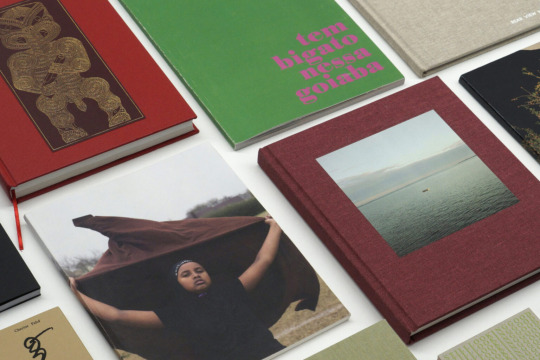

#in a world of digital there's something really different about holding a tangible physical object in your hands

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

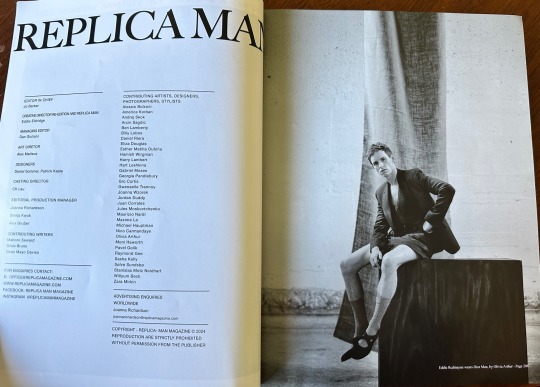

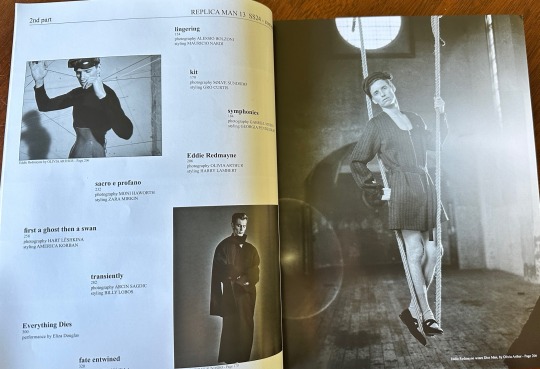

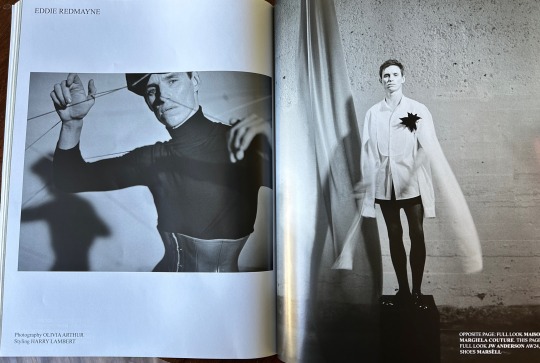

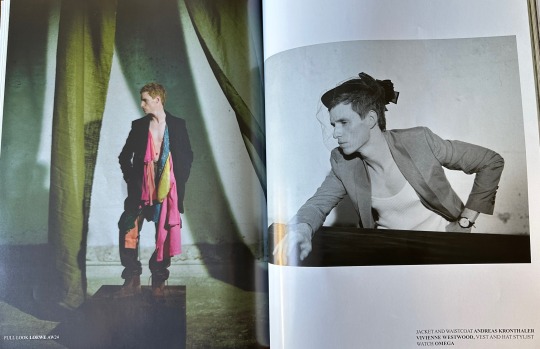

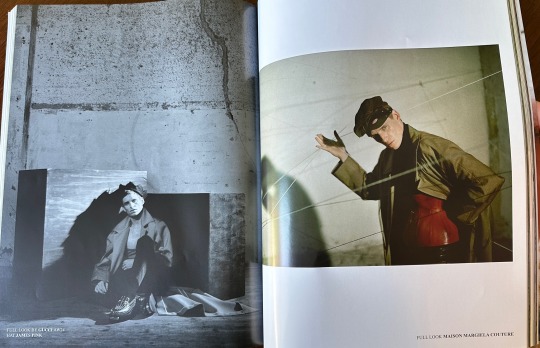

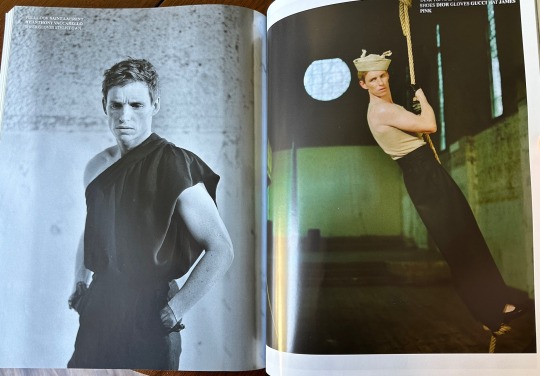

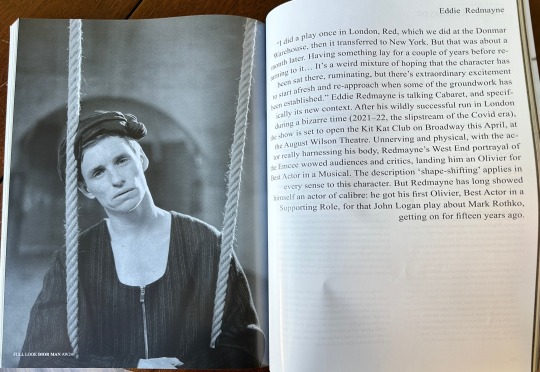

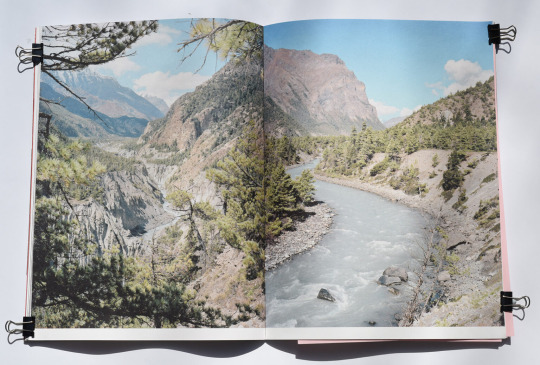

The insanity continues. They kept releasing more photos from this editorial in Replica Man. I said to myself, "Self, you do not need a magazine just because Eddie Redmayne is in it. No matter HOW much gender he's serving."

And then they showed us the corset pics, and his slutty little waist was the final straw.

So yeah, I ordered this from the UK since they don't sell it in the US. It will go on the shelf next to "Denim People", a knitting pattern book by Rowan Knits, featuring Eddie modeling knitwear circa 2003.

#i am doing a normal very successfully#there are a few more photos in here but you've already seen them posted#in a world of digital there's something really different about holding a tangible physical object in your hands#eddie redmayne#cabaret 2024#gender

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

HEGEL’S TROWEL: working on the thing

Making changes everything. Ivan Illich, Tools for Conviviality

Soul is extra-scientific, outside of science, we will allow no scientific disproof of it. Maulana Karenga, Practice: Documents of Contemporary Art

Locked down by government guidelines designed to increase social distancing, the gap between oneself and the other, a space that can stop cross infection between us all, meant spending time watching the television. The daily BBC update reported how many more bodies have been, are still being, destroyed or attacked from the deadly Covid-19 virus. It might not be surprising then with so much biological and existential demolition on the go that I found myself watching TV programming to do with restoration and making things: Salvage Hunters, Escape to the Chateau DIY, Secrets of the Museum, The Restoration of Notre- Dame Cathedral. Kirsty Alsop reckons these days we should Keep Crafting and Carry on; making things as a form of therapy. The Repair Shop is a phenomena with craft experts restoring material stuff to how it was. Grayson Perry promoted art, and artisan making – he is a potter - as a great healer: ‘we are all wounded’ he said on channel four. Before the outbreak of this new threat to life I was working up this small general piece about the transformational potential of creative activity, in the main, making.

Lisa Tarbuck, was talking on radio 2. She’s a media celebrity and a fan of making things. Super mentioning a piece of weaving or needlework she’d completed that day, she told her Saturday night audience: ‘I just couldn’t stop bloomin’ looking at it…know wot I mean…? An old friend told me recently that I just had to get hold of a copy of Mathew Crawford’s The Case for Working with Your Hands (2011). He, the old friend, was the studio furniture designer-maker when I worked with him at Detail London; a young furniture makers. Together, we made bespoke furniture (for a beautiful stylish wealthy cool consuming clientele). Nowadays he works in academia, writing and lecturing to students about craft and making. His research has interrogated how human well-being is affected by undertaking craft activities, particular recreational making done by amateur practitioners. Crawford writes about well-being, too. The subtitle of his study is: or why office work is bad for us and fixing things feels good. In a recent email exchange the furniture designer turned academic communicated that he looked back with fondness to his making days. Perhaps with ‘rose-tinted glasses’ he qualified.

