#john and herla

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Cafae Latte Fanfic: Totally Not Friends

#creepy cafae latte#nicole cafae latte#cafae latte#cafae#whump#john and herla#slow burn#tiktok series#c.m. alongi#cm alongi#ghost hunter john#king herla#fanfic authors#ao3 fanfic#fanfic readers#fanfic#fanfic fanart#cafae latte fanfiction#all the whump#whump fic#because whump#if you read please review

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

John: Any ideas for lifelong projects or grudges?

Mike: Why would you want that?

John: Im planning how to become a ghost so I can annoy Herla for a few more years

76 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fuck it I'm writing a ghost hunter john X king herla oneshot about the aftermath of the most recent arc (??? Is that the right word to use lmao) in Cafae Latte's story because I have no life

I am now hoping it will not be too short because that will be pathetic

129 notes

·

View notes

Text

I think John and Herla would be cute together. Ghost hunter x ghost hunter, slow burn, rivals to lovers, 10k words multi chapter

120 notes

·

View notes

Text

So I've recently been thinking about the fact that in CaFae Latte, this is the first time Bob has had non fae employees. Before they took on JC as a contract baker it was just them.

Just imagine in 25 years or so the mortal crew starting to show signs of ageing and being unable to continue with their adventures. Bob starts worrying about their protection now they're less able to defend themselves against the supernatural they normally deal with and starts to distance herself from them. Slowly the cracks begin to form, they become larger as time passes until the distance feels as large as a canyon is wide.

Then Husniya passes. At first Bob thinks she made the right choice. Pushing her friends away to protect herself. But then she finds out she was gifted something in Husniyas will. It's a letter. Written a year or so before she passed, thanking Bob for trusting her, allowing her to remain in her life despite knowing she was spying. Allowing her to develop a genuine friendship with the fae. And forgiving her for pushing her away, full of understanding that Bob was genuinely afraid for her friends and scared to get hurt. And encouraging her to mend fences before too much time passes.

Bob starts regretting the distance she built between her and her mortal friends. Unsure of what to do she contacts Herla, wanting to hear she did the right thing keeping her distance. He doesn't agree. Instead he only repeats what she told him when he asked why she surrounded herself with humans.

"Much of life is short, Herla. I'd rather savour the good moments than dread the day they end. I'm much happier that way- That's what you told me when I asked why you surrounded yourself with so many humans. When did you become so guarded that you lost sight of your own opinions?" Bob leaves without responding. His-Her? Words running around her head. They don't leave, pestering her, keeping her up until late into the night. She doesn't know when she starts pushing her friends away, only that she doesn't want to waste the precious years she has left with them.

She starts reaching out slowly.

First to Nicole, who understands where she was coming from, full of the same understanding Husniya had. Reassuring her that she doesn't hold bobs mistakes against her, she never has and never will. And promises to start softening JC up to the idea of reconciliation, knowing it would be hard for her partner to let someone back in after what they perceive to be a large betrayal.

Next she reaches out to Mike, he like Nicole before him gave his forgiveness and invites her and Cyrus to the next holiday gathering at the coven.

Then she tries to reach out to john. Only to find put he passed a few years before Husniya. She grieves for a friend but knows he has joined the rest of is family in the afterlife.

After John it takes her a while to reach out to Lindsey. But when she does she finds out word of her ending her self imposed human isolation has spread. Lindsey is neutral towards Bob. Understanding the reason for Bob pushing them away but unable to let go some of the hurt it caused. Especially as Bob was the one to help her turn her life around and make something of it instead of being stuck in a low paying unfufilling job for the rest of her life.

By the time Bob reaches out to JC Nicole has been able to convince them that they should at least listen to Bob's reasoning. They meet for coffee. By the end of the discussion JC has agreed to attempt at a friendship on a trial basis. In Bob's opinion this is more than she deserved. Especially after the way she pushed everyone away after years of friendship. But thankful for the grace they have decided to give her

90 notes

·

View notes

Text

Herla having a mental breakdown realizing he's into John, a feeling in his gut that he's betraying his old family and it won't go away so he pushes John away until John and/or the cafe crew slap some sense into him

28 notes

·

View notes

Note

Sorry to bug you but can you doodle your interpretation of ghost hunter john? cause that sounds found lol (The new arc made me like his character even more i need more content of him sorry)

Heres how I imagine the man!! I really like his dynamic with herla

I did this during class from memory lol

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

a compelation of Cafae Latte ideas that have been bouncing around in my head that knowing me aren't going to ever get written down at all (yes, all of these involve Erik in some way)

Erik develops Hanahaki for someone who isn't his coworkers fic that my brain is using to focus on Erik's feelings about mortality than the romance aspect I usually read Hanahaki for

Cyrus, Drek and Erik having a hang out go sideways when they accidentally make contact with a magical object that sticks them in a time loop, featuring all three of them dying at some point during the looping

Sequal to the time loop idea where thanks to the time loop, Erik and Drek have temporary immortality and are sent to shadow Herla and John until the immortality wears off on both of them. Cue shenanigans

Oscar and Erik getting trapped in a haunted church in a "the Faenapping arc didn't happen" au.

Varying shenanigans surrounding JC, Nicole, Erik, Drek, Cyrus and Rethu having a sleepover in the Cafae Latte building itself. The only specific that I can give is that the sleepover was Drek's idea because the scenario keep rotating too much for me to really remember details about specific scenarios without writing it down

The customer interactions in an Omegaverse au. The only thing related to anyone's subgenders that my brain decided to provide is that Erik presented early while Drek presented late. What are anyone's subgenders, fuck if I know

AU where Erik didn't get hired because he became a ghost between the ages of 12-15. The list of things Erik has possessed includes a car and JC knows more about ghosts in this au than in canon

One of Herla's enemies kidnaps Erik post whatever incident that caused Erik and Herla to get along (said kidnappers failing to kidnap John may or may not be included) as a means to get at Herla indirectly and Herla just decides to go on a warpath. I blame this scenario for really getting me into the duo of Herla and Erik

Erik and John successfully make Herla watch the whole Ghostbusters franchise. Herla refuses to admit he cried at several different points

A ghost child gets attached to Erik and decides to follow Erik around like a baby duck

Someone from the church Erik used to attend turns into a ghost and ends up possessing Erik for reasons. Naturally, the reason behind the possession then becomes a problem for at minimum Bob and Erik, but most likely the entire staff

Cafae Latte musical series. More specifically a silly duet sung between Erik and JC shortly after Erik's introduced as a physical character having the reprise turn into Erik's villain song.

