#james jacques joseph after tissot

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

Jesus geht nach Jerusalem - Johannes, Bibel von James Jacques Joseph after Tissot (Undatiert, -)

#artwork#art#kunstwerk#kunst#james jacques joseph after tissot#jesus#christ#christus#religion#christianity#bible#bibel#jerusalem#st. john#johannes

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Brief: The Title

The Judas Mark is a title that encapsulates the weight of ultimate betrayal and its lasting consequences. Inspired by the biblical stories of Judas Iscariot and Cain, it symbolizes a mark of disloyalty—one that does not simply condemn but lingers as an inescapable reminder of one’s transgression.

Judas, whose very name has become synonymous with betrayal, sold out Jesus for thirty pieces of silver, an act that sealed his fate and left a permanent stain on his legacy. Similarly, Cain, after murdering his brother Abel, was marked by God—not for immediate punishment, but to ensure he lived with the burden of his actions, preventing an endless cycle of vengeance.

In the story of The Judas Mark, this idea is mirrored in the protagonist’s fate. When judged, he is not deemed wicked enough for damnation, nor worthy of redemption; instead, he is marked by disloyalty, cast out into a world where the forsaken roam. The title itself serves as a key for the audience—subtly guiding them to interpret the film’s themes of sin, judgment, and the isolating nature of betrayal, without ever explicitly stating them. It is a symbol, a curse, and a sentence all at once.

Cain Slaying Abel - Pier Francesco Mola Italian ca. 1650–52

Judas Hangs Himself - James Jacques Joseph Tissot ca. 1896

0 notes

Photo

The Tale by James Jacques Joseph Tissot, ca. 1878-1880

Henry James commented that his two favorite words in the English language were ‘summer afternoon.’ This delightful picture of Tissot’s partner and muse, Kathleen Newton, reading in the garden of their house in Grove End Road, St. John’s Wood, exemplifies the quiet happiness he found with her there, and celebrates the joy of childhood and family life. It exudes the contentment and ease found on a summer afternoon in the garden, surrounded by loved ones. A noted anglophile, Tissot had come to London from his native France in 1871 following the fall of the Paris Commune after the Franco Prussian war. An astute businessman, he had established a reputation on both sides of the Channel prior to the calamity, and was encouraged in his move by Thomas Gibson Bowles, founder of Vanity Fair magazine, for whom he supplied political cartoons. London offered Tissot a safe haven from the horrors of Paris at the time and better immediate prospects for art sales. He soon found a ready market for historical dress and modern-life pictures and earned enough in a year to buy a villa in the north-London suburb popular with artists, St. John’s Wood, at 17 (now 44) Grove End Road. According to the diarist de Goncourt, Tissot’s home was both elegant and welcoming – champagne was always on ice for visitors, and he joked that a footman was employed to polish leaves in the shrubbery. The villa had large gardens, with trees and ponds at front and back. Tissot had the pond in the back garden extended and formalized. Its stone coving can be glimpsed in the distance of The Tale, with surrounding plants including ‘giant rhubarb’ (gunnera) on the left. The pool’s colonnade, familiar from many other of Tissot’s London paintings, is hidden here by the chestnut leaves framing his sitters. Over the course of his time in London, Tissot’s art changed direction from the genre scenes with which he had gained fame, both as a result of having his work rejected from the Royal Academy in 1875 and through his meeting the beguiling Kathleen Newton, one of the two subjects of the present work, in 1876. Born Kathleen Kelly in Agra, where her father was a clerk in the Honourable East India Company’s Civil Service, Kathleen would lead a remarkable life notable for its brevity, modernity and defiance of convention. After the Indian Rebellion she was sent to England for safety and schooling. At the age of 16 she travelled back to India for an arranged marriage to Dr. Isaac Newton, a distinguished army surgeon. On the voyage she met and fell in love with a Captain Palliser, whom Dr. Newton cited in divorce proceedings after Kathleen ran away to join Palliser and became pregnant. She returned to England for the birth of her daughter, and a son, probably also fathered by Palliser, was born before Kathleen met Tissot. The artist’s first certain portrayal of her is the etched Portrait of Mrs. N., made in autumn/winter 1876. Though his Catholicism prevented him from marrying a divorcée, sometime in 1877 she came to live with Tissot, the pair cohabiting as man and wife until her death from tuberculosis in November 1882.

