#irish monastic

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Saint Brendan and the Paradise of Birds

Artist's Instagram

Artist's Facebook

#art#block print#PsalmPrayers#Psalm Prayers#wORKING aRTS#Saint Brendan#birds#Christianity#Catholic#Orthodox#Protestant#i love this artstyle so much#irish monastic#irish#celtic

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

#OTD in Irish History | 29 January:

1768 – Oliver Goldsmith’s ‘The Good-Natured Boy’ is first performed at London’s Covent Garden. 1794 – Archibald Hamilton Rowan, United Irishman, is tried on charges of distributing seditious paper. 1817 – Birth of geographer and explorer, John Palliser, in Dublin. Following his service in the Waterford Militia and hunting excursions to the North American prairies, he led the British North…

View On WordPress

#irelandinspires#irishhistory#OTD#29 January#Co. Kilkenny#History#History of Ireland#IRA#Ireland#Irish Civil War#Irish History#Kilree Monastic Site#Robert Downie Photography#Today in Irish History

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sailing toward the Wild Dark: A Short Reflection on My Patronal Feast and Nameday

There wasn’t a lot of institutional bureaucracy yet in the Irish Church in St. Brendan’s time—certainly very little that would affect a monastic founder in the west of the westernmost portion of Europe. The Saint was still very close—temporally, and probably in other ways as well—to the pre-Christian legacy and indigenous sacred traditions of Éire. In a sense, his famous voyage was from the still wild to the deeper wild.

The context of my own life and ministry as a monastic founder in twenty-first century North America is of course radically different. In fact, I suspect there is very little that St. Brendan would recognize about the Church today—or the world of human affairs generally. When his Feast comes up each year in the sacral calendar, I take it as an opportunity to reflect deeply on the ever evolving shape of my own vocation. And this year I find myself reflecting specifically on questions about the monastic relationship to institution: a fraught and tenuous thing from the advent of Christian monasticism as a movement, during the reign of Constantine.

From the deserts of Egypt to the untamed wilds of ancient Ireland, Christian monasticism was originally an endeavor that by necessity extended itself outside the accepted boundaries of ordinary Church convention and bureaucracy. At its heart, authentic monasticism still moves in this way, and must always do so, even if outwardly its radical witness has been hobbled, diminished, or diluted. In all the religious traditions that contain monastic expressions, it has always had this basic shape, being in essence the courageous journey of bold individuals who are willing to sacrifice everything in order to discover directly for themselves what is ultimate, what is true—and who are willing to walk beyond the safety of the communal firelight to make that discovery.

As with everything wild and prophetic, the Western dominator agenda sought from the start to tame and institutionalize the monasticism that rose up organically from the core archetypal impulse of asceticism, and from the social role and spirit of the rebel truth seeker, a pregnant void of which is left when agendas of control are allowed to reign. To a large extent the dominator force succeeded in its evil works, particularly with contexts like the Benedictine order, which became so institutionalized as to be almost unrecognizable in reference to its own monastic roots. Resultantly, there had to be reform after reform to try to recapture some of the original essence of the ascetical life and witness. Always in the West there has been this tension and pull from the institutional center of gravity, which is ever attempting to tame, to make ‘safe’ and manageable, controllable, and quantifiable the real Mystery which moves in the dark beyond its line of sight.

Of course, this agenda of control is a fool’s errand, ultimately. Yet, sadly, the will and attempt to continually whitewash the Mystery has had a vastly deleterious effect on Western cultures and societies, and, perhaps most markedly, on Western Christianity.

I am convinced that the monastic impulse to go courageously and directly into that which is fearful and unknown carries a special prophetic signature in today’s Church, at this historical moment in the twilight hours of the Church’s structural stability. In short, we monastics have the medicine, even if no one is willing to take it. For my part, I continue to be committed to faithfully calling out invitations for those on the sinking ship to leap toward the life-raft.

True to archetypal monastic form, my own place in the Church is and always has been marginal—and that’s as it must be. I’m somewhat of a relic, it seems: an instantiation of the old untamable ascetic who won’t play institutional games and won’t stop speaking from the shadowy wilderness just beyond its boundaries into the institutional morass, pointing out the failings of the assumed construct, and suggesting radical ways to transcend those failings—much to the chagrin of all those who are committed to institutional hegemony and the comfortable, easy path. By this point I know perfectly well my actual role and vocation, and am totally comfortable and at peace with it. I have even come to find genuine amusement in the troubled, suspicious responses of Church folk who resist or can’t grasp what I’m here to do.

But what brings me deeply into careful discernment these days, as someone who has spiritual children to guide and feels an immense responsibility to each and every one of them, is the direction in which to point my students with relation to institutional structures. Perhaps it’s less about broad direction, and more about degree.

