#its kind of absurd that people make generalized claims about a whole genre the way people do when it comes to country music

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

I think your take on Doublemeat Palace is interesting because to me it's emblematic of all the things that make Season 6 (particularly the back half after "Tabula Rasa") not work for me. It's relentlessly grim and unpleasant and I can feel the writers twisting the plot to make sure every character is as miserable as possible. I'm not opposed to seeing protagonists in a low point or even outright failing. Season 3 of Game of Thrones is some of my favorite TV ever. (1/2)

(2/2) But at a certain point the grim and gritty, if it's not well written, and broken up with some moments of lightness (like Buffy was previously known for) the audience gets numb. It also doesn't help that no one has any agency. (Magicrack, the not!wedding, Dawn doing zip) Again, I'm not opposed to dark plotlines. I'm opposed to incompetent writing.I don't think you can call an episode or an arc "objectively" good if it doesn't work for the majority of the audience it's been written for.

you know, i’m going to disagree about the “grim and gritty” thing. doublemeat palace actually stands out to me as being really funny. and for having a lowkey positive ending. true, the episode is about the soul-sucking prospect of having to do the same dreary work every day. it’s about how much it sometimes sucks to work, which is why you have willow dealing with the fact that recovery is a difficult thing that you have to decide to commit to every day, xander and anya facing the fact that marriage is also a lifelong daily commitment, and buffy taking an unpleasant and mechanical job in order to put food on the table (and the episode plays up that the managers have been doing it for five or ten years). but like, names like “manny the manager”? the weirdo robotic people? the exaggerated camera angles? the swirling cow and chicken? buffy’s constant attempts at jokes? “hot delicious human flesh”? a little old lady with penis monster on her head? this stuff is totally absurdist. i think of doublemeat palace as almost the opposite of episodes like once more with feeling and tabula rasa, where things superficially seem fun but are actually quite dark. doublemeat palace seems superficially unpleasant but actually has a wicked sense of humor. and i say that the ending is positive because it involves both willow and buffy committing to doing work. they’re faced with the opportunity to “cheat” at life like the trio, who steal money instead of having jobs, but ultimately decide to do the right thing. willow doesn’t accept amy’s magic and buffy doesn’t blackmail the company.

that goes for a lot of season six, in my opinion. even late season six. people say there was less humor, and i think that’s true to an extent, but honestly i think it’s more that the tone of the humor changed. it got more sardonic and absurd, but was definitely still there. eg people think of seeing red as the episode where the two Very Bad Things happened, but outside of those scenes a lot of the episode is like, fascinatingly (to me) slapstick (the whole jetpack bonanza? “say goodnight bitch” “goodnight, bitch”). and has that really lovely conversation between buffy and xander at the end. in general, i think a lot more season six episodes have positive endings than it gets a reputation for. i already mentioned the ending of doublemeat palace. but the end of gone has buffy saying she doesn’t want to die, the end of older and far away has buffy deciding to stay home with dawn, the end of as you were has buffy deciding to break up with spike, and the end of grave has buffy, willow, and spike all making important changes for the better. as in, season six can be very dark, yes. but i would not call it a hopeless or cynical kind of dark. it’s about the characters clawing their way out of that dark place. not just a statement that “adulthood sucks.” you can argue that the season didn’t pull off its attempts at lightness, but i very much think they’re there.

at any rate, i agree to an extent that if a work of art isn’t working on most people, that’s probably a sign it’s doing something wrong. but i’d offer the counterpoint that you might also say that if a work of art really works on some people, even if not everyone, it’s probably doing something right. as far as the season as a whole goes, i’d actually take issue, on a basic factual level, with the claim that it didn’t work on the majority of people. not to validate IMDB’s ratings for buffy’s episodes, but it does have an n=~2000 sample size and if you average out the ratings by season, season six doesn’t rank starkly lower than any other season. it’s on the less popular side, but it still hovers around an 8.0 average like most of the other seasons. moreover if you go by the big r/buffy polls (n=~120-310), season six ranks in the top three favorite seasons every year they did one (2011: 3 > 6 > 2, 2012: 6 = 3 > 5, 2013: 6 > 3 > 5, 2014: 3 > 6 > 5, 2017: 5 > 3 > 6). you can see the data for yourself if you scroll down to where it says “surveys”. perfectly possible that there’s data that paints a totally different picture. this is just what i had on hand. that ranking also doesn’t mean the majority of people liked the season, but it does act as evidence that there are a lot of people whom it really worked on. basically, i wouldn’t say that season six is disliked so much as it’s divisive. people seem to either love it or hate it. with a smaller percentage that likes it, but for whom it isn’t a favorite. or who appreciate what it was trying to do but don’t think that it succeeded.

as far as doublemeat palace goes i notice a similar phenomenon. people either really hate it or they really relate to it. either they think the style is bizarre and annoying or they think it’s delightfully surreal. so it really seems like it’s up to the individual whether they want to lend more credence to one audience reaction or another in order to assess quality.

which is why i tend to use my own rubric. when i ask myself whether something is good or bad, i pay a lot of attention to (1) is the work trying to do or say something specific? (2) how unusual or challenging or astute is the thing the work is saying? (3) how coherently is it doing that, and on how many different levels? (4) on a formal level—dialogue, cinematography, costuming, acting, pacing—how fluently was it executed, and how well did the formal choices contribute to the ideas in (1)?

for the record, i don’t think that doublemeat palace is the best episode ever. i just think it’s solid, and fits nicely into what i think the season as a whole was doing. but the reason i say that it’s “objectively” solid according to my personal rubric—which granted, you’re more than welcome to not share—is that (1) it has a pretty clear idea that it’s exploring. the drudgery of work stuff that i mentioned in the first paragraph. moreover i think that idea is really relevant to the season-long topic of “what makes it feel like adulthood sucks”. buffy having to take a menial food job fits into the season’s food motif that i talked about once, which in turn fits character-wise with buffy’s ambivalence about being alive. a somewhat grotesque/humiliating job fits with the mood of material existence being unpleasant. (also, xander impulsively chowing down on food speaks to him probably not being ready for commitment) (2) i think this whole subject was just hella daring for the show to do. having been a poor and suicidally depressed 22 year old in a fucked up sexual relationship while working a menial job, season six and episodes like doublemeat palace just ring true to me as something for a show about growing up to depict. sometimes real life really is a grind, and sometimes it really does feel profane, absurd, surreal, etc. (3) i really like the way that buffy, willow, and xander and anya’s stories all fit the theme of episode but in different ways. i wouldn’t say the episode is a super nuanced take on drudgery, but it does have layers thanks to the three different storylines, and it comes off as clearly conscious and oriented around its theme. there are other parallels like amy, spike, and halfrek each being influences, too. (4) there’s some cool formal execution. not all of it. willow’s story, like a lot of her mid-season-six arc, is kind of tediously on-the-nose. but i enjoy pretty much every second of buffy’s part of the episode, because the direction is so in control of it. and i like the absurdist and genre-conscious playfulness. the soylent green riff, etc.

i also disagree on your assessment of agency in the season but this post is long enough as it is. regardless, i certainly don’t begrudge you your opinion. it’s an often clumsy season. it also sounds like we enjoy things in different ways--i genuinely don’t care too much about writers contorting things in the interest of theme. i’m mainly trying to push against the implications (1) that the season was obviously just trying to be dark and grim, and just for it’s own sake or something. instead of for deliberate and interconnected artistic reasons that one could analyze and talk about, and (2) that there is some monolithic opinion on and response to it.

#s6#sigh i tried to add a tag and the read more got messed up#man tumblr code is fucked#fyi people are welcome to respond to this but i probably don't have more bandwidth to respond back#also if it wasn't clear from like 70% of this blog i adore season six and it means a lot to me#so at a certain point 'why season six is bad' discourse just kind of makes me sad#even if i respect why people think that and agree with various criticisms

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

A glossary of fandom terms that have either been taken from literary criticism (incorrectly) or that I use that are either no longer in use or have... different definitions now.

