#in general i think a big issue with magne from what little we know of her is that her reason for joining the lov was fighting back against

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

I don't have much to say about Magne other than there was an Attempt, but. That time when Twice and Toga got angry with Overhaul for misgendering her was already indicative of what I'm going to get at in a sec, and obviously it was especially relevant because it was a direct show of respect and support from people who very clearly cared about her (and who called her big sis already as it was!!) (×2 imo because Twice was intentionally written to be the readers' insight into the LOV, and the character with whom they were supposed sympathise with the most at/since the beginning, so it's especially important that the first one who spoke up was him), but the story's progression (especially in recent years) is what most assures me that despite a rather poor execution (definitely not the best, but also certainly not the worst) Horikoshi did mean well with her. "People bound together by the chains of society always laugh at those who aren't" :(

#^ when she quotes her friend. like had the manga not gone on like it has that could have very well been a generic#We Live in a Society moment. but it wasn't. and that's what's comforting tbh#in general i think a big issue with magne from what little we know of her is that her reason for joining the lov was fighting back against#a tangibile real world issue (transphobia) vs all the other villains. whose situations Are partially real world issues as well#(eg child abuse) but they also very much present fantasy elements to them (eg toga's treatment due to her quirk)#and i'm not saying this as a justification for killing her off but. when you're writing a superhero comic with a target audience of young#cishet men it is much easier to present them with fantasy solutions to fantasy problems. again not that i think it's right!!!#but i do assume that horikoshi's thought process was more or less this. like. tiger is there alive and well#but he passes and was confirmed to be trans only via word of god so his identity has no bearing on the story itself#while magne's did. which doesn't make tiger's transness any less ''real'' than hers ofc but again i think it was a matter of what horikoshi#could actually deal with (fantasy problems) with the average readers that he has. it sucks all the way around.#which begs the question. ''why create her character in the first place then'' to which i answer: i don't fucking know man#bnha#animanga#mytext#in general. i've seen lots of people do this even with eg toga and her bisexuality (and when it comes to her i completely disagree but w/e)#but. authors who want to depic queer characters in good will but make mistakes or do it awkwardly or anything else#should Not be put on the same level as actively queerphobic authors. at all. do criticise what's worthy of constructive#criticism when you see it but don't even pretend that those two are remotely the same thing#(jic i didn't explain myself well bc i don't think that i did. what i wholly disagree with is that ''toga is a bad bi stereotype''.#i am bi people and i disagree!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

13 notes

·

View notes

Note

What are your personal thoughts on the theory that Lilith owns Alastor's soul?

I think it could be possible! Not for certain, but definitely a possibility (or a really big red herring). I've been here since the Pilot's trailer came out and I ate every detail I could for years, and that Pilot, unlike Helluva, is still considered to be canon. I look at all the little details. Skip to the bottom for the bare bones opinion lol, I'll TLDR it for you.

Alastor showed up right after Charlie's brokenhearted phone call to Lilith where she began to express doubt in her dreams. He immediately vouched to help, that was his goal for arrival. Yeah, that could just be him chasing his own interests to solve his chronic case of ✨ SHEER ABSOLUTE BOREDOM ! ✨ But then there's a scene where he's looking at the Magne / Morningstar family portrait in the lobby and he focuses particularly on Lilith.

Gets the brain tickling. Showed up right after Charlie's phone call to Lilith and now he's eyeballing a portrait of her? Hm. Okay.

2. It gets a little funnier. During Alastor's reprise of "Inside of every demon is a rainbow", you get this: Two apples and then boom, a human deer skull. While the apple is part of the Morningstar family insignia, it's also a really big symbol for Lucifer in the Hellaverse in general.

Interrupting something there, Al? Seems to be a repeating ordeal.

youtube

I tie this scene with Episode 5 and suddenly, oh - is that connected? Because weirdly enough, Alastor, who has never met Lucifer before, immediately locked in on that man with animosity. It was on sight the second he stepped through the door, the SECOND. His eye is twitching. Lucifer is the reason he drops his first canonical F-bomb. Why? They have never met before this moment.

