#its still in early stages but ill publish someday

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Oh, I've thought about it

okay think about it -- newsies punk rock band au. THINK ABOUT ITTT

#so basically#it's your classic high school rivalry au#with secret dating sprace#and elmer is Spot's brother#elmer is also graves in Brooklyn#jack katherine race albert and crutchie are in a band called Santa Fe Strikes Again#(i looked up a random band name generator when i started writing and it seemed too good to pass up)#jack is lead guitar/vocals katherine is vocals race is rhythmic guitar albert is drums and crutchie is bass guitar#spot elmer bart hotshot and myron are in a band called Brooklyn Rising#(same generator website gave me Brooklyn Lies Union and Brooklyn Part Kings Maximum and it was so hard to resist)#spot is drums elmer is vocals bart is rhythm guitar hotshot is lead guitar and myron is bass guitar#there's a bi annual battle of the bands at this shitty diner on the Brooklyn side of the bridge#Brooklyn Rising has won every single year since they formed#but spot meets race at that diner for a little date and race sees a flyer so he tells jack about it and they enter#spot is peeved but he knows he would have done the same thing in Race's position#theres high intensity between the two bands (even though the prize is just milkshakes)#when the day finally rolls around santa fe strikes again wins#fast forward a few months it comes out Katherine's dad paid off the judges#she had no idea but no one believes her so jack dumps her and they kick her out of the band#albert was already having a less than ideal time mentally and this whole ordeal pushed him to take a little hiatus#meaning santa fe strikes again needs a new drummer for the time being cuz they have gigs to play#jack finds the new kid (Davey) playing drums during his free period and convinces him to join#it takes some doing but he does it#battle of the bands rolls around and a bunch of drama happens that#I can't get into cuz I'm out of tags#its still in early stages but ill publish someday#Probably#the Delancey brothers are sprinkled in too#Katherine and Davey are both song writers#Brooklyn Rising wears eyeliner to all their gigs

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

What Is The End Of An Era?

Trebek Remembered For Grace That Elevated Him Above Tv Host

George Alexander Trebek has been the host of Jeopardy! since the syndicated debut of America's Favorite Quiz Show® in 1984. He has become one of television's most enduring and iconic figures, engaging millions of viewers worldwide with his impeccable delivery of “answers and questions.”

— By Lynn Elber | Associated Press | November 8, 2020

LOS ANGELES (AP) — Alex Trebek never pretended to have all the answers, but the “Jeopardy!” host became an inspiration and solace to Americans who otherwise are at odds with each other.

He looked and sounded the part of a senior statesman, impeccably suited and groomed and with an authoritative voice any politician would covet. He commanded his turf — the quiz show’s stage — but refused to overshadow its brainy contestants.

And when he faced the challenge of pancreatic cancer, which claimed his life Sunday at age 80, he was honest, optimistic and graceful. Trebek died at his Los Angeles home, surrounded by family and friends, “Jeopardy!” studio Sony said.

The Canadian-born host made a point of informing fans about his health directly, in a series of brief online videos. He faced the camera and spoke in a calm, even tone as he revealed his illness and hope for a cure in the first message, posted in March 2019.

“Now normally, the prognosis for this is not very encouraging, but I’m going to fight this and I’m going to keep working,” Trebek said, even managing a wisecrack: He had to beat the disease because his “Jeopardy!” contract had three more years to run.

Trebek’s death came less than four months after that of civil rights leader and U.S. Rep. John Lewis, also of advanced pancreatic cancer and at age 80. Trebek had offered him words of encouragement last January.

In a memoir published this year, “The Answer Is ... Reflections on My Life,” Trebek suggested that he’s known but not celebrated, and compared himself to a visiting relative who TV viewers find “comforting and reassuring as opposed to being impressed by me.”

That was contradicted Sunday by the messages of grief and respect from former contestants, celebrities and the wider public that quickly followed news of his loss.

“Alex wasn’t just the best ever at what he did. He was also a lovely and deeply decent man, and I’m grateful for every minute I got to spend with him,” tweeted “Jeopardy!” champion Ken Jennings. “Thinking today about his family and his Jeopardy! family — which, in a way, included millions of us.”

“It was one of the great privileges of my life to spend time with this courageous man while he fought the battle of his life. You will never be replaced in our hearts, Alex,” James Holzhauer, another “Jeopardy!” star, posted on Twitter.

Recent winner Burt Thakur tweeted that he was “overwhelmed with emotion.” When he appeared on Friday’s show, Thakur recounted learning English diction as a child from watching Trebek on “Jeopardy!” with his grandfather.

The program tapes weeks of shows in advance, and the remaining episodes with Trebek will air through Dec. 25, a Sony spokeswoman said.

“Jeopardy!” bills itself as “America’s favorite quiz show” and captivated the public with a unique format in which contestants were told the answers and had to provide the questions on a variety of subjects, including movies, politics, history and popular culture.

They would answer by saying “What is ... ?” or “Who is .... ?”

In November 2019, one contestant expressed what many Jeopardy! fans were feeling: For his "Final Jeopardy!" answer, Dhruv Gaur wagered $1,995 on his answer: "What is We ❤ you, Alex!"

Trebek, who became its host in 1984, was a master of the format, engaging in friendly banter with contestants, appearing genuinely pleased when they answered correctly and, at the same time, moving the game along in a brisk no-nonsense fashion whenever people struggled for answers.

“I try not to take myself too seriously,” he told an interviewer in 2004. “I don’t want to come off as a pompous ass and indicate that I know everything when I don’t.”

The show was the brainstorm of Julann Griffin, wife of the late talk show host-entrepreneur Merv Griffin, who said she suggested to him one day that he create a game show where people were given the answers.

“Jeopardy!” debuted on NBC in 1964 with Art Fleming as emcee and was an immediate hit. It lasted until 1975, then was revived in syndication with Trebek.

Long identified by a full head of hair and trim mustache (though in 2001 he startled viewers by shaving his mustache, “completely on a whim”), Trebek was more than qualified for the job, having started his game show career on “Reach for the Top” in his native country.

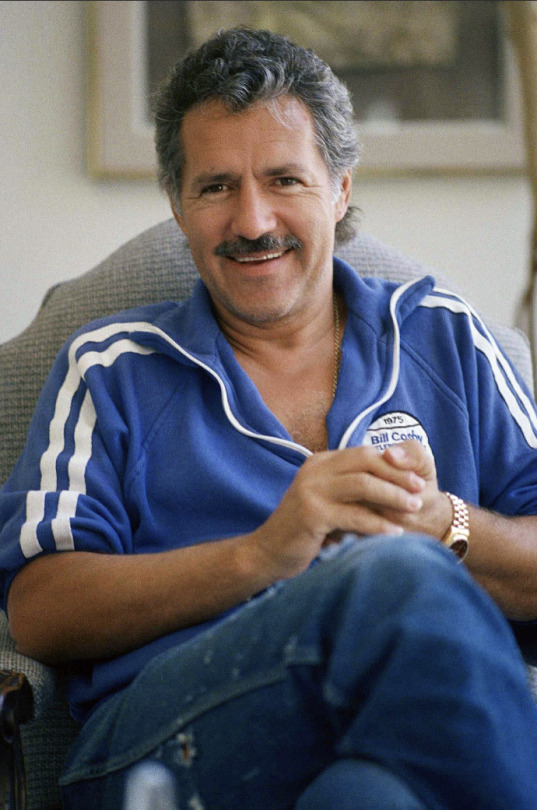

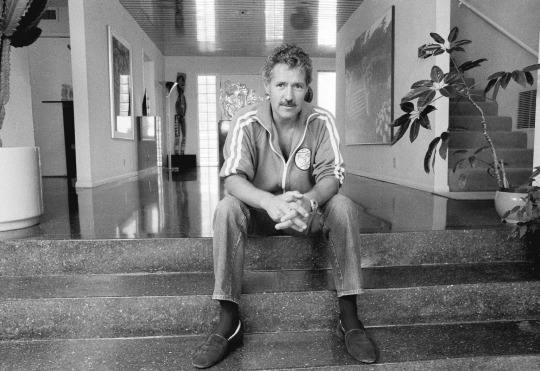

George Alexander Trebek began hosting Jeopardy! in 1984. He is shown above in his Los Angeles home in 1988. Alan Greth/AP

Moving to the U.S. in 1973, he appeared on “The Wizard of Odds,” “High Rollers,” “The $128,000 Question” and “Double Dare.” Even during his run on “Jeopardy!”, Trebek worked on other shows. In the early 1990s, he was the host of three — “Jeopardy!”, “To Tell the Truth” and “Classic Concentration.”

