#is ken becoming the ultimate antagonist?

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

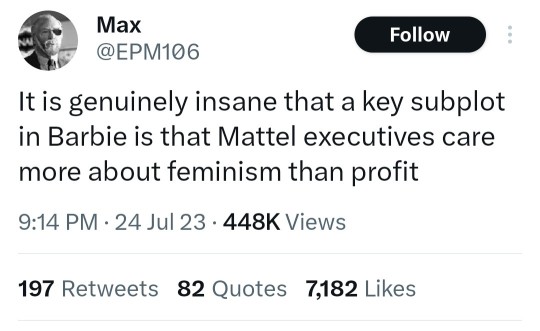

Text

The Barbie Movie is confused -- and it is confused on purpose, because it can't actually acknowledge the role that capitalism and white supremacy play in the patriarchal system that it wants to give itself credit for acknowledging. And so the film introduces patriarchy as a force with no agent or system behind it.

Ken, an oafish goof is able to find the concept of patriarchy and transmit it to the entirety of his society simply by learning about it and speaking about it to his fellow Kens. There is no use of force, no political organizing (notably, the Kens try to take over the political system after they have already taken hold of the culture), no real persuasion even -- simply by hearing about patriarchy the women in Barbieworld somehow become brainwashed by it.

This means we never have to really see the Kens as genuine antagonists, we can still laugh at their bizarrely crammed-together multiple dance numbers and forgive them when they, like the women, are freed of the patriarchy simply by women speaking about the fact that sexism exists. Both the origins of patriarchy and the solution to it is as simple as an individual person telling their story.

The CEOs that run Mattel in the Real World in the film are similarly cartoonish and devoid of real agency. They're even portrayed as generically interested in the idea of Barbie being inspiring to girls. The movie can't even acknowledge their profit motive, and it can't make any of the men running the company look too powerful or even too morally suspect -- but the film does still want to have Barbie encounter sexism in the real world and grapple with the harm "she" (the consumer product, and not the social forces and human beings that created her) has supposedly done.

In the Barbie Movie, patriarchy is a genie in a bottle, and no one is to blame - except maybe Barbie herself, since the movie spends a significant amount of time discussing how she is responsible for giving women unrealistic beauty standards.

And so Barbie is depicted as both sexism's victim and sexism's fault. She's dropped into a patriarchal world that the film acknowledges has a menacing, condescending quality -- but the film can't even have an underlying working theory of where this danger comes from, and who had the power to create this patriarchy in the first place, because that would require being critical of Mattel and capitalism.

And in the film, ultimately the real world with all its flaws and losses and injustices is still preferable to Barbieworld, because you get to have such depth of feeling and experience and you get a vagina, so how bad could really be? And hey, when you think about it, the Barbieworld is just an inversion of the real world, isn't it? A world with women in power is just reverse sexist, so it was justifiable for the Kens to want to take over, and what does it say that all things being equal Barbie still would prefer to leave behind her matriarchy and join the patriarchal capitalist world? That's the real world. Real world is struggle and sexism and loss and pain and capitalism and death and we must accept all of it but it's worth it..

It's not that I'm surprised the film's a clarion call for personal choice white feminism and consumer capitalism. I just expected the call to be a little more seductive or in any way coherent. I wanted to have frothy fun, and instead I was more horrified by the transparency of its manipulation than I was by even the most unsettling moments in Oppenheimer.

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

WELCOME

TO THE FIRST ROUND OF THE COPAGANDA CLOBBERFEST!

“You know that trope? That one trope *Everyone* hates? The trope in which a well meaning antagonist to our heroes, one looking out for the good of a certain community, suddenly does something horrible and drastic to make not only them, but the ideology they stand for the most villainous of all?”

NOW IS THE TIME TO BATTLE THEM OUT! Like Ken dolls, fighting for survival! Like your Polly pockets discarded in the closet, we’ll see which of these bitches jumped that slippery slope harder! Whose character did numbers on y’all, and blew up a bunch of grandmas and babies and hospitals with it!

ROUND ONE

DAENERYS TARGARYEN from GAME OF THRONES vs PRINCE LOTOR from VOLTRON (LEGENDARY DEFENDER)

Dany propaganda (TW: domestic abuse mention, slavery):

“Sold off as a slavewife to a warlord in another country. Slowly rises up gaining the love and trust of the warlords people, eventually becoming their leader after his death. Goes on to conquer another nation and free all the slaves. Deals with her quickly growing list of real and perceived enemies in increasingly awful ways. More stuff happens. Eventually she makes her play for the throne of Kingslanding and forced a swift surrender… but instead snaps… over…? and instead starts killing everyone in the city indiscriminately because the only way to build her great version of the world everyone who even remotely likes the current one has to die.

And then her sorta bf kills her.

Its kinda funny how the US was also founded on a revolution lead by people with Not Great Morals and its media industry loves to now churn out stories where revolutionary figures turn out to be bad guys, actually, so you shouldn’t revolt and just accept your place in their world. Is this actually a British psy-op to get americans to accept the error in the ways and rejoin the UK?”

“daenerys propaganda: the literal in-text justification d&d gave for dany always being secretly evil and destined to massacre innocents was that she was too mean to the slavers that crucified a bunch of children. so they had this domestic violence survivor die of yet more domestic violence. they couldn't even let her go down in battle, she had to be assassinated by her lover in a moment of physical intimacy. (and tyrion, who literally strangled his gf to death and burned a fleet alive, suddenly became the audience avatar fretting about ethics.) the only woman permitted to retain power at the end of the show (sansa) was the one who said being raped and abused made her strong; dany, who explicitly condemned physical and sexual abuse and took steps to eradicate the perpetrators and break the wheel that crushed the oppressed, had to go crazy and die. the script explicitly condemned what they referred to as "liberation theology." d&d are the ultimate centrists and they turned dany into a fox news caricature of an activist.”

Lotor propaganda (TW: xenophobia):

“He wasn't exactly presented as a straight-up villain initially, more like a rogue agent. He wanted to reform his father's evil empire to be less tyrannical and xenophobic (the 2nd one is especially relevant because he's only half Galra. He went from an enemy of the heroes to an ally, then oops! turns out he's actually been a genocidal mass murderer with a god complex this whole time and then he dies in the most horrible way. It's been a while since I watched the show but I will never stop being mad over how they did my boy dirty.”

Always feel free to rb with more propaganda :)

#copaganda clobberfest#copaganda-clobberfest#polls#tumblr polls#tumblr tournament#poll tournament#game of thrones#daenerys targaryen#prince lotor#voltron legendary defender#vld

75 notes

·

View notes

Text

took my time with it, but kaleidostar was a nice fun ride.

my only problem with it honestly was Fool's perverted tendencies and Rosetta.

like, I guess I wouldn't have minded Rosetta as the tsundere genius that gets shown up and becomes friendly with the MC, but im getting vibes from the creators about her and it makes me uncomfortable. also, i really just don't care about her as a character, i dont really even want to watch that final "episode 52", im just not interested

i honestly was expecting to hate everything about May, but the moment she was shouting her moves (AND BARKING LIKE A DOG??), i knew I couldn't hate her. I liked her growth and her maturing and reaching out to rosetta as fellow rivals to Sora

I love the dynamics that the guy partners brought to the table, because at the end of the day, they really were extras and Sora and Layla really were the stars of the show.

I really like how Yuri was written as The Partner of the Famed Layla, and was a pretty chill guy until he reveals his plan and becomes the antagonist in the first part. The way he comes back in the second part, only to have another crazy reveal, but then backs down again. Yuri’s character was a rollercoaster but not once was he delegated to any romantic/love interest. Sure there was a couple of scenes of him and Layla “looking like the perfect couple” and something scandalous when he was trying to recruit Sora during Part 1, but he was never actually a romantic interest. (Aside from Ken feeling jealous.)

Same with Leon, when May was also fighting Sora to be his partner, it was about their pride as performers and never about Getting With the Guy. (There was also that uncomfortable scene with Leon seeing Sophie in Sora but uhhhh) I like that they revealed Leon’s only partner was his sister, so when he sees Sophie in Sora, it doesn’t come off as strangely romantic. I mean, Leon and Sora could be a ship but we all know the girlies stay winning.

Uhhh I have nothing against Ken, he does his job brilliantly, but I wish his crush on Sora wasn’t used a gag too much. I mean once in a while is fine, but I felt like it was a joke too often. I’m glad there wasn’t an actual confession and that he could still see her as a friend and someone he wants to support.

