#i would rather every other student in this class cheat and have an 'unfair advantage' over me

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

I'm in an information systems class rn and we're starting out with Excel which I'm already really good at and use in my job daily and tbh it's so frustrating. I'm successfully completing the tasks my assignments want me to do but then I get marked wrong and when I go to check how the system wanted me to do it I'm like "Why would I do it that way?? That's so much less efficient"

#xlookup >>>>> vlookup#why are you teaching people an old function that does the same thing xlookup does but worse and with more confusing arguments 😭#rambling#didnt help that i had to take a quiz for this class today and it took 30 FUCKING MINUTES for the live proctor service to get me set up#only for me to finish it in under 5 minutes once they actually let me in there 😭#i hate this proctor thing so damn much. just let me take my quiz. i dont cheat and idgaf what anyone else does tbh#i would rather every other student in this class cheat and have an 'unfair advantage' over me#than have to deal with this proctor service every time#like what do i care tbh. its not my degree. and its fucking EXCEL like its not even that serious 😭

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

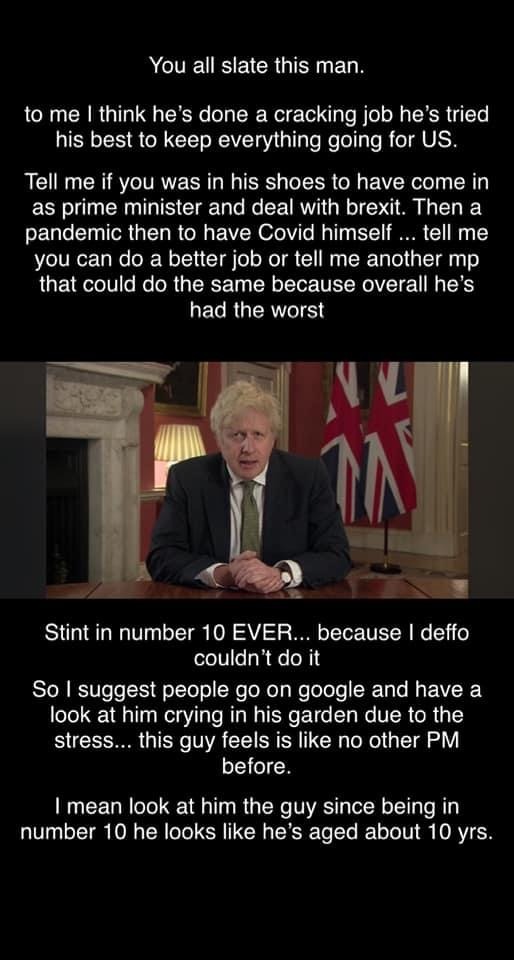

COVID-19, Negligent Manslaughter, and a Timeline of Tory Indifference

“I feel sorry for Boris Johnson. He is doing the best he can in the situation and I don’t think anybody else could have done a better job.”

[exhibit A: a gem somebody that I’m Facebook friends with reposted earlier]

It’s a sentiment that I cannot quite wrap my head around. I sit here hopeless and furious and trying to hold back tears because it’s been almost a year since England first went into lockdown and yet here we are, almost 100,000 dead, in an even worse position than we were before whilst other countries begin to slowly return to normality. It is clear to me who is to blame for this, however there are a large proportion of people who don’t want to “politicise” the actions of the PRIME MINISTER with regards to his approach towards handling a virus sweeping the country he GOVERNS.

Typically, these kind of posts making the rounds on social media will be accompanied by some kind of photo of Boris Johnson looking somber as if to suggest that the way things have played out were beyond his control and that he is some kind of broken man beleaguered by the suffering he has, despite good intentions, inadvertently caused.

This one in particular of Johnson with his head in his hands is a staple. In reality, this is a photo taken back in 2018 whilst he was receiving flack from party members for comparing Theresa May to a suicide bomber (for her handling of Brexit, ironically) as well as from the papers due to his rumoured (now also proven, in a completely non-surprising turn of events, to be true) affair with his former aide, Carrie Symonds.

So let’s shut this narrative-where we should feel for Boris because he’s doing his best, and apparently a better job than anybody else could’ve done in his situation- down right here. In a supposedly developed country with one of the world’s largest economies, if we’re talking by proportion, our COVID-19 death toll is up there with the worst of them. It seems that every other state figurehead (bar a small handful), and I mean almost every single one of them, is doing a better job. People love to throw figures out there about how densely populated we are to combat damning statistics as if we haven’t got just as many factors playing to our advantage, as if it’s unfair to compare our response to Germany’s or Japan’s or Singapore’s (both of which are far more densely populated) or New Zealand’s or Vietnam’s, but we are an ISLAND with world-leading technology and infrastructure and healthcare equipment and professionals and a relatively high standard of living. In what world is almost 70,000 dead in a country with abundant time and means to prepare a response reflective of said country’s leaders doing a good job?

Apparently we’re supposed to believe that Johnson feels some sense of moral responsibility for this astronomical failure. A man who refuses to acknowledge the multiple children he has fathered outside of his marriages and who has had repeatedly engaged in affairs and one-night stands throughout said marriages. A man who continued to cheat whilst his most recent wife was receiving treatment for cervical cancer, for fuck’s sake. Yep, a real stand-up guy.

So where does this idea that Johnson must feel remorseful for this catastrophe come from? We haven’t seen a second of remorse or a hint of accountability for the lives lost from him nor any members of his cabinet. That much is really no surprise; I have this hypothesis, and it’s not a stretch, that these people do not have an ounce of empathy in their bodies. These ridiculously privileged, privately-educated individuals who have had everything handed to them their entire lives simply cannot put themselves in the shoes of the average working person and that is the problem. Unable to recognise that what distinguishes them from most others is little more than the luck of being born into wealth and the abundance of recourses and connections that has entailed throughout their lives, they see us as beneath them-as less intelligent, less driven, and thus less deserving of the status and respect they enjoy. They see us as a bunch of whining, unmotivated idiots who do not recognise the chokehold they have over our media nor the fact that everything they do is a desperate grab to keep money and power within the hands of a select group of people, an exclusive members club from which most of us are barred (just take a simple Google search and watch Jacob Rees-Mogg’s opinion of the Grenfell victims or the buried Johnson speech where he talks about how inequality is essential). They know that we will squabble amongst ourselves about who is to blame rather than wising up to the truth which is that every decision they make is fuelled by cronyism and the inability to make and follow through with difficult choices, the pandemic being no exception. The supposedly self-made elite see the life of the average working class person as having far less value than their own, and their parties actions over the last 10 years have made that very clear.

It was in December 2019 that the first case of COVID-19 was declared to the World Health Organisation and on March the 11th that they announced they considered it as a pandemic. In Wuhan, people were dying of pneumonia in their clusters. And what was Boris Johnson doing in this time? Well for starters, here in the UK we didn’t even have a pandemic committee-Johnson had scrapped it six months before. If years of benefits cuts and defunding of the NHS in favour of funding nuclear weapon programs, keeping British troops on other people’s lands, and tax breaks for the mega corporations that donate to their party didn’t convince you that the Conservatives have little regard for human life, them getting rid of this committee-whilst a pandemic has been declared year after year as the greatest threat to mankind-should have been the first sign of trouble. As if that wasn’t enough, he also skipped five of the COBRA (meetings are made up of a cross-departmental committee put together to respond to national emergencies and PMs routinely attend those pertaining to crises on the scale of COVID-19) meetings addressing the situation. Whilst other countries were closing their borders and stocking up on PPE, Johnson and his ministers were selling PPE abroad and simply telling people to wash their hands to the length of the tune of happy birthday. Their only policy was one of “herd immunity”, which was in fact not a policy but just an abandonment of their party’s public duty disguised as one, intentionally obfuscated with pseudoscientific jargon.

