#important occurrences that can be paralleled with real life either it be related to the system politics morality humanity societal etc

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

i definitely agree with you. i think everything you said is accurate. nevertheless, i also believe we're just referring to things by different names and that what you wrote, what i intentionally meant and how this post has been interpretated so far aren't necesseraly mutually exclusive.

first of all, i think it was very clear that when i used the word "love" it was in a very broad definition and not directly romantic and/or platonic towards people. i meant towards ideals, life itself and whatnot. it really comes to personal choice and interpretation here but what isn't about love? one can say love is in everything in this world and one can debate it's not. and well, clearly i created this post with the former in mind. it was never meant to devalue the impact of tragic hapoenings or unjust circumstances in everyone. and it was never exclusively about interpersonal relationships. so, again, i think it's safe to say your opinion is very much a fact. it just happens my original thought was almost using love and humanity interchangeably. but of course, you don't have to agree with linguistic choices like that.

in the end of the day i do believe geto and gojo's connection was important in jjk and that their care for each other was shown for each other throughout the series despite the moral duty of the task gojo was assigned with. and even in that specific scene it's safe to say they both expressed it. i do think geto's unwillingness to convince gojo to join his path despite explaining to him the position he was in and gojo's overall disappointment and desire to continue to be together demonstrate fondness. and although in that moment in front of kfc it was probably not the time or place to procede with this duty to kill geto, he had 10 years to do so. but he never did. one can arguable discuss why. if fondness for the other is an option? maybe. if gojo obviously has a reason to be so shocked in shibuya seeing his dead best friend's body appear in front of him? oh, definitely. how trauma triggering must it have been?! but is it not affection when he addresses suguru directly and asks him how he allows this stranger to use his body? is it not affection when he revives all those moments he spent with suguru in his head? when he recognizes that person isn't his best friend but someone else ignoring even the thing he relies on the most which is his power? i personally believe it is. and i don't think it has to be romantic or the exclusive and main driver of the story to be appreciated.

regarding yuuta and rika, i think you're correct. rika is a projection. their story is incredibly complex. and their interpersonal relationship is too. but why does this curse exist in the first place? it's not even a stretch to use love to describe yuuta and rika's connection when it's exactly the word used by the characters to talk about it. and again, it doesn't have to be romantic. they are, or they were, kids after all.

yaga's death wasn't pretty or beautiful or a love act itself. i think that's obvious and no one really claimed that. but didn't he show care for panda? which he treats like his own son? doesn't panda mourn this loss? doesn't yaga have ideals he wants to preserve and something he was fighting for? didn't he learn from the tragic situation with geto and decided to fight with the little power he has to better prepare and support the students of that school? he did. it's not a deviation to say those are things he values. and again, something we value can be extrapolated to be something we love. but as i mentioned, that's a personal linguistic and interpretative choice. yet, the common theme found in these moments can't really be denied. in my view, at least. even if it isn't the sole and lone motivator behind them.

"jujutsu kaisen isn't a story about love" then explain why everything that happens and each person's strength and/or weakness is derived from this mundane and very specific feeling one can have for another or something else. i'll wait.

#i just woke up and don't even know if this makes sense but i wanted to answer because i do like your answer and it touches important things#if there's anything i don't like is overly symplifying jujutsu kaisen which is a very rich story that speaks and demonstrates very#important occurrences that can be paralleled with real life either it be related to the system politics morality humanity societal etc#and i hope people read the manga or watch the anime and are critical of these things because they're absolutely being portrayed#intentionally for it#but i also like to 'romanticize' (put a quote on that) things and see this part of what it means to be human in all the characters#because i do believe being human and loving are not that far apart and are in fact almost the same#so yeah i wanted to answer it's probably not eloquent or any of that or any type of analysis so sorry for that#and i used first person in the text because i do not want to speak for others but i also believe those who rebloged this post probably#interpreted it in similar ways (at least from what i read)#thank you so much for stating your opinion and bringing these things into the conversation!!!#i believe these conversations are valuable and hope this isn't interpreted as disagreement because it's not ahaha#also sorry for any mistakes i didn't really proof read

675 notes

·

View notes

Text

The East Asian Origins of the Fire Nation and Its Villains

Introduction

Over the years, many volumes of fandom blood have been spilled from discussions concerning the Fire Nation’s main villains, Ozai and Azula. Paralleling this have been arguments over their relationships with Zuko, Iroh, Ursa, Mai, Ty Lee, with each other, even with themselves. Since Ozai and Azula are the figureheads of the Fire Nation that Zuko must peacefully restore the honor of, it is worthwhile understanding why people “like them” are considered proper leaders of the current Fire Nation.

Most of these discussions have sought to create “theories” that explain these characters as exclusively combinations of mental illness, personality disorders and various emotional traumas.

A couple examples of these discussions are the essays “Azula, the Embodiment of Jealousy and Neglect,” and “Three Pillars Theory of Azula.” These two essays are just examples, but they capture the widespread strategy the fandom has employed in trying to understand the motivations and goals of Ozai and Azula and their various relationships with the other characters. In addition, the shouting matches between Azula “fans” and “haters” also illustrates these discussions. Since the franchise has yielded so few hard answers, these importance of these discussions has not waned.

What these discussions focus on, as represented by those essays, are the characters’ apparent emotional problems, theoretical moral compasses and perceived inadequacies in the eyes of their families. Typically, the “lens” these discussions view these villains through is one that tries to relate them to present day spousal and domestic abuse narratives, namely as being both “abuser” and “victim” in a cycle of abuse that can be related to the modern, real world.

What these conversations do not provide are adequate explanations for how the historical, political, military and cultural aspects of the Fire Nation molded these military leaders. You would think that people with “Lord” and “Princess” in their names, who train daily for warfare and hand-to-hand combat, would make their responsibilities take center stage in their lives.

While there is a place for “nitty gritty” psychological examinations for understanding certain behaviors, trying to depict the Fire Nation villains as purely allegories of modern day domestic abusers, empathy deficient bullies and people afflicted by personality disorders eliminates Avatar’s most unique and defining characteristic: its East Asian origins.

You don’t need beautiful animation, martial arts-styled bending and immersion in a fantasy world to explain how families in the modern era can hurt their children for petty reasons. We have that in our own lives. We have friends and families who have experienced that. It can be addressed in any other setting. It can be addressed in Avatar but it doesn’t need Avatar to address it.

What we don’t experience in our modern lives is ancient China 2000 years ago, or feudal Japan after the takeover of the Tokugawa Shogun, or religious monks living in their temples in the mountains untouched by the modern world, and so on.

The setting of Avatar is one of both beauty and relative detachment from the real (and modern) world, but it is one that is based on a period of history and human civilization that most of Avatar’s audience (North America and Europe) have little exposure to. If the characters’ motivations are too detached from the fictional world in which they live (i.e. by ignoring the historical, political, military and cultural context), then you begin to lose the world’s depth. At the same time, if their motivations are too connected to the present world, then all Avatar is is a visual motif of ancient East Asia.

By seeking to explain the Fire Nation villains as embodiments of modern psychology’s understanding of “bad” people, you erase the opportunity to apply East Asia’s very real history of warfare, monarchical domination and oppressive cultures to a fictional world that is trying to say something about that warfare, monarchical domination and oppressive cultures. Note that the show did in fact achieve this with the Dai Lee’s corruption and manipulation of the Earth King; it depicted loosely the very real occurrence of Chinese Emperors being “kept in the dark” by their advisors so as not to interfere with the “real” governing of the states.

If your goal is to view Avatar purely as an allegory for modern dysfunctional relationships and domestic abuse, you lose Avatar’s uniqueness as a fictional dive into an East Asian-inspired world, especially one that is ravaged by warfare and feudalism.

In this article, I describe an alternative model for understanding the Fire Nation’s culture and history, and how its politics and military molded its heroes and villains.

What We Know and Might Know

In order to fill the gaps in our knowledge of the Fire Nation, we first have to understand what is both known about the Fire Nation and what can be reasonably presumed about it.

First, what do we know about the Fire Nation?

