#insects of North Africa

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Roll Up with the Sacred Scarab

The sacred scarab (Scarabaeus sacer) is perhaps the most famous of all dung beetles as a symbol of worship by ancient Egyptians. Outside its godly role, this species can be found throughout northern Africa, as well as southern Europe and into western Asia as far as India. In Africa it inhabits both deserts and scrubland, as well as agricultural areas where food is abundant, while in Europe the sacred scarab stays more towards the coast in dunes and marshes.

Aside from its well-known association with religion, the sacred scarab is known best for its association with dung. When a source has been found, individuals roll it into tightly compressed balls known as telecoprids, which can weigh up to ten times their size. These telecoprids are then rolled with the hind legs to an underground chamber where S. sacer strains out and feeds on nutrient-rich fluids, molds, and undigested particles from the ball over several days. In addition to its role as a nutrient recycler, the sacred scarab is also an important source of food for many small mammals, reptiles, and birds.

In its native range, the sacred scarab will mate year-round provided food is abdunant. Males and females work together to form and move a dung ball back to the underground nest; it is during this stage that males will fight each other for control of the ball, while the female will simply follow wherever the telecoprid goes. Once in the next, male and female briefly copulate before the male departs to search for another mate. The female then sculpts the dung ball into a pear shape and lays a single egg in the narrower end, which is then sealed. Her job done, she too leaves to seek out another partner and repeat the process, laying over a dozen eggs in her lifetime.

After a week or two, a single larva emerges from the egg and begins feeding on the dung around it. Over the next 3 months, it will molt up to three times before forming a pupa. About a month later, a fully mature adult emerges and burrows its way to the surface to find a fresh source of food and potential mates. Unlike many beetle species, the sacred scarab is an adept flyer, and will often use its wings to travel between food sources as opposed to walking.

Though the sacred scarab may seem ornate in Egyptian hieroglyphics and jewelry, the species itself is quite plain. Individuals are completely black, and both sexes are indistinguishable from each other. Individuals can range from 1.9 to 4.0 cm (0.7 to 1.6 in) long, and weigh up to 2 g (0.07 oz). One interesting feature is their front feet; unlike other dung beetles, S. sacer doesn't have any. Instead they only have a vestigial claw-like structure that can be used for digging.

Conservation status: This species has not been evaluated by the IUCN, but due to its large population size and adaptability to urban and agricultural expanstion it is considered relatively stable.

If you like what I do, consider leaving a tip or buying me a ko-fi!

Photos

Amadej Trnkoczy

Kev Gregory

San Diego Zoo

#sacred scarab#Coleoptera#Scarabaeidae#scarab beetles#beetles#insects#arthropods#deserts#desert arthropods#scrubland#scrubland arthropods#wetlands#wetland arthropods#urban fauna#urban arthropods#africa#north africa#europe#southern europe#middle east#asia#west asia#animal facts#biology#zoology

133 notes

·

View notes

Text

Animal of the Day for November 25: Argentine Ant (Species Linepithema humile)

The Argentine Ant is a relatively small ant with workers around 2.5mm long, but they make up for this with a fast reproduction rate compared to other ants. Argentine Ants are a widespread invasive species, with supercolonies that spread across nations.

Due to their sheer numbers, they easily wipe out native ants and other insects. However their conquest is challenged in some places by the (also invasive) Fire Ant, which is a natural enemy of Argentine Ants, is much stronger, and happens to also form supercolonies.

#animal of the day#november 25#november#argentine ant#insects#invertebrates#arthropods#south america#north america#europe#asia#australia#africa#kurzgesagt made a video about them

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wool-Carder Bees: these solitary bees harvest the soft, downy hairs that grow on certain plants, rolling them into bundles and then using the material to line their nests

Wool-carder bees build their nests in existing cavities, usually finding a hole/crevice in a tree, a plant stem, a piece of rotting wood, or a man-made structure, and then lining the cavity with woolly plant fibers, which are used to form a series of brood cells.

