#i feel like trans pirates is a concept we don’t talk about enough

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

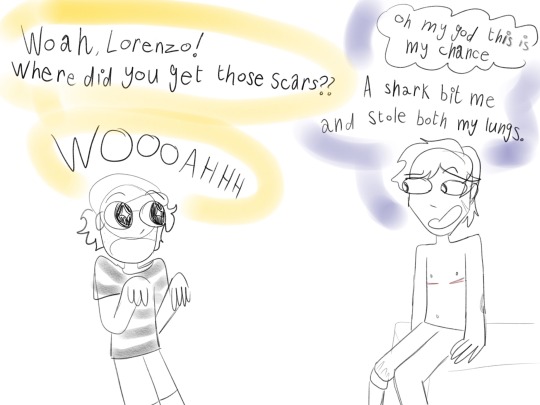

lying to children is never okay. unless the lie is really funny and cool

#felt like I had to draw something and now I’m really happy I finished this in one sitting :)#joeys doodles#my ocs#pirates#digital art#sunny#lorenzo#trans#trans meme#trans comic#trans pirates#i feel like trans pirates is a concept we don’t talk about enough#transmasc#sorry for the mountain of tags#trans man

45 notes

·

View notes

Note

Could please talk about why you go into the lesbian master doc bothers you? If it's not too much trouble of course if it is tho feel free to disregard this message haha

lots of reasons but i’ll try to be somewhat succinct because i could write a very long essay.

keep in mind i’m not doing an acedemic or moral critique of the authors of the thing because i don’t actually know too much about them specifically, but i have read the full document and will critique its methods and content.

so everyone has their personals on it, but there’s a lot of things that stand out to me personally.

comp het is a term that was maybe not directly coined by adrienne rich but it was absolutely canonized the way we use it now by this specific essay by her. the lesbian master doc uses the concepts in this essay as a basis for their assertions. adrienne rich was a violent terf. she was an incredibly intense supporter of “The Transsexual Empire” book (a book which coined many of the horrible arguments used against specifically trans women existing as women) and author janice g raymond. this does in fact have implications in her essay about comp het. her essay included attraction to trans women compulsive heterosexuality and this theory has yet to be properly updated to my eyes to account for the inherent transmisogyny that helped invent it.

it still has transmisogynystic features as a theory, and consequently, so does the damn lesbian doc because it uses the theory of compulsive heterosexuality, unedited, as a basis. its very framework is pretty problematic.

such as implying that *liking to peg men* might be reason to believe you’re a lesbian, which has all sorts of interesting sexual connotations that i don’t agree with. i’m hoping if the damn thing is updated since i last saw it they walked that back really hard.

okay let’s put all the above aside, even then it’s not great.

it’s confused people more than helped in my opinion. it perpetuates stereotypes of experience (and stereotypes will sometimes be true for people is why people relate!) that just aren’t the full breadth of who people are as lesbians, you know?

it’s a very fucking bleakly small look at what being a lesbian feels like and means.

lesbianhood has a long, rich history. a long, rich literature. our feelings and what makes us ourselves and what shows our compulsions cannot be condensed as surely or succinctly. i want people to read real lesbian books! i want people to read trans lesbian books! butch lesbian books! lesbian books!!!!! i have entire bookshelves of them, they exist and they’re beautiful and free at your public library or on pirating websites if you are in a bad situation.

these books are much more intense, affecting, and comprehensive of who we are without accidentally excluding people because you can’t exclude yourself quite as easily!

i, whenever i get my shit sorted lol, plan on doing my phd on butch lit by itself because there’s literally enough of it to just do that.

what does it say about a (only) thirty one page document that poorly explains a very complex concept (comp het) with no context of that transphobic and specifically transmisogynistic as fuck history and then includes “You get anxiety around men and feel more comfortable in settings with women” as a reason for lesbianhood. that’s ridiculous.

do you know why i don’t feel that? i’m not any less of a lesbian for it, but i’ve been assaulted by women before. what if you’re a lesbian but read this doc and don’t relate. now what? are you confused?

by all means if it helped you, personally, discover that you are a lesbian you are not a bad person. i’m glad it helped Someone

i absolutely and violently do not respect the doc itself, though i completely understand why the authors made it

here’s a link so it can be judged for itself so people don’t think i’m obfuscating shit

#if anyone wants to fight me about this don’t#i have more books on being a lesbian than you and i don’t want to fight about this i’m very sick lol#anonymous#i should say gathering bones has more books on being a lesbian than me but they’re the only one lol#i’m gonna keep circling back in my head to this because i half want to add more but this is already too long