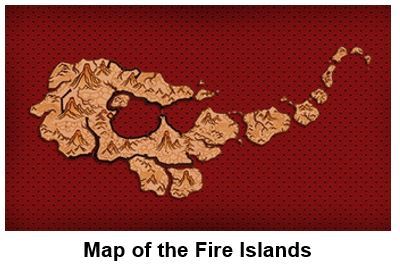

1. The Fire Nation is an archipelago with a history spanning thousands of years.

2. The Fire Nation was originally the “Fire Islands” and was not initially governed by a central power.

3. The Fire Islands had a unified cultural and religious authority in the form of the “Fire Sages”.

4. Eventually, the Fire Islands were unified by a single power—the “Imperial Government”—and afterward became known as the “Fire Nation”.

5. The Imperial Government is headed by a supreme ruler: the “Fire Lord”.

6. The Fire Lord is a hereditary monarch whose family is considered the “Royal Family”, both of which are separate entities from the Fire Sages.

7. The Fire Sages remain a distinct entity from the Imperial Government.

8. Both the Fire Lord and Royal Family are military and administrative rulers.

9. The Fire Lord and their Royal Family are not sacred and everlasting; their power can be “challenged” by rival leaders.

10. Fire Lords are expected to “show their worth” and be competent fighters in their own right; prowess in military arts and control of subordinates are valued traits.

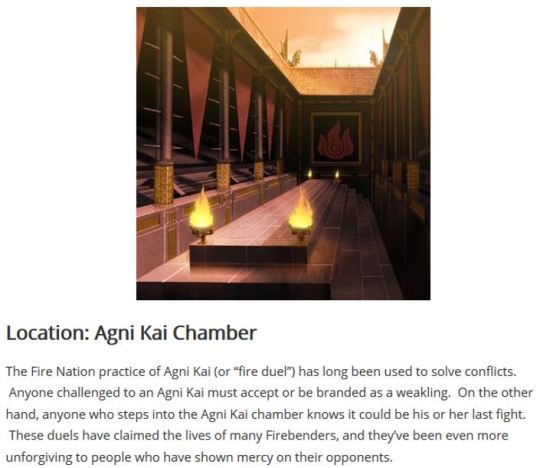

11. Agni Kais are a longstanding component of Fire Nation culture.

12. The Fire Nation experienced an “unprecedented time of peace and wealth” during the era of the Fire Nation, not during the era Fire Islands.

Next, what can be reasonably presumed given what we know?

Something necessitated the Fire Islands becoming unified, but this unification did not result in the Fire Sages taking power, nor did it yield a peaceful, democratic government.

The Imperial Government that resulted from this unification is rooted in military control and maintaining the fealty of its subjects; in Avatar and the Fire Lord, Sozin put on his “ruler persona” to Roku initially before acting friendly, only later to demand loyalty from him as if Roku was any other subject.

The culture of the Fire Nation values strength and bravery from its firebenders, as explained in an official description of Agni Kais. Presumably, the Agni Kai predates the era of the Fire Lord and has been used to settle disputes of various kinds. This could be interpreted as a “non-destructive” means of avoiding war and greater loss of life given how easily firebenders could wreak havoc to wooden buildings and crops (among other flammable components of society). Since nobody recognized Zuko on Ember Island in The Beach, despite his obvious scar, severe scars from burns must be common enough in the Fire Nation that a teen boy having one on his face is not horrifying nor particularly unattractive.

Presumably, the Fire Nation/Fire Islands used to hold its religion and spiritual ties in higher regard, but Sozin’s start of the war required this aspect of the Fire Nation to be suppressed, as implied by dragon hunting and the divided loyalties of the Fire Sages at Roku’s temple, and the fact that various generals and admirals have defected. At the same time, vast enough swaths of the country and its leadership did follow Sozin’s path, considering that he and his family remained in power for over a hundred years. If Fire Lords can have their power challenged, then either nobody tried to stop Sozin, or they were defeated. Azula’s comment about “rumors of plans to overthrow him (Ozai)” in The Avatar State implies betrayal of the Royal Family is not a dormant threat. Though she was technically lying, it must have been a credible lie since neither Iroh and Zuko thought it was preposterous; his brother being “regretful” is what puzzled Iroh, not that there would be plots against the Fire Lord.

Notably, the Fire Lord’s throne room changed between the start of the war and the present day. Prior to Sozin, it did not have the imposing wall of flame as it does now. Certainly it had to be rebuilt after Roku destroyed it, but the wall of flame is much more imposing than the old.

The Fire Sages still pay a role in the Fire Nation, but this role is not known. Presumably, they play some part in the succession of the Fire Lord since they preside over coronation. Perhaps the relationship between the Fire Lord and Fire Sages is similar to the relationship between the Japanese Emperor and the Shoguns, where the Shoguns held the true power in the country (military and administrative) whereas the Emperor maintained a facade of power as a cultural and religious symbol. What is known about the Fire Sages is that they have a temple in the capital and are divided between their loyalties to the Avatar and the Fire Lord.

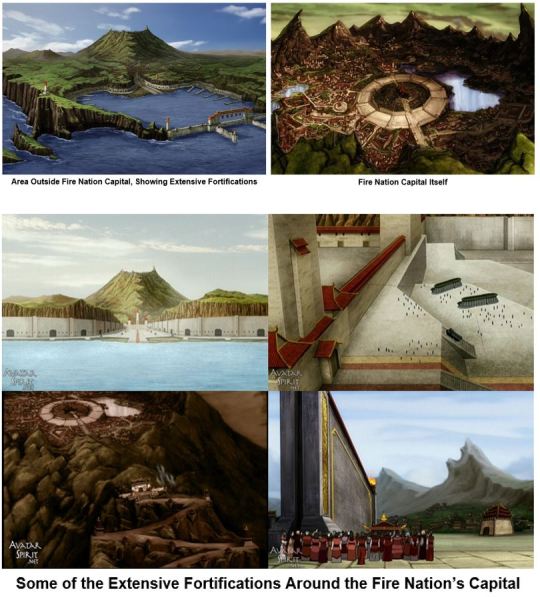

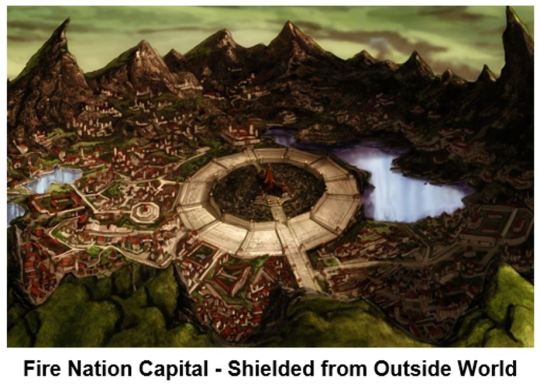

Finally, the Imperial Government’s capital is located in an isolated, fortified city inside a volcano’s caldera, where coming-and-going is strictly controlled. The city is large, full of nobility, physically disconnected from the external port city (versus directly being the hub of economic activity) and contains numerous underground bunkers.

Why would the Capital require such extensive bunkers and fortifications? Presumably because the Fire Lord and Royal Family can be “challenged” and the bunkers are a defense mechanism against both external and internal threats. The Fire Nation did have a “darkest day” tied to solar eclipses, which suggests that the loss of firebending had profound military consequences. Whatever the reasons, the Imperial Government is so concerned about its survival that it has constructed massive fortifications around its capital, implying that warfare is a major concern.

Areas of Confusion

But what does all of this mean?

Was the Fire Nation previously peace-loving and compassionate while Sozin is responsible for all of its “evils”?

Have Agni Kais been performed for centuries and so Zuko being challenged to one was neither unusual nor particularly grotesque for the Fire Nation’s culture?

Did Sozin face massive opposition to starting the war or was everyone humbly obedient to the Fire Lord?

How is a Fire Lord’s rule challenged?

Why wasn’t Sozin overthrown if he had to “impose” the war upon the country?

Why did the Fire Lord come to existence in the first place?

Why has the Imperial Government not been replaced by the Fire Sages?

Why does the Fire Nation need a national government?

What is a more compelling explanation for the Fire Nation’s villains other than mental illness and personality disorders?

As it turns out, there is a way to understand the Fire Nation that adequately fills in the gaps, explains its heroes and villains and provides a lesson on East Asian history.

