#joaquim | court times

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

@joaquimxmarques | Setting: Hidden away Sports Place | Local Time: 17:34

Easton throws the ball, and he misses the net by a meter. "God, it's been years and I still haven't gotten better." The man is wearing a black hoodie, hood pulled up, morphing into the darkness - his attempt of not being caught by fans or press and having a normal moment out with a friend, but being seen with Joaquim wouldn't be an issue, anyway. While it's hard to imagine he would ever suck at some kind of sport, as buff and tall as he is, he has gotten maybe two or three balls in, in the span of a good twenty minutes.

Asking Joaquim questions about what he's been up to is an attempt to distract him, but he's also curious. "So," he starts, picking up the basketball and throwing it to him as it's his turn to attack, "What's up? How's your sister and your niece?"

6 notes

·

View notes

Note

13. for an argumentative starter (For Jum & Joaquim)

"you are ruling beside me--!" joaquim roars, fist cracking the table they're currently sat at. mealtimes were supposed to be nice. in his kingdom, it is a warrior's time to celebrate and put down his armor. to enjoy their spoils and the bonds between those who share iron. mealtimes were sacred.

so why, pray tell, was he arguing with his new husband during one of their first dinners? everyone had ducked out for their own good: attendants suddenly finding something to do in the hallway or kitchen and its advisor suddenly wanting to go monitor the reef. joaquim's temper was as well known as it was feared, telltale signs causing quick and efficient dispersal of parties in the vicinity. all parties, that is, except for his pretty jum.

"you do not rule above me," he grits out, large hand gripping the table lest he lose further control. "this ain't your territory, angelfish. remember that. you're a guest." a sharp smile twists into his features and he tickles under the other's chin. "until you can prove yourself outside of my chambers, anyway."

#he's a pig <3#ask; joaquim#r3dblccd#hope its okay!!! i wanted to jump in this time but we can do courting in another thread if you want#v; the kingdom by the sea

1 note

·

View note

Text

"Cause looking for heaven, found the devil in me"

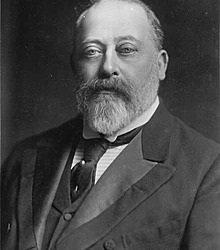

Emperor Angelo Tolentino | He/Him | 40 | China & The Philippines | FC: Charles Michael Davis

Basics:

NAME: Angelo Tolentino TITLE: Emperor of China and the Philippines AGE: 40 FACECLAIM: Charles Michael Davis SEXUALITY: Pansexual and Polyamorous MARITAL STATUS: Single POSITIVE TRAITS: Emphatic, Charismatic, Brave, Self-Assured NEGATIVE TRAITS: Disloyal, Dishonest, Competitive, Bitter HOBBIES: Sailing, Cooking

The Story (So Far): Abuse TW, Murder TW

Born to a second-born Princess from the Filipino Royal Family and a commander of the Filipino naval army, Angelo Tolentino is a Prince in his own right - no matter what his step-siblings (or all of China) wishes to believe. The union was not one of love, but necessity, and Angelo bore witness to the ramifications of bowing to duty above all else. The royal household was a violent one, riddled with screaming matches and his father's hands on his mother's person.

He was twelve when his governess approached him and his sibling with news - their father passed of unknown causes. Of course, one look beyond his governess' shoulder is all it takes to see the quiet satisfaction on his mother's face. Nothing is an accident. Not when it comes to family or power. It was his first purview to the filth one must endure to, well, endure - and to this day, Angelo is uncertain if its a dangerous lesson to learn at his young age.

It's not long before his mother marries once more. This time, to the most powerful nation in Asia - China and the Qing Dynasty. Their households join together, and though they are not blood, the Qing's are his siblings by law and by the Emperor's decree. It lacks in fondness, but hostility comes later - when the Emperor began to look beyond the heir and towards the lot of them.

After completing his studies, Angelo ventured out to sea as a commanding officer on one of the Qing's most formidable fleets. The taste of the broader world educates him in cultures, and lovers. The ghastly words of his mother in his ear; "your power is your charm. use it." And so he does, slowly securing his place in hearts and agendas throughout the broader world.

With news of the Emperor breaking from the line of succession, Angelo is determined to claim the throne as his own.

Opulent, Part 1: During his stay in the Mughal Empire, Angelo made quick work to cement himself as the only option to succeed the Emperor of China. And in true Angelo fashion, he made both key enemies (like the contingent of Japan) and salacious allies (such as the Sultana Arshiya and Prince Joaquim). But his penultimate move for the throne is poisoning the well between the Qing siblings. After revealing the Princess Kai-Ming's secrets and crafting it as treason, he effectively had her banished from Chinese court. A power move that would lead the Emperor to pick Angelo as his successor.

The Opulent, The Reckoning: After the Emperor of China passed during the Reckoning, Angelo quickly ascended the throne. Ambitious and perhaps fool-hardy, he fulfilled the longstanding threat of China's attempt to seize Japan as its own. Yet despite China's size and prowess, the war failed miserably. Now, China is held in low regard for their callous war... And more importantly, their inability to succeed. Beaten down but never to be counted out, Angelo arrives onto the scene to remind everyone; he is the future of a great dynasty.

SIMILAR CHARACTERS: Klaus Mikaelson (The Original), Loki (The Avengers), Littlefinger (Game of Thrones),

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

@proficios ( gisela & magdalene ) Location: The German Apartments, the sitting room Time: Just after the rainstorms

Five days. All that time to recover, her burdens pouring out equally as persistently as the sky's tears that fell from the clouds. Once the rain subsided, it seemed, so did the queen. Though a bit of anger remained beneath the surface over her sister-in-law's betrayal, just when things were beginning to be on the mend, she would swallow that down for a brief moment before tea time. Only when the tea would spill, so would she. Magdalene was a dear friend from her childhood, before Eleanor. Perhaps that was why it felt so good to invite her. "I'm only sorry that I did not invite you to tea sooner, but nothing else apart from that," she winked as she broke from her old friend's embrace and gestured her to sit by the pot of tea that sat on a small table... seemingly, all they could afford, "So a seat in Spanish court, hmm? That seems rather exciting, also advantageous if I'm to somehow maintain this betrothal between Stefan and Joaquim."

0 notes

Text

June 2023 Media Breakdown

Movies:

Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse (2023) - Joaquim Dos Santos, Kemp Powers, & Justin K. Thompson

Shinjuku Boys (1995) - Kim Longinotto & Jano Williams

Pete (2022) - Bret Parker

The Times of Harvey Milk (1984) - Rob Epstein

Vámanos (2015) - Marvin Lemus

TV Shows:

Shiny Happy People: Duggar Family Secrets - Season 1 (2023)

Justified - Season 1 (2010) & Season 2 (2011)

Books: Completed

The Drawing of the Three (1987) - Stephen King

The Waste Lands (1991) - Stephen King

Ringworld (1970) - Larry Niven

Six of Crows (2015) - Leigh Bardugo

Wizard and Glass (1997) - Stephen King

The Very Secret Society of Irregular Witches (2022) - Sangu Mandanna

The Ringworld Engineers (1979) - Larry Niven

I’m Glad My Mom Died (2022) - Jennette McCurdy

A Court of Wings and Ruin (2017) - Sarah J. Maas

Books: In Progress

The Ringworld Throne (1997) - Larry Niven | 26%

Ninth House (2019) - Leigh Bardugo | 3%

Artistic Pursuits 💅:

Still working on my scrap yarn blanket

Worked on going over the register on my clarinet

Saw the following artists at Bonnaroo:

Molly Tuttle & Golden Highway

Liquid Stranger

MUNA

Rina Sawayama

Charlie Crockett

Fleet Foxes

Sylvan Esso

Friko

Paris Paloma

The Band CAMINO

Remi Wolf

Sofi Tukker

Lil Nas X

Tyler Childers

ODEZA

Hippo Campus

Peach Pit

Girl in Red

Paramore

Foo Fighters

#june 2023#media breakdown#I did not watch very many movies this month lol#but in my defense#I was out of town for 15 out of the 30 days in June

0 notes

Text

DOMITILA OF CASTRO

Marchioness of Santos

(born 1797 - died 1867)

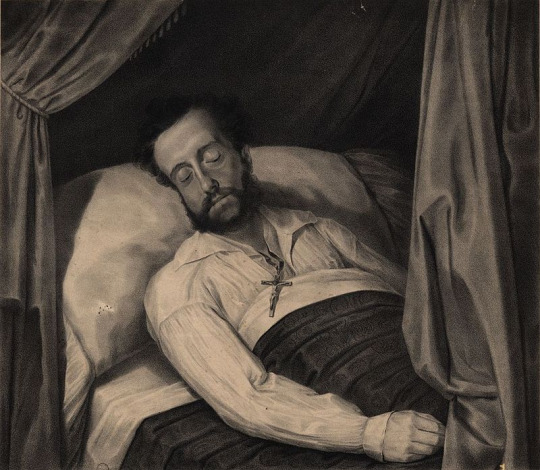

pictured above is a portrait of the Marchioness of Santos, by Francisco Pedro do Amaral from c. 1826

-------------------- ~ -------------------- ~ --------------------

SERIES - On this day November Edition: Domitila died on 3 November 1867.

