#jacques rivette essay

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

LA BELLE NOISEUSE - (Jacques Rivette, 1991)

A painter in creative crisis is stimulated by the arrival of a beautiful woman to ask her to pose as a model for a painting (dedicated to his young wife) that he had interrupted many years before... (I stop here). The movie is a kind of filmed literary essay (in fact it was inspired by a story by Balzac) about the various difficulties inherent the artistic creation, the risks hidden in the process, the absolute availability that it requires and the magic it hides (the vision of the finished picture - that the viewer will never see - reveals to Marianne something of herself that was unknown to her and puts her love relationship in crisis). But, the most relevant thing about the film, is how the creation of the painting starts an unresolved series of cross-confrontations (painter vs model, painter vs wife, model vs boyfriend, boyfriend vs art dealer, art dealer vs painter) all built as "will comparisons" where everyone wants to dominate the other, risking being in turn dominated. Great actor performances by Michel Piccoli, Jane Birkin and Emmanuelle Béart who must (happily for us) act naked for most of the film.

r.m.

R.M.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Difference and Repetition: The Filmmaking of Marguerite Duras

Though best known as a novelist, Marguerite Duras pursued a unique filmmaking career of upending expectations.

Lawrence Garcia 08 SEP 2020

MUBI's series Hypnotic Incantations: A Marguerite Duras Focus is showing September - October, 2020 in the United Kingdom and United States.

In 1955, Jacques Rivette famously wrote that Roberto Rossellini’s Voyage to Italy“opens a breach… that all cinema, on pain of death, must pass through.” For Rivette and many others, the film heralded nothing less than the arrival of a modern cinema—and not five years later, Alain Resnais, with a screenplay from Marguerite Duras, took up this challenge with Hiroshima mon amour (1959). Following the film’s seismic premiere, Eric Rohmer declared it either “the most important film since the war” or “the first modern film of sound cinema,” its overture of tangled, ash-covered limbs even echoing the embalmed couple Ingrid Bergman turns away from in Voyage to Italy’s memorable Pompeii-set passage. With her seminal script, Duras could thus claim to have widened the gap opened by Rossellini, readying the space through which her own cinematic practice would later glide. But in the end, perhaps the challenge of Voyage to Italy was, at least for her, no more than the challenge of writing itself. In her memoir-cum-essay “Écrire,” composed three years before her death in 1996, she speaks movingly of the solitude of writing, its silent scream, but also its singular inducements: “Writing was the only thing that populated my life and made it magic. I did it. Writing never left me.”

And indeed it didn’t—neither through the numerous books published during her lifetime, nor through the roughly 20 films she made from the late ’60s to the early ’80s. That Duras’s directorial reputation still lags behind her literary fame is undeniable, and the sight-gag in John Waters’s 1981 Polyester, of an American drive-in showing “Three Marguerite Duras Hits,” plays about just as well today. But rather than the proliferation of Durases that have emerged in sundry biographical/critical treatments of the artist—she is by turns “unintelligible,” “narcissistic,” “difficult,” and “obscure”—her cinema has gained the stature of an unapproachable edifice, forbidding and remote. An unfortunate state of affairs for an artist so gripped by, as she herself put it, the perpetual desire “to tear what has gone before to pieces.” Destroy, She Said, her fourteenth novel and second feature, both released in 1969, emerged for her from “the idea of a book… that could be either read or acted or filmed or... simply thrown away.” The conceptual pivot of both versions, set in a rural hotel that’s something more like a sanitarium, is a phony card game used as a vehicle for interrogation and entrapment of one of the players; as always with Duras, the rules of the game are never quite clear at the outset. But echoing the final scene of Blow-Up (1966), it is the periodic sounds of a tennis match—heard but not seen, and commented on throughout the novel/film—which lay the groundwork for the plays with image and sound that recur through the films of hers that followed.

“I don’t think the image can ever replace what I called ‘the indefinite proliferation’ of the word,” she declared to Jean-Luc Godard in one of their three conversations on the twined subjects of son et image (spanning 1979–1987 and subsequently collected into the volume Duras / Godard Dialogues). But just as the New Wave icon’s work would continue to grapple with such questions—his disorienting, staccato bursts of image/sound would intensify in the ’80s, beginning with Every Man For Himself, in which Duras can be heard but not seen—Duras’s own oeuvre, through rather different means, sought to challenge preconceptions and overturn cinematic orthodoxies. Destroy, she said—and so she did, continually questioning received filmmaking methods, and through a kind of discovery by dissolution, conceiving of how things might be otherwise. Likewise, her most famous novel, the Prix Goncourt–winning The Lover (1984), speaks to the “indefinite proliferation of the word” mainly in terms of difference, its autobiographical scenario having been treated previously in The Sea Wall (1950) and later in L’amant de la Chine du nord(1991). Fittingly perhaps, The Lover (whose sundry editions place the photo of a young Duras on their covers), offers up a particularly intriguing coinage not in its finished form, but in the working title of one of its manuscripts: “La photo absolue” (or the absolute photograph). The discarded phrase gives name to a notion—possibly illusory—from which Duras’s practice, with its penchant for repetition and revision, charts its own course of difference.

Above: Baxter, Vera Baxter (1977)

The nautical metaphor is not incidental, for the allure of the sea recurs time and time again across her cinema. It is there amid the Marxist musings of Le camion(1977) and the death-obsessed dolor of L’homme atlantique (1981), though between the two it crests in Baxter, Vera Baxter (1977), where a tale of sexual jealousy and dependence becomes as if subsumed into the Atlantic, its glimmering immensity glimpsed in a series of liberating cuts away from the film’s glass-enclosed, terrarium-like interiors. Like many a seafaring raconteur, Duras favors the directness of speech—implicitly or explicitly, her films often take the form of a dialogue. The great difference is her willingness to futz with the usual hierarchies of image and sound: To step into her films, with their perpetual enfolding of narrative necessity, visual-aural abstraction, and sensorial impact, is to be set adrift in conflicting currents of obsessive prose and measured movement. An experience not entirely unlike attempting to converse with the ocean.

It is easy to lose oneself in the resultant flux. So alongside Godardian strategies of sensorial bombardment, we might well speak of Durassian drift. Her gliding camera in the first half-hour of Le Navire Night (1979), a film comprised largely of exchanges between Duras and then-apprentice Benoît Jacquot, is enough to demolish any lingering preconceptions of her directorial austerity. The film’s challenge is not so much an arid aesthetic of alienation, but a bewildering multiplicity of sensuous attractions and compulsive mysteries, here centered on the ambiguous relationship between a dying young girl and a man she knows only through a series of intimate phone calls. By the end, one has to sort through a set of nullities: between the absences and gaps of ultimately no consequence at all, and the voids around which one might center an entire existence.

So it goes too with the spectral spaces of her most celebrated feature, India Song(1975), starring Delphine Seyrig as the wife of the French ambassador in a Calcutta of the colonial imagination (shot in the Château Rothschild in Versailles). The film’s narrative framework had been laid in her previous novels The Ravishing of Lol Stein(1964) and The Vice-Consul (1966), though from the cinema, there is also Orson Welles’s The Immortal Story (1968), with its particular, perverse interplay of material decadence, sexual domination, and stories told under the sway of the sea. For India Song’s entirely asynchronous soundtrack, though, filled in mainly by the composer Carlos d’Alessio (one of Duras’s closest collaborators), one has to look forward to something like Wong Kar-wai’s In the Mood for Love (2000), which likewise draws the viewer into a dispersed atmosphere of lush sorrow, and pushes its story scaffolding to extremes of aural detachment and spatial alienation. It is between these poles, in the dead heart of India Song, that one finds an earlier instance of la photo absolue: a framed portrait sitting atop a grand piano, and the point about which the film’s currents of desire eddy and swirl. Behind it, a mirror spanning the height of the wall. At the far end, an unused fireplace; to its right, a staircase. At the zenith, a crystal chandelier. At the nadir, a supine body—languid, lusty, and lacquered in sweat.

Above: India Song (1975)

Before it was a film, India Song existed as a play (commissioned by the National Theater in London in 1972, albeit never staged), an act of artistic doubling that was, for Duras, far from exceptional. (Le Navire Night opened on the stage the same week the film version was released in cinemas, while Baxter, Vera Baxter preceded the publication of Vera Baxter ou les Plages de l’Atlantique.) But whereas this cross-media tendency might, for some, have signaled some implosive synthesis of various art forms, what it revealed in Duras’s hands was the sticky stubbornness of medium specificity. If anything, these myriad excursions from page to screen to stage only made her more acutely aware of the indissoluble boundaries between each. There’s no precise analogue in cinema for the declarations of “silence” that recur like timed explosions throughout Duras’s writing, and there’s likewise no corollary in literature for the ceaseless celebratory thrum of the music that echoes throughout the near-entirety of Baxter, Vera Baxter, bringing to mind images of a pre-colonial paradise lost. Seyrig’s character calls the music an “exterior turbulence,” and apparently wary of the avowed certainties of her age, Duras seemed intent on seeking out or indeed creating such disturbances—in cinema and literature both.