The fibers (known as trichomes) are collected from the leaves and stems of various plants, including lamb’s ear (Stachys byzantina), mulleins, globe thistle, rose campion, and other fuzzy plants.

From the University of Florida's Department of Entomology & Nematology:

The female uses her toothed mandibles to scrape trichomes off fuzzy plants and collects a ball of the material under her abdomen. She transports these soft plant fibers to her selected nest site and uses them to line a brood cell. Next, she collects and deposits a provision of pollen and nectar into the cell, enough pollen to feed a larva until it is ready to pupate. Lastly, she lays a single egg on top of the pollen and nectar supply before sealing the cell. ... She will repeat this process with adjoining cells until the cavity is full.

These are solitary bees, meaning that they do not form colonies or live together in hives. Each female builds her own nest, and the males do not have nests at all.

Female wool-carder bees will sometimes sting if their nest is threatened, but they are generally docile. The males are notoriously aggressive, however; they will often chase, head-butt, and/or wrestle any other insect that invades their territory, and they may defend their territory from intruders up to 70 times per hour. The males do not have stingers, but there are five tiny spikes located on the last segment of their abdomen, and they often use those spikes when fighting. They also have strong, sharp mandibles that can crush other bees.

There are many different types of wool-carder bee, but the most prolific is the European wool-carder (Anthidium manicatum), which is native to Europe, Asia, and North Africa, but has also become established as an invasive species throughout much of North America, most of South America, and New Zealand. It is the most widely distributed unmanaged bee in the world.

A few different species of wool-carder bee: the top row depicts the European wool-carder, A. manicatum (left) and the spotted wool-carder, Anthidium maculosum (right), while the bottom row depicts the reticulated small-woolcarder, Pseudoanthidium reticulatum, and Porter's wool-carder, Anthidium porterae

Sources & More Info:

University of Florida: The Woolcarder Bee

Oregon State University: European Woolcarder Bees

Bohart Museum of Entomology: Facts about the Wool Carder Bee (PDF)

Bumblebee Conservation Trust: A. manicatum

World's Best Gardening Blog: European Wool Carder Bees - Likeable Bullies

Biological Invasions: Global Invasion by Anthidium manicatum

#entomology#hymenoptera#apiology#melittology#bees#woolcarder bees#nature#insects#arthropods#science#solitary bees#european woolcarder#anthidium#animal facts#cool bugs#cute animals

3K notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you by any chance have any info about House Martins?

Western House Martin (Delichon urbicum), family Hirundinidae, order Passeriformes, found in Europe, Western and central Asia, and much of Africa.

There are 4 species of House Martin, genus Delichon.

They are swallows.

Like many swallows, they make nests on the sides of natural and man-made structures, using mud.

They are migratory, breeding in Europe, West Asia, and North Africa, and wintering in South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa.

They feed on a variety of flying insects.

photographs: Sergio Correia, Michael Palmer, Cesar Gil

#swallow#martin#delichon#hirundinidae#passeriformes#bird#ornithology#animals#nature#europe#asia#africa

250 notes

·

View notes

Text

the mistle thrush is a large species of thrush found in much of europe, in addition to portions of asia and north africa. they are the largest thrush species native to europe. they have soft grey uppersides, and speckled undersides; the sexes have no identifiable differences in plumage. as their name implies, they are crucial to the spread of mistletoe seeds; this bird feeds on insects, seeds and fruits, and prefers fruits and seeds from mistletoe, holly, and yew.

893 notes

·

View notes

Text

Eurasian Hoopoe

This fascinating bird, with its distinctive crest and colorful plumage, inhabits much of Europe, Asia, and North Africa. Its melodious call and ability to catch insects make it a natural ally against pests. Plus, they are very social and love to perform aerial acrobatics.

✨ Fun Fact: Eurasian Hoopoes can live up to 10 years in the wild!