If anyone has any terms they’d like to see added or words you come across that have confused you, please drop me a line. I’d be happy to add to this whenever. It’ll all be under a readmore so that I can edit it when needed. ^^

Discourse--Literally a discussion, like, the act of discussing. That’s it. More specifically, people will say, “the novel here participates in one of the many discourses on gender” or something like that. Essentially linking one occurrence to a wider conversation. Literature and Media do not exist in a vacuum, but neither can one work make a trend, but I’ll get to that. Just call it wank or meta. Use the words we have, don’t take words from academia, especially when you don’t understand their context.

Romance--One of many genres of fiction. This is a story that centers around a romantic relationship between two or more characters. I could tell you about how all genres are crutches and constructs we assign to make ourselves feel better, but that might be moving too fast. For now, what’s important is what a romance isn’t. A romance is NOT some kind of idealist model that must serve as a positive example for the Youth. That would be Utopian Romance fiction (which is boring because stories need conflict, but that’s my own opinion on the matter). A romance only needs the major plot conflicts to hinge around the romantic (as in not platonic, this could be love or lust or some combination thereof) relationships between its characters. Pride and Prejudice is a romance. Captive Prince is a romance. The Foxhole Court, while containing a romantic subplot, is not a romance. Harry Potter is not a romance. A story can have romance without being a romance. Compare romantic comedies with action movies, as an example. But, don’t think that a romance can’t be tense or unhealthy or whatever. Fifty Shades is also a romance, remember. If you wrote out the Joker and Harley Quinn’s story, only focusing on them, their story would be a romance. It’s more complicated than that, obviously, and there’s nuance, but I think you get the picture. Regardless of your moral views on the love depicted, a romance is nothing more or less than a story about the development of a romantic relationship.

Fetishization--I hate seeing this word thrown around. This literally means that something has been made into a fetish object on a cultural level. You can have the fetishization of purity in American culture, for example. And you can have the fetishization of homosexual relationships in pornography intended for heterosexual audiences. However. A single work of fiction is not fetishizing anything. It may contribute to an overall trend, but this is not a word to use for single entities. This is a cultural trend word. Sure, it can be used for subcultures, but whenever I see this word used, it’s used to mean that some work of fiction or other is bad for displaying a queer sexual relationship in any kind of (perceived) perverse way. Please stop using this word incorrectly. As a kind of burgeoning critical theorist (i.e. English grad student), it is incredibly frustrating. You’re using words you don’t understand in ways that undermine the hard work being done by people in my field. Unless you’re going to read Marx and Lukacs and learn what the word “reification” means, I think you should use another word. In most cases, what is meant is that some group people don’t like are showing an interest in something perceived as not belonging to them, whether that’s true or not. I think if we unpack that a little, we can all find better ways to phrase things. Fetishization is an accusation thrown around, not the analysis it’s meant to be. And, frankly, it needs to stop.

Normalization--This is thrown around so often I hardly know where to begin. This is not a word that can be used for a single object, again. This is a word meant for trends. For example, we could talk about the fact that male violence in our culture is normalized and so no longer taken as seriously as it should be. A fictional work depicting something you don’t like in a way you perceive as positive and uncritical does not mean that it’s normalizing it. A single crime procedural does not normalize crime. You could say that the trend of always showing cops to be in the right, no matter the extreme actions they take, normalizes the liberties they take in the real world, making it difficult to speak out against police brutality and other such abuses. But again, that’s the genre as a whole--procedural cop dramas could all contribute, but one of them is not going to be normalizing on its own. That isn’t how that works. Just say that you find whatever it is unpleasant to read because of X or Y trope. Or talk about how the TROPE is normalizing something. That’s totally legitimate. The trope of X normalizes Y behavior in Z culture/situation/etc. and this is harmful because W.

Romanticization--This does not mean that something bad is shown in a romantic light. This is another big trend word. Cultural myths about heterosexual marriage and related gender roles contribute to the romanticization of domestic abuse. A single work of fiction depicting an abusive relationship in any kind of perceive positive light is not romanticizing abuse. Cultural narratives about women needing to be convinced can romanticize the act of rape, especially from the male perspective. One work of fiction cannot do this. It has to be on at least a genre level, if not cultural or societal. Again, subcultural too, but you have to make the argument apply outward. The BL/Yaoi trope of having a Seme character force an openly reluctant Uke character into sex romanticizes sexual assault. One BL using the trope can contribute to it, but it isn’t romanticizing anything on its own. It’s not powerful enough to be capable of that.

Wank--The word once used to describe what is now called “discourse.” It’s usually a circle jerk of complaints about some fandom or another or the people in it. Every example of so called discourse I have ever seen was actually just wank wearing a new hat. Don’t put on airs or borrow credibility. Call a spade a spade.

Meta--Analysis on a series or character. Some of these are better reasoned than others, but the only way to truly rate them is in how well they use their evidence (and how much evidence they have) to support whatever claim they make. These are often essays, but can be a couple paragraphs, sometimes with pictures as evidence along with quotes from the source. Some “discourse” falls into this, but only very rarely. Most people call meta either meta or analysis instead.

BNF--Big Name Fan. This is THE person in your fandom, generally an artist, occasionally a fic writer or other content creator. You’ll know them when you see them. This is the person everyone follows. Their headcanons are so widely accepted that they almost always become fanon (whether you like it or not). Some of these people are super nice and use their powers for good. Others can become divas, mad with the power the fandom has given them. Regardless, there is almost always drama brewing around them (whether they like it or not, unfortunately). I recently saw some commenting on people actually asking other fans for permission to hold certain headcanons. Someone with that power is a BNF. That is a TRADEMARK of a BNF. Their fandom credibility and respect is so high that people see them as some kind of authority figure. Be wary of people who go along with this. They’re not to be trifled with, and frankly, it’s safer not to engage.

TPTB--The Powers That Be, otherwise known as the writers/producers/creators of any given series. These are the people that create Canon and produce Word of God.

Canon--Anything that explicitly happened in the confines of a series. Basically, the events of any given series in whatever form the standard is. I.E. episodes of a TV show, books in a book series, etc.

Fringe Canon--Works that are connected to the series in question, but not part of the standard form. Often includes movies, novelizations, guide books, etc. Can be considered canon, but isn’t something every fan will see/have access to, so can’t really be considered The Canon. Can also includes things that are implicit in the text, so something that can be argued in meta but that not everyone will agree on.

Word of God--Something said by TPTB that remains outside of canon. I.E. interviews, panels, and other things said at conventions or for PR. Common mantra, “PR is not showrunning” meaning that Word of God often has little to do with what happens within the series. Example: Some sub-textual evidence of Dumbledore being gay does not make his being gay canon (it makes it fringe canon, imo). Rowling saying that he was gay in an interview is here considered Word of God. You can take it or leave it, because no one in the series says the words “Dumbledore was gay” or any other variation that would make it explicit canon.

Headcanon--Something that you decide about a character. This isn’t canon and often has no strong basis in canon. It can include sexuality, gender, religion, favorite color, anything not covered by canon. You can also have headcanons that contradict canon.

Fanon--Headcanons that have become Too Powerful. These are things, good or bad, that have been accepted by a probably absurd number of people. Some of these can be great, especially when the series has some seriously bad writing, but if you find yourself disagreeing, this can be the worst thing you ever have to deal with. Especially when people who subscribe to it insist on its being canon...

Ship--Any feasible romantic relationship, canon or non-canon. There are of course platonic variants, but those are usually specified (broship, brotp, etc.). Most often two people, but more recently polyshipping has come into vogue. To Ship (v.)--For me, this does not apply to canon ships no matter if I like them or not. Shipping is transformative. To me, more than anything, shipping (as a verb) means you consume or create transformative media centered around that relationship (most often non-canon or not explicit canon, but could include canon, it just needs to be an active not passive interest in the relationship).

Canon Ship--The series endgame, usually (but not always!) straight. This is an explicit couple. They are in a relationship. They kiss (or something) on screen. You can still take it or leave it, but that doesn’t stop it from being canon.

