#it’s so compelling to have both Orpheus and Eurydice be artists but only Orpheus getting the fame

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

“Orpheus doesn’t love Eurydice he’s obsessed with her and worships her!” Yeah the show does a pretty bad job at showing that, at worst he just made songs for her and asked her to be on his album cover (which she had the choice to refuse), isn’t that literally any woman’s dream relationship? Isn’t that how all artists express their love for their partner? Why is it portrayed as a bad thing while Eurydice and Caeneus’s bland rushed relationship is portrayed as good? Why is our idea of this myth from Eurydice’s perspective mean that she secretly doesn’t love him? Why couldn’t she still love him but have issues like in Supergiant’s Hades?

#also why isn’t Kaos Eurydiv]ce not an artist herself? does she sulk all day with her mommy issues?#another point in Hades! Eurydice’s favor#it’s so compelling to have both Orpheus and Eurydice be artists but only Orpheus getting the fame#how does a video game have a better interpretation than this show?#greek mythology#ancient greek mythology#greek pantheon#Orpheus and Eurydice#orpheus#Eurydice#Kaos#Kaos Netflix#eurydice kaos#Caeneus

67 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hadestown

First off Hadestown was phenomenal. I legit almost cried at the end; even though I knew there wouldn’t be a happy ending, the musical did such a good job of creating and then destroying hope for the characters. It was probably the most religious experience I’ve ever had doing laundry, so props to that.

All of the songs were bangers, and the casting of the voices was really well done. Orpheus makes sense as a pretty boy with a gorgeous falsetto, Persephone sounds world-weary but has the capacity to harken back to a time of youth and innocence, and Hades sounds menacing without totally getting lost in the maniacal villain thing (except for the part where he yelled about the electric chorus that was a little much).

I love how this version made explicit the parallels between Hades/Persephone and Orpheus/Eurydice, and also how this version gave both women way more depth. This not only fleshes the story out and makes it feel a lot less misogynistic, it also just makes the story better. In the original story, Orpheus was just a stupid musical fuckboy who couldn’t follow orders for more than two minutes. Whereas in this version, while I was still like “why would you look around?” his doubt makes so much more sense. She left him once before, and so its natural and human for him to doubt her loyalty now.

At the same time, Orpheus turning around is extra tragic for Eurydice, who left him because of his inability to provide for her. We get the impression that Eurydice, who was doing all of the hard work, felt neglected materially but also emotionally — he was more focused on music than her. By coming to save her, he proves his love, but his inability to do the hard thing and not look back proves that he hasn’t really matured. The same impulse that led him to neglect food and shelter for his music also preventing him from following Hades’ instructions. So really they couldn’t be together, even if Eurydice had escaped — nothing had changed, they were caught in a cycle.

That cyclic feeling to this story is obviously thematically in conversion with Hades and Persephone, which is so cool and deepens the story. It also redeems the musical as a musical. From experience, it’s hard to practice and perform a musical over and over again if there is no sense of redemption at all, and if you don’t fundamentally enjoy the story, the characters, and the themes. The closing song, with Hermes talking about how it’s the same song, and we sing it over and over again, hoping it’ll change even though we know it won’t, is conversation not just with the nature of myth and storytelling, but also the nature of performance.

Myth and stories are told over and over again, and what Hadestown does it what all good retelling of myth do — they make the same story feel alive and vital again. I knew there wouldn’t be a happy ending, but I felt the tragedy as is if it could have ended another way. That ability to imagine what could have been is, according to Hermes, Orpheus’ true gift. Orpheus is generally just a metaphor for all artists, so it’s kind of also a statement about all art.

What makes this link compelling is the fact that, for the performers in the musical, the have to literally tell this story over and over again, and in order to make each performance good that have to basically trick themselves into thinking it could end differently. That’s just what performing is, being able to replay these emotional beats over and over again and keep them fresh. So Hermes, who addresses the audience and is a really cool meta-textual character (which is stylistically very resonant with the way that ancient Greek poems started with 4th wall breaking invocations to the muses), is also making a commentary about the play itself. The fact that this is a performance is called out, but rather than weakening the story is strengthens it — it calls attention to how this story is an eternal loop of hope and pain, just like the seasons are eternal. So it explains the purpose of the musical in the same way these myths were explained in the past — they both do explanatory work about the world, and the cyclic nature of the seasons, and of love and loss. It’s just more abstract than literal explanatory work (which is probably more accurate to the ancient view of myth, honestly, than an overly literal one).