Captured sitting beneath the chestnut tree, in an intimate ‘snapshot’ image, Kathleen reads to her sister’s daughter Lilian Hervey, known as Lily, who lived only a few minutes’ walk from Tissot’s home. Kathleen is reading a story aloud, her lips slightly parted and fingers about to turn a page, and Lily is listening intently. Kathleen’s two children lived with the Herveys, sharing a nanny, and all the children visited Tissot’s house from time to time for walks, musical interludes, play, and picnics in the garden. Tissot made sketches and photographs of Kathleen and the children, which served as source material for paintings and etchings from 1878 to 1882. Lily was especially attached to her aunt and seems to have been a willing sitter too, as she appears on the same fur-covered bench in two pictures both entitled Quiet (c. 1881), the larger of which was exhibited by Tissot at the Royal Academy in 1882. The other is an upright version of the present composition measuring 12 ½ x 8 ½ in., sold at Christie’s on 5 November 1993, lot 159 (now in The Lloyd Webber Collection), but it instead depicts Lily cheekily turned towards the artist, distracted from her story, and peering over the garden bench. The present picture is a more tranquil and satisfying composition, with the sun-filled lawn, distant pond and dappled light filtering through the leaves of the chestnut tree.

Since the rejection of some of Tissot’s submissions to the Royal Academy in 1875, he had changed marketing tactics and showed more paintings outside London, where there was considerable demand from provincial dealers and new municipal galleries. Small paintings and prints were more easily accommodated and sold, as well as being more transportable. Such was the case with The Tale, exhibited in Birmingham and Liverpool in 1880 and 1882 respectively. When it was exhibited in Birmingham, The Tale was described by the Birmingham Daily Post’s art critic as ‘a work of very high merit. It is a tiny canvas, but there is breadth of treatment in it.’ In fact, the painting is on a thin mahogany panel, a support that Tissot favored for his small London-made pictures. Onto a lead-white ground that gave luminosity (and was used for this reason by both Impressionist and Pre-Raphaelite painters), Tissot laid broad diagonal brushstrokes of warm brown to create mid-tones and to animate the surface. This under-layer can be seen in places, especially beneath the lawn. Tissot’s use of vivid colors for the grass and leaves is radically modern: he mixed brilliant Emerald and Viridian Green with dazzling Barium Chromate and Strontium Yellow, poisonous paints that Vincent van Gogh also liked for their striking freshness. They certainly helped Tissot’s pictures stand out from the dense crowd of other works on gallery walls. Alongside this modernism, Tissot’s technique was grounded in tradition. His stunning fluency with the brush enabled him to capture glints of sunlight on hair and clothes, details of ribbons and folds, Kathleen Newton’s earring, and the delicate profiles of young woman and child. It is such eloquent and beautiful detail that made, and continues to make, Tissot’s work so attractive to viewers and collectors.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

@dahliaborne ‘s 2020 spring/summer tag game (also tagged by @vladadoll & @kaafka thank you darlings 🖤)

what songs captures the essence of your ideal s/s mood?

Bleed, Honey by Honey Gentry / Falling in Love by Cigarettes after sex / Daydreaming by Radiohead / Cloudbusting by Wild Nothing / Pearls by Coals / Cherry coloured-funk by Cocteau Twins / Lillies by Bat For Lashes / Queen of Peace by Florence + The Machine

(none of these songs fit together really/quite random, but oh well djdjdd)

imagine yourself as a persephonesque creature, a nymph, what would be your s/s epithet(s)?

of the pearlescent heart, overgrown with melancholy

what do you plan to read this s/s?

- Perfume: The Story of a Murderer by Patrick Süskind

- Psyche in a Dress by Francesca Lia Block

- The Penelopiad by Margaret Atwood

flowers you would decorate yourself with?