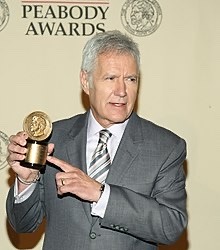

“Jeopardy!” made him famous. He won five Emmys as its host, including one last June, and received stars on both the Hollywood and Canadian walks of fame. In 2012, the show won a prestigious Peabody Award.

He taped his daily “Jeopardy!” shows at a frenetic pace, recording as many as 10 episodes (two weeks’ worth) in just two days. After what was described as a mild heart attack in 2007, he was back at work in just a month.

He posted a video in January 2018 announcing he’d undergone surgery for blood clots on the brain that followed a fall he’d taken. The show was on hiatus during his recovery.

It had yet to bring in a substitute host for Trebek — save once, when he and “Wheel of Fortune” host Pat Sajak swapped their TV jobs as an April’s Fool prank.

In 2012, Trebek acknowledged that he was considering retirement, but had been urged by friends to stay on so he could reach 30 years on the show. He still loved the job, he declared: “What’s not to love? You have the security of a familiar environment, a familiar format, but you have the excitement of new clues and new contestants on every program. You can’t beat that!”

Although many viewers considered him one of the key reasons for the show’s success, Trebek himself insisted he was only there to keep things moving.

“My job is to provide the atmosphere and assistance to the contestants to get them to perform at their very best,” he said in a 2012 interview. “And if I’m successful doing that, I will be perceived as a nice guy and the audience will think of me as being a bit of a star. But not if I try to steal the limelight!”

In a January 2019 interview with The Associated Press, Trebek discussed his decision to keep going with “Jeopardy!”

“It’s not as if I’m overworked — we tape 46 days a year,” he said. But he acknowledged he would retire someday, if he lost his edge or the job was no longer fun, adding: “And it’s still fun.”

Trebek said he hated to see contestants lose for forgetting to phrase their answers as questions. "I'm there to see that the contestants do as well as they can within the context of the rules," he told Fresh Air's Terry Gross in 1987. Above, Trebek poses on the set in April 2010. Amanda Edwards/Getty Images

Born July 22, 1940, in Sudbury, Ontario, Trebek was sent off to boarding school by his Ukrainian father and French-Canadian mother when he was barely in his teens.

After graduating high school, he spent a summer in Cincinnati to be close to a girlfriend, then returned to Canada to attend college. After earning a philosophy degree from the University of Ottawa, he went to work for the Canadian Broadcasting Co., starting as a staff announcer and eventually becoming a radio and TV reporter.

He became a U.S. citizen in 1997. Trebek’s first marriage, to Elaine Callei, ended in divorce. In 1990, he married Jean Currivan, and they had two children, Emily and Matthew.

Trebek is survived by his wife, their two children and his stepdaughter, Nicky.

The Order of Canada (French: Ordre du Canada) is a Canadian national order and the second highest honour for merit in the system of orders, decorations, and medals of Canada, after the Order of Merit. Alex Trebek was awarded on November 17, 2017

Trebek was proud of the Peabody Award received by Jeopardy! in 2012 (left), Trebek at Kadena Air Base, Okinawa, Japan, on March 31, 2007 (right)

0 notes

Text

The answer to lactose intolerance might be in Mongolia

Mongolians subsist on a dairy-heavy diet, even though most are lactose intolerant. (Matthäus Rest/)

Lake Khövsgöl is about as far north of the Mongolian capital of Ulaanbaatar as you can get without leaving the country. If you’re too impatient for the 13-hour bus ride, you can take a prop plane to the town of Murun, then drive for three hours on dirt roads to Khatgal, a tiny village nestled against the lake’s southern shore. The felt yurts that dot the surrounding green plains are a throwback to the days—not so long ago—when most Mongolians lived as subsistence herders.

In July 2017, archaeogeneticist Christina Warinner headed there to learn about the population’s complex relationship with milk. In Khatgal, she found a cooperative called Blessed by Yak, where families within a few hours’ drive pooled the bounty from their cows, goats, sheep, and yaks to supply tourists with heirloom dairy products.

Warinner watched for hours as Blessed by Yak members transformed the liquid into a dizzying array of foods. Milk was everywhere in and around these homes: splashing from swollen udders into wooden buckets, simmering in steel woks atop fires fueled by cow dung, hanging in leather bags from riblike wooden rafters, bubbling in specially made stills, crusting as spatters on the wood-lattice inner walls. The women even washed their hands in whey. “Working with herders is a five-senses experience,” Warinner says. “The taste is really strong; the smell is really strong. It reminds me of when I was nursing my daughter, and everything smelled of milk.”

Each family she visited had a half-dozen dairy products or more in some stage of production around a central hearth. And horse herders who came to sell their goods brought barrels of airag, a slightly alcoholic fizzy beverage that set the yurts abuzz.

Airag, made only from horse milk, is not to be confused with aaruul, a sour cheese, created from curdled milk, that gets so hard after weeks drying in the sun that you’re better off sucking on it or softening it in tea than risking your teeth trying to chew it. Easier to consume is byaslag, rounds of white cheese pressed between wooden boards. Roasted curds called eezgi look a little like burnt popcorn; dry, they last for months stored in cloth bags. Carefully packed in a sheep-stomach wrapper, the buttery clotted cream known as urum—made from fat-rich yak or sheep milk—will warm bellies all through the winter, when temperatures regularly drop well below zero.

Warinner’s personal favorite? The “mash” left behind when turning cow or yak milk into an alcoholic drink called shimin arkhi. “At the bottom of the still, you have an oily yogurt that’s delicious,” she says.

Her long trip to Khatgal wasn’t about culinary curiosity, however. Warinner was there to solve a mystery: Despite the dairy diversity she saw, an estimated 95 percent of Mongolians are, genetically speaking, lactose intolerant. Yet, in the frost-free summer months, she believes they may be getting up to half their calories from milk products.

Scientists once thought dairying and the ability to drink milk went hand in hand. What she found in Mongolia has pushed Warinner to posit a new explanation. On her visit to Khatgal, she says, the answer was all around her, even if she couldn’t see it.

Sitting, transfixed, in homes made from wool, leather, and wood, she was struck by the contrast with the plastic and steel kitchens she was familiar with in the US and Europe. Mongolians are surrounded by microscopic organisms: the bacteria that ferment the milk into their assorted foodstuffs, the microbes in their guts and on the dairy-soaked felt of their yurts. The way these invisible creatures interact with each other, with the environment, and with our bodies creates a dynamic ecosystem.

That’s not unique. Everyone lives with a billions-strong universe of microbes in, on, and around them. Several pounds’ worth thrive in our guts alone. Researchers have dubbed this wee world the microbiome and are just beginning to understand the role it plays in our health.

Some of these colonies, though, are more diverse than others: Warinner is still working on sampling the Khatgal herders’ microbiomes, but another team has already gathered evidence that the Mongolian bacterial makeup differs from those found in more-industrial areas of the world. Charting the ecosystem they are a part of might someday help explain why the population is able to eat so much dairy—and offer clues to help people everywhere who are lactose intolerant.

Warinner argues that a better understanding of the complex microbial universe inhabiting every Mongolian yurt could also provide insight into a problem that goes far beyond helping folks eat more brie. As communities around the world abandon traditional lifestyles, so-called diseases of civilization, like dementia, diabetes, and food intolerances, are on the rise.