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

On O-Kiku

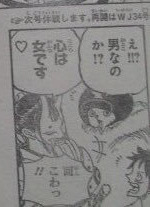

Kiku should be considered a transwoman and adressed accordingly. "If it is not possible to ask a transgender person which pronoun they use, use the pronoun that is consistent with the person's appearance and gender expression or use the singular they." - Gay and Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation https://www.glaad.org/reference/transgender So I’ve spent quite some time today and yesterday arguing about this topic, so I figured I’d collect some of it in this post. I won’t repeat every argument I’ve seen made, because there’s some really ridiculous ones out there. But if anyone wants to make another argument not included here, I’ll just argue against that too. “I’m a woman at heart” So, the original japanese says: "心は女です。♡", "Kokoro wa Onna desu.♡" It means something like “My heart is a woman” (“kokoro” can mean heart, mind, soul, feeling, etc...Either way, I think the intention is obvious) If you read a translation that had a “Yes, but...”, that is actually not in the japanese text, but added by the translators. So Kiku doesn’t even give the question of “Are you a man?” the benefit of confirmation or denial. She just says she’s a woman, and that’s all that matters.

Honestly, I think this alone should stand above anything else, but if you have a different opinion, the counter arguments and confusion will be tackled below the cut:

Kiku uses a male pronoun! Okay, so bear with me, because this might be hard to understand if you’re not familiar with it. First of, if you refer to Kiku as “he” because she uses “sessha” ( 拙者 or せっしゃ) then I’m afraid you’re gonna have to refer to, for example, Big Mom as “he” too if you don't want to be a hypocrit, since Big Mom uses “ore” (俺). But, that’s not the case right? So: Pronouns aren’t necessarily gendered in japanese. Pronouns show your status in the setting or conversation. You can use a more humble pronoun like “watashi” when talking to your boss, but use a more tough one in privat, like “ore”. It’s like changing your clothes. A man doesn’t necessarily identify as a woman the moment he puts on a dress. This is why many of the instances that are usually translated as insults in the form of calling names in english, are usually just second person pronouns used to degrade the status of the other person. They didn’t even have gendered third person pronouns in japanese before they started translating western literature and had to make something up. Of course based on social norms there are pronouns that are considered “proper” for people to use based on their gender, but the pronoun itself isn’t gendered. Big Mom uses “ore” because she’s super tough, which is something not expected from women, so it’s not associated with them. So, “sessha” ( 拙者 or せっしゃ) is an archaic pronoun used by samurai. Historically samurai were expected to be men, so obviously there’s no pronoun commonly used by specifically female samurai. Kiku doesn’t use sessha to express her gender identity, she uses it to express her status as a samurai.

The Nine Red Scabbards are specifially male! Okay, so first off, in general, you will often encounter “man” being the default in japanese language. The word for siblings, “kyoudai” “兄弟” uses only the signs of big brother and little brother, despite it also being used to refer to sisters. Now specifically to the name: Those who don’t know, the japanese name for the “Nine Red Scabbards” is “赤鞘九人男” Akazaya ku-Nin Otoko, in which “男” otoko means man/men (Remember the joke with O-Toko?) Now I personally only see this as a narrative device to foreshadow O-Kiku hiding being a man or a transwoman until further confirmation (such as we got this chapter, 948), similarly to her name also being a reference hinting at it. But if you want to argue in-universe: The name isn’t necessarily chosen by the mebers itself? Zoro never called himself a Pirate Hunter, these titles are made up by the public. And in this very chapter we have an outsider calling O-Kiku a man. This random prisoner doesn’t decide Kiku’s gender, neither does the general public. Kiku is based on an Onnagata, so a man! What a character is based on doesn’t dictate what they are in the story. Usopp is partly a reference to Pinocchio, and we are not waiting on a reveal of him being a wooden puppet turned real boy now are we? For those who don’t know, Onnagata are male actors playing female roles in theatre. There’s also no way of determining whether or not no Onnagata ever was a transwoman. The concept and recognition is still pretty modern and history has shown to try to erase people from the LGBTQ+ community from the records.

