#i really Don’t Like how jenny’s agency is just gone i need to figure out a way to fix that but in the meantime.. this is what i got orz

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

ok. dumping my scout’s mom is a rival spy au/headcanon storyline here.

scout’s mom (for the sake of this au her name is jenny) gets hired real young as a spy by blutarch administration because $$$ (get that bag jenny). she meets red spy (francois, also similarly young) and they have a friendly rivalry. this all takes place sometime during the 1920s-40s can’t decide yet.

sooner or later that friendship turns into romance and jenny wants to start a family and run away with francois. eventually francois comes around to the idea, but before they can go through with it, the administrator finds out and threatens to kill jenny if she leaves (she knows too much).

francois tries to reason with the administrator and suddenly, a lightbulb goes off in his head. he rushes to the engineer, wondering if he could make a lesser form of respawn where the user, instead of being reanimated, has their memories erased. engineer goes through with it and boom jenny has her memories erased and works 9-5 at a diner in boston.

a good amount of years pass, jenny now has six kids, and out of the blue, a french tom jones appears in her diner and asks her out. she of course agrees, and has never felt so in love before. it’s so familiar and strange at the same time, and she’s so taken by him in ways she never was with the other men (and women) she’s been with.

they have a kid and for some reason, their kid looks nothing like him. her baby reminds her of someone she saw in a dream, someone she can’t quite recall. and suddenly this outpouring feeling rushes out of her, overwhelmingly loud and soft. and she cradles her crying boy to her, tears streaking down her face. she doesn’t know why she’s so overcome with joy, with sadness, with love.

french tom jones (francois) looks at their kid and he is scared. because her baby looks so much like her and he knows, he just knows he’ll mess up again. just like he did before, when he erased her memories. he could’ve done more for her. he could’ve helped her, he should’ve done better. and now, here he is; in a face that isn’t his, hiding behind a mask crafted out of his own fear and self hatred. he carries that burden just like he carries everything else, and he can’t mess this kid up, he just can’t. he’s done enough already.

so he leaves without a word.

skip to twenty years later and francois has mastered the art of distance. lonely and hardened, he sneaks up behind a new enemy scout hired by blutarch. the boy turns around (and he is only just a boy. so similar and so strange and so familiar and so incredibly her) and he is stricken with silence.

and he tries his best to hate him, he tries his best to keep himself away, but the boy keeps finding his way back to him and he can’t do anything about it. he wonders why he finds her trailing behind him and thinks of how cruel fate is.

and jenny keeps waiting, and waiting, and waiting for her love to come back. for something that will never return, some part of her that was lost and will forever be lost until the end of time. for some reason, she still holds out hope. it’s instinctual, almost, and she knows it in her heart that he will come back.

so she sits and thinks of him while he tries to get rid of her, and he fails and fails and fails and he is a sad pitiful man who loves so very deeply. and he tries not to show it for he is a coward, and he is weak, but he can’t help his love for her. for their son. and he hates himself for it, because love is what washed her away from him in the first place.

tldr: don’t fall in love with a workplace rival

#i hope this makes sense i kinda got a little carried away there at the end#anyways yes i love the scout��s ma is a spy headcanon and here’s my two cents on it ‼️#i just think that jenny and francois are yuri goals hashtagreal#my thoughts#tf2#i still need to work out some things in this so not everything is final#i really Don’t Like how jenny’s agency is just gone i need to figure out a way to fix that but in the meantime.. this is what i got orz#jenny and francois

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

Millions of Americans Have Lost Jobs in the Pandemic — And Robots and AI Are Replacing Them Faster Than Ever

For 23 years, Larry Collins worked in a booth on the Carquinez Bridge in the San Francisco Bay Area, collecting tolls. The fare changed over time, from a few bucks to $6, but the basics of the job stayed the same: Collins would make change, answer questions, give directions and greet commuters. ��Sometimes, you’re the first person that people see in the morning,” says Collins, “and that human interaction can spark a lot of conversation.”

But one day in mid-March, as confirmed cases of the coronavirus were skyrocketing, Collins’ supervisor called and told him not to come into work the next day. The tollbooths were closing to protect the health of drivers and of toll collectors. Going forward, drivers would pay bridge tolls automatically via FasTrak tags mounted on their windshields or would receive bills sent to the address linked to their license plate. Collins’ job was disappearing, as were the jobs of around 185 other toll collectors at bridges in Northern California, all to be replaced by technology.

Machines have made jobs obsolete for centuries. The spinning jenny replaced weavers, buttons displaced elevator operators, and the Internet drove travel agencies out of business. One study estimates that about 400,000 jobs were lost to automation in U.S. factories from 1990 to 2007. But the drive to replace humans with machinery is accelerating as companies struggle to avoid workplace infections of COVID-19 and to keep operating costs low. The U.S. shed around 40 million jobs at the peak of the pandemic, and while some have come back, some will never return. One group of economists estimates that 42% of the jobs lost are gone forever.

This replacement of humans with machines may pick up more speed in coming months as companies move from survival mode to figuring out how to operate while the pandemic drags on. Robots could replace as many as 2 million more workers in manufacturing alone by 2025, according to a recent paper by economists at MIT and Boston University. “This pandemic has created a very strong incentive to automate the work of human beings,” says Daniel Susskind, a fellow in economics at Balliol College, University of Oxford, and the author of A World Without Work: Technology, Automation and How We Should Respond. “Machines don’t fall ill, they don’t need to isolate to protect peers, they don’t need to take time off work.”

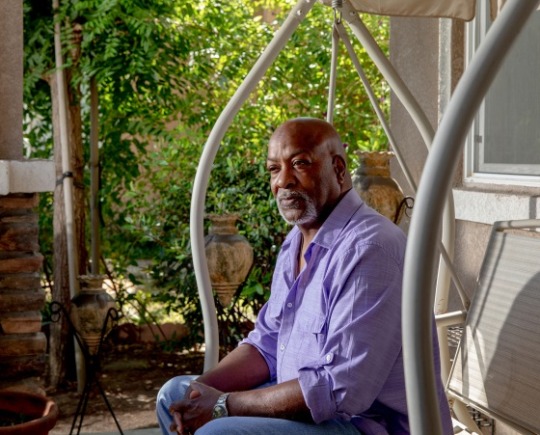

Larry Collins, at home in Lathrop, Calif., on July 31, was a bridge toll collector until COVID-19 led the state to automate the job to protect employees and drivers. “I just want to go back to what I was doing,” says Collins, whose job is among the millions that economists say could be lost forever as companies accelerate moves toward automation. — Cayce Clifford for TIME

As with so much of the pandemic, this new wave of automation will be harder on people of color like Collins, who is Black, and on low-wage workers. Many Black and Latino Americans are cashiers, food-service employees and customer-service representatives, which are among the 15 jobs most threatened by automation, according to McKinsey. Even before the pandemic, the global consulting company estimated that automation could displace 132,000 Black workers in the U.S. by 2030.

The deployment of robots as a response to the coronavirus was rapid. They were suddenly cleaning floors at airports and taking people’s temperatures. Hospitals and universities deployed Sally, a salad-making robot created by tech company Chowbotics, to replace dining-hall employees; malls and stadiums bought Knightscope security-guard robots to patrol empty real estate; companies that manufacture in-demand supplies like hospital beds and cotton swabs turned to industrial robot supplier Yaskawa America to help increase production.

Companies closed call centers employing human customer-service agents and turned to chatbots created by technology company LivePerson or to AI platform Watson Assistant. “I really think this is a new normal–the pandemic accelerated what was going to happen anyway,” says Rob Thomas, senior vice president of cloud and data platform at IBM, which deploys Watson. Roughly 100 new clients started using the software from March to June.

In theory, automation and artificial intelligence should free humans from dangerous or boring tasks so they can take on more intellectually stimulating assignments, making companies more productive and raising worker wages. And in the past, technology was deployed piecemeal, giving employees time to transition into new roles. Those who lost jobs could seek retraining, perhaps using severance pay or unemployment benefits to find work in another field. This time the change was abrupt as employers, worried about COVID-19 or under sudden lockdown orders, rushed to replace workers with machines or software. There was no time to retrain. Companies worried about their bottom line cut workers loose instead, and these workers were left on their own to find ways of mastering new skills. They found few options.