Warinner is convinced that the Mongolian affinity for dairy is made possible by a mastery of bacteria 3,000 years or more in the making. By scraping gunk off the teeth of steppe dwellers who died thousands of years ago, she’s been able to prove that milk has held a prominent place in the Mongolian diet for millennia. Understanding the differences between traditional microbiomes like theirs and those prevalent in the industrialized world could help explain the illnesses that accompany modern lifestyles—and perhaps be the beginning of a different, more beneficial approach to diet and health.

Nowadays, Warinner does her detective work at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History’s ancient DNA lab, situated on the second floor of a high-rise bioscience facility overlooking the historic center of the medieval town of Jena, Germany. To prevent any errant DNA from contaminating its samples, entering the lab involves a half-hour protocol, including disinfection of foreign objects, and putting on head-to-toe Tyvek jumpsuits, surgical face masks, and eye shields. Inside, postdocs and technicians wielding drills and picks harvest fragments of dental plaque from the teeth of people who died long ago. It’s here that many of Warinner’s Mongolian specimens get cataloged, analyzed, and archived.

Her path to the lab began in 2010, when she was a postdoctoral researcher in Switzerland. Warinner was looking for ways to find evidence of infectious disease on centuries-old skeletons. She started with dental caries, or cavities—spots where bacteria had burrowed into the tooth enamel. To get a good look, she spent a lot of time clearing away plaque: mineral deposits scientists call “calculus,” and that, in the absence of modern dentistry, accumulate on teeth in an unsightly brown mass.

Around the same time, Amanda Henry, now a researcher at the University of Leiden in the Netherlands, put calculus scraped from Neanderthal teeth under the microscope and spotted starch grains trapped in the mineral layers. The results provided evidence that the population ate a diverse diet that included plants as well as meat.

Hearing about the work, Warinner wondered if looking at specimens from a medieval German cemetery might yield similar insights. But when she checked for food remains under the microscope, masses of perfectly preserved bacteria blocked her from doing so. “They were literally in your way, obscuring your view,” she recalls. The samples were teeming with microbial and human genes, preserved and protected by a hard mineral matrix.

Warinner had discovered a way to see the tiny organisms in the archaeological record, and with them, a means to study diet. “I realized this was a really rich source of bacterial DNA no one had thought of before,” Warinner says. “It’s a time capsule that gives us access to information about an individual’s life that is very hard to get from other places.”

The dental calculus research dovetailed with rising interest in the microbiome, rocketing Warinner to a coveted position at Max Planck. (In 2019, Harvard hired her as an anthropology professor, and she now splits her time between Cambridge, Massachusetts, and Jena, overseeing labs on two continents.) Her TED talks have racked up more than 2 million views. “I never expected to have an entire career based on something people spend lots of time and money trying to get rid of,” she quips.

That grimy dental buildup, Warinner has learned, preserves more than just DNA. In 2014, she published a study in which she and her colleagues looked at the teeth of Norse Greenlanders, seeking insight into why Vikings abandoned their settlements there after just a few hundred years. She found milk proteins suspended in the plaque of the area’s earliest settlers—and almost none in that of people buried five centuries later. “We had a marker to trace dairy consumption,” Warinner says.

This discovery led Warinner to turn to one of the biggest puzzles in recent human evolution: Why milk? Most people in the world aren’t genetically equipped to digest dairy as adults. A minority of them—including most northern Europeans—have one of several mutations that allows their bodies to break down the key sugar in milk, lactose, beyond early childhood. That ability is called lactase persistence, after the protein that processes lactose.

Until recently, geneticists thought that dairying and the ability to drink milk must have evolved together, but that didn’t prove out when investigators went looking for evidence. Ancient DNA samples from all across Europe suggest that even in places where lactase persistence is common today, it didn’t appear until 3000 BCE—long after people domesticated cattle and sheep and started consuming dairy products. For 4,000 years prior to the mutation, Europeans were making cheese and eating dairy despite their lactose intolerance. Warinner guessed that microbes may have been doing the job of dairy digestion for them.

To prove it, she began looking for places where the situation was similar. Mongolia made sense: There’s evidence that herding and domestication there dates back 5,000 years or more. But, Warinner says, direct evidence of long-ago dairy consumption was absent—until ancient calculus let her harvest it straight from the mouths of the dead.

Ancient plaque shows Mongolians have eaten dairy for millennia. (Courtesy Christina Warinner/)

Starting in 2016, in her Jena lab, Warinner and her team scraped the teeth of skeletons buried on the steppes thousands of years ago and excavated by archaeologists in the 1990s. Samples about the size of a lentil were enough to reveal proteins from cow, goat, and sheep milk. By tapping the same remains for ancient DNA, Warinner could go one step further and show that they belonged to people who lacked the gene to digest lactose—just like modern Mongolians do.

Samples of the microbiome from in and around today’s herders, Warinner realized, might offer a way to understand how this was possible. Though it’s estimated that just 1 in 20 Mongolians has the mutation allowing them to digest milk, few places in the world put as much emphasis on dairy. They include it in festivities and offer it to spirits before any big trip to ensure safety and success. Even their metaphors are dairy-based: “The smell from a wooden vessel filled with milk never goes away” is the rough equivalent of “old habits die hard.”

Down the hall from the ancient DNA lab, thousands of microbiome samples the team has collected over the past two summers pack tall industrial freezers. Chilled to minus 40 degrees F—colder, even, than the Mongolian winter—the collection includes everything from eezgi and byaslag to goat turds and yak-udder swabs. Hundreds of the playing-card-size plastic baggies new mothers use to freeze breast milk contain raw, freshly squeezed camel, cow, goat, reindeer, sheep, and yak milk.

Warinner’s initial hypothesis was that the Mongolian herders—past and present—were using lactose-eating microbes to break down their many varieties of dairy, making it digestible. Commonly known as fermentation, it’s the same bacteria-assisted process that turns malt into beer, grapes into wine, and flour into bubbly sourdough.

Fermentation is integral to just about every dairy product in the Mongolian repertoire. While Western cheeses also utilize the process, makers of Parmesan, brie and Camembert all rely on fungi and rennet—an enzyme from the stomachs of calves—to get the right texture and taste. Mongolians, on the other hand, maintain microbial cultures called starters, saving a little from each batch to inoculate the next.

Ethnographic evidence suggests that these preparations have been around a very, very long time. In Mongolian, they’re called khöröngö, a word that’s derived from the term for wealth or inheritance. They are living heirlooms, typically passed from mother to daughter. And they require regular care and feeding. “Starter cultures get constant attention over weeks, months, years, generations,” says Björn Reichhardt, a Mongolian-speaking ethnographer at Max Planck and member of Warinner’s team responsible for collecting most of the samples in the Jena freezers. “Mongolians tend to dairy products the way they would an infant.” As with a child, the environment in which they’re nurtured is deeply influential. The microbial makeup of each family’s starters seems to be subtly different.

After returning from Khatgal in 2017, Warinner launched the Heirloom Microbe project to identify and catalog the bacteria the herders were using to make their dairy products. The name reflected her hope that the yurts harbored strains or species ignored by industrial labs and corporate starter-culture manufacturers. Perhaps, Warinner imagined, there would be a novel strain or some combination of microbes Mongolians were using to process milk in a way that Western science had missed.

So far, she’s found Enterococcus, a bacterium common in the human gut that excels at digesting lactose but was eliminated from US and European dairy commodities decades ago. And they’ve spotted some new strains of familiar bacteria like Lactobacillus. But they haven’t identified any radically different species or starters—no magic microbes ready to package in pill form. “It doesn’t seem like there is a range of superbugs in there,” says Max Planck anthropologist Matthäus Rest, who works with Warinner on dairy research.

The reality might be more daunting. Rather than a previously undiscovered strain of microbes, it might be a complex web of organisms and practices—the lovingly maintained starters, the milk-soaked felt of the yurts, the gut flora of individual herders, the way they stir their barrels of airag—that makes the Mongolian love affair with so many dairy products possible.

Warinner’s project now has a new name, Dairy Cultures, reflecting her growing realization that Mongolia’s microbial toolkit might not come down to a few specific bacteria. “Science is often very reductive,” she says. “People tend to look at just one aspect of things. But if we want to understand dairying, we can’t just look at the animals, or the microbiome, or the products. We have to look at the entire system.”