Even thinking the absolute worst of politicians you would hope that when it came to the point where the UK’s non-response to COVID-19 was becoming an international disgrace, Johnson and his ministers would take proper protective measures if only to save face. But when they eventually seemed to do so, it became clear that the priority was not the safety of the ordinary people affected by the virus. Outsourcing their test and traces system to companies such as Serco, Sitel, Deloitte and G4S rather than public health services, Conservative ministers could not resist attempting to line the pockets of their friends and benefactors in the process. According to the Guardian, instead of reaching out to the experts or using publicly funded services to handle COVID containment measures, the Conservative party has awarded a disgusting £1.5 BILLION WORTH of contracts to businesses with explicit connections to its MPs and donors, the majority of which lack any relative experience of the tasks they’ve been trusted to carry out. Unsurprisingly, the National Audit office found that when awarding contracts relating to the production of COVID-19 protection measures and treatment needs, there was a “high-priority lane” for suppliers referred by senior politicians and officials; companies with a political referral were 10 times more likely to end up winning a government contract than those without. On top of this, it is not hard to draw a link between the late initiation of lockdown measures and preemptive openings of pubs and restaurants against scientific advice to the interests of frequent donors such as Wetherspoons owner Tim Martin. Even if one chooses to ignore the blatantly obvious correlation between the owners of the businesses whose profits were prioritised over safety concerns and the number of those owners who donate to the Conservatives, party officials at the very least were reluctant to follow the lead of many other countries in financing furlough schemes themselves and instead avoided this responsibility by using loose lockdown measures to leave it down to the discretion of small business owners, who couldn’t themselves afford to furlough staff, whether or not to stay open.

Time and time again, as the government flounder and fuck about, favouring personal desires to keep their powerful, high-paying jobs and to satisfy the corporate allies who make this possible, blame has been shifted from the public to care homes to NHS workers and back again whilst we, the public, make the biggest sacrifices of all under the illusion that we were being guided out of this pandemic rather than lied to and thrown under the bus. Whilst the elite continue to pick and choose what rules apply to them, it’s students and the elderly and the vulnerable paying the fines and scrabbling to afford basic living costs and hoping that they don’t lose someone dear to them.

Don’t get me wrong, a large proportion of the public have contributed to the spread too with their selfishness and entitlement and the arrogance it takes to develop a sudden refusal to acknowledge basic science from experts who have studied in the field their whole lives so that they can justify their need to go to the pub (speaking of, it’s absolutely HILARIOUS how many “mental health advocates” are suddenly coming out of the woodworks on football avi Twitter after they’ve spent years calling people on mental health Twitter attention seekers). And don't get me wrong, there were inevitably going to be casualties of this pandemic. But it didn't have to spread to this many people, and there didn’t have to be so many deaths due to a lack of preparation, and this wouldn’t have been the case if it weren’t for the inherent apathy of the Conservative party towards the lives of people of lesser status than them, the reluctance to put those lives before party interests. I wish I felt like there was an end in sight, I wish there was some positive takeaway from all of this, but even now, we continue to see corners being cut with the vaccine lauded as our saving grace and anti-maskers gathering outside hospitals to chant about how “oppressive” it is to be urged to wear a bit of cloth over their faces for the short periods of time in which they leave their houses and all I can think of is the selfishness that runs like poison through our country. It makes me sick and leaves me to question desperately where we go from here. I don’t like unanswered questions, I don’t like feeling politically directionless, and I don’t like the growing fear I have about the state of the world which seems to intensify every single day. In the UK at least, it’s starting to feel like nothing will ever change-we’re told we live in a democracy and yet mainstream media is owned by the people whose interest is to keep their Conservative friends in power. The stronghold they have over print media in particular allows them to continually get away with smearing and defaming every person who comes along and seems to want to actually help ordinary people, without being challenged, to the point where the only kind of “opposition” we’re left with promises nothing but a big boss approved tactical reshuffling of the status quo (which they call “electability”); it doesn’t feel like democracy when the majority of the country are being fed misleading information and convinced against voting in their best interests.

This is the result of that. The state we find ourselves in is the inevitable result of being manipulated into helping the elite build their protective wall whilst the rest of us scrabble to get in and step on each others heads along the way, the people inside shouting over that it’s those even more vulnerable than ourselves that are taking our places. Outside the wall, the earth is falling from beneath our feet, and instead of throwing over the ropes to help us out, the people inside are stockpiling them so they can secure their firm place above ground and then later flog the rest. How many more people have to die before we reach some kind of widespread realisation of that? Where do we go from here and what do we do? Well for one, we can stop spreading those god-fucking-awful textposts on Facebook and get our heads out of our arses. Wear our masks over and wear them over our fucking noses. Have some fucking consideration for others. Don’t wait til an issue affects you personally to give a fuck about it. AND START HOLDING THE FUCKING PRIME MINISTER AND HIS MINISTERS AND HIS ENTIRE PARTY AS WELL AS THE OPPOSITION MPS THAT HAVE SAT BY THE SIDELINES AND ALLOWED THIS TO GO ON WITHOUT PROTEST ACCOUNTABLE. That would be a good start.

I’m so tired. Things didn’t need to be this way, and yet because of the selfishness of the few, thousands upon thousands are dead. It’s not about “throwing around blame”, it’s not about “throwing around” anything, it’s about expecting a leader to do his best to protect lives. If that is “throwing blame”, let’s get things clear, I have no issue with hurtling it torpedo style at those who handed out a death sentence to so many in this country rather than do anything that might compromise their own privilege. Honestly, pass me the shovel after and I’ll happily bury the wreckage in the ground. Who wants to join?:-)

#rant#politics#anti capitalism#anticapitalist#covid-19#covid#england#labour#socialism#fuck the tories#fuck the torys#fuck boris#rant post

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Stand and Deliver

I am, practically speaking a math teacher. Technically speaking, I am a mild/moderate special ed teacher, but I teach math, to special ed kids, mostly.

Growing up, one movie I saw over, and over, and over again in school was Stand and Deliver. It was played almost every day we had a sub or the teacher didn’t have a plan, etc, etc etc. Then, my senior year my school theater program (of which I was highly involved) decided to do the play version. I essentially memorized that film. If you don’t know the movie, is carefully based off a true story of the famous math teacher, Jaime Escalante, an immigrant from Bolivia, whose teaches/coaches/mentors a handful of underserved high school students from a gang-ridden Garfield High School in LA into taking and passing the AP Calculus exam. These students success is so impressive, that they naturally are accused of cheating and the students have to retake a harder version of the test to indeed prove they do know math that well.

Anyway, now that I am working math students, I asked myself, should I show the movie to my students? Somehow no one in my school seemed to know about the film. I’m sure things have changed in the 15 years since my own high school experience, and I’m in a different demographic. So I researched the movie carefully and how different educators felt about it.

I ended up reading a lot about Jaime Escalante and the true story the film was based on. It was actually pretty close, a lot closer than your usual Hollywood films, it’s inaccuracies were few and not to dramatic.

I found one fascinating blog post all about why teachers should not show this film to their students. One major point was, while Jaime Escalante was clearly an amazing educator who lead his kids to success, he was very controversial. Not only at Garfield high school as is portrayed in the film for pushing his kids so hard and setting high expectations for him, but also for later in life as he supported “English Only” movement in education. Many had the opinion that such an outlook is oppressive to students learning English as a second language. Most of the blog readers I read who said this, were like me, white, and native English speakers. I found this fascinating. I don’t necessarily agree with the English only movement, I don’t have an opinion and don’t think it’s my place to form one at this time. However, I think it’s possible to separate one person’s endeavor from another and appreciate one without the other. For example, I do in fact like Einstein’s general theory of relativity, however Albert was a huge jerk to his first wife, Meliva (whose name appears on one of the early drafts as its often said she helped with the math involved) and left her penniless with 3 children he refused to support for over a decade. Still Albert Einstein did do an amazing job of figuring out, testing, and working on this theory and that’s still amazing and inspiring. So I don’t think that was a valid reason to not watch it.