-------------------- ~ -------------------- ~ --------------------

DOMITILA was born in 1797, at the city of São Paulo in the state colony of Brazil, part of the Portuguese Empire. Her full name was DOMITILA OF CASTRO CANTO AND MELO.

She was one of the daughters of João of Castro Canto and Melo (an Army officer born at the Azores archipelago in Portugal) and Escolástica Bonifácia of Oliveira Ribas Toledo, a Brazilian born.

-------------------- ~ -------------------- ~ --------------------

A brief History... of Brazil...

To give some context... I will alternate Domitila's History with the History of Brazil.

By 1808 the Portuguese Royal Family arrived in the state colony of Brazil, fleing from Napoléon I, Emperor of the French.

-------------------- ~ -------------------- ~ --------------------

Aged 15, in 1813, the young Domitila was married to FELÍCIO, an Army officer whose full name was Felício Pinto Coelho of Mendonça, and they had three children (check the list below). His parents were Felicio Moniz Pinto Coelho and Mariana Manuela Furtado Leite of Mendonça.

It was an abusive marriage and after giving birth to two children she tried to leave him, but she eventually reconciled with him and they had another child.

-------------------- ~ -------------------- ~ --------------------

Meanwhile in 1815, João, Prince Regent of Portugal elevated the state colony of Brazil to Kingdom of Brazil, acting in the name of his mother Maria I, Queen of Portugal.

But months later, already in 1816, the Queen died and the former Prince Regent of Portugal succeeded as João VI, King of Portugal and Brazil.

-------------------- ~ -------------------- ~ --------------------

As the abusive behaviour of Domitila's husband continued, after he made an attempt to her life she had no choice other than separate definitely from him and fight for her children's custody.

-------------------- ~ -------------------- ~ --------------------

From here, DOMITILA's History starts to intertwine with the early History of the Empire of Brazil...

In 1821 the Portuguese Royal Family left Brazil and returned to Portugal, leaving the King's son Dom PEDRO DE ALCÂNTARA FRANCISCO ANTÓNIO JOÃO CARLOS XAVIER DE PAULA MIGUEL RAFAEL JOAQUIM JOSÉ GONZAGA PASCOAL CIPRIANO SERAFIM as the Prince Regent of Brazil. And in 1822 Domitila met him and became his mistress.

Around the time she met the Prince Regent of Brazil, he declared the independence of Brazil from Portugal becoming PEDRO I, the first Emperor of Brazil.

Although the Emperor was married he was known for having many mistresses and Domitila was/is the most famous. They had at least five children (check the list below) together, of whom two girls survived into adulthood. And in 1825 he made her VISCOUNTESS OF SANTOS.

From March to May 1826 her lover was also PEDRO IV, the King of Portugal, until he abdicated. And by October 1826 he elevated her to MARCHIONESS OF SANTOS.

Her lover's wife Archduchess Maria Leopoldine of Austria died in November 1826 after a miscarriage, and the Brazilian people who loved their Empress blamed Domitila and her relationship with the Emperor.

So when her lover decided to remarry many Royal Families around Europe were reticent to give their daughters' hand in marriage to a foreign Monarch who had no respect for his late wife.

Finally by 1829 her lover found a match and was forced to end the relationship with Domitila. She left the Court in Rio de Janeiro and moved back to São Paulo, where she gave birth to their last children, who was raised by her.

After the Emperor of Brazil abdicated in 1831 and moved to Europe, Domitila's eldest daughter with him Isabel Maria de Alcântara Brasileira, Duchess of Goiás went with him to study there. She was the only surviving child of Domitila and the Emperor who was granted a title and as she left Brazil really young she only knew about her origins as an adult.

Soon after moving to São Paulo Domitila found a new lover RAFAEL, the President of the São Paulo Province whose full name was Rafael Tobias of Aguiar. His parents were Antônio Francisco of Aguiar and Gertrudes Eufrosina Aires. She had six children (check the list below) with him before their marriage in 1842, and they stayed together for 24 years until his death in 1857.

The Marchioness of Santos outlived her second husband by ten years, dying aged 69, on 3 November 1867, in her hometown.

-------------------- ~ -------------------- ~ --------------------

DOMITILA and her first husband FELÍCIO had three children...

Francisca Pinto Coelho of Mendonça and Castro - wife of José of Castro of Canto and Melo;

Felício Pinto Coelho of Mendonça and Castro - probably married; and

João Pinto Coelho of Mendonça and Castro - died around three months.

With her second husband RAFAEL she had six children...

Rafael Tobias of Aguiar and Castro - husband of Ana Cândida of Oliva Gomes;

João Tobias of Aguiar and Castro - husband of Ana Barros of Aguiar;

Gertrudes of Aguiar and Castro - died aged three;

Antônio Francisco of Aguiar and Castro - husband of Placidina Adélia of Brito;

Brasílico of Aguiar and Castro - husband of Júlia Augusta of Vasconcelos Tavares; and

Heitor of Aguiar and Castro - died around four years old.

And she also had illegitimate children...

With PEDRO I, Emperor of Brazil...

Isabel Maria of Alcântara, Duchess of Goiás - wife of Ernst, 2nd Count of Treuberg;

Pedro of Alcântara Brasileiro - died aged three months;

Maria Isabel of Alcântara Brasileira, Duchess of Ceará - died aged two months; and

Maria Isabel of Alcântara - wife of Pedro Caldeira Brant, Count of Iguaçu.

#domitila#domitila de castro#royal mistresses#dom pedro i#empire of brazil#brasil imperial#familia imperial brasileira#brazilian nobility#royals#royalty#monarchies#monarchy#royal history#brazilian history#latin american history#world history#history#history lover#braganza#house of braganza#peter i#emperor peter i#marchioness of santos#marquesa de santos#18th century#19th century#history by laura

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

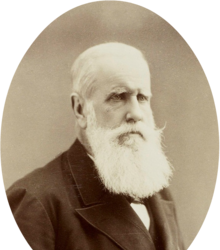

28th King of Portugal (8th of the Bragança Dynasty): King Pedro IV of Portugal, “The Liberator/The Soldier King”

Reign: 10 March 1826 – 2 May 1826 Predecessor: João VI

Pedro IV (12 October 1798 in Queluz, Portugal – 24 September 1834 in Queluz, Portugal), nicknamed "the Liberator", was the founder and first ruler of the Empire of Brazil. As King Dom Pedro IV, he reigned briefly over Portugal, where he also became known as "the Liberator" as well as "the Soldier King". Born in Lisbon, Pedro IV was the fourth child of King Dom João VI of Portugal and Queen Carlota Joaquina, and thus a member of the House of Bragança. When the country was invaded by French troops in 1807, he and his family fled to Portugal's largest and wealthiest colony, Brazil.

The outbreak of the Liberal Revolution of 1820 in Lisbon compelled Pedro IV's father to return to Portugal in April 1821, leaving him to rule Brazil as regent. He had to deal with threats from revolutionaries and insubordination by Portuguese troops, all of which he subdued. The Portuguese government's threat to revoke the political autonomy that Brazil had enjoyed since 1808 was met with widespread discontent in Brazil. Pedro IV chose the Brazilian side and declared Brazil's independence from Portugal on 7 September 1822. On 12 October, he was acclaimed Brazilian emperor and by March 1824 had defeated all armies loyal to Portugal. A few months later, Pedro IV crushed the short-lived Confederation of the Equator, a failed secession attempt by provincial rebels in Brazil's northeast.

