#japanese women in history

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

"Female swordsmiths were among the rarest female artisans to be found in feudal Japan because of the religious connotations that came with being a swordsmith. Japan is renowned for the strength of its samurai warriors who relied primarily on their swords in battle. If a sword stood the test of battle, it was said that Kanayago-kami, the deity of metal, was on one's side. This leads back to the forging process, because the deity must not be angered during the creation of a sword to ensure the sword will be strong and effective. It was believed that Kanayago-kami was an envious woman who didn't like other women—so much that women were either forbidden in the furnace room during the forging process or, if they entered the room, they could not wear make up.

A woman who chose to become a swordsmith despite the Kanayago-Kami possible disapproval did not inscribe her name on her handiwork, as male swordsmith did, because the sword was less likely to sell if the buyer knew it was created by a woman. There is only one woman who is known for her sword forging because she did inscribe her name on a blade: Onna Kunishige (1733-1808). Kunishige became an apprentice swordsmith after her father and uncle died when she was just sixteen years old."

Cranor Lawrence, "Artisans in Feudal Japan", in: Boyett Colleen, Tarver H. Micheal, Gleason Mildred Diane (eds.), Daily Life of Women An Encyclopedia from Ancient Times to the Present

#history#women in history#women's history#historyedit#japan#japanese history#onna kunishige#18th century#working women#women's work#women at work#japanese art#asian history

106 notes

·

View notes

Text

Time Travel Question 74: Assorted Performances XIII

These Questions are the result of suggestions from the previous iteration.

Please add new suggestions below if you have them for future consideration.

#Time Travel#Concerts#20th Century#Performances#Lady Be Good#Fred Astaire#Adele Astaire#West End#1926#Theatre History#Theater History#The Lady's Not for Burning#1948#Christopher Fry#The Takarazuka Revue#1910's#History of drag#Japanese history#Women in History#Alan Rickman#Les Liaisons Dangereuses.#One Week 1920#Buster Keaton#Silent Film#Stephen Sondheim#Aristophanes#Musicals#Broadway#The Frogs#Movie History

70 notes

·

View notes

Text

Shōgun Historical Shallow-Dive: the Final Part - The Samurai Were Assholes, When 'Accuracy' Isn't Accurate, Beautiful Art, and Where to From Here

Final part. There is an enormous cancer attached to the samurai mythos and James Clavell's orientalism that I need to address. Well, I want to, anyway. In acknowledging how great the 2024 adaptation of Shōgun is, it's important to engage with the fact that it's fiction, and that much of its marketed authenticity is fake. That doesn't take away from it being an excellent work of fiction, but it is a very important distinction to me.

If you want to engage with the cool 'honourable men with swords' trope without thinking any deeper, navigate away now. Beyond here, there are monsters - literal and figurative. If you're interested in how different forms of media are used to manufacture consent and shape national identity, please bear with me.

I think the makers of 2024's Shōgun have done a fantastic job. But there is one underlying problem they never fully wrestled with. It's one that Hiroyuki Sanada, the leading man and face of the production team, is enthusiastically supportive of. And with the recent announcement of Season 2, it's likely to return. You may disagree, but to me, ignoring this dishonours the millions of people who were killed or brutalised by either the samurai class, or people in the 20th century inspired by a constructed idea of them.

Why are we drawn to the samurai?

A pretty badly sourced, but wildly popular history podcast contends that 'The Japanese are just like everybody else, only more so.' I saw a post on here that tried to make the assertion that the show's John Blackthorne would have been exposed to as much violence as he saw in Japan, and wouldn't have found it abnormal.

This is incorrect. Obviously 16th and 17th century Europe were violent places, but they contained violence familiar to Europeans through their cultural lens. Why am I confidently asserting this? We have hundreds of letters, journals and reports from Spaniards, Portuguese, Dutch and English expressing absolute horror about what they encountered. Testing swords on peasants was becoming so common that it would eventually become the law of the land. Crucifixion was enacted as a punishment for Christians - first by the Taiko, then by the Tokugawa shogunate - for irony's sake.

Before the end of the feudal period, battles would end with the taking of heads for washing and display. Depending on who was viewing them, this was either to honour them, or to gloat: 'I'm alive, you're dead.' These things were ritualised to the point of being codified when real-life Toranaga took control. Seppuku started as a cultural meme and ended up being the enforced punishment for any minor mistake for the 260 years the ruling samurai class acted as the nation's bureaucracy. It got more and more ritualised and flowery the more it got divorced from its origin: men being ordered by other men to kill themselves during a period of chaotic warfare. I've read accounts of samurai 'warriors' during the Edo period committing seppuku for being late for work. Not life-and-death warrior work - after Sekigahara, they were just book-keepers. They had desk jobs.

Since Europe's contact with Japan, the samurai myth has fascinated and appalled in equal measure. As time has gone on, the fascination has gone up and the horror has been dialled down. This is not an accident. This isn't just a change in the rest of the world's perception of the samurai. This is the result of approximately 120 years of Japanese government policies. Successive governments - nationalist, military authoritarian, and post-war democratic - began to lionize the samurai as the perfect warrior ideal, and sanitize the history of their origin and their heydey (the period Shōgun covers). It erases the fact that almost all of the fighting of the glorious samurai Sengoku Jidai was done by peasant ashigaru (levies), who had no choice.

It is important to never forget why this was done initially: to form an imagined-historical ideal of a fighting culture. An imagined fighting culture that Japanese invasion forces could emulate to take colonies and subdue foreign populations in WWI, and, much more brutally, in WWII. James Clavell came into contact with it as a Japanese Prisoner of War.

He just didn't have access to the long view, or he didn't care.