📸: @photography.hinsche

credit: 1 Minute Animals

94 notes

·

View notes

Text

about hellgrammites :3

so my post of these bugs with the little bows has been getting really popular and i got some questions about what they are:

these are hellgrammites, the aquatic larvae of dobsonflies (order megaloptera: family corydalidae: subfamily corydalinae)! not centipedes, but insects. they have 6 true legs at the front. the other leggy things on the back are lateral filaments for tactile sensing and breathing. they also have abdominal gill tufts on their bellies and a pair of spiracles on their butts for the air.

this hellgrammite (eastern dobsonfly, corydalus cornutus) is out on the pavement because they can actually crawl pretty far from the water to find a place to pupate under a log or rock. if you know someone who fishes, they might know about these (as well as where to find them!) because they make good bait. some fishermen even make cool lures based off them!

^eastern dobsonfly pupa!! like beetles, their limbs and other appendages are free unlike the smooth casing of many flies and moths.

as adults, they're generally large flying insects though they don't fly super well. many are also easily recognizable because the males often have GIANT curved mandibles. despite this, they're actually too cumbersome to bite you. females will give you a strong pinch but only if you manhandle them. the adults also only live a few weeks compared to the few years (many insects are like this) that hellgrammites spend as ambush predators under large rocks in cold, fast-flowing streams. because of their specific habitat requirements, hellgrammites' change in abundance in streams can be really important for monitoring stream health.

^male eastern dobsonfly. he is so polite for taking time out of his night to pose for this photo

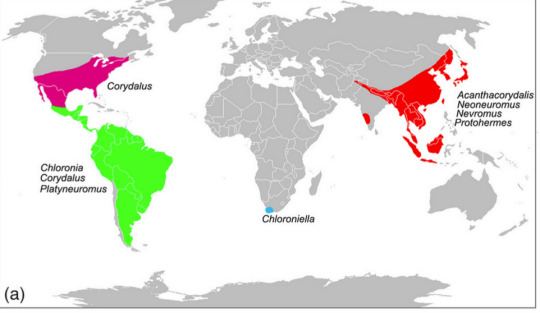

so you know how there's like. 400,000 species of beetles and 180,000 species of moths and butterflies? megaloptera only have 400 species!! and dobonsflies are only part of that group alongside alderflies and fishflies!! while megaloptera as a whole are found on every continent, dobsonflies are absent from huge portions of north america, europe, africa, and australia. globally speaking, they're kind of an uncommon insect. so to my fellow bug nerds in southwest/eastern north america, south america, and eastern/southeast asia, think about your local hellgrammites :3

^figure from jiang et al. 2021 showing global distributions of corydalinae. their wacko distribution is probably the result of regional extinctions since they need specific habitats and can't fly very far.

some more dobsonfly friends from around the world:

^protohermes, a genus of dobsonfly from asia. lemony fresh

^platyneuromus, a genus of dobsonfly from south america. seems like a good listener (they're not actually ears, just extensions of the head, and are probably for sexual display)

^chloroniella, the one genus of dobsonfly in southern africa. tiny!!

^the big boss dobsonfly, acanthacorydalis fruhstorferi from china! it is probably longer than your hand. allegedly the world's largest aquatic insect by wingspan (even tho the adult itself is not aquatic shrug)

87 notes

·

View notes

Text

Animal of the Day!

Brazilian Treehopper (Bocydium globulare)

(Photo in Public Domain)

Conservation Status- Unlisted

Habitat- Africa; Asia; North American; South America; Australia

Size (Weight/Length)- 6 mm

Diet- Sap

Cool Facts- No, those aren’t eyes. The Brazilian treehopper has a distinct protrusion sticking out of their thorax called a helmet. Scientists don’t fully understand why the insects grow these outgrowths, but it could be for a bizarre form of camouflage or dissuading predation. Despite being able to fly, the treehoppers only do so when startled. They prefer to crawl on the underside of leaves as they search for sap. Females lay their eggs directly inside the tissue of a leaf and after a few weeks a nymph emerges. After only a month of life, the Brazilian treehopper is ready to have offspring of their own.

