#jim knipfel

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

“You think I’m the only one in this town who doesn’t like people?”

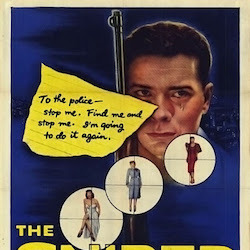

Following the JFK assassination, and especially after Charles Whitman climbed the Texas Tower in August of 1966, shooting and killing 14 strangers over the course of a lazy afternoon, lone mad snipers became an easy thriller standby. Targets, The Day of the Jackal, Two Minute Warning and dozens of other films since the late ‘60s have focused on a man, a rifle, and a perch. While snipers weren’t unknown to Hollywood prior to 1963 (Suddenly, Murder by Contract—even The Manchurian Candidate was in production before the assassination), they focused almost exclusively on gunmen with a purpose, paid assassins who were after a single, specific target, a politician or a mob hit. 1952’s The Sniper was not only one of the earliest films centered around an urban sniper, but remained an exception, really until the moment Whitman began pulling the trigger.

While on the surface The Sniper is a standard, straightforward police procedural about the hunt for a killer, what made it different was that the killer in question was a presumably unbalanced presumed vet who was killing random brunettes around San Francisco with a high-powered Army-issue carbine rifle. What also made the film different for the era was its focus on the psychology (some boilerplate Freudian hoo-hah) driving the killing spree. But beyond even all that, deep down it’s a profoundly strange picture disguised, for all its groundbreaking elements, as any other B thriller.

But let me back up here a second and come at this from a different angle.

In 1945, like so many intellectuals and Hollywood types (and when was the last time those two appeared in the same sentence?), director Edward Dmytryk began his little flirtation with the Communist Party. A few years later, like so many others, he found himself dragged in front of HUAC where he was asked to name names. When he refused, he was thrown in stir along with the rest of the Hollywood Ten on charges of contempt of Congress.

After a few months in prison, though, Dmytryk had a change of heart and called his lawyer. In 1951 he was released from prison, appeared before HUAC again, but this time in a far more cooperative mood, providing interrogators not only with 26 names, but also detailing how he’d been pressured to slip subliminal Commie messages into pictures like Crossfire. After this, having lost his martyrdom and no longer beloved of Hollywood’s Communist community, Dmytryk found himself just as effectively blacklisted as he had been before. So he moved to England and teamed up with producer Stanley Kramer, who would put him back to work for the next several years.

This is not the place to discuss Dmytryk’s politics, his justification or damnation, to pass self-righteous judgments long after the fact. But it is interesting to consider the first film made by a man fresh out of prison would be a message film about a rogue gunman picking off Californian brunettes, and one has to wonder if his time behind bars in any way influenced the film’s opening crawl.

Written by a powerhouse trio at the time (script by Harry Brown from a story by Edna and Edward Anhalt), The Sniper opens by informing us that present-day laws and law enforcement were useless when it came to dealing with sex crimes, and that the story we were about to see concerned a man “whose enemy was womankind.”

In the film’s first few seconds we meet the man in question, Eddie Miller, and it’s clear he’s teetering on the edge of something bad. Arthur Franz hadn’t yet established himself as a genre stalwart, playing rational, low-key, friendly sorts in the likes of Invaders from Mars and Monster on the Campus, and here turns in a remarkable performance as a believable psychopath. He never goes over the top and bug-eyed, instead playing Eddie as a tightly wound but always self controlled young man who may get occasionally twitchy and sweaty but always remains nearly emotionless.

A former mental patient who is well aware that things are going wrong in his head again, Eddie does what he can to get himself committed, but no one’s cooperating. In fact seen through Eddie’s eyes, the entire world is simply one slap, one humiliation after another. To some of us anyway, he’s an extremely sympathetic character.

Marie Windsor

Although later in the film the police come to the conclusion that he must be an ex-soldier, we are never given any proof of this apart from his weapon of choice. It doesn’t matter—now he drives a delivery truck for a laundry service. One of the regular customers along his route is attractive young nightclub pianist Jean Darr (Marie Windsor), who appears to be one of the few people, and certainly the only woman, who’s nice to him. So when what he believes to be a seduction turns out to be, well, not only not a seduction but ends with Jean treating him like any other errand boy, he snaps. It’s the only scene in the film in which his face reveals any emotion at all apart from confusion or cold boredom. That night he waits on a rooftop across from the bar where she works and shoots her as she heads home.

Enter the police, which adds another layer onto the external story behind the film. As Det. Kafka (if there is any significance to that name it’s never made clear), Adolphe Menjou, is also playing against future type as a gruff, less than suave, and mostly hapless cop. A few years prior to the film, Menjou was known as one of the fiercest defenders of HUAC in the business, which of course made his pairing with Dmytryk here a potentially disastrous one. By all accounts, however, it was a perfectly amicable working relationship, so much so that Dmytryk would use him again in a few of his subsequent films . But that’s irrelevant, too.

As more seemingly random dark haired young women are being picked off around the city (which in spite of all the location shooting is never identified as San Francisco), the police bring in criminal psychologist Dr. Kent (Richard Kiley) to work out a profile. With precious little evidence, the doctor jumps to the remarkable conclusion that these are in fact sexually motivated shootings. And that leads to the first head-scratching scene of the film.

Taking Dr. Kent’s very broad conclusion at face value, the cops round up every pervert in town for a line-up. Now, given that there have been no witnesses who saw the shooter, a line-up is pointless. Perhaps the cops realize this, which explains why the chief interrogator (sitting at a table in front of an auditorium full of officers) runs the line-up like a routine from an old Bob Hope special, introducing and dismissing the peeping toms, gropers, and rapists with well-prepared one-liners. To a schlub who writes obscene mash notes to strangers he begins, “So, Bob, they say the pen is mightier than the sword...”

It’s an oddball comic scene completely out of step with the rest of the film, and a scene that makes no sense within the context of a serious police drama. It’s darkly funny, yes (especially considering that we’re dealing with convicted sex offenders as the butt of bad jokes), and had the rest of the film been handled in this tone, well, it would have been a very different picture. As it stands it’s merely jarring and leaves viewers wondering what the hell it’s doing there. Personally I can’t recall another cutaway even remotely close to this in any other Dmytryk picture. Logically enough, though, the scene ends with dr. Kent muttering “this is pointless” before leaving the room.

He then goes on to deliver the film’s heavy handed message to the mayor, the press, and the other investigators—namely (and here’s where I wonder if Dmytryk’s prison experience is being reflected) that anyone arrested for a sex crime of any kind should be locked in a psych ward until they’re cured of their personal glitch. And if they aren’t cured, they should be left there locked away for good.

That leads to another delightfully baffling line of dialogue as Kafka orders a teenager with a broken antique rifle be sent to a nearby bughouse. “I don’t wanna be looking for this kid again in a couple years,” Kafka explains, “when he’s got a real gun...or maybe an axe.”

(An axe?)

In spite of a few weirdnesses along the way The Sniper still played like most any boilerplate thriller while at the same time being years ahead of the game both in terms of subject and solution. Extrapolating a bit on Dr. Kent’s recommendation, the kid being sent to the psych ward had not been convicted of a sex crime—he was just acting weird. Likewise, following the latest school shooting the do gooders are once again calling for the psychological incarceration of anyone who thinks differently, acts differently, isn’t like everyone else, as they represent a very tangible future threat. But the answer to this hamfisted solution can also be found in the very same scene. Before being sent to the local Bin, the above-mentioned teen with the broken gun tells Kafka, “You think I’m the only one in town who doesn’t like people? There’s millions of ‘em!” And we’ve been proving him right since 1966. So maybe it’s time we stop talking about locking these people up pre-emptively, and finally come around to accepting the simple fact that mass shootings might well be nothing more than a rational response to an insane world. by Jim Knipfel

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jim Knipfel's thoughtful piece on Ed Wood - the man and his films.

"Okay, so maybe he wasn’t Welles or Kurosawa or David Lean, but I could name hundreds of directors (most still working today) who’ve been given $100 million budgets and turned in films that weren’t nearly as entertaining, fascinating, even thought-provoking as any of Ed Wood’s. Jesus christ, look at Titanic or most any teen vampire picture or some of that crap Jean-Luc Godard was pulling out of his ass in the ‘60s and ‘70s. If you can watch an Ed Wood film and put it out of your head that it’s “An Ed Wood Film,” you might just see what I’m talking about. They really aren’t as bad as all that."

1 note

·

View note

Text

Slackjaw A memoir: the review.