A secessionist rebellion in the southern province of Cisplatina in early 1825, and the subsequent attempt by the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata to annex it, led the Empire into the Cisplatine War. In March 1826, Pedro IV briefly became king of Portugal before abdicating in favor of his eldest daughter, Dona Maria II. The situation worsened in 1828 when the war in the south resulted in Brazil's loss of Cisplatina. During the same year in Lisbon, Maria II's throne was usurped by Prince Dom Miguel, Pedro IV's younger brother. The Emperor's concurrent and scandalous sexual affair with a female courtier tarnished his reputation. Other difficulties arose in the Brazilian parliament, where a struggle over whether the government would be chosen by the monarch or by the legislature dominated political debates from 1826 to 1831. Unable to deal with problems in both Brazil and Portugal simultaneously, on 7 April 1831 Pedro IV abdicated in favor of his son Dom Pedro II, and sailed for Europe.

Pedro IV invaded Portugal at the head of an army in July 1832. Faced at first with what seemed a national civil war, he soon became involved in a wider conflict that enveloped the Iberian Peninsula in a struggle between proponents of liberalism and those seeking a return to absolutism. Pedro IV died of tuberculosis on 24 September 1834, just a few months after he and the liberals had emerged victorious. He was hailed by both contemporaries and posterity as a key figure who helped spread the liberal ideals that allowed Brazil and Portugal to move from absolutist regimes to representative forms of government.

Pedro was born at 08:00 on 12 October 1798 in the Queluz Royal Palace near Lisbon, Portugal. He was named after St. Pedro of Alcantara, and his full name was Pedro de Alcântara Francisco António João Carlos Xavier de Paula Miguel Rafael Joaquim José Gonzaga Pascoal Cipriano Serafim. He was referred to using the honorific "Dom" (Lord) from birth.

Through his father, Prince Dom João (later King Dom João VI), Pedro was a member of the House of Bragança and a grandson of King Dom Pedro III and Queen Dona (Lady) Maria I of Portugal, who were uncle and niece as well as husband and wife. His mother, Doña Carlota Joaquina, was the daughter of King Don Carlos IV of Spain. Pedro's parents had an unhappy marriage. Carlota Joaquina was an ambitious woman, who always sought to advance Spain's interests, even to the detriment of Portugal's. Reputedly unfaithful to her husband, she went as far as to plot his overthrow in league with dissatisfied Portuguese nobles.

As the second eldest son (though the fourth child), Pedro became his father's heir apparent and Prince of Beira upon the death of his elder brother Francisco António in 1801. Prince Dom João had been acting as regent on behalf of his mother, Queen Maria I, after she was declared incurably insane in 1792. By 1802, Pedro's parents were estranged; João lived in the Mafra National Palace and Carlota Joaquina in Ramalhão Palace.

Pedro and his siblings resided in the Queluz Palace with their grandmother Maria I, far from their parents, whom they saw only during state occasions at Queluz.

In late November 1807, when Pedro was nine, the royal family escaped from Portugal as an invading French army sent by Napoleon approached Lisbon. Pedro and his family arrived in Rio de Janeiro, capital of Brazil, then Portugal's largest and wealthiest colony, in March 1808. During the voyage, Pedro read Virgil's Aeneid and conversed with the ship's crew, picking up navigational skills. In Brazil, after a brief stay in the City Palace, Pedro settled with his younger brother Miguel and their father in the Palace of São Cristóvão (Saint Christopher). Although never on intimate terms with his father, Pedro loved him and resented the constant humiliation his father suffered at the hands of Carlota Joaquina due to her extramarital affairs. As an adult, Pedro would openly call his mother, for whom he held only feelings of contempt, a "bitch". The early experiences of betrayal, coldness and neglect had a great impact on the formation of Pedro's character.

A modicum of stability during his childhood was provided by his aia (governess), Maria Genoveva do Rêgo e Matos, whom he loved as a mother, and by his aio (supervisor) friar António de Arrábida, who became his mentor. Both were in charge of Pedro's upbringing and attempted to furnish him with a suitable education. His instruction encompassed a broad array of subjects that included mathematics, political economy, logic, history and geography. He learned to speak and write not only in Portuguese, but also Latin and French. He could translate from English and understood German. Even later on, as an emperor, Pedro would devote at least two hours of each day to study and reading.

Despite the breadth of Pedro's instruction, his education proved lacking. Historian Otávio Tarquínio de Sousa said that Pedro "was without a shadow of doubt intelligent, quick-witted, [and] perspicacious." However, historian Roderick J. Barman relates that he was by nature "too ebullient, too erratic, and too emotional". He remained impulsive and never learned to exercise self-control or to assess the consequences of his decisions and adapt his outlook to changes in situations. His father never allowed anyone to discipline him.While Pedro's schedule dictated two hours of study each day, he sometimes circumvented the routine by dismissing his instructors in favor of activities that he found more interesting

The prince found fulfillment in activities that required physical skills, rather than in the classroom. At his father's Santa Cruz farm, Pedro trained unbroken horses, and became a fine horseman and an excellent farrier. He and his brother Miguel enjoyed mounted hunts over unfamiliar ground, through forests, and even at night or in inclement weather. He displayed a talent for drawing and handicrafts, applying himself to wood carving and furniture making. In addition, he had a taste for music, and under the guidance of Marcos Portugal

the prince became an able composer. He had a good singing voice, and was proficient with several musical instruments (including piano, flute and guitar), playing popular songs and dances. Pedro was a simple man, both in habits and in dealing with others. Except on solemn occasions when he donned court dress, his daily attire consisted of white cotton trousers, striped cotton jacket and a broad-brimmed straw hat, or a frock coat and a top hat in more formal situations. He would frequently take time to engage in conversation with people on the street, noting their concerns.

Pedro's character was marked by an energetic drive that bordered on hyperactivity. He was impetuous with a tendency to be domineering and short-tempered. Easily bored or distracted, in his personal life he entertained himself with dalliances with women in addition to his hunting and equestrian activities. His restless spirit compelled him to search for adventure, and, sometimes in disguise as a traveler, he frequented taverns in Rio de Janeiro's disreputable districts. He rarely drank alcohol, but was an incorrigible womanizer. His earliest known lasting affair was with a French dancer called Noémi Thierry, who had a stillborn child by him. Pedro's father, who had ascended the throne as João VI, sent Thierry away to avoid jeopardizing the prince's betrothal to Archduchess Maria Leopoldina, daughter of Emperor Franz I of Austria (formerly Franz II, Holy Roman Emperor).

On 13 May 1817, Pedro was married by proxy to Maria Leopoldina. When she arrived in Rio de Janeiro on 5 November, she immediately fell in love with Pedro, who was far more charming and attractive than she had been led to expect. After "years under a tropical sun, his complexion was still light, his cheeks rosy." The 19-year-old prince was handsome and a little above average in height, with bright dark eyes and dark brown hair. "His good appearance", said historian Neill Macaulay, "owed much to his bearing, proud and erect even at an awkward age, and his grooming, which was impeccable. Habitually neat and clean, he had taken to the Brazilian custom of bathing often." The Nuptial Mass, with the ratification of the vows previously taken by proxy, occurred the following day. Seven children resulted from this marriage: Maria (later Queen Dona Maria II of Portugal), Miguel, João, Januária, Paula, Francisca and Pedro (later Emperor Dom Pedro II of Brazil)

On 17 October 1820, news arrived that the military garrisons in Portugal had mutinied, leading to what became known as the Liberal Revolution of 1820. The military formed a provisional government, supplanting the regency appointed by João VI, and summoned the Cortes—the centuries-old Portuguese parliament, this time democratically elected with the aim of creating a national Constitution. Pedro was surprised when his father not only asked for his advice, but also decided to send him to Portugal to rule as regent on his behalf and to placate the revolutionaries. The prince was never educated to rule and had previously been allowed no participation in state affairs. The role that was his by birthright was instead filled by his elder sister Dona Maria Teresa: João VI had relied on her for advice, and it was she who had been given membership in the Council of State.

Pedro was regarded with suspicion by his father and by the king's close advisers, all of whom clung to the principles of absolute monarchy. By contrast, the prince was a well-known, staunch supporter of liberalism and of constitutional representative monarchy. He had read the works of Voltaire, Benjamin Constant, Gaetano Filangieri and Edmund Burke. Even his wife Maria Leopoldina remarked, "My husband, God help us, loves the new ideas." João VI postponed Pedro's departure for as long as possible, fearing that once he was in Portugal, he would be acclaimed king by the revolutionaries.

