#isango ensemble

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

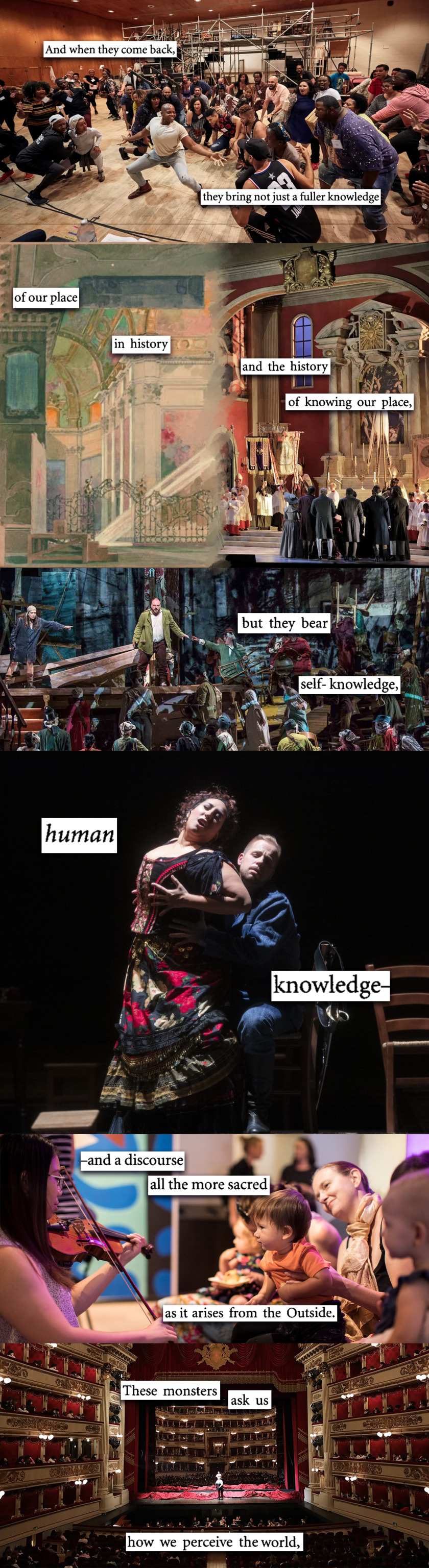

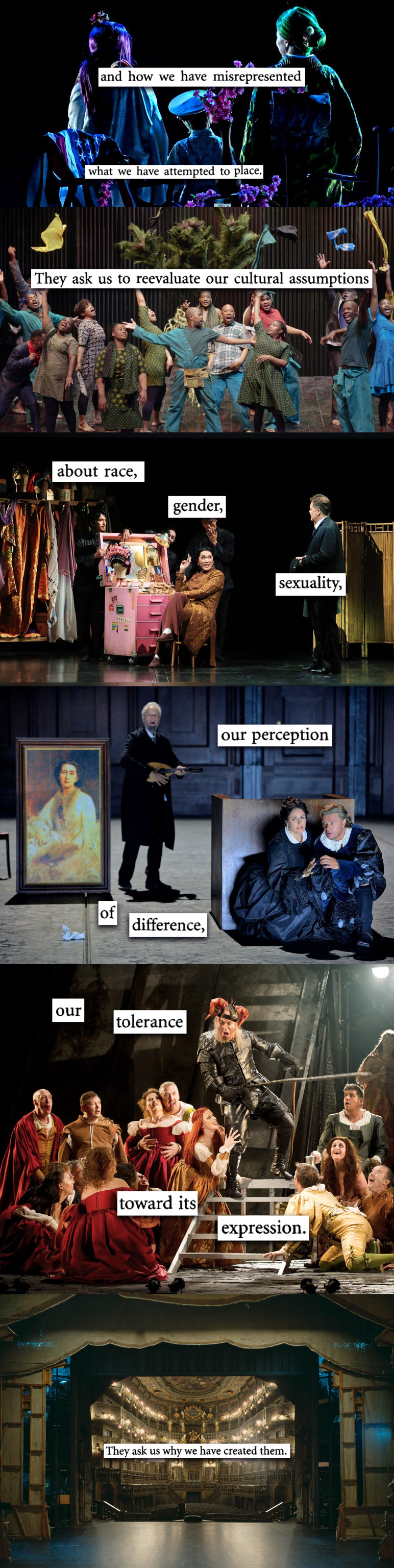

thesis vii. the monster stands at the threshold... of becoming.