Just reread this the other week for the first time in a decade. There are old-testament-style prophet vibes this man gives off. Like a punk-rock Ezekiel. I enjoyed everything I have read of his though I need to reread the buzzing before I review it. There is a darkness and dangerous honesty to Jim's observations and an honest sense of peace that overwhelms his world even when he is punching out windows. This is more a short endorsement more than an in-depth review. if only because I really should be working on my own writing projects and I am almost certain no one reads or at least takes pleasure from me rambling on my favorite books. but if there is any interest I will expand this and be more specific. Heck, I may do that anyway if the mood strikes. all you really need to know though is Pynchon gave it a kind if not an outright glowing blurb. and all readers at this point in the century should know whether that is enough to give this book a read or not.

#punk#punk aeshtetic#punk rock#industrial#post industrial#jim knipfel#slackjaw#memoir#literature#thomas pynchon#postmodern

0 notes

Text

Streaming on Plex: Best Movies and TV Shows You Can Watch for FREE in September

https://ift.tt/eA8V8J

This article is sponsored by Plex. You can download the Free Plex App now by clicking here!

There’s an overwhelming amount of new movies and TV shows hitting streaming services this fall. If you’re starving for new content, it’s set to be a fantastic time, but if your wallet is starving for funds, it can be pretty stressful. With studios and content providers spreading their libraries out across so many different streaming services, keeping up with all of your favorites can get expensive. Thankfully, Plex TV is here to keep you entertained without breaking the bank.

Plex is a globally available one-stop-shop streaming media service offering thousands of free movies and TV shows and hundreds of free-to-stream live TV channels, from the biggest names in entertainment, including Metro Goldwyn Mayer (MGM), Warner Bros. Domestic Television Distribution, Lionsgate, Legendary, AMC, A+E, Crackle, and Reuters. Plex is the only streaming service that lets users manage their personal media alongside a continuously growing library of free third-party entertainment spanning all genres, interests, and mediums including podcasts, music, and more. With a highly customizable interface and smart recommendations based on the media you enjoy, Plex brings its users the best media experience on the planet from any device, anywhere.

Plex releases brand new and beloved titles to its platform monthly and we’ll be here to help you identify the cream of the crop. View Plex TV now for the best free entertainment streaming and check back each month for Den of Geek Critics’ picks!

cnx.cmd.push(function() { cnx({ playerId: "106e33c0-3911-473c-b599-b1426db57530", }).render("0270c398a82f44f49c23c16122516796"); });

DEN OF GEEK CRITICS’ PICKS

Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles

They’re the world’s most fearsome fightin’ team. They’re heroes in a half-shell and they’re green. I mean, what more do we need to say? 2014’s Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles is no Citizen Kane, but comic book movie fans flock to it like the four titular turtles to pizza. The film knows exactly what it is, providing cheesy one-liners, silly action, and unpretentious fun. Throwing in Will Arnett as a sidekick for April O’Neil was an inspired choice that paid dividends in laughs and whoever tapped Tony Shaloub to voice Splinter should get a pay raise. Produced by Nickelodeon Pictures, Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles wasn’t only the highest grossing film in the series, but also the highest grossing Nickelodeon film of all-time. This reboot of the classic ninja team helped spawn further films, new TV series, and a renewed interest in one of the most beloved comic book properties ever. Cowabunga, dude!

Noah

This isn’t your Sunday School’s Noah. Darren Aronofsky’s adaptation of the story of the biblical figure Noah is an awe-inspiring epic that takes the bones of the famous story and infuses themes about environmentalism, self-doubt, and yes, faith. Pulling liberally from texts like the Book of Enoch, the film has far more action than just leading animals onto a boat and a storm. Shot by Matthew Libatique, the movie looks absolutely gorgeous and at times can be genuinely breath-taking, but it’s not just about the visuals. Russell Crowe stuns in the title role, but the entire ensemble is great, including a post-Potter Emma Watson and a ferocious Ray Winstone. No one expected Noah to be more akin to a thought-provoking art house film than a straight-forward epic, but that’s the sort of genius you get from Aronofsky, one of the most exciting and inventive filmmakers working today.

Shine a Light

Even if we hadn’t just lost the immortal, suave Charlie Watts, the heartbeat of rock and roll’s longest institution, The Rolling Stones, we’d still be recommending Martin Scorsese’s Shine a Light. Capturing the legendary band during their A Bigger Bang Tour in 2006, Scorsese spends a lot of the time rightfully focusing on Watts. With the camera fixated on Watts, you witness his unflappability; the way that he can make such raucous playing look so effortless. You also catch the man’s unique, jazz-influenced technique, like how he rarely hits the center of his snare, or how he changes his grip whenever he hits a cymbal. Even in their old age, the Stones are still one of the tightest, most electrifying live acts, and Shine a Light puts you right on stage with them as they barrel through one of the deepest catalogs in recorded music. It’s simply a masterful concert film.

The Virgin Suicides

Sofia Coppola likely has to deal with accusations about nepotism to this day, but anyone who saw her directorial debut The Virgin Suicides knows that Francis’ daughter would have made it as a filmmaker even without her famous last name. This haunting adaptation of Jeffrey Eugenides’ novel of the same name taps into the melancholy of childhood, the dreamlike haze of memory, and the mystery that lurks inside suburban homes. Coppola expertly captures the pull that an ethereal group of sisters have on the imaginative group of boys that pine for them in a way that is relatable for anyone that had an unrequited crush in high school. As a coming-of-age movie, it is one of a kind. As an exploration of trauma and grief, it is crushingly effective. The original score by the band Air only adds to its hypnagogic vibe.

Rock ‘n’ Roll High School

Punk rock music and Roger Corman pictures are some of the core tenants that Den of Geek was founded on, so of course we’re going to recommend 1979’s Rock ‘n’ Roll High School, which features possibly the coolest band of all-time, The Ramones. Let our resident punk rock movie expert Jim Knipfel break it down for you:

“After producing so many dozens of teen rebellion films over the years, Corman finally hit the pinnacle, the ultimate teen rebellion picture, with the cartoon antics ratcheted up more than a few notches. There are so many bad jokes flying around, so many visual gags and film references packed into every scene, so many overwrought teen film clichés pushed way past absurd, it’s a film that demands multiple viewings. Even if “Riff Randall, rock ’n’ roller” (P.J. Soles) doesn’t look much like any punk chick I ever knew, I’m perfectly willing to accept it. And in historical terms, it really was this film more than the 4 albums they had out at the time that spread the word about The Ramones to mainstream America, and that’s worth something. Old as I am I still get a thrill every time the students and the Ramones blow up Vince Lombardi High, and anyone who doesn’t must be wrong in the head somehow.”

New on Plex in September:

1000 Times Good Night

13

13 Assassins

The Accidental Husband

All Good Things

Assassination of a High School President

Awake

Bent

Bordertown

Brain Dead

Cold Mountain

The Descent

The Descent Part 2

Even Money

Fear City

First Snow

Freedom Writers

Gray Matters

The Jesus Rolls

Johnny Was

Keys to Tulsa

The Legend of Bagger Vance

Mad Money

Marrowbone

Murder on the Orient Express

The Ninth Gate

Nothing but the Truth

Ordinary People

Rememory

Rock ‘n’ Roll High School

Sanctuary

Shine a Light

Soul Survivors

Taboo

Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles

The TV Set

The Virgin Suicides

What Doesn’t Kill You

Winter Passing

World Trade Center

Catch before it leaves in September:

31

Absolution

Accident Man

Aeon Flux

After.Life

Angel of Death

Answer Man

The Bang Bang Club

Battle Royale

Blood and Bone

The Broken

Cashmere Mafia

Child 44

Cleaner

Cold Comes the Night

Coming Soon

The Connection

Conspiracy

The Cookout

Critical Condition

Dark Crimes

The Death and Life of Bobby Z

Death Proof

Dickie Roberts: Former Child Star

Downhill Racer

Dragged Across Concrete

The Dresser

The Duel

Dummy

Flight of Fury

Flirting with Disaster

The Foreigner

Goat

Gutshot Straight

Halloween III: Season of the Witch

The Hard Corps

Hesher

High Right

Honeymoon

The Hunt

I Saw the Devil

In the Mix

Jason and the Argonauts

Jeff, Who Lives at Home

Jiri Dreams of Sushi

Joe

Journey to the West

Kill ‘Em All

A Kind of Murder

The Kite Runner

Lake Placid 2

Lake Placid 3

Last Resort

The Lazarus Project

Misconduct

Mr. Church

Mutant Chronicles

Mythica: The Godslayer

Mythica: The Iron Clown

Never Back Down: No Surrender

News Radio

Noah

Ong Bak: The Thai Warrior

Ong Bak: The Beginning

The Order

Out for a Kill

The Outcasts

Phantoms

Pistol Whipped

The Protector

Pulse (2001)

Reprisal

Return to the Blue Lagoon

The River Murders

The Romantics

Second in Command

Shadow Man

Shattered

The Shepherd

Southside with You

Space Station 76

Square Pegs

Standoff

Starship Troopers 2: Hero of the Federation

Starship Troopers 3: Marauder

Steel Dawn

Substitute

The Super

SWAT: Under Siege

The Terminal

The Three Burials of Melquiades Estrada

Touchy Feely

Trollhunter

UFO

Universal Solider: Day of Reckoning

Vamps

Vicky Cristina Barcelona

Walking Tall: Lone Justice

Warlock

What Planet are You From?