I dont have huge passionate words towards Layla and Sora, but the girlies are so very important to eac hother. (Me being ABSOLUTLY BETRAYED when Layla said Cathy was her new partner.) NGL I thought they being able to perform the Ultimate Move in the first part felt so rushed, not that it actually was, but I was like, if they do this in the first half, whats going to happen in the second half. Also the way Sora found out Layla could no longer perform, starts crying, Layla tells her to stop crying and she did, that entire scene felt like it was at 2x speed. (That Digimon Dub moment where the kid tells the other kid to “get over it”, and then he does.)

Sora’s had her ups and downs as a character, I feel like she’s “ran away” way too many times (Don’t Lose Your Way Matoi Ryoko who Loses Her Way Twice in the entire series). The few early ones just felt like they were there for dramatics and I really felt like Kalos shouldn’t have given her all those chances. The only one I really liked was after the Circus Festival when she realized what kind of stage she didn’t want to perform in and was given the devastated “Im disappointed in you” by Layla. Anyway, I’m so happy for Sora, but I don’t think we’ve ever actually seen her perform in the iconic Phoenix outfit in the ending previews? (The one with the orange stripes and fluff?)

Anyway whatever, the art and animation is gorgeous, and so is the music. I’m glad it got the 51 episodes that it did, if it was a Today series, with the first part being 12/13 and maybe New Wings being another 12/13, I probably wouldn’t have been as impressed. Sure they could have cut out a lot of character focused eps (Anna’s father, Marion, Sara and Kalos, etc) or training montages, I don’t think the series would have stuck with me as much.

1 note

·

View note

Text

So Belial Vamdemon. Or as the fandom calls it Marshmalomyotismon.

"Belial" means worthless in Semitic languages, and the demon it refers to has multiple different characterisations. So literally, Belial Vamdemon is Worthless Vampire Demon Monster. Rather unintentionally appropriate.

His parasites, Sodom & Gomorrah, apparently reference the fact that Belial is thought to be the one who brought immorality to those cities, but this is only referenced in one of SMT blurbs, I can't find the original source of this idea.

Belial Vamdemon is one of the lesser Demon Lord Digimon. One of the others is Deathmon, from V-Tamer manga, which is later repurposed as the pseudo-canonical final form of Fantomon, Vamdemon's right-hand man in Odaiba arc in OG Adventure. It is likely that these lesser Demon Lords will get their own sigils in the future.

Neither Belial Vamdemon, nor Belial in SMT are accurate to the Ars Goetia depiction, they are based off the Jewish depictions of the demon.

Belial is described to be the second demon created after Lucifer in Ars Goetia, as such it tends to be a high ranking demon in SMT, albeit after many others. Belial in early SMT games would be showcased in opposition to Metatron (hence the official art of them fighting), though in later games Metatron was significantly ranked up.

Belial Vamdemon is interesting because of the fact that Vamdemon's natural line is mostly based off Undead Digimon, whereas Belial Vamdemon takes the Demon Digimon part of the line.

Belial's association with Sodom & Gomorrah is somewhat amusing considering the ambigious nature of Oikawa & Hiroki's relationship, feel free to read into that.

Belial Vamdemon's design features many insectoid features, which makes one wonder if the original intention was for it to absorb Mummymon & Archnemon to reconstruct itself. This will likely become a plot point in a 02 reboot.

Vamdemon being the final boss doesn't work very well, especially considering 02 already had two unresolved antagonists that are stronger than it (Dagomon, or at its hypothetical final form, and Demon). Thematically, it only works somewhat.

Vamdemon was the villain of Daisuke's, and Hikari's childhood, and indirectly connected to various elements of the rest of the cast. Vamdemon was the one that helped Ken developed Evil Rings through Tailmon's Holy Ring (again, not properly expanded upon), and was part of Piemon's Nightmare Soldiers like Devimon (though this is only something one can infer through V-Pets, or learn from the novelisation), and would later become Piemon's Jogress partner, thus giving the Takeru connection. He is not directly connected to Iori beyond Oikawa, and has no connection to Miyako, though.

Vamdemon also works somewhat due to being a literal manifestation of children's nightmares, due to being a Dark Digimon created out of children's views of vampires, but also due to events of both Adventure series. This reconstructed body is also ultimately powered by the fear of children, with the help of copied Millenniumon pieces that are the Dark Seeds. Even then, these justify Vamdemon being a major villain, not the final boss.

(It would have been probably more thematically appropriate if the cast defeated Vamdemon with other Digimental Evolutions, including the Golden Digimentals, and Kindness, but that opportunity wasn't used either.)

Neither of these two aspects are really developed in the series proper, though. Vamdemon being Daisuke's tormentor should have been played up probably, but Miyako isn't involved in the Diablomon movie really, so this isn't the lost opportunity of 02 with the returning antagonists.

0 notes

Text

Guys, it’s literally possible to care about more than one thing. He does sincerely care about making little girls dreams come true over profits, like we see when he doesn’t want to sell the Mojo Dojo Casa Houses even though they’re immediately making a crap ton of money. He really does mean well.

But meaning well isn’t always enough because even though he means well he refuses to see his own hypocrisy and how surface level and meaningless his feminism efforts ultimately are. He’s the kind of guy who insists on giving women a voice without actually listening to what women actually want to say and just assumes he knows. He honestly believes he’s the good guy and is trying his best to be a good guy. He’s just ignorant and is as much a victim of the patriarchy as the Kens who take over Barbieland but end up being miserable and the worst versions of themselves before the Barbies take back Barbieland. His main fault is ignorance and I think it’s up to the audience to decide to what degree his ignorance is willful and malicious. This guy is part of the reason why the messages in Barbie is so simple, because nowadays most misogynists look more like him than the ones who are outright hostile (in my personal experience at least) and one of the things this movie does is serve as a wake up call to these guys so that they can maybe have the realization that ‘hey, maybe I’m part of the problem without realizing it. Maybe I should take this opportunity for some self-reflection.’ He’s an antagonist, but he’s not a villain. The only villain in this movie are systems that encourages inequality and oppression in all its forms. Unless you want to count the fact that Will Ferrell’s character is a CEO of a major company as enough reason to consider him a villain.

But speaking of him being a CEO, of course he also cares about profits. He wouldn’t have become a CEO if he didn’t care about profits. I personally choose to believe that for this character specifically he cares just as much about his company preforming well and the quality of their products as he does about his own personal gain. When he listens to Gloria give her pitch it does show the small amount of progress he’s had over the course of the movie in that he actually listens to her, but when he dismisses her idea it shows both that he has more room to grow as well as his business man side. (Ngl, I didn’t blame him for dismissing her pitch at first. I’m no expert on business and economics and all that, but her pitch was really vague and I had absolutely no idea what the doll she was envisioning could possibly look like or be advertised. The best reaction his business man side would have allowed was suggesting she take some time to put together a better pitch for him to listen to another time). The facts that he genuinely cares about making the dreams of little girls come true in the most shallow and ignorant way possible and that he’s also a slimy business man wanting his company to be successful co-exist.

To sum up, he cares more about feminism than profits when the profits are obviously and egregiously getting in the way of feminism and is threatening to change the whole direction of the entire company, but cares more about profits than feminism when the question is about whether or not to put a new product on the shelves based on a vague concept for a new doll when the company is already devoted to feminism and he’s just committed to do better.

He is part of the problem, but he also wants to be part of the solution and was eventually willing to see that he could do better and commit to doing so. I think it’s very purposefully up to the audience’s interpretation over how successful those efforts to do better actually will be.

Even with all of his exaggerated characteristics, he’s one of the most realistic characters in the whole movie. He is literally just like most of the guys I’ve met in college. Here’s hoping Will Ferrell’s character and all of the irl people he’s based on will take some time to self-reflect and listen to what women are actually saying and take the appropriate steps towards becoming better.

8K notes

·

View notes

Note

Of the three Roy siblings (sorry we don’t count Connor), which would you say is Cordelia (from Lear)? I keep thinking it’s Roman

Roman is crazy as a choice here bc it was originally Ken like quite purposefully I think but atp i agree it becomes/became Rome but also I posit (if we stick with the Lear lens that s1 set up) ARENT THEY ALL CORDELIA BY THE END? You know? I see me and I see you but I also see shiv. I think it’s cool that the tragic figures keep shifting and also I think the cordelias unionized. Like I think the great lie at the center of Lear is they’re all different bc if they’d all talked to each other they’d all be Cordelia. Bc Jesse Armstrong grabbed onto lear not just as like cordelias antagonist but the enemy of all the children ultimately bc he SET UP A SITUATION THAT TOXIC IN THE FIRST PLACE. Like successions take on Lear at its most basic is like hey actually what the fuck kind of household did you grow up in that your dad is asking who loves him more? What the fuck kind of environment is that? So now what I’m saying is yes Rome is Cordelia yes Ken was Cordelia yes shiv crying like that? Cordelia. Jesse just like took his copy of the play and cracked the spine. Which he is also invited to do to m

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Before moving on to Revenge of Diablomon, I need to get this out.