The results could help explain another phenomenon, one that affects people far from the Mongolian steppes. The billions of bacteria that make up our microbiomes aren’t passive passengers. They play an active—if little understood—role in our health, helping regulate our immune systems and digest our food.

Over the past two centuries, industrialization, sterilization, and antibiotics have dramatically changed these invisible ecosystems. Underneath a superficial diversity of flavors—mall staples like sushi, pad thai, and pizza—food is becoming more and more the same. Large-scale dairies even ferment items like yogurt and cheese using lab-grown starter cultures, a $1.2 billion industry dominated by a handful of industrial producers. People eating commoditized cuisine lack an estimated 30 percent of the gut microbe species that are found in remote groups still eating “traditional” diets. In 2015, Warinner was part of a team that found bacteria in the digestive tracts of hunter-gatherers living in the Amazon jungle that have all but vanished in people consuming a selection of typical Western fare.

“People have the feeling that they eat a much more diverse and global diet than their parents, and that might be true,” Rest says, “but when you look at these foods on a microbial level, they’re increasingly empty.”

A review paper in Science in October 2019 gathered data from labs around the world beginning to probe if this dwindling variety might be making us sick. Dementia, diabetes, heart disease, stroke, and certain cancers are sometimes termed diseases of civilization. They’re all associated with the spread of urban lifestyles and diets, processed meals, and antibiotics. Meanwhile, food intolerances and intestinal illnesses like Crohn’s disease and irritable bowel disease are on the rise.

Comparing the microbiome of Mongolian herders to samples from people consuming a more industrialized diet elsewhere in the world could translate into valuable insights into what we’ve lost—and how to get it back. Identifying the missing species could refine human microbiome therapies and add a needed dose of science to probiotics.

There might not be much time left for this quest. Over the past 50 years, hundreds of thousands of Mongolian herders have abandoned the steppes, their herds, and their traditional lifestyle, flocking to Ulaanbaatar. Around 50 percent of the country’s population, an estimated 1.5 million people, now crowds into the capital.

In summer 2020, Warinner’s team will return to Khatgal and other rural regions to collect mouth swabs and fecal specimens from herders, the last phase in cataloging the traditional Mongolian micro-biome. She recently decided she’ll sample residents of Ulaanbaatar too, to see how urban dwelling is altering their bacterial balances as they adopt new foods, new ways of life, and, in all likelihood, newly simplified communities of microbes.

Something important, if invisible, is being lost, Warinner believes. On a recent fall morning, she was sitting in her sunlit office in the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnography on Harvard’s campus. Mostly unpacked from her latest trans-Atlantic move, she was contemplating a creeping, yurt-by-yurt extinction event.

It’s a conundrum vastly different in size, but not in scale, from those facing wildlife conservationists the world over. “How do you restore an entire ecology?” she wondered. “I’m not sure you can. We’re doing our best to record, catalog, and document as much as we can, and try to figure it out at the same time.”

Preserving Mongolia’s microbes, in other words, won’t be enough. We also need the traditional knowledge and everyday practices that have sustained them for centuries. Downstairs, display cases hold the artifacts of other peoples—from the Massachusett tribe that once lived on the land where Harvard now stands to the Aztec and Inca civilizations that used to rule vast stretches of Central and South America—whose traditions are gone forever, along with the microbial networks they nurtured. “Dairy systems are alive,” Warinner says. “They’ve been alive, and continuously cultivated, for 5,000 years. You have to grow them every single day. How much change can the system tolerate before it begins to break?”

This story appears in the Spring 2020, Origins issue of Popular Science.

0 notes

Text

The answer to lactose intolerance might be in Mongolia

Mongolians subsist on a dairy-heavy diet, even though most are lactose intolerant. (Matthäus Rest/)

Lake Khövsgöl is about as far north of the Mongolian capital of Ulaanbaatar as you can get without leaving the country. If you’re too impatient for the 13-hour bus ride, you can take a prop plane to the town of Murun, then drive for three hours on dirt roads to Khatgal, a tiny village nestled against the lake’s southern shore. The felt yurts that dot the surrounding green plains are a throwback to the days—not so long ago—when most Mongolians lived as subsistence herders.

In July 2017, archaeogeneticist Christina Warinner headed there to learn about the population’s complex relationship with milk. In Khatgal, she found a cooperative called Blessed by Yak, where families within a few hours’ drive pooled the bounty from their cows, goats, sheep, and yaks to supply tourists with heirloom dairy products.

Warinner watched for hours as Blessed by Yak members transformed the liquid into a dizzying array of foods. Milk was everywhere in and around these homes: splashing from swollen udders into wooden buckets, simmering in steel woks atop fires fueled by cow dung, hanging in leather bags from riblike wooden rafters, bubbling in specially made stills, crusting as spatters on the wood-lattice inner walls. The women even washed their hands in whey. “Working with herders is a five-senses experience,” Warinner says. “The taste is really strong; the smell is really strong. It reminds me of when I was nursing my daughter, and everything smelled of milk.”

Each family she visited had a half-dozen dairy products or more in some stage of production around a central hearth. And horse herders who came to sell their goods brought barrels of airag, a slightly alcoholic fizzy beverage that set the yurts abuzz.

Airag, made only from horse milk, is not to be confused with aaruul, a sour cheese, created from curdled milk, that gets so hard after weeks drying in the sun that you’re better off sucking on it or softening it in tea than risking your teeth trying to chew it. Easier to consume is byaslag, rounds of white cheese pressed between wooden boards. Roasted curds called eezgi look a little like burnt popcorn; dry, they last for months stored in cloth bags. Carefully packed in a sheep-stomach wrapper, the buttery clotted cream known as urum—made from fat-rich yak or sheep milk—will warm bellies all through the winter, when temperatures regularly drop well below zero.

Warinner’s personal favorite? The “mash” left behind when turning cow or yak milk into an alcoholic drink called shimin arkhi. “At the bottom of the still, you have an oily yogurt that’s delicious,” she says.

Her long trip to Khatgal wasn’t about culinary curiosity, however. Warinner was there to solve a mystery: Despite the dairy diversity she saw, an estimated 95 percent of Mongolians are, genetically speaking, lactose intolerant. Yet, in the frost-free summer months, she believes they may be getting up to half their calories from milk products.

Scientists once thought dairying and the ability to drink milk went hand in hand. What she found in Mongolia has pushed Warinner to posit a new explanation. On her visit to Khatgal, she says, the answer was all around her, even if she couldn’t see it.

Sitting, transfixed, in homes made from wool, leather, and wood, she was struck by the contrast with the plastic and steel kitchens she was familiar with in the US and Europe. Mongolians are surrounded by microscopic organisms: the bacteria that ferment the milk into their assorted foodstuffs, the microbes in their guts and on the dairy-soaked felt of their yurts. The way these invisible creatures interact with each other, with the environment, and with our bodies creates a dynamic ecosystem.

That’s not unique. Everyone lives with a billions-strong universe of microbes in, on, and around them. Several pounds’ worth thrive in our guts alone. Researchers have dubbed this wee world the microbiome and are just beginning to understand the role it plays in our health.

Some of these colonies, though, are more diverse than others: Warinner is still working on sampling the Khatgal herders’ microbiomes, but another team has already gathered evidence that the Mongolian bacterial makeup differs from those found in more-industrial areas of the world. Charting the ecosystem they are a part of might someday help explain why the population is able to eat so much dairy—and offer clues to help people everywhere who are lactose intolerant.

Warinner argues that a better understanding of the complex microbial universe inhabiting every Mongolian yurt could also provide insight into a problem that goes far beyond helping folks eat more brie. As communities around the world abandon traditional lifestyles, so-called diseases of civilization, like dementia, diabetes, and food intolerances, are on the rise.

Warinner is convinced that the Mongolian affinity for dairy is made possible by a mastery of bacteria 3,000 years or more in the making. By scraping gunk off the teeth of steppe dwellers who died thousands of years ago, she’s been able to prove that milk has held a prominent place in the Mongolian diet for millennia. Understanding the differences between traditional microbiomes like theirs and those prevalent in the industrialized world could help explain the illnesses that accompany modern lifestyles—and perhaps be the beginning of a different, more beneficial approach to diet and health.

