#i was? very interested in the notion of a victim of a tragedy being able to express their grief & their loss after their death

Text

#one day i'll make a meta abt how the entire school shooting subplot truly was pointless

okay today’s the day! ten whole seconds later. idk if this is an unpopular opinion, i don’t really care. the school shooting subplot was? one of the 59827925 subplots in this show that absolutely could have been dropped.

first off, after the halloween ep, we never see the kids’ ghosts again. we don’t see them in the library after violet talks to the librarian. v..iolate doesn’t even actually break up after she learns he shot up a school. like she does kill herself? but honestly i don’t think we needed an entire fucking school shooting subplot & graphic scene for this to happen like. violet’s life is shit.

second, god does this overkill tate’s character. he’s 1.) set his mom’s boyfriend on fire (justifiable lmao i don’t feel bad for larry) 2.) shot up his school 3.) killed chad & patrick 3.) r*ped vivien and 4.) fathered the antichrist like. ryan? are you aware you can have more than one villain in your horror show? dear g o d. frankly, if they kept in everything but the school shooting out of that list? i wouldn’t complain as much. a lot of them fit tate’s character during the season; he does really shitty things under this guise of helping people he cares about, like nora and beau. this shooting? sticks out like a sore thumb. he says he kills people he likes, to take them someplace “clean”, but we never seen him attempt to kill, say, addie outside of the house so she can go someplace better.

third: like almost every other nod to real life people & events on this show, the westfield massacre is literally ryan showing off how much he “”knows”” (debatable lmao) about history. we get it ryan, you’ve heard of c*lumb*ne (censoring the fuck out of that so the fangirls don’t find me). the amount of kids tate killed is the same amount of children that died during that tragedy; at one point, stephanie says tate asked her if she believed in god, something that turned out not to be true, another detail of the rl case.

the worst part about this is that there is this dragged out scene at the beginning of episode 6 where we literally? see the shooting in the library in real time. for god knows how many minutes, we have to watch pretend children face the fact they’re gonna die, all while the show is like “hey, it’s just like c*lumb*ne!” it’s nasty, in my pov. and i’ll never get over them censoring the mass shooting scene in cult after the vegas tragedy (a probably wise move, tbh) when that is? not the first time this show has pulled this shit. but c*lumb*ne had happened 12 years before mh, so i guess that was “enough time”, in their pov, to shoot the scene as they did.

#this is long and rambling & you don't have to agree#'but ashley; you write chloe so what's the deal w/ that'#i was? very interested in the notion of a victim of a tragedy being able to express their grief & their loss after their death#bc that's obviously a pov we can't get when tragedies happen; we can't ask the dead#god this is gonna get deleted i know it but lmao here we go!#read it while it's hot!#⊱ ❛ *sally mckenna vc* i goddamn live here !! ❜ ooc posts & replies .#school shooting /#rape ment /#true crime ment /#wank /

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

penny for your thoughts on salmondean codependency ?

Sure. Fair warning it’s long (was longer but I stopped myself.)

I think it’s complicated in a show that’s had so many different showrunners because they’ve all handled Sam and Dean’s relationship very differently. In Kripke’s era (s1-5) there was a romanticization of the bond. Sure there was a lot of in-depth exploration of how they wound up at the place they were at, spoiler alert: it was all because of John and his obsessive crusade to find the demon that killed his wife. That’s all he cared about and as a result, Sam and Dean had to be everything to each other. But Kripke had no intention of dismantling that at any point because he was (and always had been) writing a tragedy. Gamble continued that too. There was no room for anyone else in their lives and it would always just be the two of them against the world. So Cas had to go. Bobby had to go.

(Actually, it's funny because Gamble didn't intend this at the time, her plan was to kill Cas off, but by Edlund creating the masterpiece that is The Man Who Would Be King, he not only saved Cas from being seen as a villain, but he also deepened Dean and Cas' relationship in such a profound way and inextricably linked the two of them emotionally. And since Cas was eventually brought back, that laid the foundation for a lot of what their relationship would become.)

Up until this point, there hadn’t really been any significant dismantling of perhaps the more unhealthy parts of Sam and Dean’s relationship. Enter Carver. He stripped things down and started to explore what drove these characters. What they wanted and why they couldn’t have it. It starts with Dean being mad at Sam for not looking for him in purgatory, which sets up the whole speech in the s8 finale of Sam’s guilt about letting Dean down, but the thing is, Dean was never honest with Sam about his year away either. He never told Sam he could have gotten out much sooner if he hadn’t stayed to find Cas. I mean Dean had assumed Sam was up there alone doing God knows what to try to bring him back, and yet still he stayed in Purgatory because things were clear there. He needed Cas. Anyway, I just find that interesting, but Cas isn’t a victim of Sam and Dean’s relationship in s8.

Who gets the honour of being cast aside? That would be Benny and Amelia, two characters they introduced in s8 specifically to highlight that Sam and Dean’s relationship doesn’t allow for anyone else to be a significant part of their life. I mean that’s nothing new, we’ve watched that happen many times before. Lisa even said as much to Dean. The thing is this time? It’s framed as a truly sad thing. That moment at the end of 8x10 when Dean has just ended things with Benny and Sam leaves Amelia, and they’re sitting alone drinking beer and watching tv is such a hollow empty moment. This is not what they want. But it’s the way things have to be.

I’m actually fascinated by Sam and Dean’s conversation in the church in the s8 finale. Not so much Dean’s assertion that there is no one else he would put before Sam, but more so what provokes it, which is Sam saying “who are you going to turn to instead of me. Another angel? Another vampire?” See the thing is Dean saying he would always put Sam first is not news. We know this and it’s not really an unhealthy statement in itself either. A lot of people would put their sibling above anything else, not less a sibling who you raised and is the most important person to you. But in this context? After what Sam said? It just highlights how unhealthy they are if Sam believes that Dean having other people in his life means he doesn’t love him enough. That he’s a disappointment to him. That’s so profoundly fucked up.

(Note, Dean tells Sam that he killed Benny for him but he doesn’t say anything about Cas. I think like I said before, this is because Cas and Dean’s relationship has largely existed out of the Sam and Dean stuff up to this point - Sam and Cas don’t even really have much of a relationship yet besides both of their connections to Dean.)

And then from here, things start getting steadily worse. But we also keep being shown how bad they are. Dean lying to Sam, taking away his free will by letting Gadreel possess him. Dean sending Cas away, Kevin dying. It’s all awful. The whole “there ain’t no me if there ain’t no you line” from 9x01 isn’t really said by Dean, it’s Gadreel, but that is how Dean feels. He does think that’s all he’s good for. And over the season we’re shown how much of himself and what he truly wants he’s had to give up because of his ingrained “Save Sammy” and “Sammy comes first” mentality. It’s always been this way for him. In 9x07 we see that he had found a happy home, a good father figure, and his first love, a first love might I add that he had to leave behind with no real explanation because Sam needed him, and Sam comes first.

I mean just one episode earlier we had him rushing out the door elated about seeing Cas and spending time with him, only for their time together to come to sad and melancholic end when Dean once again leaves Cas behind without any real explanation, because despite what he wants Sammy comes first. What he wants doesn’t matter.

See I think after the Gadreel stuff comes out is where the narrative starts to get a little wonky for me. You can clearly see that this was intended to be a shorter story that they ended up stretching out to a much longer one because of renewals. There’s also the fact that this is a formula show so they can’t necessarily be separated for longer than an episode or two. S10 is a rough one to get through at times, I think the themes still mostly hold up but it’s a rough one to get through.

S10 highlights all the connections that Dean has, Cas, Charlie, Crowley even, but Sam doesn’t really have those bonds in the same way. For Sam it’s just Dean, so he goes down a reckless destructive “do anything to save Dean!” path and so many innocents pay the price, and ultimately with the release of The Darkness, the whole world.

They skirted right up to the edge of exploring just how toxic and dangerous their relationship had become in the season 10 finale.

DEAN: I let Rudy die. How was that not evil? I know what I am, Sam. But who were you when you drove that man to sell his soul... Or when you bullied Charlie into getting herself killed? And to what end? A..a good end? A just end? To remove the Mark no matter what the consequences? Sam, how is that not evil? I have this thing on my arm, and you're willing to let the Darkness into the world.

