#iconographie photographique de la salpêtrière

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Iconographie photographique de la Salpêtrière

554 notes

·

View notes

Text

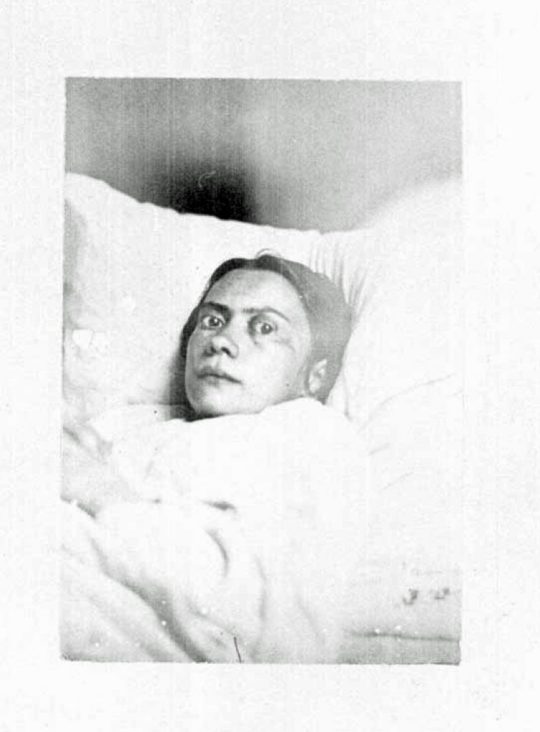

Blanche Wittman and PNES (Psychogenic Non-Epileptic Seizures)

Blanche Wittman, famed La Salpêtrière hysteric is the pinnacle of what the modern-day public thinks of when they imagine "female hysteria" that being young women institutionalized and used as entertainment. In fact, most of our modern understanding of what hysteria was comes from Jean-Martin Charcot's work on La Salpêtrière's hysterics, one of the most notable examples being Blanche Whittman, forever immortalized in photographs and of course the famous André Brouillet painting "Une leçon clinique à la Salpêtrière"

Her dramatized and public portrayal of hysteria has led to an increase in awareness of neurological and psychiatric conditions primarily effecting women, PNES (Psychogenic Non-Epileptic Seizures) which falls somewhere between psychiatric and neurological being one of these conditions, which seems a likely diagnosis for her if Blanche were to visit a modern neurology clinic.

What is PNES? PNES (Psychogenic Non-Epileptic Seizures) are seizure episodes that highly resemble that of an epileptic seizure, though no brain activity resembling epilepsy is present. These seizures have a psychological basis, instead of a neurological one, though neurological imaging may be used in diagnosis before treatment is turned over to a psychologist or psychiatrist.

Blanche Wittman's symptoms present in her public case information across volumes of "Iconographie photographique de la Salpêtrière" line up very well with the current diagnostic criteria of PNES.

When Blanche was first admitted into La Salpêtrière in 1877, she was 18 years old, 1.62 meters tall (considered above average in this period) and weighing in at 70kg. Being raised in a troublesome and poor family, she was never taught to read and her intelligence was labeled as being below average by the hospital.

As stated before, Blanche was raised in a troublesome family, having nine siblings, including five who died in childhood from epilepsy and convulsions. Her father was prone to "fits of rage" and physically abused the young Blanche in many instances, and her mother died when Blanche was young, though the exact age varies from source to source.

She began a sexual relationship with her employer, a furrier, by force at the age of 15. She then admitted herself to a hospital (unclear exactly where) to escape the abuse eight months after it began. A while later she reported another sexual relationship with a boy called Alphonse. It seems to be unclear whether this relationship was consented to by Blanche, or another example of sexual abuse against her.