-

jeffrey jerome cohen, “monster culture” / backstage at the magic flute at the metropolitan opera house, NY, circa 1905 / "opera house" by thomas rowlandson and auguste charles pugin / the philadelphia metropolitan opera house before and after renovation / porgy and bess in rehearsal at the met, dir. james robinson / tosca act 1 original set design by adolf hohenstein / tosca at the san fransisco opera, dir. shawna lucey / wozzeck at the opera bastille dir. william kentridge / carmen dir. juan guillermo nova at the sng maribor / kids music cafe at the sydney opera house / don giovanni dir. robert carsen at la scala / madama butterfly dir. matthew ozawa at the detroit opera / the isango ensemble's edition of treemonisha dir. mark dornford-may / m. butterfly dir. james robinson at the santa fe opera / die meistersinger von nürnberg dir. barrie bosky at the bayreuth festival / rigoletto dir. david mcvicar at the royal opera house / the view from the stage at the margravial opera house, photographed by klaus frahm

92 notes

·

View notes

Text

Character ask: Tamino (The Magic Flute)

No one sent me this ask, I just felt like writing it.

@ariel-seagull-wings, @leporellian

Favorite thing about them: His love for Pamina and the beauty, warmth, and ardor of the music with which he expresses it. I also like productions that make him less of a stalwart paragon and highlight his youthful naiveté and coming-of-age journey.

Least favorite thing about them: The degree of cold sternness he gains as a follower of Sarastro in Act II, of which poor Pamina and Papageno are on the receiving end. Also (and relatedly), his parroting the priests' misogyny in the Act II quintet with Papageno and the Three Ladies.

Three things I have in common with them:

*I can be passionate and hot-blooded.

*I tend to be very trusting.

*I sometimes blindly follow other people's instructions.

Three things I don't have in common with them:

*I'm not royalty.

*Where courage is concerned, I'm more like Papageno.

*I'm female and I don't consider "manhood" an ideal.

Favorite line: The text of "Dies Bildni ist bezauberndt schön."

brOTP: Sarastro and his priests; maybe Papageno too, but only in productions that let him be warmer toward him and less aloof and impatient than he sometimes comes across.

OTP: Pamina.

nOTP: The Queen of the Night.

Random headcanon: When he eventually rules as a "wise monarch" (whether as Sarastro's successor, or of his own father's empire, or however you think it will happen), Pamina will be his equal partner and co-ruler, but her role will chiefly be spiritual and philosophical leadership, while Tamino's will be worldly/political leadership. In effect, they'll both be heirs to Sarastro, but Tamino will embody the "king" aspect of Sarastro's style of ruling, while Pamina embodies the "priest" aspect.

Unpopular opinion: I'm not sure if this is unpopular, but... If the tenor in the role stands like a statue during Pamina's "Ach, ich fühl's," without conveying through facial expressions and body language that Pamina's anguish is breaking his heart, and if he does nothing to express his pain and remorse after she leaves (e.g. starting to run after her only to sadly restrain himself, collapsing to the floor, and/or breaking down in tears), he had better have a magnificent voice, or else he doesn't belong on the stage.

Song I associate with them:

"Dies Bildnis ist bezauberndt schön"

youtube

"Wie stark ist nicht dein Zauberton"

youtube

Favorite picture of them:

Georg Maikl, early 20th century.

Fritz Wunderlich, 1960s.

Josef Köstlinger, Ingmar Bergman film, 1975.

Unknown tenor (I just love how innocent and happy he looks, and I love the elegant animal costumes).

Michael Schade with Andrea Rost as Pamina, LA Opera, 2002.

Joshua Kohl, Sarasota Opera, 2010.

John Tessier, Seattle Opera, 2011.

Mhlekazi Andy Mosiea in the production by South Africa's Isango Ensemble, 2014.

Alek Shrader, Metropolitan Opera, 2014.

Pasqual Charbonneau, Opéra de Québec, 2018.

#character ask#opera#the magic flute#die zauberflöte#tamino#wolfgang amadeus mozart#ask game#fictional characters#fictional character ask

17 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Straight from South Africa, theatre company Isango Ensemble lands in Toronto Nov. 13 at St. Lawrence Centre for the Arts!

Don't miss this thrilling production that brings together music, dance, and theatre, all performed by a brilliant ensemble cast!

http://www.stlc.com/event/isango1/

0 notes

Text

Fall Preview

By Steve MacQueen, Artistic Director

A preview of what’s in store at the Flynn this fall. 2019-20 season tickets are on sale now at www.flynntix.org.