World’s Fastest Indian

World’s Greatest Dad

The Yellow Handkerchief

Still streaming on Plex:

2:22

2 Days in New York

21 Jump Street

22 Bullets

24 Hours to Live

3rd Rock from the Sun

6 Bullets

99 Homes

A Little Bit of Heaven

A Walk in the Woods

The Air I Breathe

Alan Partridge

ALF

Alone in the Dark

Amelie

American Pastoral

And Soon the Darkness

Andromeda

Are You Here

Arthur and the Invisibles

Awake

Battle in Seattle

Bernie

Better Watch Out

Black Death

Blade of the Immortal

Blitz

The Brass Teapot

Bronson

The Brothers Bloom

The Burning Plain

But I’m a Cheerleader

Cake

Candy

Catch .44

Cell

The Choice

Clerks II

Coherence

The Collector

Colonia

Congo

Cooties

The Core

The Cotton Club

Crossing Lines

Croupier

Cube

Cube 2

Cube Zero

Cyrano de Bergerac

Death and the Maiden

The Deep Blue Sea

Deep Red

Derailed

Detachment

The Devil’s Rejects

Diary of the Dead

District B13

DOA: Dead or Alive

Dr. T and the Women

Eden Lake

The Edge of Love

The post Streaming on Plex: Best Movies and TV Shows You Can Watch for FREE in September appeared first on Den of Geek.

from Den of Geek https://ift.tt/3DV4bW5

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Click here & you'll find comics, illustrations, clowns, pranks, zip-a-tone & every other zany thing you'd expect to see in a @believermag Q&A starring me & my old pal (& fellow NYPress alum) Jim "Slackjaw” Knipfel. https://believermag.com/logger/an-interview-with-danny-hellman/ #comics #illustration #illustrator (at Park Slope Historic District) https://www.instagram.com/p/B9-Q9fyj-_T/?igshid=lq02fb3pphzj

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Another one??

Rules+ Answer the 20 questions and tag 20 amazing followers you’d like to get to know better

OMG thanks so much @letstrysomefanfic cause I love answering/ reading these!!!! Love ya!!

Name: Allegra

nicknames: Leggy

zodiac sign: Sag.

height: 5′3 3/4

orientation: Pan(cake)

nationality: American

favourite fruit: Apples

favourite season: summer cause I can focus on what I love to do.

favourite book: Slackjaw by Jim Knipfel

favourite flower: My venus flytrap with googly eyes named Gerard. He died while I was away at camp though.....

favourite scent: coffee, vanilla, baking bread, (VERY subtle sweet ones? also literally anything to do with food lmao) Same answer as @letstrysomefanfic but some more that I like, the ocean, the earthy smell after rain, smoke.

favourite colour: don’t have one

favourite animal: dogs and blackbirds and anything that lives in the ocean

coffee | tea | hot cocoa: All three it really depends on my mood.

average sleep hours: wtf is sleep anywhere from 0- my personal record of 16 hours

cat or dog person: Both

favourite fictional character: omg don’t make me decide amongst my children please

number of blankets you sleep with: like 5 some really thin and others are like, hot damn

dream trip: anywhere with friends and an ocean

blog created: I think two or three years ago I really don’t remember.

number of followers: 207 and I love everyone!

random fact: I’m a Sucker for the ocean and space, I could talk about either all day.

and now i dub thee: (like @letstrysomefanfic, i’m only tagging 10 people cuz 20 is a lot hot damn)

@ninjanessie @sgt-pineyapple @marvelous-imagining @badwolfgirlatbakerst @lesbeanflowers @ladyraven210 @the-bucky-one @manyfandomstohandle @nedandpeter @ohparkers

9 notes

·

View notes

Quote

If we don’t change direction soon, we’ll end up where we’re going.

Irwin Corey, ‘foremost authority’, has passed away at 102.

My favorite Corey story: The author Thomas Pynchon sent Cory in his place to accept the National Book Award in 1974 for Gravity’s Rainbow:

Jim Knipfel, Who Am the World’s Foremost Authority?

So, after being mis-introduced (as 'Robert Corey’), the little man with the wild hair and the rumpled suit walked to the podium and addressed some of the most esteemed figures in American publishing and literature:

'However…I accept this financial stipulation–ah–stipend in behalf of Richard Python for the great contribution which to quote from some of the missiles which he has contributed… Today we must all be aware that protocol takes precedence over procedure. However you say–WHAT THE–what does this mean…in relation to the tabulation whereby we must once again realize that the great fiction story is now being rehearsed before our very eyes, in the Nixon administration…indicating that only an American writer can receive…the award for fiction, unlike Solzinitski whose fiction does not hold water.

Comrades–friends, we are gathered here not only to accept in behalf of one recluse–one who has found that the world in itself which seems to be a time not of the toad–to quote Studs TurKAL. And many people ask ‘Who are Studs TurKAL?’ It’s not ‘Who are Studs TurKAL?’ it’s ‘Who AM Studs TurKAL?’…’

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

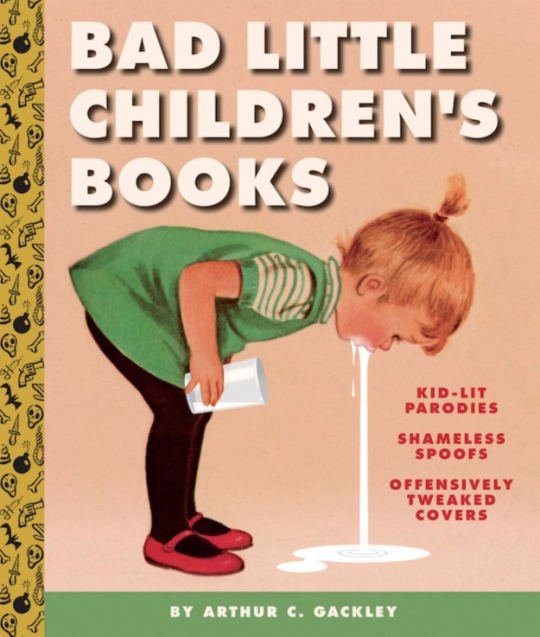

Who Will Think of the Children?

Jim Knipfel on Satire and Children’s Books

This past September, the Abrams’ imprint Image, which specializes in illustrated and reference works, published a novelty book entitled Bad Little Children’s Books by the pseudonymous Arthur Gackley. The small hardcover, which itself quite deliberately resembled a little golden book, featured carefully-rendered and patently offensive parodies of classic children's book covers. Instead of happy, apple-cheeked tykes doing pleasant wholesome things, Gackley’s covers featured kids farting, puking, and using drugs. Others included children with dildoes and racially inflammatory portrayals of Middle Eastern, Asian, and Native American youngsters. The book was clearly labeled a work of satire aimed at adults, and adults with a certain tolerance for bad taste and crass jokes.

Upon its initial release it received positive reviews and sold fairly well. Then in early December, a former librarian named Kelly Jensen posted an entry on Bookriot entitled “It’s Not Funny. It’s Racist.”

“This kind of 'humor' is never acceptable,” Ms. Jensen wrote. “It’s deadly.”

Jensen’s rant circulated quickly across social media, and Abrams suddenly found itself besieged by attacks from the outraged and offended, who assailed Gackley for creating the book in the first place, and the Abrams editorial board for agreeing to publish it.

“There is a difference between ‘hate speech’ and free speech,” one outraged member of the kidlit comunity wrote on Facebook. “In the same way, you cannot yell ‘Fire!’ in a crowded theater just because you feel like it. This book was in very bad, insulting, racist taste, and designed to look like a children's book. How is that a good idea? Children are too young to understand this as parody. If it's for adults, why is that even funny? Oh, I guess if you are a racist you would think it's funny.”

Another tweeted, “Sounds like something that should've been completely ignored and removed before it hit the shelves. Just because we have the freedom of speech, it can be taken way too far.”

Still another confused and enervated soul wrote, “Argue all that you want, but this particular book was for children yes? Or no? If it was, does that mean we should allow and subject young children to gratuitous violence, gore and pornography? And what age is it acceptable? Does this mean we have to start putting PG-14 on printed material and make it mandatory because certain writers can't conduct themselves with a moral scale?”

