#if they are willing to kill him for literally delivering their cure whose to say wouldn’t have gatekept it anyway!! the fireflies were crazy

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

above all, i really do like abby i feel bad for her but i DO hate her dad<3

#ari.txt#killing a suicidal 14 year old not even waking her up to give her a CHOICE to the surgery???#not even letting her say goodbye to the man who protected her and bonded with her for the past YEAR?#now HES a piece of shit more than joel abby and ellie combined#i also feel like ppl forget they were gonna kill joel after he was abt to leave the hospital#if they are willing to kill him for literally delivering their cure whose to say wouldn’t have gatekept it anyway!! the fireflies were crazy

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

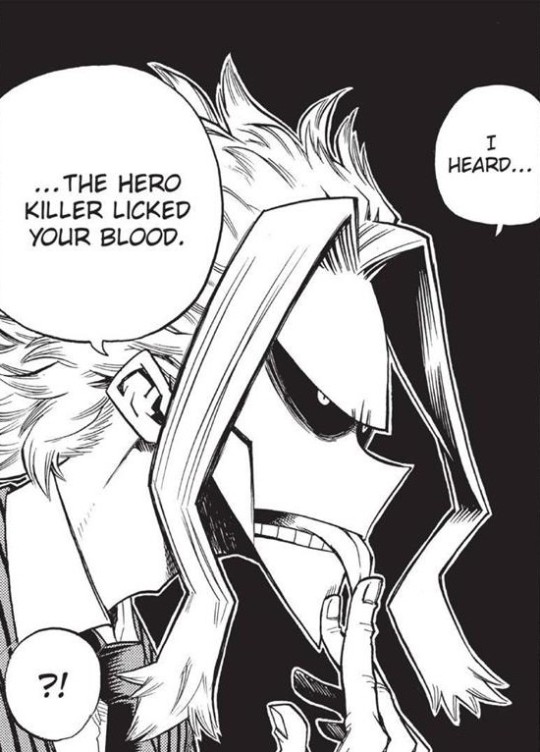

BnHA Chapter 059: The Origin of One for All

Previously on BnHA: Deku said farewell to Gran and headed back to U.A. Bakugou’s Jeanist hair was featured in just one panel, but forever left its impact on me and henceforth I will observe a moment of silence for Bakugou’s dignity each year on the anniversary of this day. The kids discussed their internships. Iida, Deku, and Todoroki received extra attention due to the whole Hero Killer thing. All Might conducted some training. Deku showed off his new skills. All Might asked Deku to visit him after class SO THAT HE CAN FINALLY TELL HIM ALL OF HIS SECRETS AND EVERYTHING ABOUT HIS PAST AND ABOUT ONE FOR ALL. OH MY GOD SOMEONE HOLD ME, HOW I HAVE WAITED FOR THIS DAY.

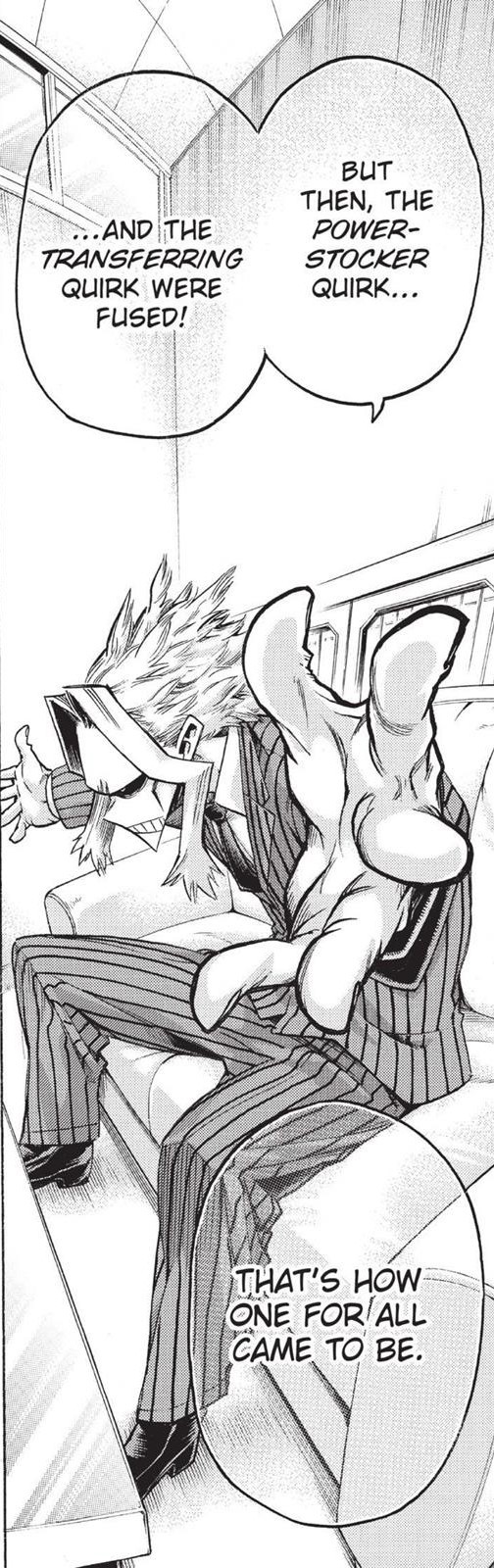

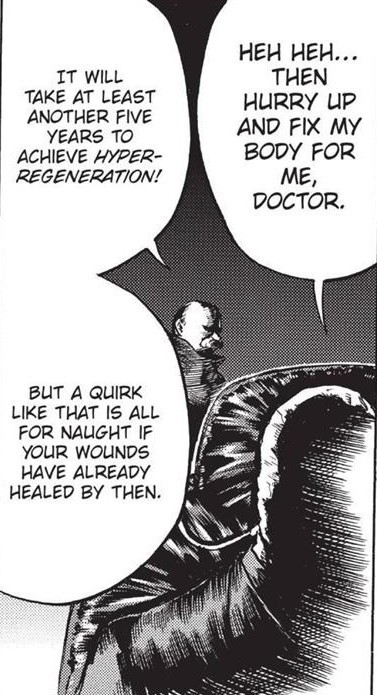

Today on BnHA: Mineta gets some comeuppance. Deku chats with All Might. All Might reveals the origins of All for One, a man whose quirk allows him to steal other quirks as well as grant them to others. We learn that One for All came to exist when this same man transferred a quirk to his brother which mutated and allowed his brother to pass on that power from generation to generation. All Might warns Deku that he might have to face All for One someday. Deku says he’ll be fine as long as All Might’s by his side. (: Aizawa announces a summer trip to a forest training camp. All for One’s face is finally revealed (!!).

(As always, all comments not marked with an ETA are my unspoiled reactions from my first readthrough of this chapter. I’ve read up through chapter 132 now, so any ETAs will reflect that.

**There are manga spoilers in this post for BnHA chapter 131, which has not yet aired in the anime.** These spoilers are marked, but it’s the first time this has come up, so please take heed. If anyone has any feedback regarding ways to possibly do this better, I’m definitely open to it!)

something about that number 59 that I really love... can’t quite put my finger on it :)

(ETA: present me is feeling less playfully cryptic than past me, and realizes that not everyone reading a BnHA recap is going to have detailed knowledge of the KHR fandom and all of its weird idiosyncrasies, which include, among other things, a system in which each character has a corresponding number. so just to be clear, 59 is a reference to this asshole, a.k.a. my favorite character now and always. and I could, in fact, actually put my finger on it, and if there ever comes a day when I don’t associate that number with him, it’ll be safe to assume that I am either an impostor or dead.)

anyways I have skyhigh fucking expectations for this chapter now, so let’s hope it can deliver!

JIROU PROFILE!

imagine being able to fuck up someone’s internal organs with the sound of your own heartbeat

six meters is nothing to laugh at; that’s some pretty decent range there. and she seems to have full control over the jacks’ movements the entire time

so I read Jirou as a lesbian, and I’m curious what everyone else’s thoughts are. yay? nay?

and I mentioned this a while ago, but I’ve shipped her and Momo since like chapter 16, and I still ship it lol

on to the chapter!

the kids of class A are changing back into their normal uniforms after All Might’s training session. Deku is wondering what All Might wants to talk to him about, and he’s a little nervous

Mineta is calling Deku over and saying he’s made a discovery. Mineta how dare you pollute my chapter 59 with your garbage presence

yep it’s exactly what I thought it was. little shit found a peephole leading to the girl’s locker room on the other side

Iida’s telling him to stop, but he’s not doing nearly enough

omg

I feel like this should have some kind of trigger warning. in fact, I was originally going to post the closeup of the earphone jack stabbing right into his eye, but then I was like, you know what, let’s just err on the side of caution

have I mentioned how much I fucking love Jirou omgg. only regret is that she didn’t take out both his eyes

OH MY GOD SHE’S USING HER QUIRK TO FUCK UP HIS EYE EVEN MORE

“YOU REAP WHAT YOU SOW” YESSSSSSSSSSSS. THAT’S MY CHAPTER 59!!!!!