Going into some headcanon territory mixed with canon information.

What's canon is that Alastor is a mama's boy, and we know that Lucifer was a bit of an absent father throughout Charlie's life. Depression eats away at you like that, you shelf yourself off into self-isolation even when you have loved ones. Charlie was the one to seek him out and even mentioned:

"When I was young, I didn't really know you at all. I always felt so small."

and then earlier in Episode 5, she says:

"We just have never been close. After he and mom split, he never really wanted to see me. He calls sometimes, but only if he's bored or like, needs me to do something."

Entertain the idea of Alastor being in a contract with Lilith. We don't know what his father was like, but we know he favored his mother. Imagine this mother who has split from her husband shares the fact that her daughter's father is distant and Charlie feels that distance, and it's effected her negatively ( "daddy issues" ).

Alastor is someone who seems choosey about the company he keeps, the only genuine relationships that we know he has is with Mimzy and Rosie. He seemingly considers the Hotel to be a form of entertainment and nothing more, he has no emotional attachment to anyone inside. That said, he's a man with morals. He's a southern man who doesn't stand for the mistreatment of women and will resolve such issues through very violent means.

I think the idea of an absent father puts a bad taste in his mouth. You put that father in his close proximity, and that father just so happens to be an enormous power figure who could end up being a crucial part to this Hotel, and you could wind up with one very irritated deer who wants to take that man down a peg or ten. Viv said he has a weird sense of morality when it came to his serial killings, he was similar to a serial killer character named "Dexter" who killed other criminals. That paired with the comic gets my brain percolating with this headcanon / theory.

A man with a soft spot for his mother being in a contract with a mother who loves her child very much and potentially vents about the absence of the girl's father.. He might not care for Charlie, but he has his twisted moral compass. Lucifer's presence rubs him the wrong way, so he deals with it in his sassy way and tries to keep favor with Charlie. He's being petty without being violent (one he can't handle the devil, two that would mess things up with the Hotel to get into fisticuffs with his business partner's father who is there to help).

I do think Lilith sent him to watch over Charlie. I really do. She's not there, but someone who is contracted to her is, and he has the means and ability to help support her dream. He has his own plans toiling in mind, but he follows her command.

That is all headcanon mixed with the tidbits of info that we have about him, mind. Theory within this theory, lol. Grain of salt.

3. Of course, the seven year absence. Lilith's been gone for seven years, Alastor was gone for seven years. Big sign for a red herring, but also fits into this theory like a glove.

tl;dr: My thoughts are that it's possible and I see the path laid out for it. I also understand that it can be a massive red herring. Lilith and Alastor could still have some sort of connection outside of the contract, because I think regardless of what it is, those two do know each other in some way or form.

Personally, I like the idea of Alastor being contracted to Lilith and softly involve it with my Lily. But, I've been flimsy about it and considering dropping it. It's a very loose detail, I just really like the idea of him being her personal two-way walkie talkie while she's in Heaven. Her cellphone doesn't work, but her spiritual connection to Alastor does.

#(( this is a whole bunch of babble just to say 'i get it and i dig it but also i see why it might not also be a thing.' ))#(( sorry for the word vomit ))#☾ ⛧ ☽ anonymous.#☾ ⛧ ☽ asks.#☾ ⛧ ☽ ooc.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

To talk about Twice and villainy is to talk about class and criminality (I)

(Masterlist)

In contrast to the fantastical world that surrounds him, Bubaigawara Jin’s backstory, revealed in chapter 229, is completely unexceptional. Jin’s backstory is about class. Throughout this series, a sci fi fantasy where almost all the cast have superpowers, we are introduced to characters who’ve struggled with their Quirks, whether having one or not having one, whether having one that’s powerful or weak, whether they have Quirks that are stigmatized or not. Most of the series handles its sci fi prejudice in this way, by substituting real life characteristics like ethnicity (hero Ryukyu is of Ryukyuan ethnicity and from the colonized Ryukyu islands [source]), gender-based discrimination (including misogyny and transphobia), ability (Aoyama, Dabi, and other characters to a lesser degree have physical difficulties using their Quirks), and stigmatized physical traits (as several mutant characters mention being discriminated against) with Quirk conflicts. Ryukyu’s ethnicity, Rock Lock’s race, Magne’s transness, all the misogyny, and the real life disabilities of many characters who are missing limbs are given minimal or no attention, as these conflicts are replaced with Quirks-as-metaphor.