On 26 February 1821, Portuguese troops stationed in Rio de Janeiro mutinied. Neither João VI nor his government made any move against the mutinous units. Pedro decided to act on his own and rode to meet the rebels. He negotiated with them and convinced his father to accept their demands, which included naming a new cabinet and making an oath of obedience to the forthcoming Portuguese Constitution. On 21 April, the parish electors of Rio de Janeiro met at the Merchants' Exchange to elect their representatives to the Cortes. A small group of agitators seized the meeting and formed a revolutionary government. Again, João VI and his ministers remained passive, and the monarch was about to accept the revolutionaries' demands when Pedro took the initiative and sent army troops to re-establish order. Under pressure from the Cortes, João VI and his family departed for Portugal on 26 April, leaving behind Pedro and Maria Leopoldina. Two days before he embarked, the King warned his son: "Pedro, if Brazil breaks away, let it rather do so for you, who will respect me, than for one of those adventurers."

At the outset of his regency, Pedro promulgated decrees that guaranteed personal and property rights. He also reduced government expenditure and taxes.Even the revolutionaries arrested in the Merchants' Exchange incident were set free. On 5 June 1821, army troops under Portuguese lieutenant general Jorge Avilez (later Count of Avilez)

mutinied, demanding that Pedro should take an oath to uphold the Portuguese Constitution after it was enacted. The prince rode out alone to intervene with the mutineers. He calmly and resourcefully negotiated, winning the respect of the troops and succeeding in reducing the impact of their more unacceptable demands. The mutiny was a thinly veiled military coup d'état that sought to turn Pedro into a mere figurehead and transfer power to Avilez. The prince accepted the unsatisfactory outcome, but he also warned that it was the last time he would yield under pressure.

The continuing crisis reached a point of no return when the Cortes dissolved the central government in Rio de Janeiro and ordered Pedro's return. This was perceived by Brazilians as an attempt to subordinate their country again to Portugal—Brazil had not been a colony since 1815 and had the status of a kingdom. On 9 January 1822, Pedro was presented with a petition containing 8,000 signatures that begged him not to leave. He replied, "Since it is for the good of all and the general happiness of the Nation, I am willing. Tell the people that I am staying." Avilez again mutinied and tried to force Pedro's return to Portugal. This time the prince fought back, rallying the Brazilian troops (which had not joined the Portuguese in previous mutinies), militia units and armed civilians. Outnumbered, Avilez surrendered and was expelled from Brazil along with his troops.

During the next few months, Pedro attempted to maintain a semblance of unity with Portugal, but the final rupture was impending. Aided by an able minister, José Bonifácio de Andrada,

he searched for support outside Rio de Janeiro. The prince traveled to Minas Gerais in April and on to São Paulo in August. He was welcomed warmly in both Brazilian provinces, and the visits reinforced his authority. While returning from São Paulo, he received news sent on 7 September that the Cortes would not accept self-governance in Brazil and would punish all who disobeyed its orders. "Never one to eschew the most dramatic action on the immediate impulse", said Barman about the prince, he "required no more time for decision than the reading of the letters demanded." Pedro mounted his bay mare and, in front of his entourage and his Guard of Honor, said: "Friends, the Portuguese Cortes wished to enslave and persecute us. As of today our bonds are ended. By my blood, by my honor, by my God, I swear to bring about the independence of Brazil. Brazilians, let our watchword from this day forth be 'Independence or Death!'"

The prince was acclaimed Emperor Dom Pedro I on his 24th birthday, which coincided with the inauguration of the Empire of Brazil on 12 October. He was crowned on 1 December in what is today known as the Old Cathedral of Rio de Janeiro. His ascendancy did not immediately extend throughout Brazil's territories. He had to force the submission of several provinces in the northern, northeastern and southern regions, and the last Portuguese holdout units only surrendered in early 1824. Meanwhile, Pedro IV's relationship with Bonifácio deteriorated. The situation came to a head when Pedro IV, on the grounds of inappropriate conduct, dismissed Bonifácio. Bonifácio had used his position to harass, prosecute, arrest and even exile his political enemies. For months Bonifácio's enemies had worked to win over the Emperor. While Pedro IV was still Prince Regent, they had given him the title "Perpetual Defender of Brazil" on 13 May 1822. They also inducted him into Freemasonry on 2 August and later made him grand master on 7 October, replacing Bonifácio in that position.

The crisis between the monarch and his former minister was felt immediately within the Constituent and Legislative General Assembly, which had been elected for the purpose of drafting a Constitution. A member of the Constituent Assembly, Bonifácio resorted to demagoguery, alleging the existence of a major Portuguese conspiracy against Brazilian interests—insinuating that Pedro IV, who had been born in Portugal, was implicated. The Emperor became outraged by the invective directed at the loyalty of citizens who were of Portuguese birth and the hints that he was himself conflicted in his allegiance to Brazil. On 12 November 1823, Pedro IV ordered the dissolution of the Constituent Assembly and called for new elections. On the following day, he placed a newly established native Council of State in charge of composing a constitutional draft. Copies of the draft were sent to all town councils, and the vast majority voted in favor of its instant adoption as the Constitution of the Empire.

As a result of the highly centralized State created by the Constitution, rebellious elements in Ceará, Paraíba and Pernambuco attempted to secede from Brazil and unite in what became known as the Confederation of the Equator. Pedro IV unsuccessfully sought to avoid bloodshed by offering to placate the rebels. Angry, he said: "What did the insults from Pernambuco require? Surely a punishment, and such a punishment that it will serve as an example for the future." The rebels were never able to secure control over their provinces, and were easily suppressed. By late 1824, the rebellion was over. Sixteen rebels were tried and executed, while all others were pardoned by the Emperor.

After long negotiations, Portugal signed a treaty with Brazil on 29 August 1825 in which it recognized Brazilian independence. Except for the recognition of independence, the treaty provisions were at Brazil's expense, including a demand for reparations to be paid to Portugal, with no other requirements of Portugal. Compensation was to be paid to all Portuguese citizens residing in Brazil for the losses they had experienced, such as properties which had been confiscated. João VI was also given the right to style himself emperor of Brazil. More humiliating was that the treaty implied that independence had been granted as a beneficent act of João VI, rather than having been compelled by the Brazilians through force of arms. Even worse, Great Britain was rewarded for its role in advancing the negotiations by the signing of a separate treaty in which its favorable commercial rights were renewed and by the signing of a convention in which Brazil agreed to abolish slave trade with Africa within four years. Both accords were severely harmful to Brazilian economic interests.

A few months later, the Emperor received word that his father had died on 10 March 1826, and that he had succeeded his father on the Portuguese throne as King Dom Pedro IV. Aware that a reunion of Brazil and Portugal would be unacceptable to the people of both nations, he hastily abdicated the crown of Portugal on 2 May in favor of his eldest daughter, who became Queen Dona Maria II. His abdication was conditional: Portugal was required to accept the Constitution which he had drafted and Maria II was to marry his brother Miguel. Regardless of the abdication, Pedro IV continued to act as an absentee king of Portugal and interceded in its diplomatic matters, as well as in internal affairs, such as making appointments. He found it difficult, at the very least, to keep his position as Brazilian emperor separate from his obligations to protect his daughter's interests in Portugal.

Miguel feigned compliance with Pedro IV's plans. As soon as he was declared regent in early 1828, and backed by Carlota Joaquina, he abrogated the Constitution and, supported by those Portuguese in favor of absolutism, was acclaimed King Dom Miguel I. As painful as was his beloved brother's betrayal, Pedro IV also endured the defection of his surviving sisters, Maria Teresa, Maria Francisca, Isabel Maria and Maria da Assunção, to Miguel I's faction. Only his youngest sister, Ana de Jesus, remained faithful to him, and she later traveled to Rio de Janeiro to be close to him. Consumed by hatred and beginning to believe rumors that Miguel I had murdered their father, Pedro IV turned his focus on Portugal and tried in vain to garner international support for Maria II's rights

Backed by the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata (present-day Argentina), a small band declared Brazil's southernmost province of Cisplatina to be independent in April 1825.The Brazilian government at first perceived the secession attempt as a minor uprising. It took months before a greater threat posed by the involvement of the United Provinces, which expected to annex Cisplatina, caused serious concern. In retaliation, the Empire declared war in December, triggering the Cisplatine War. The Emperor traveled to Bahia province (located in northeastern Brazil) in February 1826, taking along his wife and daughter Maria. The Emperor was warmly welcomed by the inhabitants of Bahia.The trip was planned to generate support for the war-effort.