#I'm only partially sorry about bringing the omegaverse into this#the readmore is there for my own sanity later#cafae latte#erik cafae latte#i do not have the energy to tag everyone else rn

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

i love ghost hunter john and king herla i love them so much they areso funny

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Charles Robinson (1870-1937)

Born Oct 22, 1870 in Islington, London, Robinson was the son of an illustrator. Through the family trade, he, along with his brothers Thomas Heath Robinson and William Heath Robinson would also become illustrators. In his youth, he served an apprenticeship at Waterlow & Sons in Finsbury for seven years. At age 25 he was able to sell his work professionally. "He quickly developed his own unique style, based on the then contemporaneous influences of Pre-Raphaelitism and Art Nouveaux. Robinson was particularly inspired by the delicate watercolours of Aubrey Beardsley, Japanese artworks, and the woodcuts of the old masters such as Albrecht Dürer" (PookPress).

Among works include Robert Louis Stevenson's "A Child's Garden of Verses” (1895), his first full book commissioned by John Lane. Containing 100 pen and ink drawings, the book was well-received and went through "a number of print runs." Other works include Lilliput Lyrics (1899), Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, The Secret Garden, and The True Annals of Fairy Land: The Reign of King Herla. Robinson would also create illustrations for Golden Sunbeams children's magazine, and in 1899 the 3 Robinson Brothers collaborated on a version of Anderson's Fairy Tales.

Thanks to advances in printmaking, Robinson's generation was the first to display their illustrations as they really were, instead of relying on engravers to carve their images as in methods prior. This new method revolutionized illustration and allowed for an explosion of illustration in printed media.

---

sources:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_Robinson_%28illustrator%29 http://www.bpib.com/illustrat/robinson.htm http://www.pookpress.co.uk/project/charles-robinson-biography/ http://www.johncoulthart.com/feuilleton/2008/02/27/the-art-of-charles-robinson-1870-1937/

76 notes

·

View notes

Text

John Stuart Mill, een denker voor onze tijd

... in mijn werkkamer herlas ik deze week Over vrijheid van John Stuart Mill, vertaald door Wessel Krul, bij wie ik eens colleges volgde in Groningen. meer https://www.google.com/url?rct=j&sa=t&url=https://www.nrc.nl/nieuws/2020/03/14/john-stuart-mill-een-denker-voor-onze-tijd-a3993784&ct=ga&cd=CAIyGzdiZTM2OTAwNTFkODk0MDk6bmw6bmw6Tkw6Ug&usg=AFQjCNEkjdBG4lu9F49Huwv3zLAEZ7OTdQ

0 notes

Text

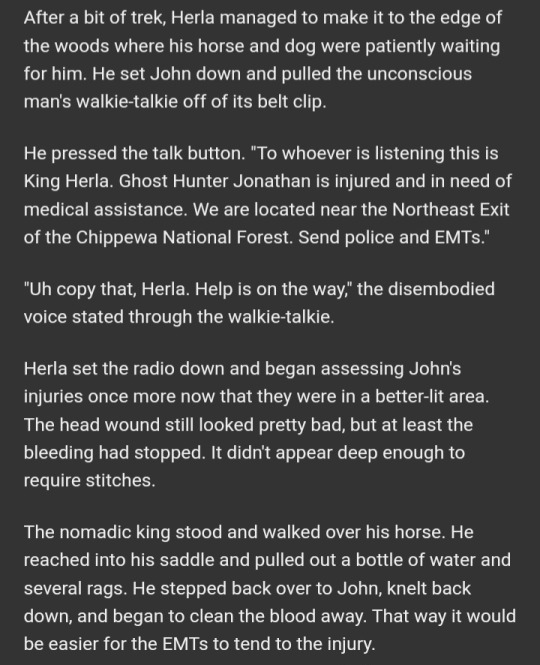

CaFae Latte Fanfic: Totally Not Friends

https://archiveofourown.org/works/60084961

If you read please consider leaving a review on AO3

Characters: Ghost Hunter John and King Herla

Summary: John is more than a little bit concussed. Herla takes John to the hospital and sits with him while he recovers from his injuries.

#fanfic authors#fanfic readers#ao3 fanfic#fanfic#whump#cafae latte fanfiction#creepy cafae latte#cafae latte#ghost hunter john#king herla#quick oneshot#cafae#cm alongi#c.m. alongi

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pierrot and Harlequin, Mardi Gras by Paul Cézanne, 1888

Origins

Atellana comedy

Plautus

Passion Plays

Arlecchino, as we know him, is a stock character dating back to seventeenth-century Commedia dell’arte. He also has origins in the atellana farce of Roman antiquity (4th century BCE). In fact, the use of stock characters is a feature of the atellana. Moreover Commedia dell’arte characters could be borrowed from commedia erudita. Molière‘s (1622 – 1673) Miser or L’Avare (1668) was borrowed from Plautus‘ (c. 254 – 184 BCE) Auluraria (The Pot of Gold).

However, in European countries, comedy has more immediate origins. It emerged as a brief mirthful form, a mere interlude, during lengthy medieval Passion Plays, Mystery Plays and Miracle Plays. Passion Plays were extremely long, so interludes, comedy, were inserted between the “acts” to keep the audience entertained. These became popular and eventually secularized the religious plays. However, Passion Plays have not disappeared totally. For instance, the Oberammergau Passion Play (Bavaria) has been performed since 1634, keeping alive the birthplace of farces and tom-foolery.

Harlequin

Hellequin, Herla, Elking

Tirstano Martinelli, the first Harlequin

Zanni (servants)

British harlequinades (eighteenth-century)

It would appear that the commedia dell’arte’s Arlecchino (Harlequin) was also culled out of Passion Plays, where he was a devil: Hellequin, Herla, Erlking and other spellings and names. The origin of the name is attested by 11th-century chronicler Orderic Vitalis (1075 – c. 1142). The name Harlequin was picked up in France by Tristano Martinelli, the first actor to play Harlequin. (See Harlequin, Wikipedia.)[i] Tristano played the role of Harlequin from the 1580s until his death in 1630. At this point, Harlequin became a stock character, an archetype, in the Commedia dell’arte. Given that the success of the Commedia dell’arte performances depended on an actor’s skills, we can presume Tristano was a fine comedian.

