#jared krebsbach

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Atum, Osiris and Achaemenid theology during the First Persian Period in Egypt-III

A Pharaoh and the Apis Bull. Bronze, Late Period Egypt, currently at the British Museum Height: 15.50 centimetres: Length: 28 centimetres Weight: 2.19 kilograms (Weight combined. 1.64 kg bull and 0.55kg king) Depth: 9 centimetres. Source: https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/Y_EA22920

This is the third part (conclusion and bibliography) of the paper of Pr. Jared Krebsbach “ The Persians and Atum Worship in Egypt's 27th Dynasty.” I will presesnt also some thoughts of mine on it.

“Conclusion

It is well documented that the Persians left their conquered subjects free to practise their native religions throughout the Achaemenid Empire. But numerous Persian inscriptions also indicate that the Persians held strongly to their own religious beliefs. Examination of 27th dynasty religious texts reveals a pattern in which the Egyptian god Atum was given a place of prominence by the Persians because of his similarity to their own god. The Persian theological ideas of the Lie versus Truth also paralleled the Egyptian concepts of Maat and Isfet . Ultimately, the Persians’ elevation of Atum had to do with this particular god’s association with kingship and the Persian concept of kingship. In Egyptian texts Atum was the “Lord of All” while the Persian king was described as the “king of the world.” It is clear that Persian theologians made a conscious decision to elevate Atum to a place of prominence in the 27th dynasty. This elevation helped them legitimize their rule over Egypt while never forfeiting that which was important to them on a spiritual level.

University of Memphis, United States of America

Bibliography

Allen, L. (2005) The Persian Empire. Chicago, University of Chicago Press.

Allen, T. G. (1974)The Book of the Dead: Ideas of the ancient Egyptians concerning the hereafter as expressed in their own terms. Chicago, University of Chicago Press.

Boyce, M. (2001) Zoroastrians: Their religious beliefs and practices. London, Routledge.

Brugsch, H. (1878) Ein wichtiges Denkmal aus den Zeiten Königs Sêsonq I. Zeitschrift für Ägyptische Sprache und Altertumskunde 16, 37- 41.

Clark, P. (1998) Zoroastrianism: An introduction to an ancient faith. Portland, Sussex Academic Press.

Cruz-Uribe, E. (1988)The Hibis Temple Project. Vol. 1.Translations, commentary, discussions and sign-list. San Antonio, Van Siclen Books.

Faulkner, R. O. (1969) The ancient Egyptian Pyramid Texts. Oxford, Clarendon Press.

Faulkner, R. O. (1973)The ancient Egyptian Coffin Texts. Vols. 1 and 3. Oxford, Aris and Phillips.

Frankfort, H. (1978) Kingship and the gods: A study of ancient Near Eastern religion as the Integration of society and nature. Chicago, University of Chicago Press.

Gomaà, F. (1973) Chaemwese Sohn Ramses II und Hoherpriester von Memphis. Wiesbaden, Otto Harrassowitz.

Griffiths, J. G. (1980) The origins of Osiris and his cult. Leiden, Brill.

Herodotus (1996) The Histories (translated by Aubrey De Sélincourt). London, Penguin.

Joisten-Pruschke, A. (2008) Das Religiöse Leben der Juden von Elephantine in der Achämenidenzeit. Wiesbaden, Otto Harrassowitz.

Kent, R. G. (1953) Old Persian: Grammar, texts, lexicon. 2nd edition. New Haven, American Oriental Society.

Kienitz, F. K. (1953) Die politische Geschichte Ägyptens vom 7. biszum 4.Jahrhundert vor der Zeitwende. Berlin, Akademie Verlag.

Lichtheim, M. (1980) Ancient Egyptian literature. Vol. 2: The New Kingdom. Los Angeles, University of California Press.

Lorton, D. (1985) Considerations on the origin and name of Osiris. Varia Aegyptiaca 1, 113-126.

Malandra, W. W. (1983) An introduction to ancient Iranian religion: Readings from the Avesta and the Achaemenid inscriptions. Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press.

Malinine, M., Vercoutter, J. and Posener, G. (1968) Catalogue des stèles du Sérapeum de Memphis. 2 Vols. Paris, Imprimerie Nationale.

Manetho (2004) Aegyptiaca (translated by W. G. Waddell). Cambridge, Harvard University Press.

Muscarella, O. W. (1992) Fragment of a royal head. In P. O. Harper, J. Aruz and F. Tallon (eds.) The royal city of Susa: Ancient Near Eastern treasures in the Louvre, 219 -221. New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Olmstead, A. T. (1959) History of the Persian Empire. Chicago, University of Chicago Press.

Oppenheim, L. (1992) Babylonian and Assyrian historical texts. In J. B. Pritchard (ed.) Ancient Near Eastern texts relating to the Old Testament , 265-317. 3rd edition. Princeton, Princeton University Press.3rd edition. Princeton, Princeton University Press.

Otto, E. (1964) Beiträge zur Geschichte des Stierkultein in Ägyptien. Hildesheim, Georg Olms Verlagsbuchhandlung.