Nowadays, Warinner does her detective work at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History’s ancient DNA lab, situated on the second floor of a high-rise bioscience facility overlooking the historic center of the medieval town of Jena, Germany. To prevent any errant DNA from contaminating its samples, entering the lab involves a half-hour protocol, including disinfection of foreign objects, and putting on head-to-toe Tyvek jumpsuits, surgical face masks, and eye shields. Inside, postdocs and technicians wielding drills and picks harvest fragments of dental plaque from the teeth of people who died long ago. It’s here that many of Warinner’s Mongolian specimens get cataloged, analyzed, and archived.

Her path to the lab began in 2010, when she was a postdoctoral researcher in Switzerland. Warinner was looking for ways to find evidence of infectious disease on centuries-old skeletons. She started with dental caries, or cavities—spots where bacteria had burrowed into the tooth enamel. To get a good look, she spent a lot of time clearing away plaque: mineral deposits scientists call “calculus,” and that, in the absence of modern dentistry, accumulate on teeth in an unsightly brown mass.

Around the same time, Amanda Henry, now a researcher at the University of Leiden in the Netherlands, put calculus scraped from Neanderthal teeth under the microscope and spotted starch grains trapped in the mineral layers. The results provided evidence that the population ate a diverse diet that included plants as well as meat.

Hearing about the work, Warinner wondered if looking at specimens from a medieval German cemetery might yield similar insights. But when she checked for food remains under the microscope, masses of perfectly preserved bacteria blocked her from doing so. “They were literally in your way, obscuring your view,” she recalls. The samples were teeming with microbial and human genes, preserved and protected by a hard mineral matrix.

Warinner had discovered a way to see the tiny organisms in the archaeological record, and with them, a means to study diet. “I realized this was a really rich source of bacterial DNA no one had thought of before,” Warinner says. “It’s a time capsule that gives us access to information about an individual’s life that is very hard to get from other places.”

The dental calculus research dovetailed with rising interest in the microbiome, rocketing Warinner to a coveted position at Max Planck. (In 2019, Harvard hired her as an anthropology professor, and she now splits her time between Cambridge, Massachusetts, and Jena, overseeing labs on two continents.) Her TED talks have racked up more than 2 million views. “I never expected to have an entire career based on something people spend lots of time and money trying to get rid of,” she quips.

That grimy dental buildup, Warinner has learned, preserves more than just DNA. In 2014, she published a study in which she and her colleagues looked at the teeth of Norse Greenlanders, seeking insight into why Vikings abandoned their settlements there after just a few hundred years. She found milk proteins suspended in the plaque of the area’s earliest settlers—and almost none in that of people buried five centuries later. “We had a marker to trace dairy consumption,” Warinner says.

This discovery led Warinner to turn to one of the biggest puzzles in recent human evolution: Why milk? Most people in the world aren’t genetically equipped to digest dairy as adults. A minority of them—including most northern Europeans—have one of several mutations that allows their bodies to break down the key sugar in milk, lactose, beyond early childhood. That ability is called lactase persistence, after the protein that processes lactose.

Until recently, geneticists thought that dairying and the ability to drink milk must have evolved together, but that didn’t prove out when investigators went looking for evidence. Ancient DNA samples from all across Europe suggest that even in places where lactase persistence is common today, it didn’t appear until 3000 BCE—long after people domesticated cattle and sheep and started consuming dairy products. For 4,000 years prior to the mutation, Europeans were making cheese and eating dairy despite their lactose intolerance. Warinner guessed that microbes may have been doing the job of dairy digestion for them.

To prove it, she began looking for places where the situation was similar. Mongolia made sense: There’s evidence that herding and domestication there dates back 5,000 years or more. But, Warinner says, direct evidence of long-ago dairy consumption was absent—until ancient calculus let her harvest it straight from the mouths of the dead.

Ancient plaque shows Mongolians have eaten dairy for millennia. (Courtesy Christina Warinner/)

Starting in 2016, in her Jena lab, Warinner and her team scraped the teeth of skeletons buried on the steppes thousands of years ago and excavated by archaeologists in the 1990s. Samples about the size of a lentil were enough to reveal proteins from cow, goat, and sheep milk. By tapping the same remains for ancient DNA, Warinner could go one step further and show that they belonged to people who lacked the gene to digest lactose—just like modern Mongolians do.

Samples of the microbiome from in and around today’s herders, Warinner realized, might offer a way to understand how this was possible. Though it’s estimated that just 1 in 20 Mongolians has the mutation allowing them to digest milk, few places in the world put as much emphasis on dairy. They include it in festivities and offer it to spirits before any big trip to ensure safety and success. Even their metaphors are dairy-based: “The smell from a wooden vessel filled with milk never goes away” is the rough equivalent of “old habits die hard.”

Down the hall from the ancient DNA lab, thousands of microbiome samples the team has collected over the past two summers pack tall industrial freezers. Chilled to minus 40 degrees F—colder, even, than the Mongolian winter—the collection includes everything from eezgi and byaslag to goat turds and yak-udder swabs. Hundreds of the playing-card-size plastic baggies new mothers use to freeze breast milk contain raw, freshly squeezed camel, cow, goat, reindeer, sheep, and yak milk.

Warinner’s initial hypothesis was that the Mongolian herders—past and present—were using lactose-eating microbes to break down their many varieties of dairy, making it digestible. Commonly known as fermentation, it’s the same bacteria-assisted process that turns malt into beer, grapes into wine, and flour into bubbly sourdough.

Fermentation is integral to just about every dairy product in the Mongolian repertoire. While Western cheeses also utilize the process, makers of Parmesan, brie and Camembert all rely on fungi and rennet—an enzyme from the stomachs of calves—to get the right texture and taste. Mongolians, on the other hand, maintain microbial cultures called starters, saving a little from each batch to inoculate the next.

Ethnographic evidence suggests that these preparations have been around a very, very long time. In Mongolian, they’re called khöröngö, a word that’s derived from the term for wealth or inheritance. They are living heirlooms, typically passed from mother to daughter. And they require regular care and feeding. “Starter cultures get constant attention over weeks, months, years, generations,” says Björn Reichhardt, a Mongolian-speaking ethnographer at Max Planck and member of Warinner’s team responsible for collecting most of the samples in the Jena freezers. “Mongolians tend to dairy products the way they would an infant.” As with a child, the environment in which they’re nurtured is deeply influential. The microbial makeup of each family’s starters seems to be subtly different.

After returning from Khatgal in 2017, Warinner launched the Heirloom Microbe project to identify and catalog the bacteria the herders were using to make their dairy products. The name reflected her hope that the yurts harbored strains or species ignored by industrial labs and corporate starter-culture manufacturers. Perhaps, Warinner imagined, there would be a novel strain or some combination of microbes Mongolians were using to process milk in a way that Western science had missed.

So far, she’s found Enterococcus, a bacterium common in the human gut that excels at digesting lactose but was eliminated from US and European dairy commodities decades ago. And they’ve spotted some new strains of familiar bacteria like Lactobacillus. But they haven’t identified any radically different species or starters—no magic microbes ready to package in pill form. “It doesn’t seem like there is a range of superbugs in there,” says Max Planck anthropologist Matthäus Rest, who works with Warinner on dairy research.

The reality might be more daunting. Rather than a previously undiscovered strain of microbes, it might be a complex web of organisms and practices—the lovingly maintained starters, the milk-soaked felt of the yurts, the gut flora of individual herders, the way they stir their barrels of airag—that makes the Mongolian love affair with so many dairy products possible.

Warinner’s project now has a new name, Dairy Cultures, reflecting her growing realization that Mongolia’s microbial toolkit might not come down to a few specific bacteria. “Science is often very reductive,” she says. “People tend to look at just one aspect of things. But if we want to understand dairying, we can’t just look at the animals, or the microbiome, or the products. We have to look at the entire system.”

The results could help explain another phenomenon, one that affects people far from the Mongolian steppes. The billions of bacteria that make up our microbiomes aren’t passive passengers. They play an active—if little understood—role in our health, helping regulate our immune systems and digest our food.