Arlecchino (Arlequin, Harlequin) is a zanno, a servant whose function was called Sannio in the Atellana, Roman farcical comedies. There were many zanni, (Brighella, Pulchinello, Mezzetin, Truffadino, Beltrame, and others). Their role was to help the young lovers of comedy overcome obstacles to their marriage. This plot is consistent with the “all’s well that ends well” of all comedies. We have already met the blocking characters of the commedia dell’arte. Pantalone is the foremost. But his role may be played by Il Dottore, or Il Capitano, or some other figure.

Although a zanno has the same function from play to play, as do blocking characters, the alazôn, zanni otherwise differ from one another. For instance, Arlecchino, a zanno, is different from Pierrot. Harlequin is not the growingly sadder clown of Romantic and pantomimic incarnations. He is not Jean-Gaspard Deburau‘s Battiste, nor is he Jean-Louis Barrault‘s Baptiste. He is the clever, nimble, but clownish zanno.

Harlequin’s Characteristics

Arlecchino is, in fact, the most astute and nimble of zanni or servants. He is an acrobat. This is one of his main attributes. Moreover, he wears a costume of his own, another distinguishing factor.

At first, the Harlequin wore a black half mask and a somewhat loose costume on which diamond-shaped coloured patches had been sewn. He would then wear a tight-fitting chequered costume mixing two or several colours. Paul Cézanne‘s (1839–1906) Harlequin is dressed in black and red, but Pablo Picasso changes the colours worn by his numerous Harlequins.

Harlequin leaning (Harlequin accoudé) by Picasso, 1901

Les Deux Saltimbanques (Two Acrobats) by Picasso, 1901

Arlequin’s Progress

the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries in France

Blois

I Gelosi

Petit-Bourbon

Scenario

In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the Italians were very popular at the French court and so was Harlequin. As of 1570-71, Commedia dell’arte actors were summoned by the King of France to perform in royal residences. In 1577, the Italians were called to Blois by Henri III during an assembly of Parliament. The famous I Gelosi (The Jealous Ones; 1569-1604) “was the first troupe to be patronized by nobility: in 1574 and 1577 they performed for the king of France.” (See I Gelosi, Wikipedia.) La Commedia dell’arte most famous performers in seventeenth-century France were Isabella and Francesco Andreini. Isabella died in childbirth (1604), but her son’s troupe, the Compagnia dei Fedeli would be invited to perform at Louis XIII’s court.

In short, in the seventeenth century, Harlequin was in France. In fact, at one point, les Italiens shared quarters with Molière at the Petit-Bourbon, a theatre. Matters changed in 1697, when the commedia performed a “fausse prude” (false prude) scenario that offended Madame de Maintenon (27 November 1635 – 15 April 1719), Louis XIV‘s second wife. In French seventeenth-century representations, Pierrot loved Columbine who loved Harlequin (Arlecchino).

Commedia dell’arte troupe, probably depicting Isabella Andreini and the Compagnia dei Gelosi, oil painting by unknown artist, c. 1580; in the Musée Carnavalet, Paris (Photo credit: Britannica)

Pulcinella, by Maurice Sand

John Rich, as Harlequin

British Harlequinades: Pantomime & Slapstick

pantomime

slapstick

Pulcinella (Polichinelle, Punchinella)

“Punch and Judy”

a new scenario

In eighteenth-century Britain, John Rich[ii] (1682 – 26 November 1761, the son of one of the owners of Drury Lane Theatre and the founder of Covent Garden Theatre (Royal Opera House) performed the above-mentioned harlequinades in which “he combined a classical fable with a grotesque story in Commedia dell’arte style involving Harlequin and his beloved Columbine.”[iii] In Britain, harlequinades, became “that part of a pantomime in which the Harlequin and clown play the principal parts.”[iv] Harlequinades also contained a Transformation Scene.[v] Associated with the British Harlequin are pantomime, slapstick comedy and puppetry. Yet, this British Harlequin is rooted in the sixteenth-century Commedia dell’arte. It seems that the best of these English clowns was played by Joseph Grimaldi (18 December 1778 – 31 May 1837).

However, British harlequinades also featured Pulcinella who originated in the seventeenth-century Commedia dell’arte but had roots in Atellana comedy and was a stock character in Neapolitan puppetry. Given his ancestry, Pulcinella could and did inspire Mister Punch of “Punch and Judy,” a puppet show. (See Harlequin, Wikipedia.)

British harlequinades differ from continental versions of Arlequin (FR) or Arlecchino.

“First, instead of being a rogue, Harlequin became the central figure and romantic lead. Secondly, the characters did not speak; this was because of the large number of French performers who played in London, following the suppression of unlicensed theatres in Paris.” (See Harlequin, Wikipedia.)

It seems harlequinades were played in “Italian Night Scenes,” following a main and serious performance. In their scenario, “Italian Night Scenes” focused on Harlequin who loved Columbine but was opposed by a greedy Pantalone, Columbine’s father. Pantalone would chase the young lovers “in league with the mischievous Clown; and the servant, Pierrot, usually involving chaotic chase scenes with a policeman.” Moreover the “night scenes” started to grow longer to the detriment of the previous performance. (See Harlequinade, Wikipedia.)

In other words, in Britain, Harlequin out-clowned Pierrot. As for Pulcinella, although he had appeared, he could not out-clown Harlequin. Furthermore Pulcinella grew into Punch (Punchinella) and, as mentioned above, he migrated to the land of puppetry. But above all, British harlequinades were hilarious: genuine slapstick. Moreover they were pantomimic as would be Jean-Gaspard Debureau‘s (Battiste) as well as Jean-Louis Barrault‘s (Baptiste). Baptiste is nimble and precise, but in England, the chaotic “chase” had begun. The last harlequinade was played in 1939.

The Ballets Russes, Stravinsky, Picasso

Sergei Diaghilev‘s enormously successful Ballets Russes were inspired by the commedia dell’arte. Diaghilev commissioned a ballet version of Pulcinella, composed by Igor Stravinsky and choreographed by Russian-born Léonide Massine. Furthermore, Pablo Picasso, who had already painted characters from the Commedia dell’arte, Harlequin in particular, designed the original costumes and sets for the ballet (1920).

Harlequin and other members of the Commedia are associated with Pierre de Marivaux (4 February 1688 – 12 February 1763). Marivaux wrote many plays for the Comédie-Française and the Comédie-Italienne. But we are skipping Marivaux’s polished Arlequin because the discussion would be too long and too complex. We will instead look at images, Picasso’s in particular, and provide the names of innamorati, lazzi and zanni, but that will be my last post on the Commedia dell’ arte itself.

My best regards to all of you.