Posener, G. (1936) La première domination Perse en Égypte: Recueil d’inscriptions hiéroglyphiques. Cairo, Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale.

Simpson, W. K. (1957) A running of the Apis in the reign of ‘Aha and passages in Manetho and Aelian. Orientalia 26, 139-142.

Vallat, F. (1974) Les textes cunéiformes de la statue de Darius. Cahiers de la Délégation Archéologique Française en Iran 4, 161-170.

Vercoutter, J. (1962) Textes biographiques du Sérapéum: Contribution à l’étude des stèles votives du sérapéum:. Paris, Honoré Champion.

Yoyotte, J. (1972) Les inscriptions hiéroglyphiques: Darius et l’Égypte. Journal Asiatique 260, 253-266

Zaehner, R. C. (1961) The dawn and twilight of Zoroastrianism. New York, G. P. Puntnam’s Sons.”

Source: https://www.academia.edu/824587/The_Persians_and_Atum_Worship_in_Egypts_27th_Dynasty

Jared Krebsbach

As I have already said in the first of my posts on Pr. Krebsbach’s paper, the subject of a possible Egyptian-Persian religious syncretism during the first Persian domination of Egypt is a very interesting one. My remarks on this paper are the following:

1/ Technically speaking, when does the “27th Dynasty” (Persian rulers of Egypt seeing themselves as Pharaohs) end? It is sure that Cambyses and Darius I tried to play the role of Egyptian Pharaoh, but what about their successors (Xerxes I, Artaxerxes I, Darius II) till the Egyptian revolt of 404 BCE and the appearance of a new series of Egyptian rulers, which ended with the reconquest of Egypt by Artaxerxes III in 343 BCE? Is there any evidence that these Achaemenid rulers took the title of Pharaoh and tried to perform the duties resulting from this title, even through delegates? I ask because it is known that when Xerxes ascended to the Persian throne, he chose not to take the title of king of Babylon, a title that his predecessors had taken since Cyrus’ conquest of Babylonia in 539 BCE, in a move not without political but also perhaps theological significance. What about Egypt?

2/ It is sure that the Persians have shown a remarkable “political acumen”, as Pr. Krebsbach says: the Achaemenid Persians were the greatest empire builders the world had seen till then and obviously their success was due not only to their military, but also to their political skills. Religious tolerance was an aspect of the Achaemenid policies toward the conquered peoples crucial for the consolidation of their empire. However, the Achaemenid Empire was not some kind of commonwealth of free peoples, as some enthusiastic historians of ancient Persia tend to present it, and skillful policies were not the only means of consolidation of the Persian imperial power: the Achaemenids were conquerors and violence or the threat of use of violence played a major role in their domination over conquered peoples. The Persian Great Kings knew also very well how to inspire terror to their subjects and rivals, as the inscription of Behistun and other sources clearly indicate, through the frequent use of cruel punishments such as impalement, crucifixion and mutilations. The Achaemenid religious tolerance too had its limits, as for instance the Persians have destroyed systematically the Greek shrines in Asia Minor and mainland Greece during Xerxes’ campaign, for reasons that are still debated among historians.

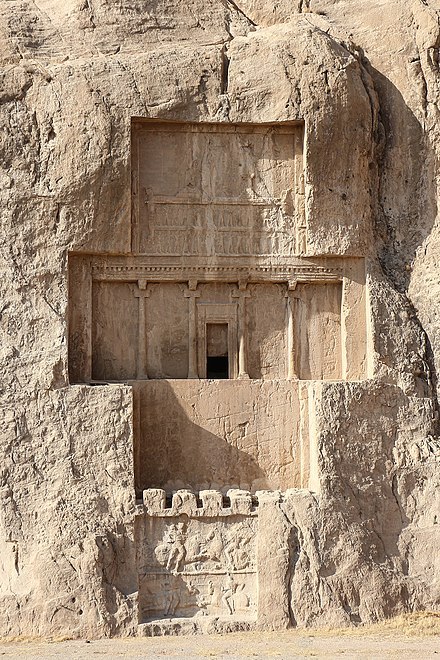

Darius I on his tomb, Naqsh-e Rustam, Fars Province, Iran 3/ It results from Pr. Krebsbach’s paper that the Persian theologians and their Egyptian collaborators operated essentially an identification between the Iranian Ahura Mazda and the Egyptian Atum. It is also beyond doubt that this effort of syncretism had mainly a political purpose, namely to legitimize Darius I as Pharaoh of Egypt but also as “King of the Universe”. However, it seems that there was also a theological basis for this identification, as Persians and Egyptians believed respectively to Ahura Mazda and Atum as gods Creators of the universe, a common belief with an obvious important theological, but also (proto-)philosophical potential.

This effort of Persian-Egyptian syncretism, with its genuine religious basis and its political instrumentalization, is to be compared with Herodotus’ effort in the Book II of Histories to show that the Greek gods were adaptations of the Egyptian ones and to establish a fundamental commonality beyond the cultural differences between Greeks and Egyptians, but also with his reticence to speak about the Egyptian gods when this was not absolutely necessary for his narrative, out of respect for the Egyptian religion or because divine things were for him beyond human investigation.

