#it's much more favorable to advocate for BOTH nuclear power and renewables

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

If you don't support nuclear energy, you aren't an environmentalist and you support the agenda of oil and coal companies, I hope this clears things up

#politics#environmentalism#environmental issues#nuclear energy#literally nuclear power is the base line for clean energy#we can't just spam renewables#those are probably gonna take more space and resources than a reactor combined#most of them are dependent on a lot of things and may even harm the environment too (hydroelectric dams)#it's much more favorable to advocate for BOTH nuclear power and renewables

0 notes

Text

The 3 Ps Assessment: Parties, Political Interest Groups, and PACs

Party Platforms

Republican:

Republicans want to continue using nonrenewable energy sources like coal, oil of nuclear power. They want to rely on coal the most and usually advocate for using it because its abundancy.

I don’t agree with the Republican stance because people definitely need to work on the pollution problem in order to prevent humanity from being wiped out. While we need to use more renewable forms of energy, it would be nearly impossible to just switch all power to natural sources because it would be inconvenient for many places. For now, I believe we need to work on reducing the amount of pollution being generated and find ways to switch to using green energy.

Democrat:

Unlike Republicans, Democrats are strongly opposed to using more coal power. Instead, they want to rely more on renewable energy sources and become a leading country to promote and encourage its use, even if it comes at a great economic cost.

I agree with the Democrat stance because I support using more renewable energy sources than we already are. I think the environment would definitely benefit if America increased the amount of energy used by renewable energy resources. However, I also think that switching all power to natural isn’t possible, and that people need to gradually shift in order for people to accept using green energy.

Libertarian:

The Libertarian platform does not directly establish their view on renewable energy. Instead, it only states the party being opposed to the government controlling anything about energy. This involves the pricing, distribution, or production of energy. It seems that libertarians would prefer people to establish their own ways of using energy without any government regulations.

I disagree with this approach because if the government doesn’t create some sort of incentive, many people won’t be convinced to use renewable energy resources. The whole world needs to change its ways together in order to keep the environment sustainable. Things must change on a national and global scale if anything is to get done. There’s no way America itself will be able to move to natural energy resources if it isn’t enforced by the government.

Green:

The Green Party advocates using numerous renewable resources such as wind, solar, ocean, small-scale hydro, and geothermal power. They’re hoping to transition to 80% of energy being green by 2030, and 100% by 2050. In addition, they want to decrease the use of coal and methane, are also very strong about ending the use of nuclear power.

I agree with much of this stance, but I don’t agree with it as much as the Democrats’ stance. The Green Party seems to be more liberal about the environment, to the point where it’s a bit too extreme for me. While I’m happy that the party wants to switch to 80% renewable energy by 2030, it unfortunately doesn’t seem as realistically possible anymore at the current rate. And I do believe that nuclear power is a possible necessity and might be something people may need to rely on.

Peace and Freedom:

The Peace and Freedom Party supports having a multi-source energy system, using solar technology and other renewable, nonpolluting energy sources. They also want to eliminate nuclear power plants and end fossil fuel dependence.

This party’s stance look beneficial to me. However, their wording makes it seem like they are very extreme about getting rid of fossil fuels and nuclear power. In that sense, I don’t agree with how firm they are about getting rid of those two things because I think it’s important for the world to make gradual, progressive changes. I don’t think people can just cut off fossil fuel use right away, nor do I think people should get rid of nuclear power that fast. It might be necessary to keep nuclear power as an option in case we need it.

I identify with the Democratic Party’s position the most. This isn’t surprising because my political alignment test reflected that I am moderately liberal, which is what I already thought I was. In addition, my whole family holds the same liberal ideals, so I wasn’t surprised that I identify the most with Democrats. Because I have always supported the use of renewable resources, I knew I would probably be against the Republican stance. I was against the Libertarian stance because I didn’t agree with how they didn’t want the government playing any role in regulating energy. And although I agreed with some parts of the stances by the Green Party and Peace and Freedom Party, I thought their ideals were a bit too extreme and unrealistic. There isn’t a presidential candidate to vote for now, but I’m assuming that I would most likely vote for the Democrat candidate.

Interest Groups

National Interest Group

Interest group name: Sunrise Movement

Position/perspective: Sunrise Movement hopes to make climate change an urgent, national priority, end the corrupting influence of fossil fuel executives on politics, and elect leaders who stand up for the health and wellbeing of all people.

Beliefs: Sunrise Movement believes people should stop giving so much taxpayer money to oil and gas CEOs in order for climate change to come to a halt. They want the world to transition to a 100% clean energy as fast as possible. And after such a transition, they believe in providing for the workers in the fossil fuel economy who will be displaced, addressing who will pay for the climate impacts that are locked in already, and ensuring that those least responsible for climate change will not bear its cost. In addition, they also want to halt all fossil fuel projects such as any infrastructure projects in order to avoid unnecessary disasters.

Legislation: During primary elections, this interest group only endorses candidates that take the No Fossil Fuel Money Pledge, which is a pledge to reject contributions from the oil, gas, and coal industry and instead prioritize the health of families, the climate, and democracy over fossil fuel industry profits.

Location: This group is very large and doesn’t have a main meeting place. Instead, there are hubs in many states like California, Oregon, Washington, Rhode Island, Ohio, Pennsylvania, New York, New Mexico, Minnesota, Michigan, Massachusetts, Florida, Alabama, and Washington D.C. The hub in California is actually in the Bay Area, but it seems it hasn’t been very active since 2017, so I don’t think there’s any meetings close by.

Volunteer opportunities: There is a way to volunteer as an intern in the Sunrise Semester Internship Program. Interns can spend up to 40 hours per week volunteering to support progressive local candidates and to make climate change a more significant political issue. They will learn to participate in extensive leadership development, political strategy, and social justice trainings.

Additional developments: Sunrise Movement is still very much active in the present. They have been holding multiple rallies and endorsing many candidates for the 2018 midterm election. Although the group has stated on their website that they are not aligned with one political party or the other, all the candidates they have endorsed before and in the present are either new candidates to politics, or democrats. But this shouldn’t surprising since the Republican stance typically favors the use of fossil fuels over renewable resources.

State Interest Group

Interest group name: California Environmental Justice Alliance (CEJA)

Position/perspective:

Beliefs: CEJA wants to make great use of rooftop solar energy and to get rid of “dirty power” like power plants and oil refineries. They believe dirty power is driving climate change, while also poisoning families and communities. To take care of the environment, CEJA supports transitioning to using 100% of energy from renewable resources. They believe that the best way to address the environment is to start with the communities who have dealt with the burden of pollution for decades, and lift up the leadership of those who have been impacted the most. They strongly advocate against racism and that a healthy economy starts with healthy communities, where all people have jobs that are not toxic and can support families, and neighborhoods.

