#it has been too long since my pencil realism era

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

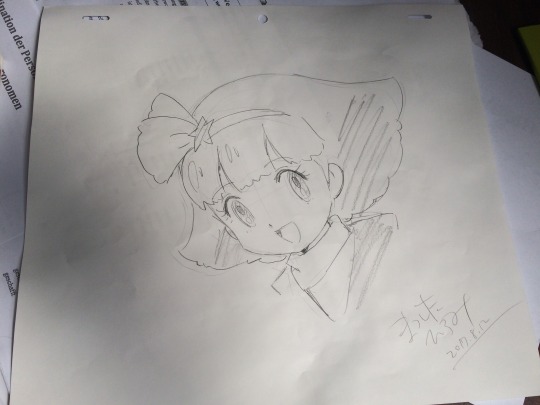

My three comfort characters

Sevika, Sevika and Sevika

#draw your comfort characters#sevika#sevika arcane#arcane#arcane fanart#arcane sevika#illustration#fan art#pencil#Loving the quality>:|#Three sevikas in one car doesn't sound too smart#I'd be shitting bricks if I was there#I hate how the bags under her eyes just disappeared when I tried to take pictures#it has been too long since my pencil realism era#I forgot how annoying medium it is go photograph#myrkkymato art

169 notes

·

View notes

Text

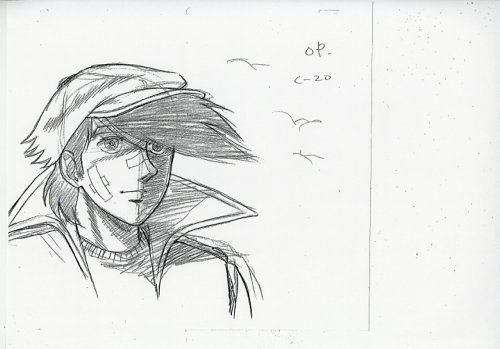

Notes on Animation Quality in Anime

I had a rare chance in 2017 to meet Hiromi Matsushita, one of Minky Momo’s most prominent animators. Matsushita is still active in the industry, and when I entered the room he was focused on drawing a scene, which he finished in around 10 minutes. I think he didn't lose his skills yet. I asked him for a drawing, of Momo of course, a request he found too hard even with the help of an image of Momo from google. More than 10 minutes passed, a lot of drawing and redrawing on the same paper, he handed me the illustration saying: “I’m sorry, this isn’t the real Momo.”

Now, I’m not saying he couldn’t draw her correctly because he got used to the radically different anime drawings of today, it may be because he just forgot how to draw Momo, or any other reason for all I know. Whatever the reason was, anime drawings and character designs had changed radically, evolved if you will, through recent Japanese animation history. The common answer to the reason behind this change always seemed funny to me, which is “because technology.” It’s not enough to just deny this claim, so I’d like to elaborate more on why and how anime drawings change over time. This is obviously a big topic, so what I’ll say here would be more of my (personal) perspective on the matter. Take it however you like.

I should start with defining what I mean with drawings. I’m not talking here about coloring, effects or the like, I mean the bare drawings themselves. This is literally the key drawings (frames), and to a lesser degree the in-betweens. Character designs are their own thing as well. This means that advancements in image quality and related technologies don’t count, since remastering a movie from the ‘70s in HD doesn’t mean the drawings themselves changed at all, forget about improved. Another point is the difference between the drawings on their own and how they move, i.e. the difference between animating and drawing, still there’s a direct influence between these two I’d like to talk about as well.

Sometimes, I feel like people look at the animation industry the same way they look at the gaming industry in this regard, not helped by the fact that mainstream high-budget animation productions in the US adopted the same technology for animating (CG). As for the Japanese industry though, it’s and has always been the pencil and paper. I’m not denying all the technological advancements that happened, but they weren’t fundamental changes that improved the quality of a drawing on paper. Even then, there were mostly only two new major technologies used introduced in anime production in the last decade: Digital coloring in the late ‘90s, and Xerography in the late ‘60s.

Xerography is basically a technique to copy drawings from normal paper to cels for coloring. Cels obviously can’t be drawn on due to their fragile nature, I believe. I rarely saw anyone talk about this technology before (in anime) so I’ll try to do a simple and short introduction. It was first introduced to Japanese companies through Disney’s Delmants 101, which caught the attention of Toei Douga (Toei Animation now). Toei took the device and modified it, most importantly adding an extra camera used for tracking perspective. Mainly to make drawings larger/smaller as they moved towards/away from the horizon. This device first saw use in Toei’s “Ken and Wolves” TV show early ‘60s. It wasn’t cheap nor easy, so Toei sought a better alternative, one of which was a device called “Trace Machine - ツレースマシン”, first used in “Sasuke” late ‘60s. It’s hard for me to point out how these two devices differed, but one advantage of the Trace Machine was conveying the original delicacy and feeling of the traced drawings better, something Disney’s machine didn’t manage to do quite well. Sasuke was praised for capturing the original soul of the manga, and it wasn’t Sasuke alone, Gekiga adaptations saw a rise in that era due to this machine making capturing the roughness of Gekiga drawings possible. Just look at Tiger Mask or Samurai Giants. I’m not sure here, but it seems like Xerography didn’t saw mainstream use until later in the ‘80s, probably because of costs. Anyway, here’s a Japanese article for more info.