Another educator wrote that Stand and Deliver was in the same spirit of “Dangerous Minds” which is definitely a movie about white saviorism. That movie, whose title alone offends me, also based on a true story, is about a white lady who comes to a gang-ridden high school and teaches English to underserved populations and like reduces gang violence or something (it’s been a while). That of course is a theme I need to avoid at all costs, savorism is a horrifying myth I seen projected onto my job, more on that later. For more fun we can watch the SNL skit “Pretty White Lady.”

However, Stand and Deliver is not the same as Dangerous Minds. The teacher is not a white person, but an immigrant himself who is technically classified as Latino. Okay, yes Bolivia is a very different country than say Mexico, or the other countries my students, or his, may come from. And I’m sure they don’t speak the same type of Spanish is Bolivia then say other countries, but still he’s an immigrant literally speaking the same language as his students.

Also, the other factor I had to point out, is the math in Stand and Deliver, is actually very real math. In college I learned an excellent short cut to integration by parts, that my professors learned from the movie. Today things are a lot better, but in that era, the math in movies, was actually quite fake, and bad. The math that is done in SD, is actually quite accurate. It’s real calculus, algebra, and trig. I figured if nothing else I could show it to my kids purely for them to try to recognize the math happening in the movie.

So I played the movie for my students and kept an open mind. I tried not to lecture or get to preachy toward them, I just wanted to be open to how they responded and then figure out if this was an advantageous movie for them to see. I did tell them to be aware of the various math tricks that happened in the movie.

Also it was my first time watching the movie since I learned calculus and was very excited to revisit these scenes and examine the math.

So here is the results:

1. My kids loved the movie. If for nothing else, they liked watching a movie in their math class. They would much rather watch movies then do math. It didn’t matter that the movie was nearly half a century old, still better than doing a worksheet or something.

2. One thing that I noticed is that a number of my kids liked that the movie was about latina/latino students. A number of my students have a lot of pride in their ethnicity. While there are a number of white people in the movie, they show up in minor supporting roles. Much like the reverse of what we see in Hollywood today. The movie really is about Latin Americans and they seemed to appreciate that they were in the foreground. The minute it started, one of my students who had never spoke to me before then, told me about one of his favorite old movies, that was casted completely by latino actors.

Furthermore, while Escalante is central, and he is portrayed as a hero, the real heroes of the movie are actually the high school students. It was very much a movie about kids in high school that delved into their family lives, dating issues, career decisions, conflicts with friends, etc. So it’s also a movie about high school kids.

3. In addition, despite the movie being around 40 years old, there were a couple of cultural elements my students seem to relate to. For example, the way my students greet each other and their particular hand shake (which I can’t do, but am learning, growth mindset) was done in the movie by adults. In the scene when Guadalupe was putting her brothers and sisters to bed, one of my students, who identifies as Mexican, called out, “That’s a Mexican household there. That’s my cousins” My students commented on what food was being cooked in scenes and compared it to their friends and families’ cooking. In the conflict scene where Escalante confronts the college board representatives about the accusations, they were super engaged, predicting, accurately what Escalante would say next and how they would have handled it. They pointed out to me we have the same desks as the students in the movie (facepalm here). They even explained to me, the subtext of the gang violence around Angel in the movie. This is something I didn’t see or understand when I was a kid. Of course this wasn’t the whole movie. A lot of the scenes culturally didn’t make sense to them, they were outdated, not relatable, or relevant.

4. They liked that the movie talked openly about racism. Going back to that scene where Escalante confronts the school board, they were super engaged. They got very excited when Escalante confronts the college board representatives, and the fact that they were sent out because of their distinct ethnic backgrounds. They liked that the racism was being called out rather than everyone turning a blind eye and closed mouth. Most of my students, regardless of ethnicity were engaged in that part.

Some of the kids though just spaced out, or were on their phones. I still have mixed feelings about the film, and would welcome other’s opinions about showing stand and deliver as a math teacher. It could be they were just grateful for a chill day.

For me, I noticed a few things.

1. The math is very accurate, and there are a couple of really cool math tricks happening in it. Namely integration by parts and the trick to multiply by nines using the fingers.

2. I liked that Escalante pointed out the Mayans understood the concept of zero long before europeans did. I personally also like pointing out white people did not invent algebra, middle easterners did. I think the history of math is important, but is often whitewashed to be just about the Greeks and Romans. Often in history, only white history is told and the accomplishments of groups is silenced.

3. The only math flaw I saw in the movie was when Escalante read ln(x-1) as the words L N. Any Calculus teacher worth their weight would of course read it as “The Natural Log of x minus 1.

4. There are all sorts of subtext I understand now as an adult, that I didn’t as a kid. The fact the Ana leaves the test early so others won’t be accused of cheating off of her, or that Guadalupe doesn’t have a place or time to study when she’s at home.

5. There is a honestly, the kids are clearly treated unfair by society and the movie points out this truth. The kids rise above by having to work extra hard to retake the test. I don’t know about the message of having the kids to work extra hard, I don’t want to get to preachy in my profession. But at least it acknowledges the unfair, racist elements the kids deal with, rather than be in denial or victim blaming I often see. It does have the message that the the kids are up to the challenge. They may have to work harder, but they are certainly underestimate by those in power over them. That makes an interesting point, but I’m not sure what it is yet.

Anyway, I showed the movie this year, and I would love other’s thoughts about it.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Fantastic article. A must-Read for all parents and/or teachers.

“1. To be a parent is to be compromised. You pledge allegiance to justice for all, you swear that private attachments can rhyme with the public good, but when the choice comes down to your child or an abstraction—even the well-being of children you don’t know—you’ll betray your principles to the fierce unfairness of love. Then life takes revenge on the conceit that your child’s fate lies in your hands at all. The organized pathologies of adults, including yours—sometimes known as politics—find a way to infect the world of children. Only they can save themselves.

Our son underwent his first school interview soon after turning 2. He’d been using words for about a year. An admissions officer at a private school with brand-new, beautifully and sustainably constructed art and dance studios gave him a piece of paper and crayons. While she questioned my wife and me about our work, our son drew a yellow circle over a green squiggle.

Rather coolly, the admissions officer asked him what it was. “The moon,” he said. He had picked this moment to render his very first representational drawing, and our hopes rose. But her jaw was locked in an icy and inscrutable smile.

Later, at a crowded open house for prospective families, a hedge-fund manager from a former Soviet republic told me about a good public school in the area that accepted a high percentage of children with disabilities. As insurance against private school, he was planning to grab a spot at this public school by gaming the special-needs system—which, he added, wasn’t hard to do.

Wanting to distance myself from this scheme, I waved my hand at the roomful of parents desperate to cough up $30,000 for preschool and said, “It’s all a scam.” I meant the whole business of basing admissions on interviews with 2-year-olds. The hedge-fund manager pointed out that if he reported my words to the admissions officer, he’d have one less competitor to worry about.

When the rejection letter arrived, I took it hard as a comment on our son, until my wife informed me that the woman with the frozen smile had actually been interviewing us. We were the ones who’d been rejected. We consoled ourselves that the school wasn’t right for our family, or we for it. It was a school for amoral finance people.

At a second private school, my wife watched intently with other parents behind a one-way mirror as our son engaged in group play with other toddlers, their lives secured or ruined by every share or shove. He was put on the wait list.

