, nodding. “My audition’s been cancelled on Tuesday.” There was a long, fierce silence as she exited for the second time. “It’s impossible being the child of an actor,” Dench said. A certain gravity fell across her face as she seemed to push down feelings of remorse and guilt and got on with the professional task at hand.

Onstage, Dench has found her bliss; offstage, that bliss has cast a shadow on others—on her brother Jeffrey (“There is jealousy,” he admits. “She’s had the breaks. I’m a jobbing actor. You know that niggles”), on Michael (“In some way, his heart was broken by Judi’s success,” Eyre says), and now on Finty, who seemed, in a way that neither of them quite acknowledged or understood, both to adore her mother and to wish to subvert her. A few months later, Finty told me a story that reminded me of this. While she and Dench were watching television together one night, Finty said, “Oh, I think Kylie Minogue”—the Australian pop singer and former soap-opera star—”is so talented.” According to Finty, Dench got “massively uptight. ‘Define “so talented,” ‘ she said. ‘She’s a singer, isn’t she? She looks good.’ She got really cross with me. She was, like, ‘If you think that’s talented, what are you aspiring to?’ ”

In her time, Dench has been serenaded by Gerry Mulligan from beneath her New York hotel window. She has watched, in West Africa, as, at the finale of “Twelfth Night,” people in the audience threw their programs into the air, then jumped to their feet to sing and dance for several minutes. She has clowned with the comedians Eric Morecambe and Ernie Wise. She has locked herself in a bathroom with Maggie Smith to escape the advances of the English comic character actor Miles Malleson. She has refused Billy Connolly’s offer to show her his pierced nipples. As for her own nipples, she has stood in front of the camera, naked to the waist and unabashed, dabbing meringue on them. She has cooled herself on a summer day by jumping fully clothed into a swimming pool. At Buckingham Palace, she has scuttled away from the ballroom with Ian McKellen to sit on the royal thrones. In a Dublin restaurant, when Harold Pinter, a theatrical royal, barked about the tardiness of their dinner, Dench, according to David Jones, actually barked back, “Mr. Pinter, you are not in London. Would you please adjust.” She has made David Hare a needlepoint pillow as a Mother’s Day present, with the words “Fuck Off” intricately stitched into the tapestry. On the day she became Dame Judi, Dench pinned her D.B.E. insignia on the jacket of the actor playing Don Pedro in a production of “Much Ado About Nothing” that she was directing. It is a barometer of her louche and lively life that, not long after that, the first ten rows of the National’s Lyttelton Theatre heard Michael Bryant, who was playing Enobarbus to her Cleopatra, say to Dench under his breath, “I suppose a fuck is well out of the question now?”

Still, as Zeffirelli says, “She has known suffering.” At the corner of her Surrey property is a rowan tree, planted on an exact axis with the back door of the house, which, according to folklore, is supposed to protect the house from witches; it has not been able to protect Dench from the caprices of life. Soon after Michael died, in January, an electrical fault in the garage—an old barn—started a fire that gutted it to the frame. That charred skeleton is the first thing that rolls into view as you enter the property, and it stands in eerie contrast to the tranquillity behind it—wisteria by the front door, a sundial, a swimming pool, a flotilla of plastic slides and Winnie-the-Pooh toys tucked underneath the warped cantilevered timbers of the porch. Seven years earlier, Dench’s house in Hampstead had burned down and a lifetime’s memorabilia went up in flames. And in 1997, in a weird instance of life imitating art, Dench, like her character Esme in “Amy’s View,” which she was rehearsing at the time, learned that Finty, then twenty-five, was eight months pregnant and hadn’t told her. She went immediately to Eyre’s office at the National. “She stood in the doorway and just collapsed,” he recalls. “She exploded. I’d never seen that. Unbelievably painful. She was massively wounded that the person she had thought of as her best friend in the world had not confided in her the not insignificant fact of her pregnancy.” (Finty hadn’t wanted Michael, a conservative Catholic, to know that she was having an illegitimate child.) Nevertheless, rehearsals of “Amy’s View” went on. Eyre says of Dench, “Deep within her is the ethos that you don’t let people down. If you’re an actor, you go on. As Tennessee Williams says, you endure by enduring.”