NOW DEKU IS IN ALL MIGHT’S BREAK ROOM. OH MY GOD IT’S HAPPENING

OH MY GOD

RIGHT??!?!

All Might says he’s sorry he wasn’t by Deku’s side. “you’ve been through a lot”

omgggggggg

-- OH FUCKING SHIT

OH SHIT OH SHIT I JUST REALIZED

“do you remember what I said when I granted you this power?” omg. DNA. oh my god oh my god

THANK FUCKING GOD?!?! WHY WOULD YOU DO THAT TO ME, CHRIST

jesus. okay so he says One for All won’t transfer to a new recipient unless the user wills it to

so it can’t be taken by force, but he does interestingly point out that it can be passed on to someone else without their consent. which is true, and something I hadn’t considered! if you got someone to unknowingly take in some of your DNA (or hell, it doesn’t even have to be unknowingly, does it. can you also transfer One for All through makeouts or sexy times?? omg), you could pass the ability to them without their knowledge. or even against someone’s will. though I have no idea why anyone would ever want to do that

(ETA: actually, it’s since occurred to me that there is at least one scenario where someone might be forced to do that, and that’s to prevent the quirk from falling into All for One’s hands once again. and now I really want a plot line in which Deku is forced to do this. talk about the ultimate sacrifice play. I don’t necessarily see it happening in the series -- although it would be amazing!! -- but my god I would read the shit out of that fanfic. just so long as it has a happy ending in which Deku escapes and One for All is restored back to him, though. oh man. now I’m thinking about this wayyyy too much hahaha.)

he says One for All comes from another quirk!

ALL FOR ONE?!

-- it ROBS others of their quirks omg

okay so obviously All for One must have this quirk. and I mean, it’s the perfect villain quirk. it ties into what’s been going on with the Noumus. and most importantly, it’s the antithesis of All Might’s own (former) quirk. One for All vs. All for One. literally doesn’t get more balanced than that

exactly like with the Noumus

calling it right fucking now, someone Deku knows is going to have their quirk stolen

imagine if it was Bakugou. and all of a sudden he was rendered quirkless. the thing he despises the most. omg. I think I mentioned in a previous post that I know we’re gonna get some Baku angst at some point, and now that I know this is fucking possible, holy shit. it really could happen, maybe. omg

(ETA: lol get ready for all my speculation from the Forest Training Camp arc up until basically the end of the Hideout Raid arc to be tinted by this lens. I fucking spooked myself a bit there.)

okay so apparently this all started back when quirks were just becoming a thing. so we’re talking a ways back. and I guess that makes sense, given that Deku is supposedly the ninth-gen user of One for All

so basically when quirks first came onto the scene, it was like X-Men. everything was in upheaval, people were scared of people with quirks, and basically no one knew what to do and society went nuts

but some guy came along and “brought the people together”

wow the dude fucking took over the entire country of Japan. I would fucking hope Deku had heard of this guy, then?

he has heard of it, but only through “rumors”, and he thought it was all made up. apparently they kept this incident out of the textbooks. so this guy’s influence must be extraordinary even now

now All Might’s explaining how One for All came about from all of this!

just like fucking Noumu omg

that’s what I just said, Deku. geez. fine I’ll be quiet

so All Might says that in some cases when people were granted quirks, their quirks mutated and blended together

omg

holy shit

so he had a quirk that did nothing except allow itself to be passed down to someone else. but then for some unknown reason, Big Bad gives him a crazy powerful new quirk, and that new quirk merges with the passing-down quirk

can I just quickly say, I love that the brothers’ original quirks were so closely related, since it makes sense what with them being blood related

All Might says justice is always born from evil. that’s a good line, dammit

Deku’s asking so then how can that original guy from all those years ago still be around. I’m guessing he must have stolen some sort of immortality quirk

and All Might theorizes the same

holy shit. so the brother kept opposing him but couldn’t beat him, so he ended up passing his quirk on to the next generation, and the cycle kept repeating itself again and again

(ETA: I couldn’t think of where else to put this, but I just wanted to mention that since One for All works by stockpiling power -- meaning its power increases with every subsequent generation -- this means that Deku is destined to become even stronger than All Might, and that’s so damn exciting.)

what?! that’s all the detail you’re going to go into about this part??

so anyways, this is why he hadn’t told Deku about this yet. because of the whole “you’re destined to have to face this guy yourself one day, maybe” thing. wow

he’s more Dumbledore than I originally thought

but Deku is pretty damn Gryffindor

oh my god ;_;

the fact that he said “as long as you’re with me...”

and now All Might is looking so fucking anguished all of a sudden

oh my god don’t be dying. please don’t be dying All Might

oh god

oh my god. don’t tell me it’s what I thought earlier. that once you give up One for All that’s it and you’re doomed. please don’t let that be the case. if it comes to him thinking he’s going to die, I’d rather it be from the injury. like, something about how modern medicine can only do so much. because at least then there’s hope that someone will come along with some miracle cure quirk or something, maybe. but if his own quirk is killing him, then there probably isn’t anything that can be done, and I don’t know if I can handle that after the bond that these two have formed!! I don’t care if it’s thematically perfect!!

(ETA: ***SPOILER WARNING FOR CHAPTER 131***)

*

*

*

*

*

okay so! this has finally been explained and of course, it’s perfect. the idea of a prophecy is something I didn’t see coming, but once Nighteye’s quirk was established, it made a whole lot of sense. and yet somehow if you can believe it, I still didn’t see it coming lol.

but I like this a lot! because it works as both something that feels inevitable, and something that the characters are determined to fight nonetheless. and it adds an ominous clock-ticking-down feel to everything that’s going to come after this point. although I’ve only read one chapter since then, lol, so I don’t actually have any idea where this is going to head just yet.

but anyway, I’m just happy it was finally addressed, and that Deku’s reaction was as angsty as I could have hoped for, and that All Might’s subsequent response was more perfect than I could have ever dared to dream, and have I mentioned to you guys how much I love Toshinori and Deku’s relationship because oh my god. I love it so damn much.

*

*

*

*

*

(END SPOILERS)

ALL OF A SUDDEN WE’RE CUTTING BACK TO CLASS A. FINE. GOOD. LET’S PUT THESE FEELS ON HOLD FOR NOW

Aizawa says summer break is approaching. I feel like this is a good time to pause for a sec and take stock of who is still fifteen and who is sixteen, because I realized the other day that Bakugou’s April birthday means he’s among the oldest in the class (ETA: in fact he is the oldest), and already turned sixteen before the sports festival

okay, so Aoyama, Hagakure, Satou, and Kaminari have already had their birthdays for sure, and Deku, Iida, Sero, and Mina either also just turned sixteen or they’re going to shortly, because they all have birthdays in the back half of July, and the Japanese summer break is usually in August

interestingly (well it is to me), Todoroki is actually one of the youngest kids in 1-A; his birthday’s not till January. the only younger ones are Kouda, Tsuyu, and Shouji of all people (Shouji you sure are a big guy aincha)

okay now back to your regularly scheduled programming

oooh Aizawa says they’re going to a summer break forest lodge!! yessss omg. this immediately sounds amazing

lol these kids have seriously misinterpreted what kind of trip this is going to be. what fucking school do you all think you’re attending here

yeeees this is my favorite thing, not even gonna pretend. I wonder just how many fanfics are set during this arc hahaha

Aizawa says that if any of them fail the end of term exam, they’ll be stuck in school, and I guess that means they miss out. YOU’D ALL BETTER PASS THEN. EXCEPT MINETA -- YOU CAN GO TO HELL

aww, poor Deku is still sitting there completely distracted by his conversation with Dumbledore -- I mean All Might -- earlier

he really didn’t. and I’ll try not to let any associations with Dumbledore cloud my fondness for that bravest and most selfless and noble of men, the Symbol of Motherfucking Peace, who just doesn’t want to dump all of this on Deku just now, and wants to let him be able to enjoy school and being a kid for as long as he can like normal

and I mean, similarities aside, All Might never pulled any shit like dumping Deku in an abusive household for eleven years, or basically raising him for slaughter and keeping mum about a prophecy that said he had to die

so yeah. All Might, you’re good

my god this has been a good chapter 59

oh my god we’re cutting to THE OTHER END OF THE SKYPE CHAT OH MY GOD. HOLD ME I CAN’T BREATHE

WHERE’S YOUR HEAD OH MY GOD I CAN’T TAKE IT?!

he’s chatting with some mad scientist-looking guy

so he has that same regeneration quirk that the Noumu had, but he received it after All Might wounded him. actually, his fight with All Might was supposed to have taken place five years prior to the start of the series (so six years ago), right? so that would mean he only just got the regeneration power recently

OH SHIT!!!!!