As a Spiritual Father to monastics (and non-monastics as well), my core aim is always to shepherd and equip those who are ready for the real quest of existential excavation and illumination—and to help guide and point the way in such a manner that all non-essential material, detours, and distractions are completely forgone.

I recently shared with members of our religious order that, when it comes to decisions related to institutional collaboration or development, which would involve us in having to wade further into the swamp of Church bureaucracy, stagnation, and ignorance of the importance of who we are and what we do as vowed religious, I am constantly asking myself: ‘Is this really going to help us as a community? Is it going to further our spiritual aims and our core mission, or is it only going to waste time, cause aggravation, and distract us from what is really essential by sailing us straight into the mire of institutionalized absurdity?’

Sometimes the answers to these questions do not come easily. And the questions haunt, because I know full well that our time in this life is too short and unpredictable to fritter away on anything other than what is absolutely essential.

St. Brendan set sail in a wood and leather coracle with fourteen of his monastic disciples—not toward any institutional iteration, but toward the totalizing darkness of the utterly unknown: into the oceanic desert of the Mystery, the shattering, transformative wild, in order to more fully actualize the goal of all ascetical life, which was articulated so beautifully and concisely by St. Macarius the Great: to die to ourselves and to the world, that we may live as one with God.

May our holy Father among the Saints, Brendan of Clonfert, the namesake in whose radiant witness I always feel unworthy, bless me and all monastic shepherds with the wisdom to navigate unflinchingly by the singular star of Truth, to sail clearly and directly toward the only destination that is ultimately worth pursuing: non-dual awakening in and as the Uncreated Light.

Fr. Brendan+

Feast of St. Brendan of Clonfert, 2023

#brendanelliswilliams#fatherbrendan#monastic#monasticism#priest#ascetic#theology#religion#spirituality#spiritualjourney#awakening#spiritualawakening#nonduality#wisdom#ancient#tradition#irish#gaelic#saintbrendan#church#institution#courage#inspiration#reflection#depth#interreligious#teacher#spiritualteacher#spiritualdirector#author

1 note

·

View note

Text

it's technically not the numeral 7, it's this glyph :

⁊

it's called the "tironian et" (tironian referring to a kind of mediæval shorthand, and et being Latin for "and"). notice how, unlike 7, the ⁊ is at x-height with a descender

and fun fact ! it's actually still used in Irish language/Gaelic script typography. notice in the bilingual road-sign below, that ⁊ is used in the Irish, while & is used in the English translation

fun fact about old english!

the reason the ‘&’ symbol & the number 7 are attached to the same key MIGHT JUST be because back in the 1300s, scribes would often use ‘7′ as a shorthand way of writing ‘and’. see here:

#typography#irish#mediæval#manuscript#I learnt a bit of mediæval monastic shorthand in while at uni to use while taking notes in lectures#I still use ⁊ ; q with macron ; and a nonstandard abbreviation for -tion regularly

148 notes

·

View notes

Text

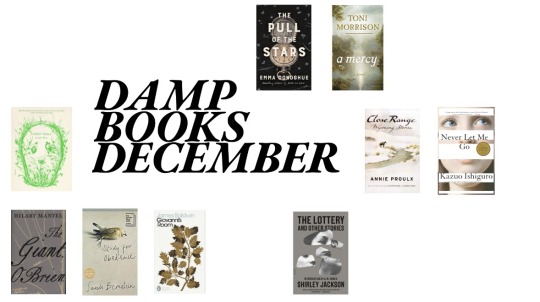

it’s time for DAMP BOOKS DECEMBER

here’s a rec list of cold wet seasonal reads: atmospheric books about offputting people, featuring mud, bog, spit, blood, wine, fog, ash, etc.

let’s get clammy with it. additional damp recs appreciated.

o caledonia by elspeth barker

a weird little girl in midcentury scotland. bonus wets: mushroom spores, slush, jam

the western wind by samantha harvey

a medieval murder mystery. bonus wets: goose grease, floodwater, the blood of christ

eileen by ottessa mosfegh

a juvenile prison administrator’s quarter life crisis. bonus wets: vomit, stale wine, dirty snow

the pull of the stars by emma donoghue

a couple days in a spanish flu clinic/maternity ward in dublin. bonus wets: amniotic fluid, mucus, soggy newspaper

a mercy by toni morrison

a household dissolving in seventeenth century new york. bonus wets: pox, mist, molasses

wolf hall by hilary mantel

a bureaucrat in the court of henry viii. bonus wets: ink, fever sweat, the thames

ghost wall by sarah moss

a camping trip with stone age reenactors. bonus wets: damson juice, bog bodies, bramble

the man who shot out my eye is dead by chanelle benz

a short story collection. bonus wets: brain matter, milk, the blood of christ again

never let me go by kazuo ishiguro

a dystopian art school for mysterious children. bonus wets: rain, marshland, tears

