#if it's because the book was published in the 1950s.

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

For your book bingo, if we read a series, does each book get to have it's own space or should we not count the rest of the series because the first book already was put into a space.

And if I were to read something like Poe's The Tell Tale Heart and Cask of Amontillado would I put that in something like 'published before 1950' or rather short story collection if I read it with some of his other stories?

up to you dude I'm not in charge of you

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

I finally scored a copy of The War Lover by Hersey (whoo-hoo free from Thriftbooks! 11/10 love that site, please go check it out as well as BetterWorldBooks) and I'm very ????? about how it censors every swear. Something about writing "s—" is more jarring and offensive to me than just writing "shit".

We all know what's under there, Mr. Hersey, you don't... you really don't have to do that. It's okay. This book is literally about the inhumanity of war but we're not censoring that. Just let your characters say "shit".

#it made me giggle#anyway i've never read john hersey and now i'm wondering if it was something he always did as like. a choice? or#if it's because the book was published in the 1950s.#merri mumbles

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

wondering about whether you could rec some "romance is a social construct" texts? ofc it is, but i like having books and articles to reference/learn specifics from/see how these ideas have developed.

Sure! Here's a quick reading list. Bear in mind that I am not a professional historian and my reading on this subject is a little diffuse. I'm not tackling the behavioral ecology stuff right now because a) I don't have a more direct book rec off the top of my head than Evolution's Rainbow, which is not technically focused on social monogamy, and also b) I approach that whole field with my eyes wide open for people letting their own perspectives and cultural views get in the way of their observations of animals, and I do not have the energy to go deal with it right now.

If you're going to read two books, read these two:

Stephanie Coontz, Marriage, A History: how love conquered marriage. 2006. All of Coontz' work, having to do with the social construction of the family, is relevant reading to this question (and I'd also recommend The Nostalgia Trap, because the historical context of how we conceptualize families is a major part of the construction of romantic love), but this one is most focused on the social construction of romantic love specifically and what it has replaced. Coontz is, I will disclose cheerfully, a major formative influence on my thinking.

Moira Wegel, Labor of Love: The Invention of Dating. 2016. Exactly what it says on the tin; focuses more closely on the modern invention of dating and romance.

Other useful readings to help inform your understanding of different ways that various people have conceptualized sex, sexuality, society and long-term connection include:

George Chauncey, Why Marriage? 2015. Chauncey is best known for Gay New York, which also offers a useful history of the way that relationship models and social constructs for understanding homosexuality changed among men having sex with men c. 1900 to 1950. This book, published just before Obergefell v. Hodges, is a discussion of why contemporary queer rights organizations focused on same-sex marriage as an activism plank in the wake of AIDS organizing. I find it really useful to read queer history when I'm thinking about how we understand and construct the concept of romantic relationships, because queers complicate the mainstream, heteronormative concepts of what marriage and romantic relationships actually are. More importantly, queer activist organizing around marriage has played a major role in shaping our collective understanding of romance and marriage in the past twenty years.

Elizabeth Abbott, A History of Celibacy, 2000. In order to understand how various cultures construct understandings of marriage and spousal relationships, it can be illustrative to consider what the people who are explicitly not participating in the institution are doing and why not. I found this an interesting pass over historical and social institutions that forbid (or forbade) marriage with a discussion about general trends driving these institutions, individuals, and movements towards celibacy.

Eleanor Janega, The Once and Future Sex, 2023. This is a very pointed historical look at gender roles, concepts of beauty, and concepts of sex, attraction, and marriage among medieval Europeans with an extended meditation on what ideas have and have not changed between that time and today. I include this work because I think a deep dive into medieval notions of courtly romance is useful, partly because it is an important origin of our modern notion of romantic love and partly because it is so usefully and starkly different from that modern notion! Sometimes the best way to understand the cultural construction of ideas in your own society is to go look at someone else's and see where things are the same versus different.

It's a mish-mash of recommendations, and I'm reaching more for books that have stuck with me over the years than a clean scholarly approach to the subject. I hope other folks will chime in for you with their own recommendations!

462 notes

·

View notes

Text

Palace of the Republic, Berlin

The right to work at a job of one’s own choice was guaranteed by the East German constitution (Aus erster Hand, 1987). While there were some (mostly alcoholics) who continuously refused to show up for jobs offered by the state, their numbers represented only about 0.2% of the entire East German work force, and only 0.1% of the scheduled work hours of the rest of the labor force was lost due to unexcused absences (Krakat, 1996). These findings are especially noteworthy, given that people were generally protected from being fired (or otherwise penalized) for failing to show up for work or for not working productively (Thuet, 1985). The importance of the communist characteristic of full employment to workers is reflected in a 1999 survey of eastern Germans that indicated about 70% of them felt they had meaningfully less job security in the unified capitalist country in the 1990s than they did in communist East Germany (Kramm, 1999)

The Triumph of Evil, A. Murphy (2002)

The GDR had more theatres per capita than any other country in the world and in no other country were there more orchestras in relation to population size or territory. With 90 professional orchestras, GDR citizens had three times more opportunity of accessing live music, than those in the FRG, 7.5 times more than in the USA and 30 times more than in the UK. It also had one of the world’s highest book publishing figures. This small country with its very limited economic resources, even in the fifties was spending double the amount on cultural activities as the FRG. Every town of 30,000 or more inhabitants in the GDR had its theatre and cinema as well as other cultural venues. [...] Subsidised tickets to the theatre and concerts were always priced so that everyone could afford to go. Many factories and institutions had regular block-bookings for their workers which were avidly taken up. School pupils from the age of 14 were also encouraged to go to the theatre once a month and schools were able to obtain subsidised tickets. [...] All towns and even many villages had their own ‘Houses of Culture’, owned by the local communities and open for all to use. These were places that offered performance venues, workshop space and facilities for celebratory gatherings, discos, drama groups etc. There was a lively culture of local music and folk-song groups, as well as classical musical performance.

Stasi State or Socialist Paradise? The German Democratic Republic and What Became of It, Bruni de la Motte and John Green (2015)

Work itself was elevated to a place of pride and esteem and, even if you were in a lower paid job, you were valued for the work you did as a necessary contribution to the functioning of society. The socialist countries were also designated ‘workers’ states and it was not merely an empty phrase when the GDR government argued that the workers, who produced the commodities that society needed, should be placed at the forefront of society. Those who did heavy manual work, like miners or steel workers, enjoyed certain privileges: better wages and health care than those in less strenuous or dangerous professions. The GDR had one of the most comprehensive workers’ rights legislation of any other country in the world. From 1950 onwards, there was a guaranteed right to work. This right applied to everybody, including disabled people and those with criminal records. Employers were made responsible for the training and integration of everyone. This meant that everybody felt they had a place in society and were needed. This was particularly important for disabled people and those who wanted a new start in life after being convicted of a crime. Working people were under a much more relaxed discipline in the workplace. Because there was job security and it was almost impossible to be sacked, an authoritarian discipline was difficult, if not impossible, to achieve. In Western countries work discipline is invariably enforced by the implicit threat of job loss. In the GDR, only in cases of serious misconduct or incompetence would employees be sacked. There were individual cases where employees were sacked illegally for what was considered ‘oppositional’ or ‘anti-state behaviour’, but usually the sanction would involve demotion or being transferred to a different workplace. This job security gave employees a sense of confidence and a considerable power in the workplace. It meant that workers could and would voice criticism over inefficiencies or bad management without having to fear for their job. Job security and lack of fear about losing it was probably one of the greatest advantages the socialist system offered working people. Even in cases where a worker was sacked from one job, other alternative work would be offered, even if not on the same level. The other side of the coin was that there was also a social obligation to work - the GDR had no system of unemployment benefit, because the concept of unemployment did not exist.

Stasi State or Socialist Paradise? The German Democratic Republic and What Became of It, Bruni de la Motte and John Green (2015)

407 notes

·

View notes

Note

is it possible for a woman to inherit a sect or only sons?

Hi nonny!

I wrote about this a bit here, but traditionally to like, the wuxia genre: 1) this was (depending on the sect in question of course) mostly a meritocracy, so it's not strictly true that the daughters or sons of the former sect leader is inheriting the sect but also 2) the gender for many sects is entirely irrelevant, many prominent jianghu families in many many wuxia books aren't exactly like, desperate for sons even if they have (1) child and that child is a girl, like what will girl do? girl will learn martial arts. like it's hard?