Moreover, we should not forget that, as Pr. Krebsbach shows in what he writes about the Persians and Osiris, despite the common belief in a Creator god the Egyptian and Persian systems of religious beliefs and practices were very different and this put serious restrictions on the efforts of syncretism between them. This is not without relation with the fact that, although Darius I enjoyed as it seems some popularity in Egypt, most Egyptians have never believed that the Achaemenids were legitimate Pharaohs and they revolted against the Persian rule when they could.

Ethnicities of the Empire, on the tomb of Darius I. The nationalities mentioned in the DNa inscription are also depicted on the upper registers of all the tombs at Naqsh-e Rustam, starting with the tomb of Darius I.[6] The ethnicities on the tomb of Darius further have trilingual labels over them for identification, collectively known as the DNe inscription. One of the best preserved friezes is that of Xerxes I. Source:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tomb_of_Darius_the_Great

4/ Beyond the Persian-Egyptian relation, what I find very important in Pr. Krebsbach paper is that the claim of the Achaemenid kings that they had a Divine Mandate to be “Kings of the World”, “Lords of the Universe” and “Kings of the four rims of the earth” not only confirms Herodotus’ report that the Persian nomos was to “always expand”, but also sheds light on what we could see as a crucial ideological aspect of the conflicts between the Achaemenid Empire and the Greek free city-states known as the Persian wars.

#ancient egypt#ancient persia#egyptology#achaemenid empire#herodotus#jared krebsbach#zoroastrianism#atum#osiris

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Herodotus and the Egyptian historical tradition-III

“THE EGYPTIAN PRIESTS AS SOURCE FOR HERODOTUS

With so much of Herodotus’ information on Egyptian history coming directly or indirectly from the priests, one must consider the importance of them as a source of Egyptian historical memory and the influence they had on not only Herodotus’ narrative, but also the works of Diodorus and Manetho. As noted above, the priests read to Herodotus from a list 330 kings “all of them Egyptians except eighteen, who were Ethiopians” (II.100). If Herodotus had access to the Turin Canon through an Egyptian proxy, then why was the chronology so garbled? For instance Rhampsinitus (Ramesses) is listed as the king who immediately preceded the Fourth Dynasty king Cheops (Khufu) (II.124), while the chronology of the Twenty Fifth and Twenty Sixth Dynasty kings is fairly accurate. With the post-Ramesses II kings one must assume that his information was derived from a list no longer extant, or as yet undiscovered, since the Turin Canon ends with the reign of Ramesses II. Loprieno believes that the inconsistencies in Herodotus’ “king-list” has more to do with the cultural shift in Egypt that took place during the First Millennium, as was discussed above, than any apparent problem with Egyptian chronology or historiography.48 Loprieno’s theory also implies that Herodotus’ chronological problems were the result of an unconscious view of the past by the Egyptians collectively rather than a conscious effort by the priests to omit or amend the deeds of certain kings, according to their opinions, when they related the king-list to Herodotus. A good example of the Egyptians relating their own nuanced view of Egyptian history to Herodotus, and thereby influencing his work, concerns the account of Khufu.

Khufu is described by Herodotus as a terrible and unpopular king who closed the temples, forced his subjects to build his pyramid, and even prostituted his own daughter in order to acquire funds needed to finish the project (II.124-26). So then, why does Herodotus dedicate so much negative attention to Khufu? The answer to this question and the problem with the chronology lies not with Herodotus, and goes beyond the idea of a cultural and political break with the past as argued by Loprieno, but can be found with the priests who gave him that information. In his account of Egyptian chronology, Herodotus was merely an intellectual pawn of the Egyptian priests who dictated either directly or indirectly not only what kings he would write about, but how they were to be remembered. For reasons yet to be determined, which are outside of the scope of the current paper, Khufu was not a popular king with the Egyptian priests in the fifth century BC49 and Herodotus, not being able to read Egyptian, had no choice but to report what they told him. The Egyptian priesthood transferred their historical memory and historiography, which was based on their opinions and politics, into Herodotus’ narrative and with it part of the Egyptian sense of history also seeped into The Histories.”

Jared Krebsbach- The University of Memphis Herodotus, Diodorus, and Manetho: An Examination of the Influence of Egyptian Historiography on the Classical Historians, New England Classical Journal 41.2 (2014) 88-111

file:///C:/Users/USer/Downloads/Herodotus_Diodorus_and_Manetho_An_Examin%20(2).pdf

I find this article very interesting, that’s why I have reproduced large excerpts from it. However, I think that the author’s thesis that Herodotus was just an “intellectual pawn” in the hands of the Egyptian priests is extreme and should be rejected (the other extreme is the outlandish and now discredited in the scholarly community thesis of some that Herodotus never spoke to Egyptian priests and never visited Egypt).

And this because first of all Herodotus expresses directly or indirectly some scepticism about what the Egyptian priests had told him on the pre-Saite history of Egypt, secondly because his Greek mindset plays for sure a role in the interpretation of what he had been told by the Egyptian priests (via interpreters).