The Original Novel - How One Ayn Rand Fan Introduced Japan to America

There's a reason why 1975's Shogun novel contains so many historical anachronisms. James Clavell bought into a bunch of state-sanctioned lies, unachored in history, about the warring states period, the concept of bushido (manufactured after the samurai had stopped fighting), and the samurai class's role in Japanese history.

For the novel, I could go into great depth, but there are three things that stand out.

Never let the truth get in the way of a good story. He's a novelist, and he did what he liked. But Clavell's novel was groundbreaking in the 70's because it was sold as a lightly-fictionalised history of Japan. The unfortunate fact is the official version that was being taught at the time (and now) is horseshit, and used for far-right wing authoritarian/nationalist political projects. The Three Unifiers and the 'honour of the samurai' magnates at the time is a neat package to tell kids and adults, but it was manufactured by an early-20th century Japanese Imperial Government trying to harness nationalism for building up a war-ready population. Any slightly critical reading of the primary sources shows the samurai to be just like any ruling class - brutal, venal, self-interested, and horrifically cruel. Even to their contemporary warrior elites in Korea and China.

Fake history as propraganda. Clavell swallowed and regurgitated the 'death before dishonour', 'loyalty to the cause above all else', 'it's all for the Realm' messages that were deployed to justify Imperial Japanese Army Class-A war crimes during the war in the Pacific and the Creation of the Greater East Asian Co-Properity Sphere. This retroactive samurai ethos was used in the late Meiji restoration and early 20th century nationalist-military governments to radicalise young Japanese men into being willing to die for nothing, and kill without restraint. The best book on this is An Introduction to Japanese Society by Sugimoto Yoshio, but there is a vast corpus of scholarship to back it up.

Clavell's orientalism strays into outright racism. Despite the novel Shōgun undercutting John Blackthorne as a white savior in its final pages - showing him as just a pawn in the game - Clavell's politics come into play in every Asia Saga novel. A white man dominates an Asian culture through the power of capitalism. This is orthagonal to points 1 and 2, but Clavell was a devotee of Ayn Rand. There's a reason his protagonists all appear cut from the same cloth. They thrust their way into an unfamiliar society, they use their knowledge of trade and mercantilism to heroically save the day, they are remarked upon by the Asian characters as braver and stronger, and they are irresistible to the - mostly simpering, extremely submissive - caricatures of Asian women in his novels. Call it a product of its times or a product of Clavell's beliefs, I still find it repulsive. Clavell invents (nearly from whole cloth, actually) the idea that samurai find money repulsive and distasteful, and his Blackthorne shows them the power of commerce and markets. Plus there are numerous other stereotypes (Blackthorne's massive dick! Japanese men have tiny penises! Everyone gets naked and bathes together because they're so sexually free! White guys are automatically cool over there!) that have fuelled the fantasies of generations of non-Japanese men, usually white: Clavell's primary audience of 'dad history' buffs.

2024's Shōgun, as a television adaptation, did a far better job in almost every respect

But the show did much better, right? Yes. Unquestionably. It was an incredible achievement in bringing forward a tired, stereotypical story to add new themes of cultural encounter, questioning one's place in the broader world, and killing your ego. In many ways, the show was the antithesis to Clavell's thesis.

It drastically reigned in the anachronistic, ahistorical referencees to 'bushido' and 'samurai honor', and showed the ruling class of Japan in 1600 much more accurately. John Blackthorne (William Adams) was shown to be an extraordinary person, but he wasn't central to the outcome of the Eastern Army-Western Army civil war. There aren't scenes of him being the best lover every woman he encounters in Japan has ever had (if you haven't read the book, this is not an exaggeration). He doesn't teach Japanese warriors how to use matchlock rifles, which they had been doing for two hundred years. He doesn't change the outcome of enormous events with his thrusting, self-confident individualism. In 2024's Shōgun, Blackthorne is much like his historical counterpart. He was there for fascinating events, but not central. He wasn't teaching Japanese people basic concepts like how to make money or how to make war.

On fake history - the manufactured samurai mythos - it improved on the novel, but didn't overcome the central problems. In many ways, I can't blame the showrunners. Many of the central lies (and they are deliberate lies) constructed around the concept of samurai are hallmarks of the genre. But it's still important to me to notice when it's happening - even while enjoying some of the tropes - without passively accepting it.

'Authenticity' to a precisely manufactured story, not to history

There's a core problem surrounding the promotion and manufactured discussion surrounding 2024's Shōgun. I think it's a disconnect between the creative and marketing teams, but it came up again and again in advertising and promotion for the show: 'It's authentic. It's as real as possible.'

I've only seen this brought up in one article, Shōgun Has a Japanese-Superiority Complex, by Ryu Spaeth:

'The show also valorizes a supreme military power that is tempered by the pursuit of beauty and the highest of cultures, as if that might be a formula for peace. Shōgun displays these two extremes of the Japanese self, the savagery and the refinement, but seems wholly unaware that there may be a connection between them, that the exquisite sensibility Japan is famous for may flow from, and be a mask for, its many uses of atrocious domination.'

Here we come to authenticity.

'The publicity surrounding the series has focused on its fidelity to authenticity: multiple rounds of translation to give the dialogue a “classical” feel; fastidious attention to how katana swords should be slung, how women of the nobility should fold their knees when they sit, how kimonos should be colored and styled; and, crucially, a decentralization of the narrative so that it’s not dominated by the character John Blackthorne.'

It's undeniable that the 2024 production spent enormous amounts of energy on authenticity. But authenticity to what? To traditional depictions of samurai in Japanese media, not to history itself. The experts hired for gestures, movement, costumes, buildings, and every other aspect of the show were experts with decades in experience making Japanese historical dramas 'look right', not experts in Japanese history. But this appeal to 'Japanese authenticity' was made in almost every piece of promotional material.