There is a growing group of western intellectuals who today theorise and promote the idea that there is a definite connection between the processes undertaken when crafting things from raw materials and human well-being. Often slow and protracted, acts of physical making are, they generally posit, a valid source and resource to increase self-esteem. Existential events such as technically planning how to make something from scratch, the selecting of appropriate materials, development and deployment of hand skills, constructing structures to a set standard, finishing worked-on material, just being in a practical workshop in extended time and space, are inter alia physically, intellectually, emotionally good for human life. Teaching craft skills in adult education and community workshop settings I have witnessed diverse learner makers achieve remarkable personal satisfaction, and that allied well-being a craft cognoscenti rightly identify, in going through the technical and material processes when constructing any crafted object. Contra this supra ideal of process, quotidian workshop life reveals that, in reality, it is not only the extended making of the final object that is beneficent to the maker of this newly-present thing – the temporal spatial physical crafting and grafting - but the now-made self-styled object- the present thing in itself the maker has made.

At the currently closed-for-restoration Silk Mill (soon to be transformed/remade as The Museum of Making) interested visitors come to Derby for a look around the modern workshop housed in the ‘world’s-first-factory’. Generally, but not always, these people are museum professionals, culture workers, creative artists or social activists. Nearly all are interested in delivering well-being because it matters. I like talking to these folks, often desk-bound and definitively (unavoidably?) over-digitalised in their daily office lives, they take a genuine interest in the practical making a workshop allows – the working we do with our hands - activities they see as critical to human holistic well-being. Sometime ago our executive director at Derby Museums was in the workshop standing by our CNC, talking with me. Next to Tony stood one of the inquisitive visitors; an interested (and interesting to me) culture-industry professional. Inevitably, the conversation made its way to mentions of well-being. I told them both how I see people who often do symbolically distinguished, but atomised or abstract, work -- practices with often unquantifiable or subjective outcomes (the negative work Crawford describes) -- come to a fresh and solider understanding of themselves after constructing a materially tangible piece of furniture out of plywood or turning out a curvy bowl from a rough brute blank of oak. Stood next to the idled CNC I remember saying something like this:

“In my working life I come across a lot of people who do highly complex engineering, but in a rather abstract or theoretical way, or others who live in a digital bubble I call ‘computer world’, modelling AutoCAD perfection but never getting to actually see or touch any material outcomes or be involved in making something from start to finish by their own hands… But when people make something here in the workshop they objectify themselves…….as they say “no one has ever taken a picture of the unconscious…or seen a picture of the self ”.

There followed a sort of embarrassed silence. Then inscrutable nods and smiles from the Executive Director and his guest. Then a “well thanks for that Steve….” -- as they left the workshop.

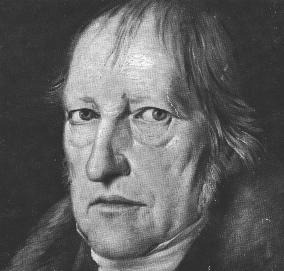

Specifically, a proud plagiarist, I had, of course, synthesized the ideas of literary critic Terry Eagleton and Arts and Craft sculptor Eric Gill. Generally speaking, I had just paraphrased a few ideas of the well-known German philosopher GWF Hegel (1770-1831) -- ideas lifted from the undecipherable, but well known, Phenomenology of Mind (1807).

Well, to be more honest, I was paraphrasing Alexandre Kojève’s partially more decipherable Introduction to the Reading of Hegel. Compiled from Kojève’s lecture notes, and first published in 1969, the cult text explains Hegel’s theory of the dialectical (constant changing) progress of human history, in particular his well-known concept of the ‘Master and Slave’ conflict – the transformative phylogenetic and ontogenetic dialectic. For me the key passage in Introduction is how the text unmakes and then reconstitutes Hegel’s brutal concept of The Thing – raw given objective nature as unshaped material object – and how non-human Things (slaves/workers/makers) become Human. i.e. transform their selfhood from a raw physiological primordial brute unthinking thing by working on another thing (raw brute unshaped material reality – wood, stone, metal, wool, cotton, clay) and making it or, a key word, transforming it (as of themselves) - into something it wasn’t before, in its un-worked material given existence in the world, for another: The Master.

This is the actual Hegelian (Kojèvian) paragraph that refers to the experience of the creating maker- slave who makes for, and in place of, the consumer master:

‘The slave can work for the Master – that is, for another other than himself…he does not destroy the thing as it is given. He postpones the destruction of the thing by first trans-forming it through work; he prepares it for consumption-that is to say, he “forms” it. In his work, he trans-forms things and trans-forms himself at the same time: he forms things and the World by transforming himself, by educating himself; and he educates himself, he forms himself, by transforming things and the World. Thus, the negative-or-negating relation to the object becomes a form of this object and gains permanence, precisely because, for the worker, the object has autonomy. At the same time, the negative-or-negating middle-term—i.e., the forming activity [of work] – is the isolated particularity or the pure Being-for-itself of the Consciousness. And this Being-for-itself, through work, now passes into what is outside of the Consciousness, into the element of permanence. The working Consciousness thereby attains a contemplation of autonomous given-being such that it contemplates itself in it. [The product of work is the worker’s production. It is the realisation of his project, of his idea; hence, it is he that is realised in and by this product, and consequently he contemplates himself when he contemplates it. Now, this artificial product is at the same time just as “autonomous,” just as objective, just as independent of man, as is the natural thing. Therefore, it is by work, and only by work, that man realises himself objectively as man. Only after producing an artificial object is man himself really and objectively more than and different from a natural being; and only in this real and objective product does he become truly conscious of his subjective human reality. Therefore, it is only by work that man is a supernatural being that is conscious of its reality; by working, he is “incarnated” Spirit, he is historical “World”, he is “objectivised” History.’

Kojève concludes in the Intro that the dead German idealist philosopher (Hegel) ‘may well know much more than we do about things we need to know’.

Interestingly, a former US academic/intellectual, Crawford (he worked in a Washington ‘think tank’ before quitting to run a motorcycle repair shop) uses the same quote in his book The Case For Working With Your Hands – but misleadingly attributes the quote to the Kojève. Folksy Crawford expresses Hegel’s idea in a more homespun pragmatic manner, as is the way of practical American philosophy: ‘The satisfaction of manifesting oneself concretely in the world through manual competence has been known to make a man quiet and easy…he is proud of what has been made’

Crawford writes about a kind of ‘self-disclosing’ latent in creativity, work and making.Concurring with Crawford and Hegel the sociologist Richard Sennet in his study The Craftsman, rites about ‘the warm values of craft and creativity’ and a ‘zesty freedom crucial to well-being of society’.

_____________________________________

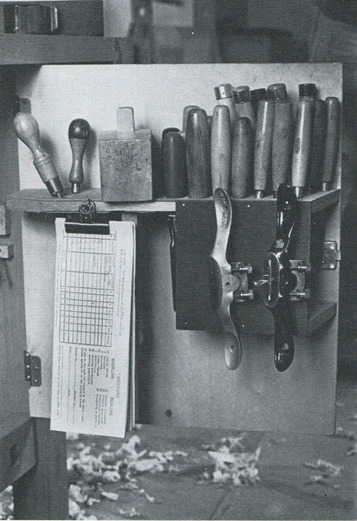

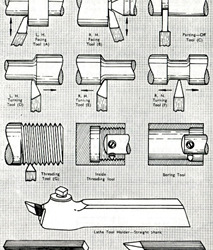

I worked for a time in a comprehensive school. The head of Design and Technology – a former skilled industrial toolmaker – had had the foresight not to sell off the capstan lathes, milling machines, welding kit, old-school woodwork benches and traditional hand tools bought and installed in the 1970s.

Painted out in dull lemon yellow, orthodox (vintage) wood-machinery apple green, the Design &Technology workshops looked like the past and so still played their part in 21st century life. You could smell old machine oil in the cold metal machines, bashed-up blue vices fitted to weathered beech workstations exuded a residual making aura. When the lathes were set running, rasping files shaped steel, sharp planes flattened pine, the space sounded like a real live workshop in the (ontogenetic) now, yet echoing the making culture of a phylogenetic past. In America, Crawford tells us that technical making and design is simply called ‘shop class’, or more accurately was called shop class because he bleakly observes, akin to the collapse of technical skills education in Britain, since the early 90s educational institutions have instituted a ‘big push’ to close shop class to open up digital and computer literacy. Any revival of shop class today is hindered for Crawford by the lack of skilled people competent to revive technical crafts and making in general.