As well-known it may be, we need a quick review: Astro Boy. Toei was aiming for a “Disney of the east” status, and really the idea of periodically producing anime was so strange back then, in Japan at least. The ~2 hours movies of the time needed years, so 20 minutes weekly was just insane. And insanely different were those TV productions from the quality movies of the time. You may have heard this before, but really watching clips of Astro Boy is the only way to understand how primitive it was. Nonetheless, it succeeded in becoming the standard for TV anime, and TV anime becoming the standard for anime in general later on even for movies. All the downgrade in quality of animation and everything.

This is where most people would start bashing the TV industry, yet I have a different perspective on the matter. The huge output of the Japanese industry is the main reason it reached its current international success and behind Japan’s status as the animation capital of the world. TV in America may have had a catastrophic effect on the industry, and wasn’t without negatives in Japan, but the way TV was handled and evolved is vastly different between the two countries and in turn the two vastly different outcomes we have now. TV in Japan presented a steady stream of relatively quick and flexible projects for Japanese creators to learn and experiment, a stream that only grew further increasing the variety of works and styles, the best thing the Japanese industry is known for now. Almost all well-known Japanese creators today had their start learning and experimenting in TV.

The huge amount of works produced was pretty useful for training creators in an environment that relies on learning by doing and still, to this day, mostly lacks any effective prior training system. Look no further than Tomonori Kogawa, who had a degree in fine arts, to see the important addition for properly studying and learning art. Kogawa kinda reminds me of Akino Sugino, not that their styles are similar or anything, it’s just that both care a lot about drawings quality. Ashita no Joe, which he supervised, had probably the best drawings quality of its decade.

When it comes to animation though, Toei Douga movies followed a similar realistic approach to Disney in treating characters as if they are actors on a stage. After TV anime emerged the principle remained the same, so creators just tried to replicate life in a working condition much more limited and restrained than that of Toei. Quality improved generally after some adapting and experimenting in this new landscape, but the focus mainly wasn’t on animation quality anyway. It was stories and direction that counted, Tomino and Gundam as a prime example. Even the “anime boom”, initiated by Yamato’s movie in ‘76, didn’t change that. The real change in that regard only came after treating animation in a more free way, free from the obligation of imitating real life I mean, which was the way Yoshinori Kanada treated it.

I won’t get into Kanada and his style, sources on him are enough anyway, what we need here is just the result of his wild popularity in the early ‘80s: Changing people’s view to anime. Before Kanada came, the only industry celebrities were directors, while animators stayed unknown. Not anymore. Kanada was maybe, for a time at least, number one in the industry, and this just goes to show the change in mindset: Animation is at the forefront now. And how did Kanada animate? Pretty unrealistically.

Let me detour a bit to talk about realism first. I remember some saying that Akira ushered in the age of realism in anime, a claim certainly far from the truth. Akira is rather the pinnacle of this long going approach. Pinpointing a start isn’t of much use in this discussion anyhow, and if not for my appreciation of documenting such info I wouldn’t have brought this up at all, but my argument is that the start of realism in animation is the start of animation itself.

Yet an important question must be addressed here: What realism are we talking about? If you think of it as just replicating life, then you’re oversimplifying animation as a whole. There’s only one way for things to move in real life, restrained by physics and all, but animation offers a multitude of approaches to represent movement, ways that imply realism nonetheless. And different approaches were popular at different times throughout anime history.

Take Utsunomiya for example, who wasn’t sure about joining the industry at first. He knew how the situation was, and how hard it would be to create anime in the same or similar to Disney and early Toei movies’ style that he so admired. I personally always found it weird how people held Utsunomiya’s style for realistic. His style is maybe considered as the epitome of what Toei’s theatrical realism aspired to achieve, and the main characteristics of that are exaggerated acting and theatrical movements, which is maybe not strictly realistic or natural. Nonetheless, as for weight and spacing, there’s no denying his accuracy and fine execution. Akira, and to a lesser extent Gosenzosama-banbanzai, are the embodiment of his and Takashi Nakamura’s approach in animating.

See this scene from Utsunomiya

I don’t know much about 70’s and 60’s realism, but the main description I read at least was, again, the theatrical realism influenced by Disney. The Kanada “revolution” was more of an abnormality, since realism returned to be the dominant style of anime after a while, and its evolution didn’t stop anyway. A lot of the pioneers of the next realism wave started or matured under the Kanada age, such as Takashi Nakamura or Utsunomiya.

There are different aspects to realism as well. One of Takashi Nakamura’s famous scenes, his scene in Gold Lightan, is considered to be a very realistic depiction of debris and stones in his time at least. Others depict effects and liquids realistically and so on. I feel like this is just a matter of approach and perspective. Utsunomiya for example saw the characters as actors on a stage, Ohira saw them a lot of times as gelatinous almost liquidy shapes, but all those approaches and depictions induce a realistic feeling in a sense, and are finely (and realistically) timed and weighed in their movement.

See this scene from Takashi Nakamrua. Notice hand and mouth movement.