The imperial entourage included Domitila de Castro (then-Viscountess and later Marchioness of Santos),

who had been Pedro IV's mistress since their first meeting in 1822. Although he had never been faithful to Maria Leopoldina, he had previously been careful to conceal his sexual escapades with other women. However, his infatuation for his new lover "had become both blatant and limitless", while his wife endured slights and became the object of gossip. Pedro IV was increasingly rude and mean toward Maria Leopoldina, left her short of funds, prohibited her from leaving the palace and forced her to endure Domitila's presence as her lady-in-waiting. In the meantime, his lover took advantage by advancing her interests, as well as those of her family and friends. Those seeking favors or to promote projects increasingly sought her help, bypassing the normal, legal channels.

On 24 November 1826, Pedro IV sailed from Rio de Janeiro to São José in the province of Santa Catarina. From there he rode to Porto Alegre, capital of the province of Rio Grande do Sul, where the main army was stationed. Upon his arrival on 7 December, the Emperor found the military conditions to be much worse than previous reports had led him to expect. He "reacted with his customary energy: he passed a flurry of orders, fired reputed grafters and incompetents, fraternized with the troops, and generally shook up military and civilian administration." He was already on his way back to Rio de Janeiro when he was told that Maria Leopoldina had died following a miscarriage. Unfounded rumors soon spread that purported that she had died after being physically assaulted by Pedro IV. Meanwhile, the war continued on with no conclusion in sight. Pedro IV relinquished Cisplatina in August 1828, and the province became the independent nation of Uruguay.

After his wife's death, Pedro IV realized how miserably he had treated her, and his relationship with Domitila began to crumble. Maria Leopoldina, unlike his mistress, was popular, honest and loved him without expecting anything in return. The Emperor greatly missed her, and even his obsession with Domitila failed to overcome his sense of loss and regret. One day Domitila found him weeping on the floor and embracing a portrait of his deceased wife, whose sad-looking ghost Pedro IV claimed to have seen. Later on, the Emperor left the bed he shared with Domitila and shouted: "Get off of me! I know I live an unworthy life of a sovereign. The thought of the Empress does not leave me."He did not forget his children, orphaned of their mother, and was observed on more than one occasion holding his son, the young Pedro, in his arms and saying: "Poor boy, you are the most unhappy prince in the world."

At the insistence of Pedro IV, Domitila departed from Rio de Janeiro on 27 June 1828. He had resolved to marry again and to become a better person. He even tried to persuade his father-in-law of his sincerity, by claiming in a letter "that all my wickedness is over, that I shall not again fall into those errors into which I have fallen, which I regret and have asked God for forgiveness".Franz I was less than convinced. The Austrian emperor, deeply offended by the conduct his daughter endured, withdrew his support for Brazilian concerns and frustrated Pedro IV's Portuguese interests. Because of Pedro IV's bad reputation in Europe, owing to his past behavior, princesses from several nations declined his proposals of marriage one after another. His pride thus wounded, he allowed his mistress to return, which she did on 29 April 1829 after having been away nearly a year.

However, once he learned that a betrothal had finally been arranged, the Emperor ended his relationship to Domitila. She returned to her native province of São Paulo on 27 August, where she remained. Days earlier, on 2 August, the Emperor had been married by proxy to Amélie of Leuchtenberg. He was stunned by her beauty after meeting her in person. The vows previously made by proxy were ratified in a Nuptial Mass on 17 October. Amélie was kind and loving to his children and provided a much needed sense of normality to both his family and the general public. After Domitila's banishment from court, the vow the Emperor made to alter his behavior proved to be sincere. He had no more affairs and remained faithful to his spouse. In an attempt to mitigate and move beyond other past misdeeds, he made peace with José Bonifácio, his former minister and mentor.

Since the days of the Constituent Assembly in 1823, and with renewed vigor in 1826 with the opening of the General Assembly (the Brazilian parliament), there had been an ideological struggle over the balance of powers wielded by the emperor and legislature in governance. On one side were those who shared Pedro IV's views, politicians who believed that the monarch should be free to choose ministers, national policies and the direction of government. In opposition were those, then known as the Liberal Party, who believed that cabinets should have the power to set the government's course and should consist of deputies drawn from the majority party who were accountable to the parliament. Strictly speaking, both the party that supported Pedro IV's government and the Liberal Party advocated Liberalism, and thus constitutional monarchy.

Regardless of Pedro IV's failures as a ruler, he respected the Constitution: he did not tamper with elections or countenance vote rigging, refuse to sign acts ratified by the government, or impose any restrictions on freedom of speech. Although within his prerogative, he did not dissolve the Chamber of Deputies and call for new elections when it disagreed with his aims or postpone seating the legislature. Liberal newspapers and pamphlets seized on Pedro IV's Portuguese birth in support of both valid accusations (e.g., that much of his energy was directed toward affairs concerning Portugal) and false charges (e.g., that he was involved in plots to suppress the Constitution and to reunite Brazil and Portugal).To the Liberals, the Emperor's Portuguese-born friends who were part of the Imperial court, including Francisco Gomes da Silva who was nicknamed "the Buffoon", were part of these conspiracies and formed a "secret cabinet". None of these figures exhibited interest in such issues, and whatever interests they may have shared, there was no palace cabal plotting to abrogate the Constitution or to bring Brazil back under Portugal's control.

Another source of criticism by the Liberals involved Pedro IV's abolitionist views. The Emperor had indeed conceived a gradual process for eliminating slavery. However, the constitutional power to enact legislation was in the hands of the Assembly, which was dominated by slave-owning landholders who could thus thwart any attempt at abolition.The Emperor opted to try persuasion by moral example, setting up his estate at Santa Cruz as a model by granting land to his freed slaves there. Pedro IV also professed other advanced ideas. When he declared his intention to remain in Brazil on 9 January 1822 and the populace sought to accord him the honor of unhitching the horses and pulling his carriage themselves, the then-Prince Regent refused. His reply was a simultaneous denunciation of the divine right of kings, of nobility's supposedly superior blood and of racism: "It grieves me to see my fellow humans giving a man tributes appropriate for the divinity, I know that my blood is the same color as that of the Negroes."

The Emperor's efforts to appease the Liberal Party resulted in very important changes. He supported an 1827 law that established ministerial responsibility. On 19 March 1831, he named a cabinet formed by politicians drawn from the opposition, allowing a greater role for the parliament in the government. Lastly, he offered positions in Europe to Francisco Gomes and another Portuguese-born friend to extinguish rumors of a "secret cabinet".To his dismay, his palliative measures did not stop the continuous attacks from the Liberal side upon his government and his foreign birth. Frustrated by their intransigence, he became unwilling to deal with his deteriorating political situation.

Meanwhile, Portuguese exiles campaigned to convince him to give up on Brazil and instead devote his energies to the fight for his daughter's claim to Portugal's crown. According to Roderick J. Barman, "[in] an emergency the Emperor's abilities shone forth—he became cool in nerve, resourceful and steadfast in action. Life as a constitutional monarch, full of tedium, caution, and conciliation, ran against the essence of his character." On the other hand, the historian remarked, he "found in his daughter's case everything that appealed most to his character. By going to Portugal he could champion the oppressed, display his chivalry and self-denial, uphold constitutional rule, and enjoy the freedom of action he craved."

The idea of abdicating and returning to Portugal took root in his mind, and, beginning in early 1829, he talked about it frequently. An opportunity soon appeared to act upon the notion. Radicals within the Liberal Party rallied street gangs to harass the Portuguese community in Rio de Janeiro. On 11 March 1831, in what became known as the "noite das garrafadas" (night of the broken bottles), the Portuguese retaliated and turmoil gripped the streets of the national capital. On 5 April, Pedro IV fired the Liberal cabinet, which had only been in power since 19 March, for its incompetence in restoring order. A large crowd, incited by the radicals, gathered in Rio de Janeiro downtown on the afternoon of 6 April and demanded the immediate restoration of the fallen cabinet. The Emperor's reply was: "I will do everything for the people and nothing [compelled] by the people." Sometime after nightfall, army troops, including his guard, deserted him and joined the protests. Only then did he realize how isolated and detached from Brazilian affairs he had become, and to everyone's surprise, he abdicated at approximately 03:00 on 7 April. Upon delivering the abdication document to a messenger, he said: "Here you have my act of abdication, I'm returning to Europe and leaving a country that I loved very much, and still love."