In the past, the U.S. responded to technological change by investing in education. When automation fundamentally changed farm jobs in the late 1800s and the 1900s, states expanded access to public schools. Access to college expanded after World War II with the GI Bill, which sent 7.8 million veterans to school from 1944 to 1956. But since then, U.S. investment in education has stalled, putting the burden on workers to pay for it themselves. And the idea of education in the U.S. still focuses on college for young workers rather than on retraining employees. The country spends 0.1% of GDP to help workers navigate job transitions, less than half what it spent 30 years ago.

“The real automation problem isn’t so much a robot apocalypse,” says Mark Muro, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution. “It is business as usual of people needing to get retraining, and they really can’t get it in an accessible, efficient, well-informed, data-driven way.”

This means that tens of thousands of Americans who lost jobs during the pandemic may be unemployed for years or, in Collins’ case, for good. Though he has access to retraining funding through his union contract, “I’m too old to think about doing some other job,” says Collins, who is 63 and planning on taking early retirement. “I just want to go back to what I was doing.”

Check into a hotel today, and a mechanical butler designed by robotics company Savioke might roll down the hall to deliver towels and toothbrushes. (“No tip required,” Savioke notes on its website.) Robots have been deployed during the pandemic to meet guests at their rooms with newly disinfected keys. A bricklaying robot can lay more than 3,000 bricks in an eight-hour shift, up to 10 times what a human can do. Robots can plant seeds and harvest crops, separate breastbones and carcasses in slaughterhouses, pack pallets of food in processing facilities.

That doesn’t mean they’re taking everyone’s jobs. For centuries, humans from weavers to mill workers have worried that advances in technology would create a world without work, and that’s never proved true. ATMs did not immediately decrease the number of bank tellers, for instance. They actually led to more teller jobs as consumers, lured by the convenience of cash machines, began visiting banks more often. Banks opened more branches and hired tellers to handle tasks that are beyond the capacity of ATMs. Without technological advancement, much of the American workforce would be toiling away on farms, which accounted for 31% of U.S. jobs in 1910 and now account for less than 1%.

But in the past, when automation eliminated jobs, companies created new ones to meet their needs. Manufacturers that were able to produce more goods using machines, for example, needed clerks to ship the goods and marketers to reach additional customers.

Now, as automation lets companies do more with fewer people, successful companies don’t need as many workers. The most valuable company in the U.S. in 1964, AT&T, had 758,611 employees; the most valuable company today, Apple, has around 137,000 employees. Though today’s big companies make billions of dollars, they share that income with fewer employees, and more of their profit goes to shareholders. “Look at the business model of Google, Facebook, Netflix. They’re not in the business of creating new tasks for humans,” says Daron Acemoglu, an MIT economist who studies automation and jobs.

The U.S. government incentivizes companies to automate, he says, by giving tax breaks for buying machinery and software. A business that pays a worker $100 pays $30 in taxes, but a business that spends $100 on equipment pays about $3 in taxes, he notes. The 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act lowered taxes on purchases so much that “you can actually make money buying equipment,” Acemoglu says.

In addition, artificial intelligence is becoming more adept at jobs that once were the purview of humans, making it harder for humans to stay ahead of machines. JPMorgan says it now has AI reviewing commercial-loan agreements, completing in seconds what used to take 360,000 hours of lawyers’ time over the course of a year. In May, amid plunging advertising revenue, Microsoft laid off dozens of journalists at MSN and its Microsoft News service, replacing them with AI that can scan and process content. Radio group iHeartMedia has laid off dozens of DJs to take advantage of its investments in technology and AI. I got help transcribing interviews for this story using Otter.ai, an AI-based transcription service. A few years ago, I might have paid $1 a minute for humans to do the same thing.

These advances make AI an easy choice for companies scrambling to cope during the pandemic. Municipalities that had to close their recycling facilities, where humans worked in close quarters, are using AI-assisted robots to sort through tons of plastic, paper and glass. AMP Robotics, the company that makes these robots, says inquiries from potential customers increased at least fivefold from March to June. Last year, 35 recycling facilities used AMP Robotics, says AMP spokesman Chris Wirth; by the end of 2020, nearly 100 will.

The Carquinez Bridge toll plaza in Vallejo, Calif., is empty of tollbooth collectors on July 30, the result of the state’s decision to automate the jobs at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. For now, workers are being paid in exchange for taking online courses in other fields, but that’s not a benefit available to most of the millions of U.S. employees who have lost jobs during the pandemic. -Cayce Clifford for TIME

RDS Virginia, a recycling company in Virginia, purchased four AMP robots in 2019 for its Roanoke facility, deploying them on assembly lines to ensure the paper and plastic streams were free of misplaced materials. The robots could work around the clock, didn’t take bathroom breaks and didn’t require safety training, says Joe Benedetto, the company’s president. When the coronavirus hit, robots took over quality control as humans were pulled off assembly lines and given tasks that kept them at a safe distance from one another. Benedetto breathes easier knowing he won’t have to raise the robots’ pay to meet the minimum wage. He’s already thinking about where else he can deploy them. “There are a few reasons I prefer machinery,” Benedetto says. “For one thing, as long as you maintain it, it’s there every day to work.”

Companies deploying automation and AI say the technology allows them to create new jobs. But the number of new jobs is often minuscule compared with the number of jobs lost. LivePerson, which designs conversational software, could enable a company to take a 1,000-person call center and run it with 100 people plus chatbots, says CEO Rob LoCascio. A bot can respond to 10,000 queries in an hour, LoCascio says; an efficient call-center rep can answer six.

LivePerson saw a fourfold increase in demand in March as companies closed call centers, LoCascio says. “What happened was the contact-center representatives went home, and a lot of them can’t work from home,” he says.

Some surprising businesses are embracing automation. David’s Bridal, which sells wedding gowns and other formal wear in about 300 stores across North America and the U.K., set up a chatbot called Zoey through LivePerson last year. When the pandemic forced David’s Bridal to close its stores, Zoey helped manage customer inquiries flooding the company’s call centers, says Holly Carroll, vice president of the customer-service and contact center. Without a bot, “we would have been dead in the water,” Carroll says.

David’s Bridal now spends 35% less on call centers and can handle three times more messages through its chatbot than it can through voice or email. (Zoey may be cheaper than a human, but it is not infallible. Via text, Zoey promised to connect me to a virtual stylist, but I never heard back from it or the company.)

Many organizations will likely look to technology as they face budget cuts and need to reduce staff. “I don’t see us going back to the staffing levels we were at prior to COVID,” says Brian Pokorny, the director of information technologies for Otsego County in New York State, who has cut 10% of his staff because of pandemic-related budget issues. “So we need to look at things like AI to streamline government services and make us more efficient.”

Pokorny used a free trial from IBM’s Watson Assistant early in the pandemic and set up an AI-powered web chat to answer questions from the public, like whether the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, the county seat, had reopened. (It had, as of June 26, with limited capacity.) Now, Watson can answer 75% of the questions people ask, and Otsego County has started paying for the service, which Pokorny says costs “pennies” per conversation. Though the county now uses AI just for online chats, it plans to deploy a Watson virtual assistant that can answer phone calls. Around 36 states have deployed chatbots to respond to questions about the pandemic and available government services, according to the National Association of State Chief Information Officers.

IBM and LivePerson say that by creating AI, they’re freeing up humans to do more sophisticated tasks. Companies that contract with LivePerson still need “bot builders” to help teach the AI how to answer questions, and call-center agents see their pay increase by about 15% when they become bot builders, LoCascio says. “We can look at it like there’s going to be this massive job loss, or we can look at it that people get moved into different places and positions in the world to better their lives,” LoCascio says.

But companies will need far fewer bot builders than call-center agents, and mobility is not always an option, especially for workers without college degrees or whose employers do not offer retraining. Non-union workers are especially vulnerable. Larry Collins and his colleagues, represented by SEIU Local 1000, were fortunate: they’re being paid their full salaries for the foreseeable future in exchange for taking 32 hours a week of online classes in computer skills, accounting, entrepreneurship and other fields. (Some might even get their jobs back, albeit temporarily, as the state upgrades its systems.) But just 11.6 % of American workers were represented by a union in 2019.