The show had only one historical advisor on staff, and he was Dutch. The numerous Japanese consultants, experts and specialists brought on board (talked about at length in the show's marketing and behind the scenes) were there to assist with making an accurate Japanese jidaigeki. It's the difference between hiring an experienced BBC period drama consultant, and a historian specialising in the Regency. One knows how to make things look 'right' to a British audience. The other knows what actually happened.

That's fine, but a critical viewing of the show needs to engage with this. It's a stylistically accurate Japanese period drama. It is not an accurate telling of Japanese history around the unification of Japan. If it was, the horses would be the size of ponies, there would be far more malnourished and brutalised peasants, the word samurai would have far less importance as it wasn't yet a rigidly enforced caste, seppuku wouldn't yet be ritualised and performed with as much frequency, and Toranaga - Tokugawa - would be a famously corpulently obese man, pounding the saddle of his horse in frustration at minor setbacks, as he was in history.

The noble picture of restraint, patience, refinement and honour presented by Hiroyuki Sanada as Toranaga/Tokugawa is historical sanitation at its most extreme. Despite being Sanada's personal hero, Tokugawa Ieyasu was a brutal warlord (even for the standards of the time), and he committed acts of horrific cruelty. He ordered many more after gaining ultimate power. Think a miniseries about the Founding Fathers of the United States that doesn't touch upon slavery - I'm sure there have been plenty.

The final myth that 2024's Shōgun leaves us with is that it took a man like Toranaga - Tokugawa Ieyasu - to bring peace to a land ripped assunder by chaos. This plays into 19th century notions of Great Man History, and is a neat story, but the consensus amongst historians is if it wasn't Tokugawa, it would have been some other cunt. In many cases, it very nearly was. His success was historical contingency, not 5D chess.

So how did this image get manufactured, to the point where the Japanese populace - by and large - believes it to be true? Very long story short: after a period of rapid modernisation, Japan embraced nationalism in the late 19th century. It was all the rage. Nationalism depends on a glorified past. The samurai (recently the pariahs of Japanese history) were repurposed as Japan's unique warrior heroes, and woven into state education. This was especially heated in the 1920s and 30s in the lead up to the invasion of Manchuria and Japan's war of aggression in the Pacific. Nationalism + militarism = the modern Japanese samurai myth, to prepare men to obey orders unquestioningly from a military dictatorship.

This persists in the postwar period. Every year since 1963, Japan's state broadcaster NHK commissions a historical drama - a Taiga Drama, where many of this show's actors got their starts - that manufactures and re-enforces the idea of samurai as noble, artful, honourable people. Read a book - read a Wikipedia article! - and you'll see that most of it stems from Tokugawa-shogunate era self-propaganda. It's much like the European re-interpretation of chivalry. In Europe's case, chivalry in actual history was a set of guidelines that allowed for the sanctioned mass-rape and murder of civilians, with a side of rules regarding the ransoming of nobles in scorched-earth military campaigns. In Japan's case, historical figures that regularly backstabbed each other, tortured rival warriors and their lessers, and inflicted horrific casualties on the peasants that they owned (we have a term for that) are cast as noble, honourable, dedicated servants of the Empire.

Why does this matter to me? Samurai movies and TV shows are just media, after all. The issue, for me, is that the actors, the producers - including Hiroyuki Sanada - passionately extoll 'accuracy' as if they genuinely believe they're telling history. They talk emotionally about bushido and its special place in Japanese society.

But the entire concept of bushido is a retroactive, post-conflict, samurai construction. Bushio is bullshit. Despite being spoken of as the central tenet of 2024's Shōgun by actors like Hiroyuki Sanada, Tadanobu Asano, and Tokuma Nishioka, it simply didn't exist at the time. It was made up after the advent of modern nationalism.

It was used to justify horrendous acts during the late Edo period, the Meiji restoration, and the years leading up to the conclusion of Japan's war of aggression in the Pacific. It's still used now by Japan's primarily right-wing government to deny war crimes and justify the horrors unleashed on Asia and the Pacific during World War II as some kind of noble warrior crusade. If you ever want your stomach turned, visit the museum attached to Yasukuni Shrine. It's a theme park dedicated to war crimes denial, linked intimately to Japan's imagined warrior past. Whether or not the production staff, cast, and marketing team of 2024's Shōgun knew they were engaging with a long line of ahistorical bullshit is unknown, but it is important.

It's also important to acknowledge that, having listened to many interviews with Rachel Kondo and Justin Marks, they were acutely aware that they weren't Japanese, to claim to be telling an authentically Japanese story would be wrong, and that all they could do was do their best to make an engaging work that plays on ideas of cultural encounter and letting go. I think the 'authenticity!' thing is mostly marketing, and judicious editing of what the creators and writers actually said in interviews.

So... you hate the show, then? What the hell is this all about?

No, I love the show. It's beautiful. But it's a beautiful artwork.

Just as the noh theatre in the show was a twisting of events within the show, so are all works of fiction that take inspiration from history. Some do it better than others. And on balance, in the show, Shōgun did it better than most. But so much of the marketing and the discussion of this adaptation has been on its accuracy. This has been by design - it was the strategy Disney adopted to market the show and give it a unique viewing proposition.

'This time, Shōgun is authentic!*

*an authentic Japanese period drama, but we won't mention that part.

And audiences have conflated that with what actually happened, as opposed to accuracy to a particular form of Japanese propaganda that has been honed over a century. This difference is crucial.

It doesn't detract from my enjoyment of it. Where I view James Clavell's novel as a horrid remnant of an orientalist, racist past, I believe the showrunners of 2024's Shōgun have updated that story to put Japanese characters front and centre, to decentralise the white protagonist to a more accurate place of observation and interest, and do their best to make a compelling subversion of the 'stranger in a strange land' tale.