In this fantastical world, where we’ve supposedly left behind our prejudices about race and ethnicity, gender, disability, and so forth, and replaced them with prejudices about Quirks and Quirk compatibility, Horikoshi made the decision to make Jin’s backstory about class as we understand and live under it today. His backstory stands out as one that is utterly banal. Although Jin’s Quirk comes in later, it’s hardly the driving force of his struggle, because what he’s faced with is simply the unfeeling machinery of capitalism and the state apparatus. There’s no involvement from Quirks or Quirk society here; the world that starts Jin on his downward spiral is one that’s inextricable from our own, one that any of us (some more than others) are vulnerable to. That is to say, he didn’t become a criminal because he had an awesome Quirk that made him egotistical (or whatever people think criminals are motivated by), he became a criminal because his circumstances left him with few other ways to seek fulfillment, and possibly to survive. His Quirk was only a balm to the harm already inflicted on him by the economic realities of futuristic (and simultaneously contemporary) Japan.

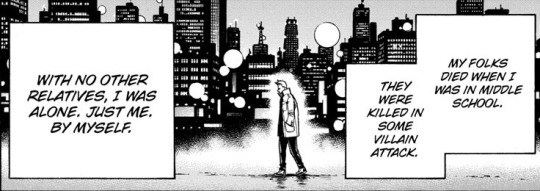

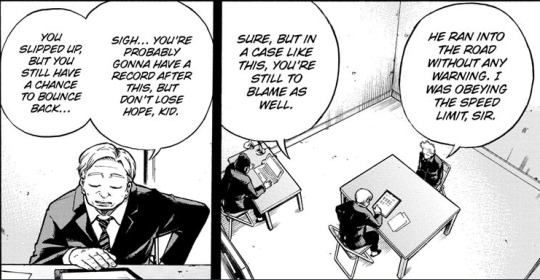

A quick recap of Jin’s backstory from chapter 229: His parents, due to a villain attack, died when he was in an unspecified year in middle school (it seems ironic, and another example of BNHA’s cyclical events, that Jin himself eventually dies at the hands of a hero). At 16 years old, Jin was already working. He got into a traffic accident, although he was obeying the speed limit, and broke someone’s arm. His case was prosecuted and likely resulted in a record, but the officer in charge suggested that he may be able to “bounce back”; however, the person injured in the accident turned out to be one of his workplace’s clients, and the clients’ outrage resulted in his termination from his job. Eventually, isolated and lonely, Jin used his Quirk to become a villain, and it’s implied in the depicted panels that he mainly stole. An indeterminate amount of time after becoming a villain, Jin’s clones turned on one another, resulting in a bloodbath that traumatized Jin and resulted in split personalities. After this incident, he turned to Giran for help, who in turn introduced him to the League of Villains.

Systemic barriers

So why couldn’t Jin bounce back, as suggested by the officer? The reasons are many and diverse, not all of them stated in-text. I believe Jin’s specific circumstances merit some evidence from real-world Japan today, since there’s no statement nor implication that these things have changed in these respects, and because this is the frame of reference that Horikoshi and many of his readers are working with. In order to tap into the spirit of the work, it requires an examination of the circumstances and conditions under which the writers are creating, a recognition and acknowledgment of the social issues that may have shaped and influenced their outlooks. Thus, I think it’s important to contextualize Jin’s past not simply as a self-contained example of inequality in BNHA, but as a narrative that ties into the societal concerns of real-world Japan.