Of course not all animators can do realistic movement well. Miyazaki and others complained about every other animator in the early 80s’ being a Kanada knock-off, a bad knock-offs in a lot of cases, yet Kanada’s style wasn’t hard to imitate, maybe not perfectly but definitely to a “good enough” degree. Realism on the other hand is hard, even harder in shows that lack talents such as Utsunomiya or time and budget. It was obvious after Akira, or even a while before Akira, which style the industry (or the audience) will prefer. And at that point the industry took a different approach to realism, not the realistic movement approach seen in Akira and movies that established this style in Japan to begin with, but an approach that gives the feel of realism in different ways, first being character designs and increasing the lines and details in drawings generally.

If we go back to the ‘60s and some of the ‘70s we can see many shows with designs rich in lines or styles close to realism, but it was mainly the exception and didn’t represent the main trend, some of which being caused by things like Gekiga or personal styles such as Sugino’s or Osamu Dezaki’s. Late ‘70s and early ‘80s mainly had simplistic designs which really helped Kanada’s style grow and spread. Simplicity contradicts realism by nature, and adding more lines or details to a drawing makes it harder to draw/animate. Straightforward, and this is just what happened after the demise of Kanada’s style, more realistic designs that barely move. Just look at any OVA from that period and compare it to any OVA from the Kanada wave. Amazing what 5 years could do!

Vampire Sensou in 1990. Interesting character designs, not much movement though.

Difficulty of drawing isn’t the sole problem here. Kanada’s style, despite its energetic nature, doesn’t require a lot of frames, actually the low number of frames is one of its strong characteristics. It’s a style born from the constraints of the Japanese industry to begin with, and if you think about it probably no other industry would have given born to such a style but the Japanese one. While you need a substantial number of frames to achieve a convincingly real movement. Maybe I’m over exaggerating here, but the Japanese TV industry tried two decades to achieve realism in an environment not suited for it and found Kanada’s style that embodied the sole of this industry, just to abandon it for an unconvincing realism.

Kanada’s OVA “Birth” in 1984 is probably the important turning point. Maybe you could say that the story of OVAs is also the story of Japanese anime, as OVAs reflected the state of the industry in general in each period. Maybe because OVAs were the direct way to reach the audience without the need for a TV channel or a distributor or even a high budget, in turn being a demonstration of the audience’s preference. It was definitely the free expression window for creators, young independent ones especially, free from any obligations for any big company. Obviously big companies were there, even more so in the late ‘80s after OVAs matured, but all in all it was the will of the creators that shined through. OVAs also played a decisive role in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s, when anime (TV especially) was facing a hard time due to different reason beyond the scope of this article. This led to OVAs influencing the development of the industry in interesting ways, hard to imagine if you look at the state of OVAs now.

The Japanese industry relied heavily on TV since pretty early on, so any problem facing TV anime is a problem for the industry as a whole. Middle/Late ‘80s wasn’t the best time for TV, a long story with multiple causes such as the change in demographics and emergence of video games, but our concern here is the paradigm shift that happened. For the most part and up to that point anime revenue came from games or manga or something else, a separate product. Not the show itself, meaning that its quality wasn’t a concern as long as it supported the primary product well. This obviously didn’t hold Ichiro Itano back from doing his wonderful circus scenes, or Tomino from executing his different depiction of mecha anime, but those again were creative acts on the personal level not the project as a whole, and in the end it wasn’t Tomino’s direction and vision that saved Gundam, it was the Gunpla.

It’s a fine system as long as the audience keeps on buying your primary product, something a lot of companies struggled with later on, reaching the OVA system where you just sell the show itself rather than a separate product. A similar system to movies, but simpler, safer and with less parties involved. We take internet for granted today, but in the ‘80s OVAs were the only choice for creators wanting to self-publish something weird or radically different, something that obviously won’t be backed by big companies.

Anyway, selling the show itself is completely different approach with completely different focus points. Quality comes first now, and first of all is drawings and animation quality, since anime is a visual medium after all. Without constraints or demands from distributors or any tight schedules, and with making less episodes, you’re able to raise quality considerably, the main selling point of OVAs. Patlabor, Gunbuster or Gundam 0083 all had high quality and were big successes, not only setting the standards for visual quality in anime, but also showing how important visual quality in anime is, both for companies and audiences. After this model matured, attempts to replicate this success in TV anime started, where the potential is much bigger due to the wider reach, which led to the contemporary late-night model we have now, maybe the most successful anime model till quite recently. Evangelion is considered to have played an active role in establishing this model, and in increasing visual quality in TV anime generally, and Ryusuke Hikawa claims that what he calls the “Quality Revolution” in the anime industry started in the ‘90s. I also think that Evangelion played no small part in establishing the production committee system we have now in every show, but I’m not quite sure.

Before I end this I want to link two nice resources for further reading. The mecha history research and an article that came in Akira’s Animation Archive, both by Ryusuke Hikawa.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Where Do I Even Begin?