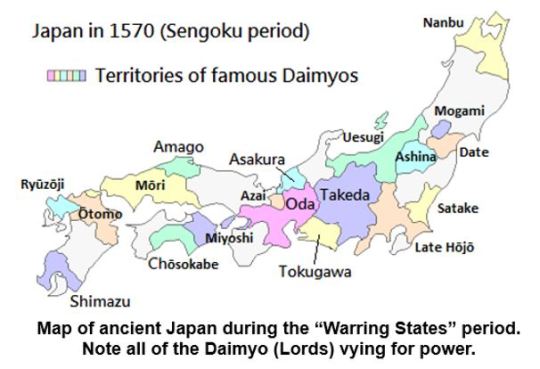

A Brief History of Ancient Japan’s Unification

The islands of Japan have been populated for tens of thousands of years, but the “modern” era of warlords and emperors did not begun until the past 1500 years or so. While the Japanese people were not united under a single state, there was an “Emperor” who was believed to have been descended from a goddess. Despite this first emperor having control over a certain portion of Japan, it did not take long until the country split into separate feudal states.

While the Emperor never went away, their power over the country waned. The real power in Japan laid in the hands of the various feudal lords (daimyo), who used their armies to defend their territories and capture new ones from other lords.

Since the Emperor represented a shared cultural connection among the people, their power was not completely absent. In the earlier parts of history, before the Emperor became completely subordinated, the Emperor would appoint a Seii Taishōgun, or supreme commander, of the Emperor’s armies. Eventually, this “supreme commander” became the actual ruler of the Japan since they controlled the military. By appointing them “shogun” they more or less had the public approval of the Emperor despite the Emperor not actually being able to control them.

Various shoguns came and went, but through it all were the daimyo using their samurai to battle for control of the country. Ruthlessness and murder were common. Building alliances only to later betray them were often wise tactics. For a thousand years, the rulers of Japan lived by the sword, died by the sword and used it to maintain their power. Things got particularly bad during the Sengoku Period, which is considered the “Warring States” period of Japan. That tells you all you need to know.

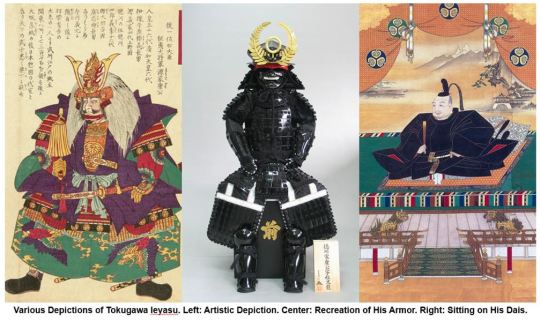

It was during this time that one of these feudal lords rose to power, a man named Tokugawa Ieyasu (first name Ieyasu, last name Tokugawa). Using a combination of political tact, military genius and European steel breast armor, he defeated all other daimyo during the Azuchi–Momoyama period and installed himself as the shogun of the Tokugawa Shogunate. This marked the end of over a thousand years of continuous violence and social turmoil in Japan.

The Tokugawa Shogunate represented Japan’s first unified national government. The country’s existing daimyo were placed under strict control to ensure they did not rebel. The military was nationalized and the existing feudal governments rearranged to ensure centralized control by the Shogun in his capital at Edo. Notably, Edo became modern day Tokyo.

National laws were written, along with cultural and religious standards to ensure social cohesiveness, stability and control. The economies of Japan also flourished, especially in the cities. A consequence of the Tokugawa Shogunate, however, was closing off Japan to the outside world. The Shogun wanted to ensure their rule and control of the populace. Allowing other countries to influence them and provide assistance to competing powers within the country was viewed as destabilizing.

A particularly unique aspect of the Tokugawa’s politic strategy was requiring the daimyos’ families to live in the capital while the daimyo themselves had to go back and forth between their homes in their territory (called a domain) and their homes in the capital every other year. The Shogun essentially held the daimyos’ families hostage to ensure they would not rebel or work against him, although they lived in the comfort and relative freedom of a modern city, not as actual prisoners.

Another tactic the Shogun utilized to quell rebellion was to keep careful control of who entered the city of Edo and its surroundings. Guards were at all entrances and major roads and registries were kept of all people. Essentially, if you weren’t suppose to be somewhere, you weren’t allowed to be there.

Bushdio also developed during this period as way of controlling the warrior class, and was much more complicated than most Western depictions. With war and feudal fighting no longer a constant threat, the samurai class became enforces for the new government. Naturally, the Shogun was particularly interested in controlling them.

Control is a common theme of the Tokugawa Shogun’s government.

The Tokugawa Period was one of peace and stability, prosperity and enjoyment of the arts, but Ieyasu Tokugawa was not a nice person. He hunted down and executed the families of rival clans, including kids, during the takeover. He held families hostage and made sure his subordinates feared him and never stepped out of line. He enacted strict laws to control the populace and made sure no one could challenge him and his government’s reign. And it worked. Japan did not experience another war until the end of the Tokugawa Shogunate 278 years later, when the Emperor regained control and ended the era of isolationism. There’s a reason why modern day Japan doesn’t view this period with derision and loathing; given the context of the time, it was a proud moment for a region racked by warfare and division.

A pattern is beginning to emerge: an island nation ruled by feuding lords with no central power to direct them; a religious and cultural figure with no real power; a period of intense warfare and turmoil followed by a lasting period of unification and prosperity; a powerful central government headed by a hereditary monarch who took power using ruthlessness and military might; a hereditary monarch who rules through fear and demands fealty; a capital city with strict control of who comes and goes.

Themes of control and subordination from a central power.

This is sounds very familiar.

The Military and Political History of the Fire Nation

The history of ancient Japan provides a real-world model for understanding the origins of the Fire Nation’s Imperial Government, the Fire Lord and why they rule through fear and military domination. Keep in mind that the Fire Nation is not Japan, but warfare, centralized control and a desire for peace and stability are universal. Ancient Japan’s experience with feudalism, warfare and the eventual peace that came from having a competent central authority can go a long way in applying Avatar’s “East Asian origins” to the Fire Nation and its villains and heroes.

Using the rise of the Tokugawa Shogunate as a template, the history of the Fire Nation looks like this:

The Fire Islands were ruled by various feudal lords. These feudal lords engaged in warfare with each other as they vied for ever increasing control. Firebending was the primary source of these lords’ military might. The Fire Sages were recognized as spiritual and religious leaders by the Fire Islands people, but they did not have the practical power necessary to enforce peace upon the lands.

At the same time, firebending was recognized as being fundamental to the influence of the Fire Sages and the power of the feudal lords. Since fire can destroy houses, burn fields, melt iron and lay waste to non-bending armies, whoever can control and weaponize firebending for their own purposes will attain the most power. On the other hand, this also makes warfare particularly destructive as even small rebellions could lay waste to cities given how much fire a single firebender can unleash.

At some point, in order to put a stop to the fighting, a central authority came to power, either as one of those warlords or a Fire Sage acquiring enough military and political power. Maybe an avatar helped them. Without a doubt, military might had to have played a role in ending the “Warring States” period of the Fire Islands.

In order to make sure the Fire Islands did not fall back into fighting and remained peaceful and stable, this new central authority created a sweeping national government to control them. Thus are the beginnings of the Fire Lord and Imperial Government.

Because the Fire Nation is full of people with ”desire and will, and the energy and drive to achieve what they want” (in the words of Uncle Iroh), the destructive capacity inherent to a nation full of firebenders must be kept under strict control; if the goal is to create a prosperous, flourishing society, you cannot allow it to be destroyed periodically by walking flamethrowers.

As a result, the Imperial Government is not a “friendly” entity. It controls the nobility and lords who act as the local “vassals” in their home territories; it amasses a large, overwhelming military to quash any attempts at rebellion, and to send a clear message to its people to not even try; it uses fear and threats of violence to control the people who might feel the “drive and willpower” to try their hand at acquiring wealth and power through force.

The Agni Kai exists as a means of settling conflict without the destructive consequences of firebending. Perhaps a Fire Lord enacted this to further tamp down on firebenders’ destructive tendencies. It may also be an example of how the Fire Nation’s “warrior class” handles internal disputes in a similar manner as bushido.

Bravery, ferocity and a willingness to fight are valued in the leadership of the country because the Imperial Government is supposed to be a military entity first; how can the Fire Lord, their family and government inspire fear in the people if the people don’t believe they will be crushed if they step out of line?

At the same time, since the Fire Nation is much smaller than the Earth Kingdom, the Fire Lord must ensure they can defend the Fire Nation from invasion; you need a large, devoted, competent military to go up against an enemy multiple times your size.

In order to further control the country, the Fire Lord requires the families of the lords and nobility to live in the closed-off, guarded capital inside the caldera in a similar manner as the Tokugawa Shogunate required. This is why the capital is so guarded and closed-off, yet beautiful and comfortable; it is both a defensive measure for the administrative officials and a means of holding the nobility “hostage”.