Legislation: In 2015, CEJA co-sponsored and helped passed a bill by Assemblymember Susan Eggman. This bill was AB 693, The Multifamily Affordable Housing Solar Roofs Program. It is the nation’s biggest solar program for low-income renters in history. And it’s the first one to direct a majority of the savings created through use of solar energy directly back to the utility bills of renters.

Location: The main office of CEJA is located in Oakland, California. Its exact address is 1904 Franklin Street, Suite 610, Oakland, CA 94612. But there is also a Sacramento and Los Angeles Office. There don’t seem to be any upcoming meetings scheduled I could attend.

Volunteer opportunities: There are no volunteer opportunities, but they do have a page on their site about hiring people. However, there are no open positions at this time.

Additional developments: It’s interesting that this interest group is not only founded on the principle of the environment justice, but also racial justice too. CEJA doesn’t seem as powerful or influential as a national interest group, but it seems they are still impactful and are doing a good job at giving their best effort to carry out their ideas.

Both groups appear to be very well put together and thoughtful. I like how they’re both adamant about turning climate change around, and they have a very organized plan about how to approach the problem. I did feel Sunrise Movement was more successful in being powerful and influential with more people involved in it than CEJA. But I do like how California still has quite a few state interest groups that will hopefully drive California to transitioning to more renewable energy faster than other places. Both groups seemed to target young people as an audience in order to persuade them to make a difference in the future. And both groups were also supported by other groups that advocate protecting the enviroment.

PAC

PAC name: PG&E Corporation Employees Energy PAC

Position/perspective: PG&E want to increase the use of clean and renewable energy, reduce the impacts of our business, protect sensitive habitats and species, and work locally to help people use energy more efficiently.

Money: The total receipt is $1,066,361. They have spent $1,088,102. They currently have $412,062 on hand.

Budget: 44% of their money goes toward Republicans, while 56% goes to Democrats.

Donors: All the donors listed are individuals that work for PG&E. This shows that all the people donating are supporting their cause even more and want to elect people that are conscious of the environment and hope to take care of it.

1 note

·

View note

Text

July 18, 2021

My weekly roundup of things I am up to. Topics include upzoning, energy forecasts, advertising and overall consumption, and road damage.

Efficacy of Upzoning

This week it was suggested that I watch this video, which is critical of the wave of upzoning policies going on now to deal with high housing costs. The coverage of issues around upzoning is fairly comprehensive. Some points I would agree with, some I would disagree with, but overall it makes the anti-upzoning case as well as anything else I have seen in a compact form.

I would point to this video as a challenge for the YIMBY movement and other upzoning advocates. Do you have credible responses to the issues raised here? The main points, as I see them, are aesthetic preference for low density as expressed through prices, externalities of density such as traffic and crime (crime is not addressed in this particular video, but it is in some of his other videos and is observed to correlate with density), and whether prices will actually respond to upzoning as hoped (here I think the facts are against him but not entirely). It may be morally satisfying to derisively refer to all opponents as NIMBYs, but this does not address substantive issues, nor does it win hearts and minds.

I have a challenge for advocates of zoning as well. Zoning is arguably the most extensive form of central planning in the United States, and some economists have estimated that it costs the US economy trillions of dollars per year. The cost has been estimated in the hundreds of thousands of dollars for a typical single family lot. Given this, are all forms of zoning really worth the cost, and are there less heavy-handed ways to achieve goals such as preservation of low-density neighborhoods?

Energy Forecast

Coming right after the BP Statistical Review of World Energy, the IEA has a forecast of energy demand for next two years. They expect that by 2022, coal will not only make up the big drop in 2020, but also the smaller drop in 2019 to set a new record. Natural gas should set a new record this year. Nuclear power will grow in 2021 and 2022 but not have made up the 2020 drop by then. Wind and solar will be the big growers, constituting almost half of new supply in 2021 and more than half in 2022.

It should be crystal clear now, if it wasn’t already, that renewable energy is mostly augmenting the fossil fuel energy supply, rather than replacing it (see e.g. York, among other researchers, for an illustration of this effect). This is not an anti-renewable argument. I am also a (partial) believer in the argument of Ayres and Warr that usable energy is a primary driver of economic growth, so the growth of renewables should be very good for the economy. If we can achieve breakthroughs in next generation nuclear fission or fusion, that would also be very good for the economy. This is analogous to energy efficiency and the rebound effect. There needs to be deliberate policy, such as carbon pricing, to take emissions out of the system; deployment alone will not do so effectively.

That takes us to a new paper by Avarez and Rossi-Hansberg, which I found through John Cochrane’s blog, which models the effect of carbon pricing and finds it will mostly delay, rather than actually reduce, overall emissions. I find this surprising and rather distressing. There are two points that Cochrane makes about the paper to understand why this might be the case.

First, since fossil fuel reserves are finite (at least at a given price point and technology level), reducing consumption today will increase reserves tomorrow, thus lowering price and stimulating consumption.

Second, fossil fuels and other forms of energy, particularly renewables, are substitutable but not infinitely so. Coal is generally baseload power, natural gas is dispatchable, and wind and solar are variable sources. The latter can be turned into baseload or dispatchable power with batteries, but only at major cost. Unlike fossil fuels, wind and solar cannot be used directly for aviation, cement, steel, and many other industries. This is an important point to keep in mind when you read a “solar is cheaper than coal” article and wonder why coal use still goes up.

Lest you think the above is an anti-carbon pricing argument, keep in mind that the two points apply to any policy that deliberately reduces fossil fuel usage, including pipeline opposition, clean energy standards, etc.

If we believe that future society will be wealthier and more technologically advanced than present society, something that I still think will be the case but wouldn’t take for granted, then delaying emissions may still be worth it because future society will more easily be able to mitigate and adapt to the consequences of global warming.

Effectiveness of Advertising in Stimulating Consumption

One of the common criticisms of modern economies, and of capitalism in general, is that they require constant growth to be viable. However, in wealthy countries (and increasingly in most countries), most people now have their basic needs easily fulfilled. Therefore, we need marketing to stimulate the desire for consumption and maintain growth.

There are a number of issues in this argument that can be interrogated, but I’ll look specifically at this idea that advertising increases overall consumption.

The idea at least seems superficially plausible. I’m sure it can be traced into the misty recesses of deep time, but the hypothesis that advertising increases overall consumption was most notably expounded in John Kenneth Galbraith’s 1967 book The New Industrial State, which is a far-reaching critique of what he saw as an economy managed by large corporations. It would seem obvious that advertising at least increases consumption of the good being advertised; otherwise, what is the point of doing it? Increased consumption comes with a range of environmental impacts, and for this reason the possible effect of advertising has come to the attention of some environmentalists; see this blog post for a typical example.