Abuse, especially sexual is an extremely common background in those with PNES. A diagnosis of PTSD or C-PTSD with PNES is quite common. It seems extremely likely that her abuse she went through played a role in these "hysterical attacks"

After some time taking refuge at a convent (Blanche seems to have been a devout Catholic, wearing a scapular and collecting various pieces of Christian iconography) she began working as a servant at La Salpêtrière, thinking this would make it easier for her to be eventually admitted into the hospital after they see her attacks.

Blanche eventually succeeded in her goal of being admitted to La Salpêtrière in 1877, at the age of 18. Her time there coincided with the peak of Jean-Martin Charcot's studies on hysteria, and she quickly became one of his star patients. Charcot’s research focused on hysteria as a neurological disorder, and his methods of public "demonstrations" of hysterical patients, including Blanche, led to increased attention to the condition. These public displays, often featuring dramatic reenactments of symptoms, cast a long shadow over how hysteria and by extension, women’s health was perceived for decades.

Blanche’s displays of hysteria to the public were not only attended by a medical crowd, but was also popular among a non-medical crowd, including that of actors, who would come to study Blanche’s intense displays of emotion under hypnosis.

Hypnosis was frequently used on Blanche during these displays, often to achieve the state of somnambulism, or extreme suggestibility, where the hypnotist could make her to believe just about anything they so desired, the effects sometimes even lasting long after the trance.

While the primary purpose of these displays was supposedly to educate on hysteria, they often came off as more entertaining stage hypnosis than anything. Some of this was mindless entertainment, though some was clearly intended to use Blanche’s fear and distress for laughs, whether to the audience or the hospital staff themselves, often young male medical students, finding it hilarious to sexualize and upset her.

During her intense states of somnambulism, she was often made to hallucinate snakes and rats at her feet. She would hike up her skirt and squeal, prompting voyeuristic laughs from the audience.

Unlike the many “wandering womb” theories we often associate with hysteria today, Charcot was among the first who believed hysteria had a neurological origin, attributing symptoms like convulsions, paralysis, and loss of consciousness to issues within the brain. This makes sense as Charcot was most certainly extremely knowledgeable about neuroscience. In fact, he was the first to identify and name multiple sclerosis as it’s own distinct condition, pioneered much amyotrophic lateral sclerosis research (the disease even being known as Charcot’s disease in parts of the world) and is associated with at least 15 different diseases named after him. For this reason, it only makes sense that a condition with invisible physical pathology must be caused by nervous system abnormalities, this being even more apparent when remembering this was a time before complex brain imaging and EEG technology was in use, it was nearly impossible to know whether something was psychological or neurological, and Charcot believed the latter.

However, many of these symptoms would align more closely with what we now understand as psychogenic non-epileptic seizures (PNES), a condition rooted in psychological trauma rather than physical abnormalities in the brain. Today, PNES is understood as a dissociative disorder, often linked to past trauma, which manifests in seizure episodes without the electrical disruptions seen in epilepsy.

Before her time institutionalized, Blanche's life was full of trauma and abuse, often seen in PNES patients. Not only that but Blanche also demonstrated a good example of "the teddy bear sign" a frequent pattern in PNES patients and an aid in diagnosis. A majority of PNES patients show up to EEG monitoring appointments with a comfort item, most often a stuffed animal. While we don't know exactly what Blanche would have done in the modern day, we do know she was an avid collector of stuffed animals and various little trinkets. This was common behavior among hysterics, suggesting what in the modern day we would call PNES was common among hysterics.

The "hysterical attacks" that made her a spectacle were, in all likelihood, trauma responses—demonstrations of a mind and body deeply affected by abuse. While these days are long gone, it's important to see just how much this outdated understanding of the brain both holds back and progresses our knowledge of the connection between body and brain.