the name of the rose by umberto eco

a monastic murder mystery and also a primer on every theological debate that ever happened in 14th century europe. bonus wets: pig’s blood, bathwater, ink

wuthering heights by emily brontë

a case study in isolation, incest, and insanity, and the novel that inspired the whole list. bonus wets: dog saliva, mist, assorted consanguineous fluids

close range by annie proulx

a collection of wyoming stories. bonus wets: spit, semen, cold coffee

the giant, o’brien by hilary mantel

a giant irish storyteller visits london and loses his body to science. bonus wets: gin, pus, graveyard mud

study for obedience by sarah bernstein

a stifled woman in her family’s homeland. bonus wets: potato mold, creekwater, milk

giovanni’s room by james baldwin

an american in paris makes a mess. bonus wets: cognac, condensation, the seine

moby dick by herman melville

a man, another man, a third man, and a whale. bonus wets: sperm, fish chowder, sperm (other one)

the lottery and other stories by shirley jackson

a collection of unsettling stories about polite people. bonus wets: hose water, flop sweat, furniture polish

#bringing over a twitter tradition of mine#books that make you feel horrible! books that make you wanna get a little closer to the radiator!#the most important things a book can do imo#currently pitch dark and pouring rain so feels appropriate#reading journal

24 notes

·

View notes

Note

For this totally normal Friday could you possibly share some fun (or not so fun, whatever you want) figures in Irish Mythology/History whose experiences align/mimic those of modern day asexuals and aromantics? :D

This one is tricky, but possibly not for the reasons you might expect! For those who aren't aware, my PhD research focuses on friendship in the Ulster Cycle (particularly the later Ulster Cycle, so kind of post-12th century). This means I spend a lot of time thinking about how relationships are constructed in these texts and how people express affection, and the main thing I've noticed is that there's just... very little romance. It hardly ever comes up.

It's especially noticeable when you compare this material to chivalric romances being written at the same time -- your Arthurian tales for example -- where courtly love-service and other motifs are more prominent. The Irish simply don't go in for that. Even when people are married it's hardly mentioned, and even when they're having affairs and the text is focused on that, they don't emphasise the role of Feelings™ particularly. There are exceptions to this, but fewer of them than you might think; even the famously romantic stories tend to be... less romantic once you look closer at them.

I'm not entirely sure why, though I have a few theories (among them the effects of continued monastic/clerical authorship in periods when secular courtly authorship was more common in some other languages). You do get love poetry (non-narrative) in Irish in this period, just not much in the way of romantic prose (narrative), especially not when it comes to the Ulster Cycle. (And when people do get an attack of the feelings in the prose tales, they usually express those feelings in poetry. Prose is perhaps the wrong medium for falling in love. Most of the chivalric tales are in verse throughout, of course, so they don't have this problem. But Irish really goes in for prose as the medium for storytelling from a very early period, and even when they're translating tales from verse in other languages, often render them as prose.)

So, in many ways, it's hard to perceive characters who seem to have noticeably less interest in romance and/or sex than other characters, because desire is so rarely foregrounded in a recognisable manner. I'd say there's a bit more emphasis on sex, but very little on what we might call "romantic love". There's a lot to be said about how relationships and feelings are classified across this period that doesn't map onto our modern divisions, but even when comparing the literature with that being written at the same time and sometimes very nearby, it seems to be doing something slightly different. Maybe that's why I enjoy this material so much! 😂

Having said all that, Láeg is quite married to Cú Chulainn in a lot of ways, but other than that, I don't think he is ever hinted at having any kind of romantic or sexual entanglements with anybody at any point -- no casual flirting, no ill-timed affairs, no distractions. It could easily be used as a plot point to separate him from Cú Chulainn at a crucial moment but it simply never comes up. While this is quite likely just to be a class thing (we couldn't possibly acknowledge servants as having an inner life of their own), the way he judges Cú Chulainn for running off at the start of the Táin because he has a date very much gives Aroace Best Friend Is Judging Your Life Choices. Although possibly I'm projecting there 😅

Looking outside of Irish material, I have always read 'Guigemar' by Marie de France as resonating with demi experiences in particular. He is into one (1) person and one (1) person only, no matter how hard others try to make him behave in a more socially normative way. Bill Burgwinkle has some insightful remarks about queer approaches to this story in Sodomy, Masculinity and Law, but doesn't explore aro-/acespec readings; I think they would be very productive. When I wrote an essay on queer readings of Marie de France as an undergrad, that was one of the things I focused on.

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

St. Columba was born in Donegal, Ireland on this day in 521AD.

Of all the Dark Age Scottish saints, Columba is the most spectacular star. In 563 AD he left Ireland and settled with the Gaels of Dál Riata, where he was granted the Island of Iona to found his monastery.