Over the past two centuries, industrialization, sterilization, and antibiotics have dramatically changed these invisible ecosystems. Underneath a superficial diversity of flavors—mall staples like sushi, pad thai, and pizza—food is becoming more and more the same. Large-scale dairies even ferment items like yogurt and cheese using lab-grown starter cultures, a $1.2 billion industry dominated by a handful of industrial producers. People eating commoditized cuisine lack an estimated 30 percent of the gut microbe species that are found in remote groups still eating “traditional” diets. In 2015, Warinner was part of a team that found bacteria in the digestive tracts of hunter-gatherers living in the Amazon jungle that have all but vanished in people consuming a selection of typical Western fare.

“People have the feeling that they eat a much more diverse and global diet than their parents, and that might be true,” Rest says, “but when you look at these foods on a microbial level, they’re increasingly empty.”

A review paper in Science in October 2019 gathered data from labs around the world beginning to probe if this dwindling variety might be making us sick. Dementia, diabetes, heart disease, stroke, and certain cancers are sometimes termed diseases of civilization. They’re all associated with the spread of urban lifestyles and diets, processed meals, and antibiotics. Meanwhile, food intolerances and intestinal illnesses like Crohn’s disease and irritable bowel disease are on the rise.

Comparing the microbiome of Mongolian herders to samples from people consuming a more industrialized diet elsewhere in the world could translate into valuable insights into what we’ve lost—and how to get it back. Identifying the missing species could refine human microbiome therapies and add a needed dose of science to probiotics.

There might not be much time left for this quest. Over the past 50 years, hundreds of thousands of Mongolian herders have abandoned the steppes, their herds, and their traditional lifestyle, flocking to Ulaanbaatar. Around 50 percent of the country’s population, an estimated 1.5 million people, now crowds into the capital.

In summer 2020, Warinner’s team will return to Khatgal and other rural regions to collect mouth swabs and fecal specimens from herders, the last phase in cataloging the traditional Mongolian micro-biome. She recently decided she’ll sample residents of Ulaanbaatar too, to see how urban dwelling is altering their bacterial balances as they adopt new foods, new ways of life, and, in all likelihood, newly simplified communities of microbes.

Something important, if invisible, is being lost, Warinner believes. On a recent fall morning, she was sitting in her sunlit office in the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnography on Harvard’s campus. Mostly unpacked from her latest trans-Atlantic move, she was contemplating a creeping, yurt-by-yurt extinction event.

It’s a conundrum vastly different in size, but not in scale, from those facing wildlife conservationists the world over. “How do you restore an entire ecology?” she wondered. “I’m not sure you can. We’re doing our best to record, catalog, and document as much as we can, and try to figure it out at the same time.”

Preserving Mongolia’s microbes, in other words, won’t be enough. We also need the traditional knowledge and everyday practices that have sustained them for centuries. Downstairs, display cases hold the artifacts of other peoples—from the Massachusett tribe that once lived on the land where Harvard now stands to the Aztec and Inca civilizations that used to rule vast stretches of Central and South America—whose traditions are gone forever, along with the microbial networks they nurtured. “Dairy systems are alive,” Warinner says. “They’ve been alive, and continuously cultivated, for 5,000 years. You have to grow them every single day. How much change can the system tolerate before it begins to break?”

This story appears in the Spring 2020, Origins issue of Popular Science.

0 notes

Link

Rebecca McCarthy | Longreads | Month 2018 | 10 minutes (2,519 words)

In May of 2017, Mayor de Blasio unveiled Jimmy Breslin Way, a street sign dedicating the stretch of 42nd Street between 2nd and 3rd Avenue to the late reporter. It was a strange press conference — half eulogy, half lecture — a chance for the mayor to laud Breslin and scold members of today’s media by whom he often feels unfairly maligned. “Think about what Jimmy Breslin did. Think about how he saw the world,” said de Blasio. He left without taking questions. What was he talking about? Did he imagine he and Jimmy Breslin would get along? In 1969 Breslin wrote a cover story about Mayor Lindsay for New York Magazine, “Is Lindsay Too Tall to Be Mayor?” was the title. Lindsay was an inch shorter than de Blasio.

In 2010, Heike Geissler took a temporary position at an Amazon warehouse in Leipzig. Geissler was a freelance writer and a translator but, more pressingly, she was the mother of two children and money was not coming in. Seasonal Associate, which was translated by Katy Derbyshire and released by Semiotext(e) this month, is the product of that job. (Read an excerpt on Longreads.) It’s an oppressive, unsettling book, mainly because the work is too familiar. The book is written almost entirely in the second person, a style that might’ve come off as an irritating affectation with a lesser writer or a different subject. Here, it’s terrifying — you feel yourself slipping along with Geissler, thoughts of your own unpaid bills and the cold at the back of your throat weaving their way through the narrative. It’s not just that this unnamed protagonist could be you, it’s the certainty that someday she will be you. “You’ll soon know something about life that you didn’t know before, and it won’t just have to do with work,” Geissler writes. “But also with the fact that you’re getting older, that two children cry after you every morning, that you don’t want to go to work, and that something about this job and many other kinds of jobs is essentially rotten.”

*

The question of who killed New York used to be up for debate. Was it John Lindsay, who couldn’t face reality, who covered the city’s debts with short-term, high interest loans he knew were impossible to repay? His successor, Abe Beame, who bent to the demands of the bankers and gutted the social safety net during the fiscal crisis of the 70’s? Ed Koch, who embraced Beame’s cuts wholeheartedly and mocked past mayors as men who wanted New York “to be the No. 1 welfare city in America”? Giuliani, who launched the deregulation of rent controlled apartments and the quality of life campaign that gave us Broken Windows and COMPSTAT? (I’m not mentioning David Dinkins, because I really don’t think David Dinkins brought us here.) Was it Hipsters and their attendant paraphernalia? Was it the McKibbin Lofts? Union Pool? Was it Shred Stuy?

Inventory work provides Geissler with a granular view of consumerism. Stripped of the marketing and storefronts that make it palatable it quickly begins to look like a form of mental illness. Who is buying these mugs, stamped with George Clooney’s face?

All New York City mayors are venal, but some are more venal than others. A few months ago, I would have told you Bloomberg was to blame, our bloodless, billionaire mayor, who rezoned the city’s most vulnerable neighborhoods and openly courted real estate investment from foreign billionaires. Rents rose at neat clip alongside the homeless population. To his credit, Bloomberg — a very short man — was always transparent about where his priorities lay. The city, he said, was a “luxury product” and it should behave that way.

De Blasio was supposed to be the antidote to the Bloomberg years, a progressive underdog who ran on universal pre-k and affordable housing. But that affordable housing has largely failed to materialize — where it’s been built, it’s often still pretty unaffordable — and his administration has been marked by disappointing half-measures and an ill-conceived plan for a ridiculous four billion dollar streetcar no one wants.

On Black Friday, Amazon workers staged mass walkouts across Europe. On Cyber Monday, led by community groups Make the Road New York and New York Communities for Change (NYCC), protestors stormed Amazon’s Midtown bookstore to protest the planned headquarters in Long Island City and later gathered in front of the LIC Civil Courthouse chanting “I stand in the rain, I stand in the snow, Amazon has got to go!” City Council members Jimmy Van Bremer, Jumanne Williams, and Melissa Mark-Vitero were all in attendance — Williams and Mark-Vitero, it should be noted, are both running for Public Advocate. All of them decried the incentives offered to Amazon, which total about 3 billion. Williams claimed they were steamrolled by the Mayor and Governor Cuomo and that while Cuomo’s betrayal was no surprise, the de Blasio administration was “the biggest waste of progressive capital [Williams had] ever seen.”

Kickstart your weekend reading by getting the week’s best Longreads delivered to your inbox every Friday afternoon.