Yvonne R. Walker, the union president, says most non-union workers don’t get this kind of assistance. “Companies out there don’t provide employee training and upskilling–they don’t see it as a good investment,” Walker says. “Unless workers have a union thinking about these things, the workers get left behind.”

In Sweden, employers pay into private funds that help workers get retrained; Singapore’s SkillsFuture program reimburses citizens up to 500 Singapore dollars (about $362 in U.S. currency) for approved retraining courses. But in the U.S., the most robust retraining programs are for workers whose jobs are sent overseas or otherwise lost because of trade issues. A few states have started promising to pay community-college tuition for adult learners who seek retraining; the Tennessee Reconnect program pays for adults over 25 without college degrees to get certificates, associate’s degrees and technical diplomas. But a similar program in Michigan is in jeopardy as states struggle with budget issues, says Michelle Miller-Adams, a researcher at the W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research.

House and Senate Democrats introduced a $15 billion workforce-retraining bill in early May, but it hasn’t gained much traction with Republicans, who prefer to encourage retraining by giving tax credits. The federal funds that exist come with restrictions. Pell Grants, which help low-income students pay for education, can’t be used for nontraditional programs like boot camps or a 170-hour EMT certification. Local jobless centers, which receive federal funds, spend an average of $3,500 per person on retraining, but they usually run out of money early in a calendar year because of limited funding, says Ayobami Olugbemiga, press secretary at the National Skills Coalition.

Even if federal funding were widely available, the surge of people who need retraining would be more than universities can handle, says Gabe Dalporto, the CEO of Udacity, which offers online courses in programming, data science, AI and more. “A billion people will lose their jobs over the next 10 years due to AI, and if anything, COVID has accelerated that by about nine years,” says Dalporto. “If you tried to reskill a billion people in the university system, you would break the university system.”

Dalporto says the coronavirus should be a wake-up call for the federal government to rethink how it funds education. “We have this model where we want to dump huge amounts of capital into very slow, noncareer-specific education,” Dalporto says. “If you just repurposed 10% of that, you could retrain 3 million people in about six months.”

Online education providers say they can provide retraining and upskilling on workers’ own timelines, and for less money than traditional schools. Coursera offers six-month courses for $39 to $79 a month that provide students with certifications needed for a variety of jobs, says CEO Jeff Maggioncalda. Once they’ve landed a job, they can then pursue a college degree online, he says. “This idea that you get job skills first, get the job, then get your college degree online while you’re working, I think for a lot of people will be more economically effective,” he says. In April, Coursera launched a Workforce Recovery Initiative that allows the unemployed in some states and other countries, including Colombia and Singapore, to learn for free until the end of the year.

Online learning providers can offer relatively inexpensive upskilling options because they don’t have guidance counselors, classrooms and other features of brick-and-mortar schools. But there could be more of a role for employers to provide those support systems going forward. Dalporto, who calls the wave of automation during COVID-19 “our economic Pearl Harbor,” argues that the government should provide a tax credit of $2,500 per upskilled worker to companies that provide retraining. He also suggests that company severance packages include $1,500 in retraining credits.

Some employers are turning to Guild Education, which works with employers to subsidize upskilling. A program it launched in May lets companies pay a fee to have Guild assist laid-off workers in finding new jobs. Employers see this as a way to create loyalty among these former employees, says Rachel Carlson, the CEO of Guild. “The most thoughtful consumer companies say, Employee for now, customer for life,” she says.

With the economy 30 million jobs short of what it had before the pandemic, though, workers and employers may not see much use in training for jobs that may not be available for months or even years. And not every worker is interested in studying data science, cloud computing or artificial intelligence.

But those who have found a way to move from dying fields to in-demand jobs are likely to do better. A few years ago, Tristen Alexander was a call-center rep at a Georgia power company when he took a six-month online course to earn a Google IT Support Professional Certificate. A Google scholarship covered the cost for Alexander, who has no college degree and was supporting his wife and two kids on about $38,000 a year. Alexander credits his certificate with helping him win a promotion and says he now earns more than $70,000 annually. What’s more, the promotion has given him a sense of job security. “I just think there’s a great need for everyone to learn something technical,” he tells me.

Of course, Alexander knows that technology may significantly change his job in the next decade, so he’s already planning his next step. By 2021, he wants to master the skill of testing computer systems to spot vulnerabilities to hackers and gain a certificate in that practice, known as penetration testing. It will all but guarantee him a job, he says, working alongside the technology that’s changing the world.

Credits: ALANA SEMUELS

Date: AUGUST 6, 2020

Source: https://time.com/5876604/machines-jobs-coronavirus/

0 notes

Text

New story in Business from Time: Millions of Americans Have Lost Jobs in the Pandemic — And Robots and AI Are Replacing Them Faster Than Ever

For 23 years, Larry Collins worked in a booth on the Carquinez Bridge in the San Francisco Bay Area, collecting tolls. The fare changed over time, from a few bucks to $6, but the basics of the job stayed the same: Collins would make change, answer questions, give directions and greet commuters. “Sometimes, you’re the first person that people see in the morning,” says Collins, “and that human interaction can spark a lot of conversation.”

But one day in mid-March, as confirmed cases of the coronavirus were skyrocketing, Collins’ supervisor called and told him not to come into work the next day. The tollbooths were closing to protect the health of drivers and of toll collectors. Going forward, drivers would pay bridge tolls automatically via FasTrak tags mounted on their windshields or would receive bills sent to the address linked to their license plate. Collins’ job was disappearing, as were the jobs of around 185 other toll collectors at bridges in Northern California, all to be replaced by technology.

Machines have made jobs obsolete for centuries. The spinning jenny replaced weavers, buttons displaced elevator operators, and the Internet drove travel agencies out of business. One study estimates that about 400,000 jobs were lost to automation in U.S. factories from 1990 to 2007. But the drive to replace humans with machinery is accelerating as companies struggle to avoid workplace infections of COVID-19 and to keep operating costs low. The U.S. shed around 40 million jobs at the peak of the pandemic, and while some have come back, some will never return. One group of economists estimates that 42% of the jobs lost are gone forever.

This replacement of humans with machines may pick up more speed in coming months as companies move from survival mode to figuring out how to operate while the pandemic drags on. Robots could replace as many as 2 million more workers in manufacturing alone by 2025, according to a recent paper by economists at MIT and Boston University. “This pandemic has created a very strong incentive to automate the work of human beings,” says Daniel Susskind, a fellow in economics at Balliol College, University of Oxford, and the author of A World Without Work: Technology, Automation and How We Should Respond. “Machines don’t fall ill, they don’t need to isolate to protect peers, they don’t need to take time off work.”

Cayce Clifford for TIMELarry Collins, at home in Lathrop, Calif., on July 31, was a bridge toll collector until COVID-19 led the state to automate the job to protect employees and drivers. “I just want to go back to what I was doing,” says Collins, whose job is among the millions that economists say could be lost forever as companies accelerate moves toward automation.

As with so much of the pandemic, this new wave of automation will be harder on people of color like Collins, who is Black, and on low-wage workers. Many Black and Latino Americans are cashiers, food-service employees and customer-service representatives, which are among the 15 jobs most threatened by automation, according to McKinsey. Even before the pandemic, the global consulting company estimated that automation could displace 132,000 Black workers in the U.S. by 2030.

The deployment of robots as a response to the coronavirus was rapid. They were suddenly cleaning floors at airports and taking people’s temperatures. Hospitals and universities deployed Sally, a salad-making robot created by tech company Chowbotics, to replace dining-hall employees; malls and stadiums bought Knightscope security-guard robots to patrol empty real estate; companies that manufacture in-demand supplies like hospital beds and cotton swabs turned to industrial robot supplier Yaskawa America to help increase production.

Companies closed call centers employing human customer-service agents and turned to chatbots created by technology company LivePerson or to AI platform Watson Assistant. “I really think this is a new normal–the pandemic accelerated what was going to happen anyway,” says Rob Thomas, senior vice president of cloud and data platform at IBM, which deploys Watson. Roughly 100 new clients started using the software from March to June.