Places at the preschool were awarded on a first-come, first-served basis. At the front of the line, parents were lying in sleeping bags. They had spent the night outside.

The system that dominates our waking hours, commands our unthinking devotion, and drives us, like orthodox followers of an exacting faith, to extraordinary, even absurd feats of exertion is not democracy, which often seems remote and fragile. It’s meritocracy—the system that claims to reward talent and effort with a top-notch education and a well-paid profession, its code of rigorous practice and generous blessings passed down from generation to generation. The pressure of meritocracy made us apply to private schools when our son was 2—not because we wanted him to attend private preschool, but because, in New York City, where we live, getting him into a good public kindergarten later on would be even harder, and if we failed, by that point most of the private-school slots would be filled. As friends who’d started months earlier warned us, we were already behind the curve by the time he drew his picture of the moon. We were maximizing options—hedging, like the finance guy, like many families we knew—already tracing the long line that would lead to the horizon of our son’s future.

I stood waiting in the cold with a strange mix of feelings. I hated the hypercompetitive parents who made everyone’s life more tense. I feared that I’d cheated our son of a slot by not rising until the selfish hour of 5:30. And I worried that we were all bound together in a mad, heroic project that we could neither escape nor understand, driven by supreme devotion to our own child’s future. All for a nursery school called Huggs.

New York’s distortions let you see the workings of meritocracy in vivid extremes. But the system itself—structured on the belief that, unlike in a collectivized society, individual achievement should be the basis for rewards, and that, unlike in an inherited aristocracy, those rewards must be earned again by each new generation—is all-American. True meritocracy came closest to realization with the rise of standardized tests in the 1950s, the civil-rights movement, and the opening of Ivy League universities to the best and brightest, including women and minorities. A great broadening of opportunity followed. But in recent decades, the system has hardened into a new class structure in which professionals pass on their money, connections, ambitions, and work ethic to their children, while less educated families fall further behind, with little chance of seeing their children move up.

In his new book, The Meritocracy Trap, the Yale Law professor Daniel Markovits argues that this system turns elite families into business enterprises, and children into overworked, inauthentic success machines, while producing an economy that favors the super-educated and blights the prospects of the middle class, which sinks toward the languishing poor. Markovits describes the immense investments in money and time that well-off couples make in their children. By kindergarten, the children of elite professionals are already a full two years ahead of middle-class children, and the achievement gap is almost unbridgeable.

On that freezing sidewalk, I felt a shudder of revulsion at the perversions of meritocracy. And yet there I was, cursing myself for being 30th in line.

2.

not long after he drew the picture of the moon, our son was interviewed at another private school, one of the most highly coveted in New York. It was the end of 2009, early in President Barack Obama’s first term, and the teachers were wearing brightly colored hope pendants that they had crafted with their preschoolers. I suppressed disapproval of the partisan display (what if the face hanging from the teachers’ necks were Sarah Palin’s?) and reassured myself that the school had artistic and progressive values. It recruited the children of writers and other “creatives.” And our son’s monitored group play was successful. He was accepted.

The school had delicious attributes. Two teachers in each class of 15 children; parents who were concert pianists or playwrights, not just investment bankers; the prospect later on of classes in Latin, poetry writing, puppetry, math theory, taught by passionate scholars. Once in, unless a kid seriously messed up, he faced little chance of ever having to leave, until, 15 years on, the school matched its graduates with top universities where it had close relations with admissions offices. Students wouldn’t have to endure the repeated trauma of applying to middle and high schools that New York forces on public-school children. Our son had a place near the very front of the line, shielded from the meritocracy at its most ruthless. There was only one competition, and he had already prevailed, in monitored group play.

Two years later we transferred him to a public kindergarten.

My wife and I are products of public schools. Whatever torments they inflicted on our younger selves, we believed in them.

We had just had our second child, a girl. The private school was about to start raising its fee steeply every year into the indefinite future. As tuition passed $50,000, the creatives would dwindle and give way to the financials. I calculated that the precollege educations of our two children would cost more than $1.5 million after taxes. This was the practical reason to leave.

But there was something else—another claim on us. The current phrase for it is social justice. I’d rather use the word democracy, because it conveys the idea of equality and the need for a common life among citizens. No institution has more power to form human beings according to this idea than the public school. That was the original purpose of the “common schools” established by Horace Mann in the mid-19th century: to instill in children the knowledge and morality necessary for the success of republican government, while “embracing children of all religious, social, and ethnic backgrounds.”

The claim of democracy doesn’t negate meritocracy, but they’re in tension. One values equality and openness, the other achievement and security. Neither can answer every need. To lose sight of either makes life poorer. The essential task is to bring meritocracy and democracy into a relation where they can coexist and even flourish.

My wife and I are products of public schools. Whatever torments they inflicted on our younger selves, we believed in them. We wanted our kids to learn in classrooms that resembled the city where we lived. We didn’t want them to grow up entirely inside our bubble—mostly white, highly and expensively educated—where 4-year-olds who hear 21,000 words a day acquire the unearned confidence of insular advantage and feel, even unconsciously, that they’re better than other people’s kids.

Public schools are a public good. Our city’s are among the most racially and economically segregated in America. The gaps in proficiency that separate white and Asian from black and Latino students in math and English are immense and growing. Some advocates argue that creating more integrated schools would reduce those gaps. Whether or not the data conclusively prove it, to be half-conscious in America is to know that schools of concentrated poverty are likely to doom the children who attend them. This knowledge is what made our decision both political and fraught.

From October 2017: Americans have given up on public schools. That’s a mistake.

Our “zoned” elementary school, two blocks from our house, was forever improving on a terrible reputation, but not fast enough. Friends had pulled their kids out after second or third grade, so when we took the tour we insisted, against the wishes of the school guide, on going upstairs from the kindergarten classrooms and seeing the upper grades, too. Students were wandering around the rooms without focus, the air was heavy with listlessness, there seemed to be little learning going on. Each year the school was becoming a few percentage points less poor and less black as the neighborhood gentrified, but most of the white kids were attending a “gifted and talented” school within the school, where more was expected and more was given. The school was integrating and segregating at the same time.

One day I was at a local playground with our son when I fell into conversation with an elderly black woman who had lived in the neighborhood a long time and understood all about our school dilemma, which was becoming the only subject that interested me. She scoffed at our “zoned” school—it had been badly run for so long that it would need years to become passable. I mentioned a second school, half a dozen blocks away, that was probably available if we applied. Her expression turned to alarm. “Don’t send him there,” she said. “That’s a failure school. That school will always be a failure school.” It was as if an eternal curse had been laid on it, beyond anyone’s agency or remedy. The school was mostly poor and black. We assumed it would fail our children, because we knew it was failing other children.

That year, when my son turned 5, attending daytime tours and evening open houses became a second job. We applied to eight or nine public schools. We applied to far-flung schools that we’d heard took a few kids from out of district, only to find that there was a baby boom on and the seats had already been claimed by zoned families. At one new school that had a promising reputation, the orientation talk was clotted with education jargon and the toilets in the boys’ bathroom with shit, but we would have taken a slot if one had been offered.

Among the schools where we went begging was one a couple of miles from our house that admitted children from several districts. This school was economically and racially mixed by design, with demographics that came close to matching the city’s population: 38 percent white, 29 percent black, 24 percent Latino, 7 percent Asian. That fact alone made the school a rarity in New York. Two-thirds of the students performed at or above grade level on standardized tests, which made the school one of the higher-achieving in the city (though we later learned that there were large gaps, as much as 50 percent, between the results for the wealthier, white students and the poorer, Latino and black students). And the school appeared to be a happy place. Its pedagogical model was progressive—“child centered”—based on learning through experience. Classes seemed loose, but real work was going on. Hallways were covered with well-written compositions. Part of the playground was devoted to a vegetable garden. This combination of diversity, achievement, and well-being was nearly unheard-of in New York public schools. This school squared the hardest circle. It was a liberal white family’s dream. The admission rate was less than 10 percent. We got wait-listed.