Given her prolificity and predilection for creative destruction, any attempt to encapsulate Duras’s cinematic sensibility can seem counterproductive. But at the risk of bringing in an even more ill-defined concept, it should be said that her practice shares something with the essay film. There are certainly worse ways to describe Duras’s work than with Jean-Pierre Gorin’s definition of the film-essay as “the meandering of an intelligence that tries to multiply the entries and the exits into the material it has elected (or has been elected by). It is surplus, drifts, ruptures, ellipses, and double-backs.” Not the most conventional of artists, Duras often dispensed with explicit argumentative frameworks, even in her written essays. But if her works nonetheless manage to persuade or convince, to challenge or affirm, it is through the coiled force of their assertions, their apparent disregard for established pieties, and their perpetual drive to decenter and upend expectations. Unafraid to scavenge and repurpose, to reimagine and reinvent, she cycled through familiar memories and anecdotes and twice-treated tales, unabashed about producing works that might be considered adjunct, subsidiary, or otherwise incomplete. Which is to say that she did in the open what most artists do in secret. You could dismiss the results as mere exercises in style—but as in the case of fellow French literary giant Raymond Queneau, whom Duras famously interviewed in 1959, and with whom she shared a taste for judicious repetition, to do so would be to miss the distinctive, enduring appeal of her art.

By the 1980s, her work in cinema was all but behind her—perhaps due to a general disillusion with the form (the Durassian paradox, per Jacquot: “She detested cinema but adored making films”), though more likely, her deteriorating health and alcoholism made the physical demands of the camera impossible. At the nadir, a supine body, hospitalized in 1982 for disintoxication treatment. At the zenith, the Prix Goncourt and renewed international acclaim.

Towards the close of Le Navire Night, after the narrative proper (insofar as one exists) has concluded, Duras and Jacquot continue to converse on—what else?—the sea, and then on an uncompleted film, its creation stopped by death or by doubt. Certainly, Duras doubted many things before her death: the cinema, the fixity of the completed work, perhaps even the very notion of completion. But for a time, at least, the act of filmmaking remained—over nearly two decades, she picked up the camera again and again and again, finding worlds of difference with each repetition. For the cinema that she so doubted, that repetition made all the difference.

Above: Le Navire Night (1979)

1 note

·

View note

Text

The topic that I have for the blog assignment is the French New Wave of Cinema. In the picture above are some popular films that influenced the film movement. So what exactly was the French New Wave? It was a film movement that rose to popularity in the late 1950s in Paris, France. The idea was to give directors full creative control over their work, allowing them to favor improvisational storytelling instead of strict narratives. In Alexandre Astruc's manifesto he writes "cinema was in the process of becoming a new means of expression on the same level as painting and the novel...This is why I would like to call this new age of cinema the age of the caméra-stylo." This essay inspired many French filmmakers to start experimenting with new ideas of how we should shoot and view cinema. These new filmmakers such as Jean-Luc Godard, Agnès Varda, Éric Rohmer, Jacques Rivette, and Claude Chabrol wanted to experiment with film form and style but didn't have the budgets to do it. Instead of trying to find the money to get high level gear and equipment they decided to use portable equipment to have a run-and-gun style. This led to a unique style of film that had fragmented, discontinuous editing, and long takes that allowed actors to explore a scene. The combination of realism and commentary allowed these movies to have unique characters, motives, and even endings that were not so clear-cut. When it comes to these French new wave films, some recognizable characteristics stick out and signify which movies fall into the New Wave category. The main one is the rejection of classical filmmaking, with a focus on experimental and/or avant-garde techniques. These films also featured existential themes that were in direct contrast to what film was doing previously with the Hollywood golden era. These films wanted to showcase the individual and the chaos of human existence. So what did these films mean for the rest of the world? Even after the movies stopped being made, it inspired many other international movements including the New Hollywood era. You can see these influences across Woody Allen, Spike Lee, and even in the mumblecore films of the 90s and 2000s. To summarize, at the movement's heart was the idea that anyone should be able to make a movie, and that sentiment has lived on today. Overall this new film design led to many interesting and artistic films that still hold up today.

Source used: https://nofilmschool.com/what-is-the-french-new-wave

0 notes

Text

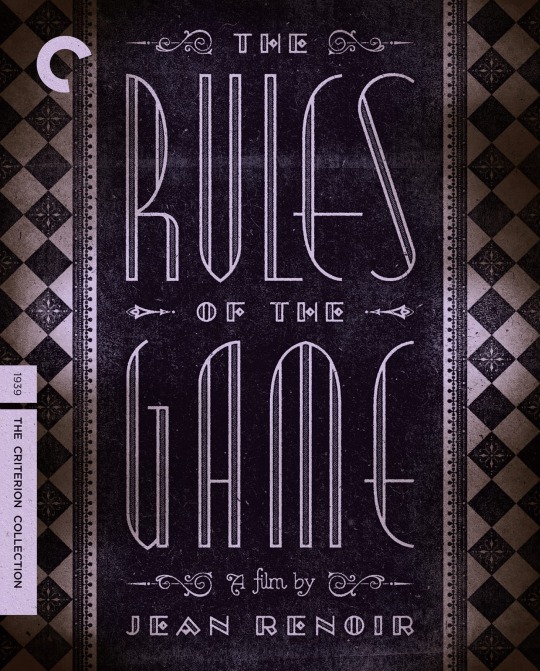

On June 6th, the @criterioncollection is releasing a 4K uhd-blu-ray upgrade of the all time classic Rules of the Game - with an first time new cover (see above):

The Rules of the Game

Considered one of the greatest films ever made, Jean Renoir’s The Rules of the Game is a scathing critique of corrupt French society cloaked in a comedy of manners in which a weekend at a marquis’s country château lays bare some ugly truths about a group of haut bourgeois acquaintances. The film has had a tumultuous history: it was subjected to cuts after the violent response of the audience at its 1939 premiere, and the original negative was destroyed during World War II; it wasn’t reconstructed until 1959. That version, which has stunned viewers for decades, is presented here.

4K UHD + BLU-RAY SPECIAL EDITION FEATURES

New 4K restoration, with uncompressed monaural soundtrack

One 4K UHD disc of the film and one Blu-ray of the film with special features

Introduction to the film by director Jean Renoir

Audio commentary written by film scholar Alexander Sesonske and read by filmmaker Peter Bogdanovich

Comparison of the film’s two endings

Selected-scene analysis by Renoir historian Chris Faulkner

Excerpts from a 1966 French television program by filmmaker Jacques Rivette

Part one of Jean Renoir, a two-part 1993 documentary by film critic David Thompson

Video essay about the film’s production, release, and 1959 reconstruction

Interview with film critic Olivier Curchod

Interview from a 1965 episode of the French television series Les écrans de la ville with Jean Gaborit and Jacques Durand

Interviews with set designer Max Douy; Renoir’s son, Alain; and actor Mila Parély

PLUS: An essay by Sesonske; writings by Jean Renoir, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Bertrand Tavernier, and François Truffaut; and tributes to the film by J. Hoberman, Kent Jones, Paul Schrader, Wim Wenders, Robert Altman, and others

New cover by Raphael Geroni

1 note

·

View note

Text

Cartographic Time In Jacques Rivette’s La Pond Du Nord

Cartographic Time In Jacques Rivette’s La Pond Du Nord

In 1946, Jorge Luis Borges published the micro-short story, On Exactitude In Science. The piece is a fictionalised fragment, supposedly taken from Viajes de varones prudentes, Libro IV, Cap. XLV, Lérida, (1658) written by the equally fictional Suárez Miranda. The piece addresses the role of perception in cartography, relying on the irony of mapmakers attempting to make a 1:1 scale map of a place;…

View On WordPress

#Adam Scovell#bulle ogier#Celluloid Wicker Man#jacques rivette#jacques rivette blog#jacques rivette essays#jacques rivette la pont du nord#jacques rivette map#jacques rivette paris#jorge luis borges#jorge luis borges on exactitude in science#la pont du nord#la pont du nord analysis#la pont du nord explained#la pont du nord map#la pont du nord rivette#on exactitude in science#pascale ogier

1 note

·

View note

Video

youtube

Breaking the Rules: The French New Wave (from Channel Criswell)

#cinema#new wave#french new wave#nouvelle vague#cinema history#movies#jean luc godard#francois truffaut#jacques rivette#claude chabrol#editing#essay#video essay#film#film theory#channel criswell#lewis michael bond#lewis bond#cinema cartography

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

"And like the revered New Wave filmmaker she worked with early in her career, Jacques Rivette, Denis is always alive to beauty. Rivette loved looking at women, not lasciviously but with a languorous gaze like a sigh. Denis, working here with her usual cinematographer, the supremely gifted Agnès Godard, lavishes similar love on Binoche: Her skin is like cream with drops of moonlight mixed in. Her face—open and responsive, always receiving signals as well as sending them out—is itself an elegant question." — Stephanie Zacharek in her beautiful essay on Claire Denis’s Let the Sunshine In (2017)

127 notes

·

View notes

Photo

La Belle Noiseuse. D: Jacques Rivette (1991). Michel Piccoli as a legendary artist, blocked for years on a portrait of his wife, who starts to finish it with a woman who is not his wife. The audience watches for nearly four hours as he sketches and she models, and it never looks away.