Another angry reader summed it up quite simply by posting, “Freedom is bullshit, literally.”

[Note: As much as possible, the spelling, punctuation and grammatical errors which peppered the above posts have been corrected here for the sake of simple comprehensibility.]

Although Abrams initially stood by Gackley and the First Amendment right to offend, and had received the public support of several anti-censorship organizations, by December tenth the noise had simply grown too shrill. Mr. Gackley, maintaining to the end his intentions had been grossly misinterpreted, admitted there was no way to salvage things, and asked that Abrams not reprint the book. In a statement, Abrams announced they would be complying with his wishes. Although Bad Little Children’s Books was not banned in any official capacity, it had all but completely vanished from online booksellers within a few days after the announcement. Used copies, while available, are now selling for outrageous prices.

At the same time that this was happening, there were also calls to ban the (real) children’s books When We Was Fierce and A Birthday Cake for George Washington. The invented slang used in the former was interpreted as racist by some parent groups, and the latter was attacked for its historically inaccurate portrayal of the daily lives of slaves on Washington’s estate. Meanwhile, a mother in Tennessee led the call to pull Rebecca Skloot’s The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks from the local school system. The New York Times bestselling biography, which concerned a Baltimore woman whose massive cervical tumor had become the invaluable source of several generations worth of cell lines used by cancer researchers, was being taught in local high schools as a means of educating students both about cancer and about racial issues within the medical community. The Tennessee mother calling for its removal, however, found the book pornographic.

Point being, I guess, that certain sectors of the population harbor an insatiable, even desperate desire to be shocked and offended by something they’ve read, seen, or even heard about, and the drive to ban these things (made much easier with the advent of social media) will likely always be with us. But back to the Gackley for a moment. Reading through the enraged postings aimed at Abrams, a number of the offended make the point that they are not attempting to censor, but are merely exercising their own First Amendment right to criticize. That’s fine and understandable. But the crux of the matter is that these people would be much happier if the book never existed in the first place, and considered Abrams’ decision a glorious victory for their cause.

Let’s try to put it in some sort of semi-comprehensible historical context. Dark and occasionally tasteless adult-oriented satires of children’s books, television and toys have been with us about as long as media aimed specifically at the innocent set. We just can’t help ourselves. Present us with the doe-eyed lukewarm treacle of the Smurfs or Care Bears, and some of us will instinctively reach for a baseball bat. In the case of Bad Little Children’s Books, the outrage in many instances seems to be sparked less by the content than form, and the fear that the book might actually be mistaken for legitimate kidlit. So here are a handful of similar cases from the last half-century. While reactions and results differ wildly, a certain historical pattern does seem to emerge.

Ralph Bakshi’s 1972 animated feature Fritz the Cat, based on the R. Crumb character, became notorious overnight for being the first theatrically-released cartoon to receive an X rating from the MPAA. What people tend to forget is that the film received the distinction not on account of its sexual content, nor because it included characters who were overtly racist, misogynistic drug addicts who cursed a lot. The real problem was the film featured cute and fuzzy animals who were racist, misogynistic drug addicts who cursed a lot, and had sex. The MPAA board was afraid people would see the cartoon poster and stroll into the theater, family in tow, expecting the latest Disney opus. By modern standards the film should have received nothing more than an R rating, but the damning “adults only” designation was an effort to avoid any confusion. It didn’t matter. People saw the X rating and immediately concluded Bakshi had made a hardcore cartoon in a diabolical effort to corrupt the nation’s youth. Although the publicity attracted large audiences and earned the film an undeniable bit of underground cred, that same publicity did irreparable damage to Bakshi’s career. For decades afterward, even while trying to redeem himself with the family-friendly Mighty Mouse cartoon series for TV, he found himself labeled a racist, sexist pornographer determined to get America’s young people hooked on heroin—charges leveled at him mostly by people who had never seen Fritz the Cat.

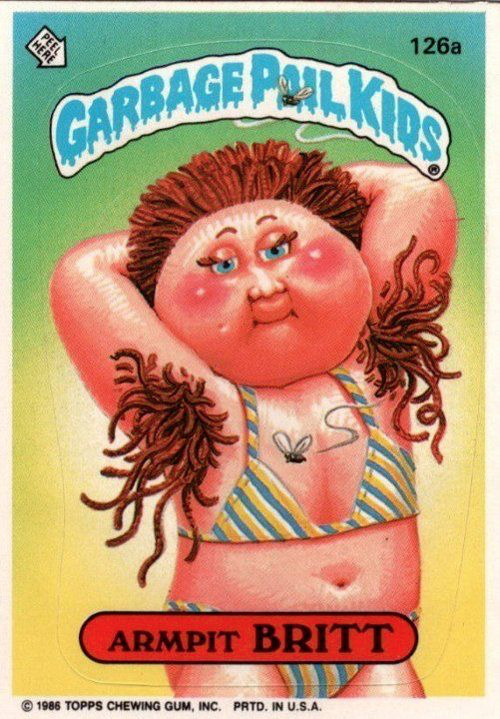

Long before he won a Pulitzer for Maus and became a regular contributor to The New Yorker, cartoonist Art Spiegelman spent twenty years working for the Topps trading card company. Among other things, he was one of the primary creative forces behind Topps' wildly popular and wickedly subversive Wacky Packages series, which satirized American consumer products. In 1985, Topps attempted to arrange a licensing deal to release a series of trading cards based on Cabbage Patch Dolls, which were all the rage at the time. Finding licensing fees had already gone through the roof, they decided instead to release a Wacky Packages-style parody. As it happened, an unreleased Wacky Packages design called Garbage Pail Kids was already on the boards, so they ran with it.

Spiegelman and the involved artists took the basic design of the cuddly and adorable plush dolls beloved by all the world and twisted them into deranged monstrosities covered in snot, vomit, oozing sores and bugs. From the moment they hit convenience store checkout counters, the GPK stickers were outrageously popular. Although some school systems banned them as an unwelcome distraction and more than a few parents were mortified and disgusted that any sick individual would do such a horrible thing to something so innocent and cuddly, there was no organized grassroots effort to censor the stickers on moral grounds. Topps' only real trouble came in the form of a copyright infringement suit filed by the Cabbage Patch Dolls’ creators, Original Appalachian Artworks, Inc.

Topps’ argument that what they were doing was clear and obvious parody (and therefore protected under the First Amendment) didn’t quite cut it. The suit was settled out of court, with Topps agreeing to alter the Garbage Pail Kids logo and basic character design so as to avoid any possible confusion with the original dolls. The stickers continued to come out, and went on to inspire an animated television series, a feature film, a book and an unholy array of merchandise ranging from trash cans to sunglasses. In the end, it could easily be argued that over time the Garbage Pail Kids had more of a lasting impact on the culture than their inspiration.

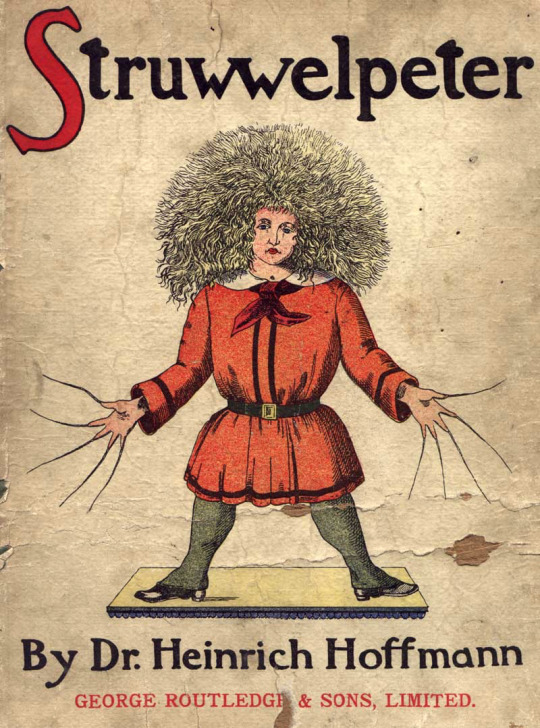

Struwwelpeter was first published in Germany in 1845. The cautionary and terrifying collection of nursery rhymes (with graphic accompanying illustrations to drive the point home) warned children that if they sucked their thumnbs, didn’t eat their dinner, didn’t clean themselves up properly, mistreated their pets or threw tantrums, a horrible fate awaited them. The book became a standard instructional volume in most German households with young children. In 1898, a similar but decidedly British version was released in England under the title Shockheaded Peter, and was nearly as popular. Nobody it seemed thought much about presenting naughty children with images of potential disfigurement or death. The book helped keep the little buggers in line.