In theory, automation and artificial intelligence should free humans from dangerous or boring tasks so they can take on more intellectually stimulating assignments, making companies more productive and raising worker wages. And in the past, technology was deployed piecemeal, giving employees time to transition into new roles. Those who lost jobs could seek retraining, perhaps using severance pay or unemployment benefits to find work in another field. This time the change was abrupt as employers, worried about COVID-19 or under sudden lockdown orders, rushed to replace workers with machines or software. There was no time to retrain. Companies worried about their bottom line cut workers loose instead, and these workers were left on their own to find ways of mastering new skills. They found few options.

In the past, the U.S. responded to technological change by investing in education. When automation fundamentally changed farm jobs in the late 1800s and the 1900s, states expanded access to public schools. Access to college expanded after World War II with the GI Bill, which sent 7.8 million veterans to school from 1944 to 1956. But since then, U.S. investment in education has stalled, putting the burden on workers to pay for it themselves. And the idea of education in the U.S. still focuses on college for young workers rather than on retraining employees. The country spends 0.1% of GDP to help workers navigate job transitions, less than half what it spent 30 years ago.

“The real automation problem isn’t so much a robot apocalypse,” says Mark Muro, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution. “It is business as usual of people needing to get retraining, and they really can’t get it in an accessible, efficient, well-informed, data-driven way.”

This means that tens of thousands of Americans who lost jobs during the pandemic may be unemployed for years or, in Collins’ case, for good. Though he has access to retraining funding through his union contract, “I’m too old to think about doing some other job,” says Collins, who is 63 and planning on taking early retirement. “I just want to go back to what I was doing.”

Check into a hotel today, and a mechanical butler designed by robotics company Savioke might roll down the hall to deliver towels and toothbrushes. (“No tip required,” Savioke notes on its website.) Robots have been deployed during the pandemic to meet guests at their rooms with newly disinfected keys. A bricklaying robot can lay more than 3,000 bricks in an eight-hour shift, up to 10 times what a human can do. Robots can plant seeds and harvest crops, separate breastbones and carcasses in slaughterhouses, pack pallets of food in processing facilities.

That doesn’t mean they’re taking everyone’s jobs. For centuries, humans from weavers to mill workers have worried that advances in technology would create a world without work, and that’s never proved true. ATMs did not immediately decrease the number of bank tellers, for instance. They actually led to more teller jobs as consumers, lured by the convenience of cash machines, began visiting banks more often. Banks opened more branches and hired tellers to handle tasks that are beyond the capacity of ATMs. Without technological advancement, much of the American workforce would be toiling away on farms, which accounted for 31% of U.S. jobs in 1910 and now account for less than 1%.

But in the past, when automation eliminated jobs, companies created new ones to meet their needs. Manufacturers that were able to produce more goods using machines, for example, needed clerks to ship the goods and marketers to reach additional customers.

Now, as automation lets companies do more with fewer people, successful companies don’t need as many workers. The most valuable company in the U.S. in 1964, AT&T, had 758,611 employees; the most valuable company today, Apple, has around 137,000 employees. Though today’s big companies make billions of dollars, they share that income with fewer employees, and more of their profit goes to shareholders. “Look at the business model of Google, Facebook, Netflix. They’re not in the business of creating new tasks for humans,” says Daron Acemoglu, an MIT economist who studies automation and jobs.

The U.S. government incentivizes companies to automate, he says, by giving tax breaks for buying machinery and software. A business that pays a worker $100 pays $30 in taxes, but a business that spends $100 on equipment pays about $3 in taxes, he notes. The 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act lowered taxes on purchases so much that “you can actually make money buying equipment,” Acemoglu says.

In addition, artificial intelligence is becoming more adept at jobs that once were the purview of humans, making it harder for humans to stay ahead of machines. JPMorgan says it now has AI reviewing commercial-loan agreements, completing in seconds what used to take 360,000 hours of lawyers’ time over the course of a year. In May, amid plunging advertising revenue, Microsoft laid off dozens of journalists at MSN and its Microsoft News service, replacing them with AI that can scan and process content. Radio group iHeartMedia has laid off dozens of DJs to take advantage of its investments in technology and AI. I got help transcribing interviews for this story using Otter.ai, an AI-based transcription service. A few years ago, I might have paid $1 a minute for humans to do the same thing.

These advances make AI an easy choice for companies scrambling to cope during the pandemic. Municipalities that had to close their recycling facilities, where humans worked in close quarters, are using AI-assisted robots to sort through tons of plastic, paper and glass. AMP Robotics, the company that makes these robots, says inquiries from potential customers increased at least fivefold from March to June. Last year, 35 recycling facilities used AMP Robotics, says AMP spokesman Chris Wirth; by the end of 2020, nearly 100 will.

Cayce Clifford for TIMEThe Carquinez Bridge toll plaza in Vallejo, Calif., is empty of tollbooth collectors on July 30, the result of the state’s decision to automate the jobs at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. For now, workers are being paid in exchange for taking online courses in other fields, but that’s not a benefit available to most of the millions of U.S. employees who have lost jobs during the pandemic.

RDS Virginia, a recycling company in Virginia, purchased four AMP robots in 2019 for its Roanoke facility, deploying them on assembly lines to ensure the paper and plastic streams were free of misplaced materials. The robots could work around the clock, didn’t take bathroom breaks and didn’t require safety training, says Joe Benedetto, the company’s president. When the coronavirus hit, robots took over quality control as humans were pulled off assembly lines and given tasks that kept them at a safe distance from one another. Benedetto breathes easier knowing he won’t have to raise the robots’ pay to meet the minimum wage. He’s already thinking about where else he can deploy them. “There are a few reasons I prefer machinery,” Benedetto says. “For one thing, as long as you maintain it, it’s there every day to work.”

Companies deploying automation and AI say the technology allows them to create new jobs. But the number of new jobs is often minuscule compared with the number of jobs lost. LivePerson, which designs conversational software, could enable a company to take a 1,000-person call center and run it with 100 people plus chatbots, says CEO Rob LoCascio. A bot can respond to 10,000 queries in an hour, LoCascio says; an efficient call-center rep can answer six.

LivePerson saw a fourfold increase in demand in March as companies closed call centers, LoCascio says. “What happened was the contact-center representatives went home, and a lot of them can’t work from home,” he says.

Some surprising businesses are embracing automation. David’s Bridal, which sells wedding gowns and other formal wear in about 300 stores across North America and the U.K., set up a chatbot called Zoey through LivePerson last year. When the pandemic forced David’s Bridal to close its stores, Zoey helped manage customer inquiries flooding the company’s call centers, says Holly Carroll, vice president of the customer-service and contact center. Without a bot, “we would have been dead in the water,” Carroll says.

David’s Bridal now spends 35% less on call centers and can handle three times more messages through its chatbot than it can through voice or email. (Zoey may be cheaper than a human, but it is not infallible. Via text, Zoey promised to connect me to a virtual stylist, but I never heard back from it or the company.)

Many organizations will likely look to technology as they face budget cuts and need to reduce staff. “I don’t see us going back to the staffing levels we were at prior to COVID,” says Brian Pokorny, the director of information technologies for Otsego County in New York State, who has cut 10% of his staff because of pandemic-related budget issues. “So we need to look at things like AI to streamline government services and make us more efficient.”

Pokorny used a free trial from IBM’s Watson Assistant early in the pandemic and set up an AI-powered web chat to answer questions from the public, like whether the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, the county seat, had reopened. (It had, as of June 26, with limited capacity.) Now, Watson can answer 75% of the questions people ask, and Otsego County has started paying for the service, which Pokorny says costs “pennies” per conversation. Though the county now uses AI just for online chats, it plans to deploy a Watson virtual assistant that can answer phone calls. Around 36 states have deployed chatbots to respond to questions about the pandemic and available government services, according to the National Association of State Chief Information Officers.

IBM and LivePerson say that by creating AI, they’re freeing up humans to do more sophisticated tasks. Companies that contract with LivePerson still need “bot builders” to help teach the AI how to answer questions, and call-center agents see their pay increase by about 15% when they become bot builders, LoCascio says. “We can look at it like there’s going to be this massive job loss, or we can look at it that people get moved into different places and positions in the world to better their lives,” LoCascio says.