On July 9th of last year, a muggy Monday, at St. Paul’s Church in Covent Garden, a standing-room-only crowd heard Trevor Nunn eulogize Michael Williams as a fine actor and partner. “I remember them courting,” he said, standing opposite an enlarged photo of Williams, who was five feet four and puckishly handsome. “When they got married, Mike said to me, he was in the grip of feelings ‘beyond any happiness he had ever dreamed of.’ He told me more than once that his favorite line in Shakespeare was ‘You have bereft me of all words, lady.’ Because when he was with Jude, he knew the full extent of what Shakespeare was saying.”

By the time Dench and Williams were married, in 1971, when she was thirty-six, Dench had done a lot of living. “When she likes something, she wants it like a wild animal,” Zeffirelli says. Eyre adds, “She was prodigiously falling in love with the wrong man.” One such man was the late comic actor Leonard Rossiter, who was in another relationship when they had an affair. “Some days, she’d come in and she’d had a wonderful day with him,” recalls McKellen, who was then co-starring with her in “The Promise.” “Other times, he’d have to leave early or hadn’t turned up, and she was desperate. Tears, tears, tears. She was helpless and hopeless. What I was seeing was utterly vulnerable.”

In 1969, on an R.S.C. tour of Australia, Charlie Thomas, a talented young actor with a drinking problem, who was playing the lovelorn Orsino to Dench’s Viola, died under mysterious circumstances. Thomas had been very dependent on Dench, Nunn told me. “It was a shattering situation,” he said. Williams, who was also a member of the R.S.C. and had become, in Nunn’s words, “probably more than a friend,” flew out to comfort her. “What was between them deepened enormously during that time,” Nunn says. “Mike arriving made a fantastic difference.” On that trip, Williams proposed, but Dench demurred. “No, it’s too romantic here, with the sun and the sea and the sand,” Williams remembered her saying. “Ask me on a rainy night in Battersea and I’ll think about it.” One rainy night in Battersea, in 1970, she said yes.

Williams, who came from Liverpool, had a more working-class pedigree than Dench, and he had the right combination of sturdiness and faith to both tether Dench and contain what her agent calls the “Dizzy Dora” side of her personality. “Michael was all-calming,” Dench says. By every account, they were good companions. Dench recalls, “He used to say of himself, because he was Cancerian—the crab—and I’m a Sagittarian, ‘I’m scuttling away toward the dark, and you’re scuttling toward the light. What we do is we hold hands and keep ourselves in the middle.’ ”

But, as the decades wore on, and despite “A Fine Romance,” the sitcom they starred in together in the early eighties, Williams was increasingly in Dench’s shadow. “In a sense, every one of her successes was a diminution of him,” Eyre says. Dench was acutely aware of the problem. “Judi was protective of Michael like a lioness,” Geoffrey Palmer says. “I don’t think Michael was an easy man. But the fact that all his married life he was Mr. Judi Dench—that’s difficult for any man. He used to get very low. He sat at home feeding the bloody swans while she was doing three jobs a day.” According to Dench, during these depressions Williams would become remote and “very, very silent.” She says, “I had to give an incredible amount of confidence to Michael, who was very unconfident indeed.”

On the inside of Dench’s wedding ring is inscribed a modified line from “Troilus and Cressida,” which Williams included in the first note he wrote to her: “I will weep you, as ‘twere a man born in April.” It proved to be somewhat prescient. On their twenty-fifth anniversary, Dench spoke of “just missing the rocks.” The marriage, she says, was volatile. “I throw things,” she adds. “I threw a hot cup of tea at him and his mother. And the saucer. I didn’t hit either of them, unfortunately.” Williams enjoyed spending time at the local pub. On several Sundays, when they had guests for lunch, Williams and the male guests rolled back from the pub late for the meal. “Mum’s like ‘Fine. Lock all the doors,’ ” Finty recalls. “ ‘No, he’s not coming in unless he can get through the top window.’ ” Williams and his crew climbed to their lunch on a thirty-foot ladder. And once, just before Christmas in 1983, an argument about the boiler sent Dench and Williams into such a blind fury that they refused to talk or look at each other on the long ride into London, where they were performing in “Pack of Lies.” “The air was black, and we’re bowling down Shaftesbury Avenue and not speaking and this person knocks on the window and begins to sing ‘A Fine Romance,’ ” Dench says. “We howled with laughter. Howled. I realized it very much in the last year—he was a tremendous anchor to me. A real, proper anchor.”