Rare Pair--This is a ship that has some basis in canon, but is extremely unpopular. Some people include anything with less than a certain number of fic on Ao3, but it varies by fandom. I’ve been into rare pairs with less than 10 fic written for them, so anything around 500 still seems like quite a bit in comparison. Your Mileage May Vary (YMMV), but you’ll know it when you see it.

Crack Ship--These people have probably never spoken. There is no reason for them to be in a relationship other than the fan’s preference (often aesthetic or story-related). A crack ship is often random and completely baseless. A crack ship is not simply a ship that won’t be canon. Most ships will never be canon. This goes beyond that into the ridiculous. As a recent example, Keith x Zarkon would be a crack ship, while Keith x Hunk is perfectly reasonable (if rare).

Multi-shipping--Shipping characters together without a strong preference for one combination over another. For example, shipping your fave with every possible romantic partner, not just one (or more in a polyship). This includes Everyone x Character type things, not just “I could ship them with literally anyone.” Both count.

OTP--One True Pairing. The ship you love above all others, canon or not. For me, I have exactly one of these per fandom, but I know other people use it differently now. This used to mean that you ship the thing exclusively. You might like art for other ships with the characters in this OTP, but you’re not that into it. This used to be THE ship. The characters in this OTP were not shipped with others, and other relationships were used for jealousy or plot reasons, not usually because you enjoy the other ships. This is the ship you go to war about.

OT#--Same as above, but there are more than two people involved. So, the one polyship you hold above all other ships (poly or not).

BrOTP--Platonic version of the above. These are the ride or die friendships of the series. You don’t see them as in love, but they absolutely love each other. There’s devotion and loyalty and affection--or you just think their friendship is the best/greatest/funniest and you don’t see them ever ending up together romantically. You want these characters to be BFFs, not lovers.

#fandom meta#my meta#Glossary of Fandom Terms#Lemme know if I missed anything big lol#I've been sitting on this for over a year XD

70 notes

·

View notes

Photo

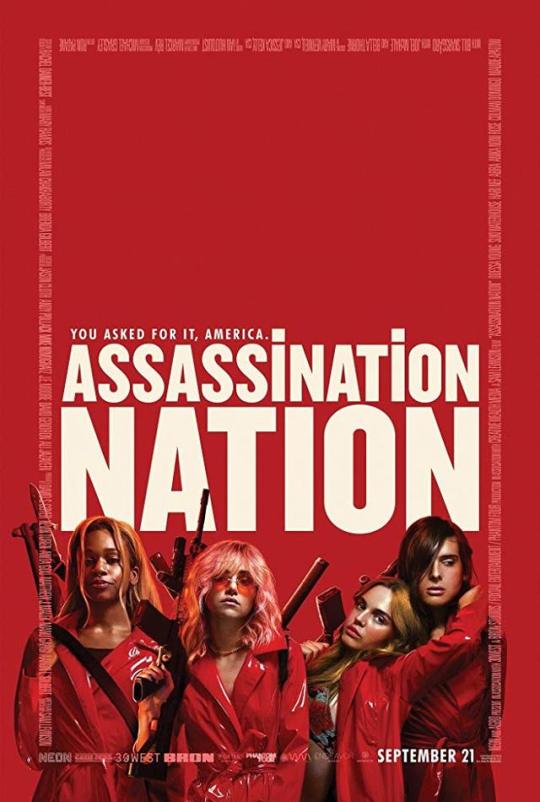

“Assassination Nation” Movie Review

It’s difficult to pin down one specific way to describe Assassination Nation. The sophomore effort from writer/director Sam Levinson (son of legend Barry Levinson) is so chock full of energy and pure, unadulterated, gen z-style righteous fury that any focus on one particular genre, even insofar as the film’s brief exploration of those genres, really doesn’t play much into the overall narrative or even thematics of the film’s central premise (which, believe me, is absolutely one of the most visceral experiences you’ll have this year) except to show the audience that “hey, bet you thought we wouldn’t go there/include that, did you?” In fact, the most apt description of any genre this film might be pinned to is more of a feminist pulp horror/satire, a genre which, between this and Coralie Fargeat’s Revenge, is getting a serious boost in 2018, and justifiably so. This means that what we’re left with as an audience is more an experience and a message than an actual story, but one that’s told with such creativity and commitment to the more absurd parts of what story it has that it starts to feel just real enough to be legit.

The big central conceit of the plot is (at least at first) more a play on the idea of character assassination than a literal one (though that does become part of it later on) as an unknown computer hacker begins targeting a few select people and dumping all of their person data onto the internet for the public to view, and because this is conservative small-town America (at least as far as the older characters in the film are concerned), this information happens to contain a lot of explicit and often overtly sexual material not only inconsistent with but often in direct contrast to the views these characters claim to hold. The problem is, they’re not the only targets, and once the hacker starts targeting the younger inhabitants of the town (most of them teenage girls from a local high school), including our four main characters (played by Odessa Young, Suki Waterhouse, Hari Nef, and musician Abra), eventually people start looking for someone to blame due to the high paranoia and “concern” for public safety. Somehow (in a way I won’t spoil here), the target gets turned on these four teenage girls, and because this is a town called Salem (yes, that’s literally the name of the town), this is going to go down almost exactly how you might think it does.

If two paragraphs ago is where I laid out what kind of film this was, this is the one where I lay out what kind of impact it has and what makes it impactful. I won’t concede it being perfect or even particularly well-made in terms of editing, production design, screenwriting, or even character development, but it is damn near impossible to deny the impact that the film has on the viewer upon the introduction of the end credits. This is not your typical fun grindhouse teenage slasher type of horror satire. The film’s opening 30 seconds literally include an entire barn-full of trigger warnings for blood, violence, homophobia, transphobia, fragile male egos, more violence, blood, and gore, nationalism, mob revenge, and explicit reference to sexual assault and coercion.

What makes all of these so potent though, is that this is the generation raised on the “fun,” stylized kind of violence, taking on that kind of violence as their own, but presenting it realistically, hence the trigger warnings right at the beginning. None of it is pretty, none of it is fun, and very little of it is actually positive right up until the very end. The actual murders that occur are gruesome and heinous, the bloodshed is harsh and uncompromising, and the notion of a town called Salem trying to find seemingly any excuse to turn its literal rifle scopes on teenage girls as the central problem to something that is not only in no way their fault couldn’t be less subtle or poignant if the main character’s name had been Abigail or a Proctor family had been present. In order to even sell most of this, the burden is placed on the performances by our four central characters, and these actresses do an admirable and impressive job not only selling it, but getting you to buy into the deluxe package (particularly in the cases of Hari Nef and Abra, who themselves are completely three-dimensional characters not just subjected to being “the trans and black ones.”)

In fact the greatest positive takeaway from the whole endeavor is the sheer energy of its underlying thematic weight of a feminist power fantasy. The pulp horror/satire not only serves as a jumping off point for the fury of its pacing and visceral aggression of its explicitness, but also as a springboard for its narrative literally playing itself out not only as feminist pulp horror narrative, but as explicit message to the Trump administration and those who continue to support the ideals held up by it in this day and age that they know how these people tend to treat/judge the opinions, dreams, hopes, wishes, and even bodies of teenage girls, and not only are they justifiably and righteously angry about it, they’re not taking this lying down, no way in hell. That’s a level of boldness you can only get in these in-your-face, “maybe cult hits someday” types of films that come out between the summer movie season and the winter awards rush, and it really has to be seen to be believed. It’s more of an experience than it is a film proper, but filmmaking has never been, nor should it ever be, one kind of thing, and making films grounded more in an audience experience than a story in their own right, is sometimes necessary to remind us of that fact. I was damn glad I actually got to catch this one before it left my local theater.