The summer before our son was to enter kindergarten, an administrator to whom I’d written a letter making the case that our family and the school were a perfect match called with the news that our son had gotten in off the wait list. She gave me five minutes to come up with an answer. I didn’t need four and a half of them.

I can see now that a strain of selfishness and vanity in me contaminated the decision. I lived in a cosseted New York of successful professionals. I had no authentic connection—not at work, in friendships, among neighbors—to the shared world of the city’s very different groups that our son was about to enter. I was ready to offer him as an emissary to that world, a token of my public-spiritedness. The same narcissistic pride that a parent takes in a child’s excellent report card, I now felt about sending him in a yellow school bus to an institution whose name began with P.S.

A few parents at the private school reacted as if we’d given away a winning lottery ticket, or even harmed our son—such was the brittle nature of meritocracy. And to be honest, in the coming years, when we heard that sixth graders at the private school were writing papers on The Odyssey, or when we watched our son and his friends sweat through competitive public-middle-school admissions, we wondered whether we’d committed an unforgivable sin and went back over all our reasons for changing schools until we felt better.

Before long our son took to saying, “I’m a public-school person.” When I asked him once what that meant, he said, “It means I’m not snooty.” He never looked back.

Illustration of a hand holding a pencil

Paul Spella

3.

the public school was housed in the lower floors of an old brick building, five stories high and a block long, next to an expressway. A middle and high school occupied the upper floors. The building had the usual grim features of any public institution in New York—steel mesh over the lower windows, a police officer at the check-in desk, scuffed yellow walls, fluorescent lights with toxic PCBs, caged stairwells, ancient boilers and no air conditioners—as if to dampen the expectations of anyone who turned to government for a basic service. The bamboo flooring and state-of-the-art science labs of private schools pandered to the desire for a special refuge from the city. Our son’s new school felt utterly porous to it.

I had barely encountered an American public school since leaving high school. That was in the late 1970s, in the Bay Area, the same year that the tax revolt began its long evisceration of California’s stellar education system. Back then, nothing was asked of parents except that they pay their taxes and send their children to school, and everyone I knew went to the local public schools. Now the local public schools—at least the one our son was about to attend—couldn’t function without parents. Donations at our school paid the salaries of the science teacher, the Spanish teacher, the substitute teachers. They even paid for furniture. Because many of the families were poor, our PTA had a hard time meeting its annual fundraising goal of $100,000, and some years the principal had to send out a message warning parents that science or art was about to be cut. Not many blocks away, elementary schools zoned for wealthy neighborhoods routinely raised $1 million—these schools were called “private publics.” Schools in poorer neighborhoods struggled to bring in $30,000. This enormous gap was just one way inequality pursued us into the public-school system.

We threw ourselves into the adventure of the new school. We sent in class snacks when it was our week, I chaperoned a field trip to study pigeons in a local park, and my wife cooked chili for an autumn fundraiser. The school’s sense of mission extended to a much larger community, and so there was an appeal for money when a fire drove a family from a different school out of its house, and a food drive after Hurricane Sandy ravaged the New York area, and a shoe drive for Syrian refugees in Jordan. We were ready to do just about anything to get involved. When my wife came in one day to help out in class, she was enlisted as a recess monitor and asked to change the underwear of a boy she didn’t know from another class who’d soiled himself. (Volunteerism had a limit, and that was it.)

The private school we’d left behind had let parents know they weren’t needed, except as thrilled audiences at performances. But our son’s kindergarten teacher—an eccentric man near retirement age, whose uniform was dreadlocks (he was white), a leather apron, shorts, and sandals with socks—sent out frequent and frankly needy SOS emails. When his class of 28 students was studying the New York shoreline, he enlisted me to help build a replica of an antique cargo ship like the one docked off Lower Manhattan—could I pick up a sheet of plywood, four by eight by 5/8 of an inch, cut in half, along with four appropriate hinges and two dozen plumbing pieces, if they weren’t too expensive? He would reimburse me.

That first winter, the city’s school-bus drivers called a strike that lasted many weeks. I took turns with a few other parents ferrying a group of kids to and from school. Everyone who needed a ride would gather at the bus stop at 7:30 each morning and we’d figure out which parent could drive that day. Navigating the strike required a flexible schedule and a car, and it put immense pressure on families. A girl in our son’s class who lived in a housing project a mile from the school suddenly stopped attending. Administrators seemed to devote as much effort to rallying families behind the bus drivers’ union as to making sure every child could get to school. That was an early sign of what would come later, of all that would eventually alienate me, and I might have been troubled by it if I hadn’t been so taken with my new role as a public-school father teaming up with other parents to get us through a crisis.

4.

parents have one layer of skin too few. They’ve lost an epidermis that could soften bruises and dull panic. In a divided city, in a stratified society, that missing skin—the intensity of every little worry and breakthrough—is the shortest and maybe the only way to intimacy between people who would otherwise never cross paths. Children become a great leveler. Parents have in common the one subject that never ceases to absorb them.

In kindergarten our son became friends with a boy in class I’ll call Marcus. He had mirthful eyes, a faint smile, and an air of imperturbable calm—he was at ease with everyone, never visibly agitated or angry. His parents were working-class immigrants from the Caribbean. His father drove a sanitation truck, and his mother was a nanny whose boss had been the one to suggest entering Marcus in the school’s lottery—parents with connections and resources knew about the school, while those without rarely did. Marcus’s mother was a quietly demanding advocate for her son, and Marcus was exactly the kind of kid for whom a good elementary school could mean the chance of a lifetime. His family and ours were separated by race, class, and the dozen city blocks that spell the difference between a neighborhood with tree-lined streets, regular garbage collection, and upscale cupcake shops, and a neighborhood with aboveground power lines and occasional shootings. If not for the school, we would never have known Marcus’s family.

The boys’ friendship would endure throughout elementary school and beyond. Once, when they were still in kindergarten, my wife was walking with them in a neighborhood of townhouses near the school, and Marcus suddenly exclaimed, “Can you imagine having a backyard?” We had a backyard. Our son kept quiet, whether out of embarrassment or an early intuition that human connections require certain omissions. Marcus’s father would drop him off at our house on weekends—often with the gift of a bottle of excellent rum from his home island—or I would pick Marcus up at their apartment building and drive the boys to a batting cage or the Bronx Zoo. They almost always played at our house, seldom at Marcus’s, which was much smaller. This arrangement was established from the start without ever being discussed. If someone had mentioned it, we would have had to confront the glaring inequality in the boys’ lives. I felt that the friendship flourished in a kind of benign avoidance of this crucial fact.

At school our son fell in with a group of boys who had no interest in joining the lunchtime soccer games. Their freewheeling playground scrums often led to good-natured insults, wrestling matches, outraged feelings, an occasional punch, then reconciliation, until the next day. And they were the image of diversity. Over the years, in addition to our son and Marcus, there was another black boy, another white boy, a Latino boy, a mixed-race boy, a boy whose Latino mother was a teacher’s aide at the school, and an African boy with white lesbian parents. A teacher at the private school had once called our son “anti-authoritarian,” and it was true: He pursued friends who were mildly rebellious, irritants to the teachers and lunch monitors they didn’t like, and he avoided kids who always had their hand up and displayed obvious signs of parental ambition. The anxious meritocrat in me hadn’t completely faded away, and I once tried to get our son to befriend a 9-year-old who was reading Animal Farm, but he brushed me off. He would do this his own way.