YESSSSSSSSSSS

OH MY GOD HE’S PERFECT. EXACTLY AS CREEPY AND THREATENING AS HE NEEDS TO BE. THE LACK OF EYES REALLY HELPS. WHAT WITH THEM BEING THE WINDOW TO THE SOUL, IT’S ONLY FITTING THAT THIS GUY DOESN’T HAVE ANY

SERIOUSLY, IT IMMEDIATELY MAKES HIM THAT MUCH MORE THREATENING IN MY BRAIN, JUST, LIKE, INSTINCTIVELY. LIKE A SLENDERMAN VIBE ALMOST

and he says All Might should enjoy this “transient peace” while he still can

holy fucking shit

I’m so fucking hyped omg. like this dude absolutely can be the final villain for the next 140 or 240 or 540 chapters, however long it takes to tell the rest of this story. he’s got it. All for One. so fucking perfect holy shit

#bnha#boku no hero academia#makeste reads bnha#jirou kyouka#midoriya izuku#all might#all for one#bnha manga spoilers#someone please tell me why all for one is always sitting there watching these monitor screens though#I don't care if he has infrared vision or not#how is that going to help with those#is it just for the aesthetic or what

66 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Jonestown We Don’t Know

This past November marked forty years since Jonestown, shorthand for the collective suicide of more than 900 Americans in a South American jungle settlement named for the pastor who led them there, Jim Jones. As the greatest loss of American life in a single incident before September 11, 2001, it deserves a significant place in our historical memory. The commemorations, however, have unfortunately tended to focus on the aberrant behavior of Jones, who sometimes claimed to be God and sometimes a reincarnation of Lenin and sometimes the Buddha reborn.

Jones preached in a prophetic evangelical style, while wearing sunglasses, from his People’s Temple pulpit, as the church migrated from Indianapolis to California’s Redwood Valley to San Francisco’s Fillmore District. His dark glasses allowed him to steal surreptitious glances at cheat sheets bearing intel on his congregants as he staged sensational healings; in a performance with many reprises, Jones would pass off raw chicken liver as a tumor shed by a cancer patient spontaneously cured during his service. Many of the books and films produced about the tragedy bear his image, as if he were posthumously still promoting the personality worship he cultivated among his followers, who called him Dad or Father. He stands at the deranged center of these accounts, which linger on the grisly details of the deaths and on Jones’s charlatanism, his infidelity, his use and abuse of drugs and corporal punishment, his childhood obsessions with funerals and Adolf Hitler.

The “Cult of Death,” as Newsweek and Time Magazine dubbed Jonestown in cover stories illustrated with images of flocked corpses decaying in the tropical sun, came to its macabre conclusion in 1978 in the fledgling postcolonial republic of Guyana, where I was born. I was living there, in a coastal village some 250 miles away from the settlement, when the Americans killed themselves. I was only three. Within a decade, my family and I would ourselves be Americans. Like many other Guyanese, we fled the country’s economic and political mayhem for the United States. Growing up outside New York City in the 1980s, it was hard to escape the infamy of Jonestown. Often, when I revealed my birthplace, the response would be some riff on: “Don’t drink the Kool-Aid, right?” As an immigrant kid, I did not much enjoy being placed on a map of associations with a seemingly inscrutable and eerie spectacle of death. I bristled at the implication that Jonestown had anything to do with Guyana or the Guyanese.

In this, I had something in common with Guyana’s ruling elite. Eager to disavow responsibility, they depicted their country as merely the incidental backdrop to the tragedy. It was as if, in the words of a Guyanese government statement cited by journalist Jeff Guinn for his 2017 book The Road to Jonestown, “a Hollywood movie team had come here to shoot a picture on some aspect of American life. The actors were American, the plot was American. Guyana was the stage, and the world was the audience.”

An aura of contingency continues to surround Jonestown, so often portrayed as the tale of a lone madman, a charismatic crackpot who imploded in a random heart of darkness. In truth, as I have come to learn, Jonestown does not point to a singular erratic Svengali but, rather, to fundamental aspects of both my adopted and my home countries. About 70 percent of the community’s 914 dead were African Americans, whose precarious place in the country of their birth made them responsive to pitches to leave it. Their individual stories have been lost in the commemorations, an erasure that also obscures the systemic character of what unfolded. America in the 1970s was still so warped by the legacies of slavery that it inspired the followers of Jim Jones to dream elsewhere, and Guyana’s politics at the time made it fertile ground for their dreaming.

Jones, the estranged son of a Ku Klux Klan member from small-town Indiana, had built a robust black following in Indianapolis through a ministry focused on social justice; by taking his parishioners into the pews of white churches and into whites-only restaurants in the 1950s, he also emerged as a leading force for integration in the city. He and his wife were the first white couple to adopt an African-American child in Indiana. But even as the political establishment there and, later, in the Bay Area wooed him for his influence with African-American voters, critics noted that his trusted inner circle, who made up the temple’s leadership, was predominantly white.

Fewer than ninety of the nearly 1,000 People’s Temple members present in Guyana during the suicide ritual escaped it. Most did so because they were in Georgetown, the country’s capital, rather than in the rainforest settlement with Jones when he ordered everyone to kill themselves. These survivors, broadly defined, belonged to Jonestown’s white elite stationed in Georgetown as emissaries to the Guyanese government or were members of the settlement’s basketball team, including Jones’s faithful bodyguards and his sons, who happened to be in the capital to play a game against the Guyanese national team. Others who emerged alive had defected from the settlement earlier that day under the protection of California Congressman Leo Ryan, who had visited to investigate charges that people were being held there against their will. Ryan’s visit ended in a dramatic armed attack by Jones’s enforcers at a nearby airstrip that claimed five lives (including Ryan’s) and precipitated Jones’s decision to activate his long-plotted suicide plan.

In the wings of this great drama were the unseen. Hidden in the rainforest where the violence was staged, in the eerie aftermath of the tragedy, were three people whose stories cue political contexts in both the US and Guyana crucial to understanding how and why Jonestown may have happened.

Literally unseen that fateful night, to her great good fortune, was Hyacinth Thrash, a seventy-six-year-old African-American woman born in the Jim Crow South who had crossed decades and distances with the preacher, from Indiana in 1957 to Guyana in 1978. On the night of the suicides, she did not respond to the loudspeaker summons to the settlement’s central pavilion where her sister Zipporah, along with the rest, would either drink or be injected with a lethal purple brew of Flavor Aid, cyanide, and tranquilizers. Thrash, who used a cane, wasn’t feeling up to the walk. That night, unaware of what was unfolding, she stayed in bed. For an unknown stretch of time, perturbed by noises outside, she crawled beneath her bed. She was either hidden under it or camouflaged in sleep, with the covers pulled over her, when Jones’s deputies came through the senior citizen dormitories delivering the poison to those too frail or weary to make it to the final ceremony. The next morning, she awoke to stillness and the epiphany that she was the apparent sole survivor, “The Onliest One Alive,” as the self-published book that relates her story—a little-known oral history collected and edited by a white Presbyterian church elder in Indiana—is titled. Thrash, it turned out, was one of four people actually at the settlement that final night, in the physical thrall of Jim Jones, who did not die. All four were black.

Yet, of the many books about Jonestown published by People’s Temple attorneys, defectors, survivors, members, or their relatives, in no case was the author an African American. There have been more than seventy-five published accounts of Jonestown—by People’s Temple insiders as well as US reporters, several canonical West Indian novelists, a Caribbean historian, a medic sent to the scene, a San Francisco radical poet, a ghostwriter for televangelists, and a child safety expert (a third of the dead were children). The “survivor” accounts were written by white people, although most of the dead and all of the survivors were black. Indeed, the historiography around Jonestown would seem to confirm Thrash’s observation about her education in a small town along the railroad tracks in segregated Alabama. “Books,” she said, “were cast-offs from the white school. Stories was all about white children. History was all white.”

Some narratives have explored what Jonestown says about America’s dysfunctional approach to race. A few have also noted that Jones misappropriated Black Panther co-founder Huey P. Newton’s concept of “revolutionary suicide,” which called for targets of racist violence at the hands of the state to be willing to lay down their lives in the fight against it. It’s hard to say how aware or free Jones’s followers were when they killed themselves; several survivors have argued it was more murder than suicide. Jones drugged his followers, controlled some through manipulative and transgressive sex, blackmailed others with damaging confessions signed under duress, demoralized many and destroyed family bonds––but he also reinforced their distrust of the US government. For his elderly African-American congregants, their lives had certainly given them ample evidence of state-sponsored racial persecution.