Frustrated by the British school drift to digital D&T practices, a virtual curriculum (there is now virtual welding), and driven on by a shared ‘it wasn’t all computers in our day’ narcissistic nostalgia (manifested in everyday miserableness), me and the old toolmaker got our heads together and came up with project which harked back to the days of secondary-modern craft lessons in wood and metalwork; the saved machines made the scene believable.

It was only a small pot-planting trowel. It was made out of aluminium and wood. From tip to tip 200mm long. It had a curved blade and the cranked arm was cold-riveted to the blade in a traditional blacksmithing style; the students used ballpein hammers clanging metal on the workshop’s under-loved anvil. On the once-busy but no-longer-silent lathes we put a sharp point on the 6mm round bar that made the stem from handle to blade helping drive it into the softer wooden trowel handle. The serpentine bends were created on a small Groz metal folder designed for DIY artisan metalworkers. The hardwood handle was shaped with a selection of rough round and flat cutting rasps, before being sanded, with care, by glass-paper. The blade was formed with aero-industry tin snips before being worked into a symmetrical curve with metal files. To work the flat sheet aluminium into the required radius of the blade it was fed several passes through a small jewellery rolling machine – sort of a washing mangle meets pasta machine. The trowel looked impressive when made. Three hundred students made one. The test of success is always if young makers want to take what they make home to show to someone who they care cares; most did. They had worked on the thing, objectified themselves, could contemplate themselves in itself, the small trowel, a trowel designed to be used, a tool to work on the thing, transforming nature as soil to wit.

The now fired up ex-toolmaker pointed out to me that, before we could roll out the trowel project to the students, the NQTs (Newly Qualified Teachers) in the D&T department – the electronic, digital, laser engraving, 3D printing makers – and ESWs, (Educational Support Workers) who would assist students, had to be quickly trained up in the basic craft and hand skills required to create, then teach, the trowel. They would need teaching the basic historical making techniques for working on the thing.

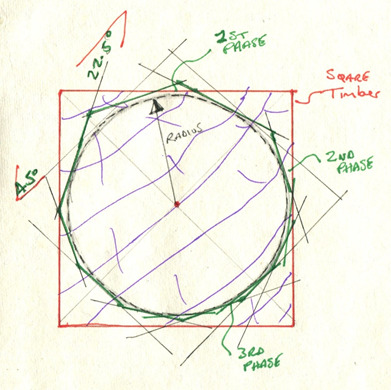

We arranged an ‘after-school’ instruction session in the workshop classroom. Everyone arrived looking harassed with a mug of tea or coffee/mug of hot water; offered the usual banter; male teachers removed ties; everyone put on an apron. Each participant got a set of stock blanks: a length of aluminium bar, 150mm x 6mm ø; a rectangle of sheet aluminium, 1mm x 75mm x 120mm; a section of hardwood (beech, oak, ash, reclaimed teak or mahogany), 100mm x 25mm▫. The first task was to make a two-dimensional template – using 5mm graph card folded in half along a continuous grid line – to mark out the tapering and curved profile of the trowel’s blade. Sketching freehand they used the graph-paper squares for visual guidance. The pencilled line was cut with scissors and the pattern unfolded to reveal a symmetrical, if rough, outline. The next step was to show the trowel-makers how to transfer the profile, geometrically square, onto the shiny cropped aluminium by using a scribed (accurately-marked) centre line to align the centrefold of the paper along, thus ensuring the blade sat true, i.e. at 90° to the square back edge.

A metal scriber was then used to carefully score a visible line around the flimsy paper template into the soft aluminium. The workshop was quiet except for the soft ringing sound of metal on wood benchtop as, in deep concentration, teaching-staff students guided the hardened and sharpened steel marking tool around the curved card onto the aluminium.

(Still you could hear some light jokey banter, but of a kind, collaborative, encouraging type of joshing – ‘phatic’ communication, some dead continental philosopher of language would say.)

Aluminium can be cut easily - as card with scissors - when using inexpensive aero-industry shearing snips. Commonly used in hand tin-smith work and light commercial bespoke production these tools are designed to cut straight or with a left or right hand bias. (They are colour coded red, green and yellow and a good workshop needs the full set – an additional long-nosed straight-cutting pair is a great help for occasional extended profile cutting or internal corners.) I demonstrated how to cut the aluminium in short snips, neatly following the scribed line, shearing the material slowly and deftly the snips making the waste (swarf) curl upwards, away from the desired external blade line.

It was pointed out to the teacher-students that - novice maker or proficient craftsman - it is generally best practice when cutting stock materials to work ‘outside the line’ leaving a small margin of material for cleaning up post-cutting. Dead flat with fine teeth, hard because made from steel, metal-working files were used to remove the extraneous rough cut metal to the scribed line, scored into the aluminium, demarking the required final recognisable trowel-blade profile. Filing produces sharp burrs on metal which, in this instance, were removed with industrial emery paper. The blade smooth and symmetrical was now ready for the students to roll.

Metal rolling is the same process for a fine silver ring as a thick-walled boiler rolled out from, as it happens, 25 mm boiler plate. Basically, thin or thick factory-milled metal plate is passed through two calibrated parallel rollers which are adjusted to the required gauge of the material to be rolled. Sprung under high tension the front bars force the metal sheet towards a single back roller which is set higher than the underside of the passing steel or, in our case, aluminium. The metal is malleable and -- forced to climb over the higher spinning back roller -- begins to take on the required radius of the part required. This might be a shallow curve as the trowel needs, or a full circle, as in a delicate silver ring or a high pressure vessel such as a boiler whereby the seam is soldered or welded together and ground back. We were using a small jewellery-maker’s bench roller - no more than 300 mm in width - but the radius-forming mechanical principal remains the same.

Operating a bench metal roller is, as I sort of said before, a bit like passing dough through a pasta machine. But instead of making the metal thinner per pass – which, as is well known, is how the metal plate was produced in the forging mill in the first phase of ‘thing working’ - the radius is increased; the careful gradual adjustment – the increased un-alignment of the roller - in small increments forms the aluminium into the practical, and aesthetically pleasant crescent wanted. Students checked the curvature against a small accurate plywood template. They had to make three to four adjustments.

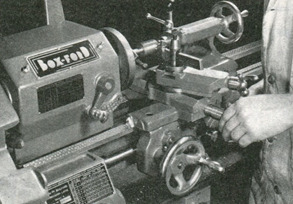

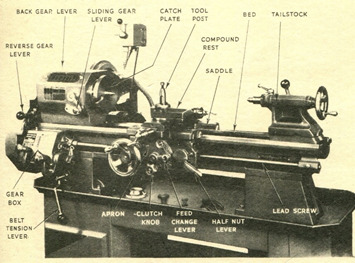

Before forming the 6mm bar into the distinctive kinked component joining the wooden handle to the blade of the trowel, it was necessary at this stage to turn a sharp point on the aluminium that would allow the bar to be driven into the end grain of the timber. The stock piece of rod was placed in a three-jaw chuck screwed onto the turning stock of one of the neglected Colchester lathes in the workshop, and the traverse tool slider bed set at 5°; a shallow machining angle, but correct for this operation. Each operative was informed of which was the correct tool to use for this operation – left hand cutting tool - and shown how to clamp and set the tool in the lathe tool holder to the dead-centre of the lathe and therefore the dead centre of the round stock material to achieve the optimum cutting angle and efficient waste removal. As a matter of maker education, head-stock turning-speed settings – coded in colour on the foundry-cast body of the Colchester – were demonstrated to, but set by, the learner turners.

The trowel project was designed/contrived to include several processes and employ a variety of tools and typical metalworking kit to introduce youngsters to some fundamental craft techniques and experience bench fitting, sheet metal working, capstan turning.

To secure the cranked arm to the blade two aluminium rivets were to be inserted through the stem and trowel blade and flattened into a pre-drilled countersunk hole so creating a secure fixing. But, the bar was round in section, so that only a small section of the stem would be in contact with the flattish blade. To achieve a better joint it was imperative, then, to flatten out the round bar by heating the end of the stem and bashing it while it was still plastic with heat, hammering it carefully into shape with a heavy ballpein hammer on the arm of a traditional forge anvil; a neat steer of the making process into the lost-world of blacksmithing.

(Hegel liked to walk in his home town of Heidelberg, and perhaps it was the sight of the town blacksmith toiling over a hot forge, hammering and twisting hot raw iron into shape, making some decorative gates for the local lordship, that inspired his ideas about masters and servants and the transformative effects of working on the thing? Today, most of us have seen similar images on TV: neo-blacksmiths heating metal in a forge until it glows orange-red with heat from the coals before working it to form, with that romantic ringing of hammer and anvil, before plunging the work into cold steaming water.)