I can’t say evil is the right word, they were never evil, but they were wilfully blind to everything and everyone else when it came to saving each other. S10 tested my love for the show because after watching it, because there was certainly a feeling that the two of them had become the villains of this story. And don’t get me wrong, I didn’t have a problem with that, it’s just after 2 seasons of this I can’t say I had a lot of faith that this was going to be properly addressed or if we were going to keep going in circles around it. Keep being shown, it’s bad and then nothing much being done to fix it. Your mileage may vary on how it was handled, but I think s11 did a relatively ok job considering it wasn’t the end of the story, and the show needed to keep going.

See from Dean’s side a lot of the codependency rests on

1. His father’s orders to always save Sammy

2. His low self-esteem where he sees himself as nothing but a blunt instrument.

3. His guilt at not being able to perfectly fulfil every familial role in Sam’s life

4. His belief that no one could choose to love him but family has to love you.

5. The unhealthy example of what it should look like to love someone that he got from John. You give up everything but them.

For Sam (and honestly it’s not as clear for me as Dean’s side is so feel free to correct me/disagree on this)

1. Everytime he’s tried to leave and create his own life it’s never ended well.

2. His guilt over wanting freedom and a normal life when he was younger (I’m referring specifically to Stanford era here)

3. His guilt over everything Dean has given up for him.

4. John.

5. Jess.

Ultimately it all comes down to isolation. They both had to be everything to each other, and the deeper they got into this fight, the more people that they lost, the tighter they clung to this notion of family and brothers. I think s11 (and 11x23 in particular) was an important turning point, both for Sam and Dean’s relationship, as well as for them as individuals. Because they weren’t alone there anymore. Cas was there. Sam let Dean walk to his death. Of course, it would devastate him, but he knew it was what had to be done. And he didn’t walk out of that bar and go back to the bunker alone. He had Cas, he had someone who cared about him and wanted to help him and talk to him. Sure Dean asked Cas to take care of Sam for him (you know after Cas offered to walk to his death with him) but Sam let him. He let him be there for him. We didn’t get to see much before the BMOL showed up and blasted Cas away, but still, we saw enough.

I think that’s a significant difference to note why their relationship was different in the Dabb era. It wasn’t just them anymore. Cas was an important member of their family and given a level of importance he’d never been given before and couldn’t have been when the story they were telling was of the dangers of their codependency. Mary was back. Eventually, Jack would become a part of their unit too. Just the two of them wasn’t enough for them anymore. This is made abundantly clear with all of Dean’s desperate attempts to get Cas to stay in s12, followed by his inability to keep going when they lose Cas and Mary in s13. Similarly, Sam really struggles when they lose Jack and fail to get Mary back later in the season.

Another big moment is Dean letting Sam go alone to lead the hunters against the BMOL in 12x22 while he stays back to try and reach Mary. Like he tells Mary, he’s had to be a brother, a father and a mother to Sam and he never stopped seeing him as his kid, but in that moment he makes a choice. He lets Sam take charge and he shows that he trusts him and believes in him. He knows he can handle it.

Sometimes it’s not even a character growth thing. Sometimes having other people there stops you from making destructive choices even though that’s still your first instinct. I’m thinking specifically of 13x21 after Sam was killed. Dean would have run headlong into that nest of vampires and got himself torn apart, but Cas was there to stop him. He was able to make him see reason.

Basically, I think that for a long time, they thought the only relationship they could have was each other, which then became a self-fulfilling prophecy because their desperate attempts to keep each other around led to them losing the people around them. They eventually started to learn that that wasn’t true, they could have more, they were allowed to want more, and that it wasn’t an either-or situation. Dean didn’t have to choose between Sam and Cas. They didn’t have to choose between each other or Jack. The same goes for Mary. Different relationships can coexist without threatening each other, and not say that their relationship in s12-15 was all smooth sailing, but it was certainly so very different from everything that came before.

(There’s maybe a point to be made about how they didn’t have anyone or anything in the finale and how that relates to the story we got, but honestly I have no idea what the intention was with any of the choices made in that episode so I’ll leave it at that for now.)

985 notes

·

View notes

Note

What’s your opinion on the main characters in WH (like one for Nelly, one for Catherine etc)? Do you have a favourite and a least favourite?

There are a lot of main characters...I guess Nelly Dean, Heathcliff, Catherine Earnshaw, Cathy Linton, Hareton Earnshaw, and Linton Heathcliff? I feel bad cutting out Edgar and Isabella, they are important characters but I could easily write a thesis on each character and I don’t want to make this unbearably long (you’re going to regret asking me this as it is lol).

Nelly - She is not the “sensible soul” that she esteems herself to be. Compared to other characters she may seem discerning, but that’s partially because she’s just a witness to events that more deeply affect other characters. She can be very biased towards and against certain people, and her opinions tend to be fairly rigid. Her actions and convictions seem more an unconscious exhibition of societal norms of the time and her station in life; rather than her objective rational thinking. She certainly isn't immune to common superstition and small-mindedness. That being said, she is not the villain of the novel as critic James Hafley argued. She certainly isn’t heartless and cruel and she is motivated to do what she believes is the right thing to do. Overall I like her character.

Heathcliff - It's a testament to the complexity of his character that there is such a wide range of narratives on him…some I admittedly don’t understand. While a powerful force in the novel, I think he shows himself to be very human and fallible, and not the “ghoul” or “vampire” he is sometimes accused of being. It makes me laugh how many times I’ve seen critics say he is the human embodiment of the Heights but the first meeting of him it's literally said that he is a “singular contrast to his abode”? It’s also strange that his physical nature is often questioned by critics that reduce him to an elemental symbol, yet I would think Catherine is a better candidate to say she is more symbolic since we first encounter her in a dream and she is merely a memory/ghost in half the novel. Not to mention that throughout her life she displays a fixation on the spiritual and divine (not that I think she is symbolic either). I think he’s meant to be read as a human, not a devil or a symbol, and it makes it more interesting to read him as such. He can be sarcastic and witty and also utterly devoid of humor. His pain and loss is tragic yet his anger and hatred is fearsome. He plans to enact revenge over decades and (kind of) succeeds yet he also is so short-sighted and often misjudges characters and situations. He’s a villain and a victim and never plays either part in exactly the way you’d expect. Despite all this, he never feels inconsistent or out of character.

Catherine - I’m such a broken record on her lol. We get a lot of negative opinions about her from Nelly but everyone else loves her? So I think it’s worth questioning what Nelly says about her. I don’t agree with popular narratives that exaggerate how terrible she is. She is certainly proud, quick-tempered, and her strong, unrelenting nature is unique for any character and even more so for a woman. These traits also make her Heathcliff’s natural counterpart, although she is never cruel in the way he can be, and she doesn’t seem to enjoy that side of his character either. I think audiences/readers often forget the better parts of her character, such as her love for her father regardless of his constant admonishments, her love of Heathcliff despite his harshness and his wrongdoings, and her brother Hindley in spite of all his cruelty. The tragedies of the novel are not her fault as it has sometimes been suggested.

Hareton - It is interesting his character probably has the most physical descriptions and I’d say is the most flatteringly portrayed male character. Yes, he starts off being described as brutish by Lockwood, but we later get many moments showing he also has a gentleness. His faults are normally immediately shown as not wholly his doing and I’d say he has the most character growth, even more than Cathy. Cathy’s appearance gets a lot of mentions too, but because Lockwood is kind of a romantic and in a faraway, lonely place, it makes sense that he projects a lot of romantic notions on her. We don’t need to know that Hareton is good-looking but it’s certainly made known lol. I think it’s in part because Cathy’s and Hareton’s good nature are meant to be shown as desirable and Nelly certainly makes an aesthetic connection there in her descriptions of them. I really like his character, and how despite everything, and his initial pride, he tries repeatedly to help Cathy, even though it does nothing in gaining her good opinion and only puts him at odds with Heathcliff, who he sees as a father. He also shows that you don’t have to be the product of your upbringing.