American Splendor. D: Shari Springer Berman and Robert Pulcini. (2003). Harvey Pekar (Paul Giamatti) starts a great underground comic book career by taking inspiration from everything in his ordinary life – his shit job, his cancer diagnosis – but mostly the passionately mundane love story he shares with his wife, Joyce Brabner (Hope Davis). Every once in awhile the real Harvey and Joyce stop by to see how the actors playing them are doing.

Adaptation. D: Spike Jonze. (2002). Nicolas Cage as a tortured writer whose attempt to adapt an essay by Susan Orleans (Meryl Streep) turns into an abyss of self-hatred and anxiety. Nicolas Cage as his twin brother who doesn’t understand what’s so difficult about this whole writing thing, read an article about it and it doesn’t really seem that hard. Charlie Kaufman’s brilliant script winds up honoring both viewpoints.

Sid and Nancy. D: Alex Cox. (1986) Walking catastrophe Sid Vicious meets screeching apocalypse Nancy Spungen (Chloe Webb who never topped her performance because how could anyone?). She inspires him not to rock and roll glory but to the murder/suicide that became the pathetic and horrible footnote to his life. The saddest funny movie you’ll ever see.

Ed Wood. D: Tim Burton. (1994). Martin Landau as Bela Lugosi, the washed-up junkie who once played and defined the role of Dracula and who jump-starts Wood (Johnny Depp in what is still his best work) to make the Worst Movie of All Time or as he calls it “My Masterpiece.”

#kevrock#muses#artists#ed wood#sid and nancy#adaptation#american splendor#la belle noiseuse#spike jonze#tim burton

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Female Gaze, a two-week survey of 36 films shot by 23 female cinematographers, begins July 26! This series spotlights the amazing work of such accomplished international female cinematographers as Agnès Godard, Natasha Braier, Kirsten Johnson, Joan Churchill, Maryse Alberti, Ellen Kuras, Babette Mangolte, and Rachel Morrison. Laura Mulvey’s landmark 1975 essay “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema” suggested an imbalance of power in film dominated by the male gaze and heterosexual male pleasure; this series poses the question: is there such a thing as the ���Female Gaze”?

This year, Morrison made history as the first woman nominated for the Best Cinematography Oscar for Mudbound, a triumph that also underscored the troubling issue of gender inequality in the film industry. Few jobs on a movie set have been as historically closed to women as that of cinematographer—the persistence of the term “cameraman” says it all. Despite this lack of representation, trailblazing women have left their mark on the field through extraordinary artistry and profound vision. As seen through their eyes, films by directors like Claire Denis, Jacques Rivette, Chantal Akerman, Ryan Coogler, and Lucrecia Martel are immeasurably richer, deeper, and more wondrous.

See the full lineup + schedule.

#cinematography#Agnès Godard#Natasha Braier#Kirsten Johnson#Joan Churchill#Maryse Alberti#Ellen Kuras#Babette Mangolte#Rachel Morrison

173 notes

·

View notes

Photo

THE FILM SOCIETY OF LINCOLN CENTER ANNOUNCES

THE FEMALE GAZE, JULY 27 – AUGUST 9

A two-week survey of 36 films shot by 23 female cinematographers

Agnès Godard, Natasha Braier, Joan Churchill, and Ashley Connor in person

The Film Society of Lincoln Center announces The Female Gaze (July 26 – August 9), spotlighting the amazing work of such accomplished international female cinematographers as Agnès Godard, Natasha Braier, Kirsten Johnson, Joan Churchill, Maryse Alberti, Ellen Kuras, Babette Mangolte, and Rachel Morrison. Laura Mulvey’s landmark 1975 essay “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema” suggested an imbalance of power in film dominated by the male gaze and heterosexual male pleasure; this series poses the question: is there such a thing as the “Female Gaze”?

This year, Morrison made history as the first woman nominated for the Best Cinematography Oscar for Mudbound, a triumph that also underscored the troubling issue of gender inequality in the film industry. Few jobs on a movie set have been as historically closed to women as that of cinematographer—the persistence of the term “cameraman” says it all. Despite this lack of representation, trailblazing women have left their mark on the field through extraordinary artistry and profound vision. As seen through their eyes, films by directors like Claire Denis, Jacques Rivette, Chantal Akerman, Ryan Coogler, and Lucrecia Martel are immeasurably richer, deeper, and more wondrous.

The Female Gaze opens with a double feature of unforgettable collaborations between Agnès Godard and Claire Denis—from the sensual gaze on male bodies in Beau travail to that of familial love in 35 Shots of Rum—launching the series’ central dialogue with Godard in person. Then on July 28, cinematographers Natasha Braier, Ashley Connor, Agnès Godard, and Joan Churchill join Film Society audiences to discuss their careers, experiences in the film industry, and their interpretations of the Female Gaze in a free talk, sponsored by HBO®.

Full line up.

Maryse Alberti Creed Ryan Coogler, USA, 2015, 133m The legend of Rocky lives on as Michael B. Jordan’s gutsy Adonis Johnson—son of Apollo Creed—sets out to prove he’s got what it takes to be the next champ, leaving his luxe L.A. life behind to train in the hard-knock gyms of Philadelphia with the Italian Stallion himself. After the breakout success of Fruitvale Station, director Ryan Coogler shows his facility for major budget spectacle, balancing a rousing underdog sports story with a poignant portrait of intergenerational friendship. The virtuoso lensing of Maryse Alberti astonishes in a dazzling four-and-a-half minute fight sequence that unfolds in one bruising, breathless take. Thursday, August 2, 1:30pm Sunday, August 5, 9:00pm

Velvet Goldmine Todd Haynes, UK/USA, 1998, 35mm, 124m The birth of Oscar Wilde; the staged death of a flamboyant rock star modeled closely after David Bowie; the delirious inebriation of London at the height of the glam era: Haynes’s discourse on celebrity culture is as sprawling and multi-tracked as his previous film, Safe, had been clinically restrained. Much of Velvet Goldmine, the story of a journalist who tries to reconstruct the sordid life story of the failed glam rock star he’d idolized as a young man, was shot in London, and the move gave Haynes a chance to abandon the cloister-like suburbs of his earlier films for a much more colorful, Dionysian milieu. Haynes and cinematographer Maryse Alberti crafted one of the most visually thrilling music movies of the 1990s. An NYFF36 Selection. Sunday, July 29, 8:30pm Tuesday, August 7, 4:15pm

Barbara Alvarez The Headless Woman / La mujer sin cabeza Lucrecia Martel, Argentina/France/Italy/Spain, 2008, 35mm, 87m Spanish with English subtitles DP Barbara Alvarez imparts a restrained—and very strange—spatial texture to Lucrecia Martel’s excitingly splintered third feature, about a woman (a stunning María Onetto) in a state of phenomenological distress following a mysterious road accident. Martel’s rare gift for building social melodrama from sonic and spatial textures, behavioral nuances, and an unerringly brilliant sense of the joys, tensions, and endless reserves of suppressed emotion lurking within the familial structure is here pushed to another level of creative daring. An NYFF46 selection. 35mm print courtesy of UCLA Film & Television Archive. Saturday, July 28, 1:00pm

Akiko Ashizawa Tokyo Sonata Kiyoshi Kurosawa, Japan, 2008, 120m Japanese with English subtitles What strange deceptions lurk beneath the placid veneer of the average Japanese family? Horror maestro Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s unexpected—but wholly rewarding—foray into family melodrama-cum-black comedy quivers with an undercurrent of dread as salaryman dad (Teruyuki Kagawa) loses his job and desperately attempts to maintain the illusion that he’s still employed; his grade-school son (Kai Inowaki) rebels by secretly taking (gasp!) piano lessons; and mom (Kyōko Koizumi) finds what she’s been looking for with her own kidnapper. The elegant long shots of Akiko Ashizawa toy with the meticulous framings of Ozu as Kurosawa guides the film through a series of increasingly audacious tonal shifts. An NYFF46 selection. Tuesday, August 7, 6:45pm

Diane Baratier The Romance of Astrea and Celadon / Les amours d'Astrée et de Céladon Éric Rohmer, France, 2007, 35mm, 109m At the age of 88, Éric Rohmer bid adieu to cinema with this enchanting mythological idyll, which brims with all the vitality and freshness of youth. Frequent Rohmer cinematographer Diane Baratier conjures a sun-dappled bucolic dream vision of fifth-century Gaul, where a beguiling fable of romantic misunderstanding plays out when a band of druids and nymphs intervene in the lovers’ quarrel between androgynously beautiful shepherd Celadon (Andy Gillet) and his jealous paramour Astrea (Stéphanie Crayencour). Introducing hitherto untapped themes of gender and sexual fluidity into his work, Rohmer crafts an exalted paean to love both spiritual and carnal. An NYFF45 selection. Friday, August 3, 2:00pm Thursday, August 9, 7:00pm