The Fire Lord and Royal Family views themselves as presiding over, and maintaining the peace and stability of the Fire Nation. Their responsibility is to ensure that the peaceful Fire Nation does not fall back into the chaotic Fire Islands. Being nice and democratic is not their means of achieving this; making sure everybody subordinates themselves to the Imperial Government is.

After hundreds of years of peace and an unprecedented era of prosperity, the Fire Nation began to lose its internal enemies. The lords and nobility were under full control. The Imperial Government was vast and efficient. Nobody was trying to invade the Fire Nation. Everyone was happy and proud of their culture and government.

This allowed Sozin to begin looking outward. Using the all-powerful Imperial Government apparatus developed over the centuries, plus the sweeping loyalty to it ingrained into the public, he was able to get the country to go to war against the world. The militarism inherent to the Fire Nation’s leadership was not crafted out of whole cloth but simply cranked up and sent down a dark path.

The military being so willing to go along with it was because of their inherent loyalty to the Imperial Government and their culture of aggression and lust for battle necessary for warriors. This is actually where the 20th century Imperial Japan connections come in, but that’s a separate topic.

In summary, the Fire Lord and Royal Family view themselves as stewards of the peace and order of the Fire Nation. They see their responsibility as doing whatever it takes to prevent the “bad old days” from returning and that the Fire Nation is never weakened by foreign invaders. They rule through coercion and fear in order to ensure a country full of people who can shoot fire out of their hands remain subservient to the Imperial Government’s will. They embrace a culture of fighting because their primary goal is to prevent fighting by deterring those who might want to try.

An Alternate View of the Fire Nation’s Villains

Viewing the Fire Nation’s culture, government and leadership through the lens of Japanese history paints a more coherent picture of the Fire Nation’s villains, versus the M.C. Escher-like theories that result from focusing entirely on mental illness and personality disorders.

Look at it like this: the Fire Lord demands fealty and obedience from the people yet Azula’s emphasis on controlling people through fear is a result of Freudian Excuses and personality disorders?

No way.

Ruling through fear and coercion is necessary from the viewpoint of a soldier-princess who is supposed to command obedience from subjects, or else.

Agni Kais are expected events in Fire Nation culture, so common that child-Zuko is perfectly happy to face the general over mere “disrespect”, but the Fire Lord challenging his son to one is uniquely out of line? It’s awful, I mean, really awful, but it’s not out of line and it says a lot about the ingrained culture of the Fire Nation; Ozai didn’t think it would be viewed as shameful by everyone watching. Keep in mind that the tale of the 47 Ronin started with one member of the nobility insulting the other (essentially) and being asked to commit suicide simply for drawing a weapon inside Edo Castle (strictly forbidden). If Ozai can have his power challenged as any other Fire Lord can, then nobody was willing to oppose him because everyone else supported him.

Iroh spends a lifetime invading the Earth Kingdom, no doubt killing tens of thousands, and he can joke about burning Ba Sing Se to the ground? Of course he can, because it’s what Fire Nation generals do and part of the terrible culture that must be changed, as horrible as it was. The prince-general is supposed to be a military leader and enjoy what he does. He better not be squeamish.

Zuko is expected to be “loved and adored” for having firebending talent, courtly manners (to quote official descriptions of Azula) and intelligence in a similar fashion as his prodigal, early-blooming sister? Yes, because she bloomed early as the type of princess the nobility and leadership want and expect. It’s unfortunate they were so hard on Zuko, but now we know why he wasn’t “adored” like his sister; she was what others wanted Zuko to be.

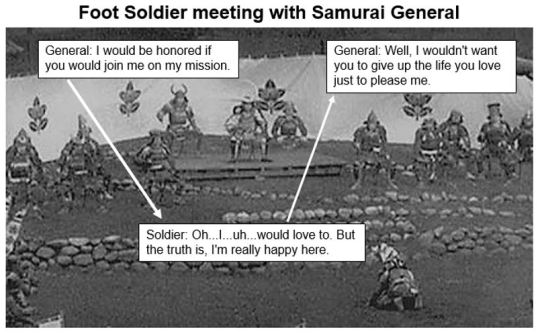

Ty Lee is strong-armed by Azula into leaving the life she loves, even having her life threatened, when Ty Lee is a family member of the nobility that the Imperial Government seeks to control? Of course she is strong-armed. Can you really imagine this scenario playing out:

Those lines are taken from the show. Sounds a lot different, doesn’t it? Ignore the smirking and smugness for a moment and think about what is actually happening: a supreme military leader and heir to the throne is bullying a subordinate in order to get what they are entitled to; unwavering loyalty from a subject. Doesn’t make it good. Doesn’t make Ty Lee’s fear and loathing of Azula any less justified, but it puts it in a much more relevant context than vague theories of sadism and personality disorders. It also tells us something about the real ancient world: this how military rulers in East Asia’s history behaved and now you’re getting to see it in a fictional setting.

Fire Lord Azulon orders one of his sons to execute their son? That’s bad. Really bad. Did you also know that Ieyasu Tokugawa ordered his own son to commit suicide over suspicion he was conspiring against him? He didn’t want to but those were the wishes of the lord he was working with to win the war. That’s really bad too, and not shocking for the era, unfortunately. The leaders of the ancient world valued human life a lot less than people do now. It’s sad they didn’t value it more.

Manipulating subordinates (i.e. playing them off each other) and being ruthless were not frowned upon, but legitimate tactics. Murder and backstabbing were useful means of getting rid of an opposing leader. What mattered was winning, and the blood on your hands could simply be washed off, and if people didn’t like you for it? Well, were they in charge?

None of this is “good”. None of this is moral, or righteous, or anything close to how people should act in the modern era. However, these were not kleptocratic dictators like we see around the world today. These were legitimate administrative rulers by their day’s standards, and we (you and me) will never truly know what they were feeling when they woke up in the morning with the responsibilities of warfare and politicking.

We will never be able to completely relate to what these ancient leaders did. Do you know what it’s like to be the law in the land who can order people to commit suicide, and who will do it? Do you know what it’s like to prosecute a political and military war against multiple opponents across a vast country? Do you know what it’s like to manage an ancient authoritarian government after hundreds of years of warfare and chaos? None of us will, but that’s the kind of situation that a fictional country like the Fire Nation can take inspiration from, and should take inspiration from.

These were all very real problems of the ancient world and problems which Avatar, as a fictional work, can allow us to explore in the safety and comfort of not actually having to be there (and without having to open up huge history books).

Summary

The Fire Nation’s political and military history can be modeled on ancient Japan’s, in particular the rise of the Tokugawa Shogunate, where the Fire Lord represents the shogun and the Fire Sages the emperor.

The Fire Nation capital is both the head of the administration and home to the nobility’s families, who are held as hostages (in comfort) to prevent the various lords from rebelling.

The Royal Family and Imperial Government rules through fear and threats of force because they have to keep a country full of walking flamethrowers in line.

As military leaders who can have their power challenged, firebending talent and military prowess are highly valued and necessary for Fire Lords. At the same time, the rest of the country’s leadership wants leaders who appear worthy of that power and authority, hence those who have all the right qualities (Azula) are viewed in higher regard than those who have less (Zuko).

Azula’s emphasis on using “fear to control people” is not a psychological hang-up but a natural tactic of the Fire Lord, military, and Imperial Government to maintain obedience; as a teenager with limited life experience, she has internalized her role as a princess and warrior to the detriment of her personal relationships and emotional maturity (this is where the “child soldier” narrative has relevance).

Ozai represents the pinnacle of self-interest, authoritarianism and militarism that the combination of Sozin’s War and the longstanding nature of the Imperial Government have combined to create. In the ancient world, lords waged warfare for two reasons: to acquire power or pre-emptively wipe out rivals. Ozai wants power.

Ozai challenging Zuko to an Agni Kai is awful but not unusual, hence why he felt he could do it at all. Agni Kais are a fundamental aspect of conflict resolution in the Fire Nation, most likely because the Fire Nation’s leadership values bravery and a willingness to fight very highly. As Zuko was a prince and future leader of the warrior class, those values applied to him as well, but they got applied to him far too young (again, this is where the “child soldier” narrative has relevance).

And finally, by modeling the motivations of the Fire Nation’s villains and heroes on the military leaders of ancient Japan, you have the opportunity to learn about and critique that ancient society while also giving it a fictional flare.