Cathy - I really like how she tries to do the right thing and is good, yet doesn’t allow anyone (even Heathcliff) control her. She has faults but she’s able to grow from them. She also has a lot of similarities to her mother. For both Cathy and Hareton, I really dislike the idea that their move to Thrushcross is the symbolic win of culture over nature. That’s never made any sense to me and makes even less sense when you consider that Emily preferred nature, and the freedom and spirituality she found there, and not riches and formality. And after all, Cathy and Hareton are the successors of Catherine and Heathcliff. I can’t imagine they will become supremely refined, cultured, and gentle. Everyone forgets they are both wild and proud, and at their worst, they both physically hit the other - Cathy cuts Hareton with her whip, and years later Hareton hits her. This notion of their new domesticity comes from the narrative of the Heights = wildness and Thrushcross = respectability and progress, and I’ve mentioned before this also distorts our image of Isabella and mislabels her as a weak, refined, gentlewoman, even though she shows herself to be highly spirited. Sorry, got a little off-topic at the end there. I think they can forgive and learn to be kind to each other without equating it to them becoming genteel and upper-class. I don’t like that critics do this.

Linton - I get why he’s no one’s favorite character but I don’t hate him. He is tragic, despite the fact that he also very annoying and bratty lol. I understand why he doesn’t care to better himself, and it seems pretty clear his behavior is a cry for the safety and affection that has been missing in his life since his mother died. He’s a pawn in a game he doesn’t understand, and yet he’s very aware of his role as a pawn and that his life will be short and its meaning and worth are ascribed inasmuch as he can prove useful. It’s understandable that he would cling to Cathy and her kindness to him. Of course, some of his sufferings are his own making. It seems he could less lonely if he was perhaps a little kinder to Hareton who doesn’t seem to have a preconceived dislike of him but is pushed away by Linton’s snobbishness.

Favorite: That's a really difficult question. The simple answer is I love them all hah! It does change, but I do often go back to Catherine Earnshaw. Charlotte Bronte wrote that there is a “certain strange beauty in her fierceness” and I think that sums it up perfectly. The fact she dies tragically young and the closest we get to her as a narrator is the little bit of her diary Lockwood reads, and that her memory lives on so strongly with Edgar and Heathcliff, all make her a compelling figure. The fact that so many readers hate her also makes me like her more lol.

Least favorite: Everyone always says Linton and Joseph are the worst so I’ll say Zillah because she doesn’t get picked on enough lol. She literally didn’t realize Nelly was being held hostage and instead believes some bullshit story about her being lost in a marsh and assumes Heathcliff saved her?? She was terrible to Cathy - granted she had been proud and stiff-necked but she was clearly being held against her will? Like is Zillah just not at all aware of her surroundings? She doesn’t get Dr. Kenneth when Linton is dying and instead leaves Cathy alone crying in the stairway, supposedly out of fear of losing her job if she disobeys - yet she didn’t seem worried about that when she puts Lockwood in Catherine’s old bedroom? She also knowingly embarrasses Hareton when he shyly asks her to ask Cathy to read aloud for him - she immediately says that Hareton is the one asking for it. Zillah is just one of those people that has no self-awareness and no consideration for others beyond her self-preservation. So yeah she wins the spot of “least favorite” lol. I’m not sure if you meant my least favorite of the main characters? If so then it would have to be Linton just cause no amount of sympathetic feelings towards him makes him less annoying lol sorry.

#wuthering heights#there is probably a million grammatical errors but i hate rereading myself lol its like hearing a recording of my voice#thoughts

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Joker x Reader - “John Wick” Part 3

Y/N left The Organization 3 years ago for the one reason strong enough to make her settle down: love. But after tragedy crushed her to pieces, she decided to leave The Joker and seek refuge with an old friend and mentor - John Wick. Needless to say The King of Gotham can’t accept his wife running away without a word, especially since he didn’t have a chance to tell her things she might want to hear.

Part 1 Part 2

The Joker listens at the bedroom’s door, impatient to have a conversation with you. It seems you are engaged into a fervent phone call with Winston and figured he shouldn’t interrupt.

“Please, anything you can discover would be a great help! U-hum… U-hum… Thank you,” and you hang up, which queues your husband to walk into the room.

You completely ignore him, scrolling through the numerous text messages you sent to your connections; several are already answering back and hopefully you can get some news soon. The more people are involved into the project, the more chances to find Kase and untangle the mystery of what happened to him after he was removed from the car.

“You left me there,” The Joker sneaks in and closes the door behind him. “Luckily we had Wick with us so he gave me a ride.”

No reaction. He takes a deep breath, trying to get your awareness.

“I didn’t sleep with Evelyn; sex wasn’t the reason why I kept visiting her. I know how that asshole made it sound and he was totally out of line!”

You quickly glance at him, busy replying to Ares since you feel you’re going to explode soon.

“The only skill I was interested in is the fact that she is an excellent painter and a popular art smuggler, OK?” J raises his voice, sort of annoyed you neglect to participate into his monologue. “I did not cheat, alright?” he approaches his wife. “First of all: I’m VERY picky! Second of all: why would I want a woman everyone else had?! I don’t like used toys. Third: nobody’s been polishing my gun as you tastefully addressed the issue! I have one Queen and I married her!!”

A little bit of doubt in your eyes and he utilizes the opportunity.

“You said you saw me going to her house? I did! The Bowery King asked if it was for the last 6 months? Yeah, I did! You know why?!”

At least now The Joker got your attention: you play it cool but he guesses you’re torn apart by his confession.

Many unfortunate events crammed in lately and hating the man you love made life infinitely more unbearable.

“Why…?” you barely muster the strength to inquire and he sees it as a possibility to mend a few broken pieces; although you can hide your emotions well, J can still read between the lines.

Maybe that’s why he answers with another question:

“Do you realize there are just three Monet paintings in circulation on the black market in the entire world? You admire his work and it took a lot of effort and a substantial fortune to acquire The Water Lily Pond painting. Evelyn Black helped with the transaction, then I had her make some modifications to the original masterpiece.”

You keep staring at The King of Gotham, uncertain about the stuff being tossed your way: is he lying or telling the truth?... In your line of work translating feelings is a huge part of the job; ultimately you had the best mentor to teach you the ropes when you started with the organization: none other than the legendary Baba Yaga. Despite his reputation and to your own amazement, John was one of the few hitmen with integrity and perfectly mastered the aptitude of not being a jerk. Such a rare gem… And blissfully unaware of it himself.

On the opposite end, The Joker is a jerk and flawlessly acquainted with his own “captivating” personality that made you fall in love with him anyway.

Also, doesn’t appear to be deceitful for the moment.

And you despise yourself even more for wanting to believe him.

“What… modifications?...” you throw him a bone and J is definitely not going to pass on the alternative of explaining his actions.

“I wanted to surprise you so I took advantage of Miss Black’s capabilities in the art field; I had her add small images to the authentic canvas: an evolution of you being pregnant, the nine frames culminating with a tenth: the new mother holding our son. Similar to a timeline,” he emphasize and you look intrigued, which might be a positive sign. “Needless to say it was tedious, difficult work, especially because she had to apply special pigments you can’t find at every corner of the street. Apparently you can’t mix old paint with contemporary shades, thus I had to order aged, special colors from Italy, Spain and France. That’s why I went to her place so often: I had to supervise the long process and make sure it turns out astonishing. Then…” and The Joker pauses,”…Kase was gone and I didn’t know what to do with my gift: bring it home or not? Would you have loved it? Would it make you sadder? I continued to drive to Evelyn’s and glare at the stupid painting for hours, undecided on what to do…”

J watches you bite on your cheek, then straightens his shoulders as you utter the words:

“… … … You ruined a genuine Monet?”

Your spouse might be a smooth talker when needed, yet he’s not wasting his versatility on this statement:

“I didn’t ruin it; I made it better!”

Silence from both parties. A good or bad omen? Hard to decipher the riddle with two individuals tangled into a relationship that somehow worked despite countless peculiarities meant to keep them apart.

“I have to talk to Jonathan,” you finally mutter and The Joker steps in front of you.