I did not remember Oikawa at all from when I was a kid. I remembered Arachnemon and Arachnemon's Sidekick (but not Mummymon in particular). and I remembered Vamdemon as the ultimate villain, but Oikawa totally slipped my mind.

When Oikawa first came on the scene, I kinda just thought he was Vamdemon in a human guise. Like, evil Digimon in a trenchcoat, not unlike how Arachnemon and Mummymon present when not in their combat forms. Or a human directly possessed by Vamdemon, such that his persona is more Vamdemon than Oikawa. In my defense, he has the face of an undead monster.

This is not the case. Oikawa is his own character, and he's the one who ultimately drives the plot for the whole series. The Man Behind the Man Behind the Digimon Kaiser. Vamdemon is involved, but his influence is vague and poorly defined. He basically just comes in at the end to hijack the plot and give everyone a final boss to fight.

Villain-wise, this is Oikawa's show much moreso than Vamdemon's. And honestly, Oikawa is a pretty good villain! I wish I'd given him the credit he was due back in the day, but I must have been so Mind Blown by Vamdemon's return.

Oikawa wants to be a Chosen Child. That's his whole thing. He wants for himself and his best bro Hiroki to have had Digimon partners and gone on adventures in the Digital World when they were young. But he didn't get to have that so he stormed off and made his own Digimon with blackjack and hookers.

And that's really interesting. BlackWarGreymon gives Arachnemon and Mummymon a brief existential crisis when he points out that they're neither Digimon nor human. I kinda wish that had been explored more?

Because. Like. There's an answer to it that the show never explores, and it's honestly kinda fascinating. They were created from Oikawa's genome, right? Well, Digimon Partners are created from data scanned from the children they're partnered to during those times when those kids encountered Digimon.

Agumon was created from Taichi's data when he and Hikari first witnessed a Greymon fighting a Parrotmon all those years ago. That's how you become a Chosen Child. The Digital World scans you and then it makes a Digivice and a Digimon Partner for you. This was a plot point in the first series.

So if Partner Digimon are already created from data scanned from their partners, then is Arachnemon and Mummymon's situation really so unique? The pair of them are just Partner Digimon created by Oikawa instead of by the Digital World's natural process.

This is really cool, and echoes Ken's attempt to fabricate his own "better" Partner Digimon in Chimeramon. Except with Ken, it was an act of dismissive cruelty towards Wormmon. With Oikawa, it's colored by a tinge of sadness.

Oikawa made two Partner Digimon. Of course he made two. One of them's for Hiroki.

This is such a good character. Adventure 02 really is defined by its human antagonists, Ken and Oikawa. To the point that it makes the brief times that the kids fight evil Digimon feel kinda tacked on by extension.

Except you, BlackWarGreymon. You get a gold star. Though the Holy Stones plotline does reek of "We need some excuse for the kids to fight BWG so I guess this will work."

But Oikawa is fantastic, and my only complaint is honestly the same one I had for Ken: This was a great idea, and I wish there was more of it.

Oikawa deserves to be remembered as the true antagonist of Adventure 02, much moreso than Vamdemon.

#digimon#digimon adventure#digimon adventure 02#yukio oikawa#oikawa yukio#arachnemon#arukenimon#mummymon

22 notes

·

View notes

Note

How do you think the casts of other Digimon series would react to having to deal with Kurata as a villain? His method of permanently killing Digimon would be a terrifying and potentially traumatic threat.

Short answer is not well. In Nexusworld, a Gizumon showed up, another entity took its permakill powers and... well, permakilled a partner Digimon. It was a right shock to everybody’s systems, particularly the victim and a couple of those who suffered close calls.

Group by group, it really depends on their relationship with perma-kill situations and human villains:

The Adventure team (either one) will be mortified by the implications, since Angemon died relatively early in their campaign and they came to appreciate Digimon rebirth, perhaps even taking it for granted at times. While the reboot crew would be stunned by Kurata, the 1999 gang might just be a little disgusted having faced vaguely humanoid villains in Vamdemon and Piemon. Kurata's not much more human than them, really.

Other than Takeru (and Ken in a very personal, isolated way), the Zero Two team hasn't relied on rebirth nearly as much, and has had to deal with *two* human villains in the Kaiser and Oikawa. Their mettle will hold a lot better. The question with them is how soon they recognize that, unlike Ken and Oikawa, Kurata is beyond redemption?

Tamers never had the luxury of rebirth and get that Yamaki's a knife's edge away from being an antagonist. They're not fazed by what this guy brings to the table and they're up for a fight. Bonus points for sneaking a Kurata/Yamaki brawl in there. Wait, better: Kurata/Reika.

The Frontier kids didn't come to appreciate rebirth until late in the season, when they stumbled on the Village of Beginnings and acquired the baby forms of all three angels. Their fury towards Kurata goes up a ton after experiencing those. Aside from that, they're extra ticked off at Kurata forcing test subjects to become Digimon and they'll be extra careful to take care of the Bio-Hybrids once they're beaten.

Xros Wars is tricky because both of the elements that make Kurata so intimidating are kinda-but-not-quite already there. Villainous Digimon are responsible for handing out three (3) of the four Xros Loaders in the main series, and not only is Yuu openly antagonistic, Nene and Kiriha have their moments too. The right to rebirth is one of the things Bagramon and Shoutmon are fighting over, so the presence of Gizamon should only underscore Shoutmon's cause.

At the risk of having the Unryuji Knight Appreciation Squad come at me, Appmon had this scenario. Knight certainly has more personality and a tragic backstory to lean on, but he's still winning over the right people to help the villains defeat the good guys. And the Ultimate Four do take out the Appmon and the drivers temporarily believe it's for keeps. Granted their emotional reaction to all that was... strong. So maybe Kurata will be overwhelming, but they'll step up.

Too early to say anything for Ghost Game at this point, but I'm going to mention them just because they'll get to be part of this kind of discourse now and I'm excited for them!

Want to support my site and/or my work? Buy me a coffee!

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

@rhythmic-idealist said:

I’m gonna do my best to come back to this! A short response: the Iida family didn’t need Stain killed. Rather, Tenya needed saving, in that his villainous actions were also going to get him killed. Tenya is deemed worthy of saving, by the narrative, regardless of the fact that he was making horrible rage-fueled decisions. So that’s what I’m getting at when I say Tenya needed saving- he very much was going to die if Izuku hadn’t shown up in that alley. I am still trying to process why he was saved when Tenko and Himiko (and mostly Touya) weren’t, because BEFORE we knew the ending, the hero killer arc felt like a tone setter- you either have to condemn Tenya Iida to deserving to die, or believe Tenko and Himiko and Touya deserve to live. Final half-response before I formulate proper thoughts for later (sorry): one of my main BNHA ending thoughts involves how I sort of expected it to be pointing out and handling privilege and the “way things are” in order to suggest ways to actually upend that imbalance in privilege. Analysis I do of the ending often revolves around…. this seems like a story about privilege happening in the way that privilege happens, so WHAT was it for? And it has a lot of shortcomings in that regard I think. It’s just important to me to let you know rn that this post doesn’t contain my full reaction to the ending, which is a lot of sadness, confusion, and disappointment. Okay now I’ve gotten that out of my system. Apologies, real response incoming, I was just struggling to sit on that

Ops, sorry, I misunderstood you on the whole Iida family needed saving.

Now... maybe I'm totally off track but I like to think there was a time in which Horikoshi considered saving Tomura, Himiko and Touya.

We've various arcs that offer understanding, we've Shouto who understands that Rei burned his face merely because his father made her life impossible and don't blame and wants to save her, we've the Stain arc in which while it's made clear iida wanted to do the wrong thing, he's given plenty of sympathy for hos his rage twisted his thoughts, we've how Shouto and Bakugou during the remedial courses were told to connect their hearts with the kids, we had Gentle Criminal, we've Nagant, we've the story implying killing Twice was a mistake, we had Uraraka claiming she wanted to save people because she couldn't save Nighteye and so on.

Maybe Horikoshi wasn't sure if he wanted to kill them and left open both options.

On the other side... saving all the aforementioned people is narratively 'easy'. Rei was punished by spending 10 years in a hospital for a scar she caused in a moment of misplaced panic, Iida had bad intentions but ultimately he saved Native and didn't kill Stain, Gentle Criminal never did something too serious, Nagant was jailed and helped defeating AFO and Tomura, placing her life on the line.