Céline Bozon La France Serge Bozon, France, 2007, 35mm, 102m French with English subtitles In the fall of 1917, as World War I rages, a lovelorn soldier’s wife (Sylvie Testud) disguises herself as a man and sets off for the front in search of her missing husband. Along the way, she meets up with a company of soldiers under the command of a gruff lieutenant (Pascal Greggory), who reluctantly allows Camille to join their ranks. From time to time, these surprisingly sensitive, introspective men break out an assortment of homemade instruments and perform original songs written for the film by Benjamin Esdraffo and the artist known as Fugu, styled after the American “sunshine pop” of The Beach Boys and The Mamas and the Papas. Exquisitely shot by Céline Bozon (the director’s sister), this unclassifiable hybrid of war movie and movie musical is truly unlike anything you’ve ever seen before. Print courtesy of the Institut Français. Wednesday, August 1, 6:45pm Wednesday, August 8, 1:30pm

Natasha Braier The Milk of Sorrow / La teta asustada Claudia Llosa, Spain/Peru, 2009, 35mm, 94m Spanish and Quechua with English subtitles Fausta, the only daughter of an aged indigenous Peruvian mother, is said to have been nursed on “the milk of sorrow.” This accursed designation is bestowed on the children of victims of the former terrorist regime. Fausta has learned of her mother’s past and her own presupposed fate through invented song, which is both an art form and oral history tradition. Upon her mother’s death, she must venture beyond the safety of her uncle’s home and choose whether or not to lend her gift of song so that she can pay for a proper burial. Llosa and DP Natasha Braier capture the striking beauty of Lima’s outskirts, as well as a revelatory performance by Magaly Solier, with dignity and grace. Winner of the Golden Bear at the 2009 Berlin Film Festival. A New Directors/New Films 2009 selection. Sunday, July 29, 3:30pm (Q&A with Natasha Braier)

The Neon Demon Nicolas Winding Refn, Denmark/France/USA/UK, 2016, 118m Like a 21st-century Showgirls meets Suspiria, Nicolas Winding Refn’s delirious plunge into the fake plastic horror of the image-obsessed fashion industry trafficks in both high-camp excess and kaleidoscopically stylized splatter. Elle Fanning is the guileless recent L.A. transplant whose fresh-faced youth and beauty almost instantly land her a high-profile modeling contract. Whatever “it” is, she has it. And a coterie of monstrously jealous, flavor-of-last-month Hollyweird burnouts will stop at nothing to get it. Working in a supersaturated, electric day-glo palette, DP Natasha Braier fashions a sleek, freaky-seductive vision of L.A.’s dark side. Saturday, July 28, 8:00pm (Q&A with Natasha Braier)

Caroline Champetier The Gang of Four / La bande des quatre Jacques Rivette, France/Switzerland, 1989, 160m French and Portuguese with English subtitles Four women, a shadowy conspiracy, and a whole lot of acting exercises: we’re firmly in Rivette territory in one of the director’s most spellbinding explorations of the sometimes terrifyingly thin line between everyday life and the strangeness beneath it. A quartet of aspiring actresses live together while studying with a demanding coach (Bulle Ogier). As they rehearse Pierre Marivaux’s La Double inconstance, offstage drama creeps into their lives in the form of a menacing mystery man (Benoît Régent) with a sinister story to tell. Caroline Champetier’s moody lensing—muted reds, golds, and browns—creates the feeling of an all-enveloping universe operating according to its own paranoid logic. Friday, July 27, 3:15pm Wednesday, August 8, 6:15pm

Holy Motors Leos Carax, France, 2012, 116m French and English with English subtitles Cinematographers Caroline Champetier and Yves Cape both lensed this unclassifiable, expansive movie from Leos Carax about a man named Oscar (longtime collaborator Denis Lavant) who inhabits 11 different characters over the course of a single day. This shape-shifter is shuttled from appointment to appointment in Paris in a white-stretch limo driven by the soignée Edith Scob (Eyes Without a Face); not on the itinerary is an unplanned reunion with Kylie Minogue. To summarize the film any further would be to take away some of its magic; the most accurate précis comes from its own creator, who aptly described Holy Motors after its world premiere in Cannes as “a film about a man and the experience of being alive.” An NYFF50 selection. Saturday, August 4, 7:15pm Monday, August 6, 4:00pm

Le Pont du Nord Jacques Rivette, France, 1982, 129m French with English subtitles Paris becomes a labyrinthine life-size game board in one of the most elaborate of Jacques Rivette’s sprawling, down-the-rabbit-hole cine-puzzles. Bulle Ogier and her daughter Pascale star, respectively, as a hitchhiking ex-con and a leather-clad tough girl who meet by chance on the city streets, come into possession of a curious map, and find themselves caught in a sinister cobweb of underworld conspiracy. Shooting seemingly on the fly, almost documentary-style on the streets of Paris, cinematographers Caroline Champetier and William Lubtchansky telegraph a freewheeling, anything-goes sense of play, as well as a creeping surveillance paranoia. An NYFF19 selection. 4K restoration from the 16mm negative, supervised by Véronique Rivette and Caroline Champetier at Digimage Classic, with the help of the CNC. Friday, August 3, 6:30pm

Joan Churchill Aileen: Life and Death of a Serial Killer Nick Broomfield & Joan Churchill, UK/USA, 2004, 93m Just months after Monster made Aileen Wuornos a household name—and Charlize Theron an Oscar darling—documentarian Nick Broomfield and co-director/cinematographer Joan Churchill unleashed this riveting portrait of the real-life serial killer. Of the two films, it remains the more chilling experience, an unflinching face-to-face encounter with a deeply damaged soul who, as she prepares for her imminent execution, is at once eager to set the record straight, angrily defiant, and increasingly delusional. Daring to find the humanity in one of the most vilified criminals of the century, Broomfield and Churchill—whose camera remains ever-alert and skillfully unobtrusive—craft a haunting, complex look at a life gone wrong. Monday, July 30, 6:45pm (Q&A with Joan Churchill)

Ashley Connor Sneak Preview! The Miseducation of Cameron Post Desiree Akhavan, USA, 2018, 90m Based on the celebrated novel by Emily M. Danforth, Desiree Akhavan’s second feature follows the titular character (Chloë Grace Moretz) in 1993 as she is sent to a gay conversion therapy center after getting caught with another girl on prom night. In the face of intolerance and denial, Cameron meets a group of fellow sinners, including amputee stoner Jane (Sasha Lane) and her friend Adam (Forrest Goodluck), a Lakota Two-Spirit. Together, this group forms an unlikely family with a will to fight. Akhavan and DP Ashley Connor evoke the emotional layers of Danforth’s novel with an effortless yet considered attention to the spirit of the ’90s and the audacious, moving performances of the ensemble cast. A FilmRise release. Sunday, July 29, 6:00pm (Q&A with Ashley Connor)

Josée Deshaies House of Tolerance / L’Apollonide: Souvenirs de la maison close Bertrand Bonello, France, 2011, 35mm, 122m French with English subtitles “I could sleep for a thousand years,” drawls a 19th-century prostitute—paraphrasing Lou Reed—at the start of Bonello’s hushed, opium-soaked fever dream of life in a Parisian brothel at the turn of the century. House of Tolerance is, among other things, Bonello’s most gorgeous and complete application of musical techniques to film grammar, his most rigorous attempt to sculpt cinematic space, his most probing reflection on the origins of capitalist society, and his most sophisticated study of the movement of bodies under immense constraint. A shocking mutilation, a funeral staged to The Moody Blues’ “Nights in White Satin,” a progression of ritualized, drugged assignations and encounters: Bonello and frequent collaborator Josée Deshaies capture it all with a mixture of casual detachment and needlepoint precision. Wednesday, August 1, 2:00pm Sunday, August 5, 4:30pm

Crystel Fournier Tomboy Céline Sciamma, France, 2011, 35mm, 82m French with English subtitles A sensitive, heartrending portrait of what it feels like to grow up different, Céline Sciamma’s beautifully observed coming-of-age tale aches tenderly with the tangled confusion of childhood. When ten-year-old Laure’s family moves to a new neighborhood during the summer, the gender-nonconforming preteen (played by the impressively naturalistic Zoé Héran) takes the opportunity to present as Mickäel to the neighborhood kids—testing the waters of a new identity that neither friends nor family quite understand. Sciamma’s warmly empathetic tone is perfectly complemented by the soft-lit impressionism of Crystel Fournier’s glowing cinematography. Print courtesy of the Institut Français. Monday, August 6, 2:15pm Thursday, August 9, 9:15pm

Agnès Godard Beau Travail Claire Denis, France, 1999, 35mm, 92m French, Italian, and Russian with English subtitles Denis’s loose retelling of Billy Budd, set among a troop of Foreign Legionnaires stationed in the Gulf of Djibouti, is one of her finest films, an elemental story of misplaced longing and frustrated desire. Beneath a scorching sun, shirtless young men exercise to the strains of Benjamin Britten, under the watchful eye of Denis Lavant’s stone-faced officer Galoup, their obsessively ritualized movements simmering with barely suppressed violence. When a handsome recruit wins the favor of the regiment’s commander, cracks start to appear in Galoup’s fragile composure. In the tense, tightly disciplined atmosphere of military life, Denis found an ideal outlet for two career-long concerns: the quiet agony of repressing one’s emotions and the terror of finally letting loose. An NYFF37 selection. Print courtesy of the Institut Français. Thursday, July 26, 7:00pm (Q&A with Agnès Godard)