There are a few negatives to the film; I didn’t forget about those, although it’s difficult to really care as much about them afterwards. The editing is a bit jarring sometimes, some of the other supporting characters are pretty shallow even for purposefully not having much to them in the first place, the script (while certainly hyper-aware of shallow teenage conversation nuances) isn’t exactly the best, most of the characters don’t really change and what change there is barely registers, and the whole mystery of who the actual hacker is eventually gets lost once the film reveals that it’s really more of an introductory piece to what the film is actually trying to say, so the story point just kind of drops until a very sudden turn at the very end that doesn’t exactly feel earned, but again, this is more of an experience than a film proper anyway, so who’s really counting.

This is the kind of film that will definitely define the lines of a generational divide in terms of how much one appreciates and understands what it’s attempting to do/trying to say, and also in terms of personal enjoyment (basically it’s one that your parents might think is terrible, but certain members of your extended family might think is still pretty interesting even if they don’t fully enjoy it themselves). It’s certainly not for everyone, and definitely not for the faint of heart (if the abundance of trigger warnings in the teaser trailer and opening 30 seconds didn’t give it away), but it’s definitely an experience worth having if you can handle what it throws at you in terms of sheer, visceral, feminist rage. Perhaps the greatest “well that was unexpected” experiment in filmmaking in 2018, it may not be the best of the year by a two-point shot, but it should definitely be counted among the must-sees.

I’m giving “Assassination Nation” a 7.9/10

#Assassination Nation#Movie Review#The Friendly Film Fan#Odessa Young#Suki Waterhouse#Hari Nef#Abra#Sam Levinson#Movie#Film#Review#2018#New#Horror#Satire#Feminist#Pulp Horror

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Quick Look at Banana Fish

After having some of my acquaintances recommending this anime, and since seeing that it has gained a in general positive response on the Internet I felt compelled to check this out. I watched the whole show in two days and boy,what a journey it was.

As some of you might know, I’m quite new to anime (just a little more than one year has gone by since the first time I willingly and consciously watched my first anime), but has really gone through a lot in this time. Some of the classics like Naruto and Death Note, some fantasy, magic, shoujo, shounen and of course my very beloved genre sports. In all of these categories there are good animes, awesome even, and some trash. I will not speak about what is what, but you all should know. Banana Fish is not trash. Banana Fish is unlike anything I have watched before, just because it is so little like trash.

As a short summary, Banana Fish is about the American boy Ash Lynx who is 17 years old and the leader of a gang on the streets of Manhattan. He is also “a pet” and “a favourite” of the local mafia boss going by the name of Papa Dino, and has becasue of this gained quite a few enemies wishing for Papa Dino’s favor. By chance Ash and the Japanese boy Eiji, a photography assistant and 19 years old, meet.

This anime has proved to be realistic in way that, measured by anime standards, is not at all absurd or in any way bad. The characters are portrayed beautifully and the full complex mind of how humans act, why they act, and the consequences of one’s actions are told in such a natural and ingenious way that you as a viewer can’t do anything but end each episode wanting more. This is an anime produced to make you think. To view the story, the characters and their backgrounds and then let yourself ponder on whether you would have made the same decisions as they did. It is supposed to make you really understand the full complexity of one’s decisions, and overall make you realise that sometimes the best action to do is the one that’s not the worst. This anime is brutal, cruel, but most and foremost real in a way I personally feel many of today’s animes aren’t.

Each episode are about 23 minutes long which is pretty much standard. However, you might marvel at how much action the studio manages to cram into those 23 minutes, and not in any way do I view this as something negative. Rather, I’m impressed with the production. The animation is lovely and the fighting scenes energetic and beautifully choreographed. The plot steadily continues to move forward all the time, and a lot that is crucial to the story - whether it is character development or the actual story-line - always happens. All in all, there isn’t much for me to criticize plot-wise, so let’s move on to the characters, shall we?

Main characters are as stated before Ash Lynx and Okumura Eiji. One thing I want to say right now is that the way the relationships evolve between them is so smooth and fun to watch that you as a viewer can’t do anything but really sympathize with their struggles, their dilemmas and problems. It is quite smart actually, to make them like this. Ultimately, one of the great focuses of this show would be relationships. Ash’s relationship to Eiji to some extent, but perhaps more importantly to himself. He is young, and as you might have guessed to those who haven't watched the show, he has had an incredibly rough childhood. I won’t spoil anything more than that, but to say that nobody can blame him for having a hard time building relationships and trust with other people. However, there are some exceptions. Eiji of course, but then I haven’t even mentioned Ash’s best friend Shorter Wong, the Chinese youngster that’s also a leader of one of the local street gangs. I won’t delve deeper into Shorter’s character, but you should at least know that he is a person that Ash holds deep trust in, one of the few people in his life that he would trust with his life.

This anime is dark, action-packed and a great story-line. It has humor too, and some very sweet and memorable moments with fitting animation. To those of you that wouldn’t watch it because you claim it’s gay miss the whole point anyway. This is about having the courage and the trust to be able to let someone into your life again and not to lose hope. It is about managing to pull through hard times because sometimes you need to do something, anything, to keep your mind from straying to close to the edge of insanity, It is about love in its purest and most beautiful form, when love is allowed to be just love without having anyone judging you, and if they do to be able to live on because you know that you have that one person that will stay forever at your side, even if forever is just for one single moment.

If you cannot handle a close relationship between two male main characters I suggest you do not watch Banana Fish. But to those who manage to realise that the focus of the anime isn’t having two guys having a romantic relationship and jumping into bed with each other, but rather the development of how that kind of love, trust and loyalty is built; this is an anime for you.

#Banana fish#Anime#Manga#Ash Lynx#Okumura eiji#review#opinion#shoujo#crime#dark#episode#relationship#yaoi#series#tv#story#humor#love#development#people#japan#usa#new york#manhattan#gangs#papa dino#shorter wong#death#childhood#drama

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mortal Kombat and Bloodsport: The Strange Connection That Changed Gaming

https://ift.tt/3vd5lXB

As we eagerly anticipate the release of the latest Mortal Kombat movie, many find themselves looking back on Mortal Kombat’s 1995 big-screen debut. While that film has its charms and its fans (myself included), the movie has rightfully been criticized over the years for lacking many of the best qualities of the game as well as many of the best elements of the martial arts movies that clearly inspired it.

Of course, the relationship between Mortal Kombat and martial arts films has always been close. Not only did the game utilize a then-revolutionary form of motion capturing that gave it a standout cinematic look, but many aspects of the title were practically taken directly from some of the best and biggest martial arts movies of that era.

As the years go on, though, it becomes more and more clear that no martial arts movie impacted the development of Mortal Kombat more than Bloodsport. Maybe you’ve heard that MK was inspired by that beloved movie, but a deeper look at the relationship between Bloodsport and Mortal Kombat reveals the many ways both big and small that the two would go on to change gaming forever.

Bloodsport: The Crown Jewel of Absurd ‘80s Martial Arts Movies

While the 1970s is rightfully remembered as the decade when America became obsessed with martial arts (due in no small part to the influence of Bruce Lee’s legendary films), it really wasn’t until the 1980s that you saw major and minor studios compete to see who could produce the biggest martial arts blockbuster.

Of course, many of the martial arts movies of that decade were different from what came before. They had bigger budgets, were usually more violent, and, maybe most importantly, they generally catered more to Western audiences. Yes, the ‘80s is the decade that Jackie Chan and other Asian martial artists did some of their best work, but as more and more Western studios got in on the action, we saw the rise of a new kind of martial arts movie that more closely resembled the over-the-top violent action films popularized by Arnold Schwarzenegger.

That also meant the rise of a new kind of martial arts star who was typically either from America or played American characters in what we can now see was an effort to capitalize on the idea of American exceptionalism that was especially popular during the Reagan era. If you’re looking for some notable examples of that trend, I’d suggest checking out Best of the Best, Above the Law, and, naturally, American Ninja.

In many ways, though, 1988’s Bloodsport is the pinnacle of that time in martial arts movies.

Bloodsport co-writer Sheldon Lettich says he came up with the idea for the film while talking to a martial artist named Frank Dux. Among other things, Dux claimed to be a former undercover CIA operative who once participated in an underground martial arts tournament known as “Kumite” in order to take down the criminal organization that ran it. Dux also claimed he was the first American to ever win the tournament.