Hadestown also does what ancient myths did, which is reify abstract concepts in a way that makes reasoning about these concepts easier. Hadestown plays up Hades’ relationship with wealth, and so to me a lot of this reads as an interesting critic of capitalism in the face of environmental destruction. Hades’ constant industrial expansion is destroying his relationship with Persephone, who is emblematic of the natural world. The moments of beauty in this play are all related to nature and the natural — most poignantly, the description of Hades coming to the Persephone in “her mother’s garden,” and sleeping with her (which is an incredible finesse, mixing Christian and Greek spirituality pretty flawless and concisely, wow). A parable about success destroying a marriage that started beautifully is a perfect metaphor for the destruction of the planet by human beings that are uniquely situated to enjoy and appreciate its beauty. That’s the kind of thing that myth is excellent at, casting abstract struggles in personal terms that make those abstract struggles real.

Also, the whole wall thing is even more effective today than in 2016, and like makes the whole Hades=capitalism even more interesting and powerful

1 note

·

View note

Photo

THE HI-TOUCH

I like to joke that on February 14, 2020, I met the love of my life.

I didn’t, of course. But for a second, I fumbled my way through a half-high-five-half-handhold with the K-pop boy group Monsta X and absolutely did not cry, no matter what Rolling Stone attempted to imply. (Yes, that’s me in the foreground of the final photograph.)

The hi-touch is an extremely weird event, to say the least.

Anxious because this was the first time I’d ever attended a fan event, I’d managed to show up four hours early. About three of these hours were spent nervously reading Orfeo by Richard Powers at the Coffee Bean down the street, occasionally looking over trying to figure out when people queue up.

The final hour was actually spent in the line. I tried to make small-talk with the fan in front of me, but soon gave that up when she grimaced in disapproval after finding out I’d been a fan for “only a month” then literally took me by the shoulders and shook me while insisting, “MAKE SURE YOU MAKE EYE CONTACT WITH THEM! MAKE EYE CONTACT OR YOU’LL REGRET IT!”

It was while I was worriedly scrolling through my phone that Monsta X rolled in in sports cars.

Just as I began to recover from the absolutely mind-boggling spectacles I’d already been forced to face, I was ushered into the venue--which housed six enormous cut-outs of the members’ faces. Which, frankly, was terrifying.

(Photo: Michelle Kim. Two of the “six enormous cut-outs,” featuring Hyungwon and Joohoney, set-up at Tower Records for Monsta X’s meet-and-greet on Feb. 14, 2020.)

I’d probably been waiting in there for around 15 minutes when the employees desperately trying to hype up the room (mostly full of nervous young girls) introduced Monsta X, who suddenly burst through the curtains on the opposite side of the room and rushed up to the table before hurriedly taking their seats (Kihyun, their main vocalist, barely had time to shrug off his jacket) and sticking out their hands.

After that, it’s just a blur.

Writing this approximately a month after the event, all I can remember is the first member possibly smirking at me, the second holding my hand more firmly than I’d expected, the third smiling broadly, and the last two seeming tired.

And then I stumbled out of the venue and called an Uber and was back home, largely unchanged.