- roses

- camellia

- rhododendron

- lilies

- baby’s breath

- bleeding heart

- lily of the valley

art pieces that is in the same aesthetic line with your s/s aspirations?

- Summer by Edouard Bisson

- Spring by James Jacques Joseph Tissot

- “Love, Faith, Hope” by Andrea Zanatelli

fruits you would like to delight with?

- strawberries

- cherries

- pomegranates

- pink lady apples

- figs

gems & minerals you would like to fill your seashell with?

- rose quartz

- moonstone

- pearl

- moss agate

I tag: (sorry if you’ve already done it angels) @sirenoirs @nightmare @ivacevic @saccarinee @aiglantine @bisousmiumiu @nehmesis @cutecultleader @sweet-voiced @melethrille @la-petitefille @sulfade @girlange @whothehellisbella

74 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Shedding a single mascara tear in honor of The Hills reboot.

“Singing in the Rain,” 1950 (negative); 1970 (print), by Barbara Morgan © The Barbara Morgan Archive

“Portrait of Miss L…, or A Door Must Be Either Open or Shut,” 1876, by James-Jacques-Joseph Tissot

“Transparency: Clip-o-matic Lips,” 1967, by Joe Tilson

“After-Prom: Adrien’s Big Splash,” 2009 (negative); 2010 (print), by Martine Fougeron

“Mother and Child II,” 1941, by Jacques Lipchitz © The Estate of Jacques Lipchitz, courtesy Marlborough Gallery, New York

“Saint Mary Magdalene,” around 1522–24, workshop of Luca Signorelli

“Woman Holding a Love Letter which Floats about her Enchanted by the Moon,” 1889 (Meiji period, 1868–1912), by Tsukioka Yoshitoshi

#The Hills#Unwritten#natasha bedingfield#lyrics#art#art museum#museum#art history#history#Philadelphia Museum of Art#Philadelphia art museum#Philadelphia#Philly museum of art#Philly art museum#Philly

97 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Brow of the Hill Near Nazareth, 1886-1894 James Jacques Joseph Tissot, 1836-1902

St. Paul’s Bulletin Art Reflection for the Fourth Sunday after Epiphany, February 3, 2019

Growing up, I was given the gift of a relationship with the work of British comedy troupe Monty Python. With parents who were fans, I can remember watching their work from a relatively young age. One of my favorite scenes from their 1979 film Life of Brian is a moment when the titular character, who experiences a life parallel to Jesus’ in the Gospels, finds himself playing a prophet to avoid capture by Roman soldiers.

youtube

To maintain his front, he begins to spin platitudes familiar to Christians “Consider the birds…” (Luke 12.24), but he isn’t a particularly gifted orator. The crowd turns on him, really over an issue of poor timing. “Have the birds got jobs!? He says the birds are scrounging!” they say. “He’s having a go at the flowers now!”

Homiletics is a weird business. Congregations give a preacher a block of time to speak about the deepest aspects of faith, life and our world. In scriptural traditions, part of that work is to explicate and contemporize passages of holy text. It’s a holy responsibility and trust, but it’s fraught with Life of Brian-esque danger as well.

As a preacher, it’s helpful to hear/see Jesus getting some sermon feedback. This week we see Jesus give his first a sermon: “I’m the fulfillment of Isaiah’s promise,” he says to the people of his home synagogue. They respond: “Wait… don’t we know this guy? Maybe we can get some special treatment!” Which reminds me of another Life of Brian moment…

youtube

Jesus has some thoughts: “I’m not here exclusively for you. Just like the prophets Elijah and Elisha, my ministry is to others.”

In our bulletin art, French realist James Jacques Joseph Tissot illustrates what happens next: “When they heard this, all in the synagogue were filled with rage. They got up, drove him out of the town, and led him to the brow of the hill on which their town was built, so that they might hurl him off the cliff.” (Luke 4.28-29)

What a mess! I love how confused Tissot’s interpretation is . . . you can’t even see where Jesus is! It’s like a Where’s Waldo puzzle! (I still haven’t found him!) Tissot’s visualization is helpful to me because it shows me how the ultimate resolution might have happened: “But he passed through the midst of them and went on his way.” (Luke 4.30) They are so incensed that Jesus is able to blend in and leave town.