It doesn’t seem, though, that evidence since Galbraith’s book has backed up this hypothesis. This book chapter finds that advertising does in fact increase demand for the good being advertised, but not overall consumption, so advertising comes at the expense of rival goods. A couple of studies specifically dealing with alcohol (this and this) and tobacco (this and this) find that advertising increases consumption of a particular brand but not overall consumption; these results are relevant when we consider policy proposals to regulate advertising of these goods of dubious social value. The Montreal Economic Institute, a free market think tank, has this brochure arguing against the hypothesis.

I wouldn’t consider the above evidence to be conclusive, but I wonder what evidence can be marshaled to support the idea that adversing stimulates overall consumption. I haven’t seen anything compelling yet.

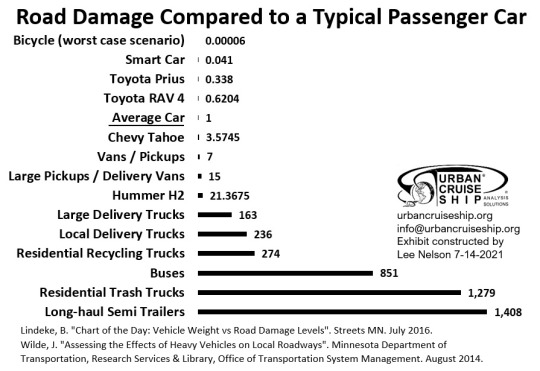

Road Damage

When vehicles travel over a road, they inflict wear and tear, which has a cost. Larger vehicles inflict more damage. How much more? It turns out this question is not as well settled as I would have expected.

Based on two main sources, I put together the following plot.

Both sources rely on the rule of thumb that road damage is proportional to the fourth power of axle weight, a result that was found in the AASHO Road Test in the 1950s. In addition to being old, it seems that road damage depends on a variety of factors, such as tire condition, the type of pavement, climate, and others. The ratio of damage of a typical semi truck to a typical passenger car has been given at 9600 or in the 300s. The Road Test also didn’t examine vehicles with weight comparable to bicycles, so while we expect those to be low, the reported numbers aren’t very meaningful.

These figures become especially relevant when we consider road maintenance and who should pay for it. The overall governmental budget, including federal, state, and local, for road repair worked out to $572 per capita in 2018. If the above figures are correct, or even if the lower figures of Bradley and Thiam are correct, then the trucking industry should pay most of this bill. Road damage can also be incorporated into development fees.

Road damage has often been given as a reason to disfavor cars and favor active transportation. However, if the numbers in the True Cost analysis are to be believed, then trucking is responsible for 99% of road damage, which by the Urban Institute analysis would leave less than $6/capita/year for cars (some road damage will also have non-vehicle causes, such as water freezing in cracks). This is too trivial a sum to have a meaningful impact on development patterns except for freight mode.

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Great Siphoning: Drought-Stricken Areas Eye the Great Lakes

"Water, water everywhere" is the egalitarian vision of those who don't have enough of it and would like to tap the Great Lakes to get it.

Outside Two Harbors, Minn., on a cliff overlooking the broad expanse of Lake Superior, you are overwhelmed by grandeur — shimmering water, crashing waves, a down-bound ore boat on the horizon, miniaturized by distance.

As you fill your senses, you may be unaware of the invisible others behind you — 2,000 miles or so behind you, to the southwest — eyeing the Great Lakes in another spirit, coveting all that water.

Lake Superior is big, all right. It and the other Great Lakes contain one-fifth of the whole world’s fresh water and, get this, hold enough to submerge the continental U.S. under 10 feet.

Those far-off onlookers thirst mightily for the Lakes’ 6.5 million billion gallons of fresh water that, to them, just sits there before running off to the ocean. Wasted.

It’s easy for us lake-landers to dismiss such thoughts, but those in the American Southwest are up against a 17-year drought that keeps getting worse. After an unusually warm winter, it’s expected to worsen still more this summer due to a dearth of mountain snow that will again leave Colorado River flow far below normal, with forecasts of dry and very hot weather à la La Niña.

What’s beyond scary is that NASA computer models indicate that the West could be facing a 50-year megadrought, the first such event since long before Europeans even knew North America existed. Moreover, higher temperatures and wind wrought by climate change dry things out and increase demand for irrigation water while at the same time increasing already problematic evaporation rates from reservoirs and canals.

Primary water sources in Arizona, Nevada and Southern California are dangerously low. Benchmarks are the historically low Lake Mead reservoir behind Hoover Dam (built in 1930) and similar low levels of Lake Powell on the upstream end of the Grand Canyon. Las Vegas, which draws 90 percent of its water from Lake Mead, has twice lowered its intake “straw” due to falling levels.

One relief option is desalination of ocean water, but scaling up that technology has proved frustratingly difficult and outrageously expensive. The largest existing plant, at San Diego, provides only 7 percent of that city’s needs.

Another option is to strictly restrict water use, but that’s politically dicey and can’t get much beyond talk.

Then there’s a plan to spend gazillions to capture several of Alaska’s free-flowing rivers with a grand network of dams, canals and tunnels to divert water south to the Colorado basin. It seems that the drought is getting serious enough so that even far-fetched ideas get a look.

So OK, now what?

To desert dwellers, an idea that makes intuitive sense is to pipe Lake Superior water to where it’s “needed.” Such a project would be staggeringly expensive but technically doable; besides, the Great Lakes surely wouldn’t miss, say, 50 billion gallons — would they?

The populace all around the Lakes is rock-solid against shipping any water anywhere, and advancing any diversion plan would set off political warfare.

Or perhaps one should say “renew hostilities.” This story isn’t new. In 2007, New Mexico’s then-Gov. Bill Richardson suggested a Great Lakes diversion when the Western drought was only six years old. Following bloodcurdling protest, fellow Democrat Jennifer Granholm, then Michigan’s governor, told Richardson to zip it. A year later the eight Lakes states, including Minnesota, adopted — and President George W. Bush signed — a compact banning diversions without concurrence of all signatories.

Plus, an international pact gives Canada (along with the federal government in D.C.) a veto over any transfer.

But because the ultimate power rests with Congress and the president, multistate compacts and international accords can be false security. What’s done can be undone, as evidenced by all the undoing from today’s Washington crowd. What’s more, some scholars say the compact could be vulnerable to legal challenge, especially if a national emergency were declared.

A political knockdown would pit the Midwest vs. Westerners accustomed to no-holds-barred combat for water (to the death in the Wild West) and who have tended, when all else failed, to get what they wanted by simply taking it (for example, the lands of indigenous tribes).