There is no concept of Trans in Wano/One Piece / they don’t exist Now, I’m sorry, but this one is especially silly if you ask me. There being a concept of and them existing are different topics. If we’re talking about One Piece as a whole, the concept of transgender has come up before, specifically with Ivankov and the “Newkama”. Even if there is no understand of “transgender” in Wano (If you want to assume there isn’t, due to it being based on feudal Japan, which again look point above) that doesn’t mean there can’t be transgender people. They also don’t have a concept for devil fruits, but we can recognize a devil fruit user anyway. They also have no concept of “gun”, but we all know a gun when we see one. We, as the readers, can easily recognize Kiku as a transwoman, irregardless of whether or not the fictional society she is from has reached that level of understanding. I just want something more evidence. I genuinely don’t understand how it could be anymore clear. Like I said, you won’t be able to dictate Kiku’s gender by the pronouns used in the japanese original, because that is not how pronouns work in japanese. This is a japanese shonen manga, you cannot be any more obvious than literally saying “My heart is a woman”

Alright, so these are all the counter arguments I considered worth adressing. I know there is some confusion specifically because of people not knowing enough about japanese as a language itself.

279 notes

·

View notes

Note

My story is about pirates. The MC is a trans guy and the captain is a lesbian who is some sort of big sister/mother figure to him. It's quite violent. I was wondering if it could be problematic? I know it's problematic to show trans woman being overly violent in fiction but what about cis lesbians and straight trans guys? Also, do you know about real any queer pirates i could read about? And what did pirates think about homosexuality/transness?) How was it being queer in the pirate world?

A conversation that I had, that is relevant:

ME: [PARTNER], do you know anything about queer pirates?

PARTNER: I know that there were many, and they’d sometimes be like -

ME: Sea husbands kind of thing?

PARTNER: Yeah, and one would inherit from the other’s booty, and when it was divided up, they’d share their share of the booty.

ME: [mischievous grinning face]

PARTNER: [nodding] And they might share each other’s booty.

Disclaimer: This whole thing is going to largely focus on what is known as the Golden Age Of Piracy. I’m also not a historian, I just hardcore, love pirates with my heart and soul. This is going to be a long post.

So, this is super generalized, but pirates, and even sea-faring folks in general (see: - or sea, hahahahaha - the LGBT+ history of Brighton in the UK), have tended to have a much higher rate of LGBT+ folks and minoritized people in general, throughout history. As far as most research I’ve done goes. Being in a travelling situation and having the anonymity of being able to move around with chosen family generally has great appeal to folks whose existences are filled with oppression and a sense of not belongingness. This has also applied for racialized people, women in general, impoverished folks in general, a lot of different people who wanted to reclaim a place in the world that ostracized them.

Another fun fact, the use of the term “Friend of Dorothy” as a euphemism for gay folks was investigated by the US Navy. They misunderstood it as meaning that there actually was a woman named Dorothy who could be routed down and coerced into outing her “friends” to the military. Cruise ships and others have also used this phrase to covertly advertise that there were meetings for these folks. (Source: Wikipedia | “Friend of Dorothy”)

But to get to the pirates, specifically.

Most pirate ships largely had their own code that everyone on their ship had to agree to. Some had things like, “you’ll be marooned with one knife, and no food if you are caught not reporting loot to be divvied up by the crew fairly” and things like that. But generally, whoever ran the ship, the Captain, would get to pick the rules. And with the partial-democracy that comes with the idea of mutiny, and the more notable reliance on the labour of it all, in general, things were able to be slightly more consensus-based than the on-land governments.

There are numerous women who became pirates to take ownership of their lives in ways that weren’t permitted on-land. Anne Bonny and Mary Read are historical figures that might be worth looking into. The two of them shared lovers, sailed together, had intense care for one and other and with their dressing up in masculine-coded attire and the like, there’s a lot to go off of in assuming they may have been romantically involved with each other. If not, at least they had some iteration of what a lot of contemporary folks might find comparable to a QPR.

The concept of “sea husbands” was also called matelotage (or bunkmate) depending on your crew. It was kind of the buddy system, but gayer. With little need to consistently explain it to outsiders, folks at sea were freer to explore the different ways a relationship with another person can be, without so much worrying about how it looks to others at a passing glance. And as pirates, there’s less concern that you’ll get shit from the law for gay stuff Of All Things.

Buccaneer Alexander Exquemelin wrote: ‘It is the general and solemn custom amongst them all to seek out… a comrade or companion, whom we may call partner… with whom they join the whole stock of what they possess.’ (Source)

It was just normal. They also had a version of health insurance where someone was compensated if they ended up disabled from battle. The compensation of death of your partner also works into this.