At dawn on the morning of 7 April, Pedro, his wife, and others, including his daughter Maria II and his sister Ana de Jesus, were taken on board the British warship HMS Warspite.

The vessel remained at anchor off Rio de Janeiro, and, on 13 April, the former emperor transferred to and departed for Europe aboard HMS Volage. He arrived in Cherbourg-Octeville, France, on 10 June. During the next few months, he shuttled between France and Great Britain. He was warmly welcomed, but received no actual support from either government to restore his daughter's throne. Finding himself in an awkward situation because he held no official status in either the Brazilian Imperial House or in the Portuguese Royal House, Pedro assumed the title of Duke of Bragança on 15 June, a position that once had been his as heir to Portugal's crown. Although the title should have belonged to Maria II's heir, which he certainly was not, his claim was met with general recognition. On 1 December, his only daughter by Amélie, Maria Amélia, was born in Paris.

He did not forget his children left in Brazil. He wrote poignant letters to each of them, conveying how greatly he missed them and repeatedly asking them to seriously attend to their educations. Shortly before his abdication, Pedro had told his son and successor: "I intend that my brother Miguel and I will be the last badly educated of the Bragança family". Charles Napier, a naval commander who fought under Pedro's banner in the 1830′s, remarked that "his good qualities were his own; his bad owing to want of education; and no man was more sensible of that defect than himself." His letters to Pedro II were often couched in language beyond the boy's reading level, and historians have assumed such passages were chiefly intended as advice that the young monarch might eventually consult upon reaching adulthood.

While in Paris, the Duke of Bragança met and befriended Gilbert du Motier, Marquis of Lafayette,

a veteran of the American Revolutionary War who became one of his staunchest supporters. With limited funds, Pedro organized a small army composed of Portuguese liberals, like Almeida Garrett

and Alexandre Herculano,

foreign mercenaries and volunteers such as Lafayette's grandson, Adrien Jules de Lasteyrie. On 25 January 1832, Pedro bade farewell to his family, Lafayette and around two hundred well-wishers. He knelt before Maria II and said: "My lady, here is a Portuguese general who will uphold your rights and restore your crown." In tears, his daughter embraced him. Pedro and his army sailed to the Atlantic archipelago of the Azores, the only Portuguese territory that had remained loyal to his daughter. After a few months of final preparations they embarked for mainland Portugal, entering the city of Porto unopposed on 9 July. His brother's troops moved to encircle the city, beginning a siege that lasted for more than a year.

In early 1833, while besieged in Porto, Pedro received news from Brazil of his daughter Paula's impending death. Months later, in September, he met with Antônio Carlos de Andrada, a brother of Bonifácio who had come from Brazil. As a representative of the Restorationist Party, Antônio Carlos asked the Duke of Bragança to return to Brazil and rule his former empire as regent during his son's minority. Pedro realized that the Restorationists wanted to use him as a tool to facilitate their own rise to power, and frustrated Antônio Carlos by making several demands, to ascertain whether the Brazilian people, and not merely a faction, truly wanted him back. He insisted that any request to return as regent be constitutionally valid. The people's will would have to be conveyed through their local representatives and his appointment approved by the General Assembly. Only then, and "upon the presentation of a petition to him in Portugal by an official delegation of the Brazilian parliament" would he consider accepting.

During the war, the Duke of Bragança mounted cannons, dug trenches, tended the wounded, ate among the rank and file and fought under heavy fire as men next to him were shot or blown to pieces. His cause was nearly lost until he took the risky step of dividing his forces and sending a portion to launch an amphibious attack on southern Portugal. The Algarve region fell to the expedition, which then marched north straight for Lisbon, which capitulated on 24 July. Pedro proceeded to subdue the remainder of the country, but just when the conflict looked to be winding down to a conclusion, his Spanish uncle Don Carlos, who was attempting to seize the crown of his niece Doña Isabel II,

intervened. In this wider conflict that engulfed the entire Iberian Peninsula, the First Carlist War, the Duke of Bragança allied with liberal Spanish armies loyal to Isabel II and defeated both Miguel I and Carlos. A peace accord was reached on 26 May 1834.

Except for bouts of epilepsy that manifested in seizures every few years, Pedro had always enjoyed robust health. The war, however, undermined his constitution and by 1834 he was dying of tuberculosis. He was confined to his bed in Queluz Royal Palace from 10 September. Pedro dictated an open letter to the Brazilians, in which he begged that a gradual abolition of slavery be adopted. He warned them: "Slavery is an evil, and an attack against the rights and dignity of the human species, but its consequences are less harmful to those who suffer in captivity than to the Nation whose laws allow slavery. It is a cancer that devours its morality." After a long and painful illness, Pedro died at 14:30 on 24 September 1834.

As he had requested, his heart was placed in Porto's Lapa Church and his body was interred in the Royal Pantheon of the House of Braganza.

The news of his death arrived in Rio de Janeiro on 20 November, but his children were informed only after 2 December. Bonifácio, who had been removed from his position as their guardian, wrote to Pedro II and his sisters: "Dom Pedro did not die. Only ordinary men die, not heroes."

Upon the death of Pedro IV, the then-powerful Restorationist Party vanished overnight. A fair assessment of the former monarch became possible once the threat of his return to power was removed. Evaristo da Veiga, one of his worst critics as well as a leader in the Liberal Party, left a statement which, according to historian Otávio Tarquínio de Sousa, became the prevailing view thereafter: "the former emperor of Brazil was not a prince of ordinary measure ... and Providence has made him a powerful instrument of liberation, both in Brazil and in Portugal. If we [Brazilians] exist as a body in a free Nation, if our land was not ripped apart into small enemy republics, where only anarchy and military spirit predominated, we owe much to the resolution he took in remaining among us, in making the first shout for our Independence." He continued: "Portugal, if it was freed from the darkest and demeaning tyranny ... if it enjoys the benefits brought by representative government to learned peoples, it owes it to D[om]. Pedro de Alcântara, whose fatigues, sufferings and sacrifices for the Portuguese cause has earned him in high degree the tribute of national gratitude."

John Armitage, who lived in Brazil during the latter half of Pedro IV's reign, remarked that "even the errors of the Monarch have been attended with great benefit through their influence on the affairs of the mother country. Had he governed with more wisdom it would have been well for the land of his adoption, yet, perhaps, unfortunate for humanity." Armitage added that like "the late Emperor of the French, he was also a child of destiny, or rather, an instrument in the hands of an all-seeing and beneficent Providence for the furtherance of great and inscrutable ends. In the old as in the new world he was henceforth fated to become the instrument of further revolutions, and ere the close of his brilliant but ephemeral career in the land of his fathers, to atone amply for the errors and follies of his former life, by his chivalrous and heroic devotion in the cause of civil and religious freedom."

In 1972, on the 150th anniversary of Brazilian independence, Pedro IV's remains (though not his heart) were brought to Brazil—as he had requested in his will—accompanied by much fanfare and with honors due to a head of state. His remains were reinterred in the Monument to the Independence of Brazil, along with those of Maria Leopoldina and Amélie, in the city of São Paulo.

Years later, Neill Macaulay said that "[c]riticism of Dom Pedro was freely expressed and often vehement; it prompted him to abdicate two thrones. His tolerance of public criticism and his willingness to relinquish power set Dom Pedro apart from his absolutist predecessors and from the rulers of today's coercive states, whose lifetime tenure is as secure as that of the kings of old." Macaulay affirmed that "[s]uccessful liberal leaders like Dom Pedro may be honored with an occasional stone or bronze monument, but their portraits, four stories high, do not shape public buildings; their pictures are not borne in parades of hundreds of thousands of uniformed marchers; no '-isms' attach to their names.”

King Pedro IV had several children:

By Maria Leopoldina of Austria (22 January 1797 – 11 December 1826; married by proxy on 13 May 1817):

Maria II of Portugal (4 April 1819 –15 November 1853) Queen of Portugal from 1826 until 1853. Maria II's first husband, Auguste de Beauharnais, 2nd Duke of Leuchtenberg, died a few months after the marriage. Her second husband was Prince Ferdinand of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, who became King Dom Fernando II after the birth of their first child. She had eleven children from this marriage. Maria II was heir to her brother Pedro II as Princess Imperial until her exclusion from the Brazilian line of succession by law no. 91 of 30 October 1835.

Miguel, Prince of Beira (26 April 1820) Prince of Beira from birth to his death.