The West sees some things in its favor, politically. One is mushrooming population that’s tipping the power balance in Congress. Another is the always-powerful agriculture industry in the West. And still another is that Western states stick together like fired clay to leverage their will over all things land and water. Besides, they’ll argue, water is a resource that, like oil, must be shared.

And so, a prediction: Within the lifetime of today’s newborn, Great Lakes water will be piped to the Colorado basin to relieve a region that by midcentury will be in the throes of an unimaginable water crisis.

This notion was advocated last year by NASA’s chief water scientist at California’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, who added that national water shortages are more serious than most realize — and may be unsolvable.

On several levels, it’s frankly absurd to pipe water across the country to bail out overbuilt cities and nourish water-intensive crops in bone-bleaching desert. But growth-driven Westerners dismiss such talk. This war would come down to raw power politics, and it’s only a matter of time before the West’s political influence prevails.

Consider: Less than 80 years ago, North Dakota had more electoral votes than Arizona, and Phoenix was a remote outpost. Today, Arizona has more people than North Dakota, South Dakota and Minnesota combined. That kind of growth is evident throughout the Southwest, which means more and more members of Congress are being sent by dry states rather than by the water-rich Midwest.

It’s not realistic to think that pioneers more than a century ago could have foreseen today’s mess. Western settlement was blindly driven by Manifest Destiny back then, and land and water were both considered limitless.

Today, the West’s chief water user is agriculture, with three-fourths consumed by water-gulping crops like cotton, citrus, alfalfa and vegetables. Irrigated fields around hot, dry Yuma, Ariz., produce so many winter vegetables that nearly all of your salad comes from Yuma. Irrigated fields grow countless tons of alfalfa to feed livestock, crowded into giant feedlots nearby.

So much water is sucked from the Colorado to grow crops and quench thirsts that the river’s flow into Mexico is a relative trickle.

The Southwest’s water crisis is a result of dubious policy that pushed unsustainable growth, incented by federally financed dams, reservoirs and canals that delivered water at astonishingly low cost to cities and farmers.

Requirements that states and users repay the cost of building waterworks are often waived with little notice. Just one of these giant projects, the 336-mile concrete canal moving Colorado River water to Phoenix and Tucson, cost $4 billion to build in the 1970s ($26 billion today) and many millions to maintain. Relatively little has been repaid to taxpayers, or ever will be.

Another problem is that governments allocated Colorado River water based on 1920s projections, when river flows were abnormally high. When more reliable tree-ring analyses later exposed major distortions in projections, the West went into collective denial and did little to rein in explosive growth.

So, why should Great Lakes water be shipped to a desert where unrestrained growth continues? It shouldn’t be, but debating this one will get you into a sticky wicket of the outsized influence of infrastructure (water works, roads, bridges, wetland drainage, etc.) in too often enabling inefficient and harmful growth. Genuflection to development has skewed urban and rural planning since long before the country’s founding.

Diverting water west would require a 900-mile pipeline from Duluth to, most likely, Green River, Wyo. There, the river flows south into Utah and joins the Colorado near Moab.

It would be a colossal technical and financial undertaking.

Lifting, say, 50 billion gallons of water from Duluth by 5,500 vertical feet over the Continental Divide to Green River would consume the power of several hundred plants the size of Xcel Energy’s nuclear generator at Monticello.

The power sources would cost tens of billions to build and operate, on top of which would be billions more to install and maintain the pipeline.

And while 50 billion gallons sounds like a lot of water, it would take 10 times that amount to dent the Southwest drought.

These are dizzying numbers, but it’s a straightforward bargain plan compared with capturing and moving water south from Alaska.

Either way, taxpayers would surely get stuck with the tab — as the West keeps building cities and growing crops in bone-dry desert.

(source: Star Tribune)

#great lakes#lake superior#lake michigan#lake huron#lake erie#lake ontario#news#this is more of a commentary i guess#also great lakes water is great lakes water#sorry not sorry#environment

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Japan Races to Build New Coal-Burning Power Plants, Despite the Climate Risks

Just beyond the windows of Satsuki Kanno’s apartment overlooking Tokyo Bay, a behemoth from a bygone era will soon rise: a coal-burning power plant, part of a buildup of coal power that is unheard-of for an advanced economy.

It is one unintended consequence of the Fukushima nuclear disaster almost a decade ago, which forced Japan to all but close its nuclear power program. Japan now plans to build as many as 22 new coal-burning power plants — one of the dirtiest sources of electricity — at 17 different sites in the next five years, just at a time when the world needs to slash carbon dioxide emissions to fight global warming.

“Why coal, why now?” said Ms. Kanno, a homemaker in Yokosuka, the site for two of the coal-burning units that will be built just several hundred feet from her home. “It’s the worst possible thing they could build.”

Together the 22 power plants would emit almost as much carbon dioxide annually as all the passenger cars sold each year in the United States. The construction stands in contrast with Japan’s effort to portray this summer’s Olympic Games in Tokyo as one of the greenest ever.

The Yokosuka project has prompted unusual pushback in Japan, where environmental groups more typically focus their objections on nuclear power. But some local residents are suing the government over its approval of the new coal-burning plant in what supporters hope will jump-start opposition to coal in Japan.

The Japanese government, the plaintiffs say, rubber-stamped the project without a proper environmental assessment. The complaint is noteworthy because it argues that the plant will not only degrade local air quality, but will also endanger communities by contributing to climate change.

Carbon dioxide released into the atmosphere is the major driver of global warming, because it traps the sun’s heat. Coal burning is one of the biggest single sources of carbon dioxide emissions.

Japan has used the Olympics to underscore its transition to a more climate-resilient economy, showing off innovations like roads that reflect heat. Organizers have said electricity for the Games will come from renewable sources.

Coal investments threaten to undermine that message.

Under the Paris accord, Japan committed to rein in its greenhouse gas emissions by 26 percent by 2030 compared to 2013 levels, a target that has been criticized for being “highly inefficient” by climate groups.

“Japan touts a low-emissions Olympics, but in the very same year, it will start operating five new coal-fired power plants that will emit many times more carbon dioxide than anything the Olympics can offset,” said Kimiko Hirata, international director at the Kiko Network, a group that advocates climate action.

Japan’s policy sets it apart from other developed economies. Britain, the birthplace of the industrial revolution, is set to phase out coal power by 2025, and France has said it will shut down its coal power plants even earlier, by 2022. In the United States, utilities are rapidly retiring coal power and no new plants are actively under development.

But Japan relies on coal for more than a third of its power generation needs. And while older coal plants will start retiring, eventually reducing overall coal dependency, the country still expects to meet more than a quarter of its electricity needs from coal in 2030.

“Japan is an anomaly among developed economies,” said Yukari Takamura, an expert in climate policy at the Institute for Future Initiatives at the University of Tokyo. “The era of coal is ending, but for Japan, it’s proving very difficult to give up an energy source that it has relied on for so long.”