As for transness, these kinds of things have had fickle definitions and historically, it’s hard to be able to pinpoint specific people as fitting cleanly into contemporary cultural definitions of transness, because frankly, the past had different culture to now. When it comes to writing canonically trans characters in contexts where the language might have been different, it’s important to focus on making sure that a trans reader can identify the personal connection with that character’s experiences and feelings, just as much as it is to use language to name folks as trans.

Representation can go deeper than surface terminology and the like, and in cases where the terminology doesn’t necessarily match, it has to. Language like, “I never really felt like a [assigned gender] - I see myself more like [desciption of actual gender identity or name for it].” - is as good as just saying the character is trans in my opinion.

Depending on where the character is from, they also may have just outright had a word in their language for their identity.

Gender presentation was significantly freer with pirates than it was for folks on land. Things like earrings, frilled sleeves, varied hair length and similar, were not uncommon, although the gendered coding associated with these aspects of appearance had different implications than they do now. Gold earrings on seafarers were there to fund a proper burial if someone’s body washed ashore. Gendered clothing was also coded in more binary ways on land. Folks who wanted to be coded as men could do so by wearing pants and folks who wanted to be coded as women could do so with skirts and dresses. (Tangential but fun fact yet again: dressing in those big poofy skirts usually included massive pockets. They were generally not physically attached to the skirts, but if you wore it all properly you would easily be able to reach into them.)

Pirates and other seafarers also had clothing referred to as ‘slops’ for cleaning (if they were of the rank that cleaned anyway) which were pretty wide-legged pants that could almost pass for a skirt.

Material that pirates used for clothing was largely what they stole, but it was cut and sewn into the same shapes a lot of other seafarers wore. At the time, it was largely illegal (under English rules anyway) for people who weren’t the bourgeoisie to wear anything made with nice fabric. Rich people saw this as deceitful, and these laws enabled richer people to not mingle on an equal level with those of a lower socioeconomic status.

As pirates, if you’re already shunning the law, may as well wear full calico suits. (Like Calico Jack Rackham.)

There’s more info on pirate and privateer clothing here. (The link is to a free book in HTML format, complete with illustrations and talk of materials, and how the clothes worn at sea varied from clothes they wore when they came into shore and towns.)

I could write a book on this and still not have covered enough. But the gist is that pirates were a big counterculture of outsiders living their lives. LGBT+ people and racialized people got thrown into the mix (and jumped right in) and experienced much more liberated lives than they might otherwise. That isn’t to say they were flawlessly inclusive - there still definitely were a lot of things people thought of in congruence with colonial beliefs. There was racism and homophobia - but it looked a lot different, and was a lot lighter than you’d think. And there were some ships which banned women, but mainly I think that was because they typically didn’t have the background to hold their ground on the ships, and were considered more of a plus one to certain crew members (who brought them - the rules were specifically about bringing them onto the ship rather than them being there of their own accord) than part of the crew. Sometimes women were part of the crew.

Notably, Anne Bonny and Mary Read were in a polyamorous triad with Calico Jack Rackham. (I think a cis + het historian might argue about this but that would seem like denial to me tbh. There is much, MUCH more evidence pointing in this direction than against it, and it would be extraordinarily hard to argue otherwise.) I would definitely do some research on them!

I also recommend this book (link is the free text on WikiSource), A General History of the Robberies and Murders of the most notorious Pyrates. It is perhaps the most famous contemporary record of the lives of a number of pirates from the time, including Anne Bonny and Mary Read.

As for the sensitivity aspect of this ask, I’d say that what you are describing is completely fine. As long as the violence isn’t used to dehumanize or completely demonize, I would even say that I don’t have any warnings for you about it, or precautions to advise on.

Thank you for this opportunity to infodump about LGBT+ pirates. I hope this is not overwhelming, but I’m also happy to parse out segments of this better upon request. (Our ask will be open eventually, I promise.)

- mod nat

#Anonymous#mod nat#pirates#pirate history#history#golden age of piracy#piracy#mary read#anne bonny#queer pirates#lgbt pirates#a general history of pyrates#writeblr#matelotage#friend of dorothy#brighton#sea husbands#lgbt history#lgbt+ history#queer history#calico jack

424 notes

·

View notes

Photo

AUTONOMOUS BY ANNALEE NEWITZ

BY: NIALL HARRISON ISSUE: 11 DECEMBER 2017

1.