As a final remark on applying the history of ancient Japan to the Fire Nation, the Tokugawa Shogunate ended when the Emperor forcibly took control of the Tokugawa government in order to end the forced isolationism. If ancient Japan hadn’t been pressured to adapt to more advanced European civilizations (say, if it existed in a vacuum) then the Tokugawa Shogunate might have continued to be the longest and most stable period in Japanese history; post-World War 2 Japan is only 70 years old while the Tokugawa Shogunate lasted for 278. When the Emperor wrested control of the country from the Shogunate, there was already enough peace, stability and government bureaucracy in place to lead a rapid transition of the country into modernity. That was the ultimate value of the Tokugawa Shogunate.

If the Fire Islands had not unified under a central authority, then they might have never industrialized so rapidly during that “unprecedented time of peace and prosperity” and may have eventually been conquered by the Earth Kingdom (should an EK conqueror have found a way of killing the Avatar, or taking advantage of their absence).

Conclusion

Think about ancient Japan for a moment. All of the warring lords. The conquest and ruthless political maneuvering. The ruling through fear and totalitarian control. What is a more reasonable explanation for the behavior of that society: mental illness and personality disorders, or universal concepts of ancient nation-building?

What makes more sense for furthering Avatar’s East Asian themes in terms of the Fire Nation: sociopathy, personality disorders, lack of fundamental human qualities, petty bullies and insecure abusers? Or universal concepts of ancient nation-building in the context of people who can shoot fire out of their hands?

Was Ieyasu Tokugawa suffering from a personality disorder? Was ancient Japan swimming with people who lacked fundamental human traits? That would be and absolutely extraordinary anomaly of human genetic variation.

When discussing the evils of the Fire Nation, you have to start with the in-world context that created them, and in order to understand that context, you have to apply some East Asian history. Why “decent” or “normal” people end up doing terrible things is a question as old as humanity itself and should not be erased from Avatar.

In order to understand why Ozai and Azula seem like “bad” people to us, it’s because the rulers of ancient Japan acted like bad people. Zuko can’t be soft and fumbling. Azula can’t let people say no to her. Iroh can’t abandon the siege with no consequences. Ozai can’t let Zuko refuse to fight. As bad as many of these things are, they are driven by the fact these people are the most powerful entities in their country and must show their fire-wielding subordinates that they deserve their power and should not be challenged. There is no room for weakness, only strength and competence.

When you resort to psychological theories or genetic anomalies to explain the Fire Nation’s villains, you erase the opportunities to tie the Fire Nation to critical elements of East Asian history, namely the rise and success of the Tokugawa Shogunate. By relating the main villains of Avatar to the very real “villains” of the ancient world, you preserve the East Asian themes that make Avatar unique and informative to a Western audience and help shed light on what drove them to be what they were.

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

okay so i went through the datamined books from eso, taking notes as i went. @boethiah sent me a message this morning about it, asking what i thought. so i figured i might as well get real comprehensive about taking down notes to answer decently, or at least do it to organize my thoughts.

before she sent me that i hadn’t heard about this, so i went into it bright-faced and intrigued. i didn’t think my notes would end up too long, so i just figured i’d send them to her when i was done, even “talking” to her in the notes (you’ll see what i mean by that).

but uh. as all things lore-related, i got a bit carried away. stopped almost halfway thru to go to class, and by then i’d started to notice some really weird, kinda silly shit in it. and then i noticed everybody in tesblr talking about it, and finally realized, “oh. so it’s like that.” so i figure i’ll post it here publicly instead.

despite the uh. obvious nonsense in a lot of this, i think there’s a lot of interesting things hidden away. so what i’m going to do is just post my notes under the read-more. i’m too lazy to organize them into something more coherent lol. they’re basically just me commenting on certain lines and stuff.

i won’t like, really go into why most of this is stupid, bc other people have already done so, and better than i probably could’ve. but you’ll know. somethings i quote things and just. have no idea how to even address them other than, at best, “??????” either bc it doesn’t make much sense, eludes useful analysis, or is just stupid.

anyways, here goes:

book 1:

azura: - "the Path"? am i wrong or has a "Path" never been referenced in khajiiti lore?

khenarthi: - alkosh comforts khenarthi after lorkhaj died? yeah right. - khenarthi's role as psychopomp for azurah mirrors kyne's role for shor. but azura doesn't factor into nord/atmoran mythology at all.

jone and jode: - azurah cares for jone and jode? interesting. (also, "Bright Moons"? full moons?)

lorkhaj: - lorkhaj as "White Lion?" - namiira (the Great Darkness) followed lorkhaj as his burden? - mention of a "path" again, made by lorkhaj with purpose. sounds yokudan. - "in conflict with himself" & "represents the duality of the Khajiiti soul" ... desert and jungle ... strife, hardship, and life, love ... both tainted deadly by nirni, according to ahnissi - "We honor his sacrifice by walking the Path with purpose and resisting the call of the Dark." ... the Path again ... the Dark? namiira? - (the khajiit seem to conflate namira and nocturnal. this isn't a new concept, as they both genuinely do overlap in many ways, but an interesting one.) - "the true spirit of Lorkhaj will sometimes appear" ... "by Azurah" - nerevar/ine, "or Khenarthi" - hjalti, "or by his oldest name" - ...ysmir?

magrus: - all of this magrus stuff is new, to my knowledge. - the importance of him fleeing from "Boethra and Lorkhaj" probably excites you :P - "fell into the Moonshadow" ... "too full of fear to rule a sphere" ... "tore out his other eye" (odin parallel? a "failed" odin, maybe? unless seeing "out of one eye" is metaphorical) - "Varliance Gate"???? "Aether Prism"???? they're the sun, but those names are brand new afaik. overall a strange alternative to the story of magnus and the sun - "Some sorcerers hold that Magrus left the eye willingly" - more odin stuff

book 2:

- azurah knows all the names of all the spirits, their protonyms? that's interesting. a lot of that "protonymic" lore is derived from the whole "true names have power" stuff, popular in magical circles from sources like kabbalah thru the lens of crowley. - "And Fadomai told stories of her children and her favorite aspects of each of them. When she reached Azurah, she smiled and told her favored daughter she could not decide. And Fadomai died." ;----; - "sat in the Great Darkness for timeless ages" ... sat with namiira? - seems to have carved moonshadow from the great darkness. (the great darkness seems to have dual meaning as both oblivion and namiira. then again, i think only clan mother ahnissi said the great darkness was namiira, so that (morrowind) lore might be outdated.) - this scene with lorkhaj and his empty dark heart is......interesting. - "UR DRA NA MII RA UR DRA NA MII RA UR DRA AZU RA" - you can pick out "namiira" and "azura" in this, but the meaning of "UR" and "DRA" elude me. - lorkhaj gets his heart torn out YET AGAIN. very rude azurah - the "Moon Beast" and its hunger remind me of the yokudan sep. - i think once upon the time "dro-m'Athra" referred to daedra in general, but i think eso has made them a specific type of daedra resembling khajiit. even more specifically, some kind of "dark khajiit" born from dead evil khajiit. - "lighting the fire with lanterns of love and mercy" - your vivec is showing, azurah. or i guess, the other way around. - this "ashes of Lorkhaj" bit gets me thinking about ysmir, again. but i'm not sure what to do with that.

book 3

sheggorath: - now THIS is a not shitty interpretation of sheggorath! he's not a "god of madness," but a god of mental fortitude, a god who tests convinction. - more stuff about "the Path" - "must be ... overcome before a Khajiit can visit Hermorah's library"? - "Sheggorath is dead and has been replaced by something Other" - the hero of kvatch? but if this is from eso, that hasn't happened yet? unless the mantling of sheogorath is a pretty common occurrence; i remember someone on tumblr suggested that this might happen every era.

orkha: - "Orkha ... followed Boethra back through the Many Paths" ... what does that mean? - "Lorkhaj, Khenarthi, and Boethra battled the demon in the ancient songs" - ... as trinimac? - "but Orkha could only be banished and would not die" ;) - "serve as tests along the Path" - so far these princes are being painted similarly to their house of troubles counterparts

dagon (also called merrunz.) - no reference to merrunz being the kitty cat. :( next - ...okay not really. "explore the Great Darkness rather than the Many Paths"? - molagh "tortured him until the creation of the World?" but "the wife of Molagh freed Merrunz"? who is "the wife of Molagh"?