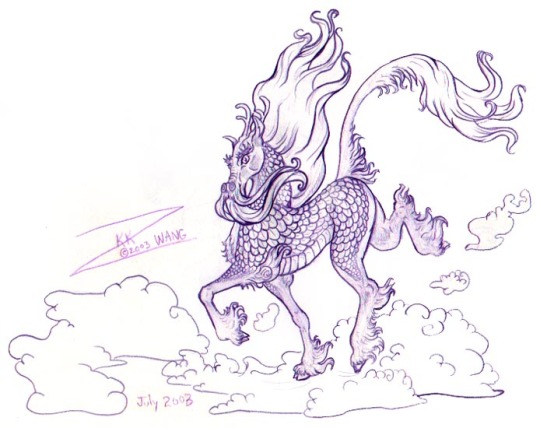

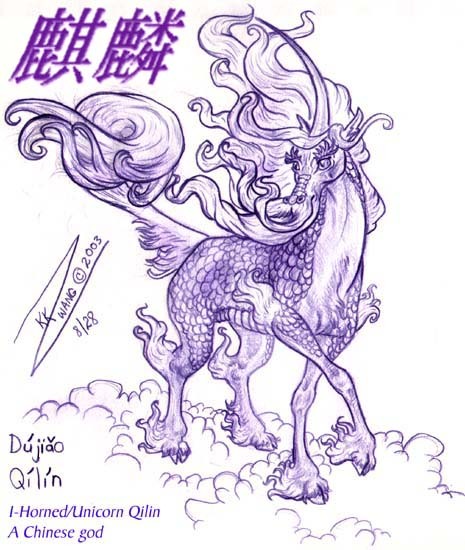

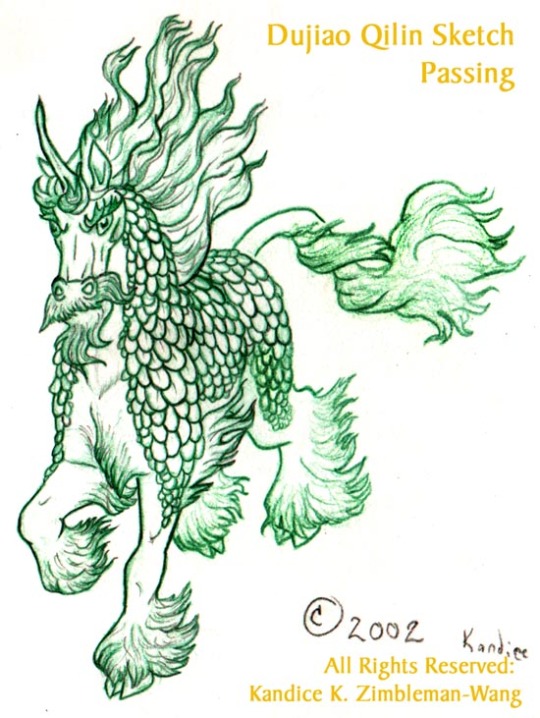

Well, first of all, I’ve LOVED LOVED LOVED Qilin ALMOST as much as I loved Unicorns, and Dragon. I say ALMOST because I first saw a unicorn on TV when I was 4 years old in the EARLY 1980s! But, I’d never even heard of a so-called “Chinese Unicorn” since about the mid-late 1980s when I saw a children’s magazine called “Cricket” which had a WHOLE SPREAD about UNICORNS, including the Chinese & Japanese versions.

(I don’t believe this was the actual cover. I can’t remember what year the Cricket Magazine issue was, just that it was in the 1980s. This issue was cited in many books written about Unicorns as well, following its syndication. It had a full on spread including many kinds of unicorns from many cultures... if I recall correctly, there might even have been an French Unicorn story as well.)

When I was a little kid, I actually didn’t like to read (which was an issue by the late 1900s, and even the government would talk about it, the trouble was they’d demonized comic books in the 1960s-1970s, which resulted in that problem, because even tho’ “correlation doesn’t equal causation” they didn’t know that and thought that the act of reading comics made you into a criminal. My experience was the exact opposite, because I read super hero comics a lot and was more interested in THAT than things like doing hard drugs, vandalism, and shoplifting which was rampant in NJ where I grew up.) So, by the late 1980s-early 1990s children were encouraged to read, read, read. Well, I liked pictures, and I LOVED: unicorns, dragons, and dinosaurs, ANYTHING FANTASY, but also Sci-Fi. (I also loved Marvel Comics/X-MEN, and Disney Adventures Magazine, and nearly all the Jeffrey Katzenberg hit Disney Films)

So, whenever it was something of interest to me, I would read a lot, and I had stacks of books, which I also used to practice learning art, and I was self taught. (I have A.D.D.)

I graduated in May 2001 from the Art Institute of Philadelphia (Majored in Computer Animation AKA CAM). And, by the GW Bush Era, I had already been active online since 1994, and had been blogging, and using many various art websites.

By late 2001, and most of the early 2000s (2001-2007) I spent months and even years sketching and drawing Qilin, interacting in the Furry/Anthro Fandom, and published a lot of my works to GeoCites/Yahoo, and had even created my own message boards, and so on. I even had one called “Qilin Savanna” Altho’ much of these sites are gone, my original works still remain on DeviantArt in my gallery HERE. (I also LIVED IN CHINA many times in the GWB Era often.)

Since that time I’d also written a lot of things, multiple times over, about my research into Qilin (which are not all unicorns, just some).