Medicine, medical research, and healthcare systems have always felt to me a little under-explored by SF. Every so often there's a small-press anthology, or some think tank-y futurism—such as this year's Writing the Future competition, organised by Kaleidoscope Health & Care—and on screen no starship is complete without its sickbay and doctor. But when it comes to more substantial SF, and in particular novels, the pickings seem slim. The two recent-ish examples that come to mind are Project Itoh's Harmony (2008, trans. Alexander O. Smith 2010), and Juli Zeh's The Method (2009, trans. Sally-Ann Spencer 2012): both are classically dystopian narratives that dramatise the totalitarian potential of excessive care. Beyond that, you have to look for more generally biotech-oriented stories that incorporate elements of healthcare politics, such as Stephanie Saulter's (r)egeneration series (2013-2015), or mainstream-published work that shades into the speculative, such as Jillian Weise's The Colony (2010) or Hanya Yanagihara's The People in the Trees (2013). The gap seems especially glaring when it comes to American genre SF, given the political prominence and immanently-dystopian quality of the American healthcare system, and its knock-on effects for global healthcare: to paraphrase William Gibson, the drugs are here, they're just not evenly distributed.

So Annalee Newitz's first novel, Autonomous, is welcome for building its narrative around the practicalities and morality of access to effective drugs, even if some of its choices are a little more confusing than you might hope. But we'll come to that. Setup first: towards the end of the present century, the global Collapse that looms in most of today's near futures leads to a realignment of the international order, away from nation-states and towards “economic coalitions”—of which the big players seem to be the Free Trade Zone that covers most of North America, the Asian Union, the African Federation, and the Eurozone—that represent near-total capitalist capture of governmental and public services. As a result, patent terms for new medicines have been extended to longer than a normal human lifespan; regulatory oversight of the clinical development process has been weakened nearly out of existence; drugs that enhance health and cognition are common and required for many jobs; and the pay-for-treatment US insurance model appears to have been extended to basically the entire world, leading to cascading generational inequality:

Only people with money could benefit from new medicine. Therefore, only the haves could remain physically healthy, while the have-nots couldn’t keep their minds sharp enough to work the good jobs, and didn’t generally live beyond a hundred. Plus, the cycle was passed down unfairly through families. The people who couldn’t afford patented meds were likely to have sickly, short-lived children who became indentured and never got out. (p. 55)

Enter Jack Chen, patent pirate. From a family of farmers, she moved into synthetic biology research, and then into open medicine activism, first as part of a group known as The Bilious Pills, then later and for decades as a solo artist. In July of 2144, we find her in the middle of the Arctic Ocean, charging up the batteries of her submarine and worrying over news stories about a bad batch of black-market pharma that might be her fault. In an attempt to raise funds to subsidise her “real work” making medically urgent antiviral and gene therapies freely available, Jack reverse-engineered and sold Zacuity, the hot new “productivity pill” made by Zaxy, which was “didn't just boost your concentration [but] made you enjoy work” (p. 14). Now there are stories in her feed about people with obsessive task addiction, starting with a student whose “brain showed a perfect addiction pattern [...] like she'd been addicted to homework for years” (p. 11). Before too long, Jack is on the run, attempting to find a cure for the people she's inadvertently hurt, while being pursued (in alternating chapters) by agents of the International Property Coalition.

Newitz's future, while perhaps not quite matching the likes of Lauren Beukes or Ian McDonald for sentence-level stylistic verve, is rich, varied, and consistently interesting; it's fun to roam from the Arctic to Casablanca to Vegas and on. But every now and then something doesn't quite ring true. The mildest of my eyebrow-raises were down to inconsistencies or ambiguities in terminology. If you tell me a drug is in “beta” (p. 29), I will assume a move-fast-and-break-things culture has replaced more rigorous medical research, unless and until you later start talking about phase 1 clinical trials: those two linguistic paradigms don't fit neatly together. If you refer to “cloned Zacuity” (p. 13), I will assume it is produced by a process in which cloning could plausibly be relevant; so it's probably a biologic, perhaps a cell therapy of some kind; but if you then talk about “isolat[ing] each part of the drug” and “narrow[ing] the questionable parts down to four molecules” (pp. 28-9) I will get thoroughly confused, since not only does that not sound like a cell therapy or biologic, it doesn't even sound like Zacuity is a single drug, but rather a combination of small-molecule treatments.