The problem with aluminium is that, non-ferrous, it retains its silver-grey colour when heated, and, to boot, we didn’t have access to a traditional forge, but the old toolmaker had the answer. He produced a plumber’s Gaz blowtorch, “I nicked ‘im from construction cupboard”, and some Fairy Liquid. Go on then, he said, smirking, what’s the Washing-up liquid for? I put my bottom lip out, shrugged with a laugh, and said I had no idea. “Ally don’t glow”. “Oh…I see” I said. “Detergent turns black when metal’s ‘ot enuff…then you can work it on anvil…simple” he grabbed the collar of his white smock with both hands and gave them a tug, before firing up the blowtorch. I passed this tip on to the NQTs and ESWs before they flattened their trowel stems.

In old-school black and white ink, a technical drawing indicated to the trowel-makers where on the straight length of aluminium bar marks needed to be made to indicate where the handle section should be placed in the trapping tongue - moved by a simple rack gear - of the Groz bender. The top of the tooling was also marked ‘clock –face’ style to show how far the tommy bar handle should be moved (from 12 to 4 say) and so work the soft rod into the flattened S shaped crank required of the finished component. The makers were having fun using the different kit, especially, the Groz, - they became absorbed in the basic but fundamental metal-forming processes and traditional manufacturing techniques introduced to them - but had to fully concentrate on ensuring that the two bends were executed in the same plane of orientation to avoid twisting the stalk of the cranked trowel stem or out of line with the flattened riveted section.

[ The Groz metal bender is itself a thing – converted and worked and cast from material nature (mined raw iron ore -- made into steel and machine processed) - made by things – humanised thing makers (engineers) - to make small springs, fixing clips and rings - things for other things; tools, machine parts, which in their bending, twisting and forming offer a thing maker chance to transcend its objective thingness in working on this metal material stuff, and objectify its subjective self through the final thing made, which in the case of machinery and tools may make other things and so on. Such as clips on a motorcycle in for repair or customisation in Crawford’s American shop. ]

The cranked bar was then set in a machine vice on the pillar drill, and a 3mm hole was drilled to take the rivet stalk and slightly larger countersunk hole ( top side) into which the 3mm aluminium rivet stalk would, using a hammer and anvil, be flattened. The wider domed mushroom head of the round rivet traps the thin blade between the stem and blade. To avoid flattening the curvature of the rivet head a purpose-designed hollowed out steel tool -- an exact concaved inverse radius of the convex pip of the rivet fastening -- was used by the participants to protect it when hammering the soft aluminium into the bored out section on the reverse side. This was then also filed flat and finished smooth with emery paper. With this fine fettling the metal-working processes had been completed. Components had all been successfully marked out, cut, shaped, rolled and bent, riveted and finally filed into a recognisable small potting trowel. Everyone in the class (shop) looked dead pleased to have transformed the shapeless bits and pieces of metal into a tool that could be used; but they still had to make the handle out of wood.

In a small box were a selection of pre-cut handle blanks ready to be matched to the still-shiny trowel parts. There were short 25mm square sections of beech, ash, mahogany, maple, oak and reclaimed pine – all unwanted found offcuts lying around waiting to be made into something useful but beautiful. I explained how that the first task was to set out the curvature required of a rounded handle on the end sections. For example, a circle is created from a geometrically symmetrical combination of hexagonal flats filed at 45°, then refined further with 22.5° tangents which, if the section diameter was large enough, can be taken closer to a perfect mathematically round profile with 11.25° flats and so on, i.e. angles are halved until a finite circle is produced. People smile when I say a circle is made of infinite flats, but, in a way, it is.

The second operation was to drill a hole down the centre of the stock timber with a 6mm drill bit. The wood was set square in a vice on a pillar drill and a hole bored down its core to accommodate the aluminium.

To be honest with you, most of the teachers and ESWs went their own way, freestyling, shaping the wooden parts, integrating underside curves with small finger-shaped hand grips. After the tight discipline of the metal techniques, finishing of the handles with spoke-shaves and rough-sharp rasps into vernacular crafted forms offered the makers a sort of soft therapeutic warm-down. The workshop took on a quieter woody – less hard metallic - aspect; a fresh atmospheric with the room infused by the aroma of the freshly worked old dead growing thing: the trees.

The organic-looking handles were finished with glass paper, students instructed in how to work from the roughing grades, 60 grit through to 100 grit, fining down to 240 flour paper. The job was finished by oiling the timber with Danish oil which brings out the light and shade and twisting lines of wood grain; sealing the material from moisture, and ultimate rotting. The final operation was to cement the riveted trowel section into the completed handle with a small dob of epoxy resin adhesive and stand back and admire; take in what had been achieved in a short after-school making session.

We stood around chatting. People said they’d loved making something. One said it had de-stressed him. Another couldn’t wait to take it home to show others. Some said nothing, but admired their handiwork. A few critiqued their own trowel, then complimented other’s workmanship. Phone cameras came into play. After we all packed away and tidied the workshop up ready for the next D&T school day – vacuum forming plastic bugs for students to stick googly eyes onto – everybody rushed out of the door to get home for tea. But one person hung back. She said to me ‘I’ve really enjoyed making this. Being in the workshop was just what I needed’. Good, I thought, and said ‘I’m glad’. She said ‘No more than that Steve…I needed this’. She paused. Looked a bit upset. She told me she’d had a horrible day. Awful and terrible because she was in personal conflict with a co-worker. The situation was unbearable. The emotional pain almost tortuous, nearly breaking her, she reckoned. So upset, she just wanted to go home; get out of the place. She’d forced herself to stay on. But holding up the trowel said ‘I’m so glad I stuck it out – I’m dead proud of making this’. She waved about the trowel as if digging the earth. It might only be a small thing, she admitted, but the trowel had proved something, her soul was restored, she had something to use and show for herself. The Trowel project will feature in Museum of Making workshop programming 2021

_____________________________________________

1 note

·

View note

Text

Invisible Impact

How perception is affected by the interconnectedness of aesthetics, mediums, and ideologies.

Written by Ramirez De Leon

“In an electric information environment, minority groups can no longer be contained — ignored. Too many people know too much about each other. Our new environment compels commitment and participation. We have become irrevocably involved with, and responsible for, each other.”

— Marshall McLuhan

Note: This work is not a critique or analysis of politics. It is merely a look at different philosophical and artistic perspectives as they influence the perception of the self within culture. First, we take a look at the impact of mediums, next ideology and commodities, and finally habitus.

I.) MEDIUMS

“What you print is nothing compared to the effect of the printed word. The printed words sets up a paradigm, a structure of awareness which affects everybody in very, very drastic ways, and it doesn’t very much matter what you print as long as you go on in that form of activity.”

- MM

As an artist, as someone who walks in the unknown uncertainty of creativity, I understand that the work we do as artists has an impact beyond immediate description.

A work’s “non-descriptiveness” allows it to be felt intensely regardless of language, culture, or identification. It is an affect that is grossly underrated and under-discussed. This subject matter is rarely discussed or expressed because people are trained to think in a gross materialistic way at a very young age. Materialistic indoctrination forces one to see artwork (or creative projects) as merely products. (or as means to an end).

“Creativity is uncertain. To be creative you must get into the indeterminacy of your own structure, your own knowledge, your own future , one of the large control systems that you have in your head and in your body says… that for survival of the individual and survival of the race, these are the railroad tracks you have to travel. That may or may not be true. And we know that it’s true within certain limits, but these limits probably can be enlarged. We also know that in the software of your own brain, the province of your own mind, this is not really that necessary. We have sufficient computing capacity within our own structures, our own brains, so that we can turn over to a very small part of that computing capacity for the necessary programs for survival…you can have alternative futures, you can have alternative programming you don’t have to keep going round and round survival tape loop…”

- John C. Lilly

Oppression is not merely in the physical, economic, or material sense. Nor is it merely large entity versus the small entity. Oppression is often an ideologically materialistic , passive means of asserting dominance over the essence of creativity, true expression and new ideas. Oppression in its most basic form can be a concocted collection of institutionalized assumptions that repress possibilities of creative thinking.

Furthermore, we cannot underestimate the power of mediums themselves. To ignore the power of the medium or to maintain our ignorance to the medium is to refuse excellence in our art, thinking, and profession. This lack of awareness of the medium may be a direct hindrance to happiness and enjoyment in life.

For those not in a constant state of fight for survival, what must be obtained is the consciousness of the evolving medium that is the communication of our digital selves (avatars).