molagh (balls) - "twelve Demon Kings"? should probably look into how they got that number - "Boethra and Molagh fought to a standstill before the lattice, but it was Azurah who shackled the Demon King with secrets only she knows." - i dont have anything to say about this really, just an interesting line i think. - "you will overcome him with the might of Boethra, the Will Against Rule." - interesting...afaik, aside from HAVING a khajiit name, boethiah never really factored into their faith that much, and wasn't ever mentioned in clan mother ahnissi. i wonder if azurah at some point attempted to unify her plans for the dunmer and the khajiit.

merid-nunda - interestingly, the khajiit seem to call her by her magna-ge name. - "False Spirit of Greed"? - magrus "loved only himself and his own creations"? idk if this seems all that congruent with the magrus from his own description - "cold spirit, born of light without love" - interesting - "blame her for orchestrating the death of might Lorkhaj"??!?!?!? what?????????? - "When Merid-Nunda dared assault the Lattice, Azurah struck her down before the Varliance Gate and dragged her away from it. She then cast Merid-Nunda into the Void and bound her there with mirrors. The nomads say she has since escaped." this whole thing is interesting

book 4

nirni: - nothing interesting on nirni.

y'ffer: - y'ffer "corrupted by the Great Darkness," (namira), who apparently killed nirni???!??! what??????? - worth noting that ahnissi doesn’t paint y’ffer as “corrupted” or evil or anything. in her words he’s kinda just a moron who doesn’t *get it* and does his own thing instead. - don’t get the obsession with making namiira some like. crazy super evil being. feels like eso took a look at the list of princes and was like “who hasn’t tried to destroy/take over the world yet. that’s what daedric princes do right”

hircine - hircine doesn't get a funny ta'agra name, i guess. - graht-elk?

hermorah - hermorah helps azurah maintain the ja-kha'jay?

sangiin - according to what this says about sangiin, khajiit are actually NOT one of the most hedonistic races on tamriel. suuuuuuuuure, buddy.

book 5

- a look at the khajiit afterlife w/ azurah in moonshadow. - first you walk the sands, then you walk the glass, then you walk the thorns, then you have a good time, then azurah sends you back to nirn do something else (reincarnated)? but it might just be this one guy who goes off to do something ("Bring my children back"), he seems kinda special. no idea who he's supposed to be.

book 6

- all this shit about akha and alkosh and alkhan is bullshit. the fuck is akha even supposed to be? according to his name you'd assume an association with akatosh, but alkosh is akatosh, right?

akha: - this book says akha is the first cat. ahnissi says alkosh is the first cat. - "Pathfinder and the One Unmourned" - are we talking about akatosh or dagoth ur here. - "Many Paths"??? again?? what are they. knockoff walking ways? - "mated with the Winged Serpent of the East [akavir], the Dune Queen of the West [yokuda], and the Mother Mammoth of the North [atmora]. He then went to the South [pyandonea] and never returned." then alkosh shows up and says "yikes that akha guy was a little fucked huh?"

alkosh: - alkosh is "The Dragon King" and "Highmane." association with the Mane of the khajiit - "In time, the children of Akha overthrew [Alkosh] and scattered his body on the West Wind." ...??? is this a reference to the middle dawn? seems unlikely - apparently khenarthi put him back together. also seems unlikely

alkhan: - oh so the khajiit recognize alduin now too. cool.

boethra: - and boethiah i guess, why not????

mafala: - mafala has always been part of khajiit religion, tho, afaik. she is the og clan mother. - "She watches over Eight of the Many Paths, each of which a Khajiit must walk in time." ?????????? wtf are the many paths!!!!! why are there eight of them!!!!!! is this a reference to the spiral skein, or satellite realms (the spokes) of it? - forreal i think they gave up on pretense here when they started listing allies and shit. - "Her numbers are Eight and Sixteen, and these are two of her keys." this just sounds like something from the 36 lessons tbh. this doesn't sound like khajiit lore at all

book 7

lorkhaj (moon beast): - confusingly, lorkhaj as fadomai's favored son and lorkhaj as the moon beast are called by the same name, and despite this have separate entries in these books. - wonder if there's some equivalent in other myths to the moon beast. he seems pretty interesting, being "born of the dark heart of Lorkhaj" - there's UR DRA again, attached to namiira, again, who is apparently an enemy of the khajiit.

namiira: - apparently eso has rebranded namiira as like, an absolute enemy of the khajiit, with the dro-m'athra as her corrupted-khajiit minions or something? except i thought dro-m'athra originated from the moon beast? anyways, ahnissi only said that the great darkness became namiira. didn't say that was a bad thing necessarily. - also, her khajiiti ta'agra name, namiira, just so happens to be her protonym, NA MII RA.

noctra: - oh, so they do have nocturnal, as "noctra". - wait, so she's the "daughter of twilight"??? isn't twilight, idk, azura's thing???? (i feel like i've heard nocturnal be associated with twilight before, but it still makes little sense. it was probably from eso, too.) - boethra separated noctra from namiira. one could say she *stole* noctra from namiira ;) - noctra is ok by the khajiit, whereas her progenitor namiira is not. ok?

varmiina: - ok we have vaermina now too i guess. why the fuck not. - "The Lost Daughter. This spirit was not of any litter, but was born from Fadomai's fear of losing her children." - "Azurah killed this dark spirit in the Underworld" what the fuck is "the Underworld". they just be making shit up now

[?????] (no, really. that's what it says. dunno if that's a placeholder or intentional): - "[?????] A spirit of vengeance. It has no will of its own, as it was born from Azurah's grief after the death of Fadomai and Lorkhaj." ????? - "It sometimes appears in songs as a black panther, a warrior in ebony armor, or as a hidden sword." idk about "a black panther," but the "warrior in ebony armor" evokes ebonarm, who's technically still canon, and "a hidden sword" could be umbra. not sure what the connection here is.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Scratch an itch: A taxonomy of automation

We promised this post getting on for two years ago. In the meantime James has decamped to Paris and Julian has just completed a book on manifestos. Last week happened to find us both in Madeira, so we had a crack at devising a taxonomy of automation over our usual coffee and toast. The itch motif likely springs from the fact that it’s mosquito season.

As long ago as 1958, the philosopher Gilbert Simondon warned of the implications of automation, using developments in the motorcar to illustrate his argument. Simondon criticised the starter motor for overcomplicating the mechanical purity of the internal combustion engine. He preferred the simplicity of the manual turning handle: less to go wrong, easier to fix. Of course Simondon’s warnings, and many others in between (see challenge #3 of our manifesto), have been mostly ignored as we continue down the road of increasingly over-engineered standards of luxury, captured here in an observation from the environmentalist Bill McKibben:

At a certain point, says the philosopher Albert Borgmann, “Technology … mimics the great breakthroughs of the past, assuring us that it’s an imposition to have to open the garage door, walk behind a lawn mower, or wait twenty minutes for a frozen dinner to be ready.” Borgmann wrote that twenty years ago. Now the salesmen insist that it’s an imposition to have to press the button that opens the garage door when the smart ID chip embedded in your bicep can do it for you.

Simondon’s critique of the starter motor may now appear somewhat dated, as it is perhaps a bit of an imposition to crank a car into life each time you want to drive somewhere. However, such warnings, made when the automation of everyday life was in its infancy, become extremely poignant when you consider the ‘advances’ made in recent years - in particular the increasing complexity and non-fixability of contemporary technical systems.

Our taxonomy of automation, sketched hastily on the back of a coffee-stained napkin, charts the shift from Fordist-style production lines to more complex near-future scenarios in everyday life. We’ll start with our (adapted) definition of a robot to help clarify what we mean by automation:

For a thing to be considered ‘automated’ it should be able to sense and interpret in some fashion its environment, compute decisions based on that sensory information, and then act on those decisions in a physical way.

The basic assumption is that the combined automated operation satisfies some human need or desire: the sensing aspect realises the existence of the desire, computation figures out exactly what this is and how to address it, and the act is the physical intervention that satisfies the desire.

We’ll attempt to explore the taxonomy by describing various technologically progressive ways of satisfying the desire to scratch an itch ... please bear with us (starting with that terrible pun).

The Simondon scratch. You have an itch and the instantaneous desire to get rid of it - so you do it the old-fashioned way, using what is in your local environment (say, a tree trunk) without enlisting the aid of any automated system. This is clearly not part of the ‘official’ taxonomy, since there is no automation in the process. Like the cranking of the engine, the desire is fulfilled by direct human action. The downside is that it takes more effort and a certain amount of skill. The upside is that the human has almost full control over the system.