“Talk to me!”

“Unless you know the exact location of the suitcase full of gold coins he’s been safekeeping for me, I really have to speak to him. Or do you want to hammer the whole basement searching for it?”

Y/N walks out of the bedroom and J lingers inside, evesdropping on the conversation happening downstairs. He can’t understand the chat, but you are probably notifying John about the details your husband left out.

Might as well join the party, therefore The Clown pops up in the living room with a plea impossible to refuse:

“Hey Wick, can I stay here? I don’t care if you say no, I’m not going to leave.”

Your friend crosses his arms on his chest, focusing on the random topic:

“How could I deny such a polite request? Of course you can stay Mister Joker; my house is your house.”

You’re watching the free show unamused; usually it would make you smile…now you lack the depth for such connotations.

“Don’t get smart with me, Wick!” J growls and Jonathan pushes for a tiny, unnecessary quarrel.

“I’m not; although generally speaking, I fancy considering myself a smart guy.”

The Joker opens his mouth and you’re not in the mood for whatever the heck they’re initiating:

“I’m going to pump, then after you dig out the suitcase I’ll take half to the Bowery King,” you announce your plans to them.

“You can do that and rest; I’ll deliver the coins,” John immediately offers. “I can stop by Aurelio’s car shop and ask for his collaboration: he has a lot of associates, doesn’t hurt to get him involved. You have plenty of gold.”

“I have two more suitcases in the Continental’s safe and two more at The Penthouse. It doesn’t matter if it’s all gone as long as I can find my son.”

“I know gold coins are preferred; don’t forget we have a lot of money too,” J reckons with spite.

Is he reminding you or Jonathan?...

*************

Your husband spent the last hour in the garden, talking and texting with a lot of people; needless to mention he’s capitalizing on his network also. Winston disclosed Stonneberg’s contract is still opened, meaning the son of a bitch is out there; you have to scoop him before anybody else does.

“Y/N…” The Joker tiptoes in your quarters. “I thought you were taking a nap,” he huffs when he sees you at the edge of the bed.

You glare at the vial on the nightstand, sharing your idea for a future you wish will come true:

“I didn’t have my medicine in two days; I won’t take it anymore because if we get Kase back… I will nurse him. It all goes in the milk and I want to be able to feed my baby… Do you think his little heart is still beating?...” you sniffle and J is currently debating on a clever response since his mind is blank; one could deduce messing up is encoded in his DNA, but on such a huge scale… well, it gives new interpretations to the term even for him.

The grieving woman seeking reassurance for their loss is trying to make sense of the pointless occurrences that lead to Kase being an innocent victim and The Joker can’t render clarification: he has no clue why he asked her to marry him and why she said yes, it’s not that he’s husband material or a family man. Perhaps Y/N thought he could be… just enough to get by, that’s why she accepted his proposal.

Most women would have cringed at the concept. Most women. Not Y/N.

Most women would have flinched at the notion of having his baby. Most women. Not his wife.

Above all, she trusted J with their son and he treated the three weeks old like a trinket: didn’t drive him home because he had an important meeting, didn’t bother to assign escorting cars nor extra security. The King of Gotham took his child’s safety lightly and it definitely had severe consequences. Too late now to fix past mistakes... but he can attempt.

“You’ll be able to nurse him, OK?” he sits by you and hands over his cell. “Can you enter your phone number in here? Or am I not allowed to have the present digits?”

You’re hesitant and he slides the screen while you hold the gadget.

“Lemme help you,” The Joker sarcastically mumbles. “It should be the first on my list, right where the old number you canceled was.”

You exhale and fulfill his demand out of pure frustration when he squeezes in a second innocent petition.

“Chose my avatar.”

You grunt at his rubbish, scrolling through his folders for a picture anyway; J hopes the largest file will get your attention and that’s the point. How could Y/N miss it?!

Entitled “Baby”, the humongous cluster of pics contains 5,723 items. You open it quite absorbed by its size; what’s more puzzling is the collection depicting Kase’s ultrasounds, hundreds of frames with you being pregnant taken without you knowing: there’s a few when your ankles were so swollen you had to sleep with your feet up on 4 pillows, others with you munching on strange food you craved, more with you in the shower focused on your bump, a decent amount of couple selfies when you were sleeping and J had to immortalize the moment without waking you up and approximately 1,500 images of the newborn.

“You didn’t gross me out when you were pregnant,” The Joker reminds a teary Y/N. “Not sure why you would believe such aberration...” he pulls you on his knees and yanks the phone away, tossing it on the nightstand. “I would also like to underline I didn’t have an affair with Miss Black, alright?”

J lifts your chin up, forcing to look at him.

“Let’s put it this way: why would I fuck around with another woman when I have a wife at home that wants to kill me on a regular basis, hm? Where would the fun be? I mean, she didn’t pull the trigger yet but it’s exciting to hope she might. You know me: I’m a sucker for thrills!”

“Do I?”

“Huh?” J steals a kiss and you frown at his sleekness.

“Know you?”

“Yeah,” the green haired Clown acts composed while in fact his feathers are ruffled. Before you catch onto it he has to ultimately admit: “I’m sorry I didn’t drive the car… I should have…”

The Joker holds in his breath when your arms go around his neck very tight.

“I’m suffocating…” he grumbles. “I can’t tell if you’re trying to hug me or choke me to death,” J keeps on caressing your hair, prepared to block your attack in case you’re actually in killing mode.

This is the excitement he was speaking about: with you, one could never know until it’s a done deal.

“I bumped into Magnus at the Continental,” you give him a bit of space to inhale much needed air and The Joker is surprised at your revelation. “I had no idea about his scheme, otherwise I would have skinned him alive right on the hotel grounds! I wouldn’t have cared about the consequences!”

“I’m glad you didn’t,” J cuts you off and he can tell you’re getting mad; maybe you think he doesn’t give a damn but the reason is simple. “You would’ve been declared excommunicado for murder on neutral ground and I don’t want my wife to be the target of such punishment from the company she so proudly retired from. I need my partner!”

The King of Gotham touches your forehead with his as you whisper:

“I hate you!”

“Mmm, regarding this true love affirmation, I’m gonna need you to take a break from detesting me until we have Kase, then you can despise me full throttle again. Deal?” he extends the palm of his hand and you reluctantly shake it, not realizing you’re reacting to his nonsense. “Is that a smile?” J returns the favor with one of his creepy silver grins.

“No.”

“Liar,” he pecks your lips and can’t explain the weird feeling in his heart when you kiss him back.

*************

Jonathan enters the house and becomes suspicious after a few minutes: too much silence.

Omg! Did you and The Joker engaged into a brawling that ended up badly? Did you end each other?!

John frantically runs to the garage, nervous to see your car and J’s are still parked inside. Shit!

“Y/N?” he shouts, concerned about your fate; The Joker’s… irrelevant. Nobody in the garden, patio is empty also. Downstairs is deserted thus he rushes upstairs to your room. The door is not completely shut and he slowly pushes it, knocking.

“Y/N? Can I come in?”

The first thing he notices are clothes scattered on the floor, then he halts his movement at the sight of Y/N and her husband dozing off on the bed sideways: the naked bodies are covered with a blanket, but he can tell you’re snuggled in J’s arms.

Jonathan steps backwards, guilty of invading his guests’ privacy; he certainly didn’t expect to intrude in such a manner and softly closes the door, grateful it’s not what he feared.

You and The Joker are so worn out the sound of your phones vibrating on the nightstand doesn’t wake you from the deep sleep. Your numerous contacts keep replying back to the text messages, the most important one showing up on his cell: one of the people J reached to is Evelyn Black and the two sentence conversation lights up the screen.

“Let me know if you see Stonnenberg.”

“He’s here.”

Also read: MASTERLIST

You can follow me on Ao3 and Wattpad under the same blog name: DiYunho.

#the joker x reader#the joker fanfiction#the joker imagine#john wick imagine#john wick x reader#the joker jared leto#the joker suicide squad#the joker#joker#joker fanfiction#joker jared leto#mister j#Mistah J#Mr.J#dc#dcu

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

Not a strange question at all!