35 Shots of Rum / 35 rhums Claire Denis, France/Germany, 2008, 35mm, 100m French and German with English subtitles When is a rice cooker more than just a rice cooker? When it’s in the masterful hands of Claire Denis, who somehow transforms it into a moving metaphor for the evolving relationship between a Parisian train conductor (Alex Descas) and his devoted twenty-something daughter (Mati Diop) as he gently nudges her out of the nest and each tests the waters of new relationships. Warmed by the ember-glow of Agnès Godard’s beautifully burnished cinematography, Denis’s delicately bittersweet take on the Ozu-style family drama conveys worlds of meaning and emotion—attraction, heartache, loss, hope—in a mere glance, a gesture, and, yes, a kitchen appliance. Thursday, July 26, 9:30pm (Introduction by Agnès Godard) Tuesday, July 31, 1:00pm

The Intruder / L'intrus Claire Denis, France, 2005, 35mm, 130m French, English, Korean, Russian, and Polynesian with English subtitles Rich, strange, and tantalizingly enigmatic, Denis’s crypto-odyssey is a mesmeric sensory experience that haunts like a half-remembered dream. Inspired by a book by philosopher Jean-Luc Nancy, The Intruder skips across time and continents—from the Alpine wilds to a neon-lit Korea to a tropical Tahiti suffused with languorous melancholy—as it traces the journey of an inscrutable, ailing loner (Michel Subor) seeking a black market heart transplant and his long-lost son. An impressionist wash of hallucinations, memories, and dreams are borne along on the lush textures of Agnès Godard’s shimmering cinematography. Print courtesy of the Institut Français. Saturday, July 28, 3:00pm (Q&A with Agnès Godard) Thursday, August 9, 4:15pm

Kristen Johnson Cameraperson Kirsten Johnson, USA, 2016, 102m How much of one’s self can be captured in the images shot of and for others? Kirsten Johnson’s work as a director of photography and camera operator has helped earn her documentary collaborators (Laura Poitras, Michael Moore, Kirby Dick, Barbara Kopple) nearly every accolade and award possible. Recontextualizing the stunning images inside, around, and beyond the works she has shot, Johnson constructs a visceral and vibrant self-portrait of an artist who has traveled the globe, venturing into landscapes and lives that bear the scars of trauma both active and historic. Rigorous yet nimble in its ability to move from heartache to humor, Cameraperson provides an essential lens on the things that make us human. A 2016 New Directors/New Films selection. Friday, July 27, 6:30pm Thursday, August 2, 4:15pm

Derrida Kirby Dick & Amy Ziering, USA, 2002, 35mm, 84m Postmodern intellectual rockstar Jacques Derrida receives an appropriately self-reflexive portrait in this playful, probing documentary. Framed by the French philosopher’s statements about the inherent unreliability of biography, it finds co-director Amy Ziering attempting to tease out the links between Derrida’s radically influential thinking (he expounds on everything from forgiveness to Seinfeld) and his own life. Even as the alternately witty and reflective Derrida remains cagey about personal matters, Kirsten Johnson’s attentive camera captures revealing flashes of the man behind the ideas. What emerges is a fascinating interrogation of filmic truth: a documentary that relentlessly deconstructs itself. Friday, July 27, 8:45pm

Ellen Kuras Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind Michel Gondry, USA, 2004, 35mm, 108m The feverish imaginations of DIY surrealist Michel Gondry and screenwriter Charlie Kaufman kick into overdrive for the great gonzo sci-fi romance of the early 2000s. When nice guy dweeb Joel (Jim Carrey) encounters blue-haired spitfire Clementine (Kate Winslet) on the LIRR, there’s a spark of attraction, but also something familiar—almost as if they’ve met before… Cue a ping-ponging, time- and space-collapsing journey through memory and a star-crossed love gone sour. The high-contrast handheld camerawork of Ellen Kuras enhances the whiplash sense of disorientation in what is, ultimately, a heart-wounding parable about the ways in which we inevitably hurt those we love most. Wednesday, August 1, 4:30pm Saturday, August 4, 9:30pm

Swoon Tom Kalin, USA, 1992, 35mm, 93m One of the most daring works to emerge from the New Queer Cinema movement of the early 1990s, Swoon offers a radical, revisionist perspective on the infamous Leopold and Loeb murder case. Channeling the spirits of Dreyer, Bresson, and Jean Genet, director Tom Kalin challenges viewers to identify with two of the most notorious killers of the 20th century, their crime—the Nietzsche-influenced thrill killing of a schoolboy in 1920s Chicago—and punishment recounted in ghostly black and white by Ellen Kuras. Throughout, Kalin cannily deconstructs the ways in which Leopold and Loeb’s homosexuality has been historically sensationalized and demonized—a provocative analogy for queer persecution in the AIDS era. Monday, July 30, 2:00pm Monday, August 6, 8:30pm

Sabine Lancelin La captive Chantal Akerman, France/Belgium, 2000, 35mm, 118m French with English subtitles Chantal Akerman’s hypnotic exploration of erotic obsession plays like Vertigo filtered through the director’s visionary feminist formalism. Loosely inspired by the fifth volume of Proust’s In Search of Lost Time, it circles around the very-strange-indeed relationship between the seemingly pliant Ariane (Sylvie Testud) and the disturbingly jealous Simon (Stanislas Merhar), whose need to possess her completely in turn renders him hostage to his own destructive desires. The coolly contemplative camera style of Sabine Lancelin imparts an unbroken, trance-like tension, which finds release only in the thunderous roil of the operatic score. Print courtesy of Cinémathèque Royale de Belgique. Sunday, July 29, 1:00pm

The Strange Case of Angelica / O Estranho Caso de Angélica Manoel de Oliveira, Portugal, 2010, 35mm, 97m Manoel de Oliveira’s sly, metaphysical romance—made when the famously resilient director was a mere 102 years old—is a mesmerizing, beyond-the-grave rumination on love, mortality, and the power of images. On a rain-slicked night, village photographer Isaac (Ricardo Trêpa) is summoned by a wealthy family to take a picture of their beautiful, recently deceased daughter Angelica (Pilar López de Ayala). What ensues is a ghostly tale of romantic obsession as Isaac finds his dreams—and his photographs—haunted by the spirit of the bewitching young woman. The crisp chiaroscuro compositions of cinematographer Sabine Lancelin enhance the film’s otherworldly, unstuck-in-time aura. An NYFF48 selection. Friday, July 27, 1:00pm Wednesday, August 1, 9:00pm

Jeanne Lapoirie Eastern Boys Robin Campillo, France, 2013, 128m French with English subtitles Jeanne Lapoirie’s surveillance-style camera, looking from above, masterfully follows the men who loiter around the Gare du Nord train station in Paris as they scrape by however they can, forming gangs for support and protection, ever fearful of being caught by the police and deported. When the middle-aged, bourgeois Daniel (Olivier Rabourdin) approaches a boyishly handsome Ukrainian who calls himself Marek for a date, he learns the young man is willing to do anything for some cash. What Daniel intends only as sex-for-hire begets a home invasion and then an unexpectedly profound relationship. The drastically different circumstances of the two men’s lives reveal hidden facets of the city they share. Presented in four parts, this absorbing, continually surprising film by Robin Campillo (BPM: Beats Per Minute) is centered around relationships that defy easy categorization, in which motivations and desires are poorly understood even by those to whom they belong. Monday, July 30, 4:00pm Saturday, August 4, 4:45pm

Rain Li Paranoid Park Gus Van Sant, USA, 2007, 35mm, 85m At once a dreamlike portrait of teen alienation and a boldly experimental work of film narrative, Paranoid Park finds Gus Van Sant at the height of his powers. A withdrawn high-school skateboarder (Gabe Nevins) struggles to make sense of his involvement in an accidental death. He recalls past events across tides of memory, and expresses his feelings in a diary—which is, in effect, the movie we are watching. The extraordinary skating scenes, filmed by cinematographers Rain Li and Christopher Doyle in a lyrical mixture of Super 8 and 35mm, depict their subjects soaring in space, momentarily free of the earthly troubles of adolescence. An NYFF45 selection. Tuesday, August 7, 9:15pm

Hélène Louvart Beach Rats Eliza Hittman, USA, 2017, 95m Hittman follows up her acclaimed debut, It Felt Like Love, with this sensitive chronicle of sexual becoming. Frankie (a breakout Harris Dickinson), a bored teenager living in South Brooklyn, regularly haunts the Coney Island boardwalk with his boys—trying to score weed, flirting with girls, killing time. But he spends his late nights dipping his toes into the world of online cruising, connecting with older men and exploring the desires he harbors but doesn’t yet fully understand. Sensuously lensed on 16mm by cinematographer Hélène Louvart, Beach Rats presents a colorful and textured world roiling with secret appetites and youthful self-discovery. A 2017 New Directors/New Films selection. A Neon release. Thursday, August 2, 9:00pm