Colombine

Arlequin poli par l’amour, Marivaux

RELATED ARTICLES

Leo Rauth’s “fin de siècle” Pierrot (27 June 2014)

Pantalone: la Commedia dell’arte (20 June 2014)

Sources and Resources

Commedia dell’arte (shane-arts)

Development of Pantomime (The)

Harlequin everywhere you look (thoughtsontheatre)

Masques et bouffons (comédie italienne), 1860. (See Maurice Sand, in Wikipedia.) Maurice Sand’s book is available online at Masques et bouffons (comédie italienne)

Marivaux’s Arlequin poli par l’amour (EN)

____________________

[i] “Arlecchino,” Phyliss Hartnoll, ed. The Oxford Companion to the Theatre, 3rd edition (Oxford University Press, 1967 [1951])

[ii] “John Rich”. Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., 2014. Web. 28 Jun. 2014 <http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/502381/John-Rich>.

[iii] Oxford English Dictionary

[iv] Early Pantomime (Victoria and Albert Museum, London)

[v] The “batte,” Harlequin’s stick, became a magic wand used by a fairy to effect a change of scenery or transform the characters. It is called “trickwork.”

“commedia erudita”. Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., 2014. Web. 29 Jun. 2014 <http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/127767/commedia-erudita>.

“Compagnia dei Gelosi”. Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., 2014. Web. 28 Jun. 2014 <http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/228004/Compagni-de-Gelosi>

“Harlequin”. Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., 2014. Web. 28 Jun. 2014 <http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/255421/Harlequin>.

“Passion play”. Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., 2014. Web. 28 Jun. 2014 <http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/445807/Compagnie-Passion-Play>

Seated Fat Clown, by Pablo Picasso, 1905

Arlequin et Colombine

© Micheline Walker

June 30, 2014

WordPress

Arlecchino, Arlequin, Harlequin Origins Atellana comedy Plautus Passion Plays Arlecchino, as we know him, is a stock character dating back to seventeenth-century

#British harlequinades#I Gelosi#John Rich#pantomime#Passion Plays#Pulcinella#Punch and Judy#slapstick comedy#Tristano Martinelli#zanni

0 notes

Text

YALL SEEN THE NEWEST EPISODE OF CAFAE LATTE????

THE JOHN X HERLA SLOWBURN IS GOING OMFG (I GUESS MILD SPOILERS UNDER THE CUT??)

HERLAS GONNA SAVE JOHN FROM A MURDERER (OR AT LEAST HE FUCKIN BETTER DUDE I WILL CRY IF JOHN DIES I LOVE HIM SM) AND THIS EXPERIENCE IS GONNA HAVETA MOVE THEIR RELATIONSHIP ALONG A BIT YKNOW YKNOW YKNOW

UGGGHHHH THIS FUCKIN SERIES MAKES ME SICK VRO/POS

hhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhh I wanna draw smth ab it, will prolly do so over the weekend fire emoji

87 notes

·

View notes

Text

Geiler von Kaiserberg and the Furious Army by Claude Lecouteux

Und es war die Zeit des Vollmonds In der Nacht vor Sankt Johannis Wo der Spuk der Wilden Jagd Umzieht durch den Geisterhohlweg [And it was the time of the full moon, In the night before Saint John’s, When the apparition of the Wild Hunt Moved through the haunted hollow.] —Heinrich Heine, Atta Troll, XVIII

For more than two thousand years, legends have been circulating that tell of the passage of a troop of the dead, either by land or through the air, on certain dates of the year.(1) Depending on the form of the narratives, the country, or region, this phenomenon has been referred to as the Wütendes Heer [Furious Army], the Mesnie Hellequin [Retinue of Hellequin], or the Chasse Artus [Arthur’s Hunt], among others. For more than a century, scholars and researchers—following the lead of Jacob Grimm and Elard Hugo Meyer—have asserted that Wotan/Odin was the leader of this dead host, but Lutz Röhrich, bringing clarity to the matter, quite rightly notes that “In no instance is the equivalence of Wode [the Low German name of the wild huntsman]—and Wotan certain.”(2 )Leander Petzoldt correctly distinguishes between the Wild Hunt and the Cursed Huntsman in his Dictionary of Demons and Elementary Spirits.(3 )The confusion between the two legends is based on a body of beliefs maintaining that the dead can come back, which has then been coupled with a Christian interpretation of the facts: these dead are sinners who are going through purgatory as members of this host, or they are, quite simply, the damned. These beliefs took the form of legends that cross-contaminated one another to form, at the turn of the fifteenth to sixteenth century, a complex web whose various threads can be delineated as follows:

1. The belief in nocturnal hosts led by Diana, Hecate, or Herodias, and the belief in revenants. 2. The belief that the spiritus, or psyche, remained near the body for thirty days immediately following death. 3. The belief that death only entailed an exile to the grave or to another world, during which time the deceased person retained all faculties, kept watch over the activities of friends and family, and intervened in human affairs, either in corpore or in spiritu (as is the case with dreams).(4 )

This type of belief concerning death, which went hand in hand with ancestor worship and specific funerary rites, was too deeply anchored in people’s minds to disappear when they were converted to Christianity. The Church had to make do with it and divert these beliefs for its own benefit. As a result, a compound legend arose that concerned the damned who wander the earth on certain dates,(5) and the notion of impiety punished (which is the source of numerous legends, including those of the Cursed Huntsman and of the Man in the Moon).

The two variants of pagan folklore that had been Christianized continued to influence each other and, because they provided an open narrative structure, receptively incorporated motifs from other legends relating to death and to the beyond (for example, the legends of Mount Venus and of “Loyal Eckhart”). The Christian texts are starkly didactic and deliver a clear message: there is no prayer of posthumous salvation for those who have not respected the commandments of God and his Church. They fall into the category of “pedagogy through fear,” similarly to the literature of revelations (incidentally, the last example of the latter genre, and a humorous one at that, is Alphonse Daudet’s Le Curé de Curcugnan).

In order to rediscover the primary meaning of the Furious Army (I will use this name here to avoid any confusion), a distinction must be drawn between the original content of the legend and the later accretions. For example, we must avoid blending— as was so often the case until now(6) —this theme with that of the Cursed Huntsman who succumbed to his passion for hunting on a day sacred to the Lord, or who unwittingly swore an oath committing him to this activity for eternity. If I must venture a simple definition of the Furious Army, I would say that it was originally a group of revenants which had the right to leave the Other World for a limited time, as was the case with the ancient Greek festival of Anthesteria (February 11–13). The last day of this festival (chytroi) was dedicated to propitiating the dead and their leader, Hermes Chthonios. In ancient Rome, the festival of Lemuria on May 9, 11, and 13 was an occasion for the dead to burst into homes.