For the Gaelic warrior kings, Columba was a useful asset. His monastery provided education for their sons, he was a close advisor to the king, and he served as a diplomat to the king’s neighbours in Pictland and Ireland. Columba’s blessing was treasured by kings - a powerful symbol of their authority, and, in return for Columba’s support, the Gaels gave the monastery land and protection.

Columba died in 597, but his monastery’s influence continued to grow, leading to the foundation of new monasteries in Ireland and as far away as Lindisfarne in Northumbria. In Pictland, Columban monks began to spread the word of Christianity in the seventh century.

Iona faced competition from other Irish monastic missions, however, and their religious power was not absolute. St Mael Rhuba at Applecross or St Donnan, who was martyred on the Isle of Eigg, were also contenders as early spiritual leaders of the Church.

Columba himself would have remained an enigmatic and little-known figure were it not for Adomnán, the ninth Abbot of Iona, and his book, the Vita Colum Cille (Life of Columba), which ensured that the saint's reputation eclipsed that of the other Scottish saints and spread Iona’s fame across Christendom.

Pilgrimage to Iona increased: kings wished to be buried near to Columba, and a network of Celtic high crosses and processional routes developed around his shrine. At its zenith Iona produced The Book of Kells, a masterpiece of Dark Age European art. Shortly after however, in 794 AD, the Vikings descended on Iona, and, within 50 years, they had extinguished the light which had been Iona. Columba’s relics were finally removed in 849 AD and divided between Alba and Ireland.

The Monymusk Reliquary, seen in the second pic, from around 750 AD, probably contained a relic of St Columba. It became a powerful symbol of nationhood, and was carried before the Scots army as it marched into war.

This reliquary is thought to be the Brechbennoch which was carried by the Scots at the Battle of Bannockburn in 1314. If you are ever in the National Museum of Scotland, go see it.

The first pic shows Columba in a stained glass window at St Margarets Chapel at Edinburgh Castle.

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Staff Pick of the Week

This morning we received a request from Ireland for information about our copy of The Voyage of Saint Brendan printed by the Dolmen Press in Ireland for the Humanities Press Inc. in the U. S. in a limited edition of 150 copies in 1976. The book contains a translation by the Irish classical scholar John J. O'Meara of the earliest Latin version of Brendan's legendary voyage, Navigatio Sancti Brendani Abbatis from the 9th century CE. The images used here are reproductions of woodcuts from Sankt Brandans Seefahrt, the first printed version of the legend produced in 1476 by Anton Sorg in Augsburg.

Brendan's journeys are among the most enduring of European legends, about the Atlantic wanderings of the 6th-century Irish monastic saint Brendan of Clonfert and his 16 companions in search of the Promised Land of the Saints. I am an admirer of the Dolmen letterpress-printed editions, and this printing bears all the hallmarks of my interest: handset in Pilgrim type with Victor Hammer's initials printed on Van Gelder mouldmade "Unicorn" paper and designed by Dolmen co-founder Liam Miller. Our copy, signed by the translator, is number 127, but the first 50 numbered copies are specially bound with hand-colored woodcuts. As lovely as the our copy is, I admit to coveting a copy from the first 50.

View other Staff Picks.

-- MAX, Head of Special Collections

#Staff Pick of the Week#staff picks#The Voyage of Saint Brendan#John J. O'Meara#Dolmen Press#Dolmen Edition#St. Brendan#Brendan of Clonfert#Irish literature#Irish legends#imaginary voyages#Pilgrim type#Victor Hammer initials#Van Gelder paper#Liam Miller#letterpress printing

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

Saint Aidan of Lindisfarne

590 - 651

Feast day: August 31

Patronage: Northumbria, firefighters

Aidan of Lindisfarne was an Irish monk and missionary credited with restoring Christianity to Northumbria. He founded a monastic cathedral on the island of Lindisfarne, served as its first bishop, and traveled ceaselessly throughout the countryside, spreading the gospel to both the Anglo-Saxon nobility and to the socially disenfranchised (including children and slaves).

Prints, plaques & holy cards available for purchase here: (website)

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

man. this man is connecting dots that aren't even on the same page as each other when there's a far more plausible dot RIGHT THERE

sure this twelfth century text probably written in a monastic milieu is drawing on historical events from 3rd century BC macedonia via tribal memory, and also on homer. couldn't possibly be that those details come from the well-known latin texts demonstrably circulating in that area at the time (and their irish and middle english translations) and which very much contain those elements in a form far closer to the version we've got here. no, that would be too logical

#academic thinkshaming#this book is over 700 pages and the takes just keep escalating#I'm only 287 pages in. where will we end up

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ach-To and Irish Archaeology

The sequels were my entry into Star Wars and I never would have gone to see The Force Awakens if I wasn't an archaeology nerd.