Pina [in 3D] Wim Wenders, Germany/France, 2011, 106m German, English, and French with English subtitles Wim Wenders began planning this project with legendary choreographer Pina Bausch in the months before her untimely death, selecting the pieces to be filmed and discussing the filmmaking strategy. Impressed by recent innovations in 3D, Wenders decided to experiment with the format for this tribute to Bausch and her Tanztheater Wuppertal; the result sets the standard against which all future uses of 3D to record performance will be measured. Not only are the beauty and sheer exhilaration of the dance s and dancers powerfully rendered by Hélène Louvart and Jörg Widmer’s lensing, but the film also captures the sense of the world that Bausch so brilliantly expressed in all her pieces. Longtime members of the Tanztheater recreate many of their original roles in such seminal works as “Café Müller,” “Le Sacre du Printemps,” and “Kontakthof.” An NYFF49 selection. Sunday, August 5, 2:00pm Tuesday, August 7, 2:00pm

The Wonders Alice Rohrwacher, Italy/Switzerland/Germany, 2014, 110m French with English subtitles Winner of the Grand Prix at the Cannes Film Festival, Alice Rohrwacher’s vivid story of teenage yearning and confusion revolves around a beekeeping family in rural central Italy: German-speaking father, Italian mother, four girls. Two unexpected arrivals prove disruptive, especially for the pensive oldest daughter, Gelsomina. The father takes in a troubled teenage boy as part of a welfare program, and a television crew shows up to enlist local farmers in a kitschy celebration of Etruscan culinary traditions (a slyly self-mocking Monica Bellucci plays the bewigged host). Hélène Louvart’s lensing combines a documentary attention to daily ritual with an evocative atmosphere of mystery to conjure a richly concrete world that is subject to the magical thinking of adolescence. An NYFF52 selection. Friday, August 3, 9:15pm Wednesday, August 8, 3:45pm

Irina Lubtchansky Around a Small Mountain / 36 vues du Pic Saint Loup Jacques Rivette, France/Italy, 2009, 35mm, 84m French with English subtitles The final film from arch gamesman Jacques Rivette is a captivating variation on one of the themes that most obsessed him: the ineffable interplay between life and performance. Luminously photographed by Irina Lubtchansky in the open-air splendor of the south of France, it revolves around an Italian flaneur (Sergio Castellitto) who finds himself drawn into the world of a humble traveling circus led by the elusive Kate (Jane Birkin), whose enigmatic past becomes a tantalizing mystery he is determined to solve. In a career studded with sprawling shaggy dog epics, Rivette’s swan song is a deceptively slight grace note that contains multitudes. An NYFF47 selection.

Preceded by: Sarah Winchester, Ghost Opera / Sarah Winchester, Opera Fantôme Bertrand Bonello, France, 2016, 24m North American Premiere A film to stand in for an opera unmade: Bonello’s moody, baroque meditation on the heiress to the Winchester rifle fortune plays like a ballet-cum-horror film, an ornate tapestry of enigmatic images, chilling synths, and traces of a tragic and eccentric life. An NYFF54 selection. A Grasshopper Film release. Friday, August 3, 4:15pm Wednesday, August 8, 9:15pm

Babette Mangolte The Camera: Je or La Camera: I Babette Mangolte, USA, 1977, 88m Though perhaps best known as the cinematographer for Chantal Akerman’s groundbreaking 1970s work—as well as for her collaborations with avant-garde icons like Yvonne Rainer, Trisha Brown, and Marina Abramović—Babette Mangolte is a singular cinematic visionary in her own right. In this structuralist auto-portrait, Mangolte allows viewers to peer through the lens of her camera as she produces a series of still photographs, first of models, then of the streetscapes of downtown Manhattan. As we experience the act of image-making through her eyes, what emerges is a heady consideration of the art and act of seeing and of the complex relationship between photographer, subject, and viewer. Monday, August 6, 6:30pm

Jeanne Dielman, 23, quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles Chantal Akerman, Belgium/France, 1976, 35mm, 201m French with English subtitles A landmark of feminist art, Chantal Akerman’s minimalist masterpiece is both a monumental and microscopic view of three days in the life of a fastidious Belgian single mother (a sphinx-like Delphine Seyrig) as she goes about her housework, peeling potatoes and washing dishes with the same clinical detachment with which she makes love to the occasional john. And then slowly, almost imperceptibly, things begin to go awry… The rigorous, relentlessly impassive gaze of Babette Mangolte’s camera is transfixing but, in the words of the director, “never voyeuristic”; it’s a uniquely feminine way of seeing made manifest by one of the most sui generis filmmaker-cinematographer partnerships in history. Tuesday, July 31, 3:15pm Saturday, August 4, 1:00pm

Claire Mathon Stranger by the Lake / L’inconnu du lac Alain Guiraudie, France, 2013, 97m French with English subtitles Alain Guiraudie’s Cannes-awarded exploration of death and desire unfolds entirely in the vicinity of a gay cruising ground that becomes a crime scene. Franck (Pierre Deladonchamps) is a regular at a lakeside pickup spot, where he finds companionship both platonic and carnal. But his new paramour Michel (Christophe Paou) turns out to be a love-’em-and-leave-’em type, in the deadliest sense… Guiraudie has long been a singular voice in French cinema: anti-bourgeois, at ease in nature, a true regionalist and outsider. Here he and DP Claire Mathon capture naked bodies and hardcore sex with the same matter-of-fact sensuousness they bring to ripples on the water and the fading light of dusk. An NYFF51 selection. Monday, July 30, 9:15pm Thursday, August 9, 2:00pm

Reed Morano Sneak Preview! I Think We’re Alone Now Reed Morano, USA, 2018, 93m Pulling double duty as director and cinematographer, Reed Morano finds the melancholic beauty in the end of the world with this gorgeous and strange drama starring Peter Dinklage and Elle Fanning as the last people on Earth. When the film opens in a desolate upstate New York, the misanthropic Del (Dinklage) is performing rote, custodial tasks to clean up the chaos left around his hometown—and relishing his newfound solitude—until another, sprightly survivor (Fanning) arrives. Winner of the Special Jury Prize for Excellence in Filmmaking at the 2018 Sundance Film Festival, I Think We’re Alone Now is a visually audacious entry in the postapocalyptic genre and an idiosyncratic take on loneliness and grief. Thursday, August 2, 6:30pm

Rachel Morrison Fruitvale Station Ryan Coogler, USA, 2013, 85m Coogler’s remarkable debut feature explores the life and harrowing death of Oscar Grant (played by Michael B. Jordan), a 22-year-old African-American man killed by police in the early hours of January 1, 2009. Six months after sweeping both the Grand Jury Prize and the Audience Award at the Sundance Film Festival, Fruitvale Station opened on the same weekend that jurors in Florida acquitted George Zimmerman in the death of Trayvon Martin. Rachel Morrison’s gripping, exploratory Super 16 on-location camerawork dramatizes the unseen complexities and personal relationships of Grant’s inner circle with a startling sense of urgency, emotion, and the unflagging awareness of a preventable tragedy too often seen in the news cycle. Sunday, August 5, 7:00pm

Free Talk: The Female Gaze Join us for an hour-long conversation with cinematographers Natasha Braier, Ashley Connor, Agnès Godard, and Joan Churchill as they discuss the series and reflect on their careers and influences, and how they approach their craft. Sponsored by HBO®. Saturday, July 28, 6:30pm* Elinor Bunin Munroe Film Center, Amphitheater, 144 W 65th Street

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

La Nouvelle Vague: Rebels with a Cause

Over the course of its lifetime, cinema has undergone various degrees of evolution in technique, style and theory. From its starting years as a silent, black-and-white medium of spectacle to becoming a vehicle of social commentary, different eras populate the history of the art form— one of which is La Nouvelle Vague or the French New Wave, an art movement widely known for its stylistic experimentation and upending of conventional ideals. But to further understand why and how French New Wave came to be would require examining the previous generation of films and cultural subtexts, tracing its origins and development through the years, identifying essential intentions and theories borne out of its inception, and assessing its legacy since its passing.

Given that French New Wave’s creation was necessitated mainly as a response to the prevailing trends of the previous era, it is important to investigate the overall landscape before its arrival. Prior to French New Wave, mainstream films were heavily tied to the studio system restricting filmmaking within the walls of production houses. Not only in space, it limited films in terms of overall aesthetic— actions remained in stationary shots, artificial set designs mimicked the environment of theatre productions, plots had to be revisited to accommodate the rigid structures. Dominance of big studios also provided a challenge for aspiring directors during the period in the form of preference towards established filmmakers and their mastered craft (Grant, 2007). With such restrictions, a choice between technique and experimentation became a recurring dilemma and more often than not, prevailing trends pointed to the former.

Even a bigger motivator for the movement was the cultural climate of its belonged era. The question on whether Germany’s occupation of France could have been mitigated if not avoided lingered over the heads of the elite. Such proximity to the war and failure in avoiding its arrival brought upon the whole of French society an air of simmering political unrest continuously stifled by the public’s eagerness to regain normalcy. Fortunately, it wasn’t long before France started to incur financial recovery. Unfortunately, the rush towards economic stability meant a surge in capitalistic tendencies. Thus, consumerism made its expected return with little to no restraint forcing mainstream cinema to cater to the sensibilities of the bourgeoisie and their demands for movies steeped in romanticism and comedy. Coupled with growing materialistic attitude, television’s entry into the picture presented a shift on media consumption wherein it was no longer expected of the public to go out in search of entertainment, instead entertainment was supposed to find them (Crisp, 1993). With this, French cinema underwent a deep reevaluation regarding its place in France’s postwar cultural scene specifically whether it belonged in the upper echelons of “highbrow art” or was better off in the business of the bourgeoisie.