João Carlos, Prince of Beira (6 March 1821 – 4 February 1822) Prince of Beira from birth to his death.

Princess Januária of Brazil (11 March 1822 – 13 March 1901) Married Prince Luigi, Count of Aquila, son of Don Francesco I, King of the Two Sicilies. She had four children from this marriage. Officially recognized as an Infanta of Portugal on 4 June 1822, she was later considered excluded from the Portuguese line of succession after Brazil became independent.

Princess Paula of Brazil (17 February 1823 – 16 January 1833) She died age 9, probably of meningitis. Born in Brazil after its independence, Paula was excluded from the Portuguese line of succession.

Princess Francisca of Brazil (2 August 1824 – 27 March 1898) Married Prince François, Prince of Joinville, son of Louis Philippe I, King of the French. She had three children from this marriage. Born in Brazil after its independence, Francisca was excluded from the Portuguese line of succession.

Pedro II of Brazil (2 December 1825 –5 December 1891) Emperor of Brazil from 1831 until 1889. He was married to Teresa Cristina of the Two Sicilies, daughter of Don Francesco I, King of the Two Sicilies. He had four children from this marriage. Born in Brazil after its independence, Pedro II was excluded from the Portuguese line of succession and did not become King Dom Pedro V of Portugal upon his father's abdication.

By Amélie of Leuchtenberg (31 July 1812 – 26 January 1873; married by proxy on 2 August 1829):

Princess Maria Amélia of Brazil (1 December 1831 – 4 February 1853) She lived her entire life in Europe and never visited Brazil. Maria Amélia was betrothed to Archduke Maximilian, later Emperor Don Maximiliano I of Mexico, but died before her marriage. Born years after her father abdicated the Portuguese crown, Maria Amélia was never in the line of succession to the Portuguese throne.

By Domitila de Castro, Marchioness of Santos (27 December 1797 – 3 November 1867):

Isabel Maria de Alcântara Brasileira (23 May 1824 – 3 November 1898) She was the only child of Pedro IV born out of wedlock who was officially legitimized by him. On 24 May 1826, Isabel Maria was given the title of "Duchess of Goiás", the style of Highness and the right to use the honorific "Dona" (Lady). She was the first person to hold the rank of duke in the Empire of Brazil. These honors did not confer on her the status of Brazilian princess or place her in the line of succession. In his will, Pedro IV gave her a share of his estate. She later lost her Brazilian title and honors upon her 17 April 1843 marriage to a foreigner, Ernst Fischler von Treuberg, Count of Treuberg.

Pedro de Alcântara Brasileiro (7 December 1825 – 27 December 1825) Pedro IV seems to have considered giving him the title of "Duke of São Paulo", which was never realized due to the child's early death.

Maria Isabel de Alcântara Brasileira (13 August 1827 – 25 October 1828) Pedro IV considered giving her the title of "Duchess of Ceará", the style of Highness and the right to use the honorific "Dona" (Lady). This was never put into effect due to her early death. Nonetheless, it is quite common to see many sources calling her "Duchess of Ceará", even though "there is no record of the registry of her title in official books, which is also not mentioned in papers related to her funeral".

Maria Isabel de Alcântara Brasileira (28 February 1830 – 13 September 1896) Countess of Iguaçu through marriage in 1848 to Pedro Caldeira Brant, son of Felisberto Caldeira Brant, Marquis of Barbacena. She was never given any titles by her father due to his marriage to Amélie. However, Pedro IV acknowledged her as his daughter in his will, but gave her no share of his estate, except for a request that his widow aid in her education and upbringing.

By Maria Benedita, Baroness of Sorocaba (18 December 1792 – 5 March 1857):

Rodrigo Delfim Pereira (4 November 1823 –31 January 1891) In his will, Pedro IV acknowledged him as his son and gave him a share of his estate. Rodrigo Delfim Pereira became a Brazilian diplomat and lived most of his life in Europe.

By Henriette Josephine Clemence Saisset:

Pedro de Alcântara Brasileiro born 28 August 1829. In his will, Pedro IV acknowledged him as his son and gave him a share of his estate. Pedro de Alcântara Brasileiro had a son, a French navy officer, among other descendants.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Catalan Independence Movement: A New Chapter of Unrest—Chronicling a Week of Escalation

Starting Monday, in response to draconian sentences imposed on politicians who promote Catalan independence, tens of thousands of people across Catalunya have engaged in sustained rioting and disruption. Although the majority of the movement remains pacifistic, a few thousand participants have rejected the leadership of political parties and organizations, opting for open confrontation with police. The various mobilizations are still taking place in confluence, however, making it very difficult for the police to control. Protesters have reportedly used caltrops, Molotov cocktails, and paint balloons to disable police riot vans, while keeping individual officers at a distance with lasers and slingshots and driving away helicopters with fireworks. In the following report, we review the events of the past week and explore what is at stake in this struggle.

As anarchists, we have a more robust conception of self-determination than mere national sovereignty. All governments are based on the asymmetry of power between ruler and ruled; nationalism is just one of several means by which rulers seek to turn us against each other so we don’t unite against them. We consider it instructive that the Catalan police have worked closely with Spanish national police throughout the last several years of repression; even if Catalunya gains independence, we are certain that independent Catalan police and courts will continue to repress those who fight against capitalism and seek true self-determination. At the same time, there is a longstanding tradition of anarchist and anti-state activity in Catalunya, and we are inspired to see some of this coming to the fore in resistance to the violence of the Spanish state. It is possible that the latest escalation of conflict in the streets of Catalunya will be a step towards the radicalization of the entire movement and the delegitimizing of state solutions.

Let’s look closer to see.

Members of Committees for the Defense of the Republic gather outside the Civil Guard barracks during a protest after nine activists associated with the Catalan independence movement were detained by police in Barcelona, Spain September 23, 2019.

Monday, October 14

In retribution for the 2017 referendum and subsequent declaration of independence, Spain’s Supreme Court sentenced former Catalan vice president Oriol Junqueras to 13 years in prison; former ministers Jordi Turull, Raül Romeva, Dolors Bassa, Joaquim Forn, and Josep Rull were sentenced to between 10 and 12 years apiece. Former parliament speaker, Carme Forcadell, received 11 and a half years for sedition. Activists Jordi Sànchez and Jordi Cuixart were sentenced to 9 years each, also for sedition.

Several independence groups called for demonstrations and blockaded major roads in Barcelona. Early Monday afternoon, the Tsunami Democràtic group called for demonstrators to blockade the Barcelona airport. There were also blockades on train lines and many highways.

Showing the integrated functioning of all the different subsections of the state, the Catalan and Spanish police—the Mossos d’Esquadra and Policia Nacional—worked together to repress the demonstrators. They brutally attacked a large number of people. Still, as in 2017, the vast majority of demonstrators remained “nonviolent” in response. Some young people start to throw trash and light objects at police.

Tuesday, October 15

On Tuesday, the blockades organized by “Tsunami Democràtic” continued on a largely “nonviolent” basis, slowing and in some cases paralyzing rail, car, and air transit. More protests broke out that night. Goaded by police violence, people began to fight back, throwing heavier objects and setting fires in the streets.

The Assemblea Nacional Catalana (“Catalan National Assembly,” ANC) and various political parties had convened columns to march from across Catalunya starting Wednesday, taking the highways and thus blocking them, in order to arrive in Barcelona on Friday for a general strike and protest. The plan was for this action to be totally pacifist. This was basically a repetition of their 2017 strategy, in which they organized demonstrations on October 3, two days after the massive police beatings that occurred during the referendum on October 1, waiting an extra day before holding the protest in response to government repression so that people wouldn’t be reacting immediately to the violence without a chance to calm down.

Yet they also gave their approval to Tsunami Democràtic, which had planned all along to organize flash-mob-style protests immediately following the verdict. These protests, too, were intended to be completely nonviolent, but to take a more effective approach—targeting infrastructure rather than merely symbolic points. Either the organizers underestimated how many people would show up and stay into the night, or they overestimated their ability to impose pacifism after the 2017 experience.

Starting Tuesday night, events were clearly out of their hands. In Catalunya, the extent to which people employ combative and destructive tactics is generally a useful indicator of the autonomy of a particular demonstration, even though in and of itself utilizing more confrontational tactics doesn’t necessary imply a radical agenda. The parties have always insisted that everything must be peaceful, just as they have watered down the meaning of “independence,” using nationalistic discourse to and suppressing the anti-capitalist objectives that used to characterize the movement.