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Iconographie photographique de la Salpêtrière - Jean Martin Charcot (1878)

#iconographie photographique de la salpêtrière#neurology#science#chronophotography#science photography#jean martin charcot#hypnotism#neurosis#france#1878#1800s

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Iconographie photographique de la Salpêtrière (1876-80)

23 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Désiré-Magloire Bourneville and Paul Regnard, from Iconographie photographique de la Salpêtrière (Paris 1875)

The book contains a series of 120 photographs depicting patients (this one diagnosed with epilepsy) from the neuropsychiatric department of la Pitié-Salpêtrière, one of the largest hospitals in 19th-century Paris. It was one of the first medical studies addressing mental health to use photography rather than drawing/painting for illustrations.

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

(1982) GEORGES DIDI-HUBERMAN, LA INVENCIÓN DE LA HISTERIA

Este libro narra y cuestiona las prácticas en torno a la histeria que se llevaron a cabo en la Salpêtrière en época de Charcot. A través de procedimientos clínicos y experimentales, por medio de la hipnosis y las "presentaciones" de enfermas en estado de crisis (las célebres "lecciones de los martes"), descubrimos una especie de teatralidad estupefaciente, excesiva, del cuerpo histérico. Este descubrimiento se realiza aquí a través de las imágenes fotográficas que han llegado hasta nosotros, las de las publicaciones de la «Iconographie photographique de la Salpêtrière». Pero el análisis de estas imágenes también revela el acto de «escenificación» del que las histéricas fueron objeto por parte de los médicos. Charcot fue un "artista" de este género, pero ¿en qué sentido? Esto es precisamente lo que nos presenta esta obra. Freud fue testigo de todos estos acontecimientos y su testimonio se convirtió en la confrontación de una aproximación totalmente novedosa de la histeria con ese «espectáculo» de la histeria que Charcot ponía en escena. Un testimonio que nos narra los inicios del psicoanálisis bajo la perspectiva del problema de la «imagen».

Fuente: Google Books

Descargar lectura: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1kI1UM9pV5uVQglsPtW2cXQM0dHJeOI_5/view?usp=sharing

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Invention de l'hystérie : Charcot et l'iconographie photographique de la Salpêtrière. Par Georges Didi-Huberman, Ed. Macula, 2011.

Premier livre de Georges Didi-Huberman, publié en 1982, puis réédité chez Macula avec une iconographie enrichie. Le livre raconte la mise en spectacle de l’hystérie et le confinement et la manipulation des femmes enfermées à cette époque à la Salpêtrière, véritable “ville-prison”. Didi-Huberman interroge les conditions de l’expérimentation et de l’enregistrement des “preuves” au moyen de la photographie.

J’ai trouvé le style parfois un peu trop dense, mais le livre est passionnant.

un extrait particulièrement éclairant :

“A la Salpêtrière, cet enfer, les hystériques n’ont pas cessé de faire de l’œil à leurs médecins. Ce fut une espèce de loi du genre, non seulement la loi du fantasme hystérique (désir de captiver), mais encore la loi de toute l’institution asilaire elle-même. Et je dirais que celle-ci avait structure de chantage : en effet, il aura fallu que chaque hystérique fasse montre, et régulièrement, de son orthodoxe “caractère hystérique” (amour des couleurs, “légèreté”, extases érotiques…) pour ne pas être réaffectée au “Quartier”, très dur, des toutes simples et dites incurables “aliénées”.

La séduction était donc comme une tactique obligée, l’Enfer-Salpêtrière distribuant ses pauvres âmes pesées à cercles plus ou moins épouvantables, parmi lesquels le service des Hystériques, avec son côté “expérimental”, fut un peu comme une annexe de Purgatoire.

La situation de chantage était donc à peu près celle-ci : ou bien tu me séduis (te démontrant par là-même hystérique), ou bien je te considère, moi, comme une Incurable, et alors tu seras, à jamais, non plus exhibée, mais cachée, au noir.