The allure of splatter and gore is a very tricky question, and difficult to explain—especially when we’re currently seeing an unwelcome resurgence of the oft-debunked, conservative, and antiquated notion that violent or “problematic” material is a direct cause of violent, transgressive, and antisocial behavior (and not, you know…the result of negative or lacking human contact during one’s formative years, victimization, trauma, economic hardship, dysfunctional environments, and the myriad of other possible contributing factors that birth violent individuals). Forgive me for this intro, but it has become harder to discuss gory films without touching upon this issue.

Violence—particularly in America—is a deeply-rooted cultural issue that can neither be easily solved, nor easily attributed to one particular cause. Placing the blame for violence on violent media is little more than scapegoating: A way for people to feel accomplished without ever addressing the root of the problem. When a few isolated individuals consume a piece of media and choose to emulate it, they are held up as evidence of causation, conveniently ignoring the millions upon millions of people who consume the same exact media, yet never cause harm.

So, what is the appeal of gore?

Well, one must first address whether the gore in question is only that on the silver screen. Personally, I have a low tolerance for real images of viscera. As a teenager, I saw my fair share out of morbid curiosity online, but that curiosity was sated, and no longer of interest to me. I still research and curate “shockumentaries” and “mondo” films, but more because of their relation and importance to the history and evolution of horror films.

As human beings, I suppose we are inherently curious about what goes on inside our own bodies, because it’s something that we cannot easily see. The inside of our own bodies is plagued by taboo.

We cannot take a knife, slice ourselves open in a few places, and investigate—it would cause us great personal pain and suffering. However, when you clip your toenails or pick off a scab, you might often take a moment to “play with” the resulting clipping or flake. Why? It was a part of you. It came off of your body, and now is available to be seen. You couldn’t get a great look at it from every angle while it was on you, but now you are able to, and so your curiousity gets the better of you, and you examine.

Another factor contributing to the popularity of gory films is disgust itself. Researcher Bridget Rubenking may have put it best in a study published in the Journal of Communication,

“Disgust, it is argued here, makes us feel bad—but it has functionally evolved over time to compel our attention, thus making it a quality of entertainment messages that may keep audiences engrossed and engaged.”

Simply put, if it disgusts us, it holds our attention. We also remember such scenes more than those following or preceding them, so it’s actually in the financial interest of filmmakers to occasionally rely on gore as a gimmick.

For people like me that have an interest in film itself, I am impressed with the skill and artistry involved. I am particularly attracted to older films that utilized practical effects (even if they’re not particularly realistic), because I enjoy seeing what the effects crew were able to accomplish. I also personally like more outlandish fare that explores possibilities and situations one wouldn’t find on liveleak. Monsters, aliens, body horror; What would it look like if you started turning into an insect, a plant, or even a clown? What if bizarre things started growing inside you? What if biology went haywire, and you became filled internally with hair?

We aren’t normally able to view blood or viscera without being party to pain or tragedy, and the things listed above have no basis in reality. Film serves as a medium to allow the public to experience vicariously those things we cannot experience in real life; oftentimes, things that we would never even want to. It is a valuable way in which we can recognize and come to terms with the darker aspects of life, as well as the darker side of our imaginations.

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rambling thoughts on Cass and on ending stories.

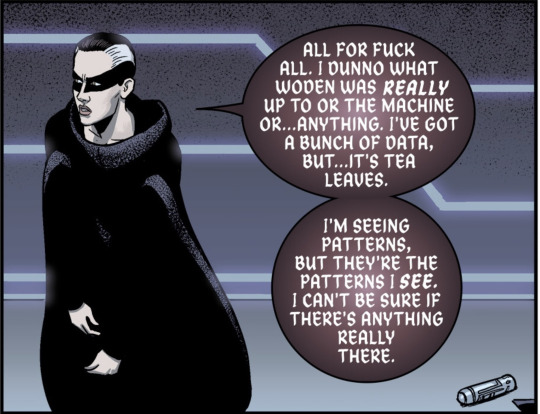

THE WICKED + THE DIVINE #32, written by Kieron Gillen, art by Jamie McKelvie, colors by Matthew Wilson, letters by Clayton Cowles

This panel sort of has it all.

Spoilers beneath the cut.

If there's only one way to end a story, and that way is to stop telling it, will it be enough for Laura to have rejected godhood? Or will the other surviving gods, including the heads, need to follow her example to ensure that Ananke cannot complete her ritual?

One can imagine Baph being convinced; he never wanted to die, never had a choice, and this would return some choice to him. Cass as well - the hospital footage on Dio's phone might even suggest that she survives past all this into old age. But what of Baal, who has always believed he was a god? Who has sacrificed in belief? Sunken cost fallacy there. Asking this of the heads - even of those who never wanted this - would be a tall order, moreover - for without godhood, what would they be other than victims of decapitation and thus dead? (Not that they would last long as heads under Minervananke.) Or was Ananke telling the truth when she said the children would develop powers on their own without her - where powers is not equal to the trappings of the god she chose for each, where the latter can be rejected as story and the former involves discovering identity of a sort?

In this context, I've been thinking a lot about Cass.

Cass interests me because of her fraught relationship to stories. She is constantly subjected to bigoted, racist, transphobic, objectifying stories imposed on her about gender and ethnic roles, not least by members of the Pantheon like Amaterasu and Woden. She is a critic who sees through that bullshit. She's defended her own story and gathered tools of defense. She's a journalist who wants to expose truths.

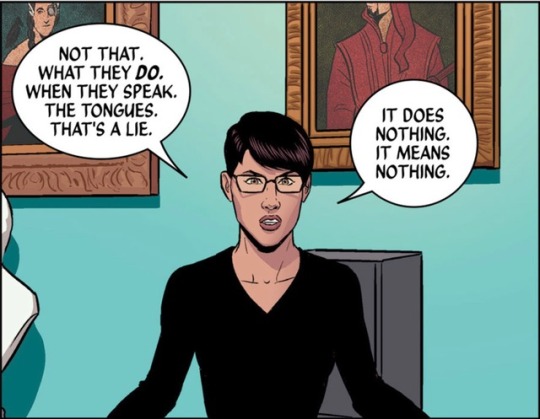

She's also someone who wants change in the form of progress and who seems to have once thought the gods would be the answer, if her academic degree in Pantheon Studies is any indication. But the gods of this Recurrence are themselves mouthpieces for the very same BS she has been subjected to all along. No change she would consider meaningful is taking place; instead we get the eternal recurrence of the same. When the gods speak in tongues, Cass is told she should feel something and yet does not. There is a story that her body and mind should be a certain way being imposed on her once again.

Cass rejects this narrative. The gods are not saviors, they're entitled teenage pricks. Their powers are meaningless. How she understands this exactly is a bit unclear to me. Does she think that the gods have never effected any meaningful change over the course of history, that their presence has had no effect? That would be a strange position for an academic historian. It seems more likely that she rejects the idea that the presence of the gods is inherently meaningful, that their appearance points to a deeper meaning in the structure of the world. The fact of Recurrence would itself be as meaningless as a meteor striking earth, for instance - the presence of the gods would mark no portent, no messianic coming, but simply be a fact of nature.

The stories about meaning imparted by gods - she says this with the portraits of 1831 Woden (Mary Shelley) and 1831 Lucifer (Lord Byron) in the background, possibly also referencing any sort of aestheticism as such, any sort of idea that art as such is a replacement for political action - were therefore lies.

THE WICKED + THE DIVINE #2, written by Kieron Gillen, art by Jamie McKelvie, colors by Matthew Wilson, letters by Clayton Cowles

For Cass, “the personal is the political”. (I tend to think of her as the opposite of idk the long-nineteenth-century German notion of Kultur writ large, but that's another story.)