Thousands of people protest the sentencing in front of Generalitat local office in Gerona, Catalunya on October 14, 2019.

It’s not easy to summarize the political ideas of people fighting in the streets on the basis of their conduct, but it seems that the pacifists remain under the ideological dominance of the parties and “civil society” organizations like ANC and Omnium, whereas those putting up barricades appear to be open to a much wider vision of what the enemy is and the objectives of the actions could be. The former tend to be middle-class (or aspiring middle-class) and exclusively Catalan speakers; the latter group is much more diverse, including Spanish speakers (though still mostly Catalan speakers), immigrants, and others. When the more confrontational demonstrators express themselves, they tend to express opposition to the police, “the fascist Spanish state,” and to mention more economic issues.

We should always challenge the assumption that a movement is about one thing. A movement is only about one thing where there is an effective leadership controlling it. Left to themselves, people don’t tend to reduce their concerns to single issues. Reality is intersectional.

Hats off to the anarchists and other anti-authoritarian activists who have spent the last two years spreading non-statist, non-nationalist perspectives and analysis relating to this issue and creating the autonomous, horizontal spaces that have cropped up in this movement since 2017, outside the dominance of the political parties and the Marxist-Lenininsts who dominated the indepe movement before 2013. The emergence of this autonomous space is the key difference that distinguishes what is happening today from what happened in 2017—and we’re seeing its fruits in what is taking place in the streets.

Another major factor in the way that people in Catalunya have behaved ungovernably this week is that the Spanish state was stupid enough to imprison the pacifist politicians and CC activists who had effectively pacified the movement in 2017. The ones who had already effectively killed this movement, it seemed, until now.

Never underestimate states. Also, never underestimate statist stupidity.

The Mossos charge [???] against protesters in the center of Barcelona on the night following Tuesday, October 15, 2019.

Wednesday, October 16

On Wednesday, high school and university students declared a strike, which continued through Friday. ANC marches and highway blockades set out from many major cities. In the evening, people engaged in very serious rioting in Barcelona; substantial rioting took place in all three other provincial capitals, not to mention smaller cities like Manresa. Many of the clashes occurred outside the Delegations of the (Spanish) government or Guardia Civil barracks. There had already been significant rioting in Lleida and Tarragona on Tuesday night.

Catalan president Quim Torra and ex-president Carles Puigdemont declared that the rioters were “infiltrators,” but only the immediate followers of those politicians were stupid enough to believe this. The usual absurd conspiracy theories spread across social networks about masked protesters getting paid in envelopes of cash.

In Madrid, a fairly large anti-fascist, pro-Catalan demonstration took place at the same time as a fascist march against independence. The two demonstrations clashed and police separated them.

Police charged through the crowd several times with batons and fired foam projectiles at people.

Thursday, October 17

ANC marches continued. Rioting took place again that night in Barcelona and other three provincial capitals. Fascists marched in favor of Spanish unity in Barcelona, attacking some protesters in favor of independence.

Friday, October 18

Today, the general strike is taking place in Catalunya. A Spanish judge has ordered that webpages linked to Tsunami Democratíc must be shut down—something similar to China forcing Apple to shut down an app used by demonstrators in Hong Kong.

The conservative People’s Party (PP) is calling for the application of the National Security Law—essentially, martial law. Meanwhile, it appears that a new political consensus may be forming. For a couple years Spain hasn’t been able to form an effective majority government; elections took place earlier in the year, but will have to take place again in November, because disagreements prevented the Socialists from forming a coalition government with Podemos. The fighting in Catalunya is driving a wedge between Podemos (which takes a soft approach based in dialogue, potentially open to a “legitimate” referendum) and Socialists (who take a hard approach rejecting any possibility of dialogue or self-determination). This creates the possibility of a coalition government involving the Socialists and the PP—assuming the PP, Citizens, and Vox parties don’t get enough votes to comprise the majority on their own, which they very well might not, as Spain remains majority left.

The riot cops are exhausted, probably only running on cocaine at this point. There are videos circulating of riot vans carousing down the streets with the cops using their sound cannons to shout “Som gent de pau.” This means “we are people of peace”—it is the slogan of the independence parties, but the cops mean it in a mocking, provocative tone. There are cases of the Mossos discipline breaking, of individual officers being isolated and beaten up, which never happened during the strikes of 2010 to 2012 or even the week of the eviction of the anarchist social center Can Vies. Several times, police were forced to retreat by combatants hurling rocks and even some Molotov cocktails. Even at the high point of the resistance defending Can Vies, it was rare to see police retreat; they just had to work really hard to advance, at which point rioters simply went elsewhere.

A mainstream newspaper reported today that fully half of the police riot vans have been decommissioned by damages, primarily to tires. It’s unclear how quickly they can repair them. If they lose their vans, they will be powerless; there are too many people in the street, using too much force. The state would have to send in the Guardia Civil or the military proper to maintain what they call “order.”

The real question is what will happen tomorrow, on Saturday. Today could serve as a catharsis, ending the unrest; it could be effectively repressed, if police bring in new resources and tactics; or it could be the day that the state recognizes that it has lost control and has to esclate repression. During the riots defending Can Vies, it was after the fourth day that the state recognized it had lost; on the fifth day, everyone was exhausted so the march was just a victory lap. But now, with perhaps double the number of police but several times as many participants, spread throughout Catalunya, the movement won’t tire as quickly. Though the pacifists condemn the rioting, they’re still marching and blocking highways, thereby adding to the difficulty for the state.

The Mossos cross a burning barricade in Barcelona to charge protesters.

The Backstory, the Future

The Iberian peninsula has seen conflict between monarchists, capitalists, fascists, and proponents of state democracy, on one side, and anarchists and other proponents of liberation since long before the Spanish Civil War. It’s important to remember that the independence movement only took center stage in Catalunya after countrywide anti-capitalist struggle reached an impasse, undermined by many participants’ erroneous belief that democracy—direct or otherwise—could bring about the changes they desired.

In 2011, the 15M movement, a forerunner of Occupy, broke out in Spain, occupying plazas and clashing with police. That was just one chapter in a phase of struggle arguably peaked on March 29, 2012 with massive riots during a nationwide general strike. All around the world, this was a high point of grassroots struggle against the inequalities of capitalism and the violence of the state.

Yet rather than continuing to invest energy in grassroots direct action as a means of enacting change, many who had promoted direct democracy in the plaza occupations shifted to trying to rehabilitate state democracy via new parties like Podemos. Ultimately, as we chronicled here, the results were disappointing, serving to pacify the social movements without achieving their original goals.

In the ensuing vacuum, the independentista movement gained momentum, proposing a referendum as a way to make Catalunya independent—promising a state solution to the problems that had originally inspired people to mobilize against capitalism and government oppression. When Spain cracked down violently on the referendum, this left anarchists in an awkward position, wanting to oppose police violence but not to endorse national independence as the solution to the problems engendered by capitalism and the state. Of course, it wasn’t just Spanish police participating in the crackdown—it was also Catalan police. All the institutions that would supposedly serve the people after independence were already being used against them, as they surely will continue to be if Catalunya does at some point become an independent state.

All this shows the problems with nationalism and democracy. We support people in Catalunya defending themselves from police, courts, and other institutions of power; this is why the events of this week have been inspiring. But ultimately self-determination means abolishing these institutions, not reforming or reinventing them. The question remains whether the current struggle in Catalunya will radicalize more of the participants towards anarchist solutions or simply towards more violent means of pursuing national sovereignty. But those at the forefront of events will surely have disproportionate influence on the answer to that question.

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

Moving up the judicial ladder to Brasília, where the Supreme Court presides, the same cannot be said. There, neither ethical rigour nor ideological fervour is anywhere in sight: motivations are of an altogether different, more squalid order. Unlike its counterparts anywhere else in the world, the Brazilian Supreme Court combines three functions: it interprets the constitution, acts as the last court of appeal in civil and criminal cases and, crucially, is alone empowered to try public officials – members of Congress and ministers – who otherwise enjoy immunity from prosecution, popularly known as foro privilegiado, in all other courts of the land. Its 11 members are appointed by the executive; their confirmation by the legislature, quite unlike in the US, is no more than pro forma. Previous experience on the bench is not required: only three of the current justices have any. Mere practice as a lawyer or a prosecutor, with a smattering of academic credentials, is the usual background.