In fact in classical wuxia it's actually quite...common to have female sect leaders (either of entirely female sects or of mixed gender sects) because sects are kind of, things you join rather than things you're born to and you inherit them because shifu said so, not due to biology.

For example, Huang Rong in Legend of the Condor Heroes and Return of the Condor Heroes, is the sect leader for the Beggar Clan, which is the largest and most powerful sect in the wulin instead of her husband Guo Jing, who was also a disciple of the previous sect leader.

Xiao Longnv from Return of the Condor Heroes comes from the Ancient Tomb Sect which, only accepts women btw, so all of their sect leaders have been women.

Yuan Ziyi's shifu, Baixiao Shenni, from Young Flying Fox was the sect leader of the Tianshan sect and a Buddhist Nun.

Dingxian from Xiao Ao Jiang Hu and her sisters, Dingjing and Dingyi, form a group called the "Three Elder Nuns" who are the leaders of the Northern Hengshan Sword Sect. Also from XAJH, Lan Fenghuang is the leader of the Five Immortal's Cult.

I'm not going to keep going down the list of like, female sect leaders in the traditional sense of the jianghu (for the record, all of the above books were written and published in the 1950s-1970s so it's not a recent phenomenon at all), but like, wuxia as a genre has in general, been surprisingly egalitarian on matters of gender. The fact of the matter is, this was the genre that first told me, at 7 or 8 years old that like, women can be powerful and intelligent and unhinged, whether they're villains or heroes or anywhere in between.

So uh, I think the reason you might not be aware of this Nonny (which is not a strike against you in any way!) is because danmei is primarily what's popular right now and danmei as a genre from what I've seen does not have uh, a great track record of bountiful female characters who are well rounded and extant or in positions of power.

378 notes

·

View notes

Text

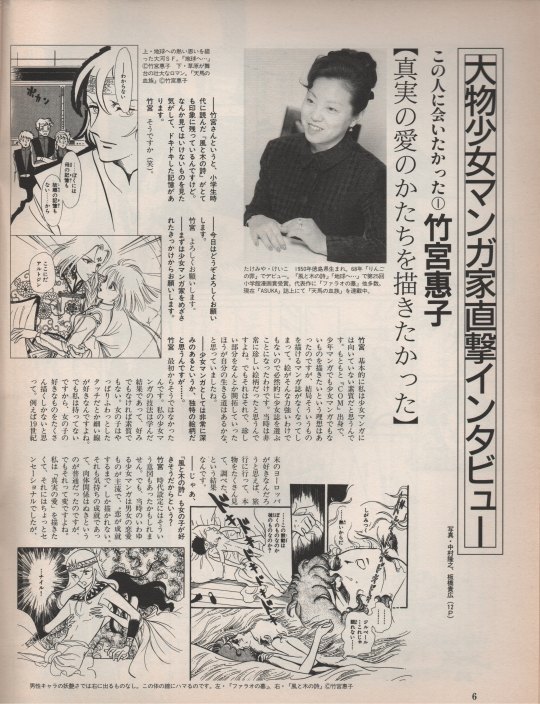

A short Takemiya Keiko interview from 1998

My "All Things Takemiya" detective friend, Platypus, provided me with a two-page Takemiya Keiko interview scanned by @97tears from the now discontinued Hato yo! (鳩よ! - Oh, Pigeons!) magazine. It was a literary magazine published between 1983 and 2002—a publication you probably wouldn't look at if you were searching up on Takemiya, ig.

You can see the Japanese original taken from the 1998 April issue of the magazine, and my (poor) translation of it under the cut.

Takemiya Keiko Interview from issue #4 of Hato yo (1998)

An interview with a master mangaka herself!

I’ve always wanted to meet them! 1 – Takemiya Keiko

“I wanted to draw real love”

Takemiya Keiko. Born in Tokushima in 1950. Debuted with “Ringo no Tsumi” in 1968. Won the 25th Shogakukan Manga Award with “Kaze to Ki no Uta” and “Terra e.” Representative works include “Pharaoh no Haka” among others. “Tenma no Ketsuzoku” is currently being serialized in Asuka Magazine.

I read “Kaze to Ki no Uta” during elementary school. It has left a very deep impression on me. I remember that when Ms. Takemiya is mentioned. It was like I was looking at something I was not supposed to look, and I still remember the thrill I felt. Takemiya: Oh, is that so? (laughs)

Thank you so much for being with me today. Takemiya: And thank you for having me.

Shall we start with what prompted you to become a shoujo manga artist? Takemiya: Fundamentally, I was not suited for shoujo manga. I debuted in COM, and my dream was to draw manga that was neither shounen nor shoujo. But alas, the magazine in which I could draw my ideal manga was no more. My style didn’t have much “power” in it, so I inevitably had to choose a shoujo manga magazine. I think my art style was really uncommon at the time. But it was what it was, and I thought to myself, maybe capitalizing on that was the path I should take.

Your works have an extraordinary depth as far shoujo manga goes... They have a unique art style... Takemiya: It hasn’t always been like that. My shoujo manga technique was the fruit of what I have studied. It was not a result of my personal taste, nor my innate skills. Girls like that feathery, light touch. They like fine lines. But I didn’t have any of those. So, I figured drawing things girls would like a lot was my only choice. For instance, when I thought how they must like Europe at the end of the 19th century, I went on a trip as a result. I saw the real thing at its source, and did research on it.

Then was Kaze to Ki no Uta born because you thought girls would like it? Takemiya: That might have played into my choice of the time period the story’s set in. However, romance stories between a boy and a girl was the norm in shoujo manga at the time. You could only draw “And they lived happily ever after...” stories. And that happiness was only on the emotional level. It was normal to exclude all physical contact. But that is simply “affection.” I wanted to draw “real love.” I admit it was a little too sensational, but I thought doing it through same-sex love was the best way to go about it. That’s how I drew Kaze to Ki no Uta.

The sex scenes between men were quite a shock for me as a little child. That’s how I learned homosexuality existed. Takemiya: At the time, there was an official notice published by the Ministry of Education that stipulated that “You shall not draw a boy and a girl getting intimate!” However, if it was two boys, things were somehow fine... I thought I’d found a loophole! (laughs)

These days, there are more extreme books labeled as “yaoi.” What do you think about them? Takemiya: At the end of the day, doujinshi are doujinshi. They focus on personal enjoyment of a group. I consider myself a “craftsman,” and if I look at it from a craftsman's standpoint, I am not wholly satisfied with how they leave many things unexplained, or how they have no conclusion. At their level, I’d liked if those artists too felt more dissatisfied... If they aimed to be more conclusive. They have the talent to draw, so I’d love them to polish those skills. I’m sometimes told that it all started with “Kazeki,” and that I must take responsibility. And every time, I think to myself, “Oh... Re-really? Dit it?” (laughs) I wish someone drew something so awesome that it would blow Kazeki out of the water...

I’d love that too! You called yourself a “craftsman,” but what exactly makes you think so? Takemiya: I really love the word “craftsman.” I’m not interested in trying to reach an ideal of art that would not resonate with the public. I believe manga is something aimed at the general public. Otherwise, I would not consider it to have artistic value.

Spoken like a real pro... Which brings me to Terra e... I think that’s the most widely-accepted manga of yours by the general public, and it was published in a shounen magazine. Why is it the outlier to be published in a shounen magazine? Takemiya: I received an offer for it, but the truth is, I had always wanted to draw for a shounen magazine. That’s why accepted. But I needed to draw in the shoujo manga audience too, so I wanted the story to offer the best for both demographics. So I tried to have the concept to be that of shoujo manga, and the style to be that of shounen manga as much as possible.

Is it different to draw for a shounen manga magazine, and a shoujo manga magazine? Takemiya: You don’t have to hold back in shounen magazines. It fine to draw more hardcore stuff. But in shoujo magazines, that’s out of the question. There’s a trend that dictate that you should explain things in long-winded ways and spoil the reader, because girls like it when you reveal things to them through subterfuge, so don’t hit them directly with hard stuff.

But after that, you’ve never drawn for shounen magazines which allowed you to draw as you wished. Takemiya: Shounen magazines are mostly weekly. I cannot keep up with that. My art has fine details, so it takes me a lot of time to draw.