In ministry we get much more feedback on our homiletical work than anything else. I appreciate your thoughts, especially when you are challenged. The Gospel is difficult and Jesus’ claims to be the fulfillment of scripture are as hard now as they ever were. If you’re not being poked and prodded, I’m not doing my job.

Still, I am glad that we haven’t yet found ourselves on top of Manhattan Hill on a Sunday morning . . .

1 note

·

View note

Photo

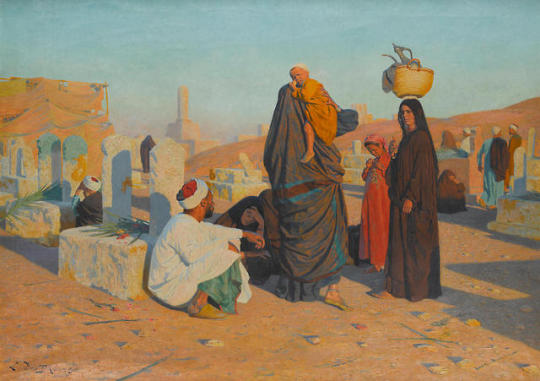

Ludwig Deutsch (Austrian, 1855-1935)

Early morning, Id el-fitr

signed, inscribed and dated 'L. Deutsch Le Caire 1902' (lower left)

Despite the startling clarity of his pictures, the details of Ludwig Deutsch's life remain elusive and vague. Brought up in Vienna, he studied at the Akademie der Bildenden Künste before moving to Paris in 1878. There he befriended several Orientalist artists, including Arthur von Ferraris, Jean Discart, and his lifelong friend Rudolf Ernst. It is likely that he studied with the French history painter Jean-Paul Laurens prior to his participation in the Société des Artistes Français from 1879 to 1925; his other instructors and mentors, however, are unknown. (Deutsch's first Orientalist works appeared in 1881, well before his inaugural trip to Egypt and the Middle East. It is possible that he was influenced early on in Paris by the widely circulating pictures of Jean-Léon Gérôme.) In 1898, Deutsch earned an honorable mention at the Société's annual Salon, and, in 1900, just two years before the present work was painted, he was awarded a gold medal at the Exposition Universelle. Later, having established himself as the center of an entire school of Austrian Orientalist painting, he would receive the Chevalier de la Légion d'Honneur. In 1919, Deutsch gained French citizenship and, after a brief absence, began exhibiting again under the name "Louis Deutsch." (It is assumed that Deutsch left France during the First World War due to the official hostilities between France and the Austro-Hungarian Empire. He may also have ventured to North Africa at this time.) In an effort to stay current and revive what was now a waning genre, Deutsch's technique in the years after 1910 began to change; his late pictures hovered between the highly detailed, polished surfaces for which he – and several other Orientalist painters – had become renowned, and the looser brushwork and more highly keyed palette of Post-Impressionism.

Throughout this long and varied career, Deutsch consciously avoided the picturesque and anecdotal qualities that marked so many contemporary Orientalist works, and chose instead a far broader and more modern approach. Drawing from all aspects of Middle Eastern life – especially Egyptian – and isolating and scrutinizing particular moments in time, Deutsch's paintings are today seen as verging on the cinematic, with all the spectacular and static qualities of a promotional film still. (Deutsch's process may again have been partially indebted to the works of Gérôme, whose own paintings were often marked by both high drama and a chilling frigidity.) His intensely detailed series of guard or sentinel pictures (one of which, The Nubian Guard [private collection], was completed in this same year), bazaar scenes, and images of the local literati were facilitated by an enormous collection of photographs amassed in Cairo, many of them purchased from the well-known studio of G. Lékégian. (Deutsch also acquired hundreds of decorative objets while abroad, which furnished both his Paris studio at 11 rue Navarin and the Orientalist pictures he produced there. The tombak, or ewer, in the present work, for example, placed in a basket atop the woman's head, was a favorite and oft-repeated souvenir.)