Integral to the establishment of the movement were the precursory dialogues among intellectuals and cinephiles about the state French cinema, most of which centered on the impact of external forces enumerated above. Cahiers du Cinema, a monthly French publication focusing on film criticism and theory, became the place of assembly to most of the leading voices of French New Wave which included the likes of Claude Chabrol, Eric Rohmer and Jacques Rivette and through their writings, established core intentions carried by the movement. Francois Godard, a notable writer for the magazine, embodied much of what the movement essentially stands for— that, in spite of the iconoclastic reputation that has come to be associated with it, so much about French New Wave is rooted in the belief of preserving cinema’s artistic value. Throughout his career as a filmmaker, Godard translated his love of moviemaking through frequent acts of homage— he made in-film references to other works he held in reverence, borrowed trademarks from respected filmmakers, centered character-driven conversations on cinema and at one point, even gave Jean Pierre-Melville a cameo role (Wiegand, 2012). What these constant meta-discussions regarding cinema revealed was not an effort to destroy its very language but rather an intention to interrogate its grammar and meaning towards a more democratic expression. Such belief in freeing films and their methods of creation from constraints brought by big studio houses and the rule of market became the driving force which helped spur French New Wave into action.

Although Cahiers and its critics managed to develop a strong presence among film enthusiasts who echoed the same concern of liberating cinema, it was only after the publication of A Certain Tendency of French Cinema when French New Wave was propelled into the nation’s consciousness. The essay which voiced out grievances against popular cinema in uber-polemic writing became the unofficial manifesto of the movement. Francois Truffaut, the author of the essay, lambasted the prevalence of what he called “Tradition of Quality”, a tendency of French studio system to favor “…literary adaptation, which caused French films to become increasingly verbal and theatrical.” (Cook, 2016, p. 343). Moreover, he scorned the glorification of screenwriters over directors which he argued imposed rigid rules on filmmaking thereby diminishing the director’s vision for the film.

Out of the essay’s publication, politiques des auteurs or auteur theory was highlighted as a central argument in the push toward greater authority of directors over film productions. At its core, auteur theory championed the director as the principal creator of a film, above screenwriters and film producers, comparable to authors having full creative control of their literary works. Although not a new concept at the time, Truffaut’s use of auteur theory in the essay accompanied by his stark denunciation of the studio system facilitated auteurism’s transition from a mere form of critical theory to a practicable filmmaking approach. The effect of French New Wave and its promotion of auteur theory on contemporary French cinema was seen in the surge of films that employed location shooting and practical effects such as natural lighting and live sound— aspects of filmmaking directors were now able to dictate without third-party interference (Neupert, 2007). Such filmic language which puts emphasis on low-budget production and documentary style filmmaking afforded directors leeway in experimentation and would later dominate the film industry displacing studio houses from its norm status somewhere in the 60s (Crisp, 1993).

Further impact of the French New Wave was observed in the successes of its directors not only in the box office but also in film festival circuits. Such was the case of Truffaut’s directorial debut, The 400 Blows, in 1959 where he was awarded Best Director in Cannes Film Festival in spite of being banned as a critic from the same festival the year before. In years to come, French New Wave directors would go on to achieve varying degrees of recognition but more astounding about these achievements was the fact that most of these critics-turned-filmmakers were under the age of 30. In effect, the rise to prominence of these young directors lead to increased numbers of new talents being hired in the industry and more importantly, “…granted the young filmmakers an unconditional command over every facet of the creative process.” (Fournier-Lanzoni, 2002, p. 212).

Even worth investigating are the ramifications of French New Wave around its neighboring countries and across the Atlantic which began to adopt principles tied to it. For instance, familiar imprints can be recognized in successive New Waves and film movements most notably in American New Wave taking great inspiration from auteur theory and Dogme 95 whose strict obedience to bare-bones style of cinema invoked the realism of French New Wave. Arguably, a more long-lasting legacy left can be attributed to its use of radical filmmaking techniques. The utilization of jump cuts in many films from the era, particularly in Godard’s revolutionary Breathless, demonstrated innovative and playful approaches to continuity editing and storytelling (Sterritt, 2007). While deemed controversial at the time, jump cuts and long takes became staple trademarks in French New Wave films and would later flourish into a dignified form of creative expression employed in future works outside of the movement .

Perhaps the most apparent evidence of the movement’s influence is found in the longevity of careers of its pioneers post-French New Wave. Well into the 21st century, Cahiers directors sustained a prolific presence in the industry with Chabrol and Rohmer continuing to release films as late as 2007 before their retirement and subsequent passing. Godard, the last surviving member of the group, maintains an active career having recently released a film essay, The Image Book, in 2018 which competed and won a special prize in that year’s Cannes Film Festival. Future generations of filmmakers also remain indebted to French New Wave for paving the way to an environment more welcoming of young talent and more respectful of their creative vision. Directors being able to attach their names to their creations owe much of that privilege to the movement’s campaign for authorial role of filmmakers. Just by the mention of “Tarantino film” or “Fincher film”, one could expect a certain aesthetic or style unique only to those names— a custom made possible by auteur theory. In summary, the impact of French New Wave not only to filmmaking but also to the very industry it belongs to cements its place as a formative era in film history and while it had passed its peak many decades ago, the spirit of rebellion that energized lovers of movies into taking arms in defense of the art form continue to ripple in the whole of cinema.

Bibliography:

Cook, D. (2016). A history of narrative film (5th edition). New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

Crisp, C. (1993). The classic French cinema. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Fournier-Lanzoni, R. (2002). French cinema: From its beginnings to the present. New York: Continuum.

Glenn, C. (2014). Jean-Luc Godard and Francois Truffaut: the influence of Hollywood, modernization and radical politics on their films and friendship. (Master’s thesis).Clemson University, Clemson, South Carolina.

Grant, B. K. (2007). Schirmer encyclopedia of film (Vol. 2). Detroit: Schirmer Reference.

Grosoli, M. (2014). The politics and aesthetics of the "politique des auteurs". Film criticism, 39(1), 33-50. Retrieved August 7, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/24777962

Hillier, J. (1986). Cahiers du Cinéma: the 1950s: neo-realism, Hollywood, new wave. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

Neupert, R. (2007). A history of the French new wave cinema. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

Sterritt, D. (1999). The films of Jean-Luc Godard: Seeing the invisible. Cambridge, U.K: Cambridge University Press.

Thompson, K. & Bordwell, D. (2003). Film history: an introduction. (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Truffaut, F. (1976). A Certain Tendency of the French Cinema. In B. Nichols (Ed.). Movies and methods: an anthology (Vol. 1, pp. 224-236). Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. (Original work published in Cahiers du cinema 31, 1954).

Wiegand, C. (2012). French new wave. Harpenden, Herts: Pocket Essentials. (Original work published 2005)

0 notes

Text

Pacôme Thiellement ou la transcendance des obsessions

Comment est-ce que je me suis retrouvée à lire un bouquin sur Jésus ? Durant les premières pages de "La victoire des Sans Roi. Révolution gnostique", qui passent en revue différentes appropriations par les apôtres de la pensée de Jésus, j'ai eu le temps de me poser la question. Je n'ai pas le moindre rapport avec la religion et un intérêt en dessous de zéro pour le christianisme. Mais il a fallu deux phrases, en fin de chapitre, pour que craque l'allumette de la curiosité et que je me souvienne ce que j'étais venue faire là.

"Dieu est le pire ennemi de Jésus et Jésus est le pire ennemi de Dieu. Et c'est là que les problèmes commencent."

Si je viens de finir un bouquin sur les Gnostiques, les premiers adversaires du christianisme, fidèles de Jésus mais dissidents de l'Eglise chrétienne, c'est de la faute de Pacôme Thiellement.

J'ai rencontré ses écrits autour de 2012-2013. Je lisais à l'époque avidement le site qui a le plus bâti ma conscience politique, Les Mots Sont Importants, créé par Sylvie Tissot et Pierre Tevanian. Les articles de Pacôme Thiellement portaient sur "Céline et Julie vont en bateau", le film de Jacques Rivette. Je me souviens, je n'y comprenais rien. C'étaient parmi les textes les plus ésotériques, confus et colorés que j'avais pu lire. Mais il élaborait une analyse qui avait créé en moi une petite déflagration. Sa proposition consistait à dire que les films dans lesquels les femmes sont amies, collaborent entre elles et ne sont pas punies pour ça, sont rarissimes. "Céline et Julie" en est le parangon. Le film, que j'ai fini par découvrir lors d'un mini ciné-club féministe, compte depuis parmi ce que j'ai vu de plus ésotérique, confus et coloré. Et les bouquins de Pacôme Thiellement me happent peu importe le sujet.