But the question of the Egyptian historical consciousness of the Late Period, of the historical agendas of the Egyptian priests of that era and their reflection in Herodotus’ work is a very important one, and I will return to it, presenting the different points of view of eminent Egyptologists on these topics.

#herodotus#ancient greek historians#classical greek authors#ancient egypt#egyptology#jared krebsbach

0 notes

Text

Herodotus and the Egyptian historical tradition-II

“ HERODOTUS AND HIS PHILOSOPHY OF HISTORY

The first of the three historians to be discussed here is Herodotus, due primarily to both the chronological primacy of his work and the dominant influence of his Histories both in and out of academia. In order to better understand the historian from Halicarnassus’s philosophy of history, a brief assessment of his sources, objectives, and methodology must first be performed. Herodotus gathered most of his information from two sources – things he observed firsthand and oral testimony,36 which was usually, at least in the case of Egypt, in the form of the accounts of scribes and priests.37 Compared to his observational and oral sources, the amount of source material he collected from existing libraries concerning Egypt appears to be negligible, because Hecataeus of Miletus is the only known Greek historian before Herodotus who wrote on Egypt, although Herodotus does mention him. Obviously there can be many problems associated with oral testimony as a source for writing a historical narrative,38 even if those entrusted with the protection of the historical knowledge try their best to be as unbiased as possible in their transmission of said knowledge from generation to generation because “in the course of three or four generations they undergo considerable changes.”39 The changes in these oral transmissions were further aggravated in Herodotus’ case by his lack of knowledge of any non-Greek language, but despite this barrier his information was probably more correct than not.40 Despite the occasional unreliability of oral accounts, Herodotus was able to collect and observe enough factual evidence to comprise a fairly reliable account of many aspects of Egyptian culture and history.”

Jared Krebsbach- The University of Memphis Herodotus, Diodorus, and Manetho: An Examination of the Influence of Egyptian Historiography on the Classical Historians, New England Classical Journal 41.2 (2014) 88-111

file:///C:/Users/USer/Downloads/Herodotus_Diodorus_and_Manetho_An_Examin%20(2).pdf

0 notes

Text

Herodotus and the Egyptian historical tradition- I

“Constructing ancient Egyptian chronology is a multi-disciplined study that requires the historian to have a working knowledge of archeology, philology, and at least a basic grasp of the classical historians’ surviving works which concern, at least partly, the history of Egypt. The three classical historians most often cited by modern scholars in regard to ancient Egyptian history are Herodotus, Diodorus, and Manetho, and although each of these produced works that are unique, they also used much of the same source material and employed some of the same historiographical methods. As any historian knows, the sources of a historical narrative are extremely important because they can determine the accuracy and importance of any narrative being compiled, but oftentimes mistakes in modern narratives are not the result of the ancients recording information incorrectly, but of modern scholars misinterpreting why the ancients recorded such information.

Mario Liverani proposed that modern scholars of ancient Near Eastern texts should be careful “to view the document as a source for the knowledge of itself – i.e., as a source of the knowledge on the author of the document, whom we know from the document itself.”1 He argued that, by taking this approach and by viewing texts from “from all possible points of view,”2 we can begin to answer why certain texts were written. Although the purpose of Liverani’s thesis was to better comprehend texts from ancient Egypt, Mesopotamia, and the Levant, this method can be applied here to these classical historians – at least their chapters which concern Egypt – since much of their source material was derived from native sources. It is not the intent of this paper to dissect and determine what parts of the writings of the classical historians are truthful concerning Egyptian history and chronology (other scholars have already aptly done this 3 ) but rather to determine why they wrote what they did. When the classical historians’ chapters on Egypt are viewed through this prism, then modern scholarship can more accurately discern what aspects of their writings were determined by Greek historiographical traditions and those that were the result of the Egyptian philosophy of history. Ultimately, this study will show that Greek and Egyptian historical traditions often converged to create a narrative history of Egypt that was at times factually correct – in a modern or even ancient Greek sense – but also full of motifs that appear as ahistorical to modern scholars, but were rather logical in the Egyptian historiographical sense. Such an examination also demonstrates the importance of the Egyptian priesthood in transmitting the historical record, since they were the primary vehicle for this historiographical convergence as they controlled the information that the classical historians would record.”

Jared Krebsbach- The University of Memphis Herodotus, Diodorus, and Manetho: An Examination of the Influence of Egyptian Historiography on the Classical Historians, New England Classical Journal 41.2 (2014) 88-111

Jared Krebsbach is professor of history at the University of Memphis, USA - https://memphis.academia.edu/JaredKrebsbach

https://www.academia.edu/7834447/Herodotus_Diodorus_and_Manetho_An_Examination_of_the_Influence_of_Egyptian_Historiography_on_the_Classical_Historians