In 1999, American indie publisher Feral House released a gorgeous new edition of Struwwelpeter, complete with new illustrations, interpretive and historical essays, and assorted bowdlerized and satirical versions of the nursery rhymes which had appeared over the years. Feral House, which had always prided itself on publishing dangerous and controversial works, soon found this simple history and analysis of a once popular if disturbing children’s book could be just as troublesome as their books by notorious British serial killer Ian Brady or the Church of Satan’s Anton LaVey.

“Yes, we had minor trouble with Struwwelpeter,” says Feral House founder and publisher Adam Parfrey. “But most of that was put to rest when bookstores simply refused to carry the book. I guess 21st century Americans are more touchy than the Germans of yore. For a while, a couple chains and many independent bookstores stopped carrying the Anton LaVey books we published after Geraldo Rivera put on those sensationalist programs about Satanism... I credit Marilyn Manson for putting an end to that crap. After he spoke out about it, so many people went into bookstores to order them that the stores saw best to get them back into their shops. Time passed, and the crazy ideas receded.”

Parfrey also sees a potential connection between the backlash Abrams suffered over Bad Little Children’s Books and the present brouhaha over what has been termed “fake news.”

“Right now there’s a good bit of madness going on with Trump-loving crazies, including Alex Jones and Infowars building up this idea that Hillary Clinton and John Podesta are torturing and killing children…and they’re pointing at Marina Abramović, too. That’s a big deal on Facebook at this instant. And anyone who poo-poos this story is being accused of covering up kiddie killing. I can see how this sort of madness can amplify into the book trade, a situation where parodies are mistaken for outright kiddie torture. Sad, isn’t it?”

As a final example, in 2010 Simon and Schuster published my book These Children Who Come at You With Knives, a collection of darkly comic fairy tales aimed at adults. Across roughly a dozen stories written in traditional fairy tale formats (though with more cursing, gratuitous gore, and uncontrolled bodily functions), assorted anthropomorphized animals, magical creatures, human children, the elderly and the dull-witted come to various terrible ends. The book received decent reviews and publicity, but there was no outcry, no controversy, and no one insisted the book be banned in order to protect the innocent. Meaning, of course, that I didn’t sell millions as a result of the hoo-hah. Christ, I’ve even heard from people who use them as bedtime stories for their own kids. Dammit! What the hell did I do wrong?

I think I made two deadly mistakes. First, despite my best efforts to the contrary, my publisher decided to release the book without illustrations, meaning it could never possibly be confused with an actual children’s book. More devastating still, I was cursed with bad timing. These Children Who Come at You With Knives was released halfway through President Obama’s first term, and while there was certainly a good deal of rancor in the air, satire was still a viable form and accepted as such, at least among the literate.

In different eras and in different ways, all the above examples were damned by a public inflicting its own preconceived notions upon works of obvious satire, insisting they be what the public believed them to be instead of what they actually were.

By the time Bad little Children’s Books was released, the world had become too ridiculous, too absurd, and as a result we lost our sense of humor. There was simply no longer any way to lampoon our chosen leaders or our own insecurities, with the world itself poised and ready to top us at every turn. In short, the book’s publication coincided with the precise moment satire breathed its last, meaning readers had no choice but to take Gackley’s work, as Parfrey points out, at face value. Lucky bastard.

Jim Knipfel is the author of Slackjaw, These Children Who Come at You with Knives, The Blow-Off, and several other books, most recently Residue (Red Hen Press, 2015). his work has appeared in New York Press, the Wall Street Journal, the Village Voice and dozens of other publications.

18 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Kolchak: The Night Stalker - The Genealogy of a Classic Horror TV Series Jim Knipfel, denofgeek.com

Kolchak: The Night Stalker was a classic piece of horror television. Remember when reporters were viewed as heroes? • facebook • twitter • google+ • tumblr Feature Jim Knipfel Kolchak: The Night StalkerOct 12, 201731 Days of…

"Kolchak: The Night Stalker" was a classic piece of horror TV. Remember when reporters were viewed as heroes?

0 notes

Text

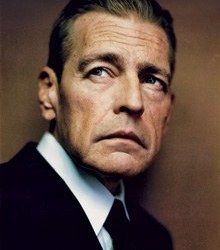

Nick Tosches’ Final Interview

On Sunday, October 20th, 2019, three days before his seventieth birthday, Nick Tosches died in his TriBeCa apartment. As of this writing, no cause of death has been specified. It represents an Immeasurable loss to the world of literature. The below, conducted this past July, was the last full interview Tosches ever gave.

***

In Where Dead Voices Gather, his peripatetic 2001 anti-biography of minstrel singer Emmett Miller, Nick Tosches wrote: “The deeper we seek, the more we descend from knowledge to mystery, which is the only place where true wisdom abides.” It’s an apt summation of Tosches’ own life and work.

Journalist, poet, novelist, biographer and historian Nick Tosches has been called the last of our literary outlaws, thanks in part to his reputation as a hardboiled character with a history of personal excesses. But he’s far more than that—he’s one of those writers other writers wish they could be. He’s seen it all first-hand, moved in some of the most dangerous circles on earth, and is blessed with the genius to put it down with a sharp elegance that’s earned him a seat in the Pantheon.

Born in 1949, Tosches was raised in the working class neighborhoods of Newark and Jersey City, where his father ran a bar. Despite barely finishing high school, he fell into the writing game at nineteen, shortly after relocating to New York. He quickly earned a reputation as a brilliant music journalist, writing for Rolling Stone and authoring Country: The Twisted Roots of Rock ’N Roll (1977), the Jerry Lee Lewis biography Hellfire (1982) and Unsung Heroes of Rock ’N Roll (1984). After that he staked out his own territory, exploring and illuminating the deeply-shadowed corners of the culture and the human spirit. He’s written biographies of sinister Italian financier Michele Sindona, Sonny Liston, Dean Martin and near-mythical crime boss Arnold Rothstein. He’s published poetry and books about opium. His debut novel, Cut Numbers (1988) focused on the numbers racket, and his most recent, Under Tiberius (2015) presented Jesus as a con artist with a good p.r. man.

While often citing Faulkner, Charles Olsen, Dante and the Greeks as his primary literary influences, over the past fifty years Tosches’ own style has evolved from the flash and swagger of his early music writing into a singular and inimitable prose which blends the two-fisted nihilism of the crime pulps with an elegant and lyrical formalism. Like Joyce, Tosches takes clear joy in the measured, poetic flow of language, and like Dostoevsky, his writing, regardless of the topic at hand, wrestles with the Big Issues: Good and Evil, Truth and Falsehood, the Sacred and the Profane, and our pathetic place in a universe gone mad.

For years now, Tosches’ official bio has stated he “lives in what used to be New York.” It only makes sense then that we would meet amid the tangled web of tiny sidestreets that make up SoHo at what remains one of the last bars in New York where we could smoke. Tosches, now sixty-nine, smoked a cigar and drank a bottle of forty-year-old tawny port as we discussed his work, publishing, religion, the Internet, this godforsaken city, fear, and how a confirmed heretic goes about obtaining Vatican credentials.

Jim Knipfel: When I initially contacted you about an interview last year, my first question was going to be about retirement. You’d been hinting for awhile, at least since Me and the Devil in 2012, that you planned to retire from writing at sixty-five. And since Under Tiberius came out, there’d been silence. But shortly after I got in touch, we had to put things on hold because you’d started working on a new project. As you put it then, “I find myself becoming lost again in the cursed woods of words and writing.”

Nick Tosches: It is unlike any other project. I am indulging myself, knowing nobody has paid me money up front. Is it a project? Yeah, I guess anything that’s not come to a recognizable fruition is a project. So yeah. I do consider the actual writing of books to be behind me.

JK: Did thinking about retirement have anything to do with what we’ll generously call the dispiriting nature of contemporary publishing?

NT: Oh, very much so. Very much.

JK: There’s a remarkable section in the middle of In The Hand of Dante, it just comes out of nowhere, in which you launch into this frontal attack on what’s become of the industry. I went back and read it again last week, and it’s so beautiful and so perfect, and as I was reading I couldn’t help but think, “Who the hell else could get away with this?” Dropping a very personal screed like that in the middle of a novel? And a novel released by a major publisher, in this case Little, Brown. Was there any kind of reaction from your editor?

NT: Okay, is this the same passage where I talk about all these people with fat asses?

JK: Yeah, that’s part of it.