During the production of Episode VII, a decent number of people with an interest in our archaeological heritage here in Ireland were quite worried about the impact of filming on one of our only two UNESCO World Heritage Sites, the island known as Skellig Michael down off the coast of Kerry.

I went to the film to see if any potential damage was worth it, or if they'd do something unspeakably stupid with it in-universe. I wanted to see if it was respected.

And holy hell I was NOT disappointed. I think I walked out of TFA sniffling to myself about how beautiful the Skellig looked and how it seemed like its use as a location was not just respectful but heavily inspired by its real history.

See, Skellig Michael was a monastic hermitage established at a point when Christianity was so new that the man who ordered its founding sometime in the first century CE was himself ordained by the Apostle Paul. The fellah from the Bible who harassed all and sundry with his letters, THAT Apostle Paul. This is how old a Christian site the Skellig is. It predates St. Patrick by at the very least two hundred years.

The steps we watch Rey climb were originally cut NEARLY TWO THOUSAND YEARS AGO. They have been reworked and repaired many many times since, of course. Still, the path the camera follows Daisy Ridley up is as much an ancient path built by the founders of a faith in real life as it is in the movies.

A hermitage was a place where monks went to live lives of solitude and asceticism so as better to achieve wisdom. The practice is common to many of the major world religions, including the myriad East Asian faiths which inspired the fictional Jedi.

It is said that the hermitage and monastery were originally built with the purpose of housing mystical texts belonging to the Essanes, one of the sects of Second Temple Judaism which influenced some of the doctrines of Christianity. They also, according to what I have read, characterised good and evil as 'light' and 'darkness' and were celibate.

As such, the use of the island in TFA and TLJ does not merely respect Skellig Michael's history, it honours it. It is framed as somewhere ancient and sacred, which it is. It is framed as a place where a mystic goes to live on his own surrounded by nature that is at once punishing and sublime, which of course it was. It shown to be a place established to protect texts written at the establishment of a faith, which it may well have been.

This level of genuine respect for my cultural heritage by Rian Johnson in particular is astonishing. I don't think anyone from outside the US ever really trusts Americans not to treat our built history like it's Disneyland. Much of the incorporation of the Skellig's real past into a fictional galactic history occurs in TLJ, which is why I'm giving Rian so much credit.

It's Luke's death scene which makes the honouring of Irish archaeological history most apparent though.

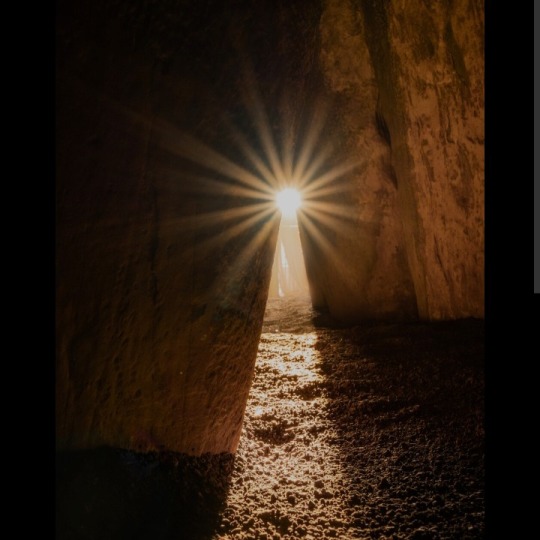

Johnson takes the archaeological iconography back a further three thousand years for his final tribute to my culture's beautiful historical temples. This time, he incorporates neolithic passage tomb imagery, specifically that of Newgrange, which is up the country from the Skellig.

I think if you understand what the image represents then it makes a deeply emotional scene even more resonant.

The scene I'm referring to is Luke's death.

As he looks to the horizon, to the suns, we view him from the interior of the First Jedi Temple. The sunset aligns with the passageway into the ancient sanctuary, illuminating it as he becomes one with the Force.

As for Newgrange, every year during the Winter Solstice it aligns with the sunrise. The coldest, darkest, wettest, most miserable time of the year on a North Atlantic island where it is often cold, wet, and miserable even in the summer. And the sun comes up even then, and on a cloudless morning a beam of sunlight travels down the corridor and illuminates the chamber inside the mound.

You guys can see this, right? The similarity of the images? The line of light on the floor?

Luke's death scene is beautiful but I think it's a thousand times more moving with this visual context. Luke's sequel arc isn't merely populated by a lore and iconography that honour the place where the end of his story was filmed, I think that incorporation of that history and mythology honours Luke.

We don't know for sure what the Neolithic people believed, religion-wise. We know next to nothing about their rituals. We know that there were ashes laid to rest at Newgrange. There is some speculation that the idea was that the sun coming into the place that kept those ashes brought the spirits of those deceased people over to the other side.