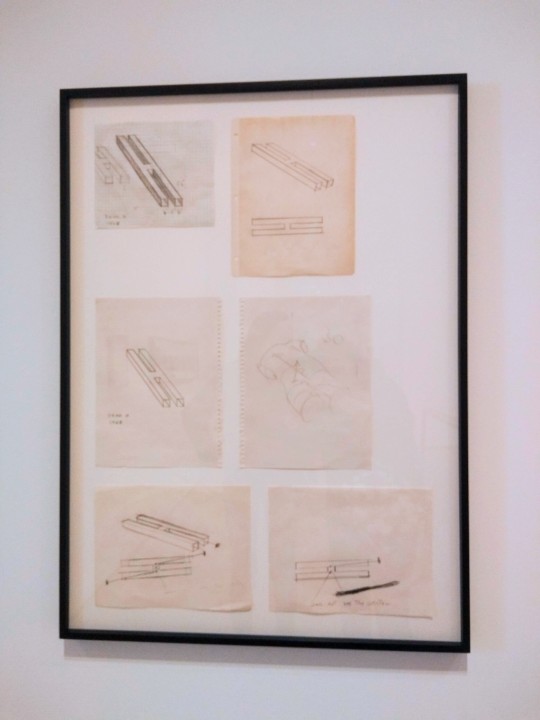

(Photo: Michelle Kim. Paul McCarthy, Dead H Drawings, 1968-69; graphite and ink on paper. Paul McCarthy, Dead H Crooked Leg, 1979 and Dead H Crooked Leg Maze, 1979; graphite and ink on paper. On display at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles, CA. Photo taken Feb. 22, 2020.)

The Gaze

When recalling the original myth of Orpheus and Eurydice, the first thing that usually comes to my mind is Orpheus turning around to look at Eurydice and to lose her. It’s the climax of the story. And though that Orphic gaze is translated differently in different iterations of the myth, it always seems to be a focal point.

Gazing at something implies a strange binary--it reveals that there is that which you can see and that which you cannot. Paul McCarthy captures this in his Dead H Drawings, a series of sketches of said letter with the space in the center horizontal line highlighted. If you were to look through the legs, you would never be able to see the inside of that portion; you could only see out the other end of the leg like a tunnel. Hence, it’s a dead space.

Even when just looking at a specific object, it becomes clear that you can only focus on one thing at a time. Everything in your peripheral is less easily accessed--forget whatever’s happening behind you.

In Orpheus’s case, the gaze is about confirming Eurydice’s presence yet also losing her. It’s both a moment of relief and of grief, of catharsis and of catastrophe. The nature of his tragedy is that he can’t have the first without the second; if he did, he will have succeeded.

For Scottie, the protagonist of Hitchcock’s Vertigo, it’s exactly this sense of conflicted intangibility that attracts him to Judy/Madeleine, the Eurydice-figure. Even when he believes she’s just Madeleine, there’s an element of fantastical unreachability to her--the fact that she is supposedly possessed by Carlotta. And then when Judy falls back into the Madeleine role, Scottie continues to push her to the edge until she dies a true and final death.

Perhaps this is what makes celebrities such easy objects of affection and what motivates paparazzi. Celebrity sightings, celebrity photos, and two-minute interviews--they’re all small glimpses of a desirable person that we wouldn’t otherwise be able to access.

(Screenshots of replies from Twitter on a tweet regarding how the original poster believes BTS loves ARMY more than ARMY could ever love them, taken on March 11, 2020. Twitter handles and personal information have been blurred for the users’ privacy.)

A persistent phenomenon in BTS’s fanbase is ARMY seeming to think that BTS’s members genuinely love all of their fans.

K-pop is particularly adept when it comes to commodifying celebrities. It’s why they’re referred to as “idols” and not just as normal performers. Their jobs are to record songs and dance at concerts, but they’re also expected to vlog, feature on variety and reality shows, film practice videos, take and post selfies, consistently interact with fans on Fancafe (a blog platform for K-pop idols), be gracious and friendly in public--and on top of all this pressure, maintain their appearances and memorize choreography and lyrics.

Because there’s hundreds of hours of content featuring them available, it’s easy for fans to believe that they truly, personally understand their favorite idols. But idols are first and foremost entertainers. Everything they do is in the interest of gaining more fans, who turn into consumers and therefore income. When taking into account their motivation, does that still make idols genuine?

In Sarah Ruhl’s play Eurydice, Eurydice loses her memory upon death. She must relearn who she was when she was alive through her father, also dead, as he reteaches her how to read, her favorite past-time when alive.