Thrash’s own encounter with institutional racism began with her childhood in rural Alabama. In her small town, whites attended school nine months a year; for blacks, it was only four. Nor could her parents, an illiterate domestic worker and a small-time farmer who supplemented his income as a cook on the railways, exercise the vote. Surrounding “sundown” towns barred blacks with, effectively, a curfew. Thrash’s family believed that her grandfather had been killed for violating such an ordinance. When they moved north as part of the Great Migration—though only as far as Indiana, a stronghold of the Klan—the discrimination took other forms. The department store where she worked as an elevator operator paid its black employees less than whites. She and her sister bought their own house in a section of Indianapolis vacated by white flight, and their white neighbors spurned them, going inside whenever the sisters sat on their porch. Thrash observed: “Sometimes I think whites didn’t want to come close to us ’cause they’d find out we weren’t so bad.”

It was Jones’s promise to heal such wounds and rejections that first attracted Thrash and her sister Zipporah to him. The Bible had so suffused their upbringing that they played at baptizing chickens as children, and Zipporah bore the name of the wife of Moses, who led the Israelites out of bondage. Zipporah never did become anyone’s wife, but when she first saw Jones preaching on television, she was smitten by his good looks and by his integrated choir. In The Onliest One Alive, Zipporah emerges as a true believer to the last, rushing into the cottage where her sister rested, obliviously, to change into a special red sweater before responding to Jones’s call to death.

As for Thrash, she had once believed that Jones cured her of cancer and had the charisma to reunite her with her ex-husband; but her account, published in 1995, bristles with skepticism at all levels about Jones. She wonders if he was less like Moses than a demagogue accusing others of racism to mask his own prejudice and “making fools of black folks,” especially the gullible and the propertied. (Over the years, Jones took $150,000 in tithes, houses, and Social Security checks from the sisters.) In the oral history, Thrash criticizes him for betraying his wife and the Bible (the settlement, for instance, scandalized her by using a shipment of Gideon Bibles as toilet paper). Instead of praising God, she says, his sermons morphed into “ranting and raving about the FBI and the CIA coming to get us.” As early as his ministry in Indiana, he had warned his parishioners of threats to kill them. In a landscape dominated by the Klan, this was not far-fetched, just as it was perhaps not far-fetched, in the long arc of lives marred by discrimination, to buy Jones’s final prophesy: that after Congressman Ryan’s murder, US government forces would soon descend on Jonestown to destroy it, and it would be far nobler for his followers to take their own lives before that happened.

But Thrash’s testimony—the only instance of an African-American survivor speaking in her own words to posterity—suggests a growing cognitive dissonance about Jones among his followers. “When Jim started acting up, I had double feelings,” she admits. “Sometimes, I thought I’d never get out, sometimes I did. I was ready to walk through the jungles to escape; then I’d get resigned to dying there.” She went so far as to devise a getaway plan: on a trip to the capital to see the dentist, she would defect to the US Embassy. Jones’s paranoia, cruelty, and hypocrisy had disillusioned many, she reports: “Got so folks said they’d just as soon take their chances with the enemy. Folks were getting more scared of Jim than the enemy.” She heartbreakingly recounts that, toward the end, he had the elderly residents (one third of Jonestown’s population was senior citizens) arm themselves with picks and shovels and stand guard. “’[C]ause the US army was coming to get us! Huh!” she tells the church elder in The Onliest One Alive. “The US wasn’t even thinking of us! They didn’t even know who we were or where we were.” Even as she doubts Jones, her sense of being unnoticed by the powers-that-be in the country of her birth is visceral, sharp.

*

Unseen, too, was Kalinyas, a chief of the Caribs, the indigenous group that has long lived in the high-canopied tropical rainforests in Guyana’s far northwest, edging its border with Venezuela, where Jonestown’s settlers built their farming cooperative on 3,000 acres of ancestral Carib land leased exceedingly cheaply from the Guyanese government. “(F)or the short season they were here, I saw them without being seen,” Kalinyas told his grand-nephew, the writer and intellectual Jan Carew. “I was there the afternoon death surprised them, just as the sun was going down. They chanted and clapped hands for a while, and then there was a terrible silence. With candle flies in bottles to light the way, I walked amongst their dead. They’d died in circles, like worshippers around invisible altars.”

The Carib chief complained to the writer that “they [the Yankees] wrote so many words about Jonestown, but they wrote about themselves. For them, we were invisible.” Carew, perhaps best known for his novel Black Midas, was a BBC broadcaster in London and a professor of African-American Studies in the United States. He relayed his great-uncle’s grievance in an essay that appeared in another self-published account, the 2016 anthology A New Look at Jonestown: Dimensions from a Guyanese Perspective. Guyanese perspectives are usually missing from Jonestown narratives, a gap that obscures its place in histories of colonization.

As Carew walked, many years after the incident, with his elder relative, through the wreckage of what had been Jonestown, the old man recounted singing Carib death-songs among the suicide victims. The elder explained that he was calling on the homeless spirits of the Americans to reconcile with the ancestral Carib dead, because they had never asked for permission to share the land. Jonestown was built in the Kaituma region, heartland of the Caribs, who had dispersed to various islands from their historical homeland in Guyana over centuries. Named after the river running through it, Kaituma means Land of the Everlasting Dreamers. Traversing the ground there that Jonestown occupied, the writer and the Carib chief found it still littered with the abandoned shoes of the dead, overgrown with wild flowers and bromeliads. A sapling had lifted a child’s patent leather shoe off the ground like “strange fruit that some rare and exotic plant had produced.” Carew reflected that if anyone understood mass suicides, it was the Caribs, whose mythology marks sites across the Caribbean islands where they jumped from cliffs to their deaths rather than accept slavery at the hands of European colonizers.

Jim Jones had nurtured in his followers a paranoia framed by fears of a standoff with reactionaries and a sense of themselves as martyrs persecuted for their faith, anchored less by orthodox Christianity than by declarations of socialism and interracial brotherhood. But apart from their self-annihilating fate, how does their story echo the struggles around colonization? The answer is twofold. For Pan-Africanists in the twentieth century, the fight for civil rights in the United States was intertwined with battles for independence across the colonized world, from Africa to Asia to the Americas; as they imagined it, blacks constituted a colonized people within the United States as well.

That raises another aspect to what unfolded that often goes untold. Jonestown was one in a history of ventures—beginning with the American Colonization Society in the early nineteenth century—that explored and pursued futures for African Americans outside US borders, for various political reasons. What became Liberia, for instance, was formed in 1822 as a West African colony in a slavery-era scheme to resettle free American blacks elsewhere, out of the way. During the same period, in 1840, “free colored” congregations in Baltimore dispatched two envoys to Trinidad and Guyana, then still British Guiana, to determine which was the better Mecca for their lives and labors. The delegates recommended Guiana, describing it as a paradise with its best land lying fallow, simply awaiting enterprising workers. “[L]et us imagine,” the envoys reported, “a large and extensive country, with the most luxuriant soil, capable of producing everything that grows in a tropical region.” They advertised, if not the utopia suggested by the name Land of Everlasting Dreamers, then certainly a land of plenty.

More than a century later, Jones would claim to have seen in Guyana both natural abundance and an invitation to reimagine society. Before stamping the People’s Temple acres there with his own name, for years previously, during which the mission to grow subsistence crops in a self-sustaining socialist commune was an idea without a location, Jones had called it the Promised Land. He borrowed this name directly from the farm that his role model, Father Divine, the son of a slave, had established in upstate New York in the 1930s to feed his communes housed in hotels. Jones had sought out and cultivated Divine, a prominent, flamboyant, and unorthodox religious leader whose Peace Mission was celebrated by some as an idealistic social reform movement and denounced by others as an ascetic cult.

Exodus motifs course through African-American religion and history, and both Jones and Father Divine tapped into them to market their visions. Every exodus needs a promised land. And it helps if the officials overseeing that land are invested in peopling it. For Baltimore’s “free colored” in 1840, that official was a British colonial governor anxious to provide sugar and coffee planters with field laborers, two years after slavery ended in the British empire. In the case of Jonestown, in the 1970s Guyana’s prime minister, Forbes Burnham, was promoting agricultural cooperatives as a way to develop his country’s vast interior. He pitched his country, the only black-led nation in the Western hemisphere with a non-black majority, as a refuge for African Americans.

Jones made that pitch, too, sometimes crudely. He contended with unruly teenagers by punishing them with beatings and solitary confinement in a black box or by encouraging them with the promise of supremacy. As Hyacinth Thrash recalled, “He’d say, ‘This is Black Town. You might be Prime Minister some day.’ The boys was all tickled to hear that.”