The story is basically saving people who did light crimes or was already punished. It's hard there would be controversy in this, while there would be controversy if the story were to save people who had murdered multiple people, there could be controversy, especially since they don't show regret nor have time for redemption.

So many tales prefer to end things tragically by killing them off.

It's not really something new, "Saint Seiya" (1985-1990) wasn't shy to murder many antagonists who did less and were even regretful for it.

Said this doesn't mean that I agree with the choice of murdering them, I think Horikoshi with them went on the 'easy' route' which killing them off offers. Which okay, it's a possibility but I was hoping for more.

Honestly I though Midoriya and the others would become the greatest Hero because he would manage to save them. I'll summarize because it's not so simple but, fundamentally, he instead became the greatest Hero because he killed the greatest big bad (AFO) which doesn't make him any different fromt he Heroes that preceded him, like Son Goku from "Dragon Ball" (1984-95) or Kenshirō from "Hokuto no Ken" (1983-88), which would have probably be fine if the story didn't seem to imply he would do more than what they did.

And yes, he inspired people which indirectly made society better but... maybe it's just me but I wasn't impressed. I get Horikoshi tried hard to deliver this, I just wasn't won over.

I probably won't manage to reply to you for a while as tomorrow I'll get hospitalized, so my apologies for my future silence.

When I'll come back home I'll get back at you!

One problem with the society of BNHA is that being “someone in need of saving” is an undesirable category to be in.

“People who need saving” is a category of people. It’s hypothetically a valued one, since heroes save those people.

However: there’s no glory in needing to be saved.

There’s glory in SAVING, but we value the people who do the SAVING, not who need to be saved.

One thing that REALLY felt off to me in the final chapter was how that granny talks to Joki Joki Boy. She talks about herself, about who she can be. If I was in his shoes I would itch under this. Under someone explaining how they can be so charitable to people like me.

I was trying to think about what Izuku could possibly have “showed the world.” I still don’t quite have my answer.

But weirdly I do know what wasn’t shown to the world when the cameras on Ochako and Himiko cut off.

They didn’t see a villain being a hero. They didn’t see a hero needing saving.

The lines between the three societal categories - hero, villain, and people who need saving/protecting - blurred. And the camera missed it.

216 notes

·

View notes

Text

02 and the question of “what a life is”

One topic more specific to 02 is the question of what exactly counts as being “alive”, which is initially brought up as a question when Ken discarding the Kaiser persona is directly caused by the revelation that he might have misjudged this, leading into the second half of the series where other issues reveal that it’s not as easy of a question as one thinks. In the end, 02 never gives a concrete answer about what constitutes the boundary between something that’s “alive” and “not alive” -- but, being a series that’s very much about pragmatism, gives a much clearer answer as to what one should do about it.

While it’s not named directly in the series itself (I’m not sure if this specific named concept was the intent, as it’s since expanded to become a fairly ubiquitous theme in sci-fi and fantasy overall), 02 deals heavily with a question related to a thought experiment called the “Chinese room problem”, which originated as a question related to artificial intelligence development and has since expanded into having philosophical and spiritual nuances (perhaps fittingly for Digimon Adventure, which is heavily about digital technology and sci-fi but mixes it with a lot of philosophical and spiritual imagery).

The Chinese room problem goes like this: let’s say you’re a person who has never learned, studied, or grown up with the Chinese language (or, really, any language you can’t understand or read; Chinese was only used as an example because the person explaining the thought experiment was using himself as an example and couldn’t read or understand it). You’re locked in a room that has a bunch of Chinese phrasebooks that give you instructions -- basically, they indicate common Chinese phrases, and sensible responses you can give to them (without actually translating it to a language you know). Someone slips you a piece of paper under the door with some Chinese phrases on them. You use the phrasebooks to write appropriate responses, and slip the paper back. The person outside the door reads the paper, sees what they gave you, and sees the response you gave them. It makes sense, of course, because the phrasebook told you to write an answer that made sense. But can you be said to actually understand Chinese? No, because you were just following instructions without actually understanding what they meant.

So let’s expand this to make it a bit more complicated: say you have an AI or a robot or something of the sort that accepts “input” -- people saying things to it, or showing it things -- and gives expected “responses” that seem sensible, through a bunch of complicated programs and processes in its programming. Can you say this robot is “alive”? One might say “no”, because, no matter how complicated and intricate it is, all of it is technically following a set of routine commands telling it to do certain things in response...or so you might say, but couldn’t you say the same thing about a human brain, which also takes input, processes it according to its own instructions (just caused by chemical processes instead of bytes and code), and creates output? After a certain point, this question is going to become far more of a philosophical, spiritual, and potentially even religious question than anything.

Adventure and 02 undoubtedly have a very spiritual element to it, given the heavy usage of Neoplatonic themes, the concept of “destiny” that hangs heavily over it, and the fact that Digimon themselves are heavily linked to spiritual things like Japanese youkai or other spirits and literally being part of the human soul. Digimon partners are treated as part of their partners’ human psyches, yet are also treated as individuals. And, in the end, it’s driven home that Digimon are made out of data -- but “digital technology” is treated as something that can communicate with such spiritual things. So here’s the question: At what point can a Digimon be called a living being?

Well, really, the first time this had really been brought up was the allusion to the issue in Adventure episode 20 -- when Taichi takes the revelation of the Digital World being a “digital” world a bit too literally and decides to treat it as a game, acting a bit too recklessly as a result. Koushirou himself buys into the theory of “real bodies” (which turns out to be false; this isn’t a Matrix situation where their bodies are sleeping somewhere, but they are actually being migrated here), but the point by the end of this episode is: just because everything is “data” doesn’t mean you get to treat it any less lightly. Do not treat the Digital World like a “game world” or something you can fiddle with at will.

Even if the technicals may make it seem like a computer, the reality of the situation is that everything you do has a permanent effect that you cannot instantly take back. It doesn’t matter what it’s “made” up out of; the issue is more about what you do, and the practical impact it has on what’s around you. (This will very important for later, so keep this in mind as we go.)

So by the time we get to 02, the first time this issue is brought up again is in 02 episode 20, when Ken, as the Kaiser, recognizes the kids’ Digimon Baby forms as the “plushies” he’d seen them carrying in real life during the soccer match back in 02 episode 8, which reveals a lot about his mentality in approaching the Digital World and Digimon -- he’d been under the impression that Digimon couldn’t leave it, apparently, and that they were therefore all part of a simulated game. Driving it in further is that Wormmon refers to the Digimon having “bodies” (as in, physical bodies), which trips Ken’s radar that there’s a lot more to this than he’d thought. There’s also a lot of evidence that Ken wasn’t just solely trying to buy into this concept for the sake of denial and self-justification; up until this point, he’d been noticeably hesitant to physically harm other humans, so he really did buy into there being a substantial difference here.

...But, funnily enough, we later learn in a flashback in 02 episode 23 that Ken didn’t necessarily always have this attitude of “Digimon aren’t living beings, so I get to do whatever I want with them” back during his original adventures with Wormmon in the Digital World. One could argue that maybe he “knew” that Digimon were alive back then and the Dark Seed just made him forget through trauma, but even Taichi hardly treated the Digimon badly back when he thought that everything was a “game” back in Adventure (rather, he was reckless with himself more than anything). Later in this very series, there’ll end up being a massive debate on what exactly constitutes a Digimon having a “soul”. No, the real issue is actually...

What tips Ken over the edge into discarding the Kaiser persona is empathy -- when he retroactively reflects on the implications of the Digimon being “alive” meaning that every single action he’d done had an impact on causing “pain” or “torture” on others. That’s why it didn’t matter so much to him back then, because he was willing to treat Wormmon with the respect of a living being, regardless of what he was made out of (and, really, humans are more likely to be kind to things than otherwise, even when they’re supposedly “artificial”; for an extreme example, see how people are inclined to treat their robotic vacuum cleaners like family members, or have a hard time picking rude choices in video games, and those are all things you have much less of an argument for there being any actual pain inflicted).

And, hence, the main reason why the kids rail so much on the Kaiser for suggesting the heresy of “resetting the Digital World”: because he’s treating something with the gravity of “reality” like it’s something he can just toy with for his own convenience. Who cares what it’s made up of? There are actual civilizations building a livelihood here and “living beings” that can feel pain or show emotion. Nobody ever gave the kids immediate knowledge that Digimon have souls or any higher answer like that -- it’s just that the Kaiser is a callous, unempathetic jerk who’s willing to toy with so many lives and living individuals for his own pleasure. And, most importantly, everything the Kaiser has done here is something he can’t take back, and has to accept the consequences of; this wasn’t a place where he could vent out his feelings of being unable to “take back” Osamu’s death and treat everything lightly.