We can refine this definition in accordance with its historical evolution. While in the Greek festival all the dead were involved, in Rome the revenants were recruited exclusively from the ranks of those who had died prematurely—including suicides and the victims of violent death—and those who had not received a ritual burial.(7) In the Middle Ages, the members of the Furious Army were sinners first and foremost. In contrast with the “normal” dead who appeared during Anthesteria or Lemuria, medieval revenants could surge out on any date, but this occurred individually and not as a group. I believe that a shift between the regular dead and revenants took place here, with the latter collected together to form a troop, perhaps under the influence of other beliefs, traces of which can be found in the Germano-Scandinavian world. Here, the dead who are unhappy with their fate and are moved by feelings of vengeance gather together under the leadership of the first to die. This can mainly be seen with occurrences relating to epidemics, as we find in the Eyrbyggja Saga.

In short, whether in Greece, Rome, or the Germanic countries, we encounter the essential elements of something that can be condensed into a narrative of purportedly true events. The first detectable amalgam is that of the immaturi (aori, biothanati) with the common dead leaving the Other World in February or May. Here, the Church first adopted characteristic elements from this narrative—it retained the notion of the troop, essentially a nocturnal host—but made the members of this troop into the damned or the inhabitants of Purgatory.(8) If they made an appearance, it was to reveal their torment and beseech the living for suffrages so that they might find redemption and be freed. In his Liber visionum,(9) written between 1060 and 1067, Otloh of Saint- Emmeram reported what he called a memorable exemplum: two brothers spied a large host in the sky; evoking protection with the sign of the cross, they requested that these people tell who they were. One of them, their father, informed them of the sin for which he was being punished.(10) He had stolen the property of a monastery and would only be redeemed when that property had been returned. In Orderic Vitalis’s work (11) (circa 1092), a certain Robert, son of Ralph the Fair-Haired, told the priest Gauchelin (or Walchelin): “In addition, I have been allowed to appear to you and show you how wretched I am” (Mihi quoque permissum est tibi apparere, meumque miserum esse tibi manifestare). He owed his torment “to his sins” (pro pecatis) but had “hopes for deliverance” (anno relaxationem ab hoc onere fiducialiter exspecto). Another one of the dead had a similar desire—“Exactly a year after Palm Sunday I hope I will be saved” (a Pascha florum usque ad unum annum spero salvari)—and added that Gauchelin should also seek atonement: “You should truly worry about yourself, and correct your life wisely” (Tu vero sollicitus esto de te, vitamque tuam prudenter corrige). Ekkehard, the Abbot of Aura, reported that a member of the Furious Army who appeared near Worms in 1123 said: “We are not ghosts (phantasmata) . . . but the souls of recently slain knights (animae militun non longe antehac interfectorum).”(12) The arms they bore were responsible for making them sin (instrumenta peccandi) and are therefore a torture for them (material tormenti). The chronicler adds that Count Emicho (died 1117) was said to have appeared with such a troop and declared that he would be delivered from his torments by prayers and alms (ab hac pena orationibus et elemosinus se posse redimi docuisse).

Starting at the onset of the eleventh century, several types of tales coexisted with the sort attested by Orderic Vitalis and Ekkehard. These include: the legend of King Herla; legends of demoniacal hunters (whose appearance is confirmed by the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle for the year 1127 (13) and by The Chronicle of Hugh Candidus for the same date (14); legends of friends who have sworn a mutual oath that if one dies, he will return and tell the surviving friend about the fate he has experienced after his death (this is the theme of the Reuner Relation (15) written between 1185 and 1200, as well as of a passage by Hélinand de Froidmont [1150–1221/29]); and legends of armies that continue waging their battles after death.(16)

An important motif emerges from the Christian legends: one of the members of the Furious Army speaks up to explain his fate. In the Reuner Relation, the dead individual appears on a mountain where his still-living friend had arranged their meeting. The friend “heard the mingled voices of a throng like a host hastening to some siege. Shortly he saw a large multitude which appeared to be riding and they were all armed” (audit cuiusdam multitudinis voces confuses quasi exercitus ad aliquam obsidionem festinantes. Videt post modicum quasi equitum grandem multitudinem et hii omnes armigeri). Two hosts emerge, followed by a third made up of the principes et rectores tenebrarum (princes and leaders of darkness). But the motif of the “revealer” broke away from the theme of the Furious Army. In the work by Pierre le Chantre (died 1197), master Silo (Siger of Brabant) beseeches one of his students to come visit him after his death to relate the situation in which he found himself; soon afterward, the other appeared and shared news of his torment.(17) Hélinand de Froidmont provides a good glimpse of how the legendary traditions spread their influence. In the eleventh chapter of De cognitione sui, transmitted by Vincent de Beauvais in the Speculum historiale XXIX, 118, he records the story that Henri of Orleans, Bishop of Beauvais, heard from the mouth of the canon, Jean. The first part of this chapter is similar to the Relation de Reun and can most likely be traced back to the same source: the two friends swear that the first to die will come visit the other within thirty days, if he is able (intra XXX dies, si posset, ad socium suum rediret). In his conversation with the deceased Natalis (Noel), the living friend, Burchard, asks, “But I beseech that you would tell me if you are deputies in that army called the Hellequins?” Natalis responds “No,” because the phenomenon stopped once his period of penitence was over. This indicates that the militia Hellequini is a wandering Purgatory.(18)

This long preamble is necessary if we truly wish to grasp what Geiler von Kaiserberg (1445–1510) recorded at the beginning of the sixteenth century. Born in Schaffhausen, Geiler left behind a significant body of work: speeches, translations of Jean Gerson’s sermons, and most importantly Das buoch von der Omeissen (known as the Emeis), a collection of sermons published in 1515 by the Strasbourg printer Johann Grüniger and republished in 1517. In 1856, August Ströber, well known for his interest in Alsatian legend, extracted everything from these sermons relating to folk belief that was condemned as superstitions, believing this comprised a good description of persistent mental attitudes that were closer to paganism than Christianity.(19 )The very long full title of the Emeis further points in this direction: Gibt vnderweisung von den Vnholden oder Hexen vnd von gespenst der geist vnd von dem Wütenden heer wunderbarlich vnd nützlich ze wissen was man davon glauben vnd halten soll. . . (Provides education about the Demons or Witches and about spirit ghosts and the Furious Army, wondrously and usefully for knowing what is believed of them and how one should deal with them. . .).

