#john hersey

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Campbell Woods | John Hersey | The Guardian

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

10:52 AM: The President goes into the Cabinet Room to receive a delegation of Soviet officials, led by (it should not be incredible that stereotypes sometimes actually do show up) a simulacrum of a bear, a great hugger of a Russian man, State Minister of the Food Industry Voldemar Lein. With him are the ministers of food production, all looking well fed, for the Ukraine, Belorussia, Estonia, Armenia, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan and the Russian Republic. These men have just completed a delicious tour. They have been invited by Donald M. Kendall, chairman of PepsiCo -- which has established a bottling plant in the Soviet Union and distributes Soviet vodka here -- to see how food is processed in the United States, and from sea to shining sea they have visited plants of Hershey chocolate, Heinz soups and canned foods, Sara Lee frozen cakes and pastries, Kraftco cheese and margarine, Coors beer, Sun Maid raisins, Roma wine, Valley Foundry (winery equipment), Bird's Eye foods, Maxwell House coffee, Frito-Lay potato products, Tropicana orange juice, Pepsi-Cola bottling and Philip Morris cigarettes. While waiting for the President, the various national food ministers have been taking turns popping in and out of the chair with the little brass plate on the back which says THE PRESIDENT while a pal across the table takes snapshots of them in the highest seat of power. On the President's entrance everyone cools it and takes a Cabinet member's chair. Of all the establishments the Russians visited, the one minister Lein talks about with the most ursine joy is Disney World. FORD: Did you go in the Haunted House? LEIN: (rolling his eyes in terror): Da! Da! Da!

-- The President: A Minute-by-Minute Account of a Week in the Life of Gerald Ford by John Hersey (BOOK | KINDLE), a wonderful little book from 1975, by Hersey, a legendary journalist who was given unprecedented access to the Ford White House for a fly-on-the-wall report of a week following President Ford.

The President's chair in the Cabinet Room of the White House is always affixed with a brass plate labeled "THE PRESIDENT" along with the date of the President's inauguration. At the end of each President's term, they are given the opportunity to take the chair with them, but since it is government property, they are required to personally pay for it if they do so.

#History#Presidents#Presidential History#Presidency#Gerald Ford#President Ford#Ford Administration#Gerald R. Ford#Cabinet Room#White House#White House History#John Hersey#The President#The President: A Minute-by-Minute Account of a Week in the Life of Gerald Ford

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Vintage Paperback - The Child Buyer by John Hersey (1961)

Art by Sandy Kossin

Pocket Books

#Paperback Cover#Paperback Art#Sandy Kossin#Science Fiction#John Hersey#The Child Buyer#Pocket Books#Vintage#Art#Paperback#Paperbacks#1961#1960s#60s

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

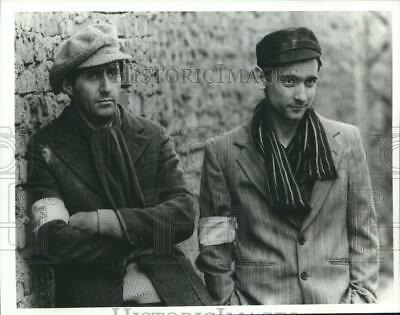

Tom Conti and Griffin Dunne in the 1982 TV film, THE WALL, about the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising in World War II.

#tom conti#griffin dunne#the wall 1982#the wall tv movie#John Hersey#warsaw ghetto uprising#wwii#world war ii

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

'...The new film comes after the success of Oppenheimer, a biopic about the man who created the bomb that was dropped on Hiroshima. “Oppenheimer ends and the bomb’s been dropped,” said the new film’s producer, Donald Rosenfeld. “We pick up at the bomb’s impact.

“Hersey gets permission from the US War Department to go into an absolutely closed zone – which is Hiroshima – as a reporter. Everyone from [US president Harry] Truman to generals were against it. They said: ‘This is not to be exposed at this point.’ Hersey went, and wrote what’s considered probably the greatest piece of experiential journalism in history.”...'

0 notes

Text

in case you need more evidence that history taught in american schools stops at the beginning of world war ii, today my boss asked me and my coworkers not to spoil oppenheimer because she has no idea what it's about

#i really really really hope she meant she didn't know how nolan chose to tell the story but that's not what it sounded like#girl pls we work at a trivia-based company we're supposed to know basic facts about history#full offense i think every american teenager needs to graduate high school having read hiroshima by john hersey#a shout into the void

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

I finally scored a copy of The War Lover by Hersey (whoo-hoo free from Thriftbooks! 11/10 love that site, please go check it out as well as BetterWorldBooks) and I'm very ????? about how it censors every swear. Something about writing "s—" is more jarring and offensive to me than just writing "shit".

We all know what's under there, Mr. Hersey, you don't... you really don't have to do that. It's okay. This book is literally about the inhumanity of war but we're not censoring that. Just let your characters say "shit".

#it made me giggle#anyway i've never read john hersey and now i'm wondering if it was something he always did as like. a choice? or#if it's because the book was published in the 1950s.#merri mumbles

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

"&" Ampersand - A Literary Companion

Selected stories with the themes of Bastille's upcoming project "&" Ampersand. And, of course, a love letter to my favourite band.