Above this, however, sit some practical and conceptual concerns. I can accept that the novel's characters believe that subversion of intellectual property law is the most practical solution to their crisis because they are living under total capitalism; but it is odd that nobody even laments the impossibility of a system that would centralise and pool healthcare costs. Socialism seems to have been thoroughly erased in the present, in memory, and in possibility. And I can accept that “Zaxy didn't make data from their clinical trials available”, but the corollary, “so there was no way to find out about possible side effects” (p. 14) seems a little dubious in what is evidently still a networked world easily capable of crowdsourcing that information. Then there's the underlying business model itself. It seems that the have-nots massively outnumber the haves, and while pharmaceutical companies are not perfectly rational economic agents, and have been known to push the limits of appropriate pricing for access to treatment, at a certain point charging x to a market of y patients becomes less profitable than charging a fraction of x to a multiple of y. Everything we learn about the world of Autonomous suggests that Zaxy and its competitors deliberately keep themselves on the wrong side of that equation. It's only Jack and her friends attempting to fill the market hole, and it's not clear why.

Why does such pedantry matter? Perhaps it doesn't. But Zacuity is presented to us as symptomatic of a system, a synecdoche for lost autonomy, the reduction of human lives to biological machinery. It's everything Jack has dedicated her life to fighting against. And for that fight to really matter, the symptom and the system need to feel crushingly inescapable; and they don't always.

2.

Or is there another way in? Autonomous explores its core theme on more than one front. It is a novel about seeking freedom in an owned world, and although the owners in the background don't always quite feel solid, their property is memorably thorny. Two pairings stand out in particular. Travelling with Jack is Threezed (3-Z, two syllables), a young indentured man she inadvertently rescues from his owner; pursuing them are two IPC agents, an enfranchised man named Eliasz, and an indentured artificial intelligence, Paladin.

Indenture is, for the avoidance of doubt, slavery, but a version grown from the worst of contemporary employment practices and a perversion of the concept of equality. It took root, we are told, in the mid-twenty-first century, with the arrival of the first true artificial intelligences: “companies could offset the cost of building robots by retaining ownership for up to ten years” (p. 224). (The parallel to non-sentient innovations such as pharmaceuticals is hard to miss.)

But when bots were granted human rights, that didn't come with their immediate freedom; instead, a new human right was enshrined, namely the “right” of indenture. “After all, if human-equivalent beings could be indentured, why not humans themselves?” (p. 224). This global endorsement of slavery as the ultimate choice of a good capitalist subject means that in 2144 it has expanded from what we know and become an order of magnitude more extensive than at any previous point human history. Its supposed limits are fig-leaves: even if birth-indenture of humans remains technically outlawed in most of the economic coalitions, many turn a blind eye, and in any case, child indenture is fine. Such was the fate of Threezed, as Jack sees it:

Families with nothing would sometimes sell their toddlers to indenture schools, where managers trained them to be submissive just like they were programming a bot. At least bots could earn their way out of ownership after a while, be upgraded, and go fully autonomous. Humans might earn their way out, but there was no autonomy key that could undo a childhood like that. (p. 31)

The other characters—and for most of the novel Threezed is seen only through the eyes of others—know this story intellectually, but for various reasons have a hard time internalising what it means. After Jack rescues him, Threezed, “his eyes wide with feigned innocence” (p. 52), offers to “repay” her; Jack wonders whether he is “trying to manipulate her” or whether “his indenture had trained him in this specific form of gratitude” (p. 52). She asks him if he is sure. “He bowed his head in an ambiguous gesture of obedience and consent” (p. 53): a haunting reaction. Their 'relationship' continues for some time, and Jack—an ostensibly pragmatic woman, for whom romance is “like any other biological process [...] the product of chemical and electrical signaling in her brain” (p. 57)—starts to convince herself Threezed's compliance is perhaps more than his programming. “She leaned over to kiss Threezed hard on the mouth. His reaction was not artful. It felt sloppy and real” (p. 88). That “real” lands hard, I think, imbued with a desperate desire for a simple story to be true, for Jack not to be exploiting vulnerability. But of course the power imbalance has distorted Jack's perceptions, as power imbalances inevitably will. Late in the novel we discover that Threezed keeps a blog of his experiences. It is a “prickly, grotesquely truthful story” (p. 243), and his take on Jack is simply that, “Every master loves to fuck a slave” (p. 253). What he doesn't add is the horror we have already seen: a master who wants to believe the slave loves to fuck them back.

While all this is happening, Paladin and Eliasz are becoming similarly entangled, but this time it's the master's view that is withheld. Paladin—newly activated and thus something of an innocent, albeit one equipped with alarmingly lethal military hardware, and with appropriate software installed to ensure an uncomplaining 20 years of indentured service—has an unexpectedly intimate moment with Eliasz fairly early on in the novel:

The bot stood at full height, and Eliasz rested his hands on the guns that jutted from Paladin's chest. Eliasz' right hand began to move slowly, getting to know the whole barrel by feel.