Rating- 12/10 (Of the 3,270 treehopper species, this may be the weirdest.)

#animal of the day#animals#insects#treehopper#friday#november 3#brazilian treehopper#biology#science#conservation#the more you know#cw: insects

534 notes

·

View notes

Text

December 9, 2024 - Green-backed Honeybird (Prodotiscus zambesiae) Found in parts of eastern and southern Africa, as far north as Ethiopia and South as Mozambique, these honeyguides live in forests, often near streams, savannas, and gardens. They eat insects, including beetles, scale insects, and termites, as well as spiders and some fruit and seeds, often foraging in mixed-species flocks. Females lay their eggs in the nests of several species of white-eyes, flycatchers, and other birds.

#green-backed honeybird#honeyguide#prodotiscus zambesiae#bird#birds#illustration#art#water#birblr art

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

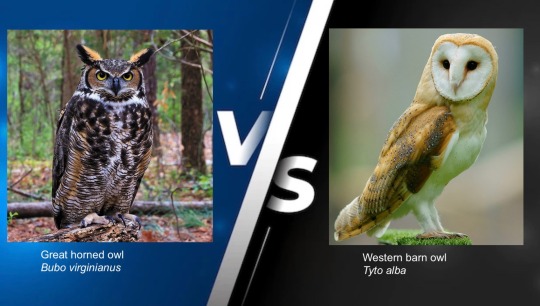

Two popular classics! But who is the Superb Owl?

The most widely distributed owl in the Americas, the great horned owl ranges throughout North America and much of Central and South America. They can be found in almost any habitat. These owls mostly prey on rodents and lagomorphs, but are opportunistic hunters and will take anything they can catch, including smaller owls. They hunt by watching from a perch. Regarding their ecological niche, they are sometimes described as the nocturnal equivalent of red-tailed hawks. Great horned owls nest earlier in the year than most other raptors. These owls are very long-lived, with a typical lifespan of around 13 years in the wild (with a record of 28) and up to 50 in captivity!

Western barn owls live throughout Europe as well as much of Africa and the Arabian peninsula in a wide variety of habitats, but most especially favoring open woodland and grasslands. These owls mostly eat small mammals such as rodents and shrews, but will also eat birds, amphibians, lizards, and insects. They hunt by flying slowly over ground and pouncing when movement is detected. Western barn owls are usually monogamous, mating for life. After fledging, young remain with their parents for only about a month. Since barn owls have relatively high metabolic rates, they eat proportionally more rodents than other owls and are thereby appreciated by farmers as effective pest control.

511 notes

·

View notes

Text

December 21st, 2023

Varied Carpet Beetle (Anthrenus verbasci)

Distribution: Cosmopolitan; found throughout North America and Europe, as well as the Near East, North Africa, South America and northern and eastern Asia.

Habitat: Most commonly found on flowers, as well as plant and animal-based materials; common indoors, in houses, flour mills, warehouses and attics, as well as under siding, and in bat roosts and bird nests.

Diet: Larvae feed on natural fibres, such as keratin and chitin, including dead animals and insects, animal hair, feathers, natural fibres like silk, wool, leather and cotton, carpet fibres, linens, napkins, curtains and other household items, as well as stored food. Adults feed on the pollen and nectar from flowering plants.

Description: While they are pretty in their adult form, varied carpet beetles are serious pests inside homes, universities and museums. Their caterpillar-like larvae have been known to decimate biological collections belonging to museums and universities, and due to their extremely varied diet, they're known to wind up fairly frequently inside houses.

The varied carpet beetle was the first insect studied for its circannual cycle, with environmental conditions controlling larval development, which may last up to two years. Temperature seems to be the most limiting factor to larval development, but relative humidity and food availability may also play important roles.