To be frank, Dux was full of shit and, despite the fact that Bloodsport bills itself as a story inspired by true events, Lettich knew it. Still, the idea of an American martial artist winning a global underground tournament featuring the world’s greatest fighters was too good to pass up.

Indeed, the absurdity of that premise is a big part of what makes the whole thing work. While Dux’s story was almost certainly “inspired” by the plot of Enter the Dragon, Bloodsport wisely veers away from that classic in ways that take advantage of the best (or at least most loveable) elements of that era.

The smoke-filled back room that hosts many of Bloodsport‘s key fights is far removed from the tropical paradise of Enter the Dragon, but it captures that vibe of an ‘80s pro wrestling arena where the stale air is punctured by the screams of a bloodthirsty crowd. Whereas many early martial arts movies were designed to showcase the speed of their leads, the deliberate, slower strikes in Bloodsport perfectly compliment the absurd sound effects they resulted in which suggested that every punch was breaking bones. It’s a ridiculous idea tempered by a surprising amount of raw violence. In a nutshell, it’s a snapshot of what made so many great ‘80s action movies work.

What really made Bloodsport special, though, was the work of Jean-Claude Van Damme. It’s hard to call the young Van Damme’s performance “good” in any traditional sense of the word, but considering that he was cast in the role to be a good looking young martial artist with charisma to burn, it’s also hard to say he didn’t do exactly what he was asked to and then some.

More important than JCVD’s movie-star looks were his martial arts abilities. I don’t know how Van Damme’s real-life martial arts experience stacked up against the best competitors of that era, but what I can tell you is that Van Damme came across as the real deal at a time when many studios were still casting the biggest bodies and teaching them to be action stars later. By comparison, Van Damme was lean, flexible, and not only capable of selling us on the idea that he could kick ass but genuinely also capable of kicking many asses.

Bloodsport was a box office success that would certainly go on to become a genre cult classic, but its most lasting impact has to be the way it introduced so many of us to Jean-Claude Van Damme. Indeed, the attention the movie brought to Van Damme was about to also make waves in the video game industry.

Midway to Hollywood: “Bring Me Jean-Claude Van Damme!”

Much like the tales of Frank Dux, the stories of the early days of Mortal Kombat’s development are sometimes twisted by legend. However, nearly all versions of the story come back to Jean-Claude Van Damme in one way or another.

Mortal Kombat‘s origins can be traced back to co-creators John Tobias and Ed Boon’s desire to make a fighting game featuring ninjas that would also allow them to utilize the kind of large character designs they emphasized in previous works.

Unfortunately, the initial pitch for that project was rejected by Midway for the simple reason that there seemed to be some doubt regarding the commercial viability of an arcade fighting game. Remember that this was all done before Street Fighter 2 really took over arcades, cemented itself as a game-changer, and inspired studios everywhere to start go all-in on the genre.

Instead, Midway decided to pursue an action game starring Jean-Claude Van Damme. The details of this part of the story sometimes get fuzzy, but it seems they specifically hoped to develop a game based on Van Damme’s Universal Soldier film. At the very least, the idea of adapting the mega star’s latest movie into a game must have seemed like a much more surefire hit than an unlicensed fighting title.

Recognizing an opportunity, Tobias and the rest of the four-person team that would go on to make Mortal Kombat decided to see if they could get Van Damme interested in the idea of starring in their martial arts game. Boon recalls that they even went so far as to send Van Damme a concept demo for that project by capturing a still of the actor from Bloodsport, cropping out the background, and replacing it with their own assets. There have even been reports that they were prepared to name their game Van Damme as the ultimate showcase of the star.

The idea fell through, and there seem to be some contradictory reports regarding exactly what happened. Boon once said that he’d heard Van Damme already had a deal in place with Sega that would conflict with their offer, but, as Boon notes, Sega clearly never released that game. If such a deal ever was in place, it seems nothing ever came from it. It’s also been said that Van Damme was too busy to model for the game’s digitized animations or was otherwise simply uninterested.

The entire Van Damme/Midway deal ending up falling apart, but there was a silver lining. Now given the time to properly recognize that the fighting genre was blowing up in arcades, Midway told Tobias, Boon, and the rest of the team to go ahead and work on their martial arts game, Van Damme be damned.

While Van Damme was technically out of the picture, the team at Midway were hardly ready to give up entirely on their idea of a fighting game inspired by Bloodsport

Read more

Movies

Mortal Kombat: An Ode to Johnny Cage and His $500 Sunglasses

By David Crow

Games

Mortal Kombat Timeline: Story Explained

By Gavin Jasper

Mortal Kombat: A Bloodsport by Any Other Name

Mortal Kombat went by a lot of names in its earliest days (the most popular candidate in the early days was reportedly “Kumite“), but one thing that remained the same throughout much of the project’s development was the commitment to making it the anti-Street Fighter. Or, as Ed Boon once put it, to make it the “MTV version of Street Fighter.”

The logic was hard to argue against. If Street Fighter 2 was the best at what it did, then this game should be the exact opposite of it in every single way possible

What’s impressive are the ways the small MK team distinguished their project. They used digitized captures of actors, which is particularly impressive when you consider that they weren’t even working with green screens. They just filmed some actors (mostly people they knew with martial arts experience) performing moves against a concrete wall and then manually removed the real-life backgrounds. It wasn’t too far removed from the techniques they used to construct a demo of their idea for Jean-Claude Van Damme

Of course, you can’t talk about MK without eventually talking about the blood. The game’s use of gore was certainly intended to catch people’s attention, which it absolutely did. While the MK team didn’t quite anticipate how the combination of digitized actors and extreme gore would put MK at the center of an emerging debate about video game violence, they rightfully predicted that the game’s violence was one of those things that people would force people to stop and look when they walked by and saw the game in action.

What’s really funny, though, is how those two qualities helped MK capture the feel of Bloodsport in ways that seemed both intentional and perhaps happily accidental. Yes, MK’s origins prove that it was clearly inspired by Bloodsport, but the ways in which MK most meaningfully mimics Bloodsport often aren’t talked about enough.

In Bloodsport and MK, you have this martial arts adventure that feels both wonderfully dingy and strangely fantastical. Just as Bloodsport told the unbelievable story of a global tournament featuring larger than life participants but tempered it with visceral combat the likes of which no human could survive, MK combined sorcery and mythological creatures with decapitations and punishing uppercuts in a way that shouldn’t have worked but proved to be too enjoyable to at least not be fascinated with.

Even the “awkward” animations you sometimes have to suffer through as a result of MK‘s motion capture process captured the spirit of Bloodsport and the ways that it replaced the smooth moves of someone like Bruce Lee with a more impactful MMA-esque style complimented by moments of absurd athleticism. It’s almost certainly also no coincidence that the average MK combatant’s most athletic move was a sweep kick. After all, a famous Hollywood legend says JCVD was offered the Bloodsport role after showing off his kicks to a producer.

Of course, when it comes to any discussion about MK and Bloodsport’s relationship, we certainly don’t have to rely on possible coincidences and speculation. Not only was an early version of MK literally ripped from Bloodsport, but as it turns out, JCVD did end up appearing in the game…

Johnny Cage: Jean-Claude Van Darn

If you step back and look at it, Mortal Kombat is basically the Super Smash Bros. for action stars of the ‘70s and ‘80s. Kano was a callback to The Terminator, Sonya Blade was seemingly based on the eternally underrated Cynthia Rothrock, Raiden was clearly inspired by Big Trouble in Little China (as was Shang Tsung), and Liu Kang was almost certainly a Bruce Lee substitute.

Then you have Johnny Cage. As a cocky movie star whose martial arts skills are largely based on his flexibility, it’s always been easy enough to suggest that Johnny Cage is a non-licensed nod to Jean-Claude Van Damme. Actually, many think that Johnny Cage is a bit of a mean-spirited parody of JCVD meant to mock him for turning the game down.