But I don't want anyone who reads my words or has followed this series to think that the samurai were better than the armed thugs of any society. They weren't more noble, they weren't more honourable, they weren't more restrained. They just had 260 years in which they worked desk-jobs while wearing two swords to write stories about how glorious the good old days were, and how great people were.

Well... that's a bleak note to end on. Where to from here?

There are beautiful works of fiction that engage much closer with the actual truth of the samurai class that I'd recommend. One even stars Hiroyuki Sanada, and is (I think) his finest role.

I'd really encourage anyone who enjoyed Shōgun to check out The Twilight Samurai. That was the reality for the vast majority of post-Sekigahara samurai

For something closer to the period that Shogun is set, the best film is Seppuku (Hara-Kiri in English releases). It is a post-war Japanese film that engages both with the reality of samurai rule, and, through its central themes, how that created mythos was used to radicalise millions of Japanese into senseless death during the war. It is the best possible response to a romanticisation of a brutal, hateful period of history, dominated by cruel men who put power first, every single time.

I want to end this series, if I can, with hope. I hope that reading the novel or watching the 1980 show or the 2024 show has ignited in people an interest in Japanese culture, or society, or history. But don't let that be an end. Go further. There are so many things that aren't whitewashed warlords nobly killing - the social history of Japan is amazing, as is the women's history. A great book for getting an introduction to this is The Japanese: A History in 20 Lives.

And outside of that, there are so many beautiful Japanese movies and shows that don't deal with glorified violence and death. In fact, it makes up the vast majority of Japanese media! Who would have thought! Your Name was the first major work of art to bridge some of the cultural animosity between China and Japan stemming from WW2, and is a goofy time travel love story. Perfect Days is a beautiful movie about the simple joy of living, and it's about the most Tokyo story you can get.

Please go out, read more, watch more. If you can, try and find your way to Japan. It's one of the most beautiful places on earth. The people are kind, the food is delicious, and the culture is very welcoming to foreigners.

2024's Shōgun was great, but please don't let that be the end. Let it be the beginning, and I hope it serves as a gateway for you.

And I hope our little fandom on here remembers this show as a special time, where we came together to talk about something we loved. I'll miss you all.

#shōgun#shogun#shogun fx#toda mariko#john blackthorne#anjin#adaptationsdaily#perioddramasource#hiroyuki sanada#yoshii toranaga#akechi mariko#history#history lesson#japan#world war ii#japanese culture#tokugawa ieyasu#hosokowa gracia#william adams#sengoku jidai#writer stuff#book adaptation#women in history#social history#period drama

154 notes

·

View notes

Text

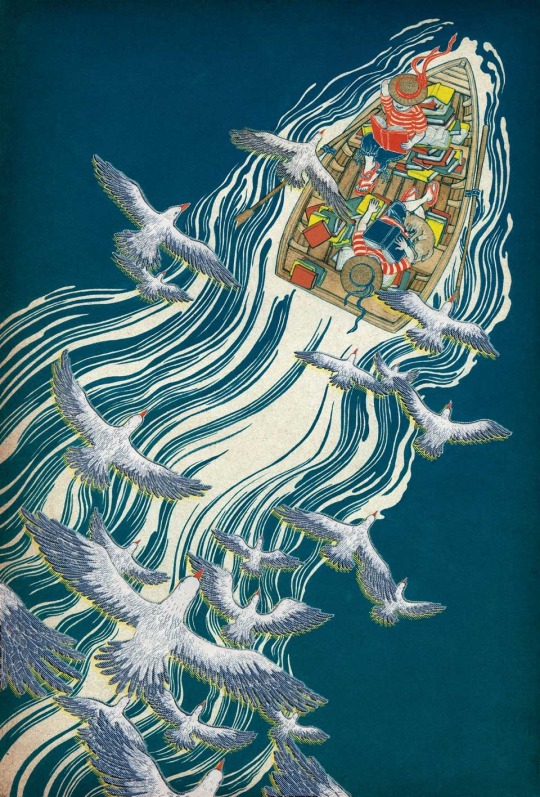

Yuko Shimizu

Artwork for Library of Congress National Book Festival

2016

#yuko shimizu#illustrator#commercial art#seascape#boats#seagulls#woman artist#women artists#art history#modern art#aesthetictumblr#tumblraesthetic#tumblrpic#japanese art#tumblrpictures#tumblr art#tumblrstyle#artists on tumblr#tumblrposts#aesthetic#graphic art#graphic artists#birdwatching#wildlife#nature

673 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

How Tamahagane (Japanese steel) was made, video by Life were I'm from.

As Japan did not have many iron ore deposits, it had for a long time to rely on more available satetsu 砂鉄 (ironsand, carried for ex. by rivers). Ironsand was then processed in special furnaces called tatara to make prized tamahagane 玉鋼 (traditional Japanese steel, used among other things to forge swords).

If you've seen Princess Mononoke, you know exactly how tatara forge could look like thank to Lady Eboshi's Iron Town:

... and now I have the Tatara women work song stuck into my head <3

youtube

#japan#video#Life were I'm from#arts and crafts#japanese history#tamahagane#steel#satetsu#iron#ironsand#forge#tatara#furnace#industry#princess mononoke#mononoke hime#Tatara women's work song#music#Youtube

297 notes

·

View notes

Note

What are good books about explorers, if I may ask? I'd love to get into some harrowing survival (or just trying to survive) stories.