Also watching on Jonestown’s final night, but hidden in the jungle some thirty miles northwest, where he was farming and breeding parakeets, was Abdullah Abdur-Razzaq, formerly Malcolm X’s right-hand man at the Organization of Afro-American Unity in the last year of the assassinated leader’s life. Disillusioned with the United States, heartbroken, and afraid that he was being watched after Malcolm X’s killing, Abdur-Razzaq had been living in Guyana’s remote hinterlands for two years when the Jonestown suicides occurred. He did not wish to be seen. The government surveillance that Jones trained his followers to suspect was a fact of life for Abdur-Razzaq and several other Black Power figures, targets of the FBI’s COINTELPRO program, who found a haven in Guyana during the 1970s. When Abdur-Razzaq spied planes carrying US officials and soldiers descending from the sky in the tragedy’s aftermath, “he was so isolated,” his son told me, “that he thought the US government was swooping down on him.” In fact, Abdur-Razzaq was so fearful that he disappeared from his farm and hid in the bush for an extended period of time.

Abdur-Razzaq went to Guyana as part of an agricultural mission started by the Brooklyn-based black nationalist community group and arts organization The East, which scouted out Guyana’s northwestern rainforest at the same time the People’s Temple did. With black nationalists deriding Jones as a “white savior” who cynically exploited the anxieties and woes of African Americans, the two groups didn’t have much interaction. Yet they brokered the same deal, as part of the same government program, with Guyanese politicians. In 1975, in The East newsletter Black News, a pioneer at the group’s Kaituma cooperative described a daily regimen for working and living there that mirrored Jonestown’s, including rules against leaving without permission and nightly classes on Guyanese history. The East’s leader, in a pitch to recruit more Brooklynites to “return to the soil,” explained that the group “wanted to live and progress outside the US’s influences and tentacles.”

Abdur-Razzaq, who lived in Guyana for a total of more than twelve years, had wanted to take his family with him, but his wife objected. In cassette-tape dispatches he mailed home, he compared himself to the ancient Spartans who sallied forth into battle but ultimately returned home. His wife would argue with the tape recorder. The Spartans, she would say, got new families where they did battle. She unspooled and destroyed his missives.

So few of the accounts of Jonestown have bothered to examine searchingly why it happened where it did. Overwhelmingly, the books and movies fail to acknowledge the fundamentally intertwined relationship of the United States with this tiny republic in its sphere of influence. This entwining is such that a Guyanese national song usurps Woody Guthrie’s “This Land is Your Land,” swapping “the Redwood Forest” for “the greenheart forest”—as some 1,000 People’s Temple members, in fact, did when they moved from California’s Redwood Valley into the dense mass of Guyana’s famously impenetrable greenheart trees. The entanglement is built into the very structure of the relationship: Guyana’s independence was midwifed by covert CIA agents and American labor union emissaries, who placed Forbes Burnham in power.

Burnham was a leader unique in the Caribbean for beckoning, not banning, Black Power exiles. Other politicians in the region, who feared the potentially dissident influence of Black Power on their electorates, governed in societies with black majorities. By contrast, more Guyanese were of Asian-Indian than African origin, and their voting proceeded along ethnic lines; Burnham, who was black, had rigged elections to maintain power. Given his nation’s volatile, frequently violent ethnic politics and his own insecure hold, Burnham found it useful to make appeals based on race. He also wanted to change his country’s demographics and understood the role that migration might play. An Indian-Guyanese exodus to America alongside a black exodus from America would help his cause. When Jonestown’s chroniclers speak of Guyana’s interests in welcoming Jones and his followers, they repeat the government line that it was geopolitically strategic to settle 1,000 Americans along the disputed border with Venezuela, as a buffer against attack. Another, largely unexamined piece of the puzzle was that the Guyanese government had been successfully courting African-American settlers, through offers of jobs, political asylum, and cheap land, for nearly a decade when the suicides occurred.

*

Jim Jones Jr., the preacher’s black adopted son, recently spoke at a screening of Stanley Nelson’s Jonestown documentary at the New York Public Library’s Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, where I am currently a fellow. An audience member asked how Guyana, as a country of black and brown people, could be duped by a crazy white savior like Jim Jones Sr. The film’s editor insisted that the Guyanese government couldn’t be held responsible for the holocaust. Invited to draw lessons from the tragedy, Jones Jr. asserted that his father’s demagoguery was alive in the presidency of Donald Trump. It was, however, a different, chance encounter at the Schomburg that best captured for me how Jonestown still echoes in the present.

A stranger, an African-American man in his fifties who introduced himself as Mr. Tinsley, overheard me tell a librarian that I was doing research on Guyana. His ears pricked up because he was, too, in advance of his first trip there in a dozen years. He told me that he owned 478 acres in an isolated swath of the country that had been home for two centuries to a downriver penal settlement and for two billion years to a majestic tabletop mountain that had incited the imaginations of both Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (inspiring his 1912 novel The Lost World) and Sir Walter Raleigh (who searched for the mythological city of gold there).

Mr. Tinsley, an unemployed former limo driver born and raised in Harlem, said he bought the land for $10 in 2005, soon after his father died. That’s when he lost the property on Frederick Douglass Boulevard where his family had lived and run a construction company for decades. Gentrified out of his inheritance, he fixed his gaze instead on the distant horizon of Guyana. A Jonestown survivor who was a family friend had made him aware of the country. “From what he told me, what was down there (could) show people what this place could do for the world,” Mr. Tinsley whispered, as if sharing a potentially lucrative secret that he shouldn’t. “They’ve got so much natural resources.”

“Guyana is still really an untapped world,” he pronounced, adding that its natives had squandered its plenty and needed guidance. In his first venture there, as a rice farmer, he had found his Guyanese rivals “couldn’t get their acts together” or transcend their pride and squabbling. I found it hard to picture the paunchy, life-long city-dweller reaping paddy. The rice farm had been a failure. Next time, he planned to grow fruits and vegetables for export, but Guyana signified more to him than a business opportunity. He suffered from kidney disease, and he saw the country’s interior as an exotic oasis with the power to heal. Had I not seen the film The Medicine Man, which casts Sean Connery as a scientist hunting for a cure to cancer in the Amazon?

I was astonished by the lofty hopes he had projected onto the very place that my own family had, after all, fled. Guyana’s landscape, especially its vast, undeveloped interior, has long invited fantasies of riches and peopling, from Raleigh’s conquistador visions of it as “El Dorado,” or the realm of gold, to an abortive proposal to resettle Jewish refugees there during World War II. It also had a specific hold on the African-American imagination that seems still to live. Mr. Tinsley’s tale draws on a black radical tradition of investing Guyana with the glittery allure of an imagined homeland, a tradition that Jim Jones Sr. exploited to build his promised land gone horribly awry.

Photographs:

The Evans family, who survived the Jonestown massacre by walking out of the camp on the morning of November 18, saying they were going on a family picnic, United States, November 30, 1978

Cards and pictures found at Jonestown made by children of members of the People’s Temple, Guyana, November 22, 1978

Coffins awaiting shipment to the US after the Jonestown mass suicide, Georgetown, Guyana, November 23, 1978

#nyr daily#the new york review of books#1978#jim jones#jonestown#jonestown massacre#guyana#guyanese#kool-aid#kool aid#ku klux klan#kkk#indiana#white savior#white saviors#religion#suicide ritual#suicide rituals#leo ryan#people's temple#huey p. newton#huey p newton#revolutionary suicide#long reads#colonization#colonialism#the onliest one alive#black midas#a new look at jonestown: dimensions from a guyanese perspective#caribs

0 notes

Text

Don’t you just love how HP fanfic AUs where someone catches the Dursleys abusing Harry are more likely to have Vernon be the main abuser rather than Petunia? Vernon who, canonically, 1) knows nothing about wizards beyond what his wife has told him and 2) is afraid of said wife? Like, isn’t it so great how we automatically assume that Vernon is both the instigator and greatest perpetrator of most of the abuse?

In-book, Vernon is definitely very loud and verbal with his disapproval, desperately attempting to bellow out any abnormality he finds himself confronted with. He yells at people at work, he yells at Harry whenever he says anything that makes him uncomfortable, certainly. We also see him being the one to order Harry into his cupboard in book one. But if I recall correctly-- and I can’t be certain, because it’s been several years since I read through the books-- Petunia is the one who takes swings at him with her frying pan.