Then will you be solely drawing for shoujo magazines in the future? Takemiya: I can’t really say that I will. I’m currently working for a shoujo magazine with “Tenma no Ketsuzoku”, and with volume releases. I recently released an illustration book titled “Hermès no Michi.” I needed to base myself on documents and explain them in drawings. And they couldn’t be any kind of drawing, they needed to be interesting. Trying to come up with ways to do that was a very fun experience. So for starters, I’d like to undertake a work like that again. That kind of work I’m working on right now is a story about the fugitives of the Heike Clan in Tokushima.*

*T/N: She is referring to “Heian Joururi Monogatari.”

To finish our interview off, I’d like ask a question about the Year 24 Group (shoujo manga artists born around the 24th year of the Shouwa Era like Takemiya Keiko, Hagio Moto, and Ooshima Yumiko, who have influenced the shoujo manga world in the following years) which is still very prominent: Are you still conscious of it? Takemiya: Year 24 is a thing of the past in the modern manga scene. I think it’s irrelevant now. Manga is evolving, becoming something else after being painted over continuously. I had fun when I was part of that group, but I don’t feel like dragging it out. I don’t want to cling to nice memories of the past as I work, and want to focus on how I currently think and feel. I want to do what I think is most fun at the moment.

#takemiya keiko#keiko takemiya#竹宮 惠子#24年組#year 24 group#interview#hato yo!#鳩よ!#shoujo manga history#manga history#kaze to ki no uta#風と木の詩#takemiya keiko interview#yaoi

136 notes

·

View notes

Note

steve and billy teaching in the same school!! there's these teachers in my school and they work right across the hall from each other. they're always yelling into each others classrooms.

she teaches english lit 101 and he teaches gov 102

"Harrington!"

Some of the kids snickered quietly when Mr. Harrington jumped at the shout from across the hall.

He stared blankly at the last word he had written on the board, the black Expo mark wiggles from where he had jumped at the yell of his name.

He turned around, sighing exaggeratedly at Mr. Hargrove standing in the doorway.

"Kids, excuse my coworker here." He crossed his arms around his chest. "Can I help you?"

"Yeah, you can Mr. H."

Steve rolled his eyes as his husband swaggered into his classroom, leading a line of ninth graders with him.

It's not the first time Billy's interrupted his class with a question about some inane bullshit that launched Steve into an over-excited rant for the rest of class.

Steve's tenth and eleventh graders were already closing their textbooks, knowing their teacher was just about to be insanely distracted for the rest of class.

"The birds n' I are reading The Crucible."

Fuck.

Steve's pretty sure Billy's kids pay him to bring them across the hall for these impromptu lectures.

"Witch hunts. I get it."

"Yeah, you know. Anyway, I'm giving some context to the publishing of the book. The Red Scare in the United States, well, the second Red Scare, as well as the rise of McCarthyism coincided with the publishing of the play."

Goddammit.

Steve's fucking master's thesis was on all about McCarthyism (more specifically, how the second Red Scare was directly linked to the Lavender Scare.) He cited the stupid play in his research.

Billy knows that. They were already engaged by the time Steve began his master's program.

Fuck this guy, for real.

Steve quietly closed his power point presentation on interest groups in America.

"Fine. Mr. Hargrove's class, find a seat. My class, your packet is still due Friday. I'll post the slides after class." He glared at Billy.

Billy grinned right back, his tongue poking out in that frustrating way it has since high school.

"1950s United States. What do you know?"

A few hands went up.

Even Billy raised his stupid hand. Steve ignored him.

-

"Which brings us to the end of the decade. With the early 1960s, we have the reformation in the Catholic Church, known as Vatican ll-"

The bell cut him off mid-sentence, and there was a mad scramble as the students all tried to pack up as quickly as possible, before Steve could keep going.

"My class," he nearly shouted over the scraping of chairs against linoleum. "Your packets are still due Friday! I don't care that Mr. Hargrove interrupted our time."

"And birds! The rubric is posted on the class page! I want outlines handed in on Tuesday."

The classroom door closed behind the final kid.

"You're a dick."

Billy laughed.

"Nah, you just teach that shit so much better than I do."

Steve rolled his eyes. He sat behind his desk, yanking over a stack of twelfth grade research assignments to begin grading. Billy perched on the other side of his desk.

"Y'know, you could just ask me to come in and lecture. You don't have to interrupt my own class."

"Yeah, but it's fun to wind you up and watch you go. And I think the birds like it when they see that you're passionate about something. Why do you think I always start with The Joy Luck Club?"

"Because you have mommy issues."

"No. Because Ying-ying's story makes me sob like a bitch, and the birds get to realize that I'm a real-life human."

Steve scrubbed his face with his hands, collecting himself before facing his dumbass husband again.

"Wait, you said they had an essay due. What's the essay?"

"Oh, comparing the Salem Witch Trials and the goings on of the U.S. government in the mid 1950s. You know."

"So, you created an assignment, knowing that I would infodump all that shit to your kids?"

"Yes."

"I want a divorce."

Billy laughed, leaning over Steve's desk to kiss his forehead.

"No, you don't."

"No, I don't. I love you. But also you suck."

The bell sounded to indicate the end of passing period.

Billy got off the desk, stretching with a groan.

"Would you be mad if I brought my senior class in?"

Steve glared at him in the doorway.

"What's the assignment?"

"They're presenting on the parallels between 1984 and the current political climate."

Goddammit.

"Bring 'em in."

#billy calls his students birds bc he's not aloud to call them shitbirds#p much the same reason i call my students gooses#bc of that letterkenny line 'those are canada's fucking gooses'#anyway yeah#read the joy luck club if you haven't it'll make you cry whether or not you have mommy issues#steve harrington#billy hargrove#harringrove#yikes writes

150 notes

·

View notes

Text

Emil Ferris’s long-awaited “My Favorite Thing Is Monsters Book Two”

NEXT WEEKEND (June 7–9), I'm in AMHERST, NEW YORK to keynote the 25th Annual Media Ecology Association Convention and accept the Neil Postman Award for Career Achievement in Public Intellectual Activity.

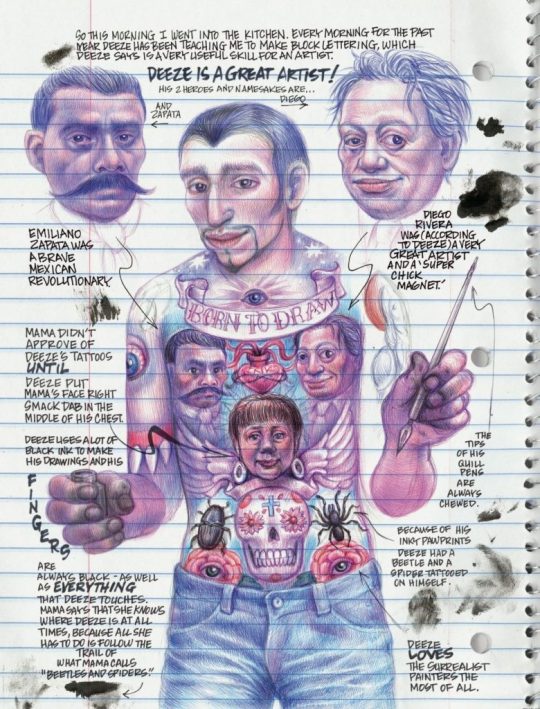

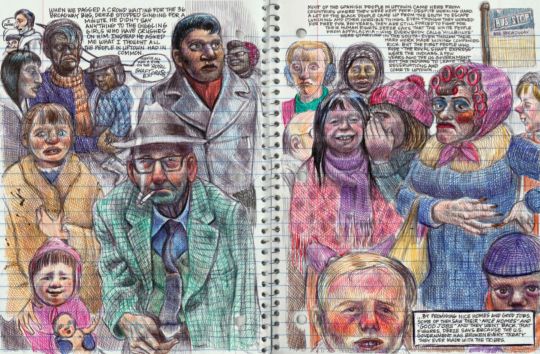

Seven years ago, I was absolutely floored by My Favorite Thing Is Monsters, a wildly original, stunningly gorgeous, haunting and brilliant debut graphic novel from Emil Ferris. Every single thing about this book was amazing:

https://memex.craphound.com/2017/06/20/my-favorite-thing-is-monsters-a-haunting-diary-of-a-young-girl-as-a-dazzling-graphic-novel/

The more I found out about the book, the more amazed I became. I met Ferris at that summer's San Diego Comic Con, where I learned that she had drawn it over a while recovering from paralysis of her right – dominant – hand after a West Nile Virus infection. Each meticulously drawn and cross-hatched page had taken days of work with a pen duct-taped to her hand, a project of seven years.