It's also almost impossible not to interpret the sunlight coming into Newgrange as an extraordinary expression of hope. If you know this climate, at this latitude, you know how horrible the winter is. We don't even have the benefit of crispy-snowwy sunlit days. It's grey and it's dark and it's often wet. And every single year the earth tilts back and the days get long again.

The cycle ends and begins again. Death and rebirth. And hope, like the sun, which though unseen will always return. And so we make it through the winter, and through the night.

As it transpired the worries about the impact of the Star Wars Sequels upon Skellig Michael were unfounded. There was no damage caused that visitors wouldn't have also caused. There also wasn't a large uptick in people wanting to visit because of its status as a SW location, in part I think because the sequels just aren't that beloved.

But they're beloved to me, in no small part because of the way they treated a built heritage very dear to my heart. I think they deserve respect for that at the least.

#star wars meta#ach-to#irish history#Irish Archaeology#first jedi temple#skellig michael#newgrange#luke skywalker#the last jedi#early christianity#neolithic#historical parallels in star wars#star wars and history#star wars and mythology#star wars and archaeology

136 notes

·

View notes

Text

High Crosses of Ireland

High Crosses or Celtic Crosses as they are also known, are found throughout Ireland on old monastic sites. Along with the Book of Kells and the Book of Durrow, these High Crosses are Irelands biggest contribution to Western European Art of the Middle Ages. Some were probably used as meeting points for religious ceremonies and others were used to mark boundaries. The earliest crosses in Ireland…

View On WordPress

#Celtic Crosses#High Cross of Clonmacnoise#High Crosses of Ireland#History of Ireland#Ireland#Irish History#Monastic Sites

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

SAINT OF THE DAY (March 17)

On March 17, Catholics celebrate St. Patrick, the fifth-century bishop and patron of Ireland, whose life of holiness set the example for many of the Church's future saints.

St. Patrick is said to have been born around 389 AD in Britain.

Captured by Irish raiders when he was about 16, St. Patrick was taken as a slave to Ireland where he lived for six years as a shepherd before escaping and returning to his home.

At home, he studied the Christian faith at monastic settlements in Italy and in what is now modern-day France.

He was ordained a deacon by the Bishop of Auxerre in France around the year 418 AD and ordained a bishop in 432 AD.

It was around this time that he was assigned to minister to the small, Christian communities in Ireland who lacked a central authority and were isolated from one another.

When St. Patrick returned to Ireland, he was able to use his knowledge of Irish culture that he gained during his years of captivity.

Using the traditions and symbols of the Celtic people, he explained Christianity in a way that made sense to the Irish and was thus very successful in converting the natives.

The shamrock, which St. Patrick used to explain the Holy Trinity, is a symbol that has become synonymous with Irish Catholic culture.

Although St. Patrick's Day is widely known and celebrated every March the world over, various folklore and legend that surround the saint can make it difficult to determine fact from fiction.

Legends falsely cite him as the man who drove away snakes during his ministry despite the climate and location of Ireland, which have never allowed snakes to inhabit the area.

St. Patrick is most revered not for what he drove away from Ireland but for what he brought and the foundation he built for the generations of Christians who followed him.

Although not the first missionary to the country, he is widely regarded as the most successful.

The life of sacrifice, prayer and fasting has laid the foundation for the many saints that the small island was home to following his missionary work.

To this day, he continues to be revered as one of the most beloved Saints of Ireland.

In March 2011, the Irish bishops' conference marked their patron's feast by remembering him as “pioneer in an inhospitable climate.”

"As the Church in Ireland faces her own recent difficulties following clerical sex abuse scandals, comfort can be found in the plight of St. Patrick," the bishops said.

They quoted 'The Confession of St. Patrick,' which reads:

“May it never befall me to be separated by my God from his people whom he has won in this most remote land.

I pray God that he gives me perseverance and that he will deign that I should be a faithful witness for his sake right up to the time of my passing.”

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Magyar invasion of Saint Gall from the Codex Sangallensis 602, manuscript dated 15th C. CE

"According to tradition, Saint Gall, a learned, probably Irish monk and faithful disciple to Saint Columbanus, founded a hermitage on the site that would come to encompass the abbey St. Gall around 610.

The abbey of St. Gall flourished during the Carolingian Era (750-887), emerging as a regional center of learning and trade. Housing one of the first monastery schools north of the Alps, the abbey had grown into a massive monastic center, replete with large guest houses, a working hospital, farms and stables, and a renowned library. The abbey quickly became a magnet for Anglo-Saxon and Irish scholars and monks who copied and illuminated manuscripts. Wealthy nobles, in turn, enriched the abbey through patronization and donations of land. By the turn of the ninth century, the abbey was among the most prestigious and wealthiest in Europe.