Another Flynn season is upon us, and this one is a whopper, featuring 40 Mainstage shows (last season had 28) and increased activity in FlynnSpace. That doesn’t even count late additions like Elvis Costello & the Imposters (Sunday, Oct. 27). I can’t possibly fit the whole season into this recap, but I’ll catch you up on our unusually heavy September before selecting a half-dozen shows from our overflowing October.

It’s hard to overstate the achievements of the monumental collaboration between composer Philip Glass and director Godfrey Regio. Basically, Koyaanisqatsi (Monday, Sept. 23) images accompanied by music. Simple. However, the images are mind-boggling—from staggeringly gorgeous nature photography to breathtaking time-lapse tours through urban areas. The music is among the chief works by Glass, one of the great composers of the past century. And the true miracle of the film is how the images and music inform each other on a second-by-second basis. Watching Glass lead his nine-piece ensemble through this score live, while the big-screen conveys these still-untopped images of a world in flux…a season highlight, for sure.

A while back, Slate published an article entitled Is Tinariwen the Greatest Band on Earth? I may not be willing to commit fully, but I am certainly willing to put this tremendous group up for consideration. Tinariwen (Wednesday, Sept. 25) is an unlikely band of world-music stars, as they are Tuareg nomads from the Sahara desert, a vast area from southwestern Libya to southern Algeria, encompassing parts of Niger, Mali, and Burkina Faso. Group leader Ibrahim Ag Alhabib’s story is the stuff of legend: as a child, he witnessed his father’s execution by government troops, and spent his most of his childhood in Algerian refugee camps, where he made a guitar from a can, a stick, and some brake wire. He taught himself to play, fusing Algerian rai and chabi music with Western rock (Santana is a big influence), then found likeminded Tuareg players and formed Tinariwen. After taking a break to fight as rebels against the Malian government, Tinariwen became a full-time musical concern in the ‘90s. Dubbed “Desert Blues” (though Alhabib says he had never heard American blues until he toured the U.S. in the early ‘00s), the group fuses beautifully hypnotic rock & roll guitars to a churning desert beat to create some of the most mesmerizing music you’ll ever hear. The music has certainly caught the attention of some Western musos, as the group has collaborated with Herbie Hancock, Los Lobos, Robert Plant, Dirty Dozen Brass Band, U2, and, in an example of the circuitous properties of influence, Carlos Santana. Welcoming Tinariwen to the Flynn this fall is especially gratifying, given threats the band faced recently on social media ahead of a North Carolina concert.

Rhiannon Giddens’ (Sunday, Sept. 29) vision of American music is one of the most compelling versions of our time. It’s about re-examining our history, and using those discoveries to create a launching pad for self-expression in the present. For instance, the banjo: it’s actually an instrument with African roots, one that was played by African Americans during the creation of American folk music, yet, as Giddens points out, “It was coopted by this white supremacist notion that old-time music was the inheritance of white America.” So she’s bringing it back. Giddens plays a replica of an 1858 minstrel banjo, which sounds more like a lute or Arabic oud than the super-bright, twangy five-string banjo we’re used to, and she uses it to create some of the deepest and frequently most harrowing music of the day. In collaboration with master percussionist Francesco Turrisi—who plays all kinds of frame drums from around the world—Giddens recasts folk tunes, childe ballads, popular songs, and everything else as vehicles for her own amazing voice, which plumbs the depths of whatever she’s singing. Trained in opera, schooled in folk and old-time, Giddens is an original who’s going to be making important, captivating music for decades to come. To quote the Smithsonian, she is “both a product and a champion of America’s hybrid culture, a performing historian who explores the tangled paths of influence through which Highland fiddlers, West African griots, enslaved banjo players, and white entertainers all shaped each other’s music.”

In October, the great Carole King gets the richly deserved jukebox-musical treatment with Beautiful which tells the story of a New York City schoolgirl who scores hit after hit as a teenage wunderkind at the Brill Building, then redefines herself—and popular music—with the mega-influential Tapestry. (Wednesday-Thursday, Oct. 2-3).

One of the greatest living Americans, Congressman John Lewis, takes the stage at the Flynn to tell his story as reflected in the Vermont Reads 2019 selection, the graphic novel March: Book One. Free! (Monday, Oct 7).