And so the title [The Medium is the Massage] is intended to draw attention to the fact that a medium is not something neutral — it does something to people. It takes hold of them. It rubs them off, it massages them and bumps them around, chiropractically, as it were…

— MM

Mediums: the intervening substance through which impressions are conveyed to the senses (or that force that acts on objects at a distance.) are indeed very powerful. Ultimately, our experience in the material sense is exactly that, a stimulating encounter with that information derived from the senses (engagement with the unseen and seen, where material objects have the leading role). This means that the objects we encounter in themselves are created works, and therefore can have just as much impact (or more) than those objects that we call and designate as “art”(those objects which we intend to be treated, viewed, and considered to be “works of art”).

We are not at odds with ideas solely, or primarily (as many might suggest). We are at odds with objects and their suggested implications. We are at odds with the roles that we have assumed and the mediums which carry the polarizing and sometimes offensive ideas.

The medium is allowed to carry a concept or an idea and present it to the eye or ear, and in many cases, when the viewer gives those ideas credence, the medium , as well as it’s objective is able to stealthy infiltrate the attitudes, moods and modes of the now subdued perceiver.

“It is a matter of the greatest urgency that our educational institutions realize that we now have civil war among these environments created by media other than the printed word.”

— MM

II.) IDEOLOGY and COMMODITIES

“Ideology is not simply imposed on ourselves. Ideology is our spontaneous relation to our social world, how we perceive each meaning and so on and so on. We, in a way, enjoy our ideology. To step out of ideology, it hurts. It’s a painful experience. You must force yourself to do it.”

- Slavoj Zizek , [Perverts Guide to Ideology, 2012]

If objects as mediums have a profound and sometimes subliminal impact on our perception, then we must also look at commodities of industry. Commodities help establish class and class systems.

Certain objects are often appreciated by those families of certain classes that train their young to appreciate those very objects as well as their cultural significance. These activities and objects, of course, are often guarded by characteristics of economic inaccessibility.

The nature of the fine arts, more specifically oil painting, collectively, helped reinforced a sense ownership, commodity fetishism, and high classism.

“From 1500 to 1900 the visual arts of Europe were dominated by the oil painting, the easel picture, this kind of painting had never been used anywhere else in the world before. The tradition of oil painting was made up of hundreds of thousands of unremarkable works hung all over the walls of galleries and private houses rather in the same way as the reserve collection is still hung in the National Gallery …European oil painting unlike the art of other civilizations and periods placed a unique emphasis on the tangibility. The texture, the weight. the graspability of what was depicted. What was real as what you could put your hands on…. the beginning of the tradition of oil painting, the emphasis on the real being solid was part of a scientific attitude but the emphasis on the real being solid became equally closely connected with a sense of ownership.”

— John Berger, Ways of Seeing

Imagine two individuals from very different classes. One is highly rich and the other very poor. It is easy to imagine that in some oil paintings of the 1600s, those wealthier individuals will likely have a different relationship and attitude towards those paintings (especially if they see themselves reflected in those very works).

Many argue for equal representation of minority groups in mass and popular media. If one sees themselves in the artwork around them, then their perception of the world will change.

It is my argument that not only “fine art” or oil paintings in todays era are a reflection and establishment of classes and class structures, but rather, almost any commodity, product, or medium can have a very similar affect. All of these subjects, and how we interact with them, are reflections of class structures and belief systems.

Objects, in a way, force individuals to consider their options and reality in a very specific and sometimes narrow way. It can greatly limit what one perceives to be possible for them within a society. These assumptions further perpetuated by objects and mediums can systematically eliminate the thought of new and positive possibilities that otherwise gain access to the mental faculties of the higher classes.

This can be simply understood as the impact of design on the psyche. Those who appreciate and know that design can affect our reality and our relationship with it know how important aesthetic and utility can be.

The late John Berger, art critic well known for his work entitled “Ways Of Seeing” explains that previously oil painting would show a class of individuals as they were, with their materials and land and lifestyle. These oil paintings reaffirmed their positions in their reality. And on the contrary, our modern era of publicity and advertisement displays a fantasy of who we are not, but wish to one day be. For the modern era, it is not simply about the product but the fantasy and attitude that the product will grant us.

“It was already Marx who long ago emphasized that a commodity is never just a simple object that we buy and consume. A commodity is an object full of theological, even metaphysical, niceties. Its presence always reflects an invisible transcendence. And the classical publicity for Coke quite openly refers to this absent, invisible, quality. Coke is the “real thing”.

— Zizek

A commodity appears at first sight an extremely obvious, trivial thing. But its analysis brings out that it is a very strange thing, abounding in metaphysical subtleties and theological niceties….. as soon as it emerges as a commodity, it changes into a thing which transcends sensuousness.

— Karl Marx, Capital (1867)

III. HABITUS

In sociology, Habitus comprises socially ingrained habits, skills and dispositions. It is the way that individuals perceive the social world around them and react to it. These dispositions are usually shared by people with similar backgrounds (such as social class, religion, nationality, ethnicity, education and profession).

“Habitus also extends to our “taste” for cultural objects such as art, food, and clothing.

In one of his major works, Distinction, [Pierre] Bourdieu links French citizens’ tastes in art to their social class positions, forcefully arguing that aesthetic sensibilities are shaped by the culturally ingrained habitus.

Upper-class individuals, for example, have a taste for fine art because they have been exposed to and trained to appreciate it since a very early age, while working-class individuals have generally not had access to “high art” and thus haven’t cultivated the habitus appropriate to the fine art “game.”

The thing about the habitus, Bourdieu often noted, was that it was so ingrained that people often mistook the feel for the game as natural instead of culturally developed. This often leads to justifying social inequality, because it is (mistakenly) believed that some people are naturally disposed to the finer things in life while others are not.

— Social Theory Re-Wired

“The meaning of a painting no longer resides on it’s unique painted surface, which it is only possible to see in one place at one time. It’s meaning ,or a large part of it has become transmittable. It comes to you, this meaning, like the news of an event. It has become information of a sort.” — Justin Berger

In conclusion, I believe that once we acknowledge the affect commodities have on the world beyond their implied and immediately described purpose, if we acknowledge their assumed magical qualities, we will understand that mediums and commodities create a very particular context by which we view ourselves within the world.

These objects quite literally create the structural boundaries in which our imaginations dance. These objects influence the distance in which our imagination travels as well as the means of such travel. It is only until we discuss and acknowledge these invisible qualities that we may consider our own rational alternatives to these prescribed perspectives.

If we are to acknowledge at all the boundaries and limitations that are put on artists and subjects of class, if we have any desire to have a say in how our work as artists is perceived and activated, if we want to change any of these conditions in which we live, if we desire to acquire a taste beyond the commonly associated, false identities; we must begin to learn about these materials, their invisible qualities, and the descriptions that are indeed the basis of our culture.

Twitter — @VRAMCPU

#art theory#philosophy#phi#psychology#theory#chomsky#habiuts#web science#black philosopher#aesthetic#art philosophy#Aesthetics

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Conversation with David Panos about The Searchers

The Searchers by David Panos is at Hollybush Gardens, 1-2 Warner Yard London EC1R 5EY, 12 January – 9 February 2019

There is something chattering. Alongside a triptych a small screen displays the rhythmic loop of hands typing, contorting, touching, holding. A movement in which the artifice strains between shuddering and juddering. Machinic GIFs seem to frame an event which may or may not have taken place. Their motions appear to combine an endless neurotic repetition and a totally adrenal pumped and pumping tension, anticipating confrontation.