Sign up

It might’ve been a good show of force, had not all of the aforementioned politicians signed the letter urging Amazon to build its headquarters in New York. What did they think was going to happen? A New York Times investigation released earlier this year showed that the city had lost 152,000 rent-regulated apartments since 1993. The subway system is crumbling, the state leads the nation in income inequality, and the homeless population is at an all time high. No reasonable human being could look around and conclude that the answer to all these problems is to give the most avaricious company in the world the keys to the city. Amazon swallows everything it touches, it isn’t interested in civic health. Only half of the jobs being brought in are in tech and many of the low level positions will likely be replaced by robots fairly soon, but for now, these are the jobs for which the Mayor sold the city. “At any rate,” Geissler writes, early on in Seasonal Associate, “it’s almost impossible not to be forced to your knees and into defiance by this job you’re about to have.”

*

Geissler was hired in the warehouse to handle the Christmas rush, hence the title, and the cold is so omnipresent it seems to be a feature of the company rather than simply the reality of winter. A gate that will not latch properly becomes a major antagonist and everyone is either ill or on the verge of falling ill, although they have been warned specifically against this. “Sick days hurt Amazon,” Geissler is told at her orientation. Precarity manifests as a constant, low-grade fever. You’re the protagonist but her voice leads you through the job, a tired Virgil navigating a new circle of hell. The work is inventory — entering items into the system so they can be purchased online and performing at least a cursory check to make sure they’re undamaged. “Everything exists, in case you were going to ask,” says Geissler. “Absolutely everything exists, and people can buy it all.” Despite the scale of the warehouse, inventory work provides Geissler with a granular view of consumerism. Stripped of the marketing and storefronts that make it palatable it quickly begins to look like a form of mental illness. Who is buying these mugs, stamped with George Clooney’s face? Who needs these pre-distressed Iron Maiden hats, already rags at point of purchase? Amazon customers, which is to say, all of us.

Geissler tried to sell the book as straightforward journalism initially and was turned down by five publishers, likely because book is largely boring. It’s a propulsive, weaponized banality though — something unnatural is going on here and it’s hard to see a way out.

Geissler isn’t the typical warehouse employee and as a temporary contractor she’s something of a tourist at Amazon. She’s well-educated, she’s white, she lives with the father of her children, and she’s normally able to make a living — however precarious — as a writer. There’s significant privilege there. Many people spend their entire lives working shitty, unforgiving jobs with arbitrary, infantilizing rules and part of the reason Geissler is so attuned to the myriad indignities of Amazon is because she’s unused to them. She’s aware of this position though. “It has to be said right away,” she writes, “that no one is suited for unhappiness, yet this fact doesn’t get enough recognition.” Seasonal Associate is a book about slippage and a sudden fall into the working class, but it’s a document of anxiety and futility rather than stunt journalism. The central rallying point in the warehouse is a desk made out of a door — a replica of Jeff Bezos’ desk when he founded Amazon; an absurd symbol of frugality and the company’s dedication to customer satisfaction over employees’ personal comfort. As if every warehouse worker has the potential to become the richest man in the world, if only they would stop buying such expensive desks. The idea that if you work hard enough you will inevitably rise out of poverty has always been a sham and Amazon has taken it to it’s logical endpoint. You work hard and nothing happens. You will never be good enough at your job, because you’re a human being, not a machine. As long as you’re alive you’re a potential problem for the company.

Local Bookstores Amazon

In order to maintain some sense of agency Geissler stages tiny acts of rebellion — refusing to hold a handrail despite the signs instructing her to hold the handrail, keeping her safety vest in her pocket until she absolutely has to put it on. The gestures are adolescent and effectively meaningless, but every time she’s snide it’s a relief — a sign of life. Much later, after her contract is finished, she recognizes a man in a parking lot who she described as Amazon’s “only hipster.” The last time she’d seen him he was docking people’s pay for what’s commonly known as time theft. They had lined up a few minutes early to leave work, rather than waiting, unpaid, to go through security. “Unable to think of anything better,” says Geissler. “Or because it seemed like the most appropriate idea, I called out the name of a book I’d just read, by Mark Greif and others. I yelled at him: What Was the Hipster! I called it twice and I thought then he might know he was over.”

Geissler tried to sell the book as straightforward journalism initially and was turned down by five publishers, likely because book is largely boring. It’s a propulsive, weaponized banality though — something unnatural is going on here and it’s hard to see a way out. “You’ve completely forgotten that you have a profession and are only here to alleviate momentary poverty,” Geissler writes, just after her interview at Amazon. “Something inside you is essentially unsettled and will never calm down again, even though you do get the job. From this point on, you are beside yourself with worry.”

My own mother raised two kids by herself as a high school English teacher and she took a number of side jobs to supplement her income. Tutoring, working at a bakery, working at a strange, luxury gardening store that sold copper birdhouses and rocks that said things like “LOVE” and “CREATE” for people who couldn’t. None of them were bad jobs, none as oppressive as warehouse work, but they did not pay very well. Her desk (worse than Jeff Bezos’) was just a slab of wood, perched atop two filing cabinets. She never made a big deal out of that though, because she is not an asshole. She’d wake up at four or five in the morning to grade the lousy papers of teenage Republicans and shovel the walkway, but she still tried to read to me and my brother before putting us to bed. Oftentimes she’d fall asleep mid-sentence and start mumbling about the electricity bill or replacing the boiler. Eventually, a doctor told her she had to relax — her blood pressure was dangerously high, her muscles so tense that when she breathed, her ribs barely moved.

If you think you’re immune to this — if you went to college, if you believe you’re upwardly mobile, if you imagine you will comfortably survive the inevitable spike in rent once Amazon’s headquarters settles into Queens — unless you have vast familial wealth to draw on, I’m sorry but you’re wrong.

My mom was thrown into financial uncertainty (and my dad wasn’t even a deadbeat) by an early divorce and the responsibility for two small children, but at this point that choking feeling is basically just the lived experience of the average American. In a conversation with Hans Ulrich Obrist in 2003 J.G. Ballard said that “the totalitarian systems of the future will be subservient and ingratiating, the false smile of the bored waiter rather than the jackboot.” This is it, the future is here now. It’s because Geissler doesn’t fit the typical profile of an Amazon warehouse worker that her book is such a well-timed warning shot. If you think you’re immune to this — if you went to college, if you believe you’re upwardly mobile, if you imagine you will comfortably survive the inevitable spike in rent once Amazon’s headquarters settles into Queens — unless you have vast familial wealth to draw on, I’m sorry but you’re wrong. Without immediate collective action, this is coming for all of us.

*

“Too tall,” Breslin clarified, about Mayor Lindsay, “means too Manhattanish, too removed from the problems of the street corners.” He wrote “Is Lindsay Too Tall to Be Mayor?” shortly after his own failed mayoral bid with Norman Mailer, a campaign that left him “nervous and depressed.”

“I saw a sprawling, disjointed place which did not understand itself and was decaying physically and spiritually, decaying with these terrible little fires of rage flickering in the decay…On top of the city was an almost unworkable form of government and a set of casually unknowing, unfeeling, uncaring men and institutions. The absence of communications in a city which is the communications center of the world is so bad that you are almost forced to believe the condition of the city is terminal.”

If that doesn’t sound familiar, it will soon. On December 12, the New York City Council held the first of a series of hearings on the new Amazon headquarters. Protestors covered the balcony and unfurled a No HQ2 Banner. “It’s all smoke and mirrors!” a man yelled. “Don’t let them monopolize the city! Don’t let them near the subways, don’t let them near the schools — these guys are lying creeps!” He was escorted out.

Amazon has become so large that it can have the same pacifying effect as the threat of climate change, but despair isn’t helpful right now. As Hamilton Nolan and Dave Colon have already pointed out over at Splinter, Amazon’s New York headquarters represents the best chance at effectively unionizing the company and the resistance to HQ2 is broad and growing. Still, it was difficult to watch the City Council hearing without a paralyzing sense of dread. Amazon is a contractor with ICE, they have a horrific labor record, and they’re accountable to no one. That guy was right, these people are lying creeps, as are many of the people we’ve elected. There’s such a long and rich tradition of grift in this city that it’s rare to be able to definitively level blame, but here we are. De Blasio was too tall to be mayor and we didn’t see it. “Is this all a matter of life and death?” Geissler writes, at the very beginning of Seasonal Associate. “I’ll say no for the moment and come back to the question later. At that point, I’ll say: Not directly, but in a way yes. It’s a matter of how far death is allowed into our lives.”