Chick Corea is simply one of the greatest jazz pianists and composers of all time, a man whose facility and expertise encompass bebop, post-bop, free jazz, fusion, classical repertoire and whatever else you got. Team him up with the A+ rhythm section of Christian McBride (bass) and Brian Blade (drums), and you’ve got a jazz show that even non-jazzers have to love. (Tuesday, Oct. 15).

One of the most strangely poetic shows I’ve seen in recent years, the cirque-troupe CIRCA’s Humans shows ridiculously fit people doing seemingly impossible tasks on their own, and then, with the help of others, doing things that seem even more impossible. The show can be viewed simply on the level of “Wow!” (and there’s lots of that to go around), but it also has something to say about human limits, and the power of community. (Saturday, Oct. 19).

The South African theater company Isango Ensemble has eared raves around the globe for its productions, and we were just lucky enough to land one of them at the Flynn. One of the company’s signatures is South-African-ized versions of Western classics, and Isango will perform its internationally acclaimed version of Mozart’s The Magic Flute, recast as an African folktale and re-scored for an orchestra of marimbas. Not to be missed! (Friday, Oct 25).

0 notes

Photo

From Shakespeare, Music and Performance

Music has been an essential constituent of Shakespeare's plays from the sixteenth century to the present day, yet its significance has often been overlooked or underplayed in the history of Shakespearean performance. Providing a long chronological sweep, a new collection of essays – Shakespeare, Music and Performance (ed. Bill Barclay and David Lindley) – traces the different uses of music in the theatre and in film from the days of the first Globe and Blackfriars to contemporary, global productions.

What can you expect from the book? Have a read of some snippets here.

From David Lindley and Bill Barclay’s Introduction:

Music has played a vital part in theatrical entertainment since the very beginnings of drama. The theatre of Shakespeare’s own time was no exception, and music has continued to make a highly significant contribution to the performance of his plays up to the present day. Exactly what sort of contribution, however, has been dictated by a variety of factors: by the number and range of musicians available; by the changing architecture of theatres themselves; by the historical evolution of musical styles; by the changing expectations of audiences; and latterly through the influences of film and television, and of sophisticated technology. It is the aim of this collection of essays to explore the nature and implication of these developments from the time of the plays’ composition through to contemporary performance both on film and in the theatre.

From William Lyons’ Theatre Bands and Their Music in Shakespeare’s London:

Introduction

With the rise in popularity of public and private theatres in Early Modern London, the opportunity arose for professional musicians to find employment in many of the bespoke playhouses that sprung up on both sides of the Thames. This essay considers the various styles and sound worlds incorporated into plays, and in particular who actually played the music. When musicians could be afforded, it was important to engage the very best available and in early seventeenth-century London the principal professional band outside of the royal court was the civic ‘waits’, a type of band whose skill and versatility were well attested. Whilst it is clear that waits were far from being the only musicians to be employed in theatres, I will suggest that it was the waits who contributed more significantly to the high standards of playing remarked upon by visitors to London’s theatres than hitherto recognised.

Waits were employed principally to provide music for civic ceremony and procession, particularly attending the Lord Mayor on such occasions. In a sense, the waits provided a ‘civic soundtrack that distinguished town from country’. This aural emblem of the city came with considerable perks; the official status achieved by being accepted into the waits (usually after a lengthy apprenticeship, period of probation and then interview) meant that the musician could wear the civic livery, which signified an official and elevated social status. They were also allowed to accept non-civic employment. As highly skilled and usually multi-instrumental professionals, the waits were able to provide a variety of sonorities and volume depending on what was required of them.

Theatre Bands and Their Music

In his dedication to The First Booke of Consort Lessons Thomas Morley refers to the ‘ancient custome’ of maintaining a waits band ‘to adorne your honors favors, Feasts and Solemne meetings’ and ‘your Lordships Wayts’, these ‘excellent and expert Musitians’ with their ‘carefull and skilfull handling’ are recommended the publication as much as is their employer, the Lord Mayor of London. Morley goes on to suggest that the waits can improve upon the arrangements ‘by their melodious additions’ and hints of a second volume of pieces ‘to give them more testimonie of my love towards them.’ Here is a publication that is unique, firstly for its precise specification of instruments – the ‘Treble Lute, the Pandora, the Citterne, the Base-Violl, the flute, and the Treble-Violl’, and in its recommendation to a specific group of musicians. What Morley fails to reveal, however, is the purpose of this compilation of twenty-three arrangements or why he recommends them to the waits in particular. The assumption has to be that these pieces reflect a repertoire of an already-established ensemble and one that was, at least in the case of Morley’s collection, particularly associated with the waits.

