#infocom

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

USA 1993

#USA1993#INFOCOM#ACTIVISION#ADVENTURESOFT#ADVENTURE#IBM#AMIGA#AMIGA CD32#ARCHIMEDES#SIMON THE SORCERER

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

The long-awaited Zork LP has begun! This is the first of three parts, making good on the pledge we made on Ranged Touch's 2022 Prepare to Give stream benefitting The Brigid Alliance.

A lot of people are more familiar with this game than we are, and have said some very intriguing things about the sequels. Grant has promised to play (not Let's Play) Zork 2 for himself if another $5,000 is raised for The Brigid Alliance between now and the end of the day part 3 is posted. Just share an image of your donation confirmation and we'll total them up. At time of posting we're over 25% of the way there already!

#chip and ironicus#let's play#general ironicus#chip cheezum#Ranged Touch#Zork#Zork I#interactive fiction#Infocom#pngtuber#Hank the Chog#Combining Mecha#Dilbert#The Brigid Alliance#Youtube

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

A truly fascinating version of hitchhiker's guide we are presented with in the infocom game, where Ford is just Gone most of the time, Arthur displays behaviour of an average dragon or a racoon, hoarding all the many random items he probably shouldn't touch and exploring every corner of whatever location he's tossed into, and Marvin is so depressed he exudes an aura powerful enough to make you depressed too.

#i havent finished it yet because hard game but i really liked the character traits it gave Artur because of the necessities of being a game#i think him being a but weird and racoon coded like that is incredibly charming#ford prefect#arthur dent#h2g2#marvin the paranoid android#infocom#the hitchhiker's guide to the galaxy

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

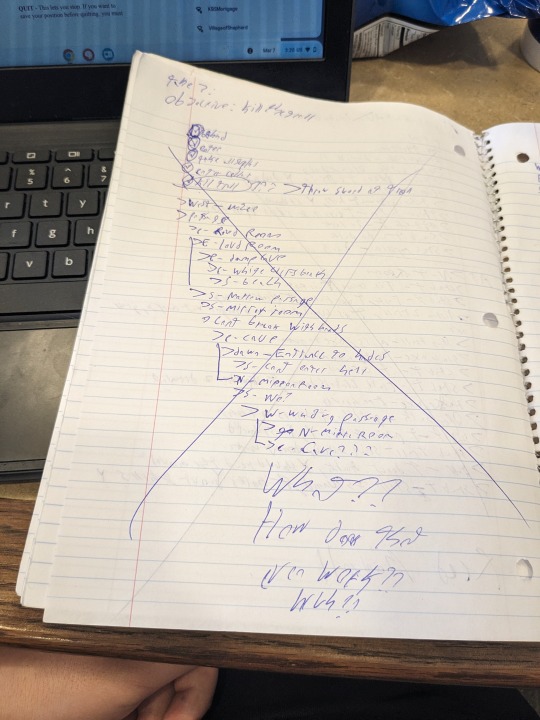

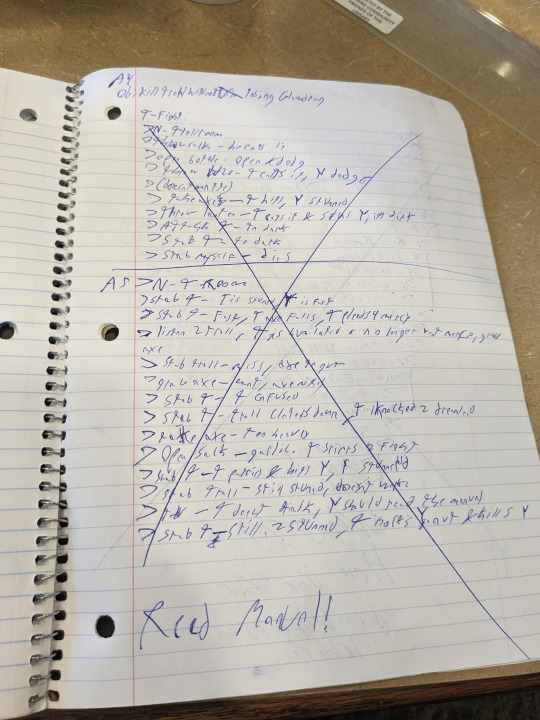

My past six attempts at playing Zork

Got lost

Got lost again, and the map wasn't making sense

Gave up on map, tried new method, ineffective

Refined previous method, introduced objectives, got very confused

Attempt four and five I just tried a lot of things out in a further refined system while fighting the troll. Had a new objective which I did not achieve cause I was spending too much time trying stuff out. Game says I should re-read the manual, I never read it once in the first place so yeah I should