HI ok these are all heroic age antarctica-centric bc that's all i've had rattling around in my brain for a solid year and a half now so if anyone has non-polar recs pls feel free to throw em in the replies lmao

if we're talking harrowing survival there's nothing more fucked than shackleton's trans-imperial expedition aka endurance and the ross sea party. the classic here is endurance by alfred lansing (and ofc south by ol ernie shackles but i feel like his own account is less approachable to a first time reader) but i also highly recommend the lost men by kelly tyler-lewis for the ross sea party half of the story that often falls to the wayside.

and we can't talk abt shackleton without getting into scott & the terra nova & the race for the pole which WILL take over ur life if u get into it lol. the worst journey in the world by apsley cherry-garrard is required reading (and so is cherry by sara wheeler, possibly my fave biography of all time), and for a more general overview a first-rate tragedy by diana preston is the absolute gold standard. for amundsen ask @roaldamundsen there's the last viking by stephen r. brown which i haven't read yet but i've heard v good things about (nb: u may be recommended roland huntford's books when it comes to amundsen. read them if u want but he's got a Thing against scott which in turn distorts how he approaches amundsen but then again every polar biographer wants to make tender romantic love to their special little guy so)

OH and we can't forget the northern party aka six guys in a hole (NOT sexy) (well–). there are banger first-hand accounts (especially raymond priestley's) but weirdly enough my fave when it comes to this part of the terra nova story is a polar affair by lloyd spencer-davis, which is technically abt the sex lives of adélie penguins. it was the first book i read connected to terra nova and although it leans more popular history than rigorous biography or historical analysis it rly primes u to understand the fricative relationship between the expedition's two intertwined objectives – scientific advancement and imperialist glory – that were the root of most of their issues.

outside of endurance & terra nova i'd be remiss not to rec The gateway book to antarctic history, the madhouse at the end of the earth by julian sancton. i should have put this first bc this is genuinely one of my fave books of all time, polar-related or otherwise. it's a comedy it's a tragedy it's an adventure it's an insight into colonial ambition (although imo this aspect could have been pushed further) it's a romance for two specific guys it could easily be a musical it might be adapted into a tv show or movie in the near future?? it's an absolute trip i rec it to anyone who stands still enough to let me shove a copy in their hands. read madhouse NOW

finally i want to give a shout out to the australasian antarctic expedition which in comparison is less insane than everything else here but it's entirely possible the guy who was once on the australian $100 note ate his dog handler. so like. read alone on the ice by david roberts

(ps. for more boat books see @jesslovesboats's banger posts ✌️⛵️)

#replies.txt#maxer-blaster#ok theres more to alone on the ice than possible cannibal douglas mawson but u have to admit its compelling#also!! i havent read either book yet but the two main ones abt the karluk/wrangel island saga (empire of ice & stone and the ice master)#are v v well regarded and have similar vibes to everything else here even tho it's at the other pole#anyway lmk if u want more recs!! these are just the rly popular/well known ones theres sooo much more to antarctic history#like the scottish expedition!! the japanese one!! BANZARE!!!! and whatever the fuck argentina & chile were doing when they sent#those pregnant women to give birth at research stations for sovereignty claims!!!!#actually if ur interested in that aspect there's a textbook edited by peder roberts & alejandra mancilla called colonialism and antarctica#which. as the title suggests. has a whole bunch of essays abt colonialism and antarctica#something that pop history doesnt often focus on and is still impacting how we interact w the continent today#i have a thesis idea percolating in the back of my mind abt official polar narratives & imperialism & modern writing + tourism#but im doing an entirely different masters rn i dont have time for all that. yet

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

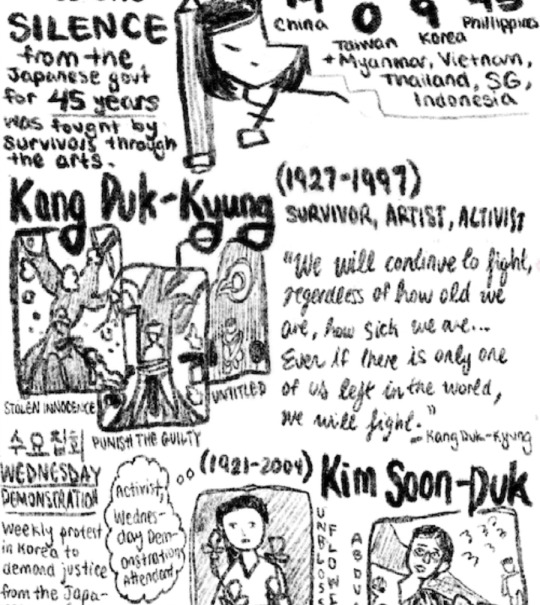

THE "COMFORT" WOMEN OF ASIA: a zine 🦋

Hi everyone, we made a zine about an ongoing fight for the rights of "comfort" women from Korea, China, Taiwan, and the Philippines, who were enslaved by the Japanese military. We explored their art, stories, and worldwide memorials.

HERE is the printable, HERE is the online booklet. Transcription will be available soon!

#zine#zines#comfort women#anti imperialism#japanese imperialism#art history#student organization#gliese art collective#art#korea

156 notes

·

View notes

Text

1/4 ambrotype

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

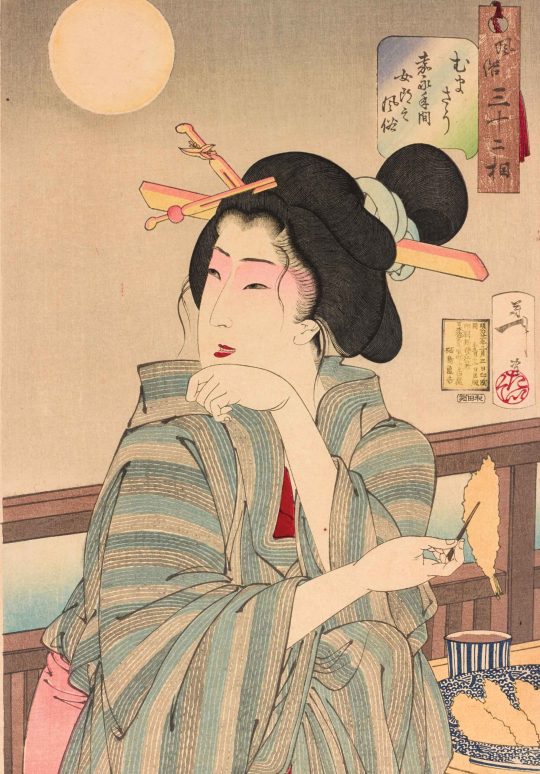

THE TASTY PRINTS & LOVELY LADIES OF THE KAIE PERIOD -- TEMPURA WITH HER TEA.