Cassandra wants to change the world. That makes her position is VERY different from that of David Blake, whose problem with the Recurrence seems to also be that the current Pantheon reflects a society he doesn't want. Where Cassandra seeks a progressive future - her choice of name for herself speaks volumes - Blake acknowledges that the patriarchy is bad because: war and because: not every man gets to be the father with all the benefits, but also doesn't seem to care to change the status quo. On the contrary, some of his remarks suggest that he thinks culture was superior in the Past and that the Present should be violently struck from the history books. Even after Cass ascends to become Urdr, and thus associated with the Past, her thoughts remain directed towards the future. "We're trying to give birth to the future using the language of our oppressors", she tells Dio:

THE WICKED + THE DIVINE #27, written by Kieron Gillen, art by Jamie McKelvie, colors by Matthew Wilson, letters by Clayton Cowles

Ananke, Cass tells Laura, is "god of fate". Cass is the naysayer who doesn't believe in fate. In a perverse move, Ananke makes Cass into a goddess of fate. Cass is the sort who takes any thesis you give her and represents the anti-thesis with a "fuck you". Made goddess of fate, her response is to use those powers to persuade an audience of her view that there is no fate. The gods are a false hope and offer no meaning: "The void swallows us. Nothing means anything. Everything is nothing. Meaning is irrelevant. It's so cold. It lasts forever. It's all there is. So small so alone. We only have each other. It's never enough."

This is kind of a Birth of Tragedy moment: man gazes into the void, sees the horror of life, realizes nothing has meaning, and is paralyzed from action. Nietzsche thinks the paralysis can be overcome with art, particularly when the principles of individuation (the Apollonian drive) and inclusiveness (the Dionysian drive) are fused in a way that moves us to see past our own individual selves and figuratively unite with a collective. Cass is very Apollonian in a sense - she's tremendously restrained, a storyteller as opposed to a dancer and musician; that line about "small" and "alone" also stresses individuality. It's no wonder Dionysus is in this Pantheon and in love with Cass, and even briefly able to make her connect with his hive-mind. But Cass pulls out almost as soon as she starts to feel it, claiming there are more important things to do. There won't be the kind dialectic reconciliation of their respective art drives that Nietzsche would claim to be necessary in this story, unless Dio isn't really braindead.

My point with all this is that if you read Cass' message as something to live by, it seems rather one sided and incomplete. Is there a message she isn't sharing?If nothing means anything, why bother to perform? Cass doesn't go beyond the negation of meaning to think about what to do with that, how to live with that; there's a sense in which she does what she previously criticized about the tongues by not doing more than imposing a story, by not showing how to move beyond a story. She doesn’t ask her audience to think, but to download.

Cass tells a story of meaningless that is received as a story and nothing more. Much to her disappointment, it doesn't effect the kind of instant change in people's attitudes and mindset that she seems to think art should be capable of if it is to have meaning.

THE WICKED + THE DIVINE #10, written by Kieron Gillen, art by Jamie McKelvie, colors by Matthew Wilson, letters by Clayton Cowles

Instead of being provoked into thinking, or paralyzed with realization, however, what happens is quite a bit worse: her audience treats her message as a product to be consumed. Cass is again subjected to this fate when she decides to forgo the use of tongues - of giving any sort of aestheticized pleasure to her audiences - and hold a normal press conference where she yells unvarnished truths. Not only are her words ignored - the press conference is turned into reaction gifs to be reposted and repurposed without any attention paid to the original context or meaning - she herself is reframed as dangerous for even attempting to displace Woden's reigning narrative that pleasure is meaning and meaning is meaningful no matter how it was gotten or who it happens to keep in power. Not only is Cass' meaning deliberately twisted in Beth's video / power grab, the Valkyries are openly praised for stunning and imprisoning her and the other Norns.

Is Cass herself nothing more in the story than a tool for thinking through what art has possibly become in the culture industry on a meta level? That would be disturbing. I want to believe the story will give her more, that the raft of friendship we see her building with Laura is not about to be dashed to pieces and writ as futile as Dio’s last act.

The comment to Dio about trying to give birth using the language of oppressors seems really important. One of the literal oppressors in the story is Ananke, the perverted mother, the one who kills children and the future to ensure her own continued survival. (Palpatine and Cylo arguably also play this role in Gillen’s Vader comic, the former by scheming to replace his apprentice/figurative child with younger children in order to extend his power, the latter by endlessly cloning himself.) Ananke lives by a story and she thinks the story will carry her on. She murders the children born of the gods both literally and figuratively, ensuring she remains the only child.

If Ananke's language is that of the oppressor - and if Ananke’s sister stands for desire, she herself apparently stands for necessity - Cass uses that language by negating it. Cass' negations are at times absurdly absolute. When Amaterasu - her anti-thesis in so many ways - tells her that everything happens for a reason, she counters with the absolute: nothing happens for a reason.

THE WICKED + THE DIVINE #15, written by Kieron Gillen, art by Stephanie Hans, letters by Clayton Cowles

Cass is right about Amaterasu in a lot of ways. Amaterasu basically seems to be saying that Hiroshima had to happen so that she could happen. There’s a line in Marx about history repeating itself twice, once as tragedy, once as farce. Amaterasu recreating an artificial sun over Hiroshima was not in the least funny. Everything happens for a reason is a convenient philosophy if history has largely been on your side.

It's also rather determinist in a way, attributing necessity to everything regardless of how it affects people. Which makes Amaterasu's claim that Cass is an idealist who doesn't care about what happens to people rather rich:

THE WICKED + THE DIVINE #15, written by Kieron Gillen, art by Stephanie Hans, letters by Clayton Cowles

Amaterasu’s words are echoed later and more effectively by The Morrigan, who claims that her own choice to take away Baph’s choices was essentially the same as Cass’ choice to transform her girlfriends into Verdandi and Skuld. Cass protests that it was the logical, almost mathematically rational thing to do, which ... isn’t a great response ...

Speaking of idealism, Cass seems to impress Woden as well with the idea that she is a foolish idealist, whatever that means:

THE WICKED + THE DIVINE #30, written by Kieron Gillen, art by Jamie McKelvie, colors by Matthew Wilson, letters by Clayton Cowles

To say that nothing happens for a reason is not an idealistic statement by itself, though. If there's an ideal attached to it, it might be freedom - rejection of determinism. At the same time, Cass is certainly not an advocate for anarchy, as the vote on the Great Darkness makes clear. Cass thinks there is a right way to do things and a wrong way. If she believes that nothing happens for a reason because the idea of an inherent purposiveness to the world is a lie or a story we tell ourselves, her ideals also suggest that stories are part of who we are, that we are storytellers, that our minds are configured to see cause and effect, and that there is purpose to reflecting on what we are so we can do something with that. “I’m seeing patterns, but they’re the patterns I see” is a problem of which she is aware. There may not be meaning "out there", and that creates doubt - but it doesn’t keep her from doing.

Which makes it kind of a head-scratcher for me that neither Amaterasu nor Cass seem willing to acknowledge is that both of them can be right. We know this because Jon Blake - Mimir, a god of wisdom - puts forward a middle position:

THE WICKED + THE DIVINE #34, written by Kieron Gillen, art by Jamie McKelvie, colors by Matthew Wilson, letters by Clayton Cowles

It’s ironic that Cass, who claims nothing happens for a reason, is the one to fall for the idea that Ananke's machine must have a purpose, that it must do work. The machine does have a purpose - it misleads the gods, and above all, it has a purpose beyond its intended purpose, in that it keeps Cass inside, isolated, and distracted. Cass’ labor is sucked into the machine for the purpose of keeping the masses satiated and unthinking (Woden) and the perverse cycle of child murder uninterrupted (Minerva). The point being - someone had reason to hide the truth, just as she had reason to find it, and the recognition that stories are lies we tell ourselves for the purposes of survival doesn’t magically reveal truths or serve as an antidote or solution to the problems of society.

In this story about storytelling, this story about the meanings we choose to believe (“the personal is the political”, which full disclosure is also something I also believe), to act upon, to share or impose on the world and other people, the position that “nothing happens for a reason” is a difficult sell. Everything in this story was meticulously plotted, and any unintended effects on the reader can still be attributed to reasons. Given that the story is coming to an end in a very literal sense for both the reader and the characters, given that their story is to end a story, I’m really looking forward to seeing how Cass’ negations and ideals, how her approaches to art and stories are developed.