But companies will need far fewer bot builders than call-center agents, and mobility is not always an option, especially for workers without college degrees or whose employers do not offer retraining. Non-union workers are especially vulnerable. Larry Collins and his colleagues, represented by SEIU Local 1000, were fortunate: they’re being paid their full salaries for the foreseeable future in exchange for taking 32 hours a week of online classes in computer skills, accounting, entrepreneurship and other fields. (Some might even get their jobs back, albeit temporarily, as the state upgrades its systems.) But just 11.6 % of American workers were represented by a union in 2019.

Yvonne R. Walker, the union president, says most non-union workers don’t get this kind of assistance. “Companies out there don’t provide employee training and upskilling–they don’t see it as a good investment,” Walker says. “Unless workers have a union thinking about these things, the workers get left behind.”

In Sweden, employers pay into private funds that help workers get retrained; Singapore’s SkillsFuture program reimburses citizens up to 500 Singapore dollars (about $362 in U.S. currency) for approved retraining courses. But in the U.S., the most robust retraining programs are for workers whose jobs are sent overseas or otherwise lost because of trade issues. A few states have started promising to pay community-college tuition for adult learners who seek retraining; the Tennessee Reconnect program pays for adults over 25 without college degrees to get certificates, associate’s degrees and technical diplomas. But a similar program in Michigan is in jeopardy as states struggle with budget issues, says Michelle Miller-Adams, a researcher at the W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research.

House and Senate Democrats introduced a $15 billion workforce-retraining bill in early May, but it hasn’t gained much traction with Republicans, who prefer to encourage retraining by giving tax credits. The federal funds that exist come with restrictions. Pell Grants, which help low-income students pay for education, can’t be used for nontraditional programs like boot camps or a 170-hour EMT certification. Local jobless centers, which receive federal funds, spend an average of $3,500 per person on retraining, but they usually run out of money early in a calendar year because of limited funding, says Ayobami Olugbemiga, press secretary at the National Skills Coalition.

Even if federal funding were widely available, the surge of people who need retraining would be more than universities can handle, says Gabe Dalporto, the CEO of Udacity, which offers online courses in programming, data science, AI and more. “A billion people will lose their jobs over the next 10 years due to AI, and if anything, COVID has accelerated that by about nine years,” says Dalporto. “If you tried to reskill a billion people in the university system, you would break the university system.”

Dalporto says the coronavirus should be a wake-up call for the federal government to rethink how it funds education. “We have this model where we want to dump huge amounts of capital into very slow, noncareer-specific education,” Dalporto says. “If you just repurposed 10% of that, you could retrain 3 million people in about six months.”

Online education providers say they can provide retraining and upskilling on workers’ own timelines, and for less money than traditional schools. Coursera offers six-month courses for $39 to $79 a month that provide students with certifications needed for a variety of jobs, says CEO Jeff Maggioncalda. Once they’ve landed a job, they can then pursue a college degree online, he says. “This idea that you get job skills first, get the job, then get your college degree online while you’re working, I think for a lot of people will be more economically effective,” he says. In April, Coursera launched a Workforce Recovery Initiative that allows the unemployed in some states and other countries, including Colombia and Singapore, to learn for free until the end of the year.

Online learning providers can offer relatively inexpensive upskilling options because they don’t have guidance counselors, classrooms and other features of brick-and-mortar schools. But there could be more of a role for employers to provide those support systems going forward. Dalporto, who calls the wave of automation during COVID-19 “our economic Pearl Harbor,” argues that the government should provide a tax credit of $2,500 per upskilled worker to companies that provide retraining. He also suggests that company severance packages include $1,500 in retraining credits.

Some employers are turning to Guild Education, which works with employers to subsidize upskilling. A program it launched in May lets companies pay a fee to have Guild assist laid-off workers in finding new jobs. Employers see this as a way to create loyalty among these former employees, says Rachel Carlson, the CEO of Guild. “The most thoughtful consumer companies say, Employee for now, customer for life,” she says.

With the economy 30 million jobs short of what it had before the pandemic, though, workers and employers may not see much use in training for jobs that may not be available for months or even years. And not every worker is interested in studying data science, cloud computing or artificial intelligence.

But those who have found a way to move from dying fields to in-demand jobs are likely to do better. A few years ago, Tristen Alexander was a call-center rep at a Georgia power company when he took a six-month online course to earn a Google IT Support Professional Certificate. A Google scholarship covered the cost for Alexander, who has no college degree and was supporting his wife and two kids on about $38,000 a year. Alexander credits his certificate with helping him win a promotion and says he now earns more than $70,000 annually. What’s more, the promotion has given him a sense of job security. “I just think there’s a great need for everyone to learn something technical,” he tells me.

Of course, Alexander knows that technology may significantly change his job in the next decade, so he’s already planning his next step. By 2021, he wants to master the skill of testing computer systems to spot vulnerabilities to hackers and gain a certificate in that practice, known as penetration testing. It will all but guarantee him a job, he says, working alongside the technology that’s changing the world.

–With reporting by Alejandro de la Garza and Julia Zorthian/New York

from Blogger https://ift.tt/2PtPJMD via IFTTT

0 notes

Text

Chuck vs Truffaut Industries Ch 9, Get What you Need

A/N: *peaks from around the protective barrier I've built* Oh, hey, you're back. No one really stormed the castle, so it appears we're all good. Chuck and Sarah have moved past what happened (it's me, you knew they would), we learned Stephen may not be at fault, and Mary sucks at time-management. (What if she'd left something on the stove when she left? Goodness gracious.) So Truffaut is up and running, but it seems to have very few employees. It's okay, I have ideas. Chuck is about one thing, family, and families are messy.

Today's music was released way back in 1969, but don't worry, you don't need an 8 track and you know the song. (You guys do know what an 8 track is…right…never mind.) This song by the Rolling Stones, You Can't Always Get What You Want sums up this entire story. Ch 9, Get What You Need…You can't always get what you want but if you try sometimes you find you get what you need…

Disclaimer: I don't own Chuck, I don't really like cherry red soda, but I love the Stones.

"They seriously started a band?" Chuck asked.

"Yeah, Jeffster, and Chuck, they are God awful," Morgan said. "Neither one can sing, and that keytaur….I mean I love the 80s but give me a break."

"How's Anna?" Chuck asked, thankful he was out of that place.

"Scary…hot….scary hot…but scary," Morgan said, thinking.

"Still wearing the nerd herd uniform the way she wants?"

"Oh, yeah," Morgan said, grinning and lost in thought. Chuck shook his head, and watched the video again. He wasn't sure what he was looking for, but he figured he ought to appear to give it a shot.

"Do you want me to take him back to the zoo?" Casey asked, coming into Chuck's office.

"Nice to see you too, John." Morgan said pleasantly. "Enjoying your new job as a secretary? You should be a bouncer or something, it more fits your skill set."

"You should be a garden gnome," the big man grumbled.

"Well, should I give you two some alone time, or do you just want to go out on a date?" Chuck said. Casey growled.

"I came in here to find out if anyone made any progress on the break-in," Casey replied.

"Well, I haven't and I don't know if Sarah has or not," Chuck said.

"Why don't you go ask her?" Casey asked. "We're missing something, no one is that good."

"I'm not asking her because she's talking to her mother," Chuck replied. "And, you're right, there is no sign of anything."

"Does she know you're out here with your boyfriend mixing your chocolate and peanut butter?" Casey asked.

"That does sound delicious," Morgan said. "What does that even mean though?" Chuck shrugged. "Casey, what type of sandwich would you want if you were stuck on a deserted island?" Casey turned and left. "He always does that." Morgan turned to Chuck. "I thought you were a partner in the company."

"I am, but those two started it, so I'm trying to stay out of their way," Chuck said. Morgan looked at him, and shook his head, disappointed.

"Charles Irving Bartowski," Morgan began. Chuck looked at Morgan in shock.

"Ellie?" he asked. Morgan waved his hand.

"Focus, Chuck," Morgan said, annoyed. "You are going to take in the profits of your position without doing any of the work." Chuck thought for a second.

"Okay, 1, I never thought of it like that, and now I feel bad, but 2, don't you do that at the Buy More?" Chuck asked.