PIC INFO: "Looks delicious," Appearance of a Courtesan in the Kaei Period, from the series "Thirty-Two Aspects of Women" (1888) by Tsukioka Yoshitoshi. Photo: Nakau Collection.

Source: https://asianartnewspaper.com/life-in-edo-prints/#prettyPhoto[group-135]/2.

#Japanese Courtesan#Japanese Art Prints#Japanese Art#Tsukioki Yoshitoshi#Tempura#Japanese#Japanese Prints#Japanese Cuisine#Nakau Collection#Hair and Makeup#Kimono#Kaei Period#Thirty-Two Aspects of Women#1888#1880s#Yoshitoshi Tsukioki#Japan#Japanese Courtesan Makeup#Japanese Food#Makeup#Japanese Art Print#Japanese fashion#Art Prints#Courtesan#Kaei Period Japan#Japanese Style#Japanese Culture#East Asia#East Asian Art#Art History

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Magic Girls help to remind us that are femininity isn’t a weakness, but something that can be empowering!

✨🚺✨

#history#magic girl#sally the witch#himitsu no akko chan#anime#art history#1960s#womens empowerment#japan#animation#womens history#girl power#feminism#sailor moon#femininity#japanese history#girly girl#1970s#feminine energy#magical girl#kawaii#dolletecore#animecore#feminine history#grl pwr#soft girl#coquette#japanese culture#nickys facts

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Girls of Many Lands cigarette cards

these cards were made from 1850-1959 by a tobacco manufacturer in London.

#vintage#1800s#victorian era#edwardian era#culture#women#history#art#japanese#turkish#kurdish#persian#spanish#montenegro#norway

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Genmei (661-721) was Japan's fourth empress regnant. She was Empress Jitō's half-sister and her match in terms of ambition and political skills. Her rule was characterized by a development of culture and innovations.

Ruling after her son

Like Jitō (645-703), Genmei was the daughter of Emperor Tenji but was born from a different mother. Jitō was both her half-sister and mother-in-law since Genmei had married the empress’ son, Prince Kusakabe (662-689). She had a son with him, Emperor Monmu (683-707).

Kusakabe died early and never reigned, which led to Jitō's enthronement. The empress was then succeeded by her grandson Monmu. The latter’s reign was short. In his last will, he called for his mother to succeed him in accordance with the “immutable law” of her father Tenji. Genmei accepted.

Steadfast and ambitious

Genmei was made from the same mold as her half-sister. She proved to be a fearless sovereign, undeterred by military crises.

She pursued Jitō's policies, strengthening the central administration and keeping the power in imperial hands. Among her decisions were the proscription of runaway peasants and the restriction of private ownership of mountain and field properties by the nobility and Buddhist temples.

Another of her achievements was transferring the capital at Heijō-kyō (Nara) in 710, turning it into an unprecedented cultural and political center. Her rule saw many innovations. Among them were the first attempt to replace the barter system with the Wadō copper coins, new techniques for making brocade twills and dyeing and the settlement of experimental dairy farmers.

A protector of culture

Genmei sponsored many cultural projects. The first was the Kojiki, written in 712 it told Japan’s history from mythological origins to the current rulers. In its preface, the editor Ō no Yasumaro praised the empress:

“Her Imperial Majesty…illumines the univers…Ruling in the Purple Pavillion, her virtue extends to the limit of the horses’ hoof-prints…It must be saif that her fame is greater than that of Emperor Yü and her virtue surpasses that of Emperor Tang (legendary emperors of China)”.

In 713, she ordered the local governments to collect local legends and oral traditions as well as information about the soil, weather, products and geological and zoological features. Those local gazetteers (Fudoki) were an invaluable source of Japan’s ancient tradition.

Several of Genmei’s poems are included in the Man'yōshū anthology, including a reply by one of the court ladies.

Listen to the sounds of the warriors' elbow-guards;

Our captain must be ranging the shields to drill the troops.

– Genmei Tennō

Reply:

Be not concerned, O my Sovereign;

Am I not here,

I, whom the ancestral gods endowed with life,

Next of kin to yourself

– Minabe-hime

From mother to daughter

Genmei abdicated in 715 and passed the throne to her daughter, empress Genshō (680-748) instead of her sickly grandson prince Obito. This was an unprecedented situation, making the Nara period the pinnacle of female monarchy in Japan.

Genmei would oversee state affairs until she died in 721. Before her death, she shaved her head and became a nun, becoming the first Japanese monarch to take Buddhist vows and establishing a long tradition.

Feel free to check out my Ko-Fi if you like what I do! Your support would be greatly appreciated.

Further reading

Shillony Ben-Ami, Enigma of the Emperors Sacred Subservience in Japanese History

Tsurumi Patricia E., “Japan’s early female emperors”

Aoki Michiko Y., "Jitō Tennō, the female sovereign",in: Mulhern Chieko Irie (ed.), Heroic with grace legendary women of Japan

#history#women in history#women's history#japan#japanese history#empress genmei#japanese empresses#historical figures#historyedit#herstory#nara#japanese art#japanese prints

207 notes

·

View notes

Text

Miss Hokusai: The world is beautiful because of "light" and "shadow."