* * *

Rebecca McCarthy is a freelance writer and a bookseller.

Editor: Dana Snitzky

0 notes

Text

The near-term extinction movement is embracing the end times

As American astrophysicist Carl Sagan keenly observed: “Extinction is the rule. Survival is the exception.” This comes as no surprise for some of the world’s greatest scientists, who already seem convinced the planet is in the midst of a new Great Die-Off, caused by human behavior. Less clear is whether this mass extinction will someday include us, but a growing number of people believe that it will. Who can blame them?

We've already dipped into a doomsday seed vault stash in the Arctic thanks to a war catalyzed in part by climate change, and images of refugees from that war rushing past militarized border police who shoot them with rubber bullets and flash bang grenades certainly don't look like a world on the upswing. And yet the chaos has only just begun: Some degree of catastrophe this century is all but assured no matter what we do now. Our oceans will continue to rise for centuries. And scientists suspect that "feedback loops," like the fast-melting permafrost in the Arctic and Siberia could send enough methane into the air to lead to catastrophic, runaway climate change.

So it's no wonder that a burgeoning number of people are subscribing to the idea that human extinction in our lifetime is all but certain. Depending on who you ask, they earnestly estimate the climate change-caused apocalypse will unfold between a few weeks to three generations from now. There's not a lot of data on how widely these beliefs are shared, but the believers are beginning to organize; loosely, at least. An "extinction candidate" is running for Senate in California. Meetings and workshops are being held around the country to discuss the End. And an active, private Facebook group, "Near Term Extinction Love," to which I belong, has hundreds of members. Call them near-term extinctionists, or the stoics of climate change, though they don't go by any official moniker.

The tone of 'Extinction Love' is similar to what one might find in an Alcoholics Anonymous meeting. One woman recently posted about feeling deep despair for life lost and fear of the future, and supporters piled on likes and comments assuring her it was OK to feel that way. Occasionally, there are posts of lighter things, like a viral photo of a swan neck-hugging a man. More frequently members post "told you so" news articles bearing bad climate news.

Pauline Schneider, the administrator of the group, says it functions as a "daily memorial or a constant wake" for the life lost to mass extinction; the people who participate are in a constant state of mourning. Schneider herself says she was a committed activist who held on to hope up until a few years ago, when she was arrested on the White House lawn as part of a protest against the Keystone XL pipeline led in part by famed environmentalist Bill McKibben. Now she scorns McKibben and others like him, whom she accuses of "lying" about our ability to mitigate climate change.

"We are not going be able to save the world," Schneider said of the group. "The events are already in motion. It's too big. We're focused on moving right now through the world and what we do with our lives, which we still have control over."

Many like Schneider say they mourn not only for the impending loss of life, but the mass death happening among the planet's beings right now, and profess a strong connection to the natural world. Some attended a workshop in New York for people who've "come to grips with near-term human extinction" and want to live out the last days of their lives as fully as possible, like doomed cancer patients who've accepted inevitable death.

Chris Johnston, who helped advise the development of the workshop, is a medical specialist with 20 years working in addiction recovery and a member of the Climate Psychology Alliance at Bristol University. When he began thinking about the psychological challenges presented by climate change, he was struck by how similar our coping mechanisms were to recovering drug addicts or terminally ill patients. Our addiction to a fossil fueled lifestyle and general refusal to recognize its harmful effects is similar to a junkie in denial, Johnston says. So is the process through which we come to terms with its mortal consequences, which proceeds from denial to anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance—the stages of grief according to the Kübler-Ross model.

"People could believe their lives were just falling to pieces," he said, "and they start thinking what's the point, what else is there to do but junk out?" The workshop for near-term human extinction was informed by some of the ideas that Johnston developed with Joanna Macy, an environmental activist and spiritual leader who has used Buddhist concepts to help people in Ukraine process grief from the Chernobyl nuclear meltdown. Despair "becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy," said Johnston, but when people recognize they've hit rock bottom, they tend to change their behavior, and can eventually find some peace in their remaining days.

"It doesn't matter whether the industrial economy collapses or not, we're screwed in the short term either way."

This workshop eventually evolved into a support group that meets a few times a month. Jevon Nicholson, a Brooklynite model and bar doorman in his 40s, has attended about five of the group meetings. Like Schneider, Nicholson's politics have long been progressive, and for years he worked to improve the world. He voted for Obama in 2008 and supported Occupy Wall Street, but the seeds of despair had been laid years earlier, after he lost his job at an education nonprofit and found more time to read about how the nexus of government and corporate interests were driving climate change. These days, Nicholson said, he's chosen to live a simpler life and "disconnect from the hyper-consumption" of the fossil fuel economy.

"I spend most of my time in the acceptance stage, trying to live lovingly and compassionately," Nicholson told me, referring to the Kübler-Ross scale. He regards people who propose market-based solutions to climate change as hope-profiteers, and said that through the extinction support group, he's found "other people out there comfortable letting go of hope." He estimates humanity will be gone within 100 years.

Nicholson, like many of the climate stoics, was introduced to the idea of near-term extinction through the blog postings of Guy McPherson, a professor emeritus of natural resources and ecology at the University of Arizona and, more recently, a certified grief counselor. "I was filled with hope until 4 years ago, when the evidence overwhelmed me," McPherson told me over the phone in July. "It doesn't matter whether the industrial economy collapses or not, we're screwed in the short term either way."

McPherson's stark hopelessness has earned him ire from some fellow scientists, who accuse him of cherry picking data to fit his terminal prognosis. And it's hard not to wonder whether McPherson's ego compels him to find pupils for his message. Back in 2009, when he threw in the towel and decamped to a homestead in rural New Mexico, he had expected others to follow him. When nobody did, he became confused and angry, but says he eventually reached a point where he accepted "how difficult it is to change one person's mind, much less other people's."

These days, McPherson says he works to help people learn how to "spend our precious few breaths on this planet doing work we love, pursuing love, and excellence in our lives," which he thinks are lessons we should take to heart whether or not he's wrong about the coming apocalypse—which he predicts could come as early as October.

Two months after we first spoke, McPherson invited me to a gathering at Pauline Schneider's home in Westchester, New York, about 35 miles north of the city.

When I arrived, McPherson and three others were sitting solemnly in the lush backyard under the last licks of summer heat. As more people arrived—about a dozen showed up in total, nearly all in their middle years—the mood became chattier, but remained grim. I can't recall hearing laughter more than once the whole evening. After warming up with a chat about car accidents, we got right down to discussing the end times.

I mentioned to the group that I'd spoken to ocean fauna experts who were hopeful that humanity could at least mitigate some devastation in the oceans. Thom Juzwik, a massage therapist in his 50's, shot down the possibility by pointing out the proliferation of oxygen-sucking algae blooms in the oceans, which one study suggests played a role in the Earth's previous five great extinctions. Others agreed. As the conversation moved along, they all scoffed at Hilary Clinton's support from the oil and gas industry, but I was in the minority in feeling unsure the world would end before 2030.

This pessimism is beginning to percolate into the mainstream with the release of Roy Scranton's anticipated new book Learning to Die in the Anthropocene. In it, Scranton advocates for a new philosophical framework that could become a metaphysical wrench-in-the-machine for the global economy, interrupting flows of capital and and replacing knee-jerk reactionism with slow, mediated reflection on our own mortality.

"Philosophical humanism in its most radical practice is the disciplined interruption of somatic and social flows, [and] the detachment of consciousness from impulse," he writes. At a recent talk Scranton gave at the book's launch in Brooklyn, he suggested the science was just too bleak for social movements to change our future, and all there was left to do is cultivate compassion and patience as we wait to die together.

Scranton's stoicism is just the kind of detachment from our fiery collective fate that near-term extinction adherents value. Yet while they may uniformly believe the End is nigh, it's clear that some still hold onto the possibility that things could change for the better.

Originally published in Motherboard by Aaron Miguel Cantú

0 notes