The school’s pedagogy emphasized learning through doing. Reading instruction didn’t start until the end of first grade; in math, kids were taught various strategies for multiplication and division, but the times tables were their parents’ problem. Instead of worksheets and tests, there were field trips to the shoreline and the Noguchi sculpture museum. “Project-based learning” had our son working for weeks on a clay model of a Chinese nobleman’s tomb tower during a unit on ancient China.

Even as we continued to volunteer, my wife and I never stopped wondering if we had cheated our son of a better education. We got antsy with the endless craft projects, the utter indifference to spelling. But our son learned well only when a subject interested him. “I want to learn facts, not skills,” he told his first-grade teacher. The school’s approach—the year-long second-grade unit on the geology and bridges of New York—caught his imagination, while the mix of races and classes gave him something even more precious: an unselfconscious belief that no one was better than anyone else, that he was everyone’s equal and everyone was his. In this way the school succeeded in its highest purpose.

And then things began to change.

5.

around 2014, a new mood germinated in America—at first in a few places, among limited numbers of people, but growing with amazing rapidity and force, as new things tend to do today. It rose up toward the end of the Obama years, in part out of disillusionment with the early promise of his presidency—out of expectations raised and frustrated, especially among people under 30, which is how most revolutionary surges begin. This new mood was progressive but not hopeful. A few short years after the teachers at the private preschool had crafted Obama pendants with their 4-year-olds, hope was gone.

At the heart of the new progressivism was indignation, sometimes rage, about ongoing injustice against groups of Americans who had always been relegated to the outskirts of power and dignity. An incident—a police shooting of an unarmed black man; news reports of predatory sexual behavior by a Hollywood mogul; a pro quarterback who took to kneeling during the national anthem—would light a fire that would spread overnight and keep on burning because it was fed by anger at injustices deeper and older than the inflaming incident. Over time the new mood took on the substance and hard edges of a radically egalitarian ideology.

At points where the ideology touched policy, it demanded, and in some cases achieved, important reforms: body cameras on cops, reduced prison sentences for nonviolent offenders, changes in the workplace. But its biggest influence came in realms more inchoate than policy: the private spaces where we think and imagine and talk and write, and the public spaces where institutions shape the contours of our culture and guard its perimeter.

Who was driving the new progressivism? Young people, influencers on social media, leaders of cultural organizations, artists, journalists, educators, and, more and more, elected Democrats. You could almost believe they spoke for a majority—but you would be wrong. An extensive survey of American political opinion published last year by a nonprofit called More in Common found that a large majority of every group, including black Americans, thought “political correctness” was a problem. The only exception was a group identified as “progressive activists”—just 8 percent of the population, and likely to be white, well educated, and wealthy. Other polls found that white progressives were readier to embrace diversity and immigration, and to blame racism for the problems of minority groups, than black Americans were. The new progressivism was a limited, mainly elite phenomenon.

Politics becomes most real not in the media but in your nervous system, where everything matters more and it’s harder to repress your true feelings because of guilt or social pressure. It was as a father, at our son’s school, that I first understood the meaning of the new progressivism, and what I disliked about it.

Every spring, starting in third grade, public-school students in New York State take two standardized tests geared to the national Common Core curriculum—one in math, one in English. In the winter of 2015–16, our son’s third-grade year, we began to receive a barrage of emails and flyers from the school about the upcoming tests. They all carried the message that the tests were not mandatory. “Inform Yourself!” an email urged us. “Whether or not your child will take the tests is YOUR decision.”

During the George W. Bush and Obama presidencies, statewide tests were used to improve low-performing schools by measuring students’ abilities, with rewards (“race to the top”) and penalties (“accountability”) doled out accordingly. These standardized tests could determine the fate of teachers and schools. Some schools began devoting months of class time to preparing students for the tests.

The excesses of “high-stakes testing” inevitably produced a backlash. In 2013, four families at our school, with the support of the administration, kept their kids from taking the tests. These parents had decided that the tests were so stressful for students and teachers alike, consumed so much of the school year with mindless preparation, and were so irrelevant to the purpose of education that they were actually harmful. But even after the city eased the consequences of the tests, the opt-out movement grew astronomically. In the spring of 2014, 250 children were kept from taking the tests.

The critique widened, too: Educators argued that the tests were structurally biased, even racist, because nonwhite students had the lowest scores. “I believe in assessment—I took tests my whole life and I’ve used assessments as an educator,” one black parent at our school, who graduated from a prestigious New York public high school, told me. “But now I see it all differently. Standardized tests are the gatekeepers to keep people out, and I know exactly who’s at the bottom. It is torturous for black, Latino, and low-income children, because they will never catch up, due to institutionalized racism.”

Our school became the citywide leader of the new movement; the principal was interviewed by the New York media. Opting out became a form of civil disobedience against a prime tool of meritocracy. It started as a spontaneous, grassroots protest against a wrongheaded state of affairs. Then, with breathtaking speed, it transcended the realm of politics and became a form of moral absolutism, with little tolerance for dissent.

We took the school at face value when it said that this decision was ours to make. My wife attended a meeting for parents, billed as an “education session.” But when she asked a question that showed we hadn’t made up our minds about the tests, another parent quickly tried to set her straight. The question was out of place—no one should want her child to take the tests. The purpose of the meeting wasn’t to provide neutral information. Opting out required an action—parents had to sign and return a letter—and the administration needed to educate new parents about the party line using other parents who had already accepted it, because school employees were forbidden to propagandize.

We weren’t sure what to do. Instead of giving grades, teachers at our school wrote long, detailed, often deeply knowledgeable reports on each student. But we wanted to know how well our son was learning against an external standard. If he took the tests, he would miss a couple of days of class, but he would also learn to perform a basic task that would be part of his education for years to come.

One day I asked another parent whether her son would take the tests. She hushed me—it wasn’t something to discuss at school.

Something else about the opt-out movement troubled me. Its advocates claimed that the tests penalized poor and minority kids. I began to think that the real penalty might come from not taking them. Opting out had become so pervasive at our school that the Department of Education no longer had enough data to publish the kind of information that prospective applicants had once used to assess the school. In the category of “Student Achievement” the department now gave our school “No Rating.” No outsider could judge how well the school was educating children, including poor, black, and Latino children. The school’s approach left gaps in areas like the times tables, long division, grammar, and spelling. Families with means filled these gaps, as did some families whose means were limited—Marcus’s parents enrolled him in after-school math tutoring. But when a girl at our bus stop fell behind because she didn’t attend school for weeks after the death of her grandmother, who had been the heart of the family, there was no objective measure to act as a flashing red light. In the name of equality, disadvantaged kids were likelier to falter and disappear behind a mist of togetherness and self-deception. Banishing tests seemed like a way to let everyone off the hook. This was the price of dismissing meritocracy.

I took a sounding of parents at our bus stop. Only a few were open to the tests, and they didn’t say this loudly. One parent was trying to find a way to have her daughter take the tests off school grounds. Everyone sensed that failing to opt out would be unpopular with the principal, the staff, and the parent leaders—the school’s power structure.

A careful silence fell over the whole subject. One day, while volunteering in our son’s classroom, I asked another parent whether her son would take the tests. She flashed a nervous smile and hushed me—it wasn’t something to discuss at school. One teacher disapproved of testing so intensely that, when my wife and I asked what our son would miss during test days, she answered indignantly, “Curriculum!” Students whose parents declined to opt out would get no preparation at all. It struck me that this would punish kids whom the movement was supposed to protect.

If orthodoxy reduced dissenters to whispering—if the entire weight of public opinion at the school was against the tests—then, I thought, our son should take them.

The week of the tests, one of the administrators approached me in the school hallway. “Have you decided?” I told her that our son would take the tests.