I guess... I’m mostly just really tired of looking for good fics where I get to see the results of the Dursley’s abuse on Dudley, and finding a whole ton of “Petunia wants to get Harry away from Vernon’s abuse” stories. Like, can we please take some time and acknowledge, as a fandom of reasonable, thinking, non-sexist people that the Dursley’s decision to “Stamp [the magic] out” of Harry was at best a mutual decision and even then, instigated if not entirely then very nearly so by Petunia’s own opinion and the way she depicted the wizarding world to her husband? Stop making her out to be the one who would get Harry out for his own sake just because she’s a woman. If you read the scene in the first book in the chapter “The Keeper of the Keys” in which Vernon and Petunia are arguing against Harry learning about his magic and going to Hogwarts, you’ll note that Petunia’s argument is very personally motivated while Vernon’s is based more on monetary concerns, second-hand ideas and fear.

Vernon:

(Hagrid about to tell Harry he’s a Wizard)

“STOP! I FORBID YOU!” yelled Uncle Vernon in a panic.

...

Uncle Vernon, still ashen-faced but looking very angry, moved into the firelight.

“He’s not going,” he said.... “We swore when we took him in we’d put a stop to that rubbish... swore we’d stamp it out of him! Wizard indeed!”

...

“Load of old tosh,” said Uncle Vernon... he was glaring at Hagrid and his fists were clenched.

“Now you listen here, boy,” he snarled, “I accept there’s something strange about you, probably nothing a good beating wouldn’t have cured -- and as for all this about your parents, well, they were weirdos, no denying it, and the world’s better off without them in my opinion -- asked for all they got, getting mixed up with these wizarding types -- just what I expected, always knew they’d come to a sticky end--”

...

“Haven’t I told you he’s not going?... He’s going to Stonewall High and he’ll be grateful for it. I’ve read those letters and he needs all sorts of rubbish -- spell books and wands and --”

...

“I AM NOT PAYING FOR SOME CRACKPOT OLD FOOL TO TEACH HIM MAGIC TRICKS!”

Vernon has no idea how the wizarding world works. He thinks it’s all a load of nonsense, but nothing so real or structured as an entire world hidden away with its own economy and laws and society. His speech seems to indicate he understands it to be some kind of occult thing-- “getting mixed up with these wizarding types” like someone gets mixed up with the wrong kind of alleyway scam artist-- and he’s afraid of something that might occur should Harry be informed of his inheritance, but we can’t really be certain what.

(also as a side note, do whatever you want in fanfiction regarding the extent of Harry’s abuse, but “ there’s something strange about you, probably nothing a good beating wouldn’t have cured” seems to imply pretty clearly that Vernon, at least, has never given Harry “a good beating,” whatever that means. It doesn’t put aside probable casual smacks, but it does pretty well settle the idea of a sadistically motivated curb-stomping.)

Petunia:

“Knew!” shrieked Aunt Petunia suddenly. “Knew! Of course we knew! How could you not be, my dratted sister being what she was? Oh, she got a letter just like that and disappeared off to that-- that school-- and came home every vacation with her pockets full of frog spawn, turning teacups into rats. I was the only one who saw her for what she was -- a freak! But for my mother and father, oh no, it was Lily this and Lily that, they were proud of having a witch in the family!”

She stopped to draw a deep breath and then went ranting on. It seemed she had been wanting to say all this for years.

“Then she met that Potter at school and they left and got married and had you, and of course I knew you’d be just the same, just as strange, just as -- as -- abnormal-- and then, if you please, she went and got herself blown up and we got landed with you!”

Petunia knows about the wizarding world, at least to some extent. Frog spawn? canonical potion ingredient. Turning teacups into rats? actual transfiguration assignment. Petunia is personally motivated and vindictive about it. She was the only one who knew, the only one who saw the world as the truth of it must have been, and Lily’s death should have proved her completely right about everything-- look at that, those freaks are so mad they can’t even stop from killing each other for no reason, she should have known it would end badly for her being a freak like that-- but then she got dumped with her sister’s kid and she has been personally offended by that for ten years. She hates this. She hates Harry. She hates Lily. She hates the situation. She hates magic.

*sigh.*

I can’t make people think critically about things, either canon works or fan works. I can’t make people put serious thought into their own fan works. I just... I wish I could find a better reason in the canon for people to assume that Vernon is Harry’s main abuser. I wish I could find something, anything, that tells me clearly that Vernon has more likely to be the one delivering beatings, and punishing Harry for minor infractions, and leaving AU-Petunia to divorce him or leave him or otherwise run away with Harry in tow, anything at all beyond the fact that he is the man of the house. I have not read a single work along that plotline that has given Vernon a reason of his own to despise Harry; they just kind of assume that he does, even when Petunia is willing to accept him, because reasons. Except that it’s not even because reasons because no reasons are ever discussed. Whatsoever.

I just... I would love a change of pace. A fic that acknowledges the motivations behind Harry’s treatment by the Dursleys. A story where Vernon leaves instead of Petunia, because sure, he has very little experience with childcare-- Petunia was always the one at home, he’s usually at work-- but however much she hates her sister, it just doesn’t sit right with him seeing a boy Dudley’s age that small and quiet. A story where Vernon is a decent enough fellow, if rather loud and somewhat close-minded, who is willing to consider that doing this won’t fix his nephew, won’t make the weirdness go away, and his wife is just doing this to hurt him because she can’t hurt Lily anymore, and maybe he should change something about this.

Just once... let a woman who is an abuser not get overshadowed by the less severe actions of her male partner and go excused just because he’s male and she’s female. As far as we can see in canon, Vernon’s abuse of Harry is mostly verbal, with some imposed neglect and isolation. Petunia is the one who actively hurts him and forces him to do things: assigning him to do all the chores and yardwork, making him do the cooking, taking a swing at him with the frying pan (I really don’t think I’m misremembering that since it’s playing in my mind in Jim Dale’s voice but also I have no idea where it is in the series and I only have books 1, 3, and 7 with me in my dorm 2000 mi away from my parents’ house where the rest of my books are)

But who am I kidding. This is the same fandom that took a man with an unhealthy obsession with a woman to the point that he was willing to sacrifice her husband and firstborn child so that he could see her live and turned him into a tragic and noble hero, sacrificing his own desire to help children for the sake of looking evil enough to qualify for Voldemort’s evil squad. The same fandom that took a character canonically acknowledged as flawed but well-intentioned, a character who made mistakes and regretted them as mistakes, who was motivated by a desire to see a boy live a happy life before what he saw as an inevitable sacrifice, who acknowledged that he ought to have behaved differently and apologized for it, into a manipulative bastard who intentionally screwed a kid over because he believed the kid needed to grow stronger. The same fandom who took a boy who was willing to ride or die from the very beginning for his best friend, who sacrificed himself very literally in a game of chess when he was eleven and stood on broken bones to put himself between said friend and a madman when he was thirteen and turned him into a whiny brat whose only purpose in befriending Harry was to leech off his fame.

I don’t know why I still expect critical thinking to fall into this fandom’s skillset.

#harry potter#fanfiction#harry potter fanfiction#fanfiction meta#fandom culture#i'm just so tired of it guys#please acknowledge that women can be abusers too#please acknowledge that the worse of two abusive parents might not be the man#please acknowledge this#I'm just so fucking done with this fandom sometimes#it's the greatest dichotomy I've seen in a fandom anywhere except Naruto#and even then#Naruto's fandom is almost too widespread to reach this level of dichotomy#there are too many developed characters in Naruto for opinions to polarize so drastically on so many key players#the harry potter fandom is hell#we've got both the best and the worst it seems sometimes#but mostly#i've found myself in a position where I almost exclusively see the worst#can anyone recommend something to remind me that this fandom has good points too#please#i know the good exists i just can't see enough of it to balance out the hair-rending idiocy

1 note

·

View note

Text

When You Are in Danger: Verse Behind the Christian T-Shirt

Most of us don’t see much danger. We move from climate-controlled homes, to air conditioned offices by moving at cheetah speeds inside extraordinarily safe vehicles. When we get sick, we get cures for diseases that have killed millions in the past. We have medications that can alleviate chronic conditions and extend our lives beyond what most people in history had ever dreamed.

But there is still some danger. Our careful planning still can’t stop natural disasters from destroying belongings and taking lives. Modern medicine still can’t put off death forever, despite our best efforts. Sophisticated security systems still can’t prevent evil people from hurting us. Danger is still here.

When You Are in Danger: Psalm 91

So where should a Christian turn to encourage us when we’re in danger? Our Bible Emergency Numbers Christian t-shirt points us to Psalm 91. The psalm was made famous (besides being in the Bible) by the song On Eagle’s Wings, composed by Michael Joncas.

Psalm 91 is a psalm that shows amazing trust in God. LIke many of these psalms, it encourages Christians to see our God as a shelter, a fortress:

He who dwells in the shelter of the Most High will abide in the shadow of the Almighty. I will say to the Lord, “My refuge and my fortress, my God, in whom I trust.”