We will examine here what Geiler said of the Furious Army, which will allow us to raise the question of the transmission of so-called folk beliefs, with the understanding that a belief is never set in stone, but rather evolves over time.

In 1508, Geiler gave a sermon on the Thursday following Reminiscere (the second Sunday of Lent), in which he stated: “You ask, ‘What shall you tell us about the Wild Army?’ But I cannot tell you very much, as you know much more of it than I.” Such a formula is a standard classic in preaching and can often be found coming out of the mouth of Bertold of Regensburg: (20) the preacher sets himself apart from his audience, emphasizing the gap that separates him from the unfounded beliefs that smack of paganism. In a nutshell, he announces that what he is about to say is merely an echo of widespread rumors, but we shall see what kind of credence we can give him. Geiler immediately adds, “This is what the common man says: Those who die before the time God has fixed for them, those who leave on a journey and are stabbed, hung, or drowned, must wander after death until the date that God has set for them arrives. Then God will do for them what is in accordance with His divine will.” This belief is extremely old and can be seen in ancient Rome where premature deaths produced revenants. It made its way into the Medieval West by way of Tertullian (De anima 56): “Those souls which are taken away by a premature death wander about hither and thither until they have completed the residue of the years which they would have lived through, had it not been for their untimely fate” (Aiunt et immature morte praeventas eo usque vagori istic donec reliquatio compleatur aetatum quacum pervixissent, si non intempestive obissent).

It would take too long to follow its meandering course through the ages, so we satisfy ourselves with the testimony of William of Auvergne, whose De universo was written between 1231 and 1236. William knew of the existence of the Mesnie Hellequin (De Universo III, 12), which had been brought out of the shadows by Orderic Vitalis at the end of the eleventh century and enjoyed a much larger impact than what is claimed by Jean- Claude Schmitt, who, ignoring many accounts, has a tendency to restrict the legend to Normandy. William says (III, 14):

On the point that these [knights] appear in the shape of men, I say: of dead men, and those most often slain by iron, we can undoubtedly, based on the advice of Plato, consider that the souls of men thus slain continue to be active the number of days or the entire time it was given them to living in their bodies, if they had not been expelled by force. (De hoc autem, quod in similitudine hominum apparent, hominum dico mortuorum et maximo gladio interfectorum, videatur forsitan alicui iuxta sententiam Platonis, quod agere viderentur numeros dierum vel temporum debitorum animae mortuorum huiusmodi, temporum dico, quibus in corporibus victurae erant, eas nisi mortis huiusmodi violentia expulisset.) (21)

There is nothing “folkloric” about this notion because the men of this time had other explanations, a glimpse of which is provided above. Geiler goes on to say that the Furious Army made its appearance during the Ember Days and especially at Christmas, which is entirely in keeping with the beliefs of the time. Christmas, and more specifically the Twelve Days (Rauhnächte), is a period when the Other World is open, which is to say that a free passageway has been established between the realm of the dead and that of the living. Geiler next states: “And each proceeds in the dress of their status: a peasant in peasant garb, a knight as a knight, and they race therefore bound to the same rope. One is holding a cross in front of him, the other a head in his hand.” Here our preacher follows Hélinand de Froidmont or Vincent de Beauvais, in any case a written source from clerical literature. In Vincent de Beauvais’s book (Speculum historiale, XXIX, 118), which borrows a passage from Hélinand’s De cognitione sui, we read:

But this false opinion … that souls of the deceased, lamenting punishments of their sins, are in the habit of appearing to the masses in the style of dress in which they had formerly lived: that is to say, country folk in rustic clothing, soldiers in military dress, just as the masses are wont to claim about the family of Hellequin. (Haec autem falsitas opinio . . . quod animae defunctorum suorum peccatorum poenas lugentes multis apparere solent in eo habitu, in quo prius vixerant: id est rustici in rusticano, milites in militari, sicut vulgus asserere solet de familia Hellequini. . .)

Here again, the blending of popular and scholarly assumptions is clearly apparent. Ancient Scandinavian literature, which is our best witness of things relating to revenants, indicates on numerous occasions that the dead return in the same appearance as they had at the time of their death. (22) In Germany, the testimonies are much rarer (which in no way means that this vision did not exist), but fraught with significance. In a charm from the fourteenth or fifteenth century, the speaker requests God’s protection from:

Wutanes her und alle sine man, Dy di reder und dy wit tragen, Geradebrech und irhangin. . .(23 ) [the Furious Host and all its men, who carry wheels and fetters, broken apart and hung]

The members of the Furious Army appear here bearing the instruments of their torment. The Zimmern Chronicle describes one of the members of this procession in this fashion: “His head had been split in two down to the neck” (Dem ist das haupt in zwai thail biß an hals gespalten gewesen).”(24 )

The only motif yet to be explained by scholars is the rope mentioned by Geiler. This could be a recollection from Lucian of Samosata (Discourses, Hercules 1–7), who depicts the god Ogmios, an infernal psychopomp, pulling along “a large number of men attached by the ears with bonds of tiny gold and amber chains that resembled beautiful necklaces.” It so happens that in Albrecht Durer’s Kunstbuch of 1514, he depicted the allegory of eloquence as the god Hermes pulled humans by chains that connected his tongue to the ears of his captives.25 I offer the hypothesis for what it’s worth, but these parallels merit pointing out.

"One came before the rest,” added Geiler, shouting: “‘Get out of the road so that God may spare your life!’ This is what the common man says.” This new motif of the figure sounding the alarm comes directly from Orderic Vitalis’s narrative in which the priest Gauchelin saw the Mesnie Hellequin. Here, a giant man holding a club broke from the host and approached him saying: “Stay where you are. Do not move!” (Sta, nec progrediarius ultra). The figure delivering a warning quickly became quite popular; Jacob Trausch (died 1610), the author of the Strasbourg Chronicle, borrowed this figure and had him shout: “Get back, back, so that nothing happens to anyone!”26 In this instance, however, the legend is re-contextualized into the polemic between Catholics and reformers: such deceptions and superstitions have ceased ever since Dr. Martin Luther attacked Papism. The motif can also be found in the work of Johannes Agricola, this time with the addition of a novel element: the warning figure is named the Loyal Eckhard (der treüwe Eckart).(27) This latter example attests to the contamination of the Furious Army by the Venusberg legend (Tannhäuser).(28)

To illustrate his point, Geiler did as all good preachers do: he repeated a story—an exemplum or historiola. In this case, he borrowed it from Hélinand de Froidmont, undoubtedly by way of the Speculum historiale by Vincent de Beauvais. His text follows the source so closely it could be called a literal translation, as the end of the story shall prove.