JBR: How do the heavily stylised triptych of screens in ‘The Searchers’ relate to the GIF-like loops created out of conventionally-shot street footage? DP: I think of the three screens as something like the ‘unconscious’ of these nervous gestures. I’m interested in how video compositing can conjure up impossible or interior spaces, perhaps in a way similar to painting. Perhaps these semi-abstract images can somehow evoke how bodies are shot through with subterranean currents—the strange world of exchange and desire that lies under the surface of reality or physical experience. Of course abstractions don't really ‘inhabit’ bodies and you can’t depict metaphysics, but Paul Klee had this idea about an aesthetic ‘interworld’, that painting could somehow reveal invisible aspects of reality through poetic distortion. Digital video and especially 3D graphics tend to be the opposite of painting—highly regimented and sat within a very preset Euclidean space. I guess I’ve been trying to wrestle with how these programs can be misused to produce interesting images—how images of figures can be abstracted by them but retain some of their twitchy aliveness. JBR: This raises a question about the difference between the control of your media and the situation of total control in contemporary cinematic image making. DP: Under the new regimes of video making, the software often feels like it controls you. Early analogue video art was a sensuous space of flows and currents, and artists like the Vasulkas were able to build their own video cameras and mixers to allow them to create whole new images—in effect new ways of seeing. Today that kind of utopian or avant-garde idea that video can make surprising new orders of images is dead—it’s almost impossible for artists to open up a complex program like Cinema 4D and make it do something else. Those softwares were produced through huge capital investment funding hundreds of developers. But I’m still interested in engaging with digital and 3D video, trying to wrestle with it to try and get it to do something interesting—I guess because the way that it pictures the world says something about the world at the moment—and somehow it feels that one needs to work in relation to the heightened state of commodification and abstraction these programs represent. So I try and misuse the software or do things by hand as much as possible, and rather than programming and rendering I manipulate things in real time. JBR: So in some way the collective and divided labour that goes into producing the latest cinematic commodities also has a doubled effect: firstly technique is revealed as the opposite of some kind of freedom, and at the same time this has an effect both on how the cinematic object is treated and how it appears. To be represented objects have to be surrounded by the new 3D capture technology, and at the same time it laminates the images in a reflected glossiness that bespeaks both the technology and the disappearance of the labour that has gone into creating it. DP: I’m definitely interested in the images produced by the newest image technologies—especially as they go beyond lens-based capture. One of the screens in the triptych uses volumetric capturing— basically 3D scanning for moving image. The ‘camera’ perspective we experience as the viewer is non-existent, and as we travel into these virtual, impossible perspectives it creates the effect of these hollowed out, corroded bodies. This connects to a recurring motif of ‘hollowing out’ that appears in the video and sculpture I’ve been making recently. And I have a recurring obsession with the hollowing out of reality caused by the new regime of commodities whose production has become cut to the bone, so emptied of their material integrity that they’re almost just symbols of themselves. So in my show ‘The Dark Pool’ (Hollybush Gardens, 2014) I made sculptural assemblages with Ikea tables and shelves, which when you cut them open are hollow and papery. Or in ‘Time Crystals’ (Pumphouse Gallery, 2017) I worked with clothes made in the image of the past from Primark and H&M that are so low-grade that they can barely stand washing. We are increasingly surrounded by objects, all of which have—through contemporary processes of hyper-rationalisation and production—been slowly emptied of material quality. Yet they have the resemblance of luxury or historical goods. This is a real kind of spectral reality we inhabit. I wonder to myself about how the unconscious might haunt us in these days when commodities have become hollow. Might it be like Benjamin’s notion of the optical unconscious, in which through the photographic still the everyday is brought into a new focus, not in order to see what is behind the veil of semblance, but to see—and reclaim for art—the veiling in a newly-won clarity. DP: Yes, I see these new technologies as similar, but am interested in how they don't just change impact perception but also movement. The veiled moving figures in ‘The Searchers' are a strange byproduct of digital video compositing. I was looking to produce highly abstract linear depictions of bodies reduced to fleshy lines, similar to those in the show and I discovered that the best way to create these abstract images was to cover the face and hands of performers when you film them to hide the obvious silhouettes of hands and faces. But asking performers to do this inadvertently produced a very peculiar movement—the strange veiled choreography that you see in the show. I found this footage of the covered performers (which was supposed to be a stepping stone to a more digitally mediated image, and never actually seen) really suggestive— the dancers seem to be seeking out different temporary forms and they have a curious classical or religious quality or sometimes evoke a contemporary state of emergency. Or they just look like absurd ghosts. JBR: In the last hundred years, when people have talked about ghosts the one thing they don’t want to think about is how children consider ghosts, as figures covered in a white sheet, in a stupid tangible way. Ghosts—as traumatic memories—have become more serious and less playful. Ghosts mean dwelling on the unfinished business of the past, or apprehending some shard of history left unredeemed that now revisits us. Not only has no one been allowed to be a child with regard to ghosts, but also ghosts are not for materialists either. All the white sheets are banished. One of the things about Marx when he talks about phantoms—or at least phantasmagorias—is much closer to thinking about, well, pieces of linen and how you clothe someone, and what happens with a coat worked up out of once living, now dead labour that seems more animate than the human who wears it. DP: Yes, I’ve been very interested in Marx’s phantasmagorias. I reprinted Keston Sutherland’s brilliant essay on how Marx uses the term ‘Gallerte’ or ‘gelatine’ to describe abstract labour for a recent show. Sutherland highlights a vitalism in Marx’s metaphysics that I’m very drawn to. For the last few years I’ve been working primarily with dancers and physical performers and trying to somehow make work about the weird fleshy world of objects and how they’re shot through with frozen labour. I love how he describes the ‘wooden brain’ of the table as commodity and how he describes it ‘dancing’—I always wanted to make an animatronic dancing table. JBR: There is also a sort of joyfulness about that. The phantasmagoria isn’t just scary but childish. Of course you are haunted by commodities, of course they are terrifying, of course they are worked up out of the suffering and collective labour of a billion bodies working both in concert and yet alienated from each other. People’s worked up death is made into value, and they all have unfinished business. But commodities are also funny and they bumble around; you find them in your house and play with them. DP: Well my last body of work was all about dancing and how fashion commodities are bound up with joy and memory, but this show has come out much bleaker. It’s about how bodies are searching out something else in a time of crisis. It’s ended up reflecting a sense of lack and longing and general feeling of anxiety in the air. That said I am always drawn to images that are quite bright, colourful and ‘pop’ and maybe a bit banal—everyday moments of dead time and secret gestures. JBR: Yes, but they are not so banal. In dealing with tangible everyday things we are close to time and motion studies, but not just in terms of the stupid questions they ask of how people work efficiently. Rather this raises questions of what sort of material should be used so that something slips or doesn’t slip—or how things move with each other or against each other—what we end up doing with our bodies or what we end up putting on our bodies. Your view into this is very sympathetic: much art dealing in cut-up bodies appears more violent, whereas the ruins of your abstractions in the stylised triptych seem almost caring. DP: Well I’m glad you say that. Although this show is quite dark I also have a bit of a problem with a strain of nihilist melancholy that pervades a lot of art at the moment. It gives off a sense of being subsumed by capitalism and modern technology and seeing no way out. I hope my work always has a certain tension or energy that points to another possible world. But I’m not interested in making academic statements with the work about theory or politics. I want it to gesture in a much more intuitive, rhythmic, formal way like music. I had always made music and a few years back started to realise that I needed to make video with the same sense of formal freedom. The big change in my practice was to move from making images using cinematic language to working with simultaneous registers of images on multiple screens that produce rhythmic or affective structures and can propose without text or language. JBR: The presentation of these works relies on an intervention into the time of the video. If there is a haunting here its power appears in the doubled domain of repetition, which points both backwards towards a past that must be compulsively revisited, and forwards in convulsive anticipatory energy. The presentation of the show troubles cinematic time, in which not only is linear time replaced by cycles, but also new types of simultaneity within the cinematic reality can be established between loops of different velocities. DP: Film theorists talk about the way ‘post-cinematic’ contemporary blockbusters are made from images knitted together out of a mixture of live action, green-screen work, and 3D animation. I’ve been thinking how my recent work tries to explode that—keep each element separate but simultaneous. So I use ‘live’ images, green-screened compositing and CGI across a show but never brought together into a naturalised image—sort of like a Brechtian approach to post-cinema. The show is somehow an exploded frame of a contemporary film with each layer somehow indicating different levels of lived abstractions, each abstraction peeling back the surface further. JBR: This raises crucial questions of order, and the notion that abstraction is something that ‘comes after’ reality, or is applied to reality, rather than being primary to its production. DP: Yes good point. I think that’s why I’m interested in multiple screens visible simultaneously. The linear time of conventional editing is always about unveiling whereas in the show everything is available at the same time on the same level to some extent. This kind of multi-screen, multi-layered approach to me is an attempt at contemporary ‘realism’ in our times of high abstraction. That said it’s strange to me that so many artworks and games using CGI these days end up echoing a kind of ‘naturalist’ realist pictorialism from the early 19th Century—because that’s what is given in the software engines and in the gaming-post-cinema complex they’re trying to reference. Everything is perfectly in perspective and figures and landscapes are designed to be at least pseudo ‘realistic’. I guess that’s why you hear people talking about the digital sublime or see art that explores the Romanticism of these ‘gaming’ images. JBR: But the effort to make a naturalistic picture is—as it was in the 19th century—already not the same as realism. Realism should never just mean realistic representation, but instead the incursion of reality into the work. For the realists of the mid-19th century that meant a preoccupation with motivations and material forces. But today it is even more clear that any type of naturalism in the work can only serve to mask similar preoccupations, allowing work to screen itself off from reality. DP: In terms of an anti-naturalism I’m also interested in the pictorial space of medieval painting that breaks the laws of perspective or post-war painting that hovered between figuration and abstraction. I recently returned to Francis Bacon who I was the first artist I was into when I was a teenage goth and who I’d written off as an adolescent obsession. But revisiting Bacon I realised that my work is highly influenced by him, and reflects the same desire to capture human energy in a concentrated, abstracted way. I want to use ‘cold’ digital abstraction to create a heightened sense of the physical but not in the same way as motion capture which always seems to smooth off and denature movement. So the graph-like image in the centre of the triptych (Les Fantômes) in this show twitches with the physicality of a human body in a very subtle but palpable way. It looks like CGI but isn’t and has this concentrated human life force rippling through it.