Images by Jean-Raphaël Guillaumin (adult) and André Karwath (larva)

86 notes

·

View notes

Text

Soaring with the Tarantula Hawk Wasps

Tarantula hawk wasps, or more simply tarantula hawks, are a sub-group of the spider wasp family Pompilidae, famous for both their painful sting and their tendancy to predate exclusively on tarantulas and large spiders. The tarantula hawks encompass two genuses. Pepsis, which includes about 133 species, is found exclusively in the Americas, and occupies a range of habitats including rainforests and deserts. Hemipepsis has 180 species and is found in tropical regions on every continent.

Although tarantula hawks get their fame and their name by hunting tarantulas, only larval wasps actually feed on arachnids. The adults actually consume nectar and fermented fruit, like other hymenoptrids like bees and hornets. In fact, many species of flowers rely exclusively on pollination by tarantula hawks. The painful sting they carry is enough to keep away potential predators. In general, however individuals are not aggressive and won't utilize their defenses unless provoked. In addition, though the sting is extremely painful to humans, it is not venomous and doesn't require medical attention unless it triggers an allergic reaction.

Members of both Pepsis and Hemipepsis are active during the daytime, and spend most of their time foraging. In the summer, females will also actively hunt for prey in which to lay their eggs, while males will practice a behaviour called 'hill-topping', in which they perch on a tall flower or shrub and wait for reproductive females to pass by. Males can become defensive of their territories, but lack stingers as they have no need to hunt.

When males locate a receptive female, they engage in elaborate aerial dances to entice her to mate with them, sometimes reaching heights of over 305 m (1000 ft). After a male and female mate, they go their seperate ways; males to find another partner, and females to find a source of prey. Once a female has located a suitable tarantula, she stings it-- the venom she injects paralyses the arachnid but keeps it alive. She then drags it back to a specially prepared burrow, where she lays her egg inside the spider and covers the burrow.

The egg hatches about 3-4 days after being laid, and begins consuming its host. The sex of the larva depends on fertilization; unfertilized eggs produce males, while fertilized eggs produce females. Over the next several weeks, the larva will consume the tarantula in its entirety, keeping it alive as long as possible and going through several molts. Eventually the larva forms a pupa, and 2-3 weeks later emerges as a fully mature adult. Both sexes have fairly short lifespans: males only live for a few weeks, and females only live for 4-5 months, but in that time they will produce over 13 eggs.

Tarantula hawks are among the largest wasps in the world. The very largest can grow up to 6.5 cm (2.5 in) long, and have wingspans to match. The females' stinger is equally impressive, reaching a length of up to 12 mm (0.47 in). Species can come in a variety of colors, most commonly orange, blue, or black, with bright orange or red wings. These features, combined with the tarantula hawks' long, hooked claws and large eyes, make members of any species easily distinguishable from other wasps.

Conservation status: No species of tarantula hawk wasps is currently threatened, although many species are facing habitat destruction and a decline in their primary prey. One species of tarantula hawk, Pepsis grossa, is the official insect of the state of New Mexico in the United States.

If you like what I do, consider leaving a tip or buying me a ko-fi!

Photos

Hemipepsis ustulata by Gary McDonald

Elegant tarantula hawk wasp (Pepsis menechma) by Will Stuart via iNaturalist

Hemipepsis tamisieri by Debbie Hall

#tarantula hawk wasp#hymenoptera#Pompilidae#spider wasps#wasps#hymenoptrids#insects#arthropods#tropical fauna#tropical arthropods#rainforests#rainforest arthropods#deserts#desert arthropods#africa#north america#south america#asia#australia#europe#animal facts#biology#zoology

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fossil Novembirb 5: It's Getting Hot In Here

Sandcoleus by @drawingwithdinosaurs

Global warming is nothing new for the planet, and even in the Cenozoic we've had our share of rapid warming events - the most notable one being the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM). This event, taking place 56 million years ago, was the result of rapid carbon release from the North Atlantic Igneous Province - aka, a volcano exploded, released a bunch of greenhouse gases, and suddenly global temperatures jumped somewhere between 4 and 10 degrees Celsius (depending on location) in a very short period of time - sound familiar?