The whole psalm describes how God protects the people who call on his name. The Psalmist lists several dangers that people in his day might face, pestilence, darkness, arrows, and armies. He writes that God covers his people with his wings to protect them like a bird covers its young. God promises to protect his people.

The Psalmist summarizes his message when God speaks in the last few verses:

“Because he holds fast to me in love, I will deliver him; I will protect him, because he knows my name. When he calls to me, I will answer him; I will be with him in trouble; I will rescue him and honor him. With long life I will satisfy him and show him my salvation.”

God promises to protect the people who call on his name.

But Christians Get Hurt All The Time…

Psalm 91 raises an obvious question, “How can these promises be true when Christians get hurt all the time?” One possible answer is that these Christians just don’t have enough faith. Here’s how the argument usually goes: If you believe enough, if you trust hard enough, if your faith is strong enough, then God will protect you.

It makes sense from a human perspective, too. People are transactional by nature. If someone does something nice for us, we often respond by doing nice things for them. We love the people who love us. Why wouldn’t God be the same way?

But God’s ways are different from ours. His love doesn’t wait for us to come to him. Instead, he comes to us, and he loves us long before we loved him. We can’t earn God’s promises even through our worship, praise, and faith. We are saved by grace after all.

Jesus Trusted God

Jesus is the perfect test case for how God’s promises work. He was the only perfect human being, which means he trusted his Father for everything. When Jesus was attacked in his hometown, the Father protected him. He watched over Jesus for his whole life.

Jesus trusted his Father so much that he wasn’t concerned about danger. Jesus and his disciples were out on the sea of Galilee when a storm arose. Jesus was exhausted from teaching all day, so he fell asleep on a pillow. The storm raged around the boat, and the disciples were terrified that they were going to drown. These were experienced fishermen who knew how to handle a boat. They weren’t easily scared.

But Jesus lay asleep, head on his pillow. That’s trust, to be so calm in a storm. Nature raged around him. His disciples were shouting. But Jesus slept as securely as a young child in his father’s arms. Jesus truly trusted his Father.

But Jesus Died

But the Father didn’t protect Jesus from all danger. Every Christian knows that story. Jesus was arrested in the Garden of Gethsemane, and the guards dragged him before the Sanhedrin. They beat him and falsely accused him before taking him to Pontius Pilate. The weak-willed Pilate succumbed to the crowd’s will, so he beat Jesus and whipped him. When that wasn’t enough, Pilate washed his hands of Jesus, and he allowed Jesus to be crucified.

Where were the promises of Psalm 91?

For he will command his angels concerning you to guard you in all your ways. On their hands they will bear you up, lest you strike your foot against a stone.

It promises that God will protect you from even striking your foot against a stone, but the Father sent Jesus to the cross to die! Even the Pharisees noticed that the Father’s promises seemed to fail. In Matthew 27:43 they say, “He trusts in God; let God deliver him now.”

And the Father did it. He delivered Jesus from death by raising him from the dead. After terrible danger, torture, and death, the Father saved him. Psalm 91’s promises finally came true after everyone thought they had failed.

The Holy Martyrs

The same is true for the holy martyrs. They trusted God, even when they faced torture and death. Consider St. Ignatius, a bishop from the first century AD. We know him best from a series of letters he wrote while Roman guards took him to the capital for execution.

In his letter to the Romans, chapter 4, he writes:

I write to the Churches, and impress on them all, that I shall willingly die for God, unless ye hinder me… Suffer me to become food for the wild beasts, through whose instrumentality it will be granted me to attain to God. I am the wheat of God, and let me be ground by the teeth of the wild beasts, that I may be found the pure bread of Christ.

Can you imagine writing that? He tells the Roman church to refrain from saving him. Don’t try to get him out of jail. Don’t try to rescue him. He wants to be literally thrown to the lions. And, by doing so, he would receive the crown of life and prove to be a true Christian. Ignatius trusted that the Lord Almighty is a shelter and fortress. And just like Jesus, he will be raised up on the last day.

We know story after story of martyrs who died with this faith, men and women who would rather be crucified, thrown to lions, of beheaded than deny Jesus Christ. They trusted that God could deliver them even from death, because they knew that the Father had delivered Jesus from the same.

My Refuge and My Fortress

We can trust the psalmist’s words, too. Just like St. Ignatius and all the martyrs, we know that Jesus was raised from the dead. We also know that everyone who is in Christ will also be raised from the dead on the last day to receive eternal life.

Because we have been united with Christ in his death, we are also united with him in his resurrection. Paul writes in Romans 6:

We were buried therefore with him by baptism into death, in order that, just as Christ was raised from the dead by the glory of the Father, we too might walk in newness of life. For if we have been united with him in a death like his, we shall certainly be united with him in a resurrection like his.

We can trust, even in the midst of terrible danger, that God’s promises will come true for us. Nothing can stop them, because they have already happened through Jesus. So, when you are in danger, turn to Psalm 91. You will see God’s promises to you to protect you even when you have passed into the grave.

via Tumblr When You Are in Danger: Verse Behind the Christian T-Shirt

via Unbound - Blog http://ourlordstyles.weebly.com/blog/when-you-are-in-danger-verse-behind-the-christian-t-shirt syndicated from https://ourlordstyle.com/

0 notes

Text

When You Are in Danger: Verse Behind the Christian T-Shirt

Most of us don’t see much danger. We move from climate-controlled homes, to air conditioned offices by moving at cheetah speeds inside extraordinarily safe vehicles. When we get sick, we get cures for diseases that have killed millions in the past. We have medications that can alleviate chronic conditions and extend our lives beyond what most people in history had ever dreamed.

But there is still some danger. Our careful planning still can’t stop natural disasters from destroying belongings and taking lives. Modern medicine still can’t put off death forever, despite our best efforts. Sophisticated security systems still can’t prevent evil people from hurting us. Danger is still here.

When You Are in Danger: Psalm 91

So where should a Christian turn to encourage us when we’re in danger? Our Bible Emergency Numbers Christian t-shirt points us to Psalm 91. The psalm was made famous (besides being in the Bible) by the song On Eagle’s Wings, composed by Michael Joncas.

Psalm 91 is a psalm that shows amazing trust in God. LIke many of these psalms, it encourages Christians to see our God as a shelter, a fortress:

He who dwells in the shelter of the Most High will abide in the shadow of the Almighty. I will say to the Lord, “My refuge and my fortress, my God, in whom I trust.”

The whole psalm describes how God protects the people who call on his name. The Psalmist lists several dangers that people in his day might face, pestilence, darkness, arrows, and armies. He writes that God covers his people with his wings to protect them like a bird covers its young. God promises to protect his people.

The Psalmist summarizes his message when God speaks in the last few verses:

“Because he holds fast to me in love, I will deliver him; I will protect him, because he knows my name. When he calls to me, I will answer him; I will be with him in trouble; I will rescue him and honor him. With long life I will satisfy him and show him my salvation.”

God promises to protect the people who call on his name.

But Christians Get Hurt All The Time…

Psalm 91 raises an obvious question, “How can these promises be true when Christians get hurt all the time?” One possible answer is that these Christians just don’t have enough faith. Here’s how the argument usually goes: If you believe enough, if you trust hard enough, if your faith is strong enough, then God will protect you.

It makes sense from a human perspective, too. People are transactional by nature. If someone does something nice for us, we often respond by doing nice things for them. We love the people who love us. Why wouldn’t God be the same way?

But God’s ways are different from ours. His love doesn’t wait for us to come to him. Instead, he comes to us, and he loves us long before we loved him. We can’t earn God’s promises even through our worship, praise, and faith. We are saved by grace after all.

Jesus Trusted God

Jesus is the perfect test case for how God’s promises work. He was the only perfect human being, which means he trusted his Father for everything. When Jesus was attacked in his hometown, the Father protected him. He watched over Jesus for his whole life.

Jesus trusted his Father so much that he wasn’t concerned about danger. Jesus and his disciples were out on the sea of Galilee when a storm arose. Jesus was exhausted from teaching all day, so he fell asleep on a pillow. The storm raged around the boat, and the disciples were terrified that they were going to drown. These were experienced fishermen who knew how to handle a boat. They weren’t easily scared.

But Jesus lay asleep, head on his pillow. That’s trust, to be so calm in a storm. Nature raged around him. His disciples were shouting. But Jesus slept as securely as a young child in his father’s arms. Jesus truly trusted his Father.

But Jesus Died

But the Father didn’t protect Jesus from all danger. Every Christian knows that story. Jesus was arrested in the Garden of Gethsemane, and the guards dragged him before the Sanhedrin. They beat him and falsely accused him before taking him to Pontius Pilate. The weak-willed Pilate succumbed to the crowd’s will, so he beat Jesus and whipped him. When that wasn’t enough, Pilate washed his hands of Jesus, and he allowed Jesus to be crucified.