If in this space and time of loops of the exploded unstill still, we find ourselves again stuck in this shuddering and juddering, I can’t help but ask what its gesture really is. How does the past it holds gesture towards the future? And what does this mean for our reality and interventions into it. JBR: The green-screen video is very cold. The ruined 3D version is very tender. DP: That's funny you say that. People always associate ‘dirty’ or ‘poor’ images with warmth and find my green-screen images very cold. But in the green-screened video these bodies are performing a very tender dance—searching out each other, trying to connect, but also trying to become objects, or having to constantly reconfigure themselves and never settling. JBR: And yet with this you have a certain conceit built into the drapes you use: one that is in a totally reflective drape, and one in a drape that is slightly too close to the colour of the greenscreen background. Even within these thin props there seems to be something like a psychological description or diagnosis. And as much as there is an attempt to conjoin two bodies in a mutual darkness, each seems thrown back by its own especially modern stigma. The two figures seem to portray the incompatibility of the two poles established by veiled forms of the world of commodities: one is hidden by a veil that only reflects back to the viewer, disappearing behind what can only be the viewer’s own narcissism and their gratification in themselves, which they have mistaken for interest in an object or a person, while the other clumsily shows itself at the very moment that it might want to seem camouflaged against a background that is already designed to disappear. It forces you to recognise the object or person that seems to want to become inconspicuous. And stashed in that incompatibility of how we find ourselves cloaked or clothed is a certain unhappiness. This is not a happy show. Or at least it is a gesturally unsettled and unsettling one. DP: I was consciously thinking of the theories of gesture that emerged during the crisis years of the early 20th century. The impact of the economic and political on bodies. And I wanted the work to reflect this sense of crisis. But a lot of the melancholy in the show is personal. It's been a hard year. But to be honest I’m not that aligned to those who feel that the current moment is the worst of all possible times. There’s a left/liberal hysteria about the current moment (perhaps the same hysteria that is fuelling the rise of right-wing populist ideas) that somehow nothing could be worse than now, that everything is simply terrible. But I feel that this moment is a moment of contestation, which is tough but at least means having arguments about the way the world should be, which seems better than the strange technocratic slumber of the past 25 years. Austerity has been horrifying and I realise that I’ve been relatively shielded from its effects, but the sight of the post-political elites being ejected from the stage of history is hopeful to me, and people seem to forget that the feeling of the rise of the right has been also met with a much broader audience for the left or more left-wing ideas than have been previously allowed to impact public discussion. That said, I do think we’re experiencing the dog-end of a long-term economic decline and this sense of emptying out is producing phantasms and horrors and creating a sense of palpable dread. I started to feel that the images I was making for ‘The Searchers’ engaged with this. David Panos (b. 1971 in Athens, Greece) lives and works in London, UK. A selection of solo and group exhibitions include Pumphouse Gallery, Wandsworth, London, 2017 (solo); Sculpture on Screen. The Very Impress of the Object, Gulbenkian Museum, Lisbon, Portugal [Kirschner & Panos], 2017; Nemocentric, Charim Galerie, Vienna, 2016; Atlas [De Las Ruinas] De Europa, Centro Centro, Madrid, 2016; The Dark Pool, Albert Baronian, Brussels, (solo), 2015; The Dark Pool, Galeria Marta Cervera, Madrid, 2015; Whose Subject Am I?, Kunstverein Fur Die Rheinlande Und Westfalen, Düsseldorf, 2015; The Dark Pool, Hollybush Gardens, London, (solo), 2014; A Machine Needs Instructions as a Garden Needs Discipline, MARCO Vigo, 2014; Ultimate Substance, B3 Biennale des bewegten Blides, Nassauischer Kunstverein, Wiesbaden, (Kirschner & Panos solo), 2013; Ultimate Substance, CentrePasquArt, Biel, (Kirschner & Panos solo), 2013; Ultimate Substance, Extra City, Antwerp, (Kirschner & Panos solo), 2013; The Magic of the State, Lisson Gallery, London, 2013; HELL AS, Palais de Tokyo, Paris, 2013.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Movement Statement

Over the last three weeks each of the lecturers have presented us a different definition of movement. This has been really helpful, as the broadness of ‘movement’ makes it easy to latch on to the first definition you come to. I spend the three weeks exploring the concept of movement and motion to find a direction that I thought was interesting and that had enough scope to be turned into a concept for studio.

To me, one of the core aspects and abilities of Creative Technologies is to translate a complex concept into something more accessible. The technology allows the project to exist and function, either in a physical or digital space where an audience can experience it.

The art side of Creative Tech informs the concept, and the conscious and subconscious effect the piece has. It develops the message, and can elicit emotion and thoughtfulness.

These two hemispheres do no work apart, but instead feed to and from each other In a constant feedback look. As a concept informs the specifics, so too do the technicalities affect the aesthetic. This dichotomy is at the heart of the creative technology discipline, and a practitioner must have ‘a foot in each’. Technology and art are hugely broad terms, and each project will enlist one or more previously discrete practices into each category. The outcome of this hybrid practice is greater than the sum of its parts, and not only the work but the workflow itself is unique and distinctive.

This is the aspect of creative Technologies that I am most passionate about – creating moving and thoughtful outcomes that have a valid message or question, and communicating that in a way enabled by technology. The thoughtful and critically creative application of technology can create incredible, impossible experiences for audiences. A conceptual and ideological synaesthesia, a potent translation between once disparate pillars of human experience.

One of my main influences from the lectures was “Meeting the Universe Halfway” [2], a book by Karen Bard. The book is about Agential realism, that existence is secondary to an intra-action, and those agents exist because of the action, not the other way around. This seems counterintuitive and farfetched, but if you take a second to ponder it you begin to look at the world differently.

I like to think there is a difference between ‘knowing’ and ‘believing’ – knowing being conscious thought and memory, and believing being the domain of the subconscious.

By focusing it seems like we can manually interface with our subconscious. You can convince yourself that no object exists without intra-action and that agential realism is the true mechanic of our universe, in a real and tangible sense. You can bridge the gap between knowing and believing, and for a moment your world changes because you’ve changed the way you perceive it. In that moment, things have deeply different instinctive (subconscious /believed) feeling, because you are able to believe a theory like agential realism, instead of just knowing and accepting it, and it becomes the truth that your brain runs on, the unconscious absolutes of your reality.

But the things experienced and intra-acted with exist differently now because they are being perceived and intra-acted with differently. The act of engaging with an agent creates and defines that agent; that is the core idea of agential realism, demonstrated by thinking about agential realism. I love the idea of being able to have influence over your own mind, to have the feeling of experiencing reality through another lens, one that you didn’t know could be changed. Because of this, I was drawn to research how humans experience movement.

First, how do humans perceive or detect movement? Movement can’t exist as an instant. It needs a frame of reference and context. To identify a movement, we need to know something’s state in the past. With that we can tell how fast and in what direction something is moving. This isn’t just physical, mechanical movements. This could be a social movement, where ideas or opinions spread and move through people and communities, however what interests me most is the physical movement because of its effect on humans. An object moving towards you will trigger a subconscious reaction and sensation.

This has a lot to do with how humans experience time. Unlike computers, time as a human experience is not definite, as we have no internal clock running to second or millisecond accuracy.

As far as movement, an important part is what we experience as “now” – the present. According to many sources [1] our experience of now is not a linear “knife edge” but instead “has a complex texture”. This is known as the specious present – a short duration of time (less than a second) that we experience as ‘now’. One key point is that there is always a ‘center’ to the experience of the present [1], with the trailing events moving from ‘now’ to ‘now but not central now’ to ‘past’.

During my interrogation of what movement was, I had an idea for a project. The idea at first was from Physical computing as a test application for some stepper motors I had bought. I thought it would be interesting to enter a location on earth into a processing sketch and have a ‘pointer’ driver by two stepper motors point at that location. Because we live on a sphere, the location would generally be downwards. As I though more about this idea, I began to see the merits of its concept. We know that country like – for example - Germany exists, but in a somewhat abstract sense. Maybe you think of it on a map, or even as “up” - as it would be in relation to us on a model globe. What we don’t think of is literally ‘where’ a country would be.