If you were to type in “qilin cartoon” into Google you can actually see the many many photo images that come up since the time I’d first started publishing my work ONLINE, FOR FREE, you can actually see how my works have influenced people. Back then, there was a MAJOR mix-up with the term, because MOST information available in ENGLISH regarding CHINESE EVERYTHING was often inaccurate, used the dead Wade-Giles Chinese language, or were often confused with JAPANESE. Another issue was that I actually could speak standard Mandarin Chinese, but many people wrote the Cantonese names, or FREQUENTLY confused them with Japanese name for the exact same character (AKA kanji, AKA Hanzi), which is “kirin” in Japanese. Also, the majority of NON-Chinese speaking persons don’t know how to pronounce Mandarin pinyin. (Example: Can you pronounce?: chi, qi, shi, xi, zhi, zi, qu, chu, er, ri, ren, si, ran, yu, you, bo, po, zhou, zhu, cao, zui - Most Non-Chinese speakers CANNOT pronounce these correctly at all. “Chi” sounds like “Tcher” and “Qi” sounds like “Tchee”, “Shi” sounds like “scher” and “xi” sounds like “schee”. There are also variations on pronunciation.)

But, I still stuck to the facts. my father-in-law in China,The late Wang Zimin, actually had special access to a restricted library, and wrote letters to me about Qilin, and the 4 major Chinese magical deities: Qilin, Long/Dragon, Fenghuang/Phoenix, Bixi/Dragon-Heard Tortoise.

Back then, mostly you needed to search “kirin” especially because M. Peña called her artwork “Kirin” but still also called them “Chinese Unicorns”. Her gorgeous sculpture works were sold everywhere for years, nation wide, from the boardwalk to Spencer Gifts, to Flea Markets, and Christmas season mall kiosks.

But, as you scroll through all the works produced since that time, not only the ones titled or tagged as "kirin” but over time “Qilin” starts to replace this as more and more people growing up actually start to study Chinese, especially artists and customers, and many of these young artists are either my fans or students, but fans or students of my students... after a while, people forgot who I was... but my work BECAME PART OF THE CULTURE.

You can SEE that many people emulated my poses, my styles of doing hair, and many other details. Over the years, a number of my fans, and friends would send me private messages FREAKING OUT that either someone stole my work, stile my style, or ripped me off...

That’s actually NOT TRUE. No one ripped me off. THOSE ARE MY STUDENTS.

You guys ASKED ME things like: How do you draw _____? so I made countless cheat-sheet style tutorials (because paid classes don’t ACTUALLY TEACH). Also, if someone wants to learn, (like myself) they try to draw from WHAT THEY LOVE. That means ME. MY ARTWORK. How else will they learn if they don’t copy, ask questions, etc.?

I have many many open source materials in my DeviantART gallery (which are STILL MY MOST POPULAR WORKS OF ALL TIME despite the hours of work I’ve produced artistically.) I have also licensed much of my line art works FOR FREE for people to practice coloring with wither digitally, or to print them out and color with real media like markers, color pencils, pastels, or whatever because people kept asking me.

Actually, I would like to credit a number of artists whom are my biggest influences as well:

Susan Dawe

Glen Keane

Alan Davis

Those are my biggest ones, but I also loved artworks by Burne Hogarth, Auguste Rodin, Edward Degas (I especially love his ROUGH sketch work), Frank Frazzetta, Boris Vallejo & Julie Belle, Fred Moore, Vladimir “Bill” Tytla, AND the film The Last Unicorn was especially the #1 thing that got me actually DRAWING when I was 4 years old.

SO much of my work, especially ANYTHING with unicorns, has been tattooed onto people bodies. Many people personally asked my permission, but I honestly DO NOT MIND. I have found over the years more examples of my artwork tattooed onto people than I can count. It’s LOVE.

However, I’ve also many many times been the victim of theft FOR REAL. Many people have tried to rob my sketchbooks, and many companies have illegally robbed my artwork online. It was the cause of MUCH online fights, wars, and battles. There’s also impersonators: People pretending to be ME, or claiming THEY did my work: also the cause of much much online fights and flame wars.

-Then, of course, there’s LOTS & LOTS of kids online that “rob” my work for RPGs, and fan pages... Honestly, I’m NOT going after children, or fans, for harmless things like that... I’m NOT Metallica.

So, where am I going with THIS?

Well, for one, there’s both ART and PHILOSOPHY which are BOTH a MAJOR part of my life.

I had a number of setbacks, delays, and many other strings of very unfortunate events in my life. Needless to say, I was very depressed. However, I did find myself back in college, first for Philosophy, and then for Art, especially Video... which somehow saw me thrust forward into Animation HEAD-FIRST. Suffice it to say, I’ve worked through, blew threw, and past, all of my blocks, and have been doing animation again. (lots more long stories, but not writing them here)

Many many times, you can’t always reach, yet, what you want. Other times, other persons, or groups want to change you, or make you something else.... and not you. But, it kills you inside...

At some point, you need STOP listening to everyone, and everything else, ESPECIALLY if that’s not FLOWING in the direction are are INSIDE.