PART 1

Intros & Narrators: Wallace, David Foster. Oblivion: Stories. Little, Brown and Company, 2004./ Nancherla, Aparna. Unreliable Narrator: Me, Myself, and Impostor Syndrome. Penguin Publishing Group, 2023.// Eve & Paradise Lost: Bohannon, Cat. Eve: How the Female Body Drove 200 Million Years of Human Evolution. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, 2023. / Milton, John. Paradise Lost. Alma Classics, 2019.// Emily & Her Penthouse In The Sky: Dickinson, Emily. Emily Dickinson’s Poems: As She Preserved Them. Harvard University Press, 2016. /Dickinson, Emily. Emily Dickinson: Letters. Edited by Emily Fragos, Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, 2011.// Blue Sky & The Painter: Prideaux, Sue. Edvard Munch: Behind the Scream. Yale University Press, 2019. / Knausgaard, Karl Ove. So Much Longing in So Little Space: The Art of Edvard Munch. Random House, 2019.//

PART 2

Leonard & Marianne: Hesthamar, Kari. So Long, Marianne: A Love Story - Includes Rare Material by Leonard Cohen. Ecw Press, 2014./ Cohen, Leonard. Book of Longing. Penguin Books Limited, 2007.// Marie & Polonium: Curie, Eve. Madame Curie. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, 2013./Sobel, Dava. The Elements of Marie Curie: How the Glow of Radium Lit a Path for Women in Science. Atlantic Monthly Press, 2024.// Red Wine & Wilde: Wilde, Oscar, et al. De Profundis. Harry N. Abrams, 1998./ Sturgis, Matthew. Oscar: A Life. Head of Zeus, 2018.// Seasons & Narcissus: Ovid. Metamorphoses: A New Verse Translation. Penguin, 2004./ Morales, Helen. Antigone Rising: The Subversive Power of the Ancient Myths. PublicAffairs, 2020.//

PART 3

Drawbridge & The Baroness: Rothschild, Hannah. The Baroness: The Search for Nica, the Rebellious Rothschild. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, 2013./ Katz, Judy H. White Awareness: Handbook for Anti-racism Training. University of Oklahoma Press, 1978.// The Soprano & Her Midnight Wonderings: Ardoin, John, and Gerald Fitzgerald. Callas: The Art and the Life. Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1974./ Abramovic, Marina. 7 Deaths of Maria Callas. Damiani, 2020.// Essie & Paul: Ransby, Barbara. Eslanda: The Large and Unconventional Life of Mrs. Paul Robeson. Haymarket Books, 2022./ Robeson, Paul. Here I Stand. Beacon Press, 1998.//

PART 4

Mademoiselle & The Nunnery Blaze: Gautier, Theophile. Mademoiselle de Maupin. Penguin Classics, n.d./ Gardiner, Kelly. Goddess. HarperCollins, 2014.// Zheng Yi Sao & Questions For Her: Chang-Eppig, Rita. Deep as the Sky, Red as the Sea. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2023./ Borges, Jorge Luis. A Universal History of Infamy. Penguin Books, 1975. // Telegraph Road 1977 & 2024: Kaufman, Bob. Golden Sardine. City Lights Books, 1976./ Wolfe, Tom. The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test. Pan Macmillan Australia Pty, Limited, 2008.

Original artwork created by Theo Hersey & Dan Smith. Printed letterpress at The Typography Workshop, South London.

184 notes

·

View notes

Text

Not that many care about my opinion on the topic, but I cannot comprehend the takes I've seen on Oppenheimer prior to viewing the film.

I'm just out of the cinema and I cannooooot believe that I've heard and seen people complain about the "Americans clapping" scene as not sensitive, and that it should have shown the bombs dropped and the damage done. I've read takes that came down to 'the film is PRAISING the bomb by refusing to show its damage' and holy shit I was bracing myself.

But not only is the clapping scene shot like the genre just switched to horror, plunging us into very interesting exploration of the mental dissonance Oppenheimer is going through at that moment... I was left wondering...

Have those critics not seen Grave of the Fireflies? Barefoot Gen? In This Corner of the World? Watched documentaries on the bombs, on hibakushas? Have they not read the Hiroshima book by John Hersey that collects horrifying first hand accounts of Hiroshima survivors?

Have they stepped into the theatre with no background understanding of the atomic bomb and the horrors it carried?

Because this entire scene, actually much of Oppenheimer's mindset post bomb drop, DEPENDS on the public's understanding of WHAT THE PEOPLE ARE CLAPPING FOR. They're clapping for their project completion, for their victory, and for unknown amount of dead people. And WE KNOW that they are clapping for some of the most horrifying shit ever. We know they're clapping the cold war and nuclear proliferation's birth.

The film relies on you understanding this! The film depends on you activating your neurons and putting 2 and 2 together.

The film treats the audience as adults who don't need to see dead civilians to EMPATHISE for those civilians. You're also meant to be alienated from these cheering scientists, just as you can't help understanding why they're cheering.

It makes sense yet it's awful. Dissonance.

If you need your hand held so bad to understand why the bomb is a great evil, no matter how necessary it might have felt, when watching a biopic, then maybe you should have stuck to Barbie only, as that film was fun but significantly less challenging.

Also damn but Gary Oldman as Truman was so terrific, this guy really is a million faces.

473 notes

·

View notes

Text

☾ book recommendations: *✲⋆.

my all time favorites:

the brothers karamazov by fyodor dostoevsky

notes from underground by fyodor dostoevsky

the picture of dorian gray by oscar wilde

frankenstein by mary shelly

the plague by albert camus

we have always lived in the castle by shirley jackson

the seven who were hanged by leonid andreyev

blackshirts & reds by michael parenti

others that i'd recommend:

break the body, haunt the bones by micah dean hicks

tomie by junji ito

uzumaki by junji ito

berserk by kento miura

the haunting of hill house by shirley jackson

i have no mouth, and i must scream by harlan ellison

the tell-tale heart by edgar allen poe

the cask of amontillado by edgar allen poe

rebecca by daphne du maurier

wuthering heights by emily brontë

dune by frank herbert

a shadow over innsmouth by h. p. lovecraft

the color out of space by h. p. lovecraft

the dunwich horror by h. p. lovecraft

crime and punishment by fyodor dostoevsky

demons by fyodor dostoevsky

the idiot by fyodor dostoevsky

jane eyre by charlotte brontë

do androids dream of electric sheep? by philip k. dick

a long fatal love chase by louisa may alcott

the stranger by albert camus

the metamorphosis by franz kafka

the trial by franz kafka

dragonwyck by anya seton

discipline and punish by michel foucalt

the castle of otranto by horace walpole

faust by johann wolfgang von goethe

the fall by albert camus

the myth of sisyphus by albert camus

the strange case of dr jekyll and mr hyde by robert louis stevenson

blood meridian by cormac mccarthy (do look into the content warnings though, there's heavy violence/depictions of 1840s-1850s racism)

the death of ivan ilyich by leo tolstoy

the dead by james joyce

the overcoat by nikolai gogol

dead souls by nikolai gogol

hiroshima by john hersey

useful fictions: evolution, anxiety, and the origins of literature by michael austin

no exit by jean paule satre

candide by voltaire

white nights by fyodor dostoevsky

notes from a dead house by fyodor dostoevsky

the shock doctrine by naomi klein

the 100 year war on palestine by rashid khalidi

killing hope by william blum

the karamazov case: dostoevsky’s argument for his vision by terrence w. tilley

stiff: the curious life of human cadavers by mary roach

lazarus by leonid andreyev

imperialism, the highest stage of capitalism by vladmir lenin

the viy by nikolai gogol

dracula by bram stoker

carmilla by sheridan le fanu

nine coaches waiting by mary stewart

570 notes

·

View notes

Note

You used to list the books you've been reading every few weeks but I haven't seen a post like that in a minute. Anything good that you've been reading?

It has been a long time since I last posted one of those lists of recent reads -- probably about six months, so I'm not going to list everything I've read since then. And I don't remember exactly what I included last time, so hopefully I don't double-dip.

•Martin Van Buren: America's First Politician [2024] by James M. Bradley (BOOK | KINDLE | AUDIO) If you want to make me happy, just publish a new book about one of America's more obscure Presidents. And in December 2024, we got a new biography of Martin Van Buren with fresh research from sources not previously available to earlier biographers, resulting in an updated, comprehensive book about Van Buren that now becomes one of the definitive biographies of our eighth President.

•Lincoln vs. Davis: The War of the Presidents [2024] by Nigel Hamilton (BOOK | KINDLE | AUDIO) I'm also an easy mark for books about Jefferson Davis -- not out of any sort of affinity for him or the Confederacy, of course -- but just because of his unique place in history as an American President who also wasn't really an American President (although, technically, he was.) Throw Lincoln into the mix and you don't have to sell me very hard on this book.

•Night of Power: The Betrayal of the Middle East [2024] by Robert Fisk (BOOK | KINDLE | AUDIO) I wish Fisk had lived to write about the latest Israeli-Palestinian conflict, but it doesn't require much imagination to know what he would have thought about it: he wrote honestly, critically, and with deep understanding about the subject for 40+ years while reporting from the heart of the struggle in the Middle East.

•The Garfield Orbit [1978] by Margaret Leech and Harry J. Brown (BOOK)

•The World and Richard Nixon [1987] by C.L. Sulzberger (BOOK)

•John Lewis: A Life [2024] by David Greenberg [2024] (BOOK | KINDLE | AUDIO)

•Land Between the Rivers: A 5,000-Year History of Iraq [2024] by Bartle Bull (BOOK | KINDLE | AUDIO)

•The Hollow Crown: Shakespeare On How Leaders Rise, Rule, and Fall [2023] by Eliot A. Cohen (BOOK | KINDLE | AUDIO)

•A Very Personal Presidency: Lyndon Johnson in the White House [1968] by Hugh Sidey (BOOK)

•The Jesuit Disruptor: A Personal Portrait of Pope Francis [2024] by Michael W. Higgins (BOOK | KINDLE)

•The President: A Minute-by-Minute Account of a Week in the Life of Gerald Ford [1975] by John Hersey (BOOK | KINDLE)

•The Lone Star: The Life of John Connally [1989] by James Reston Jr. (BOOK)

•The Showman: Inside the Invasion That Shook the World and Made a Leader of Volodymyr Zelensky [2024] by Simon Shuster (BOOK | KINDLE | AUDIO)

•Alexander at the End of the World: The Forgotten Final Years of Alexander the Great [2024] by Rachel Kousser (BOOK | KINDLE | AUDIO)

•American Gothic: The Story of America's Legendary Theatrical Family -- Junius, Edwin, and John Wilkes Booth [1992] by Gene Smith (BOOK | KINDLE)

•Pathfinder: John Charles Frémont and the Course of American Empire [2002] by Tom Chaffin (BOOK | KINDLE | AUDIO)

•A Brief History of the World in 47 Borders: Surprising Stories Behind the Lines on Our Maps [2024] by Jonn Elledge (BOOK | KINDLE | AUDIO)

•Eisenhower For Our Time [2024] by Steven Wagner (BOOK | KINDLE | AUDIO)

•The Ends of the Earth: A Journey to the Frontiers of Anarchy [1996] by Robert D. Kaplan (BOOK | KINDLE)

•The Emperor: Downfall of an Autocrat [1983] by Ryszard Kapuściński [Translated by William R. Brand & Katarzyna Mroczkowska-Brand] (BOOK)

•A Heartbeat Away: The Investigation and Resignation of Vice President Spiro T. Agnew [1974] by Richard M. Cohen and Jules Witcover (BOOK)

•American Roulette: The History and Dilemma of the Vice Presidency [Revised & Updated, 1972] by Donald Young (BOOK)