Séduire, consista donc, pour les hystériques, à confirmer et rasséréner toujours plus les médecins quand à leur concept de l’Hystérie. Séduire, fut donc aussi, réciproquement, une technologie de maîtrise scientifique, chacun y mit du sien (toute une énergie) pour sa propre dépossession, de parole et de corps. Séduire fut peut-être, pour l’hystérique, mener le Maître par le bout du nez, mais c’était le mener où ?, sinon le mener à être toujours un peu plus le Maître. Séduire, par un étrange renversement, fut donc pour l’hystérique, violence toujours plus cruelle à se faire, quand à sa propre identité, déjà si malheureuse.

Ainsi l’hystérie, à la Salpêtrière, ne devait-elle plus cesser de s’aggraver, toujours plus démonstrative, haute en couleurs, toujours plus soumise à scénarios (et ce, jusqu’à la mort de Charcot, environ)…”

David

Rangement : PHOTO 6 DID

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Photo 1

This photo taken by Paul Regnard was taken for Jean-martin Charcot to be exhibited at his lectures about how hysteria being connected with epilepsy. This photo is in a book called Iconographie photographique de la Salpêtrière This photo was taken in the 1800’s this was a time where women were locked up in mental asylums for illnesses like mental illnesses. This piece of work connects slightly to my work because my work is about mental health and how it can effect people and the man who was photographing this work was looking at women who had mental problems for a man who is working on how their mental problems could be linked to epilepsy so both of our work is looking into how mental illness is effecting people. In this picture particularly is of a women hunched over holding a bag the way she holds the bag is like she is scared and vulnerable and the way she looks at the camera is like she doesn’t know what's going on. On the right side of the picture is a women who is holding out her hand for the women to hold like she is guiding the women to a place she needs to be also in the background looks like she is standing in the middle of the street this could be because she is just leaving home to go to the mental asylum which would explain why she is grasping a bag. The photo is faded showing that it is an old photograph and the way he has photographed her whole body is good showing her positioning of her body helps the viewer see visually how she is feeling. Also the way he photographer uses a shallow depth of field helps show the women better because there is nothing else to take your eyes off the women.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Iconographie photographique de la Salpêtrière