0 notes

Text

Atum, Osiris and Achaemenid theology during the First Persian Period in Egypt-I

The Zvenigorodsky seal, housed in the Hermitage Museum of Saint Petersburg, Russia (inv.no. Гл-501). The cylinder depicts an Achaemenid King of Kings holding a kneeling captive with a hand, and subjugating him with a spear held by the other hand. The kneeling captive wears an Egyptian crown.[3] Behind the king there are four prisoners with a rope around their necks, the rope being held by the king himself. Their garment is similar to that of the Egyptians seen on the reliefs of Naqsh-e Rostam.[5] The scene therefore refers to Ancient Egypt and to an act of conquest or the suppression of a rebellion by an Achaemenid king. Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zvenigorodsky_seal

“The Persians and Atum worship in Egypt’s 27th dynasty Jared B. Krebsbach

(in Current Research in Egyptology 2010: Proceedings of the Eleventh Annual Symposium, edited by Maarten Horn, Joost Kramer, Daniel Soliman, Nico Staring, Carina van den Hoven, and Lara Weiss, 97-104. Oxford: Oxbow Books, 2011)

Introduction

In the past few decades, some valuable studies have helped shed light on Egypt’s 27th dynasty, also known as the First Persian Period (Kienitz 1953; Posener 1936). These studies have helped elucidate several aspects of this often enigmatic period. One such aspect is the Achaemenid Persians’ tendency to allow their subject peoples the freedom to practise their native religions unhindered (Allen 2005, 126-127). At the same time, the Persians influenced their foreign subjects’ religious traditions to a certain extent, particularly with the taxation of temple revenues (Joisten-Pruschke 2008, 64). Similarly, to date, the influence of Egypt’s long enduring religious traditions on the Persians remains unexamined. Textual evidence, surviving in both Egypt and Persia, suggests that the Persians had a special affinity to the Egyptian god Atum and may have altered their own religion – at least publicly – to conform to a more Egyptian religious expression. This paper will explore why the Persians favoured Atum over other Egyptian gods, particularly Osiris, and how Atum related to the Persians’ own religious practices. Ultimately, it will be shown that the Persians’ decision to alter or modify their religion publicly, was less a matter of trying to conform to the conquered Egyptians’ religion, but rather a conscious decision that was in line with their own theological beliefs. That this decision also helped realize their political and propagandistic agenda further demonstrates the Persians’ political acumen.

Atum in 27th dynasty hieroglyphic texts

The hieroglyphic texts in which the Persians invoked the Egyptian deity Atum are varied and appear to suggest the importance of this god to the foreign rulers. Probably the most interesting of these inscriptions comes from the Memphite Serapeum. Most inscriptions in the Serapeum – either on votive stelae donated by non-royals or epitaphs left by kings – invoked the syncretic deity Apis-Osiris (Malinineet al.1968; Vercoutter 1962). Although the common Apis-Osiris was invoked in Serapeum inscriptions from the reigns of Cambyses and Darius I, there exist two notable instances of the syncretic Apis-Atum. Epitaph stelae from year 6 of Cambyses and year 4 of Darius I invoked Apis-Atum as he “who grants all life” (Posener 1936, 31, 37). It should be pointed out that although an Osiris-Apis-Atum-Horus is known from a 19th dynastySerapeum inscription (Otto 1964, 19; Brugsch 1878, 38), these two mentions of Apis-Atum by the Persians are the most known from any dynasty. Another important primary source in which the Persians gave homage to Atum in a hieroglyphic inscription is the statue of Darius I from Susa. In this inscription the king is described “the son of Re born of Atum” while Atum is referred to as the “lord of Heliopolis” (Yoyotte1972, 253- 266). The historical significance of this statue cannot be overstated because it is the only known intact example of Persian colossal royal statuary from the Achaemenid Period (Muscarella 1992, 219- 220), so the placement of Atum as foremost of the Egyptian pantheonis important. Two other 27th dynasty sources that place Atum in a central position are the naophorous statue of the doctor Udjahorresent (Posener 1936, 1-26) and the Hibis temple in the el-Kharga oasis (Cruz-Uribe 1988). Although construction of the Hibis temple began in the 26th dynasty during the reign of Psammetichus II and continued through the Roman Period, Darius I’s cartouche is written in numerous places and there are several references to Atum and images of the king with this god (Cruz-Uribe 1988, 44, 62).

The Egyptian statue of Darius I at Susa, currently at the National Museum of Iran, Tehran. Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Egyptian_statue_of_Darius_I