•Centers of Power in the Arab Gulf States [2024] by Kristian Coates Ulrichsen (BOOK | KINDLE)

•The Formation of the UAE: State-Building and Arab Nationalism in the Middle East [2024] by Kristi Barnwell (BOOK | KINDLE)

•Iranian-Saudi Rivalry Since 1979: In the Words of Kings and Clerics [2023] by Talal Mohammad (BOOK | KINDLE)

•The Wrong Stuff: How the Soviet Space Program Crashed and Burned [2024] by John Strausbaugh (BOOK | KINDLE | AUDIO)

#Books#Reading#Recent Reads#Reading List#Book Suggestions#What I've Been Reading#Book Recommendations#Martin Van Buren: America's First Politician#James M. Bradley#Lincoln vs. Davis: The War of the Presidents#Nigel Hamilton#Night of Power: The Betrayal of the Middle East#Robert Fisk#The Garfield Orbit#The World and Richard Nixon#C.L. Sulzberger#John Lewis: A Life#David Greenberg#Land Between the Rivers#Bartle Bull#The Hollow Crown#Eliot A. Cohen#A Very Personal Presidency: Lyndon Johnson in the White House#Hugh Sidey#The Jesuit Disruptor: A Personal Portrait of Pope Francis#Michael W. Higgins#The President: A Minute-by-Minute Account of a Week in the Life of Gerald Ford#John Hersey#The Lone Star: The Life of John Connally#James Reston Jr.