If someone asked you where the Sky Tower or Rangitoto was you would be able to point at them. They are of a scale that we can understand. This goes back to my ‘knowing’ vs ‘believing’ idea – we know we live on a sphere (oval), but we don’t believe it. It isn’t how we relate to the world, because it’s too large.

This little pointing gadget would be a perfect example of that core Creative Technology tenet of translation or transposition. Our ability to understand the gesture of a point, and apply that to the knowledge that this technology has calculated its point to show exactly where a given location is to us can give a momentary collapse of knowing into believing. Even when thinking through the experience of interacting with this piece, you are suddenly aware of the planet, the sphere hurtling through space that we live on. You feel yourself making the connection between the pointer aiming itself at a seemingly arbitrary point on the floor, the significance of that motion, and then the implications of where it is pointing. The planet is at a scale too large for us to believe, we can’t hold that in our subconscious. For a second the Earth shrinks to the size of a ball in front of you, and it feels tangible. This fades and as the instinctive and abstract reconcile, your experience of life and knowledge of where it takes place mesh.

This is where I found my starting point for the studio project, and what aspect of movement I wanted to focus on – the human sensation of movement and how that can be triggered to communicate an idea. Because these reactions are so deeply embedded in our subconscious, they have a large and lasting effect on us – more than a static piece of the same caliber could. Movement can tap into the most primal of human instincts.

The feeling of really ‘being on a planet’ that the pointer idea had made me feel stuck with me. I wanted to interrogate further down this path of inquiry, and see how that could link to movement. The obvious answer is our orbit around the sun. At 500 meters per second, we are all in motion, but the frame of reference and scale mean we don’t experience it. Our senses work on a smaller scale, and depend on the gravity of earth as a stationary constant.

Maybe a pointer that followed the Sun or other celestial bodies could give people the sensation of orbiting by providing an ‘artificial reference point’ for the movement.

[1] The Specious Present: A Neurophenomenology of Time Consciousness from: Naturalizing Phenomenology: Issues in Contemporary Phenomenology and Cognitive Science Edited by Jean, Petitot, Francisco J. Varela, Bernard Pachoud abd Jean-Michel Roy Stanford University Press, Stanford Chapter 9, pp.266-329

[2] Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning Author(s): Karen Barad, Published: 2007

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Write-Up

Work Statement

Splitting The Sky is a narrative VR experience based in a world in which the boundaries between the virtual and the actual have been dissolved. The experience was created using Unreal Engine, a video games engine capable of running VR in real time. The vulgar, warped views of extreme sexuality has seeped out of online pornography and coalesced with the surface internet. As the player wanders further and further this ‘digital’ world mirrors the way sexuality, power, dominion and abuse have become normalised through this spread. A desolate, ruined city stands alone in an uncanny valley-esque world amalgamated from the digital and the corporeal. As the player comes to, their only tangible company is a giantess who takes an almost sadistic glee in leaving chaos and destruction beneath her, and the cult-like followers that make no effort to proselytise the player, as the world operates through their fetishes. The player experiences manifestations of both trauma and healing; their means of guidance coming through refuge across the world, away from the female gaze of the giantess. This world exists as a postulation of how a digitally pervasive world will cope with therapy in a world where abnormal sexual desires and deviance are normalised; in a world where one brazenly champions another’s desire to be consumed, what measures will we take to seek help? When we live connected to a ubiquitous global system containing more damaging sexual material than any other media- one where its users are consciously using the computer as a means to detach from what they consume- where will the line be drawn before it is considered too far? In spite of this ominous future, Splitting the Sky is designed to encourage players to feel safe in themselves and their own capacity to heal. The concept of ‘healing’ itself is speculative and nebulous- it is something vague, undefined, but also something that one chooses knowingly to seek. The VR headset is imperative as a subversion of the imprisonment caused by traumatic events; during flashbacks to significant, negative memories the brain feels like a cage one cannot escape from. Using VR, Splitting the Sky is designed to remind players they can heal in these same spaces, with the internal mantra being one of escape- leaving one’s prison and emancipating the mind.

Conceptual Overview

Themes

Initially, I wrote short poetry and notes inspired by the idiosyncrasy and personality of diary writing, and felt there were a lot of continuing themes that I felt worked really well to create visual metaphors and could build the concept of the work. These were elements such as the sword, divine beings, and warping the perception of space and time through traumatic experiences. To sufficiently explore these themes, I decided to combine my research: analysing the progenitive factor in my own interest on the subjects as well as academic studies done more broadly around them. My confessional words reused in a story transformed them (and their meanings) into motifs of my fictional world.

I created moodboards for the narrative (x), visual (x) and sound design (x), that helped me to identify the themes better.

VR

Viewing Jordan Wolfson’s 2017 work ‘Real Violence’ was the catalyst that pushed me to pursue working with VR. Beyond my interest in the concept of alternative perceptions of reality augmented by technology as shown by my previous work, studying VR theory brought those ideas to the surface to build my own method of storytelling, where the protagonist, the user’s perspective, can be a material to directly manipulate. VR holds an interesting dichotomy; although the screen engulfs the senses of the viewer so thoroughly as to make it almost seem real, there is always a disconnect between the body and the brain when using it that reminds us it cannot be real. This idea resonates strongly with the themes presented in Wolfson’s work because it is tense and unsettling while remaining comedic and ironic- a self-awareness that everything does ultimately take place in virtual reality.

I was drawn first to the unsettling, discomforting aspect of Wolfson’s ideas, and that was something I aimed to replicate in my own work early on in the design process.

I had previously been interested in narrative theory and feminist storytelling, so these interests formed my intention to use VR very early on. The way a story is experienced in VR can be very different to other media, and the theory of VR backed up a lot of ideas I already had.

Giantess

Giantess pornography, and its audience, helped to create a visual language for the work, in order for me to approach trauma on the internet, and its effects on people in real life. To me, the giant sexy woman represented the dichotomy between exploitation and empowerment, seeing as the giantess is used for only sexual purposes in order to satisfy a male. The giantess appears God-like to me, in her power and her alienation, no one can relate to her. (x) I took this and created a Giantess character who was complex and wanted to express that in her words and actions within the story.

I also took words from Giantess porn videos (x) and the comments on those videos (x). I thought the language people used in the comments was very poetic, and felt the heaviness of the statements was diluted by that. This meant there were statements that were extremely derogatory towards women, but represented my point extremely well.

Sound Design

I performed quite a bit of research into the sound design, because in the beginning I was inspired by video game soundtracks (x)(x), and wanted to create a simple soundtrack of my own. I had collected sound effects I liked from synthesisers and FreeSound.org, and even planned what kind of music and sounds would be in each scene. However I felt I didn’t have enough music skills to really push it in the time that I had, and felt the work was still great without sound.

Video Games and Fantasy

Video games, such as Morrowind (x), experimental indie games (x), Metal Gear Solid (x), and more (x), were the basis for a lot of inspiration and research for this project. I felt that a fantasy narrative could be carried really well if I could understand elements of games and ludic game theory (x). As well as this, some lines from my script were lifted from games and recontextualised. This was intended to reference the type of language used in games and fantasy, and create a veil of irony that was both serious and comedic. While the concepts remained quite serious, in order to express this virtual-actual crossover world correctly, I felt it necessary to reference other media.

Healing

Nearing the works completion, I wanted to imagine an ending that could be satisfying and coherent with the rest of the ideas. I thought that in order for this work to be beneficial, rather than cynical and negative, I had to communicate a desire to heal from the personal and collective trauma the work was based on (x). To get to this point I wrote extensively about the theory and concepts of the work (x). The world in which the story takes place exists as a mental and physical space that the ‘user’ becomes involved with whenever they have flashbacks. Therefore the Giantess, the one who suffers and wishes to heal (and escape the world in which she is exploited), should talk directly to the player and pass on a message of healing. In the writing, this worked very well to conclude the work, and works in conjunction with the beginning.

Scenes

Each scene was designed to reflect the landscape of the psyche. The order of the scenes was integral to the story, as the visual and audio aspects needed to work in harmony to tell the story. The player is sent on a journey that is both inside their mind and outside in a fantasy world, meaning that time and place are non-linear.

Technical Overview

I knew I wanted my work to be displayed in VR for my purpose. I had created a project in Unity for another module project, but I was more interested in using Unreal Engine based on the improved quality of the VR applications I’ve seen using it. I struggled with writing C# scripts in Unity, whereas Unreal Engine used C++. I also noticed that Unreal Engine is used a lot within the professional video games industry, and showing my ability to learn its usage would be a great skill for me to demonstrate. Learning about Unreal Engine was a steep learning curve, as well as learning about functions of Blender beyond what I previously knew.

Getting Started