It doesn’t actually matter what it’s made up of -- the fact is that they act like living beings, show obvious personal feelings and a propensity to feel pain, and thus have the right to be treated as such. If you’re practically able to observe this, then you should be respecting that.

Once Archnemon takes over the position as most prominent antagonist, the kids start dealing with her Dark Tower Digimon that she uses to indiscriminately destroy things. This initially creates a lot of confusion for the kids, especially when Ken and Stingmon so easily kill Thunderballmon and it looks to them like he’s gone right back into sadism after supposedly being reformed -- thus, this would provide an issue with Ken’s apparent lack of empathy if he’s allowed to keep going, because he (seemingly) hasn’t learned his lesson and will go on to keep hurting more victims.

When Golemon goes to destroy the dam, it’s repeatedly commented on how unusual it is for a Digimon to just go and destroy a dam for no reason except to ruin people’s lives -- even the enemies back in Adventure at least had a power-hungry motive, and the non-verbal “wild” ones back in File Island were ultimately territorial at worst, and certainly not interested in wanton destruction without reason. On top of that, in fact, only two people -- Iori and Miyako -- in this group of five are actually that vehemently in favor of trying to spare Golemon for the sheer reason of it being a living being -- Daisuke starts to consider the fact that it may become necessary to save potential victims before Ken is even brought into the picture, Takeru points out how close they are to push-coming-to-shove, and Hikari clearly laments the fact it may become possible but doesn’t take nearly of the strong “we absolutely cannot do this” stance that Iori and Miyako have. And, after all, Takeru and Hikari were there back in Adventure when killing some very sentient Digimon became necessary, and learned that it may be something you have to do if you want to prevent more victims, and Daisuke had personally been a victim of Vamdemon back in 1999 and also happens to be one of the most pragmatic in this group.

Thus, the reveal that Golemon is actually a Dark Tower Digimon confirms two things for them: firstly, that it’s very unlikely that Golemon is powered by anything but a sheer instinct of wanton destruction, and secondly, that Ken does, indeed, have a concept of empathy. The kids had already noticed that something was “unusual” about Golemon in that it seemed to be incapable of independent action, just an order to “mindlessly destroy”, and it being what the series refers to as “a Dark Tower in the shape of a Digimon” just happens to confirm that it may not actually be that capable of independent action or emotion -- which they then realize that Ken also realized, and thus that he wasn’t killing Digimon out of callousness. This is, also, effectively, the same reason they’d been okay with killing Chimeramon earlier -- because there was absolutely no evidence that it had been capable of sentient reason or anything besides “destruction on instinct”.

So, again: their judgment on the situation is based on a practical observation about whether the entity in question was capable of having emotions or independent thought, and, again, a question of empathy...

...because we learn that the same process, when applied to enough Dark Towers, is enough to create a Digimon who is capable of that kind of independent thought and doesn’t feel up to taking orders, regardless of whether Archnemon is his “creator” or not. So we’ve got a demonstration of a Digimon who’s clearly capable of independent thought in ways the other Dark Tower Digimon are not (he even voices “envy” for the other single-tower Digimon Archnemon creates for being unable to think about anything), and starts exhibiting irrational behavior and the concept of “emotions”.

Recall the issue of the Chinese room problem: if we’re talking about a room of phrasebooks that simply take one input and export output, you, in the middle of the room, can’t really be said to be “understanding” Chinese. But the more complex the inputs and expected outputs get, the more complicated and intricate and explanatory those phrasebooks are going to need to be, and at some point, given a complicated enough question you get, if you’re capable of answering that in the same way a human might be expected to, that information in the phrasebooks will have to be explanatory enough to an extent you’ll be said to understand Chinese. Exactly “how complicated” or “how nuanced” does a program get before we tip that boundary? Clearly there is some difference between BlackWarGreymon and the other Dark Tower Digimon, but what is it?

And when 02 episode 32 comes around and Agumon decides to have a little bonding chat with BlackWarGreymon, even he can't answer the question definitively as to what a "soul" or “heart” is -- nobody in this narrative can, and this series has no answer. There’s no real clear-cut rule as to the boundary as to when one can be considered sentient. But while Agumon may not be able to immediately yank out deep philosophy, he at least has a deep level of insight and understanding as to what it means -- you have feelings for others, you have emotions, you have things you want that aren’t necessarily what others expect you to do, and you can bring your own perspective to the table.

The debate over what to do with this also leads to the rift between Takeru and Iori that they have to work towards mending during their Jogress arc -- Takeru’s trauma regarding Patamon in Adventure has spiraled him all the way over into prejudice against anything related to the darkness, and Iori, who understands there’s more to the situation than that, but also happens to be on the other extreme of considering it immoral to kill anything regardless of whether it’s about to murder a ton of other victims while it’s at it.

Ultimately, Adventure and 02 is a narrative that prioritizes “pragmatism” first, and the moment it’s made clear BlackWarGreymon isn’t going to cause problems anymore, the kids all decide it’s fine to let him be. In the end, whether BlackWarGreymon is “alive” is a philosophical question, but...

...whether they should hold back in fighting just to “spare lives” really has no bearing on that question. Enemies like LadyDevimon and the other Digimon the kids are ultimately forced to end up fighting are clearly alive with their own emotions -- it’s just that those emotions do happen to be uncontrolled sadism and an active desire for wanton destruction. Miyako herself even observes that LadyDevimon is a “coward” -- but she’s also still emotionally torn by the fact they end up killing her, and the story also doesn’t give her grief for this, because there’s no sin for her to have empathy. She recognized what it meant to kill a life, but they also cannot be blamed for taking that life in the process of saving multiple others. The issue of “whether it’s alive or not” had always been a separate question from the morality of fighting said lives -- and, either way, it’s still valuable that characters like Hikari, Miyako, and the other Chosen Children aren’t necessarily doing this because they like doing it, because it’s still important to keep that feeling of “empathy” in their hearts, even if push did ultimately come to shove.

So when BlackWarGreymon does return, again, nobody has an answer for him on whether he has a soul or not, but in 02 episode 47, Agumon, V-mon, and Wormmon encourage him to embrace the concept of life by “experiences” -- happiness, sadness, pain, playing and enjoying life with those you care about. Because those experiences are “real”, and Agumon himself says that “those experiences have made me who I am”; regardless of the higher philosophical question of whether he has a soul or not, he’s still someone who’s capable of having experiences and acting based on his memory of them, and that’s what’s really important. And hence, when BlackWarGreymon sacrifices himself one episode later, it’s because he understands the meaning of “doing something for others”, and is also implicitly mourned by the other Digimon, who had never failed to see him as “someone they could have befriended”, regardless of what he had originally been made up of.

It’s also why the kids are so traumatized by Archnemon and Mummymon’s deaths in 02 episode 48 -- they had no reason to be personally attached to them prior to that, and Archnemon had even said that her personal goals were nothing but wanton destruction in 02 episode 29 (which had been the first time Iori had really considered that pacifism may not be completely possible here). All of the wacky hijinks between the two of them had largely been outside of their view. But even back in 02 episodes 36-37, the kids had understood that there was some degree that they were harmless if left alone, and in the end, they watched Archnemon die in unambiguous pain and Mummymon die in the name of true love, by dying in a suicide attack because of his despair over losing her.

Archnemon and Mummymon had ultimately turned out to be “artificial lives” on their own, created at the hands of Oikawa to be his minions, and also somewhat guided by “wanton destruction” and not entirely fully aware of what they wanted to do independent of him -- BlackWarGreymon’s existential crisis had caused them to question their place in the world in 02 episode 47...and quickly shrug it off again. Could you say anything about whether they were alive or not, or whether they had souls? Perhaps it doesn’t really matter -- whether or not they were able to fully have deep thought the same way BlackWarGreymon and the other Digimon had, they at the very least were able to feel attachment and pain, and that alone deserved to be respected.

In the end, you could say that’s 02′s answer -- or non-answer -- to the Chinese room problem. You may not be able to answer the intrinsic philosophical question of whether it’s got a “soul” or is “alive” or not, but if it’s clearly demonstrating an observable and practical phenomenon of showing emotions, acting on some degree of independent will, taking in experiences and acting on them, and being able to feel a sense of pain, then you should still treat it with the appropriate amount of empathy -- regardless of what it’s made out of.