[Geiler:] Bist du auch in dem wütischen her gelaufen, von dem man sagt? Er sprach: Nein, Karolus Quintus hat sein penitens erfült, un hat daz wütisch heer vff gehört. (“Are you also proceeding in the Furious Army that men talk about?” He spoke: “No, Karolus Quintus has fulfilled his penitence and has ended the Furious Army.”) [Hélinand:] sed obsecro ut dicatis mihi, si vos estis deputati in illa militia quam dicunt Hellequini. Et ille: Non, domine. Illa militia jam non vadit, sed nuper ire desiit, quia poenitentiam suam peregit. (“But I beg that you would tell me if you are deputies in that army they call the Hellequins?” “No, sir. That army does not advance now, but recently ceased marching because it fulfilled its penitence.”)

The sole modification—Karolus Quintus for militia Hellequinus— stems from the fact that Geiler was using a gloss by Vincent or Hélinand, which stated: “Corruptly, however, ‘Hellequinus’ is said by the common people instead of ‘Karlequintus’” (“Corrupte autem dictus est a vulgo Hellequinus pro Karlequintus”).

In light of the preceding information, it is easy to see how clerics worked and, more importantly, the omnipresence of the scholarly and bookish tradition. Thus, when a belief or legend is encountered in the religious texts of the late Middle Ages, it is necessary to be very prudent before asserting that the author was faithfully echoing reality. The sole reality is that men believed the dead returned on certain dates. Recontextualized by the Church, the belief was incorporated into the great cycle of the punishment of sin.

What is the case with the other folk traditions recorded by Geiler? Comparative analysis allows us to see that the preacher always worked in the same way: he took a “superstition,” then reduced and destroyed it with the help of the clerical literature. But did the object of his efforts correspond to a local reality? In the case of the werewolf,29 this is subject to doubt. In the case of witchcraft, the answer can be in the affirmative if we recognize that the Church contributed greatly to forging the belief—but we can only confirm the latter and not take the descriptions at face value. Researchers have indeed provided evidence that the catalogs of beliefs were accumulated bit by bit over time and that they were recapitulations of everything lurking in the writs of councils and synods, in the penitentials, and in the treatises on the Decalogue.(30) This was how the various Mirrors of Sin were born, such as the one by Martin von Amberg,(31) as well as the great fifteenth-century collections of “superstitions.” Narrative literature followed this same evolution, as is evident from the works of Michel Behaim (32) and Hans Vintler.(33) On the other hand, all these texts document the enduring nature of beliefs and practices—an enduring nature encouraged by the preachers who never stopped talking about them and therefore giving credence to those things they took to be errors, sins, and idolatry. The exempla with which they embellished their sermons then came into the public domain and gave birth to new narrative traditions. When Geiler speaks of a haunted house in the Mainz bishopric, in his sermon “Am mitwoch nach Occuli,” his inspiration is The Golden Legend of Jacobus de Voragine,34 and when he mentions “the wax that runs from the manes of horses,” he is following a passage from William of Auvergne’s De Universo. In order to establish the difference between local traditions and scholarly traditions, it is necessary to work diachronically, which is the only means for avoiding errors.

(Translated by Jon Graham)

This article originally appeared in French in the journal Études Germaniques 50 (1995): 367–76. The translation here is published by kind permission of the author.

1. Hans Plischke, Die Sage vom Wilden Heer im deutschen Volk, Dissertation, Leipzig, 1914; Alfred Endter, Die Sage vom Wilden Jäger und von der Wilden Jagd, Dissertation, Frankfurt, 1933; Michael John Petry, Herne the Hunter, a Berkshire Legend (Reading: William Smith, 1972).

2. “Nicht einmal gesichert ist die Gleichung Wode–Wotan.” Lütz Röhrich, Sage, 2nd ed. (Stuttgart: Metzler, 1971), 24.

3. Leander Petzoldt, Kleines Lexikon der Dämonen und Elementargeister (Munich: Beck 1990), 186–90.

4. Cf. Claude Lecouteux, Geschichte der Gespenster und Wiedergänger im Mittelalter (Cologne and Vienna: Böhlau, 1987); Claude Lecouteux and Phillipe Marcq, Les Esprits et les Morts, Croyances médiévales (Paris: Honore Champion, 1990).

5. During the Ember Days, Christmas, the three final Thursdays of Advent, Saint Sylvester’s Day, Saint John’s Day, Saint Martin’s Day, Saint Walpurgis’s Day, Saint Peter’s Day, Pentecost, etc.

6. Cf., for example, Gustav Neckel, Sagen aus dem germanischen Altertum (Leipzig: Philip Reclam, 1935), 21–56. 4 Claude Lecouteux

7. Cf. Claude Lecouteux, Fantômes et Revenants au Moyen Âge (Paris: Imago 1986), translated into English as The Return of the Dead (Rochester, VT: Inner Traditions, 2009); and Lecouteux, “Fantômes et Revenants,” in Denis Menjot and Benoît Cursente, eds., Démons et Merveilles au Moyen Âge (Nice: Université de Nice-Sophia Antipolis, 1990), 267–82.

8. Jacques Le Goff, La naissance du purgatoire, Paris, Gallimard, 1981.

9. Paul Gerhard Schmidt, ed., Liber visionum, MGH: Quellen zur Geschichte des Mittelalters 13 (Weimar: Böhlau, 1989), 67ff. Geiler von Kaiserberg and the Furious Army

10. Jean-Claude Schmitt, Les Revenants, les Vivants et les Morts dans la Société médiévales (Paris: Gallimard, 1994), makes a mistake and reverses the meaning in the text (p. 63) when he says a “knight came out of the this troop and asked them on the part of their father…” The text says: Ego pater vester rogo. . . .

11. Orderic Vitalis, Historia ecclesiastica, ed. Auguste Le Prévost, (Paris: J. Renouard, 1838–1855), vol. III, 367–77.

12. Franz Josef Schmale and Irene Schmale-Ott, eds., Frutolfs und Ekkehards Chroniken und die anonyme Kaiesrchronik (Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, 1972), 362. 6 Claude Lecouteux

13. Charles Plummer, ed., Two of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles Parallel (Oxford: Clarendon, 1892), vol. I, 258.