The alternative care system.

This describes the system of institutions and fostering that cares for children who are unable to live with their parents (whether it be due to circumstances like neglect and abuse, or because of the parents’ deaths). In 2014, nearly 90% of children in alternative care lived in residential facilities as opposed to with foster parents (which has its own issues); these rates are much higher than in other industrialized countries, which mostly rely on the foster care system. Residents of the residential facilities report strict rules, child abuse, and bullying. [source] Usually people age out at 18, or even earlier at 15 if they choose not to attend high school. Requests to extend alternative care until an individual reaches 20 are usually denied. [source]

The economic outlook for individuals aging out of alternative care is not optimistic. “Once individuals lose their access to staying in an institution, combined with low wages for menial entry-level jobs, many young people cannot stay on the same job that the institution helps them find when they leave institutional care. If they leave that first job, they struggle to find another[...] Those who start working straight after graduating from junior high school and are forced to leave their institutional care facility may be at a particularly high risk of becoming homeless.” [source]

What does this mean for Jin? Since his parents died when he was in middle school, it could have taken place any time between the ages of 12 to 15. Jin was already working at 16 years old, which according to our information means he dropped out of school and no longer has government-provided accommodations. Depending on when during that middle school time window his parents died, he could have possibly not even entered into the alternative care system at all, entailing that he started to work right after their passing. Either way, Jin most likely quit school and started to work to support himself at 15 years old, forgoing high school and college, taking responsibility for his own shelter, food, bills, clothing, and so on. At an age when the UA kids are just beginning the best times of their lives, making friends, staying in the school’s dormitories, Jin was literally trying to survive on his own.

Criminality.

This is a bit harder to pin down, and there aren’t many English-language sources regarding criminal justice studies, and very little that thoroughly breaks down the process. For details that we might want to know about, such as arrests and convictions according to race, ethnicity, class, mental illness, etc., those are even more lacking (possibly also in part due to Japan’s low crime rate). I’ll do my best to sum up what I do have, and maybe someone can correct me on this. Anyways, starting from the basics:

The motorcycle accident that Jin was involved in, which injured another party, is a prosecutable crime punishable by up to seven years in prison or a fine of up to one million yen. [source] Just to cover all my bases, yes, at the time of the accident, Jin was indeed a minor under Japanese law (although within an age bracket where he theoretically could be assessed and/or tried as an adult), [source] [source] but we’re not sure if/to what degree that was taken into consideration. Either way, the outcome is that Jin likely ends up with a record, according to the officer (or possibly prosecutor) who’s speaking to him. From what I can make out, getting a record from a traffic accident with injury means he was charged and probably went through summary proceedings in the lowest court, [source] though I’m unsure how this whole process would work if his status as a juvenile was taken into account.

There are a few things to point out here:

Arrest and detention (which I’m assuming is the lead-up to that conversation with the officer) are notoriously lengthy and pretty rough. [source]

Prosecutors have significant discretion in what gets pushed through to see charges and what gets dropped. This is one of the reasons, possibly the main reason, for Japan’s 99% conviction rate—prosecutors usually only press charges in cases that can bring about conviction. They can even take into consideration someone’s age, character, circumstances, etc. when deciding whether to prosecute or not. [source]

During this process, when someone is hurt in an accident, there’s a pretty big deal made of apologizing and offering compensation to the harmed party. These actions are viewed favorably when it comes to case review and sentencing, while arguing over fault and general disagreeableness hurts the case. [source] [source]

(PS: The line “you’re to blame as well” makes sense in the Japanese legal system as a facet of comparative negligence.)