The wild backstory of the book's creation was matched with a wild production story: first, Ferris's initial publisher bailed on her because the book was too long; then her new publisher's first shipment of the book was seized by the South Korean state bank, from the Panama Canal, when the shipper went bankrupt and its creditors held all its cargo to ransom.

My Favorite Thing Is Monsters told the story of Karen Reyes, a 10 year old, monster-obsessed queer girl in 1968 Chicago who lives with her working-class single mother and her older brother, Deeze, in an apartment house full of mysterious, haunted adults. There's the landlord – a gangster and his girlfriend – the one-eyed ventriloquist, and the beautiful Holocaust survivor and her jazz-drummer husband.

Karen narrates and draws the story, depicting herself as a werewolf in a detective's trenchcoat and fedora, as she tries to unravel the secrets kept by the grownups around her. Karen's life is filled with mysteries, from the identity of her father (her brother, a talented illustrator, has removed him from all the family photos and redrawn him as the Invisible Man) to the purpose of a mysterious locked door in the building's cellar.

But the most pressing mystery of all is the death of her upstairs neighbor, the beautiful Annika Silverberg, a troubled Holocaust survivor whose alleged suicide just doesn't add up, and Karen – who loved and worshiped Annika – is determined to get to the bottom of it.

Karen is tormented by the adults in her life keeping too much from her – and by their failure to shield her from life's hardest truths. The flip side of Karen's frustration with adult secrecy is her exposure to adult activity she's too young to understand. From Annika's cassette-taped oral history of her girlhood in an Weimar brothel and her escape from a Nazi concentration camp, to the sex workers she sees turning tricks in cars and alleys in her neighborhood, to the horrors of the Vietnam war, Karen's struggle to understand is characterized by too much information, and too little.

Ferris's storytelling style is dazzling, and it's matched and exceeded by her illustration style, which is grounded in the classic horror comics of the 1950s and 1960s. Characters in Karen's life – including Karen herself – are sometimes depicted in the EC horror style, and that same sinister darkness crowds around the edges of her depictions of real-world Chicago.

These monster-comic throwbacks are absolute catnip for me. I, too, was a monster-obsessed kid, and spent endless hours watching, drawing, and dreaming about this kind of monster.

But Ferris isn't just a monster-obsessive; she's also a formally trained fine artist, and she infuses her love of great painters into Deeze, Karen's womanizing petty criminal of an older brother. Deeze and Karen's visits to the Art Institute of Chicago are commemorated with loving recreations of famous paintings, which are skillfully connected to pulp monster art with a combination of Deeze's commentary and Ferris's meticulous pen-strokes.

Seven years ago, Book One of My Favorite Thing Is Monsters absolutely floored me, and I early anticipated Book Two, which was meant to conclude the story, picking up from Book One's cliff-hanger ending. Originally, that second volume was scheduled for just a few months after Book One's publication (the original manuscript for Book One ran to 700 pages, and the book had been chopped down for publication, with the intention of concluding the story in another volume).

But the book was mysteriously delayed, and then delayed again. Months stretched into years. Stranger rumors swirled about the second volume's status, compounded by the bizarre misfortunes that had befallen book one. Last winter, Bleeding Cool's Rich Johnston published an article detailing a messy lawsuit between Ferris and her publishers, Fantagraphics:

https://bleedingcool.com/comics/fantagraphics-sued-emil-ferris-over-my-favorite-thing-is-monsters/

The filings in that case go some ways toward resolve the mystery of Book Two's delay, though the contradictory claims from Ferris and her publisher are harder to sort through than the mysteries at the heart of Monsters. The one sure thing is that writer and publisher eventually settled, paving the way for the publication of the very long-awaited Book Two:

https://www.fantagraphics.com/products/my-favorite-thing-is-monsters-book-two

Book Two picks up from Book One's cliffhanger and then rockets forward. Everything brilliant about One is even better in Two – the illustrations more lush, the fine art analysis more pointed and brilliant, the storytelling more assured and propulsive, the shocks and violence more outrageous, the characters more lovable, complex and grotesque.

Everything about Two is more. The background radiation of the Vietnam War in One takes center stage with Deeze's machinations to beat the draft, and Deeze and Karen being ensnared in the Chicago Police Riots of '68. The allegories, analysis and reproductions of classical art get more pointed, grotesque and lavish. Annika's Nazi concentration camp horrors are more explicit and more explicitly connected to Karen's life. The queerness of the story takes center stage, both through Karen's first love and the introduction of a queer nightclub. The characters are more vivid, as is the racial injustice and the corruption of the adult world.

I've been staring at the spine of My Favorite Thing Is Monsters Book One on my bookshelf for seven years. Partly, that's because the book is such a gorgeous thing, truly one of the great publishing packages of the century. But mostly, it's because I couldn't let go of Ferris's story, her characters, and her stupendous art.

After seven years, it would have been hard for Book Two to live up to all that anticipation, but goddammit if Ferris didn't manage to meet and exceed everything I could have hoped for in a conclusion.

There's a lot of people on my Christmas list who'll be getting both volumes of Monsters this year – and that number will only go up if Fantagraphics does some kind of slipcased two-volume set.

In the meantime, we've got more Ferris to look forward to. Last April, she announced that she had sold a prequel to Monsters and a new standalone two-volume noir murder series to Pantheon Books:

https://twitter.com/likaluca/status/1648364225855733769

If you'd like an essay-formatted version of this post to read or share, here's a link to it on pluralistic.net, my surveillance-free, ad-free, tracker-free blog:

https://pluralistic.net/2024/06/01/the-druid/#oh-my-papa

167 notes

·

View notes

Text

Biggest galaxy brain moment from visiting the Dune dunes is that it gave me a whole new perspective on why the terraforming of Arrakis is treated with such deep ambivalence by the text. Because the terraforming process that's described in great detail in the book? That's exactly what's happening to the Oregon dunes. And they're disappearing.

At the beginning of the 20th century, the open sand you see in this picture stretched all the way to the Pacific Ocean, which is visible here as a faint blue-gray line about halfway up the photo. The sea washed new sand ashore, and the seasonal wind cycles blew it into a constantly-shifting landscape of dunes, tree islands, ghost forests and both permanent and ephemeral lakes and rivers.

As European colonization of the Pacific Northwest grew, the new settlers and the logging and commercial fishing industries they brought with them wanted permanent towns and roads that weren't constantly being swallowed by the moving sand. Starting in the 1930s, European beachgrass and other non-native species were introduced to try to hold the dunes in place.

The invasive species did hold the dunes in place--too well. The deep roots of the beachgrass shaped the sand blowing in off the beach into a permanent dune parallel to the ocean, called the foredune.

As the foredune got taller, it blocked both wind and the movement of sand, which allowed the land behind it to become grassland...

then forest.

Walking through this area, you might never know there was a dune under your feet. You can be close enough to hear the ocean, but there is almost NO wind--the main force that shapes the dunes.

There are (slow, difficult) remediation efforts underway to control the European beachgrass and restore at least some of the area to the natural dune cycle that created the miles and miles of open sand. But the ecological feedback loop created by introducing the beachgrass is stubborn, and without any further intervention, the dunes could be completely covered with forest in as little as a few decades. (I've heard estimates from 50 to 150 years, both of which are a blink of an eye in geological timescales.) The Oregon dunes are at least 100,000 years old, and within the span of just a few human lifetimes the ecosystem could be irrevocably changed.

The dune stabilization project is what Frank Herbert came to Florence to research for a never-written magazine article. Herbert began writing Dune in the mid-1950s, but by the mid-60s when the book was published, his own politics had shifted as he was influenced by the growing environmental movement and by Native activism happening around him in the Pacific Northwest. Like the story of the Oregon dunes, the terraforming of Arrakis is initially promoted as triumph of science and human rationality over nature that will make people's lives easier. But it ends up destroying the native ecosystem and the way of life of the planet's indigenous people, as becomes clear in Dune Messiah when Paul actually implements the terraforming project. (In the book, Dr. Kynes, the main architect of the terraforming project, dies in a spice blow--literally swallowed whole by the planet he tried to control.) It's one of the many political/ideological tensions in the story that's presented but not resolved, and I'm super curious to see how this element of the story is handled in Villeneuve's Dune Messiah.