By the time Orpheus arrives to guide her out of the Underworld, it’s unclear if Eurydice has regained her previous sense of self. And if she has, it’s been filtered through her father.

Similarly, the return of “Madeleine” in Hitchcock’s Vertigo is a hazy recollection of the original woman.

(Vertigo (1958) dir. Alfred Hitchcock.)

Though Judy is dressed as Madeleine, talks like Madeleine, and walks like Madeleine, she’s only playing the Madeleine that Scottie wants to see. She’s putting on an artificial performance of what he expects in an effort to appease him. The Madeleine that he wants is a cool, refined, and feminine lady. Though not playing hard-to-get, she’s always out of reach as a woman both disconnected from reality and married, therefore unavailable.

Judy can’t always be that. In the car, when Scottie drives her to the bell tower where the true Madeline died, Judy slips through her Madeleine veneer as she acts just a shade too coy.

Eurydice can’t always be what Orpheus expects her to be. The Backwards Look that ultimately causes him to lose her is an act of attempted confirmation, to be sure that he has her: the “loan” that Hades had promised him.

This Backwards Look manifests in many ways among BTS fans.

First, there are the sasaengs and fansites. They’re in some ways comparable to paparazzi--fansites especially, who consider it their (unpaid and unasked for) jobs to photograph idols at their every public appearance, even if they’re just going to catch a flight, then to share their professional-grade photographs online. Sasaengs take this a step further; they’re essentially stalkers who will buy an idol’s personal information to, for example, share a flight and book a neighboring hotel room to be as physically close to them as possible.

Though less extreme, there are also fan artists and fanfiction writers. Both attempt to capture the BTS members’ personalities and internal lives and manifest them in portraits, comics, and elaborate stories (often novel-length or longer). Artists and writers have to assume something about BTS when creating such content. There’s no way anyone could fully understand what’s happening in another person’s head. And when BTS is constantly presenting stage personas while acting like reality shows, filmed by dozens of cameras and producers, represent who they truly are, it’s difficult to say who the artists and writers are trying to capture.

Even a fan’s desire to stream music and videos and look at photos of BTS is a form of the Backwards Look. They’re constantly revisiting a moment and trying to recapture that first instance of experiencing it. This is the Eurydice moment--the experience of falling in love with a piece of art in a brief glance, and losing that feeling as soon as the moment is over.

These experiences are by no means limited to just BTS. Many fandoms, especially other K-pop groups’ fandoms, all experience this overwhelming amount of content consumption. But because BTS is the current Orpheus--dominating their music genre--they have the most fans, the most fanart and fanfiction, and the most streams. They are constantly under the pressure of the Backwards Gaze.

And they are constantly beyond it at the same time. In Ovid’s telling, Eurydice disappears as soon as Orpheus looks back (“she was gone, in a moment”). In Ruhl’s, the lovers “turn away from each other, matter-of-fact, compelled” as soon Orpheus sees Eurydice. When Scottie finally sees the Madeleine he wants, she dies in the next scene.

Eurydice is always beyond reach. And for every minute of content BTS releases, there’s still hours where they’re beyond the camera’s gaze. Are they the same in front of it as they are apart from it? Would they still profess how much they love ARMY if no one was there to record them? Would RM be as well-spoken? Would Jin’s laugh be the same?

It’s only been a month or so, but it’s difficult for me to recall what exactly happened when I gave Shownu, the leader of Monsta X, a horrifically awkward half-high-five-half-handshake. I tried to record what happened right after the event, but I was so shocked that all I could write for him was “funny little smile,” which doesn’t help much when I’m trying to piece together the memory.

Even in the moment, it was difficult to parse exactly what that “funny little smile” meant. There’s only so much time to think when you’re given just a split-second glance. Had Shownu been teasing, playing the flirt that loves all his fans as idols are expected to? Had he been genuinely excited to be there? Had he been embarrassed? (I know I was.) Maybe the smile hadn’t been funny, or little, or even a smile at all--maybe I’d read the moment all wrong.

Funnily enough, Shownu features on a song called, “Don’t Look Back.”

[« prev] · [next »]

1 note

·

View note