Where were the promises of Psalm 91?

For he will command his angels concerning you to guard you in all your ways. On their hands they will bear you up, lest you strike your foot against a stone.

It promises that God will protect you from even striking your foot against a stone, but the Father sent Jesus to the cross to die! Even the Pharisees noticed that the Father’s promises seemed to fail. In Matthew 27:43 they say, “He trusts in God; let God deliver him now.”

And the Father did it. He delivered Jesus from death by raising him from the dead. After terrible danger, torture, and death, the Father saved him. Psalm 91’s promises finally came true after everyone thought they had failed.

The Holy Martyrs

The same is true for the holy martyrs. They trusted God, even when they faced torture and death. Consider St. Ignatius, a bishop from the first century AD. We know him best from a series of letters he wrote while Roman guards took him to the capital for execution.

In his letter to the Romans, chapter 4, he writes:

I write to the Churches, and impress on them all, that I shall willingly die for God, unless ye hinder me… Suffer me to become food for the wild beasts, through whose instrumentality it will be granted me to attain to God. I am the wheat of God, and let me be ground by the teeth of the wild beasts, that I may be found the pure bread of Christ.

Can you imagine writing that? He tells the Roman church to refrain from saving him. Don’t try to get him out of jail. Don’t try to rescue him. He wants to be literally thrown to the lions. And, by doing so, he would receive the crown of life and prove to be a true Christian. Ignatius trusted that the Lord Almighty is a shelter and fortress. And just like Jesus, he will be raised up on the last day.

We know story after story of martyrs who died with this faith, men and women who would rather be crucified, thrown to lions, of beheaded than deny Jesus Christ. They trusted that God could deliver them even from death, because they knew that the Father had delivered Jesus from the same.

My Refuge and My Fortress

We can trust the psalmist’s words, too. Just like St. Ignatius and all the martyrs, we know that Jesus was raised from the dead. We also know that everyone who is in Christ will also be raised from the dead on the last day to receive eternal life.

Because we have been united with Christ in his death, we are also united with him in his resurrection. Paul writes in Romans 6:

We were buried therefore with him by baptism into death, in order that, just as Christ was raised from the dead by the glory of the Father, we too might walk in newness of life. For if we have been united with him in a death like his, we shall certainly be united with him in a resurrection like his.

We can trust, even in the midst of terrible danger, that God’s promises will come true for us. Nothing can stop them, because they have already happened through Jesus. So, when you are in danger, turn to Psalm 91. You will see God’s promises to you to protect you even when you have passed into the grave.

When You Are in Danger: Verse Behind the Christian T-Shirt published first on https://ourlordstyle.com/

0 notes

Text

When You Are in Danger: Verse Behind the Christian T-Shirt

Most of us don’t see much danger. We move from climate-controlled homes, to air conditioned offices by moving at cheetah speeds inside extraordinarily safe vehicles. When we get sick, we get cures for diseases that have killed millions in the past. We have medications that can alleviate chronic conditions and extend our lives beyond what most people in history had ever dreamed.

But there is still some danger. Our careful planning still can’t stop natural disasters from destroying belongings and taking lives. Modern medicine still can’t put off death forever, despite our best efforts. Sophisticated security systems still can’t prevent evil people from hurting us. Danger is still here.

When You Are in Danger: Psalm 91

So where should a Christian turn to encourage us when we’re in danger? Our Bible Emergency Numbers Christian t-shirt points us to Psalm 91. The psalm was made famous (besides being in the Bible) by the song On Eagle’s Wings, composed by Michael Joncas.

Psalm 91 is a psalm that shows amazing trust in God. LIke many of these psalms, it encourages Christians to see our God as a shelter, a fortress:

He who dwells in the shelter of the Most High will abide in the shadow of the Almighty. I will say to the Lord, “My refuge and my fortress, my God, in whom I trust.”

The whole psalm describes how God protects the people who call on his name. The Psalmist lists several dangers that people in his day might face, pestilence, darkness, arrows, and armies. He writes that God covers his people with his wings to protect them like a bird covers its young. God promises to protect his people.

The Psalmist summarizes his message when God speaks in the last few verses:

“Because he holds fast to me in love, I will deliver him; I will protect him, because he knows my name. When he calls to me, I will answer him; I will be with him in trouble; I will rescue him and honor him. With long life I will satisfy him and show him my salvation.”

God promises to protect the people who call on his name.

But Christians Get Hurt All The Time…

Psalm 91 raises an obvious question, “How can these promises be true when Christians get hurt all the time?” One possible answer is that these Christians just don’t have enough faith. Here’s how the argument usually goes: If you believe enough, if you trust hard enough, if your faith is strong enough, then God will protect you.

It makes sense from a human perspective, too. People are transactional by nature. If someone does something nice for us, we often respond by doing nice things for them. We love the people who love us. Why wouldn’t God be the same way?

But God’s ways are different from ours. His love doesn’t wait for us to come to him. Instead, he comes to us, and he loves us long before we loved him. We can’t earn God’s promises even through our worship, praise, and faith. We are saved by grace after all.

Jesus Trusted God

Jesus is the perfect test case for how God’s promises work. He was the only perfect human being, which means he trusted his Father for everything. When Jesus was attacked in his hometown, the Father protected him. He watched over Jesus for his whole life.

Jesus trusted his Father so much that he wasn’t concerned about danger. Jesus and his disciples were out on the sea of Galilee when a storm arose. Jesus was exhausted from teaching all day, so he fell asleep on a pillow. The storm raged around the boat, and the disciples were terrified that they were going to drown. These were experienced fishermen who knew how to handle a boat. They weren’t easily scared.

But Jesus lay asleep, head on his pillow. That’s trust, to be so calm in a storm. Nature raged around him. His disciples were shouting. But Jesus slept as securely as a young child in his father’s arms. Jesus truly trusted his Father.

But Jesus Died

But the Father didn’t protect Jesus from all danger. Every Christian knows that story. Jesus was arrested in the Garden of Gethsemane, and the guards dragged him before the Sanhedrin. They beat him and falsely accused him before taking him to Pontius Pilate. The weak-willed Pilate succumbed to the crowd’s will, so he beat Jesus and whipped him. When that wasn’t enough, Pilate washed his hands of Jesus, and he allowed Jesus to be crucified.

Where were the promises of Psalm 91?

For he will command his angels concerning you to guard you in all your ways. On their hands they will bear you up, lest you strike your foot against a stone.

It promises that God will protect you from even striking your foot against a stone, but the Father sent Jesus to the cross to die! Even the Pharisees noticed that the Father’s promises seemed to fail. In Matthew 27:43 they say, “He trusts in God; let God deliver him now.”

And the Father did it. He delivered Jesus from death by raising him from the dead. After terrible danger, torture, and death, the Father saved him. Psalm 91’s promises finally came true after everyone thought they had failed.

The Holy Martyrs

The same is true for the holy martyrs. They trusted God, even when they faced torture and death. Consider St. Ignatius, a bishop from the first century AD. We know him best from a series of letters he wrote while Roman guards took him to the capital for execution.

In his letter to the Romans, chapter 4, he writes:

I write to the Churches, and impress on them all, that I shall willingly die for God, unless ye hinder me… Suffer me to become food for the wild beasts, through whose instrumentality it will be granted me to attain to God. I am the wheat of God, and let me be ground by the teeth of the wild beasts, that I may be found the pure bread of Christ.

Can you imagine writing that? He tells the Roman church to refrain from saving him. Don’t try to get him out of jail. Don’t try to rescue him. He wants to be literally thrown to the lions. And, by doing so, he would receive the crown of life and prove to be a true Christian. Ignatius trusted that the Lord Almighty is a shelter and fortress. And just like Jesus, he will be raised up on the last day.

We know story after story of martyrs who died with this faith, men and women who would rather be crucified, thrown to lions, of beheaded than deny Jesus Christ. They trusted that God could deliver them even from death, because they knew that the Father had delivered Jesus from the same.

My Refuge and My Fortress

We can trust the psalmist’s words, too. Just like St. Ignatius and all the martyrs, we know that Jesus was raised from the dead. We also know that everyone who is in Christ will also be raised from the dead on the last day to receive eternal life.

Because we have been united with Christ in his death, we are also united with him in his resurrection. Paul writes in Romans 6:

We were buried therefore with him by baptism into death, in order that, just as Christ was raised from the dead by the glory of the Father, we too might walk in newness of life. For if we have been united with him in a death like his, we shall certainly be united with him in a resurrection like his.

We can trust, even in the midst of terrible danger, that God’s promises will come true for us. Nothing can stop them, because they have already happened through Jesus. So, when you are in danger, turn to Psalm 91. You will see God’s promises to you to protect you even when you have passed into the grave.

0 notes