Given the obvious parallels to the current day, this event has been studied extensively, though only in a few spheres. We know that plants changed dramatically, with broad leafed plants spreading around the world and turning it into a global tropical forest, even at the polls - leading to interesting adaptations towards the strange light cycles at high latitudes. The world was wetter, and greener, and the change lead to the evolution of new herbivory methods in insects. Mammals got smaller, spread everywhere, and diversified. A mass extinction occurred in the oceans, with microorganisms seeing a larger drop in diversity than during the end-Cretaceous extinction. More calcified algae flourished in the more acidic waters.

But what happened to birds?

Anachronornis by @otussketching

Turns out, we're not quite sure. Bird fossils before the event are rare, and after are so diverged and varied that it's difficult to know what happened because of the event, and what happened before and just didn't fossilize. Luckily, scientists (... me) are on the case! And there were a few ecosystems that straddle the time around the event, such as the one for this post: the Willwood Formation.

This ecosystem in Wyoming takes place over the late Paleocene through the early Eocene, covering the entire PETM period. And while it showcases many different aspects of this transition, we're of course here for the birds! Not only was there Gastornis, because it was a ubiquitous presence in the Northern Hemisphere following the PETM, there were also many other weird early kinds of birds, all across the avian family tree.

Paracathartes by @drawingwithdinosaurs

Sandcoleus is one of the more notable tree birds from this ecosystem, being a relative of living mousebirds but in North America (rather than Africa, where they are found today). In fact, lots of different tree birds were present, indicating that the current dominance of Passeriformes - so called "perching birds" - was not always the case. In fact, Paracathartes was also present - our first Palaeognath, an early Lithornithid! - and it also may have been able to perch in the trees, and certainly seems to have been a decent flier.

There were also Geranoidids like Palaeophasianus and Paragrus, which were once thought of as pheasant-like and crane-like respectively, but may now actually be Palaeognaths - and some of the earliest known flightless ones to boot! That said, said, other than being long legged flightless birds, we know little about their ecologies - they may have been herbivorous, and as tropical forest dwellers, could have had similar lifestyles to the living cassowary.

Primoptynx by @otussketching

And, of course, there was also Anachronornis, the half-screamer-half-duck thing, showcasing how waterfowl were experimenting with a variety of different niches during this ecological explosion. And the large variety of new small mammals didn't go unnoticed either - while other early owls are known from Europe, Primoptynx was both the oldest and the biggest, probably thanks to all the new small mammals to eat! There were also possible ground raptors, similar to Bathornis, though they have not been named.

While there are many questions left to answer, it is clear that the PETM had a major effect like it did on everything else on the planet during that time - and the tropical ecologies that they evolved in during the early Eocene would have many implications, especially for where different clades live today!

Sources:

Houde, P., M. Dickson, D. Camarena. 2023. Basal Anseriformes from the Early Paleogene of North America and Europe. Diversity 15 (2): 233.

Mayr, 2022. Paleogene Fossil Birds, 2nd Edition. Springer Cham.

Mayr, 2017. Avian Evolution: The Fossil Record of Birds and its Paleobiological Significance (TOPA Topics in Paleobiology). Wiley Blackwell.

120 notes

·

View notes

Text

The taxonomy of Sly Cooper: Part 1

In which I will be using my higher than average knowledge of zoology to attempt to accurately identify the specific animal species of various characters in the Sly Cooper franchise, sharing some interesting facts about them along the way.

I'll start with the four most prominent characters; Sly, Bentley, Murray and Carmelita. If people are interested I'll be making similar posts for the other characters.