From Bill Barclay’s Music in the 2012 Globe-to-Globe Festival

In the Olympic summer of London 2012, Shakespeare’s Globe hosted thirty-seven theatre companies from around the world to perform a different play by Shakespeare in their own language, producing an unprecedented six-week complete works cycle beneath the halos of the Cultural Olympiad. The Globe-to-Globe Festival produced a magnetic parade of wonders, each humming with resonance along London’s ethnic fault lines, leaving Bankside daily awash in linguistic rarities, cultural reunions, political lightning rods, and nationalistic celebrations. The festival was also a maelstrom of musical industry featuring rarely heard ethnic genres, instruments, and songs that dynamically served Shakespeare’s stories in fresh and integrative ways. In the deliberate absence of a common tongue, music’s role as universal emotional storyteller has rarely seemed more relevant to international communication and understanding.

The strands of discourse that swirled about the festival were many and occasionally charged; the Cultural Olympiad’s World Shakespeare Festival echoed the Olympics in further welcoming the plurality of the world to share a stage in all its harmonies and controversies, disappointing in neither. The particular glory of London’s hosting was the amplification of its own immense multiculturalism, and for one spotlit summer it held itself up to nature as the leading representative microcosm that it is. The structure of the festival was designed somewhat to enhance this effect; visiting companies were partly selected by what Festival Director Tom Bird called ‘London languages’: those that are widely spoken throughout the city. Each company varyingly brought out fellow speakers from the woodwork in a constant linguistic revolve ensuring that everyone played to crowds who both could and could not understand what was being spoken. A geographic balance was further sought to represent productions from six continents as equally as possible.

Various conventions affected everyone: subtitling (though only of short scene synopses) in two boxes far stage right and left; an allowance of recorded music if they wished – a rare embrace of amplified audio at that time in the Globe; access to Globe Associates of Voice, Text, and Movement; and a mere three days to rehearse once and perform twice. They all performed rain or shine, saw as many other productions as they could, socialized at the bar, and fully soaked in their extraordinary moment. There is a densely littered trail of press and publications detailing each production and its unique context in the festival, but although the current state of international Shakespeare performance was (through the Globe darkly) on acrobatic display, few writers have surveyed the festival as a whole.

In freely comparing the various musical approaches at play, it feels just barely possible to glimpse the state of music in Shakespeare internationally – from 1991, the birth of its oldest production, to those newly produced for the festival twenty years later. My method was to review the entire archive (I had seen sixteen of the thirty-eight shows live), and catalogue each production by certain metrics of musical approach: number of musicians, recorded music or live, musical genre, musicians’ positions onstage, and whether the production predated the festival. I particularly noted scores comprised of traditional musical styles native to their respective countries, as well as freely adapted productions that brought music into moments in the plays that typically go without. Adaptation was the most common sponsor of musical ingenuity; often the greater the freedom taken in translation, the more radical the production’s reconceptualisation of the story. In each instance these reforged versions left fresh creative spaces inviting music to assert itself and take a more substantial role in the narrative.

Those curious to see or relive the immense cultural exchange that took part in the early summer of 2012 have several options that all contributed to this chapter. There are first and foremost the productions themselves available on the Globe’s online Globe Player. There is the informative collection of essays entitled Shakespeare Beyond English; A Global Experiment (Cambridge), edited by Susan Bennett and Christie Carson. Finally there is a host of online reviews, features, and interviews chronicling Globe-to-Globe’s crowning of the World Shakespeare Festival and discussing the many ethnic pockets of London that resonated with it. As an introduction to the field, the thirty-eight productions can be roughly grouped into five families of musical approach. First, there are the through-composed productions that relied on music practically throughout, including Isango Ensemble’s operatic Venus and Adonis from Cape Town, Deafinitely Theatre Company’s Love’s Labours Lost in British Sign Language, and Q Brothers’ Hip-hop Othello from Chicago. Second are productions with an incidental musical score directly inspired by traditions native to their company’s countries: the Māori Troilus and Cressida, South Korean A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Gujarat All’s Well That Ends Well, Henry IV pt 1 from Mexico City, the Armenian King John, and the Globe’s own Henry V. A third category comprises productions that used only recorded sound and were mostly built for indoor theatre runs at home: Vakhtangov Theatre’s Measure for Measure, the Italian Julius Caesar, German Timon of Athens, Polish Macbeth, Palestinian Richard II, and director Eimuntas Nekrošius’ iconic Hamlet from Lithuania (on tour since 1997). The fourth are productions that featured strikingly little sound and music at all including the Kenyan Merry Wives of Windsor, Argentine Henry IV pt II, and South Sudan’s Cymbeline. A fifth category includes productions that for exciting reasons fail to sit naturally in any of the former groupings: the exiled Belarus Free Theatre’s King Lear and Grupo Galpão’s circus-inspired Romeo & Juliet from Brazil.