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

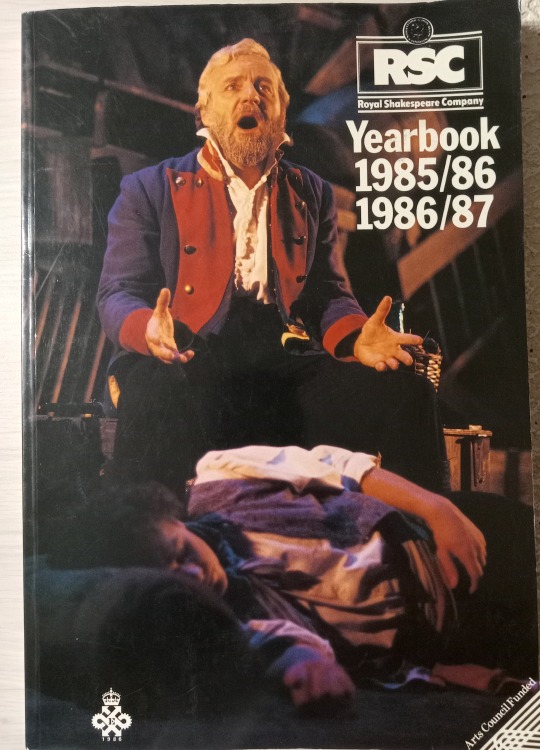

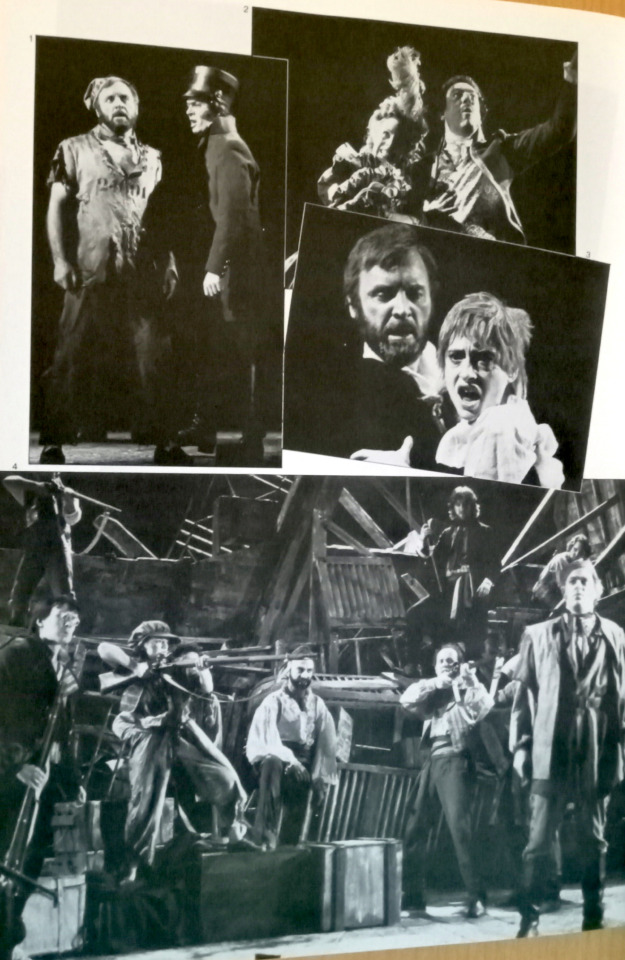

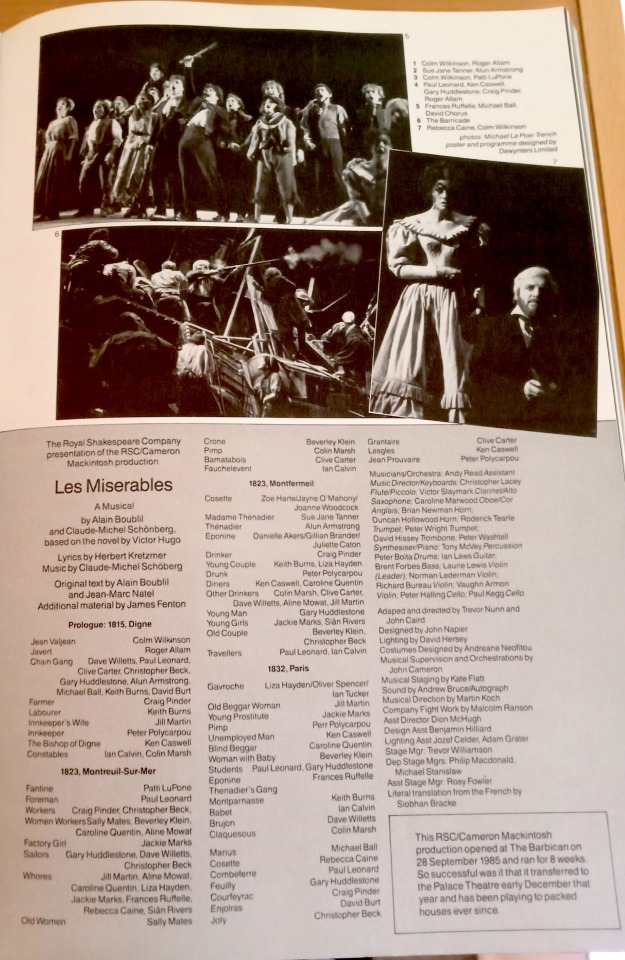

Happy 39th birthday to the London production of Les Misérables (which officially opened on 8 October 1985 at the Barbican Theatre, though previews began at the end of September)! By way of celebrations, scans from the 1985/86 / 1986/87 Royal Shakespeare Company Yearbook, which honoured the success of the Barbican production and its transfer to the Palace Theatre by making Colm Wilkinson and Michael Ball during 'Bring Him Home' its cover stars. The annual RSC Yearbook summarised productions in all of the company's (at the time five) theatres and on tour with production photography and critical commentary from newspapers and other media. Text from the pages above is under the cut below, with bracketed extra information to clarify some references.

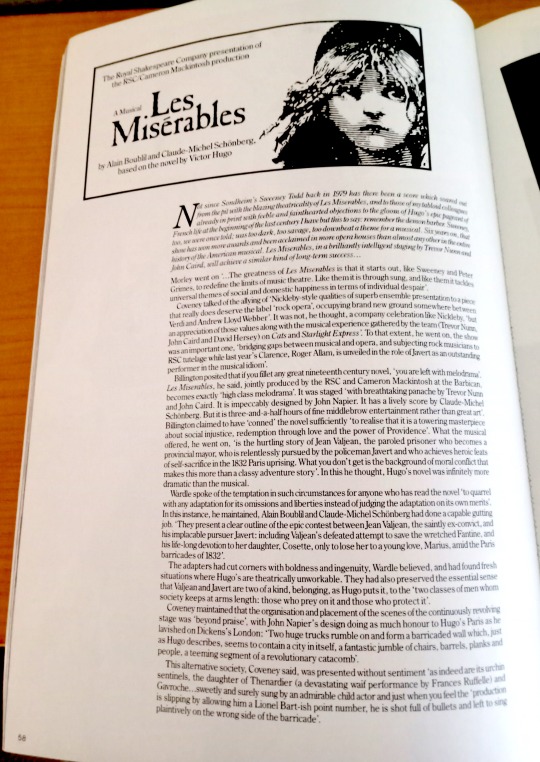

Not since Sondheim’s Sweeney Todd back in 1979 has there been a score which soared out of the pit with the blazing theatricality of Les Misérables, and to those of my tabloid colleagues already in print with feeble and fainthearted objections to the show, I have but this to say: remember the demon barber. Sweeney, too, we were once told; was too dark, too savage, too downbeat a theme for a musical. Six years on, that show has won more awards and been acclaimed to more opera houses than any other in the entire history of the American musical. Les Misérables, in a brilliantly intelligent staging by Trevor Nunn and John Caird, will achieve a similar kind of long-term success …

[The Times’/Punch’s Sheridan] Morley went on. ‘… The greatness of Les Misérables is that it starts out, like Sweeney and Peter Grimes, to redefine the limits of music theatre. Like them it is through sung, and like them it tackles universal themes of social and domestic happiness in terms of individual despair.’

[The Financial Times’ Michael] Coveney talked of the allying of ‘Nickleby*-style qualities of ensemble presentation to a piece that really does deserve the label ‘rock opera’, occupying brand new ground somewhere between Verdi and Andrew Lloyd Webber. It was not, he thought, a company celebration like Nickleby, ‘but an appreciation of those values along with the musical experience gathered by the team (Trevor Nunn, John Caird and David Hersey) on Cats and Starlight Express.’ To that extent, he went on, the show was an important one, ‘bridging gaps between musical and opera, and subjecting rock musicians to RSC tutelage while last year’s Clarence [in the RSC 1984 production of Richard III], Roger Allam, is unveiled in the role of Javert as an outstanding performer in the musical idiom.’

[*The RSC's landmark 1980 production of an adaption of Charles Dickens’ The Life and Adventures of Nicholas Nickleby]

[The Guardian’s Michael] Billington posited that if you fillet any great nineteenth-century novel, ‘you are left with melodrama.’ Les Misérables, he said, jointly produced by the RSC and Cameron Mackintosh at the Barbican, becomes exactly ‘high class melodrama.’ It was staged ‘with breathtaking panache by Trevor Nunn and John Caird. It is impeccably designed by John Napier. It has a lively score by Claude-Michel Schönberg. But it is three-and-a-half hours of fine middlebrow entertainment rather than great art.’ Billington claimed to have ‘conned’ the novel sufficiently ‘to realise that it is a towering masterpiece about social injustice, redemption through love and the power of Providence.’ What the musical offered, he went on, ‘is the hurtling story of Jean Valjean, the paroled prisoner who becomes a provincial mayor, who is relentlessly pursued by the policeman Javert and who achieves heroic feats of self-sacrifice at the 1832 Paris uprising. What you don’t get is the background of moral conflict that makes this more than a classy adventure story.’ In this he thought, Hugo’s novel was infinitely more dramatic than the musical.