WARNING: I will be unleashing my inner Animal Kid™ in this post. Verbose language and casual dropping of scientific names abound

Starting off with Sly himself, I like to believe that he is a crab-eating raccoon (Procyon cancrivorus). This quirky little carnivoran is found throughout South America and parts of Central America. Despite its name, it has a varied diet including crustaceans, fish, small turtles (watch out Bentley), fruits and nuts.

As opposed to the common raccoon (Procyon lotor), which can be a bit of a chubby little furball, the crab-eating raccoon has shorter and sleeker fur, and its slender proportions makes it an even better climber than its northern cousin. All of this makes it a perfect fit for Sly in my opinion. Also, its jaws are more defined and powerful than those of common raccoons, which i think is very appropriate for Sly's dashingly chiseled jawline.

Bentley was a little bit tricky to identify, as he seems to be a rather generic looking turtle. However, a closer inspection of his shell reveals his kinship.

This rather flat, ring-marked shell has led me to conclude that he must be a diamondback terrapin (Malaclemys terrapin).

Like Bentley, diamondback terrapins are very resourceful animals, being able to survive in both fresh and saltwater habitats, where they priamrily feed on insects, fish, crustaceans, and mollusks. They can be found in brackish marshes and mangrove forests thoughout the east coast of North America. The beautiful diamond-like markings on their shells are unique for every individual. Some people believe that the markings indicate the turtles age, like growth rings on a tree.

I have seen others identify Bentley as a box turtle, which I don't get at all. Box turtles are distinquished by their bulky BOX-shaped shells. The diamondback on the other hand has a flatter, more streamlined shell, which makes it very mobile in the water. Though, I guess this makes it all the more ironic that none of the core members of the Cooper gang know how to swim, despite all of them being based on semi-aquatic animals, but I digress.

Speaking of semi-aquatic, I firmly believe that Murray is a pygmy hippopotamus (Choeropsis liberiensis). Not just because I have an affinity for these animals, but I can back this up by examining Murray's design and characterization.

Murray has a very stocky and robust body (friend-shaped), with a relatively short compact snout, not unlike the pygmy hippo. This is in stark contrast to the common hippo (Hippopotamus amphibius) which has a very large ungainly (and less "cute"-looking) head in proportion to its body.

I think the main reason that Murray's design in the unfinished Sly-movie was so unappealing, is that they based his proportions too much on those of a "realistic" common hippo.

Anyways, pygmy hippos can be found in scattered populations across forests along the west coast of Africa, where they feed on broad-leafed plants and fallen fruits. They are extremely rare and endangered due to habitat loss and the bush-meat trade.

Unlike the infamously aggressive common hippo, the pygmy hippo is a rather docile and shy animal, whose first instinct when threatened will typically be to run away and hide (not unlike Murray in the first game) though it can defend itself with its powerful jaws. True to its name, the pygmy hippo is less than a quarter of the size of its larger relative, with the biggest specimens weighing in at about 600 pounds (which is lighter than some domestic pigs).

Moving on to Carmelita, there's no getting around the fact that she is supposed to be a red fox (Vulpes Vulpes), what with her strikingly orange fur colour and long bushy tail. The red fox needs no introduction, being one of the most succesful and abundant carnivorans on earth (besides domestic dogs and cats), with a range covering basically the entire northern hemisphere (aside from the Arctic), along with a worryingly invasive population in Australia.

Even though Carmelita is often characterized as a spicy latina, (being inspired by latina actresses such as Selma Hayek and Jessica Alba) Latin America is one of the few places on earth not inhabited by red foxes. These areas of course have their own native fox species. I considered the possibility that she could qualify for being a gray fox (Urocyon cinereoargenteus), a kit fox (Vulpes macrotis), or even a culpeo (Lycalopex culpaeus), but the thing that really cements her as being a red fox is her jumping ability.