[...]

Shoot the entire roof off that house. Eliasz' lips were pressed into Paladin's carapace, moving slightly as he gave the vague order.

[...]

Paladin categorized the physiological changes in Eliasz' body and reloaded his guns. The bot decided to continue his human social communication test by not communicating. It didn't make sense to remind Eliasz that every single movement of his body, every rush of blood or spark of electricity, was completely transparent to Paladin. He would allow Eliasz to believe that he sensed nothing. (pp. 75-76)

This is entertaining—and a later scene in which Paladin allocates 20% of his processing power to run internet searches for confusing sexual terms while reserving the remaining 80% to concentrate on blowing shit up is outright funny—but it's also tragic. Every one of Paladin's actions is oriented towards meeting Eliasz' needs, even “his” acceptance of a particular pronoun. Bots, we are told more than once, do not have a sense of gender, and as a result it takes Paladin a while to understand how profoundly gender shapes the world for humans. When it becomes clear that Eliasz would be more comfortable with their relationship if he could think of Paladin as a woman, Paladin accommodates by accepting “she” instead of “he”, even recognising the potential impact of the change, even knowing that the choice may not be free: “Bug would no doubt say that there are no choices in slavery, nor true love in a mind running apps like gdoggie and masterluv. But they were all that Paladin had” (p. 236). More completely programmed than Threezed, Paladin's chosen truth shies away from the grotesque—even after she achieves autonomy.

Fortunately for Paladin, Eliasz treats her better than Jack treats Threezed—he asks permission, for one thing—and his feelings, when we are eventually given access to them, do appear to be—that word again—real. In contrast to Jack's mechanistic view of love, for Eliasz it is an unexamined but powerfully felt emotion, and when at a moment of crisis he has to choose between achieving a goal and saving Paladin, he thinks: “He had a choice. Or maybe he didn't” (p. 285). And like that we are reminded that the novel's logic for “human indenture” is particularly malevolent because it extrapolates from an underlying truth: that even when nominally free citizens, humans are never perfectly autonomous and that that is in fact a good and necessary fact; that in a thousand different interactions we give up some of our freedom, for the sake of each other, for the sake of society. Is that grounds for a faint flicker of hope? In Newitz's dystopia it may be supremely difficult to define when and where “real” occurs, but if at least some voluntary abstentions of autonomy remain possible, some of the time, then neither humans nor bots have been reduced to perfect commodities yet. So the fight does still matter. I think that, in the end, is what I choose to take from this unsettling, uneven novel.

@booksandghosts This reviewer is brilliant and the emphasis above (I bold/italicked the paragraph which matters to me) explains eloquently what I called “misgivings” while I read this book. I thought you would like to know. The review is -of course- somewhat spoilery, though not overly.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fantasy Lesbian Romance Novel Review Corner Extravaganza

so i’ve been reading a lot of lesbian fantasy romance novels! i always knew they were a thing that existed but upon just picking one up lately i haven’t been able to get enough so i’ve gone through quite a few. if you are a fan of swords, sorcery, and girls kissing girls, you might be interested in some of these too!

i’m going to give my thoughts about the ones i’ve read, and also mention how much homophobia exists in the book and how relevant it is to the plot, since i know people have varying feelings about that kind of thing.

i’ll put a cut here for kindness, so people don’t have to scroll forever. let’s begin!

Dragonoak by Sam Farren (Amazon: books 1, 2, 3) this is where it all began for me (thanks @d-medusa for the Sick Rec) and it’s pretty much the pinnacle of the genre for me thus far. it stands out hard because the vast majority of characters (and there are a lot of them) are gay women. there are several important non-binary characters, a handful of trans women, and best of all, no one ever comments on any of the above. ever. at all. it’s just a very gay setting and no one questions it, no one argues, it’s just How Shit Is. beyond that appeal, there’s a lot of fun fantasy shit: kingdoms and queens, dragons and necromancers, pirates and political intrigue, and it’s just a really great, fun time. i could not recommend these books any more highly than i already am. book 1 is admittedly a little slow/scattered, and if you can’t cling to the budding romance taking center stage, you might have some trouble with it; things pick up hard in the latter books, however. please give them a try! Homophobia Content: none. literally none. zero. no transphobia either.