Incidentally, we do actually get a very small revisiting of this topic in Kizuna, when Menoa creates a ton of Eosmon by “scientific” methods -- and, much like the Dark Tower Digimon, they’re not recognized as living beings by anyone in this narrative, because their behavior is clearly that of mindlessly following Menoa’s orders; Yamato won’t consider it a Digimon, and Menoa herself even acknowledges that this is in no way a real “partner” like her true one, Morphomon. What does get Menoa to recognize Morphomon within Eosmon is when it does one thing -- smile -- that’s clearly outside that view, and an obvious show of independent emotion, leading Menoa to realize that her true, living partner may be closer than she’d thought.

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

Psycho Analysis: Jason Voorhees

(WARNING! He’s back! THE MAN BEHIND THE MASK!)

...ki ki, ki, ma ma ma...

The slasher subgenre of horror has plenty of villains, but the key to any great slasher movie (aside from quality kills) is having a memorable slasher who sticks in the mind of those who watch the film. You can’t just have some generic evil guy and expect the killer to be cool and memorable; you need to give them a fun gimmick. And in the scores of slashers who populated the 80s, there are few out there who are quite as legendary and iconic as Jason Voorhees. Jason is one of those few villains who, even if you’ve never seen a single one of his movies, you’d know on sight.

Even now, with him being absent from cinema for over a decade at the time of this writing due to legal disputes (though not from other mediums such as video games), Jason is still a household name, still remembered as one of the coolest, creepiest horror villains to come out of the 80s. In fact, I’d even go so far as to say Jason might be the greatest slasher villain of all time. So let’s take a look at the man behind the mask and see what we’ve got here.

Motivation/Goals: Jason as a villain is motivated by two main factors: a desire to make his mother proud, and a desire to get vengeance for how he was treated. The first few movies are all Jason taking out his anger over his mother’s death on anyone near Camp Crystal Lake. In earlier movies, he’d really only kill anyone who invaded his territory, but later sequels had him expand his killing range by going to Manhattan, Springwood, and even outer space. Basically, Jason is motivated by revenge against a world that persecuted him, and a desire to impress his mother. The simplicity of his motivations is actually a great strength, because it means there doesn’t need to be constant time in each new film adding on to Jason’s lore like they do with Freddy, Michael Meyers, and so on. Jason kills kids who have sex, that’s it. Simple, clean, effective, and a vehicle for cool kills.

Performance: There are a LOT of people who have put on the hockey mask throughout the franchise, but perhaps the most well-known name is Kane Hodder, the hulking actor who portrayed Jason in the seventh through the tenth films. He’s certainly the Jason that will spring to mind when thinking of Jasons, but he’s the obvious one. His actor in Freddy vs. Jason, Ken Kirzinger, was chosen because he had kind eyes and could tower over Freddy, and amusingly he actually appeared in Jason Takes Manhattan as a huge chef Jason tosses aside. Then of course we have Ari Lehman, the man who cameoed as Jason at the end of the first film in the Carrie-esque jump scare, most notable because he is so proud of his role that he named his punk rock/heavy metal band First Jason.

And these are just the few I wanted to highlight here; the original continuity is ten movies worth of actors playing Jason, and he even has multiple actors in some films.

Final Fate: It depends on the movie. His mortal life is ended by a young Tommy Jarvis in The Final Chapter, but then he comes back in Jason Lives as a zombie, a zombie who is only incapacitated until Jason Takes Manhattan where he is seemingly killed off for good by the nightly flooding of the Manhattan sewers with radioactive sludge (likely a safety measure against C.H.U.D.s). But then he comes back in Jason Goes to Hell where his original body ends up obliterated for most of the movie until the ending, but soon after he’s dragged right down to, you guessed it, Hell. But then comes Jason X, and he’s brought to space where he finally ends up obliterated for real by falling through the atmosphere of a planet and burning up. And this isn’t getting into the numerous deaths from games, comics, and so on; Jason is a man who is very hard to kill.

Best Scene: What does one pick for the best scene? His sleeping bag kill from VII? The liquid nitrogen kill from Jason X? The numerous amusing scenes he has when he actually reaches Manhattan in Jason Takes Manhattan? It’s a tough choice, but honestly. I might just have to go with his corn field rave massacre in Freddy vs. Jason. It’s just so damn cool.

youtube

Final Thoughts & Score: Jason Voorhees is one of the great early slasher villains and, most impressively of all, he managed a remarkable level of consistency until the very end, at least compared to some of is peers. Compare to Michael Meyers, who had to constantly be rebooted because filmmakers kept trying to find ways to humanize and explan his motivations to the point that franchise has a fractured timeline to rival the Zelda series, or Freddy Krueger, who deteriorated from a terrifying psychopath who treated killing like a game to a non-stop quip machine that spent more time slinging one-liners than kills. Jason, while certainly going through some odd phases – recall the time he was a weird demon worm that could surf between bodies, or the time he went to space and became a cyborg – never really lost sight of the things that truly made him effective as a character.

Yes, Jason is a silent antagonist, but he says a lot with his deeds and actions. He’s a killing machine, but he certainly isn’t mindless, and he usually seems to have some sort of ethics that perhaps we don’t understand, but Jason certainly does. For instance, in later films Jason does not hurt animals, and once he’s a zombie he doesn’t kill children either. A lot of this likely stems from Jason essentially being a child in a deformed man’s body, and this goes a long to making him an interesting, tragic figure. Jason almost certainly doesn’t understand what he’s doing is wrong, and if he does, he’s almost certainly too blinded by rage to care, especially after becoming a zombie.

I think the underlying tragedy of Jason simply being a monster who only wanted to please his beloved mother and violently lashes out at those he sees, through his warped perspective, as the ones to blame makes him an interesting and complex character… and here’s the great thing! Unlike other slasher villains, this is all established very early on, and rather than continue piling on more and more backstory, the series decides to throw Jason into interesting situations. This is a problem that befell his slasher sibling Freddy; as cool as Freddy managed to be, every new film added more and more convoluted backstory rather than trying to put Freddy into an interesting scenario he could have interesting kills in. And the less said about Michael Meyers, the better. But Jason? They gave him all he needed in the first two movies, made him a zombie in the sixth, and then spent the rest of the series getting weird and creative. Jason is a villain effective because his simple characterization and motivation means he can slip into any sort of situation, be it fighting a telekinetic girl, going to Manhattan, fighting Freddy Krueger, fighting Ash Williams, slaughtering camp counselors en masse, or going to space.

It should be incredibly obvious Jason is an 11/10. He’s a testament to what makes a slasher villain great and memorable: he has a simple yet flexible mindset that allows him to be thrust into a variety of situations, he has an iconic outfit, he has an awesome weapon of choice, and he is parodied, referenced, and known throughout the world to this day. He has killer video game appearances in the likes of Mortal Kombat X and his own Friday the 13th game, he has tons of comics including ones where he takes on Freddy, Ash Williams, Leatherface, and even Uber Jason, and despite the obnoxious legal battles currently keeping him from appearing in any media to any great extent, you’d be hard pressed to find a person without even passing knowledge of Jason.

Here’s a few interesting notes, though – a lot of shout outs to Jason have characters using a chainsaw, which as we all know is the tool of Leatherface. Jason uses a machete for the most part but is very versatile, but even so the closest he ever came to using anything remotely like a chainsaw was in VII, where he used a weed whacker. Jason also didn’t gain his iconic look until the third film; in the second movie, Jason wore a burlap sack over his head. And finally, there’s a bit of trivia I’m sure most are aware of by now: Jason was not the killer in the first or fifth films. In the first film, the killer was actually Jason’s mother, Pamela Voorhees, and the fifth film Jason was still kind of dead so a copycat killer named Roy Burns took his place. So hey, while we’re here, let’s talk about these Jason adjacent killers:

Pamela Voorhees is one of those rare female slasher villains, and the fact she is so absolutely amazing makes you wonder why there aren’t more. She’s basically to Friday the 13th what The Boss is to the Metal Gear Franchise – an all-important female figure whose actions completely and totally changed the course of history. Her quest to avenge her son’s death led to her slaughtering people at Camp Crystal Lake, which led to her death… but then it turns out her son had lived all along, and her death served only to make him into a violent, vengeful monster. Add on the fact that Pamela was using the Necronomicon Ex-Mortis on her son to empower him (supported by Jason Goes to Hell and Freddy vs, Jason vs. Ash), and Pamela is indirectly responsible for every murder in the series. Or perhaps even directly, if it really is her voice Jason hears in some of the movies and the Friday the 13th game. Betsy Palmer absolutely kills it in the role (pun intended), and it’s a shame she was annoyed by the role for years, though she apparently did eventually come around and embrace it. As one of the great ladies of horror, Pamela definitely earns a 10/10.