NT: Okay, my agent at the time, Russ Galen, said he heard from {Michael} Pietsch, the editor who’s now the Chief Executive Officer of North America. And the moment he became so, he went from being my lifelong friend to “yeah, I heard of him.” He complained about the fat ass comment, and my agent told him, “If you go for a walk with Nick Tosches, you might get rained on.” Apart from that, no. And I have to say, he considers that one of his favorite novels, ever. When I tried to get the rights back because of a movie deal, he said “no I won’t do that.” I said “Why?” And he said because it was one of his favorite books. So no, there was no real backlash. A lot of comments like your own. A lot of people saying “Boy, that was great.”

JK: As we both know, marketing departments make all the editorial decisions at publishing houses nowadays, and over the years you must have driven them nuts. There’s no easy label to slap on you. You hear there’s a new Nick Tosches book coming out, it could be a novel, it could be poetry, it could be a biography or history or anything at all. I’m trying to imagine all these marketing people sitting around asking, “So what’s our targeted demographic for The Last Opium Den?”

NT: I just set out to do what I wanted to do. If they wanted to cling to the delusion that they could somehow control sales or predict the future of taste, fine, let them go ahead and do it. I’ve always found it’s the books that gather the attention, they just try to coordinate things. All they’re doing is covering their own jobs. If they can wrangle you an interview with Modern Farming, well, there’s something to put on a list they hand out at one of their meetings… They’re all illiterate. Thirty years ago there was still a sense of independence among publishers. Now they’re just vestigial remnants that mean nothing because they’re all owned by these huge media conglomerates.

JK: To whom publishing is irrelevant.

NT: Right. It’s all just a joke.

JK: I guess what matters is that the people who read you will read whatever you put out. If you put out a book of cake decorating tips, I’d be the first in line to buy it. Actually I’d love to see what you could do with Nick’s Best Cakes Ever, right? It’s something to consider.

NT: Maybe not that particular instance, but what you have so kindly referred to as my current project, which is very…eccentric. It’s the herd of my obsessions that will not remain corralled as I intended.

JK: What brought you back to writing? You’ve said in the past that writing is a very tough habit to kick.

NT: Well, what brought me back? I have no idea. Maybe just actual, utter, desperate boredom. There was none of this Romantic need to express myself. Just a lot of little obsessions, that’s all. As I said…well, I didn’t say this at all. There’s nothing at stake. There’s no money, there’s not going to be any money. There’s no one I need to give a second thought of offending or pleasing. But that having been said, I’m taking as much care with it as I have with everything else. I’ve always thought of myself as the only editor. And having had the good fortune to work with good titular editors, which means their job consists of perhaps making a suggestion or stating a preference or notifying me that they do not understand certain things, and beyond that leaving it be. As I told one editor,I forget when or where or why, “Why don’t you go write you’re own fuckin’ book and leave mine be?” He had all these great ideas. The best editors are the ones that aren’t frustrated authors.

JK: I was lucky enough to work with two editors like that. One had a nervous breakdown and is out of the business, the other just vanished one day.

NT: Well, you’re fortunate. Not only do most editors, a majority of editors, which are bad editors, like the majority of anything, really. If they don’t interfere with something, and nine times out of ten make it worse, they’re not justifying their jobs. The other thing is, we’re recently at the point where the new type of writers, which are the writers who are willing to do it for free, think the editor’s the chief mark of the whole racket. But it’s not—he’s not, she’s not. Their job is to get you paid and leave you alone. That’s the thing. Now you got pseudo editors, pseudo writers. If you think of a writer such as William Faulkner. Now there’s a guy who just screamed out to be edited. Fortunately the editors were willing to publish him and leave him alone, which is why we have William Faulkner. That was the editor’s great contribution, protecting William Faulkner from that nonsense. People speak about, what’s that phrase applied to Maxwell Perkins? “Editor of Genius.” Well, the genius was you find someone who can write really well, and don’t fuck with ‘em. There’s something to be said about that. It’s to Perkins’ credit.

JK: If I can step back a ways to your early years. You were a streetwise kid who grew up in Jersey City and Newark. Your father discouraged you from reading, but you read anyway. So what was the attraction to books? Or was it simple contrariness on your part because you’d been told to avoid them?

NT: I got lost in them. It was dope before I copped dope. I used to love to drift away, in my mind, my imagination. I loved books. My father was not an anti-book person, but he was the first generation of our family to be born in this country. A working class neighborhood where okay, this guy worked in this factory, and that guy owned a bar, and that guy delivered the mail. Nobody was going any further than this. And I remember my father saying, “These books are gonna put ideas in your head.” I guess I enjoyed that they did. Terrible books, some of them. Terrible books, but it didn’t matter.

JK: You’ve also said that very early on you wanted to be a writer.

NT: Yes.

JK: Or a farmer.

NT: Or a garbage man or an archaeologist. Those were my childhood aspirations.

JK: Considering the environment you were coming out of, three of those seem counterintuitive.

NT: Garbage men got to ride on the side of the truck, and that looked great. Archaeologists, wow. I didn’t know they were spending years just coming up with little splintered shards of urns. Yeah, writer. Writing had a great attraction for me, because writing seemed a great coward’s way out. You can communicate anything while facing a corner, with no one seeing you, no one hearing you, you didn’t have to look anyone in the eye. It’s a great coward’s form of expressing yourself. That coupled with the fact that what I felt a need to express was inchoate. I didn’t even understand what it was I wanted to express. Sometimes I still don’t.

JK: You’ve also said that in your teens you started to listen to country music, which given the time and place also seems counterintuitive.

NT: Did I say my teens? Maybe I was nineteen or twenty. Yeah, I never listened to country music until the jukebox at the place on Park Avenue and West Side Avenue in Jersey City.

JK: It was right around that time, when you were nineteen, twenty, that you published your first story in the music magazine Fusion. Which means we’re right around the fiftieth anniversary of your start in this racket.

NT: Let’s see…that was 1969, so yeah, I guess so. Fifty years ago.

JK: Then for the next fifteen-plus years you wrote mainly about music. You were at Rolling Stone and other magazines, and you put out Country, Hellfire and Unsung Heroes of Rock ’n Roll. So How early on were you thinking about branching out? About writing about the mob, or the Vatican, or anything else that interested you?

NT: Before I ever wrote anything. You have to understand, these so-called rock’n’roll magazines provided two great things. First as an outlet for young writers whose phone calls to The New Yorker would not be accepted. And they all, back then before they caught the capitalist disease, offered complete freedom of speech. So yes, in the course of writing about music you could…or actually, forget about writing about music, because nobody even knew anything about music. We were just fucking around.

JK: I remember an early piece you did for Rolling Stone back in 1971. It was a review of Black Sabbath’s Paranoid album, but all it was was a description of a blasphemous Satanic orgy straight out of De Sade.

NT: Yeah, I remember that one.

JK: It was pretty amazing, and even that early, your writing was several steps beyond everything else that was happening at the time. But from an outsider’s perspective, your first big step away from music journalism was actually a huge fucking leap, and a potentially deadly one. So how do you go from Unsung Heroes of Rock ’N Roll to Power on Earth, about Italian financier Michele Sindona?

NT: After Hellfire, someone wanted to pay me a lot of money to write another biography. But I realized there was absolutely no one on the face of the earth whom I found interesting enough to write about other than Jerry Lee Lewis. I’d caught sort of a glimpse of Sindona on television. My friend Judith suggested “Why don’t you write about him?” But how am I gonna get in touch with a guy like that? And she said I should write him a letter.

JK: He was in prison at that point?

NT: Yes, he was in prison the entire time I knew him, until his death. He died before the book was published. I met him in prison here in New York, then they shipped him back to Italy to be imprisoned, and I went over there.

JK: You were dealing with The Vatican, the mob, and the shadowy world of international high finance. Were there moments while you were working on the book when you found yourself thinking, “What the fuck have I gotten myself into?”

NT: Well, yes, because the story was too immense and too complicated to be told.

JK: Something I’ve always been curious about. Publishing house libel lawyers have been the bane of my existence. Whenever I write non-fiction, they set upon the manuscript like jackals, tearing it apart line-by-line in search of anything that anyone anywhere might conceivably consider suing over. And I wasn’t writing about the likes of Jerry Lee Lewis, Dean Martin, or Michele Sindona.

NT: “Conceivably” is the key word in this country, where anyone can sue anyone without punitive repercussions. That’s the key phrase. What these libel lawyers are also doing above all else is protecting their own jobs.

JK: Were you forced to cut a lot of material for legal reasons?

NT: Yes, including proven, irrefutable facts. So yes I did. And it’s not because it was libelous, but because it was subject to being accused of being libelous. It’s a shame. Some of the things were just outrageous. I once threw a fictive element into a description that involved a black dog. “Well, how do you know there was a black dog there?” I said there probably wasn’t, that it was just creating a mood. “Well, we gotta cut that out.” So what’s offensive about a black dog? It sets a precedent. Misrepresentative facts? Morality? I don’t know. These guys.