Red foxes are able to jump up to 2 meters into the air, which is four times their shoulder height of about 50 cm. This would be the equivalent of a 6-foot person jumping 24 feet in the air, which feels appropriate given some of the insane feats of athleticism we've seen Carmelita pull off throughout the series.

41 notes

·

View notes

Note

Haiiii!!! I just found out about this bling but it is so cool!!!!!! I present to you: the fennec fox ❤️

Animal of the day: Fennec fox!

The fennec fox is native to the deserts of North Africa. It has unusually large ears which help it to dissipate heat and listen for underground prey!

They are the palest of all the foxes, giving them excellent camouflage against the desert sand. They are capable of going long periods without water, instead hydrating through their food! They eat insects, rodents, lizards, birds, eggs, roots, fruit, and leaves.

They are the smallest of all the canids, growing up to 16 inches (40 cm) long!

64 notes

·

View notes

Note

Can we have a little info on all the ones you haven't drawn yet, even the Maybe Canon? ones? There's a few there I don't recognize at all, and I'm curious.

Sure thing!

Not Drawn Yet:

The angont – a serpentine dragon from North East USA and Eastern Canada

The Australian rainbow serpent – exactly as the name implies. Rainbow serpent from Australia.

Chicken headed serpents – I didn’t know about this until I read @a-book-of-creatures excellent article on Crowing Crested Cobras. I need to actually research these myself, I read the article, thought “these are cool, I will add them to Dracones Mundi”, and then didn’t read/write/draw further (yet!!!!!).

The grootslang or ‘Great Snake’ is from South African folklore.

The kongomato, a winged dragon from the Congo.

The kurrea, a crocodile serpent from Australia

The makara, a creature like a crocodile mixed with an elephant from south Asian folklore: for Dracones Mundi I am making it a relative of the phaya naga.

The markupo is a large red-crested serpent from the Phillippines.

The ropen is a glowing, flying dragon from New Guinea – I might make it a relative of the glowtail in Dracones Mundi lore

Taniwha are water spirits from New Zealand – in Dracones Mundi I am making them a species of sea serpent

Wanizame or wani are sea dragons from Japanese folklore.

Vaguely planned dragons:

The Antarctic Jaculus – dragon I 100% made up, because I was bragging about how Dracones Mundi has ‘dragons all over the map’ and a little snide voice in my head said “what, even Antarctica?” and as Antarctica is not inhabited by people for most of the year it was difficult to find folkloric serpents, so I made up another sea-bird inspired dragon. Both cliffwyrms and Antarctic Jaculus have diving behaviours, which is why their inland cousin, the jaculus, evolved it's divebombing hunting strategy.

Butterfly winged serpent; very small winged serpent with butterfly wing patterns, 100% fictional with no mythology behind it (I mean. There is Pyrausta. But I think Pyrausta would be a different sort of animal, an actual insect, in the Dracones Mundi world, so butterfly winged serpents are not pyrausta)

Oceanic Turtle Dragon; I have the Asian turtle dragon, the European turtle dragon and the Congo Plated Dragon. Running around looking for folklore on ‘turtle dragons’ you end up stumbling into some fantastic artwork for Dungeons and Dragons involving their take on turtle dragons and something about a sea-turtle inspired dragon is really fun and cool. I will see if I can do something unique and different with this concept. If not, I will not be including the oceanic turtle dragon.

Pterosaur dragon; I made dinodrakes as dragons inspired by retro palaeoart of dinosaurs, and I thought “hmm. What if I did the same for retro pterosaurs?” – it turns out there’s a lot of cryptozoology in Africa I could research into for placing these pterosaur dragons somewhere on the map.

Snapdragons; snapdragon flowers need to be named after dragons, so I have a fun idea for a small cave dwelling dragon with petal-like frills and barbels that it uses to sense it’s environment. They also can emit an eerie blue warning glow from their mouths, not dissimilar to the glow of brandy on fire in the Victorian game ‘snap dragon’.

29 notes

·

View notes