The subject of Early Morning, 'Id el-fitr, though less common in Deutsch's oeuvre, was a familiar one in the nineteenth century, in both literature and art.1. Writing in 1885, Thomas Patrick Hughes offered the following description of the events that took place on this religious holiday, including the rituals that Deutsch refers to here:

On one or more days of this festival [" 'Idu 'L-Fitr"], some or all of the members of most families, but chiefly the women, visit the tombs of their relatives. This they also do on the occasion of the other grand festival. ["Idu 'l-Azha"] The visitors, or their servants, carry palm branches2, and sometimes sweet basil, to lay upon the tomb which they go to visit. The palm-branch is broken into several pieces, and these, or the leaves only, are placed on the tomb. Numerous groups of women are seen on these occasions, bearing palm-branches, on their way to the cemeteries in the neighborhood of the metropolis. They are also provided, according to their circumstances, with cakes, bread, dates, or some other kind of food, to distribute to the poor who resort to the burial-ground on these days. Sometimes tents are pitched for them; the tents surround the tombs which is the object of the visit.3

In addition to Hughes' concise account, Deutsch would have had many other sources from which to draw. His personal library included several volumes detailing the intricacies of Egyptian culture, many of them illustrated by his compatriots and peers. Indeed, the drawings by Leopold Carl Müller (1834-1892) in Georg Ebers' Egypt: Descriptive, Historical, and Picturesque, published in German in 1878 and translated into English a few years after, may have inspired aspects of Deutsch's composition4. So too, contemporary photographs and popular illustrated newspapers – often used by Deutsch as references for his paintings - may have aided the artist in the creation of this image, either directly or in mood 5 (Fig. 1). Unique to Deutsch, however, are the brilliant color scheme (note how the red of the young girl's dress is mirrored by the close-fitting caps of the seated men and the rose petals strewn along the ground) and the subtle symbolism of the scene. The fragility of the flowers (a common adornment for tombs during special ceremonies) may be meant as a reminder of the brevity of life and, in the juxtaposition of Arab children and well-worn tombstones, the continuity of Egyptian culture and the circle of life are pointedly suggested. Deutsch's interest in the distinctive form of the Arab tomb and tombstone may be gauged by the repetition of the motif in another important painting of the period. The enduring popularity of such subjects among his contemporaries, moreover, extended far beyond Deutsch's adopted Parisian home; the present work was acquired in Cairo more than a decade after it was painted, perhaps during Deutsch's return to the region during World War I.

We are grateful to Emily M. Weeks, Ph.D., for writing this cataloguing note.

1 'Id el-fitr, or "feast to break the fast," is an important annual Muslim holiday marking the end of Ramadan. On this festive day, a celebratory meal is had, ending the month-long period of fasting. The sheer number of cemetery (Arabic, maqbara) scenes in Orientalist art is striking: Jean-Léon Gérôme, Carl Haag (1820-1915), William James Müller (1812-1845), and Amedeo Preziosi (1816-1882) were just a few of the many artists who tackled this subject. In these works, Shaykh's tombs are often prominently featured, the domed silhouettes of which provide much architectural interest. Though not made the focus of the composition, in the middle of Deutsch's picture, in the distant background, the dome of one such structure may be discerned. 2 Palm branches were richly significant in Islamic culture; in ancient Egypt they symbolized immortality. Their presence in this exotic image would have brought a sense of familiarity to European Christian viewers, for whom palms also held special meaning. 3 Thomas Patrick Hughes, A Dictionary of Islam, London, 1885, p. 196. 4 Ebers (1837-1898) was a German archaeologist and novelist. Müller would contribute several illustrations to various editions of his book beginning in 1878. Perhaps the most influential publications for Orientalist artists during the nineteenth century were Edward William Lane's An Account of the Manners and Customs of the Modern Egyptians (London, 1836) and Owen Jones's The Grammar of Ornament (London, 1856). Deutsch is known to have referenced both of these in the details and subjects of his compositions. (In Lane's volume, an image of an Arab tomb and tombstone is included [p. 524], along with a detailed description of its structure and use [p. 522].) 5 There were numerous cemeteries in and around Cairo which Deutsch may have visited or known and referenced here. Among the most widely photographed and illustrated were the Arab cemetery near the Bâb en-Naṣr and the "Southern Cemetery," or Qarafa, extending south of the Citadel near the mosque of Ibn Tulun. The sobriety of Deutsch's composition would have been shared by members of the Orientalist community at this time: 1902 saw the deaths of James Jacques Joseph Tissot (1836-1902) and Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant (1845-1902), and Frederick Goodall (1822-1904) declared bankruptcy in this year.