JK: I don’t know if this was the case with you as well, but I found out I could write exactly the same thing, and just as honestly, but if I called it a novel instead of nom-fiction. They didn’t touch a word. Didn’t even want to look at it. As it happens, your first novel, Cut Numbers, came out next. Had that been written before Power on Earth?

NT: Let me think for a moment…Well, the order in which my books were published is the order in which they were written. The only putative exception may be Where Dead Voices Gather, because that was written over a span of years with no intention of it being a book. So yeah, Cut Numbers. What year was that?

JK: I think that was 1988. I love that novel. There’s a 1948 John Garfield picture about the numbers racket, Force of Evil.

NT: Yeah, I’ve seen that.

JK: But of course they had to glamorize it, because it was Hollywood and it was John Garfield.

NT: I like John Garfield. Terrible movies, but a great actor.

JK: What I love about Cut Numbers is that it’s so un-glamorous. It’s not The Godfather. It’s very street-level. And I’ve always had the sense it was very autobiographical.

NT: I’ve never written anything that wasn’t autobiographical in some way, shape or form. The world in which Cut Numbers is set was my auto-biographical world. “Auto,” self and “bio,” life. My auto-biographical world. The world I lived in and the world I knew. It’s a world that no longer exists. Like every other aspect of the world I once knew. Except taxes. Which I found is a really great upside to having no income. I’m serious.

JK: Oh. I know all too well.

NT: I mean, but It comes with “Jeeze, I wish I could afford another case of this tawny port.”

JK: A few years later, after Dino, you released your second novel, Trinities. While Cut Numbers took place on a very small scale. Trinities was epic—the story spans the globe and pulls in the mob, the Vatican, high finance. You crammed an awful lot of material in there. It almost feels like a culmination.

NT: I wanted to capture the whole sweep of that vanishing, dying world. It was written during a dark period of my life, and I was drawn to a beautifully profound but unanswerable question, which had first been voiced by a Chinese philosopher—sounds like a joke but it’s true: “What if what man believes is good, God believes is evil?” Or vice versa. And we can go from there, the whole mythology, the concept of the need for God. To what extend is our idea of evil just a device? We don’t want anybody to fuck our wives. So God says thou shalt not covet thy neighbor’s wife. We don’t want to be killed, so thou shalt not kill. It’s a bunch of “don’t do this, because I don’t want to suffer that.” I don’t want to get robbed. I dunno, what the hell. Yeah, this has something to do with Trinities, and I somehow knew as I wrote Trinities I was saying goodbye to a whole world, not because I was leaving it. It was basically half memory, as opposed to present day reality.

JK: I remember when I first read it, recognizing so many locales and situations and characters. At least from the New York scenes. That was right at the cusp, when all these things began disappearing.

NT: Yes, and now it has to such an extent that I walk past all these locales, and it’s a walk among the ghosts. That was a club, now it’s a Korean laundry. This was another place I used to go, now it’s Tibetan handicrafts.

JK: I don’t even recognize the Village anymore. I used to work in the Puck Building at Lafayette and Houston. Landmark building, right? It’s since been gutted completely and turned into some kind of high-end fashion store.

NT: Yeah, it’s all dead.

JK: Now, when Trinities was released, I was astonished to see the publisher was marketing it like a mainstream pop thriller. You even got the mass market paperback with the embossed cover treatment. I love the idea of some middle management type on his way to a convention in Scranton picking it up at the airport thinking he was getting something like Robert Ludlum,, and diving headlong into, well, you.

NT: I can explain why all that was. It was volume. It was the same publisher as Dino. They were happy with Dino. Dino was a great success. I think that was 1992, because that was when my father died. This is now, what, 2019? There has not been a single day where that book has not sold. Not that I could buy a bottle of tawny port with it. So whereas with Cut Numbers I was paid a small amount and eagerly accepted it. Eagerly. In fact it’s one of the few times I told the editor, ran into him at a bar, and said all I want is this, and he said “Nah, that’s not enough, we’ll pay you twice that.” Then Dino was double that. And look, I really want to do this book Trinities and be paid a small fortune for it. They had to say yes. They had to believe this was going to be the next, I dunno. Yeah, mainstream. Most of these things are ancillary and coincidental to the actual writing.

JK: There were a lot of strings dangling at the end of the novel, and I remember reading rumors you were working on a sequel. You don’t seem much the sequel type. So was there any truth to that?

NT: Not that I was aware of. I’m sure that if they’d come back and said, “Well, we pulled it off,” and offered twice that, there would’ve been a sequel. Because I loved that book, so if they were going to offer me more to write more, I would have. I hated saying good bye to that world and the past.

JK: Maybe you’ve noticed this, but the people who read you often tend to make a very sharp distinction between your fiction and your non-fiction, which never made a lot of sense to me. To me they’re a continuum, and any line dividing them is a very porous, fuzzy one. Do you approach them in different ways?

NT: Oh, god. Do I approach them differently? Yes. In a way, I approach the fiction with a sense of unbounded freedom. But parallel to that, that blank page is scarier knowing that there is not a single datum you can place on it that will gain or achieve balance. With non-fiction, I am constrained by truth to a certain extent. That’s also true in fiction. They just use different forms of writing. There are poems that have more cuttingly diligent actuality than most history works. It comes down to wielding words. Tools being appointed with different weights and cutting edges and colors. Words, beautiful words. Without the words, no writing in prose is gonna be worth a damn. Used to be, I get in a cab, and back then cab drivers were from New York, and they’d ask me what I did. Now I don’t think they really know what city they’re in. They know it’s not Bangladesh. But if I told them what I did, it was always, “Oh, I could write a book.” Yeah, you’re gonna write a book. Your life is interesting. So what’re you gonna write about? Great tippers, great fares? Become a reader first. Read the Greeks sometime. I decided next time a cab driver asks me what I do for a living. I’m gonna tell him I’m a plumber. “Oh, my brother-in-law’s a plumber!”

JK: As varied as your published works are, there are two I’ve always been curious about. Two complete anomalies. The first was the Hall and Oates book, Dangerous Dances, which always struck me—and correct me if I’m wromg—as the result of a whopping check for services rendered. And the other. From thirty years later, is Johnny’s First Cigarette. Which is, what would you call it? A children’s book? A young adult book?

NT: Right. Of course they’re many years apart. Okay, Hall and Oates, Dangerous Dances. I knew a woman who was what you’d call a book packager. I owed money to the government. Tommy Mottola, who was at the time the manager of Hall and Oates, wanted a Hall and Oates book. She asked me if I wanted to do it, and I said yeah, but it’s gonna cost this much. And Tommy Mottola, in one of the great moments of literary judgment, was like, “How come he costs more than the other people?” She said something very nice about me. He has got on his desk a paperweight that’s a check for a million dollars in lucite. We weren’t talking nearly that much. So I came up with the title Dangerous Dances. I had never heard a Hall and Oates record. So I met them. It was over the course of a summer. So I did that and made the government happy. That’s one book I try not to espouse. But everyone knows I wrote that, it has my name on it. As I wanted, as my ex-agent says.

Now. Johnny’s Last Cigarette, which as I said was many years later. I don’t even think that was ten years ago.

JK: I think that came out in 2014, between Me and the Devil and Under Tiberius.

NT: I get so sick of all this political correctness. I mean, every man. Every woman was once a child. And there are all these good. Beautiful childhood moments and feelings. Which is the greatest step on earth that we lose. It’s not a nefarious book like Kill Your mother—which may not be a bad idea—but sweet. Why do we rob these kids of the dreaminess of the truth? So Johnny’s first Cigarette, Johnny’s First whatever. I was living in Paris at the time when I wrote that.. I knew a woman who was one of my best translators into French. We put the idea together with a publisher I knew in Marseilles and a wonderful artist-illustrator we found and were so excited about.

To tell you the truth I think the idea of legislating feeling is like…How the fuck do you legislate feeling? And forbidden words. It may have been Aristotle who said, when men fear words, times are dark. You and I have spoken about this. Sometimes we don’t even understand what it is about this or that word. It’s like that joke—a guy goes in for a Rorschach test, and the psychologist tells him. “Has anyone ever told you you have a sexually obsessed mind?” And the guy says, “Well, what about you, showing me all these dirty pictures?” What do these words mean? I don’t know. Why is it a crime to call a black man a crocodile? I have always consciously stood against performing any kind of political correctness. And I have written some long letters to people I felt deserved an explanation of my feelings.