Shakespeare, Music and Performance (Cambridge University Press) is now available to buy.

Watch filmed Globe stage productions on Globe Player.

31 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Moving Friday night in Brooklyn. Amazing music and vibes with "A Man of Good Hope," a Somali refugee's tale told through music, dance and stories that lift the soul. "The road is long. My will might break. But we all choose the path we take." Great show to kickoff a long weekend. Standing O for the Isango Ensemble | BAM, BK #isangoensemble #👏 #brooklynacademyofmusic #brooklyn #nyc #blackandwhitephotography #selectivecolor #streetphotography #theatre #🎭 #365daysprojectjp [48/365] (at BAM)

#🎭#isangoensemble#365daysprojectjp#👏#streetphotography#nyc#brooklynacademyofmusic#blackandwhitephotography#brooklyn#selectivecolor#theatre

1 note

·

View note

Text

iVisit.... Royal Opera House Productions

Royal Opera House Productions: 8 April – 8 May 2019

Main Stage

La forza del destino, selected dates to Monday 22 April 2019

Christof Loy directs a star-studded cast of singers, including Anna Netrebko, Jonas Kaufmann and Ludovic Tézier, in Verdi's epic opera, conducted by Antonio Pappano.

https://www.roh.org.uk/productions/la-forza-del-destino-by-christof-loy-

Images available here: https://we.tl/t-60keOi8O4w

Romeo and Juliet, selected dates to Tuesday 11 June 2019

Kenneth MacMillan’s acclaimed production returns to the Royal Opera House, with music by Sergey Prokofiev and a number of exciting debuts from across The Royal Ballet. Also available in cinemas and free around the UK on the BP Big Screens on Tuesday 11 June, with an encore cinema screening on Sunday 15 June.

https://www.roh.org.uk/productions/romeo-and-juliet-by-kenneth-macmillan

Images available here: https://we.tl/t-UG1v4c10xF

Faust, Thursday 11 April – Monday 6 May 2019

Gounod's most popular opera returns in David McVicar's stunning Parisian production, with singers including Michael Fabiano, Diana Damrau and Erwin Schrott. Also available in cinemas on Tuesday 30 April with an encore screening on Sunday 5 May.

https://www.roh.org.uk/productions/faust-by-david-mcvicar

Images available here: https://we.tl/t-C3siX9Rpw1

Billy Budd, Tuesday 23 April – Friday 10 May 2019

Deborah Warner stages the first production of Britten's all-male opera at Covent Garden for nearly two decades, with Jacques Imbrailo, Toby Spence and Brindley Sherratt in the lead roles.

https://www.roh.org.uk/productions/billy-budd-by-deborah-warner

Images available here: https://we.tl/t-9IVpC9UJSY

Within the Golden Hour/ Medusa / Flight Pattern

A contemporary triple bill showcases revivals of works by Christopher Wheeldon and Crystal Pite, alongside the world premiere of Medusa by Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui.

https://www.roh.org.uk/mixed-programmes/within-the-golden-hour-new-sidi-larbi-cherkaoui-flight-pattern

Images available here: https://we.tl/t-rdmSsTTbFl

Linbury Theatre

Juliet and Romeo, Saturday 13 April – Sunday 14 April 2019

Through dance, theatre and comedy, innovative theatre company Lost Dog tell the story of Shakespeare’s young lovers – if they hadn’t died in a tragic misunderstanding but lived not-so-happily ever after.

https://www.roh.org.uk/productions/juliet-and-romeo-by-ben-duke

Images available here: https://we.tl/t-q7kSy5uCh7

A Man of Good Hope, Tuesday 16 April – Saturday 4 May 2019

The true story of a young refugee’s journey through Africa told through music, singing and dance, based on the book by Jonny Steinberg. Performed by Isango Ensemble.