[The Times’ Irving] Wardle spoke of the temptation in such circumstances for anyone who has read the novel ‘to quarrel with any adaptation for its omissions and liberties instead of judging the adaptation on its own merits.’ In this instance, he maintained, Alain Boublil and Claude-Michel Schönberg had done a capable gutting job. ‘They present a clear outline of the epic contest between Jean Valjean, the saintly ex-convict, and his implacable pursuer Javert: including Valjean’s defeated attempt to save the wretched Fantine, and his life-long devotion to her daughter, Cosette, only to lose her to a young love, Marius, amid the Paris barricades of 1832.’

The adapters had cut corners with boldness and ingenuity, Wardle believed, and had found fresh situations where Hugo’s are theatrically unworkable. They had also preserved the essential sense that Valjean and Javert are two of a kind, belonging, as Hugo puts it, to the ‘two classes of men whom society keeps at arms length: those who prey on it and those who protect it.’

Coveney maintained that the organization and placement of the continuously revolving stage was ‘beyond praise’, with John Napier’s design doing as much honour to Hugo’s Paris as he lavished on Dickens’s London [in Nickleby]: ‘Two huge trucks rumble on and form a barricaded wall which, just as Hugo describes, seems to contain a city in itself, a fantastic jumble of chairs, barrels, planks and people, a teeming segment of a revolutionary catacomb.’

This alternative society, Coveney said, was presented without sentiment ‘as indeed are its urchin sentinels, the daughter of Thenardier (a devastating waif performance by Frances Ruffelle) and Gavroche … sweetly and surely sung by an admirable child actor and just when you feel the production is slipping by allowing a [writer of Oliver] Lionel Bart-ish point number, he is shot full of bullets and left to sing plaintively on the wrong side of the barricade.’

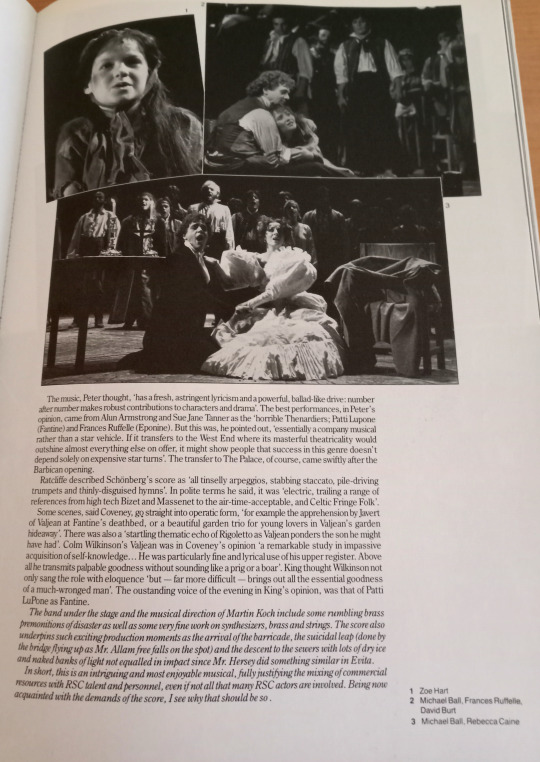

The music, [The Sunday Times’ John] Peter though, ‘has a fresh, astringent lyricism and a powerful, ballad-like drive: number after number makes robust contributions to character and drama.’ The best performances, in Peter’s opinion, came from Alun Armstrong and Susan Jane Tanner as the ‘horrible Thenardiers', Patti LuPone (Fantine) and Frances Ruffelle (Eponine). But this was, he pointed out, ‘essentially a company musical rather than a star vehicle. If it transfers to the West End where its masterful theatricality would outshine almost anything else on offer, it might show people that success in this genre doesn’t depend solely on expensive star turns.’ The transfer to the Palace, of course, came swiftly after the Barbican opening.

[The Observer’s Michael] Ratcliffe described Schönberg’s score as ‘all tinselly arpeggios, stabbing staccato, pile-driving trumpets and thinly-disguised hymns.’ In polite terms he said, it was ‘electric, trailing a range of references from high-tech Bizet and Massenet to the air-time acceptable, and Celtic Fringe Folk.’

Some scenes, said Coveney, go straight into operatic form, ‘for example the apprehension by Javert of Valjean at Fantine’s deathbed, or a beautiful garden trio for young lovers in Valjean’s garden hideaway.’ There was also a ‘startling thematic echo of Rigoletto as Valjean ponders the son he might have had.’ Colm Wilkinson’s Valjean was in Coveney’s opinion ‘a remarkable study in impassive acquisition of self-knowledge … He [has] particularly fine and lyrical use of his upper register. Above all he transmits palpable goodness without sounding like a prig or a boar [bore?].’ [The Sunday’s Telegraph’s Francis] King thought Wilkinson not only sang the role with eloquence ‘but – far more difficult – brings out the essential goodness of a much-wronged man.’ The outstanding voice of the evening in King’s opinion, was that of Patti LuPone as Fantine.

The band under the stage and the musical direction of Martin Koch include some rumbling brass premonitions of disaster as well as some very fine work on synthesizers, brass and strings. The score also underpins such exciting production movements as the arrival of the barricade, the suicidal leap (done by the bridge flying up as Mr Allam free falls on the spot) and the descent to the sewers with lots of dry ice and naked banks of light not equalled in impact since Mr Hersey did something similar in Evita.