42 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Phillip Medhurst presents 276/788 James Tissot Bible c 1899 Women of Ziklag taken into captivity 1 Samuel 30:2 Jewish Museum New York. By a follower of (James) Jacques-Joseph Tissot, French, 1836-1902. Gouache on board. The paintings were reproduced in "La Sainte Bible : Ancien Testament . . . / Compositions par J.-James Tissot"; with preface by A. D. Sertillanges. 2 vols. 40 plates; 360 illustrations to text. Paris: M. de Brunoff & Cie, 1904. Based on his surviving pen and ink sketches, Illustration was completed after Tissot's death in 1902 by Henri Bellery-Desfontaines, Auguste François Gorguet, Charles Hoffbauer, Louis van Parys, Michel Simonidy and British artist G. Scott.

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Phillip Medhurst presents 259/788 James Tissot Bible c 1899 David takes the head of Goliath to Saul at Jerusalem 1 Samuel 18:1 Jewish Museum New York. By a follower of (James) Jacques-Joseph Tissot, French, 1836-1902. Gouache on board. The paintings were reproduced in "La Sainte Bible : Ancien Testament . . . / Compositions par J.-James Tissot"; with preface by A. D. Sertillanges. 2 vols. 40 plates; 360 illustrations to text. Paris: M. de Brunoff & Cie, 1904. Illustration was completed after Tissot's death in 1902 by Henri Bellery-Desfontaines, Auguste François Gorguet, Charles Hoffbauer, Louis van Parys, Michel Simonidy and British artist G. Scott.

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Phillip Medhurst presents 152/392 The Primacy of Peter Matthew 16:13-20 the James Tissot Jesus c 1896. By (James) Jacques-Joseph Tissot, French, 1836-1902. After a painting now in the Brooklyn Museum, New York; photogravure from “La Vie de Notre Seigneur Jésus Christ … . avec des notes et des dessins explicatifs par J. James Tissot” 1896-97.

#tissot#james tissot#bible#gospel#jesus#jesus christ#saint peter#Cephas#primacy#the papacy#keys of the kingdom

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Hide and Seek, detail (c.1877). James Jacques Joseph Tissot (French, 1836-1902). Oil on wood. National Gallery of Art.

After Kathleen Newton entered his home in about 1876, Tissot focused almost exclusively on intimate, anecdotal descriptions of the activities of the secluded suburban household, depicting an idyllic world tinged by a melancholy awareness of the illness that would lead to her death in 1882. The artist's companion reads in a corner as her nieces and daughter amuse themselves.

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gallery Visit Week

It was gallery visit week this week and I decided to go to Leeds Art Gallery as I have never been before. After exploring the gallery and pondering the various works I found most interested by a painting ‘The Bridesmaid’ by James Jacques Joseph Tissot and I have decided this is the painting I am going to focus on for my own project and my final painting. There are a lot of interesting aspects to this piece I could explore, particularly with that of the various things happening around the piece and the various people which you only notice more of when you actually look closely and analyse the piece. I also feel it will be interesting to explore the use of the colour blue as it feels significant in the painting the way it is used for the woman’s dress as a way of making the her stand out even more in the centre. Everyone else in the piece wears dark and neutral tones which almost blend together into the surroundings. What if this stand out blue colour was used in other areas of the painting or on other people? What if the blue is taken away altogether or the painting became monochromatic?