The truth is a little more complicated than that. Johnny Cage actually started as a character named Michael Grimm who was described as the “current box office champion and star of such movies as Dragon’s Fist, Dragon’s Fist II, and the award-winning Sudden Violence.” While his character model was reportedly also influenced by Iron Fist’s Daniel Rand, it seems that he was initially meant as a kind of broad substitute for the Western martial arts stars that took over the scene in the 1980s.

But yes, Johnny Cage is absolutely meant to be a parody of JCVD. I suppose where people lose the thread a bit is in the insinuation that he’s a jab at the star rather than an homage. While MK’s developers have said that Johnny Cage’s iconic “splits into a low blow” was absolutely a way to poke fun at JCVD and a scene from Bloodsport, it feels a little disingenuous to suggest the team was feeling bitter about not being able to put JCVD in their game and wanted to suggest that he was this star that was somehow too good for them.

What’s kind of funny, though, is that the rise, fall, and rise of Johnny Cage isn’t too dissimilar from what happened to JCVD. Van Damme was riding high in the early ‘90s on the back of films like Bloodsport, but a series of flops and some personal problems put his career in jeopardy later on. Similarly, Johnny Cage debuted as the prototypical Hollywood star but would fall from grace in the years that followed. He wasn’t even featured in Mortal Kombat 3 for the simple reason that he was the least selected character in MK 2.

Yet, over time, many people came to appreciate characters like Johnny Cage and actors like JCVD largely because they represented this golden age of absurd martial arts movies that weren’t always great (and were certainly usually a little problematic) but were ridiculous in a way that became much easier to love when weighed against increasingly self-serious genre works.

In his own way, Johnny Cage not only represents JCVD but the magic of a movie like Bloodsport and how such a silly little film could change everything because of (and not in spite of) its ridiculousness.

There’s another world in which JCVD became the digitized star of what would become Mortal Kombat, but due to a series of incredible circumstances, we don’t just need to project that reality on Johnny Cage to envision what that game might have looked like.

Bloodsport: The First Great Video Game Movie?

While it’s certainly funny enough that Jean-Claude Van Damme would go on to star in the Street Fighter movie after turning down what would become the first Mortal Kombat game, the cherry on the top of that story has to be the release of 1995’s Street Fighter: The Movie (the game).

That adaptation of the Street Fighter film bizarrely abandoned the design style of the Street Fighter games the movie was based on and was instead modeled after Mortal Kombat in an attempt to give Capcom a fighting game that could more directly compete with Midway’s runaway hit series. It failed spectacularly, but it did feature a digitized version of Guile as portrayed by JCVD in the Street Fighter movie. Van Damme even lent his moves for the game’s motion capture process.

Roughly four years after passing up the opportunity to star in Mortal Kombat (or Van Damme, as it would have likely been known), Van Damme ends up starring in a Mortal Kombat rip-off carrying the Street Fighter name. Call it a missed opportunity if you want, but to me, the bigger takeaway is that Van Damme may have missed the chance to recognize that he, Bloodsport, and Mortal Kombat were destined to be together long before the development of MK ever started.

See, there’s a scene in Bloodsport where Frank Dux and his new friend Ray play the 1984 arcade game Karate Champ. As one of the first successful arcade fighting games featuring multiplayer, Karate Champ would later be recognized as one of the fundamental pieces of the genre. John Tobias even said that Karate Champ was more of an influence on Mortal Kombat than Street Fighter was.

What gets me most about that scene, though, is the trash talk. Ray asks Frank “Aren’t you a little young for full contact?” Frank counters by asking, “Aren’t you a little old for video games?” They settle by playing another round.

It’s a simple sequence that’s hard not to look back on as an early indication that the popularity of films like Bloodsport would directly influence of new era of fighting games defined by competitiveness, arcade trash talk, and advancing technology that would inspire fans and developers to replicate the feel of being at the Kumite or, in our world, in a movie like Bloodsport.

In the same way that Mortal Kombat is basically an unofficial Bloodsport game, maybe it’s time to look back at Bloodsport as a kind of unofficial video game movie. After all, it may have debuted at the end of a strange kind of golden era for Hollywood martial arts films, but it was just the beginning of the golden age of fighting games.

cnx.cmd.push(function() { cnx({ playerId: "106e33c0-3911-473c-b599-b1426db57530", }).render("0270c398a82f44f49c23c16122516796"); });

The post Mortal Kombat and Bloodsport: The Strange Connection That Changed Gaming appeared first on Den of Geek.

from Den of Geek https://ift.tt/3eiNTKM

0 notes

Text

Imagination vs Speculation

Fiction has two modes: the imaginative and the speculative. The mode that has to do with pure, unbridled invention and the mode that tries to think logically about rules and consequences. So the imaginative parts of Lord of the Rings have to do with the whole-cloth contrivance of things that don’t exist: ents, hobbits, dwarves. The speculative parts have to do with how, given the rules of Tolkien’s universe, his characters might behave. What would it take for a homebody hobbit to leave home? This principle goes for stories that lack ‘fantastic’ elements as well. The imaginative part of Huckleberry Finn is Huck and Jim and their life circumstances. The speculative part is what it might take for Huck and Jim to bond and run away. Imagination is Jim finding a dead body. Speculation is Jim preventing Huck from seeing it.

(That good speculation requires a good imagination is a given. But it is still different, for my purposes, from the act of creating something from nothing.)

In order for speculation to be concerned with what might happen though, it has to be concerned with what is. Every act of speculation speaks as much about what rules a writer thinks govern a fictional world as it does about how those rules might manifest. And if a writer is trying to speculate about how reality could go, as many writers are, then they are proposing hypotheses about the way reality is. In a third season storyline of The Wire, for example, the show imagines that Baltimore establishes a zone for the legal use and exchange of drugs. It then speculates how the government, police, and citizens would react—revealing general principles about what motivates these people and why.

But fiction is weird. Fiction usually isn’t concerned with either a fictional reality or a real reality—but both, simultaneously. So in a satirical movie like Election, the story is at once attempting to distill a supposedly real phenomenon (what happens when unscrupulous people butt up against cowards and innocents) and be consistent within a necessarily heightened movie reality. Which means that fiction, in order to feel ‘correct,’ has to scan according to both realities. If you don’t think that automatons of ambition exist, or you don’t think that they succeed in the end, or you think using Tracy Flick to depict that kind of person puts unrepresentative blame on the heads of teenage girls—the speculation doesn’t track for you. On the other hand, based on what the movie establishes about Tracy Flick, we would also consider it ‘illogical’ or bad speculation if she suddenly behaved selflessly.

Interestingly, the more metaphorical or satirical a work is—in other words, the more it is attempting to have meaning—the more, I would argue, it becomes concerned with ‘real’ reality. The more, that is, its implications about reality affect whether or not it works. If I’m watching Transformers, it doesn’t actually matter that much whether it makes sense that a giant alien robot would pal around with a teenage kid. Because Transformers isn’t trying to claim much about reality.* But if I’m watching a production of Rhinoceros, it sure as hell matters whether I think fascistic impulses exist, or whether they colonize people in the absurd, virulent way Rhinoceros depicts. It matters less whether Rhinoceros establishes complicated rules for its fictional world. Though it should be (and is) self-consistent.

*(Insofar as Transformers is trying to distill a reality, one might claim it is trying to distill what a certain attitude or fantasy looks like. So it is consistent with the reality of the terms of that fantasy—cars, heroism, hot girls— rather than whether or not that fantasy is especially likely to happen. “If I were trying to make the perfect heterosexual boy fantasy movie, what would I include? In other words, what is the perfect heterosexual boy fantasy movie? What defines a heterosexual boy?” In a thoughtless execution of the het boy fantasy genre—XXX? Crank? I don’t know—this kind of consistency would matter even less.)