(PPS: Given the ongoing debates over juvenile justice—the likes of which inspired Battle Royale—I wonder if the rather harsh results of Jin’s first encounter with law enforcement are also meant to be read more deeply?) [source; cw for child murder in link]

At this point, we have the question of whether or not Jin’s possible record impacted his inability to “bounce back.” This was also pretty difficult to find information about, and the answer is... maybe. While criminal records are held by the police, and prospective employers cannot access them, this is usually sidestepped by asking applicants to provide information about their own criminal records on a CV template (whether or not people do, or can even legally lie about this, and whether or not they can choose not to answer without impacting their chances of getting hired is not information I was able to find). [source] A certain stigma towards convicted criminals does exist, despite the criminal justice system’s prioritization of reintegration over punishment, [source] though as for further information about whether a record impacts someone’s employability and quality of life doesn’t seem to have been studied. Real world Japan’s declining recidivism rate, though not declining as fast as first-time offenses, seems at least to suggest that even individuals with a record can successfully reintegrate into society, [source] hence the officer’s suggestion that Jin can “bounce back” is not totally bizarre, although it proves short-sighted.

These details illustrate the odds of what Jin is up against. They raise the question of why prosecution didn’t go differently, and they highlight the vulnerability of a parentless child up against the legal system. Jin, again, a 16-year-old (who also doesn’t appear to have legal counsel in the depicted panels), obviously argues his responsibility in the accident; furthermore, he’s unlikely to be able to fulfill the social graces required of a lenient case review. As a teenager who’s already working to support himself, without any family to lend a hand, he likely wouldn’t have been able to muster up the finances for compensation, medical expenses, property damage, etc. at a moment’s notice, and even in installments the payment probably would’ve been a strain. For example, the possible fine of one million yen is half the annual income of Japanese households which fell below the de-facto poverty line in 2008. [source] It seems plausible that his inability to see through the proper courtesies resulted in an unfavorable assessment, and a prosecution carried through to the end. We don’t know for sure how he was sentenced—judging by his return to work, it’s likely he didn’t do jail time—but even assuming a lenient sentence, this accident quickly catches up to him. With no one to fall back on, and no one to cut him some slack, a stumble quickly becomes a fall.

Employer-employee relations.

The relationship between an employer and employee is one rooted in a power dynamic, where one side controls the time, the wages, and often the health of the other. A job and its benefits are usually the deciding factors of someone’s quality of life, so employees will work overtime, work while ill, and suffer any number of abuses to keep their jobs. Overwork, and the resulting health problems from overwork are enough of a crisis in Japan they’ve been named karoshi—death from overwork. The effects range from general, stress-caused health problems, to heart failure and suicide; what gives rise to these conditions are a complex mix of work culture, company culture, and common hiring practices. Essentially, workers are encouraged to present a loyal face to their company, and because of the structure of the job market, changing jobs isn’t easy. [source] [source] These facets of work culture also contribute to power harassment, an issue that has received growing visibility in the past decade. In 2019, 37.5% of surveyed workers reported suffering power harassment, often from bosses, including receiving excessive demands, degrading treatment, invasions of privacy, and sometimes physical abuse. [source] [source]

This drastically imbalanced relationship only receives a few panels in Jin’s backstory, but that’s all it takes to make the power dynamic clear. Within three panels, Jin’s boss assaults him, berates him, and takes away what he knows is the only source of income for a working-class 16-year-old with no family. An accident that happened is equated to an act of disloyalty because the wrong person was injured, which reflected poorly on the company Jin was working for; however, a double-standard exists. While Jin’s loyalty to the company is expected, there’s no reciprocal expectation for the company to care for the wellbeing of its own workers, instead prioritizing its image and its bottom-line. Employees can be fired at their boss’s whim, leaving the terminated party without an income nor benefits, looking at breaking into a job market that is intolerant of repeat job-seekers—even more so if the individual is someone without a lengthy employment history and without a higher education. This short interaction highlights the precarity of financial stability, where a termination from one job on one man’s authority can leave someone—even a kid—without any way of coming back and achieving a steady living.

120 notes

·

View notes

Text

Shigaraki, the League and “Redemption”

(In this post: 1700 words about how much I feel like stories/meta in which Shigaraki is rescued or redeemed miss the entire point of Shigaraki.)