All photos above taken by me at the Oregon Dunes National Recreation Area in September 2024.

137 notes

·

View notes

Text

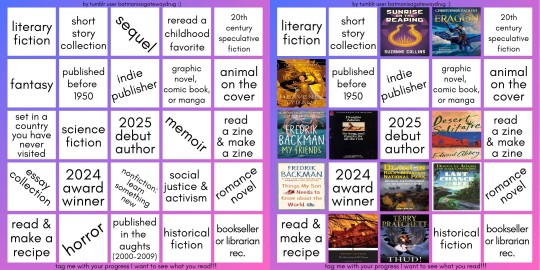

2025 Book Bingo!!

My dearest @batmanisagatewaydrug issued this challenge and here I am listing the books I intend to read in 2025! Under a read more because I'm not a monster

Literary Fiction: Our Share of Night (2019) by Mariana Enríquez, trans. Megan McDowell

Short Story Collection: Alien Sex: 19 Tales by the Masters of Science Fiction and Dark Fantasy (1990), edited by Ellen Datlow

A Sequel: Don’t Fear The Reaper (2023) by Stephen Graham Jones

Childhood Favorite: When You Reach Me (2009) by Rebecca Stead

20th Century Speculative Fiction: The Time of the Ghost (1981) by Diana Wynne Jones

Fantasy: To Shape a Dragon’s Breath (2023) by Moniquill Blackgoose

Published Before 1950: Wuthering Heights (1847) by Emily Brontë

Independent Publisher: Creatures of Passage (2022) by Morowa Yejidé, published by Akashic Books

Graphic Novel/Comic Book/Manga: Something is Killing the Children Book One (2021), by James Tynion IV, art by Werther Dell’Edera

Animal on the Cover: Coyote Rage (2019) by Owl Goingback

Set in a Country You Have Never Visited: Let the Right One In (2004) by John Ajvide Lindqvist, trans. Ebba Segerberg

Science Fiction: Finna (2020) by Nino Cipri

2025 Debut Author: Needy Little Things (2025) by Channelle Desamours

Memoir: Camgirl (2019) by Isa Mazzei

Read a Zine, Make a Zine: Leaving this one blank for now! If anyone has any zine recommendations I'd love to hear them!

Essay Collection: Unquiet Spirits: Essays by Asian Women in Horror (2023), edited by Lee Murray and Angela Yuriko Smith

2024 Award Winner: Linghun (2023) by Ai Jiang, winner of the Bram Stoker Award for Superior Achievement in Long Fiction

Nonfiction: Learn Something New: Abominable Science! Origins of the Yeti, Nessie, and Other Famous Cryptids (2012) by Daniel Loxton and Donald Prothero

Social Justice & Activism: Fearing the Black Body: The Racial Origins of Fat Phobia (2019) by Sabrina Strings

Romance Novel: Such Sharp Teeth (2022) By Rachel Harrison

Read and Make a Recipe: The Sopranos Family Cookbook: As Compiled by Artie Bucco (2002), by Allen Rucker, David Chase, and Michele Scicolone

Horror: SOUR CANDY (2015) by Kealan Patrick Burke

Published in the Aughts: Abandon (2009) by Blake Crouch

Historical Fiction: The Hacienda (2022) by Isabel Cañas

Bookseller or Librarian Recommendation: Leaving this one blank for now as well! If any booksellers or librarians want to recommend me a book so I don't have to talk to someone in real life. I'd love that.

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

Book 2 for 2025 book bingo! For the "Published Before 1950" square (so many options! I love to read older books!) I selected the original "The Adventures of Pinocchio" (1883), translated by Carol Della Chiesa in 1926.

All I knew about this book was that it was different from the Disney movie, and that instead of the wise and friendly Jiminy Cricket as Pinocchio's conscience, there's a talking cricket that tries to advise Pinocchio until Pinocchio smashes him to death with a hammer. (I think Stephen King mentioned this in something of his--maybe "Danse Macabre"?). So I wasn't really at risk of tonal whiplash.

As promised, this is a pretty dark story--Pinocchio is mostly a pure chaos agent, kind of like Curious George except with violence and death, plus always someone looking to trick/prey on/take advantage of you. The narrator delivers morals, but for most of the book they come across (to me, at least, in translation and from my different historical context) as brightly tongue-in-cheek, since once a moral gets set out, Pinocchio generally smashes right through it. He's not malicious per se, but he is entirely impulsive and only does what he wants to do, and then cries about it afterward in self-pity once he has Fucked Around And Found Out. Then he gets rescued somehow, and heads back into the FAFO cycle.

I enjoyed the Fox-and-Cat sections, because of the difference between what Pinocchio knows, how the narrator describes things, and what we as readers (if we can get the hang of unreliable narration) know. They're con artists, they have unacknowledged cover stories and nefarious plans, while Pinocchio (and the narrative) is taking them entirely at their word. I can't remember when I first learned to navigate narrative unreliability in my own childhood reading, but I definitely came to love that feeling.

The last section of the book feels different--the stated morals start feeling more serious, and Pinocchio starts doing kind and positive things without being forced to. That means the sense of humor changes too--it kind of filters away, as does the sharp irony and the layers of unreliability. And a few earlier events get softened--like, the Talking Cricket reappears toward the end of the book without any explanation, scolds Pinocchio for the hammer thing, delivers a sententious moral, and Pinocchio apologizes and agrees with him. Definitely different than the Pinocchio of the earlier sections. (Although interestingly, Pinocchio may have Plot Armor, but even once the book has gentled a bit, other characters still die--like, Lamp-Wick, someone who convinced Pinocchio to misbehave, doesn't get rescued from being turned into a donkey the way Pinocchio was rescued. He's bought and then worked to death, and dies in a sad on-page scene.)

I read more about the book afterward and found out it was originally a magazine serial, so it all makes perfect sense, the episodic nature and the tone change and whatnot. Wikipedia also said that the serial originally ended fairly early on, when Pinocchio is punished by being hanged by the neck from a tree and dies (whereas in the book he's hanged and almost dies but is rescued). (Man, my childhood books were never like this.)

It really benefited Collodi to start up again with a fixit, given how popular the happy-ending book version became all over the world. It's hard to imagine a dead-at-the-end version becoming as beloved in places like the U.S.--at least in my sense of children's literature at that time, it wouldn't have much room for such a pitch-black tone.

@batmanisagatewaydrug

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

2025 Book Bingo Plans

I've started planning out some of what I'm going to read for @batmanisagatewaydrug's 2025 book bingo (read more here), and to get myself hyped, I'm sharing the books I've set in stone, as well as recording some ideas I have for the other spaces!

I've been looking forward to Sunrise on the Reaping by Suzanne Collins for a while now, I'm interested to see if it will live up to the philosophical examination it sets itself up as.

I got the illustrated copy of Eragon by Christopher Paolini/Sidharth Chaturvedi for Christmas, so that's kind of a no-brainer for the re-read.

Heavenly Tyrant by Xiran Jay Zhao I'm also getting for Christmas, but it's the pretty Illumicrate version, so it's not getting here until January or February. I took a gamble with Iron Widow and got the hardcover, and I was not disappointed (I've read it 3 times and am going to reread it once I get HT, and will certainly reread both in the future), so I expect the fancy one will be money well spent (by my aunt but still).

I am just assuming that My Friends by Fredrik Backman is going to be set in Sweden, because all of Backman's other novels are set there. Hopefully I don't need to find a new book for the category lol. If I do this one will probably fit Literary Fiction anyway.

I've been working my way through my reread of the Hitchiker's Guide trilogy by Douglas Adams, and think I can finish the 3rd in the next few days, so I'm all set up for the 4th going into 2025 :)

I stopped reading Desert Solitaire by Edward Abbey when school got really rough last year and have wanted to go back to it for a while. It was recommended to me by my dad, and one of his favorite books. In the 100-ish pages I've read, I've found it to be amazing as well.