Three chroniclers substantiate, in different versions written between 970 and 1074, of a Magyar attack on St. Gall and its environs. The Alemannian Annals, written in the ninth and tenth centuries, mention the Magyars nine times, while the St. Gallen Annals of the tenth century do so fifteen times. The most interesting information about the Magyar sack comes from the chronicle of the monk Ekkerhart IV who lived more than a century after the invasion. According to him, as the Magyars swept through Swabia and entered the vicinity of Lake Constance, Abbot Engilbert took protective measures to ensure the survival of the monastery. He ordered the abbey’s old monks and young students to move to Wasserburg, which lies along Lake Constance and near Lindau, to await the siege. The younger, stronger monks were to seek refuge in the woods and hills near the village of Bernhardzell, to the northwest of St. Gall.

On May 1, 926, the Magyars stormed St. Gall. The attackers advanced to the church of St. Mangen and set it on fire. They also tried to set fire to Wiborada’s hermitage, as they could not locate its entrance. Meanwhile, other Magyar warriors ransacked the monastery, taking what booty they could find.

Despite observing their lust for loot, the chronicles praise the Magyars in their ability to assume battle formation in a matter of only a few seconds, in their use of a sophisticated network of couriers to communicate with troops from afar, and in their mastery of various weapons. Noted further were the Magyars’ love of wine, music, dance, and fresh, tasty, meats.

After a few days of rest, the Magyars moved on to target other Swabian cities, leaving the imbecilic Heribald behind. When the monks and friars returned to St. Gall to assess the damage, they questioned Heribald about what he had seen. He reportedly said, “They were wonderful! I have never seen such cheerful people in our monastery. They distributed plenty of food and drink.”"

-James Blake Wiener, When the Magyars invaded St. Gall. From the Swiss National Museum blog.

#history#medieval art#medieval history#medieval literature#middle ages#hungarian history#museums#manuscript#medieval#finno ugric#magyar

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Thanks to Ian Simpkins for this information:

After being taken by Irish raiders, Patrick lived as a slave for over six years, taken at only 16 years old. Upon escaping captivity he returned back home to Britain where God began to stir something in his heart. He would later return to Ireland in AD 432, to the very people that held him enslaved all those years, not with malice but with a passion to show them the life-altering love of God.

Author Richard Fletcher writes:

"Patrick's originality was that no one within western Christendom had thought such thoughts as these before, had ever previously been possessed by such convictions. As far as our evidence goes, he was (one of) the first persons in Christian history to take the scriptural injunctions literally; to grasp that teaching all nations meant teaching even those who lived beyond the border of the frontiers of the Roman Empire."

In his Confessio, Patrick writes of his passion to reach the people of Ireland with the good news of Jesus - no matter the cost:

"Daily I expect to be murdered or betrayed or reduced to slavery if the occasion arises...

But I fear nothing, because of the promises of heaven."

Patrick regularly upset the social order by encouraging women to push back on the prevalent notion of the 5th century that women were mere commodities. When the Roman worldview asserted that Ireland was barbaric and cruel Patrick audaciously advocated that Ireland was worth reaching and worth loving.

While most scholars agree that his education was lacking and his Latin was poor, Patrick ardently promoted study, examination, and the monastic life. He pursued a life of dedication and discipline - all for the goal of more deeply entering into the storyline of those who had lost their way.

Patrick's civil disobedience made him a lot of enemies, but the threat of death paled in comparison to the burden God placed in his heart. This is the man whose life we celebrate on St. Patrick's Day.

While St. Patrick didn't likely write the famed Breastplate Prayer (scholars assert that the language postdates him by almost 300 years), it is a beautiful reminder of the kind of life he lived and a stirring reminder to us of the kind of life to pursue.

“Christ behind me, and Christ in me, Christ beneath me, and Christ above me, Christ to my right, and Christ to my left, Christ when I lie down, and Christ when I arise, Christ in the heart of everyone who thinks of me, Christ in the mind of everyone who speaks of me, Christ in every eye that sees me, and Christ in every ear that hears me.”

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

SAINTS&READING: FRIDAY, FEBRUARY 14, 2025

february 1_february 14

Forefeast of the Meeting of Our Lord

Troparion of the Forefeast of the Meeting of our Lord, God & Savior Jesus Christ, The celestial choir of the angels of heaven,/ coming to earth, behold the Firstborn of all creation Who is come,/ borne into the temple as a Babe/ in the arms of the Mother who knew not man.// Wherefore, with us they chant hymns of the forefeast, rejoicing.

Kontakion of the Forefeast. The Word Who is invisibly with the Father/ is now seen in the flesh, ineffably born of the Virgin,/ and He is given to the high priest on the arm of the elder.// Let us worship Him as our true God!

VENERABLE VENDEMIANUS ,HERMIT OF BITHYNIA (512).