Il parvient à écrire avec suspense des essais qui articulent une mosaïque d'objets culturels populaires et des enseignements théoriques et spirituels qui, on l'aura compris, peuvent remonter à perpète. Il a l'art de semer des graines qui font lever un sourcil, tendre l'oreille, et qu'on ne comprendra pourtant que deux ouvrages plus loin. Il parle de gens, de lieux, en énonçant des noms qui ne sont pas toujours explicités. Sans nécessairement de contexte ni de pédagogie, le lecteur doit accepter de ne pas savoir où il va, où il est. Pour la blague, j'ai lu tout "Tu m'as donné de la crasse et j'en ai fait de l'or" et un bon tiers de "La victoire des Sans Roi" en pensant que le lieu de la découverte des textes des Gnostiques en 1945, la bibliothèque de Nag Hammadi, appartenait à quelqu'un. Je pensais que Nag Hammadi était une personne. (C'est une ville égyptienne proche de Louxor). Mais quand bien même on est souvent paumé, quand bien même la langue, les correspondances et les symboles sont parfois obscurs, je n'ai jamais été passionnée par des essais de cette façon. A part chez Mona Chollet, ce n'est jamais un type de littérature que je n'arrive pas à lâcher. Pourquoi est-ce que j'aime autant les livres de Pacôme Thiellement ?

Je partage peu de ses obsessions culturelles. Il y a bien Lynch, Philip K. Dick, The OA... Mais je ne suis ni proche de Franck Zappa, ni des Beatles, ni de Beaudelaire, ni de Blake, ni de Shakespeare. Je n'ai fini ni Lost, ni Buffy, ni The Leftovers. Mais ce n'est pas un problème. J'ai mes propres obsessions et je sais ce que ça peut faire à l'âme. De ça découle ma fascination pour le travail d'alchimiste qu'il opère, connectant des séries TV à des préceptes datant du début de la chrétienté, reliant au divin des récits de science-fiction et tirant de pop songs des enseignements existentiels. Il me semble être l'un de ceux qui parviennent le mieux à penser avec ses obsessions culturelles. Et il fournit généreusement la possibilité de penser avec lui. Son appropriation des œuvres, l'exégèse qu'il en fait, consiste à en retirer ce qui peut s'appliquer à l'existence. Ce qui peut résonner dans des petits bouts d'histoires personnelles, pour les connecter, les réconcilier ou en adoucir les contours. Il réussit à aller très haut dans l'abstraction, à nous égarer dans des circonvolutions vaporeuses, pour ensuite revenir tout en bas, l'appliquer au plus concret. Pacôme Thiellement nous dit littéralement comment l'art aide à vire.

Je suis parfois déstabilisée par sa façon de connecter des choses qui semblent n'avoir rien à voir. Chez Thiellement, si deux choses renvoient le même éclat, c'est qu'elles ont une essence en commun. Il a une façon de planter des connexions entre les idées avec un aplomb qui leur donnerait presque de l'objectivité. Avec une habileté d'illusionniste, Il fait apparaitre un pont entre deux rives avant de vous regarder droit dans les yeux : "Evidemment qu'il a toujours été là, ce pont. Vous ne l'aviez jamais remarqué ?". La pratique n'est pas pour autant sans rigueur. Il y a bien des références aux Sans Roi dans les discours de John Lennon, quand bien même la lecture des paroles d'une chanson ne nous semble pas immédiatement probante. Mais si la pratique trouble, c'est que le fait de plaquer ses propres conceptions sur un contexte différent, de tisser une narration entre des évènements indépendants, est considéré dans des domaines comme les sciences humaines comme un écueil. Mais là, il le peut. Il y a dans la pensée critique sur l'art une liberté d'un autre ordre. Ce qu'il y a de chouette, quand on parle de forces supérieures, de pop culture et de prescriptions spirituelles (avec le même sérieux) c'est qu'on peut se permettre de bâtir des ponts qui finissent par ressembler à des tourbillons arachnéens. La sensibilité n'obéit à aucune autre loi que la subjectivité.

Même si on n'a pas les mêmes codes ou les mêmes interprétations de l'univers, on peut se retrouver dans ce que Pacôme Thiellement garde du monde pour en faire une planche de salut : "l'art, l'amour et la politique".

youtube

0 notes

Video

youtube

From the Maguelone Festival 2012 Jordi Savall and Hespèrion XXI - Lachrimae Caravaggio - Musical Europe in the Time of Caravaggio. Check the time codes below. Subscribe to Total Baroque: https://goo.gl/ZWoSxm Jordi Savall - viola da gamba Ferran Savall - voice Philippe Pierlot - viola da gamba Sergi Casademunt - viola da gamba Lorenz Dufschmidt - viola da gamba Xavier Puertas - violone Xavier Diaz-Latorre - lute, theorbo & guitar Perdo Estevan - percussions 2:03 Anonymous - Pavana del re 3:56 Anonymous - Galliarda la traditora 5:37 Jordi Savall - Saltarello 7:22 Giovanni M.Trabaci - Durezze E Ligature 13:15 John Dowland - Lachrimae Pavan 17:06 Orlando Gibbons - In Nomine a 4 19:16 William Brade - Ein Schottisch Tanz 22:15 Jordi Savall - Passacaglia Libertas 25:00 Jordi Savall - Deploratio II 27:43 Luys del Milà - Pavana and Gallarda 30:47 Joan Cabanilles - Corrente Italiana 34:17 Jordi Savall & Dominique Fernandez - Concentus Aria 35:36 Jordi Savall & Dominique Fernandez - Concentus Recitativo 37:52 Jordi Savall - Folias 41:51 Anonymous - Pavane de la Petite Guerre 44:06 Anonymous - Bourrée d'avignonez 46:27 Consonanze Stravaganti (d'après trabaci) 47:57 Jordi Savall - Deploratio III 51:14 Samuel Scheidt - Paduan & Courant dolorosa 57:56 Jordi Savall - Spiritus Morientis 1:00:53 Jordi Savall - Deploratio IV 1:05:29 Luigi Rossi - Fantasie "Les Pieurs d`Orphée" 1:08:40 Anonymous - Sarabande Italienne 1:10:16 Cantus Caravaggio III "In Memoriam" A co-production of Calicot - Mezzo - TV Sud - Maguelone Festival Video director: Olivier Simonnet

LACHRIMAE CARAVAGGIO

Review by: John Greene

Artistic Quality: 8 Sound Quality: 10

Since 1991 when Jordi Savall contributed to the soundtrack of Alain Corneau’s acclaimed film Tous les Matins du Monde (type Q4828 in Search Reviews), he’s occasionally supplemented other mostly French and Spanish soundtracks with similar improvised music in keeping with the film’s period and theme. The movie featuring most of Savall’s music to date has been Jacques Rivette’s 1994 epic Jeanne La Pucelle, where he is credited for more than half of the movie’s score. This new Alia Vox offering titled Lachrimae Caravaggio (Caravaggio’s Tears) is Savall’s first non-soundtrack programmatic effort as well as the first recording devoted exclusively to his music.

The program is divided into seven “Statios” (stanzas) of four to five movements, each representing Savall’s take on seven works by the Renaissance Italian painter Michelangelo Caravaggio. Sharing equal billing with Savall in the project is the French novelist Dominique Fernandez, who provides seven brief complimentary essays about each of the selected paintings in the accompanying booklet.

This is one of the quietest, most meditative ensemble recordings Savall has ever made. The vast majority of the program is devoted to inordinately pensive string improvisations performed by Savall, violinists Riccardo Minasi and Xavier Puertas, and harpist Andrew Lawrence-King (Note: Savall’s son Ferran also is listed as one of the five “improvisators”, though his contribution is limited to light flamenco-like moaning in the four wisely dispersed “Deploratio” movements accompanied only by his dad).

Savall’s Sinfonia di Guerra (fashioned after the opening Sinfonia of Monteverdi’s seminal masterpiece Combattimento di Tancredi e Clorinda–a work Savall often performs live though has yet to record), the (eventually) spirited Passacaglia Libertas, and the at times stunningly dissonant Spiritum Morientis count among the program’s very few, memorably upbeat moments. Andrew Lawrence-King’s solo improvisations in the Passicaglia Umbrae and very brief Transitio that opens the fifth “Statio” couldn’t be lovelier.

Alia Vox’s SACD sound is absolutely gorgeous; rich, well-balanced, and sumptuously detailed. The handsome spare-no-expense digipac presentation and 168-page booklet (translated in six languages) also is typical of the care Alia Vox continues to take in every one of its projects. Given the title of the program and the often dark, mournful nature of Caravaggio’s subject matter, it’s certainly understandable why Savall chose to keep the proceedings here so consistently low key. However, this 77-minute ride often gets a little tedious because of it. Recommended only to Savall’s most devout fans.

https://www.classicstoday.com/review/review-14376/

0 notes

Text

Jonathan Rosenbaum on His New Book Collection, Cinematic Encounters

In the summer of 1972, Jonathan Rosenbaum was a writer and film critic living in Paris who had begun researching an article on Orson Welles’s original Hollywood project, an adaptation of Joseph Conrad’s novella, Heart of Darkness.