She was the person to whom I’d once written a letter about the ideal match between our values and the school’s, the letter that may have helped get our son off the wait list. Back then I hadn’t heard of the opt-out movement—it didn’t exist. Less than four years later, it was the only truth. I wondered if she felt that I’d betrayed her.

Later that afternoon we spent an hour on the phone. She described all the harm that could come to our son if he took the tests—the immense stress, the potential for demoralization. I replied with our reason for going ahead—we wanted him to learn this necessary skill. The conversation didn’t feel completely honest on either side: She also wanted to confirm the school’s position in the vanguard of the opt-out movement by reaching 100 percent compliance, and I wanted to refuse to go along. The tests had become secondary. This was a political argument.

Our son was among the 15 or so students who took the tests. A 95 percent opt-out rate was a resounding success. It rivaled election results in Turkmenistan. As for our son, he finished the tests feeling neither triumphant nor defeated. The issue that had roiled the grown-ups in his life seemed to have had no effect on him at all. He returned to class and continued working on his report about the mountain gorillas of Central Africa.

Illustration of the American flag with gold stars scattered on top

Paul Spella

6.

the battleground of the new progressivism is identity. That’s the historical source of exclusion and injustice that demands redress. In the past five years, identity has set off a burst of exploration and recrimination and creation in every domain, from television to cooking. “Identity is the topic at the absolute center of our conversations about music,” The New York Times Magazine declared in 2017, in the introduction to a special issue consisting of 25 essays on popular songs. “For better or worse, it’s all identity now.”

The school’s progressive pedagogy had fostered a wonderfully intimate sense of each child as a complex individual. But progressive politics meant thinking in groups. When our son was in third or fourth grade, students began to form groups that met to discuss issues based on identity—race, sexuality, disability. I understood the solidarity that could come from these meetings, but I also worried that they might entrench differences that the school, by its very nature, did so much to reduce. Other, less diverse schools in New York, including elite private ones, had taken to dividing their students by race into consciousness-raising “affinity groups.” I knew several mixed-race families that transferred their kids out of one such school because they were put off by the relentless focus on race. Our son and his friends, whose classroom study included slavery and civil rights, hardly ever discussed the subject of race with one another. The school already lived what it taught.

The bathroom crisis hit our school the same year our son took the standardized tests. A girl in second grade had switched to using male pronouns, adopted the initial Q as a first name, and begun dressing in boys’ clothes. Q also used the boys’ bathroom, which led to problems with other boys. Q’s mother spoke to the principal, who, with her staff, looked for an answer. They could have met the very real needs of students like Q by creating a single-stall bathroom—the one in the second-floor clinic would have served the purpose. Instead, the school decided to get rid of boys’ and girls’ bathrooms altogether. If, as the city’s Department of Education now instructed, schools had to allow students to use the bathroom of their self-identified gender, then getting rid of the labels would clear away all the confusion around the bathroom question. A practical problem was solved in conformity with a new idea about identity.

Within two years, almost every bathroom in the school, from kindergarten through fifth grade, had become gender-neutral. Where signs had once said boys and girls, they now said students. Kids would be conditioned to the new norm at such a young age that they would become the first cohort in history for whom gender had nothing to do with whether they sat or stood to pee. All that biology entailed—curiosity, fear, shame, aggression, pubescence, the thing between the legs—was erased or wished away.

The school didn’t inform parents of this sudden end to an age-old custom, as if there were nothing to discuss. Parents only heard about it when children started arriving home desperate to get to the bathroom after holding it in all day. Girls told their parents mortifying stories of having a boy kick open their stall door. Boys described being afraid to use the urinals. Our son reported that his classmates, without any collective decision, had simply gone back to the old system, regardless of the new signage: Boys were using the former boys’ rooms, girls the former girls’ rooms. This return to the familiar was what politicians call a “commonsense solution.” It was also kind of heartbreaking. As children, they didn’t think to challenge the new adult rules, the new adult ideas of justice. Instead, they found a way around this difficulty that the grown-ups had introduced into their lives. It was a quiet plea to be left alone.

When parents found out about the elimination of boys’ and girls’ bathrooms, they showed up en masse at a PTA meeting. The parents in one camp declared that the school had betrayed their trust, and a woman threatened to pull her daughter out of the school. The parents in the other camp argued that gender labels—and not just on the bathroom doors—led to bullying and that the real problem was the patriarchy. One called for the elimination of urinals. It was a minor drama of a major cultural upheaval. The principal, who seemed to care more about the testing opt-out movement than the bathroom issue, explained her financial constraints and urged the formation of a parent-teacher committee to resolve the matter. After six months of stalemate, the Department of Education intervened: One bathroom would be gender-neutral.

in politics, identity is an appeal to authority—the moral authority of the oppressed: I am what I am, which explains my view and makes it the truth. The politics of identity starts out with the universal principles of equality, dignity, and freedom, but in practice it becomes an end in itself—often a dead end, a trap from which there’s no easy escape and maybe no desire for escape. Instead of equality, it sets up a new hierarchy that inverts the old, discredited one—a new moral caste system that ranks people by the oppression of their group identity. It makes race, which is a dubious and sinister social construct, an essence that defines individuals regardless of agency or circumstance—as when Representative Ayanna Pressley said, “We don’t need any more brown faces that don’t want to be a brown voice; we don’t need black faces that don’t want to be a black voice.”

At times the new progressivism, for all its up-to-the-minuteness, carries a whiff of the 17th century, with heresy hunts and denunciations of sin and displays of self-mortification. The atmosphere of mental constriction in progressive milieus, the self-censorship and fear of public shaming, the intolerance of dissent—these are qualities of an illiberal politics.

I asked myself if I was moving to the wrong side of a great moral cause because its tone was too loud, because it shook loose what I didn’t want to give up. It took me a long time to see that the new progressivism didn’t just carry my own politics further than I liked. It was actually hostile to principles without which I don’t believe democracy can survive. Liberals are always slow to realize that there can be friendly, idealistic people who have little use for liberal values.

7.

in 2016 two obsessions claimed our family—Hamilton and the presidential campaign. We listened and sang along to the Hamilton soundtrack every time we got in the car, until the kids had memorized most of its brilliant, crowded, irresistible libretto. Our son mastered Lafayette’s highest-velocity rap, and in our living room he and his sister acted out the climactic duel between Hamilton and Burr. The musical didn’t just teach them this latest version of the revolution and the early republic. It filled their world with the imagined past, and while the music was playing, history became more real than the present. Our daughter, who was about to start kindergarten at our son’s school, wholly identified with the character of Hamilton—she fought his battles, made his arguments, and denounced his enemies. Every time he died she wept.

Read: How Lin-Manuel Miranda’s ‘Hamilton’ shapes history

Hamilton and the campaign had a curious relation in our lives. The first acted as a disinfectant to the second, cleansing its most noxious effects, belying its most ominous portents. Donald Trump could sneer at Mexicans and rail against Muslims and kick dirt on everything decent and good, but the American promise still breathed whenever the Puerto Rican Hamilton and the black Jefferson got into a rap battle over the national bank. When our daughter saw pictures of the actual Founding Fathers, she was shocked and a little disappointed that they were white. The only president our kids had known was black. Their experience gave them no context for Trump’s vicious brand of identity politics, which was inflaming the other kinds. We wanted them to believe that America was better than Trump, and Hamilton kept that belief in the air despite the accumulating gravity of facts. Our son, who started fourth grade that fall, had dark premonitions about the election, but when the Access Hollywood video surfaced in October, he sang Jefferson’s gloating line about Hamilton’s sex scandal: “Never gonna be president now!”