Things My Son Needs to Know About the World by Fredrik Backman was going to be my memoir choice until I realized it was actually essays.

I saw Death In Rocky Mountain National Park: Accidents and Foolhardiness on the Continental Divide by Randi Minetor while just wandering Barnes and Noble and was sure I had to read it when the title made it clear it wasn't going to blame animals for the actions of humans.

I've wanted to read Last Chance to See by Douglas Adams and Mark Carwardine for a long time, but the concept alone has always made it a little too sad to convince myself to pick up. This year will be its year though.

I promised my roommate that I would read The Haunting of Hill House by Shirley Jackson last year so that we could watch the show for Halloween. I'm following through this year instead.....

My reasoning for Thud! by Terry Pratchett is simple. I like Discworld, I like Ankh Morpork, I like the Watch novels, I like Sam Vimes.

Below the cut are some of my ideas for the sections I haven't filled yet (anyone should feel free to send me as many recommendations for these as you want):

Literary Fiction:

All The Names by José Saramago (recommended by my dad)

The Summer Book by Tove Jansson (recommended by my roommate)

Short Story Collection:

And Every Morning The Way Home Gets Longer and Longer, The Answer is No, and The Deal of a Lifetime by Fredrik Backman (this is not technically a collection, but it is a group of short stories that I really want to read)

20th Century Speculative Fiction:

The Martian by Andy Weir (I just want to read it)

Published Before 1950:

TBD Agatha Christie novel (I stole my dad's books acquired a lot of these and want to read some)

Indie Publisher:

Something from this list

Graphic Novel, Comic Book, or Manga:

Nothing Special by Katie Cook (I read this on Webtoon as it's been coming out, it has some of the best panel transitions on the platform, and I really want to see how she translated that to book form. Also I want to own the books bc I love the story and refuse to pay Webtoon money for it)

Animal On the Cover:

A Lady's Life in the Rocky Mountains by Isabella Bird (I was looking at the "local" shelf (not at this book in particular though) in Barnes and Noble, and a woman (not an employee) came up to me to tell me this is one of her favorite books ever and now I must read it)

The Girl in Red by Christina Henry (I help run a blog here cataloguing books with little to no romance and/or sex in them for people who are sex/romance repulsed, and someone submitted this. I also read a book years ago that I loved, but I didn't have Goodreads even at that point, and all I really remembered was the cover and opening. I've been looking for a while, and I think this very well could be it)

City of Nightmares by Rebecca Schaeffer (I loved her Market of Monster's trilogy and the Webtoon adaptation, and have been meaning to read this for ages)

Descendent of the Crane by Joan He (recommended by my other roommate, plus I liked her book The Ones We're Meant to Find)

Going Postal by Terry Pratchett (re: the reasons for Thud!)

2025 Debut Author:

Honestly, no clue here. I'll cross that bridge when I come to it

Read a Zine and Make a Zine:

Scarland fanzine by a whole bunch of people (I've read it before but it's really quite amazing and I would read it again happily)

2024 Award Winner:

Something on this list

Romance Novel:

Just Last Night by Mhairi McFarlane (recommended by a friend whose judgement in books I really trust)

Read and Make a Recipe:

We will see what strikes my fancy this year

Historical Fiction:

Fever 1973 by Laurie Halse Anderson (this one has been on my TBR since 2015)

The Island of the Sea Women by Lisa See (this was a birthday present in 2019)

Babel by R.F. Kuang (the premise is cool, and it says it's a response to The Secret History and I loved that book)

Bookseller or Librarian Rec:

Because of Mr. Terupt by Rob Buyea (in 5th grade, we did a unit where the class was split into 3rds and we each analyzed 1 book. The kids who read this book loved it. I really wanted to read it then, but never did. Then in 8th grade a librarian recommended it to me, bringing it back to my memory, but I still didn't read it. It lives on my TBR because I feel like I need to read it for 10/13 year old me)

#neon's void#2025 book bingo#the hunger games#the inheritance cycle#heavenly tyrant#fredrik backman#the hitchhiker's guide to the galaxy#desert solitaire#Death In Rocky Mountain National Park: Accidents and Foolhardiness on the Continental Divide#last chance to see#the haunting of hill house#discworld

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

2025 book bingo tbr

i'm gonna be following the 2025 book bingo created by the magnanimous @batmanisagatewaydrug and i have just completed (to the extent i can today) my tbr! (this has also inspired me into making a list of 25 things i need to do 25 times throughout 2025... so if there's one thing i will be next year, it is occupied). i drew from books that i own/my roommate owns as much as possible.

Literary Fiction: Luster by Raven Leilani (which has been on my libby holds list since mackenzie last recommended it. abt 20 weeks to go).

2. Short Story Collection: Cursed Bunny by Bora Chung, translated by Anton Hur (advanced reader's copy i got for free from my college's book club)

3. A Sequel: A Day of Fallen Night by Samantha Shannon

4. Childhood Favorite: The Sword of Darrow by Alex and Hal Malchow or Heidi by Johanna Spyri or something i find when i am home for the holidays that calls my soul more than these two

5. 20th Century Speculative Fiction: The Silmarillion by J. R. R. Tolkein (because TECHNICALLY it counts)

6. Fantasy: Piranesi by Susanna Clarke (one of the few remaining Book of the Month editions i still own)

7. Published Before 1950: Spoon River Anthology by Edgar Lee Masters, published in 1915

8. Independent Publisher: I Love Information by Courtney Bush, published by Milkweed Editions (will need to either get over my fear of going to the library in person to set up my online account and put a hold on this OR purchase a copy)

9. Graphic Novel/Comic Book/Manga: Fun Home by Allison Bechdel or Saga by writer Brian K. Vaughan and artist Fiona Staples, have not decided (both owned by my roommate)

10. Animal on the Cover: Diminished Capacity by Sherwood Kiraly (he was my playwriting/fiction professor and gave me my copy of the novel)

11. Set in a Country You Have Never Visited: Euphoria by Lily King, set in New Guinea (owned by my roommate)

12. Science Fiction: Dirk Gently's Holistic Detective Agency by Douglas Adams

13. 2025 Debut Author: Julie Chan is Dead by Liann Zhang, expected May 2025 (another physical hold or purchase situation)

14. Memoir: Reading With Patrick by Michelle Kuo (commencement speaker at my graduation!)

15. Read a Zine, Make a Zine: tbd! will probably be more than one!

16. Essay Collection: The Book of Difficult Fruit by Kate Lebo

17. 2024 Award Winner: How to Say Babylon by Safiya Sinclair, NBCC Award for Autobiography (will borrow from libby, audiobook is also available)

18. Nonfiction: Learn Something New: I was paying more attention to the nonfiction part than the learn something new part and i do need to find a new book for this because originally i was gonna go with one of Caitlin Doughty's novels which, while lovely, are not something New To Me. i know i have a biography of Anna Freud somewhere so maybe i will dig that up? otherwise it might be a scroll-through-libby adventure

19. Social Justice & Activism: The Theater of War by Bryan Doerries (read a few chapters first year of undergrad but never the whole thing so technically it counts as a new book for me)

20. Romance Novel: Once Upon a Broken Heart by Stephanie Garber

21. Read and Make a Recipe: Jane Austen's Table by Robert Tuesley Anderson, specific recipe to be determined upon reading

22. Horror: Flowers in the Attic by V. C. Andrews (owned and recommended by my roommate as a good option for me, because i do not do well with horror. respect the genre so much!! but my anxiety disorder)

23. Published in the Aughts: Throne of Jade by Naomi Novik (just got my thrift books copy a couple weeks ago. i am making myself SAVOR this series)

24. Historical Fiction: Water for Elephants by Sara Gruen

25. Bookseller or Librarian Recommendation: tbd upon getting over my fears and actually visiting my library in person! it's a five minute walk from my apartment i do not know what my problem is

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

i love the one-upmanship of the early contactee movement because for a while they'd be publishing books and it'd be like

1949, book called Flying Saucers, I Heard Of 'Em 1950, book called I Personally Saw A Flying Saucer 1951, I Touched A Flying Saucer 1952, Well The Occupants Of A Flying Saucer Talked To Me! 1952 later, Oh Yeah? The Flying Saucer Took Me For A Joyride 1953, The Saucer Occupants Took Me To Their World In A Flying Saucer And I Lived There For A While And Their Food Was Great and They Were Kinda Communist But I'll Say They Weren't And Then They Gave Me Keys To My Own Saucer But I Lost It Because Atomic Weapons Exist

and then you'll get the random ones that are like.