But now let’s take a look at the opposite end of the spectrum with Roy Burns. The idea of a Jason copycat killer is not entirely without merit, and for the most part, the movie is incredibly solid, with good kills on Roy’s part. The issue comes with the ultimate reveal of his identity, which turns the entire movie into an utterly convoluted mess that makes absolutely no sense. The lack of buildup of any kind, save for two brief scenes prior to his unmasking, makes the twist lack any sort of punch, and his reasoning for killing people is just absurd. Hell, he isn’t even targeting the one person responsible – that guy gets away with a jail sentence while Roy butchers innocent people!

Basically, Roy fails at being an engaging replacement for Jason due to the film’s finale, which goes out of its way to undermine him and everything you just watched. It should come as no shock that he’s a 1/10. Still, unlike most villains with this rating, he does have a little bit of redemption due to being playable in the Friday the 13th game. You’re just controlling him as he kills without any worry about stupid backstory, so hey, I’ll give Roy that at least, and I can’t deny his mask is pretty sick.

UPDATE: Ok, I was way too hard n Roy. Yes, his motivation is stupid and poorly explained, his killings are absolutely ridiculous and make no sense with his motivation, I still stand by all that... and yet, I’m watching this movie for creative kills, right? And boy does our boy Roy provide. He slaughters his way through these oneshot characters with gusto! I think I’m just still bitter he’s not Jason, but I like Season of the Witch even if Michael Meyers isn’t there, so maybe I’m just too harsh on Roy and his movie in general. I think his dumbass motivations hold him back, but I think the correct score for him is a 6/10. He is most certainly not abysmal enough for a one and I was really foolish to issue a score like that. Sometimes even I have trouble overcoming my biases.

It’s interesting, though, that both of these characters tend to be forgotten, overshadowed by Jason. In the intro of Scream, Drew Barrymore’s doomed character accidentally says Jason is the killer of the first film, rather than Pamela. And I think that while that is likely a common misconception, it’s less because Pamela is forgettable but more that Jason is so overwhelmingly cool that he overshadows anyone else in these films with few exceptions. Jason may very well be the greatest slasher villain of all time, and if you disagree, well, who won in Freddy Vs. Jason again, hmmm?

And more importantly, what slasher villain has an Alice Cooper song dedicated to him?

youtube

I rest my case.

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Another weird Sonic coincidence that gets me?

Way back in the early days of the book, Ken Penders proposed a story that would feature a pair of villainous dentists who would be obvious parodies of the Mario Bros, this being at the height of the Console Wars and the old Nintendo/SEGA rivalry. There’s even some concept art of the idea still lingering around in the ether, here and there.

This idea was ultimately rejected by SEGA... yet across the pond over in the UK’s own Sonic the Comic, this creative conceit not only was utilized, but flourished in the form of the Marxio Bros, three evil stooges in service of Robotnik. Who hailed from “Marxio World”, which they never wanted to return to.

Not only that, but they’d go on to become re-occuring antagonists within the book.

That the idea of a villainous Mario Bros parody would crop up in a Sonic book isn’t in of itself too hard to swallow given the times they were published in. I just find it wild that the idea was rejected in one part of the franchise, and then wholeheartedly approved in the other.

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Though LEK left me feeling not the best, I will say that I think the villain was the best part, mostly because their arc perfectly matches my ideal for how Crests shape the arcs of the Digidestined, so I’m going to take this opportunity to once again talk about Crests

As I’ve said many times, I feel that Digimon is at its peak when the characters are given a specific characteristic that needs to be balanced between a lack and excess of said characteristic.

Courage (standing up to challenges and upholding what one believes is right)

Lack = Fear (Tai realizing that he’s mortal and being too afraid to fight)

Excess = Recklessness (Tai jumping into danger on purpose to try to force Greymon’s evolution)

Friendship (working together and identifying with others)

Lack = Isolation (Matt distancing himself and TK from the group)

Excess = Deindividualization (Matt falling into a groupthink mentality and othering Tai when he disagrees with the group’s decision)

Love (showing affection and caring for the wellbeing of another)

Lack = Rejection (Sora feeling unlovable and uncomfortable when Biyomon tried to show her affection)

Excess = Desperation (Sora chasing after and smothering the amnesiac Biyomon) [Jealousy and Obsession could work too, but I don’t think Sora ever really had any moments that could be characterized as such]

Knowledge (understanding the world around oneself and applying said understanding practically)

Lack = Ignorance (Izzy ignoring his own needs and health when trying to understand the virus in Tri) [can also be read as Frustration or Obsession]

Excess = Overfocus (Izzy ignoring the people around him because of his focus on information)

Sincerity/Purity (being true to oneself and speaking one’s mind)

Lack = Self-doubt (Mimi questioning if her behavior and tendency to stand out is acceptable)

Excess = Haughtiness (Mimi generally acting spoiled, eventually peaking as she takes advantage of a group of Digimon that need her help by requiring payment in the form of their servitude)

Reliability/Faith (taking responsibility and living up to expectations)

Lack = Neglect (Joe justifying his refusal to fight as others being able to do so in his place)

Excess = Anxiety (Joe becoming overwhelmed by the weight of the responsibilities and expectations put on him)

Hope (perseverance towards a goal)

Lack = Despair (TK feeling paralyzed when everything seems to be going wrong in Tri)

Excess = Naivete/blind optimism (TK assuming everything will work out on its own as a child)

Light (unclear, but possibly meant to be joy, happiness or positivity, since Nefertimon’s epithet is “the Light of Smiles”)

Lack = Pessimism (Kari losing her composure when she found herself in the Dark Ocean and when she thought Tai had been killed during Tri)

Excess = [unknown, as Kari doesn’t have any clear moments of excess, though “Mania” seems to be a likely abundance of joy, either not taking things seriously or deliberately ignoring or denying the negative aspects of situations; either would have been a believable character arc for Kari]

Kindness (courteousness, consideration and generosity)

Lack = Cruelty (Ken’s time as the Digimon Emperor, sadistically enslaving and torturing Digimon for personal gain)

Excess = Guilt (Ken’s tendency towards self-sacrifice in an attempt to make reparations for his actions as Digimon Emperor)

Again, as I’ve said in the past, none of the other characters have Crests of their own, but do have character arcs that can reasonably be extrapolated to characteristics suitable to Crests

Acceptance/Forgiveness (the capacity to look past another’s faults and differences)

Lack = Petulance (Davis viewing TK as a love rival over Kari without any actual evidence and hating Ken before meeting him just because he’s talented)

Excess = Gullibility [never comes up, but after accepting Ken, a moment of betrayal or deception would have been a compelling arc for Davis]

Honor (strong adherence to a moral code that one can be proud of)

Lack = Shame (Cody’s regrets of breaking promises, lying, and even killing what he thinks is a Digimon, despite the fact that all were contextually necessary)

Excess = Self-righteousness (Cody’s refusal to work together with TK due to a difference in values, specifically whether it’s ethical to kill a Digimon to protect others)

Passion (possessing high energy and the determination to see tasks through to completion)

Lack = Complacency/Despondence [never comes up to my recollection, but given Yolei’s themes of determination, having a moment where she gives up would be appropriate]

Excess = Carelessness (Yolei’s obsession with giving her all leads to her wearing herself out and getting Hawkmon hurt)

Gratitude (appreciation and reciprocation for what others have done for oneself) [Meiko has a number of themes such as a lack of confidence or a focus on her memories with Meicoomon, but the keyword of Tri being an expression of gratitude strongly implies that it was meant to be a major theme even if it wasn’t properly capitalized on]

Lack = Entitlement (not quite a problem of Meiko’s, but rather Meicoomon’s tantrums when misunderstanding and thinking that she’s been abandoned by Meiko; this could have been mirrored in Meiko, giving her a similar tantrum or interaction with the cast)

Excess = Indebtment [I don’t recall this coming up, but Meiko’s lack of confidence could have been extrapolated into feelings of inadequacy and not being able to pull her weight]

And finally we come to Menoa, the antagonist of Last Evolution Kizuna, who has a host of synonyms that can be used to adequately describe not only her arc, but the arc of the film as a whole

Change/Maturity/Growth/Potential (one’s progression through life and their own journey of self discovery) [given that it’s a common symbol for change and that it was literally the symbol for change in the film, the Crest of Change would likely be made to resemble a butterfly]

Lack = Stagnation/Regression (Menoa’s obsession not only with returning to and staying in her own past, but forcing that ideal onto others)

Excess = Precociousness (Menoa’s rapid advancement at an early age, sacrificing her formative years because of a perceived need to be mature, ultimately resulting in her losing her best friend, Morphomon, before she was emotionally capable of coping with that loss)

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

211. Sonic the Hedgehog #143

The Original Freedom Fighters (Part 2)

Writer: Romy Chacon Pencils: Art Mawhinney Colors: J&A Ray

So it's time to find out just how the original Freedom Fighters were betrayed and lost. The guard at the Lake of Rings catches a ring and then lets Sonic and Hope watch the place for a bit while he delivers it to the castle, and Hope urges Sonic to continue his story, which he agrees to on the condition that afterward she'll let him go off to do his thing. One day when Sally was still young, Stripe was speaking with her and being kind when Peckers, who has the worst name by the way, burst in with some news.