In short, this is an intriguing and most enjoyable musical, fully justifying the mixing of commercial resources with RSC talent and personnel, even if not all that many RSC actors are involved.* Being now acquainted with the demands of the score, I see why that should be so. [Morley]

[* The RSC members who appeared in the Barbican production were Roger Allam, Alun Armstrong, and Susan Jane Tanner. Other RSC members at this time joined Les Mis in later companies, among them David Delve, who would replace Alun Armstrong as Thenardier.]

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

By Emily Strasser | August 9, 2023

At the theater where I saw Oppenheimer on opening night, there was a handmade photo booth featuring a pink backdrop, “Barbenheimer” in black letters, and a “bomb” made of an exercise ball wrapped in hoses. I want to tell you that I flinched, but I laughed and snapped a photo. It took a beat before I became horrified—by myself and the prop. Today is the 78th anniversary of the bombing of Nagasaki, which killed up to 70,000 people and came only three days after the bombing of Hiroshima that killed as many as 140,000 people. Yet still we make jokes of these weapons of genocide.

Oppenheimer does not make a joke of nuclear weapons, but by erasing the specific victims of the bombings, it repeats a sanitized treatment of the bomb that enables a lighthearted attitude and limits the power of the film’s message. I know this sanitized version intimately, because my grandfather spent his career building nuclear weapons in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, the site of uranium enrichment for the Hiroshima bomb. My grandfather died before I was born, and though there were photographs of mushroom clouds from nuclear tests hanging on my grandmother’s walls, we never discussed Hiroshima, Nagasaki, or the fact that Oak Ridge, still an active nuclear weapons production site, is also a 35,000-acre Superfund site. At the Catholic church in town, a pious Mary stands atop an orb bearing the overlapping ovals symbolizing the atom, and until it closed a few years ago, a local restaurant displayed a sign with a mushroom cloud bursting out of a mug of beer.

Oppenheimer does not show a single image of Hiroshima or Nagasaki. Instead, it recreates the horror through Oppenheimer’s imagination, when, during a congratulatory speech to the scientists of Los Alamos after the bombing of Hiroshima, the sound of the hysterically cheering crowd goes silent, the room flashes bright, and tatters of skin peel from the face of a white woman in the audience. The scene is powerful and unsettling, and, arguably, avoids sensationalizing the atrocity by not depicting the victims outright. But it also plays into a problematic pattern of whitewashing both the history and threat of nuclear war by appropriating the trauma of the Japanese victims to incite fear about possible future violence upon white bodies. An example of this pattern is a 1948 cover of John Hersey’s Hiroshima, which featured a white couple fleeing a city beneath a glowing orange sky, even though the book itself brought the visceral human suffering to American readers through the eyes of six actual survivors of the bombing.

The Oppenheimer film also neglects the impacts of fallout from nuclear testing, including from the Trinity test depicted in the film; the harm to the health of blue-collar production workers exposed to toxic and radiological materials; and the contamination of Oak Ridge and other production sites. Instead, the impressive pyrotechnics of the Trinity test, images of missile trails descending through clouds toward a doomed planet, and Earth-consuming fireballs interspersed with digital renderings of a quantum universe of swirling stars and atoms, elevate the bomb to the realm of the sublime—terrible, yes, but also awesome.

A compartmentalized project. The origins of this treatment can be traced to the Manhattan Project, when scientists called the bomb by the euphemistic code word “gadget” and the security policy known as compartmentalization limited workers’ knowledge of the project to the minimum necessary to complete their tasks. This policy helped to dilute responsibility and quash moral debates and dissent. Throughout the film, we see Oppenheimer move from resisting compartmentalization to accepting it. When asked by another scientist about his stance on a petition against dropping the bomb on Japan, he responds that the builders of the bomb do not have “any more right or responsibility” than anyone else to determine how it will be used, despite the fact that the scientists were among the few who even knew of its existence.

Due to compartmentalization, the vast majority of the approximately half-million Manhattan Project workers, like my grandfather, could not have signed the petition because they did not know what they were building until Truman announced the bombing of Hiroshima. Afterward, press restrictions limited coverage of the humanitarian impacts, giving the false impression that the bombings had targeted major military and industrial sites—and eliding the vast civilian toll and the novel horrors of radiation. Photographs and films of the aftermath, shot by Japanese journalists and American military, were classified and suppressed in the United States and occupied Japan.

The limit of theory. Not only is it dishonest and harmful to erase the suffering of the real victims of the bomb, but doing so moves the bomb into the realm of the theoretical and abstract. One recurring theme of the film is the limit of theory. Oppenheimer was a brilliant theorist but a haphazard experimentalist. A close friend and fellow scientist questions whether he’ll be able to pull off this massive, high-stakes project of applied theory. Just before the detonation of the Trinity test bomb, General Leslie Groves, the military head of the project, asks Oppenheimer about a joking bet overheard among the scientists regarding the possibility that the explosion would ignite the atmosphere and destroy the world. Oppenheimer assures Groves that they have done the math and the possibility is “near zero.” “Near zero?” Groves asks, alarmed. “What do you want from theory alone?” responds Oppenheimer.

Can the theoretical motivate humanity to action?

One telling scene shows Oppenheimer at a lecture on the impacts of the bomb. We hear the speaker describe how dark stripes on victims’ clothing were burned onto their skin, but the camera remains on Oppenheimer’s face. He looks at the screen, gaunt and glassy-eyed, for a few moments, before turning away. Americans are still looking away. As a country, we’ve succumbed to “psychic numbing,” as Robert Jay Lifton and Greg Mitchell call it in their book Hiroshima in America, which leads to general apathy about nuclear weapons—and pink mushroom clouds and bomb props for selfies.

On this anniversary of Nagasaki, the world stands on a precipice, closer than ever to nuclear midnight. The nine nuclear-armed states collectively possess more than 12,500 warheads; the more than 9,500 nuclear weapons available for use in military stockpiles have the combined power of more than 135,000 Hiroshima-sized bombs.