It's a big open question how much of Shigaraki's backstory was engineered by All For One. We're not even sure if AFO is the villain who killed Nana's husband, the event that kicked off the entire downward spiral of the Shimura family, much less what degree of involvement he had in Tenko's manifestation of Decay. There's a tremendous amount of well-thought-out, interesting meta and fic about what will happen when Shigaraki finds out the truth, whether he can or should still be redeemed as he currently stands, or how Tenko might have been saved from ever becoming Shigaraki to begin with. While I have read and enjoyed quite a lot of those theories and stories, I still find myself bothered by the prevalence of that line of thought because it ignores the fact that hero society stands condemned regardless.

Whether or not AFO gave Tenko the Decay quirk knowing what would happen, whether he found out about Tenko the night of the accident or never lost track of Kotaro from the very beginning, in truth, none of that matters to the narrative of the League on the whole. Nothing about Shigaraki's past has any bearing on the pasts of the other members. Trying to decide how to "save" Shigaraki avoids the fact that he is the leader of the League of Villains and their pain still stands regardless of their leader's history.

You cannot act as though saving Shigaraki--with All Might, Inko, Izuku, Eraserhead, anyone--would redeem hero society, because Shigaraki is not hero society's only victim. He's not even its most straightforward one! The condemnation he articulates of the world he lives in can't be addressed by him realizing he was manipulated by AFO all along or getting a good therapist in prison, because the world he lives in has failed a good many more people than just him.

Let's break it down.

The League Members

Twice fell through the cracks because of a lack of social support after his parents were killed in a villain attack. He was just a teenager back then--what arrangements were made about where he was going to live? If he was old enough that foster care/being placed in a group home wasn't a good option, did he instead have a stipend from the government? Where was the social worker who should have been overseeing his case? Where was his homeroom teacher when he dropped out of school? What support should have been available when he wound up homeless on the streets? Heroes stop villains and are rewarded both socially and monetarily for doing so, but the much more difficult and involved work of dealing with the fallout from those battles is clearly undervalued, badly so, in comparison. Hero society, which prioritizes glamorized reaction over everyday prevention, failed Bubaigawara Jin.

Spinner had the wrong kind of face. X-Men-style mutant discrimination left him isolated and alienated, shunned by the inhabitants of his backwater hometown because of his animal-type quirk. To say nothing about the threat of violent hate crimes implied by the existence of a KKK analogue! But it goes further than just the bigotry of his neighbors--Spinner's quirk was also unremarkable, meaning that, in a society that prizes flashy and offense-based quirks in its heroes, Spinner would have had few if any role models. Given how many heroes there are, it seems strange to consider that there isn't a single straightforward heteromorph for Spinner to idolize, but given how strongly he latches onto first Stain's warped ideals and later Shigaraki's nihilistic grandeur, Spinner is clearly a young man desperate for a role model--if a hero that fit the bill existed, he wouldn't be a villain today. So he's failed directly by his community for their bigotry and indirectly by society for the way it told him, in a thousand ways big and small, that Iguchi Shuuichi was not a person worth valuing.

Toga had the wrong kind of quirk. It's true that, more than anyone else in the League, she feels like a character who would always have struggled with mental stability, even with the best help imaginable--but she didn't get the best help imaginable, did she? She got parents who called her a freak, who berated a child barely into grade school about how unnatural and awful the desires she was born with were. She was put into a quirk counselling program that apparently only caused her to feel more detached from society. If Curious' characterization of quirk counselling is at all accurate, it seems to focus not on how to manage one's unusual or difficult quirk in healthy or productive ways, but rather on stressing what society considers "normal," on teaching its participants how to force themselves into that mold. Hero society wants people with different needs to learn how to function like "normal" people; it is unwilling to look for ways to accommodate such people on a societal level. Toga Himiko was failed by a society that demonized and othered her for a trait that she did not choose and innate desires that she never asked to experience.