Atum in Egyptian religious texts

In order to determine the significance Atum held to the Persians in the above inscriptions, one must first examine this deity’s origins and significance in Egyptian religion. Atum is first referenced in dozens of utterances from the 5th and 6th dynasty Pyramid Texts (Faulkner 1969). In these early religious texts, Atum was often depicted as a solar god who created the universe. As a solar god, he was sometimes paired with Re (Faulkner 1969, 44-45, Utterance 217), but also stood alone as the sun, such as in Utterance 362 where he was the sun of the night sky (Faulkner 1969, 118). His creative attributes were described in many texts, since the “earth was issued from Atum” (Faulkner 1969, 49-50, Utterance 222) but he also protected the dead king by “enclosing him within your arms” (Faulkner 1969, 42 -43, Utterance 215) and by making“the king sturdy” (Faulkner 1969, 131-132, Utterance 402). The numerous references to Atum’s attributes as creator and protector in the Pyramid Texts demonstrates this deity’s theological importance in early Egyptian religion – at least in as far as it was articulated in writing – which no doubt contributed to his appearance in 27th dynasty texts. Atum continued to play a central role in Egyptian religion after the Old Kingdom, which can be seen in the Coffin Texts from the Middle Kingdom and the Book of the Dead and other literature from the New Kingdom. In the Coffin Texts Atum is referred to as the “Lord of All”(Faulkner 1973, I: 144, Spell 167; III: 167, Spell 1130) a title which coincides with his creative and kingly attributes, as revealed in the Pyramid Texts. The concept of Atum as the “Lord of All” or “All Lord” was also present in the New Kingdom tale The Contendings of Horus and Seth, as the god sat at the head of the Ennead which decided the fates of Horus and Seth (Lichtheim1976, II: 214- 223). Atum was also prevalent in the New Kingdom Book of the Dead, as he possessed the same attributes discussed above but was also depicted as the destroyer of the universe (Allen 1974, 183 -185, Spell 175). One can list many more examples from all periods of pharaonic history that demonstrate the importance of Atum in the Egyptian pantheon. The theological reasons for the Persians’ acceptance of Atum have already been touched upon and will be discussed more thoroughly below in comparison with ancient Persian religion, but the elevation of Atum over Osiris must now be explored.

God Atum in a relief with hieroglyphic caption (Deir el-Bahari). Source:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Atum

Osiris and Egyptian mortuary cult and myth

Like Atum, Osiris was referenced numerous times in the Pyramid Texts where he was associated with the dead king. The dead king’s fate in the afterlife was inexorably intertwined with Osiris, thus it is stated “if he lives this king will live” (Faulkner 1969, 46-48, Utterance 219). The mortuary features of Osiris cannot be overlooked here as they played a key role in both the Osirian myth and cult. J. Griffiths stated:

“The Osiris myth, in the sense that it grew out of the royal funerary ceremonial, may perhaps be classified as a cult legend, remembering that the cult is part of the cult of the dead” (Griffiths1980, 35).

The dead king’s Osirian mortuary attributes, particularly mummification, are alluded to in the Pyramid Texts where he receives “natron that you may be divine” (Faulkner 1969, 140,Utterance 423) and is commanded to “gather your bones together” (Faulkner 1969, 150, Utterance 451). It is believed that the emergence of mummification – although primitive by New Kingdom standards – coincided with the emergence of the Osiris cult sometime in the Old Kingdom (Griffiths 1980, 53), which may have been the result of a “significantly improved method of treating the body of the royal deceased” (Lorton 1985, 119). Osiris’ importance as a mortuary deity associated with the dead king continued throughout Egyptian history and eventually combined with the divine Apis bull in the late New Kingdom to create a new syncretic deity who enjoyed a position of popularity among royals and non-royals alike. According to the transmissions of Manetho, the Apis cult was already active by the 2nd dynasty (Manetho 2004, 37 -39), while a black and white diorite bowl from the reign of ‘Aha, published by William Kelly Simpson, is the oldest known Egyptian text concerned with the cult (Simpson 1957, 139-142). Although the Apis cult had existed since the beginning of dynastic Egypt, it was not until the late New Kingdom that the Memphite Serapeum, the necropolis of the sacred Apis bulls, was first built (Gomaà 1973, 39). Besides serving as the resting place of the sacred bulls, the Serapeum also became a repository for over thousand votive stelae (Vandier 1964, 130). Most of these stelae referred to the dead Apis bull as “Apis-Osiris” or “Osiris-Apis,”which combined the mythological attributes of potency and the chthonic into one deity. Although Cambyses invoked Apis-Osiris on the sarcophagus of an Apis bull interred in year six of his reign (Posener 1936, 35), the possibility that Osiris’ chthonic attributes appeared foreign to the Persians should be considered.”

Head of the God Osiris, ca. 595–525 B.C.E. Brooklyn Museum . Source:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Osiris

Source: https://www.academia.edu/824587/The_Persians_and_Atum_Worship_in_Egypts_27th_Dynasty

The topic of this study of Pr. Krebsbach is very interesting. I will post it in its entirety in three posts and I will include in the last of these posts some thoughts of mine. For the moment I remark only that the importance of the cults of Osiris and Apis for the religious life of the ancient Egyptians of the Late Period is something that Herodotus emphasizes in Book II and the beginning of Book III of “Histories”, although in general he avoids mentioning Osiris’ name because he finds that this would be inappropriate, but also that Herodotus refers to the existence of at least one Egyptian statue of Darius I.