435 notes

·

View notes

Photo

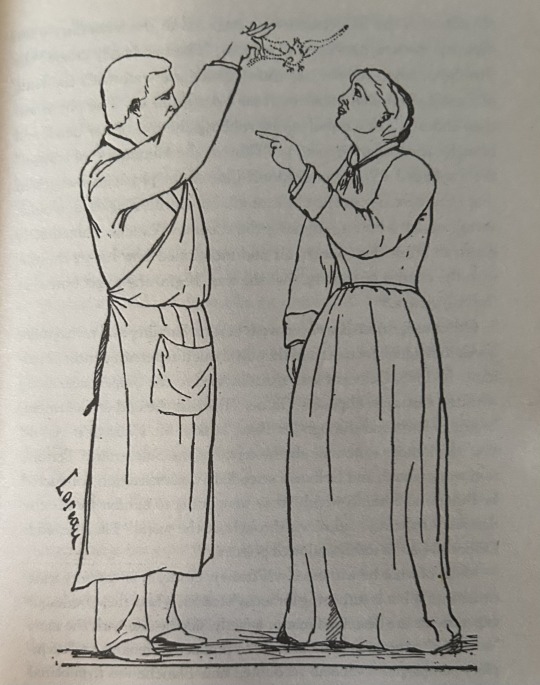

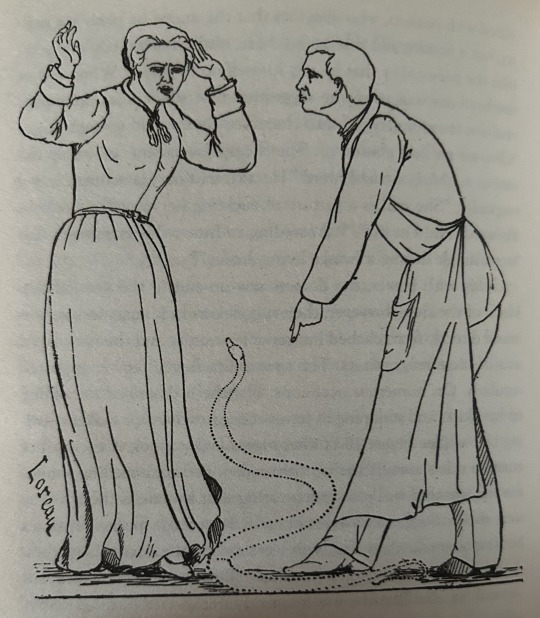

Diagrams of forms of hypnotism, and its effects, ‘Iconographie photographique de la Salpêtrière’ (1876-80) by D.M. Bourneville and P. Regnard.

0 notes

Photo

Albert Londe - A photograph of Marie "Blanche" Wittman in a cataleptic pose taken around - Iconographie photographique de la Salpêtrière : service de M. Charcot (1880)

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Régnard, photograph of Augustine (“Attitudes passionnelles: Ecstasy”), Iconographie, vol. II.

Published in 2003

Invention of Hysteria: Charcot and the Photographic Iconography of the Salpêtrière, Georges Didi-Huberman, Alisa Hartz

In this classic of French cultural studies, Georges Didi-Huberman traces the intimate and reciprocal relationship between the disciplines of psychiatry and photography in the late nineteenth century. Focusing on the immense photographic output of the Salpetriere hospital, the notorious Parisian asylum for insane and incurable women, Didi-Huberman shows the crucial role played by photography in the invention of the category of hysteria. Under the direction of the medical teacher and clinician Jean-Martin Charcot, the inmates of Salpetriere identified as hysterics were methodically photographed, providing skeptical colleagues with visual proof of hysteria's specific form. These images, many of which appear in this book, provided the materials for the multivolume album Iconographie photographique de la Salpetriere. As Didi-Huberman shows, these photographs were far from simply objective documentation. The subjects were required to portray their hysterical "type" -- they performed their own hysteria. Bribed by the special status they enjoyed in the purgatory of experimentation and threatened with transfer back to the inferno of the incurables, the women patiently posed for the photographs and submitted to presentations of hysterical attacks before the crowds that gathered for Charcot's "Tuesday Lectures." Charcot did not stop at voyeuristic observation. Through techniques such as hypnosis, electroshock therapy, and genital manipulation, he instigated the hysterical symptoms in his patients, eventually giving rise to hatred and resistance on their part. Didi-Huberman follows this path from complicity to antipathy in one of Charcot's favorite "cases," that of Augustine, whose image crops up again and again in the Iconographie. Augustine's virtuosic performance of hysteria ultimately became one of self-sacrifice, seen in pictures of ecstasy, crucifixion, and silent cries.

Georges Didi-Huberman, Alisa Hartz

+

#Paul Regnard#Photograph of Augustine#Invention of Hysteria: Charcot and the Photographic Iconography of the Salpêtrière#Psychology#Hysteria#Hôpital de la Salpêtrière Paris

30 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Désiré-Magloire Bourneville and Paul Regnard, from Iconographie photographique de la Salpêtrière (Paris 1875)

The book contains a series of 120 photographs depicting patients (this one diagnosed with hysterical epilepsy) from the neuropsychiatric department of la Pitié-Salpêtrière, one of the largest hospitals in 19th-century Paris. It was one of the first medical studies addressing mental health to use photography rather than drawing/painting for illustrations.

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Charcot uses hypnotism to treat hysteria and other abnormal mental conditions. All materials from "Iconographie photographique de la Salpêtrière" (Jean Martin Charcot, 1878)

0 notes

Photo

Iconographie photographique de la Salpêtrière : service de M. Charcot

0 notes

Photo

Attitudes Passionelles: Extase / photo by the French neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot / from “Iconographie photographique de la Salpêtrière”, 1878.

23 notes

·

View notes