"Chuck, it's the Buy More," Morgan replied as if that explained everything. Chuck nodded and got up to go talk to Sarah. "Go ahead, if you don't care, I'm going to watch this while you're gone." Chuck shrugged. "So what am I looking for?"

"Anything that will explain how they got in with no one realizing it until it was too late," Chuck said.

"Really?" Morgan asked. "Because it's pretty obvious." Chuck turned to him. Casey stuck his head around the corner.

"There is no way a bearded gnome can figure this out and I can't," Casey said.

"Bet me," Morgan countered.

"What's the stakes?" Casey asked.

"If I'm right, I get a job here, a place to live in Simi Valley, and a date," Morgan said.

"If you lose, you never come in here again," Casey said grinning.

"Deal," Morgan said.

"Deal," Casey said, reaching out his hand his eyes gleaming. They shook on it.

"Not to be a party pooper, but Casey, you don't have that authority," Chuck reminded him.

"Fine, let's go tell you girlfriend and throw out the gnome," Casey said, as happy as they've ever seen him.

"I really don't think he likes me," Morgan said.

"He didn't choke you this time," Chuck pointed out.

"There's that," Morgan said, brightening. They walked to the conference room, where Sarah waved them all in. Casey told Sarah the bet.

"Okay, if you can figure it out, I'll get you the job, but the housing-" she began, and then the screen popped on.

"Oh good, you're all here," Beckman said. Chuck didn't look happy. "Listen, Mr. Bartowski we can sort out our disagreements later, this is about the safety of your friend." Chuck nodded, Morgan looked concerned. "We are very concerned about Stephen contacting Mr. Grimes, and given what he did to Chuck and Sarah, we fear he might escalate things."

"General, do you mean physical harm, because my father wouldn't do that," Chuck said.

"Chuck," Beckman said as gently as she could. "After talking to your mother about what we think is going on, I need to ask you a question, and you to answer seriously, did you ever think your father would keep you away from your daughter?" The look on Chuck's face gave the answer. "I'm sorry, I know that sounds harsh, but he seems to be escalating. I want Mr. Grimes there with you, and I'm thinking about assigning Casey as his permanent security."

"General," Casey began. "Hold on just a minute, I'm already watching four people." Beckman nodded. "Is this guy really worth it?"

"I figure out what happened at the break in, and you haven't," Morgan retorted. Beckman leaned forward.

"Really," Beckman said. "I'd love to hear what you think, because we need this solved quickly to find the information taken." Morgan looked at Chuck.

"He and Casey kinda made a bet, General, but Casey promised things he couldn't deliver on," Chuck explained. Beckman frowned.

"Whatever the major said, I will honor," Beckman replied.

"The problem is, General, if Morgan is wrong he's not allowed to come back in the doors here," Chuck said.

"That's not happening, I need Mr. Grimes there, and not in Burbank," Beckman said. Casey groaned and Morgan rubbed his hands together.

"Great, I'm playing with house money," Morgan said. "The fight was staged." Beckman lifted an eyebrow. "The fight between the security guy and the robber, watch it again, it's staged. I know my Kung-Fu movies." Casey stared at Morgan. Sarah, grinning played back the video and Morgan pointed everything out.

"Well done, Mr. Grimes!" Beckman said. "We'll have the security guard picked up, and find out where his accomplices are. Now, what were your terms?"

"A place to live here in Simi Valley," he began.

"Done, the Major has a duplex, Morgan can move into the other side," Beckman said. Casey groaned.

"A job here," Morgan said.

"Doing what?" Sarah asked. "I'm not saying no, just what would you do?"

"We can't play video games like we do every night, Buddy," Chuck said.

"Wait," Sarah said. "You are who Chuck plays?" Morgan nodded. "General, Morgan is an amazing strategist."

"I have my moments," Morgan said proudly. "And I find the best sub-$10 cuisine in Burbank, I'm sure I can do the same here."

"Done," Beckman said. "Mrs. Walker, you and I can work out his compensation." Sarah nodded.

"I also want a date," Morgan said. Sarah's eyebrows shot up. "Not with any of you," he quickly added.

"Looks like you missed your chance, Bartowski," Casey muttered.

"You sound a little jealous," Chuck retorted. Sarah stood there, thinking.

"I have an idea," she said. Morgan smiled.

"I trust you," Morgan said. Sarah smiled at him. "Now, I'm going to go get my stuff to move in, if that's alright."

"Sarah, attach a tracking watch to him, and show him how to use it," Beckman said. "I don't like sending you alone, but I just don't have the resources right now." She scanned some paperwork and looked up, catching Sarah's eye. "There is a government agent in California though…let me work on something. Good job team!" And, with that, she cut off.

"Team?" Chuck asked. Sarah shrugged.

"She is one of our biggest customers as far as money is concerned," Sarah said. Chuck looked a little upset.

"And I nearly blew it yesterday," he said. Sarah shook her head.

"I don't care if you did," Sarah said.

"Chuck, you're family," Emma said. Chuck gave them a sad smile. They heard Molly on the baby monitor.

"I'll go, let you all do some real work," and with that Chuck was gone. Sarah knew this whole mess was still bothering him. It wasn't going to affect them anymore, but it was still bothering him.

}o{

Morgan had loaded the Nerd Herder, he had to figure out how to get it back to Burbank before he was reported for stealing it, and thought he would bring some sizzilin' shrimp to his new co-workers. He was walking to his car when he heard a commotion. He turned and a beautiful red-headed woman was running toward him, being chased by men. Morgan quickly opened the door, and started the car.

"Get in," he yelled, she seemed to take a second to weigh her choices, but she dove in the car and he took off. "Morgan Grimes," he said.

"Huh?" the woman answered.

"It's my name, Morgan Grimes," he replied.

"Oh, Carina," she said. "Thanks for the save."

"Where to?" Morgan asked. "And what did you do, stiff them the tip on some egg rolls?" Carina just stared at him.

"Sure, let's go with that," she said. "Unless you know anyone with access to the federal government agency, I'm not sure."

"I do, but it's in Simi Valley," he answered. Carina just stared at him.

"Blonde lady, blue eyes, tall?" Carina asked.

"Yeah, Sarah!" he exclaimed. "You know her?"

"Probably," Carina said.

"Oh, you may know her as Jenny," Morgan said. Carina looked at him. "That's who she was when Chuck met her."

"Chuck? Chuck Babinski?" she asked. "Wait, so you're Martin?"

"No, I'm Morgan, and he's Chuck Bartowski," Morgan explained.

"Same thing," she said, as she sat back. "Let's go there."

"It's a bit of a drive," he said, and gave her a quick glance. "So, what type of sandwich would you want if you were on a deserted island?"

}o{

"Hey, what's wrong?" Sarah asked, watching Chuck hold Molly in his office. He was sitting in one the chairs facing the back of his monitors like he was a client.

"I feel a little useless," he said.

"Chuck, why?"

"Listen, I get it, I did something good with Verbanski, but what else am I good for?" he asked. "Morgan figured out things I couldn't, he even pointed out I wasn't doing my part as an owner."

"Well, he's right," Sarah said. Chuck looked at her, and she gave him, a "well, you said it" look. "Listen, I can't do a thing you did with those computer programs. You've turned this business into a profit machine, and take away our government contracts because of my contacts, you are the only reason we make money. We each have a specialty, but there's something else you have that the rest of us don't. You care. Chuck, you're a part of this, it's up to you to decide how much you want to be a part." Chuck sat there nodding.

"Sorry," Chuck began, but stopped.

"What?"

"No, it's just an excuse," Chuck said. "Starting now, I'm going to be a part, but if I do too much tell me to back off."

"If you were going to say your life's been flipped upside down, you'd be right, and I don't think that's as much as of an excuse but an adjustment," Sarah said, winking. "Now come on, we've got work to do, and I need you, as a part owner to look at some things. They walked up front as Morgan entered and Carina was behind him.

"Hey, Sarah, this is Carina and she needs some help," Morgan said.

"Carina is it?" Sarah said smiling. She walked up to Carina, studied her, grinned, and hugged her.

"Miller," Carina said, returning the hug. "I'm glad you got out."