14. W. T. Mellows, ed., The Chronicle of Hugh Candidus (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1949), 76ff.

15. Hans Gröchenig, Die Vorauer Novelle und die Reuner Relation (Göppingen: Kümmerle, 1981), 29ff.

16. Vincent de Beauvais, Speculum historiale, XXX, 200, (Douai, 1624), 1225ff. 17. Jacobus de Voragine, Légende dorée [The Golden Legend], trans. J. B. M. Roze, (Paris: Garnier- Flammarion, 1967), vol. II, 326.Geiler von Kaiserberg and the Furious Army

18. Phillipe Walter, Mythologie chrétienne (Paris: Imago 1992), cf. index 285. Translated into English as Christianity: The Origins of a Pagan Religion (Rochester, VT: Inner Traditions, 2006).

19. Cf. August Stöber, Die Sagen des Elsasses (St. Gallen: Scheitlin and Zellikofer, 1852) and August Stöber, Zur Geschichte des Volksaberglaubens im Anfange des XVI. Jahrhunderts. Aus Dr. Joh. Geilers von Kaisersberg Emeis (Basel: Schweighauser, 1856). The text can also be found in Karl Meisen, Die Sagen vom Wütenden Heer und Wilden Jäger (Münster i.W.: Aschendorf, 1935), 96ff.8 Claude Lecouteux

20. Cf. Claude Lecouteux and Phillippe Marcq, Berthold de Ratisbonne, Péchés et Vertus. Scènes de la Vie au XIIIe siècle (Paris: Desjonquères, 1991). Geiler von Kaiserberg and the Furious Army

21. William of Auvergne, Opera Omnia (Paris, 1674), vol. I, 1074. 10 Claude Lecouteux

22. Claude Lecouteux, “Fantômes et Revenants germaniques, Essai de Présentation,” Études Germaniques 39 (1984): 227–50; 40 (1985): 141–60; and Lecouteux, “Altgermanische Gespenster und Wiedergänger: Bemerkungen zu einem vernachlässigten Forschungsfeld der Altgermanistik,” Euphorion 80 (1986): 219–31.

23. Johannes Franck, “Geschichte des Wortes Hexe,” in Joseph Hansen, Quellen und Untersuchungen zur Geschichte des Hexenwahns (Hildesheim: Olms, 1963), 614–70, here at 639ff.Geiler von Kaiserberg and the Furious Army 11

24. Karl August Barack, ed., Das Zimmersche Chronik, 2nd. ed. (Freiburg and Tübingen: Mohr, 1881–1882), vol. IV, 122–27.

25. Cf. Friedrich Winkler, Die Zeichnungen Albrechts Dürers, vol. III, 79. This matter is discussed, with a bibliography, in Françoise Le Roux, “Le Dieu celtique aux Liens,” Ogam XII (1960): 212–18.

26. The reader may also refer to Johannes Geffken, Der Bildercatechismus des fünfzehnten Jahrhunderts und die catechetischen Hauptstücke in dieser Zeit bis auf Luther. I: Die Zehn Gebote (Leipzig: T. O. Weigel, 1855), 37ff.12 Claude Lecouteux

27. Text in Karl Meisen, Die Sagen vom Wütenden Heer, 98ff. It will be noted that this individual has become a figure of legend; cf. Lütz Röhrich, Das große Lexikon der sprichwörtlichen Redensarten (Freiburg im Bresgau, Basel, and Vienna: Herder, 1991–1992), vol. I, 350ff.

28. Cf. J. M. Clifton-Everest, The Tragedy of Knighthood: The Origin of the Tannhäuser-Legend (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1979). Geiler von Kaiserberg and the Furious Army 13

29. Cf. August Stöber: Zur Geschichte des Volksaberglaubens, 31 (“werewolf”); 11ff.; 12; 17ff., 33ff. (“witch”). Regarding the werewolf, however, Geiler was inspired by Vincent de Beauvais, Valère Maxime, and William of Auvergne.

30. Cf. the fine studies in Marianne Rumpf, Perchten: Populäre Glaubensgestalten zwischen Mythos und Katechese (Würzburg: Königshausen & Neumann, 1991) and Karin Baumann, Aberglaube für Laien. Zur Programmatik und Überlieferung mittelalterlicher Superstitionenkritik (Würzburg: Königshausen & Neumann, 1989).

31. Stanley N. Werbow, ed., Martin von Amberg. Der Gewissensspiegel (Berlin: Schmidt, 1958). 14 Claude Lecouteux

32. Cf. Ernst-Dietrich Güting, “Michel Behaims Gedicht gegen den Aberglauben und seine lateinische Vorlage. Zur Tradierung des Volksglaubens im Spätmittelalters,” in Dietz-Rüdiger Moser, ed., Glaube im Abseits (Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgellschaft, 1992), 310–67.

33. Cf. Max Bartels and Oskar Ebermann: “Zur Aberglaubensliste in Vintlers Pluemen der tugent,” Zeitschrift des Vereins für Volkskunde 23 (1913): 1–18; 113–36. Cf. also the article by Anton E. Schönbach, “Zeugnisse zur deutschen Volkskunde des Mittelalters,” Zeitschrift des Vereins für Volkskunde 12 (1902): 1–16. On the list of superstitions in the work of Thomas de Haselbach, see Franz-Josef Schweitzer, Tugend und Laster in illustrierten didaktischen Dichtungen des Spätmittelalters (Hildesheim: Olms, 1993), 180–84.

34. Who drew his material from the Chronicle of Sigebert de Gembloux for the year 858, cf. J. C. Migne, ed., Patrologia Latina 160, col. 163. This information can also be found in Vincent de Beauvais (Speculum historiale XXIV, 37) and in the works of many other authors.

0 notes

Note

I neeeeed your opinions on Cyrus/Rethu, Nicole/JC and, Herla/John

AHHHHH to all/pos

Nicole and JC? Perfect, the blueprint, the ogs, supporting each other, holding each other accountable and being PERFECT

Cyrus and Rethu, also love them, need more of them, but I'm also a giant Cyrus stan sooooooo, but yes, the two book nerds, the besties that turned romantic, we stan healthy relationships in his household

Herla and John, I do love them. I defiantly would like some more development before and if they become official, Herla clearyyyy has some trauma to work out and they would need some kinda boundaries because Herla worries about John when John does his job and it seems the same vice versa so they need a way to handle that without demanding them to give up work

6 notes

·

View notes