It is believed that many people have seen the famous image of a giant wave engulfing small boats at sea (The Great Wave Of Kanagawa), drawn with traditional Japanese brushstroke techniques. This is the masterpiece of Katsushika Hokusai, a renowned Edo-period artist known across Japan and the world. His works have inspired many European artists, contributing to the development of a Western art movement influenced by Eastern art, known as Japonism.

However, few people know the name and life of the person behind his success — Katsushika Oei, Hokusai's daughter, who possessed artistic talent in brush painting on par with her father. This is her story, brought to life in the 2016 animated film adapted from the Japanese manga by Hinako Sugiura, titled Miss Hokusai. In Japanese, it is known as Sarusuberi (百日紅), which translates to Crape Myrtle, symbolizing the aesthetics and beauty found in woodblock prints (Ukiyo-e) and Japanese brush art, often filled with images of legends, folklore, landscapes, spirits, or imaginary worlds that float beyond reality.

The world is beautiful with "light" and "shadow": A nameless female artist who lived in her father's shadow and became the light for her blind sister.

In the Edo period, the beautiful and unique works of Hokusai shone brightly throughout Japan, like a radiant light. But who knew that behind his glorious fame, there was a young girl who followed in her father’s footsteps, whose skills were second to none.

According to accounts from people who knew the father-daughter artists, it is said that in the early days, Oei rarely signed her name on her work. Sometimes, she used a pseudonym. Many times, she painted on behalf of her father as a nameless artist and sold the work with Hokusai’s name on it. This was because, during the Edo period, female artists' works were often not accepted, as women were expected not to be painters but to take on roles like housewives, merchants, courtesans, or other professions.

Moreover, it was believed that women lacked the skills to observe the world around them and the sexual experience necessary to convey in good art. In addition, most buyers and art consumers were male, so art was produced primarily to serve and cater to male desires. Examples include paintings of courtesans (Oiran), Geisha artists, or erotic depictions of relationships between women and men, women and women, or men and men, meant to serve as illustrated books for sexual arousal.

Thus, society at that time believed that a woman's perspective in creating art for men would either not sell or fail to fully meet men's emotional and sexual desires. These were the challenges that female artists like Oei in the Edo period had to face. Oei encountered many obstacles and had to hone her skills to fight against criticism and judgment in order to gain recognition within a patriarchal world.

However, since Oei understood this societal rule well, she accepted her role as merely a "shadow" under her father's bright "light." She found happiness in observing the world around her to further develop her skills. Her life was considered quite unusual for a woman in the Edo period. Unlike most women of her time, she had no desire to follow the traditional path of being presented for marriage, settling down with a man, and starting a family. Instead, she lived to serve her and her father's passion for art, as well as to study the natural world around her. This made her a courageous, independent, and self-assured woman, different from other women of her era.

On the other hand, Oei became a "light" for the darkened world of her unfortunate blind sister, "Onao." In the story, we see that whenever Oei takes Onao for a walk, she makes an effort to describe to Onao the shapes, colors, objects, people, or places that Onao cannot see with her own eyes.

Oei also expresses her true femininity without having to hide it. She speaks and treats her sister with gentleness and a bright smile, and the two are always filled with laughter from playing together.

This contrasts with her serious and stern expression, her rough and curt tone, or sometimes her silence, speaking only when necessary to project an image of credibility as the one negotiating on behalf of Hokusai with clients. She also had to behave in a commanding manner as the daughter of an important artist.

We can also interpret her behavior toward her father and all of Hokusai's male apprentices as Oei crossing the gender boundary. Her entering into the male-dominated world required her to act equally strong and bold enough for them to accept her as a capable colleague and artist.

It can be said that Oei needed to play different roles depending on the situation, location, and people she encountered. This also tells us that Japanese society, from that era to the present, has expected individuals to behave according to the roles society dictates.

Although Oei could only be a "shadow" in the male-dominated sphere, she was a crucial supporter who helped her father's fame spread far and wide, becoming an indispensable assistant to Hokusai. Moreover, she remained a "beautiful light" for her sister, fulfilling her role in the female sphere according to her gender.

The other side of the red-light district, as seen through the eyes and brushstrokes of Oei

According to accounts from people who knew Oei, she was not only very observant of her surroundings but also deeply fascinated by "light." Every time there was a fire, Oei would be the first to jump out of bed and run excitedly to see it. Her reason for rushing to witness the flames was different from others—she was captivated by the vibrant, intense colors of the fire, which no paint or pigments of that era could replicate.

Oei tried her best to memorize the colors and movements of the flames so she could capture them in her artwork. Her love for vivid tones, combined with the influence of Western art that was beginning to spread in Japan, led Oei to experiment with a new style. She began creating works that used bright colors to represent "light" and darker shades to symbolize "shadow," which was a departure from traditional Japanese paintings that often emphasized softer tones, simplicity, and linework. These innovations helped to distinguish Oei's paintings.

Moreover, her artwork illuminated a different side of the pleasure quarters—the daily lives of courtesans in the red-light district. Oei’s depictions differed from those of her male contemporaries. While male artists of the time often portrayed courtesans as seductive and erotically appealing, Oei’s work reflected their humanity and ordinary aspects. Though by night these women were viewed as objects of sexual desire, praised for their beauty, and skilled in music, art, dance, and theater to entertain male patrons, they were still considered unworthy of becoming wives or taking a place in society, remaining hidden in the world of nightfall.

But who would know that behind the elaborate makeup, the beautifully adorned courtesans living in the red-light district were simply ordinary women, full of beauty, sweetness, emotions, love, hope, dreams, and desires just like anyone else? Oei captured this reality in her paintings with great depth, and her works became well-known, including pieces such as A Beauty Writing Poetry By the Cherry Blossoms at Night, Night Scene in the Yoshiwara, and Three Women Playing Musical Instruments.