0 notes

Photo

Croquet James Tissot c. 1878 Jacques Joseph Tissot, anglicized as James Tissot, was a French painter and illustrator. He was a successful painter of Paris society before moving to London in 1871. He became famous as a genre painter of fashionably dressed women shown in various scenes of everyday life. He also painted scenes and characters from the Bible, mostly early in his career before moving to London, and late in his career after returning to Paris. After moving to London, Tissot quickly developed his reputation as a painter of elegantly dressed women shown in scenes of fashionable life. By 1872, Tissot bought a house in St John's Wood, an area of London very popular with artists at the time. Paintings by Tissot appealed greatly to wealthy British industrialists during the second half of the 19th century, and his own fortunes rose with those of his clients. Like Monet and other contemporaries, Tissot also explored japonisme, including Japanese objects and costumes in his pictures and expressing style influence. Degas painted a portrait of Tissot sitting below a Japanese screen hanging on the wall. In 1875 or '76, Tissot met Kathleen Newton, a divorcee who became the painter's companion and frequent model. She gave birth to his son, moved into Tissot's house, and lived with him until her death in 1882 at only 28 years of age. Tissot frequently referred to these years with Newton as the happiest of his life, a time when he was able to live out his dream of a family life. After Newton's death, Tissot returned to Paris, experienced a religious revival and eventually toured the Middle East to paint an extraordinary number of Biblical images. Widespread use of his illustrations in literature and slides continued after his death with The Life of Christ and The Old Testament becoming "the definitive Bible images." Somewhat surprisingly, Tissot's images provided a foundation for contemporary films such as Raiders of the Lost Ark and The Age of Innocence (1993).

0 notes

Photo

Phillip Medhurst presents 274/788 James Tissot Bible c 1899 David returns to Achish 1 Samuel 27:9 Jewish Museum New York. By a follower of (James) Jacques-Joseph Tissot, French, 1836-1902. Gouache on board. The paintings were reproduced in "La Sainte Bible : Ancien Testament . . . / Compositions par J.-James Tissot"; with preface by A. D. Sertillanges. 2 vols. 40 plates; 360 illustrations to text. Paris: M. de Brunoff & Cie, 1904. Based on his surviving pen and ink sketches, Illustration was completed after Tissot's death in 1902 by Henri Bellery-Desfontaines, Auguste François Gorguet, Charles Hoffbauer, Louis van Parys, Michel Simonidy and British artist G. Scott.

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Phillip Medhurst presents 257/788 James Tissot Bible c 1899 David cuts off the head of Goliath 1 Samuel 17:51 Jewish Museum New York. By a follower of (James) Jacques-Joseph Tissot, French, 1836-1902. Gouache on board. The paintings were reproduced in "La Sainte Bible : Ancien Testament . . . / Compositions par J.-James Tissot"; with preface by A. D. Sertillanges. 2 vols. 40 plates; 360 illustrations to text. Paris: M. de Brunoff & Cie, 1904. Illustration was completed after Tissot's death in 1902 by Henri Bellery-Desfontaines, Auguste François Gorguet, Charles Hoffbauer, Louis van Parys, Michel Simonidy and British artist G. Scott.

13 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Phillip Medhurst presents 267/788 James Tissot Bible c 1899 Saul commands Doeg to slay the priests 1 Samuel 22:18 Jewish Museum New York. By a follower of (James) Jacques-Joseph Tissot, French, 1836-1902. Gouache on board. The paintings were reproduced in "La Sainte Bible : Ancien Testament . . . / Compositions par J.-James Tissot"; with preface by A. D. Sertillanges. 2 vols. 40 plates; 360 illustrations to text. Paris: M. de Brunoff & Cie, 1904. Based on his surviving pen and ink sketches, Illustration was completed after Tissot's death in 1902 by Henri Bellery-Desfontaines, Auguste François Gorguet, Charles Hoffbauer, Louis van Parys, Michel Simonidy and British artist G. Scott.

6 notes

·

View notes