Will update after I work on midterms first

#Zork#How is there no tag for Zork?#Zork 1?#The undiscovered underground?#Gosh Zork fandom#We're are you people#It's not that old#old games#old computers#microsoft#infocom#Visicorp#i don't know how to tag this#Edit: there is a Zork tag

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

Studies of ZIL, Part 1

by Max Fog

Infocom is well-known in the interactive fiction community for classics such as Zork, Deadline, and The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, as well as more experimental pieces such as Trinity, Plundered Hearts, and A Mind Forever Voyaging. In the 1980s, Infocom became a fundamental part of the history of IF and shaped the IF world as we know it today. The first way they did this was probably the most obvious. The games that Infocom made pushed boundaries in every direction – from classic puzzle games like Zork, to puzzleless atmospheric types like A Mind Forever Voyaging, all the way through to Choose Your Own Adventure (CYOA) games like Journey (which, while unpopular both at the time and now, was an example of early point-and-click CYOA). The games they released did wonders in introducing over a hundred thousand people to the entire broad and diverse world of interactive fiction, and inspiring people to make their own text games. The second way is more obscure, but just as important. It’s the Z-machine.

Read the full article on The Rosebush.

The Rosebush | Submissions | Mastodon

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

One of my A Mind Forever Voyaging pieces got mentioned in Critical Distance's "2023 in videogame blogging." Don't see a lot of text game writing out there in mainstream video game discourse. Feels good!

It has a Kierkegaard quote and everything, very classy.

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Lost Treasures of Infocom I & II

"Once you've defeated alien armies, solved murders, and overcome curses, real life seems like child's play." (PC Games, Feb. 1993)

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

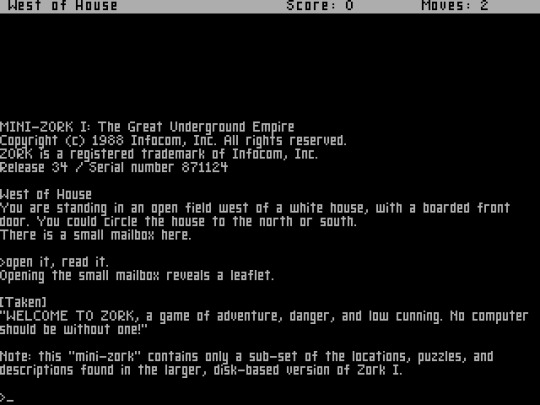

Kinda funky how "open it, read it" works. First, the automatic listing of things in the room description sets "it" to the mailbox. I enter two commands on one line. The first is parsed as "open mailbox", and the default "open container" handler sets "it" to the leaflet. Then the second command is parsed as "read leaflet", which causes an implicit take.

It makes sense when you think about it, but "open it, read it" on its own... not as much I think.

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

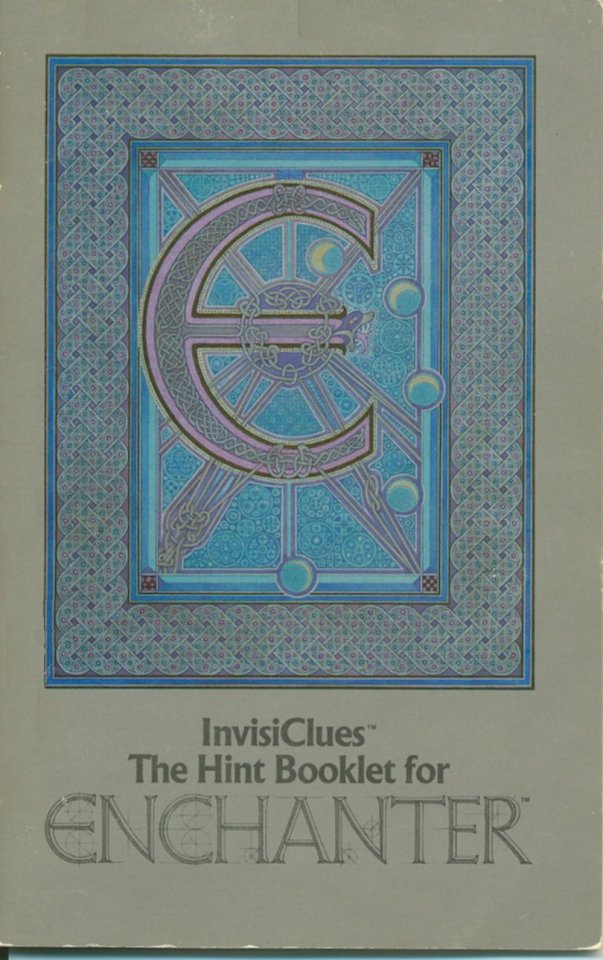

Enchanter Invisiclues Booklet Cover

#infocom#fantasy art#zork#retro fantasy#rpg art#retro rpg#retro computing#retro tech#retro aesthetic