I’d already WANTED to produce at least 2 series/films of my own. (”Eyewitness” and “Zenith Beyond The Dragon’s Rue”) Well, THIS is a branch off that tree. This stems from my concepts for “Eyewitness” but sort-of... I had ALWAYS wanted to produce my own small animated shorts, especially with music, like the old 20th Century animated works such as “Silly Symphonies”, “Merry Melodies”, and even Disney's “Fantasia”, but also a number of influences from Far East Asia including PR China, and Japan.

I’ve been multiple times inspired by Socrates, Plato, Laozi, Bruce Lee (Li Xiaolong), and many fusion artists/dancers on the American West Coat including my teachers: Zoe Jakes, and Alyssum Pole, as well as Rachel Brice, Carolena Nericcio, Jamlila & Suhaila Salimpour, but also Matahari, and Kerli Kõiv. People that think differently, question things, or create their own ideas, or even fusion artists.

Well, this project has been on my mind since at least 2001.

In fact, my actual name (Ming Zi) in Chinese is: 任思麒 (Ren SiQi)

It literally means: Duty/Task [to] Think/Contemplate/Dream of Qi[lin]!

Also, as an artist, there are a number of things I believe in, whereas other things I’ve shed like a snake molting its skin. I’m a fusion artist, an eclectic artist, but I still firmly believe in art fundamentals like life drawing, practicing one’s skills, and I use bot digital and real media. I LOVE TO DRAW. I firmly believe in Quality OVER Quantity, yet, in some instances I also think too much detail is overdo, and somethings look better less refined. I like realism, stylization, cartoons, and beautiful things.

I want to create content that is LESS about “being a big success” or ego driven ideas of “stardom”, and lavish money making, but more about THE LOVE OF IT.

I do NOT want to be part of any establishment groups, crowds, clubs, or institutions, and DON’T want to be mainstream, NOR corporate. I have found all of those things to be negative and destructive to my life and therefore regret pursuing those avenues. I’m NOT interested in walking those paths, nor dunking helplessly into those turbulent or stagnant flows, but RATHER Flow my own way, because I have my OWN PATHS. I don’t need to buy their metaphorical light bulbs, because I have my own light that I can shine inside of me.

And, if I am being completely frank & honest, another MAJOR influence on me WAY BEFORE HE WAS EVEN POPULAR was Bernie Sanders. I am a Berner. Sanders actually GAVE OF HIS HEART & HIS TIME FOR FREE. He crowd funded for what he believed in with SMALL MONEY because he was against BIG MONEY.

I have no care for being in exclusive film festivals or galleries. People whom already LOVE my work find their way to it. People HAVE found value in my efforts and work.

Therefore, I wish to begin producing this animated short. It is not cheap tho’. But, I will gladly share my process, my concept work, my practice work, and everything FOR FREE. Free to ALL ARTISTS, and people whom just live beautiful things, art, and QILIN.

I wish to pursue an independent direction in my art. But, I would very much like to include people, if not the world or those in it that care about these things, to interact with me. A long time ago I’d created my “Qilin Savanna” site to interact with people whom also loved Qilin, Unicorns, Dragons, and other things, but also a love for art, or learning art.

This year (2017) while interacting with MANY MANY young people, and young artists, I often found that people WANTED to learn to DRAW, to improve their techniques and practice them, but despite having paid money to attend art classed (including “drawing classes”) they did not actually get what they paid for, did not actually get instruction for what they wanted to learn, but either had to fend for themselves, try independently, or got resources online for free... so, why then were they paying for it?

I have many many times, spent just a short moment with frustrated peers, students, classmates, friends, and fellow artists whom couldn’t draw what they wanted to, and teased me for being some kind of special person... when in fact, whatever I do, others can too. I sat with them, explained, and demonstrated (AKA Using The Feynman Technique) and after that moment of AHA THEY COULD DO IT. And, they didn’t need to come back.

I did THAT FOR FREE.

I did THAT FOR LOVE.

And, NO, I DON’T HAVE A MASTER’S DEGREE. Honestly, at this point, I don’t feel I actually want one. I DON’T want to be a part of that club, nor establishment either. In this way, I’m somewhat like Socrates, Diogenes, or Bruce Lee... only NOT. I’m ME.

I have a lot more to say, but I think I will leave it here for now.

#qilin#kirin#Kylie#Chinese unicorn#animation#cartoon#drawing#art#Kandice Zimbleman#Black UniGryphon#BlackUniGryphon

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The hidden river, the longest waterfall

The guns are silent and cold, but the memory of their report still echoes across the land. Vietnam lingers, especially for the eager volunteers and luckless conscripts who crossed the Pacific to fight it. They are in their maturity now. They sit in the Congress, they stand along the assembly line, they sell pencils in the street. Some have tried to bury their past and forget the war. Many more have searched for a way to remember. They have a new mission now, one that began when the fighting stopped. This is the mission to make sense of the senseless, to find some provision in a storehouse laid empty by waste.