If Oppenheimer motivates conversation, activism, and policy shifts in support of nuclear abolition, that’s a good thing. But by relegating the bomb to abstracted images removed from actual humanitarian consequences, the film leaves the weapon in the realm of the theoretical. And as Oppenheimer says in the film, “theory will only take you so far.” Today, it’s vital that we understand the devastating impacts that nuclear weapons have had and continue to have on real victims of their production, testing, and wartime use. Our survival may depend on it.

81 notes

·

View notes

Text

idk why i keep thinking that Frank Woods would have a ranch somewhere? like there’s no animals or anything it’s just land and a comfortable little house dead in the middle of it

so of course he tells himself that it’s logical that afab Bell shows up at his doorstep like a beaten dog two months after the last time he saw her in Solovetsky, with less than ideally healed gunshot wounds from her second assassination attempt. Of course, it’s just that here’s a lot less likely that anyone would find her

And he takes her in, because it might’ve been fake for Adler but she’s fucking tore through hell right at Frank’s side with ample opportunity to either kill him herself or just let him get turned into mincemeat by the reds. She’s ended up under him more than once too, shaking and clumsy and laughing against his mouth in the residual adrenaline rush. More chances to off him, or to try and leverage his attraction to her, that she didn’t take. That Frank’s now convinced she wouldn’t take, not because she isn’t capable of it, she just likes sex too much to use it as a weapon.

She likes Frank too much for it, he realizes in the couple days it takes for her to stop looking over her shoulder with every creaking floorboard. When she asks him to drive her into town to exchange the small fortune in Swiss francs she smuggled into the country all the way from Zurich. He can’t fucking help it, the question that stumbles out of him without more than a second’s thought: ‘Why didn’t you go back to Perseus?’

Bell shifts, looks from Frank to the copy of John Hersey’s Hiroshima he’d given to her after a comment on nuclear armament even he thought was tasteless, the same book he caught her crying over months later and now sits in her bag, half buried in foreign bills.

‘I couldn’t,’ she says, then a minute later, as if it just occurred to her, ‘he’d kill me anyway, after Solovetsky’.

It takes a few more weeks for her to end up in his bed again, and she still smiles as soon as he nudges his dick inside her, still laughs at the burn of his beard on her neck. She still comes clutching onto him like he’ll disappear or leave, discard her as soon as he fills her. Bell mumbles out his name and Frank feels his heart caught between her fingers as much as his hair is at the moment, because for her that’s the most reasonable fear to have.

So he doesn’t. It’s not like he was gonna leave his own fucking house, which in a way feels like the only thing he’s ever really owned, but he won’t kick her out either. And he doesn’t mention her to a single soul who knows her, not even Mason. Especially not when she starts going out, more fearless each time; when she starts to teach a self defense class in town on Fridays or taking drives to the next county over whenever she has a nightmare, just to convince herself that she’s not in a fake town, and she comes back with a cheeseburger for him each time.

Cause then she starts to become his Bell again. The one capable of dead devotion, who chose to do the right thing in the end. The Bell that died twice and came back better every time, that saw an old worn fuck like him and called it home.

Bell, who he accidentally wakes one night when he comes sweating out of his own bad dreams and offers to join him for a cigarette out in the front porch, who convinces him to put on a sweater and settles on his lap in silence, blowing little smoke rings into the gold light of dawn.

The woman who cries against his shoulder when he lets spill that he loves her like horrible word vomit, and tells him she loves him too.

#m: cod#r: fluff#frank woods x reader#frank woods x bell#personal#i don’t know if i’m ever gonna write the full thing so this will suffice for now lol#the one where frank deprograms bell most effectively by having the most emotional bandwidth of them all#i always give bell some months to a year between the airstrip and the rest of the game so they don’t have to brainwash them in like 2 weeks#anyway i love this bell loyal as a working dog is loyal

122 notes

·

View notes

Text

'...What Nolan shows us

I just finished reading Justin Chang’s excellent interpretation of what Christopher Nolan tried to show or not show in his brilliant movie “Oppenheimer” [“‘Oppenheimer’ doesn’t show us Hiroshima and Nagasaki. That’s an act of rigor, not erasure,” Aug. 14]. The interpretation he offers is excellent, but I am writing to you in response to his final paragraph. So many times, film directors underestimate the intelligence of audiences. Nolan makes intelligent films and trusts his audiences to think for themselves. I thank Nolan for doing that, and I thank Mr. Chang for pointing out that he does.

Horace Morana San Luis Obispo

The criticism of “Oppenheimer’s” lack of showing the gruesome effects of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki is understandable [“Critics object to film’s victim erasure,” Aug. 7]. However, unless one has not read John Hersey’s “Hiroshima” or Robert Jay Lifton’s “Death in Life: Survivors of Hiroshima,” or watched the countless documentaries and movies about the bombings, you know what happened. To fault director Nolan for not showing the effects misses the point about the viewpoint of Oppenheimer.

Historian Paul Ham is probably right that the film “cannot help but be morally half-formed,” and his excellent book, “Hiroshima Nagasaki,” is convincing in that the bombings were unnecessary to win the war, but no feature film is likely to capture the full impact of the bomb’s history and effects. I hope that most “Oppenheimer” viewers will at least remember Nolan’s final point that nuclear war is still possible and that there must be an abolition of nuclear weapons to avoid more Hiroshimas and Nagasakis.

Bob Ladendorf Los Angeles...'

#Oppenheimer#Christopher Nolan#Paul Ham#Hiroshima Nagasaki#Death in Life: Survivors of Hiroshima#Robert Jay Lifton#John Hersey#Hiroshima

0 notes