That's right, they found out about the Zone of Silence years before the current Freedom Fighters did. They went into the palace on a mission to rescue the king, or at least to gather more information for a future rescue, but suddenly found themselves trapped within a room, with Scales leering at them from the outside and Robotnik stepping up beside him. Scales had apparently betrayed his teammates because he wanted power and also because it was "totally within his nature" as a snake, but true to form, Robotnik had some treachery of his own to enact, throwing a horrified Scales in with his fellows. Robotnik revealed to them that they were standing in his first room-sized roboticizer, before pulling the lever.

Oof. Uncle Chuck, still roboticized, saw the whole thing and had it recorded in his memory banks for posterity, but those in Knothole never found out what happened until years later when he regained his memory. All they knew was that their heroes had disappeared, and held funerals for them all befitting their status as heroes. The young Sonic was stunned and demoralized, as Stripe in particular had always been kind and encouraging to him, but ultimately the actions of the original Freedom Fighters were what inspired Sonic, Sally, and the others to form their own group and carry on the fight.

Now remember how I said this ties into something I've brought up before? I've talked many times about how the war against Robotnik has essentially been carried on the backs of literal child soldiers, but we've never really discussed why this came to be. Well, here it is. This is why. Remember that Robotnik's takeover came right on the heels of the Great War, with barely a few years at most separating the two wars. From Robotnik's perspective, he couldn't have picked a better time to stage a coup - the kingdom was weakened, and a lot of its best fighters had likely died or had to retire permanently due to injures from the previous war. Not to mention that a lot of people who could have helped in the current war were likely captured and roboticized in the initial fight before they had time to react - Robotnik would have known who posed the greatest threat to his rule and made sure the swatbots targeted them, and in addition, it's implied in the previous issue that Stripe was one of the only veterans who had the sense to run away rather than stand and fight. The original Freedom Fighters were basically all Knothole had left. And when they were lost, Knothole was vulnerable. Hope was in short supply. Hardly anyone had the ability or the mental fortitude to even try to carry on the fight.

And then this little band of orphaned kids rallied around the precocious princess, and took inspiration from those who had fought before them. These kids, most of whom were barely older than eight (and I'm not guessing at that number, it's literally confirmed later on in the comic that Sonic started striking back against Robotnik at the age of eight), banded together with the overconfidence of young children and put themselves in harm's way to save the planet. They grew up so surrounded by war that participating in it was second nature to them, and though each of them were hit with their own unique traumas from the things they'd seen and experienced, they kept up the fight, into their teens and into now. And like I've pointed out before, even now that many of the kingdom's adults are freed and willing to continue the fight for them, they refuse to give it up. Sure, Sally may be preoccupied with being active ruler right now, and maybe Rotor has retired from field duty to work on inventions back home, but everyone is still wholly invested in the fight despite their still-young ages. And that's both inspiring, and utterly tragic - especially considering that most of them aren't even self-aware enough to understand how awful throwing children into a war is. They just don't know anything different.

But anyway, as Sonic's story winds down, Hope thanks him and then rushes off, remembering her homework assignment for history and leaving an exasperated Sonic to guard the pool alone after all. The next day, she has her report all finished, and recites it in front of her class to much praise.

That is a great way to tie everything together, if you ask me. I'm sure it makes Mrs. Stripe and everyone else who personally knew the original Freedom Fighters happy to see the youth of today, even the youth of another species entirely, remember the sacrifice of those heroes.

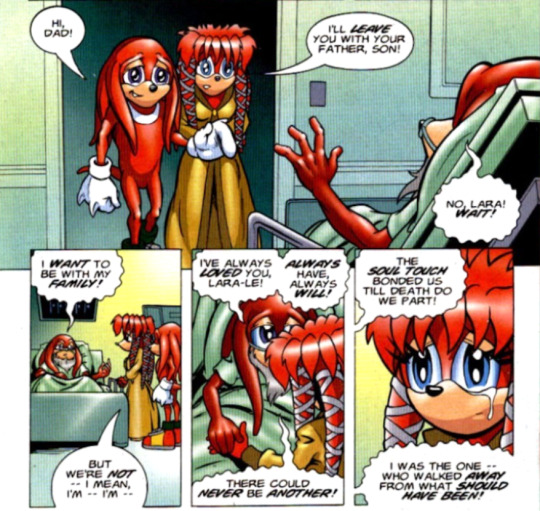

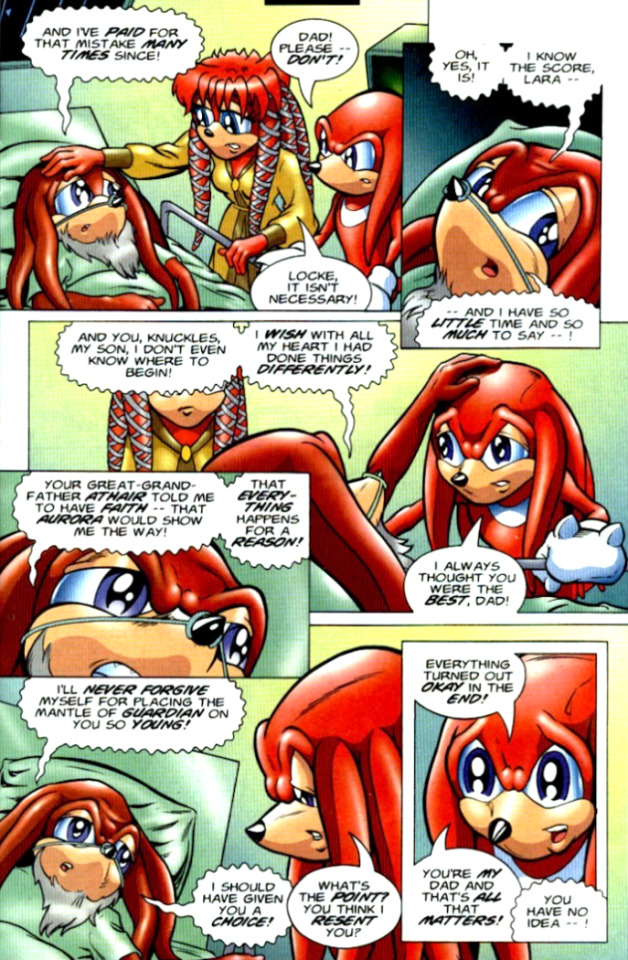

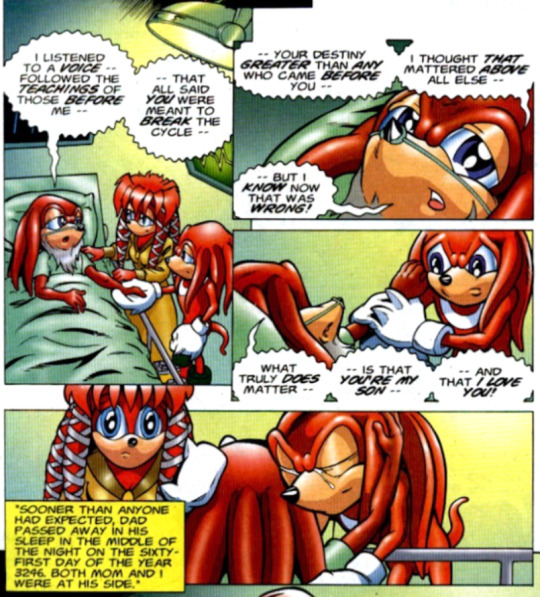

Mobius 25 Years Later: Father's Day

Writer/Pencils: Ken Penders Colors: Jason Jensen

Are you ready, kids?! This is actually the best installment of this arc, period! It's relevant to the current conflict, it contains important character development, and a satisfying conclusion is reached by the end! I know, I know, I'm shocked as well. But my praise for this chapter is genuine, and you'll see why.