When the veteran is an artist - a writer, a sculptor, a cinematographer - his war almost invariably becomes his subject. ''The soldier who has seen blood spilt'' is a marked man, said the historian Dixon Wecter in 1944. ''It remains a dye in the fabric, a warp in the wood.'' Oliver Stone, film writer and director, is one of these men. On Sept. 15, 1967, he reported for duty in Vietnam, an infantryman, or ''grunt'' as they were called, a member of the 2d platoon of Bravo Company, 3d battalion, 25th infantry. He served in two other units before his tour was done and was twice wounded and decorated. In 1976, he wrote a screenplay about his comrades and the war they fought. Now, 10 years later, he has turned his script into a movie, ''Platoon,'' a graphic and often brutal film that is likely to unsettle even those who lived through the war's restless nights and incendiary days.

Mr. Stone says his aim was to ''make a document of a time and place,'' to re-create the reality of Vietnam so that those who stayed home or came of age after it ended would now know ''what it was like to be there.'' An artist, of course, has no obligation to state his purpose or explain his work. The substance of what he creates is its own message. His style is his metaphor for meaning. But Vietnam was more than a shooting war across the sea. It was as well a political and cultural struggle at home. The fighting along this ''second front,'' as it might be called, is now sporadic, but the skirmish lines are still hot, and anyone who takes a place there - novelist, playwright, film maker - should be prepared to defend himself.

''Platoon,'' at the Astor Plaza and New York Twin, has a simple and familiar story line. The protagonist, Chris Taylor, is a 21-year-old child of privilege who volunteered for the draft and Vietnam because he was convinced that young men who had grown up with less than him could teach him something about life. The war was to be his metamorphosis, his passage to manhood.

Taylor joins his unit in the jungle and a short time later is slightly wounded when his platoon, out at night to ambush the enemy, is surprised by its prey. In the weeks that follow, it becomes clear that the platoon is divided into two cliques formed around two sergeants who are rivals - Barnes and Elias - the former a figure of evil, the latter of good. Taylor falls in with Elias. At one point, after taking some casualties on a patrol, the platoon enters a village and begins to seek its revenge. Taylor, stunned and outraged by the death of his comrades, begins to take part in the brutality, then becomes horrified by it.

At the end of the movie, and of Taylor's tour, the platoon fights an apocalyptic battle with a large enemy force. Taylor is again wounded, but survives this bloody holocaust. As he is airlifted from the scene, his voice, speaking from the present, says, ''Those of us who did make it have an obligation to build again, to teach others what we know and to try with what's left of our lives to find a goodness and a meaning to this life.''

As a story, a narrative, ''Platoon'' borrows from the long tradition of war literature. Here is the classic warrior myth, the innocent who goes off to battle and comes back with what he believes is the wisdom of the ages. Here is war corrupting those who take part in it. Here is the survivor as hero. And, finally, here is the awful result of technology turned to destruction. The same story has been told in different eras by Stephen Crane and Erich Maria Remarque and Norman Mailer.

As a film, however, ''Platoon'' is an attempt to break new ground. Like other war movies, it has its share of cliches. (In one scene, a dying soldier drops to his knees and raises his hands to heaven. ''Poetic license,'' says Mr. Stone.) But it is a rare film in that it tries to re-create the grim chaos of combat. And it is likely the first film about Vietnam to give a sense of the persistent fear, discomfort and hard labor of fighting there. It is possible to argue with the way Mr. Stone drew his characters, the way he choreographed his battles and his various explicit and implicit messages, but few veterans will find any fraud in his milieu and many will remember the way combat left them feeling numbed and stupefied.

Mr. Stone, of course, did not aim his movie at his own kind, his comrades. He is sure its appeal will be broad, and his opinion might be well founded. The currency of war is violence and death, issues, wrote the self-described psychohistorian Robert Jay Lifton, that are ''all too real'' for everyone. Confounded by these issues, those who have not witnessed death ask questions of those who have. Rare is the combat veteran who has not been pushed to answer: ''Did you kill anyone?'' and ''What was it like?'' Some of the questioners were no doubt preoccupied with death. But most were simply looking for help. As Dr. Lifton wrote, they were involved in the common ''struggle to come to terms with the realization that one's own life could and would be at some moment snuffed out.''

To convey ''what it was like,'' said Mr. Stone, ''We took a lot of pains with details.'' The film, with a modest budget of $6.5 million, was shot in the Philippines between March and May, monsoon and summer. The Philippine Government supplied the military hardware and equipment and a former Marine Corps captain, Dale Dye, the film's technical adviser, provided much of the verisimilitude. He ''trained'' the ensemble of young actors, putting them through a 14-day boot camp to prepare them for their roles. ''Actors have a great imagination,'' said Mr. Stone. ''They were able to take those two weeks and turn them into months.'' Makeup artists gave Mr. Stone the details of gore for his wounded and the gray pallor of death for his corpses. All that was left was to haul in ''tons of dirt'' to keep everyone filthy and covered with mud. When everything was set, the cameras began to roll, and 54 days later Oliver Stone began to film a script he said no one wanted to buy a decade ago.

This is the second major movie Mr. Stone, 40 years old, wrote and directed. The first was ''Salvador.'' He also wrote the screenplays for ''Midnight Express'' and ''Scarface.'' His material has been topical, his style graphic. Someone, he says, proudly, once described him as a cinematic provocateur.