#wicdiv#the wicked + the divine#the wicked and the divine#cassandra igarashi#wicdiv urdr#hazel greenway#wicdiv amaterasu#kieron gillen#jamie mckelvie#stephanie hans#sethnakht rambles as usual#long post#sorry if this is completely incoherent#typed together over a period of days

75 notes

·

View notes

Text

due south: the ladies man (redux)

In the fall of 1998, I was a student of Derrida’s in his seminar at The New School for Social Research, “Justice, Perjury, and Forgiveness.” Despite the ambitious title, Derrida’s singular focus that semester was forgiveness. He was particularly interested in the notion that to be pardoned or forgiven is only actually meaningful in the face of the unpardonable, the unforgivable. To forgive someone for a minor mistake, or to say “pardon me” when accidentally bumping into a stranger on the street, is perhaps a nicety, a well-meaning mannerism or gesture, but where forgiveness is really needed — where it actually changes human relations — is where (and when) it is given to the unforgivable. In this way, the power of forgiveness depends upon the unforgivable.

Since then, I have maintained a correlated interest in the acceptance of the unacceptable, in the toleration of the intolerable, pairings that indicate a deeper problem; deeper in the sense that humans regularly accept the unacceptable (unlike forgiving the unforgivable). People regularly accept theoretically changeable facts of the world that are, even by their own accounts, totally unacceptable. Adjustments and acquiescence to unhappiness and dissatisfaction are common expectations of a practical life of “doing what one has to do,” and yet, it remains a basic ethical instinct to say that we should not accept a life that does us and others real measurable harm — at home, at work, in school, in society. And yet we regularly do. We do, that is, until there is a revolt against the unacceptable, against the intolerable.

richard gilman-opalsky, specters of revolt

this is an interesting section in the introduction to the book i’m reading. the book is mostly about revolt and its possiblities -- both the possibility of revolt haunting the capitalist world, but also the possibilities of what revolt can do.

but i think there’s something interesting in this passage -- and as someone who really struggles with derrida that’s not something i expected to find myself saying. after these two paragraphs, gilman-opalsky starts talking about revolt. which i am also interested in. but i do find myself thinking about the moments before. all the unforgivable moments before. before revolt; when revolt is a ghost, a potential body rather than a real physical force. and then i also think a lot about the idea that forgiveness given to the unforgivable has the power to change human relations.

which all relates back to my meta on what the ladies’ man in due south says about law enforcement and the US “justice system”.

because the bit i was struggling with the reading of the most was: the scene between beth botrelle and ray kowalski at the end of the episode. it’s not that i found it hard to reconcile it with the rest of the episode; on an emotional sense i understand why that scene is there. it’s about the system, not him. she understands... and also, it’s him facing a final, impossibly hard emotional truth. and... it’s ray giving the crime scene back to her, and making it back into a personal tragedy. or the scene of the crime done to her.

but on a craft sense; or on an ideological sense, i wondered exactly what the final embrace between them was saying. ray apologising multiple times; beth botrelle hugging him, and kissing him on the cheek. it’s a brutal, beautiful moment; why?

so i’ve been talking with @zielenna about this episode, and one of the other things that came up was the way in which it talks about masculinity, but especially through this very male police hierarchy. all of the cops around and especially above ray are men. the woman he has to fight to exonerate and her lawyer are both women -- and this is not a coincidence. no, it’s very much about patriarchal systems... the patriarchal arm of the state and the ways in which masculinity & homosocial relations are used to keep men in line, to keep them as enforcers of it.

there’s something also interesting that the dead guy is a male cop -- and a male cop who is named, in the episode’s title, as a “ladies’ man”. no, not a ladies’ man. he was “the ladies’ man”. there’s something there about virile masculinity, about how men admire other men who treat women badly.

and so when ray dissents from the ways in which the basic instinct of the police force is to cheer the woman’s execution, to bray for her blood (dewey operates here as a stand-in for the force at large) -- there is a sense in which that can be seen as a rejection of these structures of male power. by which i don’t mean that i’m reading ray as a radical feminist. but if we’re thinking about human relations, and the act of changing them at a time of emergency (and this episode is absolutely about a state of emergency), then it bears teasing out. he is absolutely rejecting a system of male power and personal relationships that intersect with and help strengthen this power.

this episode gives us a male mentor for ray kowalski, who up until now has had very little past beyond his family and ex-wife. a workplace mentor; a mentor who pretends to be supporting ray as a friend, but is actually out to save his own skin and consolidate his own power, his own power-network.

this is important; it shows us the figure of ray in a long line, in a huge interconnected network of men who will let this sort of thing happen. and it also shows the ways in which personal relationships between men will be used to strengthen this network; and the ways in which women and those who are outside and marginalised by the network... can and will be crushed by it.

ray’s only one link; when he consciously shatters that link, the network doesn’t fail. but he is able to save one person, in the face of this huge monolith.

so, let’s look at beth botrelle. in the first scene we see her in, her lawyer reinds her that she does not have to see ray. she can turn him away. not only does she choose to see him -- she insists that it’s alone, one-on-one. no lawyer, no fraser. it’s a personal connection. two people who can’t forget each other; and two individuals in a system that’s out to crush one using the other.

then there’s this:

Beth: So, you're looking for forgiveness?

[Ray still does not meet her eyes.]

Ray: Is that what you think?

ray does not ask for forgiveness. she doesn’t give it. what she does do is try to give him some kind of easy absolution, or a way to clear his conscience. “any cop could have taken that call,” she says. but ray knows that. and then she tells him that she killed her husband; and as soon as she says it, ray is certain that it’s not true. so she hasn’t given him absolution, or forgiveness. in lying, she has given him the truth -- or some portion of it.

let’s contrast this with the end of their final scene:

Ray (softly): I'm sorry.

Beth: No.

Ray: I am. I'm so sorry.

Beth (tearfully): No.

[She cups his face with one hand, then kisses his cheek.]

Beth: Thank you, Officer Kowalski.

[They embrace.]

there is one constant; beth botrelle is saying “no” when ray apologises, taking the responsibility upon himself. this isn’t so different to the way she tries to absolve him earlier. only, in the earlier scene she gives him all the cop platitudes she knows from her husband -- anybody could have taken that call, don’t let it wear on you. she lies. she is all give, willing him to take what she’s offering.

but it’s false; ray hasn’t done anything to earn it. he doesn’t take it; he can’t take it. she is the prisoner, and he is the cop. she’s an incarcerated woman, he’s the man whose role as a cop put her there. and not only is she incarcerated, she’s being touted everywhere as a “cop-killer” -- the people the system hates the most, because they have targeted the officers of that very system. even if, as beth botrelle didn’t, they did no such thing. despite beth asking that they be alone together, they can’t change the nature of their relations to each other.

in the final scene, everything has changed; except nothing that happened to beth has been taken away or removed. she still lived through an atrocity; she still had eight years of her life stolen from her. and that is -- unforgivable. both in the basic sense that it’s an awful, unimaginable thing that has happened to her. that has been done to her. but it is also unforgivable in the sense that she can’t forgive it; it’s impossible to grasp the totality of it, and all of the different people and systems and -- nodes in the network of power that created her fate. she can’t forgive it because they are not all there, it’s impossible to face them all. and it’s also unforgivable, specifically with ray kowalski, because he was one part of the larger system which failed her -- and not all of it. he is complicit, but he is not the root of the corruption.

does this make sense? i find myself doing that old essay trick of looking up the different, interconnected meanings of the word “forgive”. forgiving debt, giving up resentment towards -- and then. to pardon an offender.

because beth was thought to be an offender; she wasn’t one. because it’s the system and the state that can forgive offenders, and beth is a victim (a survivor) of the state’s violence. because ray did not commit an official offence against her; because those that did (the higher-up law enforcement officials) are not there. for all of these reasons, too, she is not able to forgive ray. because of the systems they exist within; because of the systems that shape their lives, and how they relate to each other.

and also just because of the unimaginable, horrifying scope of what was done to her, the way in which her life was destroyed.

so what does she do? she thanks ray. she kisses his cheek. she embraces him. this is not the words “i forgive you” -- and in fact, in the use of the repeated “no” we see her trying to absolve, rather than forgive. the idea that you have nothing to be sorry for equals i don’t need to forgive you.