https://www.roh.org.uk/productions/a-man-of-good-hope-by-mark-dornford-may

Images available here: https://we.tl/t-CxNODe0hOR

SS Mendi: Dancing the Drill of Death, Thursday 18 April – Saturday 4 May 2019

Award-winning South African lyric theatre company Isango Ensemble re-tell the story of a real-life, tragic maritime disaster, based on the book by Fred Khumalo.

https://www.roh.org.uk/productions/ss-mendi-dancing-the-death-drill-by-mark-dornford-may

Friday Rush Friday Rush is a great way to get last-minute tickets for the Royal Opera House at a range of prices - even for sold-out shows. At 1pm every Friday, 49 Friday Rush tickets for almost all main stage shows performed by The Royal Opera and The Royal Ballet in the following week are available to purchase online: https://www.roh.org.uk/events/friday-rush

0 notes

Text

A theatre ensemble in Isango, South Africa, tells western stories through African art from CNN.com - RSS Channel - World A theatre ensemble in Isango, South Africa, tells western stories through African art via IFTTT

0 notes

Text

Countdown to Tiger Bay the Musical

Tiger Bay the Musical

Sublime music, gripping story, outstanding international creative team and a star-studded cast – that’s Tiger Bay the Musical.

This marks the final leg of an epic journey for Michael Williams, the managing director of Cape Town Opera, who wrote the book and lyrics for Tiger Bay the Musical. Williams says: “The two-year journey of creating characters in my imagination now takes on a three-dimensional reality as a wonderful cast brings these characters to life. And finally, we will hear composer Daf James’ sparkling score leap from the page in all its glorious harmony!”

Leading the creative team, acclaimed director Melly Still is perfectly suited to tackling a family musical that explores gritty topics such as child labour, sexual equality and mixed race marriage. Still has worked as a director, choreographer, designer and adaptor for many companies including the National Theatre of Great Britain, the Royal Shakespeare Company and Glyndebourne Festival Opera. Most recently, Still directed the epic tetralogy of Neapolitan novels by Elena Ferrante, My Brilliant Friend, at the Rose Theatre – a celebrated five-hour event in the London theatre calendar.

Luvo Tamba

Ensuring that Tiger Bay the Musical has all the right moves is choreographer Kenneth Tharp OBE. Tharp has extensive experience in leading cross-disciplinary collaboration in the fields of dance, music and opera. As well as 25 years as a professional dancer, Tharp has choreographed more than 40 works, including the large-scale community opera Heroes Don’t Dance for London’s Royal Opera House.

In 2003, Tharp was made an OBE in recognition of his services to dance.

Designer Anna Fleischle’s superb credentials include numerous awards for the design of Martin McDonagh’s Hangmen at the Royal Court and subsequently in the West End. She won the Critics’ Circle Award 2015, the Evening Standard Award for Best Design 2015 and an Olivier Award for Best Set Design.

Leading the star-studded cast is Broadway musical sensation John Owen-Jones, who, with more than 2,000 performances in the role, is well known as the Phantom in Andrew Lloyd Webber’s Phantom of the Opera.

Judy Ditchfield

Cast alongside him is Vikki Bebb, a graduate of the Royal Welsh College of Music and Drama. As well as a fantastic voice and acting talent, Bebb lends an authenticity to the role as she was born and raised in the Cynon Valley, like the fictional character she portrays.

The story of Tiger Bay the Musical is set in motion when a Zulu man, Themba, arrives in Tiger Bay seeking revenge for the horrific murder of his family in the Boer War. Playing this role is South African Luvo Tamba who recently drew widespread acclaim for his performance in the Isango Ensemble’s adaptation of Jonny Steinberg’s A Man of Good Hope.

Kenneth Tharp

Playing the roguish heart-throb Seamus O’Rourke is Noel Sullivan, a founding member of the pop group Hear’Say. Sullivan turned to musical theatre after the group disbanded, appearing in productions such as Fame, Love Shack and What a Feeling. He also performed the role of Danny Zuko in Grease at the Jersey Opera House.

Much-loved South African actress Judy Ditchfield — acclaimed for performances in Stander (2003), Faith’s Corner (2005) and u’Bejani (1997) — portrays a medium who channels the dead.

Tiger Bay the Musical offers fans of musical theatre the rare opportunity to attend opening performances of a large-scale new musical in Cape Town. Tiger bay the Musical will have a short run at Artscape from May 20-27 before transferring to the UK in late 2017.

Book now:

Until Sunday, April 9, you will get a 25% discount for the best seats in the house.

That means you will only pay R300 for seats that are normally priced at R400 — a saving of R100.

This special offer is limited to a maximum of four tickets per person.