Japan’s appetite for coal doesn’t solely come down to Fukushima. Coal consumption has been rising for decades, as the energy-poor country, which is reliant on imports for the bulk of its energy needs, raced to wean itself from foreign oil following the oil shocks of the 1970s.

Fukushima, though, presented another type of energy crisis, and more reason to keep investing in coal. And even as the economics of coal have started to crumble — research has shown that as soon as 2025 it could become more cost-effective for Japanese operators to invest in renewable energy, such as wind or solar, than to run coal plants — the government has stood by the belief that the country’s utilities must keep investing in fossil fuels to maintain a diversified mix of energy sources.

Together with natural gas and oil, fossil fuels account for about four-fifths of Japan’s electricity needs, while renewable sources of energy, led by hydropower, make up about 16 percent. Reliance on nuclear energy, which once provided up to a third of Japan’s power generation, plummeted to 3 percent in 2017.

The Japanese government’s policy of financing coal power in developing nations, alongside China and South Korea, has also come under scrutiny. The country is second only to China in the financing of coal plants overseas.

At the United Nations climate talks late last year in Madrid, attended by a sizable Japanese contingent, activists in yellow “Pikachu” outfits unfurled “No Coal” signs and chanted “Sayonara coal!”

A target of the activists’ wrath has been Japan’s new environment minister, Shinjiro Koizumi, a charismatic son of a former prime minister who is seen as a possible future candidate for prime minister himself. But Mr. Koizumi has fallen short of his predecessor, Yoshiaki Harada, who had declared that the Environment Ministry would not approve the construction of any more new large coal-fired power plants, but lasted less than a year as minister.

Mr. Koizumi has shied away from such explicit promises in favor of more general assurances that Japan will eventually roll back coal use. “While we can’t declare an exit from coal straight away,” Mr. Koizumi said at a briefing in Tokyo last month, the nation “had made it clear that it will move steadily toward making renewables its main source of energy.”

The Yokosuka project has special significance for Mr. Koizumi, who hails from the port city, an industrial hub and the site of an American naval base. The coal units are planned at the site of an oil-powered power station, operated by Tokyo Electric Power, that shuttered in 2009, to the relief of local residents.

But that shutdown proved to be short-lived.

Just two years later, the Fukushima disaster struck, when an earthquake and tsunami badly damaged a seaside nuclear facility also owned by Tokyo Electric. The resulting meltdown sent the utility racing to start up two of the eight Yokosuka oil-powered units as an emergency measure. They were finally shut down only in 2017.

What Tokyo Electric proposed next — the two new coal-powered units — has left many in the community bewildered. To make matters worse, Tokyo Electric declared that the units did not need a full environmental review, because they were being built on the same site as the oil-burning facilities.

The central government agreed. The residents’ lawsuit challenges that decision.

Some new coal projects have faced hiccups. Last year, a consortium of energy companies canceled plans for two coal-burning plants, saying they were no longer economical. Meanwhile, Japan has said it will invest in carbon capture and storage technology to clean up emissions from coal generation, but that technology is not yet commercially available.

Coal’s fate in Japan may reside with the country’s Ministry of Trade, which pulls considerable weight in Tokyo’s halls of power. In a response to questions about the coal-plant construction, the ministry said it had issued guidance to the nation’s operators to wind down their least-efficient coal plants and to aim for carbon-emissions reductions overall. But the decision on whether to go ahead with plans rested with the operators, it said.

“The most responsible policy,” the ministry said, “is to forge a concrete path that allows for both energy security, and a battle against climate change.”

Local residents say the ministry’s position falls short. Tetsuya Komatsubara, 77, has operated a pair of small fishing boats out of Yokosuka for six decades, diving for giant clams, once abundant in waters off Tokyo.

Scientists have registered a rise in the temperature of waters off Tokyo of more than 1 degree Celsius over the past decade, which is wreaking havoc with fish stocks there.

Mr. Komatsubara can feel the rise in water temperatures on his skin, he said, and was worried the new plants would be another blow to a fishing business already on the decline. “They say temperatures are rising. We’ve known that for a long time,” Mr. Komatsubara said. “It’s time to do something about that.”

For more climate news sign up for the Climate Fwd: newsletter or follow @NYTClimate on Twitter.

from WordPress https://mastcomm.com/japan-races-to-build-new-coal-burning-power-plants-despite-the-climate-risks/

0 notes

Link

Renewable energy is hot. It has incredible momentum, not only in terms of deployment and costs but in terms of public opinion and cultural cachet. To put it simply: Everyone loves renewable energy. It’s cleaner, it’s high-tech, it’s new jobs, it’s the future.

And so more and more big energy customers are demanding the full meal deal: 100 percent renewable energy.

The Sierra Club notes that so far in the US, more than 80 cities, five counties, and two states have committed to 100 percent renewables. Six cities have already hit the target.

The group RE100 tracks 144 private companies across the globe that have committed to 100 percent renewables, including Google, Ikea, Apple, Facebook, Microsoft, Coca-Cola, Nike, GM, and, uh, Lego.

The timing of all these targets (and thus their stringency) varies, everywhere from 2020 to 2050, but cumulatively, they are beginning to add up. Even if policymakers never force power utilities to produce renewable energy through mandates, if all the biggest customers demand it, utilities will be mandated to produce it in all but name.

The rapid spread and evident popularity of the 100 percent target has created an alarming situation for power utilities. Suffice to say, while there are some visionary utilities in the country, as an industry, they tend to be extremely small-c conservative.

They do not like the idea of being forced to transition entirely to renewable energy, certainly not in the next 10 to 15 years. For one thing, most of them don’t believe the technology exists to make 100 percent work reliably; they believe that even with lots of storage, variable renewables will need to be balanced out by “dispatchable” power plants like natural gas. For another thing, getting to 100 percent quickly would mean lots of “stranded assets,” i.e., shutting down profitable fossil fuel power plants.

LightRocket via Getty Images

In short, their customers are stampeding in a direction that terrifies them.

The industry’s dilemma is brought home by a recent bit of market research and polling done on behalf of the Edison Electric Institute, a trade group for utilities. It was distributed at a recent meeting of EEI board members and executives and shared with me.

The work was done by the market research firm Maslansky & Partners, which analyzed existing utility messaging, interviewed utility execs and environmentalists, ran a national opinion survey, and did a couple of three-hour sit-downs with “media informed customers” in Minneapolis and Phoenix.

The results are striking. They do a great job of laying out the public opinion landscape on renewables, showing where different groups have advantages and disadvantages.

The takeaway: Renewables are a public opinion juggernaut. Being against them is no longer an option. The industry’s best and only hope is to slow down the stampede a bit (and that’s what they plan to try).