The Fordist scratch. Or to use the industry term, semi-automation. You feel the itch and guide your scratching machine to the correct place, where it satisfies the desire in a collaborative manner. In this case the sensing aspect is non-existent. Desire is experienced by the human, who then sets the automated process into motion with the physical button. This taxonomic category largely has its origins in the push-button future kitchens of the 1950s, where everything the family desired was available though the simple push of a button.

Modern, and slightly disappointing, versions of this stage include the Amazon Dash - a person, realising the lack of a particular (desired) product, presses the appropriate Dash button. This engages an already-in-place physical infrastructure that follows a predictable path to satisfy the original desire.

For the purposes of this discussion we’re focusing on domestic notions of automation. There has been much debate over the pros and cons of Fordism in manufacturing, for example: reduction of hard or repetitive labour, cheaper products vs. fewer jobs, deskilling of the workforce, and the standardisation of products in both a positive and negative sense. The advantages and disadvantages in the context of everyday life are in some ways related: domestic automation does reduce human labour (going to the shop), but the reduction of choice that arises as a consequence of production lines (any colour so long as it’s black) is also felt by those using a service such as Amazon Dash. Consumers are locked into: (1) product lines that Amazon have negotiated a contract with, and (2) products for which they have bought a Dash button.

Simondon, again in the critique of technical systems, described automatism as ‘a rather low degree of technical perfection’ due to the number of possibilities of operation and usage that need to be sacrificed. The more open nature of semi-automation can provide a counter to this argument, but not in the form described by Dash - the key element that needs to be considered (from the experiential perspective) is in the balance and malleability of the collaboration.

Here is one of our favourite examples, in which the system replaces the human act of throwing a ball. This very basic automated system benefits equally all elements: the robot would be pointless without the dog; the dogness of the dog is enhanced by the function of the robot; and the dog’s owner, the one being replaced by the machine, enjoys both relief from the effort of throwing the ball and pleasure from the continuing spectacle. (For some reason this video never gets boring.)

youtube

The smart scratch. In this scenario, always-on sensors are scanning for an itch. For example a thermal imaging camera could detect a hot-spot from a mosquito bite (extremely common in Madeira) and guide the scratching machine to the appropriate place.

This stage represents an important shift in the process, as the recognition and interpretation of human desire becomes integrated into the automated system through the action of sensors. These sensors operate in real time and make fairly basic assumptions, like a basic if/then statement - for example, [if] a presence sensor in a smart fridge detects a low level of eggs [then] it computes the decision to order another box. The rest of the process happens as in the previous stage. The effort, on the part of those implementing the automation, is to minimise the timeframe between the occurrence of the desire and its satisfaction.

The category was explored in detail in one of our very first posts, smart futures = crap futures. One contemporary example is the Amazon Dash Replenishment Service (DRS), which orders products automatically, without the push of a button. The [then] command reduces possibility in exactly the way Simondon discussed, as the system is essentially closed. It enforces repetition, standardisation and efficiency - which, in an era that increasingly appreciates and even fetishises ‘slow food’, is exactly not what a person with fluency and flair in the kitchen desires.

This category suffers the same problems as the utopian promises made in the last century, and why so many future visions fail. They are driven by either technological dreams or engineered notions of progress, such as efficiency. They ignore the complex and messy reality of human activity and desire. Smart systems also raise the key question: What desires can realistically be sensed, and how open is the reading of that sensing for misinterpretation (a point we explored in our careless whispers post).

The scratch before the itch. The system predicts the itch. Perhaps you’ve experienced it before, at predictable intervals in predictable places, or the prediction is based on data relating to the behaviour of individuals with similar profiles, as well as the fact that it happens to be mosquito season where you live.

Or, to continue the parallel example of the fridge, the system might anticipate that you’ll need avocados on Saturday - because you normally make a lot of avocado toast, or whatever. Or it might check your calendar and see that you’re having friends over and you’ll need a box of cheap wine and Doritos for entertaining, or conversely that you’re going to be out of town and therefore won’t need anything. It might order the ingredients of your favourite dinner party menu and hangover breakfast, or ‘propose’ fun activities like baking a cake. (The elaborate possibilities of a truly smart fridge paired with a busy social life are intricate enough to require a separate post - in fact we’ve been working on such an idea called Elvis’s Fridge.) This stage brings to mind Amazon Go, the cashierless stores first introduced in 2016. Amazon removes human interaction - the type of recommendations that you might get from a local grocer or butcher, the foundation of local communities - and delegates instead to the algorithm.

The tickle that makes the itch. The system over-automates, presuming to know you better than you know yourself. Or the system becomes manipulative - perhaps even creating the itch in the first place. There is an obvious loss of control at this stage, with complex decisions being made on your behalf. Desires are being triggered through direct appeals to your reptile brain. Services like Amazon Go are venturing into this territory, raising issues of privacy and the extent to which consumers are being forcibly assimilated (or very strongly nudged) into systems using biometric data and other new technologies. The tipping point is retaining human agency versus being governed by the system. Some people recoil at this loss of control, while others embrace it. Why not let a machine make all the decisions for you?

It seems to us that the optimum point of automation is where a machine does the drudgery and human agency and control are still given priority. Simondon compares this preferable state to an orchestra, where machines are the musicians and the human being is the conductor. They work together in harmony: the machines play a crucial role, but the human ultimately serves in the role of interpreter and decision maker - ‘inventor and coordinator’. As the stages of automation progress, this starts to shift: the automated system increasingly influences and intrudes on the terrain of desire.

Freud wrote about the pleasure principle (id) versus the reality principle (ego), the latter involving the delayed gratification that comes with adulthood. Higher level automation combined with late capitalism invites us to override our adult selves, exchanging self-control for the childish expectation of instant gratification in all aspects of daily life. (Think of Amazon Prime Now’s guaranteed one-hour delivery, and the extreme time pressure that means employees can’t even stop to perform essential bodily functions.) The fear of complacency and passivity has long been associated with technology, from Brave New World to WALL-E. Of course it depends where you live: in Madeira, for example, an Amazon delivery still takes weeks to arrive.

Resistance to algorithmic control is popping up everywhere, including some unexpected places. The Rage Against the Algorithm colloquium, held this month in Prague on the anniversary of the Velvet Revolution, is one example. The event, hosted at Charles University, featured speakers such as Nick Srnicek (Accelerationism), Helen Hester (Xenofeminism), and Louis Armand (Alienism), all in some sense responding to the challenges, threats, and opportunities presented by automation and other ‘advances’. Over in America, meanwhile, there is the long brewing backlash in Silicon Valley against algorithmic control, with a rise in no-tech homes and schools. Things have flipped in the past decade, so that poorer schools increasingly rely on devices like iPads while more economically advantaged schools are going tech-free, back to basics, Waldorf curriculum, and so on. In his essay ‘Why I am Not Going to Buy a Computer (1987), Wendell Berry anticipates this shift with the simple observation: ‘If the use of a computer is a new idea, then a newer idea is not to use one.’

Increased automation touches on a number of important themes, some of which we’ve discussed before: narrowing pathways, loss of agency, deskilling, automation of habits and desires, loss of identity and self, alienation from natural processes. In Mythologies (1957), Barthes laments the way that mechanical toys (unlike wooden ones) encourage a passive role:

faced with this world of faithful and complicated objects, the child can only identify himself as owner, as user, never as creator; he does not invent the world, he uses it: there are, prepared for him, actions without adventure, without wonder, without joy.

People want more pleasure with less work - that is the promise of automation. But how much pleasure can we take? And how much do we enjoy endless pleasure, which is often not even pleasure, but mere convenience? What is pleasure without resistance, or a bit of pain? To return to the example of the itch, if we could anticipate and remove the itch forever - never have to scratch again - would we? Or would we miss that strange animal pleasure? Scratching an itch releases the hormone serotonin, which we could obtain artificially, without causing any negative effects But would it be as sweet?

In his great novel of tyrannical automation and technological control, Player Piano (1952), Kurt Vonnegut paints a vision of America as ‘one stupendous Rube Goldberg machine’. Assuming at this point we cannot stop it completely - or wouldn’t want to - how can we escape the worst effects of this vast and hidden, pervasive and all knowing machine?