The morning after the election, the kids cried. They cried for people close to us, Muslims and immigrants who might be in danger, and perhaps they also cried for the lost illusion that their parents could make things right. Our son lay on the couch and sobbed inconsolably until we made him go to the bus stop.

The next time we were in the car, we automatically put on Hamilton. When “Dear Theodosia” came on, and Burr and Hamilton sang to their newborn children, “If we lay a strong enough foundation, we’ll pass it on to you, we’ll give the world to you, and you’ll blow us all away,” it was too much for me and my wife. We could no longer feel the romance of the young republic. It was a long time before we listened to Hamilton again.

A few weeks after the election, our daughter asked if Trump could break our family apart. She must have gotten the idea from overhearing a conversation about threats to undocumented immigrants. We told her that we were lucky—we had rights as citizens that he couldn’t take away. I decided to sit down with the kids and read the Bill of Rights together. Not all of it made sense, but they got the basic idea—the president wasn’t King George III, the Constitution was stronger than Trump, certain principles had not been abolished—and they seemed reassured.

Since then it has become harder to retain faith in these truths.

Our daughter said that she hated being a child, because she felt helpless to do anything. The day after the inauguration, my wife took her to the Women’s March in Midtown Manhattan. She made a sign that said we have power too, and at the march she sang the one protest song she knew, “We Shall Overcome.” For days afterward she marched around the house shouting, “Show me what democracy looks like!”

Our son was less given to joining a cause and shaking his fist. Being older, he also understood the difficulty of the issues better, and they depressed him, because he knew that children really could do very little. He’d been painfully aware of climate change throughout elementary school—first grade was devoted to recycling and sustainability, and in third grade, during a unit on Africa, he learned that every wild animal he loved was facing extinction. “What are humans good for besides destroying the planet?” he asked. Our daughter wasn’t immune to the heavy mood—she came home from school one day and expressed a wish not to be white so that she wouldn’t have slavery on her conscience. It did not seem like a moral victory for our children to grow up hating their species and themselves.

We decided to cut down on the political talk around them. It wasn’t that we wanted to hide the truth or give false comfort—they wouldn’t have let us even if we’d tried. We just wanted them to have their childhood without bearing the entire weight of the world, including the new president we had allowed into office. We owed our children a thousand apologies. The future looked awful, and somehow we expected them to fix it. Did they really have to face this while they were still in elementary school?

I can imagine the retort—the rebuke to everything I’ve written here: Your privilege has spared them. There’s no answer to that—which is why it’s a potent weapon—except to say that identity alone should neither uphold nor invalidate an idea, or we’ve lost the Enlightenment to pure tribalism. Adults who draft young children into their cause might think they’re empowering them and shaping them into virtuous people (a friend calls the Instagram photos parents post of their woke kids “selflessies”). In reality the adults are making themselves feel more righteous, indulging another form of narcissistic pride, expiating their guilt, and shifting the load of their own anxious battles onto children who can’t carry the burden, because they lack the intellectual apparatus and political power. Our goal shouldn’t be to tell children what to think. The point is to teach them how to think so they can grow up to find their own answers.

I wished that our son’s school would teach him civics. By age 10 he had studied the civilizations of ancient China, Africa, the early Dutch in New Amsterdam, and the Mayans. He learned about the genocide of Native Americans and slavery. But he was never taught about the founding of the republic. He didn’t learn that conflicting values and practical compromises are the lifeblood of self-government. He was given no context for the meaning of freedom of expression, no knowledge of the democratic ideas that Trump was trashing or of the instruments with which citizens could hold those in power accountable. Our son knew about the worst betrayals of democracy, including the one darkening his childhood, but he wasn’t taught the principles that had been betrayed. He got his civics from Hamilton.

Read: Civics education helps create young voters and activists

The teaching of civics has dwindled since the 1960s—a casualty of political polarization, as the left and the right each accuse the other of using the subject for indoctrination—and with it the public’s basic knowledge about American government. In the past few years, civics has been making a comeback in certain states. As our son entered fifth grade, in the first year of the Trump presidency, no subject would have been more truly empowering.

“If you fail seventh grade you fail middle school, if you fail middle school you fail high school, if you fail high school you fail college, if you fail college you fail life.”

Every year, instead of taking tests, students at the school presented a “museum” of their subject of study, a combination of writing and craftwork on a particular topic. Parents came in, wandered through the classrooms, read, admired, and asked questions of students, who stood beside their projects. These days, called “shares,” were my very best experiences at the school. Some of the work was astoundingly good, all of it showed thought and effort, and the coming-together of parents and kids felt like the realization of everything the school aspired to be.

The fifth-grade share, our son’s last, was different. That year’s curriculum included the Holocaust, Reconstruction, and Jim Crow. The focus was on “upstanders”—individuals who had refused to be bystanders to evil and had raised their voices. It was an education in activism, and with no grounding in civics, activism just meant speaking out. At the year-end share, the fifth graders presented dioramas on all the hard issues of the moment—sexual harassment, LGBTQ rights, gun violence. Our son made a plastic-bag factory whose smokestack spouted endangered animals. Compared with previous years, the writing was minimal and the students, when questioned, had little to say. They hadn’t been encouraged to research their topics, make intellectual discoveries, answer potential counterarguments. The dioramas consisted of cardboard, clay, and slogans.

Illustration of a school desk with gold stars overlaid on top

Paul Spella

8.

students in new york city public schools have to apply to middle school. They rank schools in their district, six or eight or a dozen of them, in order of preference, and the middle schools rank the students based on academic work and behavior. Then a Nobel Prize–winning algorithm matches each student with a school, and that’s almost always where the student has to go. The city’s middle schools are notoriously weak; in our district, just three had a reputation for being “good.” An education expert near us made a decent living by offering counseling sessions to panic-stricken families. The whole process seemed designed to raise the anxiety of 10-year-olds to the breaking point.

“If you fail a math test you fail seventh grade,” our daughter said one night at dinner, looking years ahead. “If you fail seventh grade you fail middle school, if you fail middle school you fail high school, if you fail high school you fail college, if you fail college you fail life.”

We were back to the perversions of meritocracy. But the country’s politics had changed dramatically during our son’s six years of elementary school. Instead of hope pendants around the necks of teachers, in one middle-school hallway a picture was posted of a card that said, “Uh-oh! Your privilege is showing. You’ve received this card because your privilege just allowed you to make a comment that others cannot agree or relate to. Check your privilege.” The card had boxes to be marked, like a scorecard, next to “White,” “Christian,” “Heterosexual,” “Able-bodied,” “Citizen.” (Our son struck the school off his list.) This language is now not uncommon in the education world. A teacher in Saratoga Springs, New York, found a “privilege-reflection form” online with an elaborate method of scoring, and administered it to high-school students, unaware that the worksheet was evidently created by a right-wing internet troll—it awarded Jews 25 points of privilege and docked Muslims 50.

The middle-school scramble subjected 10- and 11-year-olds to the dictates of meritocracy and democracy at the same time: a furiously competitive contest and a heavy-handed ideology. The two systems don’t coexist so much as drive children simultaneously toward opposite extremes, realms that are equally inhospitable to the delicate, complex organism of a child’s mind. If there’s a relation between the systems, I came to think, it’s this: Wokeness prettifies the success race, making contestants feel better about the heartless world into which they’re pushing their children. Constantly checking your privilege is one way of not having to give it up.

On the day acceptance letters arrived at our school, some students wept. One of them was Marcus, who had been matched with a middle school that he didn’t want to attend. His mother went in to talk to an administrator about an appeal. The administrator asked her why Marcus didn’t instead go to the middle school that shared a building with our school, that followed the same progressive approach as ours, and that was one of the worst-rated in the state. Marcus’s mother left in fury and despair. She had no desire for him to go to the middle school upstairs.