Miss Hokusai is an animated film that not only highlights the talents and importance of women who were no less capable than men but also reflects the challenges women faced under the patriarchal system. These include being objectified, having their work judged by male standards, and having to modify their behavior and identity to fit norms established by men.

At the same time, Miss Hokusai presents a clear perspective on women that many might not expect, helping to convey the importance of women's rights in a society striving for gender equality. The first step toward change should begin with understanding and listening to different perspectives.

#miss hokusai#anime#manga#animation#japanese#oiran#japonism#art#ukiyoe#japan#culture#history#edo period#women#female artists#katsushika hokusai#natural art#red light district#folklore#japanese people

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

in one of my courses, i have been assigned a few sections from The Pillow Book, a pre-modern japanese book. It was written by Sei Shonagon, and I cannot believe how across 1000 years, humanity hasn't changed.

I am reading a section called: Hateful Things. And she just lists things that piss her off. For example

old people being gross

men being drunk and rowdy

sneaky links not being sneaky when they leave

babies crying when youre about to get interesting news

people talking badly about other people (like girl thats you)

but also a section called: Pleasing Things. Which is where she writes things that she enjoys

"Acquiring the second volume of a tale whose first volume one has enjoyed. But often it is a disappointment" LIKE 1000 YEARS AGO WOMEN WERE STILL BEING LET DOWN BY SEQUELS.

having an upsetting dream, just for a dream interpreter to say its nothing important

being in a big group talk, but the main (hot) guy talking is only looking at you

being told a sick relative is healed

getting new stationery

winning a card game

watching a self-confident man wait to be praised by oneself, especially if he's pretending not to care

something bad happens to someone you don't like

ordering a comb, it arrives, and its pretty

something good happens to someone you love

She's just,, so human?? and like, of course she was human, but she wrote this book in approximately 990CE, like that's CRAZY long ago, and all of her experiences are so transferable?

like? people from history really were people too, huh

#sei shonagon#diva#girl boss#pillow book#japanese literature#history#women of history#feminism#love#hate

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

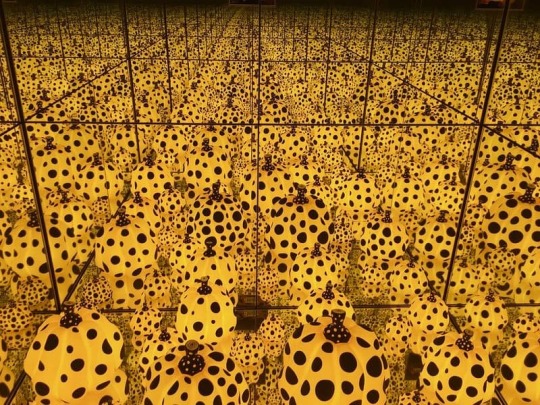

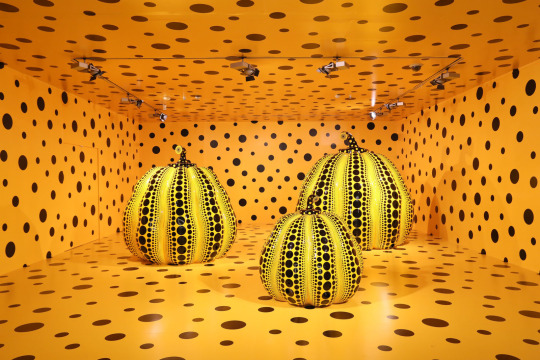

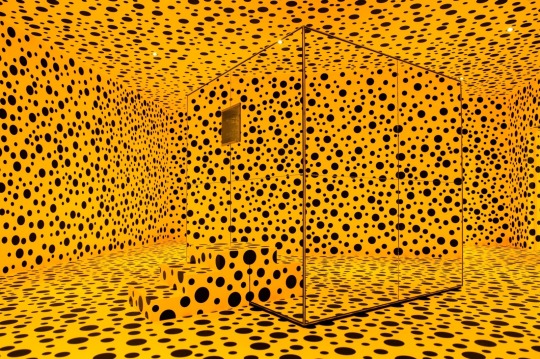

Yayoi Kusama, All the Eternal Love I Have for the Pumpkins, 1993

Yayoi Kusama, A Dream I Dreamed, 2014

Yayoi Kusama, Polka dot-covered orange and black Pumpkin mirror room, 1993

#yayoi kusama#pumpkins#pumpkin aesthetic#japanese artist#japanese art#asian art#contemporary art#woman artist#women artists#woman painter#aesthetic#beauty#modern art#art history#aesthetictumblr#tumblraesthetic#tumblrpic#tumblrpictures#tumblr art#tumblrstyle#artists on tumblr#women in art

215 notes

·

View notes

Text

KOJO MIYAGINO: The Filial Using a Naginata (mid 1800s). Woodblock print, oban tate-e. 36.90cm x 25.40cm. British Museum.

What comes to mind when you hear the word samurai? Men wielding katanas? Ironclad Japanese warriors about to strike a blow? Or perhaps a robed samurai on the verge of self-sacrifice.

How about a kimono-wrapped lady on the verge of kicking ass?

While most women in feudal Japan were expected to adhere to traditional roles, samurai as a rising warrior class (actually called “bushi” before the Kamakura Period) included both men and women. However, "samurai" was a term reserved for men. Women "samurai" were deemed onna-musha (a female warrior on the offensive) or onna bugeisha, a warrior woman on the defensive.

Onna musha were rarer than their onna bugeisha counterparts, who were nevertheless formidable women. Onna bugeisha were trained in martial arts to defend their homes against the frequent ransacking that took place during the Warring States Period in feudal Japan. Their weapon of choice was the naginata, a curved sword mounted on a pole, first used by warrior monks in 750 A.D.

#onna musha#onna bugeisha#female samurai#japanese warrior women#warrior women#kamakura period#naginata#samurai#japanese history

21 notes

·

View notes