The core of the industry’s dilemma is captured in this slide (on the left is the industry perspective):

EEI

Utilities don’t think it is wise or feasible to go 100 percent renewables. But the public loves it.

And I mean loves it. Check out these numbers from the opinion survey:

In our polarized age, here is something we almost all agree on: Renewable energy is awesome.

Here’s the most striking slide in the presentation:

EEI

In case you don’t feel like squinting, let me draw your attention to the fact that a majority of those surveyed (51 percent) believe that 100 percent renewables is a good idea even if it raises their energy bills by 30 percent.

That is wild. As anyone who’s been in politics a while knows, Americans don’t generally like people raising their bills, much less by a third. A majority that still favors it? That is political dynamite.

Insofar as utilities were in a public relations war over renewables, they’ve lost. They face a tidal wave. So what can they do?

What they can’t do is tell customers why they can’t do it. Customers do not want to hear excuses.

They tested the following message (this is an excerpt, with emphasis added): “Today, we can choose between a balanced energy mix, which provides reliable energy whenever we need it, and 100% renewable energy. But we cannot have both. We also need to consider the costs. … The logistics, resources, and costs would be immense.”

Nope. Customers didn’t want to hear it.

“You could tell what side he was leaning toward,” said one Phoenix focus-group participant. “He offered no solutions. It was just problem, problem, problem.”

“I want to hear about how the work would get done,” said a Minneapolis participant. “I don’t want to hear him complain about how much work it will take.”

Other can’t-do arguments drew similar reactions:

EEI

Can’t-do arguments get a company branded as anti-renewables, and that means Bad Guy. After that, customers aren’t listening.

If they want people to keep listening, utilities must begin by convincing them that they are on board with renewables. Thus, the very first piece of advice on “framing the conversation” reads, “Positive, pro-renewable message first … every time.”

An anti-renewables message, even a message that implies anti-renewables, is simply untenable.

That is worth noting. It’s something I’m not sure US climate hawks or political types have entirely internalized. There aren’t many contested political issues on which public opinion is so unequivocally on one side.

So utilities must convince customers that they support renewable energy, first thing, off the bat. (The best way to do that, of the options tested, was telling customers about investments — highlighting the rising level of investment in renewables. Money talks.)

If they can make that key connection, then they can swing the conversation around. Once customers are convinced that utilities are sincere about supporting renewables, they become more open to the message that getting to 100 percent will take some time, that it needs to be done deliberately, and that costs need to be taken into account.

“Given the cost and the complexities of it, it should be done gradually,” one Phoenix respondent said. “Not the next five years, but maybe by the end of our lifetimes,” said another.

The researchers tested the following message (excerpted): “[A balanced energy mix] helps us maintain consistent service for our customers and avoids over-reliance on a single fuel type or technology. This means we’re able to bring our customers increasingly more renewable energy without asking them to compromise on reliability or cost.”

That worked much better. “It seemed like we all have the same goal that we’re working toward,” said a respondent in Minneapolis. “In the meantime, they’ll use a balance to serve us. It’s sensible.”

In fact, in terms of reasons not to rely entirely on renewables, by far the most potent argument was that it would slow the transition to clean energy: “We can get to cleaner energy faster and more effectively if we use a range of sources and technologies.”

The state-of-the-art message for utilities, then, is this: Yes, we want to pursue renewables, but to protect consumers, we want to do it in a way that is “balanced, gradual, affordable, [and] reliable.” That means we should avoid, ahem, “short-term mandates.”

EEI

(How much this message will merely cover for efforts to block legislation and slow the transition depends on the utility.)

So where does this leave us in terms of the messaging landscape?

In the 100 percent renewables debate, there are roughly three camps, at least among the researchers, energy executives, climate advocates, and journalists who pay attention to these sorts of things.

The first, with most activists and advocates, supports 100 percent renewables as a clear, intuitive, and inspiring target, an effective way to rally public support and speed the transition.

The second camp believes that the cheaper, safer way to get to carbon-free electricity is not to rely entirely on renewables but to supplement them with “firm” zero-carbon alternatives like hydro, nuclear, geothermal, biomass, or fossil fuels with carbon capture and sequestration. (See this paper, from a group of MIT researchers, for the best articulation of that argument.) This camp supports the strategy California has taken, which is to mandate 100 percent “zero carbon” rather than “renewable” resources, to leave flexibility.

The third camp, containing many utilities and conservatives, flatly doesn’t believe 100 percent carbon-free electricity is possible anytime soon, and would just as soon not close working fossil fuel power plants before the end of their profitable lives. They would like to continue balancing the rising share of renewables with natural gas.

The first camp has won the public’s heart. Big time. Everyone, even those gritting their teeth, has to signal support for renewables if they want to be taken seriously.

There is some room for the third camp to convince the public that the transition to renewables needs to proceed carefully and “gradually.” That’s the ground advocates and utilities will be fighting on in coming years: not whether to go, but how fast. (There’s a lot of room within “not the next five years, but maybe by the end of our lifetimes.”)

Get used to it. Shutterstock

And there is some room for the second camp to convince the public that the transition to clean energy is best achieved by relying on sources beyond renewable energy, or at least by not locking ourselves into renewables prematurely. One of the survey’s findings is that under a range of questions, the public does not have a strong preference between increasing renewables and reducing carbon emissions. I doubt most people differentiate the two at all — they are vaguely good, environmental-ish things.

Similarly, I doubt the public at large will care much about the distinction between “renewable” and “clean,” which serves as a pretty good argument for the California approach. (The California approach, or at least earlier variants of it, has helped keep existing nuclear plants running in Illinois and New York.)

But these are implementation details. The decarbonization ship has sailed. Renewable energy is in the vanguard and, at least for now, it appears unstoppable. At this point, it is difficult to imagine what could turn the public against it. (Perhaps a giant wind spill?) The more relevant question is when lawmakers will catch on to renewable energy’s full political potential.

The basic message from the public, if I could pull together all the strands of the research, is this: We want clean, modern energy, and we’ll pay for it. We’re willing to let experts work out the details, but we don’t want to hear that it can’t be done. Just do it.

Utilities can’t make that sentiment go away, though they can and will try to soften it. In the meantime, in the off-chance that their messaging efforts fail, they’d better get serious about giving customers the clean energy they want.

Original Source -> Utilities have a problem: the public wants 100 percent renewable energy, and quick

via The Conservative Brief

0 notes

Text

Study: Adding power choices reduces cost and risk of carbon-free electricity

In major legislation passed at the end of August, California committed to creating a 100 percent carbon-free electricity grid — once again leading other nations, states, and cities in setting aggressive policies for slashing greenhouse gas emissions. Now, a study by MIT researchers provides guidelines for cost-effective and reliable ways to build such a zero-carbon electricity system.