And then, most prominently of all*, there's Dabi. We all know where the big Dabi backstory mystery is going, and his is the most open condemnation of hero society of them all. Dabi was raised on a heady cocktail, parental abuse mixed liberally with unquestioned acceptance of the fundamental importance of having a powerful quirk. Whatever else can be said of Endeavor's path to redemption, the old Enji is emblematic of everything wrong with hero society: the fundamental devaluing of those without power, the fervent strain to push oneself past one's limits over and over and over again, regardless of the consequences to your health or your relationships, the practice of raising children to glorify a dangerous profession that fights the symptoms of societal ills rather than the root causes. The ugly secrets hidden in the Todoroki house are the ugly secrets hidden within hero society's ideals, and because he embodies those ideals so thoroughly, of course Endeavor is lionized and well-paid by a society that never had to see Todoroki Touya's scars.

Mirror of Reality

All of these issues map to things in real life, and I don't only mean in a vague, universal sense--I mean they reflect on specific and observable Japanese problems. Read up on koseki family registries and consider how the dogged insistence on maintaining them impacted the Shimura family, tracked down by a monster. Look into societal bias against orphans and imagine how it shaped peoples' reactions to teenaged Jin and his alleged 'scary face.' Read up on how Japan approaches mental and physical disabilities, on what it regularly does to homeless camps, on what responses get trotted out when someone comes forward with a story about closeted abuse. The League embodies these issues in indirect, sometimes fantastical ways, but they're not what I would call subtle, either; there's a reason the generally poor, disenfranchised League members are contrasted with powerful, urbane criminals like All for One, callous manipulators like Overhaul, and entrenched pillars of society like Re-Destro.

Hero AUs are a fun thought exercise and all, but the League exists to call out and typify very real problems in heroic society and, by metaphorical extension, modern day Japanese society as well. Hero society studiously looks away from its victims. It doesn't want to see them and it thinks even trying to talk about them is disruptive and distasteful. There's no indication in-universe that there's even a movement trying to change this state of affairs. Certainly there are a great many things that could have changed to spare the BNHA world Shigaraki Tomura, but none of those quick, easy solutions would have saved Twice or Toga, Spinner or Dabi. The League of Villains is the punishment, the overdue reckoning that their country will have to face for its myriad failures--for letting its social safety nets grow ragged, for failing to stamp out quirk-based prejudice, for allowing its heroes to operate with so little oversight. For growing so complacent that not one person had the moral wherewithal to extend a hand to a bloodied, lost, suffering child.

Shigaraki, Past and Future

One of the most heartbreaking and yet awe-inspiring aspects of Shigaraki's characterization in his Deika City flashback is that he was thoughtful and compassionate enough to reach out to other kids who were being excluded and teased by the rest of his peer group. The League is foreshadowed for him even as a child, because even back then, he was a kid suffering repression and repudiation and so had empathy for others in similar straits. Young Tenko is the person who would have reached out a hand to the scary but obviously needy Tenko wandering the streets; Tomura, despite everything All For One did to him, still retains that core of fellow-feeling that invites other outcasts to play with him.

"Saving" Shigaraki without addressing the societal flaws that created the people gathered under his banner negates the entire point he and the League exist to raise. I think readers will be forced to confront those flaws alongside Midoriya and the rest of his classmates, who the story has made a point to keep mostly isolated and on a steady PLUS ULTRA diet of all the same rhetoric that leads to consequences like the League to begin with. I only wish more of the fandom--hero and villain fandom alike--was on the same page and writing their fic and meta accordingly.

Footnotes and Etc.

*The only characters in the League whose backstories we don't have much window on are Mr. Compress and Magne, both of whom are framed as seeing society as repressive. Magne openly says as much to Overhaul; Mr. C intimates it to the 1-A kids during the training camp attack. I'm inclined to hold off on commenting on them very thoroughly, though, because in neither case do we know exactly what drove them to crime in the first place. That's not a huge problem for Sako--if anyone on that team is into flamboyant villainy for the sheer joy of it, it's him--but I would definitely want to know more specifics about Magne's personal history before I correlate her experience as a trans woman with her portrayal as a violent, even lethal, criminal. That would get right into the problematic elements of portraying all these societal outcasts as villains, people who undoubtedly have a point, but have taken to terrorism to illustrate it. It's very possible that, for all that the League maps to real problems in Japan, we're still going to get a very mealy-mouthed, "But it's still wrong to lash out when you could protest nonviolently and work with your oppressors to seek a peaceful solution," moral from all this.