Images:

Coffee and toast (photo: Julian Hanna); Baloo in Disney’s The Jungle Book (1967); Amazon Dash buttons (2015-); a wood shop in Santo da Serra, Madeira, Portugal (photo: Julian Hanna); a tin mechanical toy (CC0).

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Twin Peaks & Hauntology

A large deal of David Lynch’s content is surreal not just because of how odd it is, but also because of how familiar it is: For many entering the Twin Peaks universe in contemporary times, they have already been exposed to some imagery from the show or from David Lynch’s other work, which often makes many parallels to the show itself. For instance, prior to starting the original run of the series, I had indeed seen the classic portrait of Laura Palmer a myriad of times and knew the famous lines, “who killed Laura Palmer?” I had seen some of Lynch’s work too, and I also had in fact seen plenty of references to Twin Peaks in pop culture, but it was only when I began to immerse myself in Twin Peaks that I could say to myself, “this feels like deja vu.” The cinematography, the color palette, the dated film quality, the eerie music, everything about the show is setup so that it feels haunted, both from within its own universe and for those observing as though external spectators. Essentially, one of the main reasons why Twin Peaks is such a successful show in terms of endearment and also producing chilling reactions, is because it plays to humanity’s fragmented memories of time, rejecting a linear framework in favor of something that is more distinctly postmodern (i.e. time is not treated as a straight arrow as is the case for most shows). David Lynch innately flirts with these concepts throughout his career in philosophical and psychological manners that make many uneasy from various standpoints, including the metaphysical and ontological. One tiny yet distinctive and slowly emerging school of thought to grow out of the postmodern field of study is hauntology, coined by the French philosopher esteemed for his take on deconstructionism, Jacques Derrida, in his 1993 book, “Specters of Marx.” All things considered, Twin Peaks is an excellent example of hauntology expressed through an artistic medium, and here is some elaboration as to how and why.

So what is hauntology? Derrida originally developed the idea as a portmanteau of haunting and ontology, ontology being the study of life, hence “hauntology.” Specifically, his aforementioned book from 1993 extensively developed Karl Marx’s idea that “A specter is haunting Europe – the specter of Communism.” These were the opening lines to “The Communist Manifesto,” published in 1848 and yet managing to have widespread appeal on a major political levels, well over a hundred years after it had been written and even to this day, proving that Marx was right – Communism is haunting Europe and the rest of the world, chiefly due to the fact that it exists in opposition to the dominant mode of production around the globe, capitalism, but also because according to many scholars, we are perhaps living in a late stage of capitalism that is in fact quite similar to what Marx and his contemporaries envisioned, a stage of decay and corruption that gives way to a fork in the road of fascism, corporatism, and the like, but could also bring forth major developments in class consciousness with regards to revolution and unification. By treating Communism as a specter, it is essentially a faceless character, looming and lurking in the shadows, a ghostly apparition that either instills terror or hope into the hearts of those who find it depending on what side of the political spectrum they are on. Derrida also ties this idea into the Shakespearean play, “Hamlet,” which also began its first lines (“Who’s there?”) in a haunted sort of manner, involving an actual ghost. With regards to Hamlet, Derrida specifically makes note of how “the time is out of joint,” a similar occurrence to real world matters such as Communism and fictional matters such as Twin Peaks.

As Andrew Gallix of The Guardian describes hauntology, it is: The situation of temporal, historical, and ontological disjunction in which the apparent presence of being is replaced by an absent or deferred non-origin, represented by “the figure of the ghost as that which is neither present, nor absent, neither dead nor alive.” Peter Bruse and Andrew Scott further elaborate that: “Ghosts arrive from the past and appear in the present. However, the ghost cannot be properly said to belong to the past. Does then the ‘historical’ person who is identified with the ghost properly belong to the present? Surely not, as the idea of a return from death fractures all traditional conceptions of temporality. The temporality to which the ghost is subject is therefore paradoxical, at once they ‘return’ and make their apparitional debut.” From here, we note how Derrida’s own writing focuses on the presumed “death” of Communism in the post-Soviet world, the question of “the end of history” and most significantly, “if Communism was always spectral, what does it mean to say it is now dead?” All of these concepts tie into the lost futures of modernity, and as Wikipedia writes in depth: “Hauntology has been described as a ‘pining for a future that never arrived;’ […] hauntological art and culture is typified by a critical foregrounding of the historical and metaphysical disjunctions of contemporary capitalist culture as well as a ‘refusal to give up on the desire for the future.’ [Mark] Fisher and others have drawn attention to the shift into post-Fordist economies in the late 1970s, which Fisher argues has ‘gradually and systematically deprived artists of the resources necessary to produce the new.’ Hauntology has been used as a critical lens in various forms of media and theory, including music, political theory, architecture, Afrofuturism, and psychoanalysis.”

Now, regarding hauntology more as an artistic statement and genre than as something philosophical is the first way we can approach Twin Peaks. The style is unique yet also not: It is, as expressed by one of the most prominent artists of the style, Boards of Canada, “the past inside the present.” Most notably, hauntological art is expressed in music, paying homage to library music, vintage documentary-film scores, public information films, etc. This means a heavy dosage of old-school synthesizers, blips and bloops, samples of dialogue from long forgotten movies, and so forth. What we have on our hands here, is “21st-century musicians exploring similar ideas related to temporal disjunction, retrofuturism, memory, the malleability of recording media, and esoteric cultural sources from the past. Artists associated with hauntology include members of the UK label Ghost Box (such as Belbury Poly, The Focus Group, and the Advisory Circle), London dubstep producer Burial, electronic musicians such as the Caretaker, William Basinski, Philip Jeck, Aseptic Void, Moon Wiring Club, and Mordant Music, American lo-fi artist Ariel Pink, and the artists of the Italian Occult Psychedelia scene. Common reference points include library music, the soundtracks of old science-fiction and pulp horror films, found sounds, analog electronic music, musique concrète, dub, decaying cassette tapes, English psychedelia, and 1970s public television programs. A common element is the foregrounding of the recording surface noise, including the crackle and hiss of vinyl and tape, calling attention to the medium itself.”

Furthermore, “’hauntological music has been particularly tied to British culture, and has been described as an attempt to evoke ‘a nostalgia for a future that never came to pass, with a vision of a strange, alternate Britain, constituted from the reorder refuse of the postwar period.’ Reynolds described it as an attempt to construct a ‘lost utopianism’ rooted in visions of a benevolent post-welfare state. According to Fisher, 21st-century electronic music is the anachronistic product of an ‘after the future’ age in which ‘electronic music had succumbed to its own inertia and retrospection … What defined this 'hauntological' confluence more than anything else was its confrontation with a cultural impasse: the failure of the future….’ He explains that this is partly the result of stagnated technical advances since the 20th-century. The style has been described as the British cousin of America's hypnagogic pop music scene, which has also been discussed as engaging with notions of nostalgia and memory. The two styles have been likened to ‘sonic fictions or intentional forgeries, creating half-baked memories of things that never were—approximating the imprecise nature of memory itself.’ Early progenitors of the style include Boards of Canada and Position Normal.”

Lengthy quotes aside, the basic message is that hauntological art – particularly music – is dreamlike, vaguely nostalgic, and ghostly. Basically, musical deja vu. One could make a case that popular genres like chillwave and synthwave, which rely heavily on ‘80s aesthetics are also hauntological, but they lack the same sense of “dread” and “fragmentation” that established artists like Boards of Canada have (e.g. Boards of Canada’s last album, “Tomorrow’s Harvest” is directly linked to the themes of war, apocalypse, the end of history, civilization’s collapse, death and rebirth). The Caretaker, too, is another fantastic example of hauntology: Leyland Kirby publishes records dealing with themes of dementia (the absolution of memory loss) and much of his work is lo-fi, darkly reverberated jazz from no later than WWII; essentially, it is as though history did end with the second war, and when listening to The Caretaker, we are hearing ghostly apparitions committed to tape. “An Empty Bliss Beyond This World,” “Everywhere at the End of Time,” the titles of Kirby’s work alone is enough to suggest something hauntological is occurring. Kirby’s music becomes directly relevant to Twin Peaks: The Return when the viewer notes how similar the music and pre-1940s style are to The Caretaker in The Giant’s realm (some have even dubbed The Giant as a cosmic caretaker of sorts ironically enough). But in the meantime, it is important to discuss how this all relates to the original run of Twin Peaks. One may pose the question: “How is hauntology related to Twin Peaks?”