"Walker," Sarah told her. "I'm glad I got out." The two broke the hug and Carina saw Chuck holding Molly.

"Wow, she's gotten big," Carina said. "Nice boy toy," she whispered.

"Chuck, this is Carina, an old friend," Sarah said. Chuck raised an eyebrow, but said, nothing, knowing he'd get he'd get the full story later.

"Wait, baby daddy, Chuck?" Carina asked.

"I really don't like that term," Chuck said. Sarah shrugged.

"It's not an untrue statement," she said.

"You keep being the sassy one," Chuck said grinning.

"You two are sickening," Carina said. Sarah stuck her tongue out at Carina. Carina shook her head. "You are absolutely domesticated, and you love it." Sarah nodded.

"Oh, what fresh hell is this," Casey growled.

"Miss me, John?" Carina asked. Casey growled and walked away.

"They know each other?" Chuck asked, the whole group following Carina following Casey.

"Long story, I'll tell you later," she said.

"Casey, seriously I need to check in," Carina said. Casey turned, gave her a look, grunted, and took her into the conference room along with everyone else. Beckman came on the screen.

"Agent Miller, thank God you okay," Beckman said. "Last we heard the Triad was on your trail.

"Wait, those were Triad?" Morgan said.

"Yeah, Marty, why did you think I jumped in your car with you?" Carina asked.

"The beard," Morgan admitted.

"It is an impressive beard, my friend," Chuck admitted. "What did you think was going on?

"I thought she had stiffed someone a tip," Morgan admitted. Chuck just blinked and shook his head. Sarah had her head buried in Chuck's arm laughing.

"Agent Miller," Beckman said, really enjoying what she was about to do. "The DEA has two choices with you so badly compromised right now. They can put you in the office and have you do nothing but paperwork-"

"I'll take the other, whatever it is," Carina said, cutting in. Beckman smiled.

"Or, you can move in with Mr. Grimes for both of your protection," Beckman said. Chuck tried so hard not to laugh. Sarah was crying from laughing so hard, and Casey was even chuckling.

"Uh, General, that's a bad idea, the Triad are looking for me," Carina said.

"Not in Simi Valley, and certainly not in Morgan Grime's half of a duplex," Beckman said. "Plus with the Major living right beside you, he can keep an eye out if something should happen. These are your choices Agent Miller. DEA desk, or temporary assignment to the DEA where you could sometimes, possibly do assignments." Carina looked at Morgan.

"General," Casey said. "It might be even better if you made Carina Mr. Grime's cover girl friend." Carina glared daggers at Casey.

"This is for Prague, isn't it?" she said. Casey just shrugged.

"That's not a bad idea," Beckman said. "Sarah, can you find something for Carina to do at Truffaut, you won't actually have to pay her."

"She does have a certain, skill set," Casey said, laughing.

"Casey, that's a bit low," Chuck said. Sarah beamed at Chuck.

"Agent Miller, regardless of the crude was it has been put, Major Casey is right," Beckman said. Carina sighed.

"How much cover goes into the cover?" Carina asked.

"Not as much as you usually give," Beckman responded. Sarah's eyebrows about shot up off of her head. "But as usual, what you and Mr. Grimes decide to do, that's your business.

"Okay, I'll date Marty," Carina said.

"Good," Beckman replied. "Mr. Bartowski, Mrs. Walker, would you be so kind as to help them get into their role by going on a double date tonight. I do believe we owe Mr. Grimes a date."

}o{

As Chuck and Sarah got to the restaurant, Sarah got a text. She read it, looked at Chuck, and then pulled him in for a time-stopping kiss.

"What's was that for, national emergency?" he asked, when his brain rebooted.

"No, that kiss was I love you, thank you for being my boyfriend, baby daddy," she smiled as Chuck gave her a look. "And, to hope you know whatever she says in there tonight, I'm not that person in anymore." Chuck smiled at her.

"Sarah, I've been told by enough people what kind of changes you went through after you met me, I don't care about before that," Chuck said, sincerely. "I love you." Sarah smiled, but she looked worried.

"How about in a few days we either have Ellie over, or go to her house and have her tell you all the embarrassing stories in the world about me," Chuck said. Sarah grinned, but there were tears.

"Chuck, dad was in prison, and I had to do things for the CIA, any means necessary," she said. Chuck looked upset. "See, this is why I don't talk about the past much."

"I'm going to kill Graham, to make you use yourself like that-" Chuck was angry, but Sarah laid a hand on his arm, to try to calm him and cut him off.

"Listen, I had to stop people, by killing them, not bang half the football team," she said, trying to make a joke. "Too soon?"

"You made a joke about that right after I met you, how would now be too soon?" Chuck asked, the anger abating. "Sarah, were they bad guys…or girls, I don't want to be sexist…should that be women instead of girls." Sarah rolled her eyes.

"Yes, Chuck, bad people," she said. "And some men I had to seduce, which meant lead them on, let them have what they thought would be a good time, and then…" Chuck nodded.

"You did it to save innocents, at the cost of your own innocence," he said. Sarah stared at him.

"Damn," she whispered.

"What, did I say something wrong?" he asked, very confused.

"Just when I think I can't love you more, you say something like that. Something so understanding, and exactly what I needed to hear," she said. "We need to stop by Large Mart on the way home." With that, she swallowed, steadied herself, and began to lead him inside.

"Why would we need…Oh," he said, understanding hitting him. "We have a full box." She just gave him a look, and it finally dawned on him. "Oh, boy."

}o{

Sarah was humming happily, working on business expenses when Carian barged in.

"Is something wrong with me?" she asked. Sarah gave her the once over.

"Nothing physically, mentally we don't have that kind of time," Sarah answered. Carina was still upset and not taking the bait. Sarah sat back, arms crossed, curious. "Sit," she said, nodding toward the chair across from her. Carina hesitated, shut the door, drawing an eyebrow raise from Sarah, and sit down.

"He slept on the couch last night," Carina said. Sarah unfolded her arms, and leaned forward on her desk. "He was an absolute gentleman."

"Those guys exist you know," Sarah said.

"I need to go back to the DEA," Carina said. "I'll just stay on the desk, I can't do this, Sarah," she said.

"Who will protect him?" Sarah asked. Carina looked at her. "You are shook to your core," she said. "Morgan Grimes rescued you without wanting a thing, he took you to dinner, treated you like a princess, refused to take advantage of the situation, and you, Carina, are feeling things you don't know how to handle."

"Blondie, you don't understand…" Carina began lost for words. Sarah just smiled.

"Oh, I don't?" she asked, picking up a picture of Chuck and Molly. Carina looked at it, turning pale. "You are scared to death. You enjoy your life, you really do, and that's great, you should, but you've got the taste of something else, and while you don't want to want it, a small piece of you, is attracted to it in a way you've never felt. So, Carina Miller, are you gonna face it, or run, and leave 'Marty' all alone."

"I called him Morgan last night, and you know what he said?" Carina asked. Sarah shook her head. "He looked kinda disappointed, and I asked why, and he told me, 'Me being Marty, that's kinda our thing,' and he walked off."

"Now tell me how it ends," Sarah said. Carina blushed and Sarah nearly fell out of her seat.

"I said, 'I'm sorry Marty, it just slipped, you know being all these different places, it won't happen again.'" Carina couldn't even look Sarah in the eye.

"Is it the beard?" Sarah asked, grinning.

"No!" Carina said forcefully. She was quiet for a second. "I do like it though." A knock on the door paused their conversation, they saw it was Chuck and Sarah signaled him to come in.

"Sorry to intrude, but we have a potential client," Chuck said. "They have a potential infiltration they'd like us to do for them to check their security," he said, wincing.

"What?" Sarah asked, worried.

"Morgan, heard the whole thing, saw the blueprints, and thinks he knows a way in, but it would take someone with a certain skill set," he said.

"Me," Carina said, grinning. Chuck nodded.

"Okay, I'll talk to them," Sarah said. "If we agree, you and Casey do the infiltration and take Morgan on coms with you since he knows the plan." Carina nodded, got up, and headed outside.

"Did it work?" Chuck asked grinning.

"Did what work?" she asked, amused. What were those two up to?

"Operation RESPECT," Chuck said, the smile covering his face. "Reject Each Sexual PredicamEnt Carina Tries."