When Women Were Warriors by Catherine Wilson (Amazon: books 1, 2, 3) these are not exactly fantasy as such, but they’re very much in the same vein. old-style, bands of female warriors, warring tribes, all that kind of thing, just without magic or anything supernatural. a touching if extremely straightforward tale of a girl become a warrior’s apprentice, falling in love with that warrior, undergoing trials, proving herself, et cetera. i might be making this sound sorta bland, and parts of it are, but there’s enough solid girl-love to carry you through. high points include a lot of allegorical stories inserted into the text here and there, low points include the most Hemingway-style writing i’ve seen outside of Hemingway himself. Homophobia Content: none at all; romances between women are expected and encouraged.

Lyremouth Chronicles by Jane Fletcher (Amazon: books 1, 2, 3, 4) oh boy, Jane Fletcher. i really dug this and her other series (detailed below), but man, once you’ve read one of her books, you’ve read them all; she has a very definitive style and she sticks to it hard. whether or not that style works for you may vary, but it hit with me really hard. these four books detail one specific couple, an exiled warrior and a budding sorcerer, and the adventures they have in the world. i ADORED these two characters, their consistently strong romance, and i was extremely sad to finally see their story end; both of them are extremely flawed, both have a great deal of depth, and they complement each other very well. i love the explorations of magic that permeate all four books, i love the world, just a great frickin time all around. Homophoba Content: ehhhh, there’s definitely some, and while it’s limited to the first portion of the first book, that section is fucking brutal if you don’t like homophobia in your books. once it’s past, though, the rest is totally free of that kind of thing.

Celaeno by Jane Fletcher (Amazon: books 1, 2, 3, 4, 5) not exactly fantasy, again, but not super far from it either. this was interesting initially because there are literally zero characters not only in the series, but in existence in the world, and if you’re shallow about your lesbian fantasy like i am, that is absolutely a good thing. unlike Lyremouth, however, which was pretty steady in quality all throughout, these vary hugely; i found myself less and less interested as the series progressed. each focuses on a different couple, and each have a very different level of stakes. in a world dominated by a religious order, some women become heretics and seek to eke out their own existence, even while hunted down by said religious order; an interesting enough backdrop, but some of the books (3 and 5, specifically) are just so low-stakes (solving an individual murder, talking a lot about sheep theft, respectively) that even the romance can’t carry them. book 2 is by far the best with the deepest characters, so read the first two and then stop there, imo. Homophobia Content: as mentioned, no men exist in this world, so homophobia as a concept simply doesn’t exist.

Adijan and her Genie by L-J Baker (Amazon; sadly, they don’t seem to carry an ebook version) super fun individual novel, in a fictionalized middle eastern setting; i can say pretty thoroughly that it didn’t go the way i expected it to whatsoever, in a good way, but i absolutely HATED the protagonist for constantly making the worst decisions possible over and over. an desperate alcoholic seeks to eke out a living for herself and her wife, loses her wife, gains a genie, and proceeds to continue to make terrible decisions constantly until things just kind of work out for her. as much as i hated the protagonist, the rest of the characters were interesting enough, as was the core romance. still recommended, if you can get your hands on a copy. Homophobia Content: peppered throughout; the genie of the title is exceptionally homophobic, though (surprise) she relents by the end.

Lady Knight by L-J Baker (Amazon) another of my top favorites, we watch the world’s sole lady knight as she faces constant sexism and discrimination, falls in love, faces constant homophobia and her lover forcibly married away from her, general sadness and ill tidings abound. by and large, it’s a tragedy, but the characters (especially the protagonist) are extremely excellent, relatable, and well written. the constant sexism (however realistic it may unfortunately be) definitely wears at you, but it’s worth going through. Homophobia Content: oh my god there’s so much and it never ends. sexism too; if you can’t handle them, avoid.

The Pyramid Waltz by Barbara Ann Wright (Amazon) oh my god there’s like three sequels to this? i just found out when i went to get that link, holy shit i’m so excited now. anyway apparently i only read book 1 of a four book series, but book 1 was really fucking great! standard fantasy setting, romance between a princess and an exotic visitor, political intrigue and murder, you get the idea. really fucking cool details, though, like that magic is performed through little pyramid-shaped objects; they go to a lot of detail about it and how it all works and it clicked with me pretty well. the main couple were great, but the side characters vary in depth and interest. overall, recommended, i’m gonna go buy the other three right fucking now and binge on them. later. Homophobia Content: none that i can recall, at least in the first book. the princess is very gay and no one ever questions it.

12 notes

·

View notes