''Platoon,'' in many ways, is a chapter in his autobiography. The character of Chris Taylor has the psyche of Oliver Stone, and when the director is asked a question, he will sometimes refer the interviewer to his screenplay for the answer. Why, Mr. Stone, did you volunteer for the draft?

''CHRIS VOICE OVER: I guess I have always been sheltered and special. I just want to be anonymous. Live up to what grandpa did in the First War and Dad in the Second. I know this is going to be the war of my generation.''

Mr. Stone was born in France and raised in New York City. In 1965, he dropped out of Yale during his freshman year and, filled with the words of Joseph Conrad, set out for the Orient and adventure. He paid his way to Saigon and took a job in the city's Chinese district teaching school at the Free Pacific Institute. ''I was 18,'' he said. ''My father treated me like a child and I wanted to prove I was a man.''

Six months later he took a job in the engine room of a merchant ship run, he said, ''by characters right out of the 19th century - the fat captain, the soldier who worked for the C.I.A., the strong bull of an engineer.'' He switched ships, sailed through a hurricane to home and in 1966 took up temporary residence in Guadalajara, Mexico, where he began a 1,400-page autobiographical novel called ''Child's Night Dream.'' A few months later, he returned to Yale, but not to class. He kept writing his novel and flunking his courses. In 1967, he tried to get his work published and was rejected.

''I was upset,'' he said, ''heartbroken. I wanted to go back to Southeast Asia. But I wanted to get to another level. I hadn't hit the bottom - you know, in the screenplay on Page 15.''

''CHRIS VOICE OVER: I've found it finally, way down here in the mud - maybe from down here I can start up again and be something I can be proud of, without having to fake it, maybe. . . I can see something I don't yet see, learn something I don't yet know.''

So, like his French grandfather in World War I and his American father in World War II, he went off to fight. And now, 18 years later, he has made a movie that tries to convey the passion of that search and the cost of the adventure. And yet, like many other efforts since the war, it does little to solve Vietnam's sobering conundrum or to provide the kind of meaning that Chris Taylor, the protagonist, or Oliver Stone, the film maker, is searching for.

Part of the problem might be Mr. Stone's attempt to ''document'' the experience. War, real war, is an obscenity. It is foul. It is repulsive. It is loathsome. War has no form and war has no style. It is the absence of art, not the substance of it. A film maker can suggest or evoke this ugliness and chaos, but he cannot capture the effect of a year of unrelenting terror and tedium on 113 minutes of film.

For all its graphic realism, Mr. Stone's film is still an adventure story, his protagonist still a kind of existential hero. ''I wanted to show the boy changing from an innocent kid into somebody who comes to include both good and evil in him,'' he said. ''This is a memoir of youth.''

Although the film is rooted in his experience - that is, it portrays events that either he or his unit took part in and characters he knew as comrades - ''Platoon'' might be taken by many as typical of what every soldier experienced in Vietnam. And if that happens, it will resurrect old and troubling notions about how American men behaved on a battlefield so far from home.

The most brutal sequence in the movie, the one that most prompted those who walked out of the previews to leave, takes place in a village. Angry and out of control, some members of the platoon begin to murder and rape civilians.

''I wasn't trying to call up My Lai,'' Mr. Stone said. ''This is not an academic film. It is based on my experience. We did shoot livestock. We burned hooches. One of my comrades did kill a woman. I did save two girls from being raped and killed. It was madness.''

It also was not typical. Yes, some men, perhaps many men, are just as brutalized by war as the innocents who wander into their sights. ''From the Homeric account of the sacking of Troy to the conquest of Dien Bien Phu, Western literature is filled with descriptions of soldiers as berserkers and mad destroyers,'' wrote J. Glen Gray, the philosopher and World War II veteran. However, he adds, ''destruction is ultimately an individual matter, a function of the person and not the group.'' And this particular truth about war underscores what seems to be missing from Mr. Stone's film, perhaps what he never came to know - the passion of comradeship.

There is little kinship for the men of ''Platoon.'' They may serve together, but there is no sense of self-sacrifice among them, no loyalty and no love. It is thus not surprising that many of Mr. Stone's characters come across as coldblooded killers. ''Comradeship among killers is terribly difficult,'' wrote Mr. Gray. And it is on this point, found so often in the art and memoirs of war, that a great many men will break with Mr. Stone and find his film lacking.

And yet, I am glad he prevailed and brought his story to the screen. It is a welcome counterpoint to the comic and grotesque characterizations offered by the authors of ''Rambo'' and other cardboard heroes. And Mr. Stone's reality is much closer to the moral truth of Vietnam than the chest-thumping of modern revisionists. What is more, it is time for the veterans of Oliver Stone's war, my war, to pass through what T. S. Eliot called the ''unknown remembered gate. . . the source of the hidden river. . . the voice of the longest waterfall,'' in short, the past. We may, at last, be ready to find our peace.

-Michael Norman, “Platoon Grapples With Vietnam,” The New York Times, Dec 21 1986 [x]

0 notes

Text

I tried to draw Abby with her hair down

#It has been too long since my pencil realism era#abby anderson#abby tlou#tlou2#tlou fanart#fan art#illustration#pencil#pencil drawing#myrkkymato art#Not my comfort zone anymore

217 notes

·

View notes