"Are you allowed to use two letters in the same word?" Sarah asked, laughing. Chuck shrugged.

"It's all Morgan's idea, I'm just helping him," Chuck said.

"You do know Carina is…" Sarah trailed off.

"A human being that deserves to be loved just like anyone else?" Chuck offered. Sarah smiled, got up, walked out her door, and as Chuck turned to join her, she swatted his backside. "Gotta stop by Large Mart tonight."

"AGAIN?"

}o{

"Did it work?" Morgan asked, sticking his head into Chuck's office. Chuck shook his head, smiling.

"They were talking about something pretty seriously, when I walked in, Buddy," Chuck said. "They want to take you on coms." Morgan fist pumped upon hearing that. "Are you ready for this?"

"I'll just take ANOTHER cold shower," Morgan said. Chuck gave him a look. "Dude, do you know the look she gave me, when I told her no. She gave me puppy dog eyes, and then came and sat on the couch with me."

"Morgan," Chuck said, warning him.

"Then, she stretched a leg over me," he paused, lost in thought. "They are so long," he said, in awe.

"Morgan," Chuck said, his voice getting louder.

"Then she straddle me, and whispered into my ear about how she'd make me think my name actually was Marty," Morgan said, his eyes far away.

"MORGAN!" Chuck yelled bringing Morgan back to Earth.

"Sorry," Morgan said. "There's been a lot of cold showers the past 24 hours dude, I think part of my brain is frozen." Chuck nodded.

"I understand," Chuck said.

"I get now why you wanted Jenny back so much," Morgan said, his eyes glazing over again. Chuck put his hand over his face. He picked up his phone and sent a text. A few minutes later, Casey came in, with a bucket of water, and poured it over Morgan's head.

"AHHH!" he yelled. Casey grunted at Chuck, nodded and walked off. "Thanks, Buddy." Morgan said, and headed out of his office. Sarah stuck her head in, a confused look on her face.

"Thinking about Carina?" she asked. Chuck nodded. "What do you say you and I take our girl to lunch?"

"That's the best idea I've heard today," Chuck said, grinning.

A/N: Next time, dinner with Ellie, bring your ear plugs…You just might find, you get what you need… Take care, see you soon

DC

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Interview with Jenni Desmond

Jenni very kindly agreed to let us interview her and answered questions about how she started out as an illustrator, her work process, her most well known books, how commissions work and other general arty things that we were interested in finding out. With her in depth answers she really helped to inform me about the children’s book and illustration industries which I'm sure will help me in developing my own career.

You do a lot of workshops with primary schools. What do you find interesting about working with children? As my books are for children it’s important to engage with my audience! Sometimes they say funny things that make me laugh. When they are enthusiastic about the book or about meeting me and I feel I can inspire them, they remind me why I am doing my job. I would have loved to have had a visiting author when I was little and I think I would have been very inspired by one so I try to remember that. (School trips also pay well!)

For ‘The First Slodge’ you collaborated with Jeanne Willis, as you have done on a few other books. How was it to work with her? Is it similar to editorial illustration? Do you have any influence over the narrative being written? I have no influence on the worded narrative, although I do try to 'write' a lot of extra information into the book with images. I have no engagement with the author. We met on email only a few months ago in fact and I've never met her in person. She seems lovely though. Everything is done through the publisher. When I've done the roughs etc the publisher sends the work to her for the okay.

You’ve won both the 2015 Best Emerging Talent (illustrator) at the Junior Design Awards and the 2016 New York Times Best Illustrated Children’s Book. How did winning each of these awards effect your reputation as an illustrator? Did you receive any commissions as a result? I'm sure it does effect things. It's always hard to tell how people found me etc but in the last year I have definitely become more well known and my job offers have definitely increased!

What is the inspiration for your drawings? Do you use reference images? Do you use your own handwriting for your fonts? I use my own handwriting. I use reference images at the beginning when I am researching an animal character to understand what shape it is. But then I just work from my head so I can insert the character without worrying about the shapes. Inspiration mostly from my personal life and relationships.

Last year, you were awarded the Maurice Sendak Fellowship. How was it? What was it like working alongside fellow illustrators handpicked for this award? WONDERFUL, and we were treated so so well! The farm we stayed at was gorgeous and we had our own houses and studios and lots of engagement with sendak's original artwork and stories about him. The illustrators were lovely and very interesting people. It was nice to have the time to work in my sketchbook on my own stuff, I don't have time to do that these days- drawing is now work! Which is a good thing. Even though it’s a passion, it’s no longer a hobby.

What motivated you to go back and study the Masters in Children’s Book Illustration? What sort of things did you learn? Would you recommend it to anyone wanting to become an illustrator? I didn't do a degree in illustration so felt I needed some training. It was very useful to learn the format of childrens books, learn about illustrators, be exposed to interesting ways of creating books, meet great people, improve my work.

How did you come up with the ideas for your non-fiction books? (The Blue Whale, The Polar Bear…) I was just looking around the internet one day and found some facts about blue whales. I scribbled them down quickly with some sketches and then forgot about them until I showed the publisher, quite absent mindedly really, and she had the vision to turn it into a 4 book series. You never know what nugget of an idea could spark into something, so it’s good to keep sketchbooks and things.

For The Blue Whale, did you adapt an illustration to fit the cover, or did you design it specifically as the cover? I had a vision of what the cover looked like from the start, it was one of the first sketches I did. In the end it’s also the same image as one of the spreads. But I always knew that’s what the cover would look like. (though the boat was a fishing boat at the beginning.)

How have you worked out a balance between producing art and having down time? I used to go out to the pub lots and fill my evenings, now I mostly just work and then go home to chill. I don't work at home. Ever. Baths, cooking, watching films and hanging out with my partner occupy a lot of my down time. I now go swimming every lunchtime which is good for the mind as well as the body.

Of the work that you produce, would you say that picture books are your favourite? Yes. I love that they have a use and are not just images, they are characters, stories, things to hopefully inspire children, and they are also objects. I do love books so it’s an honour to make them.

How do you go about promoting your work and exhibitions? Gah... social media? but I am not very good at it. Mostly my agent does that stuff.

How did you come to be represented by your agency? Do they decide which work you should do? How do their fees effect your commission prices? I was represented by an agency called Bright a few years ago, they picked me up at my grad show. I then moved to Penny Holroyde after being recommended her. It’s important to have the right agent, who you trust, it’s almost like having an extra parent or something, who always has your back and is with you the whole way. She advises me on what I should do. Her main job is to negotiate contracts which are a mine field. She will normally bump the fee up a bit which will normally just about cover her fees (15% plus vat). For me having an agent is essential and wonderful to let me just get on with focussing on my work. You can get a bit screwed over when starting out so do be careful with contracts, and use AOI for any advice on them.

Has it been difficult finding work as a freelance artist? Sometimes. It gets easier the more well known you get. And the better you get! It’s important to keep working, keep improving, keep trying. It’s a pretty tough career to get in to. I sell things on etsy, which can be a good source of income. In general, the pay as an illustrator or picture book maker is a bit crap.

In an interview with playingbythebook.com you said ‘I use music as a tool. I find that it transports me to my imagination.’ How so? I dance around in my head and then draw the characters dancing around too, which gives them lots of movement and life.

What inspired the move to London? Did you need more space than the studio you had in Brighton? I wanted to be in the thick of it I think, and most of my friends were here. I'd gone to uni at sussex so had been in brighton for a while and I had run out of enthusiasm for it a little. The space I can get in Hackney is def smaller than Brighton - hackney studio spaces start at about £180 for a desk so it’s not cheap! I had a nice big space in south London (whirled art studios) when I first moved here and it was dirt cheap, I loved that place. Sadly it’s too far away now. But Hackney Downs is super great.

What has it been like to work with Enchanted Lion Books? What happens under a multiple book series deal like you have with them? Wonderful, it’s a small publisher, pretty much a one woman band, and she is incredibly talented and bright and creative and she pushes me hard with her expectations and perfectionist ways. She's fantastic. A multiple book deal basically just means that once I've finished one then it’s on to the next. It’s nice to have the security of knowing you've got more work. The contract will be the same financially across all four books.