JK: Whenever people get outraged because some comedian cracked an “inappropriate” joke, and they say, “How could he say such a thing?” I always respond, “Well, someone has to, right?”

NT: Yeah. So one book came from the government’s desire to have their share of what I’m making. We’re all government employees. The other was, why can’t I write something that’s soft and sweet with a child’s vocabulary that’s not politically correct?

JK: If Dangerous Dances and Johnny’s First Cigarette were anomalies, I’ve always considered another two of your books companion pieces. Or at least cousins. King of the Jews an Where Dead Voices Gather are both biographies, or maybe anti-biographies, of men about whom very little—or at least very little that’s credible—is known: Arnold Rothstein and Emmett Miller. And that gives you the freedom to run in a thousand directions at once. They’re books made up of detours and parentheticals and digressions, and what we end up with are essentially compact histories of the world with these figures at the center. They strike me as your purest works, and certainly very personal works. More than any of your other books, it’s these two that allow readers to take a peek inside your head. Does that make any sense to you?

NT: Yes, it makes perfect sense. In fact I couldn’t have put it any better myself. This whole myth of what they called the Mafia in the United States—there’s no mafia outside of Sicily. Or called organized crime, was always Italians. The Italians dressed the part, but the Jews made the shirts. It was always an Italian-Jewish consortium. And this Irish mayor wants to play ball? So now it’s Irish. Total equal opportunity. It was basically…Well, Arnold Rothstein was the son of shirt makers. Not only did he control, but he invented what was organized crime in New York. He had the whole political system of New York in his pocket. Emmet Miller was this guy who made these old records that went on to be so influential without his being known. Nobody even knew where or when he was born. The appeal to me was as both an investigator and then to proceed forward with other perspicuities, musings and theories. I never thought of them before as companion works until you mentioned it, but they are.

JK: People have tended to focus on the amount of obsessive research you do. Which is on full display in these books, but what they too often overlook, which is also on full display here, is that you contain a vast storehouse of arcane knowledge. It’s like you’ve fully absorbed everything you’ve ever read, and it just spills out of you. These forgotten histories and unexpected connections.

NT: I’ve always kept very strange notebooks. I still do, except now it’s on the computer. There’s no rhyme or reason to these notebooks, it’s just,”don’t want to forget this one.”

JK: Speaking of research, has your methodology changed in the Internet Age? I’m trying to imagine you working on Under Tiberius and looking up”First Century Judea” on Wikipedia.

NT: The Internet demands master navigation. There are sites which have reproduced great scholarly, as opposed to academic, works. There’s also every lie and untruth brought to you by the Such-and Such Authority of North America. This is what they call themselves. I experienced this within the past week. It was not only complete misinformation, but presented in the shoddiest fashion, such as “Historians agree…” I mean, what historians? I couldn’t find a one of them.

So my methodology. I love Ezra Pound’s phrase, “the luminous detail.” Something you find somewhere or learn somewhere…They don’t even have a card catalog at New York Public Library anymore, let alone books. You want an actual book, they have to bring it in from New Jersey. Who cares anymore? What they care about is who’s in a TV series, and they whip out their Mickey Mouse toys and, “look, there he is!”

JK: I was thinking about this on the way over. You and I both remember a time when if you were looking for a specific record or book or bit of information, you could spend months or years searching, scouring used bookstores an libraries. There was a challenge to it.

NT: It was not just a challenge. It was a whole illuminating process unto itself, because of what you come to by accident. So in looking for one fact or one insight, you would gather an untold amount. That is what it’s about.

JK: Nowadays if I’m looking for, say, a specific edition of a specific book, I take two minutes, go online, and there it is. I hit a button, and it’s mailed to me at my home. Somehow it diminishes the value, as opposed to finally finding something I’d been searching for for years. Nothing has any value anymore.

NT: No, definitely not. When I was living down in Tennessee, all those Sunday drives, guys selling stuff out of their garages. Every once in awhile you hit on something, or find something you didn’t even know existed. Now education on every level, especially on the institutional, but even on a personal level, is diminished. People are getting stupider, and that probably includes myself.

JK: And me too. Now, if I could change course here, you’re a man of many contradictions. Maybe dichotomies is a better term. A streetwise Italian kid who’s a bookworm. A misanthrope who seeks out the company of others. A libertine who is also a highly disciplined, self-educated man of letters. It’s even reflected in your prose—someone who is always swinging between the stars and the gutter. It’s led some people to say there are two Nick Tosches. Is this something you recognize in yourself?

NT: Yes. It’s never been a goal, it’s just…

JK: How you are?

NT: Yeah. I’ve noticed it, and much to my consternation and displeasure and inconvenience, yeah. But there’s no reward in seeking to explain or justify it.

JK: One of the most intriguing and complex of these is the savage heretic who keeps returning to religious themes, the secrets of the Church and the sacred texts. And of course the devil in one guise or another is lurking through much of your work. Again it’s led some people to argue that since you were raised Catholic, this may represent some kind of striving for redemption. You give any credence to that?

NT: No. Absolutely not.

JK: Yeah, it would seem Under Tiberius would’ve put the kibosh on that idea.

NT: I don’t even consider myself having been raised Catholic, in the modern made-for-TV sense of that phrase. I was told to go to church on Sundays and confession on Saturdays, and I usually went to the candy store instead. I was confirmed, I had communion. To me, it was a much deeper, much more experiential passage when I came to the conclusion that there was no Santa Clause than when I came to the conclusion there was no God. I remember emotionally expressing my suspicions about Santa Claus to my mother. Toward the end of his life, I was talking to my father one day, and I said, “By the way, do you believe in God?” And he said no. I said me neither. And that was about the only real religious conversation we ever had. I think religion, without a doubt since its invention—and God was an invention of man—is a huge indefensible evil force in this world. When people believe in a religion which calls for vengeance upon those whose beliefs are different, it’s not a good sign. Not a good sign.

JK: This is something I’ve been curious about. Two of your novels—In the Hand of Dante and Under Tiberius—are predicated on the idea that you come into possession of manuscripts pilfered from the Vatican library. The library comes up a few other times as well. You write about it in such detail and with an insider’s knowledge. Either I was fooled by your skills as a convincing fiction writer, or you’ve spent your share of time there. And if the latter, how does a heretic like you end up with Vatican credentials?

NT: Okay. You go buy yourself a very beautiful, very important let’s say, leather portfolio with silk ribbon corner stays that keeps the documents there. Then you set about…Well, my friend Jim Merlis’ father-in-law, for instance, won the Nobel Prize in physics right around then. So I went to Jim and said, “Hey Jim, do you suppose you could get your father-in-law to write me a letter of recommendation? I know I never met the man.” Had a tough life, but won the Nobel Prize. Did a beautiful letter for me. I don’t even know that I kept it. You put together five letters that only Jesus Christ could’ve gathered. And he probably couldn’t have because he was unwashed. It was twice as difficult for me, because I had no academic affiliation, not even a college degree. But the Vatican was so nice. There are two libraries. One involves a photo I.D. and the other one doesn’t. They gave me two cards, and they made me a doctor. That’s how you get in. So what do you do once you’re in? They have the greatest retrieval library I’ve ever seen. The people that you meet. One guy was a composer. Wanted to see this exact original musical manuscript because he wanted to make sure of one note that may have changed. So this was all real—I just hallucinated the rest. If you can use a real setting, you’re one step closer to gaining credibility with the person who reads you. I still have my membership cards, though I think they must’ve expired. They were great. You go to a hotel and they ask you to show them photo ID? “Ohhh…”

JK: One of the themes that runs throughout your work is fear. Fear as maybe the most fundamental motivating human emotion.

NT: Any man who thinks he’s a tough guy is either a fool or a liar. Fear is I think one of the fundamental formative elements. And I’m just speaking of myself becoming a writer. Choosing to express yourself with great subtlety in some cases, when what you want to express is so inchoate. But that was a long time ago. I still believed in the great charade. These days I’m just living the lie. But it’s so much better than fear. To convey fear. The more universal the feeling, the easier it is to convey powerful emotions. There was a line in Cut Numbers; “He thought the worst thing a man can think.” Michael Pietsch my editor said, “What is that thing?” And I said “Michael, every person who reads that will have a different idea.” It’s an invocation of the Worst Thing. One woman might read it and think of raping her two-year-old son. Some guy might think of robbing his father. To you or I it might not be that bad a thing, but to that person it’s the Worst Thing.

JK: That’s the magic of reading.

NT: That is the magic of reading. That’s the bottom line. Writing is a two-man job. It takes someone to write it and Someone to read it who’s not yourself.

JK: Exactly. Readers bring what they have to a book, and take away from it what they need, what interpretation has meaning for them.