To secure your early bird discounted seats, simply book through Computicket under the discount Early Bird Online, using the booking code EBS123.

Countdown to Tiger Bay the Musical was originally published on Artsvark

0 notes

Text

‘A Man of Good Hope,’ a Refugee Tale for the Moment

Ian Bagley's New Blog Post

This musical drama, opening at the Brooklyn Academy of Music on Feb. 15, is a production of the Young Vic and the South African Isango Ensemble.

from NYT > Arts http://ift.tt/2kTccoh

via WordPress http://ift.tt/2kTd1xA

0 notes

Note

Fictional Character Ask: Mercedes and Frasquita??

Carmen's two companions

Favorite thing about them: Well, they're lively and likable characters, and I like that they're true friends to Carmen, who never view her as a rival despite her allure and popularity with men, and who try (however vainly) to protect her from Don José.

Least favorite thing about them: That they can be viewed as negative stereotypes of Romani women, being involved in crime and using their sexuality to aid the smugglers.

Three things I have in common with them:

*I enjoy dancing and singing.

*I sometimes read oracle cards.

*I would love to find romance and/or be rich someday.

Three things I don't have in common with them:

*I'm not involved in smuggling.

*I'm not nearly as confident in my charms and allure as they are.

*Unlike Frasquita, I would never marry an elderly man for his money.

Favorite line: Their passages in the Card Trio.

brOTP: Each other and Carmen.

OTP: The famous captain and the rich old man whom the cards foretell for them in the future.

nOTP: Don José. He's wrong for Carmen and would have been wrong for them too.

Random headcanon: The happy futures the cards foretell for them will come true. Mercédès will have her thrilling romance and Frasquita will have her fabulous wealth. I know there's reason to doubt it, and I've read the argument that they don't even believe it themselves and are just joking together in the card scene, with only Carmen really believing her destiny. But I want the best for them, so I'll have faith that the cards really do never lie.

Unpopular opinion: I wish more productions would bring them back onstage at the end to react to Carmen's murder. In fact, instead of ending with Don José grieving over Carmen's body, I wish more productions would end with them grieving over her body while José is arrested. So far I've only seen two productions do this, the 1984 Francesco Rosi film and the Isango Ensemble's South African-flavored production. But I remember reading somewhere (I wish I remembered where) that the first draft of the libretto ended this way. I wish that staging would be brought back more often. Enough of ending with "Poor José, he killed the one he loved!" Let Carmen be mourned by the friends who really loved her for who she was, not just by the man who killed her for refusing to be the fantasy he was obsessed with!

Song I associate with them:

"Nous avons en tête une affaire"

youtube

"Melons! Coupons!" (The Card Trio)

youtube

Favorite pictures of them:

I don't know who any of these singers are, but I like the pictures.

#character ask#opera#carmen#mercedes and frasquita#georges bizet#ask game#fictional characters#tw: murder

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Are you ready to be riveted? Award-winning South African theatre company Isango Ensemble brings the resiliency of humanity to life in the captivating production of “A Man of Good Hope” at the #StLawrenceCentreForTheArts.

Wana win 2 tickets? Click the link below to learn how!

https://byblacks.com/main-menu-mobile/contest-mobile/item/2380-win-2-tickets-to-isango-ensemble-at-the-st-lawrence-centre-for-the-arts

0 notes

Photo

‘A Man of Good Hope,’ a Refugee Tale for the Moment By @STEVEN McELROY Author #Theater #Theater #BREAKING #TRENDING #UK #USA #news This musical drama, opening at the Brooklyn Academy of Music on Feb. 15, is a production of the Young Vic and the South African Isango Ensemble. from NYT The New York Times

0 notes

Link

This musical drama, opening at the Brooklyn Academy of Music on Feb. 15, is a production of the Young Vic and the South African Isango Ensemble.

0 notes

Photo

Moving Friday night in Brooklyn. Amazing music and vibes with "A Man of Good Hope," a Somali refugee's tale told through music, dance and stories that lift the soul. "The road is long. My will might break. But we all choose the path we take." Great show to kickoff a long weekend. Standing O for the Isango Ensemble | BAM, BK #isangoensemble #brooklynacademyofmusic #blackandwhitephotography #selectivecolor #theatre #🎭 #365daysprojectjp [48/365] (at BAM)

#selectivecolor#🎭#theatre#blackandwhitephotography#isangoensemble#365daysprojectjp#brooklynacademyofmusic

1 note

·

View note