1954: The Flying Saucer Took Me To Hell And It Was Scawy :c

90 notes

·

View notes

Note

Sorry if this is a bit weird question but would artistic freedom be restricted in a socialist state? If it would be, how? Wouldn't restrictions/censorships be a bad thing since it's important for people to be able to learn critical thinking skills and criticize in a constructive way a government or other aspects of society or for them to just depict with reality and imagination in a way that leads to diverse conversations?

The degree of restriction always depends on the context of the state, it's not a set answer. Like most other questions regarding the running of a state by communists, it will change depending on necessities and as it evolves. But regardless, art will always be free of the pressures imposed by salary work, and across the history of socialism, there is a good precedent for ample subsidies of the arts, even those not directly related to socialism itself.

Look at this passage about the GDR, for instance. Take into account the historical context, of a country that has just been divided and liberated from the Nazi Party, with the mass support they garnered. The FRG wasn't exactly unwelcoming to former nazis, even important members of the party, and the GDR was the frontline for the cold war, during its entire existence it faced infiltration, sabotage, and a myriad of attacks against it. [Because of indented quotes being awkward for longer texts, I'm not going to format it differently. The quote will end with the link to the book it's from]

During the forty years of its existence, a unique GDR culture developed in the country and it differed substantially from that in the West. It was characterised by a very fruitful, even if at time bruising and sometimes painful, battle between artistic freedom and creativity on the one hand and the demands the Party and state attempted to impose.

Since the early days of the Soviet Union, the Bolsheviks and later communist parties everywhere placed a great emphasis on culture and on the contribution cultural workers could make to the building of socialism. One of the first things the Soviet Army of occupation did at the end of the war, was attempt to resuscitate cultural activity in a war-ravaged and demoralised Germany. The one thing the Russians could never get their head around was how a country with such a high level of culture, a nation that had produced a Bach and a Beethoven, a Goethe and a Schiller could have carried out such barbaric crimes in other countries. The Soviet army had cultural officers attached to each battalion and the war had hardly ended before they began seeking out cultural workers and encouraging them to take up their batons, musical instruments, pens and paintbrushes again. Temporary cinemas were established, orchestras formed, theatres opened and publishing houses set up.

In contrast to West Germany, in the Soviet Zone and later in the GDR, there was also an early emphasis on making films about the Nazi period as a means of educating and informing a nation ignorant of or in denial about what had happened.

The first anti-Nazi and anti-war film to be made in the whole of Germany was Die Morder sind unter uns (Murderers among us - 1946) directed by the West Berlin-based Wolfgang Staudte with full Soviet support. Among later anti-Nazi films made in the GDR were: Rat der Gotter (Council of the Gods - 1950) about the production of poison gas by IG Farben for the concentration camps, Nackt unter Wolfen (Naked amongst Wolves - 1963), based on a true story about a small Jewish boy who was hidden in a concentration camp and thus saved. Werner Holt (1965) - about the life of young men in Hitler’s army, Gefrorene Blitze (Frozen Flashes -1967) about the development of the V2 rocket by the Nazis; Ich war Neunzehn (I was Nineteen - 1968) - the true story of a young German who returns to Germany in the uniform of a Red Army soldier with the victorious Russian troops. Almost two decades passed before West Germany attempted to confront the war and its Nazi past. And the film Das Boot (1981) is more about the heroics of German U-boat crews than about understanding Nazi ideology. Das schreckliche Maedchen (Nasty Girl -1990) was a rare exception, as was Downfall (2004), a film about Hitler.

The GDR had more theatres per capita than any other country in the world and in no other country were there more orchestras in relation to population size or territory. With 90 professional orchestras, GDR citizens had three times more opportunity of accessing live music, than those in the FRG, 7.5 times more than in the USA and 30 times more than in the UK. It also had one of the world’s highest book publishing figures. This small country with its very limited economic resources, even in the fifties was spending double the amount on cultural activities as the FRG.

Every town of 30,000 or more inhabitants in the GDR had its theatre and cinema as well as other cultural venues. It had roughly half as many theatres as the Federal Republic, despite having less than a third of the population (178 compared with 346 in the FRG). Subsidised tickets to the theatre and concerts were always priced so that everyone could afford to go. Many factories and institutions had regular block-bookings for their workers which were avidly taken up. School pupils from the age of 14 were also encouraged to go to the theatre once a month and schools were able to obtain subsidised tickets. All the theatres had permanent ensembles of actors who received a regular salary. Plays and operas were performed on a repertory basis, providing everyone in the ensemble with a variety of roles.

All towns and even many villages had their own ‘Houses of Culture’, owned by the local communities and open for all to use. These were places that offered performance venues, workshop space and facilities for celebratory gatherings, discos, drama groups etc. There was a lively culture of local music and folk-song groups, as well as classical musical performance.

Very different to the situation in West Germany, was the widespread establishment in the GDR of workers’ cultural groups - from literary circles, artists groups to ceramic and photography workshops. These were actively encouraged and financially supported by the state, local authorities or the workplace. Discussions of books and literature, often together with authors, were a regular occurrence, even in the remotest of villages.

The ‘Kulturbund’ (Cultural Association) was a national organisation of over one million members that organised a wide range of cultural events around the country, from concerts, lectures on a wide variety of subjects, to art appreciation classes.

To begin with it was set up in set up in 1945 as a movement to bring together interested intellectuals and artists, on the basis of an anti-fascist and humanist outlook, with the aim of promoting a ‘national re-birth’ and ‘of regaining the trust and respect of the world’. From 1949 onwards many smaller cultural groups joined the national Cultural Association. Soon, ‘commissions’ and ‘working groups’ for specific areas were established: educational, musical, architectural and craft groups, followed by photographic, press, philatelic, fine arts groups and others. The Association also had its own monthly journal and weekly newspaper.

The art form ‘Socialist Realism’ has always been decried and ridiculed in the West, caricatured in the constantly circulated images of monumental statues of muscle-bound male workers and buxom, peasant women in heroic poses. However, such a view ignores those many realist artists who were not necessarily ‘court-appointed’ or monumentalists but who chose a realist mode of expression freely.

We now know that the CIA was, at the height of the Cold War, instrumental in promoting abstract art in the West as a counterweight to ‘communist’ realism. The CIA was able to capitalise on the fact that abstract art was frowned upon by party leaderships throughout the communist-led world where realist art was seen as better able to represent socialist values. This led to an often artificial polarisation between realist and abstract art, the former characterised in the West as old fashioned and conservative, the latter as progressive and representing individual freedom. Not surprisingly, it meant a marginalisation of realist art in the West and a dominance of the abstract. The fact that much of the so-called ‘socialist realist’ art to which those in the West had access was state-commissioned and often second rate should not lead us to ignore the fact that there were excellent realist artists working in the Eastern bloc.

Many artists in the communist countries simply preferred to place human beings and social reality at the centre of their art, as did most muralists and many painters in the West. It should not condescendingly be dismissed out of hand. Many continued the strong realist tradition, taking it forward into new realms. It also connected with ordinary people who saw themselves, their lives and their questions and criticisms taken up by artists. While some conformed and became state-sponsored artists, churning out often mediocre art, many others ploughed their own furrow and their work aroused avid interest among the people. This could be seen not only in painting and sculpture but graphics, the theatre, music, literature and, though less so, also in the cinema.

A number of artists did reject the unnecessary ideological fetters as well as banal socialist realist platitudes, and in exhibitions of their work often shocked the party functionaries. Such artists often promoted a progressive and expressively advanced form of critical realism and an aesthetics of their own making. The national contemporary art exhibitions, which took place every five years in Dresden, drew huge numbers of visitors from all over the country and provoked heated discussions. The country could also boast a number of artists, writers and scientists of international renown: the physicist, Manfred von Ardenne, the social scientist, Jurgen Kuczynski; visual artists like Fritz Kuhn, John Heartfield, Willi Sitte, Werner Tiibke and Wolfgang Mattheuer; writers like Christa Wolf, Stefan Hermlin, Stefan Heym,

Christoph Hein, Erik Neutsch and Erwin Strittmatter were all much admired beyond the GDR’s borders.