The choice of the pictures in these posts is mine, but I give the sources from which I have taken them.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Atum, Osiris and Achaemenid theology during the First Persian Period in Egypt-II

The Tomb of Cyrus the Great , the founder of the Achaemenid Empire, at Pasargadae, Fars Province, Iran. Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tomb_of_Cyrus#Reconstruction_of_the_tomb

This is the second part of the paper of Pr. Jared Krebsbach “ The Persians and Atum Worship in Egypt's 27th Dynasty”

“Persian funerary rituals

During the Achaemenid Period, the bodies of dead Persian kings were placed in wax and interred in tombs but not mummified (Herodotus 1996, 64, Book I, 140; Olmstead 1959, 66). Eventually, Persians adopted a mortuary ritual in which the body of the deceased was left for vultures to consume (Clark 1998, 114-117). The theological reason for the ritual of exposure originates with the Persian belief that corpses were unclean vessels of evil spirits. One scholar of Persian religion stated:

“The greatest pollution in death, however, the priests maintained, was from the bodies of righteous people, for a concentration of evil forces was necessary to overwhelm the good, and these continuedto hover round the corpse. So from the moment of death the body was treated as if highly infectious and only professional undertakers and corpse-bearers approached it, who were trained to take ritual precautions. If possible the funerary service was performed the same day, and the body was carriedat once to a place of exposure” (Boyce 2001, 44).

Although the Achaemenid kings did not practice the ritual of corpse exposure themselves – there is evidence of Persian nobles participating in this ritual during the Achaemenid Empire (Boyce2001, 59) – it probably originated during their rule. Herodotus observed that some Persians performed this burial ritual in his time:

“There is another practice, however, concerning the burial of the dead, which is not spoken of openly and is something of a mystery; it is that a male Persian is never buried until the body has been torn by a bird or a dog. I know for certain that the Magi have this custom, for they are quite open about it. The Persians in general, however, cover a body with wax and then bury it. The Magi are a peculiar caste” (Herodotus 1996, 64, Book I, 140).

Modern scholars of Persian religion believe that at around the time of the Achaemenid Empire the Magi, who “were a hereditary caste entrusted with the supervision of the national religion”(Zaehner 1961, 163), introduced the practice of exposing corpses to vultures, among other traditions, that would later become known as “Zoroastrianism.” Zaehner wrote:

“It does, however, seem fairly certain that it was the Magi who were responsible for introducing three new elements into Zoroastrianism – the exposure of the dead to be devoured by vultures and dogs, the practice of incestuous marriages, and the extension of the dualist view of the world to material things and particularly the animal kingdom” (Zaehner 1961, 163).

It should be noted that although the Achaemenid kings did not practice the ritual of corpse exposure themselves, their tombs still separated the living from the unclean corpse. The tomb of Cyrus demonstrates “with what care Zoroastrian kings prepared their sepulchers so that there should be no contact between the embalmed body – unclean in death, even though there was nodecay – and the living creations” (Boyce 2001, 53). Perhaps the Egyptian ritual of mummification – with its excessive handling and reverence of “unclean” corpses – seemed too foreign to a people who were accustomed only to burial, but were on the verge of accepting a new practice that involved the annihilation of the corpse. Therefore Osiris, a god associated with mummification, by extension may also have been viewed as strange and foreign to the Persians.

The Tomb of Darius I of Persia in Naqsh-e Rustam, Fars Province, Iran. Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tomb_of_Darius_the_Great

Achaemenid Persian theology

Osiris’ subordinate position to Atum in many of the Pyramid Texts (Faulkner 1969, 46 -48,Utterance 219) and his association with mortuary myth and cult, may have played a role in his subordination and/or omission in 27th dynasty religious texts, but in order to truly understand why the Persians chose Atum over Osiris one must examine the royal Achaemenid inscriptions from Persia, particularly those of Darius I. In terms of written texts, Egyptian religion was much older than Persian, so was therefore articulated in a much more complex way, but we do have texts at our disposal that can aid in the understanding of Achaemenid Period Persian theology. The trilingual inscription of Behistan – which was inscribed on the face of a cliff above an ancient caravan route in Persia – relates the accounts of Darius I’s suppression of rebellions in the Achaemenid Empire. In the five columns of Old Persian inscriptions, Ahuramazda, the primary Persian god, is invoked seventy times (Kent 1953, 116-134). In these texts, Ahuramazda mainly serves as a protector of Darius and bestower of his role as the king of the Achaemenid Empire. Lines 48-61 of column one proclaimed:

“After that I besought the help of Ahuramazda; Ahuramazda bore me aid; of the month Bagayadi ten days were past, then I with a few men slew that Gaumata the Magian, and those who were his foremost followers. A fortress by name Sikayauvati, a district by name Nisaya, in Media – there I slew him. I took the kingdom from him. By the favor of Ahuramazda I became king; Ahuramazda bestowed the kingdom upon me” (Kent 1953, 120).

In the fourth column of the Old Persian inscription from Behistan, Darius further explained that Ahuramazda gave him aid because “I was not a Lie follower” (Kent 1953, 132). The Lie – known in Persian as Drugh – is, in the Behistan texts, explicitly equated with the rebellions against Darius, on both a physical and metaphysical level, as “a violent onslaught against the established order” (Zaehner 1961, 156). As such, Darius was viewed as “Ahuramazda’s chosen representative on earth [...] who maintains the just moral order within society while protecting society from rebellion” (Malandra 1983, 47). The Behistan inscriptions were written to commemorate Darius I’s victory over numerous usurpers, but gives us a glimpse into the theological functions of the god Ahuramazda as protector, upholder of order, and bestower of kingship. Other Achaemenid Period inscriptions from Persia also describe this deity as the creator of the universe.