The best way to tackle emissions from electricity, the study finds, is to use the most inclusive mix of low-carbon electricity sources.

Costs have declined rapidly for wind power, solar power, and energy storage batteries in recent years, leading some researchers, politicians, and advocates to suggest that these sources alone can power a carbon-free grid. But the new study finds that across a wide range of scenarios and locations, pairing these sources with steady carbon-free resources that can be counted on to meet demand in all seasons and over long periods — such as nuclear, geothermal, bioenergy, and natural gas with carbon capture — is a less costly and lower-risk route to a carbon-free grid.

The new findings are described in a paper published today in the journal Joule, by MIT doctoral student Nestor Sepulveda, Jesse Jenkins PhD ’18, Fernando de Sisternes PhD ’14, and professor of nuclear science and engineering and Associate Provost Richard Lester.

The need for cost effectiveness

“In this paper, we’re looking for robust strategies to get us to a zero-carbon electricity supply, which is the linchpin in overall efforts to mitigate climate change risk across the economy,” Jenkins says. To achieve that, “we need not only to get to zero emissions in the electricity sector, but we also have to do so at a low enough cost that electricity is an attractive substitute for oil, natural gas, and coal in the transportation, heat, and industrial sectors, where decarbonization is typically even more challenging than in electricity. ”

Sepulveda also emphasizes the importance of cost-effective paths to carbon-free electricity, adding that in today’s world, “we have so many problems, and climate change is a very complex and important one, but not the only one. So every extra dollar we spend addressing climate change is also another dollar we can’t use to tackle other pressing societal problems, such as eliminating poverty or disease.” Thus, it’s important for research not only to identify technically achievable options to decarbonize electricity, but also to find ways to achieve carbon reductions at the most reasonable possible cost.

To evaluate the costs of different strategies for deep decarbonization of electricity generation, the team looked at nearly 1,000 different scenarios involving different assumptions about the availability and cost of low-carbon technologies, geographical variations in the availability of renewable resources, and different policies on their use.

Regarding the policies, the team compared two different approaches. The “restrictive” approach permitted only the use of solar and wind generation plus battery storage, augmented by measures to reduce and shift the timing of demand for electricity, as well as long-distance transmission lines to help smooth out local and regional variations. The “inclusive” approach used all of those technologies but also permitted the option of using continual carbon-free sources, such as nuclear power, bioenergy, and natural gas with a system for capturing and storing carbon emissions. Under every case the team studied, the broader mix of sources was found to be more affordable.

The cost savings of the more inclusive approach relative to the more restricted case were substantial. Including continual, or “firm,” low-carbon resources in a zero-carbon resource mix lowered costs anywhere from 10 percent to as much as 62 percent, across the many scenarios analyzed. That’s important to know, the authors stress, because in many cases existing and proposed regulations and economic incentives favor, or even mandate, a more restricted range of energy resources.

“The results of this research challenge what has become conventional wisdom on both sides of the climate change debate,” Lester says. “Contrary to fears that effective climate mitigation efforts will be cripplingly expensive, our work shows that even deep decarbonization of the electric power sector is achievable at relatively modest additional cost. But contrary to beliefs that carbon-free electricity can be generated easily and cheaply with wind, solar energy, and storage batteries alone, our analysis makes clear that the societal cost of achieving deep decarbonization that way will likely be far more expensive than is necessary.”

A new taxonomy for electricity sources

In looking at options for new power generation in different scenarios, the team found that the traditional way of describing different types of power sources in the electrical industry — “baseload,” “load following,” and “peaking” resources — is outdated and no longer useful, given the way new resources are being used.

Rather, they suggest, it’s more appropriate to think of power sources in three new categories: “fuel-saving” resources, which include solar, wind and run-of-the-river (that is, without dams) hydropower; “fast-burst” resources, providing rapid but short-duration responses to fluctuations in electricity demand and supply, including battery storage and technologies and pricing strategies to enhance the responsiveness of demand; and “firm” resources, such as nuclear, hydro with large reservoirs, biogas, and geothermal.

“Because we can’t know with certainty the future cost and availability of many of these resources,” Sepulveda notes, “the cases studied covered a wide range of possibilities, in order to make the overall conclusions of the study robust across that range of uncertainties.”

Range of scenarios

The group used a range of projections, made by agencies such as the National Renewable Energy Laboratory, as to the expected costs of different power sources over the coming decades, including costs similar to today’s and anticipated cost reductions as new or improved systems are developed and brought online. For each technology, the researchers chose a projected mid-range cost, along with a low-end and high-end cost estimate, and then studied many combinations of these possible future costs.

Under every scenario, cases that were restricted to using fuel-saving and fast-burst technologies had a higher overall cost of electricity than cases using firm low-carbon sources as well, “even with the most optimistic set of assumptions about future cost reductions,” Sepulveda says.

That’s true, Jenkins adds, “even when we assume, for example, that nuclear remains as expensive as it is today, and wind and solar and batteries get much cheaper.”

The authors also found that across all of the wind-solar-batteries-only cases, the cost of electricity rises rapidly as systems move toward zero emissions, but when firm power sources are also available, electricity costs increase much more gradually as emissions decline to zero.

“If we decide to pursue decarbonization primarily with wind, solar, and batteries,” Jenkins says, “we are effectively ‘going all in’ and betting the planet on achieving very low costs for all of these resources,” as well as the ability to build out continental-scale high-voltage transmission lines and to induce much more flexible electricity demand.

In contrast, “an electricity system that uses firm low-carbon resources together with solar, wind, and storage can achieve zero emissions with only modest increases in cost even under pessimistic assumptions about how cheap these carbon-free resources become or our ability to unlock flexible demand or expand the grid,” says Jenkins. This shows how the addition of firm low-carbon resources “is an effective hedging strategy that reduces both the cost and risk” for fully decarbonizing power systems, he says.

Even though a fully carbon-free electricity supply is years away in most regions, it is important to do this analysis today, Sepulveda says, because decisions made now about power plant construction, research investments, or climate policies have impacts that can last for decades.

“If we don’t start now” in developing and deploying the widest range of carbon-free alternatives, he says, “that could substantially reduce the likelihood of getting to zero emissions.”

David Victor, a professor of international relations at the University of California at San Diego, who was not involved in this study, says, “After decades of ignoring the problem of climate change, finally policymakers are grappling with how they might make deep cuts in emissions. This new paper in Joule shows that deep decarbonization must include a big role for reliable, firm sources of electric power. The study, one of the few rigorous numerical analyses of how the grid might actually operate with low-emission technologies, offers some sobering news for policymakers who think they can decarbonize the economy with wind and solar alone.”