In the theatre, Bertolt Brecht was, of course, the most famous. His influence on theatre practice was extensive in the GDR but also worldwide. The country, certainly in the early years, could also count on the expertise of actors and directors from the pre-Nazi period: Wolfgang Langhof, Wolf Kaiser, Wolfgang Heinz, Fritz Bennewitz and the brilliant Austrian opera director, Walther Felsenstein - people would come from all over the world to see his exciting productions at the Komische Oper in East Berlin. Among those who matured post-war, Heiner Muller was widely recognised as one of Germany’s most innovative and radical playwrights. There were rock and pop bands like Silly and the Puhdys and jazz groups who were certainly not ‘mouthpieces’ of state-sanctioned culture. There was also a whole range of individual classical musicians of world class, like the conductor Kurt Masur, tenor Peter Schreier and baritone Olaf Bar, the chanteuse Gisela May as well as outstanding orchestras.

The GDR provided facilities and funding for artistic and creative theory and practice. There were lay art circles in most communities and these received state support to carry out their work. Many writers, musicians and visual artists enjoyed a quite privileged existence if they belonged to the officially recognised artists’ or writers’ associations. They would be offered regular well-paid commissions by state and local authorities which provided them, as creative artists, with an income to live on.

A number of leading writers were seen in many ways as ‘people’s tribunes’, articulating grievances, criticisms and ideas that people felt had no proper airing in the public sphere. People engaged actively with these writers and vice versa. Public readings by, and discussions with, authors were a regular feature of GDR life.

Another myth constantly perpetuated is that because the GDR restricted the import of and access to literature from the West, its citizens were entirely cut off from it. A range of works from many contemporary writers from the West were published in the GDR; in fact more British authors were published there than authors from both Germanies combined were published in Britain. GDR readers could find books by British writers like Graham Greene and Alan Sillitoe to US writers like Saul Bellow, Norman Mailer and Ernest Hemingway. By 1981, the GDR was publishing 6,000 books a year, almost 17 per cent of which were translations from around 40 foreign languages. There was a wide selection of international literature available and a number of foreign films were shown in cinemas. David Childs, in his book on East Germany, exposes the myth that the GDR populace was totally ignorant and ill-informed about life in the West; most of them, after all were also able to tune in daily to West German radio and television.

Stasi State or Socialist Paradise?: The German Democratic Republic and What Became of It, by John Green and Bruni De La Motte (2015)

The GDR's relationship to art censorship wasn't as black and white as allowing and disallowing. Certain types of art were discouraged, but they also let regular exhibitions happen which contained "shocking" art, shocking for the party members. They were justifiably weary of any art coming from the west because they knew the CIA used it as a weapon, but "more British authors were published there than authors from both Germanies combined were published in Britain". The social conditioners of art also show themselves in socialist states. Just like liberal art in capitalist countries doesn't really need to be actively encouraged to exist, some artists in the GDR "simply preferred to place human beings and social reality at the centre of their art". It's a complex question which, like I said, almost entirely depends on the historical moment.

110 notes

·

View notes

Text

So you want to know about Oz! (1)

Then congratulations! Welcome to this quick crash course to know everything about the world of Oz! The movies, the adaptations, the musicals, the books! Yes, books, with an S, because "The Wizard of Oz" everybody knows and love was just the first book of an entire BOOK SERIES that became the enormous franchise we know today! You thought there was just ONE Wizard of Oz movie? Think again! You thought "Wicked" was the only work that gave a backstory to the Witches? Get ready for some discoveries!

And so we begin our journey to the wonderful land of Oz...

The story of Oz begins with one novel. No, not one movie - but the novel that caused the movie... L. Frank Baum's "The Wonderful Wizard of Oz"

Published in 1900, this children novel is still to this day one of the most famous works of American youth literature, as well as the master-piece of Baum, THE book everybody knows he wrote. Baum intended, with this book, to create a purely American fairy tale: he wanted to rival the European tales of Charles Perrault, the brothers Grimm or Hans Christian Andersen - and he succeeded! The novel was a best-seller as soon as it was released, and is still considered as "America's greatest fairy-tale".

Most people know of "The Wizard of Oz" through its famous adaptation, the 1939 musical movie. While these two works do share a same set of main characters and a similar plot, the novel contains many, many details that were not adapted into the movie ; and, in return, the movie brought a lot of elements that were absent from the novel. Both, however, are still the story of a little girl by the name of Dorothy (she wasn't yet named "Gale") and her dog Toto, who are swept up into a tornado and taken to the magical Land of Oz. There she meets three comical companions (the Scarecrow, the Tin Man, the Cowardly Lion), and together they go seek the Wizard of Oz in hope he can grant their wishes, only to have to escape from the clutches of the Wicked Witch of the West...

If you want to read the original novel, it will be very easy! Not only is it still regularly printed today, with various anniversary editions ; but it is in public domain since the 1950s! So you can go read it for free right now, without any problems!

Most people tend to stop at just this book... Not wondering if there was any sequel, treating it as if this was just a one-shot. Except, we told you, this book was a best-seller! An ENORMOUS success! Never before had a children's book brought so much money in the United-States! As such, Baum was not going to just stop there...

While he did intent "The Wonderful Wizard of Oz" to be a self-contained novel existing as its own thing, in 1904 he published a sequel "The Marvelous Land of Oz":

This novel does not follow Dorothy however, but rather a very different character... A little boy who lives in the Land of Oz post-Dorothy: Tip (short for Tippetarius), an orphan boy who escapes the clutches of his wicked witch of a caretaker alongside a pumpkin-headed scarecrow he just brought to life. And the two undergo a journey to the Emerald City ruled by the Scarecrow-king, only to get swept into a revolution...

This novel was conceived in a similar way to the first one, as a "self-contained" story. While it does take place after the events of "The Wonderful Wizard of Oz", reuses several of the same characters (The Scarecrow and the Tin Man are part of the main party, Glinda plays a key part in the final act) and briefly recaps the events of the first novel, it can still be read on its own. This novel especially get a lot of attention today (after decades and decades of falling into pur oblivion) due to its fantasy-dissection of the topics of genders - differences between men and women, boys and girls, unfairness and injustice among sexes (the revolution in question is a "girl revolution" seeking to destroy what is perceived as a misogynistic patriarchy)... All culminating with what is still to this day one of the most famous accidental depictions of a trans character in fantasy!

But I'll return to this all in a later post, possibly...

This novel was ALSO a best-seller and a huge success. And as such... you know what that means. Yes, Baum wrote a THIRD book taking place in Oz! Well, almost... The novel actually mostly takes place in lands neighbors to those of Oz, the land of Ev and the realm of the Nome King... But all the Oz characters return - including Dorothy, who is again swept away into fairy-lands, this time not with her dog Toto, but with a pet chicken Billina.

This story is the novel "Ozma of Oz", published in 1907:

And with these three books, you have the original Oz trilogy!

"But wait, there were other Oz books, weren't there?" you ask. Oh yes, there were more books, indeed! However, I want to stop at this point because these three books do form a specific trilogy for various reasons. The trilogy of the "good" Oz books before everything went... let's say downhill (but more about that next post). But more importantly, the trilogy of Oz books most people know about!

Indeed, even if you have never read "The Marvelous Land of Oz" or "Ozma of Oz", you probably came across various elements of these books, that are regularly scattered throughout Oz adaptations and novels. For example the famous Disney movie "Return to Oz" is mostly an adaptation of "Ozma of Oz", but with numerous elements of "The Marvelous Land of Oz" added to the plot

More recently, the trilogy also formed the basis of the new plot offered by the short-lived TV series "Emerald City"!

Langwidere the princess with a hundred heads, Mombi the witch, Ozma the princess of Oz, the Nome king, Tik-Tok the automaton, Jack Pumpkinhead, general Jinjur, the land of Ev, the Powder of Life and many other names and concepts you might be familiar with come from these two direct sequels to "The Wonderful Wizard of Oz". Sequels which unfortunately never knew the lasting popularity of their predecessor, despite being just as famous, if not more, in their time...

Next post: Baum's downfall...

#oz#the wizard of oz#the wonderful wizard of oz#land of oz#the marvelous land of oz#l. frank baum#so you want to know about oz#oz books#oz novels#ozma of oz

80 notes

·

View notes