Just months before Williams died, the family took a trip to Aberdeenshire, where Billy Connolly had gathered some friends at his castle. The week before, Williams had asked Dench whether he was going to die, and she’d told him he was. “When Judi told me about it, she started by looking me in the eye and ended up fiddling with the cutlery, then just went very quiet,” Connolly recalls. “She went to a place in her head where she obviously feels much more comfortable and didn’t say a thing.” Connolly is a banjo player, and when Dench and Williams were in residence he and his other guests—Steve Martin (banjo), Eric Idle (guitar), the Incredible String Band’s Robin Williamson (mandolin), and a local fisherman who played the fiddle— would go to a clearing in a nearby wood, build a fire, and sit on tree stumps to play, sing, and sometimes dance into the night. Connolly has a picture of the revels, with two green wicker chairs brought into the circle for Williams and Dench. Williams is laughing and holding a large glass of whiskey. He’s looking beyond the fire at the fiddler; Dench is looking at him. “They were like young lovers,” Connolly says. “They touched all the time. The wicker chairs are still there. We can’t move them. Nobody wants to. ‘Cause it’s Judi and Michael.”

“I have a huge amount of energy,” Dench told me when we met at the Union Club in Soho for lunch in November. “Grief produces more energy, and all that needs burning up.” In the ten months since Williams’s death, Dench’s herculean workload—”The Royal Family” and three films, “The Importance of Being Earnest,” “The Shipping News,” and “Iris”—had brought some of the shine back to her pale-blue, almond-shaped eyes. Her face was both animated and calm. “When my father died, it was almost like she was curiously liberated,” Finty says. And although Dench still feels “lopsided,” she said, “I just want to learn new things all the time,” and was full of news of her accomplishments in gardening, archery, and pool.

She had also learned to ride a Zappy scooter—a sort of skateboard with handlebars. Kevin Spacey, who before making “The Shipping News” told the director, Lasse Hallström, that he had two goals—“to give a good performance and to make Dench laugh”—had taught her in Central Park on his scooter, which has a turbo engine that goes up to about twenty miles per hour. “I was running along with her as she did it,” Spacey says. “People were kind of recognizing us, particularly her. Someone said, ‘Didn’t you have something to do with James Bond?’ And she said, ‘Yes, I’m his boss,’ and kept moving.” From her gold-leafed diary, Dench produced a photo of Spacey on location; he was wearing a black baseball cap with “Actor” embroidered above the visor and a sweatshirt she’d had made for him with the legend “The Caramel Macchiato of Show Business,” in honor of the coffee he’d brought her each day on the shoot. That evening, she told me, Spacey was coming to “The Royal Family.”

On performing nights, Dench leaves Wasp Green by car at quarter to five and arrives at the Theatre Royal Haymarket in London at six-fifteen. Her dressing room—No. 10, on the third floor, John Gielgud’s favorite—has a blue carpet, high ceilings, an antechamber, and a gold plaque on the front door with her name on it. First, Dench reads and responds to her letters. Her next order of business is to talk with the company. “We always will check up with each other,” she says. “Essential. It makes you laugh if you see them for the first time onstage. I don’t know why. I’m on a knife edge in this play.” Her ritual for getting dressed never varies. She puts on a body stocking, then black tights and a dressing gown. She bandages up her hair and does her face and, finally, her nails. Above her is an oval mirror festooned with greeting cards; to her right, a photo of Williams; and to her left a photo of her grandson, Sammy. Beside her on the dressing table are two lucky pigs, two trolls, and a snail (a memento of her very first role, at the age of four).

After our lunch, on the way out, I mentioned to Dench that I hadn’t yet seen “The Royal Family.” She paused at the front door of the club. “Will you tell me when you’re coming in?” she said, holding out her cheek to be kissed. “And I’ll overact for you.” It was an exquisite exit. The line came so fast and was played so deftly and spoken with such warmth that, for a moment, I believed she’d never said it before. ♦

Published in the print edition of the January 21, 2002, issue, with the headline “The Player Queen.”

#The New Yorker#Judi Dench#Profiles#John Lahr#DJD#Dame Judi Dench#Royal Shakespeare Company#Renaissance Theatre Company#Royal National Theatre Franco Zeffirelli#Romeo and Juliet#A Midsummer Night’s Dream#Twelfth Night#Lady Macbeth#Judith Olivia Dench

1 note

·

View note

Text