What am I getting at? I want to set aside the definition of ‘speculative fiction’ that acts as a euphemism for science fiction. And I want to examine what makes good or bad speculative fiction, and what counts as ‘speculative fiction’ in the first place. Right now, the terms ‘science fiction’ and ‘speculative fiction’ are a confusing conflation of three different genres:

1. Fantasy with tech or futuristic trappings. Star Wars, Transformers.

2. Speculation about the consequences of a scenario that doesn’t exist (a technological innovation, a social innovation, a crazy circumstance). Looper, A Handmaid’s Tale, Asimov, Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, Contact.

3. A technology or a fantastic setting as a metaphor for a real world phenomenon. The Forever War, Metamorphosis, Frankenstein, Xenogenesis.

There are good and bad executions of all of these genres. And of course they tend to overlap. But in order to talk about whether a given work is failing or succeeding, we have to talk about which realities the works are trying to make claims about (or take as a given), and therefore whether or not the claims are accurate or convincingly depicted.

The first category mostly only needs to scan according to its fictional reality. When this kind of story makes a claim about real reality, it usually tends to be a claim about human emotion or human values (what is tragic, what is virtuous, what is cool). The questions you ask about Star Wars are things like “Is this fun?” or “Does it make sense that Luke is sad here?” The last category, in turn, mostly needs to scan according to its real reality. Something like Xenogenesis makes you ask questions like “Is this effectively evoking the conflicted, shell-shocked experience of cultural assimilation?” Frankenstein is more of a story about hubris rather than a story primarily about the actual consequences of reanimating the dead. Stories in this category can be tremendously complex on the narrative level, and care about being consistent and exciting on that level, but the speculation part tends to exist primarily in the service of a concept rather than itself.

I think of it this way: speculation in service of a concept will be closed, rather than open. The Wire’s Hamsterdam storyline is open because there was no way it really had to go, other than the way that the writers thought logically sprang from the state of Baltimore’s citizens and civic institutions. But something like District 9 is trying to convey a pre-established position about the mechanics of prejudice and othering. District 9 is more effective if its narrative logic is sound, but there was also no way District 9’s plot was going to depict any fallout from alien contact other than xenophobia. Top-down rather than bottom-up storytelling. Evidence-based versus theory-based. This isn’t inherently a good or bad thing, for the record, just a distinct difference in genre. In metaphorical stories, the logic of something is considered more or less known to the author; the problem is how to get other people to internalize the logic.

True speculative fiction (category 2) and true narrative fiction (category 1) seem to resemble each other more than they do metaphorical fiction (category 3) because they both take the bottom-up approach. What is something like a sitcom (situational comedy) other than putting characters in a scenario and asking what will happen? Beyond approach, what Friends and Star Wars and Game of Thrones and Isaac Asimov all have in common is a curious paucity of thematic content (that is: it’s difficult to say what they are “about”), but not in a bad way. Extremely hard speculation like The Wire tends to not be terribly thematic because theme requires a certain amount of artistic control that epistemically honest speculation doesn’t lend itself to. When works of hard speculation are thematic, and when they’re good, they seem to mostly lend themselves towards themes about the complexity of systems. Which makes perfect sense. Hard speculation is also different from “hard science fiction” that mostly applies its hardness to its setting and not to its narrative. Only occasionally, like in things like The Silmarillion, does a hard worldbuilding story understand that its worldbuilding is the story and put the focus there accordingly.

All this said, most works of speculation are in-between things. Things like Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind or Brazil or Her or Children of Men or Contact or Snowpiercer. Eternal Sunshine is fairly honest speculation about how people would use a memory-altering technology, but the only reason the story proposes that technology is to explore things about romantic relationships. Most stories, in other words, choose their speculation in a thematically pointed way, even if they’re not transparently allegorical.

The thing I want to figure out is why the way that something like Eternal Sunshine speculates thematically is so much better than the way that something like Her does, despite the fact that they have similar subject matter and approach. While both pure narrative and pure metaphor and pure speculation can all, to a certain extent, get away with ignoring one or both of the above, blended works seem to ignore the other categories at their peril. The absolute worst executions I can think of are the metaphorical stories that are undermined by a refusal to speculate. Stories that have such a poor understanding of consequences or such a lack of curiosity about them that it ruins the metaphorical and literary power of the reality they are trying to convey (see: what it means for a work of art to take itself seriously). A good metaphor will not simplify reality, but will open it up, and this is impossible to do without a good understanding of what reality is (or a respect for the fact that understanding reality is overwhelmingly difficult).

Works like Her and Snowpiercer seem weak to me because their artistic reach extends their grasp, but in a lazy way rather than a forgivably ambitious way. They imagine overly wholesale fictional circumstances: all the people fall in love with their computers, all of society is trapped on this train. These are huge statements about the pervasiveness of both loneliness and the stratification of society, yet neither of them are convincing on the individual character or narrative level, and so their huge claims fall flat. Theodore mostly seems to be lonely because he’s an almost inhumanly stunted person. I found myself wishing the movie were just a simple story about an individual in the real world that falls for a catfisher. Similarly, I felt that Snowpiercer would almost be more convincing as a story set in an actually oppressively stratified country. Those “realistic” stories would be less symbolic, but far richer. Although movies like The Matrix and Children of Men also have overly ambitious speculative conceits, both put considerable effort towards the complexity and excitingness of their narratives and also make much smaller claims about reality. The Matrix is a metaphor for a more generic feeling of unreality and aimlessness, while Children of Men tries to be a thriller in a speculative circumstance, but makes few sweeping, moral claims about society that it has to prove. Poor speculation, in other words, takes its ideas as “given” and uses metaphor as a kind of autotune to conceal a lack of work.

[Credit both to Peli Grietzer for autotune as a figurative concept, and Gabe Duquette for this specific usage].

176 notes

·

View notes

Text

.

#when people dont realize that girl crush isnt actually WLW#it's WlW for the purpose of loving a man...#she wants to be the girl because she wants her boyfriend#like is this a difficult concept to understand? not really but people sure make things extra all the time#i know y'all like connecting the dots even when there's no dots to conmect but lets use some critical thinking skills and work through this#to clarify it depends on the person singing#in its originality its not a song about a woman loving a woman#but harry singing it would change the meaning of the song#also i see a lot of people saying the country music industry is sexist and im just gonna say..you must not know the country music industry#there's more idolized#revered and independent women in country music than any other genre historically#there's more sexism in rap & pop with the language used to talk about women#its kind of absurd that people make generalized claims about a whole genre the way people do when it comes to country music

0 notes

Text

Missed Classic 59: Deathmaze 5000 (1980) – Introduction

Written by Will Moczarski

One of the creepiest gaming experiences of my childhood was called Asylum, a downright crazy text adventure with graphics scaring the hell out of me back then. As I never actually managed to complete the game it has kind of stuck with me over the years and hung over my head like an unfinished memory. To finally come to terms with it, I’ve decided to blog through the adventure games developed and published by Med Systems Software of which Asylum (confusingly aka Asylum II) is the last.

The rather unknown company was founded around the beginning of the 1980s and first released a series of simple maze adventure games called Rat’s Revenge, Deathmaze 5000 and Labyrinth for the TRS-80. They cannot be found anywhere on MobyGames and the early history of Med Systems is generally in the dark but sometimes retro gaming calls for a little bit of digital archaeology, right? The TRS-80 was a budget computer released by Tandy Radio Shack in 1977, along with the Apple II and the Commodore PET 2001 – the three of them are often referred to as the “first trinity” of homecomputers. Ironically dubbed the “Trash-80”, its place in gaming history was secured by a certain Scott Adams who managed to port his version of the original “Advent(ure)”, named Adventureland, to this very simple micro machine. Med Systems was yet another prolific developer of text adventures for the TRS-80, focussing on simplistic graphics with a 3D effect established by its particular perspective. Their early games look like a more technical, not so much hand-drawn variety of Roberta Williams’s Mystery House and I’d like to see some release dates to know who actually came first and whether we’ll have to rewrite history on this one. However, I’m not entirely sure that the first three games can be regarded true adventures just yet but time will tell if they are indeed “missed classics” or curiosities best forgotten. The Institute, written by Adventuresoft alumnus Jyym Pearson and released in 1981, and Asylum II, written by William F. Denman jr., I remember to be (somewhat) quality stuff, though, so a historical write-up may well be in order.