P.S. None of the above meta even takes into account the multiple non-League characters whose stories illustrate various failings of hero society--Gentle Criminal, Hawks, Shinsou, even Midoriya himself, as those endless reams of Villain!Deku AUs are ever hasty to expound upon. Vigilantes touches on the idea of "hero" and "villain" categorizations as being almost entirely political in their inception, as is also hinted at with historical characters like Destro. Seriously, the mountain of problems with hero culture just looms higher with every passing arc!

P.P.S. I absolutely do not mean to imply with this meta that Japan suffers uniquely from any of the problems discussed above. Other countries obviously have their own difficulties with homelessness, accessibility of care, victim blaming, and so forth. Horikoshi is writing in and about his own culture, though, and stripping Shigaraki of his villainous circumstances in the interest of making him happier and/or more palatable strikes me as being kind of culture-blind in a way that it’s very easy for Western fans to unthinkingly slip into. Just some food for thought.

#shigaraki tomura#tomura shigaraki#league of villains#boku no hero academia#bnha meta#my hero academia#my writing#bnha

162 notes

·

View notes

Note

Speakin of big sis Mags,, what are ur thoughts on her design being ‘transphobic’? I’ve seen some ppl say so and I honestly dunno how I feel myself?

So this is a complicated issue, but overall? Yeah I feel like her design is transphobic.

Did Hori intend to be transphobic, or was he even aware he was being so? Maybe, maybe not, I don’t know; but the fact of the matter is that, regardless of intent, Magne was designed to look like an overly masculine trans caricature.

While her character in general is great, and I feel like aside from being killed off she was treated comparatively well, it doesn’t change the fact that when I look at her it doesn’t read as ‘woman’ but ‘stereotype’. In fact I genuinely didn’t know she was a woman my first read-through until she died and the other characters made a point of it! And I know lots of other people had the same experience!

And that’s not because I don’t care about trans characters or that those of us who had trouble wanted to see her as a man (I myself am nonbinary and have lots of other gnc and trans friends, so trust me, I’d love to see more trans characters!) but rather that her design was so off that we couldn’t read her right.

From how I see it, the issues with her design are a lot of small ones piling up which would probably be fine if they were on here own.

She’s buff? So are lots of trans women! She has clear stubble? There’s no reason women should be forced to shave! She has really thick cartoony lips? Okay I can’t really think of an excuse for that one, maybe she’s still learning how to apply makeup?

But then you add in everything else: she’s violent, a villain, etc. Suddenly her strength comes off as brutish rather than powerful, her stubble is tied into how tough and masculine she is. When all the design characteristics come together it only amplifies how alien and off she looks.

@autistic-trans actually did an edit of her (i’ll rb this with the link, tumblr doesn’t like links in original posts rip) where, while still keeping her general traits, she looked a lot more realistic and just overall has a better design imo and it really shows how easily she could’ve NOT looked like a ‘trans women are actually buff men in makeup’ stereotype.It’s hard to see for some people because I feel maybe that if she kept a few of her more masculine physical traits with a different personality she’d be fine, or if she had the same personality but they tweaked her design ever so slightly she’d be fine, but the way everything comes together reads as a transphobic caricature which is something she can be so much more than! She wants to find a place to belong! To become a better version of herself alongside her team! To support her villain family!

So I kind of rambled a bit, but yeah. Her design could still be worse but I’m not gonna deny that Magne’s character design really rubs me the wrong way and comes off as transphobic. Given how great she could be if she got a little more care from the creators + a bit more screentime, that’s really a shame.

Magne is great and deserved better.

64 notes

·

View notes