but the first thing she thought ray was there for was forgiveness. and the last thing she does is she thanks him, and embraces him. a gesture of love; a gesture that nobody could have expected, a gesture that nobody outside the situation could perhaps easily understand.

so, i’m not a derridean, and if you’ve made it this far then you’ve probably guessed that? i’m not good with theory and i’m sure the phrase “human relations” has had a lot written about it (without even getting into the idea of forgiveness). but i’m not backing out from this now. in this passage, we see derrida’s ideas that forgiveness matters most in the face of the unforgivable; that this is when it is a radical act that can change human relations, which i read as relations between humans.

is her thank you and embrace -- forgiveness? is it absolution? does one have radical power that the other does not? or do both have a radical power in the face of all that has come before this moment? we have seen ray splintering the network that he was part of, that other male cops were trying to coerce him to remain committed to. and here he is, to a certain extent, cut loose from that. he is a person, again. alone with another person.

knowledge of the past power relations haunt this scene -- and of course there is still a power imbalance between them, even now. things have changed, but they have not changed enough. ray did all that he could; he is no longer slumped over in a chair in a prison. he has done something. he has changed something.

and it’s not enough -- because nothing could be enough. forgiveness is impossible. but in the face of the power relations that both hold them still, and haunt them, we see a radical act; an embrace. tenderness. halting, emotional honesty -- contrasting with the comforting lies she tells in the earlier scene. in the face of this system, which can perhaps only be saved by its total destruction, by revolt, by a radical, collective act -- this is what can be done to change power relations. an embrace. a few words. it’s not quite forgiveness; he still does not ask for forgiveness. he does not ask; she bridges the gap. personal tenderness; two people, who are trying to live as best as the world will let them. who are trying not to be defined by the roles in which their relative positions of power would have them. embracing in a way that is not about desire, or about one person’s power over another; embrace as transmission of emotion, empathy, understanding. when i started writing this, i thought it was forgiveness. i don’t think it is forgiveness; i don’t think it’s less of a gesture on beth’s part for that. because --

it’s not enough, and it’s not enough. of course it’s not enough; between two people in this situation, enough is not possible. between any amount of people in this situation, enough is not possible, because the atrocity was already committed. what is so upsetting, the reason why ray cries, is because her tenderness with him is not justified, is not reasonable. the maybe-forgiveness, the attempted-absolution. she can’t give it; and yet she gives it, or something like it. ray has done all that he can, and he does not deserve what she is giving him in return. what she is giving -- an act of love -- is radical in a way that he can’t answer in kind. which is why it’s so beautiful, which is why it’s so sad.

ray can’t be forgiven because he’s not responsible; and he can’t be forgiven because he was complicit. it’s a double-bind. and in the face of that knowledge; love. understanding. thank you. gratitude.

at the end, it’s gratitude. what is gratitude? kind words said, in earnest, in response to an imbalance -- in response to kindness, specifically an act of kindness which creates an imbalance between two parties. but here, the imbalance is insurmountable. the gap is so wide. it can’t be breached

the words fly tenderly across that gap anyway. thank you.

and so we have ray crying in his car -- we return to that image again. and of course there is so much more to be said about masculinity; about the ways in which it has been shed, and changed by ray’s relationship with beth. this is what a change in human relations means, this is what it can look like. so i have to end on it. ray, sobbing, unconsoled.

what is unforgivable cannot be forgiven; but that doesn’t mean it’s not a radical act to try.

#it's romance son#due south#look this is unforgivable sub-derridean nonsense from someone who does not know derrida#but i was having a terrible anxiety attack and writing this calmed me down#i am not clever enough!#you read this at your own risk!#overlong meta#my writing#unfortunately

31 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

see 14:15

Kirin J Callinan has always been an interesting figure for me, while I have enjoyed plenty of his music, it is his personas and multiple presentations of self that has consistently intrigued me. Kirin’s musical persona rides a wave of other australian artists such as Alex Cameron who are using their public image as a way to interrogate the multiple facets of hegemonic masculinity in the west. Their characters are often over the top, violent, macho, and obviously insecure and tender. Many narratives confess scumbag behavior and ultimately reveal the pathetic and weak nature of this archetype of male. This doesn’t function to apologize for or excuse the behavior of these men but to expose the comedy and tragedy underlaying this behavior, as well as exposing the structures in place that facilitate this mode of being.

Kirin however, goes deeper in this investigation though the utilization of characters and personas that in some way defy the norms of this male Archetype. Frequently flamboyant and androgynous, the persona put on by Kirin is highly considered.

In this interview with Anthony Fantano Kirin explains his rationale:

Q: “There seems to be a notion that you are a legitimate purveyor of toxic masculinity. From anybody that observes what you do, even casually, you don't seem to be a person that embraces a traditional aesthetic or ethos of masculinity at all. Where does this idea come from that you’re this kind of man’s man toxic machismo guy?

A: I’ve always been a very androgynous, effeminate, and fluid individual. And that’s what I think became quite boring for me to explore artistically, what seemed interesting was thinking back to the hyper masculine environment in high school, growing up in Australia. I must have been called f*ggot daily as a teenager and as a young man. Especially as a cross dressing, gender fluid person. Not that I’ve ever seen myself as a victim at all. On my debut studio album ‘Embracism’ it was quite interesting to me to explore these masculine ideas and to play that kind of character, so, barking into the microphone...Walking a sort of line that was both hyper masculine and effeminate or sensitive which I think i do naturally. I know who I am and what I represent and frankly no one else needs to.

Later in the interview Kirin clarifies that he is a “straight white guy” so I take his positions with a grain of salt but I found this approach kind of interesting. The idea of prodding and pushing of boundaries that have been imposed upon you , even if you are comfortable within them, will always seem like a valuable experience.

Im reminded of a time when two friends confronted me saying that I am making Gay art even though I’m straight. This really threw me. The work I was making at the time so (to me) so obviously exposed my confusion surrounding my sexual identity. They took it to be grotesque and satirizing gay love, to me it was a matter of reconciling the violent imposition of gender stereotypes on my being-with the new and uncomfortable feelings of uncertainty surrounding my sexuality. It is important to be prodding and challenging my fencings for both personal and political reasons.

Sexuality and gender are nebulous, as are our own sense of selves. I dont find the insistance that one should be able to apply a label of categorization to oneself in order to be accepted by the queer community as particularly productive. Postmodern and post structuralist though (which goes hand in hand with much of queer theory) teaches us to work against these ideas of binary signifiers. Therefore we should accept all aspects of fluidity and diversity across the spectrum of self identification as valid and productive. What use is there in adhering to the same binary thought we agree to work against?

ps. Of course these labels are important for communities in order to find safety and solidarity where there might otherwise be harm but this should not also be a violent act of gatekeeping

0 notes

Text

The Prerequisite For Healing The Nation: A Federal Job Guarantee

New Post has been published on https://perfectirishgifts.com/the-prerequisite-for-healing-the-nation-a-federal-job-guarantee/

The Prerequisite For Healing The Nation: A Federal Job Guarantee

An original Work Projects Administration sign from the 1930’s. The WPA was a huge part of the New … [] Deal during the Great Depression. Sign set on a blue/gray background. Canon 5D.

This is normally the time of month when I post commentary about the latest economic data, particularly the Employment Situation Report from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (speaking of which, unemployment inched down again, however less than expected). But I’m not sure that’s very important right now. We all know what’s happening: at the beginning of the year, the measures required to stem the tide of COVID infections caused post-World War Two highs in unemployment. As restrictions were eased, so unemployment fell. However, the winter months in the Northern Hemisphere are already bringing on new challenges and things may well get worse before they get better. But get better they will, it appears, as vaccines are starting to become available at this very moment.

While this is all very serious and newsworthy, there’s no mystery here that requires an economist’s perspective to unravel. I therefore decided to shift gears this month and talk about a broader issue, one that existed well before COVID and which has contributed materially to the deep political divisions in American today: the increasing income inequality that has marked the US economy since the 1970s.