Darius I’s inscription of Behistun, Mount Behistun, Kermanshah Province, Iran. Punishment of captured impostors and conspirators: Gaumāta lies under the boot of Darius the Great. The last person in line, wearing a traditional Scythian hat and costume, is identified as Skunkha. His image was added after the inscription was completed, requiring some of the text to be removed. Source:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Behistun_Inscription

Inscriptions from the magnificent palace at Persepolis, built during the reign of Darius I,and his tomb at Naqsh-i Rustam also reveal much about how the Persians viewed Ahuramazda. At Persepolis, Ahuramazda is credited as the one who “created Darius the king, he bestowed on him the kingdom” (Kent 1953, 136) while at his tomb the god is described as the one “who created this earth, who created yonder sky, who created man” (Kent 1953, 138). Perhaps the most important Old Persian inscription, as far as the current topic is concerned, that invoked Ahuramazda and his attributes as a creator is on the statue of Darius I mentioned above. The Old Persian, Akkadian, and Elamite cuneiform inscriptions on the robes of the statue proclaimed Ahuramazda as the god “who created the sky and the below, who created man, who created happiness for man” (Vallat 1974, 161 170). The fact that Ahuramazda is invoked on the same statue as Atum – and is the only known such occurrence – suggests that Atum is extremely important when considered in the context of the current study.

Ahura Mazda’s image at Persepolis. Source: http://beautifulcity2015.weebly.com/persepolis.html

The Persian affinity for Atum appears to originate with their own religious beliefs, as Atum’s attributes concerning creation, kingship, and protection most closely mirror those of their own god, Ahuramazda. Ahuramazda’s hatred of the Lie and love of the Truth can also be seen in the Egyptian idea of truth or Maat, versus chaos or Isfet.The Persians would have had access to the Egyptian priesthood and knowledge of Egyptian myth and cult, as seen in the example of the Egyptian priest/doctor and ‘collaborator,’ Udjahorresent mentioned above (Posener 1936,1-26), so therefore would have been able to choosean Egyptian deity in 27th dynasty texts who most closely represented their own theological ideas. As much as the functions and attributes of Atum corresponded closely to Ahuramazda, Osiris, who ruled from the Underworld and was associated with death and mortuary cult, may have appeared foreign and strange to the Persians. These theological factors for the Persians’ affinity to Atum are compelling, but a final reason for their worship of this god which concerns the Persian concept of kingship must be examined.

The Achaemenid Persian concept of kingship and Atum

Unfortunately due to a dearth of textual evidence, the Achaemenid concept of kingship was rarely articulated in writing. Henri Frankfort believed that the origins of Achaemenid Period kingship can be traced directly to Mesopotamia. He wrote:

“In the ruins of Pasargadae, Persepolis, and Susa we have material proof that kingship under Cyrus the Great and Darius I was given a setting for which there were no Persian precedents and in which the Mesopotamian ingredients are clearly recognizable. If the pillared halls of the Achaemenian palaces had prototypes in the vast tents of nomadic chieftains, the walled artificial terrace, the monstrous guardians at the gates, the revetments of sculptured stone slabs, and the panels of glazed bricks derived from Babylon, Assur, and Nineveh, even though they were executed by craftsmen from all over the empire and transfused with a spirit demonstrably Persian” (Frankfort 1978, 338).

The Mesopotamian idea of the king as the ruler of the world can be traced back to Sargon of Akkad who first designated himself as “he who rules the Four Quarters” (Frankfort 1978,228) while his son Naram-Sin took the epithet “King of the Four Quarters” (Frankfort 1978,228). Later, the Assyrian king Shamsi-Adad would modify the epithet further to “King of the Universe” (Frankfort 1948, 229). It was from these ideas of kingship that Cyrus, the first king of the Achaemenid Empire, styled himself as ruler when he marched victoriously into Babylon in 539 BC as is written on the Cyrus Cylinder. On the cylinder Cyrus was very explicit that he was king not just of Persia and Mesopotamia, but of the entire world. He stated:

“I am Cyrus, king of the world, great king, legitimate king, king of Babylon, king of Sumer and Akkad, king of the four rims of the earth” (Oppenheim 1992, 316).

As mentioned above, Atum was often referred to in religious texts as the “All Lord” or “Lord of All” which coincides with the Persian concept of kingship. When Cambyses conquered Egypt he found a god, Atum, who not only corresponded theologically in many ways with his god, Ahuramazda, but also with his inherited position as king and lord of the universe.”

The Cyrus Cylinder. Source:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cyrus_Cylinder

Source: https://www.academia.edu/824587/The_Persians_and_Atum_Worship_in_Egypts_27th_Dynasty

#achaemenid empire#ancient persia#ancient egypt#egyptology#cyrus the great#darius i of persia#zoroastrianism#herodotus

3 notes

·

View notes