Rat’s Revenge, the first of the games, has left the fewest traces online. While its follow-ups appear to be remembered fondly (although they are scaringly labeled as practically unsolvable), I cannot turn up anything else about this apart from it having been written by Frank Corr jr. The game itself can be found on “Magic Chris’s Asylum page”, a labor of love dedicated to the Med Systems games complete with a preset TRS-80 emulator and all necessary disk images. While Rat’s Revenge may not actually be an adventure game in the truest meaning of the word, it’s an interesting starting point for two reasons: As “digital antiquarian” Jimmy Maher has pointed out, genre of maze games is one of the predecessors of proper interactive fiction, notably Hunt the Wumpus (1972) which works very similar to Rat’s Revenge, only without graphics. Additionally, Med Systems Software is credited as one of the earliest companies to release commercial games implementing proper 3D graphics which ties in nicely with mainstream gaming history as 1980 was also the year that Atari’s Battlezone hit the arcades, wowing everybody with 3D vector graphics, and one of the last games released by Med Systems for the ZX Spectrum – before they were bought out and subsequently closed down by Screenplay – was Phantom Slayer, one of the most notable predecessors of the first person shooter genre. It’s very interesting that the in-game manual of Rat’s Revenge explains the possible depictions of the rooms, not trusting the player to decipher the unusual perspective correctly but making sure that s/he gets what it ought to represent.

A 3D graphics tutorial! DOOM this is not.

Rat’s Revenge is more maze than adventure game but still, like Hunt the Wumpus for the whole genre, a precursor for things to come. The three subsequent games all use the same visual style and require the player to map the 3D mazes to progress in the story. Rat’s Revenge, however, has next to no story. You play a rat that has to escape the stereotypical labyrinth and your plot for “revenge” is to find a piece of cheese hidden somewhere in the maze to avert starvation. A dish best served cold, indeed. Although the title most likely hints at a 1965 song by the band The Rats, it doesn’t make much sense without this reference. The mazes are generated randomly and the player can decide whether s/he is a novice or not, resulting in different-sized levels. Success is telegraphed by a final graphic showing the piece of cheese along with the words “Delicious.. burp!” Afterwards the player is shown a bird’s eye view of the maze and the path s/he took to get through it. The score represents the deviation from the “main trail”, ie. the best possible outcome, thus the lower the score the better the result. It’s apparently possible to use a built-in hint system but I didn’t need to use it and have no clue as to how it works. The game is much more fun than taking the stairs in any early Sierra game but still very simplistic. A small maze takes roughly a minute to be set up, a large maze takes considerably longer – three to five minutes according to the game. “You may be sorry”, it warns you if you pick the large maze, and indeed it’s much harder not to starve in this one. As a novice, small numbers in the corner of the screen hint at your proximity to the piece of cheese. If you get closer in any mode you are informed that you “smell the cheese”. Mapping is essential in the large mazes as all of the twisty passages really do look alike and it’s fairly easy to get lost. It’s quite a relief to finally get to the cheese and though the game is a simple maze genre piece it’s still fun. To rate it with the PISSED system would be a bit absurd, though, as it’s not really an adventure game. It still felt necessary to include it for the sake of completeness, so onwards to Deathmaze 5000 it is!

WON! (burp)

Oh, the embarrassment!

Deathmaze 5000 was presumably the second Med Systems game and apparently co-written by Frank Corr and William Denman. It is the first part of the so-called “Continuum Series”, a succession of 3D adventures with simplistic graphics combining elements of maze games with adventure puzzles, a parser and an inventory. The goal of Deathmaze 5000 is to escape a five story building – you start on the top floor and slowly make your way down, past monsters and traps. Med Systems dubbed it “the most complex adventure ever written” and claimed that only two people had successfully solved it by December 20, 1980 – we may be in for a rocky ride here.

The survival aspect is further stressed by the need to find food and torches; once again, there is a built-in hint system and movement is very similar to Rat’s Revenge. Let’s see next time how far we’ll get on our first attempt – the race is on!

I think I already am…

Note Regarding Spoilers and Companion Assist Points: There’s a set of rules regarding spoilers and companion assist points. Please read it before making any comments that could be considered a spoiler in any way. The short of it is that no points will be given for hints or spoilers given in advance of me requiring one. Please…try not to spoil any part of the game for me…unless I really obviously need the help…or I specifically request assistance. In this instance, I’ve not made any requests for assistance. Thanks! This is also an Introductory post. Don’t forget that you can make a guess at the PISSED rating for bonus CAPs.

source http://reposts.ciathyza.com/missed-classic-59-deathmaze-5000-1980-introduction/

0 notes

Photo

Rap is Crap

For many within the conservative movement, rap is a uniformly negative reflection of the worst ills and excesses of society. It romanticizing everything wrong with the way society is headed, and the more hard-lined who hold this view believe it isn’t even music in the first place. This line of reasoning is frequently and most notably echoed by the leading figure of the conservative movement, Ben Shapiro.

Shapiro has commented on rap on a number of occasions, but he published an article that neatly summarizes his position on this cultural force. Titled ‘Rap is Crap,’ it’s a phrase every conservative who reflexively mocks rap has at one point thoughtlessly sputtered. It’s thoughtless not because there aren’t respectable reasons to simply not like rap; people dislike whole genres undeniably often, after all. Think of the common statement “I love all music except country”. But disliking a form of music is much different than claiming that opinion is an absolute. In his piece, Shapiro holds up T.I. as a representative model of rap as a whole, but he’s also prone to purposely misinterpreting rap. His analysis of Cardi B’s music video for Bodak Yellow comes to mind. Throughout, he’s confused. He mocks the ungrammatical nature of her lyrics, and he thinks that her being in a desert is some sort of political statement on gender equality in Saudi Arabia rather than a randomly exotic backdrop for her music. These throw into doubt the sincerity of Shapiro’s “takedown.” Is he genuinely convinced that people are reading into this music video that Cardi B is holding up Saudi Arabia as a beacon of gender equality? And though some interpret her song as a statement on feminism, it’s doubtful that the artist herself had thought that much into it. In one breath, Shapiro scoffs at the seeming thoughtlessness of this kind of rap, and in another, he assigns political motivations where convenient. His confusion doesn’t end with Cardi B’s sand dunes.

He pushes on, in reaction to another popular track, so very confused by Future’s “where ya ass was at?”, well, in keeping with his rigid attention to grammar. You begin to wonder whether he’s actually unable to translate Future’s question into plain English. Shapiro likely knows what he means, but he’s criticizing it for being ungrammatical. That hardline way of thinking ignores that much of art eschews strict adherence to rules, grammar, and reality under creative license. The meaning, in spite of the lyrics’ lack of grammar, remains intact. Future is conveying something that, at its core, isn’t essentially unconservative. He’s asking the question of where those near to him now were when he was working his way up the ladder, harkening to the fact that his success had to be earned by him alone. There are many ways to convey this sentiment, but isn’t it more important that such messages get across in the first place?

Language is a tool, not an end unto itself. After all, it’s doubtful that a single, basically intelligent person is going to start ending their questions with prepositions and tossing in “your asses” just because a rapper did. At the same time, one can encourage young people to master the English language, while enjoying rap as a simple form of exaggerated entertainment. And it would be equally silly to mock or act confused while listening to Jamaican dancehall artists when they say “tings” instead of things. His tendency to overthink rap and inject political motives that usually aren’t there blinds him to properly addressing both rap’s flaws and its merits. Say what you will about rap or any other genre for that matter, but if you approach it with the mentality that it’s bad in every way imaginable, it’s no surprise when you’re unwilling to be receptive to it in every way. Applying a political lens to everything is harmful, whether that comes from the feminist or racially tinged corners of the radical left or the right. It’s perfectly fair to dislike most of a genre, but it is essential to understand its appeal from a politically neutral standpoint.