The research received support from the MIT Energy Initiative, the Martin Family Trust, and the Chilean Navy.

Study: Adding power choices reduces cost and risk of carbon-free electricity syndicated from https://osmowaterfilters.blogspot.com/

0 notes

Text

With sharp words and stealth strikes, Israel sends a message to Hezbollah and U.S.

By Loveday Morris and Louisa Loveluck, Washington Post, September 21, 2017

JERUSALEM--Israel has flexed its military muscles in recent months as the regional balance of power has pitched further in favor of its most bitter adversaries: Iran and its Lebanese proxy Hezbollah.

Analysts and former senior Israeli military officers say Israel is showing that it will act with force to protect its interests, while using just enough of it to limit its enemies without sparking a war. But it’s a precarious line to tread, and even a small misstep could lead to conflict, they say.

Israel is scrambling to adjust as Syrian President Bashar al-Assad has taken the upper hand in his country’s six-year war, propped up by an emboldened Iran and an array of Shiite militias, including Hezbollah, which has sent thousands of fighters to back him.

The Israeli government had expressed frustration as the Trump administration focused on fighting Islamic State militants without, in Israel’s opinion, sufficiently limiting Iran and its proxies. Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu publicly criticized a U.S.-Russia cease-fire deal in southern Syria for not including provisions to stop Iranian expansion.

Israel is now making itself heard. Last week Israeli jets buzzed so low over southern Lebanon that they shattered windows and caused panic. That followed the bombing of a military site in Syria earlier in the month that had been linked to missile production for Hezbollah.

On Tuesday, the army used a Patriot missile to shoot down a drone that neared its airspace.

Threats have escalated on both sides. “If the Zionist regime makes any wrong move, Haifa and Tel Aviv will be razed,” Iran’s army chief Maj. Gen. Abdolrahim Mousavi warned this week in comments published by Fars news agency, referring to Israeli cities within the range of Hezbollah rockets.

Hezbollah and Israel fought a month-long war in 2006 that caused heavy casualties, and both sides claimed victory. Since then, the Syrian war has provided Hezbollah fighters with a training opportunity, while Israel estimates that it has built up a stockpile of more than 100,000 rockets.

Israel fears Iran will help Hezbollah upgrade to more accurate precision-guided missiles and establish a permanent military presence in Syria, from where they could eventually turn their focus south.

“Generally speaking, this is the kind of threat we can’t live with,” said Brig. Gen. Nitzan Nuriel, a former Israeli Defense Forces officer who was deputy commander of the division responsible for the Lebanese front during the 2006 war. “This is the kind of threat we need to deal with.”

In recent months, Netanyahu has accused Iran of establishing long-range missile-manufacturing sites in both Lebanon and Syria. Satellite images showing one alleged site, near the port city of Baniyas, were shared with the press.

Israel is keen to leverage more favorable outcomes in Syrian cease-fire deals where it feels its interests have been ignored, and public threats and messages are meant as much for Israel’s allies as its enemies, Nuriel said.

In a speech last month, Hezbollah Secretary General Hasan Nasrallah mocked Netanyahu for “crying” over the defeat of Islamic State in Iraq and Syria.

Nasrallah has repeatedly warned Israel against attacking Lebanon.

“If the Israelis think they can now make war in Lebanon, then they are making a big mistake. In Syria we have learned to attack,” said a senior official from the military alliance of Hezbollah, Syria and Iran. He spoke on the condition of anonymity because he is not authorized to speak with the press.

“The rhetoric on both sides is a substitute for action--a way of reinforcing deterrence without having to take military action--and a way of saving face,” said Faysal Itani, a fellow at the Washington-based Atlantic Council. “But I do think things are trending negatively.”

Netanyahu tried to drive his point home at the U.N. General Assembly in New York on Tuesday, saying that “those who threaten us with annihilation put themselves in mortal peril.” Israel will act to prevent Iran from opening “new terror fronts” on Israel’s northern border, he said.

He also pushed for changes to the international deal limiting Iran’s nuclear activities.

“This is all classic Netanyahu,” said Ofer Zalzberg, a senior analyst at International Crisis Group. “Saying ‘hold me back before I do something,’ but I don’t see Israel launching a preemptive war. The next war between Israel and Hezbollah will be dramatic for Israel’s population and will have consequences for whoever is in power.”

But the prospect is not impossible; there are some Israeli officials advocating intervention, he said, describing Israel as “panicked.” “Advocates are saying bomb now.”

They see a window of opportunity. While Syria has restrained from retaliating against Israeli strikes on its soil, that is likely to change as the war draws to an end, raising the stakes of the occasional intervention with airstrikes that Israel is currently engaged in.

In Lebanon, Hezbollah’s growing strength has come at a cost, one that could cause personnel problems in the event of renewed conflict.

The group does not publish figures for the number of their members who have fought and died in Syria, but more than 1,000 have been killed according to one study of Arabic language press coverage of funerals in Lebanon.

On a recent day in the Beirut suburb of Dahiyeh, a steady trickle of relatives passed through a newly opened cemetery for fighters recently killed in Syria. Marble slabs are adorned with photographs of the men in fatigues, some decorated with roses for Father’s Day.

Sitting quietly at the gravestone of a commander killed last year, a woman named Rukiya said her son died in the battle to recapture the northern city of Aleppo. “He knew he didn’t have to go, but he didn’t listen to me,” she said. “The resistance was everything to him.”

In April, Hezbollah organized a rare press trip to the border area to highlight what appeared to be newly constructed fortifications on the Israeli side of the U.N.-patrolled buffer zone between the two countries.

Israel’s Defense Ministry confirmed that it was indeed bolstering its defenses, including walls near Israel’s northern communities that are vulnerable to cross-border sniper fire or antitank missiles, Israeli media reported. It also said the project will cost some $34.7 million.

“We are strengthening the border based on the understanding that in any future conflict, Hezbollah would make a concerted effort to cross the border,” said an Israeli Defense Forces official in the Northern Command who spoke on the condition of anonymity because he was not authorized to speak publicly.

In the meantime, Israel will continue its strategy of “deterrence and prevention,” Nuriel said, managing the risks of escalation.

“You need to ask yourself, if you do this, what will the enemy do?�� he said. “Many times we decide taking action is better.”

But Israel’s 2006 war with Hezbollah began when militants launched a cross-border raid on an Israeli patrol, killing three Israeli soldiers and abducting two. Nasrallah later said that if he’d known how Israel would react, Hezbollah would not have carried out the raid. The war left 1,000 Lebanese and nearly 160 Israelis dead. Now the stakes are higher.

“Syria made the machine faster,” said Kamal Wazne, a professor at the American University of Beirut who studies the group. “A confrontation is going to be deadly, destructive and painful for both sides.”

0 notes