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

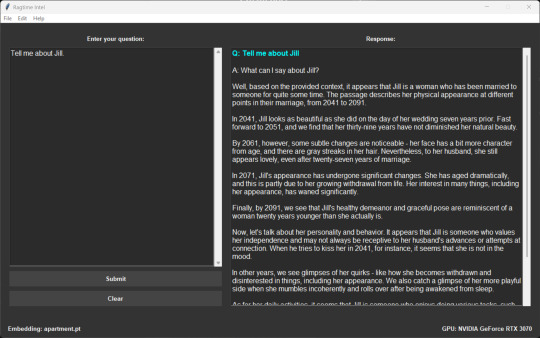

Sharing some AI development observations with the community using Infocom’s source code…

Been playing around with Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) on Infocom’s ZIL source code, specifically A Mind Forever Voyaging. I set up a LoRA-embedded RAG model (using the ZIL source code) on top of Llama 3.2, running everything entirely locally, to see how well it could extract relevant information from the game’s original source code - no cloud processing, just local inference. Here’s an interesting result: I asked about "Jill," a fictional character from the game, and the system pulled details directly from the source, surfacing descriptions of her appearance and personality across different points in the story. Then, I asked about "Jill's paintings" and got back a breakdown of her work over the decades, reflecting how her artistic style evolved in the game’s narrative. The responses match exactly what’s encoded in the game’s logic, which makes me wonder how well this could work for analyzing or even reconstructing narrative structures from classic text adventures. Not really sure where this leads, but it’s been interesting seeing how AI interacts with something as structured (yet open-ended) as ZIL. Just sharing some observations from the process.

#AI#artificial intelligence#Infocom#ZIL#RAG#Retrieval Augmented Generation#AMFV#A Mind Forever Voyaging#LORA#Enhancements#Zork#Pixel Crisis

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

USA 1993

#USA1993#ACTIVISION#INFOCOM#ADVENTURE#IBM#AMIGA#APPLE#MACINTOSH#PLANETFALL#DEADLINE#ENCHANTER#BALLYHOO#ZORK I THE GREAT UNDERGROUND EMPIRE#ZORK II THE WIZARD OF FROBOZZ#ZORK III THE DUNGEON MASTER#SUSPECT#SUSPENDED#INFIDEL#THE HITCHHIKER'S GUIDE TO THE GALAXY#STATIONFALL#STARCROSS#MOONMIST#SPELLBREAKER#LURKING HORROR#THE WITNESS#BEYOND ZORK THE COCONUT OF QUENDOR#ZORK ZERO THE REVENGE OF MEGABOZ#BORDERZONE#PLUNDERED HEARTS#BUREAUCRACY

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Forty years later and I still remember being stuck outside the engine room for a week because, like a fool, I trusted the game narration.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lane Mastodon in an Infocom ad (circa August 1988)

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Inside Theater

This is a movie theater unlike any you've ever seen! The seats are wide, deep and comfortable. The aisles are spotless. The air is clear of smoke, and the screen is dramatically large. A chill goes up your spine as you realize how alien your universe has become.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

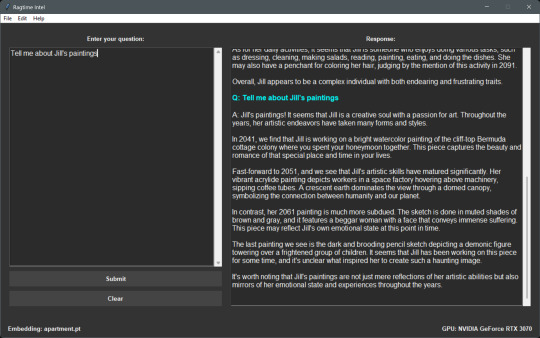

Review of Infocom's 1981 text adventure, Zork II: The Wizard of Frobozz I forgot to mention that I won a Commodore 64 version of this game at Jason Scott's event in Portland back when he was showing his text adventure documentary (which I kickstarted: Coin #359.

4 notes

·

View notes