Saint Vendemianus (Bendemianus) was born in Myzia. In his youth he was a disciple of Saint Auxentius, one of the Fathers of the Fourth Ecumenical Council. He went to the monastery founded by Saint Auxentius (February 14) on Mount Oxia, not far from Chalcedon (Asia Minor), where he lived in asceticism for forty-two years at the cell of his teacher in the crevice of a cliff. He spent his life in fasting and prayer, and was tempted by demons. Because of his holy life and spiritual struggles, the saint was granted the gift of healing. He died around the year 512.

St BRIGID OF IRELAND (523)

Saint Brigid, “the Mary of the Gael,” was born around 450 in Faughart, about two miles from Dundalk in County Louth. According to Tradition, her father was a pagan named Dubthach, and her mother was Brocessa (Broiseach), one of his slaves.

Even as a child, she was known for her compassion for the poor. She would give away food, clothing, and even her father’s possessions to the poor. One day he took Brigid to the king’s court, leaving her outside to wait for him. He asked the king to buy his daughter from him, since her excessive generosity made her too expensive for him to keep. The king asked to see the girl, so Dubthach led him outside. They were just in time to see her give away her father’s sword to a beggar. This sword had been presented to Dubthach by the king, who said, “I cannot buy a girl who holds us so cheap.”

Saint Brigid received monastic tonsure at the hands of Saint Mael of Ardagh (February 6). Soon after this, she established a monastery on land given to her by the King of Leinster. The land was called Cill Dara (Kildare), or “the church of the oak.” This was the beginning of women’s cenobitic monasticism in Ireland.

The miracles performed by Saint Brigid are too numerous to relate here, but perhaps one story will suffice. One evening the holy abbess was sitting with the blind nun Dara. From sunset to sunrise they spoke of the joys of the Kingdom of Heaven, and of the love of Christ, losing all track of time. Saint Brigid was struck by the beauty of the earth and sky in the morning light. Realizing that Sister Dara was unable to appreciate this beauty, she became very sad. Then she prayed and made the Sign of the Cross over Dara’s eyes. All at once, the blind nun’s eyes were opened and she saw the sun in the east, and the trees and flowers sparkling with dew. She looked for a while, then turned to Saint Brigid and said, “Close my eyes again, dear Mother, for when the world is visible to the eyes, then God is seen less clearly by the soul.” Saint Brigid prayed again, and Dara became blind once more.

Saint Brigid fell asleep in the Lord in the year 523 after receiving Holy Communion from Saint Ninnidh of Inismacsaint (January 18). She was buried at Kildare, but her relics were transferred to Downpatrick during the Viking invasions. It is believed that she was buried in the same grave with Saint Patrick (March 17) and Saint Columba of Iona (June 9).

Late in the thirteenth century, her head was brought to Portugal by three Irish knights on their way to fight in the Holy Land. They left this holy relic in the parish church of Lumiar, about three miles from Lisbon. Portions of the relic were brought back to Ireland in 1929 and placed in a new church of Saint Brigid in Dublin.

The relics of Saint Brigid in Ireland were destroyed in the sixteenth century by Lord Grey during the reign of Henry VIII.

The tradition of making Saint Brigid’s crosses from rushes and hanging them in the home is still followed in Ireland, where devotion to her is intense. She is also venerated in northern Italy, France, and Wales.

2 Timothy 3:1-9

1 But know this, that in the last days perilous times will come: 2 For men will be lovers of themselves, lovers of money, boasters, proud, blasphemers, disobedient to parents, unthankful, unholy, 3 unloving, unforgiving, slanderers, without self-control, brutal, despisers of good, 4 traitors, headstrong, haughty, lovers of pleasure rather than lovers of God, 5 having a form of godliness but denying its power. And from such people turn away! 6 For of this sort are those who creep into households and make captives of gullible women loaded down with sins, led away by various lusts, 7 always learning and never able to come to the knowledge of the truth. 8 Now as Jannes and Jambres resisted Moses, so do these also resist the truth: men of corrupt minds, disapproved concerning the faith; 9 but they will progress no further, for their folly will be manifest to all, as theirs also was.

Luke 20:46-21:4

46 Beware of the scribes, who desire to go around in long robes, love greetings in the marketplaces, the best seats in the synagogues, and the best places at feasts, 47 who devour widows' houses, and for a pretense make long prayers. These will receive greater condemnation.

1 And He looked up and saw the rich putting their gifts into the treasury, 2 and He saw also a certain poor widow putting in two mites. 3 So He said, "Truly I say to you that this poor widow has put in more than all; 4 for all these out of their abundance have put in offerings for God, but she out of her poverty put in all the livelihood that she had.

#orthodoxy#orthodoxchristianity#easternorthodoxchurch#originofchristianity#spirituality#holyscriptures#gospel#bible#wisdom#faith#saints

6 notes

·

View notes